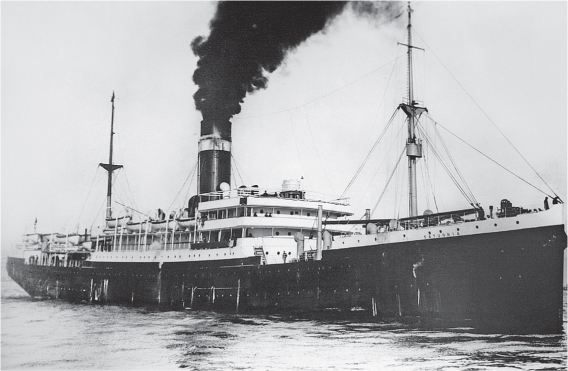

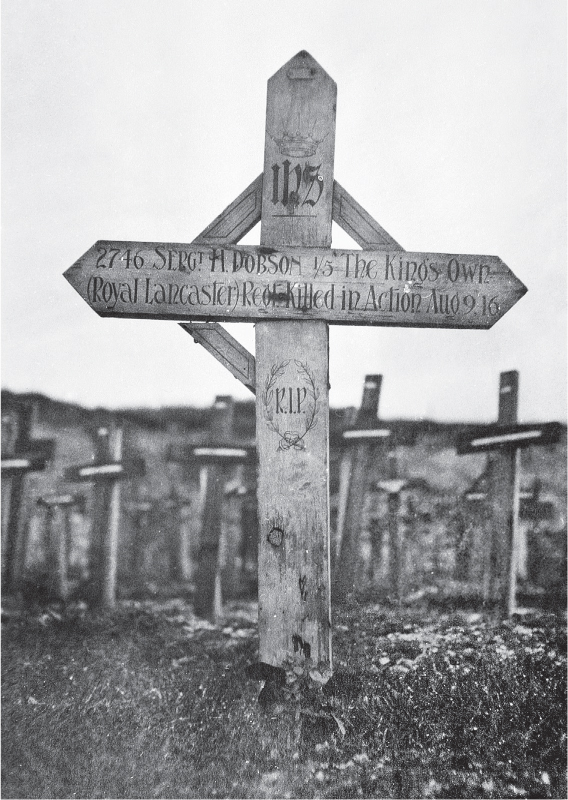

The SS Saturnia on which the 1st Battalion, King’s Own, crossed the English Channel on 22 August 1914. (KOM)

To give a flavour of the experience of Lancastrian soldiers, this chapter describes three of the main events in which members of the King’s Own were involved. After all, 40 per cent of Lancastrians who died in the war died with the King’s Own. The first of these events is the 1914 Retreat from Mons. The British Expeditionary Force, newly arrived in France, found itself in the way of the major German advance that swept through Belgium and then south towards Paris. This led to desperate fighting in which the King’s Own’s 1st Battalion paid a heavy price. This successful defence led to the failure of the German Schlieffen Plan but, in turn, paved the way for the trench warfare that would last until 1918. The second, in 1915, saw the 1st/5th and 2nd Battalions of the King’s Own heavily involved in the Second Battle of Ypres in which the Germans used poison gas for the first time on the Western Front. Ultimately, the German attack was a failure but, as described in Chapter 5, this fighting led to Lancaster’s worst period of the war. The Second Battle of Ypres has largely been forgotten by the history books. The third battle discussed here is that of the Somme in 1916, which, by contrast, has become the archetypal British First World War battle. Five battalions of the regiment were involved.

The German plan of attack was named after their chief-of-staff Alfred von Schlieffen. It reflected the belief that Germany would have to contend with a war on two fronts: with France in the west and Russia in the east. The intention was to beat France rapidly, then turn to meet the Russian army, which would take longer to mobilise. In 1914, the plan swiftly went awry when Russia began to mobilise before France, and Britain declared war on Germany for the invasion of Belgium.

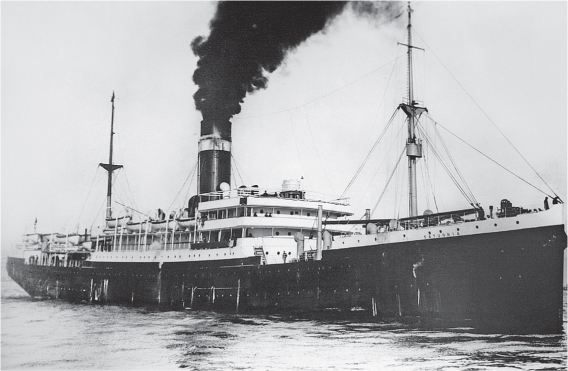

The 1st Battalion, King’s Own, travelled across the English Channel on board the SS Saturnia on 22 August 1914. Their Commanding Officer, Lieutenant Colonel Alfred McNair Dykes was annoyed to be placed in command of all the troops on board the ship, as he explained in what would turn out to be the last letter he would write to his wife. Whilst he was writing the letter, some of his soldiers on board found an empty beer bottle of the Crown Brewery at Fulham and wrote a quick note, placed it in the bottle and threw it over board. The message was not read until it was caught in the nets of the Grimsby trawler Egret on 6 March 1922:

From the boys of the King’s Own (R.L.R.), Dover, SS Saturnia. 22nd August 1914

To The Editor, The Daily Mirror

Well on the way to the front. Just seen the last of England. Mean to fight like Britons. Hope to see Leicester Square again shortly.

The battalion arrived in France on 23 August 1914 and, moving by train and route march, arrived at the village of Haucourt on the morning of 26 August. Their orders were to hold the German advance, as the British Expeditionary Force was pushed back from the Belgian city of Mons. The men were exhausted and hungry, so as breakfast was prepared, the battalion formed up on a forward-facing slope. The sergeant majors ensured that the lines were smart, neat and tidy. The decision was also taken that the men should have their ‘arms piled’, which means that the rifles were placed with their butts on the ground with their muzzles leaning on each other.

The SS Saturnia on which the 1st Battalion, King’s Own, crossed the English Channel on 22 August 1914. (KOM)

The shell-encrusted beer bottle thrown into the sea by soldiers on board the SS Saturnia and picked up by the Grimsby trawler Egret on 6 March 1922, containing a hand-written note to the Editor of the Daily Mirror. (KOM)

Second Lieutenant Gaston Roland Rigden Beaumont, who had been commissioned into the 3rd (Special Reserve) Battalion of the King’s Own in 1913 and attached to the 1st Battalion on mobilisation, provides an account of the events that followed. In the fighting, the battalion was nearly destroyed as a fighting unit, Lieutenant Colonel Dykes and many others were killed, and many more, including Lieutenant Charles Irving (see Chapter 1), wounded or taken prisoner:

We arrived at dawn by the Ligny Road to a spot where subsequently we suffered so heavily. The Battalion was ordered to form close Column facing the enemy’s direction of defences. Companies were dressed by the right, piled arms, and placed equipment at their feet. There was a big stir because some of the arms were out of alignment and the equipment did not in all cases show a true line. A full 7 to 10 minutes was spent in adjusting these errors. The Brigade Commander rode up to the Commanding Officer (Lieutenant Colonel Dykes) and shortly afterwards we were told to remain where we were as breakfast would shortly be up. Everyone was very tired and hungry having had nothing to eat since dinner the day before. A remark was passed as regards our safety. My Company Commander replied that French Cavalry were out in front and the enemy could not possibly worry us for at least three hours.

The picture of this period was as follows:

Three Companies of the Battalion in close Column, the fourth company just about to move up to the left with a view to continuing a line with the 20th who had just commenced to dig in. Just about this time some Cavalry (about a troop) rode within 500 yards of us, looked at us and trotted off again. I saw their uniform quite distinctly and mentioned that they were not Frenchmen. I was told not to talk nonsense and reminded that I was very young. It was early in the morning and nobody felt talkative, least of all my Company Commander. The Cavalry appeared again in the distance and brought up wheeled vehicles; this was all done very peaceably and exposed to full view. We could now hear the road transport on the cobbled road and a shout went up ‘Here’s the Cooker’. New life came to the men and mess tins were hurriedly sought. Then came the fire. The field we were in was a cornfield. The corn had been cut. Bullets were mostly about 4 feet high just hitting the top of the corn stalks. Temporary panic ensued. Some tried to reach the valley behind, others chewed the cud; of those who got up most were hit. The machine gun fire only lasted about two minutes and caused about 400 casualties. The 4th Company moving off to the left was caught in columns of fours. Shell fire now started and did considerable damage to the transport, the cooker being the first vehicle to go. A little Sealyham terrier that we had collected at Horsham St. Faith’s before embarking, and that the troops had jacketed with the Union Jack was killed whilst standing next to the Driver of a General Service Wagon. I mention this as I saw the same Driver the day after still carrying the dog, he was very upset when he was ordered to bury it.

The Commanding Officer was killed by the first burst and the Second in Command rallied the Battalion; several of us taking up position to the right of the point where we had suffered so heavily.

An attack was organised at once, we re-took our arms and got in most of the wounded. The others were left and taken prisoner later at Haucourt Church that night.

Corporal Ellis Williams (left), 1st Battalion, King’s Own, at Waterloo Station, London following his evacuation from France. (KOM)

Never again on active service was any battalion of the King’s Own given the order to ‘pile arms’.

The fighting from this period at the Battle of Le Cateau inspired one of Lancaster’s sons, the poet Laurence Binyon, born on High Street, Lancaster, in 1869, to write his poem For the Fallen. This was published in The Times newspaper on 21 September 1914, long before the full horrors of the conflict emerged. The verse ending ‘We will remember them’ forms a central part in Remembrance Day activities today.

Corporal Ellis Williams, a long-time member of the battalion, was wounded at Le Cateau and evacuated home. Writing from the London Hospital on 1 December, he described the action in a letter home to his mother:

I have landed here after a short tour round France. I am wounded in the right forearm (shell) but nothing serious. They think I have got a touch of dysentery but I doubt it myself. I can’t write about our engagement for it would fill a book. Tell Dad (former Colour Sergeant Ellis Williams) it was a great blunder. Our brigade formed in mass on a hill and entrenched to oppose the German right flank. We had no sooner formed mass when the Germans opened fire with about 15 Maxims and 4 Brigades of artillery at a distance of about 350 to 500 yards. All we could do was to lie down flat on our faces, but the fire got too hot and we had to return to a small village. They then directed their fire on the village and completely destroyed it. Our Colonel and many officers were killed and, they say, nearly half the Battalion. I did not see Jack [his brother] so God only knows if he is safe. We must pray that he is so ... I have no arms or equipment. I took them to the Field Hospital but they shelled it so we had to leave. Some poor chaps were buried in it. Poor Jack Sharp was one I believe. I should like some cigarettes for I’m broke absolutely. I have asked Fred to get me a razor and some more things and I will pay him later.

No more at present. Mother.

Best Love to all.

Your affectionate son.

Ellis.

Five Williams brothers, from Hanmer Place, Bowerham, served in the War. While Ellis and Jack survived, Herbert died of wounds in France, 23 March 1915; Reginald was killed on the Somme, 12 October 1916; and Lloyd drowned when his boat sank on the River Nile in May 1917.

Corporal Williams’s brother, Sergeant John (Jack) Williams was, in fact, taken prisoner and was able to send a postcard home to his parents who lived at Bowerham. The card, dated 16 October 1914, stated:

I am in a large hospital in Berlin (Templehof Garrison), and arrived here on Sunday from Doberitz. I was wounded on 26th August in the right thigh at Harcourt, in France. Was, of course, taken prisoner, as I could not move, and sent back to Ligny, in Belgium, under a German guard. I remained there three weeks and then moved to Cambrai, and so by train through Germany to Dobertiz, some 12 miles from Berlin. Here my wound took a turn for the worse, and I was operated upon for abscess, and, unfortunately, they struck an artery. I remained in hospital at Dobertiz, but, with its only being an improvised hospital they could do me no good. Anyhow, I was taken to Berlin last Sunday (11th October) and was again operated upon on the following Tuesday, and am now doing very well. When you write, write on an open postcard. I don’t know how long I shall be here. I am dying to hear from someone.

Despite the carnage suffered by the 1st Battalion, King’s Own, at Le Cateau, 26 August 1914, only two Lancastrians were killed: John Arkwright (47 Clarence Street) and Thomas Henderson (84 Clarendon Road). Edward Armer (15 Ridge Street) of the King’s Own Yorkshire Light Infantry was also killed that day. They were the first three Lancastrians killed in action during the War.

Jack Williams remained a prisoner of war until after the Armistice in November 1918 when he was repatriated.

After Le Cateau, the 1st Battalion retreated into France with the rest of the Expeditionary Force. The time was very trying with the constant threat of German attack. There was no rest and little to eat except the emergency rations. When the battalion crossed the River Somme all officers’ kits were burnt to allow for the transport to be used by the wounded and the foot-sore men, showing just how much pressure the men were under. By 29 August 1914 the strength of the battalion had fallen to fourteen officers and 400 other ranks, under half the numbers which had arrived in France less than a week earlier.

Lancaster’s Territorial Force battalion, now designed the 1st/5th Battalion, King’s Own Royal Lancaster Regiment, departed England on St Valentine’s Day 1915, on board the Manchester Importer, another merchant vessel hired by the War Office for use in the conflict. Private Robert Higginson, a ‘Lancaster Pal’ and formerly a clerk with the London and North Western Railway at Lancaster Castle station, described the journey across the channel as having conditions like a cattle boat, with rotten sleeping accommodation and noting that he was rather seasick. The boat arrived at Le Havre at 7.00 a.m., however, it was not until after noon that it finally berthed and the soldiers were able to disembark in France.

They began their journey to the Front, starting with a four-mile route march to the station and a train with forty to forty-five men to each cattle truck. It was a horrible journey which ended up with a 7-mile march to tented accommodation. By 20 February the men were digging practice trenches and by Sunday 14 March they were getting ready to move into the front line trenches. ‘Lancaster Pal’ Private Frank Cantrill described the scene on 30 March:

When you look over the parapet you can see ruined houses all the way around and great big big holes where the shells have dropped. One house is only fifty yards away, and two of us went off to look round for some coal for our fire and it was a sight to see, dead horses, cows, and pigs all over the place. There were about a dozen men buried in the garden at the back of the house.

On 9 April, the battalion was moved to the Ypres salient and took up positions in Polygon Wood, east of the town. They received their first shock of a German attack on 13 and 14 April. Major Bates, the battalion’s second in command, wrote home to a friend:

13th April – the trench mortars caught a number of our chaps. The next night a working party were in the woods and high explosive shells were pushed into them. In twenty seconds four were killed and twenty were wounded. Blackhurst and Fred Eltoft hit by a trench mortar and didn’t live long.

The Colonel takes the service and I accompany him, apart from the pioneers who make the graves, and the stretcher bearers, we are alone. It was a sad affair, noisy through the booming of heavy guns and rifle cracking all around.

We soon forget it all, but however horrible is the war we realise we are fighting for posterity, and we pray it will soon be over.

Lance Corporal John Hirst Harper, 1st/5th Battalion, King’s Own, killed in action 13 April 1915. One of those on the sketch map on page 84 and one of a number of brothers who feature on Lancaster’s War Memorial. (KOM)

While they were there they were heavily shelled. One of the ‘Pals’ wrote home:

We just got into the centre of the wood when the Germans started shelling it. Well, we had to take any cover we could get, and I tumbled over a dead horse, it’s ribs went in but I laid where I was, till another shell brought the top of a tree down, and it caught me fair on the ‘thinking box’ and I made my way out of the wood after the nerve testing experience with a champion head.

War is simply hell let loose. There has been over 50 killed and wounded in less than 24 hours. You feel it when your mates go down.

Another Lancaster soldier wrote home:

We have moved to a place called by the regulars the ‘Gates of Hell’. No picture nor pen can describe it ... as Lancaster will soon know our casualties in the two days are eight killed and about forty wounded.

When the men were relieved from Polygon Wood and pulled back to billets in Ypres Lunatic Asylum on 17 April, Lord Richard Cavendish wrote in his diary:

Our total casualties for the four days were 14 killed or died of wounds and 44 wounded. Three men’s nerves went and George (Medical Officer) fears that two may be permanently mad. The men are very cheerful …

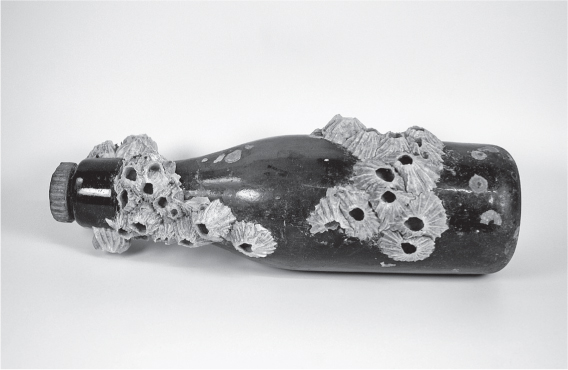

Casualties were buried in graves marked with hastily created wooden crosses. Until soldiers were issued with two fibre identity discs from 1916, no identity disk remained with the body once interred, as the metal identity disk in use at the time of this battle was removed from the body once the grave marker named the soldier. However, the terrain and many of these graves were subsequently destroyed by the fighting that continued in this area for much of the rest of the war, even if attempts had been made to record burials. This explains why so many of the men killed have no known grave and so many of First World War headstones simply read ‘A soldier of the Great War known unto God.’

Private Carr of the 1st/5th Battalion, King’s Own, watches as shells explode overhead near the Menin Road, Ypres. (KOM)

If the news of those killed and wounded in the shelling at Polygon Wood was a shock to Lancaster, worse was to come within only a few days. On 21 April, the 1st/5th Battalion was by now dug in north of St Jean, near Ypres, where they caught some of the German shelling. Steams of panic-stricken civilians and green-faced gasping French soldiers and Zouvaves (French colonial troops) came straggling back, obviously panic-stricken, not wounded, but suffering terribly and quite incoherent. These were some of the very few survivors of the first German gas attack, when the line held by the French Territorials and Zouvaves had been overwhelmed and routed. On 23 April, St George’s Day which was also the Regiment’s Day, the 1st/5th acted as a supporting battalion to an attack, but they had only the vaguest outlines as to the objectives and the direction. Colonel Lord Richard Cavendish described what happened:

We got under rifle fire, there was not a particle of cover, the leading regiment lost direction, and we got enfilade fire on us. I was pleased with the way our fellows went ahead, continually meeting a stream of wounded going to the rear and the ground littered with dead. There was one field with heaps of manure in rows. A lot of fellows thought that they could take shelter behind them. They are, of course not bullet-proof, and there was hardly a heap without a dead or wounded man beside it. The opium tablets came in very handy. I gave a lot to the poor fellows.

Sketch map showing the location of graves of soldiers of the 1st/5th Battalion, King’s Own, killed at Polygon Wood in April 1915. (KOM)

The Colonel then described the scene after the battle:

It was a terrible experience going over the battlefield last night – dead men, rifles, packs, equipment, lying at all directions. We have not been able to bury many of them as our spades have been left far away from our trenches. I am glad to say that a good many of our missing have turned up. The men are wonderfully good at the way they go on.

The following day, Private James Radcliffe Mawson died of wounds. He was the son of Thomas Mawson, a landscape architect. As Chapter 8 describes, his son’s death motivated Thomas Mawson to suggest the scheme which resulted in the construction of Westfield War Memorial Village.

The battle continued into early May with the 1st/5th Battalion continuing to take casualties. On 3 May the 1st/5th was moved to a hamlet called Frezenburg about 5 miles east of Ypres where it spent several days being heavily shelled. The battalion was pulled back to reserve trenches on 6 May when it were relieved by the 2nd Battalion, King’s Own, which was serving in the same brigade. On 8 May the Germans attacked the Frezenburg trenches in what turned out to be their last major offensive of Second Ypres.

About 12 Major Clough and about 40 men of the 2nd Battalion came in and told us that the Germans had attacked that morning in overwhelming strength and had taken the trenches, and that they were the only survivors of the Battalion. (R. Cavendish, qu. in The King’s Own)

The 1st/5th and some of the survivors of the 2nd Battalion were then involved in another counterattack which again failed with heavy losses. The casualties included Lieutenant Stanley Bates, Major Bates’ son (see also Chapter 7), who was killed, and Colonel Lord Richard Cavendish, who was wounded. Major Bates, the battalion’s second-in-command, had been invalided home a few days previously. Neither Colonel Lord Cavendish nor Major Bates returned to the battalion.

The 1st/5th’s casualties from 9 April to 11 May were 7 officers and 113 men killed and 14 officers and 416 men wounded. The battalion’s war diary notes that on the night of 11 May ‘the survivors of the Battalion, over 1,000 strong coming out, now slept in a hut and a very small barn.’

Private James Radcliffe (Cliffe) Mawson of the 1st/5th Battalion, King’s Own, died of wounds in the Second Battle of Ypres on St George’s Day, 1915. (KOM)

The King’s Own was heavily involved in the 141 day long Battle of the Somme in 1916. On the first day of the battle, 1 July 1916, the 1st Battalion went into action at Serre-Beaumont Hamel. Of the 507 other ranks who went into action on that day, 387 became casualties. They also lost many of their officers, including Major Bromilow who had been in command of the battalion for less than one month. The service battalions, the 7th and 8th Battalions, also both saw bitter fighting, and the two Territorial Battalions, the 1st/4th and Lancaster’s own 1st/5th, were frequently in the line and taking part in some of the more mundane duties of trench warfare, providing working parties.

The nature of the regiment and its battalions had changed as the war proceeded, with the Lancastrian flavour being diluted as drafts of men joined to replace the fallen and the wounded. There were, however, Lancaster men still involved in the first days of the battle. Sergeant James Parkinson, of Primrose Hill, Lancaster, was one of the men who left their trenches at 7.30 a.m. and advanced slowly across No Man’s Land, as if it was a parade ground drill, and was wounded by shrapnel in the upper part of his thigh when leading a party in bombing attack on the German trenches.

Corporal Jack Davies, a 27-year-old soldier, who lived at Hest Bank with his wife, was wounded in the advance, receiving a compound fracture of the left arm and a severe burn on the right arm. He was quickly evacuated, one of the many thousands of casualties who were, first to Eastleigh Clearing Hospital, near Southampton, and by 8 July was in Trafford Hall Hospital, Manchester.

The 1st/5th Battalion saw relatively little action in July, and their first involvement in the Battle of the Somme was night-time work digging communication trenches. This was an activity certainly not free from risk as the enemy would attempt to disrupt any work that was taking place, and do its best during the day to spot where the work was happening. On 1 August ten officers, twenty-eight non-commissioned officers and 350 other ranks were employed in the trench digging. Two other ranks were killed and seven wounded due to shelling. The work continued for the next couple of days. The loss of one soldier is recorded on 3 August but the German artillery bombardment of 4 August was heavy and claimed one officer wounded, twelve other ranks killed and a further forty wounded, with two men recorded as missing – lost somewhere in the confusion and dark. A similar action followed on the night of 14/15 August when the 1st/5th was ordered to send out 230 men to dig trenches which, at their closest point, came within thirty yards of German trenches. These trenches were to be used as a starting point for a subsequent assault by other units. The night was brightly moonlit and they came under heavy rifle fire. One officer and sixteen other ranks were killed and thirty-four other ranks wounded.

An un-named ‘Lancaster Pal’ wrote home in a letter dated 15 August:

It has been hard, dangerous work, all done under heavy shell and rifle fire. Unfortunately our losses were rather large last night, owing to our being so exposed and not having any cover until we had dug ourselves in. I am still fit, safe and sound. We are now about to start our long extended rest. We shall now have an opportunity to settle our nerves and enjoy our rest and parcels.

Private Walter Robinson, whose parents lived at 7 Abbey Terrace, Scotforth, wrote home: ‘We pioneers have the job of burying the dead, and today we have erected some bonny crosses over three graves.’ It is possible that one of these graves was that of Sergeant Herbert Dobson, who had won the military medal for leading a night-time patrol in December 1915, and was Lancaster’s first King’s Scout. He was killed on 9 August 1916 at Trones Wood, and was buried by his battalion. The grave was marked with a wooden cross carefully made by the battalion pioneers and hand-painted by Corporal Robert Bell, a painter and decorator before the war, who through the war, carefully painted the details of the deceased soldier on the wooden cross.

Anthony Hoyle was born in Overton, Lancashire, in 1875 of Elizabeth (née Maloy) and Anthony Hoyle. A veteran of the South African War of 1899–1902, he had served with an Active Service Company of the King’s Own Volunteer Battalion. By civilian occupation a plasterer’s labourer for T. & J. Till, in the First World War he enlisted in Lancaster and served in the 1st Battalion. He was wounded on 6 July 1916. Although heavily cut up on 1 July, the battalion had to remain in the front line for a full ten days to hold off German counterattacks. Hoyle was admitted to the Base Hospital, but died of his wounds on 12 July in the 2nd Stationery Hospital. He is buried in St Sever Cemetery, Rouen, in keeping with the British policy not to repatriate bodies. In the war, camps and hospitals were stationed on the southern outskirts of Rouen. The hospitals included eight general, five stationary, one British Red Cross, one labour hospital, and No. 2 Convalescent Depot. Although some of the dead from these hospitals were buried in other cemeteries, the majority were taken to the city cemetery of St Sever which had to be extended in September 1916. The cemetery contains 3082 burials of individuals from the Commonwealth, one French burial and one non-service burial from the war. Sergeant Hoyle left a widow who resided at 16 Primrose Street, Lancaster, and six children, the eldest of whom was serving with the Lancashire Fusiliers at Colchester.

Soldiers of the 1st/4th Battalion, King’s Own, on the Somme, 1916, Lewis Gun Teams. (KOM)

The hand-painted grave marker of Sergeant Herbert Dobson MM, one of more than 200 hand-painted by Corporal Robert Bell, of the 1st/5th Battalion, King’s Own. (KOM)

The Battle of the Somme continued until 18 November when the whole battle got bogged down in the mud, which eventually froze and made the land harder than ever to move over. The King’s Own suffered at least 953 officers and men killed, with an unrecorded number wounded, some of whom would die of their wounds in the coming months and years.

These are only three of the many military actions in which the King’s Own were involved during the war. At the start of the war the King’s Own consisted of five battalions. Of these, the 3rd (Special Reserve) Battalion remained in the UK throughout the war. The 1st and 1st/5th battalions were moved to France in August 1914 and February 1915 respectively as previously described. The 1st/4th followed them on 3 May 1915. All three were to remain on the Western Front for the rest of the war. The 2nd Battalion, by contrast, which had been rushed back from India at the outbreak of war and fought alongside the 1st/5th at the Second Battle of Ypres, was removed from the Western Front in November 1915 and spent the rest of the war fighting in the Macedonian campaign. Of the battalions formed during the war, the 7th and 8th were both sent to France in 1915 and remained on the Western Front until 1918. The 6th, however, saw action at Gallipoli from July to December 1915 before being moved to Mesopotamia, arriving at Basra on 27 February 1916. They remained in Mesopotamia for the rest of the war. The 9th Battalion spent a brief period in France in the autumn of 1915 before it was moved to Macedonia to fight in the same campaign as the 2nd Battalion.

There was, therefore, fighting in far more places than just the Western Front and the King’s Own was involved in much of it. As we will see in the next chapter, Lancastrians fought in many of these battles and campaigns, some of which we remember but many of which have now been all but forgotten.