THE MIXTECA

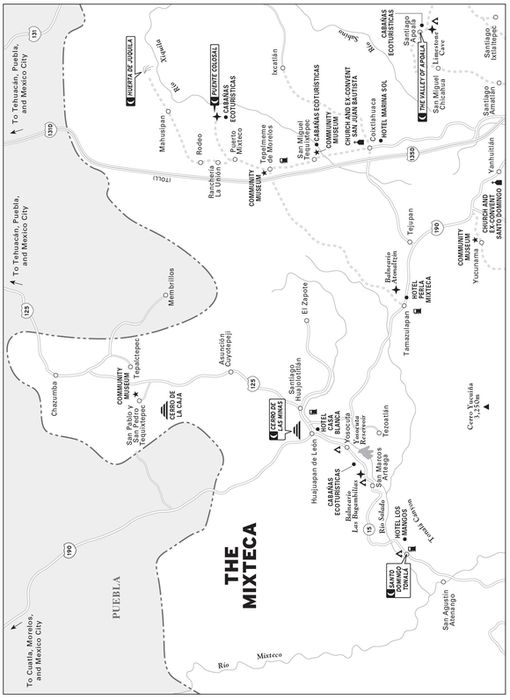

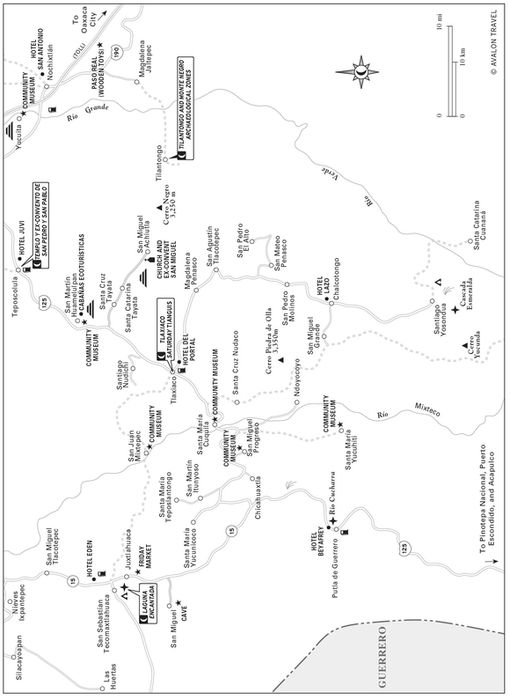

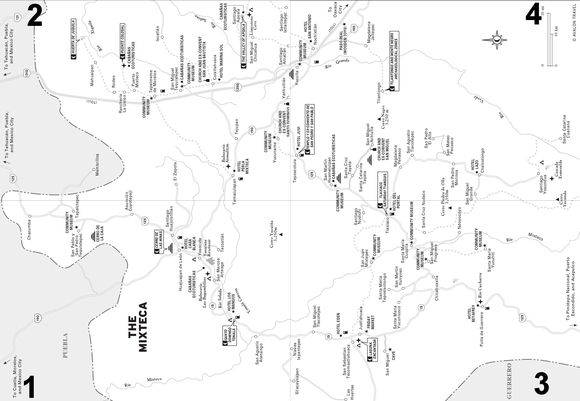

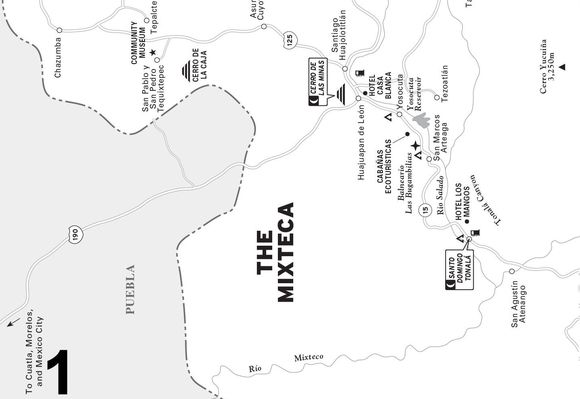

The homeland of the Mixtecs, Oaxaca’s “People of the Clouds,” spreads over an immense domain encompassing the state’s entire northwest, stretching northward from the tropical Pacific coast over the high, cool pine-tufted Sierra to the warm, dry “Land of the Sun” along Oaxaca’s northern border. The Mixteca’s vastness and diversity have led Oaxacans to visualize it as three distinct sub-regions: Mixteca Alta, Mixteca Baja, and Mixteca de la Costa. These labels reflect the geographical realities of the Mixteca’s alta (high) and baja (low) mountains and the tropical Pacific costa (coastal plain and foothills).

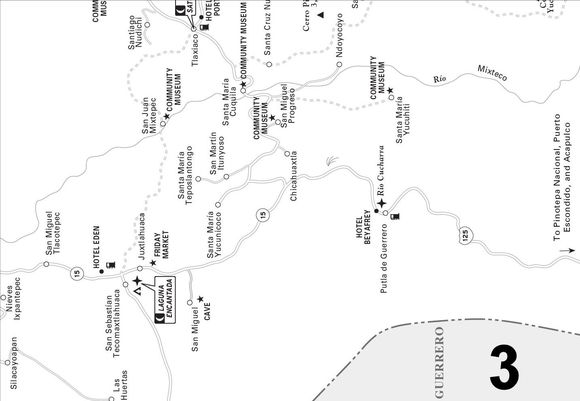

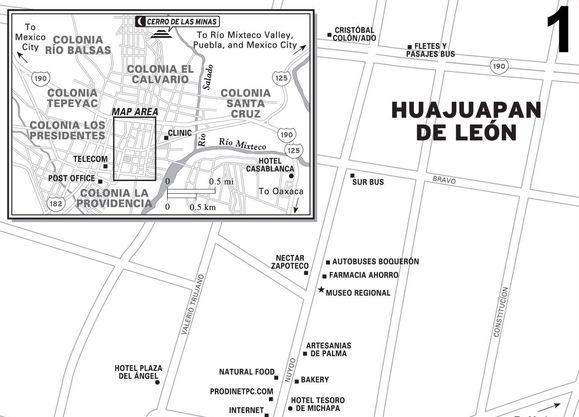

The Mixteca Alta comprises the Mixteca’s highest, coolest country—all or part of the governmental districts of Nochixtlán, Coixtlahuaca, Teposcolula, and Tlaxiaco. The Mixteca Baja includes, on the other hand, the warm, dry districts of Huajuapan, Silacayoapan, and parts of Juxtlahuaca along Oaxaca’s northern frontier. The Mixteca de la Costa lies south of all this, encompassing the tropical coastal districts of Putla and Jamiltepec on Oaxaca’s southwest border.

This chapter traces a counterclockwise circle route through the Mixteca, northwest from Oaxaca City. First, we arrive in Nochixtlán, scarcely an hour from Oaxaca City, and use it as a base for exploring the hidden delights of the southern Mixteca Alta. Next, the route continues north through country renowned for its exquisite and monumental Dominican churches, then on to the warm, sunny Mixteca Baja country around Huajuapan de León. There, our journey curves through the scenic back door to the Mixteca Alta—the cool, verdant roof of Oaxaca.

HIGHLIGHTS

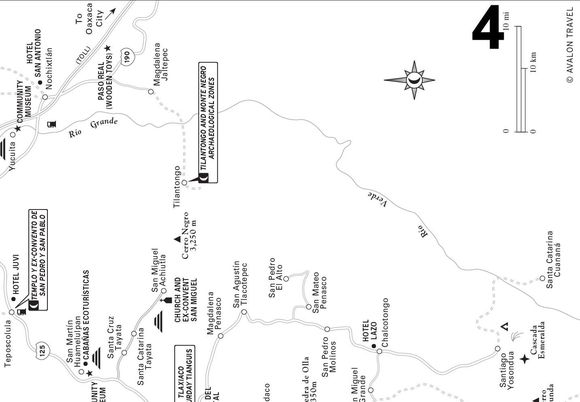

Tilantongo and Monte Negro Archaeological Zones: The ancient capital of the Mixteca and nearby Monte Negro, with ruins dating back to 500 B.C., make a memorable one-day excursion (

Tilantongo and Monte Negro Archaeological Zones: The ancient capital of the Mixteca and nearby Monte Negro, with ruins dating back to 500 B.C., make a memorable one-day excursion ( Tilantongo and Monte Negro Archaeological Zones).

Tilantongo and Monte Negro Archaeological Zones).

The Valley of Apoala: This bucolic, spring-fed, mountain-rimmed Oaxacan Shangri-La, replete with scenery and legends, deserves at least an overnight (

The Valley of Apoala: This bucolic, spring-fed, mountain-rimmed Oaxacan Shangri-La, replete with scenery and legends, deserves at least an overnight ( THE VALLEY OF APOALA).

THE VALLEY OF APOALA).

Templo y Ex-Convento de San Pedro y San Pablo: The newly restored gargantuan Capilla Abierta (Open Chapel), big enough for 10,000 acolytes, crowned the Dominican padres architectural efforts in Oaxaca (

Templo y Ex-Convento de San Pedro y San Pablo: The newly restored gargantuan Capilla Abierta (Open Chapel), big enough for 10,000 acolytes, crowned the Dominican padres architectural efforts in Oaxaca ( Templo y Ex-Convento de San Pedro y San Pablo).

Templo y Ex-Convento de San Pedro y San Pablo).

Puente Colosal and Huerta de Juquila: Scramble a mile downhill into a hidden box canyon and explore one of the world’s tallest natural bridges, decorated by giant, yet-to-be-deciphered Mixtec petroglyphs (

Puente Colosal and Huerta de Juquila: Scramble a mile downhill into a hidden box canyon and explore one of the world’s tallest natural bridges, decorated by giant, yet-to-be-deciphered Mixtec petroglyphs ( Puente Colosal and Huerta de Juquila).

Puente Colosal and Huerta de Juquila).

Cerro de las Minas Archaeological Zone: A high point of your Mixteca visit will most likely be the chance to climb to the top of the regal pyramids and stroll the broad stately plazas of this archaeological zone (

Cerro de las Minas Archaeological Zone: A high point of your Mixteca visit will most likely be the chance to climb to the top of the regal pyramids and stroll the broad stately plazas of this archaeological zone ( Cerro de las Minas Archaeological Zone).

Cerro de las Minas Archaeological Zone).

Santo Domingo Tonalá: This village is worth a visit, both for the 16th-century Templo de Santo Domingo and the lovely cypress grove behind it (

Santo Domingo Tonalá: This village is worth a visit, both for the 16th-century Templo de Santo Domingo and the lovely cypress grove behind it ( Santo Domingo Tonalá).

Santo Domingo Tonalá).

Laguna Encantada: This legendary spring-fed lagoon is deep, cold, and crystal-clear emerald green. It’s set at the foot of a towering mountain with picture-perfect gnarled ahuehuete cypresses inhabiting its banks (

Laguna Encantada: This legendary spring-fed lagoon is deep, cold, and crystal-clear emerald green. It’s set at the foot of a towering mountain with picture-perfect gnarled ahuehuete cypresses inhabiting its banks ( Laguna Encantada).

Laguna Encantada).

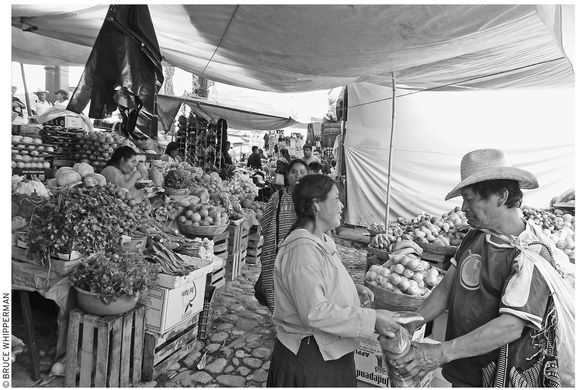

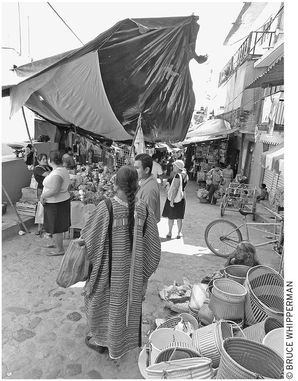

Tlaxiaco Saturday Tianguis: This native market, with its winding, awning-draped stalls of scarlet tomatoes, deep green cucumbers, bright yellow calabazas (gourds), lilies, roses, and marigolds, may be Oaxaca’s most colorful (

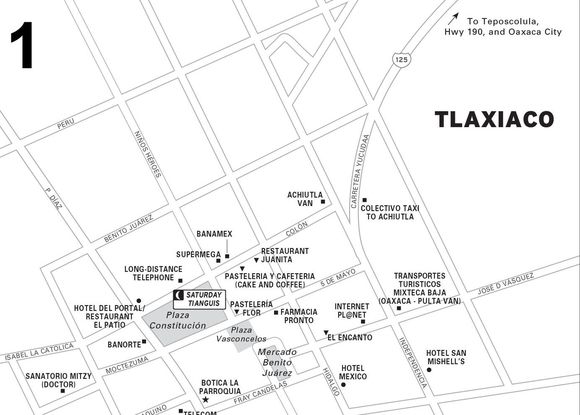

Tlaxiaco Saturday Tianguis: This native market, with its winding, awning-draped stalls of scarlet tomatoes, deep green cucumbers, bright yellow calabazas (gourds), lilies, roses, and marigolds, may be Oaxaca’s most colorful ( Tlaxiaco Saturday Tianguis).

Tlaxiaco Saturday Tianguis).

LOOK FOR  TO FIND RECOMMENDED SIGHTS, ACTIVITIES, DINING, AND LODGING.

TO FIND RECOMMENDED SIGHTS, ACTIVITIES, DINING, AND LODGING.

PLANNING YOUR TIME

The Mixteca is a large and fascinating region, rich in history and natural wonders, quickly accessible by tour, bus, or car from Oaxaca City. Your interests, of course, will show you how to use your time. If you have only a day, you can get a quick glimpse of the Mixteca on a day trip, visiting the grand restored 16th-century Dominican churches at Yanhuitlán and Teposcolula and returning to Oaxaca City in the afternoon. If you add a day for a Friday overnight in Tlaxiaco, you could soak in the sights and sounds of the big, colorful Tlaxiaco Saturday tianguis (native town market) before returning back to Oaxaca City.

Add two days to the above and you’ll have time en route to Yanhuitlán for a rewarding two-day side-trip from Nochixtlán for a hotel or camping overnight in the lovely, rustic Valley of Apoala. Here you can soak in Apoala’s tranquil, bucolic ambience while exploring the limestone Cave of the Serpent, the towering canyon of the Two Colossal Rocks, and the Tail of the Serpent waterfall.

With a week to spend, you could enjoy a grand circle tour of the Mixteca. It would be best to synchronize your trip with the vibrant markets (Fri. in Juxtlahuaca, Sat. in Tlaxiaco) along the way. You can do this by heading north from Oaxaca City on Monday, over-nighting in Apoala, then continuing northeast for an overnight or two in Huajuapan, capital of the Land of the Sun, in the Mixteca Baja. Here you’ll find a charmingly refined city around a lovely central plaza, dotted with comfortable hotels and good restaurants. The town’s sights could begin with the market and continue to the monumental pyramids of the Cerro de las Minas Archaeological Zone north of town. A rewarding day trip out of Huajuapan would include the lovely green Valley of the Río Mixteco and a visit to the pilgrimage town of San Pablo and San Pedro Tequixtepec and its community museum that highlights the fascinating, but as yet untranslated, Ñuiñe glyphs.

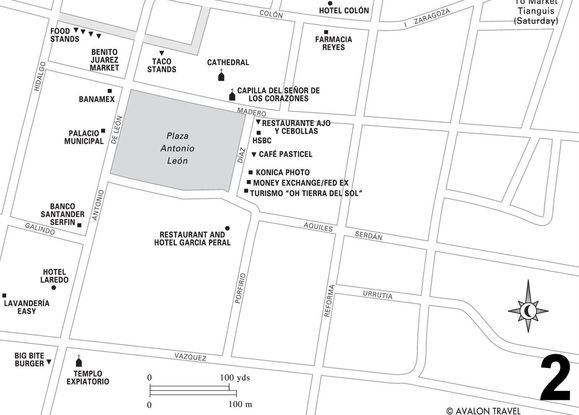

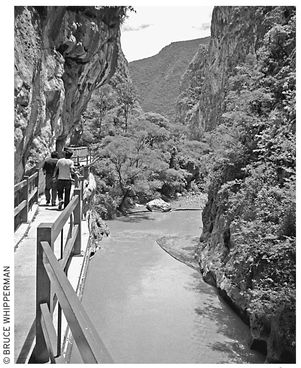

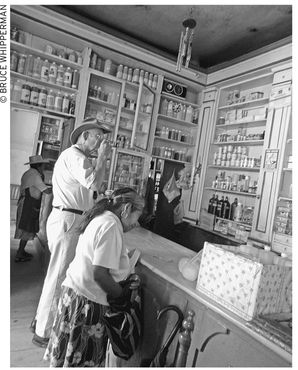

On Thursday, continue your tour by heading south to Santo Domingo Tonalá for a visit to the town’s great grove of ancient sabino trees and a walk into the nearby Boqueron (Big Mouth) of the spectacular canyon of the Río Mixteco. Continue south for an overnight at Juxtlahuaca; on Friday, stroll the fascinatingly rich native market and marvel at the emerald-green Laguna Encantada spring-fed lake. Spend the night in Tlaxiaco, and on Saturday take in the grand market, the cathedral, and the unmissable Botica la Parroquia antique pharmacy.

On Sunday, return back to Oaxaca City, with stops in Teposcolula and Yanhuitlán.

the Saturday tianguis (market) at Tlaxiaco

Northwest from Oaxaca City

NOCHIXTLÁN

Nochixtlán (noh-chees-TLAN, pop. 11,000), busy capital of the governmental district of Nochixtlán, is interesting for its colorful market and festivals and especially as a jumping-off point for exploring the wonders of the idyllic mountain valley of Apoala and the remains of the ancient Mixtec kingdoms of Tilantongo and Yucuita.

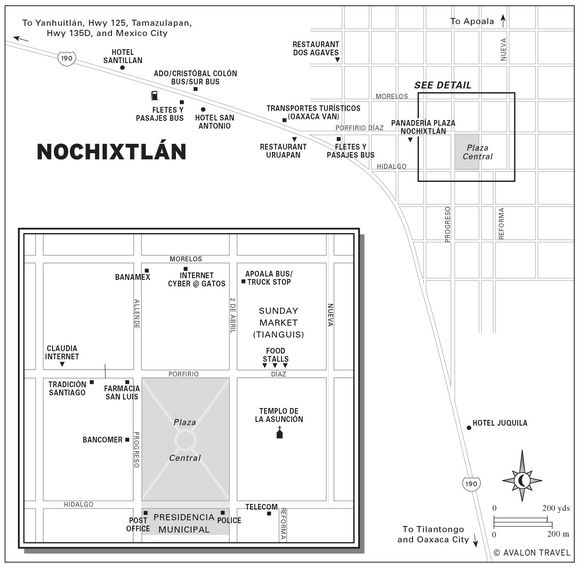

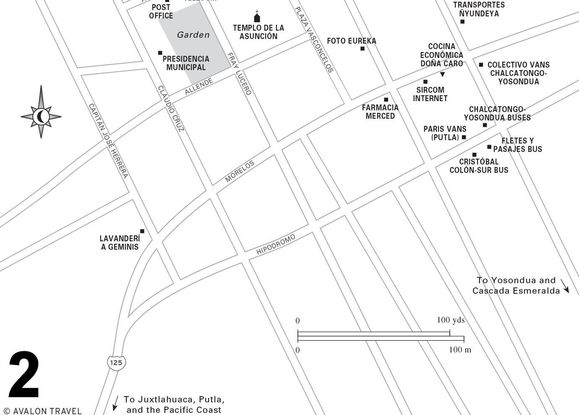

Sights

Nochixtlán town itself spreads out from its plaza, which is directly accessible from Highway 190, from the Oaxaca side by north–south street Calle Progreso and, from the adjacent, Tamazulapan side, by east–west Calle Porfirio Díaz. The streets intersect at the northwest corner of the central plaza. From there, you can admire the distinguished 19th-century twin-towered Templo de La Asunción rising on the plaza’s opposite side. Adjacent, to the right of the church, the presidencia municipal spreads for a block along Calle Hidalgo. At the plaza’s northeast side is the big market, which expands into a much larger tianguis on Sunday, when campesinos from all over northwest Oaxaca crowd in to peruse, haggle, and choose from a small mountain of merchandise.

The major patronal fiesta, celebrating Santa María de La Asunción, customarily runs August 1–21, climaxing around August 15. Merrymaking includes calendas (religious processions), marmotas (giant dancing effigies), mascaritas (dancing men dressed as women), nearly continuous fireworks, a blaringly loud public dance, and a carnival of food, games, and rides that brightens the entire central plaza.

Accommodations

The town’s three recommendable hotels are all on Highway 190, which curves past the edge of town.

For room for parking and a green inner patio, check out the loosely run but family-friendly Hotel Santillan (Porfirio Díaz 88, tel./fax 951/522-0351, norbertpcl@hotmail.com, $20 s or d, $27 d in two beds, $29 t), on the highway’s west (Tamazulapan) side, convenient for drivers and RVers. The motel-style rooms are arranged in an L-shaped, two-story tier around a spacious inner parking lot, with kiddie pool and patio garden. Additional amenities include a volleyball/basketball court and a pair of shady picnic palapas. Upper rooms, probably the best choice, are plainly furnished, but light. All come with hot-water shower-baths, parking, and a family-run restaurant, as well as proximity (half a block west) to the Omnibus Cristóbal Colón–Sur bus station. (Details, however, are not the family’s strong point. Inspect your room to see if all is in order and repaired before moving in.)

Right across from the main bus station, check out the brand-new Hotel San Antonio (Porfirio Díaz 112, no phone, $20–40 s or d). The 25 semi-deluxe rooms, invitingly furnished in beige-tone bedspreads and drapes, with shiny hot-water bathrooms and spacious modern-standard wash basins and commodes, are stacked in three stories above the bottom-floor parking garage. More expensive rooms come with king-size beds and whirlpool tubs.

On the diagonally opposite, Oaxaca, side of town, find the newish Hotel Juquila (Hwy. 190, Km 1, tel. 951/522-0581, $26 s or d in one bed, $32 d or t in two beds) on the highway, about 0.8 kilometers (0.5 mi) from the center of town, a few doors from the ADO bus stop. The hotel’s name comes from the owner’s devotion to the Virgin of Juquila, for whom he keeps a candle burning in front of a picture of the Virgin on the hotel front desk. Upstairs, the rooms are sparely decorated but very clean. Many are dark, however. Ask for one with mas luz (more light). Rooms all come with TV, hot-water showers, and a restaurant downstairs. If you’re sensitive to noise, come prepared with ear plugs; the passing trucks and buses may be a problem here.

Food

Nochixtlán offers a sprinkling of budget meal and bakery options. For wholesome (if they’re hot) country-style meals, go to the fondas (food stalls) in the market, on the north side of the plaza.

In the evenings the action spreads to the market streetfront, across from the church, where a line-up of stalls does big business serving a small mountain of tacos, tortas, quesadillas, and especially the Oaxaca specialty, tlayudas: giant pizza-sized crisp tortillas loaded with everything from beans and cheese to spicy chorizo sausage, cabbage, boiled eggs, and more ($3–6).

Freshly baked offerings are plentiful at Panadería Plaza (Porfirio Díaz, no phone, 7 A.M.–9:30 P.M. daily), a block and a half west of the plaza.

Nochixtlán’s restaurant of choice is Dos Agaves (local cell tel. 044-951/160-4399, 8 A.M.–8 P.M.daily, comida corrida $2.50). Although breakfast is fine here, they specialize in hearty four-course comidas corrida (set lunch; for example, fresh strawberry punch, rice, cream of carrot soup, and scrumptious meat balls in sauce). Find them on the west side of downtown. From the highway, walk east along Porfirio Díaz a block, turn left and go one block to Morelos and continue a fraction, to Dos Agaves (which looks like a rustic cowboy bunkhouse) on the left.

Alternatively, try Restaurant Uruapan (southwest corner of Porfirio Díaz and Hwy. 190, tel. 951/522-0495, 8 A.M.–9:30 P.M. daily, $3–5). Offerings include especially good Mexican-style breakfasts with fruit; a hearty afternoon four-course comida with tasty entrées, such as guisado de res (savory beef stew), and soup, rice, and dessert included; and à la carte omelets, tacos, quesadillas, tamales, and much more for supper.

Information and Services

Find the correo (tel. 951/522-0309, 8 A.M.–4:30 P.M. Mon.–Fri., 8 A.M.–noon Sat.) at the plaza’s southwest corner, west end of the presidencia municipal. Skip uphill east, half a block past the presidencia municipal, to telecomunicaciones (corner of Hidalgo and Reforma, tel. 951/522-0053, 9 A.M.–3 P.M. Mon.–Fri.).

For economical local or long-distance telephone access, buy a widely available Ladatel telephone card and use it in one of the several downtown street telephones. Otherwise, use the long-distance public phone and also connect to the Internet, at Claudia’s restaurant (Porfirio Díaz, tel. 951/522-0190, 9 A.M.–11 P.M. daily). Find it on the north side of Porfirio Díaz, a block west of the plaza.

Stock up with pesos at Bancomer (tel. 951/522-0154, 8:30 A.M.–4 P.M. Mon.–Fri.), in the middle of the plaza’s west side, with a 24-hour ATM.

A number of attractive all-Oaxaca handicrafts are for sale at the small Tradición Santiago (Porfirio Díaz 49, tel. 951/522-0294, 9 A.M.–9 P.M. daily). Offerings include fetching embroidered huipiles from remote source villages (such as Yalalag and Tehuacán), genuine homegrown Oaxaca mescal, and the famous green pottery from Atzompa.

Furthermore, beside the toll expressway between Nochixtlán at Km 209, about 16 kilometers (10 mi) past the Huitzo toll gate, watch for the bright toys beside the road. A close look reveals a charming treasury of handmade wooden toys, from windmills and angels to trucks and tractors. They’re made by the local members of Paso Real Toy cooperative (8 A.M.–8 P.M., toys $2–10).

Simple over-the-counter remedies and prescriptions are available at the big well-stocked drugstore, Farmacia San Luis (tel. 951/522-0484, 7 A.M.–11:30 P.M. daily) at the plaza’s northwest corner.

As for doctors, you can visit the Centro de Especialidades (Melchor Ocampo 10, tel. 951/522-0594, 9 A.M.–7 P.M. Mon.–Sat.) of José Manuel Sosa Bolanos, M.D.

For police and fire emergencies, dial tel. 951/522-0430, or go to the policía municipal, at their plaza-front station, at the east end (across from the church) of the presidencia municipal.

Getting There and Away

Several long-distance bus lines serve Nochixtlán. Luxury and first-class Autobuses del Oriente (ADO), first-class Omnibus Cristóbal Colón (OCC), and second-class Sur (operating jointly out of their west-side station on Porfirio Díaz, Hwy. 190, tel. 951/522-0387) provide broad service southeast with Oaxaca City; northwest both along Highway 190, with the Mixteca Baja (Tamazulapan, Coixtlahuaca, Huajuapan), and along the autopista 135D, continuing to Puebla, Veracruz, and Mexico City Tapo and Tasqueña terminals; and west with Teposcolula, Tlaxiaco, Juxtlahuaca, Putla, and intermediate points in the Mixteca Alta.

Additionally, second-class Fletes y Pasajes (Porfirio Díaz, corner of Hwy. 190, tel. 951/522-0585) offers connections northwest with Mexico City via Tehuacán and Puebla and southeast, with Oaxaca.

Enterprising Transportes Turísticos de Nochixtlán (Porfirio Díaz 72, tel. 951/522-0503, 6 A.M.–9 P.M. daily, $15), on the west-side highway, offers fast and frequent Suburban van rides to and from Oaxaca City. In Oaxaca City, contact them downtown (Galeana 222, tel. 951/514-0525). They also rent Suburban station wagons for $15 per hour; negotiate for a cheaper daily rate. This would be especially handy for a family or group visit to Apoala. Drivers can cover the 80 kilometers (50 mi) from Oaxaca City in an easy hour via the cuota autopista. If you want to save the approximately $6 car toll (more for big RVs and trailers), figure about two hours via the winding old Highway 190 libre (free) route.

YUCUITA, TILANTONGO, AND MONTE NEGRO: FORGOTTEN KINGDOMS

Yucuita

Yucuita (pop. 500) was once far more important than it is today. It started as a village around 1400 B.C., then grew into a town of 3,000 inhabitants around 200 B.C., about the same time that early Monte Albán was flourishing. Later, by A.D. 200, it lost population and became a center secondary to Yucuñudahui, several miles north.

The claim to fame of drowsy, present-day Yucuita, about eight kilometers (five mi) northwest of Nochixtlán, is that it sits atop the old Yucuita, one of the Mixteca’s largest and most important (but barely explored) archaeological zones. City officials received donations of so many artifacts that they had to organize a small community museum to hold them. Local volunteers offer, when possible, to open it up for any interested visitor. (Drop by the presidencia municipal before noon, preferably on a weekday, early enough to arrange a visit.)

Inside, your guide might point out (in Spanish) interesting aspects of the collection (mostly pottery): 2,000-year-old turkey eggs; human-effigy censers and bowls; 1,000-year-old manos and metates (stone rollers and grind stones), just like those used today; and a platoon of small, toy-like figurines. The most intriguing piece in the museum is a carved stone relief of a seated figure, appearing Olmec-influenced, holding what looks like a bunch of flowers. Maybe this is related to the meaning of Yucuita, which in Mixtec means Hill of Flowers.

Perhaps your guide will have time to show you around town. In any case, be sure to explore the Yucuita archaeological zone by climbing the reconstructed steps (fast becoming part of the ruins themselves) next to the paved through-town highway, about a 1.6 kilometers (one mi) south of the town plaza. If you’re agile and adventurous, you can enter the site via a dry tunnel that runs about 30 meters (100 ft) from the entrance steps to a big opening and then continues another 30 meters to a final opening, where you can lift yourself out. (Warning: Carry a flashlight and a stick to spot and ward off pests, such as scorpions and rattlesnakes, in time to back out. If this scares you, don’t try the tunnel.)

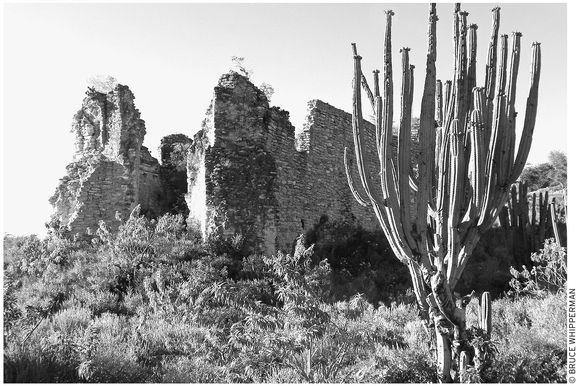

Regal, columned palace-houses speak of Monte Negro’s distinguished past as a commercial and ceremonial center.

Aboveground, what you mostly see is an expansive corn and bean field littered with the stones from the walls and foundations of ancient Yucuita. Pottery shards are common—the colored ones especially stand out. A couple hundred feet to the south of the tunnel opening, inspect the partly reconstructed temple mound with an unfinished stairway and four belowground chambers. Archaeologists say that the entire site, elongated along a north–south axis, is riddled with buried structures, whose remains extend beyond the high hill (the original Hill of Flowers) to the north.

If possible, coordinate your Yucuita visit with the Fiesta de San Juan Bautista (June 22–24), when the ordinarily sleepy town is at its exciting best. Many folks return home to Yucuita from all over Mexico and the United States for reunions and to once again enjoy country delicacies, dance the favorite old dances, honor San Juan with grand floral processions, and thrill to rockets bursting and showering stars overhead. (If you can’t come in June, then come for the equally popular fiesta to honor the beloved Virgin of Guadalupe around December 18.)

GETTING THERE

Reach Yucuita via minibus from Calle Porfirio Díaz, in front of the Nochixtlán market, or along Highway 190, northwest side of town. Drivers: Head northwest on Highway 190 from Nochixtlán. Continue straight ahead along the old Highway 190, Huajuapan direction (not the cuota expressway to Puebla and Mexico City). Pass the gas station and continue for about three kilometers (two mi) until you see a signed right turnoff to Yucuita. Southbound drivers: On old Highway 190, watch for the signed left turnoff to Yucuita before Nochixtlán. If you reach the Pemex gasolinera, before the cuota expressway, you have gone too far. Turn around and look for the signed Yucuita right turnoff.

Tilantongo and Monte Negro Archaeological Zones

Tilantongo and Monte Negro Archaeological Zones

The Tilantongo archaeological zone is the town itself (pop. 4,000), which sits smack on top of storied ancient Tilantongo. In the old days, around A.D. 1050, Tilantongo was the virtual capital of the Mixteca, ruled by the ruthless but renowned Mixtec king 8-Deer of the Tiger Claws. Carved stones built into the Tilantongo town church wall attest to Tilantongo’s former glory.

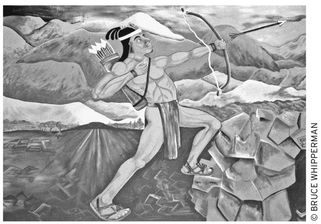

The town government commissioned a mural, now on the outside wall of the presidencia municipal, which dramatically portrays the legendary Mixtec Flechador del Sol (Bowman of the Sun) and copies of pages from the Codex Nuttall, a pre-conquest document in blazing color that records glorious events in Mixtec pre-conquest history. See if you can identify 8-Deer (hint: look for the very pictorial 8-Deer hieroglyph) on one of the Codex Nuttall pages reproduced in the mural.

At least as important and more rewarding to explore is the much older Monte Negro archaeological zone atop the towering, oak-studded Monte Negro (Black Mountain), visible high above Tilantongo. A graveled road, passable by ordinary cars, easier for high-clearance trucks or jeep-like vehicles, allows access to the top in about an hour. If you have no wheels, you may be able to get a taxi driver to take you up there. If not, perhaps someone with a car might accept the job. Fit hikers should allow about three hours for the eight-kilometer (five mi) uphill climb, two hours for lunch and exploring the site, and two hours for the return. Take plenty of water, wear a hat and strong shoes, and use a strong sunscreen. You must obtain permission from authorities at the presidencia municipal (tel. 951/510-4970), who require that a local guide (whom they will furnish, fee about $10, plus lunch) accompany you.

Monte Negro flourished about the same time as early Monte Albán, 500–0 B.C. The 150-acre hilltop zone is replete with ruined columned temples, raised residences of the elite (complete with inner patios), ceremonial plazas, and a ball court, all aligned along a single avenue. Monte Negro’s long, north–south orientation is reminiscent of Monte Albán, although its structures are not as grand. For reasons unknown, Monte Negro, like Monte Albán, was abandoned during the Late Urban Stage, around A.D. 800. All that remains are the old city’s stone remnants, while its descendants still husband the land you see in all directions from the breezy hilltop. Some of what surrounds you is thick oak forest; other parts are fertile terraced corn and bean fields; while much, in mute testimony to the passage of time, is tragically eroded.

GETTING THERE

Bus passengers can go by the Tilantongo–Nochixtlán bus, which makes the trip about three times a day from Calle Porfirio Díaz, in front of the Nochixtlán market. Drivers: Follow Highway 190 (old libre route) to the Jaltepec paved turnoff about 13 kilometers (eight mi) southeast (Oaxaca City direction) from Nochixtlán. Mark your odometer at the turnoff. The road is paved to the Jaltepec plaza (8.2 km/5.1 mi), where you turn right. The road is dirt and gravel, often rough, after that. Follow the Tilantongo (or Teozocoalco) signs. Turn left at a church (17.7 km/10.8 mi) at Morelos villages, and right after a river bridge (23.8 km/14.8 mi). (Note: The riverfront at the bridge would make a lovely picnic or overnight camping spot, beneath the shade of the grand old sabino, especially during the dry, clear-water fall–spring–summer season.) You’ll pull up to the Tilantongo plaza after 29 kilometers (18 mi) and about an hour of steady, bumpy driving.

THE VALLEY OF APOALA

THE VALLEY OF APOALA

It’s hard to describe the valley of Apoala, tucked in the mountains north of Nochixtlán, with anything less than superlatives. A fertile, terraced, green vale nestles beneath towering cliffs far from the noise, smoke, and clutter of city life. Apoala is no less than a Oaxacan Shangri-La—a farming community replete with charming country sights and sounds, such as log-cabin houses, men plowing the field with oxen, women sitting and chatting as they weave palm-leaf sombreros, dogs barking, and burros braying faintly in the warm dusk. The spring-fed river assures good crops; people, consequently, are relatively well-off and content to remain on the land. They have few cars, almost no TVs, and few, if any, telephones.

What’s more, the local folks are ready for visitors. I arrived at a string stretched curiously across the narrow gravel entrance road. I realized that there must be a good reason for this, so I stopped, instead of just barging in. The explanation is that the local folks want to tell you about the wonders of their sylvan valley. The entrance fee is about $5 per group, which includes a guide (an absolute must).

Exploring Apoala

The tour, which takes about two hours, begins at the Cave of Serpent, translated from the local Mixtec dialect, which all townsfolk speak. Just before the cave, you pass a crystalline spring welling up from the base of a towering cliff. This spring supplies a large part of the Río Apoala flow, which ripples and meanders down the valley and which folks use to keep their fields green. Another major (and more constant) part of its flow wells up from beneath a huge rock across the creek, below the cave entrance.

Entering the cave, be careful not to bump your head as you descend the tight, downhill entrance hollow. Immediately, you see why your guide is so important: He carries a large battery and light to illuminate the way. In the first of the cave’s two galleries, bats flutter overhead as your guide reveals various stalactites and then flashes on the subterranean river gurgling from an underground dark lagoon, unknown in extent. What is known, however, is that the water from the lagoon arrives at the springs at Tamazulapan, more than 50 kilometers (30 mi) away. Someone long ago dropped some oranges into the cave lagoon in Apoala, and they bobbed to the surface later in Tamazulapan.

See THE LEGEND OF THE FLECHA DEL SOL (ARROW OF THE SUN)

In the other cave gallery (careful, the access is steep and slippery), the light focuses on a towering stalagmite capped by a bishop’s visage, complete with clerical miter and long beard. On the other side, you see a stalactite shaped exactly like a human leg.

After the cave, you’ll head up-valley between a pair of cliffs that tower vertically at least 150 meters (500 ft). If you speak Spanish or have someone to interpret, be sure to ask the guide to explain the names and uses of the plantas medicinales (medicinal plants) along the path. Every plant, even the notorious mala mujer (bad woman), which your guide can point out, seems to have some use.

Soon, above and to your left, you’ll see the towering 600-meter (2,000 ft) burnt-yellow rampart, La Peña Donde Murió El Aguila con Dos Cabezas (The Rock Where the Eagle with Two Heads Died). No kidding. It seems that, once upon a time, a huge eagle that actually had two heads lived in one of the many caves in the rock face. The problem was, it was killing too many lambs, so one day one of the villagers shot it. The Eagle with Two Heads, however, lives on in the community memory of Apoalans.

Finally, after about 20 minutes of walking and wondering at the natural monuments towering around you, the climax arrives: a narrow, river-cut breach in the canyon, like some antediluvian giant had cut a thin slice through a mountain of butter. The slice remains, between a pair of vertical rock walls called Las Dos Peñas Colosales (The Two Colossal Rocks).

The grand finale, down-valley about 1.6 kilometers (one mi), is the waterfall Cola del Serpiente (The Serpent’s Tail). You walk down a steep forested trail that looks out on a gorgeous mountain and valley panorama. At the bottom, the Río Apoala, having already tumbled hundreds of feet, pauses for spells in several pools, and finally plummets nearly 90 meters (300 ft) in a graceful arc to an emerald green pool surrounded by a misty, natural stone amphitheater.

Local Guides

If you’d like a guide for more local exploring, contact very knowledgeable and personable Leopoldo Guzman Alvarado, who, if he can’t guide you himself, will find someone who can, such as youthful Oswaldo López Jiménez. To contact them in advance, leave a message via the Apoala satellite phone: Dial long distance 01-55/5151-9154.

Accommodations and Food

Camping ($15 per day per group, pay at the cabaña ecoturística), by self-contained RV or tent, would be superb here. The community has set aside a choice grassy riverside spot, across the river from the cave at the upper end of town—heavenly for a few days of camping. Clear, pristine spring water, perfect for drinking, wells up at the foot of the cliff at the road’s end nearby. Wilderness campers can choose among more isolated spots upstream, ripe for wildlife-viewing. (Swimming, however, is only permitted downstream from the village, preferably at the foot of the waterfall. Always swim with a bathing suit on; skinny-dipping is locally disapproved.)

Non-campers shouldn’t miss staying in Apoala’s fine cabaña ecoturística ($15 pp), where you probably first met your guide. This is a model of Oaxaca’s improved second-generation government-built, locally-managed tourist accommodation. Besides three very clean and comfortable modern-standard rooms with either one or two double beds, it features a light, spacious solarium–sitting room–snack café, serving water, beer, and sodas, as well as breakfast, lunch, and early supper.

Guests can also eat their own food there. If you do, bring your own food, since Apoala has only one basic store, the Conasupo (9 A.M.–4 P.M. Mon.–Tues. and Thurs.–Fri.), with groceries only, no fruit or veggies. In an emergency, go to the very modest abarrotes Juana (grocery), behind the cabaña ecoturística, which furnishes basic meals and a few food supplies.

Overnight reservations are strongly recommended. Reserve directly with Apoala through their satellite phone connection (in Mexico long-distance tel. 01-55/5151-9154; in Mexico City, simply dial as a local call, tel. 5151-9154; from the U.S. tel. 011-52-55/5151-9154). Alternatively, you can get information and lodging reservations in Oaxaca City at the government tourism office (703 Av. Juáraz, tel. 951/516-0123, www.aoaxaca.com).

Getting There and Away

Like Shangri-La, Apoala isn’t easy to get to. Colectivo passengers have it easiest. The Apoala community provides an Apoala-marked colectivo ($5), which leaves from Calle 2 de Abril near the corner of Morelos, Nochixtlán (a block north of the plaza’s northeast corner). At this writing, it departs at noon Wednesday–Monday, arriving in Apoala around 3 P.M. It departs Apoala for Nochixtlán on the same days at around 6:30 A.M. Check locally for the Apoala colectivo schedule with stores or bus or truck drivers parked along Calle 2 de Abril. To check in advance, call the Apoala satellite phone number: Dial long distance 01-55/5151-9154. Otherwise, taxis ($18) and passenger trucks ($4–6) make the same trip hourly until about 5 P.M. from the same spot.

For drivers, the 42-kilometer (26 mi) rough dirt and gravel road is a challenge, especially in an ordinary passenger car. The route heads north from downtown Nochixtlán; turn left from Calle Porfirio Díaz (the street that borders the plaza’s north side) at the street just past (east) the market. Follow the road signs all the way.

Trucks, vans, and VW Beetles carry nearly all the traffic to Apoala, although a careful, experienced driver in an ordinary car could usually complete the trip with minimal damage. The ideal vehicle (which I’ve driven three times) would be a high-clearance Jeep-like truck or sport-utility vehicle, with tough tires. Four-wheel-drive, not necessary under dry conditions, is mandatory in rain. Under dry conditions, lighter, maneuverable campers and RVs could make it; large rigs would be marginal at best, because of the narrow, steep, rocky, and winding descent into Apoala Canyon.

Dominican Route South

Of the four missionary orders—Franciscans, Jesuits, Augustinians, and Dominicans—who established an important presence in New Spain, the Dominicans were dominant in Oaxaca. Hernán Cortés had barely begun to resurrect Mexico City from the rubble of old Tenochtitlán when a stream of Dominican padres was heading southeast to Oaxaca. For the next three centuries, until republican reforms forced many of them from Mexico during the late 1800s, the padres earnestly pursued the spiritual thrust of Spain’s two-pronged “God and Gold” mission in the New World. The Dominicans converted, educated, protected, and advocated for Oaxaca’s native peoples, often in conflict with brutal and greedy Spanish soldiers and colonists.

The Dominicans’ legacy remains vibrant to this day. More than 90 percent of Oaxacans consider themselves Catholics, and lovely old Dominican ex-convent/churches decorate the Oaxacan countryside. Some of these outstanding venerable monuments—notably at Yanhuitlán, Teposcolula, Tlaxiaco, and Coixtlahuaca—grace the Mixteca Alta, not far from the modern town of Tamazulapan, making it a natural base for extended exploration of what has become known as Oaxaca’s Dominican route. The Dominican route’s more isolated (but very intriguing) northern section—north and west of Tamazulapan—is usually explored via the autopista that connects with Coixtlahuaca, from Nochixtlán and Oaxaca City.

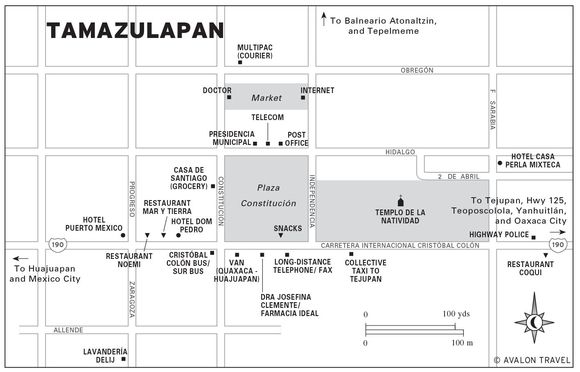

TAMAZULAPAN AND VICINITY

Tamazulapan (tah-mah-soo-LAH-pahn, pop. 5,000), partly by virtue of its crossroads position on the National Highway 190, has eclipsed its more venerable, but isolated, neighbor towns and become the major service and business center for the Teposcolula district. You know you’re in Tamazulapan immediately as you pass its town plaza, which proudly displays a semicircular columned monument right by the highway in honor of Benito Juárez, “Benemérito de las Américas.” Upon reflection, nothing seems more appropriate directly on the Pan-American Highway.

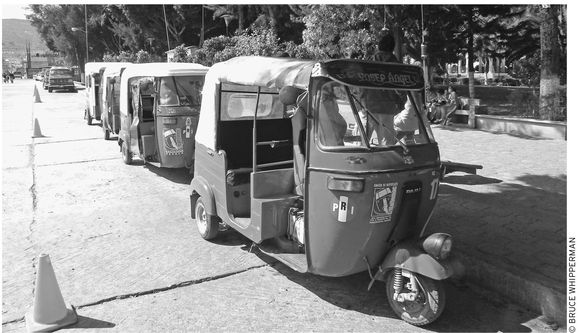

Moto-taxis wait for customers in Tamazulapan.

Sights

As you stand on the edge of the highway (locally known as Carretera Cristóbal Colón) looking at the Benito Juárez monument, you’ll be facing approximately north. The noble, portaled presidencia municipal will appear straight ahead behind the square, the Plaza Constitución. To your right, beyond the storefronts along plaza-front Calle Independencia, rise the ruddy cupolas of the 18th-century Dominican Templo de la Natividad. Bordering the plaza on your left are the stores and services along Calle Constitución.

Walk a block east and step into the cool calm of the venerable Dominican church which, although large and harmoniously decorated, is not architecturally comparable to the masterpieces at Coixtlahuaca, Yanhuitlán, and Teposcolula. What is unique, however, are the two images on the altar, both illuminated. The bottom figure (in the coffin) is an unusually small image of Jesus on the cross. This figure (known as the Señor Tres de Mayo), is locally paraded and celebrated, along with food, games, dancing, and a basketball tournament, in a festival culminating on May 3, El Día de la Cruz.

Above the figure of Jesus is the larger, but still petite town patron, La Virgen de la Natividad (The Virgin of the Nativity), dressed in blue and white, whom townsfolk celebrate in a fiesta culminating on September 8. As you retrace your steps, exiting through the church garden, you pass the old Dominican convent on the left, now mostly converted to storefronts facing the highway.

Tamazulapan townsfolk love their resort, Balneario Atonaltzin (9 A.M.–6 P.M. daily, adults $3, kids $2). You’ll see why if you drive, taxi, or walk the 2.5 kilometers (1.5 mi) north along the road to Tepelmeme (east plaza-front Calle Independencia). Soon after a bridge, you’ll see the balneario (resort) on the right. This spot would be a merely typical Sunday family bathing resort if it were not for its crystalline, naturally disinfected sulfurous springs. The waters gurgle up, cool and clear, from a pair of sources in the rocky cliff behind the Olympian double-size pool—a lap swimmer’s delight (except on Sundays and holidays, when it’s filled with frolicking families). Besides the big main pool, there are two kiddie pools, a local-style restaurant, volleyball, dressing areas, a few picnic tables, and campsites. The balneario invites overnight tent-camping and self-contained RV parking, for about $10 per car, including the general admission fee.

Two lesser-known but nevertheless interesting spots are the nearby ojo de agua swimming hole and the Xatachio archaeological zone. The ojo de agua (literally, eye of water), a general term for a natural spring or source of water, is about 90 meters (300 ft) back from the balneario (resort) toward town, on the right, below the creek bridge. Step toward the ruined building on the right and you’ll see the creek cascading into a big blue pool. Before the Balneario Atonaltzin was built, this was a popular swimming hole. Today, the water appears much less than pure, since it’s mostly used by families for washing clothes. Although the steep riverbank near the bridge is nonnegotiable, you can get down to the water via a path to the right around the ruined building, through the brush, up some stone steps, and down again to the creek.

The unexcavated Xatachio archaeological zone (shah-TAH-shioh) is accessible via the dirt side road on the left, just past the Balneario Atonaltzin. You’ll first spot the zone as a brush-covered hill (actually a former ceremonial pyramid) about 0.8 kilometers (0.5 mi) away on the left. Note: Do not try to explore the site on your own. The site lies on communal land, and people are rightly suspicious of possible artifact looters. Go to the presidencia municipal on the plaza and ask for permission (preferably through a local spokesperson, such as the owner or manager of your hotel); offer to pay someone (approximately $15) to act as a guide for a couple of hours. Any artifacts you might stumble upon are legally the joint property of the INAH (National Institute of Archaeology and History) and the local community.

Tejupan

If you have time, stop for a few minutes for a look inside the relatively humble, but nevertheless worthy, Dominican church and ex-convent at Tejupan (Tay-HOO-pahn) in the Tamazulapan valley, a 15-minute drive east (Oaxaca City direction) from Tamazulapan. Tejupan is a sleepy farming town, basking in its past glory, visibly represented by its noble, multi-portaled palacio municipal and the distinguished 17th-century Dominican Templo y Ex-Convento de Santiago Apóstol, across the street. Memorable inside the church is the pretty pink transept chapel, left side, dedicated to the Virgin of Guadalupe. The restored ex-convent section stands to the right of the church front entrance.

Get to Tejupan by bus, taxi, or car via the signed side road off Highway 190 about 11 kilometers (seven mi) southeast of Tamazulapan, or about 13 kilometers (eight mi) northwest of the Highway 190–Highway 125 junction northwest of Yanhuitlán.

Accommodations

Of Tamazulapan’s acceptable hotels, most prominent is the four-story Hotel Dom Pedro (Cristóbal Colón 24, tel./fax 953/533-0736, $14 s or d in one bed, $16 d in two beds, $18 t), a few doors north of the plaza. The 25 plain but clean upstairs rooms (no elevator) come with toilets and hot-water showers, TV, and parking, but no phone except the long-distance phone at the hotel desk. Credit cards are not accepted.

Although Hotel Puerto Mexico (Cristóbal Colón 12, tel. 953/533-0044, $19 s or d, $22 t), a few doors farther west, appears humdrum from the outside, guests enjoy an inviting tropical patio blooming with leafy banana trees. Rooms are clean and carpeted but have the almost universal Mexican small-town bare bulb hanging from the middle of the ceiling. Bring your own clip-on lampshade. Amenities include hot-water showers, parking, TV, and a pretty fair restaurant downstairs, but no phones. Credit cards are accepted.

The star of Tamazulapan hotels is the deluxe, newish  Hotel Casa Perla Mixteca (Calle 2 de Abril 3, tel./fax 953/533-0280, toll-free Mex. tel. 800/717-3956, $25 s, $28 d, and $33 t). A major plus here is the hotel’s quiet location, removed from the noisy highway truck traffic. Take your pick of 10 designer-decorated rooms, with rustically lovely tile floors, handwoven bedspreads, reading lamps, and shiny bathrooms with hot-water showers.

Hotel Casa Perla Mixteca (Calle 2 de Abril 3, tel./fax 953/533-0280, toll-free Mex. tel. 800/717-3956, $25 s, $28 d, and $33 t). A major plus here is the hotel’s quiet location, removed from the noisy highway truck traffic. Take your pick of 10 designer-decorated rooms, with rustically lovely tile floors, handwoven bedspreads, reading lamps, and shiny bathrooms with hot-water showers.

Food

For inexpensive prepared food, try the fondas (food stalls) inside the market and the nighttime taco stands or one of the several sit-down snack bars along the highway by the plaza.

As for restaurants, although the Hotel Puerto Mexico offers breakfast, lunch, and dinner, you might do better by walking a few steps west to  Restaurant Noemi (Cristóbal Colón 16, tel. 953/533-0595, 8 A.M.–11 P.M. daily, $2–7) between Hotel Puerto Mexico and Hotel Dom Pedro. The grandmotherly owner puts out Mexican home-style breakfasts, lunches, and suppers, including savory café de la olla (pot-brewed coffee, with cinnamon).

Restaurant Noemi (Cristóbal Colón 16, tel. 953/533-0595, 8 A.M.–11 P.M. daily, $2–7) between Hotel Puerto Mexico and Hotel Dom Pedro. The grandmotherly owner puts out Mexican home-style breakfasts, lunches, and suppers, including savory café de la olla (pot-brewed coffee, with cinnamon).

Another good choice is Restaurant Mar y Tierra (Cristóbal Colón 20, tel. 953/533-0045, 8 A.M.–10 P.M. daily, $4–12), between Hotel Dom Pedro and Restaurant Noemi. In a relaxingly airy patio location, patrons select from a long menu of breakfasts, soups, salads, pastas, seafood, and meat and suppers of Mexican specialties. They also serve a selection of good beers and wines from their bar.

Alternatively, check out the clean, highway-front Restaurant Coqui (KOH-kee; Cristóbal Colón 57, tel. 953/533-0109, 7 A.M.–9 P.M. daily), a block and a half east from the plaza. Although she’ll cook nearly anything you want, the hard-working owner is best at Oaxacan country delicacies, such as chiles rellenos, enchiladas tasajos (beef enchiladas), and Oaxacan tamales, covered with plenty of mole negro. (At this writing, however, her asking breakfast prices for scrambled eggs, fruit salad, ordinary coffee, and orange juice have doubled.)

Shopping

Get groceries, fruit, and vegetables at either the town market behind the presidencia, or at one of the plaza-front abarroterías (grocery stores), such as west plaza-front Casa de Santiago (Constitucion 6, tel. 953/533-0015, 8:30 A.M.–3:30 P.M. and 4:30–9:30 P.M. daily).

The market, especially during the big Wednesday tianguis, can be a good spot for local indigenous handicrafts shopping. Items might include pottery and palm-leaf woven goods such as tenates (tump-line baskets), petates (mats), and soft woven Panama hat–like sombreros.

Services

Tamazulapan provides a number of basic services along the blocks near the plaza. At this writing, there is neither bank nor ATM, so make sure to arrive with a supply of pesos (from banks in Nochixtlán, Tlaxiaco, or Huajuapan) or U.S. dollars that you may be able to exchange in local stores or at your hotel.

For public telephone, money orders, and fax, find the telecomunicaciones (a block north along Independencia, at corner of Obregón, tel. 953/533-0113, 9 A.M.–3:30 P.M. Mon.–Fri., 9 A.M.–1 P.M. Sat.) behind the presidencia. For stamps and sending mail, walk a few doors farther west along Obregón to the correo (Obregón, 8 A.M.–4:30 P.M. Mon.–Fri., 9 A.M.–1 P.M. Sat.). Half a block farther along Obregón, you can send a fast, secure mailing via courier service Multipac (Obregón 2, 9 A.M.–3 P.M. Mon.–Fri., 9 A.M.–noon Sat.).

For telephone service, go to the larga distancia across the highway from the plaza, or one of the three or four Ladatel card-operated public phones sprinkled along the highway and near the plaza. Answer your email at the Internet store (across from the plaza, tel. 953/5330694, 9 A.M.–11 P.M. daily).

At least two doctors near the plaza offer consultations and medicines. Choose either Dra. Josefina Clemente at her Farmacia Ideal (on the highway directly opposite the plaza, tel. 953/533-0224; pharmacy: 8 A.M.–9 P.M. Mon.–Sat.; consultations: 4–8 P.M. Mon.–Fri.); or Dr. Fidel A. Cruz Ramírez (a block and a half north from the highway, on the west Constitución side of the market; no phone; consultations: 9 A.M.–3 P.M., 5–9 P.M. Mon.–Fri.).

For a police emergency, contact either the Delegación de Transito highway police (half a block east of the plaza, on the same side as the highway, tel. 953/533-0472, on duty 24 hours); or the municipal police (at the presidencia municipal, tel. 953/533-0017).

Get your laundry done at handy Lavandería Delij (on Zaragoza, 9 A.M.–8 P.M. Mon.–Sat.), a block and a half south (uphill) from the Hotel Puerto Mexico on the highway.

Getting There and Away

Bus lines Omnibus Cristóbal Colón and Sur (both across from the plaza, tel. 953/533-0699) operate jointly out of their highway-front station. Their buses connect southeast with Oaxaca City via Nochixtlán; northwest via Huajuapan and Cuautla (Morelos), with Mexico City (Tapo); and south with Teposcolula, Tlaxiaco, and Juxtlahuaca, where you can transfer to a bus headed for Pinotepa Nacional on the Pacific coast.

Good paved roads connect Tamazulapan with all the important Mixteca and Oaxaca destinations: southeast, via Highway 190, 133 kilometers (84 mi), two hours, with Oaxaca City; northwest, 41 kilometers (25 mi), 45 minutes, with Huajuapan; north, by paved (but potholed) secondary road via Tejupan, 35 kilometers (22 mi), 45 minutes, with Coixtlahuaca; and south via Highway 190–Highway 125, 35 kilometers (22 mi), 45 minutes, with Teposcolula.

Frequent (10 per day) Transportes Atolzín vans (cell tel. 044/117-8800) connect southeast with Oaxaca City, and northwest with Huajuapan. Check for departures at their small office across the highway from the plaza’s southwest corner.

Servicios Turísticos Teposcolula vans connect south with Mixteca destinations of Teposcolula and Tlaxiaco, and west with Huajuapan. They stop for passengers on the highway, by the plaza.

TEPOSCOLULA

Although smaller in population than Tamazulapan, Teposcolula (pop. 2,000) continues to outrank it as district capital, a distinction it gained way back in 1740. Its history, however, reaches back much further. When the Spanish arrived in the 1520s, they found well-established Mixtec towns on the hillsides above a beautiful lake-filled valley. They drained the lake for farmland and moved the population down to Teposcolula’s present location. Abiding by common practice, the Spanish kept the Mixtec name, Teposcolula (Place Surrounded by Springs), tacking on the Catholic patronal title San Pedro y San Pablo. This produced a name so long that practically no one refers to the official San Pedro y San Pablo Teposcolula. People, however, still remember the old pre-conquest settlements on the hillsides. The old palace and temple foundations still stand, as El Fortín (The Fort) on the uphill slope behind the town and Pueblo Viejo (Old Town) on the pine-clad hilltop across the valley.

Teposcolula’s central plaza is quiet most of the time.

Orient yourself by standing (or imagining you’re standing) on the sidewalk on the through-town highway, facing the tree-shaded town plaza. North will be straight ahead, toward the cartoon-bright, repainted presidencia municipal on the far side of the plaza. The main streets are 20 de Noviembre (the highway), Madero (along the plaza’s left, west side), and Iturbide (along the plaza’s right, east side). Diagonally on your left stands the renowned Templo y Ex-Convento de San Pedro y San Pablo.

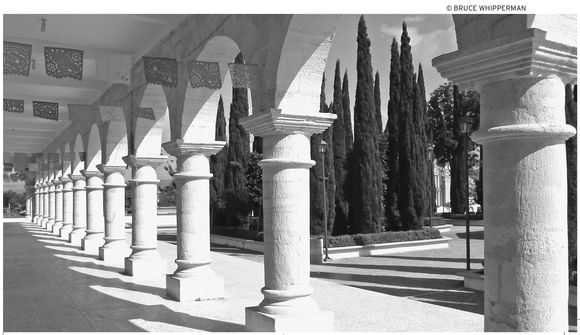

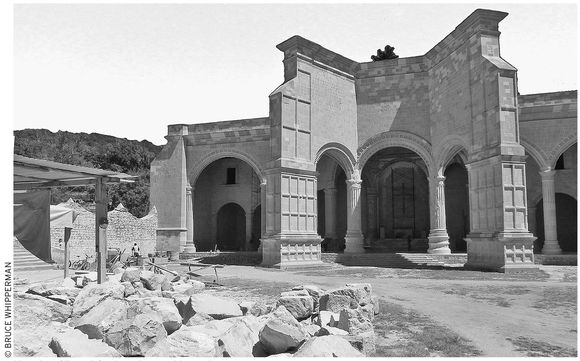

Templo y Ex-Convento de San Pedro y San Pablo

Templo y Ex-Convento de San Pedro y San Pablo

Most visitors head right over to the venerable 1538 Dominican church and ex-convent, one of Oaxaca’s most important, not only for its historical significance, but also for its monumental architecture, much of which you can view from the exterior by walking around to the church’s back (west) side. Here rises the famous, recently-restored Capilla Abierta (Open Chapel), with massive, soaring arches and gigantic buttresses. Visitors often wonder why such a huge outdoor chapel was needed right next to an equally massive indoor church. The adjacent grassy expanse provides the reason. It’s the atrium, the extension of the outdoor chapel, the largest in Mexico, where the Dominican builders imagined 10,000 native faithful (so numerous that they were not allowed inside) gathering for mass. Although their vision was fulfilled for a span of perhaps a generation after the conquest, European diseases decimated the Mixtec population by 1600, leaving the huge expanse, equal to three football fields, forever empty.

the Capilla Abierta (Open Chapel)

Step into the main church nave, accessible from outside either the nave’s rear door (next to the Capilla Abierta), or from side door on the town plaza. Inside, admire the symphony of glittering retablos (altarpieces) that decorate the walls. The tallest and most magnificent towers above the front altar, where the town patron El Señor de Vidrieras (Lord of the Glass Box) presides. On the right and left of the patron are the grand apostles, respectively: bald St. Peter and pious St. Paul. And, finally, above all the glitter, high over the altar, presides the omnipresent, all-seeing eye of God.

Local people celebrate their Señor de Vidrieras (named for the glass box they parade him in) during a big eight-day festival culminating on the first Friday of Lent (Cuaresma). Events include traffic-stopping processions, pilgrimages, a flower parade, plenty of fireworks, crowning of a queen, floats, bull roping and riding, and a big community dance.

Find the door to the ex-convent (9 A.M.–5 P.M. daily, entrance $2.50) at the rear of the nave. The ex-convent serves largely as a museum of paintings by noted 16th-century artists Andrés de la Concha and Simón Pereyns. As you walk, see if you can recognize the functions—refectory (dining), kitchen, chapel, cloister, monks’ cells (upstairs)—of the various rooms that you pass by or through.

During your visit, at the end of the refectory (monks’ dining hall) be sure to see the fresh, very recognizable modern or restored painting of Jesus with wounds, at the right hand of a very youthful God the Father, with the Holy Spirit (in the form of a radiant dove) above them. In the middle of the refectory, also notice the interesting painting of St. Michael the Archangel dangling a fish. Also, around the cloister, note the paintings that depict the baptism, school days, mission, and dreams of Santo Domingo.

Archaeological Sites and Casa de la Cacica

If you’re interested in historic ruins, you might inquire at the presidencia municipal for a guide to lead you to the El Fortín and Pueblo Viejo archaeological sites. (Note: Don’t try to go to these sites without permission, since local folks are rightly suspicious of strangers poking around their archaeological zones.)

An interesting, close-by site that you can visit without permission is the Casa de la Cacica (kah-SEE-kah, House of the Chiefess). Walk west about three blocks along the street heading due west from the middle of the church’s huge grassy atrium. The street ends at a school, and on the right is the Casa de la Cacica.

The Casa, a complex of buildings, is unique because it’s one of the few known stone structures built by the Spanish specifically for indigenous nobles. The Spaniards’ motivation was probably to concentrate and thus more easily control the local Mixtec population, who were living in dispersed hillside settlements when the Spanish arrived. They built a noble housing complex and evidently persuaded the local cacica (chiefess) to live there, hoping that her people would follow her. Presumably, the House of the Chiefess (under restoration) will eventually become a museum or community cultural center, or both.

Finally, before you leave town, be sure to visit the carcel (jail) at the presidencia municipal on the plaza. There, the prisoners make and sell handicrafts, such as leather belts, leather-covered mescal flasks, and miniature-shoe key rings.

Accommodations and Food

Teposcolula’s first and only hotel (at least in recent times), the Hotel Juvi (tel. 953/518-2064, $13 s, $15 d in one bed, $16 d in two beds, $18 t, $20 q) now makes an overnight stay possible. The hotel’s layout remains unique—12 rooms around a parking courtyard containing the last remnant, a grain storage crib, of the ancient family homestead. Children of the original ancestors have built a sparsely furnished (but clean) lodging, with bare fluorescent bulbs to go with the shiny bathroom fixtures.

You can buy basic food supplies at a plaza-front abarrotes (grocery); a panadería (bakery; on Iturbide, tel. 953/537-8683, 8 A.M.–8 P.M. daily), a block behind the presidencia municipal; or treat yourself to a hearty afternoon comida at the town’s good (but pricey) Restaurant Eunice (tel. 953/518-2017, 8 A.M.–8 P.M. Sun.–Fri., $4–12), a block behind the east side of the presidencia municipal.

Alternatively, go to the modest but clean restaurant Temita (tel. 953/518-2040, 7 A.M.–10 P.M. daily, $3–6), a block east (Oaxaca direction) of the plaza, across from the Cristóbal Colón–Sur bus station.

Information and Services

If you’re sick, consult Dr. Brigido Vidal in his Farmacia Nelly (on the plaza-front east side, a few doors from the highway, tel. 953/518-2072; consultations: 3–10 P.M.; pharmacy: 9 A.M.–2 P.M. and 5–9 P.M. Mon.–Sat.). Alternatively, go to the Centro de Salud (doctor available 8 A.M.–2 P.M. and 4–6 P.M. daily, 24 hours in emergency). Get there via Calle Madero, uphill, passing the presidencia municipal ’s west side. After two blocks, turn left, and continue three long blocks to the centro de salud, on the right.

For police or fire emergencies, contact the police at the presidencia municipal, north side of the plaza.

To mail a letter, make a phone call, or use a fax, go either to the telcomunicaciones (on Madero, upstairs, half a block north of the plaza’s northwest corner, tel. 953/518-2070, 9 A.M.–3 P.M. Mon.–Fri.) or the correo (on Madero, downstairs, 11 A.M.–4 P.M. Thurs. only). Otherwise for telephone, fax, or Internet go the “Mr. Marbo” office (across the highway from the plaza, tel. 953/518-2103, 7 A.M.–10:30 P.M. daily).

Getting There and Away

Bus transportation to and from Teposcolula is easy and frequent. Bus passengers arrive at and depart from the bus station (Autobuses Sur, Omnibus Cristóbal Colón, and Fletes y Pasajes; on Hwy. 125, tel. 953/518-2000), half a block east from the plaza. Buses connect southeast with Oaxaca City; north with Tamazulapan, Huajuapan, and Mexico City; and south with Tlaxiaco, Juxtlahuaca, and Putla (where connections are available with Pinotepa Nacional on the Pacific coast).

Long-distance vans Servicios Turísticos Teposcolula (local cell tel. 044-953/110-9288) connect frequently with Oaxaca and Tlaxiaco, from the small station directly across the highway from the town plaza.

For drivers, Highway 125 runs right past Teposcolula’s town plaza, about 13 kilometers (eight mi) southwest of its junction with the Oaxaca City–Mexico City Highway 190. To or from Oaxaca City, using the cuota autopista (toll expressway), drivers should allow around two hours to safely cover the approximately 125-kilometer (78 mi) Oaxaca City–Teposcolula distance; add at least another hour if going by the old Highway 190 libre (free) route via Yanhuitlán. To or from Tamazulapan in the north, allow about 45 minutes for the 35 kilometers (22 mi) via Highway 190–Highway 125 and about an hour for the 47 kilometers (29 mi) along Highway 125 to or from Tlaxiaco in the south.

YUCUNAMA

Teposcolula’s petite neighbor, Yucunama (pop. 600), is attractive partly because of its small size. Imagine taking a seat on a stone bench one bright, blue summer morning in Yucunama’s flower-decorated town plaza. Birds flit in the bushes and perch, singing, in the trees. Now and then, someone crosses the square and returns your “Buenos días.” You admire the proud, whitewashed bandstand at the plaza center; behind it rises the old church facade, patriotically decorated like a birthday cake in red, white, and green. From the plaza, cobbled streets pass rustic stone houses and continue downhill to verdant fields, which, in the distance, give way to lush oak and pine-tufted woodlands.

Although it sounds too good to be true, it isn’t. Yucunama’s beauty is probably one reason that Mixtec people have been living there for at least 4,000 years. Its name, which means Hill of Soap, perhaps reflects the town’s spic-and-span plaza, clean-swept streets, and newly painted public buildings. It’s a pure Mixtec town, for although Yucunama is part of the Teposcolula district, Spanish settlers never lived here. In fact, in 1585 the all-Mixtec townsfolk declared themselves an independent republic. Nothing came of that, but Yucunama’s people nevertheless retain their independent spirit.

The remarkable must-see Bee Nu’u (House of the People) community museum should be your first stop. The museum now only opens by appointment. Try contacting someone at the dignified, porticoed presidencia municipal, across the plaza from the museum. Say (or show them) this: “¿Puede alguién mostrar el museo para nosotros?” (“Can someone show us the museum?”)

If the presidencia municipal is closed, as it sometimes is, you have the pleasant alternative of knocking on the door of welcoming Señora Cleotilde San Pablo (local cell tel. 044-951 /105-1019, long distance tel. 045-951/105-1019, son Alvaro Emanuel’s email kopec_32@hotmail.com, food $5, lodging $10 pp) who runs the town restaurant Comedor Doña Coti on the north side of the plaza. She promises to find someone who will open the museum for you. Moreover, Cleotilde will also will fix you a meal and put you up in her large, comfortable house overnight. Contact her in Spanish, of course.

All of these preparations are well worth the chance to look inside the excellent, professionally prepared museum. Its several very interesting exhibits include the original of the Lienzo Yucunama, an amate (wild fig bark paper) document from the 1300s that details the 35 tribute payments of a Yucunama Mixtec noblewoman with the name-date 5-Eagle, and her first and second husbands, 12-Flower and 10-Eagle, to her father, who lived in a nearby town. In the cabinet below the lienzo stands a copy of the famous Codex Nuttall (folded like an accordion), which details, in full color, the exploits of the renowned Mixtec lord 8-Deer. Your guide may be able to provide some details (including odysseys to Coatzacoalcos on the Gulf Coast, and perhaps as far as Panama) of 8-Deer’s adventures. If you don’t understand Spanish, the museum is well worth bringing a friend to translate for you.

Another fascinating exhibit displays the complete remains of a robust 70-year-old noblewoman (notice her very husky leg bones) and the trove of goods recovered from her grave, one of a score of burials retrieved locally by archaeologists.

Yucunama’s richness as an archaeological zone is further evidenced by the two 1996 INAH (National Institute of Archaeology and History) survey maps of the buried remains of a pair of early Classic-period (300 B.C.–A.D. 300) towns nearby. If you’re strongly interested, ask at the presidencia municipal and you may be able to get permission and a guide. Expect to pay $20 for a full-day guided trip; transportation is extra.

On the other hand, you can step outside the museum and guide yourself on a short stroll to a pair of nearby local sights. Walk down Calle Independencia (from the museum, follow the left side of the plaza, past the presidencia municipal) about three long blocks east to the picture-perfect town fountain, fed by the old town aqueduct. You may see women doing the day’s laundry in the adjacent arched public washhouse basins. A block south and a couple more blocks downhill east, at the end of Calle Libertad, you can marvel at Yucunama’s oldest resident, the gigantic 1,000-year-old Tule, or ahuehuete tree (Mexican bald cypress, Taxodium mucronatum), a distant cousin of the California redwood. If you get lost, you can identify El Tule by its tall, bushy green silhouette, or mention El Tule (TOO-lay) to anyone.

Festivals

You’ll have even more fun if you arrive during one of Yucunama’s festivals. The biggest is the patronal Fiesta de San Pedro Mártir de Verona, which culminates on April 29. Festivities begin on April 26 with a calenda (procession) and plenty of mescal, aguardiente, and pulque for those so inclined to drink liquor. Sometimes town men dress up like women and perform the dance of the mascaritas (little masks). The fun continues with more processions, plenty of flowers, food, fireworks, masses, and a dance on April 29.

Other especially festive times in Yucunama include the fiesta of the Virgen del Rosario (first Sun. in Oct.), El Día de los Muertos (Day of the Dead, Nov. 1 and 2), and the Christmas Eve procession, where everyone in town accompanies the infant Jesus to the church, then watches (or does) the traditional dance of the Pastor y Pastorela (Shepherd and Shepherdess).

Getting There and Away

Yucunama is about nine kilometers (six mi) northwest of the Highway 125–Highway 190 intersection. Drivers: Follow the signed, graded gravel road that takes off from the north corner of the intersection. By bus: Ride an Omnibus Cristóbal Colón, Sur, or Fletes y Pasajes bus to the Highway 125–Highway 190 intersection, then hike the nine kilometers (six mi) or ride a colectivo van or truck from there. A number of snack stands and small stores at the intersection provide water and food.

YANHUITLÁN

It sometimes seems a miracle that the Dominican padres, against heavy odds and isolated as they were in the far province of Oaxaca, were able to build such masterpieces as their convent and church in Yanhuitlán. Upon reflection, however, their accomplishments seem less miraculous when you realize the mountain of help the padres received. When Father Domingo de la Cruz began the present church, in 1541, Yanhuitlán retained the prosperity and the large skilled population that it had when it was a reigning Mixtec kingdom prior to the arrival of the Spanish. For a workforce, de la Cruz used the labor of thousands of Mixtec workers and artisans, who deserve much of the credit for the masterfully refined monuments that they erected.

And monuments, indeed, they still are. Approaching Yanhuitlán from the northwest, the road reaches a hilltop point where the entire Yanhuitlán Valley spreads far below. In the bright afternoon sun, the white-shining, massively buttressed Yanhuitlán church and adjacent atrium (now soccer field), big enough for 15,000 indigenous faithful, dwarfs everything else in sight.

Up close, you see why. The building’s exquisitely sculptured Renaissance facade towers overhead, making those standing on the front steps appear like ants. A graceful semicircular arch frames the entrance, while in the niche to the left stands the robed St. Francis of Assisi. In the right niche, Santa Margarita de Alacoque occupies the position customarily reserved in Dominican church facades for Santo Domingo de Guzmán. The Dominican order’s revered founder, Santo Domingo de Guzmán, is nevertheless present. Directly above the front portal, a masterful relief of Holy Mother Mary shelters a diminutive Santo Domingo de Guzmán and Santa Catarina de Siena, like small children, beneath her cape.

The church, officially the Templo y Ex-Convento de Santo Domingo de Guzmán, is as much a museum of national treasures as it is a place of worship. In fact, it is divided so: The ex-convent, which you enter on the right, has been converted to a museum (9 A.M.–4 P.M. daily, $4). Inside, you begin to appreciate the gigantic proportions of the place as you circle the cloister, passing beneath ponderous but delicately designed arches that appear to sprout and spread from stone cloister columns like branches from giant trees. On the stairway leading upstairs at the cloister’s corner, don’t miss the mural of Jesus dressed like a 16th-century dandy except for his bare feet and the little angel perched on his shoulder.

The nave glows with golden decorations. Overhead, stone rib arches support the ceiling completely, without the need of columns, creating a single soaring heavenly space. Up front, above the altar, Santo Domingo de Guzmán presides, gazing piously toward heaven, his forehead decorated by a medallion that appears remarkably like a Hindu tilak. Before you exit, take a look by the front door for the dramatic painting of Jesus, whip in hand, driving the money changers from the temple.

Get to Yanhuitlán, on Highway 190, by car, van, or Sur, Fletes y Pasajes, or Omnibus Cristóbal Colón bus. By car, from Nochixtlán, head 12 miles (19 km) north along Highway 190 (62 miles from Oaxaca via the toll expressway, allow an hour and a half), or about 23 miles (37 km) south from Tamazulapan (or about the same from Teposcolula via Hwys. 125 and 190.)

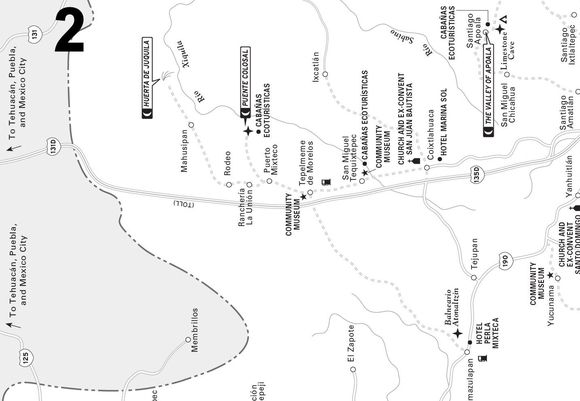

Dominican Route North

This corner of the Mixteca hides a treasury of undiscovered gems, just right for adventurers hankering to follow the road less traveled. First, make sure you spend some time at the grand old Dominican church at Coixtlahuaca, the Templo y Ex-Convento de San Juan Bautista. Then continue north to the hamlet of San Miguel Tequixtepec to contemplate the ancient (1590) stone bridge and the community museum’s mammoth fossils, then continue on a prehistoric rock painting excursion, and finally enjoy an overnight in San Miguel Tequixtepec’s cozy community-built cabaña lodging. Carry on north to Tepelmeme de Morelos and culminate your adventure by boulder-hopping down into a tropical canyon to the astonishingly grand Puente Colosal.

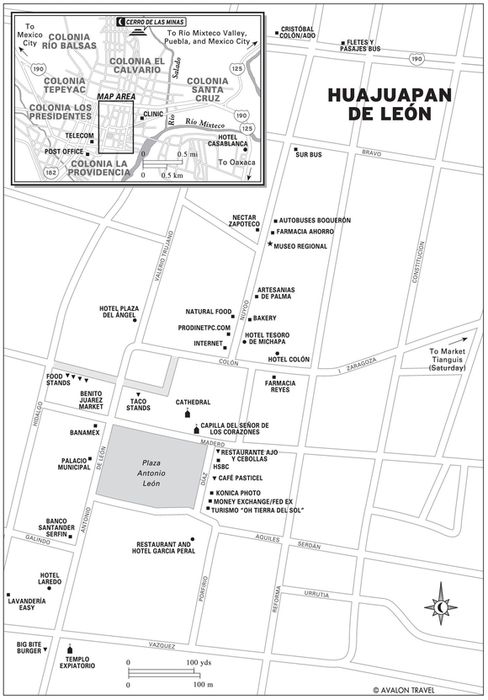

COIXTLAHUACA

Coixtlahuaca (koh-eeks-tlah-OOAH-kah, pop. 3,000), although the capital of an entire governmental district encompassing a significant fraction of the Mixteca Baja’s municipios, is a modest town even by Oaxaca standards. Before the conquest, it was a powerful Chocho-speaking (Chocholteco) chiefdom, so strong that in the 1400s the Coixtlahuaca warriors stopped the invading Aztecs, forcing them to detour through Tlaxiaco. During colonial times and through the 19th century, Coixtlahuaca continued to be an important Chocholteco market center. But depopulation by emigration and increased education and literacy in Spanish have reduced the number of Chocho speakers to a handful of elderly folks in the surrounding countryside.

Most visitors enter Coixtlahuaca by the cuota autopista from Oaxaca City. Just inside the edge of town, a big sign on the left marks the road north to San Miguel Tequixtepec. Straight ahead a couple more blocks, most drivers turn right on Independencia, the main town street. Nearly all stores and services are spread along Independencia, which continues several blocks past the town plaza and then the church, both above and to the left of the street. Bus passengers will arrive at the Autobuses Sur station, on Independencia, in the town center.

Sights

Coixtlahuaca’s past importance is reflected in its grand church, the Templo y Ex-Convento de San Juan Bautista, one of Oaxaca’s largest. At this writing, it appeared that its grand open chapel, similar to the one at Teposcolula, is being restored. Inside the church’s nave stretches to the proportions of a great European cathedral, its vault soaring overhead, supported by a delicate network of brilliantly painted colored stone arches. Dominican friar Francisco Marín, Coixtlahuaca’s first vicar, was the moving force behind all this grandeur, initiating construction in 1546. Although the Reforms forced closure of the convent in 1856, the Dominicans continued to run it as a church until 1906, when locally based “secular” clergy took over.

In addition to its robust proportions, the church has much of interest. As you enter, notice the dark-complexioned image of African padre San Martín de Porres, in a friar’s robe, on the right. Farther into the nave, gaze overhead and admire the whirling, rainbow-hued floral designs, lovingly executed by long-dead native artists. All are original, although time and recent replastering have erased much that you don’t see. On the right, take a look at the unusually large side altar to the Virgin of Guadalupe and continue to the main altar, where St. John the Baptist, Coixtlahuaca’s patron saint, presides at the foot of the towering, gilded retablo (altarpiece).

The town is mostly quiet, except for fiestas, which include the patronal festival of San Juan Bautista (around June 24) and the festival of the Señor del Calvario (Lord of Calvary), during the last half of May. The fiestas include processions, carnival games, traditional food, the hazardous jaripeo (bull roping and riding), and the Jarabe Chocholteco traditional Coixtlahuaca courtship dance.

Accommodations and Food

The only hotel along the expressway between Nochixtlán and Tehuacán, Puebla, is the local Hotel Marina Sol (Calle Independencia, tel. 953/503-5302, $22). Singles, doubles, and triples are available. Although it has been neglected in recent years, renovations are now complete. The owner’s motivation is most likely the ongoing restoration of the church across the street and the lavish parador turístico (tourist center), recently built nearby (but not yet operating at the time of this writing).

Although the Hotel Marina Sol’s rooms are modestly furnished, they’re clean and spacious, with private hot-water shower-baths. Summer humidity, however, has, in the past, caused the rooms to accumulate mildew. If so, beds will need fresh linens; don’t hesitate to request them before moving in. Guests additionally enjoy a tranquil garden setting, decorated with roses, statuesque Roman cypresses, and a countryside-view deck behind the reception. (You may have to ask around for the manager, who has been present only when guests were expected. If you can’t find the manager, or the rooms are unacceptable, it’s best to lodge at the cabañas in San Miguel Tequixtepec, a few miles north.)

As for food, Coixtlahuaca has two or three local-style comedores and taco shops on Independencia, plus the highly recommended Restaurant Blanquita (on the entrance road from the expressway, tel. 953/504-5420, 9 A.M.–9 P.M. daily, $2–3), downhill, a block below the road north to San Miguel Tequixtepec. Restaurant Blanquita is open for breakfast, including tasty huevos a la Mexicana; lunch, try guisado de res (beef stew) or chilote de pollo (spicy chicken); and supper, such as quesadillas.

Another Coixtlahuaca pleasant surprise is the fruit store, Frutería Juquilita (8 A.M.–8 P.M. daily), on the street above the town plaza and presidencia municipal.

Furthermore, some stores also offer a pair of renowned Coixtlahuaca baked specialties: menudencia rolls—big, brown, and not too sweet, sprinkled with a bit of sesame—and pancake cubes, made with alcoholic pulque instead of water.

Information and Services

Other services along Calle Independencia include a combined farmacia–larga distancia, La Lupita (Independencia, tel. 953/503-5405, 8 A.M.–8 P.M. daily).

At the town plaza, a few blocks east, before the church, next to the plaza-front library, find the telecomunicaciones (9 A.M.–3:30 P.M. Mon.–Fri.) for fax and money orders. Also find a correo (8 A.M.–4 P.M. Tues. only) nearby. Additionally, there is a centro de salud with doctor (8 A.M.–4 P.M. daily), tucked on the side street, between the town plaza and the church grounds.

For handicrafts shoppers, Artesanias del Sur (Independencia 20, tel. 953/503-5475), next to the bus station, offers a fetching collection of locally-crafted pottery, woven palm baskets, sombreros, wooden toys and trinkets, and more.

Getting There and Away

The Coixtlahuaca bus terminal is at the middle of main-street Independencia. Second-class Sur buses connect southeast with Nochixtlán (thence Oaxaca City); south with Tlaxiaco via Teposcolula; and northwest, via the toll expressway, with Tehuacán, Puebla, and Mexico.

A local bus connects Coixtlahuaca, with Highway 190 at Tejupan, accessible by collective taxi either northwest to Tamazulapan, or south, to Teposcolula.

To or from Coixtalahuaca, drivers can also connect with Oaxaca (or Puebla–Mexico City), via the fast and easy cuota autopista (toll expressway); it’s approximately 113 kilometers (70 mi), 80 minutes, to Oaxaca (or Puebla, two hours; Mexico City, four hours in the opposite direction).

Furthermore, drivers to and from Coixtlahuaca can take advantage of the short (24 km/15 mi, 45 minutes) connection with Highway 190 (thence Tamazulapan and Teposcolula) via the paved but sometimes potholed road from its Highway 190 junction at Tejupan.

SAN MIGUEL TEQUIXTEPEC

Tequixtepec is the Aztec translation of the town’s original Chocho name, Jna Niingui (Hill of the Conch). Local legend says that Tequixtepec was the site of a now-lost temple dedicated to the god of the conch.

The local region comprises the municipio of San Miguel Tequixtepec; once rich, fertile, and thickly populated, it has fallen on hard times. Overgrazing, tree cutting, and selling the stones from the old irrigation terraces have degraded the Tequixtepec region into a semi-desert. Many hills are half-eroded, bare stone. Some good land exists at the stream bottoms, but many people are discouraged by such hardscrabble farming. Most residents leave to work for a year in Oaxaca City, Mexico City, or the United States, then come back and live for three or four years on their earnings. The population has dwindled from 3,000 around 1900 to perhaps 400 now.

It turns out, however, that San Miguel Tequixtepec is a village with grit. It shows in the people and their efforts to reverse their fortunes. A major moving force behind the local folks’ determination is personable community leader Juan Cruz Reyes, who spearheaded the remodeling of a ruined schoolhouse into a working museum, now a focus for showing off Tequixtepec’s valuable touristic assets: a graceful 1909 presidencia municipal, a dignified 18th-century church, woven-palm handicrafts, and, in the vicinity, a colonial-era fossil bridge and prehistoric rock paintings.

Sights

If you arrive heading north along the road from Coixtlahuaca, after about eight kilometers (five mi) you cross a creek bridge, where you can gaze upon an adjacent, crumbling, early colonial-era stone-arched bridge. It’s a remnant of Tequixtepec’s glory days, when merchants marketed small fortunes of locally grown silk and red cochineal dye. Tequixtepec tradition says that one such merchant, Don Diego de San Miguel, built the bridge around 1590 to easily transport his valuable silk and cochineal to the formerly big market in Coixtlahuaca. (Although still crossable on foot at this writing, the old bridge is in bad shape. Hopefully, it will be restored, before it falls victim to old age.)

At the town plaza three kilometers (two mi) farther north, make your first stop at the community museum. While there are no regular operating hours, a volunteer will often be available to show you the exhibits of local historical lore, fossils (notably, a huge mammoth tusk), local archaeological finds, and handicrafts. If the museum is closed, check at the presidencia municipal, across the plaza.

If you’ve made a prior appointment (tel. 953/503-5407), volunteers will be available to show you around the town, probably starting at the museum, then the town church, the Parroquia de San Miguel Arcángel, built of locally quarried rose cantera stone and finished in 1766. The vases you see topping the churchyard fence are from Atzompa, near Oaxaca City, and are always ready to be filled with flowers during the town’s festivals. Foremost is the big September 27–29 town patronal fiesta in honor of San Miguel. Highlights include traditional dances, such as the Cristianos y Moros (Christians and Moors). Other important fiestas are celebrated on Palm Sunday (Domingo de Ramos) and Sábado de Gloria (the Sat. before Easter Sun.), when people, for the occasion called mecos, don masks and do a kind of adult trick or treat. They go from store to store, asking for something to drink and dancing with whomever is present. Yet another important day in Tequixtepec is Sunday, when, between 3 and 4 P.M., teams face off for a game of pelota mixteca, the local version of the ancient Mesoamerican ball game.