CHAPTER ONE

RENNES-LE-CHÂTEAU AND ITS AREA

Non est ad astra mollis e terris via.

Not far from the Naurouze Gap which separates the eastern Pyrenees from France's central massif lies the village of Rennes-le-Château. Mediterranean chestnut, Hermes oak and cork oak all flourish here in the eastern Pyrenees. Broom grows prolifically and ubiquitously on the hillsides, and there are countless hectares of tough, drought-resistant bushes of the species which are native to Provence.

The eastern Pyrenees are cut by the valleys of the Agly, the Tech and the Tet; and the Agly has sculpted an interesting line of cretaceous marls. The neighbouring Corbières with their hard palaeozoic core seem to be fighting a stubborn rearguard action on behalf of the central massif.

Rennes and its immediate surroundings rest on cretaceous limestone: the area is rich in sharp, jagged crests with stark, singular profiles, labyrinthine caves and subterranean rivers and streams. Despite the heavy undergrowth and afforestation on most of the nearby slopes, the hill on which Rennes itself stands is comparatively bleak. Only the scant, tough, mountain grasses and an occasional shrub cover its ponderous limestone base.

This absence of cover would have appealed to its original neolithic settlers (some of whose stone axe-heads and other artefacts have been discovered in the area by M. Henri Fatin, the owner of the ancient Château Hautpoul) as well as to the Celt-related Tectosages (an interesting ethnic title probably meaning “wise builders or makers, skilled craftsmen”) who were probably living in Rennes at about the same time that Pericles was guiding the Athenians. The bare slopes of the hill on which Rennes-le-Château stands give its defenders a clear view of any potential enemies while they are still several kilometres away. Military strategists among the Romans, Visigoths, Septimanians, Merovingians, Carolingians and their successors would also have found Rennes an eminently defensible site.

Couiza lies on the main D118 road between the towns of Limoux in the north and Quillan in the south, while Rennes-le-Château it self is less than five kilometres south of Couiza. Montazels, which adjoins the western outskirts of Couiza, is a fascinating old hilltop village — “Mount Hazel” in its anglicised form, and some folklorists traditionally associate the hazel with wisdom. It was here in Montazels on April 11th, 1852, that Bérenger Saunière was born in a narrow, three-storeyed house with iron verandas overlooking the curious “Fountain of the Tritons”. The Tritons depicted on this fountain are reminiscent of dolphins in many respects, but their heads are grotesque. The foreheads are much too high for an aquatic mammal, or for a fish, and the rows of regular teeth look distinctly human. Some early artists portrayed Triton, the son of Neptune and Amphitrite, as a man down to the waist, the rest of him being a fish's tail. The statue in the Vatican museum which shows Triton abducting a nymph portrays him with a horse's forelegs, as well as a human torso from the waist up — rather like a centaur.

Ancient tradition places Triton's home just off the coast of Libya, where he is said to live with his parents in a beautiful golden palace below the sea.

This “Fountain of the Tritons” may well be a significant clue in the Rennes mystery. Firstly, Saunière built his watchtower looking out directly towards his old home beside that fountain in Montazels, and with the fountain just behind us, we photographed Saunière's tower during a research visit to Montazels in 1990. Secondly, we believe, the Rennes mystery has links with the Money Pit on Oak Island, Nova Scotia, which we studied in 1988, and interviewed Dan Blankenship, the site manager. The Money Pit is currently being explored by a syndicate called Triton Alliance with whom Dan is closely associated. Thirdly, there is a very curious legend concerning the birth of Mérovée, alias Merovech, alias Merovaeus, the founder of the Merovingian Dynasty. According to this legend, Mérovée's mother, the wife of King Clodion le Chevelu (Clodion the long-haired), was impregnated twice before Mérovée was born: first by Clodion, then by some sort of merman, sea-monster or aquatic demi-god while she was swimming. Was this the mysterious Triton (whoever or whatever Triton really was)?

The traveller who follows the banks of the River Aude from north to south, as it flows to the west of Rennes-le-Château, comes first to Alet-les-Bains, then Castel Nègre (the Black Castle) followed by the turning to the east which leads to Luc (meaning light). Once south of Couiza, the Aude trail leads through the village of Campagne, the town of Quillan and on to Belvianes. Immediately south of Belvianes, the river passes between two dramatic and curiously named natural features: to the west le Trou du Curé (the Priest's Hole, or the Priest's Canyon); to the east Les Murailles du Diable (the Devil's Ramparts). The Black Castle beside the Village of Light? The Priest's Canyon opposite the Devil's Ramparts? No more than fanciful and romantic local place names perhaps, but in view of the strange rumours and legends saturating Rennes and the surrounding area they may be a clue to something more.

It is equally interesting to follow the course of the River Sals, which means “salt”, and there is yet another strange coincidence here concerning names. Saunière can mean “salt-maker” and salt is a powerful religious symbol: it is a purifying agent used in rituals of exorcism; it represents the power of goodness and light; it heals and it cleanses; both literally and metaphorically it gives flavour and meaning to an otherwise dull and tasteless existence. Jesus himself told the first disciples that they were the salt of the earth. The Rennes mystery has connections with Shugborough Hall in Staffordshire, England, home of the extremely wealthy Admiral Anson. In the grounds of Shugborough Hall stands The Shepherd Monument: a mirror image in stone of Poussin's “Shepherds of Arcadia”. Staffordshire is a salt county. Natural brine wells up to the surface in many places there. So much salt is produced that cattle standing in what the locals call the “plashes” of natural brine soon become white with crystalline salt.

A small tributary of the Sals called the Rialsesse, which flows into it from the east, passes close to the site of the Tomb of Arques, flowing at the very foot of the limestone promontory on which the tomb stood until it was unaccountably razed by the new owner of the site in 1988. The demolished tomb had been erected by an American named Lawrence in 1903, and was an exact replica of the one with the Et in Arcadia Ego inscription featured in Poussin's canvas.

It was Visigothic practice in the fifth century, and probably for some years afterwards, to bury their kings surrounded by their royal treasures in secret chambers concealed below river beds. The technique was to dam the river and divert its course temporarily while the bed was excavated and the burial chamber prepared. Once the dead king and his treasures were safely interred, and the waterproof subterranean chamber properly sealed, camouflaging sand and gravel would be raked over the site and the dam demolished. The all-concealing river then resumed its original course. Within a few weeks it would be almost impossible to locate the site, and, even if it was located, without sufficient manpower to divert the river again, it would be almost impossible to profane the king's tomb. Unless, of course, a secret passage was constructed…perhaps from the base of a tomb on the bank?

Pierre Jarnac's Archives du Trésor de Rennes-le-Château reproduce our 1975 photographs of the Tomb of Arques and the two coffins it then contained. Jarnac records on the same page that a M. Adams says that the tomb also contains — or once contained — a very large iron wheel, fixed in the wall, and carrying an endless chain. It did not show up on our 1975 photographs, but that does not mean it wasn't there. It might simply have been out of camera range.

The Sals rises several kilometres southeast of Sougraine, and flows on northwest through Rennes-les-Bains. Shortly before entering this ancient village, the Sals is reinforced by the River Blanque, and immediately to the west of their confluence are three very curious and significant landmarks: the Dead Man; the Devil's Armchair and the Trembling Rock. Beside the road which follows the curve of the River Blanque, and immediately south of these three strange landmarks, lie the ruins of a very ancient mine; a few hundred metres south of that mine is a heritage.

As we follow the Sals through Rennes-les-Bains itself, we pass the ancient church where Boudet — at least as enigmatic a figure as Saunière — worked for so many years prior to the First World War, and the presbytery where he laboriously assembled his cryptic volume about the old Celtic language. This timeless settlement with its thermal springs — well-known since Roman times — has the same deep, secretive atmosphere that envelopes Rennes-le-Château.

From Rennes-les-Bains the Sals flows almost due north between the Pech Cardou to the west and the high slopes which hide the ruined Château Blanchefort to the east. Below Blanchefort juts the sinister Black Rock, and halfway up the mighty side of Cardou stands the White Rock: again that balance; again that challenge — it is as though the two cosmic forces of Good and Evil, Darkness and Light, Order and Chaos (central to the Gnostic beliefs of the Cathars who once thronged the Languedoc) are dramatically and repeatedly symbolised in so many of the rivers, mountains and landmarks of this mysterious region.

At the tiny hamlet of Pachevan, the Sals turns due east towards the little hillside village of Cassaignes. There is a mystery here, too. In the cemetery of Cassaignes, incongruous among the nineteenth and twentieth century tombs and memorial carvings which surround it, stands an ancient, weathered stone cross, unmistakably of octagonal Visigothic cross-section. It has probably stood there for fifteen hundred years. What mystery does it cover? To what secret hiding place does it point?

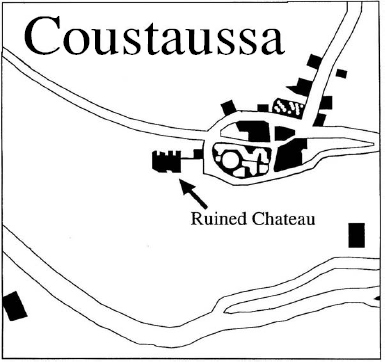

Coustaussa is the next hillside village. There is a ruined Château here, with gaunt stone fingers that point upwards starkly like the hand of a traveller who has died of thirst in the desert and still points accusingly at the merciless sun. In the cemetery of Coustaussa lies the body of the murdered priest, Antoine Gélis, savagely struck down by some unknown hand in his own presbytery, here in the village in 1893. A solitary and secretive old man, Gélis normally answered the door only to his niece, when she called with food or clean laundry for him. On the tragic evening when he neglected his own prudent rule, whoever — or whatever — got into his presbytery, attacked him with heavy iron fire-tongs, and finished him with an axe while he was apparently trying to struggle towards the window overlooking the street in a vain attempt to summon help. What seems even more sinister and macabre is that the murderer then coolly and calmly laid out the body — as solemnly and respectfully as a priest or an undertaker might have done.

There were three great pools of blood on the presbytery floor but there was not one telltale foot or fingerprint to be seen. Gélis had considerable sums of church money lying about the presbytery: none of these had been touched. A locked deed box, however, had been forced and the contents rifled. Very probably some interesting documents had been removed — but what were they? And what made them more important than the old priest's life? What strange, paradoxical, psychopathic type of killer could strike down a defenceless old man with an axe, and then spend vital getaway time in laying out the body?1

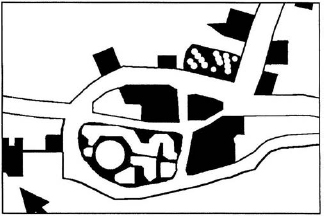

There is another mystery centred on Coustaussa, which would not have come to our attention without the invaluable help of M. Henri Fatin, the proprietor of Château Hautpoul in Rennes-le-Château. M. Fatin showed us around his fascinating and historic home, and very generously gave us several hours of his time. Among the many interesting theories he discussed with us was the possibility that the actual street layout of Rennes-le-Château had been deliberately designed to approximate to the form of an ancient “boat of the dead” — including the gigantic outline of a dead warrior, complete with helmet. He lies with his back to the north, his head to the east — towards Jerusalem, the Holy City. His feet are towards the west — the Isles of the Dead, the Twilight Lands of the Setting Sun. The casque, or helmet, of this dead warrior is very plainly outlined, and Château Hautpoul occupies the midpoint of his back, approximately where the keel of the boat would join the underside of the hull. Having once been made aware of such a possibility through our discussions with M. Fatin, we noticed that the outline plan of the village of Coustaussa also bears an uncanny resemblance to the helmeted head of a dead warrior. Were these original street plans laid out as gargantuan memorials to ancient lords and heroes? Pyramids decay; the deepest lines carved on stone become indecipherable as aeons pass: but streets, tracks and roadways last as long as men walk them. (Illustration page 13).

Outline Plan of the village of Coustaussa with possible “helmeted head”. (Note also that Coustaussa may well be linked

There is another possibility: deliberate designs of this size and scale are readily visible from above, and their outlines become clearer as the observer's distance from them increases. Compare this with the various giants and white horses cut into the chalk of several English hillsides, and the inexplicable lines of Nazca, which Erich von Däniken once maintained were intended for the use of ancient astronauts or aviators. In a mountainous district like that in which Rennes-le-Château is located there are numerous ridges, peaks and other viewpoints from which the layout of an entire village is clearly visible.

Almost due north of Rennes-le-Château, the Sals joins up with the Aude at Couiza, and, having briefly traced the courses of these rivers, we can centre our attention on Rennes itself and its relationship to the significant sites and landmarks nearby.

A bearing of zero degrees leads to the Black Castle. At 7 degrees we find Luc, the Village of Light; 39 degrees (significantly 13 x 3!) is the bearing for Coustaussa with its mysterious ruined Château and the grave of Antoine Gélis, its brutally murdered nineteenth century priest. A bearing of 55 degrees leads to Cassaignes, where the cemetery contains the ancient Visigothic cross — incongruous among the more modem memorials. The ruined Château Blanchefort is on a bearing of 72 degrees: exactly one fifth of the 360 degrees of a full circle, and exactly the size of each external angle in a regular pentagon. In Poussin's famous picture of the “Shepherds of Arcadia”, the geometry of the painting is believed by at least one expert to be based on a regular pentagon, which extends outside the frame. The centre of this pentagon is said to coincide with the head of the shepherdess. Some other investigators are convinced that pentagons feature prominently in the landscape and topography of the Rennes area, and, of course, the pentagon has been regarded for centuries as a potent magical symbol.

A bearing of 87 degrees from Rennes-le-Château points towards the mysterious cave in the Bézis Valley, near what the maps usually label the Berco Petito, but which Stanley James refers to as Berque Petite in his Treasure Maps of Rennes-le-Château. Taking a bearing of 105 degrees leads to Rennes-les-Bains; 114 degrees locates the village of Sougraine; 115 degrees takes us over to the Devil's Armchair; 117 degrees is the direct line to the Trembling Rock; the 121 degree line arrives first at the Dead Man and beyond that at the ancient mine close to the bank of the River Blanque where it runs parallel to the narrow, winding D14road connecting Rennes-les-Bains with Bugarach. The 147 degree bearing leads to the ruined Château of the Templars, which lies less than two kilometres to the west of Le Bézu.

Travelling due south from Rennes-le-Château on a bearing of 180 degrees brings the traveller to several more ancient mines. Exactly two kilometres due south of Rennes lies the Aven. The fascinating black dot which marks its location on the official map produced by the Institut Géographique National for the area is shown on the key as representing Entree de mine, d'excavation souterraine — entrance to a mine or subterranean excavation. Aven is close to the French word avenir with its sense of futurity, hopes, expectations and prospects. Merely a coincidence? Or is it another of those very curious verbal connections which appealed so strongly to the brilliant but devious mind of the author of La Vraie Langue Celtique, Abbé Henri Boudet?

A bearing of 202 degrees from Rennes leads to the village of Granès, while 205 degrees leads straight to the Roc de la Dent — the Rock of the Tooth — rising well over 1500 feet above sea level. At 220 degrees the track leads to the village of St Ferriol; and at 255 degrees to the village of Campagne, clustered around each bank of the Aude. The 261 degree line leads to the fascinating old hamlet of Campagne-les-Bains, with its ancient thermal source. A bearing of 285 degrees from Rennes takes the traveller to Espéraza — which is something between a large village and a small town. The hamlet of Gamaud is on a bearing of 300 degrees from Rennes-le-Château, while Saunière's birthplace of Montazels is on a bearing of 325. The interesting little town of Couiza, with its imposing Château, stands just across the river from Montazels, and is on a bearing of 340 degrees from Rennes. This is the last of the landmarks on our circular tour of the immediate vicinity.

Here in Couiza, inside the church itself, there is a very interesting memorial to the dead of the First World War. It seems to be generally accepted that the man responsible for its unusual design was a priest named Duvilla, who had been a teacher at the Grand Seminary and was widely acknowledged to be a man of great scholarship. Nominated to the living of Couiza in 1917, he had previously been the priest at Axat. Gérard de Sède states clearly and categorically that Boudet and Duvilla knew each other well and that Boudet was a frequent visitor to Axat. Certainly Boudet's tomb is there, and it carries a very strange inscription. Even more significantly, de Sède says that when Archduke Jean (John or Johann) of Habsburg visited Axat he lodged with Boudet's step-sister.

The rather unusual War Memorial which Duvilla designed contains some very subtle symbolism which de Sède is convinced relates to Freemasonry, and particularly to a Scottish Masonic Degree: Knight of the Red Cross, or Rosicrucian Knight. He also argues, quite persuasively, that the rest of the symbolism relates to the Holy Roman Empire and the Imperial Habsburg family.

The Rennes mystery seems to be like a complicated piece of embroidery: the threads repeatedly cross over one another and join up again in unexpected places. It is also curiously like a spider's web. Toile d'araignée is the French phrase for “spider's web”, and, if we pursue Boudet's concern with paronomasia, it is not too difficult to see étoiles de Rennes—the stars of Rennes — hidden in the spider idea. At least one of the ancient coded gravestones relating to the enigma bore a primitive design which looked very much like a spider. And are the “stars” of Rennes its glittering hidden jewels?

The unusual War Memorial at Couiza appears to link up with Freemasonry, Rosicrucianism and the Habsburgs; and to link the learned Duvilla, the scholarly Boudet and the strange code on the latter's tomb at Axat.

But there is far more than this in the geographical location of Rennes-le-Château. It is only a few kilometres from the nearest fortification foxing part of the famous circuit of Cathar castles of the Languedoc with their ethos of tragic gallantry and their atmosphere of brooding mystery.

There is Carcassonne — the most amazing medieval citadel still in existence. There is the Château of Foix with its three great towers like something out of a particularly dramatic Gothic romance. There are the four great ruins at Lastours, each on its own mountain peak: Cabaret, Tour Régine, Fleur Espine and Quertinheux. Below them the rushing torrents of the Orbiel and the Grésillon have cut deep gorges as they thunder down from Montagne Noire. There is the fortified village of Minerve, where de Montfort was responsible for the deaths of 140 Cathar martyrs in 1210. There is Montségur, standing high on its almost inaccessible rocky pillar (The Pog), where four intrepid Cathars once stole away from the beleaguered fortress by night to keep “the treasures of their faith” out of the hands of the Catholic Crusaders. (Was this the mysterious pecuniam infinitam of the Inquisition records?) And there is Usson, where tradition says the Cathars took it.

There are the elongated defences of Peyrepertuse; the squat, square towers of Puivert; the inaccessible fortress on its crag at Puilaurens, documented in the tenth century, and probably much older. (Is there a possible connection here, too, with the Lawrence family of the Tomb of Arques…laurens…Lawrence?)

Finally, there is Quéribus, standing out like a solitary surviving tooth in an ancient jawbone; it overlooks the Grau de Maury Pass. The Celts were probably its first defenders, then the Visigoths. Here in 1256, the Cathars made their last stand. As well as being a fortress, Quéribus was a signalling tower in contact with Peyrepertuse.

Enough energy has been expended on studying the geometry of Rennes to put a dozen communication satellites into orbit; and enough detailed maps and drawings have been made to supply a university geography faculty with ample material for a full three year course. Not all the geographical geometricians agree on which patterns are the most important, but even a cursory look at the landmarks is enough to show its potential for experimental work in this field.

For example, one interesting and reasonably convincing pentacle (a five pointed star based on a central regular pentagon) can be located with its points at Rennes-le-Château, the ruins of Château Blanchefort, the menhir south-east of Rennes-les-Bains and due east of the Source of the Madeleine, the ancient Château of the Templars east of le Bézu and south of la Pique, and the ruin marked just north of the narrow D46 road connecting Granès and le Bézu. This same ruin lies at the south of the Serre de Lauzet.

An even more interesting pentacle has its most northerly point on Le Berger (which means the Shepherd, and may have links with the Poussin painting) and its other points on the Château at Arques, the Bézis Valley where Stanley James found the heavily silted and partly collapsed cave, the peak of Cardou, and the ancient village of Peyrolles. The centre of this pentacle is the spot where stood the enigmatic Tomb of Arques — the image of the one in the Poussin painting — until it was demolished in 1988.

It is not only the pentacle which is believed to be significant in the Rennes geometry: a triangle — especially an equilateral triangle — is also worth noting. Take the Fountain of the Tritons in Montazels (just in front of the house where Bérenger Saunière was born) as the first point; draw a line from there to the cemetery at Cassaignes where the old Visigothic marker cross has stood for centuries. The second line connects Cassaignes to the Aven which lies due south of Rennes and due south of the ancient, ruined mines. The third line connects the Aven with the Fountain of the Tritons. But this particular triangle has a triple significance: it is, in fact, three equilateral triangles inside one another: all sharing a common apex at the Fountain of the Tritons in Montazels. A line drawn from the Château at Rennes to the Château at Coustaussa intersects the frame of the original triangle at Les Bals in the south-west and Camp Grand in the north-east. This new line creates the second equilateral triangle enclosed in — and partly common with — the first. A new line drawn parallel to the line connecting the two ancient Châteaux and passing directly through Roque Fumade creates the third equilateral triangle. This Roque Fumade could be much more interesting and important than has generally been recognized by previous investigators.

If, as some serious researchers have suggested, there was considerable gold-smelting activity going on in subterranean passages and chambers during the long and chequered history of Rennes-le-Château, the fumes from that smelting had to emerge somewhere. Even the most ancient mines had their primitive ventilation systems, which were essential to enable the miners to work at all. Some of these “systems” were simply natural and fortuitous draughts and currents of air in the shafts and tunnels; others were augmented by air holes dug deliberately, and by crude wooden air-gates and flaps operated by the workmen or slaves. It is more than possible that smoke from an underground smelting operation could carry for hundreds of metres along one of these ventilation systems and emerge through a fissure a long way from its source — giving rise to the name Roque Fumade at the point where the fissure actually allowed the smoke to escape.

As well as the mysterious pentacles and equilateral triangles which fit remarkably well on to the significant landmarks of Rennes-le-Château, there is the question of the Zodiac.

It is a fundamental tenet of Hermetic philosophy — the belief that certain Great Masters of Wisdom have possessed vital secrets since very ancient times — that certain deep cosmic truths lie hidden behind symbols in art, music, literature, configurations in the landscape and in the sky. A message intended for generations yet unborn might be preserved, as we suggested earlier, in the layout of streets and roads: how much longer it could be preserved in the constellations. Hermeticists and alchemists set great store by the aphorism “as above, so below”. Hieroglyphics carved in the hardest rock will eventually be eroded and erased: hieroglyphics set in the stars will last a great deal longer.

Astronomers and astrologers would agree in defining the Zodiac as that zone of the observable sky within which the paths of the sun, moon and planets of the solar system appear to lie. Since the planetary orbits deviate only slightly from a shared plane, an observer on our earth sees the sun, moon and planets moving in a comparatively narrow band – a tiny fraction of the vast celestial sphere: they move, in fact, rather like the figures of saints around a medieval church clock when the hours strike.

At least as long ago as 3,000 B.C. in Mesopotamia, the fixed stars against which the planets moved were allocated to various arbitrary groups, and were usually given names corresponding to living things: the goat, the raven or the serpent. The Greeks called these constellations which were passed by the planets on their travels the zodialws kyklos— the circle of the animals.

Undoubtedly aware of the “as above, so below” aphorism, Mrs. Katherine Maltwood, the well-known writer and sculptor, made a detailed study of the journeys of King Arthur's Knights from Camelot (which she interpreted as South Cadbury Castle) to the Isle of Avalon. Using large scale maps and aerial photographs, she put forward a careful and well balanced argument for the existence of a set of zodiacal figures in and around Glastonbury which more or less coincide with the celestial zodiac. Mrs. Maltwood demonstrated that when a stellar map of the right scale is laid over the map of Glastonbury, the stars making up the heavenly zodiac constellations fall within the figures she claimed to have discovered on the ground. At the top of the circle, near the town itself and encompassing the Tor, is Aquarius, originally an air sign in the old earth-air-fire-water theory. The Glastonbury Zodiac shows him as a phoenix, a resurrection symbol. The Tor lies inside the head of this phoenix, which is turned to face Chalice Hill, where the ancient Chalice Well was once reputed to have been the hiding place of the Holy Grail in the Christian traditions centred on the adventures of St. Joseph of Arimathea. Outside the circle, Mrs. Maltwood located the figure of The Great Dog, presumably set there to guard this Temple of the Stars. Upon the dog's head are Head Drove and Head Rhyne, which are man-made drainage ditches; in an appropriate spot above his head is Earlake Moor, while his tail contains the tiny hamlet of Wagg! Glastonbury is not alone in being strongly suspected of having an earthly zodiac corresponding to the celestial one: researchers believe that they have found similar outlines at Kingston-upon-Thames, Nuthampstead, Banbury, Wirral, Durham, Edinburgh and Glasgow.

And so back to the Rennes-le-Château area where aspects of Henri Fatin's lengthy researches tend to confirm some of Elizabeth van Buren's ideas about a zodiac on the ground in the area. Aquarius, for example, can be located over the ancient Visigothic cross in the cemetery at Cassaignes. Scorpio, also seen as a dragon, is in the immediate vicinity of Rennes-le-Château itself, and – very curiously – the dragon's mouth is close to Roque Fumade, the Smoking Rock. Rennes-les-Bains is part of Gemini, the Twins.

We move next to smaller scale studies in greater detail; from the wide geography of the ground with its possibilities of equilateral triangles, pentacles and zodiac figures, it is interesting to look at the designs of Château Hautpoul, the Church of St. Mary Magdalen, and the work which Bérenger Saunière carried out in and around the church prior to his death in 1917.

The Château Hautpoul is impressively ancient. It is impossible to say with any degree of certainty whether the Celtic Tectosages were responsible for the first fortification on its present site, but they could well have been. Certainly, aspects of its architecture show Roman influence of the type which is still to be seen at Rennes-les-Bains, and these Roman characteristics were most probably expanded and developed by the Visigothic successors to Roman Gaul. There may have been an Arabian influence later, then a Frankish one. Spanish nobles came and went. Demolitions, repairs, additions, renovations and expansions were apparently made from time to time. Today the Château belongs to Henri Fatin, whose father, Marius, acquired it at the end of the Second World War. Marius had made a lengthy and detailed study of their fascinating home prior to his death, and Henri has continued and expanded this work. Between them the Fatins have produced considerable evidence suggesting that there is much strange symbolism contained within the design and structure of their crumbling Château. One of their most remarkable ideas is that the twelve threshold stones of the Château represent the Twelve Apostles. They might also, of course, represent the twelve signs of the Rennes Zodiac.

What we ourselves found particularly impressive during our recent studies of Château Hautpoul under M. Fatin's guidance were the egg-shaped oubliette, the very old barrel-ceilinged vaults, and the remarkable similarity between two ancient Roman-style arches in Château Hautpoul and the scenes carved between the two arches on the dalle du chevalier (the knight's gravestone). This stone dates from the sixth, seventh or eighth century, and is the one which Saunière discovered when it was lying face down in the floor of his church. It is now on prominent display in the museum. M. Fatin also showed us a finely drawn plan of one of the ancient Château doors. Once he had pointed it out, we could clearly see that these particular doors had been deliberately constructed to resemble exactly a knight's helmet from an early period, probably the eleventh or twelfth century. When this symbol is combined with M. Fatin's other theories concerning the overall layout of Rennes as a “boat of the dead” conveying the body of a giant warrior, it is possible that this enigmatic Château holds keys to more than one of Rennes-le-Château's mysteries, even if it is not directly linked to the secret of Bérenger Saunière's inexplicable wealth.

The site of what was once Bérenger Saunière's domain is also very interesting. The layout of his little “park” behind the tower and the terraces is unusual. It has a central circle from which radiate three triangles or pointers, only two of which are complete. If we complete this third one and follow the direction which it indicates, it leads directly to the first Station of the Cross inside the church. Part of Stanley James's theory, which he has worked out in minute detail in The Treasure Maps of Rennes-le-Château, is that each Station of the Cross indicates part of the route a treasure hunter must follow.

The lad who holds the water in which Pilate is washing his hands is black. Is this Saunière's way of hinting that the treasure hunter must pay attention to the tomb of Marie de Nègre? Yet by the time he had erected these Stations of the Cross, Saunière had already obliterated the inscription on her gravestone. Another example of his strange and tantalising sense of humour, perhaps? The figure on Pilate's right (which may be meant to represent a Jewish priest) is holding a golden coin, or perhaps a nugget. The hand that holds this piece of gold could also be pointing to its source. If it is, in fact, a nugget rather than a coin, is it meant to indicate one of the missing nuggets from the drawstring bag with a hole in it that lies at the foot of the Hill of Flowers on the mural behind the confessional? Curiously, the line from the incomplete pointer in the “park” passes through the centre of this mural. It either touches — or passes very close to — the holed money bag on its way to the First Station. There is much more to be said about clues of this kind in the pictures and statuary that Saunière left in his church, but it will be dealt with more fully in Chapter Six: Codes, Ciphers and Cryptograms.

The Magdalen Tower, which once housed part of Saunière's library, has become almost synonymous with the mystery of Rennes. It is featured prominently on the covers of many of the books about the enigma and among their inside illustrations. It is also one of the most popular of the Rennes postcards. It looks out directly towards Montazels and the weird Fountain of the Tritons. It commands wide views of the surrounding countryside. It is eminently defensible, especially for a strong, athletic man like Saunière. Strangest of all: it has a steel door. If an intruder comes over the parapet, the steel door can be slammed to prevent his getting into the main room below. If he bursts into the ground floor room, escape is possible up the stairs and the steel door can then be slammed against his ascent.

It may not be unduly melodramatic to suggest that certain dangers still lurk in Rennes-le-Château, and that those sinister forces were much more real, and much more imminent, for Saunière a century ago than they are for today's investigators. Maurice Guinguand reports the accident which killed a local notary who had asked Saunière to help him with Latin translations concerning titles to land that had belonged to the Fleury family. This man was said to have been out shooting with Saunière when it happened. Gérard de Sède tells of the grisly — and still unsolved — murder of the elderly Antoine Gélis. He also recounts the mysterious deaths of Rescanière and Boudet — both priests of Rennes-les-Bains — after they had been visited by two strangers. He also tells how three unidentified corpses were found in Saunière's garden in 1956. All of which makes a steel door a sensible precaution.

The Grotto, on which Saunière laboured for so many hours with the stones he brought back from his long, mysterious walks, and the Garden Calvary, both stand inside an equilateral triangle the northern edge of which runs parallel to the southern wall of the church and very close to it.

The church is very small and extremely old. The present building apparently stands on Visigothic or Merovingian Christian foundations, and, in all probability, there was some sort of pagan temple on the site well before the Christian era. The Stations of the Cross, the murals, the statues and the stained glass windows were placed there at Saunière's instigation, or, as some researchers would have it, at Boudet's instigation with Saunière as Boudet's agent and “front man”. Either way they must rank among the strangest church ornaments in the world. A detailed attempt at their decipherment must wait for the appropriate later chapter, but in broad outline the stained glass depicts five scenes: Mary Magdalen with Jesus; Mary and Martha of Bethany; the resurrection of their brother, Lazarus; the mission of the Apostles; and Jesus on the cross. There are nine statues: St. Joseph the Carpenter; the Virgin Mary; St. Anthony of Padua (the Hammer of the Heretics) who lectured in theology at Toulouse; St. Antony the Hermit with his traditional bell and pig; St. Mary Magdalen with a cross, and her flask of precious nard; St. Germaine, the shepardess, with her apron full of roses; St. Roch, defender against the plague; St. John the Baptist in the act of baptising Christ — strangely enough by influxion with a silver shell rather than by the total immersion method which John himself would actually have practised in the River Jordan; and, lastly, the four angels making the sign of the cross above the dish of holy water held above the shoulders of a furious and vicious looking demon. He is probably meant to represent Asmodeus, the legendary guardian of Solomon's treasure in Jerusalem. The demon's empty right hand is said to have held a trident in years gone by.

So far we have given a very short summary of the mystery and an equally brief survey of the area in which it is set: the land and the landmarks; the enigmatic old towns and villages; the challenging rivers and mountains; the uncanny symbolism of the decaying Château Hautpoul and the bizarre decorations in the church of St. Mary Magdalen The setting is undeniably strange — as strange as the semi-visible land zodiac which seems to impinge on Rennes-le-Château and the persistent triangles and pentacles connecting several significant local sites. But if the setting seems strange, the history is stranger, and we move next to an outline of the events that this tiny hilltop village has witnessed over many centuries.

1The authors are deeply indebted to their friend, M. Rousset, the doyen of Coustaussa, who most kindly and helpfully assisted them to find their way around the village, and to locate the tomb of Father Gélis. M. Rousset's courtesy is most warmly appreciated.