Power, Sex, and Empire

THE DYNAMICS OF POWER

This chapter concerns the workings of power on the body and the centrality of power as a sociological and historical theme. It explores the dynamics of power in imperial situations and assesses the value of comparative studies in colonial discourse by examining aspects of sex in the Roman world and more recent colonial societies. I owe much in this respect to my reading of Michel Foucault, but, as will become apparent, my argument diverges significantly from the line taken by his last works.1

The chapter is also written in reaction to much recent scholarship on the concept of power in the Roman world. While my specific subject is sexual power and its effect on shaping Roman sexual attitudes, the broader aim is to refocus interest on the distorting influence of power on social development and change in the Roman world. It has become common for discussions of cultural relations between Rome and its subject peoples to be put in terms suggestive of symmetry and equality. Although Rome was by no means as racist and exclusive as more recent colonial powers, the impact of Roman conquest on subject peoples cannot be assumed to have been negligible. Just as the presence of pollution, rubbish, and faecal material on Roman streets is enough to make us view Roman water and food sources as “presumptively contaminated,”2 our starting point with Roman imperialism should be the presumption that it was based on significant power asymmetries, intrusion, exploitation, violence, and coercion. We can, of course, then consider the mitigating circumstances of the case and the degree to which Rome solicited participation, accommodation, and negotiation. Older views of imperialism have tended to disempower the subject peoples from any active role in their destiny; what I also want to emphasize is that all acts of collaboration, selective participation, and resistance took place within a dynamic structure of power relations.

Postcolonial theory is increasingly recognizing the importance of the unprecedented “opportunities” presented to servants of empires to indulge in new and often extreme patterns of sexual behavior. Much attention in the past has focused on the misbehavior of emperors, salaciously presented to us by the ancient sources.3 But these accounts have tended to describe more than to analyze, and also misdirect our gaze to the exceptional figures in society. The indulgences of individual emperors need to be understood in the broader context of changing sexualities in colonial societies. Mythic Roman orgies can thus be relocated in this discourse—Roman sources and the Latin sexual vocabulary reveal a pattern of domination and penetrative practices that cut across normative boundaries of morals, gender, class, and ethnicity.4 Of course, not everyone in positions of power showed such lack of restraint. Indeed, striking parallels exist in Roman, U.S., and British imperialisms; for instance, for a polarization of attitudes about sex, with visibly increased sexual license in society being in part countered by purity or moral campaigns. Similar discourse could be constructed in relation to other areas of indulgence and consumption in Roman elite society that were fed by imperial opportunity.5

While the effect on subject peoples of degrading forms of sexual compliance could easily be overstated—especially in terms of the actual numbers directly affected—I believe that the psychological taint of sexual humiliation and degradation has been a powerful tool for sustaining social difference between rulers and ruled in many colonial societies. Such patterns of behavior in the sexual sphere may thus serve as a good index of the wider social impact of empires on their subject peoples. There are, of course, other issues involved in making a reading of the body in the Roman world,6 but it is precisely because many recent studies have separated agency from structure that I have focused in this chapter on the links between power and the body. A secondary aim is to remind us of something lost sight of in a number of recent discussions of Roman imperialism: power and inequality lay at the heart of the discourse of the Roman Empire. Models that presuppose a “civilizing mission” or highlight unfettered native initiative rather miss the point. This chapter is thus a further contribution to continuing debate about postcolonial perspectives of Roman imperialism.7 Whatever their structural and ideological differences, there are important points of comparison to be made between imperial systems ancient and modern concerning this question of the operation of power, both physical and psychological, in colonial societies.8

ROMAN PERMISSIVENESS

From staid beginnings Roman sexual history moves towards a crescendo of eroticism such as the world has rarely seen.9

The sexual temper of the age was randy and permissive and tolerant of fairly bad behaviour, but not vicious or orgiastic.10

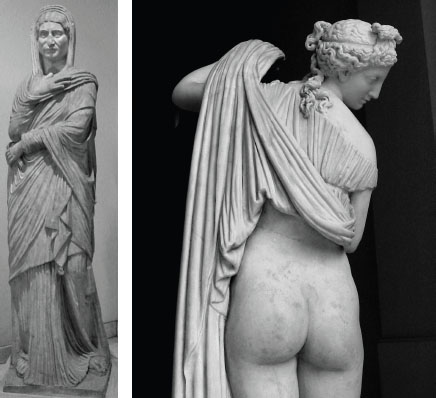

The transformation of Roman society and its sexual attitudes from “staid beginnings” to a hotbed of licentiousness opens up a series of questions. When did this change occur and why? Was it something internal to Roman society, bound up in social structures at the center of the empire, or did it develop through colonial contact?11 Our knowledge of Roman sexuality is not as detailed as we would wish, and primarily reflects the views and beliefs of the upper echelon of society.12 It is clear that early Roman society put great store on respectability, with Roman chastity and virtue (based on that elusive ideal of heterosexual marital intercourse for procreative purposes) being contrasted with Greek and Etruscan wantonness and lust (see fig. 4.1a). It is also apparent, though, that from early times different standards of behavior were expected of men and women. Virginity, modesty, and sexual fidelity were the key characteristics demanded of a Roman aristocratic bride, while men clearly had greater license, both for prior sexual experience and external affairs after marriage. However, dramatic change seems to have occurred when Rome acquired its first imperial possessions outside Italy. Prior to the second century BC, Venus was a “sexless Italian spirit of well-tended herb gardens” until Rome’s widening imperial horizons saw its being promoted as an equivalent to naked Aphrodite (see fig. 4.1b).13 Several points follow. This was a time of new wealth, increased slave ownership, and greater Roman prestige and self-image. For the Romans active in and alongside the armies that were sent to Greece, Asia Minor, and Spain at this time, it was a period of unprecedented opportunity and experimentation.14 Changes in sexual behavior were matched in the same period and for the same reasons by radical transformations in conspicuous consumption and experimentation with new forms of luxury—material, culinary, and artistic.15

FIGURE 4.1 (a) The archetype of the Roman demure matron contrasts with (b) increasingly more explicit depictions of sexy Venus.

Part of the problem in Roman society, but by no means unique to Rome, was that aristocratic marriages among the ruling senatorial and equestrian classes were generally political and economic arrangements between families rather than love matches. It was commonplace for men to marry much later than women and to take as wives young and sexually inexperienced girls.16 The chief aim of these marriages was to produce heirs, not happiness, and while Roman matrons were expected to endure loveless marriages in perfect fidelity for the sake of the children, men had license to pursue pleasures outside.17 The contrast between the normative Roman conditions for procreative marital sex and the range of sexual practices discussed below is striking: respectable couples were recommended to avoid lovemaking in daylight or in lit rooms, respectable women were not expected to remove all their undergarments in bed or to take a particularly active role. The contrast with what was demanded from prostitutes and slaves was marked (see fig. 4.2).18 Contrary to the impression to be gained from watching the 2005 TV series Rome, Roman matrons were not nymphomaniacs (though our literary sources suggest there were a few scandalous exceptions). Indeed, there is evidence to suggest that aristocratic wives tried to reduce sexual contact with their spouses to a minimum and to avoid numerous pregnancies.19 Many members of the ruling class might be away from Rome for long periods of time, serving in administrative roles in the provinces, and this could further weaken the bonds between man and wife, especially if the wife chose to (or was instructed to) remain at home.

In these circumstances, Roman permissiveness in a colonial situation was exacerbated by the sexual limitations of the social strategies aimed at protecting the reputation of aristocratic marriages and by implication the legitimacy of the children that resulted from such unions. Much analysis of Roman sexuality had followed the sort of line expressed by Anthony Blond in the quotation that opens this section—specifically that, though different from today’s mores, it was permissive rather than violent. I believe, however, that we can locate the phenomenon of Roman permissiveness in a specific discourse of colonial sexuality and that this casts a new light on the violent and exploitative nature of some practices.

FIGURE 4.2 The objectification of female sexuality; brothel picture from Pompeii.

THE COLONIAL DISCOURSE OF SEXUALITY

Colonialism was a machine: a machine of war, of bureaucracy and administration, and above all, of power … enormous power put forth and resistance overcome … it was also a machine of fantasy and desire.20

Sex and desire in the ancient world have been studied from many angles, literary and artistic,21 but—notably—the terms colonialism and imperialism do not feature in the indexes of these works. However, that there have been colonial discourses of sexuality is made clear from work on modern empires.22 In modern colonialism, of course, the issue is intertwined with another larger and nastier one—that of race.23

FIGURE 4.3 “America” surprised in her hammock by Amerigo Vespucci, by Jan van der Straet (Giovanni Stradano). (Bridgeman-Giraudon / Art Resource, NY.)

The language and iconography of empire is full of sexual imagery and innuendo. Jan van der Straet’s famous image of a naked female “America” surprised in her hammock by Amerigo Vespucci is a classic example of the representation of the colonizer as armed male and the colonial territory as a vulnerable (and endangered) woman (see fig. 4.3).24 The scenes of Claudius with female personifications of Britannia and Armenia from the Sebasteion at Aphrodisias are likewise graphic depictions of violent conquest of female provinces by the armed emperor.25 Rape is implicit in all these scenes, as it is in numerous other scenes of Roman martial art, where (often bare-breasted) women captives are seized by the hair.26 As both Roy Porter and Dick Whittaker have argued, the Roman Empire generated a large volume of “phallic aggression” in its frontier regions.27

The discourse of sexuality is multidirectional and operates at different levels within society. As Robert Young notes, the desire for territory and dominance in the political field entrained another set of colonial desires: “In that sense, it was itself the instrument that produced its own darkest fantasy—the unlimited and ungovernable fertility of ‘unnatural’ unions.”28 The role of the state is thus an ambiguous one; its power and rapacity can encourage or enable individual colonial servants to behave in ways that threaten the very stability of the empire. So the colonial state is often found to be using its power to curb or discourage certain types of sexual activity that are made possible by the empire’s existence. Sexual discourse thus commonly involves imperial powers in mitigation strategies. Changing attitudes to sex, power, and the body in colonial situations are thus both a function and a consequence of empire. The work of Michel Foucault suggests some ways of addressing this discourse.

FOUCAULT ON SEX, POWER, AND THE BODY

It seems to me that power is always there, that one is never ‘outside’ it, that there are no ‘margins’ for those who break with the system to gambol in.29

Power is not simply what the dominant class have and the oppressed class lack. Power, Foucault prefers to say, is a strategy and the oppressed are as much a part of the network of power relations and the particular social matrix as the dominating.30

Much of Michel Foucault’s oeuvre—indeed, by far his most significant works (and his enduring reputation)—concern the philosophy of knowledge and power.31 Although in his formative works the word power was rarely used, Foucault could claim later that it was nonetheless the key and underlying theme all along.32

Several key points emerge. First, he suggested that power is not simply a negative force (power that “says no”): the “relations [of power] don’t take the sole form of prohibition and punishment, but are of multiple form.”33 Actually, he had modified his position on this issue, in his mature works stressing the empowering aspects of repressive power.34 There he envisaged power as a strategy, a network of relations that not only constrain but enable.35 Moreover, Foucault argued strongly that “all knowledge is embedded in power relations.”36 He also warned against the use of simplistic oppositions: dominators/dominated—the power web is to be seen as more complex than that.37 Some of his finest work concerned the minute analysis of the societal changes that brought about new structures of discipline and control, the asylum and the prison (although he eschewed historical specificity at one level, many of his works focused on the peculiar conditions of the eighteenth century).38 Here power was represented as power over others, the power of surveillance and discipline, but it was still not a wholly repressive force. Rather, it created new conditions and relations.

What are the weaknesses of Foucault’s approach to the “microphysics of power”? Several critics have found that while identifying the significance of power networks, Foucault had scrupulously avoided analyzing in detail the historical contingency of the structures he identified.39 Others have seen his vision of the nature of power as too fatalistic and negative.40

In a particularly interesting critique, Edward Said has suggested that Foucault was far more concerned with power than with factors opposing it. Power presupposes resistance, and Said rightly questioned Foucault’s commitment to the study of this aspect.41 Said suggests that there are four ways of thinking about power:

1. imagine how you as an individual would use it if you had it;

2. imagine what you would imagine if you had it;

3. assess the power needed to vanquish present power;

4. imagine things that cannot be commanded by the present extent of power.42

According to Said’s analysis, Foucault had largely written on aspects 1 and 2, ignoring 4 (the utopian vision) altogether and neglecting 3. To these criticisms, Madan Sarup adds the failure of Foucault to develop a more specific analysis of the broad concept of power or of the state and its infrastructure.43

When we turn to Foucault’s writings on sex and sexuality, power is once again a dominant theme. Although the relationship between power and sex is characterized by repression and prohibition, he is also adamant that sexuality is not a natural condition but the product of power (more so than sexuality is repressed by power): “sexuality is not an animate or natural quality of the body but is, in fact, an historically specific effect of the operations of different regimes of power on that body.”44 In other words, sexual mores and practices are not unvaried through human history, but are contingent on specific historical and social conditions. Thus, sexuality in any era will be a product of the “system of discourse.”45 As such, “sexuality becomes a dense transfer point for relations in power.”46

The manifesto of volume 1 of Foucault’s History of Sexuality promised much: he attacked the repressive hypothesis that saw the creation of sexuality as the product of nineteenth-century capitalism and made strong links between power and the body in the definition of sexuality.47 However, the second and third volumes are a disappointment, all the more so as they are devoted to ancient Greece and Rome—though Foucault acknowledges his lack of prior training and research in this area.48 In contrast to the prolegomena of volume 1, with its emphasis on the centrality of power, these later works reflect Foucault’s changing perspectives about sexuality and the body. Now Foucault asserted the importance of the self-fashioning body and the inner constitution of the individual and his pleasures (for it is mainly of “he” that Foucault wrote). This seems to have more to do with the author’s sudden awareness of his own fragile mortality than with the philosophical positions he had earlier created so brilliantly, and these volumes have been criticized as a simplistic misrepresentation of the realities of the Greco-Roman world, based on highly selective use of sources.49

The body, whether written upon by experience or self-fashioning, takes center stage in these later works. But several commentators have noted that this strategy isolates the body from the “affective mechanisms of power” at work on it, which Foucault had earlier promised to study.50 If we are to make best use of Foucault’s frame of analysis, therefore, it is vital that the body is not separated from the power network within which it is situated. In what follows I shall try to demonstrate the importance of the colonial discourse in shaping sexuality and societal power.

THE OPPORTUNITIES OF EMPIRES

Ronald Hyam has offered a brilliant analysis of the corrupting force of the opportunity of empire, focusing on the modern British experience.51 The colonial agent (predominantly male) had social, administrative, economic and, often, legal influence over subject men and women who came in contact with him.52 This power was easily translated into sexual opportunity—and not just by the unscrupulous. The opportunity was reinforced by strong desires, the product of (spatial, social, and moral) distance from home and by the hardships and inconveniences of life in remote territories.53 Colonial mythology created its own order of sexual delights, and the freedom from traditional restraints is a notable feature of the patterns of sexual behavior that resulted.54 Some modern colonial servants drew direct inspiration from imperial Rome in living out their fantasies. After his retirement from colonial service in the eighteenth century, General James Dormer had his house and garden at Rousham, Oxfordshire, embellished to reflect his lusty appreciation of Roman eroticism and the “confident bisexuality” of that age.55

Female prostitution and concubinage were routine devices for servicing desire without responsibility. The well-being and rights of these women and any offspring were highly insecure even when they were treated with some degree of gentleness. Pederasty is commonly attested, with some individuals seeking out young boys in a particularly predatory and promiscuous manner.56 Servants and slaves were routinely abused by masters as a right. There was much interest in experimentation and sexual license—take the lonely British official in India who, as opportunity presented itself, satisfied his urges with masturbation, boys, men, married women, servants, prostitutes, animals, and melons!57

Sodomy of men and women is a notable and repeated feature of the colonial sex life, and much of the former appears to have been opportunistic bisexuality rather than homosexuality.58 There is a long, cross-cultural history of sexual violence toward defeated enemies on the battlefield,59 but colonialism presented a more persistent threat of sexual humiliation of subject men and women. In a nasty racist pamphlet of the midnineteenth century titled Inequality of Races, Count Gobineau revealed the potential sadistic violence of colonial desire and the linkages among sexuality, mastery, and domination.60 Gobineau assigned gender characteristics to racial difference, writing of the “male” Aryan race in contact with the “female” black and yellow races. By subsuming both male and female native identities in a female (that is, passive) group, he emphasized the likelihood of white males being attracted to both. Colonial desire is thus exposed as a conduit for sexual license in situations where traditional constraints on sexual conduct fail and are replaced by new normative patterns of dominating behavior. In place of the safety and responsibility of marriage, sexual relationships in the colonial world are often characterized by “careless sensuality … frivolous, adolescent, reckless” behavior.61 Furthermore, the eroticism of empire entails a broader impact in society at large, also affecting sexual habits and outlook in the metropolitan country at the heart of the empire.62 As we shall see, in such cases colonial desire leads not only to licentiousness, but also to increased calls for morality to combat the perceived decline in personal standards.

LATIN SEXUAL VOCABULARY AND ROMAN SEXUAL PRACTICES

How does the Roman world fit in with such a model of colonial sexual discourse? Roman views on the body and its social and sexual functioning evolved over time, becoming increasingly male-oriented.63 The Latin sexual vocabulary was extensive and its content is highly instructive about the social context in which it was deployed.64 Despite the obvious anatomical similarities, it is soon apparent that this was a different world to our own.65 However, it is possible to perceive development and change in sexual attitudes. For example, the basic terms for the sexual organs and a number of the most common acts were of Latin origin, whereas the vocabulary for male same-sex relations was primarily derived from Greek terms, suggesting that the widespread experimentation with the latter was a secondary development in Roman sexuality following increased contact with the Greek world from the late third century BC. Learned in the East in a time of imperial conquest, “Greek love” took on a very different social meaning in Roman society to its traditional role in Greek societies.66

The penis (mentula) dominates the Latin sexual scene; indeed, the phallocentric nature of Roman societry is emphasized by the fact that there were 120 separate terms for the penis, far more than for the female genitalia.67 Phallic imagery included many religious uses (herms and other boundary markers, as a symbol against the evil eye, and as representations of the god Priapus (see fig. 4.4).68 In Latin literature it “is not treated as exciting disgust, so much as fear, admiration and pride. It was a symbol of power which might present a threat to an enemy.”69 Of the metaphorical synonyms of the penis, the largest grouping was that of weapons, whose sexual symbolism was instantly recognizable in an imperial world.70 By the same token, the metaphors for sexual intercourse are predominantly ones of striking, cutting, wounding, penetrating, digging, triumphing, dominating—typical soldier’s work.71

The vagina (cunnus) has a range of metaphorical synonyms, mainly connected with animals, fields, caves, ditches, and household objects,72 perhaps merely intended as descriptive or coincidentally also representing things the Roman man liked to have control over (land, animals, the household). Many of the descriptions of the female genitalia are unflattering, and some plain abusive, reflecting a strongly misogynist streak in the male writers. The rectum (culus) has a very similar range of metaphors to the vagina; indeed, many of the terms for cunnus were interchangeable with those for culus, suggestive of a certain sexual ambiguity between the two sites.73

FIGURE 4.4 Phallic imagery was very much “in-your-face” in ancient Roman society; here a street marker from Lepcis Magna, protecting townsfolk from the evil eye, not pointing the way to the nearest brothel.

This impression is reinforced when terminology for the three principal forms of sexual congress is considered. These were vaginal intercourse (fututio), anal intercourse (pedicatio) and oral intercourse (irrumatio), normally used in the active sense, but occasionally in their passive forms to describe (with derogatory undertones) the experience of the penetrated party. It is interesting to note that, once again, there are instances of fututio being used as a synonym for pedicatio of a male.74 There was also an active term for the act of performing oral sex on a man (fello), and this raises an important distinction not easily understood in the modern term fellatio. A fellator (m) or fellatrix (f) was someone of low social status who could provide the specific service of oral sex, but such an active response from the penetrated person was not always required or expected. The point is that oral penetration was not necessarily a consensual act; indeed, it was considered shameful and humiliating to have to submit to it. Oral intercourse was in many instances nothing less than oral rape. The Priapea poems clearly demonstrate by reference to the threats of Priapus against would-be-thieves from his orchard that oral rape was seen as much more shameful to the recipient than anal penetration.75 Performance of this act was as much about the humiliation of the passive partner at it was about the gratification of the active male.

A final point about vocabulary: Much humor and invective in Roman writing about sex depends on a perception of the genitals as unclean or foul. In particular, oral-genital contact was seen as a filthy act, leaving a bad-smelling mouth to mark out perpetrators.76 Cunnilingus was considered an even more shameful act for a free man to undertake than fellatio, echoing a strong sense of repugnance in descriptions of female genitalia in general.77 As Amy Richlin observes, the universally bad press accorded the vagina by male Latin authors is part fear of the unknown, part denial of value in a male-dominated society.78 In the same way, we may note that the surviving literature places value entirely on acts of male sexual gratification while placing opprobrium on acts designed to give pleasure to others. That is not to say that Romans did not ever value their women or that women were passive victims in Roman society.79 Lin Foxhall has suggested for the Greek world ways in which women could develop a very different construction of sexuality to that of their menfolk.80 I am sure that it also existed in the Roman world, but the essential point I wish to make here is that the dominant male view of sexuality was profoundly affected by the experience of imperial success. As we shall see in the next section, the massive increase in the availability of slaves to serve elite Roman households was a further factor in changing sexual behaviors.

The Importance of Social Status

A point that emerges time and again in looking at the Latin literature on sex is that it was not what one did that defined whether it was decent; rather, it was a question of whom one did it with and what role was played. Artemidorus, in his second century AD book The Interpretation of Dreams, presented a view of sexuality that was clearly not simply limited to the elite in society. Although discussing the portent of sexual dreams, many of the value judgments made by him about different sexual acts reflect this importance of social rank. As elsewhere in Roman literature, the sexual exploitation of slaves by the master of a household is taken for granted.81 In his helpful analysis of this account Foucault observed, “The sex of the partner makes little difference … what matters is that one is dealing with a slave.”82 On the other hand, there were property laws that prohibited messing around with someone else’s slave, though the well-known erotic escapade of Lucius and Photis in The Golden Ass suggests that ownership might not always have been respected.83 Men were commonly expected to pursue liaisons outside the home, with prostitutes and mistresses, though they were required to observe the laws of adultery protecting married women.84 In relations with men and boys, the Roman freeborn citizen could escape censure by taking the active role (see below) and by respecting certain social rules about such encounters.85

Looked at from another perspective, the judgment of an individual’s sexual behavior was often dependent on social status rather than specific knowledge. Thus, slaves and freedmen were generally presumed to have the stain of sexual submission and degradation about them, whether or not there was evidence to support this. Seneca summed up the distinctions neatly: “Unchastity is grounds for accusation in a freeborn man, a necessity for a slave, a duty [officium] for a freedman.”86 Note here that the continued sexual domination of freed slaves by their ex-owners was a recognized occurrence, whether as female concubine or passive male partner.

Another interesting sidelight on the sexual exploitation of slaves is provided by a recently published writing tablet from London that details the purchase of a slave girl called Fortunata (“or whatever name she is known by”) by a man called Vegetus.87 Vegetus was himself the slave of an imperial slave called Montanus, so the tablet in effect details three tiers of slaves owning others—in the case of both Vegetus and Montanus, as a result of their ability to accumulate a substantial savings account (peculium) from their lucrative work in imperial administration.

Active and Passive Roles and the Concept of Sexual Shame

The material … gives ample testimony that normal male sexuality was aggressive and active, also that it was directed at both male and female objects.88

The most vital aspect of sexual relations for a Roman man concerned his position and role in the act.89 As we have seen, the terminology prioritizes acts of penile penetration; indeed, it loads those acts with connotations of violent conquest and dominance. Women in ancient Rome were devalued in this formulation of sexual interaction, relegated to a passive, indeed submissive role. Roman matrons, no matter that they commanded respect in society, were not immune from the more extreme sexual demands of men. Martial’s famous epigram concerning a man trying to persuade his unenthusiastic wife to follow the lead of a clutch of wives of famous Romans in allowing him anal intercourse with her is one of the most striking pieces of evidence of the domestic impact of the sexual liberalization of Rome.90 The wife’s passivity, her prudery and lack of adventure are contrasted unfavorably with the man’s liking for drink, naked flesh under bright lights, and “abnormal” couplings. Perhaps unsurprisingly, by far the majority of Latin erotic literature deals with promiscuous sexual relations outside marriage.

On the other hand, a man taking on the passive role in sex adopted the woman’s part (muliebria parti) and submitted to another man’s power. While the Romans found nothing disgraceful in playing the active role in male-on-male pedicatio and irrumatio, submission to either form of penetration was a source of shame (stuprum) and degradation for a Roman citizen to have to undergo (see fig. 4.5). This shame might be slightly lessened if the active partner was someone of greater wealth or higher status, but if a person of equal or lower status it was far more damaging to reputation. To be sodomized or orally penetrated by another man was to be demeaned, while the act showed the superiority of the penetrator. Most discussions of the shaming nature of such relations have focused on the loss of reputation for upper-class Roman citizens who submitted to such acts. The Warren Cup, with its paired scenes of a man sodomizing a youth (see fig. 4.5) and two adult males of apparently similar status hard at it, hints that “Greek love” regularly extended beyond the pursuit of slave boys.91 What has been missed, I think, is the implication that such demeaning acts were frequently enforced by Roman citizens on subject males in the provinces (see fig. 4.6). Bisexual relations were very prevalent in Roman society and clearly played an important part in social power games as a consequence.92 The story reported by Tacitus of a Roman military commander in the Rhineland demanding from the local community a supply of young boys for his pleasure cannot have been an isolated case.93 It is an excellent example of the systemic side-effects of imperial power in operation.

FIGURE 4.5 Male youth being sodomized by an older man; relief decoration on the Warren Cup. (© The Trustees of The British Museum / Art Resource, NY.)

The law allowed wronged husbands a lot of leeway in dealing with adulterers caught in the act with their wives. Anal rape of the adulterer was seen as a fitting punishment, following the imagined retribution of Priapus.94 If the wronged man’s slaves also participated in the gang rape of the male transgressor the humiliation was made even worse and the revenge more complete.95 Not all Romans, of course, could go around physically dominating their enemies and acquaintances with acts of sexual violence, but it is notable that much of the extant Roman sexual graffiti and other obscene threats aimed at men contain orifice-specific promises to “fuck you.”96 Sexual violence was no doubt often latent rather than actual, but the close linkage between sexual power and sociopolitical power is clear from numerous examples in elite society of verbal attacks of a sexual nature on prominent people. Cicero subtly made a link between Clodius’s deviant sexual behavior and his poor reception in the theater.97 Much slander consisted of rumors that well-known Romans, even emperors, had played the passive role in male-male sex.98 Similar attitudes operated down the social scale.99

THE MORAL BACKLASH AND PURITY CAMPAIGNS

Not everyone misbehaves sexually in colonial society, though the scandals surrounding the worst miscreants have a long life.100 Indeed, many individuals may choose to register their protest against the decline in moral standards; in ancient Greece and Rome it was typically intellectuals and philosophers. Moreover, the state itself may take action to curb the worst excesses of individual licentiousness. In Augustan Rome, a wave of imperial edicts addressed moral standards and sexual misbehavior. While this might in part be seen as a recognition of the danger to colonial rule of sexual outrages (the rape of the daughters of Boudica in Britain was, after all, to be a contributing factor in the revolt of AD 60), the more immediate cause of this legislation would appear to be concern for the sanctity of aristocratic marriages. Female adultery in high society was to be harshly punished, male transgression similarly so when a married woman was involved and in general after the Augustan era male extramarital activity was more closely circumscribed. The effectiveness of these measures has been questioned,101 but Augustus was not afraid to take action and to set an example, even when it was his own daughter Julia at the center of scandal.

In the provinces, the conduct of governors and high officers of state was constrained by legislation prohibiting them from contracting marriages with provincial women while holding office. This measure was primarily designed to prevent governors using their power to coerce local heiresses into wedlock. It was also an extension of the protection of elite marriages, which were seen as crucial for the stability of society. Just how disruptive to provincial societies was the prospect of wealthy women being married off to outsiders is revealed in the famous trial of Apuleius at Sabratha in AD 158. Perhaps understandably in an age when love was not expected to feature in elite marriages, he was accused of witchcraft by the local aristocracy because he had successfully courted a local millionairess without being either particularly rich or powerful.102

The key concern of this sort of legislation was not to protect imperial subjects at large as much as it was to protect the status of aristocratic marriage. Similar moves in the British Empire went further, partly because of the issue of race. The purity case was forcefully put in the Pall Mall Gazette in 1887, where approximately 500,000 British people associated with or serving the empire overseas were castigated as almost entirely corrupted by sexual vice as a result of “immoral relations with the heathen.”103 Such views led to policies variously promoting earlier marriage of men to British women in the colonies, advocating chastity in cases where this was not possible, and in any event trying to discourage concubinage and interracial marriages.104 However, in neither the Roman nor the modern case could such reactions of the state entirely reign in the sexual forces unleashed by the colonial situation. Literature in the modern English imperial age often presents the “stubbornly nonsexual English gentlewomen” as the “antithesis of the teeming sexuality of empire and its torrid zones.”105 Here we may reflect on Foucault’s diagnoses that sexuality was not a natural condition, and that it was a product of power to a greater extent than it was repressed by power.106 The key point is that sexual exploitation of the colonial subject is not just about lust and desire, it is also about power and domination.

FIGURE 4.6 Still photograph from the original production of Howard Brenton’s play The Romans in Britain. The young Britons have just emerged from a swim and are about to encounter Roman sex and violence up close and personal. (Photograph by Alastair Muir; used with permission.)

PROSTITUTION, CONCUBINAGE, AND THE ARMY

The sexual behavior (and misbehavior) of individual Romans in the provinces represents only one strand of the colonial discourse of sexuality. Even greater importance may have attached to the sexual servicing of the Roman army, a matter in which the state could hardly be indifferent.107 Here we need to consider the harsh realities of ancient prostitution—much more sordid than the idealized couplings amid plush furnishings in the Pompeian paintings (see fig. 4.2)108—and commonly involving enslaved women.

From the reign of Augustus, service conditions for soldiers were standardized on extremely long terms (the age of enlistment was about eighteen, and soldiers normally served for twenty-five or twenty-six years). In the first centuries AD soldiers were not allowed to marry while in service, and though many might take concubines, children were not recognized by the state.109 Inscriptions make it clear that soldiers did often take unofficial wives and families, though typically these are recorded in the later stages of their service terms and not in the early years. Such partners were typically ten to twenty years younger then the soldiers who “married” them. In the earlier stages of their careers, soldiers seem to have demonstrated a greater degree of commitment phobia.

Clearly, the half million men under arms were hardly to be expected to live out their young lives in chaste sublimation of desire. The alternatives were all potentially threatening for morale and discipline: the use of prostitutes or slaves, unofficial marriages, and the rape of civilians, not to mention buggery in the barracks or masturbation in the milecastles. Centurions and higher-ranking troops might have been able to buy a slave girl—as was perhaps the case with the aptly named M. Cocceius Firmus, centurion at Auchendavy on the Antonine Wall.110 His was a complicated case, as he had inadvertently bought from foreign traders a (British?) girl who had earlier been condemned to hard labor in the saltworks prior to being carried off by brigands.111 However, buying a slave girl outright might cost the equivalent of a lower rank soldier’s annual salary, while buying a small amount of a sex slave’s time was more suited to the ordinary soldiery. It is likely that many prostitutes servicing the army were slaves, bought and controlled by individual entrepreneurs.

In the conquest phase, armies were allowed a fair amount of license to plunder and humiliate civilians. The testimony of the columns of Trajan and Marcus Aurelius is clear on this and, as noted already, imagery of rape is even utilized by the state in celebrating its own conquests, as in the famous Aphrodisias relief of Claudius “subduing” Britannia.112 The accusations against British and American service personnel in Iraq are therefore nothing new and would be less shocking to us if we acknowledged more openly the past history of the violent use of sex in imperial domination. On the contary, though, British public opinion has not always taken kindly to postcolonial criticism of imperialism. In 1980 the first performances of Howard Brenton’s play The Romans in Britain caused a sensation because of the staged rape of a male Briton by a group of Roman soldiers (see fig. 4.6).113 In part the outcry was provoked by this being a graphic and shocking piece of theatrical sex and violence, but for some this was compounded by the fact that parallels were being drawn between Roman imperialism and the modern experience of Northern Ireland being patrolled by British troops. The violence is the sort of plausible outrage that imperialism begets (and that we would prefer not to be reminded of). The revival of the play in February 2006 in Sheffield was timely, precisely because of current events in Iraq; indeed, the play’s run coincided with renewed allegations in the media about sexual abuse of civilians at the Abu Ghraib prison.114

Clearly, in the longer-term administration of a region, the power of the state needed to be used to channel and control such behavior without ever neutralizing its latent threat to the subject peoples. Given these conditions it is implausible that the Roman state did not seek to regulate to some extent the provision of sexual services for the army. At the very least, prostitutes would have been registered with the military authorities.115 But the interests of the state may have extended to proactive control of their numbers and availability,116 as the British army did in India (with seventy-five regimental brothels being set up in the mid-nineteenth century) and the Japanese in their Pacific empire—where a ratio of about one prostitute per forty men seems to have operated.117 If this ratio is applied to the Roman case study as an order of magnitude figure, the 500,000 troops of the second century AD would have required the services of 12,500 women; Britain, with a garrison of approximately 50,000, would have needed 1,250 women in close proximity to the garrison posts. Rather than “regimental brothels.” for which there is no evidence, we might envisage the issuing of contracts to individual entrepreneurs to lay on an appropriate numbers of girls at specified garrison posts. If we assume an average ten-year “career” for these women, this would suggest a total recruitment of 12,500 prostitutes in the course of a century in Britain alone (or 25,000 if the average working life was only five years). Perhaps as many women again would have been enslaved or pressed into prostitution in the towns of the province.118 In addition, longer-lasting relationships would have been formed by many soldiers with native women of free birth. Given the prevailing sexual ethos of Roman society, such concubinage may well have been exploitative and unstable (unofficial marriages may be an overoptimistic term). Native women in the frontier zone would also have been targets of amorous desire, harassment, and rape. Soldiers were seen as a real danger to women in some provinces—rabbinical texts, for instance, reveal that women captured by soldiers were assumed likely to have been raped, whereas with women taken hostage by brigands this was not necessarily the case.119 The rape by soldiers of the royal daughters of Boudica may have been a licensed and calculated act of humiliation, but it extended to a hitherto favored elite behavior that was no doubt commonplace at lower levels of society. The impact of Roman army morals and military occupation on women in a province like Britain would thus have been on a significant scale. How this affected the relationships between native British men and women is another issue again.

One of the most disturbing scenes on Trajan’s Column concerns the apparent torture of a group of naked Roman soldiers by Dacian women.120 R. R. R.Smith has argued to the contrary that the men were in fact Dacians being tortured by provincial women who had suffered during Dacian attacks.121 The scene is unexplained in extant literary sources, but either explanation raises the specter of sex, power, and violence, though with altogether different implications depending on the identity of the women. The sequel to the scene is to be found in the remorseless subjugation of the Dacians, the burning of villages, the slaughter of livestock, the execution of male Dacian prisoners, the seizure of Dacian women, and the dispatch of the sorry survivors into exile (see fig. 4.7).122 There are equally explicit scenes on the Aurelian Column, especially of German villages burned, civilians massacred, and bare-breasted women being grabbed by the hair in preparation for rape (see fig. 4.8).123 The true story of the “torturing Dacian Harpies/Roman women exacting just revenge” must have been tabloid news in Rome and among the troops at the time of the Dacian Wars. No doubt it was used in either case to justify the extreme violence meted out to their communities by the Roman army as the advantage was pressed home. But we should not ignore the possibility that these women, if they were Dacian, had been moved to their act of inhumanity by the enormity of violent acts already enacted by Roman soldiers on them and their families at earlier stages in the campaigns.

FIGURE 4.7 The frieze on Trajan’s Column: Roman soldiers burning a Dacian village, framed by Dacian casualties and fugitives of war and overlooked by a Roman camp (with totemic heads) and the emperor Trajan. (Photograph by Mary Harrsch; used with permission.)

SEX AND VIOLENCE: THE OPERATION OF POWER

Enslavement and sexual domination or humiliation were effective tools in undermining old power relations and in creating a new social hierarchy. At its most extreme, Roman sexuality was nasty, pornographic, misogynist, violent, dominating, and humiliating.124 Sexual humor in Roman society—typified by paintings from Pompeian bars and baths—was laced with allusions to power and humiliation.125 The same dubious qualities underlined much other entertainment in the Roman world. Public executions were played out as theater in the arena, and there was a vast array of violent or dangerous entertainment from boxing to gladiatorial combat, from animal baiting and hunting displays to circus races with spectacular crashes.126 As with sexual relations, the discourse of violence had a purpose—sustaining the social and political order through its exemplary use of force. Similar excess was demonstrated by increasing judicial savagery during the principate.127 Power in Roman society was indeed written on the body of its subject peoples, but in a selective and controlled manner.

FIGURE 4.8 The frieze on the Aurelian Column: violence against civilians; an old man pleads with Roman soldiers ransacking a German village.

Although sexual domination might seem to exclude and subjugate the individual, in reality the door was open for many provincials to pass through to the other side. Even the stigma of sexual shame had a limit on it. Slaves, freedmen, and freedwomen were condemned for their life to a lower social status because of their assumed uncleanliness as a result of having been the passive sexual partners of those of higher status (the argument of presumptive contamination again). Yet the character stain was not inherited in perpetuity and a son of a freedman could aspire—providing he had the financial means—to become part of local high society, to a place on the local town council, to a career in imperial service. Similarly, subject peoples, some of who may have endured sexual outrages in the conquest phase, could also choose to participate in the government and society of the empire.

However, these were not necessarily the choices of free agents, as imperial subjects were never outside the constraints of power. To take one’s place in Roman society involved a process of negotiation with the imperial authority (or with an individual representative of it). That negotiation and the choices taken by subject peoples (collectively or as individual bodies) were thus not made in a power vacuum. On the contrary, the power asymmetries in these colonial discourses influenced the behavior of both rulers and ruled. Many may have chosen ostensibly unsatisfactory courses of action because the alternatives were worse. For example, one might chose to be a soldier’s concubine not because one thought the army a terrific organization or because one liked the fancy uniforms or the individual man but because this was a way out of prostitution, or a potential meal ticket in an impoverished frontier region, or an acknowledgment of the latent power of the other party should he be rejected. Participation in the Roman Empire cannot then be read simply as compliance and approval. From this analysis, the historical contingency of Roman sexual relations is self-evident: the body (agency) cannot be divorced from the power networks of the society. Yet a purely structuralist approach is no more able to elucidate the critical issue of the negotiation of power; what is required is a more explicit body of theory on the nature and workings of power.

CONCLUSION

Roman sexual humor is often disturbing for the images it throws up, and Richlin’s analysis suggests that these may be indicative of a normalizing of extreme behavior—there are obvious similarities with modern-day pornography and violent male fantasy.128 In response to her statement that “it is impossible to ask the question ‘What end does this humour serve?’ without wonder and unease,”129 my conclusion is that it served a very specific function of power in the ancient world.

Changes in sexual practices in the Roman world, intensifying from the second century BC, and the development of an underlying ideology of active domination and passive submission, correlate chronologically with the rise of the overseas empire. The historical contingency of these practices identifies them as a specific discourse of Roman colonialism. Indeed, the similarity with the modern British case study is also striking and suggests that the power dynamics in these cases were similar, whatever the overt social, economic and political differences between ancient and modern imperialism. The inequality of status of the participants, the use of violent, degrading, and humiliating forms of sexual dominance on passive partners of both sexes; all this confirms that colonial desires can give rise to nonconsensual and asymmetrical sexual relations.

The experience of sex and power in the Roman world was widely discrepant along gender and social lines (that is, among man, woman, slave, freedperson, freeborn, citizen, noncitizen, soldier, civilian, rich, poor, etc. But those perspectives were all to some extent conditional on the power structure and the individual’s place within it. To accept that is to recognize that Foucault’s idea of the self-fashioning body is out of line with his own diagnosis of the contingency of power.

Earlier versions of this chapter have been presented at the Theoretical Roman Archaeology Conference in Sheffield, and in seminars at Leicester and Reading, England. The ideas have been substantially reworked and expanded for the Balmuth lecture. Special thanks go to Jane Webster for her comments on an early draft, and to Rob Young, who, knowing the track I was on, put vital reading matter in my path. Christine Kondoleon discussed some of the ideas with me in Boston and generously made available information on sexual imagery in the Roman collection of the Boston Museum of Fine Arts.

1 At an early stage I was much influenced also by Gramsci (1971) and his reflections on power and hegemony.

2 Scobie 1986, 407–9.

3 Blond 1994; Farrington 1994.

4 The precise details of what societies consider normal in sexual behavior differ wildly, of course, but in focusing on transgressive sexuality I am emphasizing aspects that many communities find moral or legal difficulty with in relation to their core membership—such as rape and other forms of sexual coercion, sexual humiliation, and exploitation based on social power inequalities. Attitudes to the sexual exploitation of those seen as marginal or inferior to the core society are often a different matter.

5 For instance, Dalby 2000, 10–13, highlights the fine distinction that might exist between the vices and the pleasures of empire and the social tensions that these created.

6 Edwards 1993.

7 Webster and Cooper 1996; Mattingly 1997a.

8 Cf. Webster 1996b.

9 Benjamin and Masters 1966, 42.

10 Blond 1994, 3

11 Edwards 1993.

12 Richlin 2006, is a wonderful attempt to construct a “Kinsey Report” of sorts on the Roman Empire, though it tends to be more descriptive of practices rather than analytical of why Roman sexuality evolved as it did.

13 Hallett 1988, 1270; cf. Schultz 2006 and Staples 1998 on the role of women in Roman religion.

14 For the evolution of Roman imperialism see, among others, Cornell 1995; Harris 1978, 1984; Lintott 1972; and chapter 1 of the present volume.

15 See Dalby 2000 for a thorough overview of the “empire of pleasures.”

16 See Veyne 1987, 34–35, on the difficulties of Roman wedding nights.

17 On Roman marriage in general, see Dixon 1992, 61–97; Rawson 1986, 1–57; Treggiari 1988.

18 Veyne 1987, 203.

19 Hallett 1988, 1276–77.

20 Young 1995, 98.

21 Clarke 1998, 2003b; Edwards 1993; Hallett and Skinner 1997; Kampen 1996; Kiefer 1932; Richlin 1983, 2006; Rousselle 1988; Skinner 2005; Taylor 1953; Veyne 1988; Vout 2007; Winkler 1990.

22 Gill 1995; Hyam 1990; Trexler 1995; Young 1995.

23 Fanon 1986; Young 1995.

24 See Whittaker 2004b, 115–16 for the image and discussion.

25 Ibid., 117–18.

26 Cf. Smith 1987, 116–17, which interprets Claudius as (merely) slaying Britannia and Armenia in the Aphrodisias reliefs.

27 Porter 1986, 232; Whittaker 2004b, 120, 128–29.

28 Young 1995, 98.

29 Foucault 1980, 141.

30 Hoy 1986b, 134.

31 Foucault 1975, 1979, 1980, 1981; see also Hoy 1986a; Giddens 1995, 199–215, 263–68; Goldstein 1994; Lemert and Gillan 1982, 32–91, 110–24; McNay 1994, 95–100.

32 Lemert and Gillan 1982, 58–59; Rabinow 1984 provides some good insights into the crystallization of Foucault’s writing on power.

33 Foucault 1980, 139, 142.

34 McNay 1994, 3.

35 Lemert and Gillan 1982, 77–78.

36 McNay 1994, 2; Sarup 1993, 73–75.

37 Foucault 1980, 142.

38 Foucault 1963, 1975.

39 Giddens 1995, 265; Hoy 1986b.

40 This tendency may, however, represent a misreading of his theoretical position; see Hoy 1986b, 144.

41 Conversely, however, Foucault did not investigate the nonjudicial forms of coercive power available to states either; see Sarup 1993, 83.

42 Said 1986, 151; cf. Sarup 1993, 81–82.

43 Sarup 1993, 84; see also Giddens 1995, 265–67.

44 McNay 1994, 9.

45 Sarup 1993, 70–72.

46 McNay 1994, 98; cf. Foucault 1981, 103.

47 Foucault 1981; cf. Lemert and Gillan 1982, 69–82; cf. Parker et al. 1992 for some exploration of the links between nationalism and sexuality.

48 Foucault 1985, 1988.

49 See Cohen and Saller 1994; Foxhall 1994; Halperin 1994; Poster 1986.

50 Foucault, in Lemert and Gillan 1982, 81.

51 Hyam 1990, 88–110.

52 MacMullen 1990, 190–97, offers some pertinent reflections on the limits of personal power in the Roman Empire.

53 Gill 1995, 57–87; Hyam 1990, 88–90.

54 The sexual connotations of orientalism are well known; see Said 1978, 179–97.

55 Mowl 2007, 68–76 (Tiberius would have approved).

56 One such was Kenneth Searight, who left a detailed account of his encounters with 129 boys during nine years’ army service in India; see Hyam 1990, 128–31.

57 Hyam 1990, 132–33.

58 Hyam 1990, 91–92, 212.

59 Trexler 1995.

60 Young 1995, 99–117, esp. 108.

61 Hyam 1990, 210. Paradoxically, the importation of British women into India, aimed at redressing the reliance on native prostitutes and concubines for satisfying the sexual needs of the British army and administration, had the unexpected effect of discouraging engagement with Indian languages and culture and resulted in an increasing distance between British officers and native sepoys, James 1997, 206–30.

62 Hyam 1990, 56–79.

63 Brown 1990, 1–25.

64 Adams 1982, lists eight hundred terms in his classic study; see also Richlin 1983, esp. 1–31.

65 Clarke 2003b, 11–15; Wiseman 1985, 1–14.

66 MacMullen 1990, 177–89, on Roman attitudes to Greek love.

67 Adams 1982, 9–79, esp. 77; cf. Johns 1982, 62–75, for a similar bias in iconographic representation.

68 See Parker 1988 for the Priapeia—poems celebrating the ithyphallic god.

69 Adams 1982, 77; cf. Parker 1988, 89, 105 for poems making explicit threats of sexual outrage against thieves from the orchard guarded by Priapus.

70 Adams 1982, 19–22.

71 Ibid., 145–49.

72 Ibid., 80–109.

73 Ibid., 96, 112–15.

74 Ibid., 118–30.

75 Parker 1988, 50, and poems 28 and 35.

76 Edwards 1993, 71; Richlin 1983, 26–27.

77 Kay 1985, 126–27.

78 Richlin 1983, 68–69.

79 Hemelrijk 1987.

80 Foxhall 1994.

81 Rousselle 1988, 82; cf. Hopkins 1979, 99–132, on the growth and practice of slavery.

82 Foucault 1988, 19.

83 Apuleius, The Golden Ass, 2.7–10, 16–18. As one of my anonymous reviewers has suggested, it is equally possible that Lucius was quite literally making an ass of himself in his behavior.

84 Rousselle 1988, 78–92.

85 Kay 1985, 118–20, 126–7, 163, 197; Richlin 1983, 34–44, 220–226; cf. Clarke 2003a, 163, for a more restrictive view suggesting that freeborn individuals were generally offlimits.

86 Seneca, Controversiae, 4.10.

87 Tomlin 2003.

88 Richlin 1983, 58.

89 Wiseman 1985, 10–14; Veyne 1987, 204–5.

90 Martial, Epigrams, 11.104; Kay 1985, 276–82; Richlin 1983, 159–60.

91 Clarke 2003a, 77–93.

92 Richlin 1983, 220–26; this is contra the views of Matthews 1995, which tends to view all male-male sex as evidence for homosexuality.

93 Tacitus, Histories, 4.14.

94 Parker 1988, poem 25.

95 Richlin 1983, 215.

96 Catullus, Poems, 10.

97 Cicero, Pro Sestio, 108–18; see also Parker 1999, 175–76.

98 Cicero, Philippics, 2.44–47, on Mark Antony; Suetonius, Caesar, 49–52, on Julius Caesar.

99 Edwards 1993.

100 Hyam 1990, 214–15.

101 Richlin 1983, 215–19.

102 See Mattingly 1995, 53, 123, for the circumstances. The real issue at stake was no doubt the fear of the nonlocal person making off with a fortune that the family had hoped to keep within its extended local group.

103 Hyam 1990, 91; cf. Gill 1995; Mason 1994.

104 Hyam 1990, 137–81.

105 Nussbaum 1995, 150–51.

106 Sarup 1993, 70–72.

107 Yet this has attracted surprisingly little scholarly attention; see Whittaker 2004b, 132–38.

108 Clark 2003b, 60–75, 121–31.

109 Dixon 1992, 92.

110 Birley 1979, 146.

111 Digest, 49.15.6.

112 See Ferris 1995.

113 Brenton 1989; Lawson 2005.

114 The story of how the transgressive abuses of power at Abu Ghraib occurred, with complicit negligence on the part of the U.S. command is told in Gourevitch and Morris 2008.

115 Prostitutes were registered in towns, where their activities were taxed; see Krenkel 1988, 1294.

116 Gill 1995, 121–41.

117 Hyam 1990, 121–29, 137–53.

118 On urban prostitution, see Krenkel 1988; Laurence 1994, 70–87; McGinn 2002; Vanoyeke 1990; and Wallace-Hadrill 1994, 43–55.

119 Potter 1999, 13; Isaac 1990, 85–86 (with references to the rabbinical texts).

120 Trajan’s Column scene XLV, 117 (Chichorius numbering); Ferris 2000.

121 Smith 2002, 79–81.

122 Burning of villages: Trajan’s Column scene XXV, 64; LVII, 141; LIX, 144; CLIII, 405). Slaughter of livestock: XXIX, 72. Execution of male Dacians: LVI, 140; LXXII, 183. Seizure of Dacian women: XXIX, 72. Refugees: LXXVI, 200–201, CLIV, 409–10.

123 Aurelian Column, scenes XCVII and XX. See Smith 2002, 78–83, for an extended discussion on the interpretation of scenes that to us appear to represent the horrors of war, but that in Roman eyes may have been intended simply to celebrate Roman justice being meted out on oath-breaking barbarians.

124 Richlin 1983, 77–80.

125 Clarke 2003a, 134–36, 160–70; 2003b, 116–33.

126 Hopkins 1982, 1–30; Kiefer 1932, 64–106.

127 Garnsey 1968; MacMullen 1990, 205–17.

128 Richlin 1983, 77–80.

129 Ibid., 80.