spice basil

spice basil

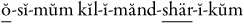

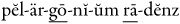

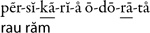

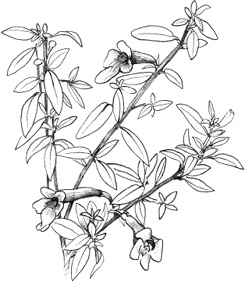

Although listed as O. micranthum in many manuals, O. campechianum has priority of publication. Campeche is the name of a state and town in Mexico. This is a basil native to the New World, where it is called albahaca, albahaca cimarrona (Puerto Rico), albahaca silvestre (Guatemala), or albahaca montés (El Salvador). In the Lesser Antilles it goes by balm, fon basin, or fonboysa. It may be cultivated in Latin America but is often gathered from the wild for culinary and medicinal uses. This basil is cultivated in North America as “Peruvian basil.”

This annual to 2 feet (60 cm) is very similar to sweet basil, differing in minute botanical characteristics. However, it can be easily distinguished from sweet basil by the brown nutlets (black in sweet basil) and the straight hairs (curved in sweet basil). Cultivation is as for O. basilicum.

Important chemistry: The essential oil from the leaves of O. camphechianum has 16 to 52 percent iso-eugenol, 4 to 23 percent 1,8-cineole, 11 to 23 percent beta-caryophyllene, and 4 to 23 percent beta-elemene, providing a eucalyptus-carnation odor.

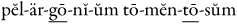

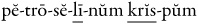

lemon basil

Lemon basil is a hybrid series derived from O. basilicum × O. americanum and first introduced into the United States from Thailand about 1940. Not all these hybrids are lemon-scented as the common and specific names would indicate. We have purchased seeds or plants of this hybrid as ‘Anisatum’, “ball basil,” ‘Bush Green’, ‘Citriodorum’, ‘Dwarf Bouquet’, ‘Dwarf Italian’, ‘Green Globe’, ‘Green Ruffles’, ‘Holly’s Painted’, ‘Lemon’, ‘Minimum’, ‘Puerto Rican’, ‘Spicy Globe’, ‘Sweet Dani’, ‘Thai Lemon’, or even “sacred basil.” ‘Lesbos’, originally from Greece and introduced into cultivation by the Rev. Douglas Seidel, is a rather unique growth form for its tight column, thus providing an alternate name of ‘Greek Column’. ‘Aussie Sweetie’ is very similar but supposedly originated from Greece via Australia. The variegated version of ‘Lesbos’ has been patented (U.S. PP16,260) by Sunny Border Nurseries, Kensington, Connecticut, as ‘Pesto Perpetuo’.

Classical O. basilicum has a large fruiting calyx (6 mm long) and stems are smooth or coated with tiny hairs on two opposing sides, while classical O. americanum has a small fruiting calyx (4 to 5 mm long) and stems with hairs distributed equally around the stem. A plant with a large calyx and hairy stems or a plant with a small calyx and smooth stems most likely is a hybrid of these two species.

The oil of O. ×citriodorum has been reported to be antifungal.

Important chemistry: The essential oil of lemon basil is reported in the chemical literature as rich in 55 to 99 percent citral (geranial plus neral); a selected form is ‘Sweet Dani’ with 34 percent geranial and 22 percent neral in the leaf oil. ‘Dwarf Bouquet’ has 43 percent linalool and 10 percent beta-caryophyllene. ‘Green Ruffles’ has 35 to 43 percent methyl chavicol and 2 to 25 percent linalool. ‘Holly’s Painted’ has 35 percent linalool, 29 percent methyl chavicol, and 13 percent 1,8-cineole. ‘Aussie Sweetie’ has 9 to 49 percent trans-methyl cinnamate, 9 to 16 percent linalool, and 5 to 6 percent 1,8-cineole, while the very similar ‘Lesbos’ (‘Greek Column’) has 49 percent trans-methyl cinnamate, 13 percent linalool, 11 percent methyl eugenol, and 10 percent 1,8-cineole. ‘Puerto Rican’ has 57 percent trans-methyl cinnamate and 22 percent linalool. ‘Spicy Globe’ has 36 percent linalool and 14 percent beta-caryophyllene.

tree basil

French: basilic en erbre, basilic de Ceylan, basilic Seychelles, basilic salutair, baumier

Hindi: vriadha tulasi, ram tulsi, Hindi-ban

Thai: kaphrao-chang

This species, translated as the “very pleasing basil,” is known locally as tea bush in Africa, but it is widely cultivated in India and Latin America and by serious basil buffs in North America. This shrubby perennial can grow to almost 10 feet (3 m) high and has reddish brown nutlets that produce mucilage when placed in water.

This is also known in the trade as tree basil, shrubby basil, green basil, North African basil, or East Indian basil. The seed line currently offered in North America as East Indian basil originated in Zimbabwe and was introduced by Richters in 1982. The seed line currently offered in North America as West African basil originated in Ghana and was introduced by Richters in 1995. Two subspecies are known, subsp. gratissimum and subsp. iringense Ayobangira ex Paton. The former subspecies includes what is sometimes designated as O. viride Willd., the fever plant or mosquito plant, also called thé de Gambie in French. Other species cited in the essential-oil literature, such as O. caillei A. Chev., O. dalabense A. Chev., O. suave Willd., O. trichodon Gürke, or O. urticifolium Roth, belong to this species.

Tree basil has distinct chemotypes: thyme-, clove-, lemon-, rose-, cinnamon-, and carnation/herb-scented. The clove-scented form is reputed to be antimicrobial and a mosquito repellent. The oil is an effective anti-trypanosomatid. An unnamed chemical form is reputed to be effective against ticks.

Cultivation is as for O. basilicum.

Important chemistry: Thyme-scented tree basil (sometimes designated as O. viride) has 19 to 72 percent thymol, 0 to 27 percent gamma-terpinene plus (E)-ocimene, trace to 11 percent eugenol, and 0 to 16 percent p-cymene with up to 14 percent 1,8-cineole. Cinnamon-scented tree basil has up to 67 percent ethyl cinnamate. Clove-scented tree basil (sometimes reported as O. suave or O. trichodon) has trace to 98 percent eugenol, trace to 40 percent beta-caryophyllene, trace to 26 percent (Z)-ocimene, trace to 14 percent iso-eugenol, trace to 12 percent alpha-copaene, and trace to 10 percent beta-elemene, sometimes with up to 47 percent methyl eugenol and/or 47 percent methyl isoeugenol. Superior clove-scented cultivars, named ‘Clocimum’ and ‘Clocimum-3c’, have 60 to 95 percent eugenol and moderate oil yields. Lemon-scented tree basil has 65 percent geranial plus neral and 25 percent geraniol. The rose-scented tree basil has 85 to 88 percent geraniol in the leaves. The carnation/herb-scented tree basil has 40 percent beta-caryophyllene and 30 percent germacrene D. Ethiopian plants have a leaf oil with 23 percent (Z)-beta-ocimene, 17 percent delta-cadinene, 14 percent beta-caryophyllene, and 11 percent gamma-muurolene. A pine-scented form from Nigeria (as O. suave) has 26 percent sabinene and 24 percent beta-caryophyllene.

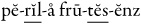

camphor basil

Hindi: Hindi-kapur tulsi

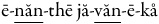

The camphor basil is named after Mt. Kilimanjaro in Tanzania and has been introduced into Asia, Europe, South America, and North America. The overall appearance of this annual is similar to that of sweet basil, reaching 6 feet (2 m). ‘Cattail Camphor’ is probably a hybrid of this species with O. americanum. ‘African Blue’ is probably a hybrid of O. kilimandscharicum with O. basilicum ‘Dark Opal’ discovered in 1983 by Peter Borchard of Companion Plants.

The oil of camphor basil is reputedly anti-fungal.

Cultivation is as for O. basilicum.

Important chemistry: Typically the camphor basil produces 17 to 80 percent camphor and up to 42 percent linalool, 17 percent limonene, and 10 percent 1,8-cineole in the essential oil of the leaves. However, O. kilimandscharicum growing wild in Rwanda has been reported to have 62 percent 1,8-cineole, providing a eucalyptus-scented form. The oil of ‘African Blue’ has 55 percent linalool, with 12 percent camphor and 12 percent 1,8-cineole, providing a strong balsamy scent with a hint of turpentine.

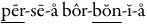

holy basil

French: basilic sacré, basilic des moines

Hindi: sri tulsi (purple), Krishna tulsi (green)

Thai: kaprou/kaphrao, bai grapao

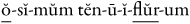

The holy or sacred basil has been known as O. sanctum in most manuals, but O. tenuiflorum, meaning “slender flowers,” is conspecific and has priority of publication. This species is seldom seen in the United States; O. americanum var. pilosum ‘Spice’ often substitutes in catalogs. We have been able to obtain O. tenuiflorum in North America only as plants labeled ‘Purple Tulsi’ and in packets of seeds from Thailand labeled “holy basil.”

‘Spice’ is generally hairy, with long, thin hairs on the stems, leaves, calyces, and flower stalks. While often confused with holy basil in the seed trade, no morphological characteristics relate these two species. The large leaves, elongate inflorescence, stalked bracts, and mucilaginous nutlets serve as distinguishing characters to separate ‘Spice’ from O. tenuiflorum. Holy basil occurs in both green- and purple-leaved forms.

Studies on the uses of holy basil have, unfortunately, rarely designated the chemotype used. Medicinal uses of holy basil have shown some promise in a variety of experimental areas, but many claims should be viewed as more hype than good science until replicated and correlated with chemotype. Leaves of holy basil have an antifertility effect when ingested, according to one researcher, but more research is needed. An ethanolic extract of holy basil has been reported to reduce blood glucose in rats and is reported to prevent smooth-muscle spasms, while a crude aqueous extract has been shown to potentiate hexobarbitone-induced hypnosis in mice. The leaf extract may have radioprotective effects. In addition, some adaptogenic (antistress) activity of holy basil has been reported on experimental animals. Holy basil has also been reported to enhance the physical endurance and survival time of swimming mice, prevent stress-induced physical ulcers in rats, and protect mice and rats against the liver toxicity induced by carbon tetrachloride. Holy basil also promotes glucose utilization different from the action of insulin. The eugenol and methyl eugenol content impart an antifungal, antibacterial, and anthelmintic activity to the oil of holy basil. The fixed oil of the seeds is anti-inflammatory, reduces fevers, and relieves pain. Leaves of O. tenuiflorum also repel mosquitoes.

Ocimum tenuiflorum

Cultivation is as for O. basilicum.

Important chemistry: Lemon-scented holy basil has about 70 percent gernial plus neral. The clove-scented holy basil has 13 to 86 percent methyl eugenol and 3 to 34 percent beta-caryophyllene, sometimes with up to 23 to 62 percent eugenol, 10 to 14 percent caryophyllene oxide, and 12 percent beta-elemene. The anise-scented holy basil has trace to 19 percent 1,8-cineole plus (Z)-ocimene, 15 to 87 percent methyl chavicol, and 0 to 11 percent beta-bisabolene. The medicinal-spicy-scented holy basil has 70 percent chavibetol (betelphenol) and 20 percent eugenol. The balsamic-scented holy basil has 30 to 33 percent beta-bisabolene, 16 to 20 percent (Z)-alpha-bisabolene, and 2 to 12 percent methyl chavicol. Holy basil from India has been reported with 17 percent beta-caryophyllene as the primary constituent.

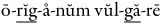

Key:

1. Leaves pinched at tips; mouth of calyx closed after pollen-release by up-curved lower lip; median lobes of lower lip of fruiting calyx shorter than upper lip; shrubs or undershrubs................ O. gratissimum

1a. Leaves tapering to the tip or rounded; mouth of calyx more or less open after pollen-release; median lobes of lower lip of fruit calyx as long as or longer than upper lip; herbs occasionally with stems slightly woody at base........................................................................................ 2

2. Leaves tapering to the tip......................................................................... 3

3. Fruiting calyx 4 to 5 mm long................................................................... 4

4. Stems hairy, hairs directed downward or spreading, distributed equally around the stem...................................................................................... O. americanum

4a. Stems smooth or coated with tiny hairs on two opposing sides................ O. ×citriodorum

3a. Fruiting calyx 6 to 7 mm long................................................................... 5

5. Stems hairy, hairs directed downward or spreading, distributed equally around the stem............................................................................... O. ×citriodorum

5a. Stems smooth or coated with tiny hairs on two opposing faces........................... 6

6. Pedicels divergent at right angles, decurved in fruit, not clearly separated; calyx 6 to 7 mm long in fruit, with appressed, stiff, rather short hairs outside, smooth within; nutlets brown; hairs straight.................................................. O. campechianum

6a. Pedicels short, erect, calyx 6 mm long in fruit, with long, straight, stiff hairs inside; nutlets black; hairs curved................................................. O. basilicum

2a. Leaves blunt at the tip............................................................................. 7

7. Calyx tube completely smooth within; nutlets unchanged when wetted.................................................................................... O. tenuiflorum

7a. Calyx tube with a ring of hairs at the throat; nutlets mucilaginous when wet......................................................................... O. kilimandscharicum

O. americanum L., Cent. pl. I 15. 1755.

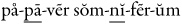

Key:

1. Stem indumentum mainly of short, retrorse, adpressed hairs with long hairs at nodes........................................................................................................... var. americanum

1a. Stem indumentum with long spreading hairs only..... var. pilosum (Willd.) Paton, Kew Bull. 47:426. 1992.

Native country: Spice and hoary basils are widely distributed in tropical and southern Africa, China, and India; naturalized in southern Europe, Australia, and tropical South America.

General habit: Spice and hoary basils are annuals or short-lived perennial herbs, 15 to 70 cm high, woody at the base.

Leaves: Leaves are narrowly egg-shaped to lance-shaped, smooth, light green, 110 to 55 × 4 to 25 cm, leaf stalk nearly half the leaf length; margin is slightly toothed.

Flowers: The inflorescence is lax, 13 to 18 cm long. Bracts, longer than the calyx, are stalked, egg-shaped, with pointed tip, glandular, hairy, with long hairs on the margins. The corolla is twice as long as the calyx, white, hairy on the outside.

Fruits/seeds: Nutlets are gray-black to black, lustrous, and show copious mucilage when moistened.

O. basilicum L., Sp. pl. 833. 1753 (including O. minimum L.).

Native country: Sweet basil is native to the Old World tropics.

General habit: Sweet basil is an annual herb, 0.5 to 1 m high, woody at the base. Stems and branches smooth or slightly hairy when young.

Leaves: Leaves membranaceous, egg-shaped to widest at the center with the ends equal, 3 to 5 cm long, tapering to the tip, base wedge-shaped, margin smooth-edged to fewtoothed, almost smooth or hairy; leaf stalk 1 to 2 cm.

Flowers: Inflorescence is simple or branched. Bracts are lance-egg-shaped, about as long as the calyx, 2 to 3 mm. Corolla is white, pinkish, or violet, twice as long as the calyx.

Fruits/seeds: Nutlets are dark brown, pitted, swelling in water.

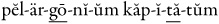

O. campechianum Mill., Gard. dict. ed. 8. #5. 1768 (O. micranthum Willd.).

Native country: O. campechianum is native from Florida to Brazil.

General habit: Plants are essentially annual but sometimes shrubby, up to 60 cm high.

Leaves: Leaves are parallel-sided egg-shaped to broadly egg-shaped, 2 to 9 cm long, tapering or blunt at the apex, toothed or almost smooth-edged, minutely hairy to almost smooth.

Flowers: The calyx is 6 to 7 mm long in fruit. The white corolla is spotted with purple, 4 mm long.

Fruits/seeds: Nutlets are dark brown to black, tapered to a point, producing moderate to heavy mucilage in water.

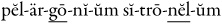

O. ×citriodorum Vis., Linnaea 15:Litteratur Bericht 102. 1841 (O. citratum Rumph., O. basilicum L. var. anisatum Benth., O. dichotumum Hochst ex Benth in DC.).

Native country: According to Alan Paton and Eli Putievsky, “O. ×citriodorum refers both to the products of a cross between O. basilicum and O. americanum and to the entities produced by the doubling of the F1 chromosome number, as these forms are morphologically indistinguishable.” The type of O. ×citriodorum is probably an allohexaploid (six times the basic chromosome number in an interspecific hybrid).

General habit, leaves, flowers, and fruits/seeds: The morphological characteristics combine a range between the two closely related parents. Classical O. basilicum has a large fruiting calyx (6 mm long) and a stem that is smooth or coated with tiny hairs on two opposing sides, while classical O. americanum has a small fruiting calyx (4 to 5 mm long) and stems with hairs distributed equally around the stem.

O. gratissimum L., Sp. pl. 1197. 1753.

Native country: Tree basil is native to tropical Africa.

General habit: Tree basil is a perennial herb, 0.6 to 3 m high, woody at the base. Stem and branches are smooth, hairy when young.

Leaves: Leaves are membranaceous, lance-shaped but widest at the center with the ends equal, 1.5 to 15 × 1 to 8.5 cm, tapering to the tip, wedge-shaped base, smooth-edged at base but elsewhere coarsely toothed, hairy.

Flowers: inflorescences are simple or branched, 10 to 15 cm long. The calyx is 1.5 to 3 mm long at the time of pollen release, 3 to 4 mm long in fruit. The corolla is greenish white, 3 to 5 mm long.

Fruits/seeds: Nutlets are reddish brown, coarsely pitted, semilustrous, producing a small amount of mucilage in water.

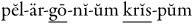

O. kilimandscharicum Baker ex Gürke in Engl., Pflanzews. Ost.-Afrikas 4 (C):349. 1895.

Native country: Camphor basil is native to Tanzania, Kenya, and Uganda, introduced into Sudan.

General habit: Camphor basil is a perennial, growing to a height of about 2 m, branching repeatedly, woody at the base.

Leaves: Leaves are 15 to 55 × 10 to 30 mm, toothed, hairy, light green or gray-green, blunt-tipped. The egg-shaped leaves often fold upward, exposing the lower surfaces.

Flowers: The inflorescences are simple, up to 30 cm long. The bracts are narrow, tapering to the tip, stalked, and persistent. The calyx is similar to that of O. canum but with a very hairy upper lobe, kidney-shaped, abruptly turned back. The corolla is white, pink, or mauve, five or more times longer than the calyx.

Fruits/seeds: Nutlets are black, lustrous, pitted, with a slight ridge, with moderate mucilage in water.

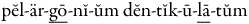

O. tenuiflorum L., Sp. pl. 597. 1753 (O. sanctum L.).

Native country: This species is native to India and Malaysia, where it is revered by the Hindus as an embodiment of Tulsi, consort to the god Vishnu, but it has become widely distributed in the Pacific Islands, Africa, and Latin America.

General habit: Holy basil is a much-branched perennial, 0.3 to 1 m tall, often woody at the base. Stems and branches are soft-hairy.

Leaves: Leaves are membranaceous, widest at the center with ends equal to parallel-sided, 15 to 33 × 11 to 20 mm, tapering to the tip or blunt, with a wedge-shaped base and smooth edges, margins elsewhere smooth or moderately toothed; hairy on both surfaces, especially on the nerves beneath; leaf stalk 7 to 15 mm long.

Flowers: Bracts egg-shaped, pinched at the tip, 2 to 3 mm long, beset with a marginal fringe of hairs. The calyx is 1 to 2.5 mm long at pollen release, about 3 to 3.5 mm long in fruit. Corolla is white or pink, 3.5 to 4 mm long.

Fruits/seeds: Nutlets are minute, brown, round-oval, more or less lustrous, finely pitted, producing small amounts of mucilage when wet.

water dropwort

Family: Apiaceae (Umbelliferae)

Growth form: hardy perennial to 16 inches (40 cm) tall

Hardiness: hardy to Zone 6

Light: full sun to part shade

Water: constantly moist

Soil: rich in organic matter

Propagation: easily rooted from off sets

Culinary use: celery substitute but limited (not GRAS)

Craft use: none

Landscape use: wildflower garden, cottage garden, or edge of pond

French: fenouil d’eau, ciguë aquatique

German: Wasserfenchel, Ross-Fenchel, Pferde-Kümmel, Wasser-Kümmel

Dutch: water-venkel, watertorkruid

Italian: fellandrio, finocchio acquatico

Spanish: felandrio acuático

Chinese: shuiqin, chin-tsai, shui-ying, chu-kuei

Japanese: seri

Vietnamese: rau c n

n

Hindi: ghora-ajowan

Malay: batjarongi, piopo, bamboong, pampoong

Oenanthe includes about thirty north temperate species normally found in aquatic situations. The generic name is derived from the Greek oinos, “wine,” and anthos, “flower,” or flowers with a wine-like odor.

Water dropwort is favored by many Southeast Asians as a salad herb or steamed with rice. The stalks and leaves of the plant taste and look like celery with a hint of carrot leaves, and the Japanese find this a winning combination with soups, salads, and sukiyaki.

The herb is native to pond margins, paddy fields, and wet places in China, Japan, Malaysia, India, and Australia. It is a perennial that spreads by stolons (thin, horizontal stems on the surface of the soil, just like mint). Water dropwort is far easier to grow than celery and can be potted to be maintained in the greenhouse or windowsill for winter harvests. Water dropwort prefers wet soil but will grow easily in moist garden loam and is winter hardy to at least Zone 6. Both green and red forms are known; both resemble a low celery. ‘Flamingo’ is a variegated cultivar in green, white, and pink. White flowers appear in early summer in an inverted umbrella-shaped inflorescence.

Water dropwort does not have GRAS status.

The oil of water dropwort is antifungal and antibacterial. Hepatic detoxification is enhanced by extracts of O. javanica, apparently due to the content of persicarin (3-potassium sulfate ester of isorhamnetin).

Important chemistry: The essential oil of the flowering tops of water dropwort contains 68 percent dill apiole and 14 percent beta-phellandrene.

O. javanica (Blume) DC., Prodr. 4:138. 1830 [O. stolonifera (Roxb.) Wall.].

Native country: Water dropwort is native to pond wetlands of China, Japan, Malaysia, India, and Australia.

General habit: Water dropwort is a smooth, stoloniferous perennial with erect stems to 20 to 40 cm tall.

Leaves: Leaves at 7 to 15 cm long, triangular or triangular-egg-shaped, once or twice compound, the ultimate segments egg-shaped or narrowly so, 1 to 3 cm × 7 to 15 mm, tapering to a point or almost pinched at the tip, irregularly toothed, sometimes deeply lobed.

Flowers: Flowers are white and in an umbel.

Fruits/seeds: The fruit is about 2.5 mm long with corky ribs.

marjoram

Family: Lamiaceae (Labiatae)

Growth form: herbaceous perennials 14 to 39 inches (35 to 100 cm) tall

Hardiness: many only hardy to southern California (Zone 9); wild marjoram and oregano hardy to at least Pennsylvania (Zone 6)

Light: full sun

Water: moist to somewhat dry; can with stand drought when established

Soil: well-drained gravelly or rocky loam, pH 4.9 to 8.7, average 6.9 (O. majorana); 4.5 to 8.7, average 6.7 (O. vulgare subsp. vulgare)

Propagation: seeds in spring, cuttings in summer; 160,000 seeds per ounce (5,644/g) (Origanum O. majorana); 130,000 (4,586/g) (O. vulgare subsp. vulgare)

Culinary use: many entree dishes of the Mediterranean region

Craft use: wreaths, dried flowers

Landscape use: excellent for edgings, borders, or pots

Origanum is derived from the Greek for “beautiful mountain,” a reference to the usual habitat and attractiveness of the marjorams even away from the mountains. Both the flowers and foliage are pleasing accents in the garden. The aromas of the species vary from the light, clean odor of sweet marjoram to the tarry, creosotelike scent of some oreganos native to Greece. All 43 species are perennials native to Eurasia that do well in full sun and very well-drained soil; they vary, however, in sensitivity to frost. Many species of this genus, particularly the ones designated as oregano, are particularly evocative of the Mediterranean and bring back memories of rocky hillsides covered with lovely, sweet scents and sparkling flowers, along with the regional cuisine.

sweet marjoram

French: marjolaine

German: Majoran

Dutch: marjolein

Italian: maggiorana

Spanish: mejorana, amáraco

Portuguese: manjerona

Swedish: mejram

Russian: mayoran

Chinese: ma-yueh-lan-hua

Japanese: mayorana

Arabic:

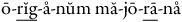

The clean, sweet odor of sweet marjoram is described by perfumers as warm-spice, aromaticcamphoraceous, and woody, reminiscent of nutmeg and cardamom. The small, gray-felty leaves and terminal heads of white flowers make this a delight in pots on the patio, as this is a tender perennial probably hardy only to Zone 9b. Thus, it must be carried over in the greenhouse or treated as an annual in most North American gardens. A form known in the trade as Origanum majorana

“Greek marjoram” or “compact Greek marjoram” is grayer, hardier, and a bit more compact in habit.

The specific epithet is derived from the Greek for marjoram. Sweet marjoram is widely used in beverages, meats, baked goods, and condiments; its leaves (1.9 to 9,946 ppm), essential oil (1 to 40 ppm), and oleoresin (37 to 75 ppm) are considered GRAS. The essential oil of sweet marjoram shows antimicrobial activity and is one of the few Origanum oils that can be used in perfumery, where it is used in fougères, colognes, and Oriental bases.

Origanum majorana

Egypt, France, and Canada are major sources of dried sweet marjoram imported into the United States. Sweet marjoram is usually grown from seeds, but in the spring greenhouse or under lights indoors, plants often succumb to root and stem diseases; cutting-grown plants are less vulnerable to these problems. A seeding density of 1 inch apart (40 plants/m) and 8 to 16 inches (20 to 40 cm) between rows is recommended for commercial production; home gardeners would probably prefer planting young plants 6 to 12 inches (15 to 30 cm) apart in rows. With harvests two to four times a year, yields of 4,015 pounds per acre (4,500 kg/ha) dried leaves and 7.8 gallons per acre (73 l/ha) essential oil can be expected. Convection drying at about 113°F (45°C) preserves the best flavor of marjoram. Blanching prior to drying preserves the green color but reduces the essential oil content.

Important chemistry: Sabinene hydrate and sabinene hydrate acetate, which supply the typical odor to marjoram, are particularly labile during distillation, and analysis of solvent extracts by researchers in Germany found that the primary components of sweet marjoram odor are 36.01±17.01 cis-sabinene hydrate acetate and 32.28±16.26 cis-sabinene hydrate. The essential oil of sweet marjoram consists of 16 to 52 percent terpinen-4-ol, 0 to 43 percent (Z)-sabinene hydrate, 3 to 14 percent alpha-terpineol, trace to 20 percent gamma-terpinene, trace to 12 percent sabinene, and 2 to 10 percent linalool. Selections from Turkey have been reported with 78 to 80 percent carvacrol, providing an odor of oregano. Cultivated material in Cuba has been reported with 18 percent terpinen-4-ol, 16 percent linalool, and 12 percent thymol; another report of cultivated material in Morocco showed 33 percent linalool and 22 percent terpinen-4-ol. These latter two reports may be actually O. ×majoricum from the essential-oil profile.

hardy sweet marjoram

Hardy sweet marjoram is a hybrid of sweet marjoram (O. majorana) with wild marjoram (O. vulgare) and commonly confused with both. Depending upon the variability of the parents, hardy sweet marjoram may vary from tiny-leaved to large-leaved, light green to gray, and from sweetly scented to musky scented. The most commonly available form of hardy sweet marjoram in North America may be used in the same manner as sweet marjoram and has the appearance of a pale green sweet marjoram. The alternate name, “Italian oregano,” does not describe the sweet marjoram-like odor, although it may be a better name for increased sales at nurseries.

Hardy sweet marjoram requires the same culture as sweet marjoram but can be overwintered successfully with sunny, well-drained soil in Zone 7. While hardy sweet marjoram is somewhat sterile, it may occasionally set seeds that germinate in sandy soil.

Important chemistry: The most commonly available form of hardy sweet marjoram in North America has an oil with 17 percent cis- sabinene hydrate and 15 percent terpinen-4-ol, which supply the sweet marjoram scent; 12 percent carvacrol gives a hint of oregano. Turkish selections of hardy sweet marjoram have 26 to 27 percent cis-sabinene hydrate, and 7 to 18 percent carvacrol. Forms cultivated in South America under the synonym O. ×applii have trace to 26 percent thymol, 17 to 20 percent linalyl acetate, and 10 to 13 percent terpinen-4-ol, providing a thyme/lavender-like odor.

Spartan oregano

Spartan oregano is commonly imported with other commercial dried oregano from Turkey. The specific epithet refers to the minute flowers. While it is commercially important and widely consumed, it has yet to enter cultivation in North America. This is probably a tender perennial requiring pot culture with the overall appearance of a fuzzy, lax pot marjoram. The oil is antimicrobial. Researchers in Turkey found that oil of Spartan oregano can be used as an antimicrobial in the leather industry.

Important chemistry: The essential oil contains 75 to 84 percent carvacrol.

pot marjoram

The specific epithet is derived from a kind of Greek oregano. This tasty oregano is especially esteemed in Turkey, where the common name, translated as “balls oregano,” alludes to the shape of the inflorescence but also has Freudian significance because of its macho taste. This oregano has come in and out of the herb trade in the United States over the last fifty years; in past herb books, it was often confused with selections of O. vulgare. This finicky plant’s tenderness and cultural requirements have limited its staying power.

We culled seeds of authentic pot marjoram from commercial oregano samples in the 1970s and released it to some herb nurseries. In the 1980s, the National Herb Garden, under the leadership of Holly Shimizu, released the correctly named plant again. The latter collection had been found by a member of the Herb Society of America in a meadow on a small island as the only plant that the sheep wouldn’t eat.

The leaves vary from mildly hairy, providing a pale green color, to densely hairy, providing a gray color. This is a tender perennial requiring pot culture. The soil should be well-drained, and the pot should be terra-cotta. Provide cool, near freezing temperatures over winter under full sun. When spring arrives and new growth starts, trim back the dead or rambling growth. Alternatively, save the seeds each year and grow anew. Watch out, though. If you grow other species of Origanum nearby, you will invariably harvest hybrid seed; if you crave something new, that may be okay, but it does not preserve the original germplasm.

The oil of pot marjoram is antifungal and antibacterial, as would be expected from its high phenol (carvacrol) content.

Important chemistry: The essential oil of O. onites contains 2 to 90 percent carvacrol, 1 to 31 percent gamma-terpinene, 0 to 14 percent 1,8-cineole, and 1 to 12 percent p-cymene.

Lebanese oregano

This is the ezov (“hyssop”) of the Bible (Exodus 12:21–22, I Kings 4:33, Psalms 51:7, John 19:28–30). Samaritans traditionally used bunches of O. syriacum to sprinkle the blood of the Passover sacrifice; the hairs on the stems were reputed to prevent the coagulation of the blood. Thus, the use of branches of ezov to present the vinegar-soaked sponge to Christ just prior to his death would have been particularly symbolic. The oil of O. syriacum is antimicrobial and antioxidant, as might be expected from the high phenol (carvacrol) content.

This is similar to pot marjoram in overall appearance but more robust and with larger leaves and about as variable in leaf color, from pale green to gray. Both thyme-scented and oregano-scented forms are known. Lebanese oregano, white oregano, Syrian hyssop, and Biblical hyssop are English names attached to this species, but the Arabs call this (and a spice mixture) za’atar.

Origanum syriacum is harvested along with other oregano species in Turkey. It is a tender perennial that has not entered extensive cultivation, but a hybrid of this with O. vulgare has entered the trade simply as O. maru, a taxonomic synonym of O. syriacum, incorrectly applied. The latter hybrid has large, dark green, oregano-scented leaves and is routinely hardy to Zone 7, unlike the parental species.

Important chemistry: Rarely has the essential oil literature stated the correct botanical identification of the oregano under consideration, and investigations of O. syriacum are no exception. The essential oil of Turkish O. syriacum (i.e., var. bevanii) consists of 43 to 64 percent carvacrol and 6 to 12 percent p-cymene, sometimes with up to 25 percent thymol. The essential oil of Israeli O. syriacum (i.e., var. syriacum) consists of 12 to 44 percent thymol, 16 to 40 percent carvacrol, 11 to 15 percent gammaterpinene, and 13 to 20 percent para-cymene. The essential oil of O. syriacum from the Holy Land (i.e., var. syriacum and bevanii) consists of 1 to 80 percent carvacrol and 1 to 71 percent thymol.

wild marjoram, oregano

The six subspecies of O. vulgare are greatly confused (see the botanical keys for further diagnostic characters). The subsp. vulgare (called wild marjoram in English, origan vulgaire or marjolaine sauvage in French, and Wilder Majoran in German) is the plant that bears pretty pink flowers and purple bracts, but it is useless as a condiment, even though it is often sold as “oregano.” The subspp. virens and viridulum, also called wild marjorams, are just as useless as condiments. The subsp. glandulosum (Algerian oregano) is not often encountered in the United States. Some forms of subsp. gracile (Russian oregano) bear the typical odor of Greek oregano. The subsp. hirtum is the Greek oregano, which is now principally imported from Turkey; the harsh, creosote-like odor makes it relatively easy for any gardener with a nose to identify.

Oregano is widely used in cooking, and the leaves (320 to 2,800 ppm) are considered GRAS. Oregano essential oil is fungistatic and bacteriostatic and active against trypanosomes. The essential oil and alcoholic extract of the leaves are antioxidant. Galangin and quercetin, two flavonoids in oregano, were demonstrated to be antimutagenic in vitro against a common dietary carcinogen, Trp-P-2 (3-amino-1-methyl-5H-pyrido[4,3-b]indole). Aristolochia acid I, aristolochic acid II, and D-(+)-raffinose from O. vulgare were found to inhibit thrombin activity and to be anticarcinogenic. Leaves of O. vulgare subsp. hirtum were found by Greek researchers to be a natural herbal growth promoter for early maturing turkeys; they can also be useful to treat diarrhea in calves. Oregano oil may also be used as disinfectant for eggs.

All subspecies of O. vulgare require well-drained loam in full sun. With plants about 6 inches (16 cm) apart and rows 16 inches (40 cm) apart, yields of dried herb can achieve 2,320 to 5,424 pounds per acre (2,600 to 6,080 kg/ha) the first year and 901 to 14,944 pounds per acre (1,010 to 16,750 kg/ha) the second year. Oregano is particularly subject to sudden wilts caused by Fusarium oxysporum and F. solani.

Several cultivars of subsp. vulgare are grown. ‘Aureum’ is a very vigorous and yellow-green version. ‘Dr. Ietswaart’ has golden-yellow, almost translucent leaves that are wrinkled and circular. Both cultivars have been sold as ‘Aureum’, and the former has also been sold as ‘ Golden Creeping’. Both sometimes show irregular streaks of green and tend to become totally green late in the season or in hot weather. ‘Thumble’s Variety’ is a more compact selection of ‘Aureum’. ‘Jim Best’ (not ‘Jim’s Best’) is streaked with gold and green and quite vigorous. ‘White Anniversary’ is edged in white but not reliably hardy and prone to leaf-fungus diseases in humid climates. ‘Humile’ (‘Compactum’) is a dwarf selection of wild marjoram. Other forms of O. vulgare with varying degrees of purple bracts are sold as ‘Bury Hill’ or O. pulchellum.

Origanum vulgare subsp. vulgare

Important chemistry: The chemical literature rarely specifies the taxon beyond O. vulgare or “oregano.” The essential oil of O. vulgare subsp. vulgare usually contains trace to 39 percent thymol, trace to 31 percent terpinen-4-ol, trace to 28 percent linalool, trace to 26 percent sabinene, trace to 19 percent p-cymene, trace to 19 percent beta-caryophyllene, 0 to 17 percent (Z)-beta-ocimene, 0 to 29 percent germacrene D, trace to 14 percent beta-cubenene, trace to 11 percent gamma-terpinene, trace to 11 percent 1,8-cineole, and trace to 10 percent sabinene, providing a slight musty odor; Turkish plants have been reported with 21 percent terpinen-4-ol and beta-caryophyllene and 18 percent germacrene D, providing a musty carnation-like odor. The essential oil of O. vulgare subsp. glandulosum cultivated in Italy consists of 79 to 84 percent carvacrol. The essential oil of O. vulgare subsp. gracile contains 15 to 79 percent thymol, trace to 17 percent gamma-terpinene, trace to 14 percent sabinene, and 10 percent carvacrol, providing a pine-tar odor; Turkish plants have been reported with 18 percent beta-caryophyllene and 13 percent germacrene D, providing a musty carnation-like odor. The essential oil of O. vulgare subsp. hirtum contains trace to 81 percent carvacrol, trace to 65 percent thymol, 2 to 26 percent gamma-terpinene, and 3 to 25 percent p-cymene; the odor of this leading source of oregano has a sharp, tarry, creosotelike odor. The essential oil of O. vulgare subsp. virens contains 10 to 70 percent linalool, trace to 19 percent beta-caryophyllene, 0 to 13 percent (E)-beta-ocimene, trace to 10 percent gamma-terpinene, and 0 to 10 percent (Z)-ocimene, providing a musty lavender-basil odor. The essential oil of O. vulgare subsp. viridulum from Iran consists of 20 percent linalyl acetate and 13 percent sabinene, providing a lavender-pine odor. Essential oil of O. vulgare subsp. viridulum from the Liguria region of northern Italy have trace to 63 percent carvacrol, trace to 48 percent thymol, trace to 43 percent linalo, trace to 22 percent caryophyllene oxide, and trace to 16 percent germacrene-D-4-ol.

The calyces, which are under genetic control, are particularly important as an aid in identification.

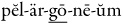

Key:

1. Lower lip of calyces nearly absent, or the upper lip comprises 9/10 or more of the length of the calyx and appears bract-like; calyx upper lip toothless to almost toothless....................................... 2

2. Spikes arranged in flat-topped or convex open inflorescence; leaves often with small sharp teeth................................................................................................. O. onites

2a. Spikes arranged in panicles; leaves usually entire................................................... 3

3. Stems and leaves beset with minute hairs (hairs about 0.3 mm long); leaf apices blunt, veins not raised on lower surface.............................................................. O. majorana

3a. Stems and leaves with moderate coarse and stiff hairs or with dense, wool-like covering of matted, intertangled hairs (hairs about 1 mm long); leaf apices usually tapered, and veins usually raised on lower surface........................................................................ O. syriacum

1a. Lower lip of calyx obviously present, so that calyces are one- or two-lipped for one-fifth to one-half their length and tube- or funnel-shaped; calyx upper lip often with three teeth or lobes, and lower lip consisting of two teeth or lobes....................................................................... 4

4. Calyces about 2 mm long..................................................... O. minutiflorum

4a. Calyces about 2.5 to 4.5 mm long........................................................... 5

5. Bracts about 4 mm long, 3 mm wide, inconspicuously dotted with glands; calyces funnel-shaped, about 3.5 mm long, teeth of lower lip much shorter to about as long as the upper lip................................................................... O. ×majoricum

5a. Bracts 2 to 11 mm long, 1 to 7 mm wide, conspicuously punctate; calyces tube-bell shaped, 2.5 to 4.5 mm long, with 5 (sub)equal teeth...................................... O. vulgare

O. majorana L., Sp. pl. 590. 1753. (Majorana hortensis Moench).

Native country: O. majorana is native to dry, rocky (limestone) places on Cyprus and the adjacent part of southern Turkey but occurs spontaneously in the former Yugoslavia, Italy, Corsica, southern Spain, Portugal, Morocco, and Algeria. It also is often found as a garden escape.

General habit: Stems are usually erect or ascending, sometimes branched at the bases, up to 80 cm long.

Leaves: Leaves are more or less stalked, roundish or egg-shaped or oval, apex usually blunt, 3 to 35 mm long, 2 to 30 mm wide, whitish or grayish, and coated with a dense wool-like covering of minute hairs; sessile glands inconspicuous.

Flowers: The inflorescence is a spike, usually three to five set closely together on a branch, slightly globe-shaped, egg-shaped, or a four-sided cylinder, 3 to 20 mm long, about 3 mm wide. Bracts are two to thirty pairs per spike, oval, egg-shaped attached at the narrow end, or diamond-shaped, apices usually blunt and smooth. Calyces are one-lipped, rather diamond-shaped, 2 to 3.5 mm long, outside more or less coated with dense wool-like covering of minute hairs; upper lips usually toothless, sometimes with small teeth. Corollas are two-lipped for about 3 to 7 mm long; white; outside coated with short, soft, straight hairs; upper lips divided into two lobes; lower lips divided into three subequal lobes.

O. ×majoricum Cambess., Mem. Mus. Paris 14:296. 1827 [incl. O. ×applii (Domin) Boros].

Native country: O. ×majoricum is probably a hybrid, O. vulgare ×O. majorana; it has inherited the hardiness of the former and the odor of the latter. It occurs naturally in Spain and Portugal but is widely cultivated.

General habit: Stems are up to 60 cm long, coated with a dense woolly covering of minute hairs (hairs about 0.5 mm long).

Leaves: Leaves are stalked, about 9 × 5 mm.

Flowers: Spikes are usually cylindrical, up to 2 cm long, about 5 mm wide, not nodding. The green bracts are about 4 mm by 3 mm. Calyces are more or less funnel-shaped, about 3.5 mm long; upper lips with somewhat triangular teeth, less than 0.4 mm long, for one-third to one-half their length. Lower lips may be much shorter up to nearly as long as the upper lips, sometimes almost toothless but usually consisting of triangular teeth, which are less than 0.7 mm long. The throats are coated with short, soft, straight hairs. Corollas are two-lipped for about one-third their length, 2.5 to 6 mm long and white.

O. minutiflorum Schwarz & Davis, Kew Bull. 1949:408. 1949.

Native country: O. minutiflorum is native to a few places in southern Turkey, where it grows on limestone at an altitude of about 1600 m.

General habit: This herb is a subshrub with erect stems up to 35 cm long, light brown, with curved and appressed hairs.

Leaves: Short-stalked green leaves occur in up to eighteen pairs per stem; they are egg-shaped or oval with tops more or less tapering to the apex or blunt at the apex and 3 to 16 mm long and 5 to 12 mm wide. They are coated with short, soft, straight hairs; sessile glands up to 150 per square cm.

Flowers: Flowering spikes are almost globe-shaped to cylindrical, sometimes rather loose at the bases, and measuring 2 to 8 mm long and about 3 mm wide. Egg-shaped to oval green bracts occur three to six pairs per spike and measure 1 to 3 mm long and 0.5 to 1.5 mm wide. The outside is coated with short, soft, straight hairs.

Calyces are two-lipped for about one-fifth their length, about 2 mm long and the outside is coated with short, soft, straight hairs. The upper lips are divided for about two-fifths their length into three almost equal and nearly triangluar teeth. The white corollas are two-lipped for about two-fifths, 2 to 4 mm long; upper lips are divided for about one-fifth into two lobes.

O. onites L., Sp. pl. 590. 1753.

Native country: O. onites is native from southern Greece to southern Turkey and is widely cultivated.

General habit: This herb is a subshrub with erect or ascending stems up to 1 m long, light brown, with moderately coarse and stiff hairs.

Leaves: Leaves occur in up to twenty-eight pairs per stem, the lower ones shortly stalked, heart-shaped, egg-shaped, or oval, more or less tapering to the apex or pinched at the tip, margins often with small teeth, 3 to 12 mm long and 2 to 9 mm wide, coated with moderately coarse and stiff hairs and with long, soft straight hairs with glands.

Flowers: Spikes are arranged in a flat-topped or convex open inflorescence, almost globe-shaped, ovoid, or four-sided cylindrical, 3 to 17 mm long and about 4 mm wide. Bracts are four to thirty-four pairs per spike; oval, egg-shaped, or egg-shaped and attached at the narrow end; toothless; 2 to 5 mm long, 1.5 to 4 mm wide; light green, outside hairy. Calyces are one-lipped for about nine-tenths; somewhat rhomboid, egg-shaped or egg-shaped and attached at the narrow end; 2 to 3 mm long; outside somewhat coated with short, soft, straight hairs. Corollas are twolipped for about two-fifths; 3 to 7 mm long; white; outside somewhat coated with short, soft, straight hairs; upper lips divided for one-tenth to one-fifth their length into two lobes.

O. syriacum L., Sp. pl. 590. 1753.

Key:

1. Stems with dense wool-like covering of matted, tangled hairs of medium length; leaves whitish............................................................................. O. syriacum var. syriacum (O. maru L.).

1a. Stems with moderate coarse and stiff hairs; leaves with a slight wool-like covering of matted, intertangled hairs of medium length, leaves greenish................................................. 2

2. Leaves about 14 by 11 mm, heart-shaped, or egg-shaped, shortly stalked (stalks about 2 mm long); corollas about 4 mm long.................................................................................................... O. syriacum var. sinaicum (Boiss.) Ietswaart, Tax. Rev. Gen. Origanum 89. 1980.

2a. Leaves about 25 by 15 mm, egg-shaped or oval, long stalked (stalks about 5 mm long); corollas about 6 mm long............. O. syriacum var. bevanii (Holmes) Ietswaart, Tax. Rev. Gen. Origanum 88. 1980.

Native country: Both O. syriacum var. syria-cum (native to Israel, Jordan, and Syria) and O. syriacum var. bevanii (native to Turkey, Cyprus, Syria, and Lebanon) are harvested as white oregano and are sometimes sold in the United States as Lebanese oregano. Origanum syriacum var. sinaicum is found only in the Sinai Peninsula but also has been used as oregano.

General habit: O. syriacum is a subshrub with ascending or erect stems, 0.4 to 13 cm long.

Leaves: Leaves are up to thirty pairs per stem; clearly stalked (petiolate) to almost stalkless; egg-shaped, oval, or heart-shaped; blunt to pinched at the tip; margins toothless or remotely with small rounded teeth; 3 to 35 mm long; 2 to 23 mm wide; green or whitish; with slightly moderately coarse, matted, stiff hairs to covered with dense wool-like covering of matted, tangled hairs of medium length.

Flowers: Spikes are four-sided cylindrical to almost globe-shaped, 3 to 25 mm long, about 4 mm wide. Bracts are four to forty pairs per spike, egg-shaped and attached at the narrow end or oval, blunt or tapering to the apex, toothless or slightly small-toothed, 2 to 5 mm long, about 2 mm wide, green or whitish, outside coated with moderately coarse, matted, stiff hairs. Calyces are one-lipped for nine-tenths or more, egg-shaped and attached at the narrow end or oval, about 2 mm long, outside coated with moderately coarse, matted, stiff hairs. Corollas are two-lipped for about 4 to 7.5 mm long, white, outside more or less coated with short, soft, straight hairs; upper lips divided for about one-fifth into two lobes, lower lips divided for about four-fifths into three sub-equal lobes.

O. vulgare L., Sp. pl. 590. 1753.

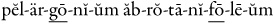

Key:

1. Leaves and calyces usually with conspicuous translucent dots; bracts 1.5 to 6 by 1 to 3 mm............. 2

2. Stems slightly coated with short, soft, straight hairs or becoming hairless with age; leaves with translucent dots, more or less coated with a bluish wax, almost smooth, or slightly coated with short, soft, straight hairs; branches and spikes often slender.................................. subsp. gracile

2a. Stems usually with moderate coarse and stiff hairs; leaves densely coated with translucent dots, usually not glaucous, usually hirsute or pilosellous; branches and spikes not slender................ 3

3. Bracts usually shorter than calyces, hairless, or slightly coated with short, straight hairs along margins; obviously coated with translucent dots; inflorescences often very wide................................................................................................ subsp. glandulosum

3a. Bracts usually as long as or somewhat longer than calyces, with moderately coarse and stiff hairs or coated with short, soft, straight hairs, more or less coated with translucent dots; inflorescence often compact..................................................................... subsp. hirtum

1a. Leaves and calyces usually conspicuously coated with translucent dots; bracts 2 to 11 by 1 to 7 mm.... 4

4. Bracts usually (partly) purple; flowers pink.......................................subsp. vulgare

4a. Bracts usually (yellowish) green; flowers usually white....................................... 5

5. Bracts 3.5 to 11 by 2 to 7 mm, smooth or almost smooth, yellowish green; inflorescences often compact................................................................ subsp. virens

5a. Bracts 2 to 8 by 1 to 4 mm, often (densely) coated with short, soft, straight hairs, usually green; inflorescences usually not compact................................ subsp. viridulum

subsp. vulgare

subsp. glandulosum (Desf.) Ietswaart, Tax. Rev. Origanum. 110. 1980. subsp. gracile (Koch) Ietswaart, Tax. Rev. Origanum. 111. 1980 (O. tyttanthum Gontshcarov, O. kopetdagnehse Boriss.).

subsp. hirtum (Link) Ietswaart, Tax. Rev. Origanum. 112. 1980 (O. hirtum Link, O. heracleoticum auct., non L.)

subsp. virens (Hoffmanns. & Link) Ietswaart, Tax. Rev. Origanum 115:1980 (O. virens Hoffmanns. & Link).

subsp. viridulum (Martrin-Donos) Nyman, Consp. Fl. Eur. 592. 1881 [O. vulgare L. subsp. viride (Boiss.) Hayek].

Native country: O. vulgare is native to Europe, western Asia, and northern Africa, but it has become widely naturalized around the world.

General habit: O. vulgare is a woody perennial with stems 10 to 100 cm long, usually ascending and rooting at the bases.

Leaves: Leaves are up to forty-five pairs per stem; stalked to almost stalkless; egg-shaped, oval, or roundish; tapering to the apex to blunt; 6 to 40 mm long; 5 to 30 mm wide; with moderately coarse and stiff hairs or with long, soft, straight hairs to hairless, sometimes covered with a bluish waxy covering; stalkless glands hardly visible to very conspicuous; margins smooth or remotely small-toothed.

Flowers: Spikes are 3 to 35 mm long, 2 to 8 mm wide. Bracts are two to twenty-five pairs per spike; egg-shaped and attached at the narrow end to egg-shaped or oval; more or less tapering to the apex or pinched; 2 to 11 mm long; 1 to 7 mm wide; coated with fine hairs; densely coated with short, soft, straight hairs or hairless; (partly) purple, green, or yellowish green, sometimes glaucous. Flowers almost stalkless. Calyces are 2.5 to 4.5 mm long, outside coated with fine hairs, coated with short, soft, straight hairs, or smooth. Corollas are 3 to 11 mm long, purple, pink, or white; outside coated with short, soft, straight hairs; upper lips divided for about one-fifth into two long lobes; lower lips divided for about one-fifth into three somewhat unequal lobes.

poppy seed

Family: Papaveraceae

Growth form: annual to 39 inches (100 cm) tall

Culinary use: primarily breads, crackers, and pastries

Craft use: pods useful in wreaths and dried flower arrangements

French: pavot somnifère

German: Schlafmohn, Garten-Mohn

Dutch: slaapbol, papaver, maankop

Italian: papavero da oppio

Spanish: adormidera

Portuguese: dormideira, papoila dol ópio

Swedish: opiumvallmo

Russian: mak

Chinese: ying-tzu-shu

Japanese: keshi

Arabic: khas-khasa

This poppy yields opium, yet remains the only source of edible poppy seed and poppy seed oil. The seed oil is considered GRAS. Today most poppy seed is imported from the Netherlands and Australia; the slate-blue Dutch poppy seed is standard. Because of the potential abuse of the opium-yielding sap of this plant, cultivation in the United States has been prohibited by both federal and state governments since the early twentieth century. Opium poppies were once widely cultivated for their beautiful blossoms, and sometimes they persist at old cottage gardens. We do not advocate growing your own poppy seed, and we have omitted directions on cultivation.

The genus Papaver includes about fifty species native to Europe, Asia, South Africa, Australia, and western North America. All are characterized by dried fruit that resembles a small “shaker”; these are used in dried flower arrangements. Papaver was the Latin name for poppies, while somniferum means “sleep-inducing.”

The opium poppy has been cultivated since ancient times. A statue of a poppy goddess was found at a sanctuary at Gazi, west of Heraklion, Crete, dating to about 1400 B.C.E. To harvest the raw material for opium, the immature seed capsules are lanced, usually with a three-pronged knife, early in the morning. The milky latex slowly exudes and congeals to a black mass. In the evening, this blackened latex is gathered and eventually pressed into bricks. The resulting raw opium contains up to twenty-five different alkaloids, especially morphine, which is a powerful analgesic and narcotic and a source of heroin. Tincture of opium, a deep ruby-red liquid called laudanum, was once widely used to alleviate pain but was also consumed as an addictive recreational drug by poets, painters, and novelists of eighteenth-and nineteenth-century Europe.

We used to be told that the black (or white) seeds (maw) do not contain measurable amounts of alkaloids unless they had been contaminated by the latex, but tests have shown commercial poppy seed to contain 0 to 1.7 ppm surface and free morphine and 0 to 0.5 ppm surface and free codeine as well as 0.6 to 2.3 ppm bound morphine and 0 to 0.5 ppm bound codeine. Perhaps those hot poppy seed milkshakes that are sometimes given to German and Eastern European children to soothe them into slumber have a real effect!

Papaver somniferum

The dried poppy capsules also have trace quantities of bound morphine and codeine, and commercial seed will germinate to produce poppies that yield opium.

Poppy seeds are widely used in baking for their distinctive nutty flavor and also as birdseed. Toasting or baking the seeds will enhance the nutty flavor. The whole seeds are commonly used on dinner rolls, while the crushed seeds, mixed with sugar and other ingredients, are used in pastries. The pressed oil is used in artists’ paints, salad oil, soap, and so on.

Opium poppy is a robust annual to about 3 feet (0.9 m) tall and coated with a blue wax. The flowers vary from white to mauve and from single with a distinct cross at the base (‘Danebrog’, or Danish flag poppies) to doubles with deeply slashed petals (“peony-flowered”).

Important chemistry: The latex is rich in alkaloids, principally morphine (1 to 21 percent), and also thebaine, codeine, narceine, narcotine, and papaverine. The seeds contain about 22 percent protein and 48 percent oil, the latter rich in palmitic (31 percent), oleic (27 percent), linoleic (18 percent), and lauric (13 percent) acids.

Papaver somniferum includes three subspecies, but subsp. somniferum is most widely cultivated.

P. somniferum L., Sp. pl. 508. 1753.

Native country: Opium poppy was probably derived from P. setigerum DC. of southwest Asia.

General habit: Opium poppy is a smooth annual coated with blue wax and growing 30 to 100 cm tall.

Leaves: Leaves are 7 to 12 cm long, ovate- oblong, with lobes arranged as in a feather.

Flowers: Flowers are white to mauve with almost round petals 35 to 45 mm across.

Fruits/seeds: The dried shaker-type capsule is 5 to 9 by 3 to 6 cm, yielding white to black seeds.

scented geranium

Family: Geraniaceae

Growth form: succulent perennial shrubs from 1 foot (30 cm) to 6 feet (1.8 m) tall

Hardiness: routinely hardy to Zone 9, although well-mulched plants snugged next to the house may be root-hardy to Zone 6

Light: full sun

Water: moist but not constantly wet; many can with stand drought

Soil: well-drained garden loam

Propagation: mostly cuttings during active growth in summer

Culinary use: limited (most not GRAS except for P. ‘Graveolens’)

Craft use: potpourri, wreaths, perfume

Landscape use: excellent for summer bedding as edgings or in borders; also excellent in pots or window boxes

Name a delectable fragrance—rose, lemon, orange, lime, strawberry, peppermint, camphor, nutmeg, spice, apple, apricot, coconut, filbert, ginger—and there’s a scented geranium to match. Pelargonium is derived from the Greek pelargos, or stork, referring to the ripe seed head, which supposedly resembles the head and beak of the stork, hence a common name of storksbill. Most of the 280 species are native to South Africa. Many additional, complex hybrids have been created since their introduction into Europe in the early seventeenth century.

While commonly called “scented geraniums,” they are often confused by the novice gardener with the hardy Geranium species, or cranesbills, and the hardy Erodium species, or heronsbills. In 1753, Linnaeus published thirty-nine species of the genus Geranium in his Species Plantarum, including storksbills, cranes-bills, and heronsbills in the same genus. From 1787 to 1788 L’Héritier published forty-four plates under the title Geraniologia. L’Héritier’s accompanying text was not published until 1802, but the unfinished manuscript was widely circulated prior to publication. From this manuscript, Aiton published the new names of Pelargonium and Erodium, separating these new genera from Geranium, in his Hortus Kewensis of 1789.

Both Pelargonium and Geranium have five petals and ten stamens, but in Pelargonium the two upper petals are usually larger and only five to seven anthers are fertile. The remaining are present as filaments. All three genera can also be distinguished by their fruits.

All scented geraniums do best in full sun in circumneutral garden loam with relatively cool, dry summers. The addition of 53 to 71 pounds per acre (60 to 80 kg/ha) of nitrogen is recommended for commercial production of rose geranium oil. Geranium for oil is harvested about four months after planting.

Sudden wilts and root rots from Pythium, Verticillium, Lasiodiplodia, and Fusarium, soil-borne fungi, are often encountered. Overhead watering, excessive soil moisture, and crowding will increase the incidence from wilt. Leaf spot (Cercospora spp.), gray mold or botrytis blight (Botrytis cinerea), black root rot (Thielaviopsis basicola and Macrophomina phaseolina), scab (Sphaceloma pelargonii), bacterial fasciation (Corynebacterium fascians), vascular wilts (Xanthomonas pelargonii), rust (Puccinia spp.), and several virus diseases have also been reported. Root-knot nematodes, Meloidogyne hapla and M. incognita, have been found to infect the roots of commercial stands of the rose-scented geranium. Spider mites, whiteflies, caterpillars, and aphids can be pests in the greenhouse.

Most scented geraniums flower best in late winter to early spring after a cool, but not freezing, winter. Because most species are not hardy below freezing, they are best raised as potted plants, and cuttings may be easily rooted in late summer to carry over through the winter.

Propagation by cuttings is important to preserve the unique characteristics of individual cultivars, which are often complex hybrids. While many geranium cultivars root easily and quickly in water, this is not normally recommended (see chapter 7, on propagation, for details). More traditional rooting methods use vigorous basal side-shoots ripped off in a downward tug that produces a “heel” cutting for best results. Some gardeners claim that cuttings root most easily after “hardening” (drying) a few hours, but this is not normally required for the scenteds. Some, such as strawberry-scented geranium and ‘Mabel Grey’, sometimes refuse to root at all unless basal cuttings or extra watering is used.

Scented geraniums have a reputation as being more difficult to root than other geraniums; one reason for this may be because of a number of viruses that sap the plants’ strength but do little else. The zonal geranium bedding-plant industry combats this by using seeds and by creating virus-free clones with special technology. These methods are expensive and are not used for scenteds because of technical difficulties and low sales when compared with bedding geraniums.

Name a delectable fragrance—rose, lemon, orange,

lime, strawberry, peppermint, camphor, nutmeg,

spice, apple, apricot, coconut, filbert, ginger—

and there’s a scented geranium to match.

An area of further research on rooting of scented geraniums is the use of Florel (ethephon). In a study, it increased rooting under supplemental lights, increased total roots per cutting, and reduced the stem length and stem diameter. Studies on basal heating are also needed.

Most of the offerings in the nursery trade, even of supposedly “pure” species, are actually complex hybrids. The herb industry, in general, has been plagued for decades with the practice of renaming plants; sometimes this is done intentionally to increase sales, but usually it is without malice by the uninformed. Scented geraniums are a case in point, and it sometimes appears that total name-anarchy exists. ‘Beauty Oak’ has been renamed ‘Beauty’, ‘Cody’ has been renamed ‘Apple Cider’, ‘Logee’ has become ‘Old Spice’, and ‘Logee’s Snowflake’ is now sold as ‘Snowflake’. The new names may have more appeal and induce more sales, but ‘Beauty’, for example, already designates another geranium, and the trade now has two clones called ‘Citronella’: one in cultivation in the United States and France and another in England. Which is correct?

In the following discussion we have omitted the mildly scented selections grown primarily for their flowers or foliage, such as P. vitifolium (L.) L’Hér. ex Aiton, ‘Brilliant’, ‘Capri’, ‘Clorinda’ (‘Eucalyptus’), ‘Mexican Sage’, ‘Mrs. Kingsley’, ‘Mrs. Taylor’, ‘Old Scarlet Unique’, ‘Pink Champagne’, ‘Red-Flowered Rose’, ‘Roger’s Delight’, ‘Rollison’s Unique’, ‘Solfrino’, ‘Spanish Lavender’, and ‘Sweet Miriam’. Some scented-leaved geraniums, such as the so-called labdanum-scented P. cucullatum (L.) L’Hér. ex Aiton and the apocryphal rue-scented P. ×rutaceum Sweet, are not in general cultivation and have also been omitted. New cultivars are introduced every year, and the correct taxonomic placement of these cultivars is often in doubt. We thus find too little published information on ‘Cook’s Lemon Rose’, ‘Copthorne’, ‘Dean’s Delight’, ‘Karooense’, ‘Lillian Pottinger’, ‘Ruby Edged Oak’, ‘Sancho Panza’, ‘Sharp-Toothed Oak’, ‘Solferino’, ‘Spring Park’, ‘Sweet Miriam’, ‘Variegated Oak’, or ‘Variegated Shrubland Rose’.

The scented geraniums have been grouped here by species. Following the principal species and their derivatives are the complex hybrids in which no one species predominates. In all cases, because of their rampant hybridization in years past and close similarities, only markedly distinguishing morphological characteristics are listed; detailed botanical descriptions are listed separately for the intellectually curious. These herbs were selected primarily for their odors, and thus are discussed more fully in the general introduction. Ultimately, identification of unknown scented geraniums must be done one-on-one with authentically labeled living material; not even good photographs will suffice in difficult cases.

A strong caveat must also be inserted here. Hybrid origins are only hypothetical unless artificial resynthesis has been done and compared with the type specimens (in addition to the descriptions and illustrations), and this has only been done (so far, in part) with the ‘Graveolens’ series. Much work remains to be done! Take any statements of hybrid origin in Pelargonium with a liberal dose of skepticism. They are only included here, with legitimately published names as currently accepted by taxonomists, to provide routes for future research. We have also followed the policy of the English experts in Pelargonium to create cultivar groups, e.g., ‘Graveolens’ (which see), for many of the so-called species complexes. Until nothospecies (hybrid species) are typified and the origins elucidated by resynthesis, this is probably the best temporary solution. This is obviously not the last word, and names will undoubtedly change in the future. Consider yourself warned!

southernwood geranium

The fragrant, gray, slender leaves of this species resemble the herb southernwood (Artemisia abrotanum). The floating, lacy, gray leaves are a great accent with other geraniums and in window boxes.

Pelargonium abrotanifolium

rose-scented geranium

The specific name means “head-shaped,” referring to the shape of the flower clusters. The flowers are similar to P. vitifolium, the grape-leaved geranium. This rose-scented geranium is one of the ancestors, along with P. radens and P. graveolens, of ‘Graveolens’, the leading rose-scented geranium of commercial cultivation. The hydrophilic extract of P. capitatum has been shown to be antimicrobial.

Important chemistry: The essential oil is very variable with trace to 48 percent alpha-pinene, 0 to 37 percent citronellyl formate, trace to 29 percent citronellol, 0 to 26 percent 10-epi-gamma-eudesmol, 0 to 22 percent delta-cadinene, 0 to 18 percent menthone, 0 to 18 percent germacrene D, 0 to 18 percent beta-caryophyllene, 0 to 18 percent guaia-6,9-diene, 0 to 15 percent geraniol, 0 to 4 percent linalool, 0 to 12 percent terpinen-4-ol, and 0 to 11 percent limonene.

Some cultivars derived from P. capitatum follow. Many of these may, in fact, be more correctly relegated to P. ‘Graveolens’ because of their lack of pollen fertility, but chromosome counts must still be done to confirm this classification.

Cultivar: ‘Attar of Roses’

Synonyms: ‘Otto of Roses’; more than one clone is sold in North America

Origin: England, 1817; introduced at the New York Botanical Garden in 1923

Description: differs from P. capitatum in that the stems are somewhat shorter, leaves are more densely lobed and harsher on the upper surfaces, small flowers on short stems are rose-pink, and the upper ones more conspicuously veined

Essential oil: 7 to 43 percent geraniol, 18 to 43 percent citronellol, and 3 to 14 percent isomenthone (minty rose)

Synonyms: ‘Ice Crystal Rose’, a seedling introduced by Gary Scheidt of California in the 1970s, is extremely similar but not identical

Origin: bred by Edward Alfred Bernard (“Ted”) Both, Flinders, South Australia, 1950s

Description: deeply divided leaves with irregular splashes of cream and white; flowers are small and lavender; fragrance is lemon-rose

Cultivar: ‘Major’

Synonyms: ‘Large-leaved Rose’, P. quinquevulnerum Willd.

Origin: Veitch, England, 1879, probably of hybrid origin

Description: same habit as P. capitatum but grows taller; leaves are larger, margins not as sharply toothed; flowers are similar in form but rose-pink in color

This was first described in 1983. According to the discoverer, Dr. J. J. A. van der Walt, this species may be a naturally occurring, ancient hybrid involving P. scabrum (L.) L’Hér. ex Aiton. It flowers most abundantly in spring. ‘Mabel Grey’ is a selected, cultivated clone of the species with leaves slightly less deeply lobed (much as ‘Mitcham’ is a selected, cultivated clone of peppermint).

Important chemistry: The oil of the wild species has 36 to 48 percent geranial and 27 to 37 percent neral, providing a lemony odor. ‘Mabel Grey’ is bitter lemon-scented with an essential oil containing trace to 58 percent neral, 30 to 43 percent geranial, 0 to 27 percent geranyl formate, 0 to 31 percent citronellol, 0 to 43 percent geraniol, and 0 to 13 percent beta-pinene.

Pelargonium citronellum ‘Mabel Grey’

lemon-scented geranium

The specific name refers to the crisped leaves, scented of lemons.

Important chemistry: 8 to 30 percent geranial, 3 to 57 percent neral, 0 to 14 percent nerol, trace to 17 percent [E]-nerolidol, 0 to 14 percent germacrene D, 0 to 14 percent selina-4,11-diene, trace to 11 percent beta-bourbonene, and 0 to 10 percent guaia-6,9-diene.

Some cultivars derived from P. crispum follow.

Synonyms: ‘Peach’, ‘Peach Cream’, ‘Variegatum’, often incorrectly listed as P. grossularioides

Description: similar to the species but with leaves mottled green and white, growth bushy, compact

Cultivar: ‘Prince Rupert’

Description: similar to the species but with larger leaves and shorter leaf stalks; flowers are the same color, the upper petals carmine-veined

Essential oil: 16 to 20 percent [Z]-nerolidol, 12 to 30 percent geranial, and 16 to 19 percent neral

Cultivar: ‘Variegated Prince Rupert’

Synonyms: ‘French Lace’

Origin: Arndt, New Jersey, 1948

Description: habit of P. cripsum but bushier and of more rapid growth, pyramidal in shape, leaves green with white margins

Essential oil: 28 to 49 percent geranial and 22 to 33 percent citronellol

Pelargonium crispum

pine-scented geranium

This pungent-scented geranium has flat, sticky, leaves and rounded teeth on the leaf margins. Most of the material cultivated in the United States as this species is actually an unnamed cultivar, perhaps derived from P. radens × P. denticulatum. Plants tend to become lanky with age and should be pruned back occasionally to maintain an attractive shape.

Important chemistry: 40 percent isomenthone, 18 percent citronellal, and 18 percent citronellol (pungent-scented).

A cultivar derived from P. denticulatum follows.

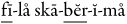

Cultivar: ‘Filicifolium’

Synonyms: ‘Fernaefolium’, P. filicifolium Hort.

Origin: introduced by Henderson in England in 1879

Description: very similar to the wild species in South Africa with finely cut leaves, lacy in appearance

Essential oil: 24 to 32 percent n-hexyl butyrate and 14 to 17 percent trans-2-hexenyl butyrate in the essential oil

This species is called “upright coconut” in the trade, not to be confused with P. tabulare (Burm.f.) L’Hér. or P. patulum Jacq.

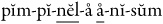

nutmeg-scented geranium

This aromatic (“nutmeg-scented”) geranium may be a hybrid, P. exstipulatum (Cav.) L’Hér. ex Aiton × P. odoratissimum; others have questioned whether this is a non-hybrid species, now extinct in South Africa.

Important chemistry: 10 to 31 percent methyl eugenol, 0 to 20 percent alpha-pinene, and 8 to 14 percent fenchone (spicy)

This species (notho- or otherwise) includes the following cultivars. Also listed are ‘Aroma’, ‘Fringed Apple’, ‘Fruity’, and ‘Lillian Pottinger’. ‘Fruit Salad’ (Arndt, New Jersey) has a fruity scent.

Cultivar: ‘Apple Cider’

Synonyms: ‘Cody’

Origin: Dorcas Brigham, Village Hill Nursery, Williamsburg, Massachusetts, pre-1955

Description: more compact than ‘Fragrans’, the leaves lighter green, larger, usually kidney-shaped

Cultivar: ‘Old Spice’

Synonyms: ‘Logee’

Origin: Ernest Logee, Danielson, Connecticut, c. 1948

Description: erratically lobed leaves with handsomely ruffled margins, flowers like ‘Fragrans’

Comments: may be a backcross to P. odoratissimum

Cultivar: ‘Variegated Nutmeg’

Synonyms: ‘Snowy Nutmeg’ and ‘Golden Nutmeg’ were derived from this cultivar and frequently revert from one to the other

Origin: Dr. John Seeley, Cornell University, Ithaca, New York, 1957

Description: irregularly streaked with white

Pelargonium ‘Fragrans’

pheasant’s foot geranium

Important chemistry: The odor of the glutinous, clammy leaves is pungent from up to 25 percent guaia-6,9-diene, 16 to 24 percent p-cymene, and trace to 12 percent citronellol in the essential oil of the cultivated species. Hexyl butyrate and trans-2-hexenyl butyrate are the principal constituents of the oil of wild- collected material.

A cultivar derived from this extremely variable species follows.

Cultivar: ‘Viscossimum’

Origin: originally thought to be a natural species raised from seed obtained from Cape Province, South Africa, but more probably a variant of P. glutinosum

Description: habit of P. glutinosum but the leaves are more deeply lobed, the lobes narrower and more strongly toothed; flowers very small, short-spurred, five to eight in a flat flower cluster, petals nearly equal, lilac or white streaked with red on the upper two

The true P. graveolens is similar to P. radens, but it is not now in general cultivation. The plant usually sold as P. graveolens in North America is actually ‘Graveolens’.

Important chemistry: This is peppermint-or rose-scented geranium with 7 to 83 percent isomenthone, 19 to 42 percent geraniol, 0 to 18 percent citronellol, 1 to 13 percent linalool, and around 11 percent citronellyl formate in the essential oil.

The ‘Graveolens’ hybrids (P. capitatum ×P. radens or P. graveolens) include both minty and rose-scented forms. They were once designated by taxonomists as P. ×asperum Willd., but close examination of Willdenow’s type specimen in Berlin reveals that the latter is a hybrid involving P. quercifolium or maybe P. panduriforme Eckl. & Zeyh. As further proof of the hybrid origin of this series of geraniums, we have yet to find any fertile pollen, and all plants that we have counted so far have a chromosome number of 2n = 77, supporting J. Payet and other researchers around the world who have not only examined the chromosome numbers of these hybrids and their parents but also created synthetic hybrids.

Pelargonium‘Graveolens’

Pelargonium ‘Graveolens’ (syns. ‘Old Fashioned Rose’, ‘Rosé’, not P. graveolens) is the hybrid usually sold in North America as P. graveolens, which it closely resembles in morphology. It has narrower leaves, with more deeply cut lobes, than P. graveolens and the harsh hairs of P. radens. Because seed propagation has occurred here, introducing slight variation, we (again, following the English experts) designate ‘Graveolens’ as a cultivar group, or what used to be called a grex (a term taxonomists used to describe a collection of clones from the same cross) rather than one clone.

While the essential oil constituents of ‘Graveolens’ are not influenced by fertility, they are greatly influenced by water stress and altitude. France and China supply most of the rose geranium oil to the United States. ‘Graveolens’ is also raised commercially on the Island of Réunion, having been introduced in 1800, and the commercial product is called “Bourbon Geranium.”

Around 1900 ‘Graveolens’ was introduced from France to Algeria, Egypt, and Morocco, where it became known as “African geranium” in the commercial trade. A characteristic feature of the Bourbon Geranium oil is the presence of 4 to 7 percent guaia-6,9-diene, which is present in African geranium in only trace quantities. African geranium is characterized by the presence of 4 to 5 percent 10-epi-gamma-eudesmol, which is not present in Bourbon-type oils. Rose geranium oil is greenish at first, becoming yellow with age. The odor is green, leafy-rosy, with a sweet-rosy dryout. Rose geranium oil is widely used in perfumery, blends well with almost everything, and displays antimicrobial activity. The essential oil is considered GRAS at 1.6 to 200 ppm.

Important chemistry: The essential oil of P. ‘Graveolens’ is 8 to 51 percent citronellol, 1 to 28 percent citronellyl formate, trace to 23 percent geraniol, trace to 18 percent beta-caryophyllene, 0 to 16 percent linalool, and 0 to 10 percent geranyl butyrate (rose)

Selections of this hybrid complex sometimes listed in catalogs and books include ‘Candy Dancer’, ‘Crowfoot Rose’, ‘Fragrantissimum’, ‘Giganteum’ (‘Giant Rose’), ‘Granelous’, ‘Grey Lady Plymouth’, ‘Marginata’, ‘Peacock’, ‘Roller’s Sigma Variegated Rose’, ‘Silver Leaf Rose’, and ‘Variegatum’. Other selections that seem to fall with in this hybrid complex follow.

Cultivar: ‘Bontrosai’

Origin: 2005 (U.S. PP15,918) by Boekestijn-Vermeer, Klazina, Naaldwiji, Netherlands, reputedly derived from ‘Graveolens’ by UV-radiation and hormones

Description: contorted, curled leaves

Cultivar: ‘Camphor Rose’

Synonyms: ‘Camphorum’

Origin: c. 1900

Description: similar to ‘Graveolens’ in growth habit but coarser throughout, leaves larger and bristly haired, flower cluster similar but flowers rose-pink

Essential oil: 22 percent menthone, 15 percent isomenthone, and 10 percent geranyl butyrate (minty rose)

Cultivar: ‘Charity’

Origin: reputedly a sport of ‘Graveolens’ discovered by Dr. Durrell Nelson, Nauvoo Restoration, Illinois; distributed by Glasshouse Works, Ohio

Description: golden green leaves with deeper green veining and centers

Origin: Chicago Botanic Garden, 1970s; distributed by Mary Peddie, Rutland, Kentucky

Description: very large leaves, up to 6 inches (15 cm) across

Cultivar: ‘Cinnamon Rose’

Synonyms: ‘Cinnamon’; this is often listed as P. gratum Willd. (a species of unknown origin) and more than one ‘Cinnamon’ clone exists, but the most common clone with this name is rose-scented with a hint of cinnamon

Origin: Fred Bode, California, 1950s