THERE ARE TWO QUESTIONS ADDRESSED in this chapter: 1) Where has the United States been in terms of criminal justice policy and 2) where does it stand now? I begin by providing statistical information on changes over time in U.S. correctional policy and practice. I then try to make sense of one of the most extensive policy shifts in U.S. history, focusing on the “whys” and “hows” of the evolution of crime control and the dramatic growth in corrections.

One more thing before I begin. The term “crime control” is used throughout this book to refer to a set of policies and laws that focus on crime reduction primarily through the mechanisms of punishment and control. Crime control, which has characterized federal- and state-level criminal justice policy for four decades, is premised on the assumption or belief that punishment and control will deter and incapacitate. Under this approach, punishment severity is assumed to specifically deter the individual being punished (specific deterrence), and generally deter others (general deterrence), presumably because they observe or are aware of the consequences of offenders’ actions. And correctional control, in the more extreme version of prison and jail and to a lesser extent probation and parole, is assumed to prevent crimes by eliminating or reducing opportunity, thus the term “incapacitation.” In chapter 2 I will address the extent to which punishment and control have reduced crime and recidivism in recent U.S. history.

BY THE NUMBERS

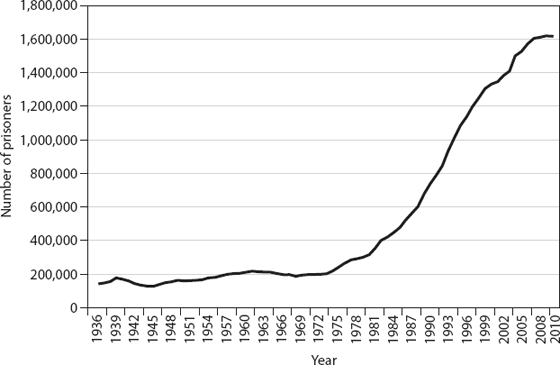

Undoubtedly, the defining characteristic of U.S. criminal justice of the past forty years is the growth in incarceration. The prison population has risen by an extraordinary 535 percent over that period. Figure 1.1 is a visual depiction of the growth in U.S. incarceration reflected by the number of state and federal prisoners between 1936 and 2012 (data are from the Bureau of Justice Statistics, 1988, 2002, and 2012).

FIGURE 1.1 State and Federal Prisoners, 1936–2012

The headlines are all too familiar and are from a wide variety of sources—liberal, conservative, and neutral—including the Washington Post, The Economist, Time Magazine, U.S. News and World Report, CNN, Science, Newsweek, The Atlantic, Business Week, the Wall Street Journal, the National Review, The New York Times, and many, many more.

“1 in 100 Incarcerated”

“America’s Soaring Prison Population”

“Incarceration Nation”

“U.S. Incarceration Highest in the World”

“U.S. Prisons Largest in the World”

“Inmate Count in U.S. Dwarfs Other Nations’”

“U.S. Prison Population Sets New Record”

“Rough Justice: America Locks Up Too Many People, Some for Acts that Should Not Even Be Illegal”

“Prisons: Cruel and Unusual Punishment”

“As Crime Rate Drops, the Prison Rate Rises and the Debate Rages”

“Too Many Laws, Too Many Prisoners: Never in the Civilized World Have So Many Been Locked Up for So Little”

While incarceration gets most of the attention and press, the bigger picture of America’s crime control policy is the expansion of correctional control in general—prison, jail, probation, and parole. Although they vary in the degree of control or loss of liberty, all of the forms of correctional control exploded over the past four decades, which is testament to the ability of the justice systems of the states and the federal government to respond to the call for crime control. This is where I begin.

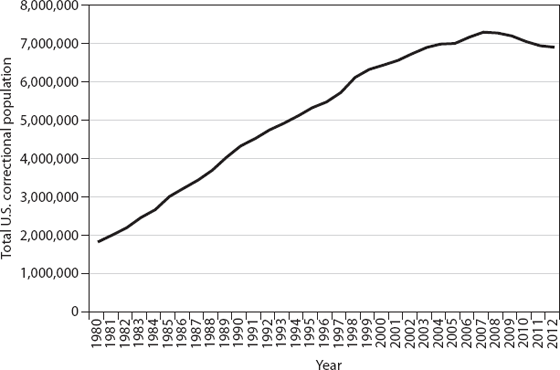

In 1980, there were 1,840,000 individuals in the United States under correctional control or supervision. By the end of 2012, the correctional population had exploded to 6,937,600, representing an increase of 280 percent. The individual components of the correctional explosion increased at unprecedented rates. Between 1975 and 2012, the parole population in the United States increased by nearly 475 percent. Between 1978 and 2012, the local jail population in the United States increased by over 370 percent, from 158,400 to 748,700. Probation populations in the United States increased from 816,500 in 1977 to 4 million in 2012, a growth of 390 percent. Finally, in 1975, there were 240,000 prison inmates in the United States. Over the next thirty-five years, the prison population increased to over 1.5 million, an increase of 535 percent. Figure 1.2 shows the growth in the correctional population over the period from 1980 to 2012 (2012 is the most recent year the data are available; data are from the Bureau of Justice Statistics, Correctional Populations in the United States).

FIGURE 1.2 U.S. Correctional Population, 1980–2012

Trends in correctional spending at the state level correspond to the expansion of incarceration and corrections more broadly. In 1982, states spent $9.7 billion on prison operations; by 2010, that increased to $37.3 billion (these cost figures are inflation-adjusted to 2010 dollars). This change in institutional spending represents a 285 percent increase. Total state corrections expenditures increased from $15.1 billion to $48.5 billion, a 221 percent increase over nearly thirty years.

In terms of sheer numbers, the community supervision population (probation and parole) far exceeds the prison and jail population. In 2013, while there were 2,285,000 individuals in custody in local jails and state and federal prisons, there were nearly 5 million individuals on community supervision (state and federal probation and parole). In addition to the officially counted 6.9 million under correctional control today, there is survey evidence indicating that there are nearly 1 million individuals not counted in the correctional population census. These are individuals that are on conditional release and supervised while on pretrial status, individuals participating in diversion courts and alternative sentencing programs, and other types of diversion (Pew 2009a). Additionally, Pew estimates that there are another 100,000 offenders (not typically counted in official statistics) in prisons in U.S. territories, Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) facilities, and in juvenile programs. Perhaps a more realistic and inclusive estimate of the current correctional population is closer to 8 million.

The correctional boom involved the participation of the federal correctional system as well as the systems of all fifty states and the District of Columbia. However, as the states exercise sovereignty over their individual justice policies and face crime and justice problems at different levels of intensity and concern, as well as different fiscal priorities and constraints, they participated in the correctional boom at differing levels of intensity. Based on yearend 2009 statistics, variation in correctional rates across states is substantial. At the high end: Georgia (1 in 13 individuals is under correctional control); Idaho (1 in 18); Texas (1 in 22); Massachusetts (1 in 24); Ohio (1 in 25); Indiana, Rhode Island, Minnesota, Delaware, and Louisiana (1 in 26); Michigan (1 in 27); and Pennsylvania (1 in 28). At the low end: New Hampshire (1 in 88); Maine (1 in 81); West Virginia (1 in 68); Utah (1 in 64); North Dakota (1 in 63); Iowa (1 in 54); and New York and Kansas (1 in 53).

While there are substantial differences in how and at what level the states participated in the correctional boom, there is uniformity with regard to the impact on various demographic groups. As the Pew Center on the States (2009a) calculates, one in thirty-one individuals in the United States is currently under correctional control. However, this ratio is different for various demographic groups. One in eighty-nine women, but one in eighteen men is under correctional control. One in forty-five whites is under correctional control, compared to one in twenty-seven Hispanics and one in eleven blacks. Drilling down farther, one in three young black males is currently under correctional control. Micro-analyses by the Pew Center demonstrate that correctional control is unsurprisingly concentrated geographically within urban areas, with the highest correctional rates in a small number of urban zip codes and neighborhoods. For example, of the 72,168 offenders released from the Texas prison system in 2008, 30 percent of them returned to seven zip codes in Harris County, Houston, Texas. One in sixty-one residents of Michigan is under correctional control—prison, jail, parole, or felony probation. However, in Wayne County, which is the state’s most populous county, it is one in thirty-eight. In Detroit, which is the largest city in Wayne County, the ratio is one in twenty-five. The East Side of Detroit has a further concentration of offenders (one in twenty-two). Finally, in Brewer Park, an area in the East Side of Detroit, the ratio of residents under correctional control is one in sixteen.

The most often cited trend in the history of U.S. criminal justice is the incarceration boom. For the first three-quarters of the last century (1900 to 1975), U.S. incarceration rates were fairly stable, ranging between 100 and 200 incarcerated individuals per 100,000 Americans. The U.S. incarceration rates were so stable during this seventy-five-year period that most experts predicted continued stability in incarceration for the foreseeable future. However, things changed.

Between 1975 and 2011, the U.S. incarceration rate (jail and prison, state and federal) increased from 165 per 100,000 to 730 per 100,000, amounting to a 345 percent increase. In 1980, U.S. prisons and jails held just over 500,000 inmates. By 2011, the incarcerated population had increased to 2,266,800, a jump of 350 percent. The federal system grew at a greater rate than that of the states. Over the past thirty years, the federal prison system population has increased from 25,000 inmates to nearly 220,000, representing an increase of 790 percent.

Just as is the case with correctional control in general, prison incarceration rates vary considerably by region and by state. In 2012, the aggregate prison incarceration rate among the states was 480. Regional incarceration rates ranged from a high of 551 for the South and a low of 302 in the Northeast. Among states, the range was from a high of 893 (Louisiana) to a low of 145 (Maine). The top five were Louisiana, Mississippi, Alabama, Texas, and Oklahoma. The five lowest were Maine, Minnesota, Rhode Island, New Hampshire, and Massachusetts. Differentials like these were evident throughout much of the corrections boom. For example, in 1994, the state aggregate prison incarceration rate was 367. The South had the highest regional rate (462) and the Northeast the lowest (298). The District of Columbia led the nation (1,935), followed by Texas (637). The states with the lowest prison incarceration rates were North Dakota (84), Maine (119), and Utah (158).

Imprisonment rates differ dramatically by demographic groups. The aggregate (state and federal) prison incarceration rate again was 480 in 2012. However, when broken out by gender, age, and race/ethnicity, there are phenomenal differences. The male incarceration rate is 932; the female is 65. The white male rate is 478; the black male rate is 3,023; the Hispanic male rate is 1,238. Adding age to the breakout, even more striking differences are seen. Young black males are an extraordinarily high-risk group for imprisonment. Black males between ages twenty and forty-four have incarceration rates ranging from 4,702 to 7,517 (again, compared to the overall rate of 502). Black men today have a one in three lifetime likelihood of imprisonment.

There are many ways to place the U.S. expansion of corrections into historical and comparative context. For example, back in the late 1990s and early 2000s, newspaper headlines began to appear to the effect that nearly 50 percent of young black males in cities like Baltimore, Atlanta, and Detroit were involved in the criminal justice system. Or, as the Pew Center on the States has told us, 1 in 100 is incarcerated and 1 in 31 is under correctional control. Or, the United States has 5 percent of the world’s population, but 25 percent of the world’s prison inmates. Or, the United States incarcerates about 400,000 more inmates than the twenty-six largest European nations (with a total population 2.6 times that of the U.S. population).

Perhaps the most compelling statistic is that the United States today has the highest incarceration rate in the world. The 2012 U.S. jail and prison incarceration rate was 716. By way of initial comparison with the U.S rate, the world incarceration rate (if there was such a thing) would be 146/100,000 population. Exemplary incarceration rates for other nations include China (121), Russia (475), Rwanda (492), Australia (130), Kazakhstan (351), Iran (291), Singapore (265), Spain (147), the United Kingdom (153), Germany (79), Japan (58), Saudi Arabia (178), Pakistan (40), Argentina (151), Canada (118), Mexico (200), and South Africa (316) (Walmsley 2011).

Regardless of how it is viewed, these increases in correctional control and the current and recent levels of U.S. incarceration are unprecedented in U.S. history and unprecedented in the history of any other nation for which there are basic data, absent perhaps the Russian Gulag in its heyday. In short, the U.S. correctional boom is a uniquely U.S. experience. The United States has come a long way from Alexis de Tocqueville’s 1831 observation in Democracy in America that “In no country is criminal justice administered with more mildness than in the United States.” I now turn to the “whys” and the “hows” of the correctional boom.

TRACING THE EVOLUTION OF CRIME CONTROL AND THE CORRECTIONAL BOOM

The U.S. correctional boom depended on many factors falling into place. All fifty states participated (to varying degrees), as did the federal justice system. It required massive expansion of prison and jail capacity, increases in probation and parole caseloads, changes to penal codes, changes to sentencing and prison release laws, reorientation of federal, state, and local government funding, and changes in beliefs and attitudes about the causes and prevention of crime, among others. In addition, the political significance of crime control or tough on crime cannot be overestimated.

Barry Goldwater, 1964

The beginnings of the correctional boom in the United States can be traced to Barry Goldwater, the Republican candidate in the 1964 presidential election. Goldwater is credited with putting crime and punishment on the national agenda during his campaign against Lyndon Johnson, and was the first to use the substantial political leverage that crime and punishment provided for future generations of elected officials at the national, state, and local levels. Goldwater, in his speech accepting the Republican nomination for president stated:

The growing menace in our country tonight, to personal safety, to life, to limb and property, in homes, in churches, in playgrounds and places of business, particularly in our great cities, is the mounting concern, or should be, of every thoughtful citizen of the United States. Security from domestic violence, no less than from foreign aggression, is the most elementary and fundamental purpose of any government and a government that cannot fulfill that purpose is one that cannot long command the loyalty of its citizens. History shows us—demonstrates that nothing—nothing prepares the way for tyranny more than the failure of public officials to keep the streets from bullies and marauders.

Lyndon Johnson, 1963–1968

Goldwater lost the election of 1964 to Lyndon Johnson, but the message was clear—crime and public safety had hit the national stage as a central concern. The Johnson administration did address crime and disorder both through communications, such as campaign speeches and State of the Union addresses, and through appointments of study commissions. In communications, Johnson referenced crime as “a sore on the face of America” and a “menace on our streets” (Calder 1982). In 1965, Johnson created the Commission on Law Enforcement and the Administration of Justice, which also included a variety of study panels focusing on new solutions to the problems of public safety, law enforcement, and corrections, among others. The Commission’s findings were presented in early 1967 and Johnson compelled Congress to make the implementation of these recommendations a “matter of the highest priority.”

While Johnson placed crime control high on the list of priorities, as the story plays out, Johnson’s presidency was consumed by Vietnam, a situation made more challenging by the frequent and distracting domestic protests against the administration’s Vietnam policies, as well as massive civil disorder, as race riots swept across the United States, primarily during the summer months of 1965 onward. As Calder (1982) aptly concludes, Johnson suffered a “crisis of confidence,” which significantly contributed to the end of his presidency in 1968 and the end of his crime control initiatives.

The 1960s and Richard Nixon

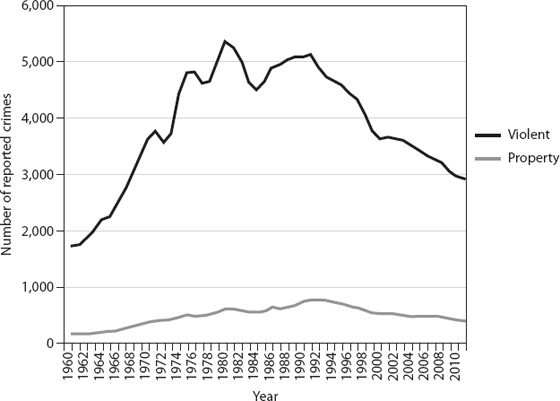

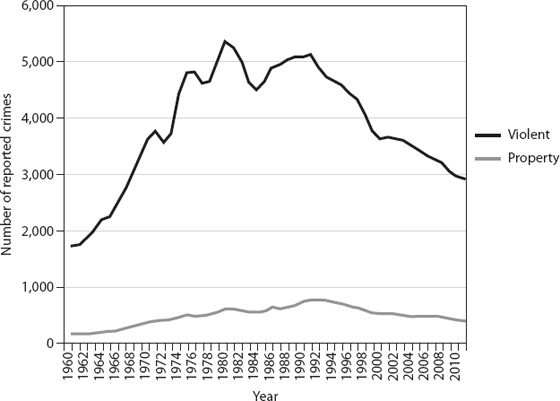

Although Lyndon Johnson declared a war on crime and condemned crime and lawlessness in the streets in his State of the Union speech, it was Richard Nixon who had the “evidence” to really begin to effectively make the crime and punishment link, and to make crime and punishment work politically. Official crime data supported a growing unease regarding predatory crime in U.S. cities. The Uniform Crime Reports (UCR) official crime statistics reflected what the national news media were reporting—crime, especially violent crime, was on the rise. The UCR violent crime rate rose by an unheard of 85 percent between 1960 and 1968 (from 161 in 1960 to 298 in 1968). The robbery rate more than doubled in that eight-year span. The murder rate increased 35 percent, rape was up 65 percent, and aggravated assault had increased by 67 percent. Finally, property crime more than doubled between 1960 and 1968. Figure 1.3 presents the trends in the Uniform Crime Reports violent crime index and property crime index for the period 1960 to 2011 (data from The Disaster Cener, http://www.disastercenter.com/crime).

FIGURE 1.3 Uniform Crime Reports Crime Rates, 1960–2011

This was new in the U.S. experience, and although the average resident is not aware of levels and changes in crime statistics, media coverage of the upswing in crime planted the seeds of public fear that drove much of the political dialog and public policy on crime over the next forty years.

However, it was not just traditional predatory street crime that fueled fear. The 1960s was a decade of tremendous civil upheaval associated with the civil rights movement and the Vietnam War. Beginning in 1965 in Watts, Los Angeles, and continuing through the remainder of the 1960s, essentially every major city and many more, smaller cities experienced massive race-related civil disorders. The list of cities affected includes Newark, Detroit, Chicago, Omaha, Buffalo, Milwaukee, Minneapolis, Baltimore, Louisville, Washington D.C., and Tampa, to name but a few. The scale of these disorders was monumental—hundreds killed, thousands injured, tens of thousands arrested, and billions in property damage. On top of this unrest, there were frequent anti–Vietnam War protests on college campuses around the nation. And, in 1968, Martin Luther King, Jr. was assassinated, spurring another massive wave of violence in urban America. In 1968, Robert Kennedy was also assassinated. Anyone who was paying any attention during the decade of the 1960s likely exhibited some anxiety about the state of disorder, lawlessness, and crime. Every evening, especially during the summers of 1965, 1966, 1967, and 1968, Walter Cronkite reported the extent of the violence to the nation. For the first time since its birth, the United States was experiencing alarming levels of crime and violent disorder in essentially every city in the country.

The 1960s and 1970s also saw the initiation of drug use on college campuses and in urban areas across the United States. In part a function of veterans returning from Vietnam with established patterns of drug use, and in part an attribute of the counterculture movement, the result was increasing drug use and the anxiety and fear associated with it. So concerned was Washington about drug use, in 1971 President Nixon declared drugs “public enemy number one” in launching the War on Drugs.

The ingredients for the launch of crime control can be found in the events of the 1960s. The law and order, crime and punishment, crime control response to these events was simple, logical, intuitive, and proactive. What the United States had been doing in the past to deal with crime and disorder clearly was not working. The evidence was consistent and vivid, in living rooms every evening on the television news. It was time to chart a new course.

What the United States had been doing in the 1940s, 1950s, and 1960s in terms of addressing crime was a somewhat more balanced focus on control and rehabilitation. It was not the case that incarcerated offenders simply spent days in group therapy or in rehabilitation classes. Instead, the focus of penology in the day was that of attempting to change offender behavior through treatment, intervention, rehabilitation, and punishment, while at the same time providing risk management through correctional control.

Correctional rehabilitation was such an important component of justice policy then that it drove the implementation of indeterminate sentencing statutes. In 1975, the federal system and every state system sentenced convicted felons (and misdemeanants) under indeterminate sentencing laws. These statutes were called indeterminate for two reasons. One, the penal code provided for fairly wide ranges of punishment upon conviction of a particular offense or class of offense (for example, first degree felony, class E felony). So the sentence was indeterminate because it was not precisely determined until the sentencing judge imposed the sentence (for example, fifteen years, life, probation). The other and more relevant reason that such sentencing laws were labeled indeterminate is because the actual time served of the sentence imposed was up to the parole authorities, who in theory were to monitor the progress of an inmate’s rehabilitation and determine when the inmate was “better” and could therefore be released. In fact, indeterminate sentencing was a statutory framework that facilitated correctional rehabilitation, based on the simple observation that different individuals, with different experiences and different circumstances, progress at different rates. Therefore, a fixed sentence was not appropriate when the goal was to change behavior.

It is unclear precisely when correctional rehabilitation came into disfavor. Many observers cite the 1974 publication of what has come to be known as the Martinson Report, which concluded that “nothing works” in correctional rehabilitation. It is fair to say that this publication, which represented input from the scientific community regarding the effectiveness of correctional rehabilitation as practiced in the 1940s, 1950s, and 1960s, had a profound negative impact on the future of correctional rehabilitation. However, the wheels of change were already spinning well before the Martinson Report.

What is said of politics is true of crime—it is local. It happens on local streets in local neighborhoods, investigated by local police, prosecuted by local district attorneys, sentenced by local judges, and punished by local (probation, diversion, jail) or state (prison) officials. However, the role of the federal government and federal officials in determining, defining, and establishing criminal justice policy not only at the federal level but at the state and local level is critical in understanding where the United States has been and how and why the United States traveled that road. It is not that the federal government sets state and local policy, but federal initiatives and federal funding certainly influence state and local decision making. I now turn to a brief discussion of the impact and influence of the national administrations that presided over the massive restructuring of America’s criminal justice system. I begin with the 1968 presidential campaign.

The Nixon–Humphrey campaign of 1968 was the platform for Richard Nixon to establish himself as the leader of the crime control initiative by putting law and order squarely on the public agenda. By way of example, a popular Nixon campaign TV ad portrays a middle-aged white woman walking alone at night. The voiceover is by a male who has a quite concerned tone to his voice when he says the following:

Crimes of violence in the United States have almost doubled in recent years. Today a violent crime is committed every sixty seconds, a robbery every two and one half minutes, a mugging every six minutes, a murder every forty-three minutes, and it will get worse unless we take the offensive. Freedom from fear is a basic right of every American. We must restore it.

Then the closing caption reads “This Time Vote Like Your Whole World Depended On It—NIXON.” A number of other Nixon TV campaign ads showed images of student protesters, rioters, burning buildings, street criminals, and victims (all with anxiety-producing music), and then candidate Nixon’s voice stating that it is “time to take an honest look at order in the United States … and so I pledge to you that we shall have order in the United States.”

It appears that the point of the ads is to provoke fear. Nixon’s solution: “Doubling the conviction rate in this country would do more to cure crime in America than quadrupling the funds for Humphrey’s war on poverty.” The language of crime control that evolved focused on arrests, convictions, and narcotics enforcement. The Nixon administration was the first to explicitly place drug use on the national criminal justice radar, linking drug use and property crime. The Nixon administration went several steps further in declaring a War on Drugs in 1971 and established the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) in 1973.

There is evidence that this focus on crime and punishment had substantial political consequences. Beckett and Sasson (2004) offer a credible argument that the Republican crime control initiative was a concerted strategy to sway white southerners. The migration of blacks to the north and northeast, especially during the 1930s, 1940s, and 1950s, while acquiring voting rights, provided a challenge for the Democratic Party to simultaneously maintain the allegiance of southern whites (a traditional ally of the party), as well as the growing block of black voters in the north and northeast. For a variety of reasons, the Democratic strategy led to the focus on northerners and blacks, which left southern whites available to the Republicans. And race played a prominent, though often subtle role in the so-called Republican “southern strategy.” As Beckett and Sasson conclude (2004: 54):

The discourse of “law and order” is an excellent example … of racially charged fears and antagonisms. In the context of increasingly unruly street protests, urban riots, and media reports that the crime rate was rising, the capacity of conservatives to mobilize, shape and express these racial fears and tensions became a particularly important political resource. As the traditional working-class coalition that buttressed the Democratic Party was ruptured along racial lines, race eclipsed class as the organizing principle of American politics.

Whether this impact on white southern voters was deliberate or simply a collateral consequence of crime control policies is less relevant than the fact that it appears to have produced significant political advantage.

Ronald Reagan, 1980–1988

Much of the 1970s were a lot quieter in terms of urban racial violence and Vietnam War protests. While the crime rates continued to rise during the 1970s, the administrations of Gerald Ford and Jimmy Carter reflected a relative lack of attention to crime control in Washington.

Between 1968 (when Nixon assumed the presidency) and 1980 (when Ronald Reagan became president), the violent crime rate doubled and the property crime rate increased by 75 percent. There was still plenty of fuel for the tough on crime agenda. President Reagan launched his own version of crime control, which included a focus on arrest, conviction, incarceration, and drugs, as well as explicitly rejecting socioeconomic or criminogenic explanations of crime. Under Reagan, crime was a choice, and, as a response, crime control and the corrections boom began in earnest. The period 1980 to 1988 saw substantial increases in federal assistance to the states for prison construction, changes in sentencing laws, and closing perceived loop holes in time served (the “truth in sentencing” issue, which targeted the often large gap between sentence imposed and actual time served). This was done by encouraging states to revise sentencing laws by moving away from indeterminate sentencing; imposing more and more mandatory sentences, especially for violent crimes and drug crimes; changing parole statutes and discretionary parole release policies, resulting in inmates serving longer sentences; and the reorientation of federal law enforcement away from white collar crime toward predatory street crime.

The Reagan administration also presided over the passage of the federal Sentencing Reform Act of 1984, which was the legislation that enabled the development and implementation of the Federal Sentencing Guidelines. The federal guidelines that resulted include substantially more severe sentences at the federal level. The Federal Guidelines will be discussed in more depth later in this chapter.

A key element of federal crime control policy has been the focus on illegal drugs, a focus that helped the Reagan administration counter some of the impact of constitutional limits on federal power. The War on Drugs placed the federal government in a key policy role in addressing not only drug crimes, but also the violent and property crimes that were presumed to be associated with drugs.

The Reagan administration faced several significant drug-related challenges in the 1980s, including the 1981–1982 rise of the Medellin cartel (the Columbian cocaine trafficking organization), the 1982 pact between Pablo Escobar, the head of the Medellin cartel, and Manuel Noriega, the president of Panama, allowing cocaine to be transported through his country, and the 1985 crack explosion in New York, which quickly spread to other urban areas. The crack epidemic and the initial violence associated with the distribution and street-level sales of crack rekindled with considerable enthusiasm the antidrug initiatives launched by the Nixon administration. The administration’s responses included the passage of the 1986 Anti-Drug Abuse Act, which provided for mandatory minimum sentences for drug offenses, the Federal Sentencing Guidelines with substantially enhanced sentences for drug law violations, and the Nancy Reagan “Just Say No” campaign.

George H. W. Bush, 1988–1992

It was probably quite obvious even to the casual observer that the 1988 presidential campaign had much to do with crime and punishment. The infamous Willie Horton ad is illustrative of the focus on crime, fear, and punishment. Willie Horton was an inmate in the Massachusetts prison system, and Bush’s opponent in the 1988 presidential campaign was Michael Dukakis, the governor of Massachusetts. As such, Dukakis was perceived as responsible for the furlough program that let Willie Horton out of prison for a weekend and in turn Horton’s failure to return to prison and his subsequent crimes of assault, armed robbery, and rape.

The 1988 campaign further highlighted the political liability of being perceived as soft on crime. George H. W. Bush continued the focus on drugs with the establishment of the Office of National Drug Control Policy and requests for substantial increases in funding for the War on Drugs.

Throughout the decades of the 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s, conservatives essentially owned “tough on crime.” This is not to say that Democrats ignored crime and disorder or were silent on concerns about the problem. Instead, the Democrats were simply outdone by their more conservative counterparts. This was accomplished with a masterful combination of discrediting correctional rehabilitation and the social causes of crime and promoting the intuitive logic of punishment. The problem was crime and disorder, and the solution was simple: punishment deters and incapacitates. If old rehabilitative policies were working, crime rates would not have risen to unprecedented levels during the 1960s and 1970s. It was as simple as that and the electorate got it. Crime control became a wedge issue that provided conservatives tremendous political leverage for decades. Then the political landscape changed in the early 1990s.

Bill Clinton, 1992–2000

The 1992 presidential campaign gave birth to a “new generation” of Democrat (as a Clinton/Gore 1992 TV ad labeled them). Clinton/Gore are “a different kind of Democrat … they don’t think like the old Democrats,” the ad continued. The 1992 presidential campaign attempted to brand Clinton/Gore as tough on crime Democrats in favor of welfare reform, among other issues. The campaign made clear that Clinton/Gore supported the death penalty; they advocated putting more police on the streets. The 1992 campaign even had ex-governor Clinton returning to Arkansas to witness an execution. With a combination of symbolism and substance, Clinton/Gore would change the political control of tough on crime that in turn served to further its momentum.

As the story would unfold, the days of sole Republican ownership of crime control were numbered. Campaign rhetoric aside, the real question was: What did the Clinton administration do to demonstrate the new Democratic brand of crime control? It did not take long. In response to a 1993 House Republican crime control legislative package, the Clinton administration, in collaboration with the Democratic leadership, crafted their own crime control bill that reflected many of the initiatives proposed by the Republicans—federal funding for local law enforcement and for expansion of state prison systems if states adopted “truth in sentencing” legislation (again, referring to changes in laws that require prisoners to serve greater percentages of their sentences before consideration for parole release). The Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act of 1994, with a final allocation of $30.2 billion, provided nearly $14 billion for enhanced law enforcement and nearly $10 billion for the expansion of state prisons. While the longer-term impact of the Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act of 1994 is questionable (Turner et al. 2006), the political impact was clear—crime control or tough on crime became a bipartisan issue.

The post-1994 Clinton/Gore administration saw continued federal involvement in shaping criminal justice policy. The Republican Contract with America was a document that was released during the 1994 midterm Congressional elections and was based considerably on President Reagan’s 1985 State of the Union Address. It was a policy statement on a number of topics including crime and crime control. The Taking Back Our Streets Act, which was a key anticrime bill within the Contract With America, provided for enhanced funding to states for the expansion of prison capacity, as long as states met the truth in sentencing requirements (typically, requiring that violent offenders serve 85 percent of their sentence before parole consideration). Beckett and Sasson (2004) note in their analysis of the Contract with America legislation that the Republican party proposed the elimination of all funding for crime prevention programs, enhancement of the federal death penalty, and imposition of new mandatory minimum sentences. The political importance of crime control is illustrated by the following quote from Beckett and Sasson (2004: 58):

The goals advanced in the Contract With America were subsequently embodied in a series of bills passed easily in the House in February 1995. Although President Clinton and the Democrats did manage to retain separate funds for community policing efforts and the ban on assault weapons, the 1995 legislation largely embodied the get-tough approach to crime and decimated federal support for crime prevention programs. Asked to explain President Clinton’s failure to provide any real alternatives to proposals, one administration official said, “You can’t appear soft on crime when crime hysteria is sweeping the country. …” Since that time, few congressional representatives have been willing to deviate from the bipartisan consensus in favor of “getting tough.”

By the end of Clinton’s second term, crime rates had declined dramatically. The Great American Crime Decline (Zimring 2007), as it has been labeled, consisted of a roughly 40 percent decline in homicide, rape, robbery, burglary, and auto theft between 1990 and 2000, and more modest declines (in the 25 percent range) in aggravated assault and larceny. These UCR trends in crimes known to the police are confirmed by National Crime Victimization Survey data. For a variety of reasons, including declining crime rates, crime and crime control played a less prominent role on the national agenda in the 2000 presidential campaign. Candidate Gore maintained the stance of the Clinton/Gore administration in advocating for more local law enforcement, tougher punishment for offenders (including the death penalty), and mandatory drug testing for all prison inmates and parolees. Candidate Bush maintained support for the death penalty, restrictions on early release from prison, and mandatory sentences, among other crime control initiatives. While both candidates advocated tough on crime positions, aside from mentions in a few speeches and answers to interview questions, crime just was not at the forefront of the campaign as it had been in recent decades.

George W. Bush and the War on Terror, 2000–2008

As governor of Texas, George W. Bush presided over the second-largest prison system in the United States and one of the largest in the world. When Bush took office as Governor, Texas was in the middle of one of the most ambitious prison capacity expansion programs in history, launched by his Democratic predecessor Ann Richards. In a little over six years, the Texas prison system grew by approximately 100,000 beds. During Bush’s term, Texas had the third-highest incarceration rate in the nation (behind the District of Columbia and Louisiana). Clearly, George W. Bush was a tough on crime governor and tough on crime presidential candidate. At the time of the 2000 election, the two major political parties were trying to “out-tough” each other. The Democratic message that was delivered at the 2000 Democratic National Convention was that “Clinton and Gore fought for and won the biggest antidrug budgets in history. … They funded new prison cells and expanded the death penalty for cop killers and terrorists. … But we have just begun to fight the forces of lawlessness and violence.” The Republican message that was delivered at the 2000 Republican National Convention was that “we renew our call for a complete overhaul of the juvenile justice system that will punish juvenile offenders and for no-frills prisons for adults.” Moreover, the popular press continued to support the premises of punishment and crime control (Newsweek November 13, 2000):

The answer seems obvious to most Americans: Yes, of course punishment reduces crime. Punishment converts criminal activity from a paying proposition to a nonpaying proposition, and people respond accordingly. … The logic of deterrence is pretty obvious, and the evidence is powerful too. First, consider the September 18 issue of Forbes, which asks John Lott, senior research scholar at Yale Law School and author of More Guns, Less Crime, “Why the recent drop in crime?” His answer: “Lots of reasons—increases in arrest rates, conviction rates, prison sentence lengths.”

By 2000, the great crime decline of the 1990s was well established and violent and property crime rates were the lowest they had been since the 1970s. Moreover, public fear of crime was at a near historic low. Despite these objective indicators of relative calm, just nine months into President Bush’s first term, September 11, 2001, dramatically changed the landscape regarding anxiety, fear, threat for personal safety, and crime as it was traditionally known.

The September 11 attacks shifted public attention and government efforts and resources toward domestic terrorism and homeland security. Traditional predatory crime rates continued to decline into the decade of the 2000s and fear of crime remained at relatively low levels. Much of the public anxiety and fear associated with the risk of criminal victimization shifted to the new and now more realistic threat of terrorism. That risk was reinforced by the Bush administration time and time again.

Public opinion polls (Pew Research Center for the People and the Press 2011) confirm that while reducing crime was a priority of respondents before September 11, 2001 (76 percent stated that reducing crime was a “top priority,” placing it third behind strengthening the nation’s economy and improving education), reducing crime as a priority dropped considerably after September 11 to 47 percent in 2003, 46 percent in 2009, and 44 percent in 2011. On the other hand, defending against terrorism was the top public priority for the nation for most of the decade after 9/11.

The most significant piece of legislation to come out of the Bush administration regarding predatory crime and crime control was the USA Patriot Act of 2001. The Patriot Act had broad significance for criminal investigation, whether criminal refers to terrorist activity or traditional predatory crime. The Patriot Act in some regards reminds us of Justice Holmes’s argument in Northern Securities Co. v. United States, in which he stated (paraphrasing) that hard cases make bad law. The Patriot Act was passed some forty-five days after the September 11 attacks. David Cole’s (2002) analysis suggests that the scope of the Act was in part a function of the perceived seriousness of the attacks:

The Administration's final line of defense maintains that unprecedented risks warrant an unprecedented response. The availability of weapons of mass destruction, the relative ease of worldwide travel, communication and financial transfers, the willingness of our enemies to give their own lives for their cause and the existence of a conspiracy that would go to the previously unthinkable lengths illustrated on September 11 require a recalibration of the balance between liberty and security.

That recalibration of the balance between liberty and security has resulted in several provisions of the Act having direct application in traditional (that is, nonterrorist) criminal investigations. Those provisions that are most problematic for criminal justice activities include: the expansion of the definition of terrorism, which can be any act involving a weapon or dangerous device that was not committed for personal gain; reduction of judicial oversight in initiating and supervising wiretaps; the expansion of the government’s ability to track internet use and conduct surveillance of libraries and bookstores without probable cause; expansion of the use of sneak and peak searches; and roving wiretaps without probable cause. As Cole (2002) and others opine, the Patriot Act is in many respects an end run around the Fourth Amendment’s protection against unreasonable searches and seizures, as well as the requirement for probable cause as the basis for issuing warrants for lawful searches and seizures.

Barack Obama, 2008–Present

Candidate Obama presented a more balanced approach to crime during the 2007 and 2008 campaign. By balanced, I mean emphasizing tough sanctions for violent offenders, but also providing programs like job training, mental health and substance abuse treatment for ex-offenders; more police, but also resources for stronger families and support for the death penalty, with the recognition that it does not deter; supporting diversion programs; alternative sentencing and rehabilitation; and enhancing reentry programs.

That was candidate Obama. What about President Obama? Until very recently, the Obama administration had not really engaged in much highly visible legislative initiatives regarding crime policy. The president did sign a new federal hate crime bill, and presided over the reduction in the powder-crack cocaine disparity in the federal sentencing guidelines (until it was recently changed to eighteen to one, possession of one gram of crack resulted in the same federal sentence as 100 grams of powder cocaine). On balance, perhaps the best characterization of the Obama administration’s efforts to promote a more balanced crime policy was wait and see. While the Attorney General has announced that the federal government will not pursue marijuana possession cases in Colorado and Washington, the two states that in 2012 legalized possession of personal amounts of marijuana, there seems to be an appreciation for the political risk involved in significant criminal justice policy change. As Doug Berman of Ohio State comments in Politico (Gerstein, September 11, 2010):

Obama wants to do something, I think, big on criminal justice and I think he is absolutely afraid to. Democrats are right to continue to fear tough on crime demagoguery. The lessons of Clinton continue to resonate. … This really is, inevitably, low priority, high risk kind of stuff.

Having said that, there are recent signs (late 2013, early 2014) that the Obama administration may be taking some lead in the area of criminal justice reform. The U.S. Attorney General Eric Holder recently launched the Smart on Crime initiative, aimed at significant changes to sentencing laws and policies, developing alternatives to incarceration for low-level, non-violent offenders, prioritizing prosecution to focus more on serious offenders, and improving reentry from incarceration.

THE MECHANICS OF CRIME CONTROL AND THE CORRECTIONAL BOOM

The “whys” of crime control and the correctional boom are fairly evident based on the historic realities of the 1960s and 1970s—high levels of predatory crime, massive urban civil disorder, Vietnam War protests, increasing illicit drug use, and the conclusion that what the United States had been doing to address crime and disorder was not working. In short, a broad and serious lack of law and order combined with what at the time seemed to be a failed policy. The key ingredients were in place for a radically new approach, one that would define U.S. justice for decades.

I now focus on how all of this was accomplished, beginning with incarceration. Increases in incarceration of the magnitude experienced in the United States were primarily accomplished by expanding prison capacity and correctional control; changing sentencing and release laws and policies; casting a wider net in terms of what types of offenders are incarcerated; and using fear and anxiety to get the public on board for a massive investment in the new policy.

Bricks and Bars

Incarceration capacity has increased dramatically over the past forty years. In 1970, the United States had approximately 580 state-level correctional facilities. By 2005 (the most recent data available for the number of correctional facilities), the states had 1,720, representing a 200 percent increase. In 1970, state correctional facilities in the United States had a capacity for 240,000 inmates. In 2008, the capacity of state facilities in the United States was 1,272,300, a 430 percent increase.

It is important to point out that the state-by-state distribution of the growth in prisons is not uniform and, as expected, most of the growth is lodged in a relatively small number of states. An analysis by the Urban Institute (Lawrence and Travis 2004) demonstrates that nearly two-thirds of the growth in prison capacity occurred in ten states: Texas, California, Florida, Michigan, Georgia, Illinois, New York, Ohio, Colorado, and Missouri. Texas was the outlier among the states, with an increase in the number of facilities over this time period of over 700 percent.

In 1990, 1995, and 2000, state prison systems were operating at an average of 100 percent of rated capacity. By 2005, that had increased to an average of 108 percent, but there was considerable disparity across regions as well as within regions. For example, states in the west averaged 120 percent of capacity, in the Midwest 110 percent, and in the South, 104 percent. However, California was operating at 141 percent, Washington at 131 percent, Florida at 128 percent, Ohio at 122 percent, and Illinois at 136 percent.

The federal prison system also expanded capacity during the corrections boom. Federal data are not very consistent over time, but here is what can be pieced together. Between 1990 and 2005, the capacity of the federal prison system increased from 42,180 to 106,700, an increase of over 150 percent. Interestingly, while several states were in the midst of federal litigation during this era, litigation challenging, among other things, overcrowding of their prison systems, the federal prison system was operating at a level well over its rated capacity. In 1990, the federal prison system was operating at 135 percent of capacity; in 1995, it was 124 percent; in 2000, 134 percent; and in 2005, 137 percent.

Community Supervision Caseloads

The majority of individuals under correctional control are on parole or probation, both of which are supervised release. Probation, defined as conditional supervised release to the community, is diversion from incarceration, but probationers are subject to revocation to prison (for felons on probations) or jail (for misdemeanants on probation) if they violate the conditions of supervision. Parolees, individuals released from prison early, are also subject to revocation to prison if they violate the conditions of their release. Revocation from probation or parole is generally discretionary. In the case of probation, the offender is brought before a judge for a revocation hearing. In the case of parole, the case is brought before the parole authorities, generally a parole board or parole commission.

In 2011, there were 2.75 times as many probationers as prisoners. And while incarceration grew at a faster rate than probation and parole between 1975 and 2011 (incarceration increased by 535 percent, while parole increased by 475 percent and probation increased by 390 percent), the sheer volume of community supervision, primarily probation, required substantial changes as well. One of the primary methods for “expanding” probation and parole during the past three decades to meet increasing supervision demands was simply to increase officer caseloads. The American Probation and Parole Association recommends probation officer caseloads for regular probation supervision of 50. Nationally, the average is somewhere between 130 and 150. In California, one of the largest probation systems in the nation, probation caseloads range from 100 to 200. In Texas, the average caseload is 160. In some jurisdictions in the United States, probation caseloads of 750 to 1,000 have been reported.

While parole caseloads are lower than probation, the parole population is generally higher risk than probation, since parolees have served a period of incarceration. Typical parole caseloads in the United States have increased from forty-five per officer in the 1970s to seventy and higher in more recent years (Travis, Solomon, and Waul 2001). In Texas, state law requires that the maximum parole caseload be sixty. However, the typical Texas parole officer supervised eighty or more parolees in 2010.

Probation and parole caseloads are just one metric for measuring how well community supervision delivers or provides intended risk management and community-based services. What is evident in recent research on probation and parole (DeMichele 2007; Jalbert et al. 2010; Jalbert et al. 2011; Paparozzi and DeMichele 2008) is that community supervision budgets have been steadily declining and caseloads have been steadily increasing.

Available financial data at the state and national levels indicate that criminal justice expenditures increased by over 300 percent between 1988 and 2008. The Pew Center for the States (2009b) estimates that total state-level expenditures for criminal justice in 2008 exceeded $52 billion. The bulk of that—88 percent—was spent on prisons. The irony, as the report points out, is that prisons account for about one-third of the growth in correctional control over the past few decades, but prisons account for the vast majority of criminal justice spending.

Changes to Sentencing Laws and Procedures

Crime control requires punishment, which means punishing more offenders more severely. Thus the strategic issue is how to accomplish that. This is where sentencing reform, an essential mechanism of the crime control strategy, comes into play.

Forty years ago, state and federal criminal defendants were sentenced under indeterminate sentencing laws. Indeterminate sentencing consists of statutes that provide broad authority or discretion to the court in sentencing an individual. The typical indeterminate sentencing statute provides for a relatively wide range of punishment upon conviction of a particular offense (for example, aggravated armed robbery) or class of offense (for example, first degree felony). By way of example, in Texas, a state classified as indeterminate today, the punishment range for someone convicted of a first degree felony is five to ninety-nine years of incarceration or probation (if the offense qualifies for probation). Clearly, a range of five to ninety-nine is considerable and provides the sentencing judge with considerable discretion.

Indeterminate sentencing was called indeterminate primarily because when the offender was admitted to prison, it was unclear (that is, not determined) how long that offender would be incarcerated. How much an offender served of the sentence imposed by the court was up to the parole authorities.

In theory, indeterminate sentencing allows sentencing of the offense and the offender. That is, the court may consider the elements and characteristics of the offense, prior criminal history, and a relatively broad array of mitigating and aggravating circumstances in arriving at an appropriate punishment. The court may sentence for the harm done in the commission of the instant offense, the harm done in the past, and any offender-based aggravating factors that may indicate a harsher sentence, and mitigating factors that may indicate more lenient treatment. Under indeterminate sentencing, the court was generally free to consider a variety of goals of sentencing—specific deterrence, general deterrence, incapacitation, retribution, rehabilitation, something else, and any combination of the above. The court was also generally free to consider, weigh, and evaluate evidence as he/she sees fit. There was no set formula that says: here are the aggravating factors, here are the mitigating factors, and here is a list of the more important and less important considerations for sentencing. In short, judges have substantial discretion in sentencing, and that was historically viewed as an advantage in forging the appropriate sentence for individual offenders. And who better to do that than judges who have the experience in considering the totality of the circumstances and arriving at an offender-based sentence?

And therein lies part of the problem. Sentencing reform was spearheaded by three concerns. One, when judges are allowed such wide latitude in sentencing as that provided by indeterminate sentencing, extralegal factors can enter into the sentencing calculus, which can lead to sentencing disparity and, in the extreme, sentencing discrimination. Disparity has been defined in practice as similarly situated offenders convicted of similar offenses receiving different sentences. Discrimination is the use of clearly unlawful factors, such as race, in the sentencing decision. The second concern, perhaps less frequently articulated but just as present in the crime control/sentencing reform movement, was the perception that when judges are afforded such wide latitude, they tend to “error” on the lenient side of the sentence. Clearly, what is a disparate or lenient sentence is in the eyes of the beholder. Two offenders who appear similar may in fact exhibit relevant differences that the court considers important. What appears lenient to one observer may simply be a case of mitigation.

The third issue is referred to as truth in sentencing. This is also a consequence of indeterminate sentencing and focuses on the gap between the sentence imposed by the court and how much of that sentence the offender actually serves. Indeterminate sentencing was designed to allow offenders to be released when they had progressed to the point at which the parole authorities believed further incarceration was not warranted. Parole release, based on good conduct credit or good time, was also a mechanism prison officials used to manage the prison population—an incentive for good behavior based on the universal currency of those in prison, getting out sooner.

Truth in sentencing essentially means that sentencing should be honest—when the court imposes a sentence of ten years, that means ten years, not two, not five, not seven. What the truth in sentencing advocates promoted was narrowing that gap between what the court says and what actually occurs in terms of time served.

These concerns, disparity/discrimination on one side and leniency of sentence and time served on the other, formed the perfect union. The liberal side of the political aisle embraced the disparity/discrimination concern, and the conservative side embraced the leniency and truth in sentencing concerns. The remedy for both was the same: control or restrict judicial discretion in sentencing. With clear bipartisan support, sentencing reform was launched.

The direction it took was toward determinate or structured sentencing. Determinate sentencing, also called fixed sentencing and including sentencing schemes such as guidelines, is designed to limit judicial discretion by restricting what may be considered by the court at sentencing (the aggravating and mitigating factors common in indeterminate sentencing) and by providing for more specific sentences (rather than wide ranges) for particular offenses.

Several states, including California, Washington, Maine, Minnesota, and Oregon, had begun moving in the determinate sentencing direction in the 1970s and early 1980s. One of the earlier and decidedly more visible and controversial results of sentencing reform were the Federal Sentencing Guidelines.

In 1984, Congress passed the Sentencing Reform Act, legislation drafted in an era of a congressional focus on crime control strategies, including punishment enhancements for narcotics law violations and mandatory minimums for violent offenders. As Stith and Koh note (1993: 259):

The renewed congressional interest in mandating heavy sentences for drug offenses and violent crimes, reflecting Congress’ increasing determination to demonstrate its anticrime sentiment, ultimately resulted in the passage in the 98th Congress of an assortment of statutes imposing minimum terms of imprisonment.

It is important to point out that while the Sentencing Reform Act of 1984 passed both the House and Senate with overwhelming support, there was dissention, especially in the House. Opposition focused on the rigidity and punitiveness of the proposed guidelines, the fact that they were to be mandatory, and that they restricted the court from tailoring sentences to the particulars of individual cases.

The support for this legislation was significantly a function of the fact that it was attached to the continuing appropriations resolution in September 1984. The passage of the Sentencing Reform Act came when the fiscal year was about to end (October 1) and there was an impending national election on November 6, 1984. Both of these considerations played significant roles in the massive overhaul of federal sentencing. Essentially, once the bill was attached to the appropriations bill, it was guaranteed to be enacted, if for no other reason than the immediacy of continuing federal appropriations.

Language in the original legislation and amendments indicate that the Federal Sentencing Commission, which was created by the Sentencing Reform Act, was encouraged to develop mandatory guidelines that enhanced punishment, both across the board, as well as for several targeted segments of the offender population—violent offenders, repeat offenders, drug offenders, and offenders who commit crimes while on bail, among others.

The Federal Guidelines are probably the most drastic version of determinate sentencing in the United States. They are harm based and utilize a quantitative system (effectively, a scorecard) that scores the offense in terms of various measure of harm (physical harm, financial loss, the defendant’s role in the offense, the defendant’s use of a weapon, quantity of drugs, etc.). Most of the traditional offender attributes that judges may have considered mitigating under indeterminate sentencing laws, such as mental health, intellectual capacity, addiction, poverty, and so on, are “not ordinarily relevant” under the federal guidelines. The focus is on the harm reflected in the instant offense (the offense-level score), and the harm perpetrated by the defendant in the past (the criminal history score). The guideline matrix consists of forty-three rows consisting of offense levels, which are statistical scores reflecting the harm done during the commission of the conviction offense. The six columns of the sentencing matrix are composed of scores reflecting criminal history. The matrix has 258 cells, corresponding to the combinations of offense levels and criminal history categories. All but 21 of the 258 cells dictate a sentence of incarceration. Those twenty-one (8 percent of the cells) are subject to diversion on probation. Truth in sentencing issues were quickly resolved by the Commission’s entire and swift elimination of parole in the federal system. The bottom line is that the sentencing role of federal judges was dramatically restricted, most of the opportunities for mitigation were removed, sentences of probation were significantly restricted, sentences are effectively more severe, and time served is greatly increased by the elimination of parole.

The significance of the federal guidelines is not found in the number of individuals sentenced in federal court or in the reach of federal law into sentencing and punishment in the states. The federal system accounts for a small proportion of all individuals sentenced in the United States (approximately 6 percent to 7 percent of felony sentences in a given year in the United States are federal cases). The constitutional limits on the federal government’s authority in local law enforcement, prosecution, sentencing, and punishment highlighted what the Nixon administration saw as a leadership role rather than a direct legislative role for the federal government with regard to crime fighting. The significance of the federal guidelines in terms of U.S. criminal justice policy is the example set. One of the primary goals of the federal sentencing reformers was to create a model for other states to follow (Stith and Koh 1993). And that they did.

The federal system was unique with regard to the sweeping changes the guidelines had on sentencing law, discretion of the court, and the severity of punishment. While no state developed guidelines in the mold of the federal version, the message was clear. In terms of policy, the federal guidelines represented a quite visible standard for the states. The federal government was putting its money where its mouth was in terms of tough on crime. The federal guidelines have been referred to as the “prison guidelines,” a reflection of their overall punitiveness (Hoelter 2009).

The United States went from essentially uniform indeterminate sentencing in all of the states, the District of Columbia, and the federal system prior to 1975, to fifty-two varied, fragmented, hybrid systems of determinate sentences, structured sentences, fixed sentences, guideline sentences, indeterminate sentences, mandatory sentences, mandatory minimum sentences, habitual offender sentences, and elimination of or statutory restrictions on early release. What is clear after sentencing reform is that no state or the federal system in the United States today sentences like it did in 1975, and no two jurisdictions share the same sentencing laws.

It is a bit challenging to classify the sentencing systems in the United States today, mainly because there are no “pure” types. A useful classification by Stemen, Rengifo, and Wilson (2006) is used here to flesh out where states are today after thirty-five years of sentencing reform. Stemen et al. define determinate sentencing as a system that does not have discretionary parole release. Using this definition of determinate sentencing, they classify seventeen states as determinate, meaning the elimination of discretionary parole release. Eighteen states have developed and adopted some form of required or structured sentencing, either in the form of presumptive sentences or presumptive guidelines. Presumptive sentences and guidelines are presumptive because there is the expectation or requirement that the recommended sentence or the guideline sentence will be used, unless there is proper cause and written justification for a departure. An additional eight states had voluntary sentencing guidelines in 2002. What these statutory changes mean in effect is that thirty-five states removed discretion from the court and/or from the parole authorities (seventeen determinate states and eighteen structured/guideline sentence states). Ten states eliminated discretionary parole release and implemented structured sentencing or presumptive guideline sentencing. Twenty-seven states neither eliminated discretionary parole release nor created guidelines or structured sentencing, rendering their sentencing systems discretionary on the part of the court for upfront sentences, and discretionary on the part of the parole authority at release. And while they still, strictly speaking, have discretionary parole, many of these states have altered the statutes governing eligibility for discretionary release (requiring longer percentages of sentences be served before eligibility) and have altered discretionary release decision policies regarding who and how many are released.

While those twenty-seven states did not implement guidelines or dramatically restrict the discretion of the court in sentencing, it is nevertheless the case that those states do not have the sentencing systems they had in 1975. Twenty-three of those states enacted mandatory minimum sentences for a variety of drug law violations; fifteen have mandatory minimums for weapons offenses, nine have them for habitual offenders, nine for certain violent offenders, and nine for sex offenses and/or pornography.

In addition to those states just mentioned, approximately thirty states have or had mandatory minimum sentences for drug offenses, twenty-five had mandatory minimums for crimes involving a weapon, eighteen had mandatory minimums for habitual offenders, seventeen for violent, and eighteen for sex/pornography offenses. The federal government has mandatory minimum sentences for weapons offenses, drug offenses, habitual offenders, and organized crime, among others.

One more matter needs to be addressed while discussing sentencing reform and that is truth in sentencing (TIS) legislation. TIS involves a variety of statutes and sentencing practices all aimed at increasing time served at least for certain types of offenders. One of the provisions of the 1994 Crime Act was the availability of federal grant money to states that implemented TIS provisions. The grant money was designed to fund prison expansion in the states for the incarceration of violent offenders. One requirement attached to the funds was the implementation of truth in sentencing laws.

All told, forty-one states plus the District of Columbia passed some form of TIS law. While twenty-one states had a TIS law in place prior to the passage of the 1994 Crime Bill, twenty-one states either implemented new laws or made at least modest changes to TIS laws. Nine of these states implemented new TIS legislation after 1994. Twenty-nine states implemented the 85 percent rule, requiring that violent offenders serve at least 85 percent of the sentence imposed. The remaining twelve TIS states that did not impose the 85 percent rule did impose a percentage (less than the 85 percent) requirement for time served prior to eligibility for release consideration (data are from Sabol et al. 2002).

The end result is that state legislatures and Congress increasingly took control of sentencing and release decisions, and across the board, this translated into more severe punishments for increasing numbers of offenders. It resulted in more sentences of incarceration (admissions to prison), with longer sentences imposed, and greater time served. These results of sentencing reform provide one of the key mechanisms for accomplishing the incarceration boom.

Drug Control Policy: Casting the Net More Widely

The scale of the correctional boom, in terms of the rate of growth in incarceration and probation and the resulting size of the incarceration and probation populations, was additionally and significantly aided by net widening. Net widening refers to expanding the population of individuals coming in the front door of the criminal justice system. The War on Drugs did just that. The enhanced focus on enforcement of drug law violations, in conjunction with changes in drug sentencing laws, provided a new and growing segment of offenders for the correctional system. Caplow and Simon (1999:71) suggest that there were simply too few nondrug offenders to fuel a correctional boom on the scale that was experienced.

“Tough on crime” policies produce prison population increases only to the degree that offenders are available to be imprisoned. The growth in nondrug crime has simply not been sufficient to sustain the rapid growth in imprisonment.

The logic is twofold. First, drug offenses have been subject to a wide variety of state and federal enhancements in the form of mandatory minimums, mandatory sentences, and repeat offender statutes. These mandatory sentences increase admissions to prison as well as length of sentence and time served. All three of these components—increases in admissions, length of sentence, and time served—will increase incarceration rates and prison populations. The second element in the argument is that drug offenses, to a greater extent than violent and property offenses, are capable of providing a nearly inexhaustible supply of offenders. This is true in part because of the voracious demand for drugs in the United States, the enormous profit to be made, and an ever-present supply of drugs. Moreover, when a drug dealer is arrested, the dealing is not typically removed from the street just because that dealer is in custody. There is usually an eager cohort of replacements ready to fill that vacancy.

So what is the evidence regarding the extent of the role of the War on Drugs in facilitating the correctional boom? Between 1975 and 2002, the number of drug offenders incarcerated in state and federal prisons and jails rose from 40,595 to 480,519, an increase of 1,083 percent! The overall incarceration population increased by slightly more than 400 percent over this period. If drug offender admissions were no different than other offenders, one would expect the increase in drug offenders incarcerated to be somewhere around 400 percent. Instead the increase in incarceration of drug offenders was 2.7 times that of the overall incarceration population. The increase in drug offenders in state prisons and jails was 1,140 percent between 1975 and 2002; for federal prisons and jails, the increase was 1,030 percent.

In addition to this descriptive evidence, research by Stemen, Rengifo, and Wilson (2006) supports this link between incarceration and the War on Drugs. Their analysis demonstrates that the effects of drug arrests likely outstrip the negative effects of declining crime rates on incarceration rates. During the past twenty years, a period in which crime rates declined by 42 percent, incarceration rates increased by 66 percent. Drug incarcerations contributed substantially to the increase in incarceration rates during a period of declining overall crime. Drug offenders have also comprised a significant proportion of individuals sentenced to probation in the United States. In 1990, drug offenders constituted 36 percent of the probation population. In 2000, it was 24 percent, and in 2011 it was 26 percent.

One final point on the issue of incarceration and drugs merits emphasizing. Some observers may inject a conspiratorial element into this argument, suggesting that the War on Drugs was launched to help maintain such large-scale incarceration. The position here is not a conspiratorial one. Instead, the correctional boom and the War on Drugs both occurred within the context of crime control policies and the extent to which drug offending helped support the scale of the incarceration and corrections boom is important, but largely a collateral consequence.

PUBLIC OPINION ABOUT CRIME: THE ROLE OF THE EXECUTIVE AND LEGISLATIVE BRANCHES

The launch and longer-term sustainability of crime control, sentencing reform, and the correctional boom warrant an assessment of the role of public opinion. It is no mistake that public opinion is placed here under the heading of the mechanics of crime control, rather than under the prior section on the drivers of these policies. The evidence does not really support a conclusion that crime control policies were a response to a groundswell of public pressure about crime.

Public opinion polls have tracked a variety of measures including fear of crime and crime as a significant problem, whether crime seems to be increasing or decreasing in their area. For example, one of the more common metrics of crime as a problem is the Most Important Problem (MIP) question, which has been asked annually since 1945. It simply asks: “What is the most important problem facing this nation today?” The MIP question presumably takes more of a national focus (the most important problem facing the nation today) and does not define what it is about crime that is the problem or concern. Fear of crime is also tracked over time and is based on questions like: “Is there any area near where you live—that is, within one mile—where you would be afraid to walk alone at night?” This question has a local focus and asks about personal concerns about safety.

The trends indicate that crime as the MIP was essentially off of the public radar until the late 1960s and 1970s. There was a slight increase in the percentage of respondents indicating that crime was their top priority in 1968 and that continued until 1977. In relative terms, however, these percentages (10 percent to a high of 17 percent) are small. However, in 1988, crime as the MIP jumped to 40 percent, likely in part a response to the violence associated with crack markets as well as the 1988 presidential campaign and influences such as the George H. W. Bush campaign’s Willie Horton TV ad. Crime as the MIP quickly dropped in 1989–1990, but then peaked in 1994 at 52 percent. Crime continued to be at the top of the list of the most important problem facing the nation in 1995, 1997, 1998, and 1999. Beginning in the early 2000s, crime once again slipped off of the public radar (MIP data are from Gallup, various years).

The fear of crime time series is relatively stable over time. Fear, as measured by the “walking alone at night” question, was highest in 1982 with 48 percent affirming such fear and lowest in 1967 at 31 percent (Bureau of Justice Statistics 2010). Over the long term (1965 to 2011), the trend reflects a bump in fear between 1972 and 1993, but between 1994 and 2011 it is essentially stable, fluctuating around an average of 35 percent.

Another measure is whether respondents believe that there is more or less crime in their area than a year ago. Time series data for the period 1972 to 2011 indicate significant fluctuation. Half of respondents in 1972 reported that crime was higher in their area. That was down to 37 percent in 1983, back up to 53 percent in 1989, and 54 percent in 1992, then down to 31 percent in 1998. It remained in the 30 percent to 40 percent range until 2004, then rose and fluctuated between 44 percent and 51 percent up to 2011 (fear of crime and crime increasing data are from the Sourcebook of Criminal Justice Statistics 2011).

This cursory glance at public opinion about crime and fear of crime indicates that the public was sufficiently fearful or concerned about crime to perhaps be “supportive” of a crime control/correctional control initiative. However, there is little evidence in the public opinion data to indicate that the public was growing increasingly and substantially concerned and fearful in the years preceding the launch of crime control or even in the earlier years after crime control was in place.

Political scientists and sociologists have focused on the role of executive, legislative, and political campaign communications in the formation of public opinion about crime. There is a well-established research literature on presidential influence on public opinion (Cohen 1995). An obvious question at this point is: What has been the influence of elected officials and their party platforms in shaping public perception about crime as a problem and crime control as a solution? The research is pretty clear: changes in public opinion about crime and punishment follow public rhetoric by elected officials. That is, the research indicates that the content of national executive, congressional, and party platform speech in turn shapes public opinion, not the other way around. As Bosso (1987: 261) explains:

The presidency is the single most powerful institutional lever for policy breakthrough and is the political system’s thermostat, capable of heating up or cooling down the politics of any single issue or of an entire platter of issues.

Beckett and Sasson (2004: 110–111) assert that public opinion about crime and crime solutions is substantially influenced by political and media discussion/coverage of crime, not the reverse: