Armistice Decoration on White Cross Mill Chimney, 1918. (LCM)

The outbreak of peace was quietly anticipated in Lancaster by the start of November 1918. The press had reported on 2 November that ‘The Hun Tide recedes’ and on 9 November the chairman of the Lonsdale Appeal Tribunal looked forward to the diminution of work resulting from the request of several enemies for an armistice. The somewhat muted coverage of the press can perhaps be explained by the fact that the signing of the armistice was accompanied by an influenza epidemic. In October there had been fifty deaths attributed to influenza, with attempts made to maintain morale and avoid panic, for example, by closing schools and disinfecting public places of entertainment.

On 11 November, speaking at an impromptu meeting outside the Town Hall, Mayor Briggs spoke to the cheering crowds:

I am delighted to announce that an armistice has been signed this morning at 5 o’clock, and that hostilities were to cease at 11 o’clock. (Cheers). Thus ends the greatest war of any age in a victory of Right over Might. (Renewed cheers.) Our hearts are overflowing with joy at the good news, and we have the right to rejoice, but let us not in the midst of our rejoicings forget those who have laid down their lives to help to win this war, and who have not laid them down in vain. (Cheers.)

The influenza pandemic which broke out in 1918 affected c. 500 million people; 3 to 5 per cent of the world’s population were killed. The Lancaster Guardian of 2 November reported the Mayor’s expression of condolence at the losses to influenza: he mentioned specifically Mr Patterson, a Corporation official, who had lost his 11-year-old son and then ‘within a day or two, also his Wife’.

Armistice Decoration on White Cross Mill Chimney, 1918. (LCM)

The remainder of the day was observed as a general holiday. Services of thanksgiving followed. Local traders were quick to claim their place in the celebrations: the optician W.J. Hine (34 New Street) suggesting to the readers of the Lancaster Guardian that ‘the only way to have peace in your sight, and comfort too, is to have properly made Spectacles or Eyeglasses.’

The press described how the ‘thoroughfares were a blaze of colour with the hoisting of flags and banners, the Union Jack predominating. Sirens at the principal works were sounded, the church bells rang, and the streets were thronged by jubilant town people the majority of whom wore Union Jacks or brandished small flags.’ The band of the 2nd Battalion, King’s Own Royal Lancaster Regiment, with a detachment of troops, paraded the town, playing lively airs, and attracted several thousands of people to Dalton Square, the location of the Town Hall. At the same time, however, attention was turning to ‘how we are to settle down comfortably and sensibly after the War’ and rejoicing from the outset was combined with remembrance for the military war dead.

Float depicting ‘Peace & Harmony’.(LCM)

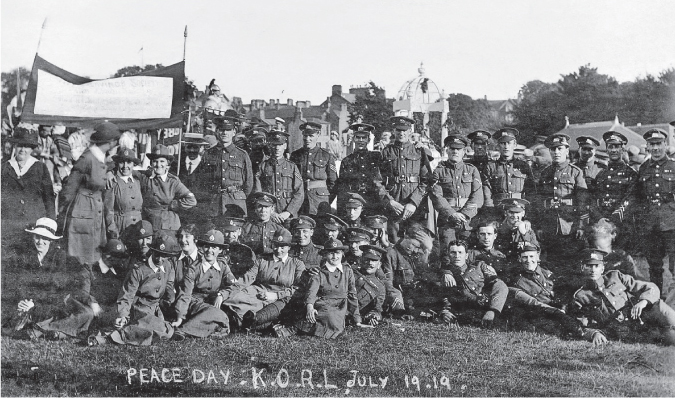

Peace Day, Lancaster, 19 July 1919, showing uniformed men and women at the event. (KOM)

Although the armistice ended the fighting, the war was not brought to a formal conclusion until the signing of the peace treaties in 1919. In response, Lancaster held its Peace Celebrations complete with procession of floats representing all the major contributors to the war, a special medal presented to all school children and culminating in a rousing rendition of ‘Rule Britannia’ at the Giant Axe field.

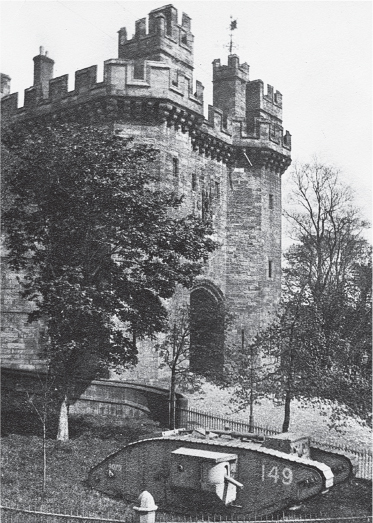

The Presentation Tank standing outside of Lancaster Castle and the John O’Gaunt Gate. (LCM)

A wide variety of local communities including church congregations, employers, schools and clubs displayed rolls of honour or plaques to their members. Most of these still remain. One exception is the presentation tank, Mark IV, which had stood on Castle Park from April 1920 in recognition of the contribution made by the town in War Bonds and Saving certificates: over £250,000.

The greatest challenge was how to commemorate the men who would never return, given that their graves were dispersed across the globe. Some of Lancaster’s war dead are commemorated multiple times at their places of work, worship and play. T. Bulmer & Co.’s History, Topography and Directory of Lancaster and District, published in 1912, lists twenty-seven churches, and nineteen academies and schools in Lancaster: these buildings came to house many of the local memorials. Other individuals may not be commemorated, notably men who died of war-related injuries after the unveiling of the war memorial and the men killed at the White Lund in October 1917, although Firth Dole, a works fireman killed in the fire, is listed in the Rolls of Honour in Nelson. Memorials to individuals had already been erected during the course of the war, although private shrines within houses have left little evidence outside such artefacts as crafted stands for the ‘Dead Man’s Penny’, the memorial plaque issued to next-of-kin from 1919. For some, death could never be accepted. John Griffin was killed on 25 September 1915, one of Lancaster’s worst days of the war. His great niece recalled how:

My nana’s brother John Griffin (Charles St, Lancaster) was in the Seaforth Highlanders he was killed … at age 20 years. When his mum died, my great nana, it was discovered that she had kept all his clothes for years as she never gave up hope that he would one day return home. There was no closure because there was no body.

Private Joseph Thompson’s gravestone, Scotforth Cemetery. The inscription ‘His precious life he gave’ parallels the sacrifice of Jesus Christ with that of the soldier. (CPB)

Even though the bodies of the fallen were not brought home, some were still included on the family grave stone. Private Joseph Thompson, ‘Dear Joe’, served with the Sherwood Foresters, and was killed in action on Monday, 4 November 1918, aged 22, after three years and eight months of service. Son of John and Dinah Thompson, of 35 Golgotha Road, Bowerham, he is commemorated with them in Scotforth Cemetery.

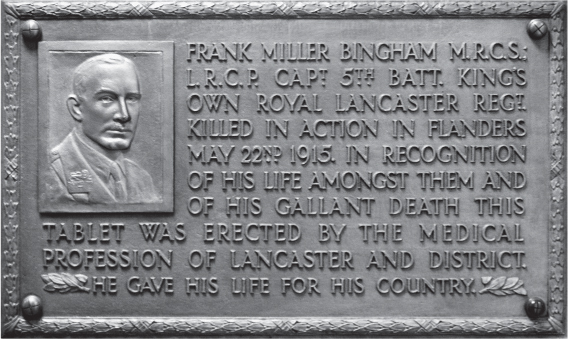

In other cases, memorials were raised to individuals who were killed. Perhaps the first of these in Lancaster was the plaque unveiled in Royal Lancaster Infirmary in December 1915 in memory of Captain Frank Miller Bingham. As well as being a doctor, Frank Bingham had played rugby and cricket, sang in Caton Church Choir and had been in the Territorials before the war in what became the 1st/5th Battalion, King’s Own. He had survived the Second Battle of Ypres but was shot by a sniper on 22 May 1915 while reconnoitring the trenches that the battalion was to take over on its return to the front. He was 40 years old and left a wife and three children. Those entering the Infirmary’s old building still walk past his memorial today.

Lancaster’s First War Memorial? Frank Miller Bingham’s plaque in the Royal Lancaster Infirmary. (KOM)

Lancaster already had one site established to commemorate the fallen of the King’s Own: the Lancaster Priory which houses the Regimental Chapel. It was built in 1903–04 by moving part of the fifteenth century north wall twenty-one feet north and replacing it with four arches and an oak screen. The memorial was dedicated to the memory of the officers and men of all battalions who had died in the war in South Africa. After the First World War, a shrine containing a roll of honour to the fallen men of the regiment was unveiled by Field Marshal The Right Honourable Earl Haig on 27 November 1924.

To provide the national context: Adrian Gregory points out that of the 5,930 memorials unveiled in Britain after the war, 5,151 had been erected by 1920. Only 2.2 per cent of British war memorials were sculptural. Over half – 57 per cent – were sited in places of worship.

On the north wall, just east of the Regimental Chapel, is a brass plaque to the members of the St John Ambulance Brigade who fell in the Great War. It includes five names, one of whom is the nurse Muriel Beatrice Ogilvy, who began her service aged 39 on 26 July 1915. She continued serving after the armistice, but died in November 1920. This is a rare inclusion of a woman on a war memorial in Lancaster, although the Bowerham Primary School Roll of Honour, unveiled by the Lord Lieutenant of Lancashire, the Rightt Honourable Lord Shuttleworth on 8 July 1919, lists service as well as death, and includes six female names, distinguished by the inclusion of first names and by being colour coded.

Field Marshal The Right Honourable Earl Haig on 27 November 1924. (KOM)

As in communities all across Britain, the armistice made topical discussions about appropriate physical memorialisation of the war for the community as a whole. Debates in Lancaster mirrored debates in the country as a whole in that there were two main competing visions as to what form that memorial should take: utilitarian or aesthetic. The utilitarian and less conventional possibility was the consequence of collaboration between local landscape architect Thomas Mawson and local industrialist Herbert Lushington Storey. Mawson’s youngest son James Radcliffe had been killed in 1915. Shortly before his death, he had written to his father stating how moved he had been by the bravery of the injured men and asking his parents to do what they could to help the wounded. The idea for an industrial village to house disabled servicemen had appeared in Mawson’s book An Imperial Obligation, first published in 1917 with a foreword by Field Marshal Sir Douglas Haig. Although the original idea was to create a chain of these across Britain, it was in Lancaster that Mawson’s vision came to fruition.

Unlike Mawson, Herbert Storey’s son came home safely; however the Storey family had a long history of philanthropic projects in Lancaster. Together, Storey and Mawson set up a committee to consider the erection of an industrial village to house disabled servicemen, which would act as a permanent memorial ‘to the officers, non-commissioned officers and men of the King’s Own Royal Lancaster Regiment and all those men and women of Lancaster and district who gave their lives in the service of their King and country during the Great War of 1914–1918.’ The intention was to house and employ local men (with or without dependents) who had returned from the war with physical disabilities: the village itself would be part of their recovery, with its beautiful gardens, a bowling green and a club.

Meanwhile, the Town Council had set up a committee to discuss what form the local memorial should take, envisaging a more conventional monument. On 27 November 1918, the decision was taken at a public meeting held in the Town Hall to take both proposals forward. At the unveiling ceremony of the garden of remembrance, Alderman Nuttall was to comment on the two complementary war memorials: ‘One had the noble ideal of helping the men who suffered and the other perpetuated the memory of the dead.’

There is photographic evidence that, in the interim, a temporary cenotaph reminiscent of that erected in Whitehall, London was erected in Dalton Square in the centre of the town opposite the Town Hall. On 3 December 1924, the Lancaster War Memorial was unveiled in the garden of remembrance attracting more wreaths, than Lancaster Guardian reported, then ever before. Designed by T.H. Mawson & Sons (which suggests the two memorial projects were not wholly antagonistic) it cost £1,900, and was paid for by public subscription from ‘every class of the community … there being many small contributions from poor people’. Thirty-five feet in length, it consists of a stone background holding ten panels bearing the names of 1,010 men. In the centre is a bronze figure of Peace cast at the Bromsgrove School of Art. While the central figure was unveiled by the Mayor of Lancaster, four mothers who had lost twelve sons between them unveiled the panels: Mrs Butterworth, Mrs Gardner, Mrs Williams and Mrs Prickett. Every vantage point was taken by attendees, including 900 relatives and 300 subscribers. The Lancaster Guardian reported the address given by the Reverend J.W. Mountford which had reminded all who listened that the men listed on the memorial had:

‘died to end war, and whether their dream was realised depended upon themselves. … They had done well to build the garden in the heart of the town. It would speak to their civic rulers, to their magistrates, and to all of unperishable things and would purify the soul of the town if was used properly and devoutly, and remembering why the names were on the panels.’

Although very poor quality, this is a rare piece of photographic evidence of Lancaster’s temporary cenotaph: a young soldier or cadet stands on guard with arms reversed whilst dignitaries can be seen in the background on the steps of the Town Hall. (KOM)

The number of dead was a matter of local pride, the press reporting: ‘There were 1,010 names on the panels indicating that Lancaster men responded nobly and lost more heavily than many other towns by the war.’ The validity of this claim has already been discussed in Chapter 7.

Meanwhile, on 5 November 1919, the foundation stone for the Westfield War Memorial Village was laid on the Westfield Estate donated by the Storey family. By the time the village was officially opened by Earl Haig in 1924, twenty-six cottages had been completed, housing seventy-two adults and fifty-one children in total. The rents were held artificially low. There had been multiple fundraising initiatives but, unlike the memorial in the garden of remembrance, the majority of the funding had come from leading local figures and businesses, as well as from the King’s Own.

Westfield War Memorial Village may not have been a unique project for Industrial Settlements, but it is memorable for thriving to this very day. The village has been extended and modernised over time, and now has 113 properties (twenty-two of which are privately owned): priority is given to disabled ex-service personnel; regular and national service personnel; reservists; ex-merchant navy and support personnel; and their dependents. It still testifies to its memorial function in a number of ways: in its title; in the names given the houses; in the brass commemorative plaques inside the entrances to properties funded as a result of public donation (where these survive); and, more recently, in memorial gardens and a tree lit up with a light to represent each of the fallen. The first two cottages funded were named ‘Leslie’ and ‘Morton’ after the names of the two young men in whose memory they had been built. Subsequent dwellings were more likely to be named after specific battles, such as Ypres and Le Cateau, Gallipoli and Somme – regimental battle honours in which the King’s Own had suffered large numbers of casualties.

The Mayor of Lancaster, Councillor Briggs, Lord Derby and Earl Haig at the official village opening in 1924. (KOM)

Hilda Leyel was an actress, political activist and renowned herbalist and author. She founded the Society of Herbalists (later the Herb Society) in England in 1927, and the Culpeper shops in London which sold herbal medicines, food and cosmetics. She was also a charity campaigner who permanently changed the face of charitable giving in Great Britain. Committed to helping disabled veterans and their families, Leyel devised a charity lottery, the winner of which would receive £25,000. Her first Golden Ballot had helped to fund one of Mawson’s first industrial village projects at Preston Hall in Aylesford, Kent. The project permitted Preston Hall to continue as a centre for the treatment of tuberculosis and the establishment of a sanatorium, training colony and village settlement. The second Golden Ballot allowed Leyel to present the Westfield War Memorial Village in Lancaster with £20,000, which permitted twenty-one cottages to be erected, more than half of the original properties on Westfield. It also paid for the construction of roads, drainage and gates. The remaining £6,000 of her donation was invested in War Stock, with continued development in the village funded from the interest. Leyel’s fundraising activities had attracted the attention of the state, however, and Leyel was prosecuted for the running of an illegal lottery. Luckily, as a young Society hostess in Lincoln’s Inn she had made some influential friends, aided no doubt by her refined tastes in food and wine. She opted for trial by jury in 1922, arguing that the ballot had been run purely for charitable purposes, and had transformed the lives of many veterans. The case against her was overturned, and such fundraising initiatives for charitable causes have been deemed legal in the United Kingdom ever since. In the Westfield War Memorial Village, four conjoined houses still bear the name Leyel Terrace.

Hilda Leyel (1880–1957). (Reproduced with kind permission from the Herb Society Archive)

Jennie Delahunt’s monument in her studio. (KOM)

The official war memorial in Westfield Village is held in the communal room, however there is a striking monument at the heart of the village, thanks to Herbert Storey’s intervention. Initially the plot in the village centre was reserved for a sundial, as befitted the feel of an English village, but in May 1924, Herbert Storey proposed a figurative monument representing a soldier giving a wounded comrade a drink. He was to get his way. The sculptress was Jennifer (Jennie) Delahunt, a Lancaster artist, about whom little is known, except that she was born on 16 April 1876, trained at the Manchester School of Art, and worked ‘in joint services’ at the School of Art at the Storey Institute and the Girls’ Grammar School, where she taught from its foundation in August 1907 to July 1934. She may be seen on the right a rare photograph of her studio (opposite): the sitters for the monument posing behind the statue. The memorial was unveiled in 1926 and is still the focal point of the village today.

The monument at the heart of Westfield War Memorial Village today. (CPB)

The memorialisation of the First World War in Lancaster continued into the next century. In 2002 the Lancaster Military Heritage Group began a War Memorial Project, the intention of which was to research the lives of the men and women listed on the local war memorials of Lancaster and Morecambe. That research was presented in The Last Post: The War Memorials of Lancaster and Morecambe and the Reveille website which was recently revised in a project with the Department of History and the School of Computing and Communications at Lancaster University supported by the Heritage Lottery Fund. ‘Streets of Mourning’ maps Lancaster’s war dead on to the addresses listed in the obituaries of the fallen – where the men or their loved ones lived. Members of the local community shared stories of their ancestors and showed how the impact of the First World War has ricocheted down the generations. One moving contributor was Ian Birnie, the great-grandson of William Butterworth, the oldest of the four Butterworth brothers listed on Lancaster’s war memorial. In October 2014, Ian attended the funeral of his great-grandfather, whose remains had been found alongside those of fourteen other British soldiers, close to the village of Beaucamps-Ligny, near Lille. The soldiers were reburied with full military honours at a Commonwealth War Graves Commission cemetery in Bois-Grenier. As Ian noted, ‘When we were told that it was William, it was almost as if we’d lost someone only yesterday. It seems ridiculous as this happened 100 years ago, but to me, and to our family, this is a loss.’

Shrigley and Hunt are nearly forgotten today, but were one of the leading stained glass manufacturers of the late nineteenth century. The business began in the 1750s, but became known as Shrigley and Hunt in 1878, with premises still discernible as such on Castle Hill, Lancaster, opposite the John O’Gaunt gate. The online database of war memorials lists twenty memorial windows accredited to this local firm after the First World War. These are mainly located in the North West.

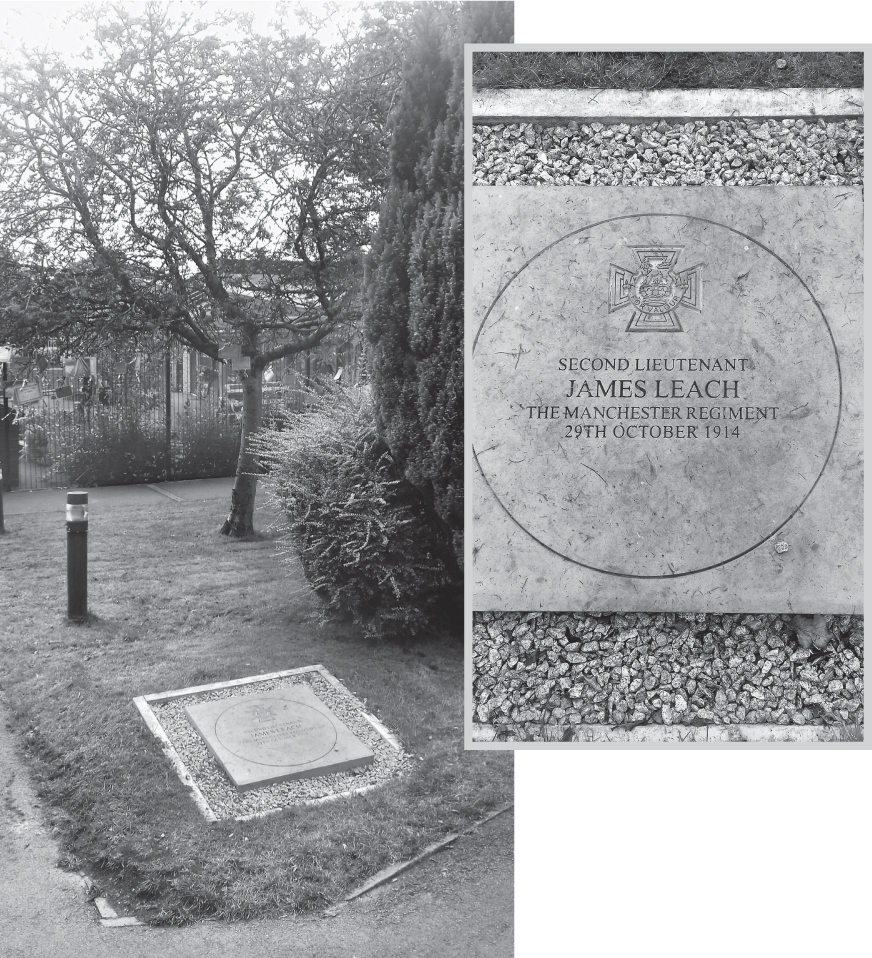

Commemoration of the First World War has not ended in the City. Global Link’s ‘Documenting Dissent’ project has used the skills of local volunteers to recover various underresearched aspects of Lancaster’s experience of the First World War, from conscientious objection to the munition workers and more. More conventional memorialisation also continues with Lancaster’s first Victoria Cross (VC) won by Second Lieutenant James Leach, who was serving with the 2nd Manchester Regiment (see Chapter 2). He was awarded the VC for his ‘conspicuous bravery’ for recapturing a trench from the Germans at Festubert. James Leach was born at Bowerham Barracks, and attended Bowerham School from July 1897 to July 1901. The school grounds were chosen to house the commemorative paving stone: unveiled in 2016. In the same year, three new roads were named after distinguished service men of the King’s Own: 2nd Lieutenant Ronald Macdonald MC, Private Reginald Sydney Dennison MM and Captain Albert Ellwood MC. Thus, 100 years later it continues to be true: the end of the war was only the beginning of its commemoration.

Memorial stone to Second Lieutenant James Edgar Leach, VC, and in the Remembrance Garden at Bowerham Primary and Nursery School. (CPB)