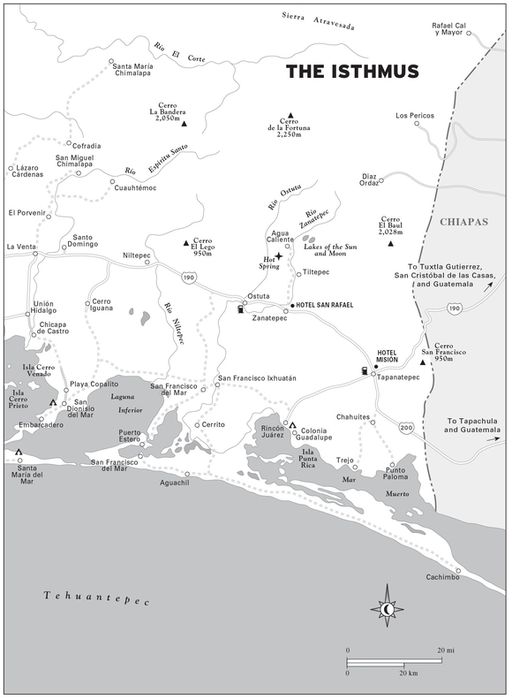

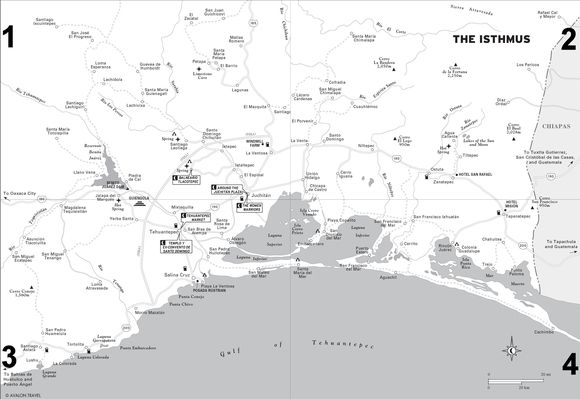

THE ISTHMUS

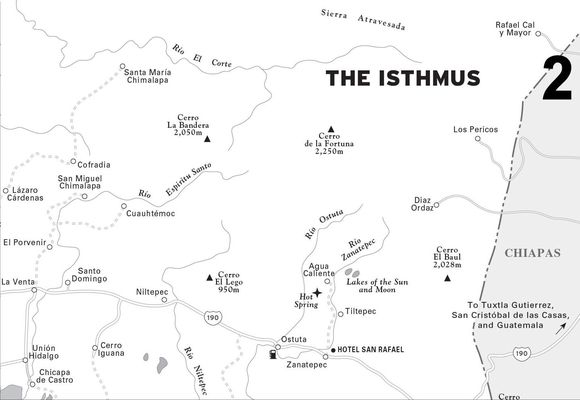

A trip to the Isthmus of Tehuántepec from the Oaxaca central highlands sometimes seems like a journey to another country. At the Isthmus, the North American continent narrows to a scarce 160 kilometers (100 mi) in width; the mighty Sierras shrink to mere foothills. The climate is tropical; the land is fertile and well watered. Luxuriant groves hang heavy with almonds, avocados, coconuts, mangos, and oranges. Rivers wind downhill to the sea, springs well up at the foot of mountains, and swarms of fish swim offshore. The Isthmus is a land of abundance, and it shows in the people. Women are renowned for their beauty, independent spirit, and their incomparably lovely flowered skirts and blouses, which young and old seem to wear at any excuse.

And they have excuses aplenty, for the Isthmus is the place of the velas, called fiestas in other parts of Mexico. But in the Isthmus, especially in the towns of Tehuántepec and Juchitán, where istmeño hearts beat fastest, velas are something more special. Most every barrio (neighborhood) must celebrate one in honor of its patron saint. A short list names 20 major yearly velas in Juchitán alone. The long list, including all the towns in the Isthmus, numbers more than 100.

If you’re lucky to arrive during one of these velas, you may even be invited to share in the fun. Local folks dress up, women in their spectacularly flowered traje (traditional indigenous dress) and men with their diminutive Tehuántepec sombreros, red kerchiefs, sashes, and machetes. Sometimes entire villages or town barrios celebrate for days, eating, drinking, and dancing to the beautiful melody of “La Sandunga,” which, once you’ve been captured by its lovely, lilting strains, will always bring back your most cherished Isthmus memories.

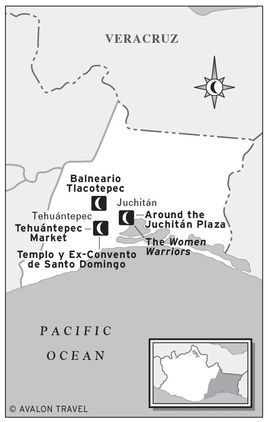

HIGHLIGHTS

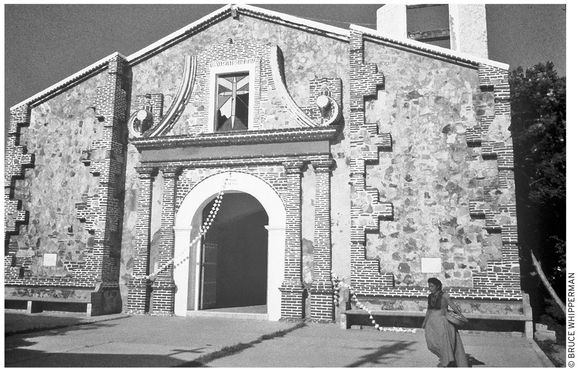

Templo y Ex-Convento de Santo Domingo: Around the Tehuántepec town plaza, the highlight is the church and partially restored, circa 1530 Templo y Ex-Convento de Santo Domingo. Be sure to see the recently discovered wall decorations painted by indigenous artists 450 years ago (

Templo y Ex-Convento de Santo Domingo: Around the Tehuántepec town plaza, the highlight is the church and partially restored, circa 1530 Templo y Ex-Convento de Santo Domingo. Be sure to see the recently discovered wall decorations painted by indigenous artists 450 years ago ( Templo y Ex-Convento de Santo Domingo).

Templo y Ex-Convento de Santo Domingo).

Tehuántepec Market: The native women, in their extravagant and colorful floral huipiles, steal the show at the Tehuántepec market (

Tehuántepec Market: The native women, in their extravagant and colorful floral huipiles, steal the show at the Tehuántepec market ( Tehuántepec Market).

Tehuántepec Market).

Around the Juchitán Plaza: The flowers, gold filigree, and flowery embroiderered huipiles for sale, not to mention the all-female cadre of vendors, are the main attraction on the Juchitán plaza (

Around the Juchitán Plaza: The flowers, gold filigree, and flowery embroiderered huipiles for sale, not to mention the all-female cadre of vendors, are the main attraction on the Juchitán plaza ( Around the Juchitán Plaza).

Around the Juchitán Plaza).

The Women Warriors: From the river bridge, enjoy the airy view and cooling breeze, then cross over to the west bank and admire the Women Warriors, stainless steel guardians of Juchitán (

The Women Warriors: From the river bridge, enjoy the airy view and cooling breeze, then cross over to the west bank and admire the Women Warriors, stainless steel guardians of Juchitán ( The Women Warriors).

The Women Warriors).

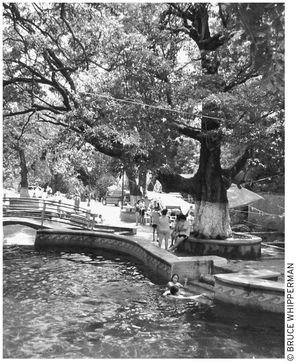

Balneario Tlacotepec: Heroine Princess Donaji donated this precious crystal spring and park for Isthmus people to enjoy, something they have done with gusto for more than four centuries (

Balneario Tlacotepec: Heroine Princess Donaji donated this precious crystal spring and park for Isthmus people to enjoy, something they have done with gusto for more than four centuries ( Balneario Tlacotepec).

Balneario Tlacotepec).

LOOK FOR  TO FIND RECOMMENDED SIGHTS, ACTIVITIES, DINING, AND LODGING.

TO FIND RECOMMENDED SIGHTS, ACTIVITIES, DINING, AND LODGING.

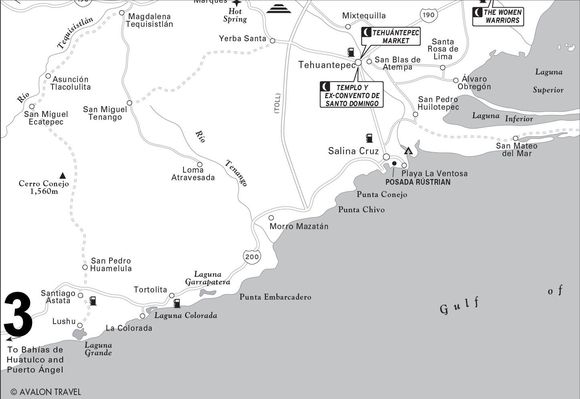

PLANNING YOUR TIME

A convenient route to including the Isthmus in your Oaxaca plan would be with a circular side trip, including the vibrant market towns of Tehuántepec and Juchitán en route between Oaxaca City and the Pacific resorts. For example, you could bus, drive, or fly south to the coast, spend some days basking in the South Seas ambience of the Pacific resorts, then begin your return to Oaxaca City east along the coast by either bus, car, or tour, enjoying four days along the way exploring the colorful markets, cuisine, and sights, both manufactured and natural, of the Isthmus.

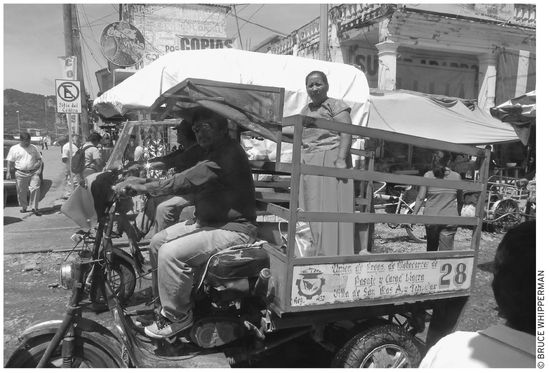

For example, be sure to do plenty of strolling, and perhaps some shopping, in the fascinatingly colorful Tehuántepec Market hubbub, highlighted especially by the tehuana women in their radiantly colorful native dress. Along the way, be sure to do as the local folks do and hop aboard a motocarro (small motorcycle truck) for a ride around town. Later, don’t miss enjoying at least one deliciously authentic Tehuántepec meal in the showplace Restaurant Scaru. With an additional day, you could enjoy a day trip to Guiengola ruined mountain fortress city, continuing on for a soak in the authentically rustic agua caliente (warm spring) at Jalapa del Marqués village, and/or a lake bass dinner at restful garden Restaurant Del Camino.

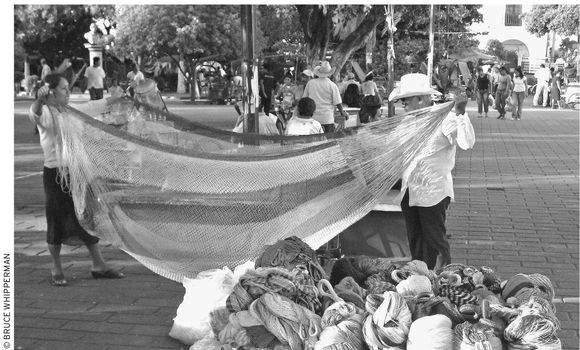

hammocks for sale in Juchitán

The next day, continue east half an hour to Juchitán. Here, soak in the colorful scene with plenty of strolling around the Juchitán plaza and market. Along the way, be sure to see the vibrant flower and handicrafts stalls, with riots of roses and lilies and their gold filigree, exquisite flowered huipiles, bright hammocks, multicolored pottery, and much more. Take a break with lunch in the airy inner patio of the plaza-front Restaurant Casa Grande. In the later afternoon, don’t miss strolling a few blocks west to enjoy the breeze and view from the tranquil Río Los Perros riverbank. And especially don’t miss taking a look at the monumental Women Warriors stainless steel sculptures overlooking the river.

Finally, enjoy another day by taking a picnic (and your bathing suit) to the historical and uniquely lovely Isthmus excursion park, at the crystalline blue springs that bubble up at Balneario Tlacotepec, about an hour by bus north of Juchitán.

Tehuántepec and Vicinity

Although both Juchitán and Salina Cruz are the Isthmus’s big, bustling business centers, quieter, more traditional Tehuántepec remains foremost in the minds of most istmeños as the former pre-Columbian royal capital, the seat of Cosijopí, the beloved last king of the Zapotecs. Local people are constantly reminded of their rich royal history by virtue of the Templo y Ex-Convento de Santo Domingo, the construction of which was unique in Oaxaca because it was financed by an indigenous monarch, Cosijopí. Moreover, local people can directly see their ancestors’ contribution to history by glimpsing the ancient (recently discovered) floral and animal decorations that their ancestors painted on the walls of the ex-convent nearly half a millennium ago.

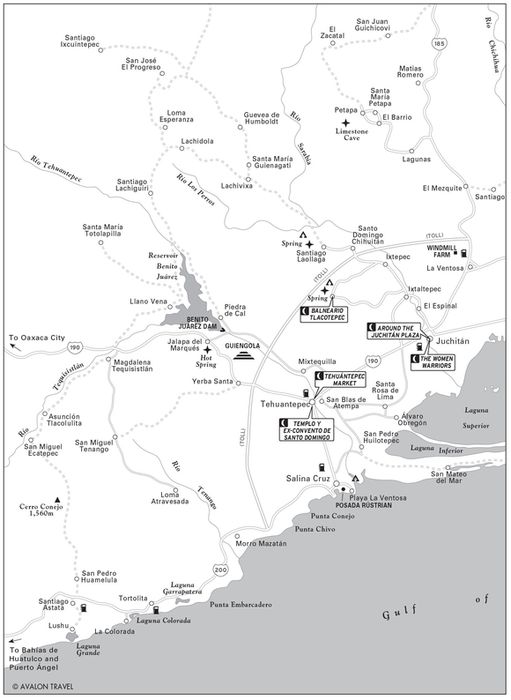

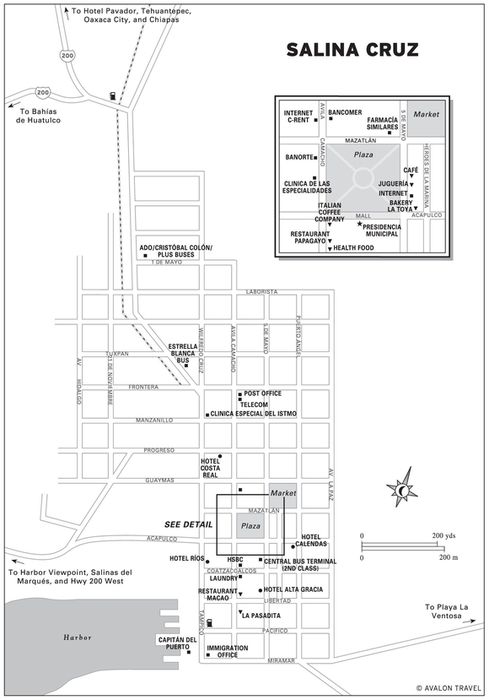

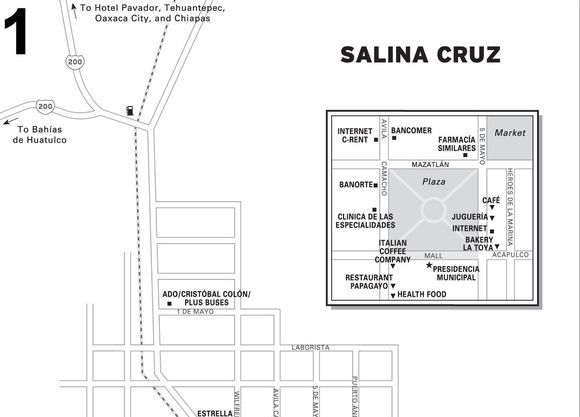

The town of Tehuántepec is geographically the center of the Isthmus. Roads, like spokes of a wheel, branch out in all directions, south to Salina Cruz, northeast to Juchitán, and northwest to Oaxaca City. This means that travelers from Oaxaca City most easily reach both Juchitán and Salina Cruz by passing through the fortunate town of Tehuántepec.

HISTORY

Although strictly connected only with a single location, the name Tehuántepec (Hill of the Jaguar) is, in many minds, synonymous with the entire Isthmus region: thus the label the “Isthmus of Tehuántepec.” The connection is historical, for Tehuántepec’s dominance was born in events of long ago.

The earliest known settlers in the Isthmus left Olmec-style remains, which archaeologists date from as early as 4000 B.C. Much later, around 500 B.C., the Olmecs’ inheritors, probably the ancestors of present-day Mixe- and Huave-speaking people, occupied the Isthmus lands. But times changed, and by A.D. 500 the Isthmus had become a strategic funnel: a trade gateway between the great civilizations, such as Teotihuacán and Monte Albán, of the Mexican central highlands, and the rich Mayan cultures of Chiapas, Yucatán, and Guatemala.

Eventually, the more populous Zapotec-speaking people displaced the Mixe and Huave in the Isthmus. By A.D. 1400, the Zapotec kings of Zaachila in Oaxaca’s central valley controlled the Isthmus gateway with a mountaintop fort at Guiengola, which guarded their Isthmus capital at the present-day town of Tehuántepec.

The ambitious Aztec emperors also coveted the Isthmus gateway. In the 1440s, they sent armies to Oaxaca to pressure the Mixtec and Zapotec kingdoms, who allied themselves against the Aztecs. But forced by Aztec victories in 1486, many Zapotec people, including their king Cosijoeza, retreated from Zaachila and took refuge in Tehuántepec. There, together with the Mixtecs under King Dzahuindanda, the Zapotecs, attacking from their stronghold at Guiengola, held off the Aztecs, who offered Emperor Moctezuma’s daughter in marriage to King Cosijoeza as part of a peace pact.

With tranquility established, Cosijoeza returned to reign once again over Zaachila, leaving his son, Cosijopí, as king of the Isthmus, with his court at Tehuántepec. Later, when the Spanish arrived, King Cosijopí joined with Cortés against the Aztecs. After Aztec power was erased, Cosijopí, along with thousands of his subject-inhabitants of Tehuántepec, converted to Christianity.

ORIENTATION

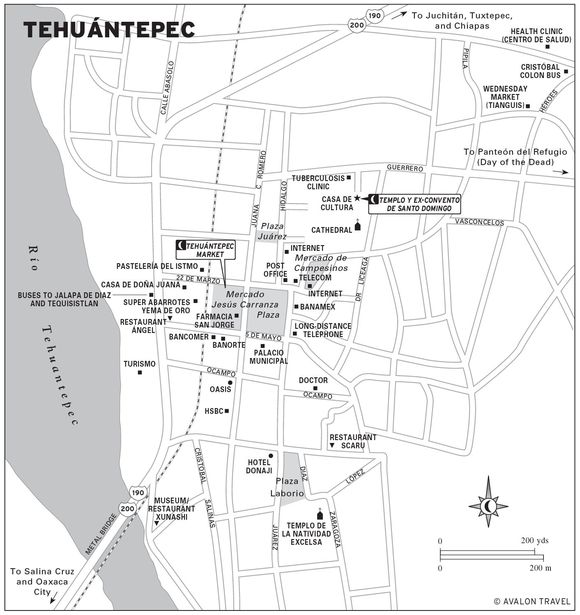

Although the Río Tehuántepec splits the Santo Domingo Tehuántepec town (pop. 52,000) along a roughly north–south line, the west-side portion, across the river via the Puente Metalico (Metal Bridge), first built for locomotives around 1900, seems like a mere suburb of the town center, east of the river. On the central plaza itself, the presidencia municipal occupies the south side, along Calle 5 de Mayo; the main market, Mercado Jesús Carranza, lies on the plaza’s west, river side, along Calle Juana C. Romero; and to the northeast, past the end of main north–south street Benito Juárez, about a block and a half northeast of the plaza, stands Tehuántepec’s most venerable monument, the Templo y Ex-Convento de Santo Domingo.

SIGHTS

Around the Plaza

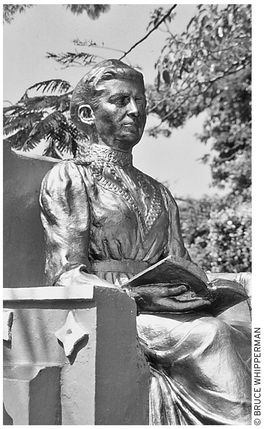

First, take a stroll around the plaza, where you’ll find some interesting sculptures, including noble likenesses of Miguel Hidalgo (the Father of Mexican Independence) and a pair of Tehuántepec heroes. On the north side, look for the bronze of a seated Doña Juana Catalina Romero (1855–1915), a Tehuántepec legend. She is famous partly for her good works, establishing schools for Tehuántepec children during the days when public education was a rarity in Mexico.

On the plaza’s west (market) side, you’ll find the bronze bust of A. Maximino Ramón Ortiz, the first and only governor of the Isthmus, when it was separated from Oaxaca as the territory of Tehuántepec for a few years during the 1850s. Politics, however, were not Ortiz’s first love. He is best remembered as the composer of “La Sandunga,” Tehuántepec’s beloved theme. His ageless melody seems to perfectly capture the essence of the Isthmus in a gracefully drowsy rhythm that swings slowly, yet deliberately, like the relaxed sway of lovers in a hammock beneath the deep shade of a Tehuántepec grove.

Templo y Ex-Convento de Santo Domingo

Templo y Ex-Convento de Santo Domingo

From the plaza’s northeast corner, walk north along Calle Hidalgo one block to the venerable Santo Domingo church, behind its broad fenced atrium, on the right. The aging landmark (to the left of the new church) is interesting partly because it was one of the few, if not the only, Christian churches in Mexico financed by a native ruler. Cosijopí, the last king of the Zapotecs, was baptized as Juan Cortés de Cosijopí after his friend and ally Hernán Cortés paid for the construction with both cash and the labor of thousands of his subjects. The building was erected under the supervision of Fray Fernando de Albequerque, vicar of Tehuántepec, between 1544 and 1550.

Given the warm relations between King Cosijopí and the Spanish, it is ironic that the Inquisition authorities burned Cosijopí at the stake a generation later for continuing (and for encouraging his people) to worship the old gods.

Enter through an interior side door, off the left-aisle of the very attractive new church. Inside, old Santo Domingo’s most remarkable feature is its lovely wooden tabla (altarpiece), with an unusual ebony Lord of Creation perched on its crest, with a dog, turtle, and deer in tow. (At last visit, the ebony statue had been removed, but a local priest told me that it would probably be returned after the present church remodeling work is finished.)

The ex-convent section, on the old church’s north side, was abandoned not long after the Reforms of the late 1850s forced the Dominicans from Mexico. It had crumbled into a virtual ruin by the mid-20th century, when local people rolled up their sleeves and began restoring it in 1953. In 1982, with the restoration complete, the townsfolk christened their ex-convent as the Casa de la Cultura (tel. 971/715-0114, 9 A.M.–2 P.M. and 5–8 P.M. Mon.–Fri., 9 A.M.–2 P.M. Sat.). Now, in the evenings it resounds with the noises of young musicians and dancers at practice.

To take a look inside the restored ex-convent, retrace your steps out across the atrium, turn right at Calle Hidalgo, and walk north. After two short blocks, turn right at Guerrero. Walk one long block. Just after the tuberculosis clinic (formerly centro de salud) turn right into an alley, which leads directly south to the Casa de la Cultura and the old convent.

Inside the Casa de la Cultura, look for the faded but still-visible flower and animal motifs that Cosijopí’s long-gone artists painted on the walls nearly four centuries ago. Head upstairs where the ancient wall decorations appear as fresh as if they were painted only a generation ago. In other upstairs rooms you’ll see a host of historical mementos, from ancient Olmec-style figurines to a lovely jade necklace, once scattered, but excavated piece by piece and finally reassembled here. (Sometimes the upstairs is closed. If so, it’s worth seeking permission from the administrative secretary on the ground floor, in the cloister, to let you go upstairs.)

Tehuántepec Market

Tehuántepec Market

The most colorful downtown action goes on at the Mercado Jesús Carranza, just across Romero from the plaza. At midday, the market overflows with life. The center of everything is the corridor street on the market’s north side, which connects the plaza with the businesses along the railroad tracks behind the market.

The buzzing motocarros (motorcycle mini-trucks) that you see depositing and picking up passengers by the railroad track seem to be a unique Isthmus invention. They mostly follow set round-trip routes around town for a fixed price of about $1 (10 pesos). When you get tired of walking, hop on for a breezy whirlwind tour of Tehuántepec’s back streets.

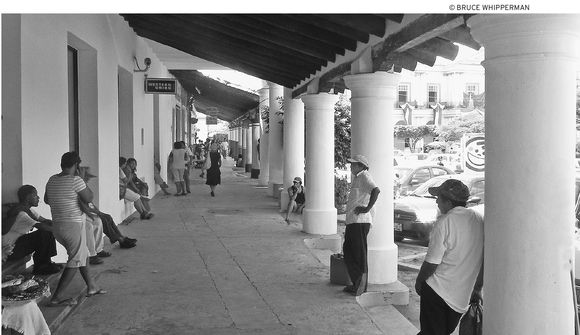

Women do virtually all the buying and selling at the Tehuántepec Market.

See JUAN CATALINA ROMERO: HEROINE OF TEHÚANTEPEC

Market vendors, especially women in traje (traditional indigenous dress), tend to be apprehensive of rubber-necking strangers with cameras in hand. A good strategy is to blend in. Get a refresco (refreshment) at one of the food stalls and find a low-profile spot in the shade where you can take in the passing scene.

Get some relief from the heat and bustle inside the roofed market building itself. If you’re in the mood for shopping, plenty of handicrafts are available. On the bottom floor, stalls offer the gold filigree jewelry (at this writing, mostly faux-gold filigree, since gold is so expensive) that the Tehuántepec women love to wear. Look farther for lots of woven goods, such as baskets, string bags of ixtle fiber, hand fans, and hammocks. One unusual item that you may see during the late spring are large, one-meter-long (three-foot-long) pods of decorative flowers of coyul.

Upstairs, via the stairway on the southwest corner by the railroad track, you’ll find Tehuántepec’s pride—the beautiful embroidered tehuana flowered blouses and skirts. Look around, decide what you want, then bargain for it. Asking prices for the prized, embroidered flower–design blouses run as much as $100, a whole outfit about $200, with bargaining.

Behind the market runs the railway track, which has the distinct appearance of being abandoned, because dozens of vendors regularly set up where trains should come rolling through.

Pottery, including many big, homely items—bowls, griddles, planters, pots—is for sale at the second downtown market, the lackluster Mercado 5 de Febrero, sometimes known as the Mercado de Campesinos, tucked at the plaza’s northwest corner. Smaller for-sale items include pots painted with bright flowers as well as woven goods, such as baskets, fans, and handmade brooms and piñatas.

Besides the two aforementioned permanent daily markets near the plaza, country people flood into town for tianguis (native town market) on Wednesday and Sunday. Visit the Wednesday tianguis, set up along north-side Calle Héroes, most easily by riding a motocarro from the plaza. Alternatively, from the plaza, walk north along Hidalgo past the church. Two blocks from the plaza, turn right at Guerrero and continue several blocks to the blue-trimmed San Juan Bautista church, where you turn left at Héroes. After a few blocks, you’ll see the awnings stretched along side streets.

The Sunday tianguis is much bigger, so much so that it’s held on the west side across the river, beyond the big Oaxaca highway intersection, in the open space behind the Hotel Gueixhoba.

Casa de Doña Juana Catalina Romero

The railway track so intimately close to the market is due to the speculated intimate relationship between President Porfirio Díaz and local beauty Doña Juana Catalina Romero (1837–1915). Doña Juana Catalina lived in the French-style mansion, now in faded white with fancy blue window awnings in need of serious renovation, which rises by the tracks. Some say that the tracks were built right out front so Díaz could visit her with ease. Until recent years Doña Juana Catalina’s elderly granddaughter resided there. Lately, with her retirement, her heirs subsequently sold the house to another family. It is rumored that the state and community are planning to buy it and convert it into a museum.

La Cueva

If you feel like an early-morning or late-afternoon walk, head for La Cueva (The Cave), as local folks call it. It’s visible most of the way up the hill called Liesa, across the river about three kilometers (two mi) west of town. La Cueva has been hallowed ground for as long as anyone remembers. Local folks tell stories about the existence of a secret passageway somewhere at the back of the cave that leads all the way to Guiengola, the “old town,” now a mysterious ruin on the mountain 16 kilometers (10 mi) to the west.

La Cueva still draws virtually everyone in town for a pilgrimage during both Semana Santa (Good Friday) and Día de la Cruz (May 3). It’s best not to try the climb during the heat of the day (allow at least an hour for the whole excursion). In order to get a head start, spend a couple of dollars (20 pesos) on a taxi or motocarro (motorcycle mini-truck) to take you to the base of the hill.

Plaza Laborio

A number of smaller plazas dot Tehuántepec’s several barrios. If you head south along Juárez two long blocks, you’ll arrive at Plaza Laborio and its adjacent blue-trimmed, storybook Templo de la Natividad Excelsa. Before you go inside to look around, notice that the right bell tower is tilted at a crazy angle, not unlike the Leaning Tower of Pisa. Laborio (the name of the church’s barrio) residents don’t seem to worry. “It’s been like that for years,” they say.

Plaza Laborio is mostly sleepy, except during the August 31–September 11 Fiesta Laborio, when residents and visitors celebrate with a long menu of feasts, dancing, fireworks, and calendas (processions).

Museum and Restaurant Xunashi

Housed in a colonial-era family mansion-factory, this museum (Callejon El Faro 1A, local cell tel. 971/129-7990, noon–5 P.M. daily, $3) is decorated with a flock of antiques, that range from a giant portrait of the Virgin of Guadalupe and ancient wooden looms, to an entire chapel of devotional memorabilia and a whole kitchen of great pottery jugs.

Welcoming owners Jose Manuel Villalobos and his wife Mari Carmen and their children offer a hearty Mexican comida (noon–5 P.M. daily, $6) in their baronial river-view dining room. Get there either by short taxi ride from the plaza, or walking two blocks south from the plaza’s southwest corner. Turn right at the Hotel Donaji (corner of Plaza Laborio) and continue another two blocks, to the corner of Cristobal Salinas. Turn left one block, then turn right and continue a short block to the mansion, above, on the right.

Museum and Restaurant Xunashi offers a hearty Mexican lunch in the midst of colonial-era furnishings.

Barrio de Santa María

Also worth a visit, across the river, is the Barrio de Santa María. (Get there by bearing left at the street heading diagonally left from the highway, a block or two west of the river bridge; after about two more blocks, go left again.) The main community pride and joy is the (also bright blue and white) Templo de la Virgen de la Asunción. The church, by the same architect who built the famous pilgrimage church in Juquila, is the focus of a busy round of barrio events. The bustle climaxes during the August 13–18 Fiesta Patronal del Barrio de Santa María Reolotoca, with a calenda (procession), parade of flower-decorated bull-drawn carts, and earsplitting popular dances on three successive nights. Bring your earplugs.

ACCOMMODATIONS

Under $50

Tehuántepec offers visitors at least three hotels: one is semi-deluxe, in the west suburb; and a pair downtown is more modest, but very recommendable. A good choice downtown is the Oasis (Melchor Ocampo 8, tel. 971/715-0008, fax 971/715-0835, www.hotelesdeoaxaca.com, hoteloasistehuantepec.html, h.oasis@hotmail.com, ($18 s, $22 d one bed, $26 d in two beds, $30 t with fans; or $30 s, $35 d with a/c), removed a block south from the plaza hubbub, behind the presidencia municipal. Although at first glance the Oasis doesn’t appear very exciting, a closer examination reveals the talents of the owner, friendly English-speaking artist Julín (hoo-LEEN) Contreras, whose work decorates the hotel’s restaurant wall. (She was also commissioned to do the mural in the council chamber on the 2nd floor of the presidencia municipal.)

The hotel building offers four stories of 28 clean and comfortable rooms that enfold in an invitingly leafy and tranquil inner patio. The rooms feature colorful bedspreads and curtains, walls decorated with the owner’s art, and private warm-water shower-baths. In most rooms, windows open to a garden, mountain, or river view. Pottery and plants selected by the owner decorate hotel niches and corridors. In the building’s inner patio, a towering chico zapote tree stretches skyward. A parking lot provides security for cars. There is a good, relaxed, Restaurant Almendro (Almond Tree). Visa credit cards and dogs and cats are accepted. For lovers of the way Mexico “used to be,” this is the place. Besides all of the above, Julín invites guests to visit her on-site art studio and also offers Isthmus culinary tours. A couple of minuses are the hotel’s corridor rooms, where curtains must be drawn for privacy, and the hotel’s sometimes lackadaisical desk staff.

An arguably better choice downtown is the Hotel Denali (Juarez 10, tel. 971/715-0064, fax 971/715-0448, hoteldonaji@hotmail.com, $20 s, $25 d fan only, $30 s, $35 d with a/c), named for Oaxaca’s beloved Apothecia heroine and located two blocks south of the plaza on quiet Plaza Laborio. This renovated hotel is very popular locally by virtue of its inviting, plant-decorated inner restaurant patio. The 48 rooms, in a big two-story block, are simply but invitingly decorated, with hot-water shower-baths, cable TV, a small pool-patio, and credit cards accepted.

Over $50

Tehuántepec’s fanciest hotel is the four-star  Hotel Guiexhoba (ghee-ay-SHOW-bah; Carretera Panamericana Km 250.5, Barrio Santa María, tel./fax 971/715-1710 or 971/715-0416, guiexhoba@prodigy.net.mx, $45 s, $58 d, $70 t), which deserves extra points simply for its Zapotec label, the name of a locally abundant white flower with a fragrant scent reminiscent of jasmine. The hotel has a specimen bush, which blooms during the summer rainy season, by the front entrance. Find the hotel on Highway 190, inbound from Oaxaca City on the right before the bridge.

Hotel Guiexhoba (ghee-ay-SHOW-bah; Carretera Panamericana Km 250.5, Barrio Santa María, tel./fax 971/715-1710 or 971/715-0416, guiexhoba@prodigy.net.mx, $45 s, $58 d, $70 t), which deserves extra points simply for its Zapotec label, the name of a locally abundant white flower with a fragrant scent reminiscent of jasmine. The hotel has a specimen bush, which blooms during the summer rainy season, by the front entrance. Find the hotel on Highway 190, inbound from Oaxaca City on the right before the bridge.

The Guiexhoba’s 36 spacious, clean, and comfortable rooms, in two stories, enclose a parking courtyard that fortunately shields rooms on its north side from highway noise. Staff are generally attentive, competent, and courteous. The upstairs rooms away from the highway are quiet and have fewer people walking past the windows, whose drapes, unfortunately, must be drawn for privacy. Amenities include big pool, parking, cable TV, air-conditioning, hot-water shower-baths, credit cards accepted, in-house Internet, and the very good Restaurant Guiexhoba.

FOOD

Groceries and Treats

Tehuántepec’s freshest fruit and vegetable sources by far are the luscious mounds of avocados, bananas, carrots, lettuce, mangos, pineapples, radishes, and much more in the plaza market. Likewise, find the best grocery sources, such as the Super Abarrotes Yema (tel. 971/715-0489, 8 A.M.–8:30 P.M. daily), by the railroad tracks just west (river side) of the market.

Satisfy your sweet tooth with the baked offerings of the Super Panadería y Pastelería del Istmo (tel. 971/715-0808, 8 A.M.–8:30 P.M. daily). Find it on the railroad tracks, just north of the market, on the left. For evening snacks, fill up at the taco stalls lined up behind the presidencia municipal.

Restaurants

You’ll probably find that it’s most convenient to have breakfast at your hotel, such as the Restaurant Almendro (Melchor Ocampo 8, tel. 971/715-0008, fax 971/715-0835, www.hotelesdeoaxaca.com) of the Oasis hotel and the restaurant at the Hotel Guiexhoba. Otherwise go to Tehuántepec’s best, the refined Restaurant Scaru, three blocks south of the plaza.

Tehuántepec offers a sprinkling of good sit-down restaurants. By far the most colorful is the  Restaurant Scaru (at south-side cul-de-sac Callejon Leona Vicario 4, tel. 971/715-0646, 8 A.M.–11 P.M. daily, $5–10). Here, in a graceful, airy setting, owners lovingly portray picturesque aspects of traditional Isthmus life. Walls bloom with murals of fruit, festivals, and lovely tehuanas in their bright, flowery costumes, while patios are sprinkled with hammocks and sheltered overhead by luxurious handcrafted palapas. Saturday and Sunday afternoons 2–6 P.M., a marimba band will play “La Sandunga” to your heart’s content. After such a luscious introduction, the food, from a very recognizable menu of salads, soups, eggs, pastas, meats (including some game), fish, and fowl, is no less than you would expect. Get there from the plaza by walking two long blocks south along Juárez to Plaza Laborio. Turn left and walk one block to Callejon Leona Vicario on the left; the restaurant is on the uphill side of the street. Credit cards are not accepted.

Restaurant Scaru (at south-side cul-de-sac Callejon Leona Vicario 4, tel. 971/715-0646, 8 A.M.–11 P.M. daily, $5–10). Here, in a graceful, airy setting, owners lovingly portray picturesque aspects of traditional Isthmus life. Walls bloom with murals of fruit, festivals, and lovely tehuanas in their bright, flowery costumes, while patios are sprinkled with hammocks and sheltered overhead by luxurious handcrafted palapas. Saturday and Sunday afternoons 2–6 P.M., a marimba band will play “La Sandunga” to your heart’s content. After such a luscious introduction, the food, from a very recognizable menu of salads, soups, eggs, pastas, meats (including some game), fish, and fowl, is no less than you would expect. Get there from the plaza by walking two long blocks south along Juárez to Plaza Laborio. Turn left and walk one block to Callejon Leona Vicario on the left; the restaurant is on the uphill side of the street. Credit cards are not accepted.

Second choice goes to the good but more ordinarily picturesque restaurant at the Hotel Guiexhoba (Hwy. 190 Km 250.5, tel. 971/715-1710, 7:30 A.M.–10 P.M. daily, $5–12), across the river. The food, from a typical but tasty menu of breakfast (eggs and pancakes), lunch (hamburgers, soups, and stews), and dinner (meat, fish, fowl, and spaghetti), sometimes comes with a flaming crepe Suzette flourish. Credit cards are accepted.

Back downtown, for a restful comida, go to the singularly interesting Museum and Restaurant Xunashi (Callejon El Faro 1A, local cell tel. 971/129-7990, noon–5 P.M. daily).

INFORMATION AND SERVICES

Tourist Information

For travel recommendations and help in emergencies, go to the friendly Turismo office (on Hwy. 200 south, Salina Cruz direction, no phone, 9 A.M.–7 P.M. daily), overlooking the Río Tehuántepec, two blocks west and two blocks south of the town plaza, before the river bridge.

Health and Emergencies

A number of town pharmacies provide both over-the-counter remedies and prescription drugs. Perhaps the best stocked is the town-center branch of the Farmacia San Jorge (Romero, 8 A.M.–8 P.M. daily), located in a permanent street stall, right on Romero, on the market side of the town plaza.

If you need to consult a doctor, you can always find one at the big 24-hour Hospital Materno (Hwy. 190, tel. 971/713-7252) across from the bus station.

Alternatively, you have another highly recommended choice, Dr. José Manuel Vichido (Calle Ocampo, tel. 971/715-0862, 9 A.M.–2 P.M. Mon.–Sat.). From the plaza’s southeast corner, walk south one block along Juárez; turn left at the first street, Ocampo. The doctor’s office is half a block farther on the left.

Police service is available from at least two sources in Tehuántepec. Call either the policía municipal (tel. 971/713-7000), or the emergency number (dial 066).

Money

Tehuántepec has some banks, all with ATMs. On the plaza’s southeast side, go to up-and-coming Banorte (5 de Mayo, 971/715-0140, 9 A.M.–4 P.M. Mon.–Fri.) across from the market. Next door, also find Bancomer (5 de Mayo, tel. 971/715-1253, 8:30 A.M.–4 P.M. Mon.–Fri.).

Communications

Both the correo (at the plaza’s northeast corner, tel. 971/715-0106, 8 A.M.–4:30 P.M. Mon.–Fri., 8 A.M.–noon Sat.), including rapid, secure Mexpost service, and telecomunicaciones (at the plaza’s northeast corner, tel. 971/715-1197, 8 A.M.–5 P.M. Mon.–Fri., 9 A.M.–noon Sat. and Sun.), for money orders and public fax, stand side by side at the plaza’s northeast, Calle Hidalgo, corner.

Long-distance telephone, fax, and photocopies are available at Papelería La Esfera (at the plaza’s southeast corner, tel. 971/715-0042, fax 971/715-2090, 8 A.M.–8 P.M. Mon.–Sat., 9 A.M.–2 P.M. Sun.).

Find Internet access at Fusion (Hidalgo, no phone, 9 A.M.–10 P.M. daily), a short block north of the plaza, across from the little Juárez park.

GETTING THERE AND AWAY

By Bus

The vintage Tehuántepec bus station was supposed to be replaced years ago by a brand-new terminal, which remains yet unused. Meanwhile, on Highway 190-200, about a mile north of the town plaza, the old bus terminal (tel. 971/715-0108 for information and reservations for nearly all departures) still bustles with activity. Get there by taxi or motocarro (motorcycle mini-truck) from the plaza.

Four major bus lines, first-class Autobuses del Oriente (ADO) and Omnibus Cristóbal Colón (OCC), and mixed first- and second-class Sur and Autobuses Unidos (AU), offer many connections. Departures connect north and east via Juchitán with Tuxtepec, Villahermosa, Palenque, Minatitlán, Coatzacoalcos, Mérida, Cancún and Tulum; northwest with Oaxaca City, Puebla, and Mexico City; southwest with Salina Cruz, Bahías de Huatulco, Pochutla (Puerto Ángel), and Puerto Escondido; and east via Juchitán, Tuxtla Gutiérrez, San Cristóbal las Casas, and Tapachula at the Guatemala border.

See SCOOTING AROUND BY MOTOCARRO

In addition, from an adjacent terminal, a pair of independent second-class cooperating lines, Oaxaca Istmo and Fletes y Pasajes offer connections northwest with Oaxaca City and west with Bahías de Huatulco, Pochutla (Puerto Ángel), and Puerto Escondido, while Fletes y Pasajes also offers connections northwest with Oaxaca City, southwest with Salina Cruz, and northeast with Juchitán.

By Car

Good paved roads fan out from Tehuántepec in four directions. Highway 190-200 connects northeast with Juchitán (27 km/17 mi), then splits north as Highway 185 at La Ventosa and continues north, via Matías Romero and Minatitlán, all the way to the Gulf of Mexico at Coatzacoalcos, a total of 267 kilometers (166 mi). Allow about 4.5 driving hours, either way, for this relatively easy trip.

For Tuxtepec and northern Oaxaca, from cross-Isthmus Highway 185, turn onto Highway 147 at Matías Romero and continue northwest a total of 304 kilometers (189 mi) from Tehuántepec. Allow about five hours of driving time. Note: In the past, some robberies have occurred on the long (two-hour), lonely Highway 147 Matías Romero–Tuxtepec leg. Although security now appears to not be a problem, authorities still advise travelers to restrict their driving to daytime only on this stretch.

Highway 190 connects Tehuántepec northwest with Oaxaca City along 250 kilometers (155 mi) of well-maintained but winding highway. Allow about 5 hours in Oaxaca City direction (uphill), 4.5 hours in the opposite direction.

Highway 200 connects Tehuántepec west with the Oaxaca Pacific coast, via Salina Cruz (15 km/9 mi), Bahías de Huatulco (161 km/100 mi, three hours), Pochutla–Puerto Ángel (200 km/124 mi, four hours), and Puerto Escondido (274 km/170 mi, five hours) on paved, moderately traveled, secure highway.

Combined Highway 190-200 connects Tehuántepec east via Juchitán (27 km/17 mi) and Niltepec to Tapanatepec (126 km/78 mi) near the Chiapas border and beyond to Guatemala. Allow about 3.5 hours of driving time to Tapanatepec.

Drivers should fill up with gasoline at the Pemex gasolinera on the west side of the river, about two kilometers (1.2 mi) west of the bridge, where the road splits southwest to Salina Cruz, northwest to Oaxaca City.

EXCURSIONS WEST OF TEHUÁNTEPEC

The interesting destination trio of Guiengola, Jalapa del Marqués, and Tequisistlán can be combined into a full-day auto or taxi excursion (two days by bus) west of Tehuántepec. Along the way, enjoy a vigorous hike through pristine forest to the regal ruined fortress-city at Guiengola, a breezy boat ride on the Jalapa del Marqués reservoir, a soak in the community hot (actually just warm) spring, and a look at what is probably the world’s only marble basketball court, topped off by a stop by the marble factory at Tequisistlán.

Guiengola

The mountain fortress Guiengola (ghee-ayn-GOH-lah, Big Rock in Zapotec) may have been abandoned before the Spanish arrived, but it was never forgotten. Local people refer to it as the “old town” and sometimes hear eerie voices up there. If so, they rush down the mountain before dark.

Ghosts notwithstanding, an excursion to Guiengola is a chance to get some fresh air into your lungs as you enjoy the Isthmus tropical forest up close—fluttering butterflies, spiny cactus, flowery trees, and fireflies and hoot owls (if you return at dusk).

At the end of the rough jeep road that winds about six kilometers (four mi) up Guiengola Mountain, you continue on foot via a sometimes steep three-kilometer (two mi), one-hour hike through summer-green (but brown in spring) tropical woodland. If you start early or leave late, you might see venado (deer), javelin (wild pigs), and, if you’re very lucky, a león (mountain lion).

You know you’re getting close to the ruins when the trail straightens out and you see a continuous series of vegetation-covered mounds and walls on both sides. You are following an ancient, regal street, lined with ruined houses of the nobility. Next, break out into the open, where a four-step unreconstructed noble pyramid, called the Pyramid of the Sun, rises at the right. On the opposite side, across a spreading, flat ceremonial plaza, another, even taller, five-step Pyramid of the Moon stands on your left. To the extreme left rises a big ball court, so well preserved that it appears as if a dozen persons could spend a weekend with machetes and a few shovels and put the place in order for a tournament on Monday.

What you see immediately around you is only the ceremonial center. Beneath the surrounding forest are dozens of mounds, remains of temples, ceremonial patios, and regal homes. The state of preservation is exceptional, partly because of the site’s isolation. These structures of stone and mud mortar are delicate and mostly unexplored; please refrain from climbing on them.

GUIDES AND GETTING THERE

In Tehuántepec, you can pre-arrange a tour led by highly recommended guide Victor Velasquez Guzman (tel. 971/714-4060, local cell tel. 044-971/122-3966, vicveneno@hotmail.com), who lives on Calle Abasolo, four blocks north of the plaza, across Highway 190-200. Victor, who furnishes a translator for his tour, is highly recommended by both Tehuántepec Turismo and Julín Contreras, owner-operator of the Oasis hotel. Alternatively, either Julín (Melchor Ocampo 8, tel. 971/715-0008, fax 971/715-0835, www.hotelesdeoaxaca.com) or Tehuántepec Turismo (on Hwy. 200 south, Salina Cruz direction, no phone, 9 A.M.–7 P.M. daily) may be able to recommend someone else.

If, on the other hand, you lack prior arrangements, arrive early at the Guiengola jumping-off point (from Hwy. 190, about 16 km/10 mi northwest of Tehuántepec) by at least 9:30 A.M., to avoid the midday heat and give you time to possibly contact an on-site guide (not mandatory, but very useful), most likely either José Luis Toral Sánchez or Feliciano Gonzáles Mendez, whom the government has certified as official guardians of Guiengola. You may find one or both of them either at the roadside grocery Abarrotes Chayote, or at the uphill parking lot before the trail that leads to the ruins. Abarrotes Chayote and most of the highway-front palapas provide lunches (sometimes of armadillo, venison, iguana, coati, and other game), drinks, and bottled water (very necessary, since no water is available along the route). Once you’ve contacted your guide, you could either continue to Guiengola immediately or with extra time, detour with your guide to Jalapa del Marqués and Tequisistlán and return to explore Guiengola in the late afternoon.

By car, get there by driving your own (rugged pickup truck or jeep-like, high clearance) SUV or similar rental vehicle (expensive; contact rental agents in Oaxaca City, Salina Cruz, and Juchitán) to the signed (archaeological symbol) right turnoff that runs from the highway-front Abarrotes Chayote, about 16 kilometers (10 mi) west, Oaxaca City direction, along Highway 190 from Tehuántepec. Otherwise, get to the Highway 190 turnoff by sharing a taxi, or, most cheaply, via the Autotransportes Galgos de Jalapa buses, which leave the Tehuántepec parking lot, on Highway 190-200, across from town entry street 5 de Mayo, about every half hour. From the highway turnoff, get to the ruins by continuing by taxi or thumbing a ride (offer to pay) from a truck.

Jalapa del Marqués

During Mexico’s big dam boom in the 1950s, planners decided to conserve and control some of the trillions of gallons of water that flow via the Río Tehuántepec into the sea. A good idea, thought most, for flood control and irrigation during the long winter and spring drought.

The result is Benito Juárez dam and reservoir, which provides irrigation water, fish, and a tourist attraction for Jalapa del Marqués (pop. 3,000), the biggest town on the reservoir.

The cost for all this was that Jalapa del Marqués, originally on the bank of the Río Tehuántepec, had to be moved eight kilometers (five mi) uphill to its present location next to Highway 190, about 30 kilometers (18 mi) west of Tehuántepec. Now the people have everything new—wide paved streets, a church, and a small museum and Casa del Pueblo cultural center.

Jalapa del Marqués is ready for visitors, with a new hotel and a pair of good restaurants. Just inside the big town entrance gate, find Hotel Jalapa del Marqués (Corner Of Highway 190 and Calle Segunda Sur, at the big town entrance gate, tel. 995/721-2467, $18 d w/fan, $24 d a/c), built by the local pharmacist, who offers 10 clean, simply decorated rooms, with cable TV, above the pharmacy.

People in Jalapa del Marqués eat a lot of fish—specifically, mojarra (bass). A number of restaurants cook it up and serve it for visitors; for the best, go to Del Camino (Hwy. 190 Km 33, 8 A.M.–9 P.M. daily, $3–10, snacks 24 hours), on the Tehuántepec side, about a mile before town. Relax in their tranquil tropical patio setting as you choose from an extensive, professionally prepared and served menu. Or, alternatively, try the more modest Tecos (tel. 995/721-2619, 8 A.M.–7 P.M. daily), across the highway, a bit closer to town.

The next thing to do is to go fishing and/ or take a boat ride on the lake. This is good anytime of year but is best in the dry winter or spring, when the silt from the summer rains has settled and the lake is invitingly clear. Arrive early enough (say by noon) to find one of the boat workers down at the lake before they go home for the day. They charge about $20 for a two-hour ride or fishing trip. Bring your own pole, unless you want to fish by line or net as the locals do.

A popular excursion destination is Tres Picos, a Zapotec ruin on the far side of the lake. There, you can explore a trio of conical stone pyramids, about nine meters (30 ft) high, and a submerged ball court. Also, if the water is low and clear enough, perhaps your boatman will take you to see the site of the submerged old Jalapa del Marqués, where you’ll be able to see the old church beneath the water or even sit on its bell tower, which at low water protrudes from the lake’s surface.

Before or after your boat excursion, take a look inside the Casa del Pueblo, on the town plaza about 180 meters (600 ft) downhill from the highway. Besides a number of giant fossil bones, apparently mastodon, it has a sizable collection of locally gathered pre-conquest pottery, including some very phallic-looking figurines. At this writing, the dusty collection was under lock and key. However, if you go to the presidencia municipal (on the adjacent side of the plaza), you might find someone who will unlock the door for you.

Get to the plaza and the lakeshore boat landing by the paved main street, marked by a huge concrete Bienvenidos (welcome) portal on the highway. Drivers, mark your odometer. Continue downhill, to the Presidencia Municipal (0.2 km/0.1 mi), on the right, uphill plaza corner. Turn right and proceed counterclockwise around the central plaza, first passing the Casa del Pueblo, also on the right. On the opposite, downhill side of the plaza, turn right again, and continue around a traffic circle (0.6 km/0.4 mi); after another 2.2 kilometers (1.4 mi) mostly on a dirt road, you arrive at the beach and boat landing. Go swimming (in your bathing suit) and enjoy a lakeside picnic.

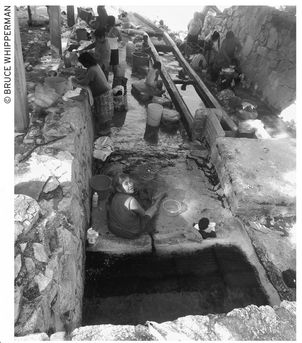

Finally, you might join the folks in the community agua caliente (warm spring) about one kilometer (0.6 mi) uphill from the highway. People begin arriving around six in the morning, when it’s cool. They bring their soap and clothes to be washed and stay for hours, playing in the concrete warm-water tank (hot tub warm, at 39°C/102°F). Wear your bathing suit. If you don’t have one, just go in with your clothes on like everyone else. Skinny-dipping, unless you’re under three, is liable to land you in jail, besides reinforcing the local people’s stereotypical view of the “loose” foreigner. Get there via the dirt street that heads uphill at the highway taxi stop, across from the blue clinical laboratory. After four blocks of walking, bear left at a fork. Soon on the left, in a small valley downhill, you’ll see the women washing clothes in big tanks inside a fenced enclosure (to keep animals out). The women are friendly and also careful to keep their waste water from the lower basins, where you’ll be welcome to bathe. (The basins outside the enclosure are for animals only.)

washing at the community agua caliente

By bus, get to Jalapa del Marqués via either the Tehuántepec central bus terminal or a second-class bus from the parking lot across the highway from the Tehuántepec town entrance street, Calle 5 de Mayo, by the market.

Tequisistlán

This little municipio, officially Santa María Magdalena Tequisistlán, was on ground too high to get gobbled up by the reservoir. Consequently, the huge-in-summer (and muddy) Río Tequisistlán continues to run right next to town. During the dry, hot spring this river appears very inviting for a dip into its clear, gurgling water.

Take a look inside the old church in the center of town. Here, folks enjoy the church’s completely marble-floored atrium in front, especially handy for dancing during the July 20–24 festival in honor of Santa María Magdalena. On the church’s side, you’ll find the kicker: probably the world’s only marble basketball court.

You can see the source of all this by going to the community marble factory (Empresa Comunal Industrial de Marmol y Onix, Hwy. 190, local cell tel. 044-995/101-8181, 8 A.M.–2 P.M. Mon.–Fri., 8–11:30 A.M. Sat.), about two kilometers (1.2 mi) west (Oaxaca City direction) of the town highway crossing. If you arrive during working hours, ask someone to “please show” (“favor de maestrar”) you around. You’ll see dozens of men and machines working beneath a shady open-air roof, cutting, grinding, and polishing dozens of beautiful pieces of marble and onyx.

In the factory office, feast your eyes on the beautifully polished finished products. They will custom-make most anything you want—such as the lovely marble bathroom vanity top you’ve always wanted, a statuesque marble cat, or some other favorite animal.

Get there by car, via Highway 190 (50 km/30 mi) in the Oaxaca City direction, or an hour by bus from the Tehuántepec bus terminal or parking lot. Get off at the Tequisistlán crossing and walk or taxi to the factory and/or the marble basketball court.

Juchitán and Vicinity

Isthmus people associate the name Juchitán with both the town, Juchitán de Zaragoza, and the governmental district that it heads—a domain larger in extent than either the Distrito Federal or each of the four smallest Mexican states. The district of Juchitán (Place of Flowers) ranges from the Chimalapa, the roadless jungle refuge of dozens of Mexico’s endangered species, south to the warm Pacific and the rich lagoons that border it.

But like any empire, Juchitán is the sum of its small parts—hidden slices of Mexico that few outsiders know, from the crystalline springs of Tlacotepec and Laollaga to the seemingly endless groves of the “world mango capital” at Zanatepec and the vibrant market and near-continuous community festivals—velas—of busy, prosperous Juchitán de Zaragoza.

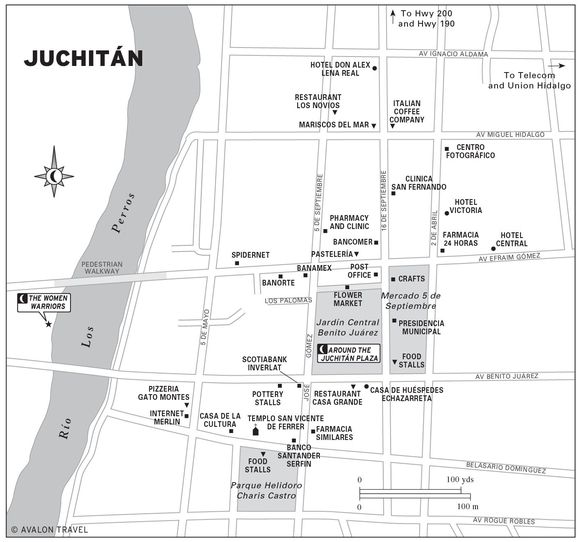

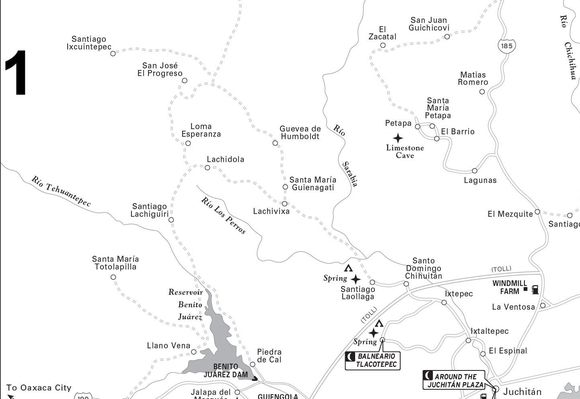

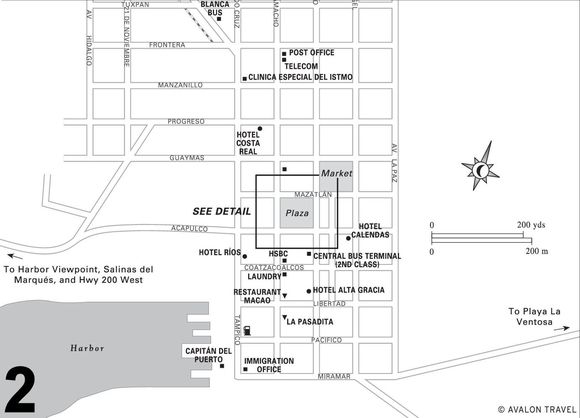

Orientation

Juchitán (pop. 80,000) bustles with commerce all the daylight and early-evening hours. Main streets 16 de Septiembre and 5 de Septiembre steadily conduct a double stream of traffic to and from the north-side Highway 200 crossing. A few blocks to the west, the Río Los Perros (River of the Dogs, for the otters that hunt fish in the river) courses lazily southward, marking downtown Juchitán’s western boundary. Traffic focuses about two kilometers (1.2 mi) south of the highway at the town plaza, the Jardín Central Benito Juárez, the town’s commercial and governmental nucleus. On Calle 16 de Septiembre, on the plaza’s east side, the long white classical arcade of the palacio municipal fills the entire block, from Calle Efrain Gómez bordering the plaza’s north edge to Calle Benito Juárez on the south. Governmental offices occupy the upper floor of the palacio municipal, while businesses, crafts booths, and food stalls spread across the bottom. Behind the facade, taking up the entire city block east of the plaza, is the town market, Mercado 5 de Septiembre.

SIGHTS

Around the Juchitán Plaza

Around the Juchitán Plaza

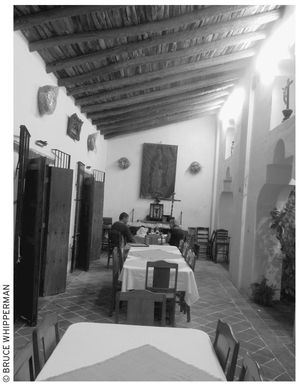

A fun spot to start off (or end) your day exploring Juchitán is at a table in the graceful old-Mexico patio of Restaurant Casa Grande (Calle Benito Juárez, 7 A.M.–11 P.M. daily) on the plaza’s south side. Here, a hearty breakfast or a cool lunch will invigorate you for yet another few hours of relaxed plaza sightseeing.

Stroll out and admire the fine busts of Benito Juárez on the plaza’s east side and Margarita Maza, his wife, on the west side, by Calle 5 de Septiembre. On the plaza’s north side, find the Monument to the Battle of September 5, 1866, where a Mexican eagle and a heroic Benito Juárez commemorate the victory of the ragtag local battalion over a superior French imperial force.

Step east, across Calle 16 de Septiembre, to the crafts stalls beneath the northerly (left) half of the presidencia municipal arcade. What you don’t find downstairs you’ll find in an upstairs market foyer. Stroll the aisles and choose from a host of excellent items customarily including, besides the famous Isthmus embroidered skirts and blouses, handwoven hamacas (hammocks); leather huaraches and bolsas (purses); woven palm tenates and reed canastas (baskets), petates (mats), and sombreros; and gold-filigree joyería (jewelry). You can also find much of the same (besides a riot of flowers) at many of the stalls that line the plaza’s north end.

For pottery, walk west along Calle Benito Juárez (which borders the plaza’s south side) to the block just west of the plaza. There, along the old town church’s rear wall, a lineup of stalls offers an assortment of ceramics, mostly practical traditional housewares, from huge round red ollas (jars) and flat comales (griddles) to brightly painted piggy banks and flower vases.

Templo de San Vicente Ferrer and Casa de la Cultura

While you’re in the vicinity, visit the town’s pride, the San Vicente Ferrer church. Reach it by circling the block: Continue west on Calle Benito Juárez, go immediately left at 5 de Mayo, then after one block turn left again at Belisario Domínguez, to the church on the left. Although the church’s early history is shrouded in mystery, the present construction appears by its style to date from the mid-19th century. Its dedication to San Vicente Ferrer, patron of survivors of the sea, appears connected to Juchitán’s original founding as a refuge for survivors, perhaps of some ocean disaster, such as a terrible tsunami or hurricane, some time shortly before the conquest. Present-day Juchitecos, inheritors of their patron’s zeal and ferocity, celebrate his memory with gusto to match, with no less than eight consecutive velas, beginning on the first Saturday of the last 15 days of May.

Across the street from the church, you might linger for a few minutes in the shady side plaza, Parque Helidoro Charis Castro. Here stands the bronze bust of Castro, the beloved Juchitecan maderista general who led the 13th Juchitecan Battalion in its bloody, but ultimately successful, revolt against dictatorial forces, from 1910 to 1914.

Afterward, look around inside the Casa de la Cultura (tel. 971/711-4589, casacult_istmo5@hotmail.com, 9 A.M.–2 P.M. and 5–8 P.M. Mon.–Fri., 9 A.M.–2 P.M. Sat.), next door, west of the church. The building, originally a Catholic school, became the Casa de la Cultura in 1972 through the efforts of celebrated Oaxaca painter Francisco Toledo. Rooms around the graceful, old-Mexico patio accommodate a café, a small archaeological museum, an art exposition gallery, and a children’s library. The reception staff sells a few Spanish-language books of local history and folklore and folk music CDs.

The Women Warriors

The Women Warriors

As an interesting downtown side-street diversion, cross over the Río Los Perros for a look at the intriguing Women Warriors sculptures on the west riverbank. Head west along Calle Benito Juárez. Two blocks west of the plaza, from the middle of the river bridge, notice the two tall sculptures of women (in Juchiteca skirts and blouses, of course), about two stories high, in what appears to be a small neighborhood park.

Few local residents seem to know much about them, except that “they are guarding the people from the river.” (Although one person did tell me that they were erected by noted sculptor and lover of Juchitán, Miguel Urban.) Get a better view of the sculptures (which, close-up, you’ll see are of stainless sheet steel) by accessing the west riverbank from the pedestrian bridge a block upstream (north) from Benito Juárez.

The riverbank is especially pleasant around sunset, when, standing on the Benito Juárez bridge, you might catch a cooling breeze, enjoy the sky colors, and be entertained by the flocks of black grackles flying overhead and scrapping and cackling in riverbank trees as they settle down for the night.

ACCOMMODATIONS

Under $25

For a good downtown budget option, check out the 27-room Hotel Victoria (2 de Abril 29, tel. 971/711-1558, $17 s or d one bed, $19 d two beds with fan; add $5 for a/c) a block east and a block north of the town plaza’s northeast corner. What you see is what you get: plain but clean rooms with private, hot-water shower-baths. It’s best to arrive by early afternoon or book this hotel, a popular overnight for market vendors, a day in advance.

$25–50

Moving two blocks north from the plaza along 5 de Septiembre, past Miguel Hidalgo, you’ll find the welcoming Hotel Don Alex Lena Real (16 de Septiembre 48, tel. 971/711-1064 or 971/711-0989, fax 971/711-1064, hote-donalex@hotmail.com, $34 s, $40 d). The 14 very clean rooms with a choice of one king-size or a pair of double beds, come with air-conditioning, phone, cable TV, wireless Internet, and credit cards accepted.

Continuing north, about five blocks from the plaza, find the Hotel Don Alex’s sister hotel, the semi-deluxe Hotel López Lena Palace (16 de Septiembre 70, tel. 971/711-1388, fax 971/711-1389, hotellopezlena_reservaciones@hotmail.es, www.hotelesdeoaxaca.com, $40 s, $50 d, $60 t). Builders have included a modicum of extras, such as potted plants, airy staircases, and light, rose-tinted hallways, into the four-story building. The 40 comfortable rooms are tiled, very clean, and attractively decorated. Amenities include cable TV, wireless Internet, phones, air-conditioning, a bar, and a reliable restaurant; credit cards are accepted.

Over $50

Juchitán’s most relaxing hotel is the resort-style  Gran Hotel Santo Domingo (Crucero, Hwy. 200, tel./fax 971/711-1050, 971/711-3642, or 971/711-1959, hsto@prodigy.net.mx, www.hotelesdeoaxaca.com, $38 s, $52 d, $65 t), on the highway across from both the bus station and the ingress road to town. The Gran Hotel’s choice attraction is an invitingly large and luxurious pool and grassy patio, a welcome refuge for winding down from the heat and bustle. The approximately 60 rooms in a pair of long, double-storied tiers beyond a tropical entrance foyer, are spare but clean, spacious, high-ceilinged, and comfortable, with modern-standard bathrooms, air-conditioning, TV, phones, a good restaurant, parking, and credit cards accepted.

Gran Hotel Santo Domingo (Crucero, Hwy. 200, tel./fax 971/711-1050, 971/711-3642, or 971/711-1959, hsto@prodigy.net.mx, www.hotelesdeoaxaca.com, $38 s, $52 d, $65 t), on the highway across from both the bus station and the ingress road to town. The Gran Hotel’s choice attraction is an invitingly large and luxurious pool and grassy patio, a welcome refuge for winding down from the heat and bustle. The approximately 60 rooms in a pair of long, double-storied tiers beyond a tropical entrance foyer, are spare but clean, spacious, high-ceilinged, and comfortable, with modern-standard bathrooms, air-conditioning, TV, phones, a good restaurant, parking, and credit cards accepted.

FOOD

Juchitán’s downtown plaza food stalls do big business all day and half the night. Especially popular with local people are the market fondas (food stalls) at the bottom level, at the south (right) side of the palacio municipal. Another, more tranquil fonda spot is on the side plaza Helidoro Charis Castro, a block south of the main plaza, in front of the San Vicente Ferrer church.

Try the freshly baked offerings of the Panadería Internacional (Efraim Góez, between 8 de Septiembre and 16 de. Septiembre, 9 A.M.–9 P.M. Mon.–Sat., 9 A.M.–3 P.M. Sun.), half a block north of the plaza.

For a snack (sandwich, pizza, salad) and delicious espresso coffee there is soft-seat, 21st-century hip Italian Coffee Company (corner of 15 de Septiembre and Hidalgo, tel. 971/711-0773, 9 A.M.–10 P.M. daily, $2–5).

The pizza is hot, the spaghetti is tasty, and the salads are crisp at the Pizzería Gato Montes (Wildcat Pizza; Colón 7, tel. 971/711-3945, 5 P.M.–midnight daily, $3–9). Add movies (starting around 7 P.M.) and your evening will be complete. It’s located a block west of the San Vicente Ferrer church, between Belisario Domínguez and Juárez.

See VELAS: FIESTAS OF THE ISTHMUS

The class-act plaza-front restaurant, fine for a midday break, is the refined  Restaurant Casa Grande (Benito Juárez 12, tel. 971/711-3460, 7 A.M.–11 P.M. daily, $6–12) in the inner patio of an ex-mansion. The mostly business and upper-class patrons choose from an international menu of soups, salads, sandwiches, meats, and pastas, and a number of Oaxacan regional specialties, such as pechuga de pollo zapoteca (breast of chicken, Zapotec style), enchiladas de mole negro (enchiladas with black mole sauce), and chile relleno de picadillo (chili pepper stuffed with spiced meat); credit cards are accepted.

Restaurant Casa Grande (Benito Juárez 12, tel. 971/711-3460, 7 A.M.–11 P.M. daily, $6–12) in the inner patio of an ex-mansion. The mostly business and upper-class patrons choose from an international menu of soups, salads, sandwiches, meats, and pastas, and a number of Oaxacan regional specialties, such as pechuga de pollo zapoteca (breast of chicken, Zapotec style), enchiladas de mole negro (enchiladas with black mole sauce), and chile relleno de picadillo (chili pepper stuffed with spiced meat); credit cards are accepted.

On the other hand, local fish lovers frequent seafood restaurant Mariscos del Mar (corner of 16 de Septiembre and Hidalgo, no phone, 8:30 A.M.–7 P.M. daily, $3–8), one block north of the plaza, for its long, very correctly Mexican menu of seafood and more. Have it all, including a plethora of clam, oyster, and shrimp cocktails; seafood soups, both clear and creamed; fish, octopus, squid, lobster, and shrimp (cooked 10 ways); and seven styles of cucarachas (small prawns).

For good food in a Mexican Bohemian–style atmosphere, check out Restaurant Los Novios (The Sweethearts; 5 de Septiembre, tel. 971/712-0555, 7:30 A.M.–5:30 P.M. daily, $4–6), on a block north of the plaza, just past the corner of Hidalgo. Amidst a colorful gallery of the owners’ new-Impressionist-mode art, select from an innovative menu of breakfasts (freshly squeezed orange juice and hotcakes with bacon), spaghetti, and fowl (breast of chicken with chipotle sauce).

Alternatively, escape temporarily from Mexico to the coffee shop–style Restaurant Santa Fe (Hwy. 200, tel. 971/711-1545, 7 A.M.–midnight daily, $4–10), at the Highway 200 crossing, across from the Gran Hotel Santo Domingo. In the air-conditioned 1970s-mod atmosphere, enjoy fresh coffee and fruit, followed by tasty eggs, waffles, or pancakes for breakfast; several hamburgers and salads for lunch; and, finally, soups, spaghetti, beef, chicken, and fish for dinner. Credit cards are accepted.

FESTIVALS AND ENTERTAINMENT

Juchitán’s substantial excess wealth goes largely to finance an impressive round of parties, locally called velas, in honor of a patron saint or a historically or commercially important event. The velas are organized and financed by entire barrios, and led by mayordomos, usually a well-to-do male head of household, but also including his spouse, children, and all relatives and friends, who usually add up to a major fraction of the population of an entire Juchitán barrio. The mayordomo family, together with male and female capitanes and their closest friends, make up the mayordomía, the core committee responsible for carrying off the celebration.

Customary activities include blossom-decorated church masses, parties in the house of the mayordomo, community barbecues, a parade of fruit and flower-laden floats, from which the capitanas, dressed like brides in their stunningly embroidered Tehuántepec outfits, throw fruit and gifts to the street-side crowds.

(Note: Although the velas are local affairs, everyone is invited, and can join the fun by paying a nominal entrance fee, customarily $5–10 per adult.)

In all, Juchitecos celebrate 20 in-town velas, which fill streets with merrymakers during the last half of April, virtually the entire month of May, and several days each in June, July, August, and September—a total of about 50 days of celebrating for the entire year. This wouldn’t be too excessive if it were not for the approximately 20 obligatory national holidays and the other 30 not-to-be-missed velas in neighboring Isthmus communities.

Local folks sometimes offer droll commentaries about all this celebrating: “If you go to a mayordomo house, I’ll tell you what you’ll find…no bed, no stove, no shoes, just happy people and lots of friends.”

Lacking a local fiesta, you might want to take in a film at the genteel art Cinema Casa Grande (on the plaza, south side, tel. 971-711/0980, mid- to late afternoons Tues.–Sun.). Enter past the patio Restaurant Casa Grande (Benito Juárez 12). Or, alternatively, check out the evening entertainment, beginning around 7 P.M., at the Pizzería Gato Montes (Wildcat Pizza; Colón 7, tel. 971/711-3945, 5 P.M.–midnight).

As much a night club as it is a restaurant, the Restaurant-Bar Las Galias (Efrain Gómez 15B, dinner entrées $9–12) entertains guests with live Latin music, after 9 P.M. Friday and Saturday nights. Arrive early for fish, chicken, or a good steak, then dance the night away.

INFORMATION AND SERVICES

Tourist Information

The most reliable local government tourism office is in Tehuántepec: Turismo office (on Hwy. 200 south, Salina Cruz direction, no phone, 9 A.M.–7 P.M. daily), overlooking the Río Tehuántepec, two blocks west and two blocks south of the town plaza, before the river bridge.

Alternatively, in Juchitán, try travel agent Zarymar (5 de Septiembre 100B, tel. 971/711-2867), several blocks north of the plaza, for information, airline tickets, and car rentals.

Health and Emergencies

A ready source ofnonprescription medicines and drugs is the 24-hour Farmacia 24 Horas (corner of Efrain Gómez and 2 de Abril, tel. 971/711-0316), one block behind the north side of the presidencia municipal. Alternatively, go to Farmacia Similares (José F. Gomes, at the corner of 5 de Septiembre, tel. 971/711-3126, 9 A.M.–10 P.M. daily), a block south of the plaza’s southwest corner.

A number of doctors maintain offices near the plaza. For example, general physician–sur-geons Dr. Ruben Calvo López and Dr. Carlos Alonso Ruiz and gynecologist Doctora Anabel López Ruiz hold regular consulting hours at Clínica San Fernando (16 de Septiembre, between Efrain Gómez and Hidalgo, tel. 971/711-1569), half a block north of the plaza’s northeast corner.

Alternatively, go to the Clínica Nuestra Señora de Exaltación (5 de Septiembre, east side, tel. 971/711-0204), with a very professional pharmacy, half a block north of the plaza. Here, general practitioner Doctor Guillermo Gonzales and gynecologist Doctora Catalina Martínez partner with several other medical specialists on call.

In a medical emergency, follow your hotel’s recommendation or hire a taxi to the General Hospital Dr. Macedonio Benítez Fuentes (Efrain Gómez, tel. 971/711-1441 or 971/711-1985), downtown, near the plaza.

In case of police or fire emergency, dial 066, the public crisis number.

Money

A number of downtown banks, which all have ATMs, help manage Juchitecos’ money. They’ll also change your money into pesos or U.S. dollars. A good bet is Banorte (Efrain Gómez 19, tel. 971/711-1160 or 971/711-3482, 9 A.M.–4 P.M. Mon.–Fri., 10 A.M.–2 P.M. Sat.), half a block west of the plaza’s northwest corner. Second choice goes to Banco Santander Serfin (corner of Belasario Domínguez and José F. Gomes, tel./fax 971/711-2000, 9 A.M.–4 P.M. Mon.–Fri.), a block south of the plaza.

Communications

The correo (tel. 971/711-1272, 8 A.M.–7 P.M. Mon.–Fri., 9 A.M.–noon Sat.) is at the plaza’s northeast corner, just west of the presidencia municipal. For a public fax or a money order, go to the telecomunicaciones (on Aldama, four blocks west of 16 de Septiembre, 8 A.M.–7 P.M. Mon.–Fri., 9 A.M.–noon Sat.).

Internet access is available at Spider Net (Efrain Gómez, no phone, 9 A.M.–10 P.M. daily), a few doors east of 5 de Mayo.

GETTING THERE AND AWAY

By Bus

A modern long-distance camionera central (central bus station), at the Highway 190-200 crossing north of downtown, is the point of departure for all of the first-class and most of the second-class bus connections with both Oaxaca and national destinations. First- and second-class lines service customers from separate waiting rooms (first-class on the left, second-class on the right). The busy but clean station has snack stores and luggage-check service. Long-distance telephone and fax is available at a small office in the second-class waiting room.

Autobuses del Oriente (ADO; tel. 971/711-2565 or 971/711-1022) and affiliated lines offer direct first-class connections north with Gulf of Mexico destinations Minatitlán, Coatzacoalcos, Villahermosa, Palenque, Merida, Cancun, and Tulum; and northwest with Oaxaca City, Mexico City, Veracruz, and Tampico. Additionally, first-class carrier Omnibus Cristóbal Colón (OCC; tel. 971/711-2565) and its luxury-class subsidiary, Plus, offer connections northwest with Oaxaca City, Puebla, Mexico City, and Veracruz; southwest with Salina Cruz, Bahías de Huatulco, Pochutla (Puerto Ángel), and Puerto Escondido; and east with Chiapas destinations of Tuxtla Gutiérrez, San Cristóbal las Casas, and Tapachula, at the Guatemala border.

Second-class carriers include Autobuses del Oriente (ADO), which offers connections north with Coatzacoalcos; southwest with Tehuántepec and Salina Cruz; and east with Tapanatepec, including all intermediate destinations. Additionally, Autobuses Unidos (AU) offers second-class connections northwest with Tuxtepec, Puebla, Mexico City, Orizaba, and Veracruz; and southwest with Tehuántepec and Salina Cruz, including many intermediate destinations. Moreover, Sur offers second-class connections north with Coatzacoalcos; northwest with Oaxaca City; southwest with Bahías de Huatulco; and east with Tapanatepec and Tapachula, including intermediate destinations.

Semi-local bus connections with adjacent towns are available via the Autotransportes Istmeños buses across the side street, south, less than a block toward town from the camionera central.

Mostly second-class Fletes y Pasajes buses operate out of a separate terminal, also at the Highway 190-200 crossing but on the west side, adjacent to the Restaurant Santa Fe. Buses connect east with Chiapas destinations of Tuxtla Gutiérrez, Tapachula, and the Guatemala border; northwest, with Oaxaca City, Puebla, and Mexico City; and north with Tuxtepec and Minatitlán.

By Car

Drivers have the same highway choices and destinations as they do for Tehuántepec. Simply subtract 30 minutes driving time (and 27 km/17 mi distance) for northerly and easterly trips; and add the same for northwesterly and southwesterly trips. In Juchitán, fill up with gasoline at the Pemex gasolinera at the Highway 190-200 town ingress crossing, next to the bus station.

North of Juchitán

A number of uniquely interesting destinations await travelers willing to venture into the foothill hinterland northwest and north of Juchitán. Foremost among them are the storied former royal Zapotec bathing springs that well up, blue and crystalline, at Tlacotepec and Laollaga, an hour’s travel northwest of Juchitán.

Equally ripe for exploring is the stalactite-studded limestone cave near the town of Santo Domingo Petapa, together with the singularly successful cooperative company town at Lagunas, about 1.5 hours north of Juchitán.

Each of these excursions can be enjoyed from Juchitán in a leisurely day by car or a long day by bus.

THE SPRINGS AT TLACOTEPEC AND LAOLLAGA

Both of these bathing resorts were part of the territory of the Zapotec royal family of King Cosijoeza. He often used the springs as a refuge during his protracted war with Aztec emperor Ahuitzotl during the 1490s. A famous traditional story recounts how love resolved the bloody conflict. Tiring of the struggle, Ahuitzotl proposed a peace pact. In exchange for allowing Aztec traders and envoys to pass through the Isthmus lands, Cosijoeza would receive Aztec princess Coyollicatzin in marriage. One day, meditating over the proposition while bathing in the Tlacotepec spring, Cosijoeza was awestruck by a stunning apparition of Coyollicatzin. Despite his apprehension, Coyollicatzin’s apparition enchanted him with her beauty. Thus persuaded, Cosijoeza soon took Coyollicatzin in marriage, sealing the pact between the two nations.

Their marriage was a happy one. Children resulted, and Cosijoeza passed the springs at Tlacotepec and Laollaga to their son Cosijopí, the king of the Isthmus lands, and their daughter, Princess Donaji, both of whom continued to exercise authority after the conquest.

Balneario Tlacotepec

Balneario Tlacotepec

Storied Princess Donaji, who after the conquest was baptized as Magdalena Donaji, donated both her Christian name and the springs and royal park at Tlacotepec to the local community, still known as Magdalena Tlacotepec.

Today, the town’s springs and surrounding sanctuary are a unique asset for all istmeño families to enjoy, which they do en masse on sunny Sundays and holidays. The source, a clear, cool underground river, wells up from a rocky basin and fills a long, meandering, aqua-blue swimming hole. Shoals of little fish that nibble and tickle your feet hide in crannies and flit along the sandy bottom. Shady mango trees overhang the bank and spread over a rustic public strolling ground on one side. On the other, the entrance side, food stalls surround a parking area.

Here you can park your (self-contained) trailer or RV or set up a tent and stay a spell, walking into the surrounding hills in the morning to enjoy wildlife and wildflowers and splashing in the cool spring in the afternoons. Custodial personnel, who keep the site clean and secure, collect nominal fees for parking and camping.

Balneario Tlacotepec, once a playground for the Tehuántepec nobility

Santiago Laollaga

Laollaga (lah-oh-YAH-gah) springs mark the northern boundary of the petite municipio of Santiago Laollaga, which you pass through on your way to the springs. A big parking lot overlooks the main series of pools (concrete basins) built into the rocky downhill channel of the Río Laollaga. Shady trees overhang the pools, and a pair of permanent open-air comedores on the riverbank serve drinks and food.

Visitors equipped with a self-contained trailer or RV might enjoy a stay, parking in the lot for a day or two. Fees run only a few dollars a day. Unfortunately, the water at the main pools is sometimes a bit tainted by soap from folks washing clothes upstream. You can assure pure water by following the river 0.5 kilometers (0.3 mi) upstream to its source, a natural ojo de agua spring welling from the base of the hills. Here, great shady trees spread over a sandy riverbank, ripe for tent camping if you don’t mind sharing the spot with a few townsfolk on weekdays, and more on weekends.

Laollaga diversions might include strolls around the town and along dirt roads and trails, into the summer-lush native tropical woodlands. By local bus or car, you could explore farther afield, along the good gravel road (at the northeast corner of town, where you made your last turn left) threading the green-forested Río Los Perros valley and foothill country 25 kilometers (15 mi) northwest to remote Santa María Guienagati.

Arrive during the last 10 days in July and join Laollaga’s big Fiesta de Santiago Apóstol (July 20–30), which includes four separate velas, with fireworks, carnival rides and games, regada (fruit-throwing), dances, and mojigangos (giant dancing figures).

Small town stores can supply basic groceries. Pharmacies, a private doctor, a centro de salud, a post office, and a caseta larga distancia can provide essential services.

Getting There

Get to Tlacotepec and Laollaga from Juchitán via Ixtepec, half an hour north of Juchitán. The easiest and cheapest way to go is by one of the Ixtepec-labeled local buses that frequently head north from the Highway 190 crossing in Juchitán, across the street from the main bus station and the gas station. Half an hour later, at Ixtepec, transfer to the blue-and-white Tlacotepec- or Laollaga-labeled local bus.

It’s more complicated, but possible, to make your way by car. From the Highway 190-200 crossing at Juchitán, mark your odometer and head north across Highway 190-200, continuing through Ixtaltepec (eight km/five mi) to the railroad tracks at Ixtepec (15.6 km/9.7 mi). Immediately after crossing the tracks, turn left. After one block, turn right at Ixtepec’s main street, Calle 16 de Septiembre. Continue five blocks (0.5 km/0.3 mi) and turn left (west) at Galeana (16.1 km/10 mi). Continue west; follow the curve right after about a mile, then after two blocks, at the police post on the right, curve left. Continue about another mile, and at a Y-intersection (19.2 km/11.9 mi) go left and continue, following the Balneario signs to the Tlacotepec springs, a total of about 29 kilometers (18 mi).

Alternatively, for Laollaga, bear right at the abovementioned Y intersection and continue through Chihuitán (turn left at the village corner, at 26.1 km/16.2 mi) to Santiago Laollaga village center (31 km/19.2 mi). Turn right and continue a block, pass over a bridge, and, a block or two farther, at the presidencia municipal, turn left. Continue half a mile to the Ojo de Agua sign, turn left and continue to the balneario entrance after about three blocks. If you get lost, ask a shopkeeper (or point to this in your guide): “¿Donde está El Balneario Laollaga?” (dohn-DAY ays-TAH AYL bal-nee-AH-reeoh lah-oh-YAH-gah?). “Where is the Balneario Laollaga?”

LAGUNAS: COMPANY TOWN

If success can be measured by longevity, the industrial cooperative town of Lagunas, which began producing cement in 1942, has earned its plaudits. Moreover, the unique experiment it represents seems as robust as ever. The idea began back in the 1930s, when investors were eager to exploit a mountain of local limestone that towered conveniently beside the cross-isthmus rail line. The era was, however, that of reformist President Lázaro Cárdenas, when the star of socialism was rising over Mexico from the east. The enterprise must be a cooperative, the government demanded. Investors, realizing the project’s unique prospects, agreed, and Cruz Azul, a uniquely Mexican private-public cooperative, was born.

Today, the great mill beside the railroad tracks hums all day and night, producing millions of tons of cement yearly for projects from Chile to Canada. Moreover, besides supporting the livelihoods of thousands of families in the entire local hinterland, the Lagunas mill (judging from the tidy, dust-free town) appears to produce little of the cement dust that has debilitated cement-mill workers, especially in third-world countries, all over the globe.

At the town center, across the tracks from the mill, a monument erected by the workers (the Cooperadores de La Cruz Azul) honors Guillermo Alvarez, Cruz Azul’s guiding light, with a pair of eternally flickering electric lamps.

Along Avenida Cooperativismo, facing the plant stand the town Banamex branch, the correo, telecomunicaciones, and the plant superintendent’s office. Badged workers, all in pressed khakis and hard hats, walk with purpose along the sidewalks. Some turn and continue along the town’s main street, Avenida Cruz Azul, and continue past the hamburger shop, centro comercial (company store), an immaculate bakery, and the big church, dedicated to the Virgin of Guadalupe. From the commercial center, tree-lined residential streets extend past schools, a hospital, and tidy concrete houses with some of Mexico’s rare, American-style unfenced yards with lawns.

SANTO DOMINGO PETAPA: LIMESTONE CAVE

Several miles past Lagunas, Santo Domingo Petapa (pop. 2,000) marks the end of the pavement. Unless you arrive during a national holiday or the August 1–4 town festival in honor of Santo Domingo, Petapa will appear as a typical sleepy Oaxaca country town. Petapa does have, however, at least one claim to fame, and that is the grand limestone cavern on the mountainside three kilometers (two mi) beyond the town.

You will need both local permission and a local guide. The most highly recommended is locally experienced Ismael Juárez.