CHAPTER NINETEEN

Hollandia—Greatest Triumph?

Douglas MacArthur’s gamble in the Admiralties was barely won when he turned his attention to the next operation. It was to be a longer leap, an even bigger gamble, but if successful it might result in what was arguably his greatest strategic triumph of World War II.

However MacArthur chose to portray the advances of his Allied command, the basic math of the previous two years—from his arrival in Australia in March of 1942 until the seizure of the Admiralties in March of 1944—showed that the New Guinea front of his Southwest Pacific Area had progressed from the outskirts of Port Moresby to Buna and then westward to Saidor, a distance of approximately four hundred miles. At that rate, it would take another four years to advance the remaining 1,600 miles to Mindanao, let alone reach Luzon or Japan.

Admittedly, the pace was quickening and would continue to do so as more men and materiel, as well as increased amphibious capabilities, were brought to bear. But at that point, MacArthur’s goals—to trap major portions of Adachi’s Eighteenth Army at Lae and east of Saidor—had not been realized, in part because he attempted encirclements over small distances well within the range of George Kenney’s land-based air. As MacArthur pondered the map of New Guinea in the wake of the Admiralty landings, he would focus on two weapons in his arsenal that were gaining in both reliability and strength.

The first was Ultra. Kenney had long been relying on navy Ultra to orchestrate his air operations. Ultra was at the core of his two greatest air victories to date—the destruction of the Bismarck Sea convoy, in March of 1943, and the Wewak airdrome assault, in August of 1943. Without either or both of those victories, MacArthur’s advance to Lae would have been far more problematic.

The capture of Japanese codebooks at Saidor provided Ultra on Japanese army movements in similar detail. Willoughby would never be considered brilliantly insightful, but Ultra analyzed by MacArthur’s chief signal officer, Spencer Akin, had allowed Willoughby to make an accurate estimate of Japanese troop strength in the Admiralties. This success dispelled doubts about Ultra’s credibility and firmly cemented Ultra information as an essential component of future operations.1

The aircraft carriers of the United States Navy comprised MacArthur’s second new weapon. Having witnessed Kenney’s air successes, MacArthur repeatedly lobbied for land-based air to cover his advances and charged that a lack of it was the Achilles’ heel of Nimitz’s thrust through the central Pacific. Yet in just six months’ time, Nimitz had advanced the central Pacific front several thousand miles, from Hawaii to the Gilbert and Marshall Islands, and stood poised to leap another thousand miles to the Marianas by relying on an outpouring of new aircraft carriers. It would take some coordination with Nimitz—and a solid plan to follow up rapidly with bases for land-based air—but if carrier aircraft could support amphibious landings during initial assaults, the radius of MacArthur’s potential reach could be greatly expanded.

Asserting that the seizure of the Admiralties presented “an immediate opportunity for rapid exploitation along the north coast of New Guinea,” MacArthur told Marshall on March 5 that he proposed to make the Hollandia area, not Hansa Bay, his next objective.

One hundred and forty miles west of Saidor but still one hundred miles short of Wewak, Hansa Bay was the next logical assault point if MacArthur were to make another jump of approximately the same distance as he had from Finschhafen to Saidor. General Adachi expected as much and planned a warm reception. MacArthur knew this from Ultra intercepts and reported to the Joint Chiefs that the Japanese had concentrated ground forces east of Hollandia in the Madang-Wewak area on either side of Hansa Bay while also concentrating air defenses west of Hollandia.

MacArthur didn’t phrase it quite this way, but relatively weak Japanese forces in the Hollandia Bay area were like the hole in a doughnut. From three airfields in that vicinity, MacArthur could isolate the remainder of Adachi’s Eighteenth Army to the east at Madang-Wewak while stopping further development of airfields that might block his advance westward. To do this, MacArthur told the chiefs, it would be necessary to retain naval reinforcements borrowed from the Central Pacific Area for the Emirau operation.

More significant, MacArthur said it was necessary—despite talk that Halsey’s South Pacific forces would soon be out of a job—“to continue the operation of the South Pacific Force in the theatre of the Southwest Pacific area until Hollandia is secured.” In other words, with the bulk of Halsey’s opposition in the Solomons bypassed or defeated, MacArthur wanted to keep control of those forces and not see them transferred to Nimitz for Central Pacific Area operations. Noting that Halsey concurred with his plan, MacArthur asked for the Joint Chiefs’ prompt approval.2

Much like the plan to bypass Rabaul, this leap to Hollandia had many fathers. Kenney claimed that upon MacArthur’s return from Los Negros, the two men discussed “bypassing Hansa Bay and jumping all the way to Hollandia.” The evidence suggests, however, that Kenney was focused on advancing his fighter operations to an intermediate base and was not terribly keen about relying on air cover from carriers.3

As Bill Halsey recalled, success in establishing airfields to cover advances throughout the South Pacific “made me feel that the same thing could be accomplished at Hollandia by bypassing all strong points in between.” Halsey didn’t take full credit for the idea but reminisced that he had been “aided and abetted in this presentation to MacArthur by a Brigadier General, whose name I unfortunately have forgotten.”4

The brigadier general in question worked for Chamberlin as the head of the G-3’s planning section and was not one to be forgotten. His name was Bonner Fellers, and, although he was not one of the Bataan Gang, he had served under MacArthur in the prewar Philippines and had carried on a correspondence with him afterward. An unabashed MacArthur admirer, Fellers held posts as military attaché in Egypt and with the OSS in Washington before again landing a spot on MacArthur’s staff in 1943.

In postwar correspondence, Fellers did not deny that Halsey may have championed the idea of taking Hollandia to MacArthur at a conference in Brisbane on March 3, but “by that time,” Fellers recalled, “the Hollandia operation had already been planned in our planning section and MacArthur knew all about it.” Fellers claimed that during the Finschhafen campaign, he had looked at the map of New Guinea and “then and there I decided that if ever we were to liberate Manila, which was some 2500 miles away, we had better start taking longer hops.”

Fellers talked the Hollandia idea over with his navy and air force counterparts and found that “both were enthusiastic.” But when Fellers disclosed the concept to his immediate supervisor, Chamberlin “hit the ceiling,” according to Fellers, “and ordered me to drop the wild scheme.” Nevertheless, Fellers and his group continued to work on the plan and found a way to pass the concept on to MacArthur.

Because Fellers was, in his words, “on evil terms with C/S Sutherland”—not an unusual occurrence—he went to MacArthur’s aide-de-camp and asked him to relay it to MacArthur. According to Fellers, MacArthur “sent word immediately to continue the plan.”5

By one account, on the day the operational plans for landings at Hansa Bay were being mimeographed in preparation for the “dry-run” planning conference that MacArthur always held before operations, MacArthur announced that he had reconsidered the options and decided that the next objective would be Hollandia instead of Hansa Bay. He directed Chamberlin to “take the staff to your office and spell out the details.”

According to Fellers, Chamberlin was “livid.” Outside in the hall Chamberlin told Fellers, “You have double-crossed me. You’ll have to hold the critique as I have never seen your plan.” Then Chamberlin went on to tell Fellers that “for the first time MacArthur’s staff had failed its Chief and that [Fellers] was to blame. He said the operation would fail.”6

Years later, Dan Barbey told Fellers that he “was always under the impression that this leap frog along the New Guinea coast and into Hollandia was your idea.”7 Perhaps. But having crossed Chamberlin and ignored Sutherland—a dangerous tightrope to walk—Fellers was fired as chief of the G-3’s planning section. MacArthur saved him, however, by making Fellers his military secretary and chief of psychological operations. Fellers continued to work for MacArthur, and he played a major role in the administration of postwar Japan.

His banishment notwithstanding, Fellers assured Chamberlin that the optimistic schedule of a rapid advance to Hollandia was justified by the enemy’s increasingly difficult position. “In actual ground combat,” Fellers concluded, “the enemy west of Wewak will be as formidable as ever but his air force is on the wane, his fleet out of balance, his supply unsatisfactory.”8

More than just providing a glimpse of the occasional friction among MacArthur’s staff, the Hollandia planning process shows that, as in the case of bypassing Rabaul, operational ideas evolved through discussions among many parties rather than originating with one person—contrary to the image-burnishing descriptions of MacArthur or any other individual being struck by a lightning bolt of strategic genius. Ultimately, of course, the decision to implement any strategic idea rested with the Joint Chiefs of Staff—Leahy, Marshall, King, and Arnold.

The Joint Chiefs responded to MacArthur’s proposal to bypass Hansa Bay and strike at Hollandia via a wide-ranging joint directive to MacArthur and Nimitz. Among the thorny issues in their discussions had been whether to assault Truk directly or bypass it à la Rabaul. Issued on March 12, 1944, the directive’s principal author was Admiral King, and it left no doubt that Pacific strategy was pointed toward “the Formosa-Luzon-China area” by way of “the Marianas-Carolines-Palau-Mindanao area”—but it continued to envision twin drives across the Pacific by MacArthur and Nimitz.

Specifically, the Joint Chiefs charged MacArthur and Nimitz with six tasks:

1. Halsey’s consolidation on Emirau as the final step in the encirclement of Rabaul;

2. prompt completion of the Manus airfields and Seeadler Harbor facilities for the benefit of all naval forces;

3. occupation of the Hollandia area, as proposed by MacArthur, with a target date of April 15, the primary objective of which would be the establishment of air bases for heavy bombers from which to strike the Palau islands and neutralize western New Guinea and the island of Halmahera—essentially protecting the left flank of the twin attack;

4. Nimitz seizing the Marianas-Carolines-Palaus triangle by invading the southern Marianas on June 15, then bypassing Truk and landing in the Palaus by September 15, the primary objective being to establish forward staging areas for operations against Mindanao, Formosa, and China;

5. Occupation of Mindanao by MacArthur’s SWPA forces, supported by the Pacific Fleet, with a target date of November 15, 1944, further extending left-flank protection into the Philippines but still leaving unanswered the perennial question of whether to attack Formosa directly or via Luzon; and

6. Occupation of Formosa by Nimitz with a target date of February 15, 1945, and, on the same target date, occupation of Luzon by MacArthur, “should such operations prove necessary prior to the move on Formosa.”9

Joint Chiefs chairman Leahy felt that this directive for operations against Japan “greatly clarified the situation” in the Pacific for the following twelve months. MacArthur and Nimitz were directed to confer with each other to ensure ample coordination and mutual support. “It appeared, for the time being at least,” Leahy recalled, “that MacArthur and the Navy would be working in harmony in the far-flung areas that constituted our Pacific battlefront.”10

From MacArthur’s viewpoint, the directive certainly did not pour the bulk of Pacific resources into his Mindanao axis, which Sutherland had been lobbying for, but neither did it preclude MacArthur from attaining his long-stated goal of returning to the Philippines. Having lost the battle of Seeadler Harbor and desperately needing Nimitz’s carriers to make the leap to Hollandia, MacArthur did what he usually did in such situations: he made an abrupt about-face.

“I have long had it in mind to extend to you the hospitality of this area,” MacArthur cordially wrote Nimitz. With assurances of “a warm welcome,” he invited the admiral to Brisbane for a personal conference so that “the close coordination of our respective commands would be greatly furthered.”11

Nimitz received MacArthur’s invitation upon returning to Pearl Harbor from a Washington conference with King. “It will give me much pleasure to avail myself of your hospitality in the near future,” he immediately cabled MacArthur. “I am certain that our personal conference will insure closest coordination in the coming campaign.”12

And generally it did. Nimitz and his planning staff arrived in Brisbane by PB2Y Coronado on March 25. As the four-engine flying boat taxied to the dock, MacArthur, as was his custom when receiving important visitors, was waiting to greet the admiral. Seeking to break the ice in their first meeting, Nimitz came bearing gifts: orchids for Jean, playsuits for Arthur, and several boxes of Hawaiian candy for the entire family. Naturally, MacArthur put Nimitz up at Lennons, then hosted a rather grand banquet in his honor in the hotel’s ballroom that evening.13

When MacArthur, Nimitz, and their respective staffs got down to business the following morning, MacArthur seemed pleased that the JCS had laid out a schedule of objectives for the entire 1944 calendar year, including MacArthur’s return to the Philippines via Mindanao—a plan, Nimitz acknowledged to King, that was “very dear to [MacArthur’s] heart.”

More immediately, in support of the Hollandia landings, Nimitz agreed that the fast carriers of Task Force 58, part of Raymond Spruance’s Fifth Fleet, would pound Truk and other bases in the Carolines, then raid the Palau islands within a matter of days. Afterward they would stand off New Guinea to provide two days of air cover for the Hollandia landings. Should the Japanese navy sortie in strength to oppose any of these operations, Nimitz prepared to deploy a battle line of six battleships, thirteen cruisers, and twenty-six destroyers from forces screening the carriers to engage them.

More than the Japanese fleet, however, Nimitz was nervous about the Japanese aircraft—between two hundred and three hundred of them—reportedly massed at the three airfields near Hollandia. Confident that they were safely beyond the reach of Kenney’s P-38 fighters, the Japanese had distributed aircraft across the fields in a way that was almost reminiscent of the atmosphere at Clark Field on December 8, 1941. George Kenney, however, was determined not to be constrained when it came to the operational range of P-38s. He assured Nimitz that he would find a way to eliminate the threat from Hollandia by April 5. Most in attendance at the meeting looked skeptical, but MacArthur merely accepted Kenney’s statement at face value.14

Thus, in Nimitz’s words, “everything was lovely and harmonious until the last day of our conference when I called attention to the last part of the JCS directive.” This was the paragraph ordering Nimitz to prepare Formosa assault plans and MacArthur to do the same for Luzon, but only should those “operations prove necessary.” Those were the wrong three words to focus upon, as Nimitz quickly learned.

As Nimitz reported to King, MacArthur “blew up and made an oration of some length on the impossibility of bypassing the Philippines—his sacred obligations there—redemption of the 17 million people—blood on his soul—deserted by American people—etc. etc.—and then a criticism of those gentlemen in Washington who—far from the scene and having heard the whistle of bullets, etc.—endeavor to set the strategy of the Pacific War.”15

Marshall, King, and others had heard MacArthur’s mantra before, of course, but it also became clear to Nimitz that by returning to the Philippines, MacArthur meant a liberation of Manila and Luzon, not merely a flank holding action on Mindanao. Nimitz nonetheless responded diplomatically to MacArthur’s rant and salvaged the unity of the conference. When he next met with King face-to-face in May, Nimitz characterized his relations with MacArthur as “excellent.”

The Hollandia operation was divided into three pieces. The little town of Hollandia itself sat on Humboldt Bay, reportedly the best anchorage between Wewak and Geelvink Bay, some five hundred miles farther west. The place names told the story: just east of Hollandia, one passed from Australian-administered North-East New Guinea into Netherlands New Guinea, the eastern end of the Netherlands Indies that extended west to Sumatra.

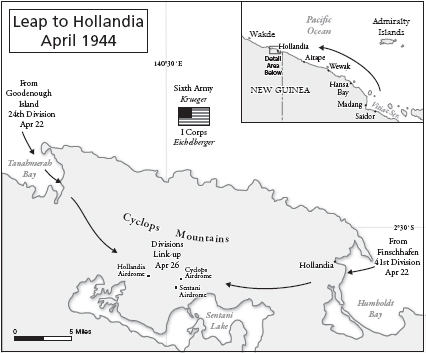

Inland a dozen miles from Hollandia, behind a jungle-clad uplift seven thousand feet in elevation called the Cyclops Mountains, three Japanese airfields sprawled on a level plain between the mountains and the northern shore of tropical blue Lake Sentani. As Admiral Dan Barbey put it, “MacArthur wanted those airfields,”16 and to take them, Walter Krueger’s Alamo Force planners devised a two-pronged movement: inland and west from Humboldt Bay and inland and east from Tanahmerah Bay, twenty miles distant, at the other end of the Cyclops Mountains.

The third piece called for a landing at Aitape, around 120 miles east of Humboldt Bay. Ground forces there could protect MacArthur’s eastern flank and block Eighteenth Army reinforcements from Wewak. More significant, however, was another airfield complex at Tadji Plantation, around eight miles inland and southeast from the landing zone, which appeared lightly defended. Allied engineers estimated they could repair any bomb damage to at least one runway within forty-eight hours of its capture. An airstrip at Tadji was the final piece Kenney needed to fulfill his promise to eliminate Japanese airpower from Hollandia and assume the burden for landing-zone air cover from the navy.17

Years later, Barbey reminisced to Bonner Fellers: “I always thought [Kenney] was a pompous, unimaginative little runt, but if one were to believe what he says about himself in his book the conclusion might be reached that MacArthur won the war because of Kenney and his B-17s—and that even MacArthur might not have been necessary in the final showdown.”18 Kenney’s cocksure attitude may well have deserved such a critique, but it is hard to argue with the plan Kenney, Whitehead, and their operations staff devised to subdue Hollandia.

Recognizing the importance of stretching the range of its P-38s, but not wanting the Japanese to know the full extent of its capabilities too soon, the Fifth Air Force took delivery of fifty-eight new long-range P-38s and outfitted another seventy-five older models with extra wing tanks. Kenney limited his strikes against Hollandia to occasional nighttime attacks by solitary bombers without fighter cover and forbade any fighters to fly beyond Tadji, even if they were equipped to do so. This had the effect of further lulling the Japanese into a false sense of security. As part of their big defensive buildup, they parked airplanes wingtip-to-wingtip, even in double lines alongside the runways.

Originally, Kenney and Whitehead planned a massive low-level assault similar to the surprise strike against Wewak in August of 1943. Then reconnaissance photos disclosed a concentration of antiaircraft batteries at both ends of the broad Lake Sentani plain. Kenney decided to concentrate on the antiaircraft batteries as part of the first strike. On the morning of March 30, eighty-two B-24s appeared in the skies over the Hollandia airfields. Forty Japanese fighters confidently rose to meet them but were quickly jumped by twice that number of P-38s suddenly showing off their long-range capabilities. The B-24s dropped a carpet of fragmentation bombs, destroying twenty-five planes on the ground and badly damaging another sixty-seven while knocking out antiaircraft batteries and setting fuel tanks ablaze. As one squadron of B-24s reported, “Hollandia had really been ‘Wewaked.’”

The next day, the Fifth Air Force struck again in similar strength with similar results. By the third attack, on April 3, after-strike photographs showed the fields littered with almost three hundred wrecked and burned-out aircraft and the installations riddled and pockmarked from repeated strafing by B-25s and A-20s. The escorting P-38s took out most of the remaining Japanese fighters, and the survivors sought refuge at fields well to the west of Hollandia. As one disgruntled Japanese seaman put it, “We received from the enemy greetings, which amount to the annihilation of our Army Air Forces in New Guinea.” Kenney had made good on his promise to MacArthur and Nimitz.19

The brunt of the Hollandia landings was to be borne by Krueger’s Alamo Force, but the corps commander assigned by MacArthur to direct the Twenty-Fourth and Forty-First Infantry Divisions as they went ashore at Tanahmerah and Humboldt Bays was a name that had not been heard much during the previous year. Lieutenant General Robert Eichelberger, who had indeed taken Buna and come back alive, was returning to combat after his year in semiexile in Australia.

Charged with training troops, Eichelberger’s duties had included squiring Eleanor Roosevelt around the South Pacific on an inspection tour in September of 1943, an event MacArthur chose to ignore. Three times during that year, the War Department requested that MacArthur release Eichelberger for duty in Europe, but according to Eichelberger, “General MacArthur disapproved all three requests.”

Eichelberger soon learned, however, that at Hollandia he would command the largest army operation in the Pacific up to that point. As Eichelberger recalled, “It was obvious that surprise would be our strongest ally.” MacArthur chose the code name Reckless for the assault.20

After his personal appearance in the Admiralties, there was never much doubt that MacArthur would accompany the landing force to Hollandia. On April 18, Dusty Rhoades was scheduled to fly MacArthur and his party from Brisbane to Port Moresby in the Bataan, but an oil leak grounded the general’s B-17. MacArthur flew north in Kenney’s borrowed B-17 instead and, after stopping to pick up a photographer and several correspondents in Port Morseby, arrived at Finschhafen and went aboard the cruiser Nashville.21

Until the beachheads were secured and Eichelberger moved his headquarters ashore, overall control of the landing operations was vested in Dan Barbey as attack force commander.22 For the sake of mobility among the three beachheads, Barbey flew his flag from the destroyer Swanson. Eichelberger joined Barbey on board the Swanson as it sailed from the embarkation point of the Twenty-Fourth Division at Goodenough Island.

“I had not seen much of Eichelberger since the wind-up of the Buna campaign more than a year previously,” Barbey recalled, noting that “because of his outspoken, critical, and sometimes belligerent manner, [Eichelberger] had not endeared himself to the top command in the Southwest Pacific.” “Top command” was a polite way of saying “MacArthur,” but Barbey claimed to enjoy his “close association” with Eichelberger.23

Krueger, as overall commander of Alamo Force, sailed on board the destroyer Wilkes from the embarkation point of the Forty-First Division just south of Finschhafen. With so much brass at sea, Admiral Kinkaid, SWPA’s top naval commander, chose to stay at Port Moresby, where he had the communications equipment to effectively coordinate Nimitz’s loan of attack carriers for air cover over the landings. Kinkaid didn’t say so at the time, but a few weeks later, he professed to see “no earthly reason” why Barbey “should be saddled with the additional hazard” of having Krueger—and, by inference, MacArthur—afloat and taking up “a badly needed destroyer” and light cruiser that would have been better used for other duties.24

But the brass sailed in force, and warships, transports, freighters, and a bevy of plodding LCIs, LSTs, and other amphibious vessels converged on the Admiralty Islands. This was indeed the circuitous route to Hollandia, but the islands provided a protected rendezvous point and, more important, disguised the true destination from snooping Japanese planes and submarines along the New Guinea coast. Even after a search plane spotted some of the ships, their location seems to have fooled Japanese commanders into believing that their destination might be Rabaul, Kavieng, or Truk, which had just been raided again by Nimitz’s carriers. As for New Guinea itself, General Adachi still expected the next Allied assault to come near Hansa Bay or Wewak, and deceptive Allied air attacks and PT boat activity in the area had been calculated to do nothing to dissuade him.

Shortly after sunrise on the morning of April 20, an assault convoy of 164 ships formed northwest of the Admiralties and headed west at nine knots. Eichelberger marveled at the difference between this force and the thirty landing craft and two PT boats that had put part of a regiment ashore at Nassau Bay prior to the Lae campaign only ten months before. Staging the three-pronged Hollandia invasion was an immensely complicated job, but Eichelberger said it proved “that both the American Army and Navy had come of age.”25

Still, there were some anxious moments. On the second night out, radar picked up a large number of vessels lurking in the convoy’s path. All ships went to general quarters, including the Nashville, with MacArthur on board. Radio silence precluded any inquiries to Kinkaid at Port Moresby, and only later did Barbey learn that what the radar had picked up was the attack carriers shepherding them along.

Then it was time to turn south and strike quickly toward the New Guinea coast.

Shortly before sunset on the evening before D-day, the eastern attack prong peeled off from the main convoy and headed southeast for Aitape. In the darkness that followed, the central prong soon did the same, bound for Humboldt Bay. The Swanson—with Barbey and Eichelberger on board—the Wilkes, and the Nashville continued toward the westernmost landing zone, at Tanahmerah Bay. Both groups arrived off their respective beaches at 5:00 a.m. on April 22.26

Eichelberger had been up since 3:00 a.m., and after dressing slowly and reluctantly, he ambled into the Swanson’s mess room to find hot coffee and the table piled with mountains of paper-wrapped sandwiches made the night before. Given the day ahead, you could eat them or put them in your pocket for future emergencies. “Some sensible men,” Eichelberger recalled, “did both.”27

The day dawned overcast, and aircraft from Nimitz’s carriers swept over the landing zones and what remained of the airstrips at Lake Sentani and Tadji, but they encountered little if any resistance, and subsequent missions were canceled. Brief naval bombardments followed just before the first wave of landing craft came ashore. The surprise appeared to be complete. As one Japanese commander later admitted, “The morning that we found out that the Allies were going to come to Hollandia, they were already in the harbor.”28

The only major snag proved to be the narrow confines of the Tanahmerah beaches. Two landing zones were long and thin, one backing up to an impenetrable swamp, the other at the end of an almost impassable jungle trail that was supposed to lead directly to Lake Sentani but in fact was a dead end. Eichelberger quickly shifted the bulk of his reinforcements and arranged to land them at Humboldt Bay instead.29

Shortly after noon, the Nashville anchored in the outer harbor of Tanahmerah Bay, and MacArthur signaled for Eichelberger and Barbey—along with Krueger, who was offshore on the Wilkes as the destroyer did antisubmarine duty—to report on board his flagship. The next order of business was a visit to the beach.

With Barbey a little nervous about the responsibility, MacArthur, Krueger, and Eichelberger climbed into a landing craft and, under Barbey’s direction, headed toward shore. Halfway there, a report of a lone Japanese plane prompted Barbey to order the coxswain to steer toward the safety of a nearby destroyer, but MacArthur countermanded the order and directed that they continue toward the beach. The plane swooped over without firing and headed inland. Barbey claimed, “There was never the feeling that it was an act of bravado on MacArthur’s part, but rather that he was a man of destiny and there was no need to take precautions.”30

Barbey’s concern had not been misplaced. Two nights later, a lone Japanese plane dropped a stick of bombs on the fringe of an old Japanese ammunition dump at the Humboldt landing zone, and the resulting fire spread to an American gas dump and other supplies and equipment. The fire raged for several days, destroying the equivalent of eleven loads of LST cargo and killing twenty-four men—more casualties than were suffered on all three beaches in the initial landings.31

But MacArthur’s beach walk had gone off without incident—so well, in fact, that when his party returned to the Nashville, MacArthur proposed a bold idea. Perhaps they should have made an even grander leap. Why not expedite the capture of Wakde Island, 120 miles farther west? Barbey termed the idea “another of his startling proposals” but professed to be ready to carry out the navy’s part of the operation. Alamo Force commander Krueger was noncommittal, possibly letting Eichelberger take the lead in challenging MacArthur’s optimism. Eichelberger indeed came out strongly against the plan, arguing that it was far too soon to declare the Hollandia landings unqualified successes and that the full extent of Wakde’s defenses was as yet unknown.32

MacArthur mulled over the advice and decided to stick with the original plans, although Eichelberger’s relative caution may have been just one more reason for MacArthur to be less than satisfied with him. After MacArthur ordered the Nashville to stop by the Humboldt and Aitape beachheads for similar inspection tours ashore, it then returned him to Finschhafen. There, early on April 24, Dusty Rhoades and the repaired Bataan were waiting for the return flight to Port Moresby, even as the SWPA’s press release reported: “General MacArthur is at the front supervising activities of the landing. He reached the scene on one of our light cruisers engaged in the initial bombardment.”33

The coordinated air cover over the beachheads from Nimitz’s carriers had worked smoothly, even if it was limited in duration, because Kenney’s land-based planes had already decimated most of the Japanese airpower around Hollandia. Eichelberger wanted the carriers to remain and strike farther west as a precautionary move, but Barbey felt the situation was in hand and stuck to the agreed-upon release schedule for them to return to operations in the central Pacific. According to Barbey, it was the only time he and Eichelberger “disagreed on any matter of importance.”34

The real significance of the Hollandia operation was its overall success, even if MacArthur was uncharacteristically understated about it in his memoirs. Not mentioning his beach walks, he merely noted, “The Hollandia invasion initiated a marked change in the tempo of my advance westward.”35

Much more detail and hyperbole—as well as a warm and widespread regard for the contributions of all of the services involved—appeared in his pronouncements at the time. “We have seized the Humboldt Bay area on the northern coast of Dutch New Guinea,” SWPA’s April 24 communiqué reported. “The landings were made under cover of naval and air bombardment and followed neutralizing attacks by our air forces, and planes from carriers of the Pacific Fleet. Complete surprise and effective support, both surface and air, secured our initial landings with slight losses.”

Remembering MacArthur’s closest allies as well, the communiqué went on: “To the east are the Australians and Americans; to the west the Americans; to the north the sea controlled by our Allied naval forces; to the south untraversed jungle mountain ranges; and over all our Allied air mastery.” Together, they had thrown “a loop of envelopment” over Adachi’s Eighteenth Army, and, if anyone needed to be reminded of the parallel, “their situation reverses Bataan.”36

At the time, it was premature to assess whether the Hollandia operation was, as William Manchester called it in retrospect, MacArthur’s “greatest triumph.”37 For one thing, thanks to Ultra intelligence, MacArthur was well aware that Japanese ground strength was concentrated at Hansa and Wewak, not Hollandia. Well executed though the operation was at many levels—including that of a growing logistical capability, which inundated the beachheads with supplies—the assault was less of a daring gamble than has historically been presented.

Nonetheless, in a bold leap that took advantage of Ultra as well as naval air cover, MacArthur moved the Allied front in New Guinea forward almost five hundred miles. The one-two punch of the Admiralties and Hollandia further impressed the Joint Chiefs—even Admiral King. Pontifical though MacArthur could be, it was hard to argue with success.

And Hollandia must not be judged alone but rather as part of a four-month campaign stretching from the Admiralties to Hollandia and farther west to Wakde Island and Biak. Although Eichelberger in particular reined in MacArthur’s enthusiasm for expediting the assault on Wakde, that operation nonetheless took place on May 17–18. It was probably a good thing—as Eichelberger always maintained—that Wakde was given separate attention, as it proved more heavily defended than Willoughby’s intelligence indicated, proving that Ultra was not always an open book. In short order, however, Wakde’s airfields provided a needed base from which to protect the Hollandia airfields and project Kenney’s land-based air farther west.

Tiny, coral-ringed Wakde Island soon became even more valuable after engineers working on reconstructing the Hollandia airstrips found that the thick jungle soil above Lake Sentani wouldn’t support the weight of heavy bombers. Operations were expedited on the coral-based runways at Wakde instead so it could support the Forty-First Division landings at Biak on May 27. Biak Island sat astride the wide mouth of Geelvink Bay as the bay separated the bulk of Netherlands New Guinea from the dragon’s head of the Vogelkop Peninsula. Riddled with caves throughout a maze of coral, Biak proved to be a tough nut of Japanese defense before it was finally secured in mid-August.

MacArthur would become a vocal critic of the bloody battles that Nimitz waged at Peleliu and Iwo Jima, but at Biak MacArthur’s own casualty rates exceeded 25 percent, with 471 killed, 2,443 wounded, and thousands more temporarily incapacitated by some measure of jungle diseases. It was harder to argue with the number of Japanese killed in the action—few surrendered, and the total topped six thousand.38

In terms of overall Allied military effort, what makes MacArthur’s Admiralties-to-Biak campaigns particularly impressive is that they occurred in rapid fire not only as Nimitz’s massive central Pacific assault against the Marianas was getting under way but also as the supreme Allied effort was being directed against Europe with the invasion of Normandy on June 6, 1944. This in itself was proof that the United States and its allies were successfully prosecuting a two-ocean global war and that, contrary to his fears, MacArthur had hardly been relegated to a backwater.

On June 8, as the Biak campaign still raged, George Marshall sent MacArthur his congratulations on the campaigns that took him from Hollandia to Biak, which, Marshall said, had “completely disorganized the enemy plans for the security of eastern Malaysia.” Marshall’s subsequent characterization was just the sort of tonic MacArthur craved, but Marshall was on solid ground when he told his former boss: “The succession of surprises effected and the small losses suffered, the great extent of territory conquered and the casualties inflicted on the enemy, together with the large Japanese forces which have been isolated, all combine to make your operations of the past one and a half months models of strategical and tactical maneuvers.”

Advising MacArthur that he was off that morning for England to inspect the Normandy landings, Marshall added, “We are now engaged in heavy battles all over the world which bid fair to bring the roof down on these international desperadoes.”39

What Marshall did not say in so many words is that by the time of the Hollandia operation, MacArthur had become a master in combined air, land, and sea offensives. He had apprenticed in an army whose doctrine featured the deployment of infantry, cavalry, and horse-drawn artillery, but the far-flung reaches and varying geography of the Pacific demanded more flexibility and fluidity. And he rose to the challenge. Initially skeptical of airpower as chief of staff, MacArthur was forced by lack of troops and shipping to embrace it by 1942.

“As much as I respected MacArthur and liked him as a person,” George Kenney told D. Clayton James in a 1971 interview, “I’ve got to admit that he knew practically nothing at first about aviation. When I got out there, he didn’t even want to fly.” But Kenney readily admitted that MacArthur learned, adapted, and became an advocate.40

The same can be said for MacArthur’s embrace of sea power. MacArthur saw that Kenney’s inroads in the skies in turn gave him command of the seas and opened up a wide range of possible lines of attack. The result was that while the Japanese were increasingly forced to deploy along marginal jungle roads supported by strained and eventually nonexistent supply lines, MacArthur used his growing amphibious forces to make bold leaps, including those into the Admiralties and against Hollandia.

Aside from his evolution as a commander who utilized combined air, land, and sea operations fully to accomplish an objective, MacArthur’s greatest strength was that he kept up the pressure on his subordinates to maintain the advances and surprises necessary to progress the nine hundred miles from Finschhafen to Biak in just four months. He looked ahead with similar resolve toward targets in the Philippines. MacArthur’s great distraction, however—if not his most time-consuming weakness—was that he could not abide the threat he saw to his Philippine dreams should Nimitz oversee a direct assault on Formosa.

“It is my most earnest conviction,” MacArthur wrote Marshall on June 18, “that the proposal to bypass the Philippines and launch an attack across the Pacific directly against Formosa is unsound.” The only thing worse, MacArthur maintained, would be “the proposal to bypass all other objectives and launch an attack directly on the mainland of Japan [which] is in my opinion utterly unsound.”

Then MacArthur returned to his favored theme of the political ramifications of such an action. Should the United States deliberately bypass the Philippines and delay the liberation of the Bataan survivors and loyal Filipinos imprisoned by Japan, there would be a grave psychological reaction. “We would admit the truth of Japanese propaganda,” MacArthur told Marshall, “to the effect that we had abandoned the Filipinos and would not shed American blood to redeem them… [and] we would probably suffer such loss of prestige among all the people of the Far East that it would adversely affect the United States for many years.”

If serious consideration were being given to the direct assault against Formosa to the exclusion of Luzon, MacArthur requested that he “be accorded the opportunity of personally proceeding to Washington to present fully my views.”41

Marshall received this latest plea for the Philippines upon returning from his Normandy tour. Although the JCS had yet to consider MacArthur’s views, Marshall nevertheless responded with a four-page letter, because, as Marshall put it, “I think it important that you should have my comments without delay.” Marshall’s analysis shows his depth as a global strategist and suggests that the Joint Chiefs routinely exercised a far greater understanding of and ability to balance worldwide military priorities than MacArthur appeared to appreciate.

In the face of MacArthur’s leaps to Hollandia and Biak, Marshall told MacArthur that Ultra information suggested a steady buildup of Japanese strength in the wide swath of territory encompassing Mindanao, Celebes, Vogelkop, and Palau: “In other words further advances in this particular region will encounter greatly increased Japanese strength in most localities. There will be less opportunity to move against [the enemy’s] weakness and to his surprise, as has been the case in your recent series of moves.”

Despite the lessening value of China’s role in the Allied war effort, as recognized at the Tehran conference, Marshall nonetheless reiterated the chiefs’ “pressing problem” should China collapse and permit Japan to redeploy some of its troops to Formosa or elsewhere. That scenario might result in both Formosa and the Japanese island of Kyushu being more heavily defended in 1945. “Whether or not the Formosa or the Kyushu operation can be mounted remains a matter to be studied,” Marshall acknowledged, “but neither operation in my opinion is unsound in the measure you indicate.”

There was also, of course, the matter of the still-powerful Japanese fleet. Marshall told MacArthur that he had been insisting that their own Pacific fleet, particularly its burgeoning carrier force, should be employed across a wide front looking for an opportunity to engage. Once the Japanese fleet was destroyed, Marshall advocated going “as close to Japan as quickly as possible in order to shorten the war, which means the reconquest of the Philippines.”

Only after making these points did Marshall turn personal. In regard to the reconquest of the Philippines, Marshall noted, “We must be careful not to allow our personal feeling and Philippine political considerations to override our great objective, which is the early conclusion of the war with Japan. In my view, ‘by-passing’ is in no way synonymous with ‘abandonment.’ On the contrary, by the defeat of Japan at the earliest practicable moment the liberation of the Philippines will be effected in the most expeditious and complete manner possible.”

And should MacArthur seem to see Admiral King and other supposedly sinister forces within the US Navy at work behind a naval lunge directly toward Formosa or Kyushu, Marshall tried to forestall MacArthur’s predictable response. “That is not the fact,” Marshall told him. “I have been pressing for the full use of the fleet to expedite matters in the Pacific and also pressing specifically for a carrier assault on Japan.”

Then Marshall did what he had done on other occasions when MacArthur appeared to threaten to go over his head—he graciously offered to facilitate it. “As to your expressed desire to be accorded the opportunity for personally proceeding to Washington to present fully your views,” Marshall concluded, “I see no difficulty about that and if the issue arises will speak to the President who I am quite certain would be agreeable to your being ordered home for the purpose.”42

This was the second time in only a few months that MacArthur had requested a presidential audience as a way to press his point with Marshall. This time, he was going to get what he asked for.