CHAPTER TWENTY-ONE

Toward the Philippines

Despite Douglas MacArthur’s professed satisfaction after meeting with Franklin Roosevelt in Honolulu, the debate over returning to Luzon and all the Philippines was far from resolved. Admiral King remained the chief proponent of the Luzon-bypass, leap-to-Formosa strategy, but he also found himself temporarily allied with MacArthur on another matter. Having largely abandoned Pacific operations to American control in the spring of 1942, Great Britain was subsequently sniffing the fruits of victory.

MacArthur had warned Roosevelt in Honolulu that British interest in taking over a portion of his Southwest Pacific Area and attacking the Netherlands Indies from bases in eastern Australia was premised far less on military necessity and opportunity than on Churchill’s political agenda for the British Empire. The Dutch, Australians, and Americans were all decidedly opposed to such a plan, MacArthur claimed, because “after two and a half years of struggle when American and Australian forces had defeated the Japanese, the British wanted to come in and claim rich territorial prizes.”1

The primary vehicle for this planned reassertion of British imperialism was to be the time-tested deployment of a sizable portion of the British fleet. As commander in chief of the United States Fleet, King adamantly opposed British naval participation in the Pacific, seeing it as too small to make a real impact, incapable of being self-sufficient, and disruptive to existing chains of command and supply. To that end, before departing Hawaii prior to MacArthur’s arrival, King wrote MacArthur with what he termed “some forewarning” about British proposals for just such an encroachment into his area.

King’s letter was a not-so-subtle effort to recruit MacArthur’s opposition. And it was effective. The admiral’s mere mention of the prospect of the British utilizing bases in Australia, sucking supplies out of the American logistics pipeline, and conducting offensive operations near MacArthur’s front in western New Guinea (the Banda Sea area around Ambon, for example) was enough to bring MacArthur immediately to King’s side.2

“I am completely opposed to this proposition,” MacArthur responded after returning to Brisbane. “The British have contributed nothing to this campaign and, in fact, opposed the [1942] Australian proposal to make available Australian troops for the defense of their own country.” MacArthur waxed eloquent for two full pages about the successes of his existing command structure and his future plans for the Philippines and ended up concluding that he could “see no reason why the American command should be superseded by a British command at the moment of victory in order to reap the benefits of the peace.”3 King had himself an ally, but persuading Roosevelt to stand up to Churchill would be another matter.

As the Baltimore arrived at Auke Bay, near Juneau, on the last leg of the president’s swing through Alaskan waters, Roosevelt wrote MacArthur a “Dear Douglas” letter, saying it had been “a particular happiness” to see him again. The president made no reference to the British situation, but promised, “As soon as I get back I will push on that [Luzon] plan for I am convinced that as a whole it is logical and can be done.”4

MacArthur responded with apparent equal warmth, telling Roosevelt, “Nothing in the course of the war has given me quite as much pleasure as seeing you again. I think you know without my saying,” he continued, “how deep is my personal affection for you and how great my admiration for your unrivalled accomplishments over the years.”

Both these masters of political theater were undoubtedly laying it on a little thick, particularly given MacArthur’s own presidential aspirations. But in the midst of the campaign, they undoubtedly chose their words carefully in anticipation that they might become public. Despite his shocked private reaction to Roosevelt’s health, MacArthur professed his “fervent hope” that the president would be in Manila to raise the American flag once that city was retaken—a subtle form of continued lobbying for Luzon operations.5

By the time Roosevelt replied to MacArthur’s message, on September 15, the president was at the Second Quebec Conference—code-named Octagon—with Churchill, and the prime minister put Roosevelt squarely in a box when it came to the British fleet. Grandly offering Roosevelt assistance for Pacific operations, Churchill bluntly asked if his offer was accepted. There was little Roosevelt could say in response but yes, of course. One wry British observer noted that the official minutes should have read: “At this point Admiral King was carried out.”6

Marshall explained the outcome more diplomatically when he cabled MacArthur: “For our government to put itself on record as having refused agreement to the use of additional British and Dominion resources in the Pacific or Southwest Pacific was unthinkable.” The saving grace to both King and MacArthur was that no additional ground or air resources were to be deployed in the Central Pacific or Southwest Pacific Areas until the spring or early summer of 1945, and even then only in the event of Germany’s defeat.7 Thus there would be no ground or air newcomers to MacArthur’s drive toward the Philippines. As for the British fleet, its appearance in the Pacific would also take some time, and managing it would be left to Nimitz’s collegial discretion.

Roosevelt told MacArthur much the same thing in his September 15 reply and said he wished MacArthur “could be here [in Quebec] because you know so much of what we are talking about in regard to the plans of the British for the Southwest Pacific.” As for American forces, Roosevelt told MacArthur, “The situation is just as we left it at Hawaii though there seem to be efforts to do a little by-passing [of Luzon] which you would not like.” Nonetheless, Roosevelt assured MacArthur, “I still have the situation in hand.”8

This phrasing suggests that, commander in chief though he was, Roosevelt was not one to second-guess his Joint Chiefs militarily—certainly not at that point in the war. He continued to profess to MacArthur that he understood and leaned toward, if not supported, a rapid return to Luzon, but Roosevelt was perfectly content to allow the Luzon-versus-Formosa debate to run its course among the Joint Chiefs and their planners. Meanwhile, MacArthur had his own issues with allies.

Australia—and, to a lesser degree, New Zealand—had readily looked to MacArthur and the United States for help in the bleak spring of 1942 and as a result stretched, if not loosened, their Commonwealth ties to Great Britain. In May of 1944, Australian prime minister John Curtin offered his Commonwealth colleagues no apologies “for asking for American assistance in the days when Australia was seriously threatened,” and he insisted that Australia’s “acceptance of American help had in no way affected the Australians’ deep sense of oneness with the United Kingdom.” Curtin expressed his strong desire “to see the British flag flying in the Far East as dominantly and as early as possible.”9

Curtin was still most grateful to MacArthur for bulwarking Australia during 1942 and 1943, but as the front line moved farther and farther from Australia, there were limits to that gratitude. There was a growing frustration among many Australians over the utilization—or, in some instances, the perceived underutilization—of their air, land, and sea forces. The governments of Australia and New Zealand—the latter had deployed troops in the Solomons—both frequently felt like second-class allies who were informed of major diplomatic and military decisions only in an after-the-fact way, most recently with the decisions at the Teheran-Cairo conferences, which impacted both the China-Burma-India theater and the twin drives across the Pacific.

Early in 1944, Australia and New Zealand took matters into their own hands by convening a conference to urge (1) their representation at the highest levels in matters related to the final campaigns of the war; (2) the establishment of a regional defense zone; and (3) the creation of an international commission to shepherd dependent territories in the Pacific toward self-government. Curtin and New Zealand prime minister Peter Fraser also put their allies on notice that the use of wartime bases in their respective countries implied no postwar rights and that future ownership of Japanese territories in the Pacific should be resolved only as part of an overall Pacific settlement in which Australia and New Zealand participated.10

It was not entirely clear whether this spurt of Aussie-Kiwi independence was directed more toward the United States or Great Britain, but MacArthur’s political machinations over the deployment of the British fleet certainly didn’t foster the sort of cooperation Australia and New Zealand sought. After his return from Honolulu, MacArthur whispered to the Dutch that Australia, either directly or as a surrogate for Great Britain, had designs on the Netherlands East Indies and appealed to them to oppose any expansion of the British-led Southeast Asian theater. MacArthur assured them he was “the guardian of unimpaired Dutch sovereignty in this area.”11

Even as MacArthur courted the Dutch, however, he professed solid friendship to the British officials with whom he spoke, including the British high commissioner in Australia, Sir Ronald Cross. Quite disingenuously, MacArthur told Cross how much he looked forward to British naval units operating in his area and reportedly went so far as to remark how wonderful it would be if “an American general should sail into Manila under a British flag.”12

At around the same time, Curtin gave impetus to Churchill’s efforts to insert the British fleet into the Pacific by telling him, “There is developing in America a hope that they will be able to say they won the Pacific war by themselves.”13 Curtin’s message came mere days before Churchill pressed Roosevelt at Quebec to accept the British fleet’s involvement in the Pacific, but his sentiment had been building in Australian circles for some time.

The central issue was MacArthur’s use of Australian troops as the Allies advanced farther and farther along the coast of New Guinea. Because of the tenor of MacArthur’s communiqués, what most Americans did not know—or remember in hindsight—was that Australian troops had borne the brunt of the early fighting along the Kokoda Trail as well as at Gona, Wau, and Lae. It wasn’t until early 1944 that American army units in the Southwest Pacific Area outnumbered Australian forces.

There was little question that Australians had been in the vanguard, but in anticipation of this shift in numbers, MacArthur made it clear to Blamey that once the encirclement of Rabaul was complete, Blamey’s New Guinea Force would be reduced to mopping-up operations and garrison duties in increasingly rear areas. The last major Australian-led offensive in New Guinea occurred in late April of 1944, when the New Guinea Force captured Madang, west of Finschhafen, as MacArthur made the leap to Hollandia. Thenceforth, replacing the New Guinea Force as the spearhead would be Krueger’s Alamo Force, essentially the US Sixth Army.14

By August of 1944, Marshall questioned not so much the status of Australian units but rather the continuing viability of bypassed Japanese strongholds. “Indications are,” the chief of staff wrote MacArthur, “that the large Jap garrisons in the Solomons and New Guinea which have been by-passed possibly are not weakening as fast as we had hoped.” Marshall asked about using the newly arrived American Ninety-Third Infantry Division and some “available Australian units” to reduce these remaining strongholds, although he added that it might not be practical because “no additional assault shipping can be made available to you for this purpose.”15

MacArthur responded that the Ninety-Third Division was not yet combat ready, and in any event, “The enemy garrisons which have been bypassed… represent no repeat no menace to current or future operations.” MacArthur claimed that they had no offensive capabilities and would eventually succumb to attrition. “The actual time of their destruction,” MacArthur continued, “is of little or no repeat no importance and their influence as a contributing factor to the war is already negligible.” To try to take them out immediately would “unquestionably involve heavy loss of life” without gaining any strategic advantage.16

That made the mopping-up operations to which MacArthur soon relegated Australian forces sound rather benign, but, as will be seen, that is not what the Australians encountered in the field as MacArthur left them behind in New Guinea and pushed on toward the Philippines.

Meanwhile, the Luzon-Formosa debate was slowly moving toward a resolution. At a conference in Brisbane with War Department representatives shortly after returning from Honolulu, MacArthur argued that he could conduct the Luzon campaign in six weeks, probably even in less than thirty days, after landing in Lingayen Gulf, just as the Japanese had done in December of 1941. By comparison, he termed an assault on Formosa a “massive undertaking.” Japanese air left on Luzon might be difficult to neutralize beforehand, and shortages in service troops could make the longer leap problematic.

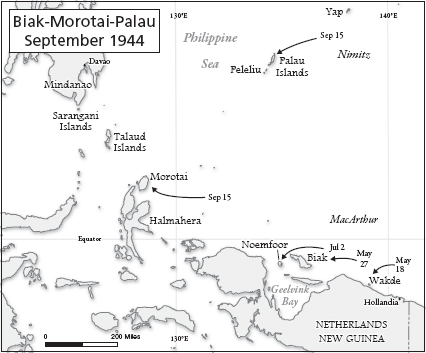

Borrowing a page from the compact schedule of amphibious operations conducted since the strike against Cape Gloucester nine months before, MacArthur proposed to Marshall that his forces invade the island of Morotai, five hundred miles beyond Biak, on September 15; the Talaud Islands, halfway between Morotai and Mindanao, on October 15; the tiny Sarangani Islands, just off the coast of Mindanao, on November 15; Bonifacio, on southwestern Mindanao, on December 7; Leyte on December 20; Aparri, on the northern tip of Luzon, on January 31; southern Mindanao on February 15; and finally Lingayen Gulf, off Luzon, on February 20.17 Had the stakes not been so high in terms of the human lives at risk, one would be tempted to call it a whirlwind tour de force of the Philippines.

King remained the chief champion of the Formosa plan. Many planners in Washington liked it as well, but almost all field commanders agreed with MacArthur that Luzon was the safer alternative. This was in part because of the proximity of land-based air once Leyte was taken as well as the shorter distances involved for carrier operations from Nimitz’s rapidly advancing forward bases, including the soon-to-be-captured anchorage at Ulithi. There was also the uneasy feeling in some quarters that leaping all the way to Formosa—however weakly defended King judged it to be—might arouse Japanese divisions based in China. At that late point in the war, those divisions remained a huge resource should Japan choose to redeploy them and commit the logistics necessary to move them to Formosa or the Philippines.

The fact that Japan didn’t divert enough troops from China to oppose the American-Australian advance throughout 1943 and 1944 appears, in hindsight, to be one of the greatest missteps of its military strategy. It is perhaps best explained by a combination of the historic animosity between China and Japan, China’s threat to Japan’s natural-resource needs in Southeast Asia, the Japanese army’s fixation with its seesaw campaigns against China, which had been going on since 1937, and—just as there was in the United States—a fair amount of interservice rivalry between the army and navy regarding overall strategy and concomitant responsibilities.18

MacArthur’s air and naval commanders, George Kenney and Thomas Kinkaid, strongly opposed the Formosa option as a leap too far. Perhaps that was no surprise given their boss’s position, but Bill Halsey also argued against it, advocating taking Luzon and then bypassing Formosa in favor of a direct strike against Okinawa or the Japanese island of Kyushu. Even Nimitz, who played the loyal King subordinate by arguing the Formosa option in front of Roosevelt at Honolulu, seemed increasingly lukewarm to the idea. He quietly instructed his Pacific Ocean Area planners to craft options against Okinawa rather than Formosa after an expected Luzon invasion.

King had previously done a good job of pushing Formosa with Marshall, who liked the basic idea of getting closer to Japan more quickly. But Marshall also recognized the limitations of amphibious capabilities and the numbers of available service troops. As the weeks went by, he pondered a more direct strike against Japan—Okinawa or Kyushu—as an alternative if Formosa were bypassed, regardless of what happened with operations on Luzon.

Then when Leahy weighed in as favoring Luzon instead of Formosa, the Joint Chiefs’ pendulum swung away from Formosa and toward the commitment MacArthur thought he had received from both Roosevelt and Leahy in Honolulu: Luzon would not be bypassed. But neither did the Joint Chiefs set a firm target date—yet.19

Given the pressing need to issue MacArthur orders beyond Biak and to give Nimitz similar directives in the western Carolines, Leahy suggested, and Marshall readily agreed, that MacArthur’s operations in the southern and central Philippines be approved through the contemplated December 20 landing at Leyte. But even the phrasing of these orders caused another round of debate among the Joint Chiefs. King grumbled about specifying the purpose of the Leyte landings—establishing air superiority in the Philippines or preparing for an assault against Formosa—and Marshall reprised his objection to the assumption that Formosa absolutely had to be taken regardless of what happened on Luzon.

Finally, on September 9, 1944, the Joint Chiefs again kicked the Luzon-Formosa can a little farther down the road. They ordered MacArthur to occupy Leyte with a target date of December 20. His objective was to concentrate whatever bases and forces in the central Philippines were necessary to support a further advance to Formosa by Nimitz’s forces or his own seizure of Luzon early in 1945.

While going ahead with his Central Pacific Area operations against the Palau islands, including tiny Peleliu, Nimitz was to provide MacArthur with fleet support, including air cover and assault shipping for the Leyte operations, and develop his own plans for either occupying Formosa or once again supporting MacArthur if he were directed to attack Luzon after Leyte.20 Thus the twin drives across the Pacific that many cheered and MacArthur routinely begrudged continued to converge on the Philippines from slightly different axes.

Part of the reluctance of the Joint Chiefs to resolve the Luzon-Formosa debate once and for all was the uncertainty of the war in Europe and the impact its end might have on the resources available to the Pacific. Unaware of Germany’s last gasp, yet to come at the Battle of the Bulge that December, there were many who thought Germany might surrender in the fall of 1944. In fact, at one point in September, news of Germany’s reputed surrender delayed the Bataan’s takeoff with MacArthur aboard until he could confirm that it was only a rumor.21

Amid this European uncertainty, the Joint Chiefs packed up to follow Roosevelt to the Second Quebec Conference with Churchill, Nimitz embarked his troops for the Palau invasion, MacArthur boarded the Nashville and sailed for the invasion of Morotai, and Bill Halsey, commanding the US Third Fleet, unleashed his attack carriers in raids against the Philippines. As it turned out, Halsey was about to rock the Luzon-Formosa debate in a big way.

Shortly after the squabble over the use of Seeadler Harbor, in the Admiralties, Bill Halsey worked himself out of a job in the South Pacific. The cleanup of bypassed pockets of Japanese resistance in the Solomons would take some time—as those assigned to the task would learn—but Nimitz wanted Halsey on the first string as the American fleet moved westward across the central Pacific.

Nimitz devised a rather ingenious rotating command structure between Halsey and Admiral Raymond Spruance, previously Nimitz’s chief of staff. While one admiral and his staff commanded operations at sea, the other hunkered down with his team at Pearl Harbor and planned the next phase of operations. They would then go to sea and take a turn at operational command. This system had the added advantage of confusing the Japanese somewhat, because when Spruance was at sea, the principal American fleet was designated the Fifth Fleet. When Halsey assumed command of essentially the same force, it was designated the Third Fleet. Task forces, such as those made up of fast carriers, were either Task Force 58 or Task Force 38, depending on the fleet designation.

Spruance drew the first assignment at sea and commanded the fleet for the landings in the Marianas in mid-June of 1944. The Japanese fleet had not sortied in a single combined force since Midway, but most thinking held that sooner or later, it would make one concerted do-or-die attempt to stem the American advance.

When two major Japanese naval forces converged on the Marianas and threatened to either attack the beachheads or engage the Fifth Fleet—or both—Spruance stood by his primary charge and arrayed his ships to defend the landings. Against the ensuing air attacks from enemy carriers, antiaircraft fire from Spruance’s battle line and pilots flying from his fifteen carriers shot down 383 Japanese aircraft, as opposed to twenty-five American losses, in what came to be called the Marianas Turkey Shoot.

The next day, Spruance sent his carriers west to engage the combined Japanese fleet. Despite the loss of three Japanese carriers—two from submarine torpedoes and one from air attack—the bulk of the Japanese force escaped, including at least six carriers. Although their air wings had been riddled with losses, the carriers that survived would soon figure heavily in Bill Halsey’s decisions.22

Having spent twenty months in command of the South Pacific Area, Halsey bade his officers and men an emotional farewell in June of 1944. As he did so, MacArthur assured him that it was “with deepest regret we see you and your splendid staff go” and called Halsey “a great sailor, a determined commander, and a loyal comrade. We look forward with eager anticipation to a renewal of our cooperative effort.”23

In response, Halsey felt compelled to add a personal note to the official dispatches. “You and I have had tough sledding with the enemy,” Halsey wrote MacArthur, “and we have had some other complex problems nearly as difficult as our strategic problems; and I have the feeling that in every instance we have licked our difficulties. My own personal dealings with you have been so completely satisfactory that I will always feel a personal regard and warmth over and above my professional admiration.”

“I also know and take great pleasure in telling you,” Halsey continued, “that the members of my Staff continually express their satisfaction over the way that business can be done by the South Pacific and Southwest Pacific. I sincerely hope, and firmly believe, that I will have further opportunities to join forces with you against our vicious and hated enemy.”24

On August 24, after a brief leave in the States and planning time in Hawaii, Halsey sailed west from Pearl Harbor on board the battleship New Jersey, one of the four mammoth sisters of the new Iowa class. Two days later, command of the fleet officially passed from Spruance to Halsey, and the carriers of the Third Fleet’s Task Force 38 unleashed ferocious aerial assaults against Yap, in the Carolines, and the Palau islands in anticipation of the landing on Peleliu. On September 9 and 10, the carriers made similar strikes against Mindanao but found, according to Halsey, that Kenney’s Fifth Air Force “had already flattened the enemy’s installations and that only a feeble few planes rose” in opposition.

Accordingly, Halsey moved northward and launched the remainder of the planned strikes against Leyte, Samar, and southeastern Luzon, in the central Philippines. On September 12 alone, his aircraft flew 1,200 sorties. After two more such days, Halsey claimed 173 enemy planes shot down, 305 more destroyed on the ground, fifty-nine ships sunk, and widespread damage to other ships and land-based installations. In return, only eight American planes fell in combat.

This gave Halsey pause. Having found the central Philippines, in his words, “a hollow shell with weak defenses and skimpy facilities,” he sat in the corner of his flag bridge chain-smoking cigarettes and pondering whether this “vulnerable belly of the Imperial dragon” could not be exploited by shifting MacArthur’s planned November assault on Mindanao to an earlier strike directly against Leyte. Finally, Halsey turned to his chief of staff and announced, “I’m going to stick my neck out. Send an urgent dispatch to CINCPAC.”25

Halsey’s message to Nimitz audaciously recommended that (1) the central Pacific assaults about to get under way against the Palau islands and Yap, as well as those scheduled in MacArthur’s area against Mindanao and the Talaud and Sarangani Islands, be canceled; (2) the ground forces earmarked for those assaults should be assigned to MacArthur for use in the Philippines instead; and (3) the invasion of Leyte should be expedited and rescheduled as far in advance of its planned December 20 date as possible.26

Nimitz was intrigued, but he had an immediate problem. The invasion of Peleliu was only forty-eight hours away, and it had been planned to coincide with MacArthur’s landing on Morotai. Eighteen thousand men of the veteran First Marine Division and another eleven thousand from the Eighty-First Infantry Division were crammed on transports inbound to the island. At the striking end of an ever-burgeoning trans-Pacific flow of men and materiel, Nimitz faced a dilemma: use these troops at Peleliu or find someplace to park them without clogging the pipeline behind them.

Nimitz decided that, this late in the game, he had no choice but to go forward with the Peleliu landings. It was a command decision that became controversial in hindsight, when large concentrations of Japanese ground troops fought tenaciously throughout a network of limestone caves and caused heavy American casualties. It proved that while Japan’s air resources may have been decimated and its naval commands again scattered after the Marianas, the garrisons of ground troops left behind were not about to give up easily.27

But the remainder of Halsey’s suggestions was another matter. Nimitz immediately passed them on to the Joint Chiefs, who by that time were in Quebec with Roosevelt for the Octagon Conference. Marshall and King received Halsey’s original message to Nimitz and Nimitz’s subsequent offer to place the army’s XXIV Corps, then loading in Hawaii for Yap, at MacArthur’s disposal for an expedited Leyte strike. Marshall, reluctant to make such a drastic change in timetable and objectives without input from MacArthur, asked the SWPA commander for his opinion. The reply came back that MacArthur was fully prepared to shift his plans and land on Leyte on October 20.

This message arrived in Quebec as Leahy, Marshall, King, and Arnold were at a formal dinner given by their Canadian hosts. They promptly excused themselves and met in conference to issue new orders. Because the men had “the utmost confidence in General MacArthur, Admiral Nimitz, and Admiral Halsey,” Marshall later reported, “it was not a difficult decision to make.” Within ninety minutes after MacArthur sent his enthusiastic endorsement, MacArthur and Nimitz received their orders to skip the three intermediary landings and execute the Leyte operation with a target date of October 20.28

According to Marshall, “MacArthur’s acknowledgment of his new instructions reached me while en route from the dinner to my quarters in Quebec.” But how were the Joint Chiefs able to communicate with MacArthur? Early on September 13, MacArthur departed Hollandia on board the cruiser Nashville, bound for the invasion of Morotai. Operating under strict radio silence, he was at sea and incommunicado for three days.

On the third day, September 15, he watched the first troops of the Thirty-First Infantry Division go ashore on a slender sand spit at the southern tip of the island. Shortly afterward, “indicative of the importance he attached to the operation,” as his press release put it, MacArthur headed ashore with amphibious chief Dan Barbey, physician Roger Egeberg, and press officer Larry Lehrbas and “landed on the beach with his troops.”

Enemy resistance in the landing areas was virtually nonexistent, in part because MacArthur had wisely chosen to occupy Morotai instead of more heavily defended Halmahera, just to the south, but unexpected coral reefs, shallow water, and mudflats caused delays and confusion. MacArthur’s landing craft grounded some yards from shore, and Egeberg recalled subsequently wading through water up to his armpits.

As the general’s party walked the landing zone for around an hour, MacArthur’s conversation with a group of officers was reported to the press with Lehrbas’s polished sense of drama: “Talking with a group of officers, General MacArthur said, ‘We shall shortly have an air and light naval base here within 300 miles of the Philippines.’ He gazed out to the northwest almost as though he could already see through the mist the rugged lines of Bataan and Corregidor. ‘They are waiting for me there,’ he said. ‘It has been a long time.’”29

By 1:00 p.m., MacArthur was back on board the Nashville and soon would be under way for the return trip to Hollandia. At some point, either because the Nashville broke radio silence or because it was monitoring messages flowing in and out of SWPA headquarters at Hollandia, MacArthur may have received an inkling of the exchanges among his headquarters, Halsey, Nimitz, and Marshall.

In fact, to add fuel to the ensuing fire, MacArthur dictated a message to Sutherland from the Nashville that not only seemed to imply that he heartily approved of the Leyte expedient but also that he was suggesting an even greater leap.

“Magnificent opportunity presents itself now that air resistance over Philippines will be neutralized,” MacArthur wrote, “to combine projected initial and final operations.” He wanted a simultaneous attack by six divisions against Leyte and Lingayen Gulf. “I am completely confident that it can be done and will practically end the Pacific War,” MacArthur concluded. “It is our greatest opportunity. The double stroke would be a complete surprise to the enemy and would not fail.”30

Whether this was simply the result of MacArthur’s grandiose musings as he sailed at sea after another successful landing or a cagey attempt to insert himself into the middle of the Leyte decision is uncertain. Either way, not until arriving in Hollandia midmorning on September 17 did MacArthur sit down at his desk and read the complete file of dispatches that had been received and sent in his absence by the one and only individual who dared issue such in his name—his chief of staff, Richard K. Sutherland.

Over the course of the prior eighteen months, Sutherland had increasingly suffered from vaulting ambition. His representation of MacArthur at the Pearl Harbor and Washington strategy sessions as well as his globe-girdling flight with Marshall after the Cairo conference had only increased his sense of importance and, more dangerous, his sense of entitlement. His promotion to lieutenant general—with MacArthur’s blessing, of course—had done nothing to weaken his ego.

According to MacArthur apostle Frazier Hunt, when MacArthur returned to Hollandia after Morotai, he was delighted with Sutherland’s Leyte decision and the accelerated timetable, but that wasn’t the whole story.31 Perhaps the best evidence that even Sutherland felt he may have overstepped his authority is his summoning of Kenney, Kinkaid, and Chamberlin hours before MacArthur returned to Hollandia to prepare them for a possible collision with their chief.32

Sutherland had already involved these three officers in discussions convened at Sutherland’s request as he pondered a response in MacArthur’s name to Marshall’s query about expediting Leyte. As Kenney told the story, “Quite naturally everyone was reluctant to make so important a decision in General MacArthur’s name without his knowledge of what was going on, but it had to be done.”

Kenney claims—with his usual hindsight, he placed himself at the center of everything—that he argued persuasively that whatever they “had been prepared to do on October 15 could now be switched to Leyte” as long as the navy had their backs with air cover from Halsey’s carriers. Kenney wasn’t ready to accept Halsey’s assertion that the central Philippines was an empty shell—once again, remaining ground forces would prove to be tough—but he agreed that the Japanese air threat was “not great enough to stop us from landing on Leyte.”33

Given pressure from the Joint Chiefs to accept the expedited schedule and Leyte as the next objective, and in view of their assessment that it was “highly to be desired and would advance the progress of the war in your theater by many months,”34 there was little else that a competent chief of staff cognizant of his commander’s resources and agenda could have done. It was the correct decision. Furthermore, it was a decision that had not been made in isolation or in haste but rather after focused discussion among the pertinent members of MacArthur’s immediate staff.

After lunch, MacArthur convened this same group, and Sutherland quickly brought up the key decision he had made with the counsel of those present in MacArthur’s absence. Sutherland had worried, according to Kenney, “about what the General would say about using his name and making so important a decision without consulting him, but his worries were wasted. MacArthur not only approved the whole scheme immediately” but also launched into a description of the “magnificent opportunity” of his one-two punch against Leyte and Lingayen Gulf.35

Knowing that logistically they would have their hands full with Leyte alone, MacArthur’s men slowly throttled back his enthusiasm. Sutherland took the lead and noted the problems of air cover over two widespread beachheads and the amphibious requirements of moving six divisions simultaneously. MacArthur looked to Kenney, who was usually his most vocal can-do cheerleader, but Kenney said little except to nod in agreement with Sutherland’s points. “Okay,” MacArthur concluded, “we can’t do it. But you must have me in Lingayen before Christmas. If Leyte turns out to be an easy show, I want to move fast.”36

That should have meant business as usual between MacArthur and Sutherland. Given their long history, during which MacArthur had routinely informed officers from George Marshall on down that Sutherland had full authority to speak on his behalf, MacArthur might simply have reveled in the results of Sutherland’s communications in his name and blessed them. After all, MacArthur’s long-cherished return to the Philippines was being expedited and it was to be supported with ships and troops from Nimitz’s command.

Such a seemingly commonsense appraisal of the situation, however, ran afoul of two critical influences. One was MacArthur’s own ego, and the other was a continuing error of personal judgment on Sutherland’s part in open defiance of MacArthur’s direct orders.

According to Dusty Rhoades, MacArthur arrived back in Hollandia from Morotai “in very good spirits.” Landing complications aside, Morotai was an important step toward the Philippines. But the rapid leap to Leyte, even if it didn’t include Lingayen at the same time—that was the epitome of bold strategy. Expediting Leyte even made MacArthur’s gamble in the Admiralties look like playground hopscotch. MacArthur simply had to be the central player in the decision.

What made it appear otherwise was the common knowledge in both army and navy command circles that MacArthur had been out of touch on the Nashville during the crucial exchanges. This was because Sutherland had been straightforward in advising Marshall of this fact in the course of his signed “MacArthur” communications.37 That didn’t seem to bother Marshall, but it ruffled MacArthur’s ego.

Rhoades, who was reasonably close to MacArthur and (given their long one-on-one cockpit conversations as they flew around the southwestern Pacific) arguably the person closest to Sutherland, may have put his finger on it. “It is possible,” Rhoades opined, “that MacArthur might have accepted the fact that Sutherland had made the strategic decision on his own but for the fact that all high-level commanders, including those in the navy, knew that Sutherland and not MacArthur was the source of the decision. This made it appear that Sutherland was usurping some of the commander in chief’s authority.”38 Perhaps. But what raised MacArthur’s temper to the boiling point were Sutherland’s actions in another matter.

While in Melbourne shortly after arriving in Australia from Corregidor, the married fifty-year-old Sutherland began a long-term affair with Elaine Bessemer Clarke, the thirtysomething socialite daughter of Sir Norman Brookes, who had been a champion Australian tennis player and was subsequently knighted for public service. By all accounts, Clarke was not a great looker, but, like Sutherland, she had a case of vaulting ambition and a desire to be in the thick of things. Reginald Bessemer Clarke, Elaine’s husband, was of the same mold as her father, being both an heir to the Bessemer steel fortune and a three-time Wimbledon player. He was then a prisoner of war in Malaysia, having been captured in the fall of Singapore. Together they had a young son, who had been born in early 1940.

When SWPA headquarters moved from Melbourne to Brisbane, Sutherland moved Clarke along with it and installed her as something of a receptionist for MacArthur’s headquarters in the lobby of the AMP building. MacArthur seems to have taken this in stride despite the widely known fact that Clarke’s presence had little to do with her secretarial skills. To circumvent MacArthur’s agreement with Australian prime minister Curtin that women in the Australian military services would not deploy overseas, Sutherland obtained a commission for Clarke as a US Women’s Army Corps (WAC) captain. Perhaps as a smoke screen, two other Australian women were commissioned as WAC lieutenants and continued their assignments as secretaries to Kenney and deputy chief of staff Dick Marshall.39

MacArthur seems to have assumed that, WAC commissions or not, these women would not be sent to forward areas or at the very least not put right under his nose. Sutherland chose to challenge this assumption almost immediately by having Rhoades fly him and Clarke to Port Moresby on March 30, 1944, in the Bataan.40 While MacArthur was away in Brisbane preparing for the Hollandia invasion, Sutherland gave Clarke free rein of Government House.

MacArthur learned of this arrangement upon returning to Port Moresby after the Hollandia landings. He ambled out of his room at Government House in his underwear after his customary afternoon nap with a strategy he wanted to discuss with Sutherland. As MacArthur began, “Dick, I have an idea,” a blond head popped up above the couch, and Elaine Clarke greeted him with a hearty “Good afternoon, General.”

MacArthur blushed, returned for his trousers, and later told Sutherland in no uncertain terms that he would not have women in his advance headquarters. Captain Clarke must leave Port Moresby immediately and not return. MacArthur’s decision was less about Sutherland and Clarke’s private indiscretions than his own need for some semblance of decorum. As Paul Rogers remembered it, “MacArthur might wander around in his underwear… [but] he did not care to be exposed to the view of a very young Australian woman whose husband languished in prison camp, who had direct, intimate connections with a vicious social circle in Melbourne… and, most of all, who was beginning to display independence and even provocative audacity.”41

Having issued an order, MacArthur considered the matter resolved. A few days later, both MacArthur and Sutherland returned to Brisbane for the better part of the summer, and Clarke resumed her seat in the lobby of the AMP building. One afternoon, shortly before Sutherland made the move to Hollandia to set up advance headquarters, MacArthur directly told Sutherland, “Dick, that woman must not go to the forward areas again.” Rogers did not hear Sutherland’s reply, but Rogers remembered MacArthur’s final words: “I want it understood. Under no circumstances is that woman to be taken to the forward areas.” It was a direct and unequivocal order. Rogers claimed that it was the first time he had ever heard MacArthur speak to Sutherland in such a manner.42

But the first thing Sutherland did as he set up an advance base of operations in Hollandia a few weeks later was to arrange for Clarke to be given nearby quarters and assume duties as something of a hostess at the newly constructed headquarters above Lake Sentani. Officers reporting fresh from combat were greeted with a cool drink and warm smile—not exactly the image of his front line that MacArthur wanted to convey.

Uniformed or not, Clarke was a distraction—particularly as she readily assumed the role of Cleopatra and went so far as to have Hank Godman, formerly MacArthur’s chief pilot, who was still on his staff, transferred to a combat assignment after he got into a quarrel with Clarke over the use of a jeep. MacArthur, having spent no time in Hollandia except for two nights en route to Morotai, was if not ignorant of the situation at least momentarily too preoccupied to address it.43

Returning from Morotai, MacArthur found Clarke performing her public duties. She was stark evidence that Sutherland had disobeyed his direct orders about her disposition not once but at least twice. This wasn’t about Sutherland keeping his pants zipped; it wasn’t even about Elaine Clarke being in Hollandia. This was about the one man in whom MacArthur had placed complete trust and granted full authority to speak and act in his name defying his direct orders.

How could MacArthur swallow the fact that a man who couldn’t even follow orders to keep his girlfriend out of MacArthur’s headquarters had taken the lead with the Joint Chiefs in initiating his long-planned leap to the Philippines? Publicly, MacArthur went forward with the Leyte decision and embraced it, but he never forgave Sutherland for making it in his name, largely because of his anger over the Elaine Clarke episode.

Their private confrontation apparently came the following day, after MacArthur informed Rhoades that he was remaining in Hollandia for one more night. What began with a reprimand for having made such a momentous decision as Leyte ended with a shouting match over Clarke. Sutherland begged to be transferred, granted sick leave, or given a field command, but that would have been too easy an out for him. MacArthur refused on all counts. Sutherland would stay and do his duty and send Clarke back to Australia immediately. If Sutherland refused to give such an order, MacArthur would do it for him in a final humiliation. According to Rogers, MacArthur’s last words to Sutherland as he left Hollandia were that Clarke would never be permitted to go forward to the Philippines.44

Back in Washington, the Joint Chiefs faced what had become an increasingly inevitable decision in the Luzon-Formosa debate. At the end of September, Nimitz finally convinced King that a rapid thrust to Formosa was impracticable on a number of levels. With the Leyte timetable moved forward to October 20, Luzon should be next. After that, the debate could be between Formosa and a direct assault of Japan’s southern islands early in 1945.

Consequently, on October 3, 1944, the Joint Chiefs ordered MacArthur to follow Leyte with an invasion of Luzon, presumably at Lingayen Gulf, with a target date of December 20. Nimitz was to provide fleet cover and support via Halsey for the landings as well as his promised army divisions.45 The question of Luzon versus Formosa was finally settled. The questions that remained—reports of the central Philippines being an empty shell aside—were, what sort of fight might MacArthur face on the beaches of Leyte? And how might the Imperial Japanese Navy respond?