34 | NEURAL CIRCUITRY OF DEPRESSION

JOSEPH L. PRICE AND WAYNE C. DREVETS

This review of the neural systems that underlie mood disorders is divided into two main sections dealing with (1) the neuroanatomy of the neural circuits that have been implicated in mood disorders, largely taken from studies of non-human primates, and (2) observations on humans, largely taken from clinical studies. The first section describes circuits linking specific structures that have been implicated in mood disorders, including the ventromedial prefrontal cortex (VMPFC), amygdala and other limbic structures, ventromedial striatum, and medial thalamus. The second section reviews data from in vivo neuroimaging and postmortem neuropathological studies of humans with mood disorders in light of the relevant neural circuitry. Finally, observations from the neuroanatomical networks implicated in mood disorders are integrated into neurocircuitry-based models of the pathophysiology of mood disorders aimed at explaining the diverse neurobiological systems that are affected in these conditions and the potential mechanisms underlying neurosurgical and neuromodulation approaches that have proven effective in treatment-refractory depression.

HISTORICAL INTRODUCTION

It has been suggested since the early studies of Broca and Papez that a system of interrelated “limbic” structures, including the hippocampus and amygdala, the anterior and medial thalamus, and the cingulate gyrus, is centrally involved in emotion and emotional expression. Visceral reactions are tightly linked to emotion, often providing the means of emotional expression itself, and it is apparent that these structures are closely connected to visceral control areas in the hypothalamus and brainstem. More recent studies with effective neuroanatomical methods have now defined the circuitry related to emotion in sufficient detail that it is possible to recognize how disorders of this neural mechanism may underlie mood disorders (Price and Drevets, 2010).

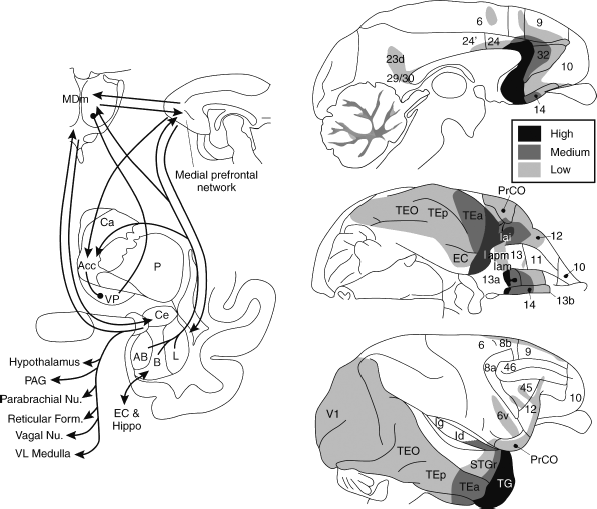

The amygdaloid complex of nuclei forms a focal point in the circuitry related to emotion. The connections of the amygdala therefore are a good starting point for understanding emotion-related circuitry. Experiments in rats, cats, and monkeys show that the basal and lateral amygdala have reciprocal connections to orbital and medial prefrontal, insular, and temporal cortical areas, as well as to the mediodorsal thalamic nucleus and the ventromedial striatum (Öngür and Price, 2000). Outputs to hypothalamic and brainstem areas involved directly in visceral control were also found from the central, medial, and other nuclei. These projections include not just the medial and lateral hypothalamus, but also the periaqueductal gray, parabrachial nuclei, and autonomic nuclei in the caudal medulla. The strongest prefrontal cortical projections of the amygdala are with the medial prefrontal cortex (PFC) rostral and ventral to the genu of the corpus callosum, but there are also amygdaloid projections to parts of the orbital cortex, the insula, and the temporal pole and inferior temporal cortex (Fig. 34.1). Other amygdaloid connections are with the entorhinal and perirhinal cortex and hippocampus (subiculum) (Amaral et al., 1992), and the posterior cingulate cortex (Buckwalter et al., 2008).

In the striatum, the amygdaloid projection terminates throughout the ventromedial striatum, including the nucleus accumbens, medial caudate nucleus, and ventral putamen (Öngür and Price, 2000). These striatal areas in turn project to the ventral and rostral pallidum, which itself sends GABAergic axons to the mediodorsal thalamic nucleus (MD). The perigenual PFC also projects to the same ventromedial part of the striatu, and is interconnected to the same region of MD (Öngür and Price, 2000; Price and Drevets, 2010). The connections constitute essentially overlapping cortical-striatal- pallidal-thalamic and amygdalo-striatal-pallidal-thalamic loops (Fig. 34.1). As discussed in the following, these circuits form the core of the neural system implicated in mood disorders.

PREFRONTAL CORTEX (PFC)

In the 1990s, a series of axonal tracing experiments in macaque monkeys more completely defined the cortical and subcortical circuits related to the orbital and medial PFC (OMPFC). Two connectional systems or networks were recognized within the OMPFC, which have been referred to as the “orbital” and “medial prefrontal networks” (Fig. 34.2). The areas within each network are preferentially interconnected with other areas in the same network, and also have common extrinsic connections with other structures (Öngür and Price, 2000) (see following).

Recently, a similar analysis has been made of the organization and connections of the lateral PFC (LPFC). Based on architectonic and connectional analysis, three regions can be recognized in monkeys: a dorsal prefrontal region dorsal to the principal sulcus (DPFC), which is similar to the medial prefrontal network, a ventrolateral region ventral to the principal sulcus (VLPFC), which is related to the orbital prefrontal network, and a caudolateral region just rostral to the arcuate sulcus (CLPFC), which includes the frontal eye fields and is probably part of an attention system (Öngür and Price 2000; Saleem et al., 2008).

Figure 34.1 Summary of amygdaloid outputs. Left: Diagram of amygdaloid circuits involving the striatum pallidum medial thalamus and prefrontal cortex and output to the hypothalamus and brainstem. Right: Diagram of areas of the cerebral cortex that receive axonal projections from the amygdala. The dark, medium, and lightly shaded areas represent high, medium, and low density of amygdaloid fibers. (Modified from Amaral et al., 1992, as reproduced by permission from Price and Drevets, 2011.)

ORBITAL PREFRONTAL NETWORK AND VLPFC

The orbital network consists of areas in the central and caudal part of the orbital cortex and the adjacent anterior agranular insular cortex (Fig. 34.2); it does not include the gyrus rectus, nor a small region in the caudolateral orbital cortex. The network is characterized by specific connections with several sensory areas, including primary olfactory and gustatory cortex, visual areas in the inferior temporal cortex (TEa, and the ventral bank of the superior temporal sulcus, or STSv), somatic sensory areas in the dysgranular insula (Id), frontal operculum (Opf), and parietal cortex (area 7b) (Öngür and Price, 2000; Saleem et al., 2008).

Neurophysiological studies have indicated that neurons in the orbital network areas respond to multimodal stimuli (e.g., the sight, flavor, and texture of food stimuli). Notably, these neuronal responses reflect affective as well as sensory qualities of the stimuli. Responses to food stimuli change with satiety (Pritchard et al., 2008; Rolls, 2000), and many neurons code for the presence or expectation of reward (Schultz et al., 1997) or the relative value of stimuli (Padoa-Schioppa and Assad, 2006). Further, lesions of the orbital cortex produce a deficit in the ability to use reward as a guide to behavior (Rudebeck and Murray, 2008). The orbital network therefore appears to function as a system for assessment of the affective value of multimodal stimuli.

The ventrolateral convexity of the LPFC, is closely related to the orbital network. This “VLPFC system” occupies the cortex ventral to the principal sulcus in monkeys, and includes areas 12l, 12r, 45b, and the ventral part of area 46 (Saleem et al., 2008). These areas are preferentially connected with each other, and to the areas of the orbital network. Further, they have most of the same extrinsic connections as the orbital network, including interconnections with the dysgranular insula, frontal operculum, area 7b, and inferior temporal cortex. The main difference from the medial network is that the VLPFC does not receive direct olfactory or gustatory inputs. These areas of the VLPFC may function to assess value of non-food sensory stimuli.

MEDIAL PREFRONTAL NETWORK AND DPFC

The medial network in the OMPFC is particularly significant for mood disorders. It consists of areas in the vmPFC rostral and ventral to the genu, areas along the medial edge of the orbital cortex, and a small caudolateral orbital region at the rostral end of the insula (Öngür and Price, 2000) (Fig. 34.2). The medial network receives few direct sensory inputs, but it has prominent connections with the amygdala and other limbic structures (Carmichael and Price, 1995a, b), and it is characterized by outputs to visceral control areas in the hypothalamus and periaqueductal gray (PAG). It can be considered a visceromotor system with strong relation to emotion and mood.

Figure 34.2 Maps of the orbital and medial surfaces of a human brain (above) and a macaque monkey brain (below), showing architectonic areas as defined in (Öngür et al., 2003) (human) and (Carmichael and Price, 1996) (monkey). The architectonic areas of the OMPFC are grouped into networks or systems based on connectional data (see text). The medial and dorsal prefrontal networks are shaded dark gray, while the orbital network is shaded light gray. Note that the “medial” network includes some areas on the medial orbital surface as well as areas Iai and 47s (the human homologue of monkey 12o), in the lateral orbital cortex. In addition, the regions referred to as the subgenual and pregenual anterior cingulate cortex (sgACC and pgACC) are indicated on the human brain with backwards or forwards slanted stripes.

The medial network is connected to a very specific set of other cortical regions, particularly the rostral part of the superior temporal gyrus (STGr) and dorsal bank of the superior temporal sulcus (STSd), the anterior and posterior cingulate cortex, and the entorhinal and parahippocampal cortex (reviewed in Price and Drevets, 2010). This corticocortical circuit is distinct from, but complementary to the circuit related to the orbital network.

The medial network is closely related to the areas of the DPFC, on the dorsal medial wall, and the dorsomedial convexity, including area 8b, area 9, the dorsal part of area 46, and the polar part of area 10 (Fig. 34.2). The DPFC is interconnected with itself and with the medial prefrontal network, but less with the VLPFC or CLPFC. It also is connected to the same set of extrinsic cortical areas as the medial network, including the anterior and posterior cingulate cortex, the rostral superior temporal gyrus, and the entorhinal and parahippocampal cortex. Further, there are outputs from areas of the DPFC to the hypothalamus and PAG, so this system can also modulate visceral functions.

The medial network, the DPFC, and the other cortical areas with which they connect, taken together, closely resemble the “default mode network” (DMN), which has been defined by fMRI and functional connectivity MRI (fcMRI) in humans (Raichle et al., 2001) (Fig. 34.3). The DMN is characterized as interconnected areas that are active in a resting state but decrease activity in externally directed tasks. This network has been linked to a variety of self-referential functions such as understanding others’ mental state, recollection, and imagination (Buckner et al., 2008).

CAUDOLATERAL PREFRONTAL CORTEX

The caudal part of the LPFC, the caudolateral prefrontal cortex (CLPFC) is largely unrelated to either the medial or orbital networks. It includes the frontal eye fields and adjacent cortex (areas 8av, 8ad, and caudal part of area 46 in the caudal part of the principal sulcus) (reviewed in Price and Drevets, 2010). The extrinsic connections of this system are with the dorsal premotor cortex, the posterior part of the dorsal STS (area TPT), and areas LIP and 7a in the posterior parietal cortex. The CLPFC may be part of the dorsal attention system (Raichle et al., 2001).

Figure 34.3 Anatomical circuits involving the medial and dorsal prefrontal networks, and the amygdala. Glutamatergic, presumed excitatory, projections are shown with pointed arrows, GABAergic projections are shown with round tipped arrows, and modulatory projections with diamond tipped arrows. In the model proposed herein, dysfunction in the medial prefrontal network and/or in the amygdala results in dysregulation of transmission throughout an extended brain circuit that spans from the cortex to the brainstem, yielding the cognitive, emotional, endocrine, autonomic, and neurochemical manifestations of depression. Intra-amygdaloid connections link the basal and lateral amygdaloid nuclei to the central and medial nuclei of the amygdala and the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis (BNST). Parallel and convergent efferent projections from the amygdala and the medial prefrontal network to the hypothalamus, periaqueductal grey (PAG), nucleus basalis, dorsal raphe, locus coeruleus, and medullary vagal nuclei organize neuroendocrine, autonomic, neurotransmitter, and behavioral responses to stressors and emotional stimuli (Davis and Shi, 1999; LeDoux, 2003). In addition, the medial prefrontal network and amygdala interact with the same cortical-striatal-pallidal-thalamic loop, through substantial connections both with the accumbens nucleus and medial caudate, and with the mediodorsal and paraventricular thalamic nuclei, which normally function to guide and limit responses to stress. Finally, the medial prefrontal network is a central node in the cortical “default mode network” (DMN) that putatively supports self-referential functions such as mood. Other abbreviations: 5-HT—serotonin; ACh—acetylcholine; Cort.—cortisol; CRH—corticotrophin releasing hormone; Ctx—cortex; NorAdr—norepinephrine; PVN—paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus; PVZ—periventricular zone of hypothalamus; STGr—rostral superior temporal gyrus; VTA—ventral tegmental area.

REGIONS WITH EXTENSIVE CONNECTIONS

TO MULTIPLE NETWORKS (AREA 45a and 47S)

Area 45a in the caudal-ventral PFC represents an exception to the dorsal, ventral, and caudal systems of the LPFC. Injections of axonal tracers into this area label connections with areas in all parts of the LPFC. The extrinsic connections resemble those of the dorsal and medial prefrontal systems, but also include the auditory parabelt and belt areas, as well as face areas in the ventral STS. Responses to both faces and species-specific auditory stimuli have been recorded in this region (Romanski, 2007; Tsao et al., 2008). Conceivably this region may represent a multimodal cortex that also is connected to circuits responsible for emotional processing.

AREA 12o/47S

Another area that appears to subserve a similar multimodal processing role with a strong link to emotional processing is area 12o/47s. In monkeys Walker designated the lateral orbitofrontal cortex as area 12, and four subdivisions subsequently were recognized within this cortex. Brodmann, however, designated approximately the same region in humans as area 47. Because the human area equivalent to the “orbital” part of area 12 (12o) in monkeys is not on the orbital surface but instead lies on the dorsal surface of the lateral orbital gyrus within the horizontal ramus of the lateral sulcus, this region was termed the sulcal part of area 47 (47s). Area 12o/47s shares extensive anatomical connections with several of the regions located on the medial wall (e.g., areas 25, 32pl, 24b, 10m) and in the anterior agranular insula (Iai) that form the medial prefrontal network. Area 12o/47s also projects to visceral control centers in the hypothalamus and periaqueductal gray, and receives auditory or polymodal input from the superior temporal sulcal region similar to the medial prefrontal network (reviewed in Öngür and Price, 2000). Thus area 12o/47s is considered part of the medial prefrontal network that subserves a “visceromotor” or “emotomotor” system that modulates visceral activity in response to affective stimuli. For example, the area corresponding to 47s coactivates within the subgenual ACC during induced sadness (Mayberg et al., 1999). Nevertheless, area 12o/47s also shares extensive connections with the orbital network, providing an interface between sensory integration and emotional expression (Öngür and Price, 2000).

CORTICAL PROJECTIONS TO HYPOTHALAMUS AND BRAINSTEM

Substantial outputs exist from the medial prefrontal network to the hypothalamus, PAG, and other visceral control centers, with the strongest projection from the subgenual cortex (Öngür and Price, 2000; Price and Drevets, 2010). The origin of the projection includes the STGr/STSd and area 9 in the DPFC, which are both connected to the medial network. Electrical stimulation of the medial PFC cause changes in heart rate and respiration, and fMRI studies show that activity in medial PFC correlates with visceral activation related to emotion (reviewed in Price and Drevets, 2010).

Lesions of the VMPFC in humans abolish the automatic visceral response to emotive stimuli (Bechara et al., 2000). Individuals with these lesions also are debilitated in terms of their ability to make appropriate choices, although their cognitive intelligence is intact. To account for such deficits, the “somatic marker hypothesis” proposes that the visceral reaction accompanying emotion serves as a subconscious warning of disadvantageous behaviors (Damasio, 1995). The full basis for this effect is complex, presumably involving the visceral reactions (e.g., sweaty palms, “butterflies” in the gut, etc.), subconscious “as-if” circuits, and circuits such as the cortical-striatal-pallidal-thalamic system. In mood disorders, overactivation of this system (e.g., due to excessive activity in the subgenual cortex) could produce the chronic sense of “unease” that is a common experiential component of depression.

CORTICAL-STRIATAL-THALAMIC CIRCUITS RELATED TO OMPFC

Like other cortical areas, the PFC has specific connections with the striatum and thalamus. These include reciprocal thalamocortical connections with the medial part of the mediodorsal thalamic nucleus (MDm). Closely related to these is the cortical-striatal-pallidal-thalamic loop through the ventromedial striatum and connections between the midline thalamic nuclei and the same striatal and cortical areas (Öngür and Price, 2000; Price and Drevets, 2010) (Figs. 34.3, 34.4, and 34.5).

MEDIAL SEGMENT OF MEDIODORSAL THALAMIC NUCLEUS

MDm receives substantial subcortical inputs from many limbic structures, including the amygdala, olfactory cortex, entorhinal cortex, perirhinal cortex, parahippocampal cortex, and subiculum (Öngür and Price, 2000). All of these areas also send direct (non-thalamic) projections to the OMPFC (Öngür and Price, 2000).

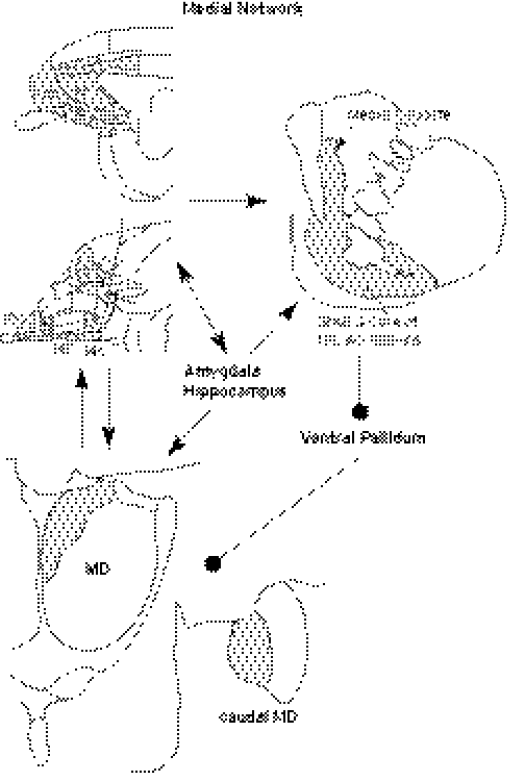

Figure 34.4 Illustration of the cortical-striatal-pallidal-thalamic loop related to the medial prefrontal network. Note that limbic structures such as the amygdala and hippocampus are also related to several parts of this circuit.

In addition to these inputs from limbic structures, which are excitatory and probably glutamatergic, MDm also receives GABAergic inputs from the ventral pallidum and rostral globus pallidus (Öngür and Price, 2000) (Figs. 34.3 and 34.4). It can be expected that these convergent but antagonistic inputs would interact to modulate the reciprocal thalamocortical interactions between the OMPFC and MDm. Limbic inputs would promote ongoing patterns of thalamocortical and corticothalamic activity and consistent behavior, while pallidal inputs would interrupt ongoing patterns, allowing a switch between behaviors involving mood, value assessment of objects, and stimulus-reward association. Indeed, lesions of the ventral striatum and pallidum, MD, or the OMPFC have been shown to cause perseverative deficits in stimulus-reward reversal tasks in rats and monkeys, where there is difficulty extinguishing responses to previously rewarded (Ferry et al., 2000). A similar deficit in subjects with mood disorders might be reflected by the difficulty in “letting go” of a negative mood or mind-set long after the resolution of any traumatic events that might have justified it.

Figure 34.5 A diagrammatic illustration of the cortical-striatal-pallidal- thalamic loop circuit, involving the medial prefrontal network and the amygdala, together with the ventromedial striatum (nucleus accumbens and medial caudate nuclei), the ventral and rostral globus pallidus, and the medial part of the mediodorsal thalamic nucleus (MDm). The midline paraventricular thalamic nucleus also has prominent connections with the medial network, the ventromedial striatum, and the amygdala, as well as with the hypothalamus and brainstem. The substantial connections from the medial network to the hypothalamus and brainstem are not shown in this figure. The shaded clouds depict areas where the targeted neuromodulation and neurosurgical treatments that have shown benefit in treatment-refractory depression would putatively influence white matter tracts within these circuits. A. Deep brain stimulation of the subgenual anterior cingulate (sgACC; Mayberg et al., 2005) and stereotaxic surgical ablations such as the anterior cingulotomy and prelimbic leukectomy would influence neural afferents and efferents of the sgACC as well as some projections running within the ventral cingulum bundle, thereby modulating or interrupting neurotransmission between the medial prefrontal network and the striatum, the amygdala and other limbic structures, as well as the hypothalamus, PAG, and brainstem stuctures. B. Deep brain stimulation of the ventral capsule/ventral striatum (Malone et al., 2009) and stereotaxic surgical ablations such as the subcaudate tractotomy would influence neural afferents to the ventral striatum emanating from the sgACC and other medial prefrontal network regions (Fig. 34.3) as well as from the amygdala and other limbic structures. C. Deep brain stimulation (Schlaepfer et al., 2008) or surgical lesions (i.e., anterior capsulotomy) administered within the anterior limb of the internal capsule would influence neural projections running between the medial prefrontal network and the mediodorsal thalamic nucleus. (Modified from Price and Drevets, 2012.)

PREFRONTAL PROJECTIONS TO THE STRIATUM

The OMPFC projects principally to the rostral, ventromedial part of the striatum. The orbital network areas connect to a relatively central region that spans the internal capsule, while the medial network areas project to the nucleus accumbens and the rostromedial caudate nucleus (Öngür and Price, 2000)(Fig. 34.4). The amygdala input to the striatum is essentially coextensive with that of the medial network. These striatal regions, in turn, project to the ventral pallidum, which projects to the portion of MDm that is connected to the medial network areas (Fig. 34.4).

MIDLINE “INTRALAMINAR” NUCLEI

OF THALAMUS

In addition to the prefrontal connections with MD, there also are connections with the midline-intralaminar nuclei of the thalamus, which include the paraventricular thalamic nucleus (PVT), and nuclei that extend ventrally on the midline. These nuclei are reciprocally connected to the medial prefrontal network areas, with little connection to the orbital network, and they have a substantial projection to the same areas of the ventromedial striatum that receives input from the medial network areas (Hsu and Price, 2007) (Fig. 34.4). They also have connections with the amygdala, hypothalamus, and brainstem areas, including the PAG (Fig. 34.3).

Considerable evidence links the PVT to the stress response. In particular, lesions of the PVT facilitate central amygdala neuronal responses to acute psychological stressors and block habituation to repeated restraint stress in rats (Bhatnagar et al., 2002). In humans, habituation to the stress response caused by recurrent hypoglycemia is associated with activity in the midline thalamus (reviewed in Price and Drevets, 2012). It is likely that the role of the PVT is general across many types of stressors.

OVERVIEW OF RECENT OBSERVATIONS IN HUMANS WITH MOOD DISORDERS

Converging evidence from neuroimaging and lesion analysis studies of mood disorders implicates the medial and orbital prefrontal networks along with anatomically related areas of the striatum, thalamus, and temporal lobe previously described in the pathophysiology of depression. Depressed subjects show abnormal hemodynamic responses in both networks during fMRI studies involving reward and emotional processing tasks (reviewed in Murray et al., 2010; Phillips et al., 2008). In addition, however, many of the prefrontal regions that compose the medial network and of the areas of convergence between the medial and orbital networks (i.e., BA 45a, 47s) contain reductions in gray matter and histopathological changes in neuroimaging and/or neuropathological studies of mood disorders. These data support extant neural models of depression positing that dysfunction within the medial network and anatomically related limbic and basal ganglia structures underlies the disturbances in cognition and emotional behavior seen in depression.

NEUROIMAGING ABNORMALITIES

IN MOOD DISORDERS

The neuroimaging abnormalities found in mood disorders generally have corroborated hypotheses regarding the neural circuitry of depression that were based initially on observations from the behavioral effects of lesions. Degenerative basal ganglia diseases and lesions of the striatum and orbitofrontal cortex increased the risk for developing major depressive episodes (Folstein et al., 1985; MacFall et al., 2001; Starkstein and Robinson, 1989). Because these neurological disorders affect synaptic transmission through limbic-cortical-striatal- pallidal-thalamic circuits in diverse ways, it was hypothesized that multiple types of dysfunction within these circuits can produce depressive symptoms.

BRAIN STRUCTURAL ABNORMALITIES

IN MOOD DISORDERS

Structural abnormalities found in the population of individuals with mood disorders can be distinguished broadly with respect to the age at illness-onset of the sample being considered. Patients with early-onset mood disorders (i.e., first mood episode arising within the initial four to five decades of life) manifest neuromorphometric abnormalities that appear relatively selective for areas within the OMPFC and anatomically related structures within the temporal lobe, striatum, thalamus, and posterior cingulate (reviewed in Price and Drevets, 2010). Cases with affective psychoses also have been differentiated from controls by gray matter loss within the OMPFC (Coryell et al., 2005; MacFall et al., 2001). In contrast, elderly subjects with late-onset depression (i.e., first mood episode arising later than the fifth decade of life) show a higher prevalence of neuroimaging correlates of cerebrovascular disease relative both to age-matched healthy controls and to elderly depressives with an early age at depression-onset (Drevets et al., 2004). MDD and BD cases that have either psychotic features or late-life illness-onset show nonspecific signs of atrophy, such as lateral ventricle enlargement.

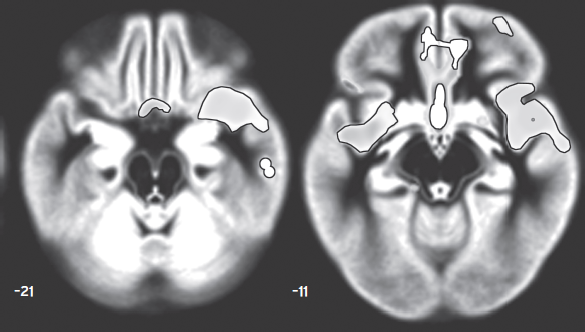

Within the OMPFC a relatively consistent abnormality reported in early onset MDD and BD has been a reduction in gray matter in left subgenual anterior cingulate cortex (sgACC). This volumetric reduction exists early in illness and in young adults at high familial risk for MDD, yet shows progression in longitudinal studies in samples with psychotic mood disorders (reviewed in Price and Drevets, 2010). Moreover, individuals with more chronic or highly recurrent illness show greater volume loss than those who manifest sustained remission (Fig. 34.6) (Salvadore et al., 2011). The abnormal reduction in sgACC volume primarily has been identified in mood disordered subjects with evidence for familial aggregation of illness (Hirayasu et al., 1999; Koo et al., 2008; McDonald et al., 2004), suggesting that genetic factors that increase risk for the development of depression also affect neuroplasticity within this region (e.g., Pezawas et al., 2005).

The subgenual cortex areas implicated by volumetric MRI or postmortem neuropathological studies of mood disorders include both the infralimbic cortex (BA 25; e.g. Coryell et al., 2005) and the adjacent sgACC corresponding to BA 24sg (e.g., Drevets et al., 1997; Öngür et al., 1998; Öngür et al., 2003)]. Reductions in gray matter also have been identified consistently in PFC regions that share extensive connectivity with this portion of the medial prefrontal network, such as the BA 47s cortex in BD (Lyoo et al., 2004; Nugent et al., 2006) and BA 45a area of VLPFC in MDD (Bowen et al., 1989), as well as in the caudal orbitofrontal cortex (BA 11), frontal polar/dorsal anterolateral PFC (BA 9,10), hippocampus, parahippocampus and temporopolar cortex in MDD, and in the superior temporal gyrus and amygdala in BD (Coryell et al., 2005; Lyoo et al., 2004; Nugent et al., 2006; Price and Drevets, 2010). Finally, the pituitary and adrenal glands appear enlarged in MDD (Drevets, Gadde et al., 2004; Krishnan et al., 1991), consistent with other evidence that hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis activity is elevated in mood disorders.

Discrepant results exist across studies, conceivably reflecting clinical and etiological heterogeneity extant within the MDD and BD syndromes. For example, in the hippocampus one study reported that reduced volume was limited to depressed women who suffered early-life trauma (Vythilingam et al., 2002), while others reported that hippocampal volume correlated inversely with time spent depressed and unmedicated (e.g., Sheline et al., 2003). In addition, the amygdala volume appears abnormally smaller in unmedicated BD subjects, but larger in BD subjects receiving mood stabilizing treatments associated with neurotrophic effects in experimental animals (Savitz et al., 2010).

Figure 34.6 Regions where gray matter volume was reduced in unmedicated, currently depressed subjects with major depressive disorder (N = 58) compared to unmedicated, currently remitted MDD subjects (N = 27). The mean time spent in the current major depressive episode for the former group was about four years, and the mean time spent in remission for the latter group was over three years. The depressed group showed reduced gray matter relative to the remitted group in the subgenual and ventromedial prefrontal cortices and the rostral temporal cortex, a pattern that resembles that depicting the density of amygdala projections to the cortex in Fig. 34.1. Results are superimposed on axial slices of the average gray matter map of the 192 subjects participating in this study. The axial slices are located at 21 mm and 11 mm ventral to the bicommissural plane. (Modified from Salvadore et al., 2011.)

NEUROPATHOLOGICAL CORRELATIONS WITH NEUROIMAGING ABNORMALITIES

The structural imaging abnormalities found in mood disorders have been associated with histopathological abnormalities in postmortem studies. Such studies report reductions in gray matter volume, thickness, or wet weight in the sgACC, parts of the orbital cortex, and accumbens (reviewed in Price and Drevets, 2010), and greater decrements in volume following fixation (implying a deficit in neuropil) in the hippocampus (Stockmeier et al., 2004) in MDD and/or BD subjects relative to controls. The histopathological correlates of these abnormalities include reductions in glia with no equivalent loss of neurons, reductions in synapses or synaptic proteins, and elevations in neuronal density, in MDD and/or BD samples in the sgACC, and of glial cell counts and density in the pgACC, dorsal anterolateral PFC (BA9), and amygdala (reviewed in Price and Drevets, 2010). The density of non-pyramidal neurons also appears decreased in the ACC and hippocampus in BD (Benes et al., 2001; Todtenkopf et al., 2005) and in the dorsal anterolateral PFC (BA9) in MDD (Rajkowska et al., 2007). Reductions in synapses and synaptic proteins were evident in BD subjects in the hippocampal subiculum/ventral CA1 region, which receives abundant projections from the sgACC (reviewed in Price and Drevets, 2010). Subjects with MDD studied postmortem also manifested dysregulation of synaptic function/structure related genes in the hippocampus and dalPFC, and with a corresponding lower number of synapses in the dorsolateral PFC (Duric et al., 2013; Kang et al., 2012). Notably, Kang et al. (2012) additionally identified a transcriptional repressor, GATA1, that was overexpressed in the dalPFC of MDD subjects, and that when expressed in PFC neurons is sufficient to decrease the expression of synapse-related genes, cause loss of dendritic spines and dendrites, and produce depressive behavior in rat models of depression.

The glial cell type implicated most consistently is the oligodendrocyte (reviewed in Price and Drevets, 2010). The concentrations of oligodendroglial gene products, including myelin basic protein, are decreased in frontal polar cortex (BA 10) and middle temporal gyrus in MDD subjects versus controls, potentially compatible with reductions in white matter volume of the corpus callosum genu and splenium found in MDD and BD. Perineuronal oligodendrocytes also are implicated in mood disorders by electron microscopy and reduced gene expression levels in PFC tissue. Perineuronal oligodendrocytes are immunohistochemically reactive for glutamine synthetase, suggesting they function like astrocytes to take up synaptically released glutamate for conversion to glutamine and cycling back into neurons.

CORRELATIONS WITH RODENT MODELS OF CHRONIC AND REPEATED STRESS

In regions that appear homologous to areas where gray matter reductions are evident in depressed humans (i.e., medial PFC, hippocampus) repeated stress results in dendritic atrophy and dysregulation of synaptic function/structure related gene expression, and these effects can be reversed at least partly by antidepressant drug administration (Banasr and Duman, 2007; Czeh et al., 2006; Duric et al., 2013; McEwen and Magarinos, 2001; Radley et al., 2008; Wellman, 2001). Dendritic atrophy putatively would be observed as a decrease in gray matter volume (Stockmeier et al., 2004). Moreover, both repeated stress and elevated glucocorticoid concentrations impair the proliferation of oligodendrocyte precursors in rodents, leading to reductions in oligodendroglial cell counts (Alonso, 2000; Banasr and Duman, 2007). In rats the stress-induced dendritic atrophy in the medial PFC was associated with impaired modulation of behavioral responses to fear-conditioned stimuli (Izquierdo et al., 2006), suggesting this process can alter emotional behavior.

The similarities between the histopathological changes that accompany stress-induced dendritic atrophy in rats and those found in humans suffering from depression suggest the hypothesis that homologous processes underlie the neuropathological changes in the hippocampal and medial PFC in both conditions (McEwen and Magarinos, 2001). Stress-induced dendritic remodeling depends on interactions between N-methyl-d-aspartate (NMDA) receptor stimulation and glucocorticoid secretion (McEwen and Magarinos, 2001). Notably, the depressive subgroups that show reductions in regional gray matter volume also show evidence of having elevated glutamatergic transmission in the same regions together with increased cortisol secretion (Drevets et al., 2002b). For example, cerebral glucose metabolism largely reflects energetic requirements associated with glutamatergic transmission (Shulman et al., 2004), raising the possibility that excitatory amino acid transmission contributes to the neuropathology of mood disorders (Paul and Skolnick, 2003). Elevated glutamatergic transmission in discrete anatomical circuits may explain the targeted nature of gray matter changes in depression (e.g., selectively affecting left sgACC) (Drevets and Price, 2005; McEwen and Magarinos, 2001; Shansky et al., 2009).

INTERRELATIONSHIP BETWEEN FUNCTIONAL AND STRUCTURAL NEUROIMAGING

IN DEPRESSION

The co-occurrence of increased glucose metabolism and decreased gray matter within the same regions in mood disorders has been demonstrated most consistently by comparing image data from depressed patients before versus after treatment (e.g., Drevets et al., 2002a) and from remitted patients scanned before versus during depressive relapse (Hasler et al., 2008; Neumeister et al., 2004). In resting metabolic images in contrast, the reduction in gray matter volume in some structures appears sufficiently prominent to produce partial volume effects due to their relatively low spatial resolution of functional brain images. Notably, in some depressed samples the resting metabolism appears reduced in the sgACC relative to healthy controls, while in contrast, other studies reported increased metabolic activity in the sgACC in primary or secondary depression, suggesting that these apparent discrepancies may be explained by differing magnitudes of gray matter loss across samples (reviewed in Drevets et al., 2008). Consistent with this hypothesis, in MDD and BD samples who show abnormal reductions of both gray matter volume and metabolism in the sgACC (Drevets et al., 1997), correction of the metabolic data for partial volume (atrophy) effects reveals that metabolism is increased in the sgACC in the depressed phase, and decreases to normative levels with antidepressant treatment. This finding is consistent with evidence that the sgACC metabolism decreases during symptom-remission induced by a variety of antidepressant treatments (Drevets et al., 1997, 2002a; Holthoff et al., 2004; Mayberg et al., 2000), including electroconvulsive therapy (Nobler et al., 2001) and deep brain stimulation (Mayberg et al., 2005).

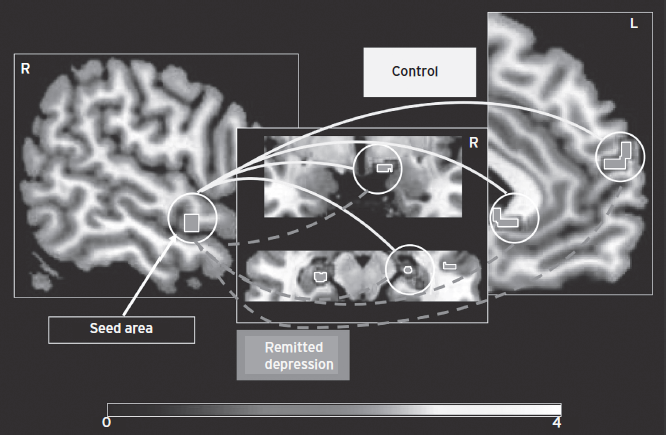

EMOTIONAL PROCESSING IN THE MEDIAL PREFRONTAL NETWORK

The sgACC participates generally in the experience and/or regulation of dysphoric emotion. In non-depressed subjects the hemodynamic activity increases in the sgACC during sadness induction, exposure to traumatic reminders, selecting sad or happy targets in an emotional go/no-go study, monitoring of internal states in individuals with attachment–avoidant personality styles, and extinction of fear-conditioned stimuli (reviewed in Price and Drevets 2010). Moreover, enhanced sgACC activity during emotional face processing predicted inflammation-associated mood deterioration in healthy subjects under typhoid vaccine immune challenge (Harrison et al., 2009). Finally remitted MDD subjects show decreased coupling between the hemodynamic responses of the sgACC, rostral superior temporal gyrus, hippocampus, and medial frontal polar cortex during guilt (self-blame) versus indignation (blaming others) (Green et al., 2010) (Fig. 34.7).

The ventral pgACC and vmPFC situated anterior to the sgACC have been implicated in healthy subjects in reward processing, and conversely in depressed subjects, in anhedonia (inability to experience pleasure in or incentive to pursue previously rewarding activities). In healthy humans the BOLD activity in this region correlates positively to ratings of pleasure or subjective pleasantness in response to odors, tastes, water in fluid-deprived subjects, and warm or cool stimuli applied to the hand, and the ventral pgACC shows activity increases in response to dopamine-inducing drugs and during preference judgments (reviewed in Wacker et al., 2009). Conversely in depressed subjects this region showed reduced BOLD activity during reward-learning and higher resting EEG delta current density (putatively corresponding to decreased resting neural activity) in association with anhedonia ratings (Wacker et al., 2009).

Figure 34.7 Regions showing decreased coupling with the right superior temporal gyrus during the experience of guilt versus indignation in individuals with remitted MDD compared with healthy controls, including the lateral hypothalamus, hippocampus, medial frontal polar cortex, and subgenual anterior cingulate cortex/septal region. The shaded bar depicts voxel t-values, computed using Statistical Parametric Mapping (SPM) software. (Modified from Green et al., 2010.)

More dorsal regions of the pgACC show physiological responses to diverse types of emotionally valenced or autonomically arousing stimuli. Higher activity in the pgACC holds positive prognostic significance in MDD, as depressives who improve during antidepressant treatment show abnormally elevated pgACC metabolism, MEG, and EEG activity prior to treatment relative to treatment-non-responsive cases or healthy controls (Pizzagalli, 2011).

Moreover, in the supragenual ACC depressed subjects show attenuated BOLD responses versus controls while recalling autobiographical memories (Young et al., 2012), associated with lower subjective arousal ratings experienced during memory recall. Behaviorally, MDD subjects are impaired at generating specific autobiographical memories, particularly when cued by positive words. These deficits were associated with reduced activity in the hippocampus and parahippocampus (Young et al., 2012).

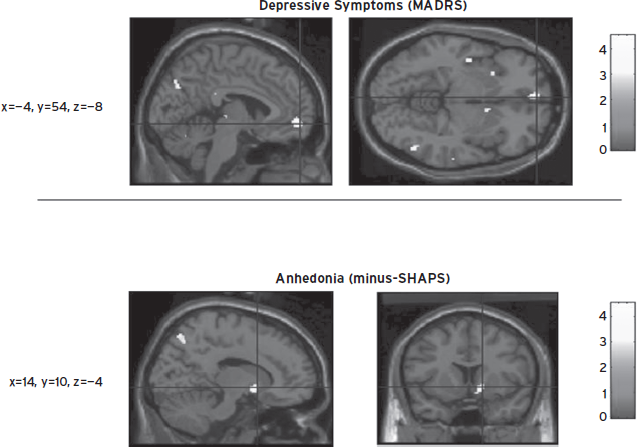

Notably, preclinical evidence indicates that distinct medial prefrontal network structures are involved in opponent processes with respect to emotional behavior (Vidal-Gonzalez et al., 2006). Regions where metabolism correlates positively with depression severity include the sgACC and ventromedial frontal polar cortex; metabolism increases in these regions in remitted MDD cases who experience depressive relapse under catecholamine or serotonin depletion (Hasler et al., 2008; Neumeister et al., 2004) (Fig. 34.8). In contrast, the VLPFC/lateral orbital regions that include BA45a, BA47s and the lateral frontal polar cortex show inverse correlations with depression severity, suggesting they play an adaptive or compensatory role in depression (reviewed in Price and Drevets, 2010).

FUNCTIONAL IMAGING OF LIMBIC STRUCTURES ASSOCIATED WITH THE

MEDIAL NETWORK

Subcortical structures that share extensive connections with the medial prefrontal network also show correlations to depressive symptoms. In the accumbens area the elevation of metabolism under catecholamine depletion correlates positively with the corresponding increment in anhedonia ratings (Fig. 34.8). In addition, fMRI studies show that hemodynamic responses of the ventral striatum to rewarding stimuli are decreased in depressives versus controls, and that higher levels of anhedonia are associated with blunted ventral striatal responses to rewarding stimuli in both healthy and depressed subjects (reviewed in Treadway and Zald, 2011). Furthermore, during probabilistic reversal learning, depressed subjects showed impaired reward (but not punishment) reversal accuracy in association with attenuated ventral striatal BOLD response to unexpected reward (Robinson et al, 2012).

Figure 34.8 Statistical parametric mapping image sections illustrating catecholamine depletion (CD)–induced metabolic changes and correlations between associated depressive symptoms and regional metabolism displayed on an anatomical MRI brain image in the voxel-wise analyses in a combined group of healthy controls and unmedicated individuals with major depressive disorder in remission (who are prone to develop depressive symptoms under CD produced via alpha-methyl-para-tyrosine administration). Upper Panel: Area where changes in metabolism correlated with CD-induced depressive symptoms (rated using the Montgomery-Asberg Depression Rating Scale) in the ventromedial frontal polar cortex, as shown by voxel t-values corresponding to p < 0.001 in the correlational analysis. Lower Panel: Area where glucose metabolism correlated with CD-induced anhedonia (rated by negative scores from the Snaith-Hamilton Pleasure Scale) in the right accumbens, shown as voxel t-values corresponding to p < 0.005. Coordinates corresponding to the horizontal and vertical axes are listed to the left of each image set, and correspond to the stereotaxic array of Talairach and Tournoux (1988) with the distance denoted in mm from the anterior commissure, with positive x = right of midline, positive y = anterior to the anterior commissure, and positive z = dorsal to a plane containing both the anterior and the posterior commissures. The gray shaded bars indicate voxel t values. (Reproduced by permission from Hasler et al., 2008.)

In the amygdala glucose metabolic abnormalities appear more selective for depressive subgroups. In the left amygdala, metabolism increased during tryptophan depletion-induced relapse only in MDD subjects homozygous for the long allele of the 5HTT-PRL polymorphism (Neumeister et al., 2006b). In addition, elevated resting amygdala metabolism was reported specifically in depressed subjects classified as BD-depressed, familial pure depressive disease (FPDD), or melancholic subtype (reviewed in Price and Drevets, 2010). These subgroups also shared the manifestation of hypersecreting cortisol under stress, which is noteworthy here because the amygdala plays a major role in driving the stressed component of cortisol release (Drevets et al., 2002). In contrast, task-based hemodynamic responses of the amygdala show a pattern of abnormalities reflecting negative emotional processing biases in depression that appear more generalizable across depressed samples.

FUNCTIONAL NEUROIMAGING CORRELATES

OF NEGATIVE EMOTIONAL PROCESSING BIAS IN MDD

Depressed individuals bias stimulus processing toward sad information as evidenced by enhanced recall for negatively versus positively valenced information on memory tests, greater interference from depression-related negative words versus happy or neutral words on emotional stroop tasks, faster responses to sad versus happy words on affective attention shifting tasks and more negative interpretation of ambiguous words or situations (reviewed in Victor et al., 2010). This bias also is evident in neurophysiological indices. Depressed subjects show exaggerated hemodynamic responses of the amygdala to sad words, explicitly or implicitly presented sad faces, and backwardly masked fearful faces, but blunted responses to masked happy faces (Suslow et al., 2010; Victor et al., 2010). A similar pattern of abnormal amygdala responses to masked sad and happy faces is observed in unmedicated-remitted subjects with MDD (Neumeister et al., 2006a; Victor et al., 2010) suggesting this abnormality is trait-like. Conversely, antidepressant drug administration shifts emotional processing biases toward the positive direction in both healthy and MDD samples (Geddes et al., 2003; Harmer, 2008; Victor et al., 2010). This shift is in the normative direction, as healthy subjects show a positive attentional bias (Erickson et al., 2005; Sharot et al., 2007; Victor et al., 2010) as well as greater amygdala responses to masked happy versus sad faces (Killgore and Yurgelun-Todd, 2004; Victor et al., 2010).

Taken together these data indicate that both the normative positive processing bias in healthy individuals and the pathological negative processing bias in MDD occur automatically, below the level of conscious awareness, and are mediated at least partly by rapid, non-conscious processing networks involving the amygdala (Victor et al., 2010). The differential response to masked-sad versus masked-happy faces in the amygdala is associated with concomitant alterations in the hemodynamic responses of the hippocampus, superior temporal gyrus, anterior insula, pgACC, and anterior orbitofrontal cortex (Victor et al., 2010). These regions may participate in setting a context or in altering reinforcement contingencies that conceivably may underlie these biases in MDD.

Similarly, during probabilistic reversal learning depressed MDD subjects showed exaggerated behavioral sensitivity to negative feedback versus controls, in association with blunted BOLD activity in the dorsomedial and ventrolateral PFC during reversal shifting, and absence of the normative deactivation of the amygdala in response to negative feedback (Taylor Tavares et al., 2008). Disrupted top-down control by the PFC over the amygdala thus may result in the abnormal response to negative feedback observed in MDD (Murphy et al., 1999).

IMPLICATIONS FOR NEUROCIRCUITRY-BASED MODELS OF DEPRESSION

Within the larger context of the limbic-cortical-striatal- pallidal-thalamic circuits implicated in the pathophysiology of depression, the basic science literature regarding specific limbic-cortical circuits involving the medial prefrontal network hold clear functional implications to guide translational models. The anatomical projections from the medial prefrontal network to the amygdala, hypothalamus, PAG, locus coeruleus, raphe, and brainstem autonomic nuclei play major roles in organizing the visceral and behavioral responses to stressors and emotional stimuli (Davis and Shi, 1999; LeDoux, 2003) (Fig. 34.4). In rats lesions of the medial PFC enhance behavioral, sympathetic, and endocrine responses to stressors or fear-conditioned stimuli organized by the amygdala (Morgan and LeDoux, 1995; Sullivan and Gratton, 1999). Nevertheless, these relationships appear complex, as stimulation of the amygdala inhibits neuronal activity in the mPFC, and stimulation of infralimbic and prelimbic projections to the amygdala excites intra-amygdaloid GABA-ergic cells that respectively inhibit or excite neuronal activity in the central amygdaloid nucleus (ACe) (Garcia et al., 1999; Likhtik et al., 2005; Perez-Jaranay and Vives, 1991; Vidal-Gonzalez et al., 2006).

For example, the amygdala mediates the stressed component of glucocorticoid hormone secretion by disinhibiting CRF release from the hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus (Herman and Cullinan, 1997). Moreover, lesions in the ventral ACC thus increase ACTH and CORT secretion during stress in rats, suggesting that the glucocorticoid response to stress is inhibited by stimulation of glucocorticoid receptors (GR) in this cortex (Diorio et al., 1993). Similarly, in monkeys Jahn et al. (2010) showed that PET measures of the subgenual PFC metabolism consistently predicted individual differences in plasma cortisol concentrations across a range of contexts that varied in stress load. It thus is conceivable that in humans with mood disorders dysfunction within the medial prefrontal network would disinhibit the efferent transmission from the ACe and BNST to the hypothalamus, contributing to elevated stressed cortisol secretion (Price and Drevets, 2010). Compatible with this hypothesis, cortisol hypersecretion in mood disorders has been associated with increased metabolic activity in the amygdala and with reduced gray matter in rostral ACC (Drevets et al., 2002b; Gold et al., 2002; McEwen and Magarinos, 2001; Treadway et al., 2009).

Furthermore, dysfunction of the medial prefrontal network may impair reward learning, potentially contributing to the anhedonia and amotivation manifest in depression. The ACC receives extensive dopaminergic innervation from the VTA and sends projections to the VTA that regulate phasic dopamine (DA) release. In rats, stimulation of these medial PFC areas elicits burst firing patterns in the VTA-DA neurons, while inactivation of the medial PFC converts burst firing patterns to pacemaker-like firing activity (reviewed in Price and Drevets, 2010). The burst firing patterns increase DA release in the accumbens, which is thought to encode information about reward prediction (Schultz et al., 1997). The mesolimbic DA projections from the VTA to the nucleus accumbens shell and the mPFC thus play major roles in learning associations between operant behaviors, or sensory stimuli and reward (Nestler and Carlezon, 2006). If the neuropathological changes in the ACC in mood disorders interfere with the cortical drive on VTA-DA neuronal burst firing activity, they may impair reward learning. Compatible with this hypothesis, depressives show attenuated DA release relative to controls in response to unpredicted monetary reward (Martin-Soelch et al., 2008) and fail to develop a response bias toward rewarded stimuli during reinforcement paradigms (reviewed in Treadway and Zald, 2011).

Furthermore, the patterns of physiological activity within the default mode system that involves the medial network are hypothesized to relate to self-absorption or obsessive ruminations (Grimm et al., 2009; Gusnard et al., 2001). In depressed subjects increasing levels of default mode network (DMN) dominance over the putative “task-positive network” (TPN; a group of structures that activate during volitional attention and thought) were associated with higher levels of maladaptive, depressive rumination and lower levels of adaptive, reflective rumination (Hamilton et al., 2011). Crucially, hemodynamic activity increased in the BA47s region in depressed subjects at the onset of increases in TPN activity. It thus was hypothesized that the DMN supports representation of negative, self-referential information in depression, and that activity within the vicinity of BA 47s in conjunction with increased levels of DMN activity may initiate an adaptive engagement of the TPN (Hamilton et al., 2011). Such an adaptive relationship potentially could explain the inverse correlation between depression severity and metabolic activity in BA 47s described previously. Notably, interpersonal psychotherapy, which can reduce depressive symptoms in MDD, enhanced activity in the vicinity of BA 47s (Brody et al., 2001; Öngür et al., 2003). Cognitive-therapeutic strategies for depression also have been hypothesized to depend on enhancing the function of neural substrates that serve as convergence zones between multiple prefrontal networks, such as BA 47s.

As described earlier, somatic antidepressant treatments also influence activity within the limbic-cortical-striatal-pallidal- thalamic circuitry. Such treatments reduce basal metabolic activity that putatively is pathologically elevated in some limbic and medial prefrontal structures. In addition, however, antidepressant drugs have been shown more specifically to reduce limbic responses to negative or sad stimuli, and in some cases, to additionally enhance such responses to positive stimuli (e.g., Victor et al., 2010). For example, functional imaging studies in depressed humans indicate that metabolism and blood flow decrease in the sgACC/vmPFC in response to chronic treatment with antidepressant drugs, vagus nerve stimulation, or deep brain stimulation of the sgACC or anterior capsule, and activity in the relevant limbic-thalamocortical circuitry also decreases during effective treatment with antidepressant drugs or electroconvulsive therapy (e.g., Mayberg et al., 1999; Mayberg et al., 2005; reviewed in Price and Drevets, 2010). Preliminary reports also indicate that chronic SSRI treatment or deep brain stimulation of the anterior capsule reduces the abnormally elevated metabolism in the accumbens area in MDD or in depression associated with obsessive-compulsive disorder (reviewed in Price and Drevets, 2010). Most notably, the observations that deep brain stimulation (DBS) and neurosurgical lesions placed within the circuits formed by these structures can alleviate treatment refractory depression (TRD) implicate directly the medial prefrontal network and its associated limbic, striatal, and thalamic targets in the mechanisms of antidepressant therapy.

Mayberg et al. (2005) initially demonstrated that DBS applied via electrodes situated in the white matter immediately adjacent to the sgACC produced antidepressant effects in TRD. This site was located in the vicinity of loci where neurosurgically placed lesions had shown efficacy in TRD in association with the prelimbic leukectomy procedure, and also would have involved some white matter tracts interrupted in the anterior cingulotomy procedure (Fig. 34.5). Similarly, Malone et al. (2009) showed that DBS administered within the accumbens area/ventral internal capsule improved depressive symptoms in TRD. This locus targeted by this procedure is in the vicinity of that affected by the subcaudate tractotomy procedure used for TRD. A third site where both DBS and neurosurgical lesions have shown efficacy in TRD is the anterior limb of the internal capsule, an area that had been surgically targeted by the anterior capsulotomy (Schlaepfer et al., 2008). Finally, a fourth site where DBS improved TRD in a single case report is the habenula, an epithalamic structure implicated in the pathophysiology of depression by both preclinical and human neuroimaging studies (Sartorius et al., 2010). Some of the major circuits in which these procedures putatively would modulate or interrupt neurotransmission in mood disorders are depicted in Figure 34.5.

The results of studies conducted using neuroimaging lesion analysis, and postmortem techniques support models in which the pathophysiology of depression involves dysfunction within an extended network involving the medial prefrontal network and anatomically related limbic, striatal, thalamic, and basal forebrain structures. The abnormalities of structure and function evident within the extended visceromotor network may impair this network’s roles in cognitive processes such as reward learning, emotional processing, and autobiographical memory, and may dysregulate visceral, behavioral, and cognitive responses to emotionally salient stimuli and stress, potentially accounting for the disturbances in these domains seen in mood disorders.

DISCLOSURES

Neither author has a potential conflict-of-interest related to this work.

Dr. Price was supported by grant R01 MH070941 from the USPHS/NIMH and Dr. Drevets by funds from the William K. Warren Foundation and by grant R01 MH0XXXX from the NIMH.

REFERENCES

Alonso, G. (2000). Prolonged corticosterone treatment of adult rats inhibits the proliferation of oligodendrocyte progenitors present throughout white and gray matter regions of the brain. Glia 31(3):219–231.

Amaral, D.G., Price, J.L., et al. (1992). Anatomical organization of the primate amygdaloid complex. In Aggleton, J.P., ed., The Amygdala: Neurobiological Aspects of Emotion, Memory, and Mental Dysfunction. New York: Wiley-Liss, pp. 1–66.

Banasr, M., and Duman, R.S. (2007). Regulation of neurogenesis and gliogenesis by stress and antidepressant treatment. CNS Neurol. Disord. Drug Targets 6(5):311–320.

Bechara, A., Damasio, H., et al. (2000). Emotion, decision making and the orbitofrontal cortex. Cereb. Cortex 10(3):295–307.

Benes, F.M., Vincent, S.L., et al. (2001). The density of pyramidal and nonpyramidal neurons in anterior cingulate cortex of schizophrenic and bipolar subjects. Biol. Psychiatry 50(6):395–406.

Bhatnagar, S., Huber, R., et al. (2002). Lesions of the posterior paraventricular thalamus block habituation of hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal responses to repeated restraint. J. Neuroendocrinol. 14(5):403–410.

Bowen, D.M., Najlerahim, A., et al. (1989). Circumscribed changes of the cerebral cortex in neuropsychiatric disorders of later life. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 86(23):9504–9508.

Brody, A.L., Saxena, S., et al. (2001). Regional brain metabolic changes in patients with major depression treated with either paroxetine or interpersonal therapy: preliminary findings. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 58(7):631–640.

Buckner, R.L., Andrews-Hanna, J.R., et al. (2008). The brain’s default network: anatomy, function, and relevance to disease. Ann. NY Acad. Sci. 1124:1–38.

Buckwalter, J.A., Schumann, C.M., et al. (2008). Evidence for direct projections from the basal nucleus of the amygdala to retrosplenial cortex in the Macaque monkey. Exp. Brain Res. 186(1):47–57.

Carmichael, S.T., and Price, J.L. (1995a). Sensory and premotor connections of the orbital and medial prefrontal cortex. J. Comp. Neurol. 363:642–664.

Carmichael, S.T., and Price, J.L. (1995b). Limbic connections of the orbital and medial prefrontal cortex in macaque monkeys. J. Comp. Neurol. 363:615–641.

Carmichael, S.T., and Price, J.L. (1996). Connectional networks within the orbital and medial prefrontal cortex of macaque monkeys. J. Comp. Neurol. 371:179–207.

Coryell, W., Nopoulos, P., et al. (2005). Subgenual prefrontal cortex volumes in major depressive disorder and schizophrenia: diagnostic specificity and prognostic implications. Am. J. Psychiatry 162(9):1706–1712.

Czeh, B., Simon, M., et al. (2006). Astroglial plasticity in the hippocampus is affected by chronic psychosocial stress and concomitant fluoxetine treatment. Neuropsychopharmacology 31(8):1616–1626.

Damasio, A.R. (1995). Descarte’s Error: Emotion, Reason, and the Human Brain. New York, London: Grosset/Putnam, Picador Macmillan.

Davis, M., and Shi, C. (1999). The extended amygdala: are the central nucleus of the amygdala and the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis differentially involved in fear versus anxiety? Ann. NY Acad. Sci. 877:281–291.

Diorio, D., Viau, V., et al. (1993). The role of the medial prefrontal cortex (cingulate gyrus) in the regulation of hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal responses to stress. J. Neurosci. 13(9):3839–3847.

Drevets, W.C., Bogers, W., et al. (2002a). Functional anatomical correlates of antidepressant drug treatment assessed using PET measures of regional glucose metabolism. Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol. 12(6):527–544.

Drevets, W.C., Price, J.L., et al. (2002b). Glucose metabolism in the amygdala in depression: relationship to diagnostic subtype and plasma cortisol levels. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 71(3):431–447.

Drevets, W.C., Gadde, K., et al. (2004). Neuroimaging studies of depression. In: Nestler, E.J., Charney, D.S., Bunney, B.J., eds. The Neurobiological Foundation of Mental Illness, 2nd Edition. New York: Oxford University Press, pp. 461–490.

Drevets, W.C., and Price, J.L. (2005). Neuroimaging and neuropathological studies of mood disorders. In: Wong, M.L., and Licinio, J., eds. Biology of Depression: From Novel Insights to Therapeutic Strategies. Weinheim, Germany: Wiley-VCH Verlag, vol. 1, pp. 427–466.

Drevets, W.C., Price, J.L., et al. (1997). Subgenual prefrontal cortex abnormalities in mood disorders. Nature 386(6627):824–827.

Drevets, W.C., Savitz, J., et al. (2008). The subgenual anterior cingulate cortex in mood disorders. CNS Spectr. 13(8):663–681.

Duric, V., Banasr, M., et al. (2013). Altered expression of synapse and glutamate related genes in post-mortem hippocampus of depressed subjects. Int. J. Neuropsychopharmacol. 16(1):69–82.

Erickson, K., Drevets, W.C., et al. (2005). Mood-congruent bias in affective go/no-go performance of unmedicated patients with major depressive disorder. Am. J. Psychiatry 162(11):2171–2173.

Ferry, A.T., Lu, X.C, et al. (2000). Effects of excitotoxic lesions in the ventral striatopallidal-thalamocortical pathway on odor reversal learning: inability to extinguish an incorrect response. Exp. Brain Res. 131(3):320–335.

Folstein, M.F., Robinson, R., et al. (1985). Depression and neurological disorders. New treatment opportunities for elderly depressed patients. J. Affect. Disord. Suppl. 1:S11–14.

Garcia, R., Vouimba, R.M., et al. (1999). The amygdala modulates prefrontal cortex activity relative to conditioned fear. Nature 402(6759):294–296.

Geddes, J.R., Carney, S.M., et al. (2003). Relapse prevention with antidepressant drug treatment in depressive disorders: a systematic review. Lancet 361(9358):653–661.

Gold, P.W., Drevets, W.C., et al. (2002). New insights into the role of cortisol and the glucocorticoid receptor in severe depression. Biol. Psychiatry 52(5):381–385.

Green, S., Ralph, M.A., et al. (2010). Selective functional integration between anterior temporal and distinct fronto-mesolimbic regions during guilt and indignation. NeuroImage 52(4):1720–1726.

Grimm, S., Boesiger, P., et al. (2009). Altered negative BOLD responses in the default-mode network during emotion processing in depressed subjects. Neuropsychopharmacology 34(4):932–843.

Gusnard, D.A, Akbudak, E., et al. (2001). Medial prefrontal cortex and self-referential mental activity: relation to a default mode of brain function. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98(7):4259–4264.

Hamilton, J.P., Furman, D.J., et al. (2011). Default-mode and task-positive network activity in major depressive disorder: implications for adaptive and maladaptive rumination. Biol. Psychiatry 70(4):327–333.

Harmer, C.J. (2008). Serotonin and emotional processing: does it help explain antidepressant drug action? Neuropharmacology 55(6):1023–1028.

Harrison, N.A., Brydon, L., et al. (2009). Inflammation causes mood changes through alterations in subgenual cingulate activity and mesolimbic connectivity. Biol. Psychiatry 66(5):407–414.

Hasler, G., Fromm, S., et al. (2008). Neural response to catecholamine depletion in unmedicated subjects with major depressive disorder in remission and healthy subjects. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 65(5):521–531.

Herman, J.P., and Cullinan, W.E. (1997). Neurocircuitry of stress: central control of the hypothalamo-pituitary-adrenocortical axis. Trends. Neurosci. 20(2):78–84.

Hirayasu, Y., Shenton, M.E., et al. (1999). Subgenual cingulate cortex volume in first-episode psychosis. Am. J. Psychiatry 156(7):1091–1093.

Holthoff, V.A., Beuthien-Baumann, B., et al. (2004). Changes in brain metabolism associated with remission in unipolar major depression. Acta. Psychiatr. Scand. 110(3:184–194.

Hsu, D.T, and Price, J.L. (2007). Midline and intralaminar thalamic connections with the orbital and medial prefrontal networks in macaque monkeys. J. Comp. Neurol. 504(2):89–111.

Izquierdo, A., Wellman, C.L., et al. (2006). Brief uncontrollable stress causes dendritic retraction in infralimbic cortex and resistance to fear extinction in mice. J. Neurosci. 26(21):5733–5738.

Jahn, A.L., Fox, A.S., et al. (2010). Subgenual prefrontal cortex activity predicts individual differences in hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal activity across different contexts. Biol. Psychiatry 67(2):175–181.

Kang, H.J., Voleti, B., et al. (2012). Decreased expression of synapse-related genes and loss of synapses in major depressive disorder. Nat. Med. 18:1413–1417.

Killgore, W.D., and Yurgelun-Todd, D.A. (2004). Activation of the amygdala and anterior cingulate during nonconscious processing of sad versus happy faces. NeuroImage 21(4):1215–1223.

Koo, M.S., Levitt, J.J, et al. (2008). A cross-sectional and longitudinal magnetic resonance imaging study of cingulate gyrus gray matter volume abnormalities in first-episode schizophrenia and first-episode affective psychosis. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 65(7):746–760.

Krishnan, K.R., Doraiswamy, P.M., et al. (1991). Pituitary size in depression. [see comments]. J. Clin. Endocrin. Met. 72(2):256–259.

LeDoux, J. (2003). The emotional brain, fear, and the amygdala. Cell. Mol. Neurobiol. 23(4–5):727–738.

Likhtik, E., Pelletier, J.G., et al. (2005). Prefrontal control of the amygdala. J. Neurosci. 25(32):7429–7437.

Lyoo, I.K., Kim, M.J., et al. (2004). Frontal lobe gray matter density decreases in bipolar I disorder. Biol. Psychiatry 55(6):648–651.

MacFall, J.R., Payne, M.E., et al. (2001). Medial orbital frontal lesions in late-onset depression. Biol. Psychiatry 49(9):803–806.

Malone, D.A., Jr., Dougherty, D.D, et al. (2009). Deep brain stimulation of the ventral capsule/ventral striatum for treatment-resistant depression. Biological. Psychiatry 65(4):267–275.

Martin-Soelch, C., Szczepanik, J., et al. (2008). Lack of dopamine release in response to monetary reward in depressed patients: An 11C-raclopride bolus plus constant infusion PET-study. Biol. Psychiatry 63(7 suppl):116S.

Mayberg, H.S., Brannan, S.K., et al. (2000). Regional metabolic effects of fluoxetine in major depression: serial changes and relationship to clinical response. Biol. Psychiatry 48(8):830–843.

Mayberg, H.S., Liotti, M., et al. (1999). Reciprocal limbic-cortical function and negative mood: converging PET findings in depression and normal sadness. Am. J. Psychiatry 156(5):675–682.

Mayberg, H.S., Lozano, A.M., et al. (2005). Deep brain stimulation for treatment-resistant depression. Neuron 45(5):651–660.

McDonald, C., Bullmore, E.T., et al. (2004). Association of genetic risks for schizophrenia and bipolar disorder with specific and generic brain structural endophenotypes. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 61(10):974–984.

McEwen, B.S., and Magarinos, A.M. (2001). Stress and hippocampal plasticity: implications for the pathophysiology of affective disorders. Hum. Psychopharmacol. 16(S1):S7–S19.

Morgan, M.A, and LeDoux, J.E. (1995). Differential contribution of dorsal and ventral medial prefrontal cortex to the acquisition and extinction of conditioned fear in rats. Behav. Neurosci. 109(4):681–688.

Murphy, F.C., Sahakian, B.J., et al. (1999). Emotional bias and inhibitory control processes in mania and depression. Psychol. Med. 29(6):1307–1321.

Murray, E.A., Wise, S.P., et al. (2010). Localization of dysfunction in major depressive disorder: prefrontal cortex and amygdala. Biol. Psychiatry. Epub ahead of print.

Nestler, E.J., and Carlezon, W.A., Jr. (2006). The mesolimbic dopamine reward circuit in depression. Biol. Psychiatry 59(12):1151–1159.

Neumeister, A., Drevets, W.C., et al. (2006a). Effects of a alpha 2C-adrenoreceptor gene polymorphism on neural responses to facial expressions in depression. Neuropsychopharmacology 31(8):1750–1756.

Neumeister, A., Hu, X.Z, et al. (2006b). Differential effects of 5-HTTLPR genotypes on the behavioral and neural responses to tryptophan depletion in patients with major depression and controls. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 63(9):978–986.

Neumeister, A., Nugent, A.C., et al. (2004). Neural and behavioral responses to tryptophan depletion in unmedicated patients with remitted major depressive disorder and controls. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 61(8):765–773.

Nobler, M.S., Oquendo, M.A., et al. (2001). Decreased regional brain metabolism after ect. Am. J. Psychiatry 158(2):305–308.

Nugent, A.C., Milham, M.P., et al. (2006). Cortical abnormalities in bipolar disorder investigated with MRI and voxel-based morphometry. NeuroImage 30(2):485–497.

Öngür, D., Drevets, W.C., et al. (1998). Glial reduction in the subgenual prefrontal cortex in mood disorders. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95(22):13290–13295.

Öngür, D., and Price, J.L. (2000). The organization of networks within the orbital and medial prefrontal cortex of rats, monkeys and humans. Cereb. Cortex 10(3):206–219.

Öngür, D., Ferry, A.T., et al. (2003). Architectonic subdivision of the human orbital and medial prefrontal cortex. J. Comp. Neurol. 460:425–449.

Padoa-Schioppa, C., and Assad, J.A (2006). Neurons in the orbitofrontal cortex encode economic value. Nature 441(7090):223–226.

Paul, I.A., and Skolnick, P. (2003). Glutamate and depression: clinical and preclinical studies. Ann. NY Acad. Sci. 1003:250–272.

Perez-Jaranay, J.M., and Vives, F. (1991). Electrophysiological study of the response of medial prefrontal cortex neurons to stimulation of the basolateral nucleus of the amygdala in the rat. Brain Res. 564(1):97–101.

Pezawas, L., Meyer-Lindenberg, A., et al. (2005). 5-HTTLPR polymorphism impacts human cingulate-amygdala interactions: a genetic susceptibility mechanism for depression. Nat. Neurosci. 8(6):828–834.

Phillips, M.L., Ladouceur, C.D., et al. (2008). A neural model of voluntary and automatic emotion regulation: implications for understanding the pathophysiology and neurodevelopment of bipolar disorder. Mol. Psychiatry 13(9):829:833–857.

Pizzagalli, D.A. (2011). Frontocingulate dysfunction in depression: toward biomarkers of treatment response. Neuropsychopharmacology 36(1):183–206.

Price, J.L., and Drevets, W.C. (2010). Neurocircuitry of mood disorders. Neuropsychopharmacology 35(1):192–216.

Price, J.L., and Drevets, W.C. (2012). Neural circuits underlying the pathophysiology of mood disorders. Trends Cogn. Neurosci. 16(1):61–71.

Pritchard, T.C., Nedderman, E.N., et al. (2008). Satiety-responsive neurons in the medial orbitofrontal cortex of the macaque. Behav. Neurosci. 122(1):174–182.

Radley, J.J., Rocher, A.B., et al. (2008). Repeated stress alters dendritic spine morphology in the rat medial prefrontal cortex. J. Comp. Neurol. 507(1):1141–1150.

Raichle, M.E., MacLeod, A.M., et al. (2001). A default mode of brain function. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98(2):676–682.

Rajkowska, G., O’Dwyer, G., et al. (2007). GABAergic neurons immunoreactive for calcium binding proteins are reduced in the prefrontal cortex in major depression. Neuropsychopharmacology 32(2):471–482.

Robinson, O.J., Cools, R., et al. (2012). Abnormal reward-related responses in the ventral striatum predict negative affective biases in depression. Am. J. Psychiatry 169(2):152–159.

Rolls, E.T. (2000). The orbitofrontal cortex and reward. Cereb. Cortex 10(3):284–294.

Romanski, L.M. (2007). Representation and integration of auditory and visual stimuli in the primate ventral lateral prefrontal cortex. Cereb. Cortex 17(Suppl 1):i61–69.

Rudebeck, P.H, and Murray, E.A. (2008). Amygdala and orbitofrontal cortex lesions differentially influence choices during object reversal learning. J. Neurosci. 28(33):8338–8343.

Saleem, K.S., Kondo, H., et al. (2008). Complementary circuits connecting the orbital and medial prefrontal networks with the temporal, insular, and opercular cortex in the macaque monkey. J. Comp. Neurol. 506(4):659–693.

Salvadore, G., Nugent, A.C., et al. (2011). Prefrontal cortical abnormalities in currently depressed versus currently remitted patients with major depressive disorder. NeuroImage 54(4):2643–2651.

Sartorius, A., Kiening, K.L., et al. (2010). Remission of major depression under deep brain stimulation of the lateral habenula in a therapy-refractory patient. [Case Reports Letter]. Biol. Psychiatry 67(2), e9–e11.

Savitz, J., Nugent, A.C., et al. (2010). Amygdala volume in depressed patients with bipolar disorder assessed using high resolution 3T MRI: the impact of medication. NeuroImage 49(4):2966–2976.

Schlaepfer, T.E., Cohen, M.X., et al. (2008). Deep brain stimulation to reward circuitry alleviates anhedonia in refractory major depression. Neuropsychopharmacology 33(2):368–377.

Schultz, W., Dayan, P., et al. (1997). A neural substrate of prediction and reward. Science 275(5306):1593–1599.

Shansky, R.M., Hamo, C., et al. (2009). Stress-induced dendritic remodeling in the prefrontal cortex is circuit specific. Cereb. Cortex 19:2479–2484.

Sharot, T., Riccardi, A.M, et al. (2007). Neural mechanisms mediating optimism bias. Nature 450(7166):102–105.

Sheline, Y.I., Gado, M.H., et al. (2003). Untreated depression and hippocampal volume loss. Am. J. Psychiatry 160(8):1516–1518.

Shulman, R.G., Rothman, D.L., et al. (2004). Energetic basis of brain activity: implications for neuroimaging. Trends. Neurosci. 27(8):489–495.

Starkstein, S.E., and Robinson, R.G. (1989). Affective disorders and cerebral vascular disease. Br. J. Psychiatry 154:170–182.

Stockmeier, C.A., Mahajan, G.J., et al. (2004). Cellular changes in the postmortem hippocampus in major depression. Biol. Psychiatry 56(9):640–650.

Sullivan, R.M, and Gratton, A. (1999). Lateralized effects of medial prefrontal cortex lesions on neuroendocrine and autonomic stress responses in rats. J. Neurosci. 19(7):2834–2840.

Suslow, T., Konrad, C., et al. (2010). Automatic mood-congruent amygdala responses to masked facial expressions in major depression. Biol. Psychiatry 67(2):155–160.

Taylor Tavares, J.V., Clark, L., et al. (2008). Neural basis of abnormal response to negative feedback in unmedicated mood disorders. NeuroImage 42(3):1118–1126.

Todtenkopf, M.S., Vincent, S.L., et al. (2005). A cross-study meta-analysis and three-dimensional comparison of cell counting in the anterior cingulate cortex of schizophrenic and bipolar brain. Schizophr. Res. 73(1):79–89.

Treadway, M.T., Grant, M.M., et al. (2009). Early adverse events, HPA activity and rostral anterior cingulate volume in MDD. PLoS. One. 4(3):e4887.

Treadway, M.T., and Zald, D.H. (2011). Reconsidering anhedonia in depression: lessons from translational neuroscience. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 35(3):537–555.

Tsao, D.Y., Schweers, N., et al. (2008). Patches of face-selective cortex in the macaque frontal lobe. Nat. Neurosci. 11(8):877–879.

Victor, T.A, Furey, M.L., et al. (2010). Relationship of emotional processing to masked faces in the amygdala to mood state and treatment in major depressive disorder. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 67(11):1128–1138.

Vidal-Gonzalez, I., Vidal-Gonzalez, B., et al. (2006). Microstimulation reveals opposing influences of prelimbic and infralimbic cortex on the expression of conditioned fear. Learn. Mem. 13(6:728–733.

Vythilingam, M., Heim, C., et al. (2002). Childhood trauma associated with smaller hippocampal volume in women with major depression. Am. J. Psychiatry 159(12):2072–2080.

Wacker, J., Dillon, D.G., et al. (2009). The role of the nucleus accumbens and rostral anterior cingulate cortex in anhedonia: integration of resting EEG, fMRI, and volumetric techniques. NeuroImage 46(1):327–337.

Wellman, C.L. (2001). Dendritic reorganization in pyramidal neurons in medial prefrontal cortex after chronic corticosterone administration. J. Neurobiol. 49(3):245–253.

Young, K.D., Erickson, K., et al. (2012). Functional anatomy of autobiographical memory recall deficits in depression. Psychol. Med. 42:345–357.