Chapter 14

Keeping ’em Sweet: Engaging Your Stakeholders

In This Chapter

Defining a stakeholder

Defining a stakeholder

Understanding your stakeholders

Understanding your stakeholders

Connecting with stakeholders

Connecting with stakeholders

Reassuring stakeholders

Reassuring stakeholders

A programme can have a diverse range of stakeholders. Particularly in a large programme, or one that involves fundamental transformational change, stakeholders are naturally extremely interested in how the programme is going and whether or not it's going to be successful.

In this chapter I help you discover your programme stakeholders and describe the relationship they have with your programme's Vision. Thinking about the Vision allows you to understand who the stakeholders are ‒ including their interests and influence ‒ and then communicate effectively with them. I also discuss the documents and areas of focus for different roles relating to stakeholders.

In addition, I look at assurance, because you need to provide reassurance to the diverse range of stakeholders in a programme. As I note in Chapter 13 on quality, I choose to discuss assurance here rather than there because it's done on behalf of stakeholders. I delve into assurance principles and some of the techniques you can use.

Holding an Identity Parade: Finding Your Stakeholders

Any individual, group or organization that can affect the programme, be affected by it or perceives itself to be affected.

The next section explains why this definition has to be so wide-ranging.

Appreciating different stakeholders

Although you may not have a particular interest in a potential stakeholder group, its members may experience the effects of the programme strongly. In fact, you may not even think that a particular group contains stakeholders, but if the members perceive themselves to be such, they are stakeholders. Their perception is the important criterion.

Stakeholders act in all sorts of ways as regards the programme:

- They can support or oppose it.

- They may ultimately gain or lose.

- They may be indifferent to the change.

- They can end up supporting or blocking it.

In addition, certain stakeholders may see only a threat in your programme while others may see an opportunity.

Grouping stakeholders

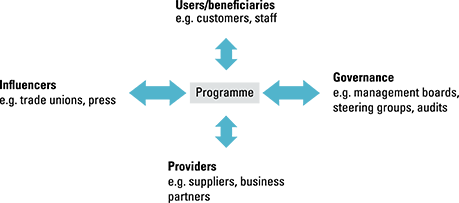

Programme stakeholders can include the groups that I show in Figure 14-1 and list as follows:

- Customers or consumers

- Internal and/or external audit

- Owners, shareholders, management and staff who are sponsoring, affecting or supplying goods or services

- Political interests or regulatory bodies

- Project management teams

- Programme management team including the Sponsoring Group

- Security

- Trade unions

- Wider community

Copyright © AXELOS Limited 2011 Reproduced under licence from AXELOS

Figure 14-1: Possible stakeholder groups in a programme.

Using the Vision to Understand Your Stakeholders

Engaging with stakeholders is one of the ways you help them to change, so it's part of the wider subject of business change management (which I define in the next section). One of the most powerful tools you can use to encourage change in people is to give them a clear Vision of the future (flip to Chapter 5 to find out more about the Vision).

Managing business change

So you're taking the widest possible view of change from the level of the whole organization down to the level of the individual. Figure 14-2 is a simple change process model that's mapped onto processes in the transformational flow. You may find it useful if you want to reflect on when change happens in relation to the transformational flow.

Figure 14-2: A change process model and programme processes.

Bringing stakeholders into the Vision workshop

One of the most important occasions in which you use stakeholder engagement is when you're creating the Vision. Engaging with stakeholders early on in creating the Vision is vital, because doing so ensures joint ownership.

The engagement is best done at the Vision workshop. Make sure that you understand fully the nature of the current situation; the positive and more importantly the negative impact of staying as you are. I suggest considering two ideas:

- Do-nothing Vision: The positive impact of staying put.

- The negative result of staying put is often referred to as a burning platform (or burning bridge): The idea is that if you stay where you are, you burn, so you need to jump off the platform into the river. In other words, it's worth going somewhere else.

An examination of the do-nothing Vision or the burning platform allows you to appreciate the nature of the current reality. From there you can look at the beneficial future. The workshop can explore the tension between the two ideas.

Leading change: Engaging stakeholders

Effective leaders use the Vision to help influence stakeholders. So, for example, Business Change Managers can engage with operational stakeholders to help them through transition.

Understanding the importance of stakeholder engagement

The main aim of stakeholder engagement is to encourage buy-in, by having managed involvement with stakeholders instead of mere ad-hoc involvement. You can expect such buy-in to improve stakeholders’ co-operation and assist with the co-ordination of tasks within the programme and with those outside it.

In addition, stakeholder engagement is an important tool for leaders. The people involved in the programme are going through change and therefore you need strong leadership. Another interesting aspect of good stakeholder engagement is that it helps to avoid unexpected surprises, which stakeholders may think you haven't anticipated (see the nearby sidebar ‘No news is good news’).

If, say, an international regulator takes an interest in a programme and its involvement hasn't been anticipated, stakeholder engagement wasn't working properly.

Stakeholder engagement provides a basis for better communication, because messages are consistent to each stakeholder group. Stakeholder groups talk to one another, so don't give one message to one group and a different message to a different stakeholder group.

Good stakeholder engagement maximises the possibility of good benefits realization.

Engaging and Communicating with Stakeholders

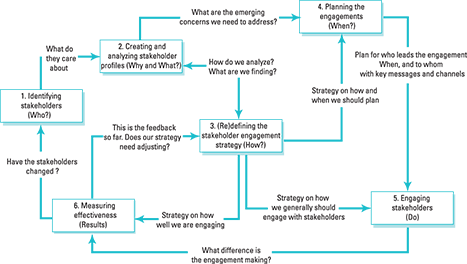

Figure 14-3 displays the stakeholder engagement cycle, which I lead you through in this section. At first sight stakeholder engagement can look like a complex process, but breaking it down helps you to carry it out in a logical way. The perceived complexity is only because of the frequent feedback from one process step to another. If you ignore that feedback for the moment and just look at the purpose of the six process steps, it's pretty straightforward.

In this section I cover each of the steps in the stakeholder engagement cycle.

Modelling your stakeholders

You can do much better than simply engaging with stakeholders on an ad-hoc basis whenever you happen to come across them.

Figure 14-4 is an example of the Stakeholder Map (which happens to be for a sports programme).

Copyright © AXELOS Limited 2011 Reproduced under licence from AXELOS

Figure 14-3: The six process steps in the stakeholder engagement cycle.

Copyright © AXELOS Limited 2011 Reproduced under licence from AXELOS

Figure 14-4: Sports programme Stakeholder Map.

Here's the stakeholder modelling process in a bit more detail:

- Create a simple list of stakeholders, perhaps grouping them as well. The stakeholders can begin to look like a decomposition diagram (a model that shows one thing consisting of several other things below it, for example, the organization diagram for a typical company).

- Identify each stakeholder's areas of interest. In a workshop, people tend to name lots of stakeholders before thinking about their interests.

I suggest that you tackle the Stakeholder Map in a different way. When you've identified one stakeholder group, immediately identify their interest areas. You may have existing interest areas that you discussed before or you may put new interest areas onto your Map. Of course, if you put new interest areas onto the Map, you have to revisit existing stakeholders to see whether those are areas of interest to them as well.

I suggest that you tackle the Stakeholder Map in a different way. When you've identified one stakeholder group, immediately identify their interest areas. You may have existing interest areas that you discussed before or you may put new interest areas onto your Map. Of course, if you put new interest areas onto the Map, you have to revisit existing stakeholders to see whether those are areas of interest to them as well. - Form intersections. If a stakeholder has an interest area, put a cross in the intersection on the Map (take another look at Figure 14-4). If you find yourself putting crosses in all the boxes in a row, you probably haven't done sufficient analysis: if so, break broad interest areas out into more detailed interest areas.

Figure 14-5 shows the Influence/Interest Matrix, which illustrates the interest that stakeholders have in the example sports programme against the influence they have on the programme:

- Interest. The vertical axis is the interest of the stakeholder in the programme. You can think of this as the impact the programme has on the stakeholder: if a programme has more impact the stakeholder is probably going to be more interested in the programme. But I emphasise ‘probably’. Some people may be very interested in the programme, even though you think the programme doesn't impact on them.

- Influence. The horizontal axis is how much influence stakeholders have over the programme. To put it crudely, how much power they have. Again, the relationship may be more subtle. A stakeholder group may have a great deal of power but choose not to use that power in relation to a programme. If they ignore the programme, do they really have influence?

- Banding. In the figure I give some simple examples of different types of interaction with different types of stakeholders. So you simply keep a low interest, low influence stakeholder informed of progress. Whereas a high interest, high influence stakeholder needs to be closely involved in the programme. You need to work very hard at achieving and maintaining strong buy-in.

Copyright © AXELOS Limited 2011 Reproduced under licence from AXELOS

Figure 14-5: Influence/Interest Matrix of a sports-complex programme.

Documenting your decisions

Having enjoyed the delights of the stakeholder identification workshop in the preceding section (oh, what fun you'll have! No really they are quite fun), you need to document what you've decided. I present an overview of the documents and their purposes in Table 14-1. I describe the Influence/Interest Matrix and the Stakeholder Map in the preceding section, Stakeholder Profiles and Stakeholder Engagement Strategy in this one and the Programme Communications Plan in the next.

Table 14-1 Purposes of Stakeholder Documentation

|

Influence/Interest Matrix |

A plot of the influence of stakeholders in your programme against their interest in the programme. |

|

Programme Communications Plan |

Timetable and arrangements for implementing and managing the Stakeholder Engagement Strategy. |

|

Stakeholder Map |

Stakeholders, their interests and areas of the programme that affect them. |

|

Stakeholder Engagement Strategy |

Framework for effective stakeholder engagement. |

|

Stakeholder Profiles |

Records stakeholder analysis information. |

Stakeholder Profiles

In the Stakeholder Profiles you record stakeholder analysis information, including:

- Individual areas of concern

- Influence

- Level of support

- Programme areas interested

- Trends

In a single document you can include the Stakeholder Map and the Influence/Interest Matrix, plus a profile for each stakeholder on the Map. You can also include a distribution of benefits by stakeholder and highlight key influencers. You can summarise all this information in a Stakeholder Register.

Stakeholder Engagement Strategy

The formal purpose of this document is to define the framework that enables effective stakeholder engagement and communication. Informally, people think of it as encapsulating the right message received by the right people, at the right time, in the right form, from the right person, with the right authority.

The document can answer questions such as:

- How will the programme effectively engage with stakeholders?

- What are the key messages?

- Who takes on particular roles?

- How are we going to identify, categorise and group stakeholders?

- Who's responsible for particular stakeholders/stakeholder groups?

- How are we going to manage interfaces between programme and project stakeholders?

- How are we going to process feedback?

Here's the composition of the Stakeholder Engagement Strategy:

- Communications guidelines

- Engagement mechanisms

- How to assess importance and impact

- How to assess analysis

- How to change the Communications Plan

- How projects will interface

- Key message delivery

- Negative publicity

- Policies

- Responsibilities

- Review cycle

- Stakeholder tracking

- Success measures

Communicating with your stakeholders

When you've worked out at a high level how to engage with your stakeholders, you can drill down to the detail of the tasks involved in communication.

The purposes of communication are as follows:

- Raising awareness

- Gaining commitment

- Maintaining consistent messages

- Keeping expectations in line with delivery

- Explaining changes

- Describing the future end state

You want to turn communication into a process that can run in the background in your programme, with the following objectives:

- Keeping awareness and commitment high

- Ensuring that expectations don't drift out of line with what's to be delivered

- Explaining what changes will be made and when

- Describing the desired future state

You need to include the following core elements in your communication process:

- Stakeholder identification and analysis: Sends the right message to the right audience.

- Message clarity and consistency: Ensures relevance and recognition and engenders trust.

- Effective message delivery: Gets the right messages to the right stakeholders in a timely and effective way.

- Feedback collection system: Assesses the effectiveness of the communications process.

Communications Plan

The objectives of the Communications Plan, which put some flesh on the overall purpose of communication, are as follows:

- Raising awareness

- Gaining stakeholder commitment

- Keeping stakeholders informed

- Promoting key message

- Demonstrating and gaining commitment

- Making communications truly two-way

- Ensuring that projects have a common understanding

- Maximising benefits

Composition of the Plan

Consider putting the following information in your Communications Plan:

- A schedule

- The objectives of each communication

- The key messages and information

- The audience for each communication

- The timing of each communication

- The channels you plan to use to communicate

- Responsibilities

- The feedback process

- The estimated effort

- Supporting projects and activities

- Information storage

- Possible stakeholder objections

Communications with projects

The programme needs to control project communications, so the Programme Office may well have to vet all communications. You may decide always to refer certain stakeholders to a specific custodian and perhaps direct certain sensitive topics to the programme each time.

To make this happen, you need to hold regular briefings for projects to keep them involved. You may also need to check that project communications align with the Programme Communications Plan.

Engaging stakeholders: Areas of responsibility

Here are the main areas of responsibility relating to stakeholder engagement. Chapter 9 has lots more detail on these roles.

Senior Responsible Owner

The Senior Responsible Owner (SRO) is responsible for the following:

- Engaging key stakeholders early and at appropriate milestones throughout the programme.

- Leading the engagement with high-impact stakeholders and anticipating stakeholder issues that may arise.

- Briefing the Sponsoring Group and gathering strategic guidance on changing business drivers.

- Showing visible leadership at key communications events and ensuring the visible and demonstrable commitment of the Sponsoring Group.

- Ensuring the creation, implementation and maintenance of the overall Stakeholder Engagement Strategy.

Programme Manager

The Programme Manager is responsible for:

- Developing and implementing the Stakeholder Engagement Strategy.

- Day-to-day implementation of the whole stakeholder engagement process.

- Developing and maintaining the Stakeholder Profiles.

- Controlling and aligning the project communication activities.

- Ensuring effective communications with the project teams.

- Developing, implementing and updating the Communications Plan.

Business Change Manager

Business Change Managers are responsible for the following in their areas:

- Engaging and leading those operating new working practices through the transition, generating confidence and buy-in from those involved.

Active stakeholder engagement is a major part of discharging this role.

- Supporting the SRO and taking specific responsibility for stakeholder engagement in their parts of the organization.

- Supporting the Programme Manager in the development of the Stakeholder Engagement Strategy and Communications Plan.

- Alerting the Programme Manager to the new winners and losers (if any) in their area of changes.

- Providing information and business intelligence for Stakeholder Profiles.

- Briefing and liaising with the Business Change Team.

- Communicating with affected stakeholders to identify new benefits and improved ways of realizing benefits.

- Delivering key communications messages to their business operations.

Programme Office

The Programme Office administers the programme and is responsible for:

- Maintaining information relating to the stakeholders.

- Maintaining an audit trail of communication activity.

- Collating feedback and ensuring that it's logged and processed.

- Facilitating activities specified in the Communications Plan.

Reassuring Your Stakeholders

In this section I tackle the vitally important subject of stakeholder assurance, discussing the principles and techniques and defining some of the terms you need to know along the way.

You may also like to refer to Chapter 13, because assurance is closely linked to quality.

Pondering assurance management principles

Taking a principles-based approach within programme management in general can be helpful, as I discuss in Chapter 4, and you can do the same with assurance management. Assurance means giving stakeholders confidence and reassurance that things are working properly.

The following five principles for guiding your behaviour when carrying out assurance management are a really useful addition to programme management:

- Independence. Assurance needs to have a degree of independence from what's being assured. So, for example, assessors should have no direct line management for the programme team if they're carrying out assurance reviews on the team. Assessors need to be impartial and have no control over project outcomes or service operations. Independent assurance can then be a powerful tool.

- Integration. You need to make sure that assurance is integrated into a programme.

Integrated assurance requires the planning, co-ordination and provision of assurance activities from the start of the programme to the delivery of benefits, in a way that provides greater assurance but with less effort. The Programme Manager's job is to make sure that someone is doing that. You can achieve this through the provision of an agreed plan that indicates how assurance reviews, of all types, are scheduled to support decision-making and inform investment approvals while avoiding duplication of activities that don't add value.

I once carried out an assurance review of a programme and was told that it was something like the fourth assurance review that had been held that month. Project managers weren't spending any time managing their projects; they spent all that time attending a series of overlapping and fragmentary assurance reviews.

I once carried out an assurance review of a programme and was told that it was something like the fourth assurance review that had been held that month. Project managers weren't spending any time managing their projects; they spent all that time attending a series of overlapping and fragmentary assurance reviews. - Linked to major decision points. A key way of achieving value is to link assurance to major decision points.

Plan assurance activity to support major events. Examples are achievement of outcomes, tranche ends and key approval points (for example, funding decisions). These occur throughout the transformational flow, from the Mandate to the realization of benefits.

For example, consider your end-of-tranche reviews. Make sure that you hold an assurance review before the end-of-tranche decision-making, and that the results of that assurance review feed into the end-of-tranche decision-making.

- Risk-based. Assurance needs to be risk-based. Base your assurance activities on an independent risk assessment and make sure that they focus on areas of greatest risks to commercial, legal, regulation, trading, investment and performance requirements. You may also want to look at specialist areas such as financial, delivery, technical, social, political, programme, operational or reputational risks.

Places with more risk require more rigorous assurance; those with less risk need less assurance.

Places with more risk require more rigorous assurance; those with less risk need less assurance. - Action and intervention. Often the assurance reviews work pretty well: they identify what's going and what's gone wrong. The relevant managers receive the reviews… and then they're ignored! Therefore, you need another principle of action and intervention.

Assurance is most effective when appropriate follow-up actions are taken to resolve any serious issues identified as a result of the planned assurance activity. These consequential assurance actions may involve further reviews. Link your reviews of action plans, case conferences or more detailed reviews to ensure that appropriate actions are taken. This process includes clear escalation routes that need to be used if appropriate to the highest organizational levels of the organization for resolution of issues.

In an ideal world, assurance reviewers should only make observations. If they make recommendations for action, they may well be limiting their independence for subsequent assurance reviews. It's convenient if the reviewers also make recommendations. So as part of your planning (as part of your integration of assurance), you need to consider whether you want people carrying out assurance reviews to make observations or recommendations. The most important factor is whether you'll ask the same reviewers to come back and do a subsequent review. In those circumstances, I suggest they just make observations.

In an ideal world, assurance reviewers should only make observations. If they make recommendations for action, they may well be limiting their independence for subsequent assurance reviews. It's convenient if the reviewers also make recommendations. So as part of your planning (as part of your integration of assurance), you need to consider whether you want people carrying out assurance reviews to make observations or recommendations. The most important factor is whether you'll ask the same reviewers to come back and do a subsequent review. In those circumstances, I suggest they just make observations.

Assessing assurance management techniques

In the preceding section I talk about carrying out an assurance review, but that's only one of a number of different techniques you can use when carrying out assurance activities.

Audit

Audit means assessing the management and conduct of a programme and involves examining its activities to see whether the work has been carried out in accordance with an external procedure or standard. In practice, most audits check whether or not you're doing the thing right.

Although audits can be proactive, they tend to be reactive in that they're looking back on the previous performance of an aspect of the programme. Furthermore, audits tend to focus on conformance and compliance: have you done the activity correctly (sometimes known as a validation activity). I'm not criticising the auditing profession (some audits are very comprehensive and wide-ranging), but an audit may, for example, check carefully that you filled in the form without checking that the form makes sense. Therefore, they can be of limited value.

Audits can be carried out by internal audit staff or by external audit bodies. Indeed, anyone can carry out an audit. No particular skills are required in order to carry out an audit, other than some knowledge of the subject matter. Aim to ensure that the range of programme audits consider all aspects of the programme, its management and ability to deliver ‒ although individual audits may cover only one aspect.

Verification and validation

You may come across the following terms on the Internet in the context of audits. I use these generic definitions:

- Verification. Doing the thing right. For example, does the product meet the specification?

- Validation. Doing the right thing. For example, are you building the right product?

Try to aim for a good mix of verification and validation. They can be combined in a single review, or you can ask one group to verify what's happening and another team to validate what's going on.

Health check

A health check means assessing whether a programme is meeting its objectives. The strength and weakness of a health check is that it's a series of yes/no questions. If you answer yes and no to the questions on a health check, you do get a very quick insight into the status or the health of the programme, but you may get only a black-and-white answer with no shades of grey.

Here's a simple sequence for carrying out a health check. You can apply the same sequence to any of the assurance techniques I discuss:

- Prepare by deciding on the scope, selecting and briefing the team members and agreeing how you document the health check.

- Decide on your information requirement, such as which records or process descriptions you look at.

- Undertake the review by reading the various documents and talking to people.

- Analyse the review findings by drawing some conclusions about the health of the programme and putting them in a draft report.

- Agree a corrective action plan between the team that carried out the health check and those who asked for it to be carried out.

- Follow up to make sure the actions have happened.

Assurance reviews

Whereas audits tend to focus on conformance and compliance (or verification) as I say earlier in this section, reviews take a broader look and may be used as a programme assurance tool by senior managers to determine whether the programme continues.

Key areas to consider within an assurance review are based on the elements of quality, scope and the programme management principles (take a look at Figure 14-1 in Chapter 13, which looks a little like a wheel).

Here are some specific areas of focus that often form topics of assurance reviews:

- How well is the programme controlling and enabling its projects?

- Is the level of overhead appropriate?

- How well are the Business Change Managers preparing the organization for changes and are benefits truly being delivered?

- Are the internal processes and governance strategies working effectively and optimally for the purpose of the programme?

Effectiveness of measurement

Effective decisions are based on accurate measurement of data and analysis of reliable information, which is why the Information Management Strategy and Information Management Plan are so important (check out Chapter 13 for more on these).

Therefore, looking at the effectiveness of measurement is another form of assurance. You can consider measurements in a programme in two ways:

- Measurements may be concerned with the management and control of the programme (for example, cost and budget reports).

- Measurement of the programme's outcomes may be a way of assessing whether acceptable benefits are materialising.

P3M3 assessments

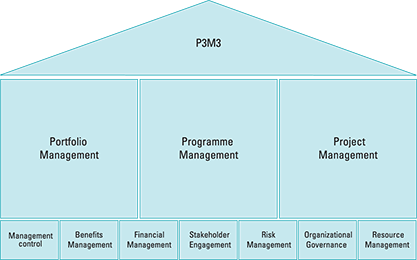

P3M3 stands for Portfolio, Programme and Project Management Maturity Model (I show the model in Figure 14-6). A P3M3 assessment looks at the level of organizational maturity in portfolio, project or programme delivery and has a direct bearing on how well an organization can support its programmes.

Copyright © AXELOS Limited 2011 Reproduced under licence from AXELOS

Figure 14-6: P3M3 model.

A simply way to explain maturity is to talk about repeatability. Within the programme are you able to have repeatable projects (project maturity)? Across the organization are you able to run repeatable programmes (programme maturity)?

- Benefits management

- Financial management

- Management control

- Organizational governance

- Resource management

- Risk management

- Stakeholder engagement

The management and engagement terms will be familiar to you (if not, turn to Chapters 8, 10 or 11 as necessary), so I just put the other two into perspective:

- Management control: Internal control such as plans, monitoring and progress reporting.

- Organizational governance: Sits at a slightly higher level. It's external control, and is perhaps typified by things such as gateway reviews (which I cover in the next section).

The P3M3 model has five levels of maturity:

- Level 1 Awareness: Simply an awareness of the topic under consideration.

- Level 2 Repeatable: Potentially has some repeatability.

- Level 3 Defined: Processes are defined but with some element of flexibility.

- Level 4 Managed: Managed with meaningful metrics.

- Level 5 Optimised: Proactive feedback to improve performance.

Maturity assessments can be big undertakings, which might lead you to call in specialist maturity consultants. I've also simplified the definitions and put my own interpretation on them. In particular, I emphasise flexibility or tailoring more than some writers on the subject.

Note: The P3M3 model is being updated at the time of this writing. I anticipate that another process perspective – commercial or contract management – is likely to be added, but the fundamental concept will be unchanged.

Gated reviews

Gated reviews (sometimes called gate reviews, gateway reviews or independent reviews) are an ideal way of applying assurance control to a programme. The programme isn't allowed to progress to the next stage unless it's undergone a gated review.

Gated reviews check that the programme is under control and on target to meet the organization's needs. They are also applied to projects to ensure that the projects are properly under control and aligned to the programme's Blueprint and the programme objectives.

The decision gates below were originally for a procurement project. These terms may also apply in your programme if a lot of procurement is involved:

- Gateway 0 – Strategic Assessment: Why are we doing this?

- Gateway 1 – Business Justification: Do the costs, benefits, timescales and risks stack up?

- Gateway 2 – Procurement Strategy: Are we buying in the right way?

- Gateway 3 – Investment Decision: Now we've selected a solution, does it still make sense?

- Gateway 4 – Readiness for Service: Is the solution really ready to be used?

- Gateway 5 – Benefits Evaluation: Did we get the benefits we promised?

Before I go any further, I'd like to set out a clear definition of a stakeholder. In the context of a programme, a stakeholder is:

Before I go any further, I'd like to set out a clear definition of a stakeholder. In the context of a programme, a stakeholder is: You may like to pause before reading on and jot down some notes on why you think stakeholder engagement is important. Doing so can be extremely useful later, because a colleague may well ask you this question when you're trying to describe the significance of programme management.

You may like to pause before reading on and jot down some notes on why you think stakeholder engagement is important. Doing so can be extremely useful later, because a colleague may well ask you this question when you're trying to describe the significance of programme management.