66 | LEWY BODY DEMENTIAS

STELLA KARANTZOULIS AND JAMES E. GALVIN

Lewy body dementia (LBD) is an umbrella term for two related diagnoses, Parkinson disease dementia (PDD), and dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB). Lewy body dementia is now recognized as the second most common cause of dementia after Alzheimer’s disease (AD). The Lewy Body Dementia Association estimates that there are between 1 and 2 million Americans with LBD. Lewy body dementia symptoms can closely resemble the more widely recognized dementia syndrome of AD but can be distinguished with identification of the visuospatial, executive, and attentional components of dementia (rather than the marked episodic memory impairment that characterizes AD), together with evidence of parkinsonism, visual hallucinations, and rapid eye movement sleep behavioral disorder (RBD). Cognitive fluctuations, although quite specific for LBD, can be difficult to elicit even at specialized centers given the lack of standardized questionnaires validated in large populations. Additional suggestive features incorporated in the consensus criteria for LBD that may facilitate diagnosis include depression, hallucinations in other modalities, syncope and frequent falls, transient and unexplained loss of consciousness, severe autonomic dysfunction, alterations in personality and behavior, relative preservation of medial temporal lobe structures on structural neuroimaging, reduced occipital activity on functional neuroimaging, and low uptake myocardial scintigraphy. Management of LBD currently rests on both pharmacological (cholinesterase inhibitors, N-methyl-d-aspartate antagonists, antiparkinsonism agents; atypical antipsychotics used with caution) and nonpharmacological (therapeutic environment, psychological and social support, physical activity, behavioral management strategies, caregivers’ education and support) therapy options for its many cognitive, neuropsychiatric, motor, autonomic, and sleep disturbances.

WHAT IS LEWY BODY DEMENTIA?

Over the past two decades, research has suggested that Lewy bodies (LBs) found in up to 40% of autopsied brains (Galvin et al., 2006) play a significant role in the spectrum of diseases that have come to be known as the Lewy body dementias (LBD). Lewy body dementias include Parkinson disease dementia and dementia with Lewy bodies. This chapter uses the term Lewy body dementia to describe the syndrome of LB disorders, and the terms Parkinson disease dementia and dementia with Lewy bodies when citing specific experimental and clinical data.

Parkinson disease (PD), one of the most common movement disorders of the elderly, affects one in 100 individuals greater than 60 years of age and 4% to 5% of older adults greater than 85 years of age (roughly 1.5 million Americans). Parkinson disease is characterized by the cardinal motor features of rigidity, bradykinesia, and tremor at rest. Historically, cognitive problems were not considered to be important features of PD. In his famous text, James Parkinson (1755–1824) stated, “by the absence of any injury to the senses and to the intellect that the morbid state does not extend to the encephalon.” It is now well recognized that cognitive impairment and dementia in the setting of PD are common and are two of the most debilitating symptoms associated with the disease. There is strong evidence that dementia not only has significant clinical consequences for PD patients in terms of increased disability, risk for psychosis, reduced quality of life, and increased mortality, but also results in a greater stress and burden of caring for patients with PDD and higher disease-related costs resulting from increasing chances of nursing home admission (Emre, 2003).

According to clinical diagnostic criteria (Table 66.1), PDD is a dementia syndrome that develops in the context of established PD (Emre et al., 2007). Like AD, PDD has an insidious onset with slow progression, and is defined as having impairment in more than one cognitive domain, representing a decline from prior levels. The deficits must be severe enough to affect daily social or occupational functioning or personal care and the deficits must be independent of the impairment resulting from motor or autonomic symptoms (Emre et al., 2007).

A wide variety of cognitive impairments have been reported in PDD, even early in the course of the disease. To date, the relationship between onset of initial deficits and subsequent decline to dementia has not been clearly established. Preliminary evidence suggests that an intermediate stage (PD-MCI) with predominant visuospatial and executive impairments may exist for one to three years (Johnson and Galvin, 2011). The neuropathology of PDD is controversial and it remains unknown whether or not dementia in PD occurs alone or only in the presence of other dementing disorders such as DLB and AD.

Dementia with Lewy bodies is now considered to be the second most common cause of dementia in elderly people. An international consortium on DLB resulted in revised criteria for the clinical and pathological diagnosis of DLB incorporating new information about the core clinical features and improved methods for their assessment (I. G. McKeith et al., 2005) (Table 66.2). Dementia with Lewy bodies, like all dementias, is characterized by a progressive reduction in cognitive functioning. The cognitive profile is one of mixed subcortical and cortical cognitive impairments that are often indistinguishable from PDD. Although the rate of dementia progression was once considered to be more rapid in DLB relative to AD, this has not been a consistent finding in the literature.

TABLE 66.1. Clinical diagnostic criteria for Parkinson disease dementia

|

Core features

(required for both probable or possible PDD)

|

Diagnosis of PD according to UK Brain Bank (Queen Square) criteria

Dementia with insidious onset and slow progression in the context of

of PD diagnosis, defined by:

• Impairment of more than one domain of cognition

• Impairment represents a decline from premorbid functioning

• Impairment in day-to-day functioning not caused by motor or autonomic dysfunction |

|

Associated features

(typical cognitive profile in at least two of the four domains + at least one behavioral symptom = probable PDD; atypical cognitive profile in one or more domains = possible PDD, and behavioral disturbance may or may not be present) |

Cognition

Impaired attention, may fluctuate within/across days

Impaired executive functions (e.g., planning, conceptualization, initiation, rule finding, set maintenance or shifting, mental speed)

Impaired visuospatial functions (e.g., visual-spatial orientation, perception, or construction)

Impaired memory (typically with benefit from cuing, better recognition than recall)

Preserved language (some difficulties with word-finding and complex sentence comprehension may be present)

Behavior

Apathy

Changes in mood and personality (including depression and anxiety)

Delusions, typically of paranoid type

Hallucinations, mainly visual, complex, and well formed

Excessive daytime sleepiness/somnolence

|

|

Features making the diagnosis of PDD uncertain

(none of these features can be present when diagnosing probable PDD; one or two features can be present when diagnosing possible PDD) |

Another abnormality capable of impairing cognition, but judged not to be the cause of the dementia (e.g., vascular disease on neuroimaging)

Time interval between onset of motor and cognitive symptoms is unknown

|

|

Supportive features

(commonly present but lacking diagnostic specificity) |

Cognitive and behavioral abnormality occurs solely in the context of other conditions, such as confusional state owing to systemic disease or intoxication, or major depressive disorder

Features consistent with probable vascular dementia per NINDS-AIREN criteria

|

TABLE 66.2. Revised clinical diagnostic criteria for dementia with Lewy bodies

|

Central feature

|

Progressive cognitive decline that interferes with social and occupational function

|

|

Core features

(any two core features = probable DLB; any one = possible DLB)

|

Fluctuating cognition

Recurrent visual hallucinations

Spontaneous features of parkinsonism

|

|

Suggestive features

(one or more + a core feature = probable DLB; one or more with no core feature = possible DLB)

|

REM sleep behavior disorder

Severe neuroleptic sensitivity

Decreased tracer uptake in striatum on SPECT dopamine

transporter imaging or on MIBG myocardial scintigraphy

|

|

Supportive features

(commonly present but lacking diagnostic specificity)

|

Repeated falls and syncope

Transient, unexplained loss of consciousness

Severe autonomic dysfunction

Hallucinations in other modalities

Systematized delusions

Depression

Relative preservation of mesial temporal lobe structures on CT/MRI

Reduced occipital activity on SPECT/PET imaging

Prominent slow waves on EEG with temporal lobe transient sharp waves

|

There is no one sign or symptom that definitively distinguishes PDD from DLB. Current clinical criteria for DLB distinguish PDD only by the temporal requirement that the dementia manifests more than 12 months after the onset of motor signs; if dementia precedes or is concurrent with parkinsonism, then DLB is diagnosed. In one study of 100 participants (10 nondemented controls, 40 patients with PD, 15 with DLB, and 35 with AD) enrolled in a longitudinal study of memory and aging, Galvin et al. (2006) found that postural instability is more common in PDD than DLB, whereas sexual disinhibition, alexia, and naming problems were more common in DLB relative to PDD. Galvin et al. also found that the presence of these features, whether at first evaluation or at any point in the course of PD, was highly predictive of PDD and the development of LBs at autopsy.

The core features of DLB include fluctuating cognition, recurrent well-formed visual hallucinations, and spontaneous parkinsonism. Extrapyramidal signs, including bradykinesia, facial masking, and rigidity are the most frequent signs of parkinsonism and can vary in severity. Resting tremor is not common. Parkinsonism is usually bilateral. There tends to be more axial rigidity and facial masking in DLB than in idiopathic PD.

Additional clinical features suggestive of DLB were also identified in the revised criteria. These include rapid eye movement sleep behavior disorder (RBD), severe neuroleptic sensitivity, and low dopamine transporter uptake in the basal ganglia demonstrated by single photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) or positron emission tomography (PET) imaging. Often present but not specific features of DLB include repeated falls and syncope, transient and unexplained loss of consciousness, autonomic dysfunction, hallucinations in other modalities, systematized delusions, depression, relative preservation of medial temporal lobe structures on structural neuroimaging, reduced occipital activity on functional neuroimaging, prominent slow wave activity on electroencephalogram (EEG), and low uptake iodine-123 metaiodobenzylguanidine (MIBG) myocardial scintigraphy.

According to the revised DLB consortium criteria, two core features (or one core feature and one suggestive feature) are sufficient for a diagnosis of probable DLB; one core feature or one or more suggestive feature is suggestive for a diagnosis of possible DLB (I. G. McKeith et al., 2005). As with AD, definitive diagnosis of DLB rests on brain autopsy following death. Although these features may support the clinical diagnosis of DLB, they lack diagnostic specificity and can be seen in other neurodegenerative disorders. These criteria permit 83% sensitivity and 95% specificity for the presence of neocortical LBs (I. G. McKeith, 2000b). These criteria are also more predictive of cases with pure or diffuse LB pathology than those with concomitant AD pathology, and fail to reliably differentiate between pure DLB (which is rare) and the more common mixed forms of DLB and AD. There are currently no definitive radiological or biological markers available to support a diagnosis of DLB.

EPIDEMIOLOGY OF LEWY BODY DEMENTIA

The precise number of people with LBD remains unclear. The point prevalence of dementia in PD is close to 30% and the incidence rate is increased at four to six times relative to controls. The cumulative percentage is very high, with at least 75% of PD patients who survive more than 10 years likely to develop dementia (Aarsland and Kurz, 2010). The mean time from disease onset of PD to dementia is approximately 10 years. However, there are considerable variations, and some patients develop dementia early in the disease course. Old age, more severe motor symptoms (in particular, gait and postural disturbances), mild cognitive impairment at baseline, and visual hallucinations are reliably identified as risk factors for early dementia.

Prevalence estimates of DLB range from 0% to 5% in the general population and from 0% to 30.5% of all dementia cases (Zaccai et al., 2005). Very few studies have looked at the incidence rates in DLB. Miech et al. (2002) found the incidence of DLB to be about 0.1% in the general population, and 3% for all new dementia cases.

NEUROPSYCHOLOGICAL FEATURES OF LEWY BODY DEMENTIA

Neuropsychological evaluation has provided clinicians and researchers with profiles of cognitive strengths and weaknesses that help to define LBD, as well as distinguish LBD from AD. It is important to keep in mind that neuropsychological tests often tap a number of different domains and the reasons that patients may perform poorly on any given test for any number of reasons. Unfortunately, the underlying cognitive processes of widely used neuropsychological measures have yet to be elucidated more precisely. Generally speaking, cognitive symptoms in LBD include a combination of cortical and subcortical impairment; this is contrasted with a classic cortical profile of impairment predominant in AD. See Table 66.3 for a summary of the neuropsychological deficits differentiating LBD from AD.

ATTENTION AND EXECUTIVE FUNCTION

Lewy body dementia is typified by impairments in attention and executive functions. Marked attentional disturbance in DLB may serve as the basis of fluctuating cognition that is characteristic of DLB (Walker et al., 2000). A range of experimental, screening, and clinical neuropsychological measures have been used to compare attention in LBD relative to AD. Few studies have shown group differences on digit span tasks (Hansen et al., 1990). Rather, more consistent group differences emerge on more complex attentional tasks, such as those requiring mental control, visual search and set shifting, and visual selective attention. On cancellation tasks, regardless of whether letters or shapes are used, Patients with LBD perform more poorly than AD patients. Additionally, the demonstration of greater attentional impairment and variability in reaction times in DLB relative to AD may be the function of the executive and visuospatial demands of the tasks (Bradshaw et al., 2004). Attentional deficits are important determinants of the inability to perform instrumental and physical activities of daily living, even after controlling for age, sex, motor function, and other cognitive profiles (Bronnick et al., 2006).

TABLE 66.3. Cognitive profiles comparing Lewy body dementia to Alzheimer’s disease

|

Episodic memory

|

|

|

|

Free recall

|

+++

|

++

|

|

Recognition

|

+++

|

—

|

|

Prompting

|

x

|

|

|

Intrusions

|

+++

|

+++

|

|

Semantic memory (naming)

|

++

|

+

|

|

Procedural memory

|

—

|

+

|

|

Working memory

|

++

|

+++

|

|

Insight

|

+++

|

+

|

|

Attention

|

++

|

+++

|

|

Executive functions

|

++ typical Alzheimer’s disease

+++ frontal variant

|

+++

|

|

Visuospatial skills

|

++ typical Alzheimer’s disease

+++ posterior variant

|

+++

|

Early frontal/executive dysfunction may be predictive of incident PDD (Woods and Troster, 2003) and is considered a core feature of PDD (Emre et al., 2007). Executive functions comprise a number of cognitive skills (planning, abstraction, conceptualization, mental flexibility, insight, judgment, self-monitoring, and regulation) and are central to adaptive, goal-directed behavior. The executive dysfunction seen in patients with LBD includes impaired judgment, organization, and planning (Kehagia et al., 2010). These patients are also more susceptible to distraction and have difficulty engaging in a task and shifting from one task to another. They tend to perform more poorly on Stroop, card sorting, and phonemic verbal fluency tasks than comparably demented patients with AD (Calderon et al., 2001). In general, executive impairments tend to be worse in LBD than AD (Collerton et al., 2003; Simard et al., 2000).

The neurochemical basis of executive dysfunction is likely to be multifactorial in nature and associated with dopaminergic, cholinergic, and noradrenergic deficits; although further study is required, increasing evidence from imaging and autopsy studies highlights the importance of cortical cholinergic loss (Emre, 2003).

VISUOSPATIAL/CONSTRUCTION

Visuospatial deficits are common in LBD and represent a very early and sensitive marker of PDD, especially when LB pathology and AD are mixed (Johnson and Galvin, 2011). Visuospatial changes are varied and can manifest across measures of facial recognition, spatial memory spatial planning, object-form perception, visual attention, visual orientation, and constructional praxis. Several studies have shown greater impairments in LBD than AD on visuospatial and constructional tasks (Collerton et al., 2003; Noe et al., 2004; Simard et al., 2003). Even brief-screening tests, such as pentagon copying from the Mini Mental State Examination (MMSE; Folstein et al., 2001) have been reported to be greater in LBD than AD (Ala et al., 2002; Cormack et al., 2004).

On complex figure copy tests, performance of patients with DLB is known to be affected partially by disrupted visual spatial perception and partially because of reduced frontally mediated skills such as organization, planning, and working memory. Furthermore, impairments on constructional tasks likely reflect more than just the motor demands of the tasks and the motor impairments of LBD, as these patients also show greater impairments than patients with AD on visual perceptual tasks without significant motor demands (Calderon et al., 2001) and even after controlling for the motor slowing characteristic in PDD (Johnson and Galvin, 2011). Subjects with DLB performed more poorly than patients with AD not only in size and form discrimination and visual counting, but also in recognizing overlapping figures. Studies have linked visual perceptual deficits in DLB to visual hallucinations (Mori et al., 2000); that is, those patients with visual hallucinations performed significantly worse on the overlapping figures test and performed worse in size and form discrimination than those subjects with DLB without visual hallucinations. Mosimann et al. (2004) also found that among patients with DLB and PDD, those with visual hallucinations performed significantly worse than those without hallucinations on tasks of angle, object-form, and space-motion discrimination. Because visual hallucinations are among the strongest predictors of DLB and PDD (Galvin 2006; Tiraboschi et al., 2006), the neuropsychological assessment of visual perceptual and constructional functions is important in suspected DLB and PDD and their differentiation from AD.

MEMORY

Generally speaking, patients with LBD perform better on episodic memory tasks than patients with AD. Memory may be spared early on in LBD and manifest as the disease progresses. Memory deficits are the presenting problem in 67% of patients with PDD, which is fewer than the number of patients with DLB (94%) and AD (100%) (Noe et al., 2004). The nature of the memory deficit in LBD differs from that noted in AD as it tends to be one of retrieval rather than encoding and/or consolidation and storage, with significant improvement noted with cuing in LBD relative to AD (Burn, 2006). The more severe amnestic deficits in AD relative to LBD likely reflects the greater burden of neurofibrillary tangles in the entorhinal cortex and surrounding medial temporal lobe regions in AD.

Some studies have suggested better recall on verbal memory tests (including the California Verbal Learning Test; Simard et al., 2000; Logical Memory subtest of the Wechsler Memory Scale-Revised; Calderon et al., 2001; memory subtest on the Dementia Rating Scale; Aarsland et al., 2003) among patients with DLB than those with AD, but this has not been consistently reported, possibly because of the difficulty in isolating pure forms of DLB from LBD cases caused by concurrent AD pathology. Dementia with Lewy bodies tends to co-occur with AD in 80% of cases, with only 20% having pure DLB. Patients with pure Lewy body pathology have better verbal memory skills than those with pure AD or mixed DLB/AD (Johnson et al., 2005). Patients with pure AD and mixed DLB/AD show equivalent degrees of impairment on verbal memory testing. In contrast, combined AD and Lewy body pathology appears to have an additive effect on visual memory skills.

Remote memory may also be affected by PDD (Huber et al., 1986; Leplow et al., 1997). Contrary to patients with AD who typically show a temporal gradient in their memories (with greater impairment noted for recent than remote information), the memory loss in PDD tends to be equally severe across past decades. Recognition of famous faces (a measure of remote memory) may be comparably impaired in DLB and AD (Gilbert et al., 2004).

LANGUAGE

Patients with DLB generally show milder naming deficits than patients with AD on measures of confrontation naming and there are group differences in terms of error profiles (Williams et al., 2007). The naming deficits may become progressively more severe with disease progression in DLB. Patients with AD are more likely to make more semantic errors on confrontation naming testing than patients with DLB, whereas those with DLB make significantly more visuoperceptual errors than patients with AD. The disproportionate visuospatial dysfunction described in DLB may contribute to reduced ability to perceive objects accurately, leading secondarily to errors in naming. Measures of generative fluency have also proved to be useful in differentiating AD from DLB. Patients with DLB are equally impaired in category and letter fluency, whereas patients with AD perform significantly better with letters than categories (Lambon et al., 2001). This may be related to underlying mechanisms: whereas patients with AD have degraded semantic networks or retrieval difficulties affecting semantic networks, attentional and executive impairments likely contribute to the difficulties with word search and retrieval in DLB subjects.

The language impairments in PDD also tend to be mild, with aphasia being a rare occurrence. Verbal fluency impairments are reliably observed in PDD and the deficits tend to be greater in PDD than AD (Cahn-Weiner et al., 2002). Mild deficits on measures of semantic fluency have also been reported (Monsch et al., 1992). Additional features of language impairment in PDD include decreased content of spontaneous speech, impaired naming, shorter phrase length, and dysarthria (Cummings et al., 1988).

BEHAVIORAL AND NEUROPSYCHIATRIC FEATURES

Neuropsychiatric features such as hallucinations and delusions are common in LBD, elicited primarily via informant ratings and less on formal diagnostic criteria. Perhaps most widely used of the informant ratings in LBD is the Neuropsychiatric Inventory (NPI; Cummings et al., 1988). Approximately 61% of PD patients exhibit neuropsychiatric disturbances. The most common features are depression (38%), hallucinations (27%), delusions (6%), anxiety (40%), sleep disturbances (60–90%), and sexual misdemeanor (5% to 10%). Galvin et al. (2006) found that visual hallucinations were the strongest single predictor of developing dementia in patients with PD and increased the risk of developing dementia 20-fold.

The phenomenology of visual hallucinations is similar in PDD and DLB. Visual hallucinations tend to be well formed, detailed, most commonly involving anonymous people (often described by the patient and dysmorphic or small), although they may also involve family members, animals, body parts, and machines. Hallucinations can occur in other modalities, including auditory, tactile, and olfactory. Auditory hallucinations are less common and generally not present in the absence of visual hallucinations. Hallucinations may be frightening and it is difficult to convince the patient that they are not real. This may pose safety problems, as the patient will feel that he or she will be attacked or have his or her home invaded.

Patients with DLB are more likely to show psychiatric symptoms and have more functional impairment at the time of initial evaluation than patients with AD. Visual hallucinations are typically present early in the course of the disease and do not diminish in later periods. In an analysis of autopsy-confirmed cases, hallucinations and delusions were more frequent with LB pathology (75%) than AD (21%) at the time of the initial clinical evaluation (Weiner et al., 2003). This was also true for those cases with mixed DLB and AD (53%) pathology relative to AD alone. The occurrence of visual hallucinations in the first four years after dementia onset has a positive and negative predictive value for DLB of 81% and 79%, respectively (Ferman et al., 2006).

There is a strong association between visual hallucinations and cholinergic depletion in the temporal cortex and the basal forebrain (Harding et al., 2002). Visual hallucinations may predict a good response to cholinesterase inhibitors (I. McKeith et al., 2004). The hallucinations of DLB do not seem to correlate with the dose of levodopa (L-dopa) or the occurrence of motor fluctuations seen with dopaminergic therapy (Sanchez-Ramos et al., 1996); however, hallucinations may be elicited or worsened with dopaminergic medications. Other suggested mechanisms for visual hallucinations include dysregulation of rapid eye movement (REM) sleep with the intrusion of dreams into wakefulness (Boeve et al., 2004).

Delusions also occur in 56% of patients with DLB at first presentation and 65% at some point in their illness. Delusions tend to be more common in DLB than in PDD or AD. Paranoid, Capgras (believing individuals are replaced by identical imposters), and “phantom boarder” (unseen individuals residing in one’s home) are among the most common delusions. Misidentification syndromes appear to be particularly prevalent in DLB, occurring in up to 40% of patients, compared with 10% in AD (Ballard et al., 1999). It is not yet clear whether misidentification delusions are also characteristic of PDD.

Depression is common in both PDD and DLB and there is equivocal evidence as to whether base rates of depressed mood and major depression differ between these disorders and AD (Ferman et al., 2006). A history of depression has been reported in 58% of persons with PDD, 50% of patients with DLB, and in 14% of AD cases coming to autopsy (Klatka et al., 1996). Risk factors for depression include early onset PD, presence of hallucinations or delusions, and an akinetic rigid presentation (vs a tremor predominant variant). The incidence of depression appears to be unrelated to the presence or absence of dementia or the severity of motor impairment (I. G. McKeith, 2000a). Anxiety and apathy co-occur, with depression in 40% and 15% of patients with PD, respectively. Apathy is also common in DLB, particularly with more severe dementia.

PERSONALITY CHANGES

Personality changes in DLB tend to occur with auditory and visual hallucinations and include diminished emotional responsiveness, resignation of hobbies, increased apathy, and purposeless hyperactivity (Galvin et al., 2007). Using principal components analysis, Galvin and his colleagues were able to identify three general personality traits in DLB. The first were irritable traits (accounting for almost 33% of the variance) and included increased rigidity, egocentricity, loss of concern, coarsening of affect, and impaired emotional control. The second were a passive group of traits (this explained just more than 12% of the variance) and included diminished emotional responsiveness, relinquished hobbies, growing apathy, and purposeless activity. The third reflected disinhibition (this explained an additional 10.4% of the variance) and included inappropriate hilarity and sexual misdemeanor. Using this three-factor structure, patients with DLB were more likely to manifest personality traits associated with passive personality traits than patients with AD. Using receiver operating characteristic curves, these authors also showed that the passive personality traits discriminated between AD and DLB, whereas both the irritable set of traits and those reflecting disinhibition were uncommon in both groups.

COGNITIVE FLUCTUATIONS

Fluctuations in cognition are one of the hallmarks of DLB, seen in 15% to 80% of patients with DLB (Ballard et al., 2002). Cognitive fluctuations are also common in PDD and may be as frequent as in DLB (Ballard et al., 2002). These often involve waxing and waning of cognition, attention, concentration, functional abilities, or arousal in the absence of any clear precipitant. They are often described as episodes of behavioral confusion, inattention, hypersomnolence, and incoherent speech alternating with episodes of lucidity and capable task performance. Patients may be described as staring into space or being dazed and the episodes can last minutes to days, varying from alertness to stupor. An extreme form of fluctuations may occur when patients are found mute and unresponsive for a few minutes.

Given the large variability in the description and quantifications of fluctuations in patients with LBD, a number of scales have been developed, including the Clinical Assessment of Fluctuation and the One Day Fluctuation Assessment Scale, and the Mayo Fluctuations Questionnaires (Ferman et al., 2006). The Mayo scale describes four features of fluctuations that can reliably distinguish DLB from AD or normal aging. Three or four features of this composite occurred in 63% of patients who had DLB compared with 12% of those who had AD and 0.5% of normally functioning elderly people. The presence of three or four of these features yielded a positive predictive value of 83% for the clinical diagnosis of DLB against an alternate diagnosis of AD.

AUTONOMIC DYSFUNCTION

Autonomic dysfunction is a common clinical sign in LBD. Autonomic features tend to occur later in the disease course of DLB, although there have been some cases with early and prominent involvement. Symptomatic orthostasis is probably the most serious manifestation of autonomic dysfunction, observed in approximately 15% of patients with DLB. Other features include decreased sweating, excessive salivation (sialorrhea), seborrhea, heat intolerance, urinary dysfunction, constipation or diarrhea, and erectile dysfunction or impotence. In fact, constipation may precede any cognitive or motor symptoms by more than a decade. Patients with DLB also have a higher frequency of carotid hypersensitivity than elderly patients or those with AD. There is also evidence of cardiac denervation by MIBG scintigraphic scanning, a finding not seen in AD.

Autonomic dysfunction tends to occur in the late stages of PD and is related to disease severity and duration. Approximately one-third of patients have clinical features of autonomic dysfunction, although estimation of the prevalence of autonomic dysfunction is compounded by factors such as the use of antiparkinsonian medications. Most common in PD are decreased gastrointestinal ability and bladder dysfunction. Also common is constipation and there is a risk of more serious complications including intestinal pseudoobstruction and toxic megacolon. Other common features include bladder dysfunction with urgency, frequency and incontinence, and sexual dysfunction (decreased libido and erectile dysfunction). Symptomatic orthostasis is more common in association with cognitive impairment in PDD.

SLEEP DISORDERS

Many patients with LBD have parasomnias. Most common is REM sleep behavioral disorder (RBD), which tends to begin concurrently or after the onset of parkinsonism or dementia (Boeve et al., 2007). Rapid eye movement sleep behavioral disorder is marked by lack of normal muscle atonia that prevents movements (other than eye movements) during REM sleep in the presence of excessive activity while dreaming; this can result in vocalizations and sometimes wildly violent behavior. Rapid eye movement sleep behavioral disorder may be idiopathic or may be associated with LBD and other synucleinopathies. Patients may be unaware of the disorder and the history is therefore often dependent on the patient’s bed partner. Rapid eye movement sleep behavioral disorder is more commonly found in men in their fifties and may precede the clinical signs associated with LBD by many years. Parkinson disease patients with RBD show impairments of some logical abilities as compared with subjects without RBD (Sinforiani et al., 2006). There are, however, no longitudinal studies confirming RBD as a risk factor for PDD. On the other hand, excessive daytime sleepiness has been reported to be a risk factor for PDD (Olson et al., 2000).

NEUROLOEPTIC SENSITIVITY

Patients with DLB are notorious for their neuroleptic sensitivity. Reactions are observed in 30% to 50% of patients with DLB and are characterized by sudden onset of impaired sensitivity, acute confusion, psychotic episodes, and exacerbation of parkinsonism symptoms such as rigidity and immobility (I. McKeith et al., 1992). In some cases, these reactions can lead to death within several days. One survey (Aarsland et al., 2005) revealed a 58% frequency of neuroleptic sensitivity to olanzapine, with lower rates with clozapine (11%) and thioridazine (6%). These data support the notion of unacceptable safety profiles for some neuroleptics in LBD. Patients with DLB also tend to be activated by sedatives and awakened by sleep medications (Rogan and Lippa, 2002). Severe neuroleptic sensitivity has been reported in up to 40% of patients with PDD exposed to neuroleptic drugs (Aarsland et al., 2005).

NEUROPATHOLOGY

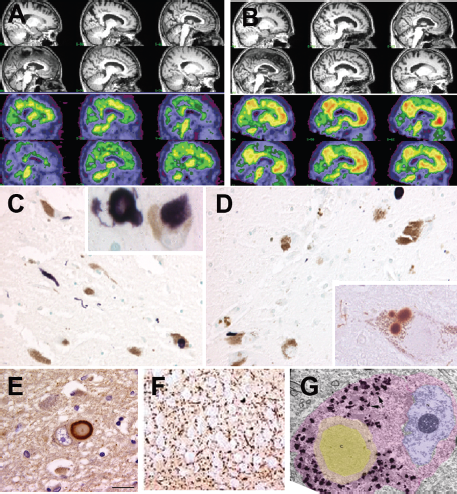

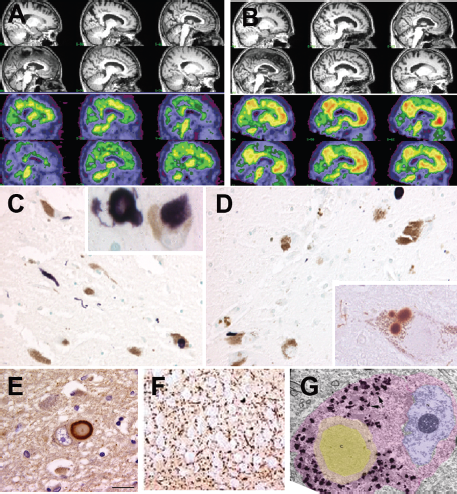

The main identifying pathological features of LBD are cortical and subcortical LBs and Lewy neurites (LNs). Lewy bodies are spherical intracytoplasmic protein deposits around the nucleus and throughout the dendrite of subcortical and cortical neurons. They consist of filamentous protein granules composed of α-synuclein and ubiquitin, and are surrounded by a halo of neurofilaments. Cortical LB sites include the cingulate gyrus, entorhinal cortex, insular cortex, frontal cortex, and amygdala (Fig. 66.1).

The different forms of LBD can have variations as to the extent and spread of α-synuclein pathology and variable amount of AD pathology (see Fig. 66.1). For both PDD and DLB, staging/classification systems based on semiquantitative assessment of the distribution and progression pattern of α-synuclein pathology are used that are considered to be linked to clinical symptoms.

In PD, a six-stage system is suggested to indicate a predictable sequence of lesions with ascending progression from medullary and olfactory nuclei to the cortex (Braak et al., 2003) (see Table 66.3). Braak stages 1 and 2, with LB pathology involving medulla oblongata and pontine tegmentum, are considered asymptomatic or presymptomatic and may explain the early nonmotor symptoms (autonomic and olfactory). Braak stages 3 and 4, involving extension of LB pathology to midbrain and basal prosencephalon and mesocortex, has been correlated to clinical symptomatic stages. The terminal Braak stages 5 and 6, characterized by widespread neocortical LB degeneration, are correlated with significant cognitive decline associated with severe parkinsonism (Hurtig et al., 2000).

Dementia with Lewy bodies, according to consensus pathological guidelines, by semiquantitative scoring of α-synuclein pathology (LB density and distribution) in specific brain regions, is distinguished into three phenotypes: brainstem, limbic, and diffuse cortical. Concomitant AD-type pathology is also considered. Generally speaking, the more neocortical LBs and the lower the Braak stage, the more likely the patient will meet the criteria for DLB, whereas higher Braak stages and non-neocortical LBs are associated with a lower likelihood of obtaining DLB diagnosis. In one review of 88 autopsy-confirmed cases, identification of clinical DLB was inversely proportional to Braak staging of neurofibrillary pathology. It should be noted that clinician sensitivity was still poor regardless of classification scheme (Weisman and McKeith, 2007). Neuronal loss in the substantia nigra is greater in PDD than in DLB, whereas beta-amyloid patterns are more consistent in DLB. α-synuclein pathology is also greater in the striatum in DLB than PDD (Duda et al., 2002).

In PDD, Galvin et al. (2006) identified three neuropathological profiles when comparing autopsy reports of 103 cases followed longitudinally. Roughly one-third of PDD was found to be caused by neocortical LBs without evidence of AD pathology. Another one-third had abundant senile plaques and neurofibrillary tangles meeting criteria for both PD and AD. The final group had only brainstem pathology comprising LBs. These data are in line with the staging paradigm proposed by Braak and colleagues, suggesting that PD pathology begins in the lower brainstem and spreads in a caudal-rostral fashion (Braak et al., 2003). Importantly, recent studies have revealed exceptions to the general order of progression suggested by Braak and colleagues (e.g., Jellinger, 2008; Parkkinen et al., 2008).

GENETICS

In the past decade, tremendous advances have been made in understanding the genetic factors influencing the pathogenesis of LBD. Compelling evidence for a genetic basis for both PD and DLB followed the discovery of mutations in the α-synuclein gene (PARK1/4) in patients with autosomal dominant familial PD, and subsequently, mutations were identified in patients with both sporadic and familial DLB. From a susceptibility marker on chromosome 4q21-23 that segregated with the PD phenotype in Italian and Greek kindreds, A53T (Polymeropoulos et al., 1997) and A30P (Kruger et al., 1998) were the first two missense mutations in α-synuclein associated with familial Parkinson disease.

Figure 66.1 Imaging and pathology in lewy body dementia. (A) Sagittal sections of MRI and amyloid imaging in a case of PDD. There is mild cortical atrophy largely sparing the hippocampus. Amyloid imaging reveal minimal to no uptake of the PIB. (B) Sagittal section of MRI and amyloid imaging in a case of mixed LBD and AD. There is slightly more prominent atrophy of the hippocampus with significant uptake of PIB. (C) Photomicrograph of substantia nigra in DLB patient stained with α-synuclein. Note dystrophic neurites. Insert shows higher power magnification of two Lewy bodies in the nigral neurons. (D) Photomicrograph of substantia nigra in PDD patient stained with α-synuclein. Insert shows higher power magnification of a nigral neuron with multiple Lewy bodies. (E) Photomicrograph of Lewy body in the cingulate cortex of a LBD patient stained with α-synuclein. (F) Photomicrograph of dystrophic neurites in the CA 2–3 region of the hippocampus in a LBD patient. (G), Electron micrograph of a Lewy body. Note the dense core (gray) surrounded by a paler halo.

α-synuclein is a member of a larger family of synuclein proteins, which also includes β- and γ-synuclein. Like α-synuclein, β-synuclein has recently been implicated in PD and DLB pathogenesis, but its precise role in disease is still emerging. β-synuclein is highly localized to presynaptic sites in neocortex, hippocampus, and thalamus (Iwai et al., 1995) and it may act as a biological negative regulator of α-synuclein. Two novel β-synuclein point mutations, P123H and V70M, were found in highly conserved regions of the β-synuclein gene in respective familial (P123H) and sporadic (V70M) DLB index cases (Ohtake et al., 2004), where abundant LB pathology and α-synuclein aggregation was present without β-synuclein aggregation.

Unlike the other synuclein family members, γ-synuclein or persyn is largely expressed in the cell bodies and axons of primary sensory neurons, sympathetic neurons, and motor neurons as well as in brain (Buchman et al., 1998). γ-synuclein is the most recent synuclein member to be linked to LBD neuropathology and the least well understood. Single-nucleotide polymorphisms in all three synucleins have been associated with sporadic DLB, most prominently γ-synuclein (Nishioka et al., 2010).

STRUCTURAL MAGNETIC RESONANCE IMAGING

A diffuse pattern of global gray matter atrophy including temporal, parietal, middle, and inferior frontal gyri and occipital lobe has been reported in DLB, similar to AD (Beyer et al., 2007; Burton et al., 2004). Most volumetric studies have not found a significant occipital structural change in DLB (Burton et al., 2002, 2004); this contrasts with the reported occipital hypometabolism/hypoperfusion noted with PET/SPECT studies, respectively. Longitudinal rates of whole-brain atrophy in PDD and DLB are probably intermediate between healthy aging and AD (O’Brien et al., 2001; Whitwell et al., 2007).

A robust MR finding in DLB and PDD is that of relative preservation of the medial temporal lobe when compared with AD (Barber et al., 2001; Burton et al., 2002; Whitwell et al., 2007); this holds promise as a diagnostic marker in differentiating AD from DLB (see Fig. 66.1).

Subcortical changes in terms of striatal atrophy have also been described in DLB. Putamen atrophy has been reported in DLB relative to AD (Cousins et al., 2003), but no significant differences were detected in caudate nucleus (Almeida et al., 2003; Cousins et al., 2003).

FUNCTIONAL IMAGING

OCCIPITAL HYPOPERFUSION AND HYPOMETABOLISM

Single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) studies in PD (Matsui et al., 2005) and DLB (Donnemiller et al., 1997) indicate reduced occipital perfusion relative to other cortical areas. It has been suggested that reduced flow in the medial occipital lobe, including the cuneus and the lingual gyrus, can discriminate LBD from AD, with a sensitivity and specificity of 85% (Shimizu et al., 2005). The possibility that parietal lobe perfusion is more severely reduced rather than occipital lobe hypoperfusion in DLB has also been raised (Ishii et al., 1998), which may be caused by the dopaminergic and/or cholinergic impairment in this region.

The use of PET scanning with markers such as [18F] fluorodeoxyglucose ([18F] FDG) shows metabolic reductions have been observed in the visual association cortex in DLB not evident in AD (Higuchi et al., 2000). A multicenter study examining ([18F] FDG PET measures in the differential diagnosis of dementia, including AD, frontotemporal dementia (FTD), and DLB reported hypometabolism in the parietotemporal and posterior cingulate cortices in AD, more prominent hypoperfusion in the occipital lobe in DLB, and more prominent hypometabolism in the frontal/temporal cortices in FTD. These cortical abnormalities discriminated DLB from AD with a sensitivity of 71% and a specificity of 95%. In another study, occipital hypometabolism and relative preservation of the posterior cingulate gyrus distinguished DLB from patients with AD with a sensitivity of 77% and a specificity of 80% (Lim et al., 2009). Greater metabolic decrease in the anterior cingulate has also been shown in DLB than PDD (Yong et al., 2007).

STRIATAL DOPAMINE LOSS

Nigrostriatal degeneration, with profound reductions in the striatal dopamine transporter, has consistently been found in patients with DLB at autopsy. Nigrostriatal integrity is assessed in vivo with specific ligands, such as 123I-FP-CIT in SPECT imaging, which binds to dopamine transporter and [11C] dihydrotetrabenazine in PET imaging, which binds to the vesicular monamine transporter T2 series.

Reduced striatal dopamine transporter uptake in DLB but not in AD has been shown in SPECT studies, which may aid in differential diagnosis (O’Brien et al., 2004; Walker et al., 2002). A large multicenter study examining 123I-FP-CIT SPECT in DLB reported a sensitivity of 78% for detecting probable DLB and a specificity of 90% for excluding non-LBD, primarily AD (McKeith et al., 2007). In another study, 123I-FP-CIT imaging was in line with postmortem diagnoses in 19 of 20 cases, and was more precise than clinical diagnosis (Walker et al., 2007). However, 123I-FP-CIT is limited in that it does not discriminate DLB from other atypical parkinsonian syndromes. Nevertheless, head-to-head analyses comparing 123I-FP-CIT imaging to other imaging modalities including ([18F] FDG-PET have shown superior diagnostic accuracy with 123I-FP-CIT imaging (Colloby et al., 2008; Lim et al., 2009).

Positron emission tomography studies have also been used to evaluate nigrostriatal dopaminergic degeneration in DLB. Reduction of striatal dopamine uptake was observed in patients with DLB using [18F] fluorodopa, with a sensitivity of 86% and a specificity of 100%, although this study was limited by a small sample size (Hu et al., 2000). These findings were confirmed in a later study using [11 C] dihydrotetrabenazine, which also showed significantly reduced uptake in caudate nucleus and anterior and posterior putamen in DLB and PD compared with patients with AD and normal controls (Koeppe et al., 2008).

The latest revision of the International Consensus Criteria for DLB indicates that low dopamine transporter uptake in basal ganglia demonstrated by SPECT or PET imaging is a feature that in addition to a single core feature can support a diagnosis of probable DLB (I.G. McKeith et al., 2005). The National Institute for Health and Clinical Experience also recommends that 123I-FP-CIT SPECT imaging may be particularly helpful when the diagnosis of DLB is unclear. Likewise, the European Federation of Neurological Societies (EFNS) guidelines also recommend the use of dopaminergic SPECT to differentiate between DLB and AD (Hort et al., 2010), the only imaging category to reach level A category of evidence.

CHOLINERGIC MARKERS

Brain cholinergic function can be estimated in vivo by measuring acetylcholinesterase (ACh) activity by PET using radiolabeled ACh analogues (Namba et al., 2002). Acetylcholinesterase is an enzyme that degrades ACh into the inactive metabolites choline and acetate. Several studies have demonstrated that cortical ACh activity is more severely and extensively reduced in the cerebral cortex, especially in the medial occipital cortex in DLB and PDD in comparison with AD, in which deficits were more prominent in the temporal cortex (Bohnen et al., 2003; Shimada et al., 2009).

Nicotinic and muscarinic receptors are subclasses of ACh receptors, implicated in memory and cognitive processes. Imaging of muscarinic receptors (Colloby et al., 2006) and nicotinic receptors (O’Brien et al., 2008) with SPECT has revealed decreases in the frontal and temporal lobes of PDD and DLB, and relative increases in the uptake of both ligands in the occipital lobe, with the nicotinic ligand uptake being higher in DLB subjects with recent hallucinations (O’Brien et al., 2008). However, these changes are likely not specific to DLB because an increase in nicotinic binding in the occipital lobe has also been observed in vascular dementia (Colloby et al., 2011) and decreases have been noted in the frontal and temporal lobes in AD (O’Brien et al., 2007). The data are not yet compelling enough to suggest that PET and SPECT imaging looking at cholinergic activity could be used diagnostically in LBD.

METAIODOBENZYLGUANIDINE MYOCARDIAL SCINTIGRAPHY

[123I] Metaiodobenzylguanidine myocardial scintigraphy is a noninvasive technique that was developed to evaluate the local myocardial sympathetic nerve damage, primarily in heart disease, and has only recently been used in LBD. The rationale for its use is that impairment of the peripheral sympathetic nervous system can occur even in the earliest clinical stage of PD (Spiegel et al., 2005). In addition, cardiovascular autonomic dysfunction is common in DLB (Allan et al., 2007). The early disturbance in the sympathetic nervous system can be detected by reduced MIBG uptake on myocardial scintigraphy independent of the duration of the disease.

A number of studies have demonstrated reduced MIBG uptake (heart to mediastinum ratio) in DLB relative to patients with AD and normal controls, with impressive accuracy for discriminating DLB from AD. Most studies performed measurement of both early (15- to 30-minute) and late (three- to four-hour) MIBG uptake, with the late image ratio typically resulting in better diagnostic accuracy. Several studies have found no correlation of MIBG scintigraphy with disease severity or duration of DLB or AD (Oide et al., 2003; Suzuki et al., 2006; Yoshita et al., 2001). Studies comparing MIBG scintigraphy and occipital hypoperfusion on SPECT have reported MIBG scintigraphy to be more sensitive in detecting DLB (Hanyu et al., 2006; Tateno et al., 2008). Also, MIBG scintigraphy has been reported to be more sensitive than cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) p-tau in terms of differentiating between DLB and AD Wada-(Wada-Isoe et al., 2007). No comparison with FP-CIT imaging has so far been carried out. However, one potential advantage of MIBG over FP-CIT is that myocardial MIBG can distinguish PD and DLB from atypical parkinsonian syndromes such as multiple system atrophy, corticobasal degeneration, and progressive supranuclear palsy (Spiegel, 2010), because in PD and DLB, the myocardial sympathetic damage is predominantly postganglionic, whereas in other parkinsonian syndromes, the preganglionic structures are mainly affected, resulting in normal MIBG uptake.

POSITRON EMISSION TOMOGRAPHY AMYLOID IMAGING

Over the past five years or so, amyloid imaging has emerged as important neuroimaging tool in studies of brain aging and dementia. Pittsburgh compound B (PIB) is currently the most widely studied amyloid imaging agent. In vitro, PIB has been shown to bind specifically to extracellular and vascular fibrillar Aβ deposits in postmortem AD brains (Ikonomovic et al., 2008; Lockhart et al., 2007). At PET tracer concentrations, PIB does not significantly bind to other protein aggregates such as neurofibrillary tangles or Lewy bodies, and hence may be useful for diagnostically discriminating between AD and non–Aβ dementias (Rabinovici et al., 2007; Rowe et al., 2008).

As discussed, LBD is characterized at autopsy by the presence of subcortical and cortical LBs with a substantial burden of amyloid pathology also possible (Ballard et al., 2006). A limited number of PET studies have examined the amyloid burden in DLB and PDD in vivo (Edison et al., 2008; Gomperts et al., 2008). Edison et al. (2008) showed that in DLB, mean brain PIB uptake was significantly higher than that in controls, whereas uptake in PDD was comparable to controls and PD patients without dementia (Fig. 66.1). None of the patients with PD showed any evidence of increased cortical amyloid deposition. Gomperts et al. (2008) revealed that cortical amyloid burden as measured by PIB was higher in DLB than in PDD, but similar to that in AD. It may be that global cortical amyloid burden is high in DLB but lower and less frequent in PDD. Pittsburgh compound B imaging may prove to be useful to distinguish AD from PDD, but not AD from DLB.

CAREGIVER ISSUES

Lewy body dementia not only affects the individual diagnosed with the illness, but also has a profound impact on his or her caregivers, families, and friends. Those close to the patient have to learn to assist with the behavioral and emotional symptoms that accompany LBD, which are more pronounced and manifest earlier than in AD, as well as with the motor impairment, falls, and overall higher levels of disability than with other types of dementia (Ricci et al., 2009). Lewy body dementia caregivers also have to struggle through the often years-long challenge of obtaining an accurate diagnosis and adequate medical care for their relative.

The Lewy Body Dementia Association recently conducted an Internet survey of caregiver burden in LBD. Respondents were 611 people who stated that they were actively involved in the care of their relative with LBD. Results of this survey showed that in contrast to AD, many more LBD caregivers are women and are more often the spouse of the affected person. This difference likely reflects that fact that LBD is slightly more common in men than women, whereas AD is more common in women. Caregivers also reported many barriers in obtaining a diagnosis for their loved ones, with most having seen multiple physicians over more than a year before their relative was diagnosed with LBD and with more than three-fourths of persons with LBD given a different diagnosis at first.

Using these data from the Lewy Body Dementia Association, Leggett et al. (2011) were able to examine levels of stress and burden among caregivers of patients with LBD. Subjective burden was assessed with a 12-item short version of the Zarit Burden Interview. The results showed that caregivers of patients with LBD experience significant perceptions of burden that is heightened by behavioral and emotional problems present early on in LBD (depression, irritability, hallucinations, delusions, sleep disturbances, nightmares, and unusual sleep movements), impaired ADLs, sense of isolation, and challenges with the diagnostic experience. Significantly, the level of subjective burden among this group of caregivers was noted to be higher than what is typically endorsed among caregivers of AD or mixed diagnostic groups. These data suggest that future interventions targeting each of these challenges are needed for caregivers of patients with LBD.

THERAPEUTIC APPROACHES

There are no approved therapies specifically for LBD; however, there is ample evidence in the literature regarding the use of medications approved for other disorders for the treatment of the various symptoms of LBD.

COGNITIVE SYMPTOMS

Acetylcholinesterase inhibitors (AChEIs) may be especially useful in the treatment of LBD. These medications, including donepezil (Aricept), rivastigmine (Exelon), and galantamine (Razadyne ER or Reminyl) block the breakdown of acetylcholine within the synapse, thereby prolonging its effect on postsynaptic receptors. AChEIs are generally well tolerated at their standard dosing. Primary side effects are gastrointestinal (e.g., nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, anorexia, weight loss); other side effects can include insomnia, vivid dreams, leg cramps, and urinary frequency.

It has been suggested that treatment with AChEIs may be more effective in DLB than AD because of early and prominent central nervous system cholinergic dysfunction in this group (Touchon et al., 2006). In one study, patients with DLB showed greater treatment improvement in cognition relative to AD patients, although the difference between the two groups was not significant (Samuel et al., 2000). Only a few clinical trials for the use of AChEIs in LBD have been conducted and most guidelines are based on case reports and extension of therapeutic trials in AD. Three independent clinical studies of AChEI treatment using donepezil, galantamine, and rivastigmine in patients with LBD suggest that AChEIs improve cognitive and neuropsychiatric measures, with no significant increase in EPS with AChEI use. Rivastigmine was the first AChEIs to be given European and American marketing approval for patients with mild to moderate PDD. Currently, there is no compelling evidence that any one AChEI is better than the other.

The NMDA antagonist memantine, another treatment modality approved for use in AD, has not yet been tested in large, randomized, controlled studies in PDD. Results have been variable in a few case reports or case series in patient with DLB, with both worsening (Ridha et al., 2005) and improvement (Sabbagh et al., 2005) noted. Good tolerability and possible benefits have been reported in a small case series of patients with PDD.

MOTOR SYMPTOMS

There are no controlled clinical trials that have yet evaluated the treatment of motor features in DLB. There are reports of small series of patients with DLB whose motor impairments were successfully treated with l-dopa (Molloy et al., 2005). Levodopa is more effective in treating motor impairments in idiopathic PD than DLB. Dopamine agonists are associated with more side effects, especially drug-induced psychosis, even at low doses. Given this risk and because the motor impairments may be mild, the recommendation is to treat the movement disorder only if the motor symptoms interfere with function. Antiparkinsonism medicines should be initiated at the lowest possible dose and increased with caution. There have been reports of increased adverse events with the combined use of l-dopa and cholinesterase inhibitors in PD (Okereke et al., 2004).

Other PD medications such as amantadine, catechol-O-methyltransferase inhibitors, monoamine oxidase inhibitors, and anticholinergics tend to exacerbate cognitive impairment and should ideally be avoided. Furthermore, the cognitive impairment in DLB makes them poor candidates for DBS. Cholinesterase inhibitors can potentially worsen parkinsonism. In a study of rivastigmine in PD, approximately 10% of patients treated with rivastigmine had worsening of tremor (I. McKeith et al., 2000). However, their overall motor function was not significantly different between the treatment and placebo groups (I. McKeith et al., 2000).

BEHAVIORAL SYMPTOMS

As discussed, behavioral symptoms frequently accompany LBD. Clinical experience suggests that nonpharmacological treatment approaches should be considered first, including evaluating for physical ailments that may be provoking behavioral disturbances (e.g., fecal impaction, pain, or decubitus ulcers). Avoidance or reduction of doses of other medications that can potentially cause agitation should also be attempted. Both anxiety and depression are common occurrences in LBD. Generally speaking, when medications are needed to modify behaviors, they should be used for the shortest duration possible. Benzodiazepines are better avoided given their risk of sedation and paradoxical agitation.

There have been no randomized, controlled studies of antidepressants in patients with PDD. In one systematic review, amitriptyline was found to be the only compound with evidence of efficacy in PD depression; however, tricyclic antidepressants such as amitriptyline should be avoided in patients with PDD because of their anticholinergic effects.

ANTIPSYCHOTICS

Visual hallucinations have been considered predictors of a good response to AChEIs (I. McKeith et al., 2004). Classical neuroleptics (e.g., haloperidol) are best avoided in DLB because they may worsen motor function and even potentially result in life-threatening neuroleptic sensitivity. Experience with atypical antipsychotics in LBD has been mixed. Risperidone and olanzapine have been shown to control psychosis and agitation in AD in randomized trials. Although low doses of risperidone (0.5 mg) and olanzapine (2.5 mg) are usually well tolerated and do not usually result in motor deterioration (Katz et al., 1999), motor deterioration may still be seen in advanced LBD (Walker et al., 1999).

Quetiapine and clozapine are preferred treatment options when pharmacological intervention is warranted. Randomized, placebo-controlled studies showing significant improvement of psychosis without worsening of motor symptoms has only been shown with clozapine (Friedman and Fernandez, 2002). However, given the potentially fatal adverse event of agranulocytosis and need for blood monitoring, it is not a first-line treatment. Apiprazole has not been studied in LBD but it has been shown to be effective in PD and AD and may be considered in LBD if needed. Quetiapine has become a popular treatment of psychosis in LBD given the low incidence of motor deterioration and its ability to control visual hallucinations at low doses. Efficacy and tolerability have been documented in both PD and DLB (Friedman and Fernandez, 2002). It is worth noting that hallucinations that are nonthreatening to the patient and do not disturb function may not require pharmacological intervention. Rapid eye movement sleep behavior disorder generally responds to low doses of clonazepam before sleep.

ACETYLCHOLINESTERASE INHIBITORS FOR BEHAVIORAL SYMPTOMS

A metaanalysis of six large trials in AD showed a small but significant benefit for AChEIs in treating neuropsychiatric symptoms (Trinh et al., 2003). There also appears to be a differential effect of AChEIs on different psychiatric symptoms, with psychosis, agitation, wandering, and anxiety being the most consistently responsive. In a large multicenter trial, rivastigmine resulted in a 30% improvement from baseline in psychiatric symptoms (McKeith et al., 2000). In a case-control study of rivastigmine, treatment was associated with a reduction in NPI scores, hallucinations, and sleep disorders compared with AD. There were lower rates of apathy, anxiety, delusions, and hallucinations in the treatment group compared with controls. It is not clear whether this effect on behavior is owing to drug effect or more severe behavioral pathology in LBD.

AUTONOMIC DYSFUNCTION

Management of orthostatic hypotension includes relatively simple measures such as leg elevation, elastic stockings, increasing salt and fluid intake, and if not medically contraindicated, avoiding medications that can exacerbate orthostasis. Medications such as midodrine or fludrocortisone can be used in the event that such simple measures fail. Midodrine is a vasoconstrictor and side effects include urine retention and supine hypertension. Fludrocortisone has mineralocorticoid activity and causes fluid retention.

Medications with anticholinergic activity, including oxybutynin, tolterodine tartrate, bethanechol chloride, and propantheline can be used to treat urinary urgency, frequency, and urge incontinence. Because they can potentially exacerbate cognitive problems, these medications should be used cautiously. Because LBD is more common in men, the risk of producing urinary retention in the setting of prostatic hypertrophy should be considered.

Constipation can usually be treated by exercise and dietary modifications. Laxatives, stool softeners, and mechanical disimpaction may be needed. The prokinetic effect of cholinergic stimulation by AChEIs might improve these symptoms in some patients.

CONCLUSIONS

Lewy body disorders are a common cause of dementia in elderly people, characterized by varying degrees of cognitive, behavioral, affective, movement, and autonomic dysfunction in older adults. The LBD syndromes are associated with the accumulation of Lewy bodies in subcortical, limbic, and neocortical regions and are characterized clinically by progressive dementia, parkinsonism, cognitive fluctuations, and visual hallucinations. Whether or not PDD and DLB reflect the same underlying disorder whose differences in symptom presentation are merely the end product of the underlying brain region(s) affected earlier or later in the disease course is the subject of much controversy. For now, current diagnostic criteria for PDD and DLB advise that clinical distinctions be maintained (“one year rule”) even though they are pathologically similar. From a neuropsychological perspective, PDD and DLB are more readily distinguished from AD than from each other. It is hoped that the identification of a prodrome of PDD may improve our understanding of the earliest cognitive changes associated with LBD. This information can then be used in conjunction with biomarkers to diagnose these disorders earlier, as well as aid in the prediction and monitoring of treatment response and development of more selective therapeutic agents. Public awareness campaigns that specifically address LBD are also hoped for, as these may aid in generating interest and understanding of this group of dementias, and maybe even stimulate efforts to develop appropriate supportive programs and services for patients and their family caregivers.

DISCLOSURES

Dr. Karantzoulis has no conflicts of interest to disclose. She serves as co-investigator for one NIH grant (R01 AG040211-A1) and one Michael J. Fox Foundation for Parkinson Research award. She does not receive financial compensation or salary support from any pharmaceutical company.

Dr. Galvin is funded by grants from the NIH, Michael J Fox Foundation, Alzheimer Association, New York State Department of Health, and Morris and Alma Schapiro Fund. Dr. Galvin serves as a consultant for Pfizer, Eisai, Baxter, Accera, Novartis, and Forest. He does mold stock or any equity in any pharmaceutical company.

REFERENCES

Aarsland, D., and Kurz, M.W. (2010). The epidemiology of dementia associated with Parkinson’s disease. Brain Pathol. 20:633–639.

Aarsland, D., Litvan, I., et al. (2003). Performance on the dementia rating scale in Parkinson’s disease with dementia and dementia with Lewy bodies: comparison with progressive supranuclear palsy and Alzheimer’s disease. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 74:1215–1220.

Aarsland, D., Perry, R., et al. (2005). Neuroleptic sensitivity in Parkinson’s disease and parkinsonian dementias. J. Clin. Psychiatry 66:633–637.

Ala, T.A., Hughes, L.F., et al. (2002). The Mini-Mental State exam may help in the differentiation of dementia with Lewy bodies and Alzheimer’s disease. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 17:503–509.

Allan, L.M., Ballard, C.G., et al. (2007). Autonomic dysfunction in dementia. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 78:671–677.

Almeida, O.P., Burton, E.J., et al. (2003). MRI study of caudate nucleus volume in Parkinson’s disease with and without dementia with Lewy bodies and Alzheimer’s disease. Dement. Geriatr. Cogn. Disord. 16:57–63.

Ballard, C.G., Aarsland, D., et al. (2002). Fluctuations in attention: PD dementia vs DLB with parkinsonism. Neurology 59:1714–1720.

Ballard, C., Holmes, C., et al. (1999). Psychiatric morbidity in dementia with Lewy bodies: a prospective clinical and neuropathological comparative study with Alzheimer’s disease. Am. J. Psychiatry 156:1039–1045.

Ballard, C., Ziabreva, I., et al. (2006). Differences in neuropathologic characteristics across the Lewy body dementia spectrum. Neurology 67:1931–1934.

Barber, R., McKeith, I.G., et al. (2001). A comparison of medial and lateral temporal lobe atrophy in dementia with Lewy bodies and Alzheimer’s disease: magnetic resonance imaging volumetric study. Dement. Geriatr. Cogn. Disord. 12:198–205.

Beyer, M.K., Larsen, J.P., et al. (2007). Gray matter atrophy in Parkinson disease with dementia and dementia with Lewy bodies. Neurology 69:747–754.

Boeve, B.F., Silber, M.H., et al. (2004). REM sleep behavior disorder in Parkinson’s disease and dementia with Lewy bodies. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry Neurol. 17:146–157.

Boeve, B.F., Silber, M.H., et al. (2007). Pathophysiology of REM sleep behaviour disorder and relevance to neurodegenerative disease. Brain 130:2770–2788.

Bohnen, N.I., Kaufer, D.I., et al. (2003). Cortical cholinergic function is more severely affected in parkinsonian dementia than in Alzheimer disease: an in vivo positron emission tomographic study. Arch. Neurol. 60:1745–1748.

Braak, H., Del Tredici, K., et al. (2003). Staging of brain pathology related to sporadic Parkinson’s disease. Neurobiol. Aging 24:197–211.

Bradshaw, J., Saling, M., et al. (2004). Fluctuating cognition in dementia with Lewy bodies and Alzheimer’s disease is qualitatively distinct. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 75:382–387.

Bronnick, K., Ehrt, U., et al. (2006). Attentional deficits affect activities of daily living in dementia-associated with Parkinson’s disease. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 77:1136–1142.

Buchman, V.L., Adu, J., et al. (1998). Persyn, a member of the synuclein family, influences neurofilament network integrity. Nat. Neurosci. 1:101–103.

Burton, E.J., Karas, G., et al. (2002). Patterns of cerebral atrophy in dementia with Lewy bodies using voxel-based morphometry. Neuroimage 17:618–630.

Burton, E.J., McKeith, I.G., et al. (2004). Cerebral atrophy in Parkinson’s disease with and without dementia: a comparison with Alzheimer’s disease, dementia with Lewy bodies and controls. Brain 127:791–800.

Calderon, J., Perry, R.J., et al. (2001). Perception, attention, and working memory are disproportionately impaired in dementia with Lewy bodies compared with Alzheimer’s disease. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 70:157–164.

Collerton, D., Burn, D., et al. (2003). Systematic review and meta-analysis show that dementia with Lewy bodies is a visual-perceptual and attentional-executive dementia. Dement. Geriatr. Cogn. Disord. 16:229–237.

Colloby, S.J., Firbank, M.J., et al. (2008). A comparison of 99mTc-exametazime and 123I-FP-CIT SPECT imaging in the differential diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease and dementia with Lewy bodies. Int. Psychogeriatr. 20:1124–1140.

Colloby, S.J., Firbank, M.J., et al. (2011). Alterations in nicotinic alpha4beta2 receptor binding in vascular dementia using (1)(2)(3)I-5IA-85380 SPECT: comparison with regional cerebral blood flow. Neurobiol. Aging 32:293–301.

Colloby, S.J., Pakrasi, S., et al. (2006). In vivo SPECT imaging of muscarinic acetylcholine receptors using (R,R) 123I-QNB in dementia with Lewy bodies and Parkinson’s disease dementia. Neuroimage 33:423–429.

Cormack, F., Aarsland, D., et al. (2004). Pentagon drawing and neuropsychological performance in Dementia with Lewy Bodies, Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease and Parkinson’s disease with dementia. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 19:371–377.

Cousins, D.A., Burton, E.J., et al. (2003). Atrophy of the putamen in dementia with Lewy bodies but not Alzheimer’s disease: an MRI study. Neurology 61:1191–1195.

Cummings, J.L., Darkins, A., et al. (1988). Alzheimer’s disease and Parkinson’s disease: comparison of speech and language alterations. Neurology 38:680–684.

Donnemiller, E., Heilmann, J., et al. (1997). Brain perfusion scintigraphy with 99mTc-HMPAO or 99mTc-ECD and 123I-beta-CIT single-photon emission tomography in dementia of the Alzheimer-type and diffuse Lewy body disease. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. 24:320–325.

Duda, J.E., Giasson, B.I., et al. (2002). Novel antibodies to synuclein show abundant striatal pathology in Lewy body diseases. Ann. Neurol. 52:205–210.

Edison, P., Rowe, C.C., et al. (2008). Amyloid load in Parkinson’s disease dementia and Lewy body dementia measured with [11C]PIB positron emission tomography. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 79:1331–1338.

Emre, M. (2003). Dementia associated with Parkinson’s disease. Lancet Neurol. 2:229–237.

Emre, M., Aarsland, D., et al. (2007). Clinical diagnostic criteria for dementia associated with Parkinson’s disease. Mov. Disord. 22:1689–1707; quiz 1837.

Ferman, T.J., Smith, G.E., et al. (2006). Neuropsychological differentiation of dementia with Lewy bodies from normal aging and Alzheimer’s disease. Clin. Neuropsychol. 20:623–636.

Friedman, J.H., and Fernandez, H.H. (2002). Atypical antipsychotics in Parkinson-sensitive populations. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry Neurol. 15:156–170.

Galvin, J.E., Malcom, H., et al. (2007). Personality traits distinguishing dementia with Lewy bodies from Alzheimer disease. Neurology 68:1895–1901.

Galvin, J.E., Pollack, J., et al. (2006). Clinical phenotype of Parkinson disease dementia. Neurology 67:1605–1611.

Gilbert, P.E., Barr, P.J., et al. (2004). Differences in olfactory and visual memory in patients with pathologically confirmed Alzheimer’s disease and the Lewy body variant of Alzheimer’s disease. J. Int. Neuropsychol. Soc. 10:835–842.

Gomperts, S.N., Rentz, D.M., et al. (2008). Imaging amyloid deposition in Lewy body diseases. Neurology 71:903–910.

Hansen, L., Salmon, D., et al. (1990). The Lewy body variant of Alzheimer’s disease: a clinical and pathologic entity. Neurology 40:1–8.

Hanyu, H., Shimizu, S., et al. (2006). Comparative value of brain perfusion SPECT and [(123)I]MIBG myocardial scintigraphy in distinguishing between dementia with Lewy bodies and Alzheimer’s disease. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging 33:248–253.

Harding, A.J., Broe, G.A., et al. (2002). Visual hallucinations in Lewy body disease relate to Lewy bodies in the temporal lobe. Brain 125:391–403.

Higuchi, M., Tashiro, M., et al. (2000). Glucose hypometabolism and neuropathological correlates in brains of dementia with Lewy bodies. Exp. Neurol. 162:247–256.

Hu, X.S., Okamura, N., et al. (2000). 18F-fluorodopa PET study of striatal dopamine uptake in the diagnosis of dementia with Lewy bodies. Neurology 55:1575–1577.

Huber, S.J., Shuttleworth, E.C., et al. (1986). Dementia in Parkinson’s disease. Arch. Neurol. 43:987–990.

Hurtig, H.I., Trojanowski, J.Q., et al. (2000). Alpha-synuclein cortical Lewy bodies correlate with dementia in Parkinson’s disease. Neurology 54:1916–1921.

Ikonomovic, M.D., Klunk, W.E., et al. (2008). Post-mortem correlates of in vivo PiB-PET amyloid imaging in a typical case of Alzheimer’s disease. Brain 131:1630–1645.

Ishii, K., Imamura, T., et al. (1998). Regional cerebral glucose metabolism in dementia with Lewy bodies and Alzheimer’s disease. Neurology 51:125–130.

Iwai, A., Masliah, E., et al. (1995). The precursor protein of non-A beta component of Alzheimer’s disease amyloid is a presynaptic protein of the central nervous system. Neuron 14:467–475.

Jellinger, K.A. (2008). Re: In dementia with Lewy bodies, Braak stage determines phenotype, not Lewy body distribution. Neurology 70:407–408.

Johnson, D.K., and Galvin, J.E. (2011). Longitudinal changes in cognition in Parkinson’s disease with and without dementia. Dement. Geriatr. Cogn. Disord. 31:98–108.

Johnson, D.K., Morris, J.C., et al. (2005). Verbal and visuospatial deficits in dementia with Lewy bodies. Neurology 65:1232–1238.

Katz, I.R., Jeste, D.V., et al. (1999). Comparison of risperidone and placebo for psychosis and behavioral disturbances associated with dementia: a randomized, double-blind trial. Risperidone Study Group. J. Clin. Psychiatry 60:107–115.

Kehagia, A.A., Barker, R.A., et al. (2010). Neuropsychological and clinical heterogeneity of cognitive impairment and dementia in patients with Parkinson’s disease. Lancet Neurol. 9:1200–1213.

Klatka, L.A., Louis, E.D., et al. (1996). Psychiatric features in diffuse Lewy body disease: a clinicopathologic study using Alzheimer’s disease and Parkinson’s disease comparison groups. Neurology 47:1148–1152.

Koeppe, R.A., Gilman, S., et al. (2008). Differentiating Alzheimer’s disease from dementia with Lewy bodies and Parkinson’s disease with (+)-[11C]dihydrotetrabenazine positron emission tomography. Alzheimers Dement. 4:S67–S76.

Kruger, R., Kuhn, W., et al. (1998). Ala30Pro mutation in the gene encoding alpha-synuclein in Parkinson’s disease. Nat. Genet. 18:106–108.

Lambon Ralph, M.A., Powell, J., et al. (2001). Semantic memory is impaired in both dementia with Lewy bodies and dementia of Alzheimer’s type: a comparative neuropsychological study and literature review. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 70:149–156.

Leplow, B., Dierks, C., et al. (1997). Remote memory in Parkinson’s disease and senile dementia. Neuropsychologia 35:547–557.

Lim, S.M., Katsifis, A., et al. (2009). The 18F-FDG PET cingulate island sign and comparison to 123I-beta-CIT SPECT for diagnosis of dementia with Lewy bodies. J. Nucl. Med. 50:1638–1645.

Lockhart, A., Lamb, J.R., et al. (2007). PIB is a non-specific imaging marker of amyloid-beta (Abeta) peptide-related cerebral amyloidosis. Brain 130:2607–2615.

Matsui, H., Udaka, F., et al. (2005). N-isopropyl-p-123I iodoamphetamine single photon emission computed tomography study of Parkinson’s disease with dementia. Intern. Med. 44:1046–1050.

McKeith, I., Del Ser, T., et al. (2000). Efficacy of rivastigmine in dementia with Lewy bodies: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled international study. Lancet 356:2031–2036.

McKeith, I., Fairbairn, A., et al. (1992). Neuroleptic sensitivity in patients with senile dementia of Lewy body type. BMJ 305:673–678.

McKeith, I., Mintzer, J., et al. (2004). Dementia with Lewy bodies. Lancet Neurol. 3:19–28.

McKeith, I., O’Brien, J., et al. (2007). Sensitivity and specificity of dopamine transporter imaging with 123I-FP-CIT SPECT in dementia with Lewy bodies: a phase III, multicentre study. Lancet Neurol. 6:305–313.

McKeith, I.G. (2000a). Clinical Lewy body syndromes. Ann. NY Acad. Sci. 920:1–8.

McKeith, I.G. (2000b). Spectrum of Parkinson’s disease, Parkinson’s dementia, and Lewy body dementia. Neurol. Clin. 18:865–902.

McKeith, I.G., Dickson, D.W., et al. (2005). Diagnosis and management of dementia with Lewy bodies: third report of the DLB Consortium. Neurology 65:1863–1872.

McKeith, I.G., Grace, J.B., et al. (2000). Rivastigmine in the treatment of dementia with Lewy bodies: preliminary findings from an open trial. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 15:387–392.

Molloy, S., McKeith, I.G., et al. (2005). The role of levodopa in the management of dementia with Lewy bodies. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 76:1200–1203.

Monsch, A.U., Bondi, M.W., et al. (1992). Comparisons of verbal fluency tasks in the detection of dementia of the Alzheimer type. Arch. Neurol. 49:1253–1258.

Namba, H., Fukushi, K., et al. (2002). Positron emission tomography: quantitative measurement of brain acetylcholinesterase activity using radiolabeled substrates. Methods 27:242–250.