A New Way to Pan-Sear Chicken Breasts

Ultimate Pan-Seared Skin-On Chicken Breasts

The Problem with Chicken Stir-Fries

Rescuing Barbecued Chicken Kebabs

Grilled Glazed Chicken Breasts

The Ultimate Crispy Fried Chicken

Best Roast Chicken and Vegetables

Reconstructing Stuffed Roast Chicken

I crave fried chicken as much as the next person, but I have never been partial to fried wings. To me, they’re bar snacks—fine for occasionally sharing with friends but not substantial or satisfying enough to make a meal out of—and certainly not worth the trouble to make at home.

At least, that’s how I felt until I tasted the fried wings at a Korean restaurant. The biggest selling point of this style is its thin, crackly exterior that gives way to juicy meat with an audible crunch—an especially impressive trait considering that the surface of the chicken is doused with a wet sauce. And unlike many styles of wings that are just sweet, salty, or fiery, these delivered a perfect balance of all those flavors.

That profile has made this style of fried chicken wildly popular as an accompaniment to beer and the pickled side dishes known as banchan in South Korean bars and restaurants. In fact, the fried chicken–beer combination is now a multibillion-dollar industry that has spawned the term chimaek (chi for “chicken” and maek for “maekju,” the Korean word for beer), a South Korean festival, and (in the past decade or so) worldwide restaurant chains like Bon Chon that are centered on this particular dish.

A brief rest after twice-frying allows these wings to stay exceptionally crispy, even beneath a layer of sweet-spicy sauce.

Needless to say, I was hooked and was determined to make Korean fried chicken for myself. Once I started to research the recipe, I also learned a practical explanation for using wings: In Korea, where chickens are smaller, restaurants often cut up and fry the whole bird, but because the larger breasts and thighs on American birds are harder to cook evenly, wings are the easier choice. The more I thought about it, I didn’t see why I couldn’t make a meal out of Korean fried chicken wings; their bold flavors would surely pair well with a bowl of rice and (in place of the banchan) a bright, fresh slaw.

THE CRUST OF THE MATTER

Replicating the sauce would be easy enough once I figured out the ingredients. So I first focused on nailing the wings’ delicate but substantial crunch, reviewing the coatings and frying methods I found in a handful of recipes. The coatings varied considerably—from a simple cornstarch dredge to a thick batter made with eggs, flour, and cornstarch—and I found methods for both single frying and double frying. Figuring I’d start with a minimalist approach, I tossed 3 pounds of wings (which would feed at least four people) in cornstarch before frying them once, for about 10 minutes, in a Dutch oven filled with 2 quarts of 350-degree oil.

The meat on these wings was a tad dry, but their worst flaw was the coating—or lack thereof. Most of the cornstarch fell off as soon as the wings hit the oil, so the crust was wimpy—nothing that could stand up to a sauce—and only lightly browned.

Thinking that the starch needed some moisture to help it cling to the chicken, I next tried a series of batter coatings. Not surprisingly, the shaggy mixture of flour, cornstarch, and egg fried up thick and craggy, more like the coating on American fried chicken. I also tried a combination of just cornstarch and water, but it was another bust: Adding enough liquid to make the mixture loose enough to coat the chicken also made it too runny to cling, but without enough water the mixture thickened up like liquid cement. Coating the wings with a creamy, loose slurry of flour and water yielded a nicely thin crust, though it was a bit tough and lacked the elusive shattery texture I was after. From there, I tried various ratios of cornstarch to flour and found that supplementing a flour-based batter with just 3 tablespoons of cornstarch helped the coating crisp up nicely. I understood why once I learned that flour and cornstarch play different but complementary roles in frying: The proteins in wheat flour help the batter bond to the meat and also brown deeply; cornstarch (a pure starch) doesn’t cling or brown as well as flour, but it crisps up nicely. Why? Because pure starch releases more amylose, a starch molecule that fries up supercrispy. Cornstarch also can’t form gluten, so it doesn’t turn tough.

I dunked the wings in the batter and let the excess drip back into the bowl before adding them to the hot oil. When they emerged, I thought I’d finally nailed the crust, which was gorgeously crispy and brown. But when I slathered the wings with my placeholder sauce (a mixture of the spicy-sweet Korean chile-soybean paste gochujang, sugar, garlic, ginger, sesame oil, soy sauce, and a little water) and took a bite, I paused. They’d gone from supercrispy to soggy in minutes.

ON THE DOUBLE

It was a setback that made me wonder if double frying might be worth a try, so I ran the obvious head-to-head test: one batch of wings fried continuously until done versus another fried partway, removed from the oil and allowed to rest briefly, and then fried again until cooked through. After draining them, I would toss both batches in the same amount of sauce to see which one stayed crispier.

It wasn’t even a contest: Whereas the wings that had been fried once and then sauced started to soften up almost instantly, the double-fried batch still delivered real crunch after being doused with the sauce. What’s more, the double-fried wings were juicier than any batch I’d made before. Why? Chicken skin contains a lot of moisture, so producing crispy wings (which have a higher ratio of skin to meat than any other part of the chicken) means removing as much moisture as possible from the chicken skin before the meat overcooks. When you fry just once, the meat finishes cooking before all of the moisture is driven out of the chicken skin, and the remaining moisture migrates to the crust and turns it soggy. Covering the wings with sauce makes the sogginess even worse. But when you fry twice, the interruption of the cooking and the brief cooldown period slow the cooking of the meat; as a result, you can extend the overall cooking time and expel all the moisture from the skin without overcooking the chicken.

There was my proof that double frying was worth the time—and, frankly, it wasn’t the tediously long cooking process I thought it would be. Yes, I had to do the first fry in two batches, for two reasons: The oil temperature would drop too much if I put all the chicken in at once because there would be so much moisture from the skin to cook off; plus, the wet coating would cause the wings to stick together if they were crowded in the pot. But the frying took only about 7 minutes per batch. As the parcooked wings rested on a wire rack, I brought the oil temperature up to 375 degrees. Then, following the lead of one of the more prominent Korean fried chicken recipes I’d found, I dumped all the wings back into the pot at once for the second stage. After another 7 minutes, they were deeply golden and shatteringly crispy. All told, I’d produced 3 pounds of perfectly crispy wings in roughly half an hour. Not bad.

SAVORY, SPICY, SWEET

Back to my placeholder sauce, which was close but a tad sharp from the raw minced garlic and ginger. Instead, I placed the ginger and garlic in a large bowl with a tablespoon of sesame oil and microwaved the mixture for 1 minute, just long enough to take the edge off. Then I whisked in the remaining sauce ingredients. The sweet-savory-spicy balance was pitch-perfect.

Before tossing them in the sauce, I let the wings rest for 2 minutes so the coating could cool and set. When I did add them to the sauce, they were still so crispy that they clunked encouragingly against the sides of the bowl. In fact, the crust’s apparent staying power made me curious to see how long the crunch would last, so I set some wings aside and found that they stayed truly crispy for 2 hours. Impressive—even though I knew they’d be gobbled up long before that.

Korean Fried Chicken Wings

SERVES 4 TO 6 AS A MAIN DISH

A rasp-style grater makes quick work of turning the garlic into a paste. Gochujang, a Korean chile-soybean paste, can be found in Asian markets and in some supermarkets. Tailor the heat level of your wings by adjusting its amount. If you can’t find gochujang, substitute an equal amount of Sriracha sauce and add only 2 tablespoons of water to the sauce. Use a Dutch oven that holds 6 quarts or more. For a complete meal, serve with steamed white rice and a slaw.

1 tablespoon toasted sesame oil

1 teaspoon garlic, minced to paste

1 teaspoon grated fresh ginger

1¾ cups water

3 tablespoons sugar

2–3 tablespoons gochujang

1 tablespoon soy sauce

2 quarts vegetable oil

1 cup all-purpose flour

3 tablespoons cornstarch

3 pounds chicken wings, cut at joints, wingtips discarded

1. Combine sesame oil, garlic, and ginger in large bowl and microwave until mixture is bubbly and garlic and ginger are fragrant but not browned, 40 to 60 seconds. Whisk in ¼ cup water, sugar, gochujang, and soy sauce until smooth; set aside.

2. Heat vegetable oil in large Dutch oven over medium-high heat to 350 degrees. While oil heats, whisk flour, cornstarch, and remaining 1½ cups water in second large bowl until smooth. Set wire rack in rimmed baking sheet and set aside.

3. Place half of wings in batter and stir to coat. Using tongs, remove wings from batter one at a time, allowing any excess batter to drip back into bowl, and add to hot oil. Increase heat to high and cook, stirring occasionally to prevent wings from sticking, until coating is light golden and beginning to crisp, about 7 minutes. (Oil temperature will drop sharply after adding wings.) Transfer wings to prepared rack. Return oil to 350 degrees and repeat with remaining wings. Reduce heat to medium and let second batch of wings rest for 5 minutes.

4. Heat oil to 375 degrees. Carefully return all wings to oil and cook, stirring occasionally, until deep golden brown and very crispy, about 7 minutes. Return wings to rack and let stand for 2 minutes. Transfer wings to reserved sauce and toss until coated. Return wings to rack and let stand for 2 minutes to allow coating to set. Transfer to platter and serve.

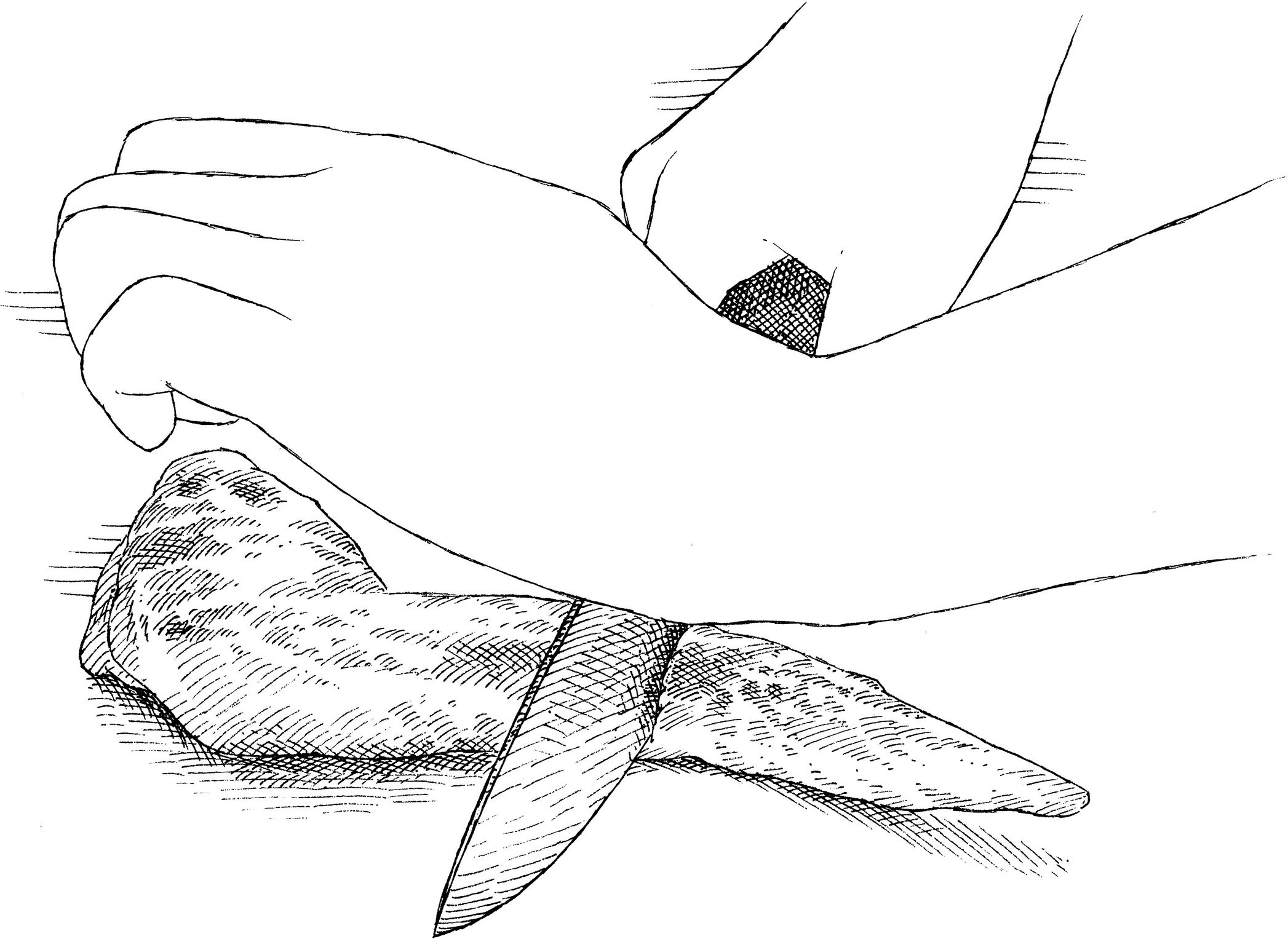

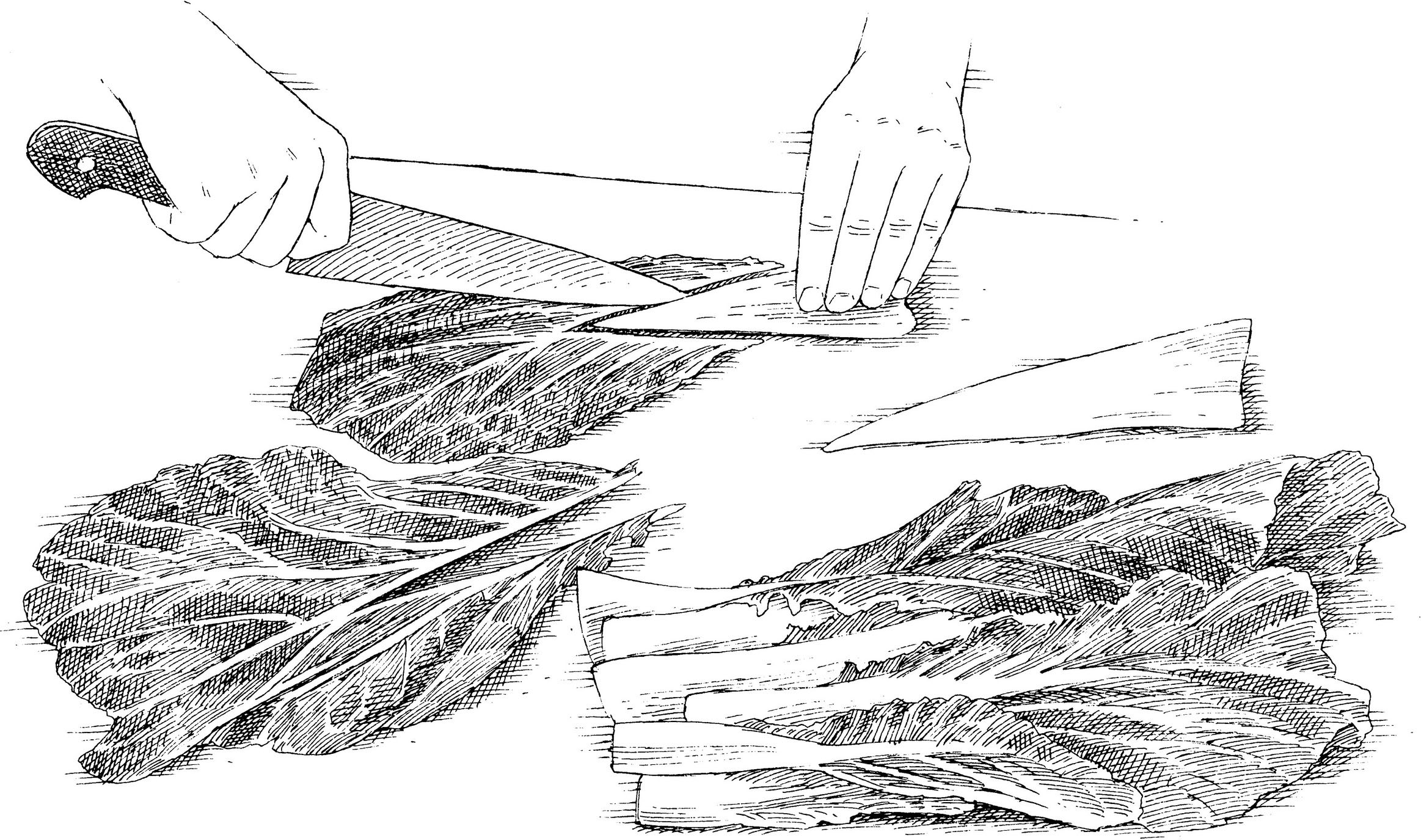

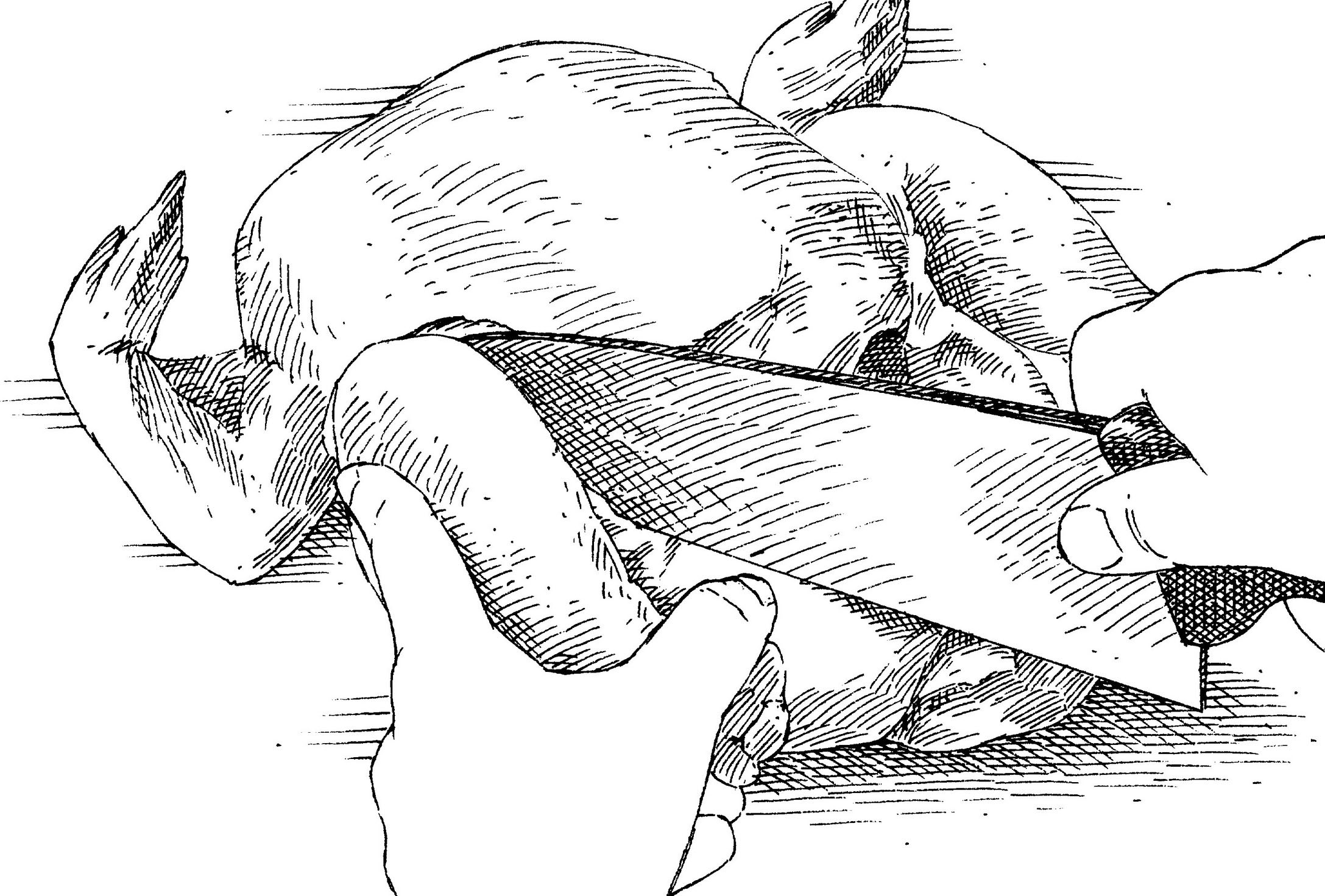

HOW TO CUT UP CHICKEN WINGS

Our recipe for Korean Fried Chicken Wings calls for cutting the wings into three parts: drumettes, midsections, and wingtips. Here’s how to do it.

1. Using your fingertip, locate joint between wingtip and midsection. Place blade of chef’s knife on joint, between bones, and using palm of your nonknife hand, press down on blade to cut through skin and tendon, as shown.

2. Find joint between midsection and drumette and repeat process to cut through skin and joint. Discard wingtip.

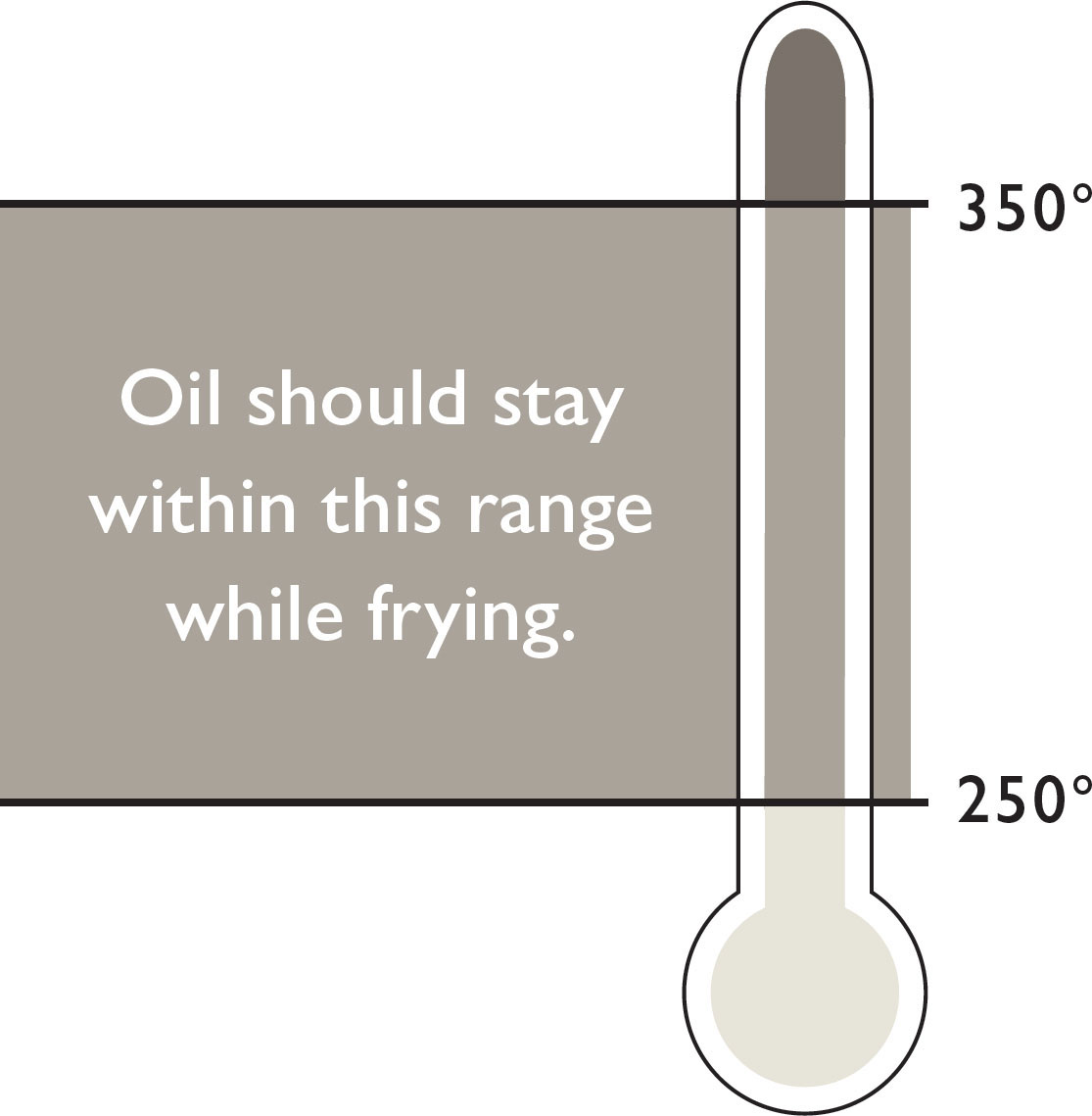

THE IMPORTANCE OF COOKING IN BATCHES

When preparing to fry our wings, we heat the oil to 350 degrees and then cook the wings in batches. We do this because trying to cook the wings all at once (at least for the first fry) would cause the freshly battered wings to stick together; plus, the temperature of the oil would drop too much. Although the temperature will still drop when you add half of the wings, as long as it stays above 250 degrees (where there is enough energy to evaporate water and brown the exterior), the results will be fine.

WINGING IT, KOREAN-STYLE

Korean fried chicken wings boast a big crunch and a complex sauce that make them appealing to eat, but they also employ a relatively quick and easy cooking method that makes them more appealing to prepare than many other styles of fried chicken.

DOUBLE FRYING ISN’T DOUBLE THE WORK

Double frying is crucial for the crunchy texture of our wings because it drives more moisture from the skin—but it’s not as onerous as you might think. Each batch of wings takes just 7 minutes, and the second fry can be done in one large batch.

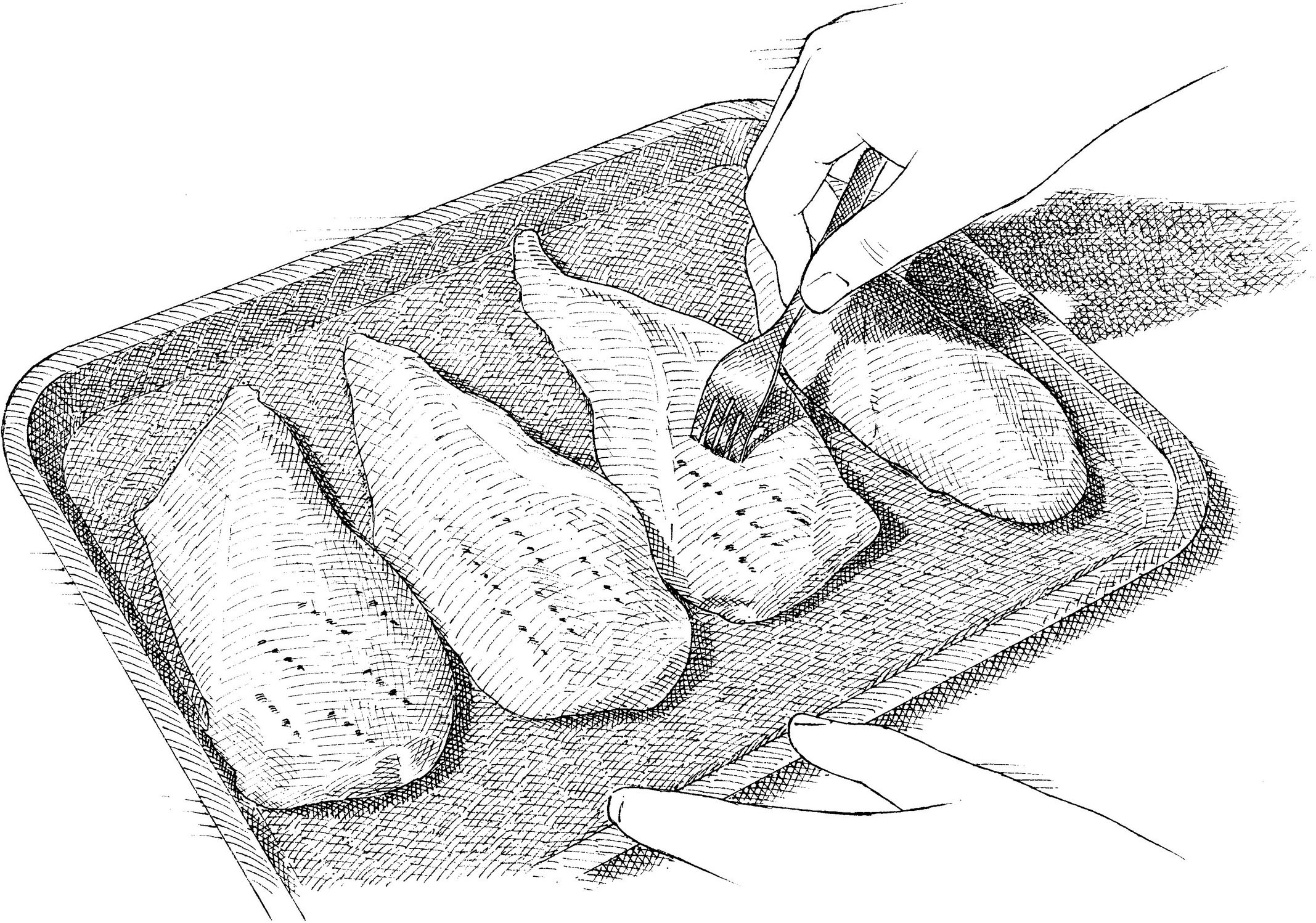

1. Place half of wings in batter and toss to coat. Remove wings from batter one at a time, allowing excess batter to drip back into bowl, and add to hot oil.

2. Increase heat to high and cook, stirring occasionally, until coating is light golden and beginning to crisp, about 7 minutes. Transfer wings to prepared rack and repeat with second batch of wings.

3. Heat oil to 375 degrees, carefully return all wings to oil, and cook, stirring occasionally, until deep golden-brown and very crispy, about 7 minutes. Return to wire rack and let rest for 2 minutes before tossing with sauce.

KEITH DRESSER, March/April 2010

What cook desperate for a quick dinner hasn’t thrown a boneless, skinless chicken breast into a hot pan, keeping fingers crossed for edible results? The fact is, pan-searing is a surefire way to ruin this cut. Unlike a split chicken breast, which has the bone and skin to help keep the meat moist and juicy, a boneless, skinless breast is fully exposed to the intensity of the hot pan. Inevitably, it emerges moist in the middle and dry at the edges, with an exterior that’s leathery and tough. But there’s no denying the appeal of a cut that requires no butchering. What would it take to get a pan-seared boneless, skinless breast every bit as flavorful, moist, and tender as its skin-on counterpart?

SLOW COOKER

I wasn’t the only one to think that the typical sear-cover-and-cook approach needed an overhaul. The problem is that the center of a thick chicken breast takes a long time to reach 165 degrees. Meanwhile, the outer layers are busy overcooking, losing moisture, and turning stringy and tough. One unconventional recipe called for parcooking the chicken in water before searing. In theory, the idea was sound: Poaching would cook the breasts gently and evenly, and the parcooked, warm chicken should take much less time to develop a flavorful brown crust than straight-from-the-fridge meat. Less time in a hot skillet equals less moisture lost. The chicken was juicy and brown, all right—but also flavorless, since much of the chicken’s juices seeped into the cooking liquid and subsequently got poured down the drain.

Moving on, I tried ditching the water bath in lieu of the oven, still keeping the same gently-parcook-then-sear order. I placed four chicken breasts in a baking pan, cooked them in a 275-degree oven until they hit 150 degrees, and then seared them. They browned quickly and beautifully, but while the meat was moist enough on the inside, the exterior had so dehydrated that I practically needed a steak knife to saw through it.

What about salting? Like brining, salting changes the structure of meat proteins, helping them to retain more moisture as they cook. Ideally, chicken should be salted for at least 6 hours to ensure full penetration and juiciness. But boneless, skinless breasts are supposed to be quick and easy, so I wasn’t willing to commit more than 30 extra minutes to the process. I found that poking holes into the meat with a fork created channels for the salt to reach the interior of the chicken, maximizing the short salting time. This made the interior even juicier, but the exterior was still too dried out.

How could I protect the chicken’s exterior from the oven’s dry heat? I tried the exact same method, this time wrapping the baking dish tightly in foil before heating. Bingo! In this enclosed environment, any moisture released by the chicken stayed trapped under the foil, keeping the exterior from drying out without becoming so overtly wet that it couldn’t brown quickly. In fact, this cover-and-cook method proved so effective that I could combine the 30-minute salting step with the roasting step.

TAKE COVER

I now had breasts that were supremely moist and tender on the inside with a flavorful, browned exterior—a big improvement. With a little more effort, could I do better still? To protect thin cutlets from the heat of the pan and encourage faster browning, many recipes dredge them in flour. Raw breasts are malleable, so they make good contact with the pan. The parcooked breasts, on the other hand, had already firmed up slightly, so only some of the flour was able to come in contact with the hot oil in the pan, leading to spotty browning.

Simple dredging was out, and I definitely didn’t want to go the full breading route. The only other thing I could think of was a technique from Chinese cooking called velveting. Here the meat is dipped in a mixture of oil and cornstarch, which provides a thin, protective layer that keeps the protein moist and tender even when exposed to the ultrahigh heat of stir-frying. Though I’d never heard of using this method on large pieces of meat like breasts, I saw no reason it wouldn’t work here. I brushed my parcooked chicken with a mixture of 2 tablespoons melted butter (which would contribute more flavor than oil) and a heaping tablespoon of cornstarch before searing it.

We start cooking boneless chicken breasts in the oven so they need only a brief stint in a hot pan to brown.

As soon as I put the breasts in the pan, I noticed that the slurry helped the chicken make better contact with the hot skillet, and as I flipped the pieces, I was happy to see an even, golden crust. However, tasters reported that the cornstarch was leaving a slightly pasty residue. Replacing it with flour didn’t work; the protein in flour produced a crust that was tough and bready instead of light and crisp. It turned out that achieving the right balance of protein and starch was the key. A mixture of 3 parts flour to 1 part cornstarch created a thin, browned, crisp coating that kept the breast’s exterior as moist as the interior—some tasters thought it was even better than real chicken skin itself.

Served on its own or with a simple pan sauce, this tender, crisp-coated chicken far surpassed any other pan-seared breasts I’ve ever made.

Pan-Seared Chicken Breasts

SERVES 4

For the best results, buy similarly sized chicken breasts. If the breasts have the tenderloin attached, leave it in place and follow the upper range of baking time in step 1. For optimal texture, sear the chicken immediately after removing it from the oven. Serve with Lemon and Chive Pan Sauce recipe follows), if desired.

4 (6- to 8-ounce) boneless, skinless chicken breasts, trimmed

2 teaspoons kosher salt

1 tablespoon vegetable oil

2 tablespoons unsalted butter, melted

1 tablespoon all-purpose flour

1 teaspoon cornstarch

½ teaspoon pepper

1. Adjust oven rack to lower-middle position and heat oven to 275 degrees. Using fork, poke thickest half of breasts 5 or 6 times and sprinkle each with ½ teaspoon salt. Transfer breasts, skinned side down, to 13 by 9-inch baking dish and cover tightly with aluminum foil. Bake until breasts register 145 to 150 degrees, 30 to 40 minutes.

2. Remove chicken from oven; transfer, skinned side up, to paper towel–lined plate; and pat dry with paper towels. Heat oil in 12-inch skillet over medium-high heat until just smoking. While skillet is heating, whisk melted butter, flour, cornstarch, and pepper together in bowl. Lightly brush top of chicken with half of butter mixture. Place chicken in skillet, coated side down, and cook until browned, about 4 minutes. While chicken browns, brush with remaining butter mixture. Flip breasts, reduce heat to medium, and cook until second side is browned and breasts register 160 degrees, 3 to 4 minutes. Transfer breasts to large plate and let rest for 5 minutes before serving.

accompaniment

MAKES ABOUT ¾ CUP

1 shallot, minced

1 teaspoon all-purpose flour

1 cup chicken broth

1 tablespoon lemon juice

1 tablespoon minced fresh chives

1 tablespoon unsalted butter, chilled

Salt and pepper

Add shallot to now-empty skillet and cook over medium heat until softened, about 2 minutes. Add flour and cook, stirring constantly, for 30 seconds. Slowly whisk in broth, scraping up any browned bits. Bring to vigorous simmer and cook until reduced to ¾ cup, 3 to 5 minutes. Stir in any accumulated chicken juices; return to simmer and cook for 30 seconds. Off heat, whisk in lemon juice, chives, and butter. Season with salt and pepper to taste. Pour sauce over chicken and serve immediately.

A PERFECT COATING COMBO

To end up with moist exteriors, our pan-seared boneless, skinless breasts needed light protection. But slurries made with melted butter and the usual suspects—cornstarch and flour—each had issues. Cornstarch is a pure starch prone to forming a gel that left pasty spots on the meat. The proteins in flour, on the other hand, link together to form gluten, leading to an overly tough, bready coating. Using a combination of cornstarch and flour, however, created the perfect light, crisp, evenly browned coating.

The explanation is simple: Each ingredient tempers the effect of the other. With flour in the mix, the cornstarch is sufficiently diluted by protein to prevent it from forming a paste, whereas the protein is diluted enough that it doesn’t cause the crust to become bready.

BETTER BONELESS BREASTS

1. POKE AND SALT Salting chicken seasons meat, keeping it moist. Poking thicker part of breasts ensures even seasoning.

2. COVER AND BAKE BAKING at low temperature in foil-covered dish cooks chicken evenly and keeps exterior from drying out.

3. BRUSH ON COATING Brushing butter, flour, and cornstarch onto breasts creates “skin” to protect meat during searing.

4. SEAR QUICKLY Briefly searing parcooked coated breasts keeps them moist and creates crisp exteriors.

I’m always on the lookout for ways to get great skin on chicken. By that I mean skin that’s paper-thin, deep golden brown, and so well crisped that it crackles when you take a bite. Such perfectly cooked skin, however, is actually a rarity. A good roast chicken may have patches of it, but the rotund shape of the bird means that uneven cooking is inevitable and that some of the skin will also cook up flabby and pale. And even on relatively flat chicken parts, there’s the layer of fat beneath the skin to contend with: By the time it melts away during searing, the exterior often chars and the meat itself overcooks.

When I recently came across one of the best specimens of chicken I’d ever tasted, I had to figure out how to recreate it myself. The restaurant was Maialino (a Danny Meyer venture) in New York City, and the dish was Pollo alla Diavola. The tender meat and the tangy, spicy pickled cherry pepper sauce that was served with it had their own charms, but the chicken skin was incredible—a sheath so gorgeously bronzed and shatteringly crunchy that I’d swear it was deep-fried.

Starting skin-on chicken breasts in a cold pan and weighing them down for part of the cooking time gives them shatteringly crisp skin.

STARTING SMALL(ER)

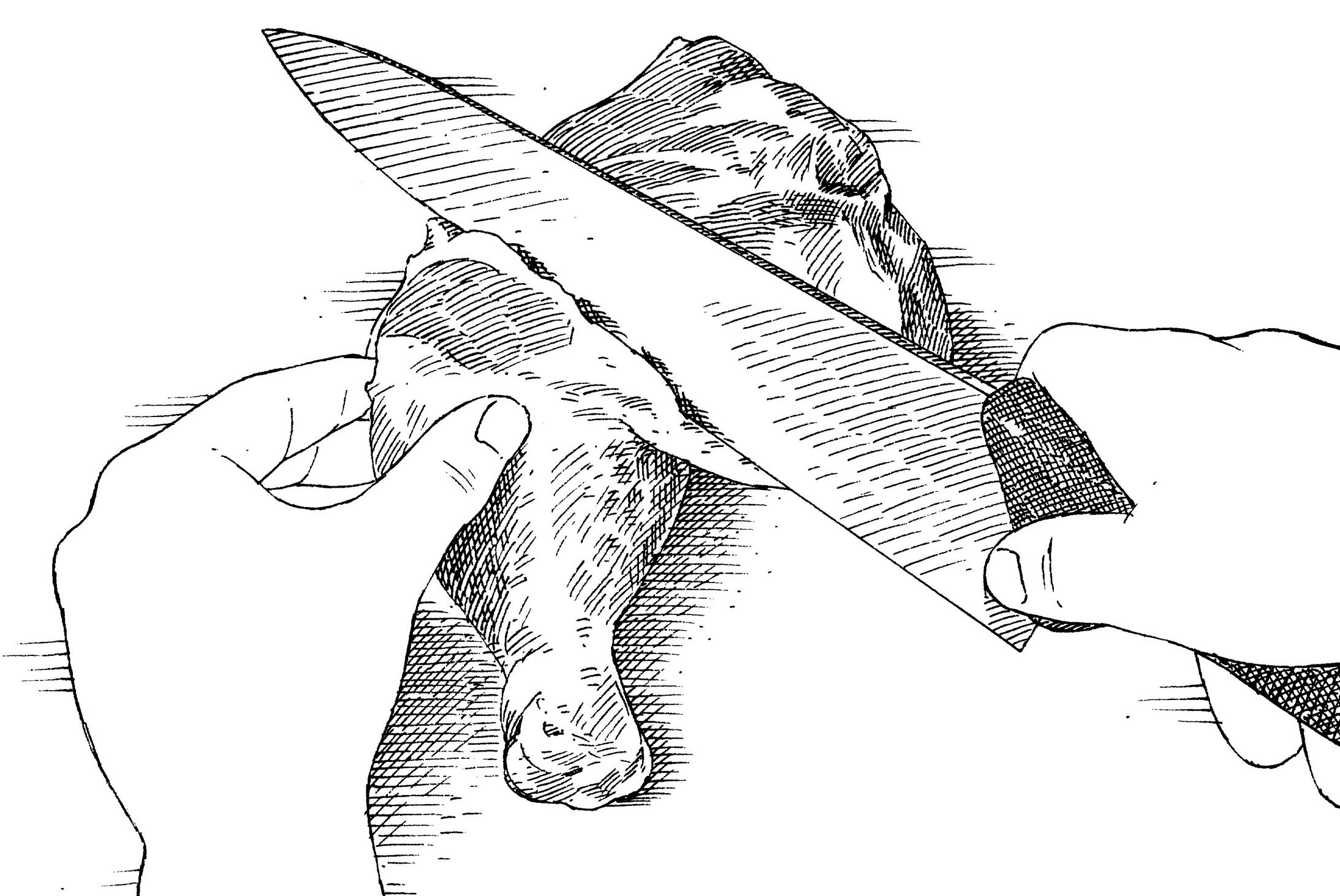

There were a number of hurdles to achieving the same chicken-skin nirvana at home, not the least of which was the cut of meat itself. At Maialino, the kitchen serves half of a chicken per person, removing all but the wing bones from the meat before searing it.

The point of all that butchery is to flatten out the bird so that its entire surface makes direct, even contact with the pan—a must for producing thoroughly rendered, deeply crisped skin. But since few home cooks can do that kind of knife work confidently and quickly, I decided to keep things simple and work with only breast meat. Removing the breast bones required just a few quick strokes of a sharp knife. Moreover, switching from half chickens to split breasts made for more reasonable portions. I would serve a pair of breasts—enough for two people—and keep things simple so that the dish would work as a weeknight meal.

Of course, the drawback to working with breast meat would be its tendency to overcook, particularly once I’d removed the bones—poor conductors of heat and, therefore, good insulators. My very basic initial cooking technique was placing the boned breasts skin side down in a hot, oiled skillet to crisp up their surface and then flipping the meat to let it color briefly on the other side. This gave me fairly crispy skin but meat that was dry and chalky. When I tried a slightly gentler approach, briefly pan-searing the chicken skin side down and then transferring the pan to the more even heat of a 450-degree oven until the breasts were cooked through, the meat was only somewhat more moist and tender. Clearly, some form of pretreatment was essential if I wanted the meat to be as succulent as the skin was crispy.

Brining was out, since it introduces additional water to the meat and inevitably leaves the skin slightly waterlogged. Salting would be the way to go. Besides seasoning the meat deeply and helping it retain moisture as it cooks, salt would assist in drying out the skin. To further encourage the skin’s dehydration (as well as the salt’s penetration), I poked holes in both the skin and meat with a sharp knife before applying the salt.

WORTH THE WEIGHT

Salting and slashing helped, but they got me only so far with the skin, which indicated that my simple searing technique needed tweaking. Thus far, the best I’d accomplished was unevenly cooked skin: patches that were gorgeously crispy and brown and adjacent patches that were inedibly pale and flabby. What’s more, the skin tended to shrink away from the edges of the breast as it cooked, which, apart from the unsightly appearance, caused the now-exposed meat to turn dry and leathery. Finally, the thin end of the breast still cooked up a bit dry by the time the thick end had fully cooked.

Evening out the thickness of the meat was easy: I simply pounded the thick end of the breast gently so that the entire piece cooked at the same rate. As for evening out the browning of the skin, I adapted a classic Italian technique that the chef at Maialino also uses: pinning the bird to the cooking surface with bricks. I mimicked that technique by weighing down the chicken breasts with a heavy Dutch oven. (Since I had no interest in transferring the weighty duo of pans to the oven, I’d switch to cooking the breasts entirely on the stovetop.) After cooking the breasts for 10 minutes over medium heat, I removed the pot and surveyed the skin, which, for the most part, was far crispier than ever before and not at all shrunken. But pockets of fat persisted under the surface at the center and along the edges. And the meat? It was way overcooked now that it was pressed hard against the hot surface.

Amid my frustration, I had noticed that when I removed the Dutch oven, a puff of steam arose from the pan—moisture from the chicken that had been trapped beneath the pot. That moisture was thwarting my skin-crisping efforts, so I wondered if the weight was necessary for the entire cooking time or if I could remove it partway through to prevent moisture buildup.

I prepared another batch, this time letting the breasts cook in the preheated oiled skillet under the pot for just 5 minutes before uncovering them. At this stage the skin was only just beginning to brown, but as it continued to cook for another 2 to 4 minutes, the skin remained anchored to the pan, crisping up nicely without contracting in the least. Removing the pot early also allowed the meat to cook a bit more gently. But it wasn’t quite gentle enough; dry meat still persisted.

The core problem—that it takes longer to render and crisp chicken skin than it does to cook the meat—had me feeling defeated until I realized a way to give the skin a head start: a “cold” pan. It’s a classic French technique for cooking duck breasts—the ultimate example of delicate meat covered with a layer of fatty skin. Putting the meat skin side down in the oiled pan before turning on the heat allows more time for the skin to render out its fat before the temperature of the meat reaches its doneness point. I hoped this approach would apply to chicken.

Initially, I thought I’d hit a roadblock: The breasts were sticking to the skillet—a nonissue when adding proteins to a hot pan, which usually prevents sticking. Fortunately, by the time the skin had rendered and fully crisped up, the breasts came away from the surface with just a gentle tug. Once the skin had achieved shattering crispiness, all it took was a few short minutes on the second side to finish cooking the meat.

TRY A LITTLE TANGINESS

The chicken was tasty enough as is, but to dress things up a bit, I set my sights on developing a few sauces.

My own rendition of Maialino’s alla diavola sauce was a reduction of pickled-pepper vinegar and chicken broth, thickened with a little flour and butter and garnished with a few chopped pickled peppers. I also came up with a pair of variations on the same acid-based theme: lemon-rosemary and maple–sherry vinegar.

Satisfying my inner chicken skin perfectionist was gratifying in and of itself. But coming up with a quick and elegant way to dress up ordinary old chicken breasts? That was even better.

Crispy-Skinned Chicken Breasts with Vinegar-Pepper Pan Sauce

Crispy-Skinned Chicken Breasts with Vinegar-Pepper Pan Sauce

SERVES 2

This recipe requires refrigerating the salted meat for at least 1 hour before cooking. Two 10- to 12-ounce chicken breasts are ideal, but three smaller ones can fit in the same pan; the skin will be slightly less crispy. A boning knife or sharp paring knife works best to remove the bones from the breasts. To maintain the crispy skin, spoon the sauce around, not over, the breasts when serving.

Chicken

2 (10- to 12-ounce) bone-in split chicken breasts

Kosher salt and pepper

2 tablespoons vegetable oil

Pan Sauce

1 shallot, minced

1 teaspoon all-purpose flour

½ cup chicken broth

¼ cup chopped pickled hot cherry peppers, plus ¼ cup brine

1 tablespoon unsalted butter, chilled

1 teaspoon minced fresh thyme

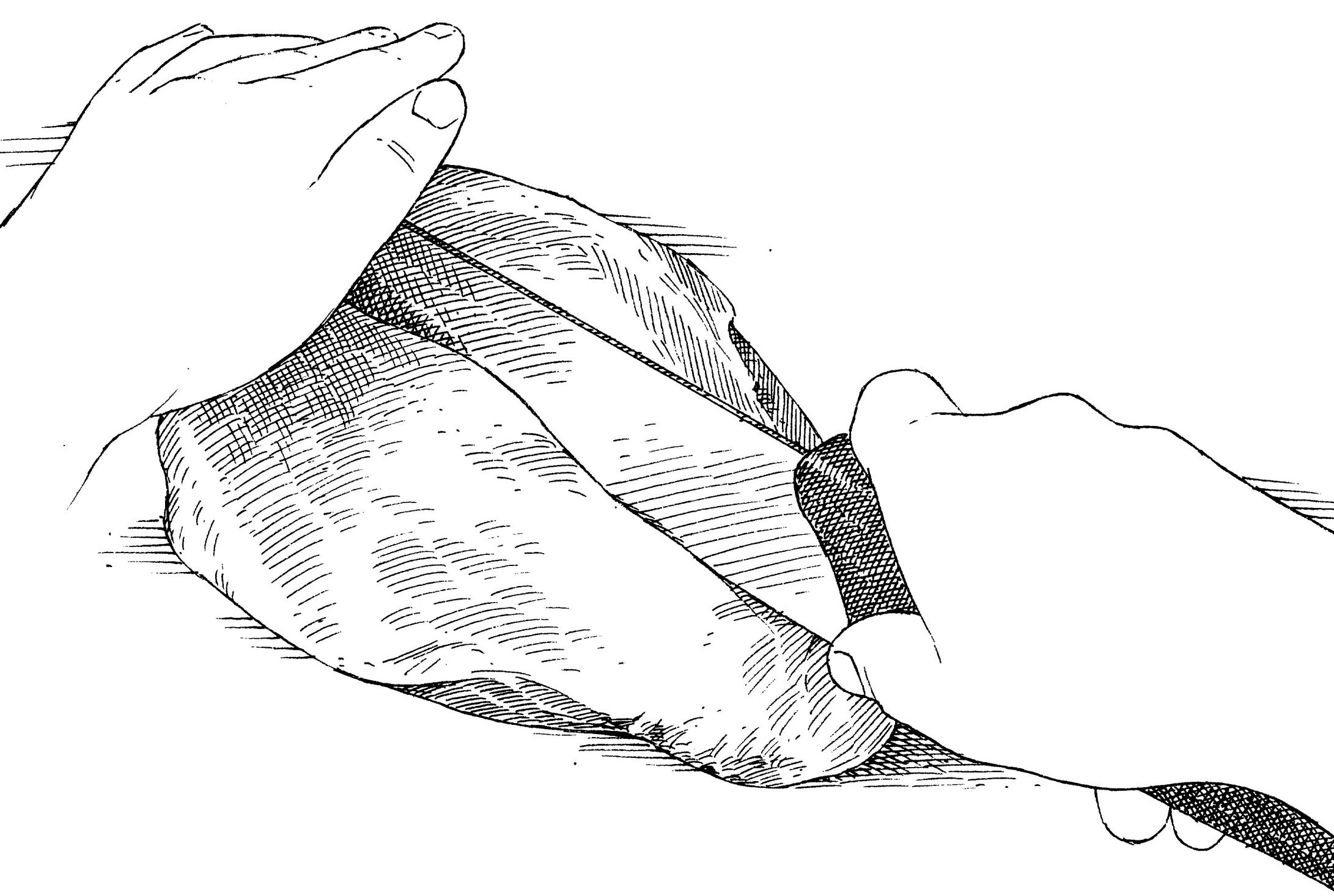

Salt and pepper

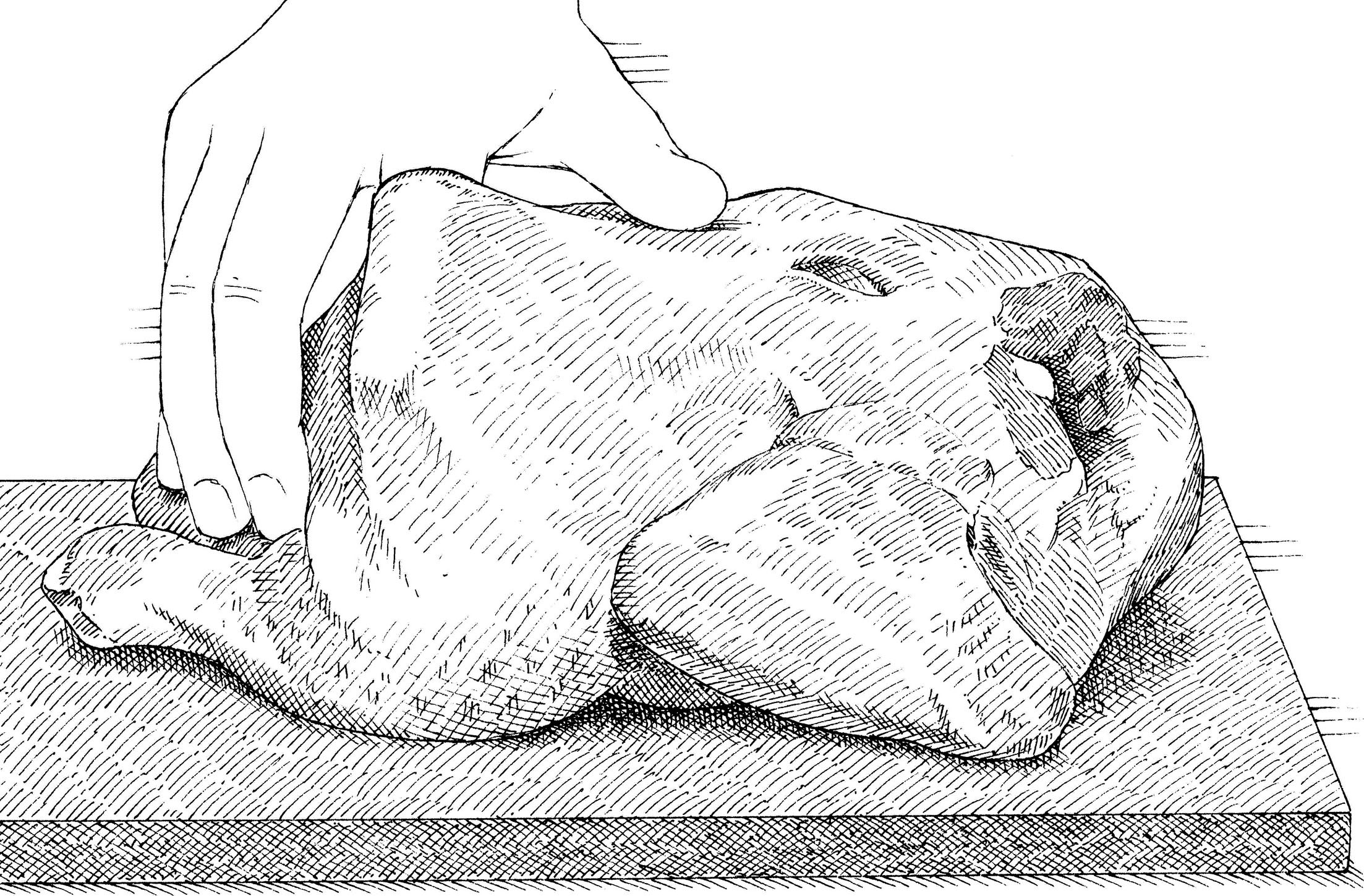

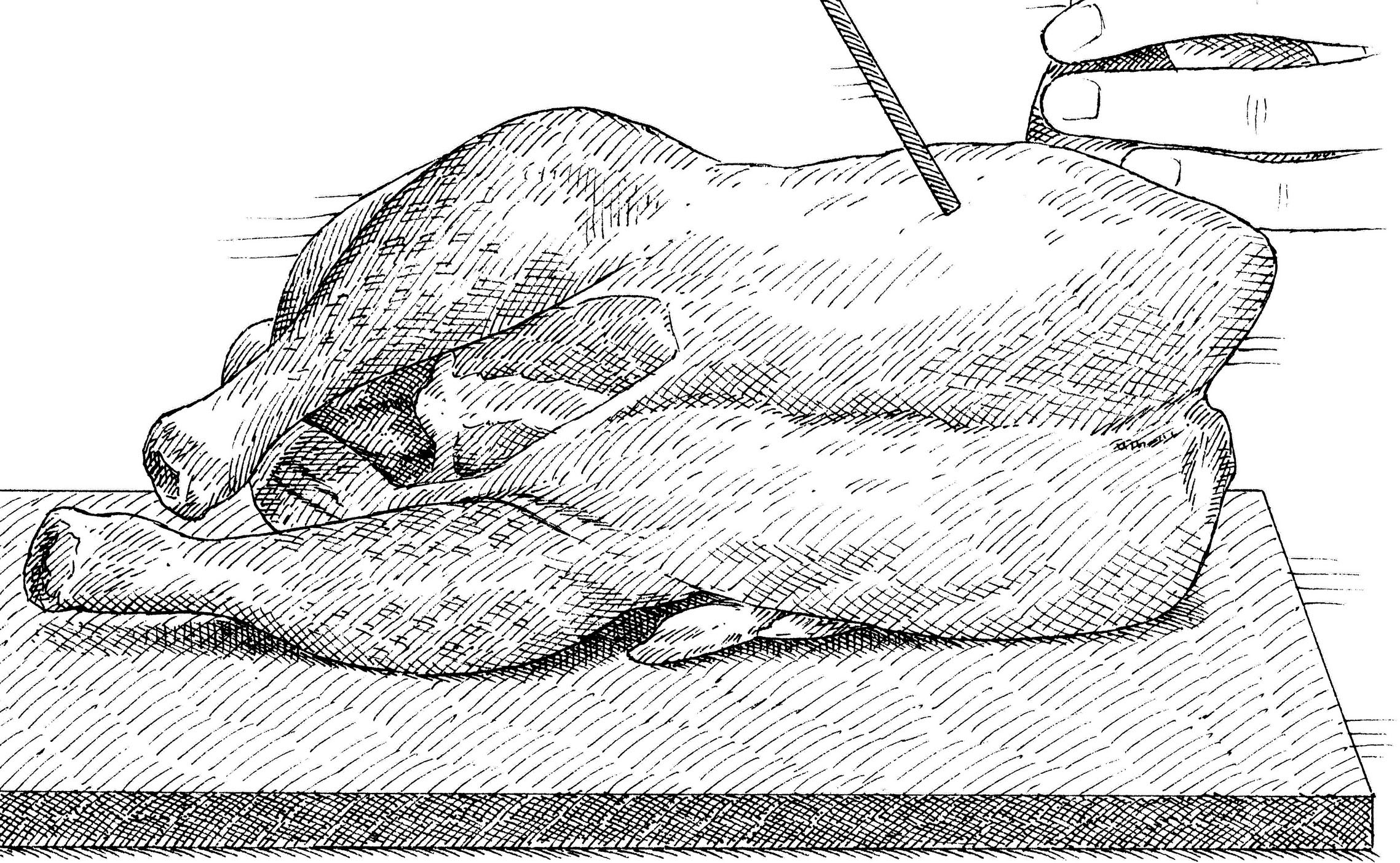

1. For the chicken: Place 1 chicken breast, skin side down, on cutting board, with ribs facing away from knife hand. Run tip of knife between breastbone and meat, working from thick end of breast toward thin end. Angling blade slightly and following rib cage, repeat cutting motion several times to remove ribs and breastbone from breast. Find short remnant of wishbone along top edge of breast and run tip of knife along both sides of bone to separate it from meat. Remove tenderloin (reserve for another use) and trim excess fat, taking care not to cut into skin. Repeat with second breast.

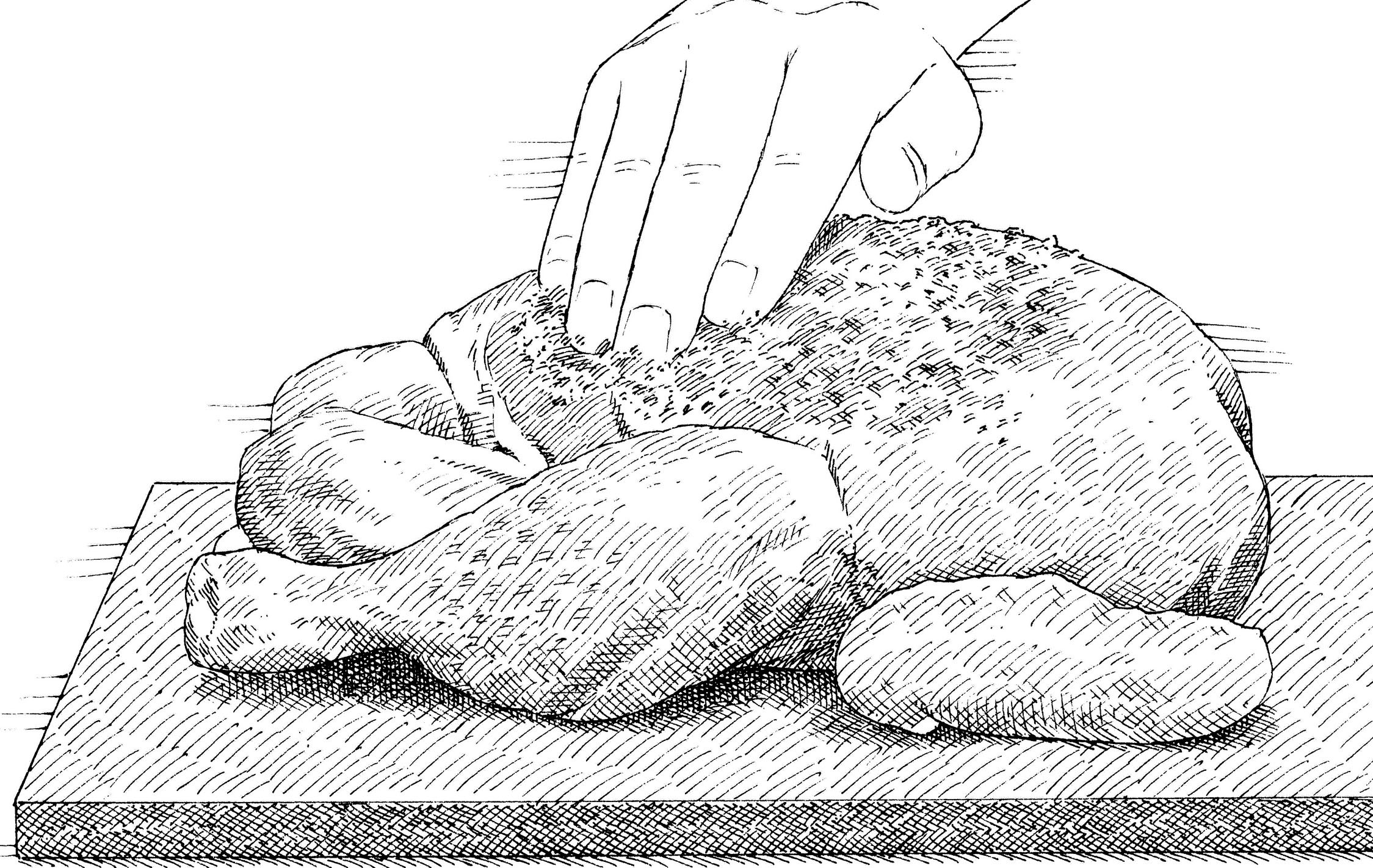

2. Using tip of paring knife, poke skin on each breast evenly 30 to 40 times. Turn breasts over and poke thickest half of each breast 5 or 6 times. Cover breasts with plastic wrap and pound thick ends gently with meat pounder until ½ inch thick. Evenly sprinkle each breast with ½ teaspoon kosher salt. Place breasts, skin side up, on wire rack set in rimmed baking sheet, cover loosely with plastic, and refrigerate for at least 1 hour or up to 8 hours.

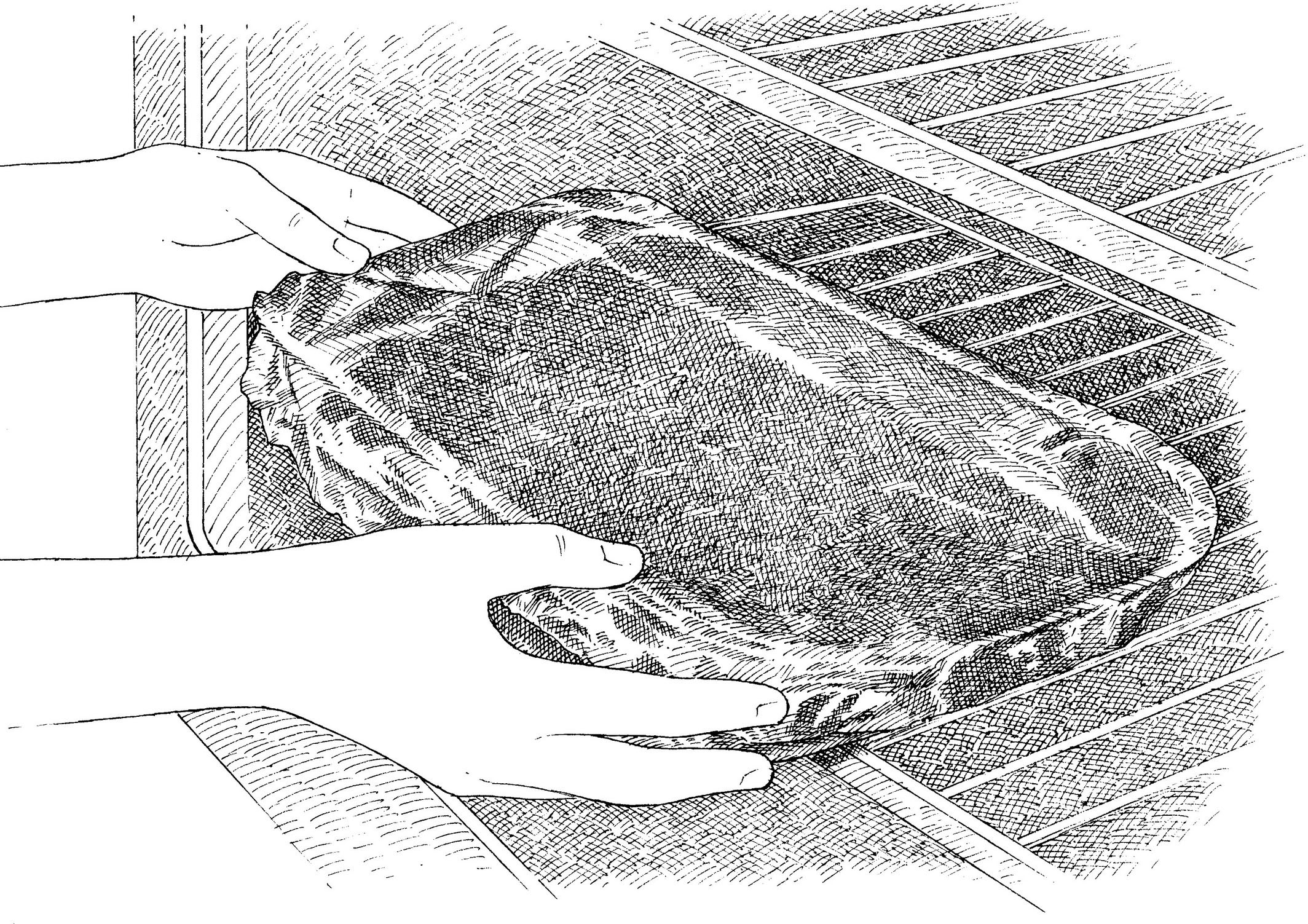

3. Pat breasts dry with paper towels and sprinkle each breast with ¼ teaspoon pepper. Pour oil in 12-inch skillet and swirl to coat. Place breasts, skin side down, in oil and place skillet over medium heat. Place heavy skillet or Dutch oven on top of breasts. Cook breasts until skin is beginning to brown and meat is beginning to turn opaque along edges, 7 to 9 minutes.

4. Remove weight and continue to cook until skin is well browned and very crispy, 6 to 8 minutes. Flip breasts, reduce heat to medium-low, and cook until second side is lightly browned and meat registers 160 to 165 degrees, 2 to 3 minutes. Transfer breasts to individual plates and let rest while preparing pan sauce.

5. For the pan sauce: Pour off all but 2 teaspoons oil from skillet. Return skillet to medium heat and add shallot; cook, stirring occasionally, until shallot is softened, about 2 minutes. Add flour and cook, stirring constantly, for 30 seconds. Increase heat to medium-high, add broth and brine, and bring to simmer, scraping up any browned bits. Simmer until thickened, 2 to 3 minutes. Stir in any accumulated chicken juices; return to simmer and cook for 30 seconds. Remove skillet from heat and whisk in peppers, butter, and thyme; season with salt and pepper to taste. Spoon sauce around breasts and serve.

variations

Crispy-Skinned Chicken Breasts with Maple–Sherry Vinegar Pan Sauce

In step 5, substitute 2 tablespoons sherry vinegar for brine, 1 tablespoon maple syrup for peppers, and sage for thyme.

Crispy-Skinned Chicken Breasts with Lemon-Rosemary Pan Sauce

In step 5, increase broth to ¾ cup and substitute 2 tablespoons lemon juice for brine. Omit peppers and substitute rosemary for thyme.

The most common, and probably most appealing, stir-fry is made with chicken. Sounds easy, right? Well, it turns out that a good chicken stir-fry is more difficult to prepare than a beef or pork stir-fry because chicken, which has less fat, inevitably becomes dry and stringy when cooked over high heat. I was after a stir-fry that featured tender, juicy, bite-size pieces of chicken paired with just the right combination of vegetables in a simple yet complex-flavored sauce. And because this was a stir-fry, it had to be fairly quick.

In the past, we’ve used a marinade to impart flavor to meat destined for stir-fries. Chicken was no exception. Tossing the pieces of chicken into a simple soy-sherry mixture for 10 minutes before cooking added much-needed flavor, but it did nothing to improve the texture of the meat.

The obvious solution to dry chicken was brining, our favorite method of adding moisture to poultry. A test of brined boneless breasts (preferred over thighs) did in fact confirm that this method solved the problem of dry chicken. However, a half hour or more of brining time followed by 10 minutes of marinating was out of the question for a quick midweek stir-fry. It seemed redundant to soak the chicken first in one salty solution (brine) and then another (marinade), so I decided to combine the two, using the soy sauce to provide the high salt level in my brine. This turned out to be a key secret of a great chicken stir-fry. Now I was turning out highly flavored, juicy pieces of chicken—most of the time. Given the finicky nature of high-heat cooking, some batches of chicken still occasionally turned out tough because of overcooking.

THE VELVET GLOVE

I next turned to a traditional Chinese technique called velveting, which involves coating chicken pieces in a thin cornstarch and egg white or oil mixture, then parcooking in moderately heated oil. The coating holds precious moisture inside; that extra juiciness makes the chicken seem more tender. Cornstarch mixed with egg white yielded a cakey coating; tasters preferred the more subtle coating provided by cornstarch mixed with oil. This velveted chicken was supple, but it was also pale, and, again, this method seemed far too involved for a quick weeknight dinner.

A hybrid brine/marinade gives lean chicken breasts flavor and moisture in minutes, guaranteeing that the pieces cook up tender and supple.

I wondered if the same method—coating in a cornstarch mixture—would work if I eliminated the parcooking step. It did. This chicken was not only juicy and tender, but it also developed an attractive golden brown coating. Best of all, the entire process took less than 5 minutes. The only problem was that the coating, which was more of an invisible barrier than a crust, became bloated and slimy when cooked in the sauce.

Our science editor explained that the cornstarch was absorbing liquid from the sauce, causing the slippery finish. He suggested cutting the cornstarch with flour, which created a negligible coating—not too thick, not too slimy—that still managed to keep juices inside the chicken. Substituting sesame oil for peanut oil added a rich depth of flavor.

After trying everything from pounded to cubed chicken, tasters voted for simple flat ¼-inch slices, which were all the more easy to cut after freezing the breasts for 15 minutes. These wide, flat slices of chicken browned easily. I cooked them in two batches, first browning one side and then turning them over to quickly brown the second side rather than constantly stirring (or “stir”-frying) as so many other recipes suggest. Although choosing not to stir-fry seemed counterintuitive, I found that the constant motion of that method detracted from the browning of the chicken.

THE FINISH

As for the vegetables in my recipe, a combination of bok choy and red bell pepper worked well with the chicken. For the sauce, the test kitchen has found that chicken broth, rather than soy sauce, makes the best base because it is not overpowering. Oyster sauce works nicely as a flavoring ingredient. We have also tested the addition of cornstarch to help the sauce coat the meat and vegetables and have found that a small amount is necessary. Otherwise, the sauce is too thin and does not adhere properly.

The basic stir-fry method was previously developed in the test kitchen. After the protein (in this case, the chicken) is cooked and removed from the pan, the vegetables are stir-fried in batches, garlic and ginger (the classic stir-fry combination) are quickly cooked in the center of the pan, and then the protein is returned to the pan along with the sauce. This final mixture is cooked over medium heat for 30 seconds to finish.

In the end, a great chicken stir-fry doesn’t really take more time to prepare than a bad one. It does, however, require more attention to detail and knowledge of a few quick tricks.

Gingery Stir-Fried Chicken and Bok Choy

SERVES 4

To make slicing the chicken easier, freeze it for 15 minutes. Serve with white rice.

Sauce

¼ cup chicken broth

2 tablespoons dry sherry

1 tablespoon soy sauce

1 tablespoon oyster sauce

2 teaspoons grated fresh ginger

1 teaspoon cornstarch

1 teaspoon sugar

½ teaspoon toasted sesame oil

¼ teaspoon red pepper flakes

Stir-Fry

2 teaspoons grated fresh ginger

1 garlic clove, minced

2 tablespoons plus 2 teaspoons vegetable oil

1 cup water

¼ cup soy sauce

¼ cup dry sherry

1 pound boneless, skinless chicken breasts, trimmed and cut crosswise into ¼-inch-thick strips

2 tablespoons toasted sesame oil

1 tablespoon cornstarch

1 tablespoon all-purpose flour

1 pound bok choy, stalks cut on bias into ¼-inch slices, greens cut into ½-inch-wide strips

1 small red bell pepper, stemmed, seeded, and cut into ¼-inch-wide strips

1. For the sauce: Whisk all ingredients together in bowl and set aside.

2. For the stir-fry: Combine ginger, garlic, and 1 teaspoon vegetable oil in small bowl and set aside. Combine water, soy sauce, and sherry in medium bowl. Add chicken and stir to break up clumps. Cover with plastic wrap and refrigerate for at least 20 minutes or up to 1 hour. Pour off liquid from chicken.

3. Mix sesame oil, cornstarch, and flour in medium bowl until smooth. Transfer chicken to bowl and toss with cornstarch mixture until evenly coated.

4. Heat 2 teaspoons vegetable oil in 12-inch nonstick skillet over high heat until just smoking. Add half of chicken to skillet in single layer and cook until golden brown, about 1 minute. Using tongs, flip chicken and lightly brown second side, about 30 seconds. Transfer chicken to clean bowl. Repeat with 2 teaspoons vegetable oil and remaining chicken.

5. Add remaining 1 tablespoon vegetable oil to now-empty skillet and heat until just smoking. Add bok choy stalks and bell pepper and cook, stirring, until beginning to brown, about 1 minute. Push vegetables to sides of skillet. Add ginger mixture to center and cook, mashing mixture into pan, until fragrant, about 30 seconds. Stir mixture into vegetables and continue to cook until stalks are crisp-tender, about 30 seconds longer. Stir in bok choy greens and cook until beginning to wilt, about 30 seconds.

6. Return chicken to skillet. Whisk sauce to recombine and add to skillet; reduce heat to medium and cook, stirring constantly, until sauce is thickened and chicken is cooked through, about 30 seconds. Transfer to platter and serve.

CHOOSING THE RIGHT PAN

When stir-frying, a 12-inch nonstick skillet is best: It’s large enough to accommodate food without any steaming or sticking. A flat-bottomed wok has less surface area in contact with the stovetop than the nonstick skillet. In conventional skillets, the chicken sticks, burns, or steams.

THE BEST CHOICE

Nonstick Skillet

A MEDIOCRE CHOICE

Flat-Bottomed Wok

A BAD CHOICE

Traditional Skillet

THE WORST CHOICE

Small Skillet

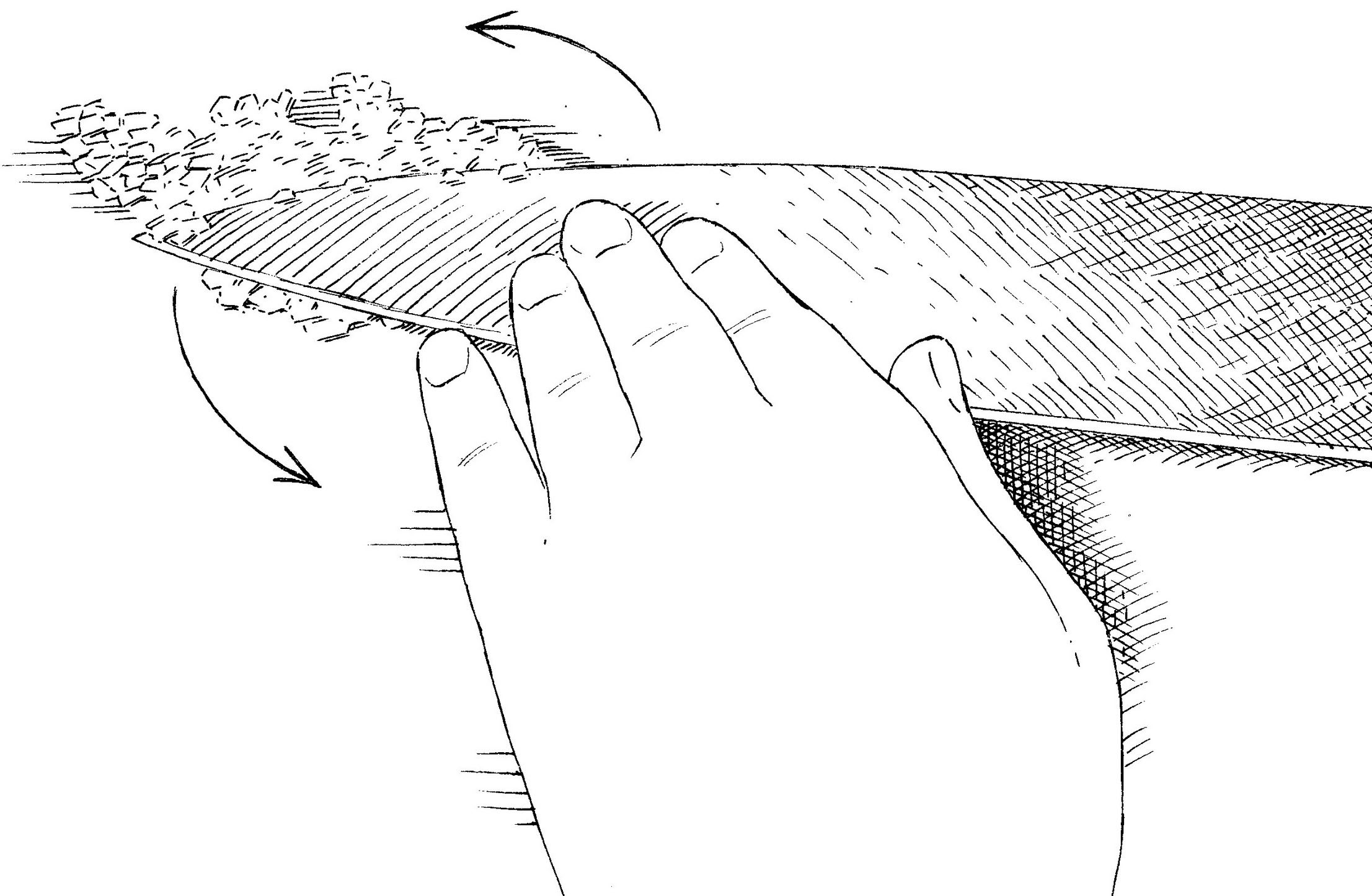

1. Trim bottom inch from head of bok choy. Cut leafy green portion away from either side of white stalk.

2. Cut each stalk in half lengthwise and then crosswise on bias into ¼-inch-wide pieces. Stack leafy greens and then slice crosswise into ½-inch-wide strips.

SLICING CHICKEN THIN

Slice breasts across grain into ¼-inch-wide strips. Cut center pieces in half so they are same length as end pieces. Cut tenderloins on diagonal to produce pieces similar in size to strips of breast meat.

LAN LAM, July/August 2013

I have fond memories of eating barbecued chicken when I was growing up, but not because the chicken was any good. My family’s version of this summertime staple, one of the few American dishes that my immigrant parents made, involved my father dousing chicken parts with bottled sauce and dumping the pieces over a ripping-hot fire. He would then spend the next 45 minutes shuffling them around on the grate in a vain effort to get the pieces to cook evenly. Some of the pieces always cooked up dry, while others were raw at the bone. Worse, flare-ups caused by fat dripping onto the coals carbonized the skin well before it had a chance to fully render. But it was summer, it was fun to eat outside, and if we poured enough of the (inevitably) ultrasweet sauce on the chicken, we could mask its shortcomings.

I’ve eaten enough subpar barbecued chicken to realize that my dad is not the only one who doesn’t know how to produce juicy, deeply seasoned, evenly cooked chicken parts on the grill. With decades of test kitchen barbecuing experience on my side, I set out to foolproof this American classic.

MAKING ARRANGEMENTS

There were a few basic barbecue tenets I put in place from the get-go. First, I ditched the single-level fire recommended by a surprising number of recipes and built an indirect one: I corralled all the coals on one side of the kettle, enabling me to sear the chicken over the hotter side and then pull it over to the cooler side, where the meat would cook gently and the skin could render slowly. Cooking the chicken opposite from (rather than on top of) the coals for most of the time would also cut back on flare-ups. Second, I salted the meat and let it sit for several hours before grilling it, since this pretreatment would change the meat’s protein structure so that it would hold on to more moisture as it cooked—added insurance against overcooking. Finally, I would wait to apply barbecue sauce (which usually contains sugary ingredients) until after searing; this would prevent the sauce from burning and give the skin a chance to develop color.

I proceeded to sear 6 pounds of breasts and leg quarters on the hotter part of the grill. Once both sides of the meat were brown, I dragged the pieces to the cooler part of the kettle, painted on some placeholder bottled sauce, and considered my core challenge: how to ensure that both the white and dark pieces cooked at an even pace.

Since food that sits closest to the fire cooks faster, I lined up the fattier, more heat-resistant leg quarters closest to the coals and the leaner, more delicate breasts farther away and covered the grill. About an hour later, the breast meat was just about done, the skin was nicely rendered and thin, and the sauce was concentrated and set. The problem was that several leg quarters were chewy and dry. Salting clearly wasn’t enough to protect them from the heat, even when positioned next to the coals instead of on top of them.

Brushing the sauce on in stages keeps its flavor bright and prevents it from burning on the grill.

GETTING EVEN

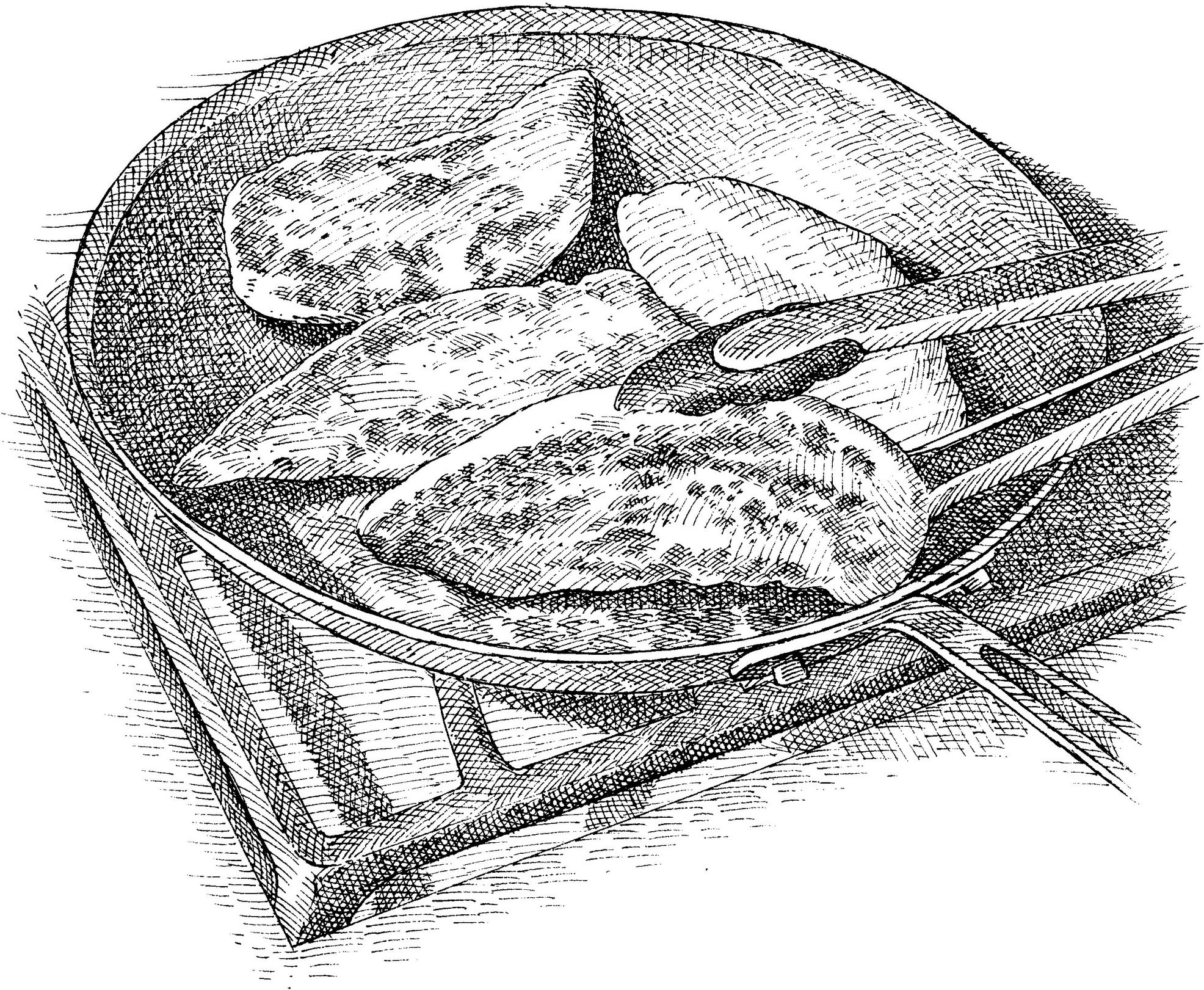

I needed a way to even out and lower the heat without using less charcoal (when I used 25 percent less charcoal, the heat dwindled before the meat finished cooking). Instead, I set a disposable aluminum pan opposite the coals and partially filled it with water. Both the pan and the water absorb heat, lowering the overall temperature inside the kettle and eliminating hot spots.

I cooked another batch using the water pan and finally made some headway. The ambient temperature inside the grill had dropped by about 50 degrees—a good sign. I checked the pieces midway through grilling and was pleased to see that the dark meat was cooking at a slower, steadier pace. By the end of the hour, both the white and dark pieces were hitting their target temperatures (160 and 175 degrees, respectively).

FLAVOR MAKERS

My cooking method had come a long way, but I could hardly call my results “barbecued.” For one thing, I needed a homemade alternative for the characterless bottled sauce. My tasters also reminded me that, although the chicken was nicely seasoned after salting, the flavor of the meat itself was unremarkable once you got past the skin.

But salting the chicken reminded me that I could easily apply bolder flavor in the same way—with a rub. I kept the blend basic: In addition to the kosher salt, I mixed together equal amounts of onion and garlic powders and paprika; a touch of cayenne for subtle heat; and a generous 2 tablespoons of brown sugar, which would caramelize during cooking.

For the sauce, I fell back on the test kitchen’s go-to recipe, which smartens the typical ketchup-based concoction. Molasses adds depth, while cider vinegar, Worcestershire sauce, and Dijon mustard keep sweetness in check. Grated onion, minced garlic, chili powder, cayenne, and pepper round out the flavors.

But there was a downside to applying the sauce just after searing: Namely, after cooking for an hour, it lost a measure of its bright tanginess. Instead, I applied the sauce in stages, brushing on the first coat just after searing and then applying a second midway through grilling. That minor adjustment made a surprisingly big difference. I also reserved some of the sauce for passing at the table.

This was perfectly cooked, seriously good chicken. Now all I have to do is convince my dad to let me handle the cooking at our next family barbecue.

Sweet and Tangy Barbecued Chicken

SERVES 6 TO 8

When browning the chicken over the hotter side of the grill, move it away from any flare-ups.

Chicken

2 tablespoons packed dark brown sugar

1½ tablespoons kosher salt

1½ teaspoons onion powder

1½ teaspoons garlic powder

1½ teaspoons paprika

¼ teaspoon cayenne pepper

6 pounds bone-in chicken pieces (split breasts and/or leg quarters), trimmed

Sauce

1 cup ketchup

5 tablespoons molasses

3 tablespoons cider vinegar

2 tablespoons Worcestershire sauce

2 tablespoons Dijon mustard

¼ teaspoon pepper

2 tablespoons vegetable oil

⅓ cup grated onion

1 garlic clove, minced

1 teaspoon chili powder

¼ teaspoon cayenne pepper

1 large disposable aluminum roasting pan (if using charcoal) or 2 disposable aluminum pie plates (if using gas)

1. For the chicken: Combine sugar, salt, onion powder, garlic powder, paprika, and cayenne in bowl. Arrange chicken on rimmed baking sheet and sprinkle both sides evenly with spice rub. Cover with plastic wrap and refrigerate for at least 6 hours or up to 24 hours.

2. For the sauce: Whisk ketchup, molasses, vinegar, Worcestershire, mustard, and pepper together in bowl. Heat oil in medium saucepan over medium heat until shimmering. Add onion and garlic; cook until onion is softened, 2 to 4 minutes. Add chili powder and cayenne and cook until fragrant, about 30 seconds. Whisk in ketchup mixture and bring to boil. Reduce heat to medium-low and simmer gently for 5 minutes. Set aside ⅔ cup sauce to baste chicken and reserve remaining sauce for serving. (Sauce can be refrigerated for up to 1 week.)

3A. For a charcoal grill: Open bottom vent halfway and place disposable pan filled with 3 cups water on 1 side of grill. Light large chimney starter filled with charcoal briquettes (6 quarts). When top coals are partially covered with ash, pour evenly over other half of grill (opposite disposable pan). Set cooking grate in place, cover, and open lid vent halfway. Heat grill until hot, about 5 minutes.

3B. For a gas grill: Place 2 disposable pie plates, each filled with 1½ cups water, directly on 1 burner of gas grill (opposite primary burner). Turn all burners to high, cover, and heat grill until hot, about 15 minutes. Turn primary burner to medium-high and turn off other burner(s). (Adjust primary burner as needed to maintain grill temperature of 325 to 350 degrees.)

4. Clean and oil cooking grate. Place chicken, skin side down, over hotter side of grill and cook until browned and blistered in spots, 2 to 5 minutes. Flip chicken and cook until second side is browned, 4 to 6 minutes. Move chicken to cooler side and brush both sides with ⅓ cup sauce. Arrange chicken, skin side up, with leg quarters closest to fire and breasts farthest away. Cover (positioning lid vent over chicken if using charcoal) and cook for 25 minutes.

5. Brush both sides of chicken with remaining ⅓ cup sauce and continue to cook, covered, until breasts register 160 degrees and leg quarters register 175 degrees, 25 to 35 minutes longer.

6. Transfer chicken to serving platter, tent with aluminum foil, and let rest for 10 minutes. Serve, passing reserved sauce separately.

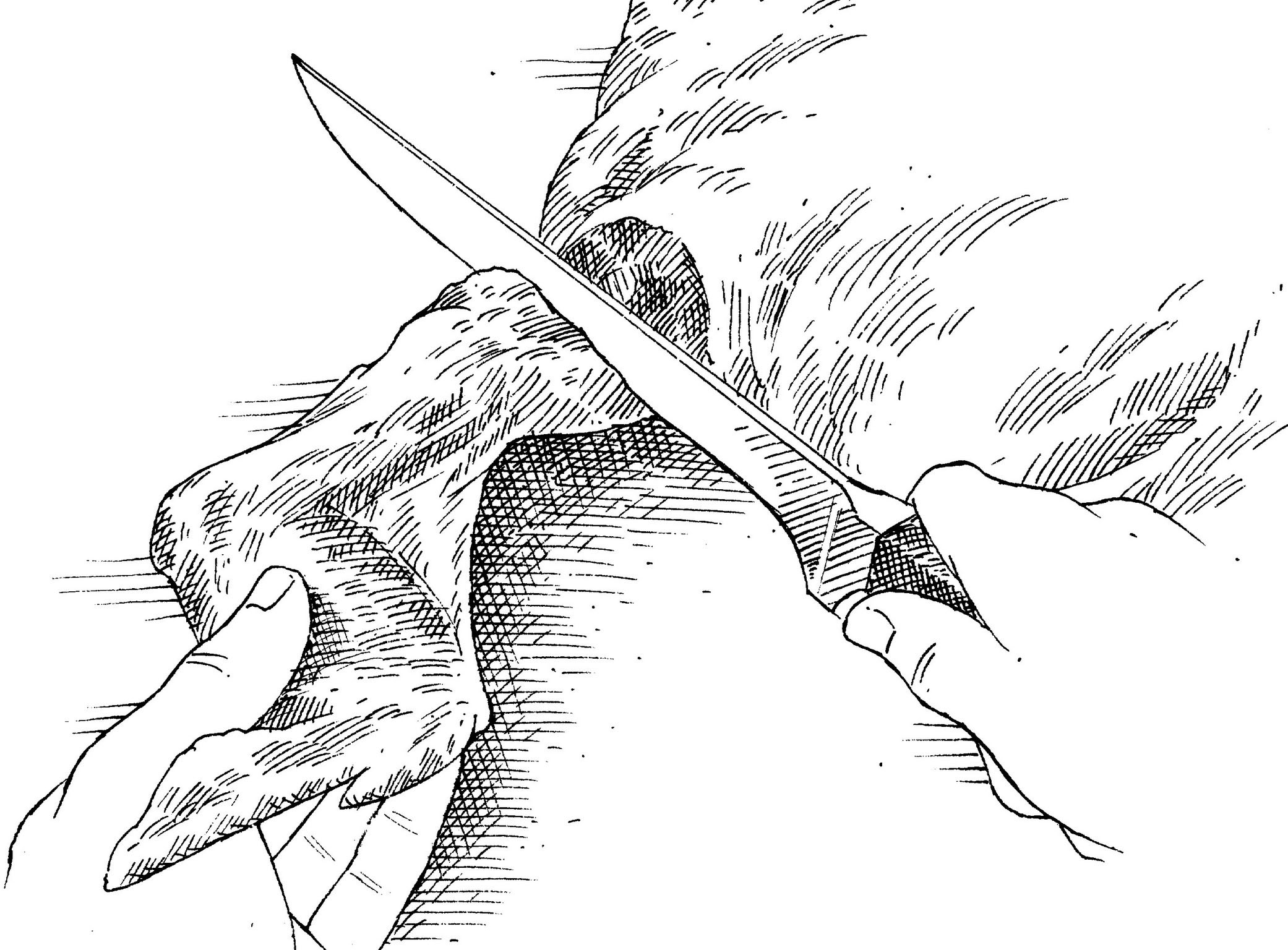

DOES YOUR LEG QUARTER NEED A TRIM?

Some leg quarters come with the backbone still attached. Here’s an easy way to remove it.

Holding the leg quarter skin side down, grasp the backbone and bend it back to pop the thigh bone out of its socket. Place the leg on a cutting board and cut through the joint and any attached skin.

PACKAGED PARTS HAVE A WEIGHT PROBLEM

Grabbing a package of chicken parts is usually a lot faster than standing in line at the meat counter to buy them individually. But that convenience may come at a cost. The same chicken parts aren’t required to be the same weight and their size can vary dramatically. For example, the U.S. Department of Agriculture permits leg quarters sold together to weigh between 8.5 and 24 ounces. Breasts can come from chickens that weigh between 3 and 5.5 pounds—a difference that translates to the breasts themselves. Such a disparity can be a problem when you’re trying to get food to cook at the same rate. This lack of standardization showed up in our own shopping. We bought 26 packages of split breasts and leg quarters (representing five brands) from five different supermarkets. When we weighed each piece and calculated the maximum weight variation within each package, the differences were startling: The largest pieces were twice the size of the smallest. Worse, some leg quarters came with attached backbone pieces that had to be cut off and discarded (which means throwing away money). Lesson learned: Whenever possible, buy chicken parts individually from a butcher, who can select similar-size pieces.

In theory, barbecued chicken kebabs sound pretty great: char-streaked chunks of juicy meat lacquered with sweet-sharp barbecue sauce. Using skewers sounds easy, too—a fast-and-loose sort of way to capture the charms of barbecued chicken without the time and patience needed to cook a whole bird or the focus essential to tending a host of mixed parts. Ah, but if only the kebabs lived up to that promise. The quandary is that without an insulating layer of skin, even the fattiest thigh meat can dry out and toughen when exposed to the blazing heat of the grill. And forget about ultralean skinless breast meat: It’s a lost cause. Simply slathering barbecue sauce onto skewered chicken chunks—the approach embraced by most recipes—does little to address this fundamental problem. In fact, it’s often one of the ruining factors: If applied too early or in too great a volume, the sauce drips off the meat, burns, and fixes the chicken fast to the grill.

RUBBED THE RIGHT WAY

My goal was simple: juicy, tender chicken with plenty of sticky-sweet, smoke-tinged flavor. I wanted an everyday sort of recipe, one that would work equally well with white or dark meat (skewered separately since they cook at different rates) and brushed with a no-nonsense homemade barbecue sauce. But before I got to the sauce (I would use a simple ketchup-based placeholder for now), I had to ensure that the meat was as moist and tender as possible. Brining was the natural next step.

The secret to the best smoky, richly flavored chicken kebabs is rubbing them with a spiced bacon paste.

When meat soaks in salty water, the salt helps pull the liquid into the meat, plumping the chicken and thoroughly seasoning it. The salt also denatures the meat proteins, creating gaps that trap water and guard against drying out. But brining isn’t a cure-all: When I made kebabs with chicken breasts and thighs that I brined after cutting them into pieces (1-inch chunks cooked through relatively quickly yet required enough time on the grill to pick up smoky flavor), the brine made the meat so slick and wet that any barbecue sauce I brushed on toward the end of cooking dribbled off.

Would a dry method work better? Sure enough, a heavily salted dry spice mixture (I let the rubbed chicken sit for 30 minutes before grilling) was just the ticket. As the mixture sat, the salt drew the juices to the surface of the chicken pieces, where they mixed with the seasonings and then flowed back into the chicken. The rub also crisped up on the chicken’s exterior as it cooked, forming a craggy surface that the sauce could really cling to. To avoid overpowering the chicken, I steered clear of outspoken spices, settling on both sweet and smoked paprika, the former contributing depth and the latter helping to boost the overall smokiness of the dish. A few teaspoons of sugar added to the rub aided in browning, pleasantly complicating flavor.

WHEN CHICKEN MEETS PIG

With its ruddy exterior, my chicken now looked the part, but the meat was still not quite moist enough and, despite the improvements made by the spices, lacked sufficient depth of flavor. In a hunt for a solution, I read up on Middle Eastern kebab cookery. I learned that Turkish chefs skewer slices of pure lamb fat between lamb chunks before grilling. The fat melts during cooking, continually basting the lean meat.

Using musky lamb fat in a chicken recipe seemed too weird, but what about another fatty yet more complementary meat: smoky bacon? I cut several strips into 1-inch pieces and spliced the chicken pieces with the fatty squares before putting the kebabs on the grill. Unfortunately, by the time the chicken was cooked through, the bacon—tightly wedged as it was between the chicken chunks—had failed to crisp. For my next attempt, I tried wrapping strips of bacon around the kebabs in a spiral-like helix. This time, the bacon turned crunchy, but its flavor overwhelmed the chicken’s more delicate taste.

If strips didn’t work, how about rendered bacon fat? I liberally coated the prepared kebabs with drippings from freshly cooked bacon and set them on the grill grate. Within minutes, the fat trickled into the coals and prompted flare-ups, blackening most of the chicken. What wasn’t burnt, however, was moist and tasted addictively smoky.

If raw strips were too much of a good thing and rendered fat dripped off too quickly, was there an in-between solution? This time around, I finely diced a few slices of bacon and mixed them with the chicken chunks, salt, and spices. After giving the kebabs a 30-minute rest in the refrigerator, I grilled them over a moderately hot half-grill fire. (I had piled all of the coals on one side of the grill and left the other half empty to create a cooler “safety zone” on which to momentarily set the kebabs in the event of a flare-up.) Once the chicken was browned on one side (this took about 2 minutes), I flipped it a quarter turn, giving me nearly done meat in about eight minutes. At this point, I brushed barbecue sauce onto the kebabs, leaving them on the grill for just a minute or two longer to give the sauce a chance to caramelize. (Adding the sauce any earlier is a surefire route to scorched chicken.) The bacon bits clung tenaciously to the chicken, producing the best results yet.

But I wasn’t finished. The bacon hadn’t cooked evenly: Some bits were overly crisp and others still a little limp. I had an idea that would take care of the problem: grinding the bacon into a spreadable paste. Admittedly, the concept was a bit wacky, but I’d come this far with bacon, so why not? I tossed a couple of strips of raw bacon into a food processor and ground them down to a paste, which I then mixed with the chicken chunks and dry rub. As before, I rested the coated chicken in the refrigerator for half an hour before putting it on the grill. The chicken looked beautiful when it came off the fire: deeply browned and covered in a thick, shiny glaze, with no burnt bacon bits in sight. But to my great disappointment, not to mention puzzlement, the chicken was now dry and had lost flavor. I repeated the test to make sure this batch wasn’t a fluke and got the same results.

What could be going on? The only thing I was doing differently was coating the chicken in paste rather than simply mixing it with small pieces of the smoked meat combined with the salt, sugar, and spices. Then it occurred to me: Maybe the fatty ground-up bacon was adhering so well to the chicken that it was acting as a barrier to the salt, which now couldn’t penetrate the meat. What if I first salted the meat for 30 minutes, then tossed it with the sugar, spices, and bacon paste right before I put it on the grill? This simple change was the answer: The chicken was juicy, tender, and full-flavored, with a smoky depth that complemented the barbecue sauce. Now about that sauce…To enliven my classic ketchup, mustard, and cider vinegar mixture, I stirred in some grated onion and Worcestershire sauce. A spoonful of brown sugar and a little molasses added just enough bittersweet flavor to counter the sauce’s tanginess. Simmered for a few minutes, the mixture tasted bright and balanced and boasted a thick, smooth texture that clung well to the chicken. As I watched this final batch of supremely moist, smoky, perfectly cooked kebabs disappear as fast as I could pull them off the grill, I knew that this recipe had realized its full potential.

SERVES 6

Use the large holes of a box grater to grate the onion. We prefer dark thigh meat for these kebabs, but white meat can be used. Don’t mix white and dark meat on the same skewer, since they cook at different rates. If you have thin pieces of chicken, cut them larger than 1 inch and roll or fold them into approximate 1-inch cubes. Turbinado sugar is commonly sold as Sugar in the Raw. Demerara sugar can be substituted. You will need four 12-inch metal skewers for this recipe.

Sauce

½ cup ketchup

¼ cup molasses

2 tablespoons grated onion

2 tablespoons Worcestershire sauce

2 tablespoons Dijon mustard

2 tablespoons cider vinegar

1 tablespoon packed light brown sugar

Kebabs

2 pounds boneless, skinless chicken breasts or thighs, trimmed and cut into 1-inch chunks

2 teaspoons kosher salt

2 tablespoons paprika

4 teaspoons turbinado sugar

2 teaspoons smoked paprika

2 slices bacon, cut into ½-inch pieces

1. For the sauce: Bring all ingredients to simmer in small saucepan over medium heat and cook, stirring occasionally, until reduced to about 1 cup, 5 to 7 minutes. Transfer ½ cup sauce to small bowl and set aside for cooking; set aside remaining sauce for serving.

2. For the kebabs: Toss chicken and salt together in large bowl; cover with plastic wrap and refrigerate for at least 30 minutes or up to 1 hour.

3. Pat chicken dry with paper towels. Combine paprika, sugar, and smoked paprika in small bowl. Process bacon in food processor until smooth paste forms, 30 to 45 seconds, scraping down sides of bowl as needed. Add bacon paste and spice mixture to chicken and mix until chicken is completely coated. Thread chicken tightly onto four 12-inch metal skewers.

4A. For a charcoal grill: Open bottom vent completely. Light large chimney starter three-quarters filled with charcoal briquettes (4½ quarts). When top coals are partially covered with ash, pour evenly over half of grill. Set cooking grate in place, cover, and open lid vent completely. Heat grill until hot, about 5 minutes.

4B. For a gas grill: Turn all burners to high, cover, and heat grill until hot, about 15 minutes. Turn all burners to medium-high.

5. Clean and oil cooking grate. Place kebabs on grill (on hotter side if using charcoal) and cook (covered if using gas), turning kebabs every 2 to 2½ minutes, until well browned and slightly charred, about 8 minutes. Brush top surface of kebabs with ¼ cup reserved sauce for cooking, flip, and cook until sauce is sizzling and browning in spots, about 1 minute. Brush second side of kebabs with remaining ¼ cup reserved sauce for cooking, flip, and continue to cook until sizzling and browning in spots, about 1 minute longer.

6. Transfer kebabs to large platter, tent with aluminum foil, and let rest for 5 to 10 minutes. Serve, passing reserved sauce for serving separately.

BACON PASTE—WEIRD BUT IT WORKS

To create a protective coating that keeps the chicken moist on the grill, we chop two slices of bacon, pulse them in a food processor until smooth, and then toss the resulting paste (along with sugar and spices) with the raw chicken chunks.

Throwing a few boneless, skinless chicken breasts on the grill and painting them with barbecue sauce always sounds like a good idea. This lean cut is available everywhere, it cooks fast, and it makes a light, simple meal. The trouble is that the results are usually flawed. Because these disrobed specimens cook in a flash over coals, it’s hard to get chicken that not only tastes grilled but also has a good glaze without overcooking it. Here’s the dilemma: If you wait to apply the glaze until the meat is browned well, it’s usually dry and leathery by the time you’ve lacquered on a few layers. (And you need a few layers to build anything more than a superficial skim of sauce.) But if you apply the glaze too soon, you don’t give the chicken a chance to brown, a flavor boost that this bland cut badly needs. Plus, the sugary glaze is prone to burning before the chicken cooks through.

But the ease of throwing boneless, skinless breasts on the grill is too enticing to pass up. I decided to fiddle with the approach until I got it right: tender, juicy chicken with the smoky taste of the grill, glistening with a thick coating of glaze. While I was at it, I wanted to create glazes specifically designed to accentuate, not overwhelm, this lean cut’s delicate flavors.

BETTER BROWNING IN A HURRY

My first step was to brine the meat. I knew that a 30-minute saltwater soak would help keep the chicken juicy and well seasoned and could be accomplished while the grill was heating. I also opted for a two-level fire, which means that I piled two-thirds of the coals on one side of the kettle and just one-third on the other side. This would allow me to sear the breasts over the coals and then move them to the cooler side to avoid burning when I applied the glaze.

My real challenge was to figure out how to speed up browning, also known as the Maillard reaction, and the consequent formation of all those new flavor compounds that help meat taste rich and complex. If the chicken browned faster, it would leave me more time to build a thick glaze that would add even more flavor. My first thought was to enlist the aid of starch in absorbing some of the moisture on the exterior of the meat that normally would need to burn off before much browning could occur. First I tried dredging the breasts in flour, but this made them bready. Next I tried cornstarch, but this approach turned the breasts gummy. A technique we have employed when pan-searing chicken breasts—creating an artificial “skin” using a paste of cornstarch, flour, and melted butter—gave us better results. The starches (which break down into sugars) and the butter proteins helped achieve a browned surface more quickly, and the porous surface readily held a glaze. Unfortunately, the chicken still tasted more breaded than grilled.

Switching gears, I tried rubbing the surface of the chicken with baking soda. Baking soda increases the pH of the chicken, making it more alkaline, which in turn speeds up the Maillard reaction. Alas, while this did speed up browning, even small amounts left behind a mild soapy aftertaste.

I was unsure of what to do next. But then I remembered a really unlikely sounding test that one of my colleagues tried when attempting to expedite the browning of pork chops: dredging the meat in nonfat dry milk powder. While this strange coating did brown the meat more quickly, it made the chops taste too sweet. But might it be better suited for browning chicken? It was worth a try. After lightly dusting the breasts with milk powder (½ teaspoon per breast) and lightly spraying them with vegetable oil spray to help ensure that the powder stuck, I threw them on the grill. I was thrilled when the chicken was lightly browned and had nice grill marks in less than 2 minutes, or about half of the time of my most successful previous tests. Why was milk powder so effective? It turns out that dry milk contains about 36 percent protein. But it also contains about 50 percent lactose, a so-called reducing sugar. And the Maillard reaction takes place only after large proteins break down into amino acids and react with certain types of sugars—reducing sugars like glucose, fructose, and lactose. In sum, milk powder contained just the two components that I needed to speed things up.

Milk powder encourages browning and creates a tacky surface for the flavorful glaze to cling to.

But that wasn’t the only reason milk powder was so successful in quickly triggering browning. Like starch, it’s a dry substance that absorbs the excess moisture on the meat. This is helpful because moisture keeps the temperature too low for significant browning to take place until the wetness evaporates. There was yet one more benefit to using the milk powder: It created a thin, tacky surface that was perfect for holding on to the glaze. And now, with expedited browning in place, I had time to thoroughly lacquer my chicken with glaze by applying four solid coats before it finished cooking.

GREAT GLAZE

Next it was time to focus on perfecting the glaze itself. I started with flavor. Since I knew that I wanted to limit the amount of sweetness so as not to overpower the mild flavor of the chicken, I began by testing a host of ingredients that would be thick enough to serve as a clingy base but weren’t sugary. It was a diverse group, but I settled on mustard and hoisin sauce. Then, in order to add balance and complexity, I introduced acidity in the form of vinegar, as well as a healthy dose of spices and aromatics, such as ground fennel seeds, fresh ginger, and spicy Sriracha sauce.

My next step was to add a sweet (but not too sweet) element, which would provide further balance, promote browning, and give even more of a sticky cling to the glaze. Sweeteners like maple syrup, brown sugar, and fruit jams made the glazes saccharine. Corn syrup, which is about half as sweet as the other sweeteners, worked far better, giving the glaze just a goodly amount of stickiness while keeping the sweetness level under control. Two tablespoons was just the right amount.

But all was not perfect: The glazes still had a tendency to become too loose when applied to the hot chicken after it browned. Whisking in a teaspoon of cornstarch helped.

At this point I was feeling pretty good. But many tasters wanted an even thicker glaze. This time I looked to adjust my cooking technique. My fix? I switched up the point at which I applied the glaze. Instead of brushing it on right before flipping the chicken, I began to apply the glaze immediately after it was flipped. This meant that less glaze stuck to the grill—and the glaze applied to the top of the chicken had time to dry out and cling. The result? Chicken breasts robed in a thick, lacquered glaze. My dinner was ready.

Grilled Glazed Boneless, Skinless Chicken Breasts

SERVES 4

¼ cup salt

¼ cup sugar

4 (6- to 8-ounce) boneless, skinless chicken breasts, trimmed

2 teaspoons nonfat dry milk powder

¼ teaspoon pepper

Vegetable oil spray

1 recipe glaze (recipes follow)

1. Dissolve salt and sugar in 1½ quarts cold water. Submerge chicken in brine, cover, and refrigerate for at least 30 minutes or up to 1 hour. Remove chicken from brine and pat dry with paper towels. Combine milk powder and pepper in bowl.

2A. For a charcoal grill: Open bottom vent completely. Light large chimney starter mounded with charcoal briquettes (7 quarts). When top coals are partially covered with ash, pour two-thirds evenly over half of grill, then pour remaining coals over other half of grill. Set cooking grate in place, cover, and open lid vent completely. Heat grill until hot, about 5 minutes.

2B. For a gas grill: Turn all burners to high, cover, and heat grill until hot, about 15 minutes. Leave primary burner on high and turn other burner(s) to medium-high.

3. Clean and oil cooking grate. Sprinkle half of milk powder mixture over 1 side of chicken. Lightly spray coated side of chicken with oil spray until milk powder is moistened. Flip chicken and sprinkle remaining milk powder mixture over second side. Lightly spray with oil spray.

4. Place chicken, skinned side down, over hotter part of grill and cook until browned on first side, 2 to 2½ minutes. Flip chicken, brush with 2 tablespoons glaze, and cook until browned on second side, 2 to 2½ minutes. Flip chicken, move to cooler side of grill, brush with 2 tablespoons glaze, and cook for 2 minutes. Repeat flipping and brushing 2 more times, cooking for 2 minutes on each side. Flip chicken, brush with remaining glaze, and cook until chicken registers 160 degrees, 1 to 3 minutes. Transfer chicken to plate and let rest for 5 minutes before serving.

glazes

MAKES ABOUT ⅔ CUP

2 tablespoons cider vinegar

1 teaspoon cornstarch

3 tablespoons Dijon mustard

3 tablespoons honey

2 tablespoons light corn syrup

1 garlic clove, minced

¼ teaspoon ground fennel seeds

Whisk vinegar and cornstarch in small saucepan until cornstarch has dissolved. Whisk in mustard, honey, corn syrup, garlic, and fennel seeds. Bring mixture to boil over high heat. Cook, stirring constantly, until thickened, about 1 minute. Transfer glaze to bowl.

MAKES ABOUT ⅔ CUP

For a spicier glaze, use the larger amount of Sriracha sauce.

2 tablespoons rice vinegar

1 teaspoon cornstarch

⅓ cup hoisin sauce

2 tablespoons light corn syrup

1–2 tablespoons Sriracha sauce

1 teaspoon grated fresh ginger

¼ teaspoon five-spice powder

Whisk vinegar and cornstarch in small saucepan until cornstarch has dissolved. Whisk in hoisin, corn syrup, Sriracha, ginger, and five-spice powder. Bring mixture to boil over high heat. Cook, stirring constantly, until thickened, about 1 minute. Transfer glaze to bowl.

THE POWER OF MILK POWDER

To make sure that our chicken breasts could be both browned and glazed in the time it took the chicken to cook, we had to accelerate browning. A surprising ingredient—milk powder—was the solution. Milk powder contains both protein and so-called reducing sugar (in this case, lactose), the keys to the Maillard reaction, the chemical process that causes browning. Faster browning gave us more time to layer on the glaze.

BROWNING BOOSTER

I’ve been watching my father grill for almost 40 years now. He’s at least fifth generation Deep South—not the kind of man who would fire up his grill for some wimpy pizza, mahi-mahi, or basket of vegetables. For as long as I can remember, he’s been grilling the same four things—steak, spareribs, barbecued pork butt, and finally, his signature dish, lemon chicken.

My father is a pretty confident griller, but that lemon chicken turned him into a nervous Nelly. Every time he made it he was obsessed with the same goal: to make sure that it absorbed as much lemon flavor as possible. After he’d arranged the chicken parts neatly over the hot coals, he would brush each one with a mixture of lemon, oil, and garlic salt. He basted meticulously throughout the entire grilling process, carefully moving the chicken around and over to make sure each piece cooked evenly.

Dad almost dreaded taking that first bite for fear the lemon had not penetrated. Though we sometimes had to stretch the truth, Mom and I always assured him that it had. When the chicken was at its best, we marveled: “The lemon flavor’s gone right into the bone!”

Because Dad felt his odds on whether the lemon would take or not were about fifty-fifty, he’d have me taste-test the chicken before he took it off the grill. About halfway through cooking, he’d start breaking off and feeding me the wings. Even though I always told him they tasted lemony enough, he could read the truth in my eyes. (You can never trust a hungry 10-year-old who’s been sitting still with her father for over an hour.) The grill lid would fly open, and he’d begin his basting again, hoping his fire would stay alive long enough to get a few more drops of lemon sauce onto the chicken.

Dipping the chicken in the leftover lemon basting sauce was always one of my favorite ways of ensuring good lemon flavor (salmonella was just a twinkle in the chicken’s eye back then), but to Dad it meant failure. When he saw me sneak the leftover sauce to the table and slip a piece of my breast meat into the bowl, he’d start mentally kicking himself.

He tried a number of experiments over the years, but it wasn’t until long after I’d left home that he called, his voice veering high with excitement. “I’ve finally discovered the secret to lemon chicken!” he exclaimed. It turned out that one day while frying fish, his oil cooled off and was absorbed by the fish. At this point, it suddenly occurred to him that over lower heat his cooked chicken might better absorb his lemon sauce. What was bad for the fish in oil, might be good for the chicken in lemon sauce.

This time, rather than baste the chicken from start to finish, he threw the salt-and-peppered chicken parts on the grill and cooked them until they were virtually done. At this point, he took the fire down really low and started brushing them. This, he said, consistently gave him the intense lemon flavor he was after. After 40 years, he had finally come up with a foolproof method.

HE WAS RIGHT

I gave Dad’s technique a try and realized he was onto something. I liked the fresh, perky lemon flavor of the chicken sauced at the end, but I couldn’t really be sure that it was better than his many lemon chicken experiments over the years. Which lemon chicken was best? Was it the one where the lemon mixture was applied before, during, or after cooking? So I grilled three chickens—one that was marinated in lemon juice, garlic, and oil for two hours, a second that was basted with the same mixture throughout grilling, and a third that was grilled by my father’s method, rolling the cooked chicken around in the lemon mixture, returning it to the grill, and basting it for a few minutes longer. With each chicken, I used a two-level fire, with most of the coals under half of the cooking grate and fewer coals under the remaining half. This allowed me to sear the chicken well over the coals but also to regulate its cooking, moving it to the cooler area if it was cooking too quickly or if flare-ups occurred.

If you weren’t comparing them with my father’s newly discovered secret, you’d say the marinated and basted chickens were just fine. The chicken flavored at the end, however, stole the show. Not only did it have a fresher flavor, its juices had mingled with the lemon, garlic, and oil to make a wonderful sauce. The basted chicken, on the other hand, had lost much of its lemon juice to the fire, requiring more lemon mixture to complete the job, and even with more sauce, it turned out drier than the other two.

My dad’s technique became my favorite, especially after I made a few personal adjustments. First, I almost always brine poultry before cooking it, and brined lemon chicken was always preferred to unbrined in side-by-side tasting. Since brining made garlic salt out of the question, I tried using minced garlic, but because the chicken was on the grill for such a relatively short time after the marinade was applied, it tasted raw. I eventually found that mincing the garlic to almost a paste and warming it in a small saucepan until it began to sizzle improved the garlic flavor immensely.

Although my father would never consider doctoring up his chicken, I thought herbs such as thyme, cilantro, rosemary, and oregano and spices such as cumin, coriander, and fennel might be nice additions. Herbs were easy. They could be stirred directly into the lemon mixture. But spices were questionable. Would they, like the garlic, taste raw with so little cooking time and over so low a heat?

Once again, I made three batches of chicken—one that was rubbed with crushed coriander seeds before cooking; a second that was brushed at the end with a marinade containing crushed coriander seeds; and a third that was brushed with a marinade containing toasted, then crushed coriander seeds. My tasters and I much preferred the last, where toasted seeds were crushed, stirred into the marinade, and applied at the end. The spices that cooked on the chicken the entire time were less flavorful and tended to char. And besides, toasted seeds, like toasted nuts, just taste better.