16 | IMAGE-GUIDED BRAIN STIMULATION

MARK S. GEORGE, JOSEPH J. TAYLOR, AND JAIMIE M. HENDERSON

GENERAL ISSUES IN BRAIN TARGETING IN PSYCHIATRY

This chapter builds on the prior chapter, which described the new methods for imaging the brain. With our ability to image the brain’s structure or function, we now have more sophisticated models, or maps, of how the brain works in health and disease. Luckily, in concert with the advances in brain imaging, there has been a steady expansion of new techniques that can focally stimulate the brain either invasively or noninvasively (Higgins and George, 2008). These new brain stimulation or neuromodulation methods work hand in hand with brain-imaging methods in order to determine where to stimulate or to examine the effects of stimulation (Sackeim and George, 2008). This chapter provides an overview of the ways in which the brain stimulation methods interact with, and even inform, brain imaging (Siebner et al., 2009). In particular, we will discuss the techniques where imaging is used to guide or target the stimulation. Before discussing the individual brain stimulation methods, there are several overview points needed in order to understand this exciting new area.

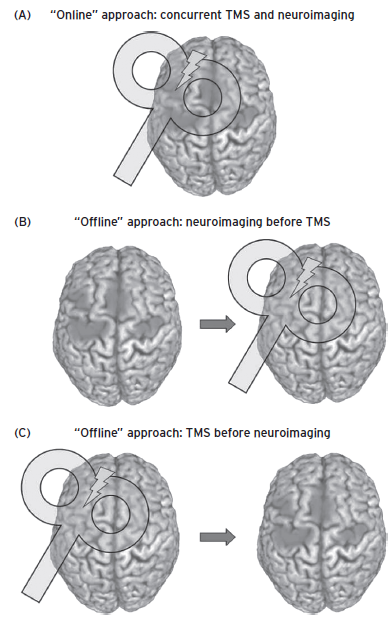

In combining brain stimulation and imaging, is the stimulation being done offline after the imaging (guided by structure or function), or offline before and after imaging using imaging to assess the effects of stimulation, or are the imaging and stimulation online and truly interleaved? Figure 16.1 highlights an important point in understanding how to classify or conceptualize the different ways of integrating brain stimulation and brain imaging (from Siebner et al., 2009). “Offline” means that the stimulation and imaging are occurring on different occasions. “Online” means that stimulation and imaging are occurring simultaneously. In the neurosurgical literature, “offline” scans are also referred to as historical scans, as opposed to “online” real-time or intraoperative scans.

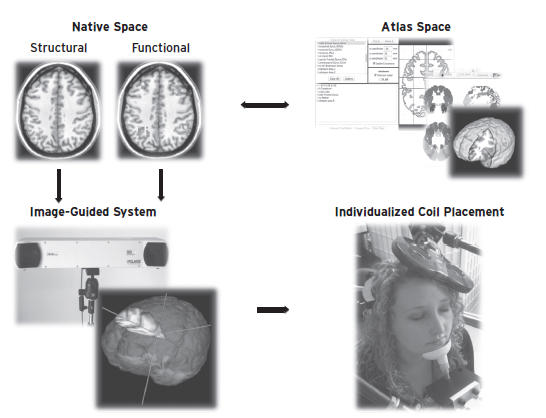

Perhaps the most common method to use imaging information to inform brain stimulation is to perform either a structural or functional scan on a patient or subject and then to use the offline scan to determine where to place the stimulation at a later time point. As we will discuss, there are many different ways to use an offline image to guide brain stimulation, and it is important to know the advantages and limitations of “image-guided” stimulation.

A less common offline approach is to perform the scan to assess the effects of the brain stimulation approach. This can involve either a single scan after the stimulation, or a scan immediately before and then again after the stimulation, subtracting the two scans to determine the effect of the stimulation.

Finally, in some situations one can actually perform stimulation at the same time as the brain is being stimulated. This online stimulation allows one to visualize and understand the effects of stimulation. Currently this can be done with positron emission tomography (PET), single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT), and functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI).

KEY POINT #2

When using scans to determine where to place the stimulation, it is important to remember that there are differences between brain structure and function, and the two do not necessarily overlap. Certain scans such as conventional computerized tomography (CT) or T1 MRI image the structure of the brain—its size and shape. Other scans reveal information about the function of the brain. These include images of blood flow (such as flow SPECT, oxygen [O15] PET, or the very common blood oxygen level–dependent [BOLD] fMRI technique) or metabolism (fluorodeoxyglucose [FDG] PET). It is important to realize that structure is not the same thing as function, and vice versa. One can have a brain region that appears normal structurally, but a small lacunar stroke at a distant location can make the function of broad areas of cortex change drastically. Similarly, one can have a vastly abnormal structural scan, say, congenital hemiatrophy, but with normal behavior and grossly normal brain function. It is thus important to understand which type of imaging information is present in a scan. Most commonly, areas of functional activation are overlaid onto a structural scan to allow more precise localization of function. Figure 16.2 depicts examples of different forms of imaging that can be used to guide or evaluate the brain stimulation methods.

KEY POINT #3

In the case of cortical stimulation, it can be difficult to identify homologous cortical structural sites across different individuals, in part due to morphological differences and varying gyral morphology. Identification of highly conserved areas such as the motor strip and primary visual cortical regions is relatively straightforward with high-field MR imaging. However, gyral morphology varies greatly across individuals. About one third of humans have only two prefrontal gyri, and thus, they do not by definition have a middle frontal gyrus. Even identical twins have widely varying gyral patterns (White et al., 2002). Thus, it may be difficult to guide brain stimulation methods to cortical regions based solely on a structural scan. For a full discussion of these issues (see Brett et al., 2002).

Figure 16.1 Different ways to combine imaging and stimulation. Image A shows the situation where the stimulation (in this case TMS) is being performed simultaneously with the imaging study. This is called “online” or real-time imaging. Image B shows the more common example where the information gathered in a separate scanning session, either structural or functional information, or both, is then used to position or target the location of the brain stimulation tool. This is called “offline imaging.” Image C shows another example of offline imaging where imaging is done after the stimulation, in order to understand the effects of the stimulation. (Reprinted with permission from Siebner et al. 2009.)

KEY POINT #4

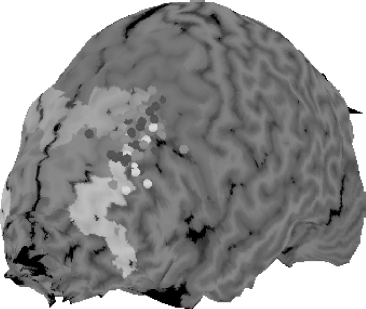

Finally, should targeting of functional areas be performed using a single scan from a single individual, or using pooled group means from many scans mapped onto an individual’s anatomy? On top of the variation in cortical structure, there is another problem where the functional location of a task varies as well across individuals. For example, the brain region that a given individual uses to solve cognitive tasks can vary widely. In part the common practice of pooling group activation studies into a common group image, and then displaying that on a structural scan in a common brain space, may have led the field to “overphrenologize” with respect to the cortical location, within individuals, that works to create a behavior. An example of this between-individual variation can be seen in Figure 16.3. Cigarette smokers were shown smoking-related cues while they were in an MRI scanner (Hanlon et al., 2012). Commonly these BOLD fMRI individual results would be averaged, and the results would be presented in a group image with one large area of mean activation. This would lead some to think that stimulation over the location in any given individual of the mean activation might actually influence craving. However, in Figure 16.2 we identified the actual peak locations for each individual. One can easily see the large variety of prefrontal brain regions used in this task. Thus, it may be that for certain behaviors we should do within-individual functional scanning in order to make sure that the stimulation method is in the correct location for that individual. There may be some locations that will stimulate a certain majority of individuals. There are additional concerns about the repeatability of the fMRI activation maps over time within individuals (Johnson et al., 2004), especially after they have learned or practiced a task.

With these guiding principles discussed or at least outlined, it is now worthwhile to examine exactly how the different brain stimulation methods have been combined with neuroimaging tools.

ISSUES FOR SPECIFIC BRAIN STIMULATION METHODOLOGIES

We will start with the least invasive of the brain stimulation methods, transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) and then proceed in terms of level of invasiveness, ending with deep brain stimulation (DBS). For each of these methods, we will discuss studies with offline scanning used to target or direct the device, then summarize studies with offline scanning illuminating what effect the device has on functional imaging scans, and finally discuss true online scanning.

TRANSCRANIAL DIRECT CURRENT STIMULATION

DESCRIPTION

tDCS involves placing two electrodes on the scalp and passing a small (usually 12 V) direct current between them. This remarkably simple technology has been around for over 100 years but has recently undergone a renaissance (Higgins and George, 2008). As current passes through the brain, it attempts to exit under the anode, causing the underlying cortex to become increasingly active (Nitsche et al., 2008). The opposite is true of the cathode. Areas under the cathode are largely inhibited in their function. If tDCS is applied to the scalp (and thus underneath to the brain), there is no immediately observable behavior change. In contrast to direct electrical stimulation, deep brain stimulation, or even transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS), from the standpoint of changed external behavior, nothing much happens during tDCS exposure. However, depending on the task being performed, and the region, tDCS can consistently either augment or subtly inhibit the activity within that brain region and thus influence performance and behaviors that rely on that brain region. Thus, tDCS is not really a brain stimulation method (stimulation here meaning directly causing neurons to depolarize due to an external stimulation) and is more of a neuromodulator (meaning that it changes the natural firing rates of a brain region). Some conceptualize the energy of tDCS like the effects of a catalyst on a chemical reaction. The presence of anodal tDCS requires less energy for the brain region to do its function (Molaee-Ardekani et al., in press; Nitsche et al., 2007, 2008; Pena-Gomez et al., 2011; Stagg et al., 2011).

Figure 16.2 These are different ways that one can go from an image to targeting the stimulation method. At the far left is a structural scan. Commercial systems can then directly position the stimulation method over the skull in order to accurately stimulate the intended region. Because this image remains in the person’s native space, there is little distortion and high fidelity. One can also overlay individual functional information directly onto the native space structural scan and use this to position the stimulation tool accurately for that person. Not uncommonly, however, researchers will have information gathered from multiple individuals. Because everyone’s head varies in size, researchers then stereotactically normalize this information into a common brain atlas such as the Talairach atlas or the MNI atlas. In order to stimulate within an individual, this group information must be reverse transformed back into the person’s native space and overlaid on their structural scan. This can then be targeted for brain stimulation using frameless stereotactic systems.

Figure 16.3 This figure illustrates the problem of between-individual variability in the functional location of various higher-order tasks. Much of the imaging literature consists of images like panel A on the left. This is the group mean area of activation for cigarette smokers who have been shown pictures of cigarettes. It is an area that is activated when they crave. It represents the mean, however. The panel to the right depicts each individual subject’s major area of activation during the task. The image on the right is thus the raw data that creates the image on the left. If you were to stimulate the region in the left panel, many of the patients might not have a change in their craving, because their functional circuit varies widely from the group mean (seen on the scatter image to the right). This problem lies at the heart of how to use imaging to guide the brain stimulation treatments in a variety of disorders. (Reprinted with permission from Hanlon et al., 2012.)

In general the pads are large, 2 × 2 cm sponges soaked in saline. These are secured on the head with straps. One group has developed a novel ring architecture that can provide more focal cortical stimulation, with the cathodes externally surrounding a central anode (Datta et al., 2008). However, even with this advance, tDCS is the most spatially crude of the current brain stimulation tools.

COMPUTER MODELS

Because of its simple design, with an MRI scan of a subject one can then model the likely flow of the tDCS current with different electrodes. This type of modeling was initially performed with time-intensive massive computers. Newer advances have reduced the time needed for these modeled maps.

OFFLINE TARGETING FOR PLACEMENT

Some investigators are using MRI image–generated maps to adjust the tDCS sponges in order to make sure current is flowing in the intended brain regions (see Datta et al., 2011; Turkeltaub et al., 2011)

OFFLINE IMAGING OF THE EFFECTS

Some of the most interesting imaging studies of tDCS have involved using MR spectroscopy to measure GABA or glutamate after subjects have received a standard tDCS dose. Excitatory (anodal) tDCS causes locally reduced GABA while inhibitory (cathodal) stimulation causes reduced glutamatergic neuronal activity with a highly correlated reduction in GABA (Stagg et al., 2009).

ONLINE INTERLEAVED SCANNING

There have not been many studies using tDCS during scanning, in part due to technical issues of artifacts, although there is one commercially available system (Pena-Gomez et al., 2011).

TRANSCRANIAL MAGNETIC STIMULATION

DESCRIPTION

Transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) allows for focal brain stimulation noninvasively from outside of the skull. An external electromagnet is pulsed and creates a powerful (1–3 T) magnetic field that passes unimpeded through the skull. When the magnetic field encounters neurons, it creates a charge in them and causes depolarization. Because the magnetic field declines exponentially with distance from the coil, most TMS coils are only able to stimulate the superficial areas of the cortex. There is ongoing debate about how to design coils that can penetrate deeper into the brain. Most researchers agree that there is a depth/focality tradeoff, meaning that the deeper in the brain one penetrates with TMS, the less focal one can be (Deng et al., 2012; Peterchev et al., 2011).

A single TMS pulse over the motor area can produce a twitch or movement in the contralateral body. The electrical dose needed within the electromagnet to cause a thumb twitch (called the motor threshold [MT]) varies considerably across individuals but is remarkably constant within an individual over time. Early MRI structural studies found that about 60% of the between-individual variance in MT is accounted for by the distance from the skull to cortex (Kozel et al., 2000; McConnell et al., 2001). It is harder to determine how much TMS energy is needed to stimulate other “behaviorally silent” brain regions outside of the motor strip. In early MRI work with elderly subjects, we determined that 120% of the MT would likely result in a prefrontal dose of TMS sufficient to excite the prefrontal cortex, and thus 120% MT is commonly used in TMS depression treatment (Nahas et al., 2004).

COMPUTER MODELS

The Deng study cited earlier is the most extensive series of computer models to date of TMS. In early work in the field, researchers were able to actually use the MRI scanner to image the magnetic field distortions caused by the TMS coil (Bohning et al., 1997).

OFFLINE TARGETING FOR PLACEMENT

There are now several commercial systems available that allow a researcher or clinician to match (“register”) a structural MRI scan of a patient to the location of the TMS coil on the head surface, enabling real-time guidance of the TMS coil for a research study or treatment session. One of these systems (Nexstim, Helsinki, Finland) has been FDA (U.S. Food and Drug Administration) approved for presurgical mapping of the motor areas, allowing for safer resective surgery. The fidelity of this system is less than 7 mm difference from direct cortical stimulation. That is, the area actually stimulated by the TMS coil is within 7 mm of where the system indicates it to be on the scan, as confirmed with intraoperative direct electrical stimulation. This system also has a graphical interface that “knows” the field strength of the TMS coil, and then calculates based on the subject’s gyral orientation and can render an approximation of the induced electrical field generated by the TMS coil held over the scalp in a certain orientation.

While the technology exists to guide TMS to specific cortical regions, the neuroscience question of where to stimulate for a specific behavior is much more complicated. As discussed earlier, there are within-individual variations in the location, between-session changes due to plasticity or learning, and the fundamental problem that complex behaviors often depend on the coordinated activity of a network of regions.

This issue can be illustrated in the current controversy about where to stimulate with figure 8 TMS coils in order to treat depression. The early TMS clinical studies used a crude system called the “5 cm rule” to find the prefrontal cortex location for stimulating. One of us (M.S.G.) developed this with other researchers in the early 1990s by consulting the Talairach atlas and reasoning that 5 cm anterior and in a parasagittal line from the motor thumb area would place the coil in the center of the prefrontal cortex (Brodman areas 9, 46). Thus, after finding the scalp location that best produced contralateral thumb twitching (which was needed in order to determine the motor threshold and determine the person’s dose), one could then put a cloth ruler on the scalp, find the prefrontal location, and proceed with treatment, without having to obtain an MRI and use formal image guidance. Unfortunately, this system did not take into account variations in head size or the location of motor cortex, and it likely results in 30% of patients being treated in the supplementary motor area, and not prefrontal cortex (Herwig et al., 2001). Thus, the field has now moved to systems using 6 cm, or based on the flexible EEG 10/20 system (Beam et al., 2009). An early analysis of imaging studies done in depression studies using the 5 cm rule found that more remitters received stimulation in anterior and more lateral locations (Herbsman et al., 2009) (see Fig. 16.4). A recent large study of the NIH OPT-TMS trial found that with the 5 cm rule, about 30% of patients needed the coil to be moved forward in order to be over prefrontal cortex. Even with this nudge forward, 7 patients still had stimulation in premotor areas. None of these 7 patients remitted from their depression with TMS, suggesting but not proving that they were stimulated in the wrong location (Johnson et al., 2012).

Figure 16.4 This figure illustrates the need for better positioning of the TMS coil for treating depression. David Avery and colleagues gathered structural MRI scans in all depressed patients being treated in double-blind trial of TMS for depression. The scalp location was determined using the rigid 5 cm rule, where the coil was placed 5 cm anterior from the best location for stimulating the thumb. Note the spread of the location when the data are all presented in a common atlas space. About one third of the patients were treated in supplementary motor areas (dark gray shaded areas). Patients who received placebo are in dark gray shaded circles. There were no placebo remitters. Patients who received active TMS are in light gray shaded circles, with active remitters in white shaded circles. The actively treated patients who remitted, on average, were treated at a location more anterior and more lateral than those who did not remit. This has led to adjustments in the way TMS coils are placed for treatment, with most methods now resulting in treatment more anterior and lateral than in early studies. (Reprinted with permission from Herbsman et al., 2009.)

Would personalized scanning be helpful in using TMS as a treatment for depression? This is an area where much more research is needed. A key issue is what task one would use to activate the intended treatment location. Affective regulation of response to pictures is one candidate that some researchers are exploring.

OFFLINE IMAGING OF THE EFFECTS

There have been many offline studies of the effects of TMS. It seems fairly clear that 10–20 minutes of treatment with high frequency TMS (10–20 Hz) causes increased activity (flow or metabolism) in local and connected regions in the brain. In contrast, 20 minutes of treatment with 1 Hz stimulation can cause the brain to temporarily decrease activity (Speer et al., 2000). These early PET studies mirrored the effects seen with TMS over the motor cortex measured electrophysiologically, and they are one of the cornerstones of knowledge about how to use TMS to temporarily excite or inhibit regional brain activity.

Additionally, important offline TMS studies include MRI scans performed before and after a course of treatment, showing no pathological changes in the brain as a function of treatment (Nahas et al., 2000). Finally, Baeken et al. (2011) performed PET scanning with a serotonin ligand before and after a course of daily left-prefrontal TMS. Successful rTMS treatment correlated positively with 5-HT(2A) receptor binding in the DLPFC bilaterally and correlated negatively with right-hippocampal 5-HT(2A) receptor uptake values. This type of imaging study reminds readers that the brain stimulation methods are really tools to change focal pharmacology (Baeken et al., 2011).

ONLINE INTERLEAVED SCANNING—COMBINING TMS WITH IMAGING

TMS can be performed inside the PET camera, producing truly interleaved online images of the local and distributed effects of the TMS pulse (Fox et al., 1997). Although there was initial controversy about the effect of the TMS pulse on the PET cameras, this has largely been resolved.

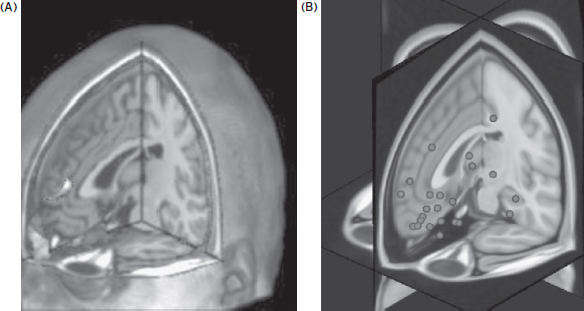

TMS can also be performed within an MRI scanner. This was initially thought to be impossible and unsafe, due to interactions between the TMS magnetic field and the MRI scanner’s field. There are some restrictions on what can be done (only figure 8 coils, biphasic pulses, etc.); however, truly interleaved TMS fMRI is possible (Bohning et al., 1999, 2000). These early imaging studies were important as they allowed researchers to determine the full brain effect of a TMS pulse. It appears that a TMS pulse results in brain metabolic changes that are similar in magnitude and extent to normal brain activity that results in a thought or produces a movement. Figure 16.5 shows the ways that interleaved TMS-fMRI can be used to precisely stimulate the appropriate region of the brain, and then, using the MRI scanner, to monitor the effects of the stimulation.

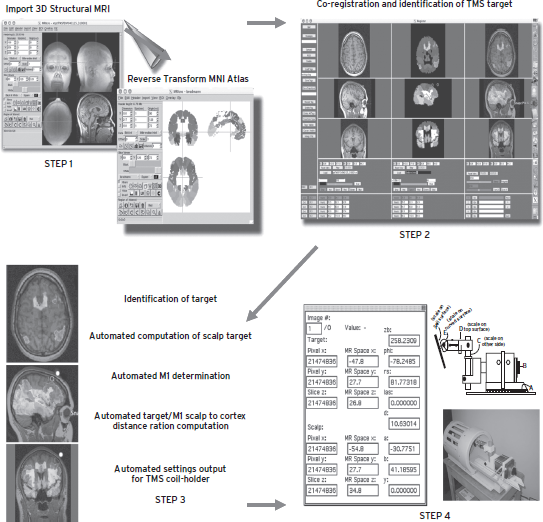

Figure 16.5 This image depicts how one can precisely position the TMS coil for accurate online stimulation within the scanner. Essentially, the person’s native-space MRI scan is seeded with the data that describe the different Brodman areas. One can then determine on the person’s scan, with the Brodman information loaded onto it, where to stimulate. These coordinates are then entered into a program that will calculate where on the scalp to position the coil, and that will then enter the correct adjustments to be made into the TMS coil holder. We call this “point and shoot.” This approach has been reduced to a robot for PET studies. It is difficult, though not impossible, to build robots that work within the MRI suite that might do the same thing.

DBS

DESCRIPTION

Deep brain stimulation involves implanting electrodes into subcortical structures for the treatment of neurological and psychiatric disorders. It has been used in various forms since the 1950s, although it has only been since the late 1980s that chronically implanted systems have been widely available (Hariz et al., 2010). A linear array of electrodes (known as a “lead”) is implanted into the target site using stereotactic surgical technique, and attached to an implantable pulse generator that provides continuous or intermittent pulsed electrical stimuli. Using an external programmer, the stimulation frequency, pulse width, and amplitude can all be dynamically adjusted. DBS is approved by the FDA for the treatment of Parkinson’s disease and tremor and is currently under investigation for use in the treatment of psychiatric disorders (Greenberg et al., 2008; Lozano et al., 2012).

COMPUTER MODELS

Stereotactic technique (from the Greek “στερεός,” meaning “solid,” and “τακτική,” meaning “ability in disposition”) is a method for introducing a therapeutic intervention to a particular three-dimensional location within the body, or more frequently, the brain. It involves correlating a target chosen from preoperative image modality (either an atlas made from histological slices or a volumetric CT or MRI scan) with the analogous location in the target organ of interest. DBS is thus an inherently image-guided therapy.

OFFLINE TARGETING FOR PLACEMENT

DBS electrodes are most commonly introduced using a stereotactic frame, which mounts to the patient’s head and provides mechanical adjustments in three orthogonal planes. A system of rods or markers, which can be imaged with MRI or CT (known as “fiducials”), provides a reference system that allows any point within the cranial volume to be precisely defined in three-dimensional space with reference to the base ring of the stereotactic frame. Once this target point is chosen, specialized software generates the settings for each axis, which are then entered into the frame. A burr hole is then made through the skull, and the lead is introduced to the target point using a trajectory guide mounted to the frame.

More recently, systems have been developed that provide real-time positional feedback without reliance on a stereotactic frame. Fiducial markers visible on both the patient and imaging studies are still required, but instead of defining an absolute coordinate system based on the frame, a process known as “registration” aligns the physical space of the operating room to the “image space” within the computer. Instruments are tracked through three-dimensional space by optical, sonic, or electromagnetic methods, allowing a less constrained approach to surgery. These so-called “image-guided” systems have been successfully used for DBS implantation (Henderson et al., 2004, 2005; Holloway et al., 2005).

OFFLINE IMAGING OF THE EFFECTS

DBS is commonly used as a continuous treatment modality, unlike rTMS or tDCS, which pulse intermittently, and thus could be thought of as being continuously “online.” Imaging modalities such as PET collect data over relatively longer timescales compared with fMRI or magnetic source imaging (MSI), and can be evaluated in both the on- and off-stimulation state. Many such studies have been carried out in patients undergoing DBS for various indications (Ballanger et al., 2009). PET has been successfully used to image the effects of DBS in the treatment of depression, showing normalization of prefrontal metabolic changes similar to those seen during other effective treatments (Mayberg et al., 2005).

ONLINE INTERLEAVED SCANNING

Since DBS systems consist of electrically conducting wires and electronic pulse generators, the introduction of strong magnetic fields such as those used for MRI scanning could induce current or heating. Patients with implanted DBS systems might thus be at risk for serious complications (Henderson et al., 2005), potentially limiting the use of functional MRI. Despite these concerns, several investigators have used fMRI to evaluate the effects of DBS in patients with movement disorders and chronic pain (Jech et al., 2001; Rezai et al., 1999; Stefurak et al., 2003). fMRI has thus far not been performed in patients undergoing DBS for the treatment of psychiatric disorders.

CONCLUSIONS AND THE FUTURE

The brain stimulation methods are now making an impact in clinical neuropsychiatric practice, with prefrontal TMS FDA approved for treating acute depression, and DBS approved for medication-resistant Parkinson’s disease. We have reviewed in this chapter how imaging informs the use of the stimulation methods. Brain images can either provide the road map that guides the placement of the stimulator or assess the effects of the stimulation. The two—imaging and stimulation—go hand in hand. Each improves the other. “Knockout or temporary lesion” stimulation studies can sometimes confirm or reject a brain behavior relationship suggested by pure imaging studies, which have problems attributing causality (Rorden et al., 2008). Just because a certain brain region is active on a scan at the same time as someone performs a behavior does not mean that that brain region is causing the behavior. The region could be causing the behavior, or responding to the behavior, or it could have nothing to do with the behavior and be merely correlational. Augmenting imaging studies with temporary knockout noninvasive stimulation studies can help in understanding how the brain works.

TOWARD A NEUROPSYCHIATRIC “CATH. LAB?”

In cardiology, rapid advances occurred when physicians were able to perform an intervention (placing a stent or expanding an artery) while simultaneously examining the effects of the stimulation. In the catheterization lab, cardiologists are constantly using fluoroscopy to image the heart while they are interacting with it. They are able to diagnose, intervene, reimage, reintervene, and so on, until they achieve full blood flow (or deem that a full open-heart bypass surgery is needed). Imagine where the field of cardiology would be without this fundamental ability to intervene and image simultaneously in the cath. lab. Is it possible to have a “neuropsychiatric cath. lab”? To a simple extent, this is already possible, and neurosurgeons or interventional neuroradiologists do investigate aneurysms and strokes in a catheter lab environment. But problems with blood flow are not the main issue in many neuropsychiatric diseases that are not caused by acute problems with blood flow. Rather, the problem is one of abnormal or pathological activity of a circuit or system (e.g., the fear circuitry in anxiety disorders, mood regulation circuitry in depression, motor movement in Parkinson’s disease, craving circuits in the addictions). Imagine having an imaging tool (like BOLD fMRI) that could quickly assess circuit behavior within an individual, and the psychiatrist or neurologist can then stimulate within the scanner in a manner that will produce long-term potentiation (LTP)–like or long-term depression (LTD)–like changes that would alter the function of the circuit. One could then immediately reimage the activity of the circuit with real-time output (Johnson et al., 2012) and continue to intervene until the circuit behaved normally. The studies reviewed in this chapter demonstrate that for some issues the field is not far from creating such an environment. However, in other areas, there is much work to be done before such a dream could be realized. Only more research will tell us if combined imaging/stimulation approaches might eventually treat some, many, or most psychiatric diseases.

DISCLOSURES

Dr. George has no equity ownership in any device or pharmaceutical company.

He does occasionally consult with industry, although he has not accepted consulting fees from anyone who manufactures a TMS device, because of his role in NIH and DOD/VA studies evaluating this technology. His total industry-related compensation per year is less than 10% of his total university salary.

Current or Recent (within past two years)

Pharmaceutical Companies

None

Imaging and Stimulation Device Companies

Brainsonix (TMS): Consultant (unpaid)

Brainsway (TMS): Consultant (unpaid), Research Grant

Cephos (fMRI deception): Consultant (unpaid), MUSC owns patent rights

Mecta (ECT): Consultant (unpaid), Research Grant

Neuronetics (TMS): Consultant (unpaid), company donated equipment for OPT-TMS trial, VA antisuicide study

Cervel/ NeoStim (TMS): Consultant (unpaid), Research Grant

NeoSync (TMS): Consultant (unpaid), Research Grant

PureTech Ventures (tDCS, others): Consultant

Publishing Firms

American Psychiatric Press: Two recent books

Elsevier Press: Journal Editor

Lippincott: One recent book and a second edition

Wiley: One recent book

MUSC has filed eight patents or invention disclosures in my name regarding brain imaging and stimulation.

Mr. Taylor has no conflicts of interest to disclose. He is funded by NIDA (1F30DA033748-01).

Dr. Henderson serves on the Advisory Board of Nevro Corp. (stock options) and Circuit Therapeutics (stock options). He has also served in a consulting role for Proteus Biomedical (stock options). Stanford University receives support from Medtronic, Inc. for education of a trainee in Stereotactic and Functional Neurosurgery, which Dr. Henderson directs.

REFERENCES

Baeken, C., De Raedt, R., et al. (2011). The impact of HF-rTMS treatment on serotonin(2A) receptors in unipolar melancholic depression. Brain Stimul. 4:104–111.

Ballanger, B., Jahanshahi, M., et al. (2009). PET functional imaging of deep brain stimulation in movement disorders and psychiatry. J. Cereb. Blood. Flow. Metab. 29:1743–1754.

Beam, W., Borckardt, J.J., et al. (2009). An efficient and accurate new method for locating the F3 position for prefrontal TMS applications. Brain Stimul. 2:50–54.

Bohning, D.E., Pecheny, A.P., et al. (1997). Mapping transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) fields in vivo with MRI. NeuroReport 8:2535–2538.

Bohning, D.E., Shastri, A., et al. (1999). A combined TMS/fMRI study of intensity-dependent TMS over motor cortex. Biol. Psychiatry 45:385–394.

Bohning, D.E., Shastri, A., et al. (2000). Motor cortex brain activity induced by 1-Hz transcranial magnetic stimulation is similar in location and level to that for volitional movement. Invest. Radiol. 35:676–683.

Brett, M., Johnsrude, I.S., et al. (2002). The problem of functional localization in the human brain. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 3:243–249.

Datta, A., Baker, J.M., et al. (2011). Individualized model predicts brain current flow during transcranial direct-current stimulation treatment in responsive stroke patient. Brain Stimul. 4:169–174.

Datta, A., Elwassif, M., et al. (2008). A system and device for focal transcranial direct current stimulation using concentric ring electrode configurations. Brain Stimul. 1:318.

Deng, Z.D., Lisanby, S.H., et al. (2012). Electric field depth-focality tradeoff in transcranial magnetic stimulation: simulation comparison of 50 coil designs. Brain Stimul. [Epub ahead of print.]

Fox, P., Ingham, R., et al. (1997). Imaging human intra-cerebral connectivity by PET during TMS. NeuroReport 8:2787–2791.

Greenberg, B.D., Gabriels, L.A., et al. (2008). Deep brain stimulation of the ventral internal capsule/ventral striatum for obsessive-compulsive disorder: worldwide experience. Mol. Psychiatry 15(1):64–79.

Hanlon, C.A., Jones, E.M., et al. (2012). Individual variability in the locus of prefrontal craving for nicotine: implications for brain stimulation studies and treatments. Drug Alcohol. Depend.

Hariz, M.I., Blomstedt, P., et al. (2010). Deep brain stimulation between 1947 and 1987: the untold story. Neurosurg. Focus 29.

Henderson, J.M., Holloway, K.L., et al. (2004). The application accuracy of a skull-mounted trajectory guide system for image-guided functional neurosurgery. Comput. Aided Surg. 9:155–160.

Henderson, J.M., Tkach, J., et al. (2005). Permanent neurological deficit related to magnetic resonance imaging in a patient with implanted deep brain stimulation electrodes for Parkinson’s disease: case report. Neurosurgery 57:E1063; discussion E1063.

Herbsman, T., Avery, D., et al. (2009). More lateral and anterior prefrontal coil location is associated with better repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation antidepressant response. Biol. Psychiatry 66:509–515.

Herwig, U., Padberg, F., et al. (2001). Transcranial magnetic stimulation in therapy studies: examination of the reliability of “standard” coil positioning by neuronavigation. Biol. Psychiatry 50(1):58–61.

Higgins, E.S., and George, M.S. (2008). Brain Stimulation Therapies for Clinicians. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press.

Holloway, K.L., Gaede, S.E., et al. (2005). Frameless stereotaxy using bone fiducial markers for deep brain stimulation. J. Neurosurg. 103:404–413.

Jech, R., Urgosik, D., et al. (2001). Functional magnetic resonance imaging during deep brain stimulation: a pilot study in four patients with Parkinson’s disease. Mov. Disord. 16:1126–1132.

Johnson, K.A., Baig, M., et al. (2012). Prefrontal rTMS for treating depression: location and intensity results from the OPT-TMS multi-site clinical trial. Brain Stimul.

Johnson, K.A., Hartwell, K., et al. (2012). Intermittent “real-time” fMRI feedback is superior to continuous presentation for a motor imagery task: a pilot study. J. Neuroimaging 22:58–66.

Johnson, K.A., Mu, Q., et al. (2004). Repeatability of within-individual blood oxygen level-dependent functional magnetic resonance imaging maps of a working memory task for transcranial magnetic stimulation targeting. Neuroscience Imaging 1:95–111.

Kozel, F.A., Nahas, Z., et al. (2000). How coil-cortex distance relates to age, motor threshold, and antidepressant response to repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation. J. Neuropsychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 12:376–384.

Lozano, A.M., Giacobbe, P., et al. (2012). A multicenter pilot study of subcallosal cingulate area deep brain stimulation for treatment-resistant depression. J. Neurosurg. 116:315–322.

Mayberg, H.S., Lozano, A.M., et al. (2005). Deep brain stimulation for treatment-resistant depression. Neuron 45:651–660.

McConnell, K.A., Nahas, Z., et al. (2001). The transcranial magnetic stimulation motor threshold depends on the distance from coil to underlying cortex: a replication in healthy adults comparing two methods of assessing the distance to cortex. Biol. Psychiatry 49:454–459.

Molaee-Ardekani, B., Marquez-Ruiz, J., et al. (2013). Effects of transcranial Direct Current Stimulation (tDCS) on cortical activity: a computational modeling study. Brain Stimul.

Nahas, Z., Debrux, C., et al. (2000). Lack of significant changes on magnetic resonance scans before and after 2 weeks of daily left prefrontal repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation for depression. J. ECT 16:380–390.

Nahas, Z., Li, X., et al. (2004). Safety and benefits of distance-adjusted prefrontal transcranial magnetic stimulation in depressed patients 55–75 years of age: a pilot study. Depress. Anxiety 19:249–256.

Nitsche, M.A., Cohen, L.G., et al. (2008). Transcranial direct current stimulation: state of the art 2008. Brain Stimul. 1:206–223.

Nitsche, M.A., Doemkes, S., et al. (2007). Shaping the effects of transcranial direct current stimulation of the human motor cortex. J. Neurophysiol. 97:3109–3117.

Pena-Gomez, C., Sala-Lonch, R., et al. (2011). Modulation of large-scale brain networks by transcranial direct current stimulation evidenced by resting-state functional MRI. Brain Stimul. 5:252–263.

Peterchev, A.V., Wagner, T.A., et al. (2011). Fundamentals of transcranial electric and magnetic stimulation dose: definition, selection, and reporting practices. Brain Stimul. 5:435–453.

Rezai, A.R., Lozano, A.M., et al. (1999). Thalamic stimulation and functional magnetic resonance imaging: localization of cortical and subcortical activation with implanted electrodes. Technical note. J. Neurosurg. 90:583–590.

Rorden, C., Davis, B., et al. (2008). Broca’s area is crucial for visual discrimination of speech but not non-speech oral movements. Brain Stimul. 1:383–385.

Sackeim, H.A., and George, M.S. (2008). Brain Stimulation—basic, translational and clinical research in neuromodulation: why a new journal? Brain Stimul. 1:4–6

Siebner, H.R., Bergmann, T.O., et al. (2009). Consensus paper: Combining TMS with neuroimaging. Brain Stimul. 2:58–80.

Speer, A.M., Kimbrell, T.A., et al. (2000). Opposite effects of high and low frequency rTMS on regional brain activity in depressed patients. Biol. Psychiatry 48:1133–1141.

Stagg, C.J., Best, J.G., et al. (2009). Polarity-sensitive modulation of cortical neurotransmitters by transcranial stimulation. J. Neurosci. 29:5202–5206.

Stagg, C.J., Jayaram, G., et al. (2011). Polarity and timing-dependent effects of transcranial direct current stimulation in explicit motor learning. Neuropsychologia 49:800–804.

Stefurak, T., Mikulis, D., et al. (2003). Deep brain stimulation for Parkinson’s disease dissociates mood and motor circuits: a functional MRI case study. Mov. Disord. 18:1508–1516.

Turkeltaub, P.E., Benson, J., et al. (2011). Left lateralizing transcranial direct current stimulation improves reading efficiency. Brain Stimul. 5:201–207.

White, T., Andreasen, N.C., et al. (2002). Brain volumes and surface morphology in monozygotic twins. Cereb. Cortex 12:486–493.