Our desire to research BDSM practices and risk-taking behaviors among men who have sex with men (MSM) emerged several years ago and is aligned with previously funded ethnographic research projects on bareback sex, gay bathhouses and risks, online gay cruising and risks, and “swingers” and risk-taking behaviors – all funded by CIHR, the Canadian Institutes of Health Research. After three unsuccessful CIHR applications in which the BDSM project was rated “good … but not a CIHR priority,” in the spring of 2015 we turned to the University Medical Research Fund (UMRF), from which our first application received immediate funding.

Although we have been preparing the fieldwork for this research project for three years, lack of funding meant that data collection was deferred until the summer of 2015. During this three-year “forced waiting period,” we held regular meetings with a contact person in Toronto, Canada, and prospective participants awaiting clearance from the research ethics board. Between 2012 and 2015, during regular meetings with our Toronto contact, we elaborated the theoretical framework and discussed methodological and ethical issues. From these discussions, the Toronto contact helped design a self-administered questionnaire and the interview guide. This same person introduced us to the BDSM community and “scene.” Compared to similar research conducted in related fields involving men who have sex with men (MSM), this project required extensive investment/preparation as part of the fieldwork. We feel compelled to add here that this is, by far, the most intriguing research program we have ever conducted in the field of nursing and sexual health – and a potentially subversive one for a discipline known to be conservative. Because the content of this chapter is in continuity with that found in Chapter 5, please refer to the previous chapter for the research context and questions, as well as for methodological clarifications. The present chapter explores a specific category – degenitalizing the sexual – which appears under the overarching theme of “performing BDSM practices.” Our purpose is to contextualize what it might mean to degenitalize sexual practices, or to use Deleuze and Guattari’s term, to deterritorialize the erotic terrain of sexual pleasure and to bring BDSM practices into conversation with health research and clinical practice.

Mobilizing the poststructuralist scholarship of Deleuze and Guattari (1972, 1987), this chapter refers explicitly to their concepts of lines, machines, and the body-without-organs in order to interpret the empirical data collected over the course of four months in three major metropolitan Canadian cities.

According to Deleuze and Guattari, the body is a political surface marked by three types of “lines”: molar (rigid), molecular (soft), and lines of flight (resistance). Molar (or “segmentary”) lines are the most visible; they are the effects of family, school, social and biological sex, profession, social class, etc. It is difficult, if not impossible, to move between these rigid lines. For example, it is difficult to alternate between childhood and adulthood because one state (childhood) excludes the other (adulthood). With the more flexible molecular lines, however, some modification of the coding defined by molar lines is possible. The effects of these lines are rarely seen; they are subtle to the point of imperceptibility. The third and last kind of line, lines of flight, can create a permanent rupture from molar and molecular lines. Such radical effects are irreversible. Lines of flight are often associated with Deleuze and Guattari’s concept of resistance. All three lines are both intrinsic and interdependent. Always present simultaneously, they inform identity development. According to Antonioli (2003), reading people as an entanglement of lines like those presented above “forces thinking about thoughts that disgust, the possibility of terrifying radical multiplicity and unpredictability. Subjectivity no longer appears as the result of linear development over time … [instead,] transformations are unpredictable and completely disrupt preexisting reality. The individual … is the product of assemblages” (pp. 29–30, original translation).

These three lines that mark (or map) the body are key to understanding the empirical data presented in this chapter. There is no doubt that (rigid or segmentary) molar lines result from socially transmitted “binary machines” that eventually produce what Antonioli (2003) calls an organizational plan. Permeated by micro-powers that, more often than not, elude the State and its apparatuses, this immense apparatus of (sovereign, disciplinary, pastoral) power structures bodies and minds, especially in relation to pleasure and desire. These binary machines are therefore responsible for dichotomous categories: good/bad, moral/immoral, etc. Based on the definition of binary (social) machines that, in some sense, produce molar or “segmentary” lines, it can be concluded that the body (along with its pleasures and desires) is coded (mapped and territorialized) by unrelenting social prescriptions from which it attempts to liberate itself through the means of molecular lines. Consequently, forms of alternative sexualities, including BDSM, express the essence of molecular lines and therefore constitute molecular sexualities within which new pleasures and new “sexual” practices are explored. In alternating between molar and molecular lines, the body acts in radical ways to escape the turmoil, and this creates lines of flight.

By introducing new and often unpredictable elements (e.g., intensities of desire, practices, and pleasures), these lines of flight are able to rupture with molar and molecular lines. Ultimately, the radical effect of lines of flight is to produce permanent changes in somatic (e.g., scarification) and psychosomatic (e.g., orgasmic intensity) structures. For example, the practice of “fisting” (extreme stretching of the anal sphincter and resulting pleasure) may represent a radical form of flight in the context of social prescriptions concerning sexuality. It is understood that the actions of segmentary lines (social prescriptions – judgment, stigmatization) are unrelenting, as are those of molecular lines. The activation of lines of flight does not spell the dissolution of the other two types of lines, but rather creates a space (of resistance) where permanent changes, however small, are possible. Where, on the one hand, there is territorialization, inscription, striation, sedentarism, and coding (i.e., segmentary lines), on the other hand we find deterritorialization, flux, nomadism, and uncoding (i.e., molecular lines and lines of flight); and, finally, in response to these movements, there are attempts at reterritorialization, capture, and overcoding (segmentary lines). BDSM practices, like molecular sexuality, might be said to constitute modes of deterritorialization with significant effects on the body and its pleasures. Despite the spaces of freedom that such practices can offer practitioners, the effects of segmentary lines (religious, public health, and other discourses) always remain present.

With regard to these three lines, Deleuze and Guattari recommend caution. While molar or segmentary lines are understood as responsible for the dangers associated with the apparatus of power, Deleuze (Deleuze & Parnet, 1987) argues that molecular lines and lines of flight are capable of concealing still more terrifying dangers:

We have left behind the shores of rigid segmentarity, but we have entered a regime which is no less organized where each embeds himself in his own black hole and becomes dangerous in that hole, with a self-assurance about his own case, his role and his mission, which is even more disturbing than the certainties of the first line.

(pp. 138–139)

It is therefore not a matter of naïvely praising marginality, radicalism, and flight at all costs, but rather of “finding a balance between the different lines of which we are made” (Antonioli, 2003, p. 35, original translation). In sum, individuals and groups are made up of “lines”: molar lines of rigid segmentarity made from molecular fluxes and lines of flight that cut directly across bodies and pleasures and that launch us into the unknown; there is a movement between stability (molar) and rupture (molecular).

The case of binary machines was previously discussed in the context of their theoretical relationship to processes of social prescription, of which segmentary lines are initial vectors. This section focuses on the concepts of the desiring-machine, despotic-(social)-machine, and war-machine.

Deleuze and Guattari’s (1972) use of “machine” is not metaphorical, quite the opposite. Indeed, Deleuzo-Guattarian machines are characterized by their ability to produce flux, to cut these fluxes and, most importantly, to connect flux to other machines. For Deleuze and Guattari (1972), a person (or one of their parts), themselves a machine, “fait pièce” with other things (is “of a piece” – with tools, animals, people, parts of a person, etc.) and thus constitutes another machine or machines. Here, it is easy to imagine different “faire pièce” or machine-combinations in the case of BDSM practices: fist and anus, whip and back, sound and penis, leather and body, nose and smell of rubber, eyes and pornography, and more.

Desiring-machines result from the combined force of social productions and desiring-productions. This means that desiring-machines do not exist as entities external to social desiring-productions because they are the basis on which desiring- productions (desires) are formed. Indeed, Deleuze and Guattari (1972) state in Chapter 1 of their book L’Anti-Oedipe that “the desiring-production is nothing other than social production” (p. 37, original translation). Therefore, desire is not explained by absence, but by the unrelenting social production of these desires that, sooner or later, become our own. Desire does not seek an absent object, but produces and functions: desire is first and foremost a machine (Antonioli, 2003). Jeffrey Weeks states it succinctly in his preface to Guy Hocquenghem’s (1993) Homosexual Desire: “Deleuze and Guattari see man constituted by ‘desiring-machines.’ Infinite types and varieties of relationships are possible; each person’s machine parts can plug into and unplug from machine parts of another. There is, in other words, no given ‘self,’ only the cacophony of desiring-machines” (p. 31).

The essential mechanism of the despotic-(State)-machine (DsM) is that it brings together the components (“dispositifs” or apparatuses) necessary for inscription and overcoding. These new inscriptions, or codes, supplant earlier (primitive) inscriptions, thus forcing their replacement (or overcoding). For Deleuze and Guattari (1972), the despotic-(State)-machine is a system of power and codes (inscriptions). This machine not only (over)codes (disciplines) territorial elements (bodies), but it also “invents specific codes for flows that are increasingly deterritorialized (lines of flight, e.g., resistance), which means: putting despotism in the service of the new class relations … everywhere stamping the mark of the Urstaat on the new state of things” (Deleuze & Guattari, 1972, p. 218, original translation). This despotic-machine is repressive in that it creates a rigid (molar) state apparatus invested in regulating behavior. As desiring-machines, people are subject to a variety of social prescriptions and protocols imposed upon them. In Weeks’s words, “capitalist society cannot live with the infinite variety of potential interconnections and relationships [desiring-machines], and imposes constraints regulating which ones are to be followed, i.e., essentially those relating to reproduction in the family” (Weeks in Hocquenghem, 1993, p. 31). In effect, “machinic enslavement occurs when assembled” persons, “social relations and desires, known in Deleuzian theory as ‘machines,’ are rendered subordinate to the regulatory function” of the DsM and are “hence incorporated in an overarching totality” (Robinson, 2010, p. 4). “This process identifies Deleuze and Guattari’s view of the state-form with Mumford’s idea of the megamachine, with the state operating as a kind of absorbing and enclosing totality … eating up and assimilating the social networks with which it comes into contact” (Robinson, 2010, p. 4). This mega-state-machine aims to destroy horizontal (rhizomatic, nomadic, resisting) connections while increasing the intensity of vertical (arborescent or tree-like) subordination that insists on totalizing principles.

Consequently, the state is viewed as a force of “antiproduction.” “The state as a machine of antiproduction operates to restrict, prevent, or channel these flows of creative energy so as to preserve fixed social forms” (Robinson, 2010, p. 6); by doing so, the DsM restricts the extent of differences fighting to exist. In short, one of its main objectives is to block “subject-formation, or the emergence of subjectivities [persons into BDSM practices, for instance – our addition] not already encoded in dominant terms” (Robinson, 2010, p. 6). On the margins of these rigid state apparatuses emerge spaces of freedom within which molecular lines and lines of flight are activated.

The autonomous war-machine “is an assemblage directed against the state”; it seeks to undermine the state by breaking down channels of power and replacing “striated” (regulated, marked, coded) spaces with “smooth” ones (spaces occupied by resisting persons and groups) (Robinson, 2010, p. 7). It can therefore be rightly said that the “war-machine” is actively involved in the practice of everyday resistance (Deleuze & Guattari, 1986; Robinson, 2010). Marginal groups, such as the BDSM community, termed “minorities” in Deleuzian theory, act as war-machines because state-form sexuality (“vanilla sex”) is inappropriate for them. It is clear that “war-machines are also associated with the formation of special types of groups which are variously termed ‘bands’, ‘packs’ and ‘multiplicities’ ” (Robinson, 2010, p. 7). The BDSM community, like many other marginalized groups, operates as very “dense local clusters of emotionally-intense connections, strongly differentiated from the ‘mass’ ” (Robinson, 2010, p. 7). Men who have sex with men (MSM) and are involved in BDSM practices create opportunities for new forms of sexuality outside vanilla sex; they want to detach themselves from the dominant system, “instead reconstructing different ‘universes’ or perspectives around other ways of” gathering together (Robinson, 2010, p. 8). Through the rethinking of sexual practices, BDSM practitioners unmap the way their bodies (and pleasures) are coded (socially organized). BDSM practitioners’ uncoding practices allow them to become something else.

The body-without-organs (BwO), as its name suggests, is a body without organization or, more specifically, a body that refuses social organization (territorialization). It is therefore a force of deterritorialization. The body-without-organs (BwO) is a metaphor “drawn from Antonin Artaud’s 1975 radio play To Have Done with the Judgment of God” (Wallin, 2012, p. 38). Through the metaphor of the BwO, the body becomes an undifferentiated political surface, a plane of energy on which all desiring productions are possible. This concept is highly relevant for our current research because, depending on the kinds of intensities pursued, the BwO can be composed in different ways. For instance, the BwO of a sadist will differ from that of a masochist who seeks exposure to pain.

Deleuze and Guattari (1987) argue the existence of three forms of BwO: cancerous, empty, and full. The cancerous BwO fails to experiment because it is caught in the routine of everyday life and is overly socially coded. The empty BwO, “[b]rought about by the absolute deterritorialization of flows and intensities … leads to a kind of catatonia.” The full BwO refers to the “productive image of experimentation that avoids becoming over-organized in its cautious approach to deterritorialization” (Wallin, 2012, p. 39). In short, the body-without-organs is a body out of reach; it is an anarchist body.

Analysis of interview transcripts revealed four main themes (see overviews of each in Chapter 5). These themes included “selecting partners,” “performing BDSM practices,” “enjoying transgression,” and “mitigating risks.” An overview of these four themes is followed by a more in-depth exploration of the category “degenitalizing the sexual,” presented last. This category, which falls under the theme “performing BDSM practices,” constitutes the core of this results section. More details on these four themes can be found in chapter 5 of this collection. To situate readers, a brief overview of each theme will first be presented.

The first theme to emerge involves the many factors at play in participants’ selection of BDSM partners, including physical appearance, level of BDSM experience, and preferred roles (e.g., dominant or submissive), as well as how they met these partners and the types of relationships formed. As would be expected, there were differences in participant responses regarding the physical characteristics and level of BDSM experience they preferred their partners to have. With regard to role preferences, participants tended to seek out partners who prefer roles opposite their own, although many participants also reported being versatile with regard to their preferred role. Participant preferences also varied on the subject of whether they preferred meeting BDSM partners online or in person and whether they considered these relationships to be sexual, romantic, and/or solely about BDSM. It is clear that, for most participants, BDSM practices were the focus of their relationships with partners. We will return to this below.

The second theme involves the transgression associated with engaging in BDSM practices; this includes different forms of gratification, participants’ resistance to social stratification, and a desire to normalize kink. While some participants preferred the physical gratification (e.g., pain, stimulation, etc.) associated with BDSM practices, others favored the psychological gratification (e.g., humiliation, submission, etc.) that these practices provided. Regardless of the type of gratification preferred, most participants reported that BDSM’s transgressive aspects, such as resistance to social norms, were essential to their (counter)pleasure.

The third theme to emerge involves risk mitigation strategies used when engaging in BDSM practices, including different forms of harm reduction, open and honest communication between partners, and membership within a BDSM community. Methods of harm reduction include knowing how to prepare for and properly perform different BDSM practices, as well as glove use (for fisting and blood play) and condom use (when sexual intercourse is involved). Participants reported that communication between partners often takes place before, during, and after engaging in BDSM practices. These conversations typically involve discussing each player’s interests and limits, negotiating which practices will be performed, using a safe word to alter or end play if necessary, and following up to ensure that no lasting injuries were caused. Being part of a BDSM community was another method of risk mitigation, as community members are regularly exposed to formal and informal education on the topic, and dangerous or unethical players are identified and excluded from the community.

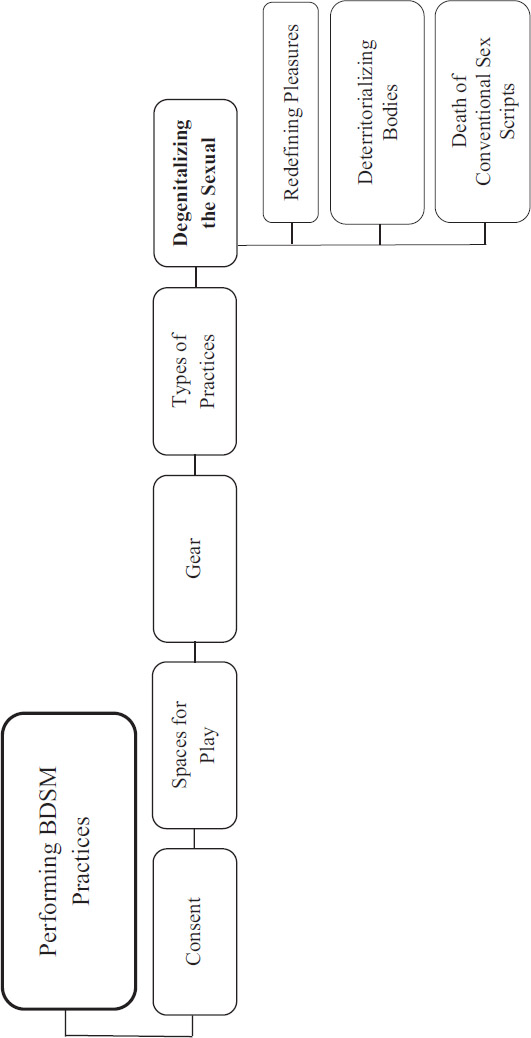

The final theme to emerge constitutes the core of this chapter: “performing BDSM practices” (see Figure 6.1). This includes consent to practices, spaces where practices are performed, different types of gear and accessories, specific types of practices, and (for most participants) the absence of genital gratification, here purposely referred to as degenitalizing the sexual.

Participants reported that consent to practices is of utmost importance and that BDSM practices can take place in public or private venues, each with their own specific risks and benefits. Participants use a variety of gear, accessories, and clothing when engaging in BDSM, some of which are related to specific practices (e.g., floggers for percussion play) and some of which depend on personal preference (e.g., leather or rubber; type of lube). The list of practices reported by participants, which is quite long, includes fisting, bondage, percussion play, cutting/piercing/scarification, electricity play, watersports, urethral sounds, and more. This theme also includes a category we refer to as “degenitalizing the sexual,” which illustrates participants’ indifference to and/or unconventional use of genitals and genital stimulation within their BDSM practices. This significant category is subdivided into three subcategories: (1) redefining pleasures (2) deterritorializing bodies, and (3) the death of conventional sex scripts.

Traditionally, most forms of “sexual” activity place a strong emphasis on genital stimulation, often in the form of penetrative or oral sex. One participant explained the BDSM community’s general perception of conventional sex and demonstrated that BDSM most often involves activities of a distinctly different kind:

Sex that just involves sort of anal sex and oral sex… . People call it vanilla … it’s been a long time since I’ve had that kind of sex. I would say that for the last, at least for the last couple years, it’s been either fisting or BDSM.

(TO1, 8)

Unlike conventional (i.e., “vanilla”) sex, many BDSM practices take the focus away from the genitals and instead concentrate on stimulating other areas (surfaces) of the body. As one participant explained, BDSM practices do not need to include genitals or genital stimulation in order to be considered sexual or pleasurable:

Whether it’s flogging or any other kind of BDSM play, for me it’s all sexual and it’s all intimate … it’s about playing with the body and stimulating it, you know? Giving people pleasure and receiving pleasure.

(TO3, 8)

Some BDSM practices ignore the genitals but still involve the physical stimulation of other parts of the body, such as percussion play (i.e., spanking, flogging, etc.), fisting (we include neither the anus nor the mouth in our definition of the genitals), and cutting/piercing. The diversity of sensations reported by participants shows that physical sensations are polymorphous, taking many forms even when only one type of practice is involved. The following excerpts pertaining to fisting and intermuscular injection show the variety of sensations one can experience:

There are so many varied anal sensations that you experience when being fisted … if someone is good at it, I like being fisted deep.

(TO5, 10)

If [a needle] goes deep into the muscle, for example, then it’s a different kind of pain, it’s a hard thumping pain. And if it’s too shallow, it’s a stinging kind of pain.

(TO2, 13)

Focusing on psychological rather than physical gratification is another way BDSM practices can redefine conventional sexual pleasure. Participants explained that, when engaging in BDSM practices, psychological gratification can be as or more important for sexual arousal than physical stimulation. This may be one reason why BDSM practices involve less genital stimulation than so-called “vanilla” sexual activities.

It’s not all leather, it’s not all kink. There’s the individual involved … everything starts in the mind … usually goes through then comes back to the mind.

(TO4, 13)

A fetish is a fetish, it’s something that you need in order to get off … [if] a man is into women’s clothing – it’s a fetish. And that’s … gratification whether he has an erection or not.

(TO2, 20–21)

Participants reported being sexually aroused by a number of different BDSM practices that require no physical stimulation, including submission, humiliation, and degradation. In these cases, sexual arousal occurs in response to various environmental and situational factors, such as power dynamics between players, being spoken to in a particular way, or experiencing feelings of helplessness.

It’s hard to separate sometimes the joy that I get in [Master] receiving the pleasure, and being used for his pleasure. That’s really what drives me: it is submission.

(TO1, 10)

Get a guy’s dick out and humiliate him about it, and that might turn him on – degradation.

(TO4, 13)

Sensory reduction… . Hoods, gags, blindfolds, mummification is nice too. You know, all in the theme of making them available as a sexual toy that they cannot resist – even though that it’s consensual.

(MTL2, 3)

Some BDSM practices that are intended to produce psychological gratification do so using some form of physical stimulation. In these practices, however, the goal of stimulation is not necessarily to cause sexual pleasure; it can cause different degrees of pain:

Well, if you think tickling, it’s the element of control and so on, and the so-called exchange of power.

(TO4, 13)

There’s an aspect of humiliation that can be involved in [piercing]. So you can do patterns, you can do things like hang things from it so that there’s added pain.

(TO2, 13)

Another possible explanation for participants’ apparent indifference to genital stimulation is that anal fisting was the most commonly reported practice. All ten participants reported practising fisting (insertive or receptive). Since this practice seems to occur less commonly in the general population, and thus may be unfamiliar to readers, one participant provided the following description:

In the rectum, you’re basically going to move around depending on what the bottom likes [the person receiving the fist]. Some like gentle rotations, some will like vigorous rotations, some like gentle movement back and forth.

(MTL2, 18)

Participants explained that genital stimulation is rarely combined with the practice of fisting, particularly because both partners are focusing all of their attention on giving and receiving anal stimulation:

Most of the time you’re fisting guys they’re not erect … and nobody cares. Like, it’s really not about the penis at that point. It’s really what’s happening with their ass.

(TO1, 32)

Once I got interested into fisting, the hand is just so much more interesting.

(TO5, 9)

One reason for this dedicated focus on the anus may be the fact that anal fisting carries a number of serious risks if performed improperly. As a result, participants strongly emphasized that fisting requires a great deal of patience and practice, both for the fister (top) and the person being fisted (bottom). Fisting tops need to learn and practice how to safely insert a fist into their partner in order to avoid perforating the bottom’s rectum or colon. In contrast, fisting bottoms must practice relaxing their anal sphincters and learn to become familiar with the intense sensations (which come primarily from stretching the anal sphincters) so that they become pleasurable rather than uncomfortable, painful, or overwhelming.

Once you’ve had the fist pop in … it’s like, “Oh my God, this thing’s never coming out and I’m going to die here or he’s going to rip me to shreds.” But once you get used to it, it’s a feeling like, unlike anything else, any other sexual experience.

(TO5, 15)

Many participants agreed that anal fisting is the most pleasurable BDSM activity in which they engage, which explains why the concept of disciplining (i.e., training) the anus to be fisted was commonly reported. One participant explained this process:

You can’t make an omelette without cracking a few eggs, right? So it’s the same with anal play … start with something smaller and work your way up. And it’s going to involve some stretching, and that will hurt a bit because, you know, there will be micro tears and things like that.

(TO3, 21)

Disciplining the anus for more extreme versions of this practice, such as very deep fisting and what is referred to as “punch fisting,” was also reported. Participants gave examples of how deeply it is possible to fist someone, but emphasized that this degree of fisting requires substantially more discipline and experience.

With very experienced fisting bottoms, you can be up to the shoulder.

(MTL2, 18)

There are guys who will go up to … about the bicep. Basically you go up the vertical colon and then you come across the transverse colon … that takes an awful lot of practice.

(TO4, 8)

The one guy that I fisted the most with … he’s had guys up to his elbow. I would like to get there someday, but I’m not there.

(TO1, 30)

Participants described the practice of “punch fisting” and explained that this is another version of fisting that should only be performed by experienced tops and bottoms.

You can reach a point with very experienced bottoms where it’s called punching, where you’re bringing the hand out and going back in as a fist.

(MTL2, 19)

Somebody really has to be good to do [punch fisting] well. Because it’s so fast, you really have to be precise in terms of … where you’re doing the act.

(TO5, 17)

In contrast, when engaging in fisting with players who have less experience or are still in the process of training their anus to receive a full fist, the practice may be performed quite differently. As one participant explained:

A lot of guys are very early in fisting, and you’ll never get your fist in … then really it’s just sort of ass play with as many fingers as can go.

(TO5, 5)

The fact that disciplining the anus for the purpose of fisting can be time consuming and involve some initial discomfort may cause people to wonder what makes this practice worthwhile. As one participant explained:

I’ve had a taste of somebody going deeper. I’ve had somebody place maybe four fingers through my second ring, and the sensation of being that open and that full is just so incredible. I just think it’s just going to get better and better.

(TO1, 31)

Additionally, many participants explained that they continue to work on disciplining their anus because the sensations they experience when being fisted are actually more intense and pleasurable than any form of genital stimulation.

I prefer getting fisted because it’s probably the most intense pleasure I ever get.

(MTL2, 9)

I suppose if I just were more used to [anal sex] then it would be more pleasurable … but certainly fisting is the most amazing experience in the universe. I mean, it’s just incredible.

(TO3, 11)

Genital stimulation is also considered less relevant because, unlike conventional sexual activities, the pleasure received from engaging in BDSM practices is not necessarily related to reaching orgasm. This is especially true of the practice of fisting. For most participants, focusing on anal rather than genital stimulation and sensations meant that reaching orgasm is not required when engaging in this practice:

Sometimes the BDSM is even better … cumming almost becomes secondary in terms of some of the intensity.

(TO5, 16)

The feeling is so different than normal genital manipulation, they’re not really interested in cumming… . Just the sensation of being stretched and being filled, that’s what most fisting bottoms are looking for.

(MTL2, 20)

The lack of genital stimulation and orgasm associated with BDSM practices is one explanation as to why participants rarely mentioned semen. However, some participants did report becoming sexually aroused by playing with other bodily fluids, such as urine and blood. When participants described the presence of urine in their BDSM practices (also referred to as “watersports”), it involved urinating on a partner or in a partner’s mouth:

Sometimes someone’s pissed in my mouth, that’s hot.

(TO5, 9)

It’s fun if it’s to kind of end a scene … kind of piss on your partner and the sling. And my partner’s really into that too, he loves that when I do it.

(TO3, 4)

The presence of blood was mentioned more frequently than watersports, which may be related to the fact that cutting and piercing were two commonly reported practices. However, participants explained that people have different limits with regard to how much blood they find pleasurable:

The last time actually was the most blood … actually there was a puddle on his mat and … I was like, “Wow. That was a lot of blood.” That was pretty cool.

(TO1, 12)

Other people like the idea of very gentle cutting, so it’s just the tiniest bit of blood, completely superficial.

(TO4, 6)

The deterritorialization of bodies can refer to separating the body from conventional (“vanilla”) sexual practices (such as oral and penetrative sex) and involving it in practices that are not within the realm of conventional sexual activities (ongoing interplay of rigid, segmentary, or molar lines with soft or molecular lines), but are being performed to obtain different forms of pleasure (lines of flight). Deterritorialization is associated with a number of BDSM practices and can occur in different forms, depending on what these specific practices are and how they are being performed. This can involve repurposing body parts traditionally associated with specific sexual activities, such as the genitals, by stimulating them in a way that would be considered radically different from how they would normally be stimulated for pleasure. One BDSM practice involving repurposing the genitals is cock and ball torture (CBT), which stands in stark contrast to the kinds of genital stimulation usually associated with the penis and testes.

| Researcher: | Cock and ball torture? |

| Participant: | Well, there are things like Wartenberg wheels, which are the pinwheel device for the reflexes, so you can use those. |

(TO3, 2)

He doesn’t have anything to do with my penis, except hitting it.

He’s hit my penis, he’s flogged it, and that always makes it hard.

(TO1, 11)

Another example of deterritorializing bodies (which are mapped in certain ways to attain pleasure) occurs when engaging in BDSM practices that do not involve the genitals and are not traditionally considered sexual, such as cutting or whipping someone, but are performed for the purpose of sexual arousal. Participants provided the following examples:

I’ve gone further in flogging with him than anyone … marks that have lasted for a very long time, welts and bruising and everything. So he gets a lot of pleasure from that.

(TO1, 21)

I remember the first time I put a needle in somebody … it’s entering a person in a way that you’re not supposed to, and it’s for sexual gratification, and it was just exciting, just exhilarating.

(TO2, 13)

As seen in these two examples, giving and receiving pain is one way of deterritorializing the body associated with some BDSM practices. Participants who engage in practices traditionally considered painful rather than pleasant reported that the sensation of pain can actually be interpreted as being both pleasurable and sexually arousing. As one participant further suggested, Deleuze-Guattarian lines (segmentary lines and lines of flight) are once again (theoretically) mobilized here:

I think you’re conditioned, rightfully so, to react to pain and intense sensation by pushing away, because … your body is telling you there’s something wrong here, right? So it takes experience to not push away but actually embrace it, and enjoy the sensation for what it is. And once you do that it’s, it’s incredible. It’s pleasurable. It’s intense.

(TO1, 35)

Pain is a very interesting thing. There’s so many different kinds of it, and some of it is just really challenging to bear, and some of it is really pleasurable, and some of it is very erotic.

(TO1, 10)

Inserting urethral sounds is another BDSM practice that involves repurposing the genitals but does not involve the sensation of pain. Participants recommended starting with smaller sounds and gradually increasing the size of the sound in order to stretch the urethra. Although this practice may appear painful to those who have not experienced it, it was described as being quite pleasurable and only causing pain when the sound is too large.

Sounds are medical devices that were originally meant to clear blockages or to stretch the urethra and so we use those.

(TO2, 5)

You’ve got this smooth steel rod sliding in and out of your cock … when it gets down past a certain point … there’s a muscle that is the ejaculation muscle, and you can actually fuck that with the sound.

(TO3, 21)

Another means of deterritorializing bodies commonly reported was the use of electricity on the genitals and anus; this practice repurposes both erogenous zones and electricity. Participants reported that this practice caused very unique and pleasurable sensations and, similar to urethral sounds, is not intended to cause pain. Consequently, it was emphasized that the type of electricity used for this purpose differs from regular electrical currents, which could cause significant harm if used for sexual play.

All of the electrical stuff has been manufactured specifically for … below the waist. So it’s for … anus and cock and balls.

(TO2, 7)

With electricity, you can do crazy things … it can almost feel like the electricity is fucking you in a pattern. You can use electricity to almost jerk off your cock, so it’s almost like somebody’s hand, but it’s electricity.

(TO1, 35)

Compared to conventional (“vanilla”) sexual activities, which are usually engaged in for relatively short periods of time, BDSM sessions often take place over extended lengths of time, especially if being performed in private rather than public venues.

A session … if it’s in a public space, you sort of have to give everyone the chance to play, so it may go 20–30 minutes.

(MTL2, 26)

Some people will say it’s going to be an evening or an afternoon, other people will say it’s going to be Saturday or it’s going to be a weekend. With some people it’s a whole week.

(TO4, 28)

The length of these sessions is likely related to the fact that BDSM involves an extensive amount of foreplay. In fact, given that sexual orgasm is not obligatory, an entire BDSM play session could be considered an extended foreplay session. As previously mentioned, participants indicated indifference to receiving genital stimulation and reaching orgasm when engaging in BDSM practices. This may explain their desire and ability to engage in extended amounts of foreplay since, traditionally, genital stimulation leads to reaching orgasm, which signifies the end of sexual activity. In addition to focusing less on genital stimulation and orgasm, participants developed other strategies to help extend the amount of time they are able to play.

We’re drinking fluids, and I have fruit and chips and things like that as well, to snack on in between. And … we take breaks and well we also have the videos [porn] running on the screen so we’ll just take a break and kind of watch that for a little bit.

(TO3, 14)

We always have Gatorade, other liquids, water … we leave the playroom, which is down there. Come out for air, that sort of thing.

(TO5, 4)

Another reason why BDSM sessions may take place over extended periods of time is that the players involved often feel that BDSM practices include a performance aspect, which explains why play sessions are often referred to as “scenes.” Participants explained that engaging in BDSM is more meaningful than just participating in a sexual activity:

Think of BDSM as theatre, because it is. You have a stage that’s set, has set decoration on it. You have actors in costumes, they play roles, and the story plays itself out, right? It’s a theatre and the audience is the players.

(TO4, 16)

All BDSM play is an art … when you’re working on somebody, with their body, it’s like playing a musical instrument. And you’re giving a performance … and you see that they’re being affected by it.

(TO3, 12)

Roleplay is one example of how BDSM practices can be likened to a performance, despite having no audience (a Lynchean scene – Club Silencio; see the movie, Mulholland Drive). The most commonly reported type of roleplay involved rape scenes, in which one person pretends to be non-consenting, despite the fact that the sexual activity is completely consensual. Since the bottom may be using words like “stop” or “don’t” as part of the scene, an unrelated “safe word,” which can be used at any time to stop the rape scene, is often decided upon beforehand.

The perfect rape scenario … I’d be sitting here or maybe sleeping and somebody would break in and rape me at knifepoint or something, force themselves on me. Yeah, that’d be nice.

(TO1, 25)

If it’s a rape scene, well yeah, if you want it to be really real then it’s going to be rough and you need a mechanism that’s going to work. And frankly, the mechanism is to use the safe word and away you go.

(TO4, 26)

One participant mentioned the interesting concept of “consensual non-consent.” This was described as being different than rape scenes, which are fully consensual unless the safe word is used and ignored. It was noted that scenes involving “consensual non-consent” rarely include novices, as a significant level of BDSM experience is required:

The consensual non-consent is effectively saying, “Yeah, you can do anything to me, and it doesn’t matter whether I care about it.” So in effect it’s no safe word, it doesn’t matter what you do. I can’t get out of this scene.

(TO4 27)

The variety of methods for deterritorializing bodies that occur within BDSM practices, such as repurposing the genitals and engaging in extensive (and physically exhausting) foreplay and performance, demonstrate a radical shift away from the conventional (vanilla) sex scripts traditionally imposed upon us. Conventional sex scripts, which primarily involve manual and/or oral sex, penetrative intercourse, and orgasm, are, in part, being rejected by the BDSM community in favor of sex scripts that are more diverse, transgressive, playful, and which involve redefining “traditional” sexual pleasures.

I think people are starting to identify that they have interest beyond just fucking and sucking … there’s this big umbrella called BDSM, and there’s so many things.

(TO2, 20)

Conventional sex scripts also emphasize monogamy in sexual relationships, which is contrary to what was found among BDSM participants. Most participants were in open relationships, meaning that they have a primary partner but are also allowed to engage in sexual activities with other people. The lack of jealousy and insecurity that exists between partners as a result of being in an open relationship is an impressive and admirable aspect of these nonconventional sex scripts:

I was more of a receptive fisting bottom… . My husband tried but he wasn’t really into it, so I was going to other people to have that need met.

(MTL2, 5)

I went on [PrEP] originally to serve my Master, and I haven’t taken advantage of it in the other context at this point, but he’s now given me permission to fuck other guys.

(TO1, 7)

For many participants, the death of a conventional sex script not only involved being in an open relationship, but also included becoming orgiastic (i.e., engaging with many individual partners and in group sex). However, participants’ preferences differed regarding the specific details of orgiastic behavior, such as the number of people involved and the context in which it occurs:

I wanted a dozen leather bikers to fuck my face and fuck my ass over a motorbike. Great scene.

(TO4, 26)

I prefer either an intimate party at home or a play party that’s been organized … in a space that we’ve set up and where we know the people.

(TO3, 23)

Conventional sex scripts traditionally have a small and fixed number of possible sexual activities (usually performed privately), whereas sex scripts within the BDSM community often involve combining a number of different practices. This may be due solely to the fact that BDSM encompasses such a vast range of practices to begin with, but may also be a result of BDSM players being more open-minded about sexuality and sexual activities and thus more creative with their practices. The diversity of BDSM practices and potentially endless variety of combinations indicate that BDSM sex scripts can be significantly different not only from conventional sex scripts, but also from each other.

Rubbing my forearm, you know, on his butthole drives him crazy … mixed in with occasional slaps and sticking my tongue in there … it’s all a part of the build-up.

(TO3, 9)

I could do flogging beforehand… . There can be watersports, piss involved, sounds, urethral play, and anal stimulation at the same time.

(TO2, 4)

You’ve got lots of leather on, someone’s attached a variable speed sander that he’s adapted to your cock and balls and meanwhile he’s put a milker on me and so he’s milking me at the same time.

(TO4, 4)

The emergence and increasing popularity of BDSM has prompted a shift away from the predictability and rigidity associated with conventional (vanilla) sex scripts. However, this change continues to be met with societal resistance, despite the existence of research indicating that people who engage in BDSM practices are psychologically well-adjusted.

One participant explained why he believes so many people have difficulty letting go of the conventional sex script in favor of exploring and embracing their unique sexual desires:

It’s the indulging that a lot of people refuse to give themselves, right? They won’t let go and just indulge their kink, their fantasies, their sexuality. It’s all sort of guilt, religious guilt, or parental guilt … and it’s part of a process, I think, getting over that.

(TO4, 15)

Following the presentation of results, we have attempted to organize our discussion according to three distinct but interrelated discussion segments: (1) poststructuralism and queer theory; (2) degenitalization and the subversion of “straight” sex; and a brief concluding section, (3) personal reflections.

Public health prevention strategies are a form of governmentality (Lupton, 1999) that provokes resistance when professionals attempt to impose the same approach across diverse members of society. This is especially true in the case of already marginalized populations, such as BDSM practitioners. Because of this, public health interventions need to avoid “one size fits all” approaches and must instead be tailored to the individual needs of specific populations and subcultures. As presented in chapter 5, BDSM practitioners have adopted public health principles and incorporated them into their practices. That being said, BDSM practices are the products of desiring-machines, which are forever in transit and always exploring new intensities and new ways of being; these machines font pièce with other machines and therefore make connections with odors (leather, rubber), objects (whips, dildos, sounds), body parts (fist, teeth, anus, penis), and persons (bodies, seminars, conferences, parties). BDSM connections (assemblages) are part of an ongoing experimentation of oneself with other objects/subjects. These assemblages function as a means to undo the effects of the despotic-(State)-machine that embodies the heterosexual normative prescriptions pervasive in many apparatuses (“dispositifs”), including public health.

A poststructuralist perspective, like the one used throughout this chapter, supports the analysis of power relations at the individual and collective levels (Federman & Holmes, 2000; Holmes, 2002; Holmes & Federman, 2003a, 2003b). Therefore, in our opinion, such an approach is necessary in order to expand the forum of public health discussion to include marginalized and minority populations, including BDSM practitioners. A poststructuralist approach also assists in reforming public health messages intended for this diverse group of individuals. Through the work of Deleuze and Guattari, poststructuralism constitutes an appropriate theoretical lens through which to understand the practices involved in BDSM, and its associated risks, while being sensitive to dominant discourses (e.g., public health) and competing discourses (pleasure/desire and risky sex) surrounding this subculture. The queer theoretical perspective, moreover, is invaluable to better understand the phenomenon under study. Queer theorists have already demonstrated the impossibility of any “natural” sexuality, thus constituting an alternative way to conceptualize the “sexual.” One central tenet of queer theory is that gender operates as a regulatory construct, and that the deconstruction of normative models of sexual practices legitimates certain socio-political agendas (Jagose, 1996). Queer theorists have also been very active and successful in attempting to understand BDSM and its practices (Bauer, 2014).

Drawn in part from poststructuralist and queer theory, the concept of resistance is central in the quest to understand BDSM. Although permeated and constructed by power relations, each person is positioned at the intersection of external forces (discourses) and hence constitutes “a point of potential resistance” (Rose & Miller, 1992, p. 190). Public health workers are accustomed to such resistance points. According to Deleuze and Guattari (1972), the “sexual” body is a site where “libidinal forces” struggle against external social forces. For them, social norms (which are part of governing strategies) attempt to exercise their power by marking (mapping) and shaping bodies. For example, at the very moment that (public) health imperatives are marking the body and compelling it to obey, the body is being fed by desires that continuously disrupt the protocol of the “body map makers” (e.g., public health authorities) (Patton, 2000). BDSM practitioners, who were once stratified (normalized) selves, are in Deleuze and Guattari’s terms turned into war-machines (they resist), then become deterritorialized (they free themselves) by the very nature of their degenitalizing sexual practices. BDSM practitioners continue to chart new socio-sexual territory while resisting the violence of a political system known as heterosexuality (Witting, 1992).

Deleuze and Guattari (1972, 1987) provide a useful theoretical – and indeed, politicizing – framework to analyze the ways in which discourses give rise to subjectivities. The resisting subject placed in opposition to social order or institutionalized norms is one form of subjectivity. Individuals affirm their own nature and ethics through specific practices (e.g., BDSM) and ways of being within those practices (e.g., safe or unsafe sexual activities) (Deleuze & Parnet, 1987; Patton, 2000). The tension between the modern territorializing system (epitomized by health care, government, and other such institutions) and rebellious individuals is implicit in studies of bareback sex (Holmes & Warner, 2005; Holmes & O’Byrne, 2006; Holmes, O’Byrne, & Gastaldo, 2007; Holmes et al., 2008). Seeing the activities of BDSM practitioners in such a light may not only permit a better understanding of their discourses (and attendant practices), but will help us to rethink the role of the public health system in relation to healthy and unhealthy sexual practices.

In an interview originally published in 1984, Foucault (1997) speaks about the degenitalization of pleasure in relation to BDSM: “The idea that bodily pleasure should always come from sexual pleasure as the root of all our possible pleasure – I think that’s something quite wrong. These practices are insisting that we can produce pleasure with very odd things, very strange parts of our bodies, in very unusual situations, and so on” (p. 165, emphasis in original). The English translation of this text is misleading when it speaks of the “desexualization of pleasure.” “Degenitalization” is more appropriate. As Halperin (1995) explains, “The notion of ‘desexualization’ is a key one for Foucault, and it has been much misunderstood. When he speaks of ‘desexualization,’ Foucault is drawing on the meaning of the French word sexe in the sense of sexual organ” (p. 88). In other words, “S/M detaches sexual pleasure from genital specificity, from localization in or dependence on the genitals” (Halperin, 1995). BDSM is a remapping of the body’s erogenous sites, and a deterritorialization of traditional sexuality, which is focused on the genitals, to reterritorialize other bodily sites, surfaces, and depths, through bondage, fist-fucking, cock and ball torture, piercing, domination and submission, humiliation and veneration. In Halperin’s terms, this represents “a breakup of the erotic monopoly traditionally held by the genitals, and even a re-eroticization of the male genitals as sites of vulnerability instead of as objects of veneration” (Halperin, 1995). It would seem, then, to be a breakup of “straight” penetrative sex, a subversion of traditional power structures and masculine-feminine stereotypes, and an end to the Freudian adage that (genital) biology is destiny. Said another way, BDSM practices seem to promise a subversion of hegemonic categories, including sexual orientation and gender identity, as well as the capitalist structures of (re)production that seek to fix meaning and identity.

For many scholars, Foucault’s discussion on BDSM, read in isolation from his other work, can suggest such utopianism. Foucault says that BDSM’s degenitalization represents “the real creation of new possibilities of pleasure, which people had no idea about previously” (1997, p. 165). If BDSM practices are in dialogue with the “(re)genitalizing” power relations in the hegemonic (heterosexual) culture, Foucault is adamant that BDSM does not simply reproduce a genitalized structure: “I wouldn’t say that it is a reproduction, inside the erotic relationship, of the structures of power,” Foucault says. “It is an acting-out of power structures by a strategic game that is able to give sexual pleasure or bodily pleasure” (1997, p. 169). And in this strategic game, he says, “We have to create new pleasure. And then maybe desire will follow” (Foucault 1997, p. 166). It is tempting to think that new pleasures will somehow escape discursive power structures, and that by engaging in them we might find that we desire them. But when asked if we can be sure that these practices will not themselves be co-opted, exploited, reterritorialized as a means of social control, he responds that this is of course inevitable: “We can never be sure [that it won’t happen]. In fact, we can always be sure it will happen, that everything that has been created or acquired, any ground that has been gained will, at a certain moment be used in such a way” (1997, pp. 165–166, emphasis in original). Here Foucault is consistent with Deleuze and Guattari’s warning about molecular lines and lines of flight, and the potential to become “embedded” in one’s “own black hole” and to “become dangerous in that hole” (Deleuze & Parnet, 1987, pp. 138–139). Erotic pleasures are in perpetual struggle within and against forces of social control, within and against a regime of sexuality that organizes our sex-desire and seduces us into thinking that this desire is natural, that it comes from deep within (Foucault, 1978). Subversive pleasures are always potential and creative, a line of flight in Deleuze and Guattari’s terms, but resistance is never quite an escape, because reterritorialization is always immanent.

It would be naïve to assert that degenitalization amounts to the wholesale deterritorialization of bodies and pleasures; bodies and pleasures are inextricably tied up in all manner of territorialization and reterritorialization. BDSM as such is not always a liberatory practice. If it is true that BDSM resists the disciplinary practices – and prohibitions – of vanilla sex, it does so not by liberating repressed desires or blindly railing against social norms, but by mobilizing counter-productive forces, through invention, as Foucault insists (1997, p. 165). And in this, BDSM is not free from power structures. While the practice of BDSM “depends on mutual respect generally absent from the relations between the powerful and the weak, underprivileged, or enslaved in society,” as Bersani notes, “S/M is nevertheless profoundly conservative in that its imagination of pleasure is almost entirely defined by the dominant culture” (1995, p. 87). If BDSM is framed as play or as a strategic game, in other words, it nevertheless confirms socially operant power structures, however they are reframed or recoded. The reframing is not insignificant, but power and pleasure degenitalized is not necessarily a deterritorialization of the bodies and pleasures that are found in the BDSM scene or, by the same token, in those forces of domination and submission in society more generally, between the powerful and the weak, underprivileged, or enslaved in society. Bersani draws one important distinction: “What S/M does not reproduce is the intentionality supporting the [power] structures in society” (p. 88).

Much like Foucault, Bersani does not suggest that BDSM simply reproduces scenes of social domination, even if BDSM sometimes draws on or pastiches them; rather, he calls our attention to the tensions between them – and on the importance of intentionality, the expression of human agency, that might emerge in this space of difference. What is more, social domination is rarely as explicit as relations within the BDSM scene: “Outside such extreme situations as police- or terrorist-sponsored scenarios of torture,” he argues apropos social domination, “this configuration is, in the modern world, seldom visible in the archaic form of face-to-face relations of command and violation. Power in civilized societies has become systemic, mediated through economy, law, morality” (p. 89). We might add public health and clinic practice to these mediations – bodies organized, surveyed, and policed by despotic-(State)-machines in ways that are not quite face-to-face relations of command and violation, because these socio-strategic relations have “been stabilized through institutions” (Foucault, 1997, p. 169). In other words, social forms of dominance – between the powerful and the weak, underprivileged, or enslaved in society – are subtle and diffuse and capillary; their institutions are normalizing and regularizing. By contrast, BDSM relations, despite their rituals and institutions, reflect an ethic of the face-to-face encounter, and for this reason are in some respects easier to see and certainly easier to target and to vilify, if not to scapegoat. For Bersani, this means that BDSM is a privileged site of sorts: “It is a kind of X-ray of power’s body, a laboratory testing the erotic potential in the most oppressive social structures” (1995, p. 98). Bersani effects something of a reversal: rather than judge BDSM through the lens of normative social structures – economy, law, morality, or health – he asks us to read these social systems, and to analyze their power relations, through the lens of BDSM. This upsets the dominant terms by which we might judge a practice to be “liberatory,” on the one hand, or the “captivation” of bad faith, on the other.

If we were to submit our own research to such a critique, we might confess that there is something ironic in the way we have structured this chapter. On its surface, it obeys a recognizably “molar” form of scholarship, according to the usual “segmentary” lines of the discipline: Introduction, Theoretical Framework, Results, and Discussion, although we have decided to forego a discrete and autocratic Conclusion to offer instead something distinctly self-reflexive, and to consider our own practices as writers and researchers. The molar or “segmentary” form of this chapter offers readers a familiar way into a world that may be unfamiliar, though the form of this chapter is belied, provocatively we hope, by its molecular content – words and micropractices and scenes drawn directly from our participants, speaking to and from their particular bodies and pleasures. Our personal reflection is in some small way a line of flight, a departure from as much as a deference to the molar and molecular lines – and fostering, we hope, our readers’ own lines of flight, to reflect on their own practices. These practices may comprise programs of research or clinical practice, a world far from BDSM, but in some ways we might also discern in this work our own economies of desire, those bodies and pleasures that form assemblages with our own words, clinical micropractices, and scholarly scenes. Qualitative work such as this is necessarily performative: at a certain moment it enacts – in some sense – what it describes, and it does what it says. If we do not simply reproduce obvious forms of social domination, to what extent might we nevertheless participate in powers that are subtle and diffuse and capillary, through institutions that are normalizing and regularizing, and in this sense find ourselves complicit with a structural violence that promises liberation but whose captivations are difficult to see?

As Bersani (1995) suggests: “This could be the beginning of an important new political critique, one that would take intractability into account in its rethinking and remodeling of social institutions” (p. 90). Our study here opens researchers and practitioners onto a rich field of study into BDSM, and invites the exploration of its power relations, mindful of the ways that this exploration itself is a power relation. It would be insufficient here simply to bring theory to bear on empirical research, as a heuristic, a way into the lives and practices of research subjects. Such an approach is not in itself deterritorializing, and fails to take account of the intractability of our own theoretical prejudice – embodied, acted-out, and performed, knowingly or in most cases unknowingly – and enshrined if not ossified in our social institutions. Research therefore must remain open to new subjectivities, new potentialities, with the understanding that research, too, is an assemblage, a machine, and sometimes – at its best – a war-machine that can be turned back on itself to critically destabilize the kinds of relations we have to ourselves, as scholars and clinicians. As Foucault (1997) writes of BDSM, “the relationships we have to have with ourselves are not ones of identity, rather, they must be relationships of differentiation, of creation, of innovation” (p. 166).

Antonioli, M. (2003). Géophilosophie de Deleuze et Guattari. Paris: L’Harmattan.

Bauer, R. (2014). Queer BDSM Intimacies. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Bersani, L. (1995). Homos. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Deleuze, G. & Guattari, F. (1987). A Thousand Plateaus. New York: Continuum.

Deleuze, G. & Guattari, F. (1986). Nomadology: The War-Machine. New York: Semiotext(e).

Deleuze, G. & Guattari, F. (1972). Anti-Oedipe. Paris: Editions de Minuit.

Deleuze, G. & Parnet, C. (1987). Dialogues II. New York: University of Columbia Press.

Federman, C. & Holmes, D. (2000). Caring to death: Health care professionals and capital punishment. Punishment and Society, 2(4), 439–449.

Foucault, M. (1997). Sex, power, and the politics of identity. In P. Rabinow (Ed.). Ethics: Subjectivity and Truth, Essential Works of Foucault, 1954–1984, Vol. 1 (pp. 163–173). New York: The New Press.

Foucault, M. (1978). History of Sexuality: An Introduction. New York: Pantheon.

Halperin, D. (1995). Saint Foucault: Towards a Gay Hagiography. New York: Oxford University Press.

Hocquenghem, G. (1993). Homosexual Desire, with a Preface by Jeffrey Weeks. Durham and London: Duke University Press.

Holmes, D. (2002). Police and pastoral power: Governmentality and correctional forensic psychiatric nursing. Nursing Inquiry, 9(2), 84–92.

Holmes, D. & Federman, C. (2003a). Capital crimes. Nursing Inquiry, 10(2), 140–141.

Holmes, D. & Federman, C. (2003b). Constructing monsters: Correctional discourse and nursing practice. International Journal of Psychiatric Nursing Research, 8(3), 942–962.

Holmes, D., Gastaldo, D., O’Byrne, P., & Lombardo, A. (2008). Bareback sex: A conflation of risk and masculinity. International Journal of Men’s Health, 7(2), 173–193.

Holmes, D. & O’Byrne, P. (2006). Bareback sex and the law: The difficult issue of HIV status disclosure. Journal of Psychosocial Nursing & Mental Health Services, 44(7), 26–33.

Holmes, D., O’Byrne, P., & Gastaldo, D. (2007). Setting the space for sex: Architecture, desire and health issues in gay bathhouses. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 44(2), 273–284.

Holmes, D. & Warner, D. (2005). The anatomy of a forbidden desire: Men, penetration and semen exchange. Nursing Inquiry, 12(1), 10–20.

Jagose, A. (1996). Queer Theory: An Introduction. New York: NYU Press.

Lupton, D. (1999). Risk. London: Routledge.

Patton, P. (2000). Deleuze and the Political. London: Routledge.

Robinson, A. (2010). In Theory Why Deleuze (Still) Matters: States, War-machines and Radical Transformation. Retrieved from https://ceasefiremagazine.co.uk/in-theory-deleuze-war-machine/ (accessed 15 December 2016).

Rose, N. & Miller, P. (1992). Political power beyond the state: Problematics of government. British Journal of Sociology, 42(2), 173–205.

Wallin, J. (2012). Body without organs (BwO). In R. Shields and M. Vallee (Eds.). Demystifying Deleuze (pp. 37–40). Ottawa: Red Quills Books.

Witting, M. (1992). La Pensée Straight. Paris: Éditions Amsterdam.