97 Dale Street (the middle door), home of the Cathcart family. (ING)

Chapters 4 and 5 described some of the times, places and events in which Lancastrians fought. The men who died were not just soldiers, sailors and airmen, they were also people who lived, worked and played in the town – and ‘loved and were loved’, to quote John McRae’s poem, ‘In Flanders Fields’. This chapter is based primarily on information about the 1,055 Lancastrians who died in uniform, as listed in Reveille. This does not provide a perfect definition of every Lancastrian who died as a result of the war, but we are lucky to have as it does provide a comprehensive record of ‘the men of Lancaster’ who died in uniform during the war and in its immediate aftermath. This chapter uses this information in an attempt to understand what the losses from the First World War meant to Lancaster.

In 1914 the Cathcart family, John and Mary, and their three children Annie, George and James, lived at 97 Dale Street. They had not long moved to the house; the 1911 Census records them as living on Cable Street (misnaming them as ‘Catheart’). On 6 September 1914, perhaps inspired by the ‘Gallant 200’ (see Chapter 1), James and George Cathcart went to join up. They probably queued up together, perhaps with a friend, as their service numbers were 2091 and 2093 respectively, and they enlisted into the 1st/5th Battalion of the King’s Own Royal Lancaster Regiment. As described in Chapter 4, the battalion sailed to France on 15 February 1915 and marched into Ypres on 9 April. This placed them in the way of the German offensive at the Second Battle of Ypres which began on 22 April. George was killed the following day, along with twelve other Lancastrians, in the counterattack that unsuccessfully tried to push back the German advance. His obituary in the Lancaster Observer notes that James was advancing with him when he was lost. By the time this obituary appeared on 7 May, James was also dead. He had been killed on 4 May, along with six other Lancastrians from the 1st/5th in the shelling that led up to the German assault on Frezenburg. They were 19 and 17 years old respectively when they died.

97 Dale Street (the middle door), home of the Cathcart family. (ING)

The Cathcart brothers’ names on the city’s war memorial. (ING)

The Cathcarts’ tragedy is hardly unique, and indeed by the standards of the time it is barely remarkable. When John Adams was killed alongside George Cathcart on 23 April 1915, his family had already lost their oldest son, Charles, in 1914, while a third son, Henry, died exactly one year after Charles on 26 September 1915 at the Battle of Loos. Their parents lived at 4 Winders Court, Monmouth Street, an area between Moor Lane and Nelson Street where the housing has today been replaced by car parks. The Dinsdales of 34 Havelock Street, Bowerham also lost three sons, William, Frank and George, before the end of 1915. In 1917 the Gardners, who lived nearby at 13 Bowerham Terrace, lost Reginald on 9 April, Alfred on 10 October and, less than a month later, James, on 2 November. James was not even posted overseas but was in a Training Reserve Battalion. He is buried in Lancaster Cemetery. The Williams of Hamner Place, Bowerham and the Glovers of 1 Piccadilly, Scotforth also lost three sons. The Butterworth family of 27 Green Street, Bulk fared even worse. William Butterworth was killed on 18 October 1914, followed by Christopher on 8 May 1915 serving with the 2nd Battalion, King’s Own, at Frezenburg, and Hugh with the 1st/5th three months later. On 12 August 1916 their father, James, was reported in the Lancaster Guardian to have ‘died from debility, caused by having three sons killed and two severely wounded in the war.’ A fourth son, John, subsequently died on 23 June 1917. He may have been one of the severely wounded brothers as he is buried in Lancaster Cemetery.

Fred Carr, 24 Alfred Street, was killed on 22 April 1915. He had six children. Thomas Slater, 11 Main Street, Skerton was killed the following day. He had five children.

In total, 134 of the dead in Reveille are listed as brothers, 13 per cent of the total Lancastrians killed. Even this is not all of them. The two Corless brothers are not marked as such on the memorial, which lists five men named Corless. Bryant Browning, of 1 Marton Street, was killed on the first day of the Somme with the 1st Battalion, King’s Own. His brother, Arthur was killed the following day, also on the Somme, but is not recorded as a Lancastrian as their family home was at 22 Beach Street, Bare and he thus appears on Morecambe War Memorial.

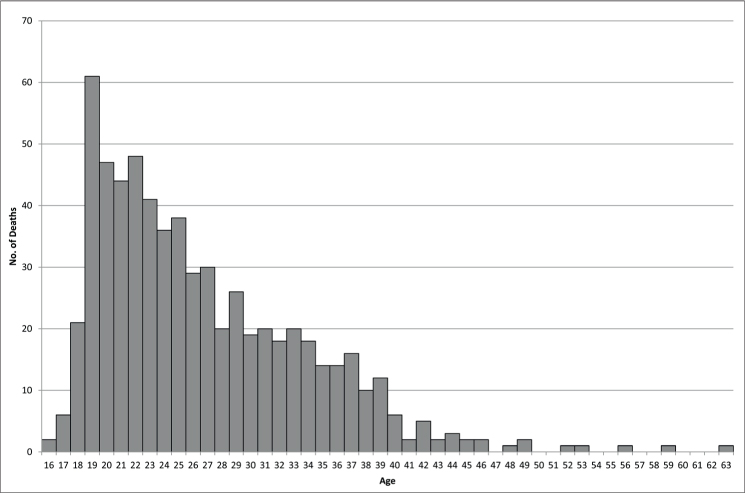

These are only eight of the families who lost sons during the war. It is difficult to understand what the loss of around 1,055 mainly young men in a very few years would have meant for a town the size of Lancaster. The 1911 Census records Lancaster Municipal Borough as having a population of 41,410 of whom 20,204 were male. This suggests that 2.6 per cent of the town’s total population, or 5.2 per cent of the male population, were killed (these numbers must be taken with a little caution as they assume that all of the Lancastrians included in Reveille were also enumerated in the 1911 Census.) Deaths in the war, however, had a very distinct age profile as shown in the graph below. The average age of death among Lancastrians was 26.6 but the most common, by some way, was only 19. Eighty-four per cent of those who died were between 18 and 34. The figures on age of death are based on the 638 records which list age at death. These constitute 60.4 per cent of the total and can be considered representative. A little estimation using census data suggests that 15 per cent of Lancastrian males born between 1886 and 1899 were killed, peaking at 20 per cent of those born in 1895. Records from the 1st/5th, suggest for every man killed, three were wounded which suggests that only around 20 per cent of men born in 1895 survived the war unscathed and over half of the cohort born between 1886 and 1899 were killed or injured.

Numbers of Lancastrians killed, by age. These figures are based on the 638 casualties we have ages for – 60.4 per cent of the total deaths. (Source: Reveille)

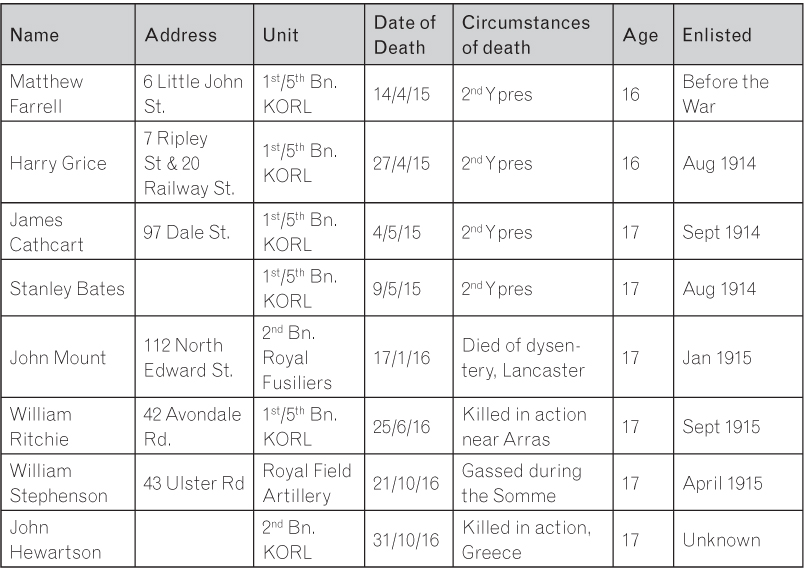

Table 7.1 16 and 17 year olds killed.

Abbreviations: KORL: King’s Own Royal Lancaster Regiment; Battalion. (Source: Reveille)

The above table details the eight Lancastrians killed under the age of eighteen. Although there are frequent stories of boys who lied about their age to join up, this does not seem to have happened in Lancaster, at least not with fatal results. Instead, most of the very young who were killed were either associated with the Territorials before the war, or joined up immediately on its outbreak. As a result, many were in the 1st/5th Battalion and so four of the eight were killed at the Second Battle of Ypres. The remainder died in 1916. It appears, therefore, that as the pressure on manpower increased, leading to the introduction of conscription in 1916, and perhaps as the full horror of modern warfare became apparent, the military actually got better at keeping the very young out of harm’s way. It is also interesting to note that casualties among the very young came from across the social spectrum. Matthew Farrell lived with his mother on Little John Street, now an alley off Church Street near the Stonewell pub which at the time would have had very low-quality housing. His father had left many years before suggesting the family was very poor. Stanley Bates was, by contrast, probably from a wealthy family. He had been a cadet at Lancaster Royal Grammar School and was gazetted at the outbreak of war, being promoted to become the youngest full lieutenant in the British Army. His father, the second in command of the 1st/5th, had been invalided home a few days before Stanley was killed.

The oldest deaths were among men who, although in uniform and thus recorded as war deaths, served at home. The oldest was Henry Tripp, aged 63. We know little about him other than he lived at 55 Norfolk Street, Skerton, and was a private in the 3rd (Special Reserve) Battalion, King’s Own, a training unit that did not serve overseas. He died on 2 July 1916 and is buried in Skerton Cemetery. Major C.J. Holmes was the Surgeon Major at Bowerham Barracks and lived at 50 Regent Street. He died of illness aged 59 in April 1916. Thomas Tite had served, and been decorated, during the Boer War but had since retired. He lived in Trafalgar Road, Bowerham, and rejoined the military at the outbreak of war as an instructor. A training ground accident resulted in his death in January 1916, aged 56. Holmes and Tite are both buried in Lancaster Cemetery.

Private Matthew Farrell (right) at a pre-war 5th Battalion Territorial Force annual camp. He was killed in action on 13 April 1915 aged 16. (KOM)

Seventy per cent of Lancastrians killed in the War were under 30 years old. From a national perspective, the highest increases in mortality rates (as compared with those that could be expected within a population not at war) were for men aged 19–24.

The evidence for who was the oldest soldier to be killed in action is slightly contradictory. Ernest Harlowe of 8 Havelock Street, Bowerham, was killed in action on 27 May 1915 near Ypres. He is recorded by the Commonwealth War Graves Commission as being 46 but his obituary in the Lancaster Observer records him as only being 42. William Warwick of 14 Primrose Street died of wounds on 14 May 1916 aged 45. He was a member of the West Yorkshire Regiment’s 1st Garrison Battalion and is buried at Etaples Military Cemetery. Etaples was a major military camp with several hospitals and it is unclear whether his injuries were sustained at the front or on base duties. William Johnson of 14 Sun Street was 44 when he died in February 1915. Although he is reported killed in action, he is buried at Longuenesse (St Omer) Souvenir Cemetery well behind the front lines, which is unusual for someone killed in action. Two 43-year-olds definitely did die in action: John Pye, of 37 Marton Street, killed with the 1st/5th at Second Ypres and had previously fought in the Boer War; and William Davies, who lived at 6 Dickinsons Buildings, Parliament Street, and was killed at Gallipoli at the end of May 1915. As with the youngest, it is striking that the older men who died in action did so at the start of the war, mainly in 1915, again suggesting that the military became more careful about whom it put in the front line as the war progressed.

Reveille provides addresses for 80 per cent of the men listed. These are not always the addresses that the men lived in when they signed up: sometimes they are an address they had lived at before the war, sometimes they are their parents’ address, and sometimes a widow’s address after the war. In a few cases two or even three addresses are given. Nevertheless, these do provide an indication of the parts of the town that were most affected by deaths during the war. The image below (page 133) maps the numbers of deaths by street. It includes a 1919 map of Lancaster which shows that the street network in the centre of town has changed little over time except for the outward expansion of the town, and the demolition of houses and factories in a line from St. Leonard’s Gate to Thurnham Street. The other thing to note is that this map both underestimates the extent of the losses experienced (we do not have addresses for 20 per cent of the men killed) and yet also overestimates it (we have more than one address for 13 per cent of the men listed). It may also be a little inconsistent in terms of which next of kin are listed with addresses and which are not.

Some clear patterns emerge from the map. Working from south to north, the worst affected areas were Primrose, to the east of the city centre, and close to the Barracks, which lost ninety-three men. Next, the area around St Leonard’s Gate and Edward Street lost sixty-three. These two streets, where the housing has since been largely demolished and replaced with car parks, were the two worst affected streets in town with twenty-two and twenty losses respectively. North of here, the small area of terraced housing between Bulk Road and the canal around Green Street, lost fifty-four. Across the river, the southern part of Skerton around Lune Street lost forty-one; further north in Skerton, around Broadway and Main Street, seventy-five men were lost. Another area of note is the city centre: within what is now the one-way system where few people now live, eighty-seven men were lost.

One possible explanation for this pattern is that the war took a heavier toll on people in the poorer parts of town – many of these areas have terraced housing where the front doors open straight onto the street, or where housing has been demolished which may point to it being lower quality. While this theory is plausible, it needs to be treated with caution. Although we know how many people from a street were lost, we do not how many people lived on the street, so long streets of dense terraced housing with large numbers of people per house might have high numbers of losses simply because of the large number of people living on them.

The website The Long Long Trail (www.1914-1918.net/faq.htm) provides extensive data on the First World War, although any statistics, particularly on such a complex event, must be treated with caution. However, to put the local figures discussed here into a national perspective:

Britain entered the war with a much smaller standing army than those of France and Germany – in August 1914, it numbered just 733,514. In total, however, 8.7 million men served at some point of the war, just under 5 million drawn from the United Kingdom (the majority of whom from England) and the remainder from the Empire, including troops from India, Canada, Australia and Tasmania, New Zealand, South Africa, Newfoundland, West Indies and other Dominions. Around 62 per cent of these men served in France and Flanders on the Western Front. Other theatres of war included Mesopotamia, Egypt and Palestine, Salonika, Italy, and Gallipoli. The total of these men who died in action or of wounds, disease or injury, and including those missing presumed dead, number 956,703, of whom members of the Royal Navy and the Royal Flying Corps/Royal Air Force constitute 39,527. Around 27 per cent of the total casualties were from the Empire. About half of these men have named graves; the remainder are either buried but unidentifiable or lost (for example, at sea). The nature of warfare between 1914 and 1918 resulted in a high proportion of wounded men to men in action: the total number of British Army wounded in action was well over 2 million: these men could return to duty (62 per cent); return to limited roles (18 per cent); or be discharged (8 per cent). Around 7 per cent died of wounds received, but that figure does not include those who died of war-related injuries in the years following the war’s immediate aftermath.

Lancaster’s losses by street. (Source: Casualty figures from Reveille. The historic base map is a six inches to the mile map from 1919. For the modern base map, sources: Esri, HERE, DeLorme, Intermap, increment P Corp., GEBCO, USGS, FAO, NPS, NRCAN, GeoBase, IGN, Kadaster NL, Ordnance Survey, Esri Japan, METI, Esri China (Hong Kong), swisstopo, MapmyIndia, © OpenStreetMap contributors, and the GIS User Community.)

One street of particular note is Green Street in Bulk. This had fifteen losses, the fifth highest, but, unlike other badly affected streets, is a short residential cul-de-sac. The odd-numbered side of this street, as it appears today, is shown in the following picture. The first door visible on the photograph is number 3, where Edward Clancy lived with his father. When he was killed on 26 April 1918 near Ypres, he became the last resident of the street to be killed. Staying on this side of the street, five doors further up, number 13 is listed as the address of both Hugh Rourke and James Muckalt. Hugh was killed on 13 March 1915, one of the first members of the 1st/5th Battalion to be killed in France. James was not killed until 12 April 1918 by which point he had served overseas for three-and-a-half years. A few doors further up, at number 21, Harold Dennison lived with his mother, a ‘dependant widow,’ until he was killed on 27 September 1917. Three doors further up, at number 27, William Butterworth was the first resident of the street killed on 18 October 1914. As previously described, the family lost three other brothers and their father during the war. Only three of the brothers are included in our figures, the other, Christopher, lived in Skerton. The houses at the end of the street have been demolished. The last one standing is number 33, however, on what is now a small patch of grass and a turning head, three neighbouring houses lost at least four people: Robert Cunliffe, from number 43, was killed with the 1st/5th at Frezenburg on 9 May 1915. Next door at number 45, Robert Shorrocks was killed when HMS Cleopatra hit a mine off of the Belgian coast on 4 August 1916. The ship was not badly damaged. His death came only six weeks after his brother Richard was killed fighting with Canadian forces. However, as he had emigrated to Canada before the war, he is not included as someone who lived on the street. Next door again, number 47, the last house on this side of the street, lost two men: Arthur Greenbank, killed on 6 November 1915, and George Yates, killed on 15 August 1916 with the 1st/5th on Lancaster’s worst day of the Somme campaign. Turning round and coming back down the other side of the street, the highest house number was (and is) 32. John Condon lived here until he was killed at Loos on 26 September 1915 with the Seaforth Highlanders. Next door, the Young brothers, William and Robert, lived until they were killed on 27 November 1915 and 31 July 1917 respectively. Ten doors further down, at number 10, Peter Renshall seems to have gone to France with the 1st/5th in February 1915 and have survived both Second Ypres and the Somme before being killed near Ypres on 12 March 1917.

The Lancaster Observer reported on 7 May 1915 that twelve men from 6 Lucy Street had gone to war: ‘two Bagots, five of Mrs Bettany’s sons, two lads she had brought up, and three lodgers.’ John Bagot was killed in June 1915, however, it appears that his brother and all of the Bettanys returned. Without their names, we cannot be sure of the fate of the ‘two lads … and three lodgers’, however, a John Stevenson of 6 Lucy Street was killed on 7 January 1918.

Thus a three-minute walk goes past thirty-nine houses from which fifteen men were recorded as lost, along with several more that are slightly less directly connected with the properties. Although severe, the losses on this street are a microcosm of the way the war affected Lancaster. Some occurred in major events for the city such as Second Ypres, Loos and the Somme. Others are in lesser known events such as when HMS Cleopatra sustained minor damage hitting a mine, or dates like 6 November 1915 when, in the grand scheme of things, very little happened – unless you knew Arthur Greenbank.

The odd-numbered side of Green Street today from numbers 3 to 33. The new houses at the end are on the far side of the canal. Photo taken from the junction with Bulk Road.

As well as living in the town, the men who died also went to school and work. We have some information on this, although it is not as comprehensive as the data on addresses. We only know which school a casualty went to if it was named in his obituary. From this, we know the school that 442 casualties went to: 42 per cent of the total in the database. The casualties per school are shown in table 7.2. As these only refer to less than half of the casualties, school memorials or other records are likely to have more or different names and matching these names to the details on Reveille would be an interesting project that has yet to be done.

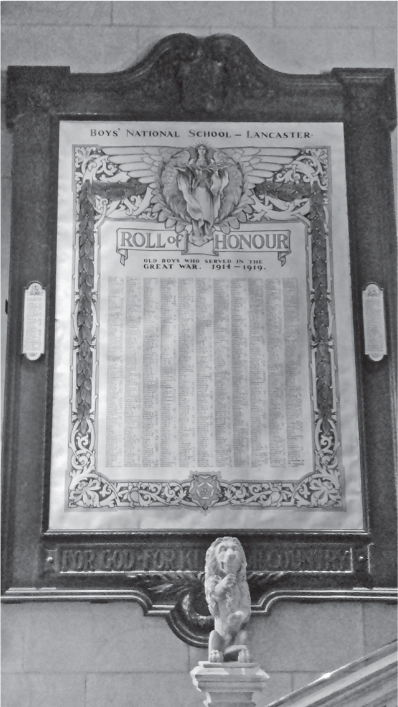

The first striking point about these statistics is the fact that schooling was spread around far more schools than today, many of which were small Anglican schools attached to churches. The worst affected school was the National School, or ‘Nashy’ which was at the east end of St Leonard’s Gate where the retirement homes on St Leonard Court now stand. Reveille records eighty-one old boys who died. St Thomas’, attached to St Thomas’ Church on Marton Street in the city centre, lost fifty-five. Bowerham School, which remains on its wartime site, lost forty-nine.

We can also consider casualties in terms of their former places of work. The obituaries in Reveille provide employers for 456 men, a little under half of the total casualties. As with addresses, some give more than one employer, perhaps because they worked for more than one, or had worked for them at different times. These give a total of 492 employers. The largest losses were at the Lune Mills site, from where 137 men were killed. This site employed around 2,000 men and boys in the early 1900s suggesting that around 7 per cent of the workforce was killed. Given that we have occupations for less than half of the casualties, the real percentage could have been at least twice this. Storey’s main site, White Cross Mills, which employed around 1,000 workers, lost forty-eight men. If we add casualties from the other sites owned by the two major employers, 180 casualties are known to have worked for Williamson’s and sixty-seven for Storey’s. In total, 54 per cent of the casualties with a known employer worked for one of these two companies.

School |

Known deaths |

% of known |

National School |

81 |

18.3 |

St. Thomas |

55 |

12.4 |

Bowerham School |

49 |

11.1 |

St. Peters |

47 |

10.6 |

Christ Church |

37 |

8.4 |

Skerton Council School |

37 |

8.4 |

Lancaster Royal Grammar |

32 |

7.2 |

Scotforth |

16 |

3.6 |

Sulyard Street |

14 |

3.2 |

St. Lukes |

14 |

3.2 |

Friends School |

12 |

2.7 |

St. Marys |

10 |

2.3 |

Quay School |

8 |

1.8 |

Greaves School |

7 |

1.6 |

Ripley |

6 |

1.4 |

Table 7.2 Numbers of known casualties per school.

The percentage column is the percentage of the 442 casualties for whom we have a known school. (Source: Reveille).

The other major manufacturing employer was Waring and Gillow, whose major site still stands on St Leonard’s Gate, which lost fourteen employees. The casualties reveal, however, that employment in Lancaster was about more than just manufacturing. As noted in Chapter 6, farmers were reluctant to let their sons go to war due to the labour shortages this would cause – despite this, twenty-one casualties are recorded as working in agriculture. Transport was another important employer: sixteen Lancastrian casualties worked for the London & North-Western Railway Company, which operated what is now the West Coast Mainline; a further five worked for Lancaster Castle station; another five worked for the Midland Railway which operated the line that ran from Morecambe, over what is now Greyhound Bridge to Lancaster Green Ayre station and then up what is now the Lune Valley cycle path, to eventually get to Leeds; and three more worked for the Lancaster and District Tramway Company which was based on Thurnham Street in the building which is now Kwik Fit. Many of the remaining casualties were divided among a wide variety of employers including Lancaster Corporation (seven deaths), the County Asylum (five), the Post Office (five), the police (four), Lancaster & District Cooperative Society (four), and the Lancaster Guardian (three). A lot also worked for small employers, perhaps most poignantly eleven men are recorded as working for ‘his father’.

The Roll of Honour of the National School. (With thanks to Ripley St Thomas Church of England Academy)

As with schools, these figures are underestimates based on obituaries. They could be enhanced by comparing these records with the many small memorials that still dot the town, for example, the memorial to Post Office workers records eight names rather than five, while the Cooperative Society’s records five rather than four. Memorials to particular individuals still appear in places of employment around the town.

The statement that almost every family was affected by death in the war has become a cliché, albeit one that recent historians have attempted to challenge. What this chapter shows is that the impact of the war was undoubtedly devastating. The bald numbers, 1,055 men killed, 5.2 per cent of the male population, rising to 15 per cent in some age groups, do not do this justice. While we have some of the stories of the 134 brothers who were killed, we know little about the hundreds of parents who lost children, the wives left as widows, the children left without fathers, and all of the other family members who lost relatives. It does seem likely that anyone who was related to, lived near, worked, or had been to school with young(ish) men is likely to have known at least one, if not quite a number of people who were killed. If you walk down almost any street in town you will pass a house from which someone was lost.

Even this underestimates the impact. As previously stated, for every man killed, around three were wounded, often with devastating long-term consequences. Beyond this, the First World War foregrounded mental health issues associated with trauma. It is when shellshock, now termed post-traumatic stress disorder, began to be recognised as a medical condition. The impact of this, still poorly understood condition, on the men who came home and their families and friends can only be speculated on.

It is perhaps worth standing back from Lancaster briefly. J. Winter estimates that 1.6 per cent of the population of Britain and Ireland were killed. This makes Lancaster’s experience of losing 2.6 per cent of its population significantly worse than average for Britain. In many countries – including Austria-Hungary, Bulgaria, France, Germany, Greece, Italy, the Ottoman Empire, Romania and Serbia – at least 3 per cent of the population, and in some cases many more, were killed. Lancaster’s experience stands out in Great Britain, but was less severe than that of much of Europe.