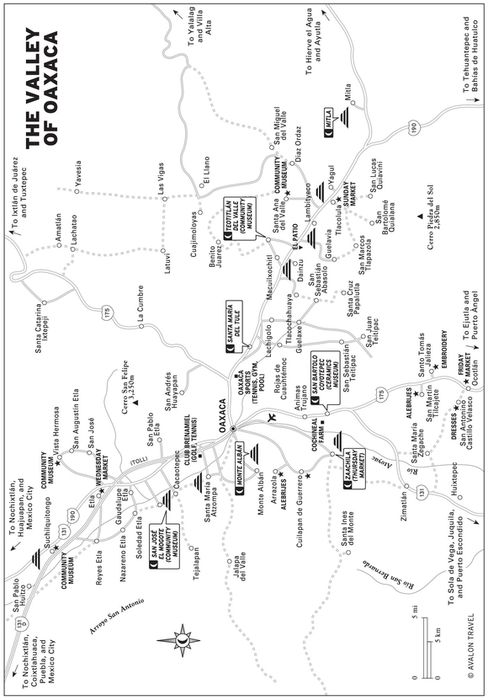

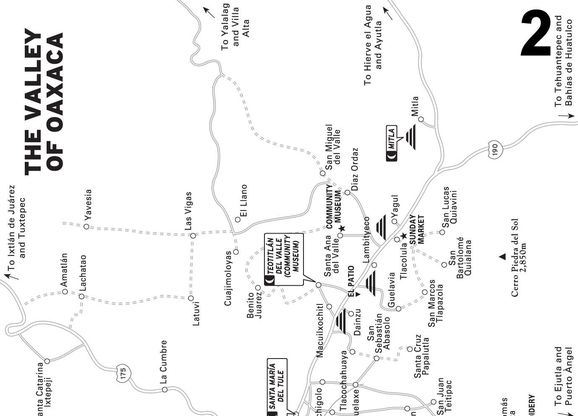

THE VALLEY OF OAXACA

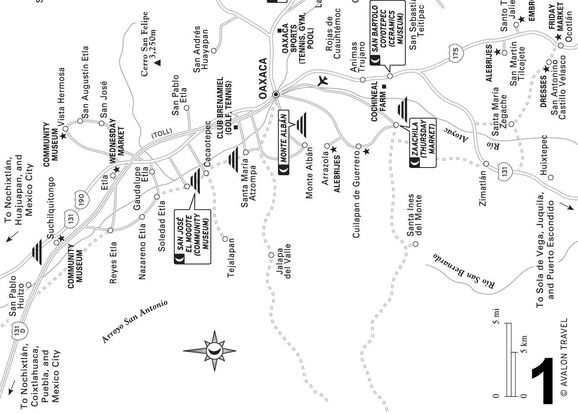

The riches, both cultural and economic, of the city of Oaxaca flow largely from its surrounding hinterland, the Valley of Oaxaca, a mountain-rimmed patchwork expanse of fertile summer-green (and winter-dry) fields, pastures, villages, and reed-lined rivers and streams. By far Oaxaca’s largest valley, both in size and population, with an aggregate population of about half that of the central city, the Valley of Oaxaca consists of three subvalleys—the Valley of Tlacolula, the Valley of Ocotlán, and the Valley of Etla—that each extend, respectively, about 30 miles east, south, and northeast of Oaxaca City.

The Valley of Oaxaca is unique in a number of ways. Most importantly, the inhabitants are nearly all indigenous Zapotec-speaking people. You will often brush shoulders with them, especially in the big markets in Tlacolula, Ocotlán, Zaachila, and Etla. The women traditionally dress in attractive bright skirts and blouses, with their hair done up in colorful ribbon-decorated braids. Although only a fraction of them speak fluent Spanish, they will nearly always understand and appreciate a smile and friendly “buenos dias” or “buenas tardes.”

The Valley of Oaxaca’s vibrant and prosperous native presence flows from a fortunate turn of history. During the mid-1800s, Mexico’s Laws of the Reform forced the sale of nearly all church lands throughout the country. In most parts of Mexico, rich Mexicans and foreigners bought up much of these holdings, but in Oaxaca, isolated in Mexico’s far southern region, there were few rich buyers, so the land was bought at very low prices by the local people, most of them indigenous farmers. Moreover, after the Revolution of 1910–1917, progressive federal-government land-reform policies awarded many millions of acres of land to campesino communities, notably to Oaxaca Valley towns Teotitlán del Valle and Santa Ana del Valle, whose residents now conserve many thousand acres of rich valley fields and foothill forests.

HIGHLIGHTS

Santa María del Tule: Townsfolk have literally built their town around their gigantic beloved El Tule tree, a cousin of the giant redwood trees of California (

Santa María del Tule: Townsfolk have literally built their town around their gigantic beloved El Tule tree, a cousin of the giant redwood trees of California ( Santa María del Tule).

Santa María del Tule).

Teotitlán del Valle: Fine wool carpets and hangings, known locally as tapetes, are the prized product of dozens of local family workshop-stores (

Teotitlán del Valle: Fine wool carpets and hangings, known locally as tapetes, are the prized product of dozens of local family workshop-stores ( TEOTITLÁN DEL VALLE).

TEOTITLÁN DEL VALLE).

Mitla: Explore the monumental plazas and columned buildings, handsomely adorned by a treasury of painstakingly placed greca (Grecian-like) stone fretwork (

Mitla: Explore the monumental plazas and columned buildings, handsomely adorned by a treasury of painstakingly placed greca (Grecian-like) stone fretwork ( MITLA).

MITLA).

San Bartolo Coyotepec: A small city of roadside home-workshops and a must-see museum display of the pearly-black pottery pioneered by celebrated potter Doña Rosa a generation ago (

San Bartolo Coyotepec: A small city of roadside home-workshops and a must-see museum display of the pearly-black pottery pioneered by celebrated potter Doña Rosa a generation ago ( SAN BARTOLO COYOTEPEC).

SAN BARTOLO COYOTEPEC).

Zaachila: Its monumental archaeological zone and riotously colorful tianguis (native market) make Zaachila a Thursday destination of choice in Oaxaca (

Zaachila: Its monumental archaeological zone and riotously colorful tianguis (native market) make Zaachila a Thursday destination of choice in Oaxaca ( Zaachila).

Zaachila).

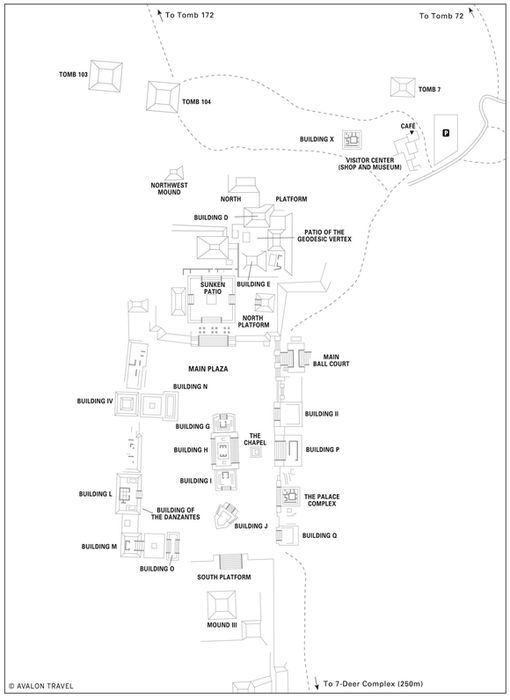

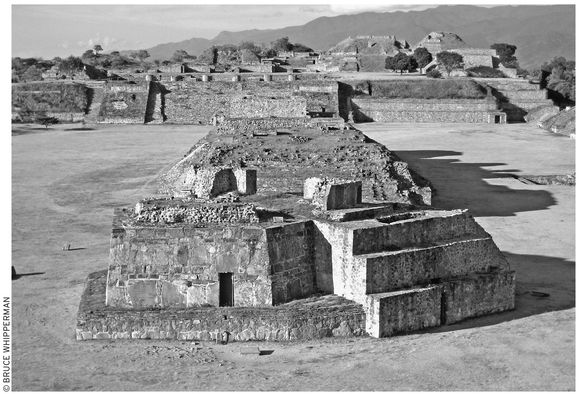

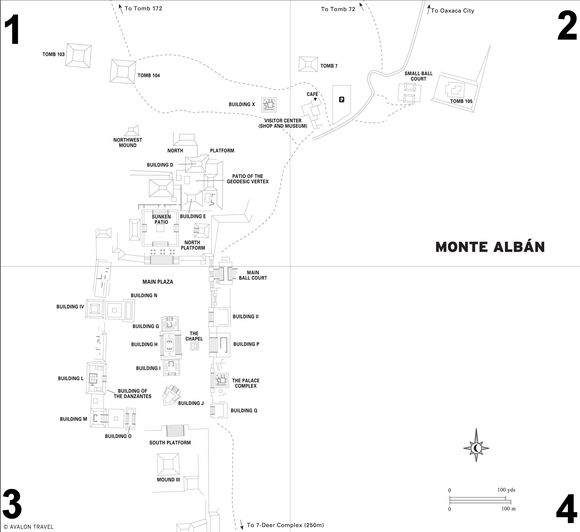

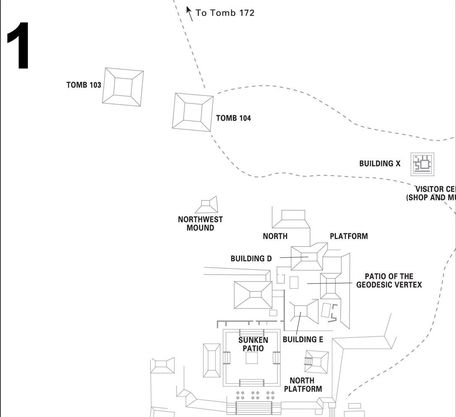

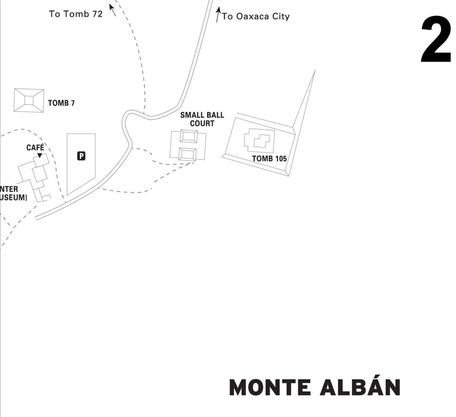

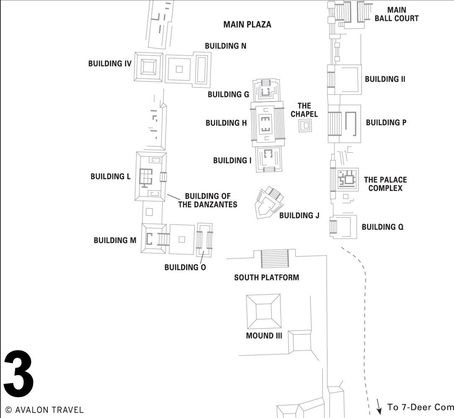

Monte Albán: Any day is a good day to visit this–Mesoamerica’s earliest true metropolis –which to some still rules from its majestic mountain-top throne (

Monte Albán: Any day is a good day to visit this–Mesoamerica’s earliest true metropolis –which to some still rules from its majestic mountain-top throne ( MONTE ALBÁN).

MONTE ALBÁN).

San José El Mogote: Its regal reconstructed pyramids and plazas and the unforgettably red diablo enchilado sculpture displayed in its community museum, plus the neighboring Etla market, make San José El Mogote a worthwhile Wednesday excursion (

San José El Mogote: Its regal reconstructed pyramids and plazas and the unforgettably red diablo enchilado sculpture displayed in its community museum, plus the neighboring Etla market, make San José El Mogote a worthwhile Wednesday excursion ( SAN JOSÉ EL MOGOTE).

SAN JOSÉ EL MOGOTE).

LOOK FOR  TO FIND RECOMMENDED SIGHTS, ACTIVITIES, DINING, AND LODGING.

TO FIND RECOMMENDED SIGHTS, ACTIVITIES, DINING, AND LODGING.

Although the grand monuments, fascinating museums, good restaurants, and inviting handicrafts shops of Oaxaca City alone would be sufficient, a visit to Oaxaca is doubly rich because of the manifold wonders of the surrounding Valley of Oaxaca. The must-see highlights of the valley are the timeless Mitla and Monte Albán archaeological sites and the fetching crafts—wool weavings, pearly black pottery, floral-embroidered blouses and dresses, and alebrijes (wood-carved animals). You could easily spend a week or more of your time touring the Valley of Oaxaca from a base in Oaxaca City.

You can even let the valley’s tianguis (literally, “shade awnings” and synonymous with “native markets”) guide you along your excursion path. Along the way, beneath the shadowed market canopies and the shops of Oaxaca’s welcoming local people, you can look, choose, and bargain for the wonderful handicrafts that travelers from all over the world come to the Valley of Oaxaca to buy.

PLANNING YOUR TIME

If your time is limited, your enviable task is to pick, according to your own interests, the best of the best from the Valley of Oaxaca’s treasury of colorful markets, bucolic handicrafts villages, mysterious archaeological sights, and community museums. In a whirlwind four or five days, you can soak in the valley’s celebrated highlights, scheduling your time according to the weekly market days.

Given the limited hotel choices in the Valley of Oaxaca and the relatively short distances (16–48 km/10–30 mi) to valley sights from Oaxaca City, you could use your lodging in the city as a home base and take excursions from there to explore the valley.

For transportation, you could hire a guide for about $150–200 per day, which should include a car for 4–5 people; rent a car for around $50 per day ($250 per week); or use private tourist bus transportation for $10–15 per person. Each of these options can get you to most of the valley’s highlights over three or four days. A fourth option, touring by local public bus from camionera central segunda clase (second-class bus station) is much cheaper, but it requires twice the time.

Some sights you won’t want to miss are the archaeological zones of Mitla, on the east side, and Monte Albán, on the southwest side of the valley. Of the markets, the biggest are the Tlacolula Sunday market, the Ocotlán Friday market, the Etla Wednesday market, and the Zaachila Thursday market. Fascinating crafts villages along the way are Teotitlán del Valle (on the way to Tlacolula and Mitla); Santo Tomás Jalieza, San Martín Tilcajete, and San Bartolo Coyotepec (on the way back to Oaxaca City from Ocotlán); and the Santa María Atzompa pottery village (on the way to or from Monte Albán).

If your time is very limited, you could skip the Tlacolula market, but make sure to visit the Thursday market in Zaachila, unbeatable for its intensely colorful ambience and exotic fruits and other food. Be sure to include the nearby Zaachila archaeological site in your visit.

On the other hand, if you have an extra day, it would be worthwhile to visit the San José El Mogote archaeological site and the adjacent community museum. Continue to the Etla market, especially good on Wednesdays.

GETTING AROUND

Taxis, Buses, and Rental Cars

For short runs in downtown Oaxaca, street taxis ($2–3, 25–35 pesos) are quick and secure. Be sure to establish the price before getting into the taxi. If it’s too high, hail another taxi.

For Oaxaca Valley touring, the cheapest (but not quickest) option is to ride a bus from the west-side Abastos market camionera central segunda clase (second-class bus terminal). The buses run everywhere in the Valley of Oaxaca and beyond. Arrive early any day and you could cover most major valley destinations in about a week: two days east (Teotitlán, Tlacolula, Mitla), two days south (crafts villages, Ocotlán market), two days southwest and west (Zaachila market and archaeological site, Cuilapan, Arrazola, Monte Albán, and Atzompa), and one day northwest (Etla market and San José El Mogote).

Get to the second-class bus terminal by walking one block south from the zócalo’s southwest corner, turn right at Las Casas, and keep walking about seven blocks. With caution, cross the periférico. The big terminal is two blocks farther, on the right.

More leisurely options include renting a car or riding a private tourist bus, or both. Get your car rental through either a travel agent or U.S. and Canadian toll-free car rental number before you leave home, or in Oaxaca locally: Hertz (at airport, or Valdivieso 100, tel. 951/139-8845, cell tel.044-951 /508-8721, oax60@avasa.com); Alamo (at airport or Cinco de Mayo 203, tel. 951/511-6220, tel./ fax 951/514-8534, fax 951/514-8686, oaxalamo@hotmail.com); and Europcar (at airport, or at Matamoros 101, tel./fax 951/143-8340, toll-free tel. in Mexico, tel. 800/201-1111 or 800/201-2084).

For economical private transportation-only tourist buses, a good bet is to go with Viajes Turísticos Mitla (at Hóstal Santa Rosa, Trujano 201, tel./fax 951/514-7800 or 951/514-7806, fax 951/514-3152), a block west of the zócalo’s southwest corner. They offer many tours, including a guide and transportation, for small- or medium-size groups. You can also contact their main office (Mina 501, tel./fax 951/514-3152), three blocks west, three blocks south of the zócalo’s southwest corner.

Guided Tours

Many private individual guides offer tours. One of the the most highly recommended is fluent-in-English Juan Montes Lara (Prol. de Eucaliptos 303, Colonia Reforma, tel./fax 951/513-0126, jmonteslara@yahoo.com, $25/ hour), backed up by his wife Karin Schutte. Besides cultural sensitivity and extensive local knowledge, they can also provide comfortable transportation in a Chrysler van.

Moreover, satisfied customers rave about guide Sebastiañn Chino Peña (local cell tel. 044-951/508-1220, tel. 951/562-1761, sebastian_oaxaca@hotmail.com, $20/hour). He offers tours of anywhere you would like to go in the Valley of Oaxaca.

Another promising guide option is Judith Reyes López (B&B Oaxaca Ollin, Quintana Roo 213, tel./fax 951/514-9126, ju-dithreyes37@hotmail.com or reservations@oaxacaollin.com, www.oaxacaollin.com), who operates through her Art and Tradition tours. Judith offers tours ranging from half-day city tours and whole-day Valley of Oaxaca archaeological and crafts-village outings to farther-reaching explorations of the art and architecture of venerable Dominican churches in the Mixteca. Contact her at her bed-and-breakfast, Oaxaca Ollin, a block north and a block east of the Centro Cultural de Santo Domingo.

On the other hand, folks interested in the exceedingly diverse natural world of Oaxaca might appreciate a tour led by biologist Fredy Carrizal Rosales, owner-operator of Tourism Service in Ecosystems (tel. 951/515-3305, in-town cell tel. 044-951/164-1897, ecologiaoax-aca@yahoo.com.mx). Fredy offers customized explorations of many Oaxaca locations—pine-oak woodlands, coastal mangrove wetlands, semi-desert highlands, lush coastal foothill forest coffee plantations—viewing and identifying plants and animals and enjoying nature in general.

Customized explorations of Oaxaca’s indigenous communities, traditions, and natural treasures are the specialty of native Zapotec guide Florencio Moreno, who operates Academic Tours in Oaxaca (Nieve 208A, Colonia Reforma, home tel. 951/518-4728, in-town cell tel. 044-951/510-2244, info@academictoursoaxaca.com, www.academictoursoaxaca.com). Florencio’s tours reflect his broad qualifications: fluency in native dialects, historical knowledge, cultural sensitivity, personal connections with indigenous crafts communities, and expertise in wildlife-watching and identification. His excursions can be designed to last a day or a week and include any region of Oaxaca, exploring anything from folk art and hidden archaeological sites to the colorful indigenous markets and festivals of the Mixteca or the Isthmus.

Higher up the economic scale, commercial guided tours also provide a hassle-free means of exploring the Valley of Oaxaca. Travel agencies, such as Viajes Turisticos Mitla (at Hóstal Santa Rosa, Trujano 201, tel./fax 951/514-7800 or 951/514-7806, fax 951/514-3152), Viajes Xochitlán (M. Bravo 210A, tel. 951/514-3271 or 951/514-3628, www.xochitlan-tours.com.mx, oaxaca@xochitlan-tours.com.mx, 9 A.M.–2 P.M. and 4–7 P.M. Mon.–Sat.), and others, offer such tours.

For even more guide recommendations, check at the Oaxaca state tourist information office (Av. Juárez 703, west side of El Llano park, tel. 951/516-0123, www.aoxaca.com, info@aoaxaca.com, 8 A.M.–8 P.M. daily).

East Side: The Textile Route

The host of colorful enticements along this path could tempt you into many days of delightful exploring. For example, on Saturday you could head out, visiting the great El Tule tree and the weavers’ shops in Teotitlán del Valle and continuing east for an overnight at Mitla. Next morning, explore the Mitla ruins, then return, stopping at the hilltop Yagul archaeological site and the Sunday market at Tlacolula. In either direction, going or coming from the city, you could pause for a brief exploration at the Dainzu and Lambityeco roadside archaeological sites.

One more day would allow time to venture past Mitla to the remarkable mountainside springs and limestone mineral deposits at Hierve El Agua. Stay longer and have it all: a two- or three-day stay in a colorful market town, such as Tlacolula, with a side trip to visit the textile market and community museum at Santa Ana del Valle and also perhaps to a quiet backcountry village, such as San Bartolomé Quialana or San Marcos Tlapazola, south of Tlacolula.

EL TULE AND TLACOCHAHUAYA

Santa María del Tule

Santa María del Tule

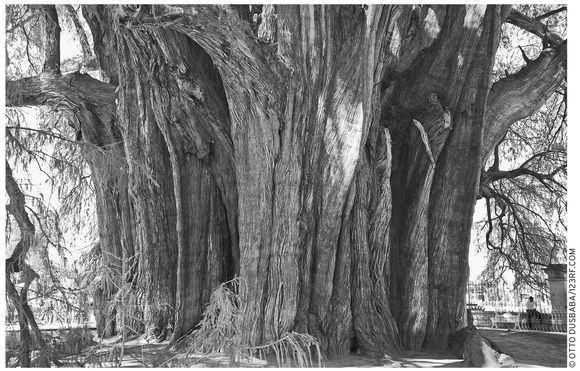

El Tule is a gargantuan Mexican ahuehuete (cypress), probably the most massive tree in Latin America. Its gnarled, house-size trunk divides into a forest of elephantine limbs that rise to bushy branches reaching 15 stories overhead. The small town of Santa María del Tule, 14 kilometers (nine mi) east of Oaxaca City on Highway 190, seems built around the tree. A crafts market, a church, and the town plaza, where residents celebrate their El Tule with a fiesta on October 7, all surround the beloved 2,000-year-old living giant.

Note: Eastbound Highway 190 to El Tule divides inbound traffic, either to the left along a town bypass, beneath a viaduct, or to the right, passing over the viaduct to the town and the El Tule tree.

Tlacochahuaya

At San Jerónimo Tlacochahuaya (tlah-koh-chah-WYE-yah), about seven kilometers (four mi) east of El Tule, stands the village’s pride and joy, the venerable 16th-century Templo y Ex-Convento de San Jerónimo. Dominican padres and their native acolytes, under the guidance of Father Jordán de Santa Catalina, began its construction in 1586 and completed it a few decades later.

Tlacochahuaya is usually a quiet little town except during holidays, notably the eight days of processions, dances, fireworks, and food that climax on September 30, the feast day of San Jerónimo.

The church’s relatively recent 1991 restoration glows so brilliantly, especially from the white baroque facade, that, standing beneath the spreading wild fig tree in the courtyard (or more precisely, atrium), you can feel the facade reflecting the warmth of the late afternoon sun. The atrium appears big enough to assemble a crowd of about 5,000 folks, probably the number of local indígenas the padres hoped to convert during the 16th century. At the atrium’s corners stand the three open-air but arch-roofed chapels, or pozas, where the conversions took place.

El Tule may be the largest cypress tree in Latin America.

Above the entrance portal, see San Jerónimo standing piously, his left hand on a skull, listening for the voice of God. Inside, glance upward at the lovely nave ceiling and appreciate the still-vital spirit of those long-dead artists who created its flowery, multicolored swirls. Look for the group of oil paintings depicting the legend of the Virgin of Guadalupe, with the last showing the roses miraculously tumbling from Juan Diego’s cape, emblazoned with her image.

Once when I visited, near the entrance was the pledge of the Sacerdote de Cristo (Priest of Christ), which, translated, reads:

The priest of Christ offers

THIS MASS

As if it were your

FIRST MASS

As if it were your

ONLY MASS

As if it were your

LAST MASS

Get there by car, guide, or the Sociedad Cooperativa Valle del Norte or Fletes y Pasajes local bus from the camionera central segunda clase in Oaxaca City.

DAINZU AND LAMBITYECO ARCHAEOLOGICAL SITES

Among the several Valley of Oaxaca buried cities, Dainzu and Lambityeco, both beside Highway 190, are the most accessible. Dainzu comes first, on the right, about nine kilometers (six mi) east of El Tule.

Dainzu

Dainzu (in Zapotec, “Hill of the Organ Cactus”; Hwy. 190, no phone, 10 A.M.–5 P.M. daily, $3) spreads over an approximate half-mile square, consisting of a partly restored ceremonial center surrounded by clusters of unexcavated mounds. Beyond that, on the west side, a stream runs through fields, which at Dainzu’s apex (around A.D. 300) supported a town of about 1,000 inhabitants.

The major excavation, at the foot of the hill about a hundred yards south of the parking lot, reveals more than 30 bas-reliefs of ball players draped with leather head, arm, and torso protectors. Downhill, to the west, lies the partly reconstructed complex of courtyards, platforms, and stairways. The northernmost of these was excavated to reveal a tomb, with a carved door supporting a jaguar head on the lintel and arms—note the claws extending down along the stone doorjambs. The jaguar’s face, with a pair of curious vampire teeth and curly nostrils, appears so bat-like that some investigators have speculated that it may represent a composite jaguar-bat god.

A couple of hundred yards diagonally southwest you’ll find the ball court running east–west in the characteristic I-shaped layout, with a pair of “scoring” niches at each end and flanked by a pair of stone-block grandstandlike seats. Actually, archaeologists know that these were not seats, because the blocks were once stuccoed over, forming a pair of smooth inclined planes (probably used for glancing shots) flanking the central playing area.

Lambityeco

Ten kilometers (six mi) farther, Lambityeco (Hwy. 190, 10 A.M.–5 P.M. daily) is on the right, a few miles past the Teotitlán del Valle side road. The excavated portion, only about 100 yards square, is a small but significant part of Yegui (Small Hill in Zapotec), a large buried town dotted with hundreds of unexcavated mounds covering about half a square mile. Salt-making appears to have been the main occupation of Yegui people during the town’s heyday, around A.D. 700. The name “Lambityeco” may derive from the Arabic-Spanish alambique, the equivalent of the English “alembic,” or distillation or evaporation apparatus. This would explain the intriguing presence of more than 200 local mounds. It’s tempting to speculate that they are the remains of cujetes, raised leaching beds still used in Mexico for concentrating brine, which workers subsequently evaporate into salt.

In the present small restored zone archaeologists have uncovered, besides the remains of the Valley of Oaxaca’s earliest known temazcal (a curative hot room), a number of fascinating ceramic sculptures. Next to the parking lot, a platform, mound 195, rises above ground level. If, after entering through the gate, you climb up its partially restored slope and look down into the excavated hollow in the adjacent east courtyard, you’ll see stucco friezes of a pair of regal, lifelike faces, one male and one female, presumably of the personages who were found buried in the royal grave (Tomb 6) below. Experts believe this to be the case, because the man was depicted with the symbol of his right to rule—a human femur bone, probably taken, as was the custom, from the grave of his chieftain father.

See TOWN NAMES

Mound 190, sheltered beneath the adjacent large corrugated roof about 50 yards to the south, contains a restored platform decorated by a pair of remarkably lifelike, nearly identical divine stucco masks. These are believed to be of Zapotec rain god Cocijo (see the water flowing from the mouths). Notice also the rays, perhaps lightning, representing power, in one hand, and flowers, for fertility, in the other.

TEOTITLÁN DEL VALLE

TEOTITLÁN DEL VALLE

Teotitlán del Valle (pop. 5,000), 14 kilometers (nine mi) east of El Tule, at the foot of the northern Sierra, means “Place of the Gods” in Nahuatl; before that, it was known, appropriately, as Xa Quire (shah KEE-ray), or “Foot of the Mountain,” by the Zapotecs who settled it at least 2,000 years ago (by archaeologists’ estimate). From the age of artifacts uncovered beneath both the present town and at nearby sites, experts estimate that approximately 1,000 people were living in Teotitlán by A.D. 400.

Present-day Teotitlán people are relatively well off, not only from sales of their renowned tapetes (wool rugs), but from their rich communal landholdings. Besides a sizable swath of valley-bottom farmland and pasture, which every Teotitlán family is entitled to use, the community owns a dam and reservoir and a small kingdom of approximately 100,000 acres of sylvan mountain forest and meadow, spreading for about 32 kilometers (20 mi) along the Valley of Oaxaca’s lush northeastern foothills.

Getting Oriented

Teotitlán del Valle has two principal streets: Juárez, the entrance road, which runs northerly about four kilometers (2.5 mi) from the highway; and Hidalgo, which intersects Juárez at the center of town. Turn right at Hidalgo (where the pavement becomes cobbled) and you’ll be looking east, toward the town plaza and the 17th-century town church behind it.

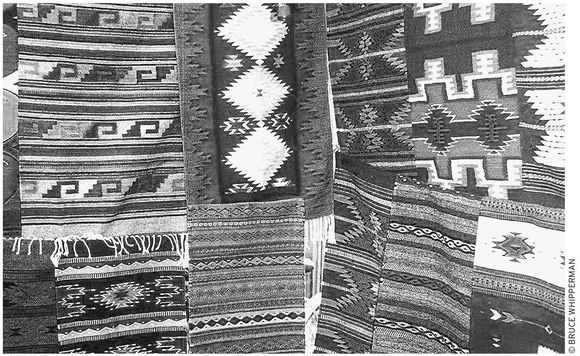

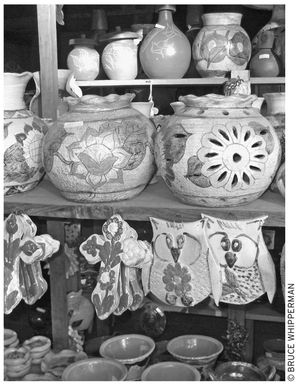

Textile Shops

Nearly every Teotitlán house is a mini-factory where people card, spin, and color wool, often using hand-gathered natural dyes. Each step of wool preparation is laborious; obtaining pure water is even a chore—families typically spend two days a week collecting it from mountain springs. The weaving, on traditional handlooms, is the final, satisfying part of the process. The best weaving is generally the densest, typically packing in about 18 strands per centimeter (45 strands per inch); ordinary weaving incorporates about half that. Please don’t bargain too hard. Even the highest prices typically bring the weavers less than a dollar an hour for their labor.

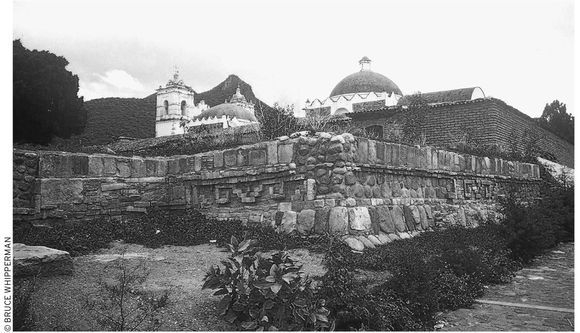

The Teotitlán del Valle church is built on the original Zapotec temple’s foundation.

Visiting the workshop-stores should be first on your itinerary. The home workshops, once confined to the town center, now sprinkle nearly the entire mile-long entrance road. Half a kilometer (about 0.25 mi) from Highway 190, be sure to visit the cooperative shop Mujeres Que Tejan (Women Who Weave; Juárez, old number 86, new number 162, tel. 951/166-6174), on the right side. The shop is managed by welcoming sparkplug Josefina Jiménez and displays the fine for-sale woven products of 28 women weavers.

In the town center, also be sure not to miss the shop of renowned master Isaac (“Bug in the Rug”) Vasquez (turn left at main crossstreet Hidalgo, number 30, tel. 951/524-4122, 10 A.M.–6 P.M. daily).

A number of Teotitlán workshops are especially welcoming. For example, step into the workshop-restaurant-hotel El Descanso (Juárez 51, tel. 951/524-4152, 8 A.M.–7 P.M. Mon.–Sat., 8 A.M.–3 P.M. Sun.), at the town-center corner of Juárez and Hidalgo.

Also well worth a visit is the charming garden shop of friendly Luis Martínez Jiménez (Juárez 48, tel. in Oaxaca city, 951/516-1675), on the main street. (Luis also arranges very reasonably priced tours by car, check with him at petite Oaxaca City shop: Macedonio Alacalá 402, at the Santo Domingo church corner.)

For some good Teotitlán del Valle tips, visit Ron Mader’s super website (www.planeta.com/ecotravel/mexico/oaxaca/teotitlan.html).

Community Museum

Allow enough time to visit the community museum Balaa Xtee Guech Gulal (Hidalgo, tel. 951/524-4463, 10 A.M.–6 P.M. Tues.–Sun., $3), whose name translates from the local Zapotec as “Shadow of the Old Town.” It’s on the north side of Hidalgo, about a block east of Juárez. Step inside and enjoy the excellent exhibits that illustrate local history, industry, and customs. One display shows the wool-weaving tradition (introduced by the Dominican padres, that replaced the indigenous cotton-weaving craft), including sources of some natural dyes—cochinilla (red cochineal), musgo (yellow moss and lichens), anil (dark blue indigo), and quizache bean (black). Another exhibit shows the local practice of a prospective groom’s service to the bride’s parents. A house mock-up shows the prospective bride making tortillas. Be sure to get a copy of the good English-language explanatory pamphlet.

woolen weavings for sale in Teotitlán del Valle

A Walk Around Town

If you ask, a community museum volunteer may be available to lead you on a walking tour of the town and environs. English-speaking Zeferino Mendoza is especially recommended. Walking tour highlights often include visits to weavers’ homes, the church, a traditional temazcal, the recently reconstructed foundation stones of the ancient town, the dam and lake, and the hike to Picacho, the peak above the town’s west side.

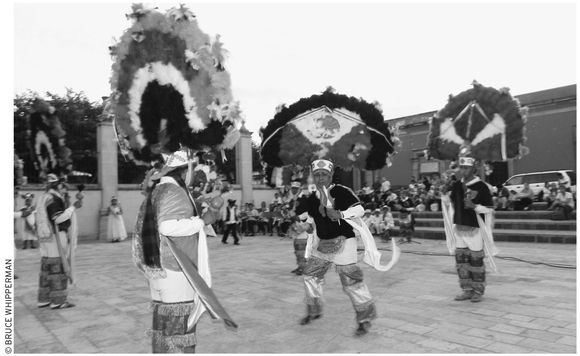

Lacking a guide, simply stroll out on your own self-guided tour. After seeing the community museum, head east on Hidalgo. If you haven’t already, take a look around the plaza-front textile stalls, then continue to the Templo de la Precioso Sangre de Cristo (Church of the Precious Blood of Christ). This is the central location for both the patronal festival (July 1–15) and the Fiesta del Señor de La Natividad (Festival of the Lord of the Nativity; first Sun. in Sept.), which include processions, fireworks, and the spectacular Danza de las Plumas (Dance of the Feathers).

The Teotitlán Church

The church itself, built over an earlier Zapotec temple, contains many interesting pre-Columbian stones, which the Dominican friars allowed to be incorporated into its walls. Notice the corn motif carved into the front doorway arch, similar in style to the monolith built into the outside wall at the right of the church entrance steps. Inside, admire the nave’s flowery overhead decorations and the colorful Bible-story paintings. Continue from the nave into the intimate claustro (cloister) and see the Zapotec god of the wind, with stone curls curving upward to represent the wind (on the southwest corner column, to the right as you enter from the nave).

the Dance of the Feathers

Outside, behind the church, continue to the reconstructed foundation corner, on the street, downhill, of the original Zapotec temple. Notice the uniquely Zapotec stone fretwork, similar to the famous Greca remains at Mitla, 32 kilometers (20 mi) farther east.

Farther Afield

If you have time, you can venture even farther afield. One option is to walk or drive along the bumpy, but passable, uphill gravel continuation of main street Juárez about 1.6 kilometers (one mi) to the town dam. After the summer rains, the reservoir fills and forms a scenic lake, good for swimming, picnicking, and even possibly camping, along its pastoral mountain-view shoreline. If you plan to camp at the Teotitlán reservoir, first ask for permission at the community museum (Hidalgo, tel. 951/524-4463, 10 A.M.–6 P.M. Tues.–Sun.) or the presidencia municipal (951/524-4123, www.teotitlandelvalle.gob.mx).

Travelers can extend their Teotitlán adventure all the way into the neighboring mountains. From the Teotitlán reservoir, hike (be prepared with water, good shoes, and a hat), hitchhike, taxi, or drive about 19 more kilometers (12 mi) uphill (with an elevation gain of 1,500 meters/5,000 feet) along the good gravel road to pine-shadowed Benito Juárez and Cuajimoloyas mountain hamlets in northern Oaxaca.

Back at the Teotitlán reservoir, you can also venture up the slope of Picacho, the steep, peaked hill 1.6 kilometers (one mi) west of town. The usual route from town is along Calle 2 de Abril, which heads west, bridging the west-side arroyo. Continue uphill, bearing right at the fork, on to the dirt road at the base of the hill. First you’ll pass some houses, then continue, curving left around the hillside. Eventually, before the summit, you’ll pass some cuevitas (small caves), a holy site where local folks have been gathering for sacred ceremonies each New Year’s Day since before anyone can remember.

Accommodations and Food

Sample Teotitlán’s best at the traditional Tlamanalli restaurant (on Juárez, about a block south of Hidalgo, no phone, 1–4 P.M. daily except possibly Mon. and Thurs., longer hours when more people stop by, $5–10). Their menu of made-to-order Zapotec specialties, such as sopa de calabaza (squash soup) and guisado de pollo (chicken stew) is limited, but highly recommended by Oaxaca City chefs.

If Tlamanalli is closed, go to the inviting Restaurant El Descanso (Juárez 51, tel. 951/524-4152, weaving shop and restaurant 8 A.M.–7 P.M. Mon.–Sat., 8 A.M.–3 P.M. Sun.; lodging $40 d). Your hosts will be the welcoming family of Edmundo and Alicia Montaño, who, besides crafting and selling lovely wool weavings, also serve tasty country fare and offer a number of rooms that open on to their leafy and lovely inner garden-patio. Choices include king-size, regular double, and single beds.

Alternatively, for a lunch or early dinner treat, stop at showplace  Restaurant El Patio (Hwy. 190, 1.2 km/0.8 mile east of the Teotitlán entrance road, tel. 951/514-4889, 10 A.M.–6 P.M. Tues.–Sun.). The restaurant centers around an airy patio, decorated by antique country furniture and a fetching gallery of scenes from the 1940s-era films of the Mexican Golden Age of cinema. The finale is the food: tasty traditional Oaxacan dishes, such as ensalada Oaxaqueña, Zapotec soup, and the house specialty botana Don Pepe.

Restaurant El Patio (Hwy. 190, 1.2 km/0.8 mile east of the Teotitlán entrance road, tel. 951/514-4889, 10 A.M.–6 P.M. Tues.–Sun.). The restaurant centers around an airy patio, decorated by antique country furniture and a fetching gallery of scenes from the 1940s-era films of the Mexican Golden Age of cinema. The finale is the food: tasty traditional Oaxacan dishes, such as ensalada Oaxaqueña, Zapotec soup, and the house specialty botana Don Pepe.

Getting There

You can go to Teotitlán del Valle by car, tour, taxi, or bus. Drivers: Simply turn left from Highway 190 at the signed Teotitlán del Valle side road, 14 kilometers (nine mi) east of El Tule. By bus: Ride a Fletes y Pasajes Tlacolula- or Mitla-bound bus from the camionera central segunda clase (in Oaxaca City by the Abastos market at the end of Las Casas, past the periférico west of downtown). Alternatively, ride the hourly Valle del Norte bus from the camionera central segunda clase parking lot. Get off at the signed bus stop and walk, taxi, or hitchhike the four kilometers (2.5 mi) into town.

SANTA ANA DEL VALLE

This is a sleepier version of Teotitlán del Valle, where virtually every family speaks the Zapotec tongue at home and earns at least part of its living through weaving. Many older folks understand Spanish only with difficulty. Santa Ana del Valle, like Teotitlán, has thousands of acres of communal lands in the valley bottom and mountains north of the town. Nearly all households tend plots of corn, beans, and vegetables. Most also graze cattle, sheep, and goats in specified communal areas. These lands have been traditionally held by the town since before the conquest. Families may buy or sell shares of their allotted land, but only within the Santa Ana del Valle community.

Community Museum

Your first stop should be at the excellent community museum Shan Dany (tel. 951/562-1705, 11 A.M.–3 P.M. and 4–7 P.M. Mon.–Sat.), on the town plaza opposite the presidencia municipal. The exhibits include an archaeological section with pre-conquest remains found during a recent plaza-front construction project. Also notice the ponderous monolith, brought from the mountain above town, carved with the visage of Cocijo, the god of lightning and rain. Another museum section details 1910–1917 revolutionary history, when townsfolk had to flee to the hills and wage a guerrilla war against rampaging forces of “Primer Jefe” General Venustiano Carranza.

Toward the rear of the museum, a pair of excellent displays illustrate more community lore: one shows many of the naturally occurring dyes, including avocado seeds, guaje bark, and copal bark, that local weavers gather and use; the other explains the Danza de la Pluma (Dance of the Feathers), in which a dozen young men dance and brighten the town plaza with their huge, round feathered hats. This dance takes place during the July 26 and August 14–16 split-date festival in honor of Santa Ana.

A Walk Around Town

Ask and a museum volunteer may be able to find a guide (offer to pay) to lead you on a two- or three-hour recorrido (tour) around town, including the presa (dam and small reservoir); a creek, where you can cool off during the summer rainy season (bring your bathing suit); a breezy mirador (viewpoint) for a spectacular valley vista; and an old gold, silver, and copper mine. During the walk, your guide might identify and explain the uses of the many medicinal plants along the path. Be sure to ask them to point out the poison oak–like mala mujer (bad woman) bush to you. Finally, ask them to take you to shops of outstanding local weavers for demonstrations and possible purchases of their work.

If you can’t get a guide, you can still do most of the walk on your own. The path to the dam takes off from Calle Plan de Ayala, on the east, uphill side of town. After about 0.8 kilometers (0.5 mi), bear left, around the hill. If you get confused, ask a younger person (they’re most likely to understand Spanish), “¿Donde está la presa” (PRAY-sah), “por favor?” The viewpoint, the big moss-mottled rock about halfway up the steep, left-hand slope, sticks out of the hillside above the path to the dam.

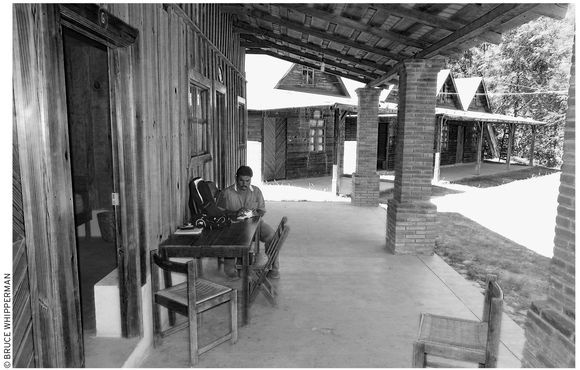

Accommodations

The comfortable Santa Ana del Valle tourist  cabaña ecoturística is at Calle Moreles #2, on the entrance road to town. It is well situated for exploring, being just a few blocks from the center of town. The nightly rate is approximately $30 for one to four people, with toilet, hot-water shower-bath, and two double or bunk beds. Reserve at the community museum (on the town plaza, tel. 951/562-1705, 11 A.M.–3 P.M. and 4–7 P.M. Mon.–Sat.), either in person or by telephone.

cabaña ecoturística is at Calle Moreles #2, on the entrance road to town. It is well situated for exploring, being just a few blocks from the center of town. The nightly rate is approximately $30 for one to four people, with toilet, hot-water shower-bath, and two double or bunk beds. Reserve at the community museum (on the town plaza, tel. 951/562-1705, 11 A.M.–3 P.M. and 4–7 P.M. Mon.–Sat.), either in person or by telephone.

Shopping

Although Santa Ana del Valle weavers sell much of their work through shops in Teotitlán del Valle and Oaxaca City, they also sell directly in town, from both the Mercado de Artesanías on the town plaza and their home workshops. For suggestions of who to visit, ask at the community museum (on the town plaza, tel. 951/562-1705), or go directly to Casa Martínez (Matamoros 3, corner of V. Carranza, tel. 951/562-0366), the house of personable master weaver Ernesto Martínez. His house is around the corner, a few doors downhill from the town plaza. You’ll also be welcome at the home shop of the friendly weaving family of Alberto Sánchez Garcia (Sor Juanes Inés de la Cruz 1, no phone), a few blocks from the town plaza.

For some good Santa Ana del Valle tips, visit Ron Mader’s super website (www.planeta.com/ecotravel/mexico/oaxaca/santana.html).

Getting There

You can go to Santa Ana del Valle by car, tour, taxi, or bus. Drivers: Turn left at the fork across Highway 190 from the Tlacolula Pemex gasolinera 38 kilometers (24 mi) east of Oaxaca City. After 0.8 kilometers (0.5 mi), turn left again at the signed Santa Ana del Valle side road. Continue another few minutes; pass the tourist cabaña ecoturística on the right, and arrive at the town plaza a few blocks farther. By bus, you can ride a Tlacolula- or Mitla-bound bus from the camionera central segunda clase in Oaxaca City by the Abastos market (end of Las Casas, west of downtown). Get off at the Tlacolula stop on Highway 190 by the Pemex station. Cross to the side road on the north side of the highway and take a taxi, ride the Transportes Municipal del Santa Ana del Valle local bus, or hike the 6.4 kilometers (four mi) from the highway—walk the side road 0.8 kilometers (0.5 mi) to a signed Santa Ana del Valle fork; go left and continue for 3.2 more kilometers (two mi), passing the cabaña ecoturística, at Calle Moreles #2, on the right, and then on to the town plaza a few blocks farther.

TLACOLULA

The Zapotec people who founded Tlacolula (pop. 15,000, 38 km/24 mi east from Oaxaca City) around A.D. 1250 called it Guichiibaa (“Place Between Heaven and Earth”). Besides its beloved church and chapel and famous Sunday market, Tlacolula is also renowned for mescal, a Tequila-like alcoholic beverage distilled from the fermented hearts of maguey. Get a good free sample at the friendly Pensamiento shop (Juárez 9, tel. 951/562-0017, 9 A.M.–7 P.M. daily), about four blocks from the highway gasoline station (along Juárez) toward the market. Besides many hand-embroidered Amusgo huipiles and Teotitlán weavings, proprietor Guadalupe Pensamiento offers fruit and spice-flavored mescal, which, at this writing, came in 40 flavors, 16 for men and 24 for women.

Just before the market, take a look inside the main town church, the 1531 Parroquia de la Virgen de la Asunción. Although its interior is distinguished enough, the real gem is its attached chapel, Capilla del Señor de Tlacolula, which you enter from the nave of the church. Every inch of the chapel’s interior gleams with sculptures of angels and saints, paintings, and gold scrollwork. Notice the pair of floating angels, each holding a great pendulous solid silver censer, on opposite sides of the altar; also, admire the solid silver fence in front of the altar. Saints seem to live on in every corner of the chapel. Especially graphic are the martyrs, who reveal the way they died, such as a sorrowful San Sebastián, his body shot full of arrows, and a decapitated San Pablo, above the right transept, his head on the ground.

Ordinarily tranquil, the church grounds seem to nearly burst with the faithful during the five-day Fiesta del Santa Cristo de Tlacolula, climaxing on the second Sunday of October, when the plaza is awash with merrymakers. It is then that folks enjoy their favorites, the Danza de los Jardineros (Dance of the Gardeners) and the spectacular Danza de las Plumas (Dance of the Feathers), along with a pelota mixteca (traditional Mixtec ball game) tournament.

The big gate bordering the church grounds leads you to the Tlacolula market. One of Oaxaca’s biggest and oldest, the Tlacolula market draws tens of thousands from all over the Valley of Oaxaca every Sunday. Wander around and soak it all in—the diverse crowd of buyers and sellers, and the equally manifold galaxy of merchandise. How about a hand-hewn yoke for your oxen, or a new stone mano (roller) and metate (flat stone) for your kitchen? If not, perhaps some live (or ground) chapulines (grasshoppers), maybe a live turkey for dinner tomorrow, or a hunk of sugarcane to chew on while you stroll?

For food and accommodations, try the basic but clean downtown Tlacolula lodging, the Hotel and Restaurant Calenda (Juárez 40, tel. 951/562-0660, food $3–8, lodging $20 s or d, $30 t). They offer about 30 rooms with fans and hot-water shower-baths in three floors around an interior restaurant courtyard. Their restaurant serves a wholesome country menu that, although specializing in barbacoa pollo, chivo, or borrego (barbecue chicken, goat, or lamb), offers many more hearty choices, such as pork chops, spaghetti, eggs, fish, and chiles rellenos.

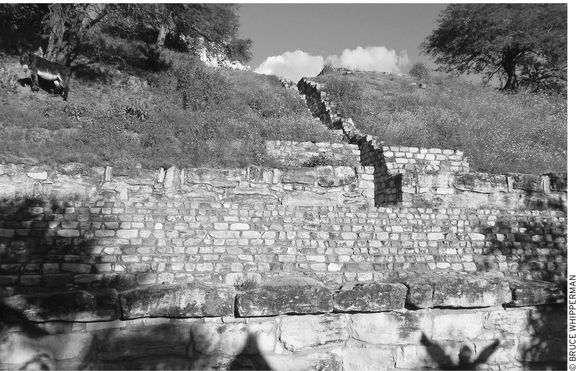

YAGUL ARCHAEOLOGICAL ZONE

The regal remains of Yagul (Zapotec for “Old Tree”; 45 km/28 mi east of Oaxaca City, just north of Hwy. 190, 10 A.M.–5 P.M. daily, $3) preside atop their volcanic hilltop. Although only 12 kilometers (7.5 mi) from Mitla and sharing architectural details, such as Mitla’s famous Greca fretwork, the size and complexity of its buildings suggest that Yagul was an independent city-state in its own right. Local folks call the present ruin the Pueblo Viejo (Old Town) and remember it as the forerunner of the present town of Tlacolula. Archaeological evidence, which indicates that Yagul was occupied for about a thousand years, at least until around A.D. 1100 or 1200, bears them out.

One of Yagul’s major claims to fame is its Palace of Six Patios, actually three nearly identical but separate complexes of two patios each. In each patio, rooms surround a central courtyard. The northerly patio of each complex is more private and probably was the residence, while the other, more open patio served administrative functions.

South of the palace sprawls Yagul’s huge ball court, the second largest in Mesoamerica, shaped in the characteristic Oaxaca I configuration. Southeast of the ball court is Patio 4, consisting of four mounds surrounding a courtyard. A boulder sculpted in the form of a frog lies at the base of the east mound. At the courtyard’s center, a tomb was excavated; descend and explore its three greca-style, fretwork-decorated chambers.

If it’s not too hot, gather your energy and climb to the hilltop above the parking lot for a fine view of the ruin and the entire Valley of Oaxaca. The name for this prominence—the Citadel—was probably accurately descriptive, for Yagul’s defenders long ago added rock walls to enhance the hilltop’s security.

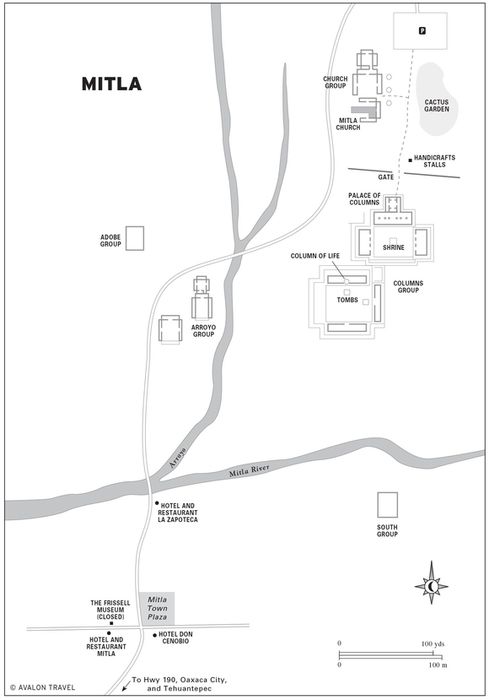

MITLA

MITLA

The ruins at Mitla (Hwy. 176, about 57 km/35 mi east of Oaxaca City, 8 A.M.–5 P.M. daily, $5) are a “must” for Valley of Oaxaca sightseers. Mitla (Liobaa in Zapotec, the “Place of the Dead”) flowered late, reaching a population of perhaps 10,000 during its apex around A.D. 1350. It remained occupied and in use for generations after the conquest.

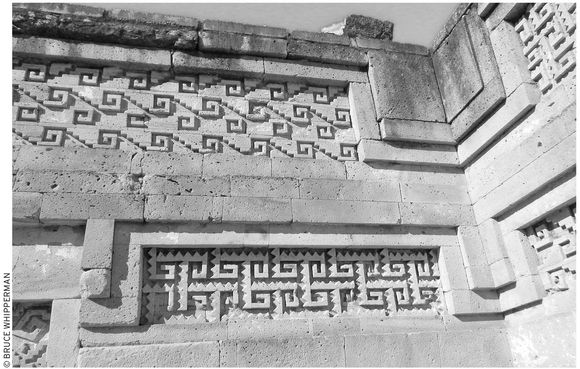

During Mitla’s heyday, several feudalistic, fortified city-states vied for power in the Valley of Oaxaca. Concurrently, Mixtec-speaking people arrived from the north, perhaps under pressure from Aztecs and others in central Mexico. Evidence suggests that these Mixtec groups, in interacting with the resident Zapotecs, created the unique architectural styles of late cities such as Yagul and Mitla. Archaeologists believe, for example, that the striking Greca (Grecian-style) frets that honeycomb Mitla facades are the result of Mixtec influence.

Exploring the Site

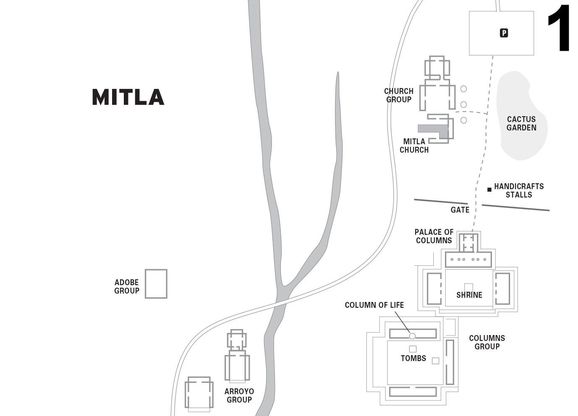

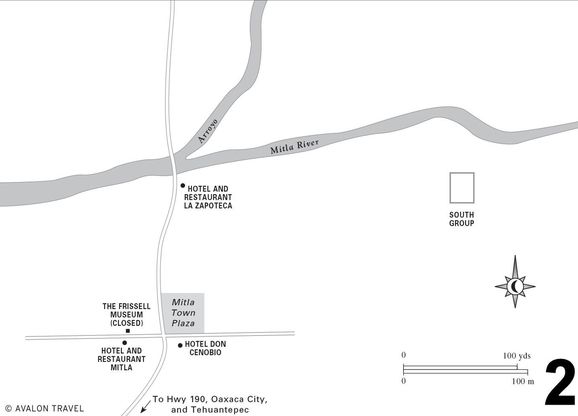

In a real sense, Mitla lives on. The ruins coincide with the present town of San Pablo Villa de Mitla, whose main church actually occupies the northernmost of five main groups of monumental ruins. Virtually anywhere archaeologists dig within the town they hit remains of the myriad ancient dwellings, plazas, and tombs that connected the still-visible landmarks.

Get there by forking left from main Oaxaca Highway 190 onto Highway 176. Continue about two miles to the Mitla town entrance, on the left. Head straight through town, cross a bridge, and, after about a mile, arrive at the site. Of the five ruins clusters, the best preserved is the fenced-in Columns Group. Its exploration requires about an hour. Three of the others—the Arroyo and Adobe Groups beyond an arroyo, and the South Group across the Mitla River—are rubbly, unreconstructed mounds. Evidence indicates the Adobe and South Groups were ceremonial compounds, while the Arroyo, Church, and Columns Groups were palaces.

Hundreds of thousands of pieces of Greca stone fretwork make up Mitla’s magnificent buildings.

The interesting Church Group (marked by the monumental columns that you pass first on your right after the parking lot) is on the far north side of the Palace of Columns. Builders used the original temple stones to erect the church here. Although the Church Group has suffered from past use by the local parish, it deserves a few minutes’ look around inside. It consists of a pair of regal courtyards, labeled A and B, adjacent to the triple red-domed 16th century church. You first enter courtyard B, enclosed by monumental stone-framed doorways. A passageway leads to smaller courtyard A, where you can see the fascinating remnants of the red hieroglyphic paintings of personages, name-dates, and glyphs that once covered its walls.

Back outside, on the main entrance path, continue past the tourist market and through the gate to the Columns Group. Inside, two large patios, joined at one corner, are each surrounded on three sides by elaborate apartments. A shrine occupies the center of the first patio. Just north of this stands the Palace of Columns, the most important of Mitla’s buildings. It sits atop a staircase, inaccurately reconstructed in 1901.

Inside, a file of six massive monolithic columns supported the roof. A narrow “escape” passage exits out the right rear side to a large patio enclosed by a continuous narrow room. The purely decorative Greca facades, which required around 100,000 cut stones for the Columns Group complex, decorate the walls. Remnants of the original red and white stucco that lustrously embellished the entire complex hide in niches and corners.

Walk south to the second patio, which has a similar layout. Here the main palace occupies the east side, where a passage descends to a tomb beneath the front staircase. Both this and another tomb, beneath the building at the north side of the patio, are intact, preserving their original crucifix shapes. (The guard, although he is not supposed to, may try to collect a tip for letting you descend.) No one knows for certain who and what were buried in these tombs, which were open and empty at the time of the conquest.

See THE MYSTERY OF MITLA’S FRISSELL MUSEUM

The second tomb is similar, except that it contains a stone pillar called the Column of Life; by embracing it, legend says, you will learn how many years you have left.

Fiesta del Apóstol de San Pablo

Mitla (pop. 15,000), although famous, is a quiet town where tranquility is disturbed only by occasional tourist buses along its dusty, sun-drenched main street. A major exception occurs during Mitla’s key fiesta, which centers on the town’s venerable 16th-century church, dedicated to San Pablo Apóstol (St. Paul the Apostle). If you plan your visit during the eight days climaxing around January 25 (or also around June 29, the day of St. Pablo and St. Pedro), you can join with the townsfolk as they celebrate their patrón with masses, processions, a feast, fireworks, jaripeo (bull roping and riding), and dancing.

Accommodations and Food

Stop for a refreshment at the homey Hotel and Restaurant Mitla (Benito Juárez 6, tel. 951/568-0112, cell tel. 044-951/115-5676, food 8 A.M.–7 P.M. daily; lodging $15 s, $22 d), domain of the sparkplug mother-daughter team of Teresa and Gloria González de Quero. Here you can enjoy Mexico as old-timers remember it, in a charmingly ramshackle hacienda-style farmhouse, where roosters crow, dogs snooze, and guests can have their seasonal fill of bananas, avocados, mandarins, and zapotes from a shady backyard huerta (orchard). Their 16 rooms vary. Most rooms in the upstairs tier—plain but clean (if you don’t look too hard), with the essentials, including hot water—are acceptably rustic.

Diagonally across the plaza from the museum is the shiny, four-star neo-colonial-style Don Cenobio Banquet Salon and Hotel (Benito Juárez 3, tel. 951/568-0330, fax 951/568-0050, informes@hoteldoncenobio.com, www.hoteldoncenobio.com, $70 d), with about 20 beautifully decorated rooms built around a large, inviting pool and grassy patio. Guests enjoy a wealth of facilities, including a restaurant and banquet hall for 500 people. Rooms come with air-conditioning, cable TV, queen and king-size beds, and much more. The only drawback to all of this is that they rent the place out to hundreds for conferences and parties quite often. Best to check by telephone before reserving an overnight.

Alternatively, about five blocks north, closer to the archaeological zone, try the family-run  Hotel and Restaurant La Zapoteca (5 de Febrero 12, tel. 951/568-0026, ivettsita_revelde@hotmail.com, food 8 A.M.–6 P.M. daily; lodging $15 s, $20 d, $27 t), on the right just before the Río Mitla bridge. The spic-and-span restaurant, praised by locals for “the best mole negro and chiles rellenos in Oaxaca,” is fine for meals, and the 20 clean, reasonably priced rooms, with hot water, in-house Internet, and parking, are good for an overnight.

Hotel and Restaurant La Zapoteca (5 de Febrero 12, tel. 951/568-0026, ivettsita_revelde@hotmail.com, food 8 A.M.–6 P.M. daily; lodging $15 s, $20 d, $27 t), on the right just before the Río Mitla bridge. The spic-and-span restaurant, praised by locals for “the best mole negro and chiles rellenos in Oaxaca,” is fine for meals, and the 20 clean, reasonably priced rooms, with hot water, in-house Internet, and parking, are good for an overnight.

Shopping

Instead of making handicrafts, Mitla people concentrate on selling them, mostly at the big handicrafts market adjacent to the archaeological zone parking lot. Here you can sample from a concentrated all-Oaxaca assortment, especially textiles: cotton huipiles, wool hangings and rugs, onyx animals and chess sets, fanciful alebrijes (wooden animals), and leather huaraches, purses, belts, and wallets.

Getting There

Bus travelers can get to Mitla from Oaxaca City by Fletes y Pasajes or Oaxaca-Istmo bus from the camionera central segunda clase. Drivers get there by forking left from main Oaxaca Highway 190, at the big Mitla sign, onto Highway 176. Continue about 3.2 kilometers (two mi) to the Mitla town entrance, on the left. Turn left, and head straight past the town plaza. Continue across the bridge over the (usually dry) Río Mitla, and after about 1.6 kilometers (one mi), arrive at the archaeological site.

HIERVE EL AGUA MINERAL SPRINGS

Although the name of this place translates as boiling water, the springs that seep from the side of the limestone mountain less than an hour’s drive east of Mitla aren’t hot. Instead, they are loaded with minerals. These minerals over time have built up into rock-hard deposits, forming great algae-painted slabs in level spots and, on steep slopes, accumulating into what appear to be grand frozen waterfalls. Note: A local community dispute has unfortunately led to periodic closures of the Hierve El Agua park. Before planning a visit, check at the Oaxaca state tourist information office (Av. Juárez 703, west side of El Llano park, tel. 951/516-0123, 8 A.M.–8 P.M. daily, info@aoaxaca.com, www.aoxaca.com, 8 A.M.–8 P.M. daily). You can also consult with a tour agency or guide, such as the excellent Juan Montes Lara (tel/fax 951/513-0126, cell 951/170-3239).

The Springs

Although Hierve El Agua (9 A.M.–6 P.M. daily, $2) may be crowded on weekends and holidays, you’ll probably have the place nearly to yourself on weekdays. The first thing you’ll see after passing the entrance gate is a lineup of snack and curio stalls at the cliff-side parking lot. A trail leads downhill to the main spring, which bubbles from the mountainside and trickles into a huge basin that the operators have dammed as a swimming pool. Bring your bathing suit.

Part of Hierve El Agua’s appeal is the panoramic view of mountain and valley. On a clear day, you can see the tremendous massif of Zempoatepetl (saym-poh-ah-TAY-pehtl), the grand holy mountain range of the Mixe people, rising above the eastern horizon.

From the ridge-top park, agile walkers can hike farther down the hill, following deposits curiously accumulated in the shape of miniature limestone dikes that trace the mineral water’s downhill path. Soon you’ll glimpse a towering limestone formation, like a giant petrified waterfall, appearing to ooze from the cliff downhill straight ahead, on the right.

Back uphill by the parking lot, operators have augmented the natural springs with a resort-style swimming pool, where, along with everyone else, you can frolic to your heart’s content.

Hikers can also enjoy following a sendero peatonal (footpath) that encircles the entire zone. Start your walk from the trailhead beyond the bungalows past the pool, or at the other end, at the cliff edge between the parking lot and the entrance gate. Your reward will be an approximately one-hour, self-guided tour, looping downhill past the springs and the great frozen rock cascades and featuring grand vistas of the gorgeous mountain and canyon scenery along the way.

The Hierve El Agua zone and surrounding country is habitat for a hardy dry-country palm you’ll probably see plenty of while strolling around. Lack of winter–spring moisture usually keeps the palms small, sometimes clustering in great wild gardens, appearing like regiments of desert dwarfs. Local people gather and weave their fronds into tenates (baskets), petates (mats), escobas (brooms), and more, which they sometimes sell in the stalls by the parking lot.

Accommodations and Food

The Hierve El Agua tourist  cabañas ecoturísticas have in the past provided the key for a restful one- or two-night stay. The several clean and well-maintained housekeeping bungalows, with shower-baths and hot water, rent for about $10 per person, or around $40 for up to six in a bungalow, with refrigerator, stove, and utensils. For information about cabaña reservations, contact the Oaxaca state tourist information office (Av. Juárez 703, west side of El Llano park, tel. 951/516-0123, 8 A.M.–8 P.M. daily, info@aoaxaca.com, www.aoxaca.com, 8 A.M.–8 P.M. daily).

cabañas ecoturísticas have in the past provided the key for a restful one- or two-night stay. The several clean and well-maintained housekeeping bungalows, with shower-baths and hot water, rent for about $10 per person, or around $40 for up to six in a bungalow, with refrigerator, stove, and utensils. For information about cabaña reservations, contact the Oaxaca state tourist information office (Av. Juárez 703, west side of El Llano park, tel. 951/516-0123, 8 A.M.–8 P.M. daily, info@aoaxaca.com, www.aoxaca.com, 8 A.M.–8 P.M. daily).

For food, you can bring and cook your own in your bungalow or rely upon the strictly local-style beans, carne asada (roast meat), tacos, tamales, and tortillas offered by the parking-lot food stalls. In any case, fruit and vegetable lovers should bring their own from Oaxaca City. Produce selection in local San Lorenzo village stores will most likely be minimal.

Getting There

Get there by riding an Ayutla-bound Fletes y Pasajes bus east out of either Oaxaca City (departing from camionera central segunda clase) or from Mitla on Highway 179 just east of town. Get off at the Hierve El Agua side road, about 18 kilometers (11 mi) past Mitla. Continue the additional eight kilometers (five mi) by taxi or the local bus marked San Lorenzo. At this writing, the road is open for cars and buses only to the edge of San Lorenzo village, from which you can walk or continue by taxi the additional mile to the Hierve El Agua entrance.

South Side: The Crafts Route

Travelers who venture into the Valley of Oaxaca’s long, south-pointing fingers, sometimes known as the Valleys of Zimatlán and Ocotlán, can discover a wealth of crafts, history, and architectural and scenic wonders. These are all accessible as day trips from Oaxaca City by car or combinations of bus and taxi. Most reachable are the renowned crafts villages of San Bartolo Coyotopec, San Martín Tilcajete, Santo Tomás Jalieza, and others along Highway 175, between the city and the colorful market town of Ocotlán (best to plan a visit to all on Friday, Ocotlán’s market day; start at Ocotlán early and work your way north back to Oaxaca City). Another day, you can either continue farther south, off the tourist track, to soak in the feast of sights at the big market in Ejutla, or fork southwest, via Highway 131 through Zimatlán, to the idyllic groves, crystal springs, and limestone caves hidden around San Sebastián de las Grutas.

SAN BARTOLO COYOTEPEC

SAN BARTOLO COYOTEPEC

San Bartolo Coyotepec (Hill of the Coyote), on Highway 175, 23 kilometers (14 mi) south of Oaxaca City, is famous for its pottery and its August 23–28 festival, Fiesta de San Bartolomé. During the fiesta, masked villagers costumed as half-man half-woman figures in tiaras, blond wigs, tin crowns, and velvet cloaks dance in honor of their patron.

The town’s black pottery, the renowned barro negro sold all over Mexico, is available at the signed Mercado de los Artesanias market on the right and at a number of cottage factory shops (watch for signs) off the highway, scattered along the left (east side) of Calle Juárez, marked by a big Doña Rosa sign. Doña Rosa, who passed away in 1980, pioneered the technique of crafting lovely, big, round jars without a potter’s wheel. With their local clay, Doña Rosa’s descendants and neighbor families regularly turn out acres of glistening black plates, pots, bowls, trees of life, and fetching animals for very reasonable prices (figure on about $20 for a pearly black three-gallon vase, and perhaps $2 for a cute little rabbit).

San Bartolo Museum

Across the highway from the town church, on the town plaza’s southern flank, stands the large, new Museo Estatal de Arte Popular (Plaza Principal, tel. 951/551-0036, 10 A.M.–6 P.M. Tues.–Sun., $4). Although the main event is a fine exposition of San Bartolo Coyotepec’s famed black pottery, the museum also exhibits a surprisingly innovative range of some of the best crafts that the Valley of Oaxaca offers. Besides Doña Rosa’s classic pearly-black examples, a host of other pieces—divine angels, scowling bandidos, fierce devils—reveal the remarkable talent of Doña Rosa’s generation of students and followers.

Cochineal Farm

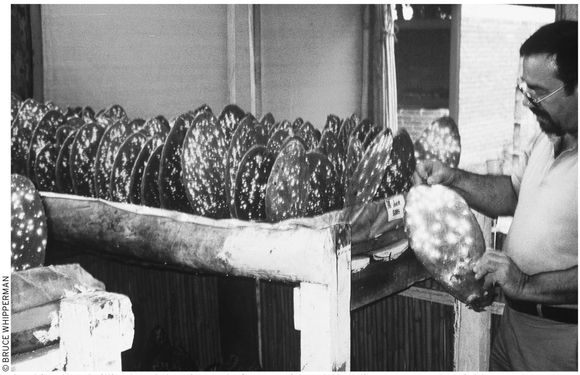

On your way either to or from San Bartolo Coyotepec and Ocotlán, you’re in for an unusual treat if you stop at the small demonstration cochineal farm and museum Rancho la Nopalera (Km 10.5 Carretera Oaxaca–Puerto Ángel, Calle Matamoros 100, tel. 951/551-0030, fax 951/551-0053, info@aztecacolor.com, www.aztecacolor.com, 9 A.M.–1 P.M. and 2–5 P.M., $3), a few blocks off the highway at San Bartolo Coyotepec.

The farm, officially called the Centro de Difusión del Conocimiento de la Grana Cochinilla y Colorantes Naturales, is the labor of love of retired chemical engineer Ignacio J. del Río Dueñas and his son-in-law, engineer Manuel Loera Fernández. They graciously welcome all visitors—schoolchildren, visiting scholars, neighbors, tourists—to their ranch for the purpose of breathing life into the ancient Oaxaca tradition of cochineal dye, the source of the bright reds in many of the Oaxaca weavings.

Many others besides Señores Dueñas and Fernández believe in cochineal and support its use as a natural dye. Its color, so intensely scarlet that it is sometimes known as the “blood of the nopal,” is produced from the bodies of the scale insect, Dactylopius coccus, that thrives on the thick leaves of the nopal (prickly pear) cactus, found all over Mexico and much of the western United States. Precisely because cochineal is a natural, non-synthetic product, it’s gaining favor as a food and cosmetic (lipstick) coloring. The modest cochineal crop that the farm produces requires the processing of about 600 nopal leaves for each kilogram of cochineal, which sells for about $200.

They (or an assistant) will be happy to show you around their cactus cultivation house and demonstrate how the insects are harvested, and explain their several interesting museum exhibits, which illustrate the history and uses of cochineal.

Get there by bus from the camionera central segunda clase in Oaxaca City, via regional buses Estrella del Valle, Oaxaca Pacifico, or Estrella Roja del Sureste, or more local Choferes del Sur or Halcón buses, which will let you off at the highway, where you can taxi or walk according to the following driver’s directions: By car, from Highway 175, about 7.5 kilometers (4.7 mi) south of the Oaxaca airport, turn right, southbound, at the small blue roadside sign (“El Museo Centro Reproducióa Grana Cochininilla”) at Calle Unión, at the northern, Oaxaca edge of San Bartolo Coyotepec village; after a few hundred yards westbound, on a dirt road, another sign directs you left to the rancho.

Cochineal, a brilliant red dye, is made from an insect that lives on nopal (prickly pear) cactus.

CRAFTS VILLAGES ON THE ROAD TO OCOTLÁN

Each of the three crafts villages not far north of Ocotlán has something unique to offer. In order to visit all of them, plus San Bartolo Coyotopec and Ocotlán, on Friday, you’ll need to get an early start. If you’re inclined to linger, it’s best to allow two days for your visit, with an overnight in Ocotlán. Under any circumstances, visit San Antonino Castillo Velasco on the same Friday that you visit Ocotlán, because it also has its tianguis (native market) on Friday. Two things to look for are the wonderful breads (in the morning, sold out by afternoon), fresh and yummy as you come into town, and the famous vestidos de San Antonino, sometimes known as “Oaxaca wedding dresses,” marked by their elaborately fancy and colorful animal and floral embroidery.

First stop for the vestidos de San Antonino should be the small Artesanías de Castillo Velasco (on the San Antonino entrance road, Av. Castillo Velalsco, on the right, two blocks from the highway, tel. 951/571-0623). Your hosts will be friendly Enrique Lucas G. and his wife Maria Luisa Amador H., who manufacture and offer lovely embroidered vestidos, blusas, and servilletas (dresses, blouses, and napkins), and much more. Their finest vestidos, elaborately adorned with fetchingly colorful floral and animal designs, sell for $100 and up. Besides the goods they display up front, they can show you much more, including men’s wedding shirts, from their rear storeroom.

For more embroidery options, a few women sell dresses and blouses in the regular market on Friday (turn left at the first block after the bread stalls). If you arrive and no one seems to be selling any dresses, mention vestidos de San Antonino, and someone will lead you to a woman who makes them. Alternatively, ask for friendly Rosa Canseco Godines (go-DEE-nays; Calle Guerrero 33, no phone), one of the local mae-stras of the craft. If she’s home, she’ll gladly show you examples of her beautiful work.

Bus passengers, take a taxi or walk 1.6 kilometers (one mi) from Ocotlán. Drivers, turn west at the San Antonino Castillo Velasco sign just at the northern (Oaxaca) edge of Ocotlán.

San Martín Tilcajete and Santo Tomás Jalieza

San Martín Tilcajete (teel-kah-HAY-tay; Hwy. 175, not far north of the Hwy. 131 fork), about 37 kilometers (21 mi) south of Oaxaca City, is a prime source of alebrijes, fanciful wooden creatures occupying the shelves of crafts stores the world over. Both it and Santo Tomás Jalieza (Hwy. 175, south of the Hwy. 131 fork), a mile or two farther south, can be visited as a pair on any day.

The label alebrije, a word of Arabic origin, implies something of indefinite form, and that certainly characterizes the fanciful animal figurines that a generation of Oaxaca woodcarvers has been crafting from soft copal wood. Dozens of factory-stores sprinkle San Martín Tilcajete. Start on the front main street, but also be sure to wander the back lanes and step into several cottage workshops, whose occupants will be happy to show you what they have and demonstrate how they make them. You’ll find lots more than funny animals. Artisans branched out to plants such as purple palm trees and yellow cacti. Some items, such as imaginatively painted jewel boxes and picture frames, are practical, while others, such as miniature sets of tables and chairs, are for kids 3–90. Find some of the most original examples at the back-street shop of Delfino Gutiérrez (Calle Reforma, tel. 951/524-9074), who specializes in free-form elephants, frogs, turtles, armadillos, and much more.

Santo Tomás Jalieza, on the other hand, is known as the town of embroidered cinturones (belts). Women townsfolk, virtually all of whom practice the craft, concentrate all of their selling in a single many-stalled market (Centro de Artesanias, Plaza Principal, no phone,9 A.M.–5 P.M. daily) in the middle of town. Step inside and you’ll be tempted not only by hundreds of hand-embroidered leather belts, but also by a wealth of lovely handloomed and embroidered purses, shawls, dresses, blouses, small backpacks, and much more. Furthermore, asking prices are very reasonable.

A couple of local restaurants received favorable reviews. Although it caters to the tourist crowd, the food is good and innovative at Restaurant Azucena (on the Tilcajete entrance road). On the other hand, for truly rustic, ranch-style ambience, complete with old wagon wheels, wooden picnic-style tables and plenty of savory barbeque, stop by Restaurant Huamuches (on the highway, by the Santo Tomás Jalieza entrance road).

OCOTLÁN

Your first stop in district capital Ocotlán (pop. 20,000, 42 km/26 mi south of Oaxaca) should probably be the interesting trio of family workshops (9 A.M.–6 P.M. daily) run by the Aguilar sisters, Irene, Guillermina, and Josefina. Watch for signs reading “Aguilar,” on the right, on the outskirts, about 0.4 kilometers (0.25 mi) on the Oaxaca side from the town plaza. Their creations include a host of charming figures in clay: vendors with big ripe strawberries, green and red cactus, goats in skirts, and bikini-clad blondes.

The main Ocotlán attraction (unless you’re lucky enough to arrive for the big fiesta on the third Sunday of May) is the huge Friday market. Beneath a riot of colored awnings, hordes of merchandise—much modern stuff, but also plenty of old-fashioned goodies—load a host of tables and street-laid mats. How about a saddle for your donkey? If not that, why not four or five turkeys, a goat, or perhaps half a dozen bags of hard-to-get wild medicinal plants? And be sure to pick up a kilo or two of cal (lime or quicklime) for soaking your corn. If you’re looking for lots of native costumes, you’ll have to head for the mountains, because few women (except for their ribbon-decorated braids) and virtually no men wear traje (traditional indigenous dress). You’ll hear plenty of Zapotec, however. At least half of the local people are native speakers.

Since markets are best in the morning, you should make Ocotlán your first Friday stop. Drivers could get there by heading straight south out of the city, arriving in Ocotlán by mid-morning. Spend a few hours, then begin your return in the early afternoon, stopping at the sprinkling of crafts villages along the road back to Oaxaca. Gasoline is available at the Pemex gasolinera, on the highway, on the north edge of Ocotlán.

Bus travelers could hold to a similar schedule by riding an early Autobuses Estrella del Valle, Autotransportes Oaxaca–Pacífico, or Choferes del Sur from the camionera central segunda clase, then returning, in steps, by bus, or more quickly by taxi, stopping at the crafts villages along the way.

Casa de Cultura Rudolfo Morales

During the 1980s and 1990s, Ocotlán came upon good times, largely due to the late Rudolfo Morales, the internationally celebrated but locally born artist who dedicated his fortune to improving his hometown. The Rudolfo Morales Foundation has been restoring churches and other public buildings, reforesting mountainsides, and funding self-help and educational projects all over Ocotlán and its surrounding district. The bright colors of the plaza-front presidencia municipal and the big church nearby result from the good works of Rudolfo Morales.

The Morales Foundation’s local efforts radiate from the Casa de Cultura Rudolfo Morales (Morelos 108, tel. 951/571-0198, 9 A.M.–2 P.M. and 5–8 P.M. Mon.–Fri., 9 A.M.–3 P.M. Sat.), in the yellow-painted mansion three doors north from the Ocotlán plaza’s northwest corner. In the Casa de Cultura’s graceful, patrician interior, the Morales family and staff manage the foundation’s affairs, teach art and computer classes, and sponsor community events.

The foundation staff welcomes visitors. For advance information, contact the foundation’s headquarters in Oaxaca City (Murguia 105, between Macedonio Alcalá and 5 de Mayo, tel. 951/514-2324 or 951/514-0910, galeria@artedeoaxaca.com, www.artedeoaxaca.com, 11 A.M.–3 P.M. and 5–8 P.M. Mon.–Sat.).

Templo de Santo Domingo

Local people celebrate Rudolfo Morales’s brilliant restoration of their beloved 16th-century Templo de Santo Domingo. Gold and silver from the infamous Santa Catarina Minas (mines), in the mountains east of Ocotlán, financed the church’s initial construction. When overwork and disease tragically decimated the local native population by around 1600, the mines were abandoned, and work on the church stopped. Although eventually completed over the succeeding three centuries, it had slipped into serious disrepair by the 1980s.

Fortunately, the Templo de Santo Domingo is now completely rebuilt, from its bright blue, yellow, and white facade to the baroque gold glitter of its nave ceiling. Inside on the right side, you’ll pass a pious Saint John the Baptist, with Mary Magdalene at his feet. Up front, above the main altar, a white-haired, bearded Creator reigns, resembling an indigenous Father Sun, with a halo of golden rays bursting from behind his head. Below him, Jesus hangs limply on the cross, flanked below by Mother Mary with a knife in her breast and St. John the Baptist lamenting at Jesus’s feet.

Walk to the nave’s south (right) side, to a gilded chapel dedicated to the Señor de la Sacristía (Lord of the Sacristy), the image above the altar. Also notice the adjacent oil painting of the Virgin of the Rosary, singular for her mestizo facial features. The Señor de la Sacristía is the object of community adoration in a festival of food, fireworks, processions, high masses, and dances climaxing on the third Sunday in May.

Practicalities

Free yourself of the Friday downtown crowd at the rustic-chic restaurant La Cabaña (Hwy. 175, tel. 951/571-0201, 8 A.M.–7 P.M. daily, $4–10), an open-air palapa by the gasolinera on the highway, at the north, Oaxaca, side of town.

If you decide to linger overnight in Ocotlán, the newish, clean, and modern Hotel Rey David (16 de Septiembre 248, tel. 951/571-1248, $13 s or d in one bed, $22 d or t in two beds) can accommodate you. The hotel offers about 20 comfortable, attractively decorated rooms. Find it on the south-side Highway 175 ingress-egress avenue, Avenida 16 de Septiembre, where it runs east–west, about three blocks east of the market and central plaza.

Do your money business at the Ocotlán Banamex (9 A.M.–4 P.M. Mon.–Fri.), with ATM, on the north side of the town plaza.

EJUTLA

Tour buses usually skip Ejutla de Crespo (pop. 20,000) because of its distance, about 59 kilometers (36 mi, one hour) from Oaxaca City. This is a pity, because Ejutla (ay-HOOT-lah) hides some surprises, not the least of which is its huge, colorful Thursday market. Folks troop in from country villages all over the huge Ejutla governmental district and farther to haggle over everything from hamacas (hammocks) and huaraches to radios and refrigerators. Moreover, Ejutla also offers accommodations at Hotel 6, the graceful hacienda-turned-hotel at the south edge of town.

Sights

Take a walk around Ejutla’s shady plaza to get your bearings. The portico-fronted presidencia municipal stands on the plaza’s south side, the market is on the north, and the big, proud Templo de la Natividad towers above the southeast corner. Sometime around 1750, the present church replaced the 16th-century original (which itself replaced a big pre-conquest Zapotec pyramid). Over the years, earthquakes took their toll; it was extensively restored around 1900.

Several large hieroglyph-decorated stone blocks built into the church’s walls attest to the fact that the entire town remains an unexplored archaeological zone. You can find more evidence of this about two blocks north and two blocks east of the church, near the corner of Calles Altimirano and 16 de Septiembre. A big house compound encloses what appears to be a small hill, which is actually a buried temple-topped pyramid. Look for the several hieroglyph-decorated pre-conquest monoliths that have been incorporated into modern walls.

Since the church is usually open, you might as well step into the cool interior and contemplate the town’s patron, the Virgin of the Nativity, presiding in front of the altar in what at first glance appears to be a bridal gown. In the lovely transept chapel on the right of the nave, you’ll see another image of the same patron. Local people celebrate both, with a big fiesta centering around December 8.

For something else interesting, step over to the presidencia municipal and look on the wall for Ejutla’s official escudo (coat of arms), which incorporates no arms at all. It’s a portrait in tile of a bean vine, encircling a view of the sun rising from behind a likeness of Cerro El Labrador, the town’s sacred mountain, towering in the east. A poem in praise of the “Sun, which rises here earlier than other lands…the source of life…without which there would be nothing” is included at the base of the escudo.

Practicalities

Another of Ejutla’s surprises is the  Hotel 6 (Km 61.5 Carretera Oaxaca–Puerto Ángel/ Hwy. 175, tel. 951/573-0350, $20 s or d in one bed, $30 d or t in two beds), “probably the best in North America,” claims the owner-operator, cordial former Olympic wrestler and civil engineer Mario E. Corres. A sign, which strikingly resembles Motel 6 signs all over the United States and Canada, draws you into the parking lot. You know you’re in for something unique when you pull up to an old hacienda as big as a baseball field, with a mini-jungle on one side, complete with a tree house and a swinging rope suspension bridge.

Hotel 6 (Km 61.5 Carretera Oaxaca–Puerto Ángel/ Hwy. 175, tel. 951/573-0350, $20 s or d in one bed, $30 d or t in two beds), “probably the best in North America,” claims the owner-operator, cordial former Olympic wrestler and civil engineer Mario E. Corres. A sign, which strikingly resembles Motel 6 signs all over the United States and Canada, draws you into the parking lot. You know you’re in for something unique when you pull up to an old hacienda as big as a baseball field, with a mini-jungle on one side, complete with a tree house and a swinging rope suspension bridge.

The Hotel 6 in Ejutla is more impressive than its ho-hum name suggests.

Inside, you’ll find everything completely in order, from three spreading courtyards and a spacious pool, to two big function rooms and a grand living room, dining room, and spotless, shining, old-fashioned kitchen. The climax to all this is Señor Corres’s museum, which includes his family tree and which he gladly explains to visitors (in Spanish, of course).

The 14 rooms, which after everything else seem an afterthought, are plain but clean. Some are more inviting than others. Take a look at two or three, small and large, before choosing. If the weather’s warm, you’ll need a fan, which some rooms have. This hotel offers all this plus parking, hot-water shower-baths, and an elegantly homey dining room.

You’ll encounter most of Ejutla’s services during your stroll around town—most of the available stores and institutions are right on or near the plaza. Starting at the presidencia municipal, on the south and moving clockwise, at the plaza-front eatery Taquería Mary (8 A.M.–7 P.M. daily, $2–6), at the southwest plaza corner, a squad of hardworking teenage girls serve hearty country food.

For pizza and hamburgers, go to Restaurant Rulis (roo-LEES; 8:30 A.M.–10 P.M. Mon.–Sat., noon–10 P.M. Sun.). To get there, walk a block west (downhill) from Taquería Mary, to Díaz, then turn left and continue, passing the Banamex bank (9 A.M.–5 P.M. Mon.–Fri.), for a block and a half.

Alternatively, for fresh and home-cooked food on the plaza’s north side, visit the market (8 A.M.–6 P.M. daily) where permanent fondas (eateries) serve plenty of hearty breakfasts, soups, and stews, and stalls offer mounds of luscious fruit and veggies.

Continuing east, uphill at the street corner past the market, find the huarachería La Principal (tel. 951/573-0717, 9 A.M.–7 P.M. Mon.–Sat.) with a huge assortment of footwear, some still made onsite by the owner’s daughter. One short block behind that (north) is the Clínica San Gabriel (tel. 951/573-0244), with a gynecologist and a general practitioner–surgeon on call 24 hours a day. If you need a farmacia, you have your choice of either the Santa Fe (9 A.M.–9 P.M. daily), on the plaza’s northeast corner, or the Farmacia Liliana (pharmacy 9 A.M.–9 P.M. daily; doctor 4–8 P.M. Mon.–Fri.) with general practicioner Doctora Concepción Carballido, a block east of the plaza, next to the church. Gasoline is available at the highway Pemex gasolinera at the north edge of town.

DOWN HIGHWAY 131

Zimatlán