FISH AND SHELLFISH

Introducing Grill-Smoked Salmon

Building a Better Shrimp Cocktail

FISH EN PAPILLOTE

KEITH DRESSER, March/April 2009

Cooking en papillote—where the food is baked in a tightly sealed, artfully folded parchment package to essentially steam in its own juices—may seem as outdated as Beef Wellington and Pheasant under Glass. But there’s a reason the technique has held its own through countless culinary fads and fashions. It’s an easy, mess-free way to enhance delicate flavor, particularly that of fish, leaving no odors to linger in the kitchen. The fish cooks quickly in such a moist environment, and because there’s no water added to dilute flavors, it’s a more flavorful method than ordinary poaching. It requires little additional fat and, if you throw in vegetables, adds up to a light but satisfying “one-pouch” meal.

When done correctly, that is. Without the right blend of flavorings, the fish can taste so lean and bland, you might as well be dining on diet food. Not all vegetables pair well with fish, and careful consideration must be given to their size and whether precooking is necessary, or you can wind up with overcooked fish surrounded by undercooked vegetables. I wanted to create an approach worthy of this technique’s haute roots, with moist, flaky fish and tender-firm vegetables flavored by the rich, aromatic goodness of their mingled juices.

FOILED AGAIN

All the classic recipes call for cutting parchment paper into attractive shapes such as teardrops, hearts, and butterflies, then creasing the seams into painstakingly precise little folds. But just looking at the illustrations made my thumbs throb. I wanted to get dinner on the table as quickly as possible—not create origami. I went directly to aluminum foil, sandwiching the fish between two 12-inch squares and crimping the edges to create an airtight seal that would lock in steam. This was admittedly not as glamorous as an intricately folded parchment packet, but definitely serviceable.

My next step was to figure out what type of fish worked best in this dish and how long it would take to cook. After trying a variety of fish fillets, I quickly determined that tasters favored flaky, mild fish like haddock and cod over more assertively flavored fish like salmon or tuna. In the moist atmosphere of the foil pouch, these oilier fish had a tendency to overpower the flavors of the vegetables (for the moment I was simply placing the fish on a bed of sliced zucchini); better to save them for sautéing or searing.

We use foil, not parchment paper, and the right blend of vegetables and flavorings to create a satisfying one-pouch meal.

Since the goal of cooking en papillote is to create enough steam from the food’s own juices, most recipes recommended cranking the heat way up, even as high as 500 degrees. Though a wet method like this one is more forgiving than a dry approach like roasting, 500 degrees seemed excessive. And it was. When I opened the foil after just 15 minutes for a “nick and peek,” my 1-inch fillets were chalky white and well-done (and the zucchini was slightly underdone). Cooking at this temperature for less time didn’t work either—the food was barely in the oven long enough for steam to form, leaving both fish and vegetable undercooked. After more experimentation, I arrived at 450 degrees for 15 minutes as the ideal temperature and cooking time—hot enough to produce steam relatively quickly but not so hot that the food overcooked. Placing the packets on the lower-middle rack of the oven, close to the heat source, helped concentrate the exuded liquid and deepen its flavor.

VEGGIN’ OUT

With the cooking time and temperature nailed down, I could now turn my attention to selecting the vegetables. I quickly winnowed my options. Dense vegetables such as potatoes, even when parcooked, failed to cook evenly in the foil packets. Vegetables with an absorbent structure, like eggplant, simply cooked into mush in all the moisture. Others, such as broccoli, overpowered the delicate fish flavor. Beyond these considerations, the most important aspect was how the vegetables were prepared before they went into the packets. I found that carrots and leeks could be added to the packets raw, provided they were cut into matchsticks. The zucchini was much improved—and the juices in the packet less diluted—if I salted it first to get rid of excess moisture.

While tasters liked these fish and vegetable pairings, many felt that the components lacked harmony and overall the dish tasted a little too lean. A dash of vermouth, which was absorbed by the fish and vegetables, boosted flavor but not quite enough. What if I created a topping to flavor the fish as it cooked? A tomato, garlic, and olive oil “salsa” added kick to my zucchini variation, while a compound butter flavored with garlic, herbs, and zest enlivened the main recipe. These toppings basted the fish as it cooked and mingled with the wine and juices given off by the vegetables, leaving behind an aromatic, full-flavored sauce that perfectly complemented the fish. Each recipe was so light, fresh, and easy to prepare, it couldn’t be more contemporary.

Cod Baked in Foil with Leeks and Carrots

SERVES 4

Haddock, red snapper, halibut, and sea bass also work well in this recipe as long as the fillets are 1 to 1¼ inches thick. Open each packet promptly after baking to prevent overcooking, and make sure to open packets away from you to avoid steam burns.

4 tablespoons unsalted butter, softened

2 garlic cloves, minced

1¼ teaspoons finely grated lemon zest, plus lemon wedges for serving

1 teaspoon minced fresh thyme

Salt and pepper

2 tablespoons minced fresh parsley

2 leeks, white and light green parts only, cut into 2-inch-long segments, halved lengthwise, washed thoroughly, and cut into ⅛-inch-thick matchsticks

2 carrots, peeled and cut into 2-inch-long matchsticks

¼ cup dry vermouth or dry white wine

4 (6- to 8-ounce) skinless cod fillets, 1 to 1¼ inches thick

1. Combine butter, 1 teaspoon garlic, ¼ teaspoon lemon zest, thyme, ¼ teaspoon salt, and ⅛ teaspoon pepper in small bowl. Combine parsley, remaining garlic, and remaining 1 teaspoon lemon zest in second small bowl and set aside. Place leeks and carrots in medium bowl, season with salt and pepper, and toss to combine.

2. Adjust oven rack to lower-middle position and heat oven to 450 degrees. Cut eight 12-inch sheets of aluminum foil; arrange 4 sheets flat on counter. Divide leek-carrot mixture in center of foil sheets and sprinkle with vermouth. Pat cod dry with paper towels, season with salt and pepper, and place on top of vegetables. Divide butter mixture among fillets, spreading over top of each fillet. Place second foil sheet on top of cod, crimp edges together in ½-inch fold, then fold over 3 more times to create packet about 7 inches square. Place packets on rimmed baking sheet, overlapping slightly if necessary. (Packets can be refrigerated for up to 6 hours before baking. If packets are refrigerated for more than 30 minutes, increase cooking time by 2 minutes.)

3. Bake packets for 15 minutes, then transfer to individual plates. Open carefully (steam will escape) and, using metal spatula, gently slide contents onto plates, along with any accumulated juices. Sprinkle with parsley mixture. Serve immediately, passing lemon wedges separately.

variation

Cod Baked in Foil with Zucchini and Tomatoes

SERVES 4

1 pound zucchini, sliced ¼ inch thick

Salt and pepper

2 plum tomatoes, cored, seeded, and chopped

2 tablespoons extra-virgin olive oil

2 garlic cloves, minced

1 teaspoon minced fresh oregano

⅛ teaspoon red pepper flakes

¼ cup dry vermouth or dry white wine

4 (6- to 8-ounce) skinless cod fillets, 1 to 1¼ inches thick

¼ cup chopped fresh basil

Lemon wedges

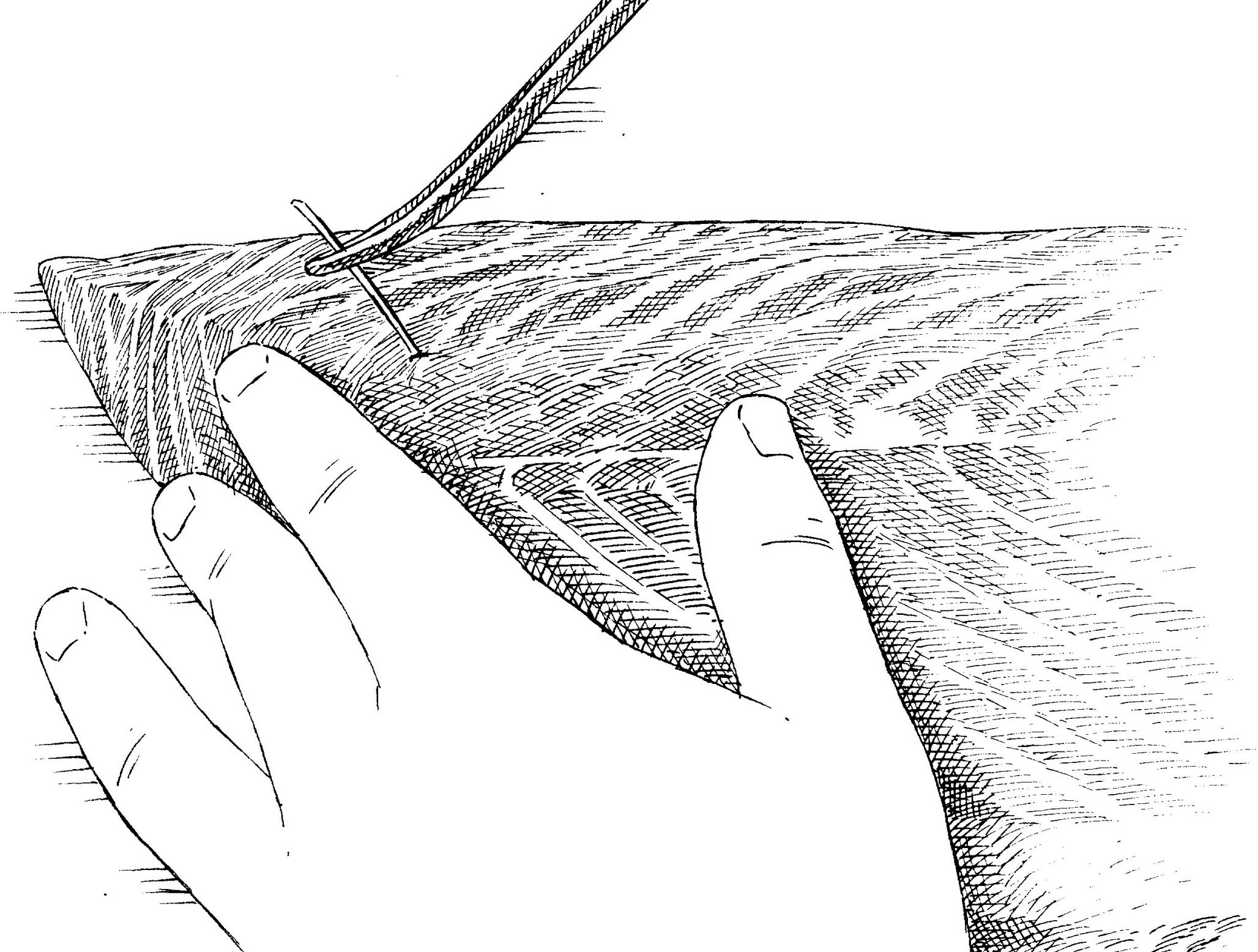

ASSEMBLING FOIL PACKETS

1. Arrange vegetables on foil first so they will be closest to heat source; drizzle with vermouth to deepen flavor. Top vegetables with fish and spread compound butter or topping over it for increased richness.

2. Top with second piece of foil and crimp edges together in ½-inch fold, then fold over 3 more times to create airtight packet about 7 inches square.

1. Toss zucchini with ½ teaspoon salt in bowl, transfer to colander, and let sit for 30 minutes. Pat zucchini dry thoroughly with paper towels, pressing firmly on each slice to remove as much liquid as possible. Meanwhile, combine tomatoes, oil, garlic, oregano, pepper flakes, ¼ teaspoon salt, and ⅛ teaspoon pepper in bowl.

2. Adjust oven rack to lower-middle position and heat oven to 450 degrees. Cut eight 12-inch sheets of aluminum foil; arrange 4 flat on counter. Shingle zucchini in center of foil sheets and sprinkle with vermouth. Pat cod dry with paper towels, season with salt and pepper, and place on top of zucchini. Spread tomato mixture over fish. Place second foil sheet on top of cod, crimp edges together in ½-inch fold, then fold over 3 more times to create packet about 7 inches square. Place packets on rimmed baking sheet, overlapping slightly if necessary.

3. Bake packets for 15 minutes, then transfer to individual plates. Open carefully (steam will escape) and, using metal spatula, gently slide contents onto plates, along with any accumulated juices. Sprinkle with basil and serve immediately, passing lemon wedges separately.

A BETTER WAY TO POACH FISH

DAN SOUZA, March/April 2012

If your experience with poached fish is limited to the lean, bland preparation you might be served at a wedding or a weight-loss spa, a technique popular at high-end restaurants will permanently change your perception—and serve as a reminder as to why poaching became a classic approach to cooking fish in the first place. The key perk: Submerging fish in liquid and gently cooking it at below simmer temperatures—anywhere from 130 to 180 degrees—renders the delicate flesh silky and supple. In this case, however, there is one major amendment to the technique that elevates it above the usual poached fish: Rather than the usual lean bath of water, wine, broth, or some combination thereof, the poaching liquid is olive oil.

On paper, cooking delicate fish fillets in a pot of fat sounds like a greasy recipe for disaster, but when I tried it the results were stunning—lighter, moister, and more fragrant than any traditionally poached fish I’d ever tasted—and they explained why this technique has become so popular in top restaurants. Another plus: The flavor-infused poaching oil can be whirred into a rich, glossy emulsion and drizzled over the fish as a sauce. The dish, I realized, would make elegant fare, provided I could get around one obvious challenge: the cost—and mess—of heating up a large amount of olive oil for just one meal. I would have to figure out how to scale the oil way back.

OIL EMBARGO

My first decision was to go with skinless fillets since the oil would never get hot enough to crisp the skin. I settled on cod for its firm, meaty flesh and clean flavor. As for the amount of oil, I reasoned that the smaller the surface area of the cooking vessel, the deeper the liquid would pool, so I reached past my trusty 12-inch nonstick skillet for its 10-inch sibling. Unfortunately, this setup still demanded about 1½ cups of oil to cover the four 6-ounce fillets. My only other idea was to displace some of the oil by placing half an onion in the skillet and arranging the fillets around it—a trick that worked but got me down only another ¼ cup. Clearly, I needed a more drastic solution.

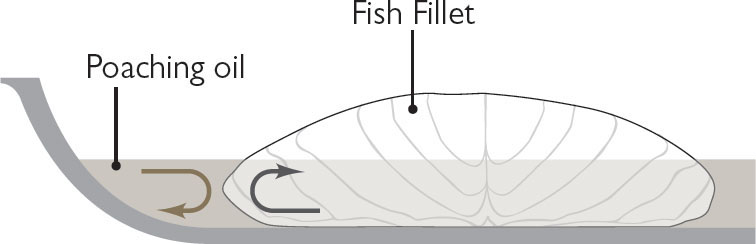

That’s when I started to wonder if completely immersing the fillets in oil was necessary. The alternative—pouring enough oil into the pan to come roughly halfway up the sides of the fish (about ¾ cup)—would mean flipping the fish partway through poaching to ensure that it cooked through. But that seemed a small price to pay for significantly cutting my oil dependence. I gave it a shot, basting the exposed half of each fillet with a few spoonfuls of oil (to prevent evaporation), popping a lid on the pan, and placing the skillet over the lowest burner setting. The good news was that the method worked; the fillets were supremely moist and tender—considerably more so than any water-poached fish, and not at all oily.

The bad news was that it was fussy. With relatively little oil in the pan, the temperature spiked quickly and required that I constantly fiddle with the burner knob to keep the oil in my target range (140 to 150 degrees), which would slowly bring my fish to an ideal internal temperature of 130 degrees, with little risk of going over. Placing a homemade heat diffuser fashioned from a ring of aluminum foil over the burner didn’t reliably tame the flame. What I needed was a steadier, less-direct heat source, and for that I turned to the oven.

I figured that I could simply bring the oil to 140 degrees on the stovetop, slip in the fish, and then transfer the skillet into a low oven. But it wasn’t quite that easy; the oil temperature immediately plummeted when I added the still-cold fillets, and the temperature recovery time in the oven was slow. But I had an idea: I’d heat the oil on the stovetop to well above my target temperature and then rely on the oven’s more-even heat to keep it in the poaching sweet spot.

After a slew of tests, I hit upon a winning combination: Heat the oil to 180 degrees, nestle in the fillets (each sprinkled with kosher salt), and set the pan in a 250-degree oven. The oil temperature recovered within 15 minutes, by which point the lower half of the fish was cooked. I flipped the fillets, replaced the lid, and returned them to the oven. This batch emerged incredibly moist and velvety, and thanks to my oven method, the process was now largely hands-off. What I had was good—but I wanted to make it even better.

CRUNCH TIME

We often salt meat and allow it to rest before cooking, both to enhance juiciness and to bring seasoning deep into the interior. Why not try this with fish? For my next round of testing, I salted the fillets about 20 minutes before cooking. This technique worked beautifully: Moisture beaded on the surface of the fish, where it dissolved the salt and created a concentrated brine that was eventually absorbed back into the flesh to bolster flavor.

I also wanted something that could serve as a textural contrast to the silky fish. Restaurants often garnish their oil-poached fillets with lightly fried vegetables and fresh herbs, and I reasoned that I could approximate that by crisping something in the oil before cooking the fish. Fried artichoke hearts have always been a favorite of mine, so I defrosted a bag of them, patted them dry, and halved them lengthwise before tossing them with cornstarch (for extra crunch) and dropping them into the shimmering oil with some minced garlic.

Tasters loved the crisp garnish, but after cranking up the heat to fry, I then had to wait more than 10 minutes for the oil to cool to my target of 180 degrees before the pan went into the oven. The solution proved easy: Rather than dump in all the oil at once, I’d fry the garnishes in ½ cup of oil, strain it, and add the remaining ¼ cup of room temperature oil to the pan to speed the cooling. The tweak made all the difference; about 5 minutes after frying, the oil was cool enough for poaching.

DRESSED TO IMPRESS

Frying up a garnish had also left me with an added bonus: flavor-infused oil to use for a sauce. I poured ½ cup into the blender and whirred it with whole cherry tomatoes (for bright sweetness), half a shallot, sherry vinegar, and salt and pepper. After a quick spin on high speed and a pass through a fine-mesh strainer, I had a silky-smooth vinaigrette.

Dressed up with the sauce, the crispy artichoke garnish, a few slices of fresh cherry tomato, and a sprinkle of chopped parsley, my elegant plate was complete—not to mention plenty simple to pull off at home.

Poached Fish Fillets with Sherry-Tomato Vinaigrette

SERVES 4

Fillets of meaty white fish such as cod, halibut, sea bass, or snapper work best in this recipe. Make sure the fillets are at least 1 inch thick. A neutral oil such as canola can be substituted for the pure olive oil. A 4-ounce porcelain ramekin can be used in place of the onion half in step 3. Serve with couscous or steamed white rice.

Fish

4 (6-ounce) skinless white fish fillets, 1 inch thick

Kosher salt

4 ounces frozen artichoke hearts, thawed, patted dry, and sliced in half lengthwise

1 tablespoon cornstarch

¾ cup olive oil

3 garlic cloves, minced

½ onion, peeled

Vinaigrette

4 ounces cherry tomatoes

½ small shallot, peeled

4 teaspoons sherry vinegar

Kosher salt and pepper

1 tablespoon minced fresh parsley

2 ounces cherry tomatoes, cut into ⅛-inch-thick rounds

1. For the fish: Adjust oven racks to middle and lower-middle positions and heat oven to 250 degrees. Pat fish dry with paper towels and season each fillet with ¼ teaspoon salt. Let sit at room temperature for 20 minutes.

2. Meanwhile, toss artichokes with cornstarch in bowl to coat. Heat ½ cup oil in 10-inch nonstick ovensafe skillet over medium heat until shimmering. Shake excess cornstarch from artichokes and add to skillet; cook, stirring occasionally, until crisp and golden, 2 to 4 minutes. Add garlic and continue to cook until garlic is golden, 30 to 60 seconds. Strain oil through fine-mesh strainer into bowl. Transfer artichokes and garlic to ovensafe paper towel–lined plate and season with salt. Do not wash strainer.

3. Return strained oil to skillet and add remaining ¼ cup oil. Place onion half in center of pan. Let oil cool until it registers about 180 degrees, 5 to 8 minutes. Arrange fish fillets, skinned side up, around onion (oil should come roughly halfway up fillets). Spoon a little oil over each fillet, cover skillet, transfer to upper rack, and cook for 15 minutes.

4. Remove skillet from oven. Using 2 spatulas, carefully flip fillets. Cover skillet, return to upper rack, and place plate with artichokes and garlic on lower rack. Continue to cook fish until it registers 130 to 135 degrees, 9 to 14 minutes longer. Gently transfer fish to serving platter, reserving ½ cup oil, and tent fish with aluminum foil. Turn off oven, leaving plate of artichokes in oven.

5. For the vinaigrette: Process cherry tomatoes, shallot, vinegar, ¾ teaspoon salt, and ½ teaspoon pepper with reserved ½ cup fish cooking oil in blender until smooth, 1 to 2 minutes. Add any accumulated fish juices from platter, season with salt to taste, and blend for 10 seconds. Strain sauce through fine-mesh strainer; discard solids.

6. To serve, pour vinaigrette around and over fish. Garnish each fillet with warmed crisped artichokes and garlic, parsley, and tomato rounds. Serve immediately.

variation

Poached Fish Fillets with Miso-Ginger Vinaigrette

For fish, substitute 8 scallion whites, sliced ¼ inch thick, for artichoke hearts; omit garlic; and reduce amount of cornstarch to 2 teaspoons. For vinaigrette, process 6 scallion greens, 8 teaspoons lime juice, 2 tablespoons mirin, 4 teaspoons white miso paste, 2 teaspoons minced fresh ginger, and ½ teaspoon sugar with ½ cup fish cooking oil as directed in step 5. Garnish fish with 2 thinly sliced scallion greens and 2 halved and thinly sliced radishes.

WHY POACH IN OIL?

Poaching in oil allows fish to retain more of its juices than poaching in wine or broth, leading to remarkably moist, velvety results. This is because cooking in oil is inherently more gentle than cooking in water. And while you might expect that fish poached in fat would be greasy, it actually absorbs very little oil. Why? In order for oil to penetrate the fish, moisture must exit first. But because oil and water repel each other, it’s very difficult for moisture inside the fish to readily enter the oil. Hence, more of the juices stay in the fish. In fact, in our tests, oil-poached fish lost just 14 percent of its weight during cooking, while water-poached fillets lost 24 percent.

OIL AND WATER DON’T MIX

Poached salmon seems like the ideal stovetop recipe: It’s fast, it requires just one pot, and there’s no splattering oil to burn yourself on or strong odors to permeate the house. And, when done right, the fish has an irresistibly supple, velvety texture delicately accented by the flavors of the poaching liquid. Add a simple sauce and the dish is even more flavorful. But when done wrong, which seems to be the usual case, the fish has a dry, chalky texture and washed-out taste that not even the richest sauce can redeem.

The classic method for poaching salmon is to gently simmer an entire side of fish in a highly flavored broth called a court-bouillon. The salmon is cooled and served cold, often as part of a buffet. But I wasn’t looking for a make-ahead method for cold salmon to serve a crowd. I wanted to produce perfectly cooked, individual portions of hot salmon and a sauce to go with them—all in under half an hour.

FINESSING FLAVOR

My first objective was to achieve great texture and flavor in the salmon itself; after that I’d focus on the sauce. First consideration: the cooking liquid. A classic court-bouillon is made by filling a pot with water, wine, herbs, vegetables, and aromatics and boiling it all very briefly (court-bouillon is French for “short-boiled stock”). After straining the solids, you’re left with an intensely flavored liquid in which to poach your fish. The broth’s strong flavors are absorbed by the fish, which helps compensate for all the salmon flavor that leaches out into the liquid.

For velvety poached salmon, we use a small amount of liquid and elevate the fish on lemon slices.

This method certainly did produce flavorful results. However, there was just one annoying little problem: To cook dinner for four, I’d just prepped a slew of ingredients (onions, carrots, celery, leeks, parsley) and bought still others (bay leaves, tomato paste, peppercorns, and white wine), only to dump them and the stock down the drain at the end. This waste isn’t bothersome when you’re preparing a side of fish to feed a group, but it’s hardly worth it for a simple Tuesday night supper at home.

What if I used less liquid? At the very least, this would mean I’d have to buy and prep (and waste) fewer ingredients; plus, using less liquid would likely mean less flavor leaching out of the salmon. I poached the salmon in just enough liquid to come half an inch up the side of the fillets. Flavor-wise, this was my most successful attempt yet. In fact, the salmon retained so much of its own natural flavor that I wondered if I could cut back even more on the quantity of vegetables and aromatics I was using in the liquid. A couple of shallots, a few herbs, and some wine proved to be all I needed. But nailing the flavor issue brought another problem into sharp relief—dry texture.

SEEKING SUPPLE TEXTURE

Like all animal flesh, salmon has a certain temperature range at which it is ideal to eat. The proteins in salmon begin coagulating at around 120 degrees, transforming it from translucent to opaque. At around 135 degrees, the flesh is completely firm and will start to force moisture out from between its protein fibers. Any higher, and the salmon becomes dry as cardboard (like a well-done steak). I had been using an instant-read thermometer to ensure that the centers of my salmon fillets were exactly 125 degrees (medium) before removing them from the poaching liquid. But testing the temperature of various parts of the fillet showed that by the time the center was 125 degrees, most of the other thinner sections registered higher temperatures. I was concerned that the texture of these thinner areas would be dry, but found their higher fat content kept them moist.

With high cooking temperatures, the exterior of a piece of meat will cook much faster than the interior. This is great when pan-searing the skin of a salmon fillet or a beef steak, when you want a browned exterior and rare interior, but it’s no good for poaching, where the goal is to have an evenly cooked piece all the way through. The most obvious solution was to lower the cooking temperature. For the next batch, I placed the salmon in the cold pan with poaching liquid and brought the liquid barely up to a simmer, then reduced the heat to its lowest possible setting and covered the pan until the salmon cooked through. Then I realized a new problem that I’d unwittingly introduced when I reduced the amount of cooking liquid: Since the salmon wasn’t totally submerged in liquid, it relied on steam to deliver heat and flavor. At such a low temperature, even with a lid on, not enough steam was being created to efficiently cook the parts of the fish sticking out above the liquid. Was there a way to create more steam without increasing the temperature?

Thinking back to high school chemistry, I remembered that adding alcohol to water lowers its boiling temperature: The higher the concentration of alcohol, the more vapor will be produced as the liquid is heated. More vapor, in turn, means better heat transfer, which leads to faster cooking, even at temperatures below a simmer. I also knew that alcohol could increase the rate at which proteins denature. Therefore, if I used more alcohol in the cooking liquid, it would theoretically be able to cook the fish faster and at a lower temperature. I increased the ratio of wine to water, going from a few tablespoons of wine to ½ cup. Acid also helps fish protein denature (in addition to improving flavor), so I squeezed a little lemon juice into the liquid before adding the salmon. My hopes were high as I opened the lid to a burst of steam and salmon that appeared perfectly cooked. Everything was fine until my fork got to the bottom of the fillet. Even though the top, sides, and center were now just right, the bottom, which had been in direct contact with the pan, was still overcooked.

I knew I wasn’t the first person to ever have this problem—in fact, a solution already exists: a fish poacher. This specialized pan comes with a perforated insert that elevates the fish, allowing it to cook evenly on all sides. But I wasn’t about to go out and buy an expensive new pan for a technique that I’d only use a few times a year. Then I realized that I had the solution literally in my hand. Instead of squeezing lemon juice into the poaching liquid, I sliced the fruit into thin disks and lined the pan with them. By resting the salmon fillets on top of the lemon slices, I was able to insulate the fish from the pan bottom while simultaneously flavoring it. This time the salmon came out evenly cooked all the way through.

SETTLING THE SAUCE

It was time to focus on the sauce. Ticking off the list of ingredients in my super-concentrated poaching liquid, I realized I had the foundation of a beurre blanc, so I didn’t have to make a separate sauce. This classic French sauce is made by reducing wine flavored with vinegar, shallots, and herbs and then finishing it with butter. I would need only to reduce my poaching liquid and whisk in the butter. But since a few tablespoons of butter per serving would push this dish out of the “everyday” category, I developed a vinaigrette-style variation in which I used olive oil instead of butter; tasters liked the oil version as much as the original.

This salmon-poaching method guarantees moist and delicately flavored fish and produces just the right amount of poaching liquid for a great-tasting sauce—all without boiling away any flavor or pouring ingredients down the drain.

Poached Salmon with Herb and Caper Vinaigrette

SERVES 4

To ensure uniform pieces of salmon that cook at the same rate, buy a whole center-cut fillet and cut it into four pieces. If a skinless whole fillet is unavailable, remove the skin yourself or follow the recipe as directed with a skin-on fillet, adding 3 to 4 minutes to the cooking time in step 2. This recipe will yield salmon fillets cooked to medium-rare.

2 lemons

2 tablespoons chopped fresh parsley, stems reserved

2 tablespoons chopped fresh tarragon, stems reserved

1 large shallot, minced

½ cup dry white wine

½ cup water

1 (1¾- to 2-pound) skinless salmon fillet, about 1½ inches thick

2 tablespoons capers, rinsed and chopped

2 tablespoons extra-virgin olive oil

1 tablespoon honey

Salt and pepper

1. Line plate with paper towels. Cut top and bottom off 1 lemon, then cut into eight to ten ¼-inch-thick slices. Cut remaining lemon into 8 wedges and set aside. Arrange lemon slices in single layer across bottom of 12-inch skillet. Scatter herb stems and 2 tablespoons minced shallot evenly over lemon slices. Add wine and water to skillet.

2. Use sharp knife to remove any whitish fat from belly of salmon and cut fillet into 4 equal pieces. Place salmon fillets in skillet, skinned side down, on top of lemon slices. Set pan over high heat and bring liquid to simmer. Reduce heat to low, cover, and cook until sides are opaque but center of thickest part of fillet is still translucent when checked with tip of paring knife and registers 125 degrees (for medium-rare), 11 to 16 minutes. Off heat, use spatula to carefully transfer salmon and lemon slices to prepared plate and tent with aluminum foil.

3. Return pan to high heat and simmer cooking liquid until slightly thickened and reduced to 2 tablespoons, 4 to 5 minutes. Meanwhile, combine capers, oil, honey, chopped parsley and tarragon, and remaining minced shallot in medium bowl. Strain reduced cooking liquid through fine-mesh strainer into bowl with herb mixture, pressing on solids to extract as much liquid as possible. Whisk to combine and season with salt and pepper to taste.

4. Season salmon with salt and pepper to taste. Using spatula, carefully lift and tilt salmon fillets to remove lemon slices. Place salmon on serving platter or individual plates and spoon vinaigrette over top. Serve, passing lemon wedges separately.

A FISH (ALMOST) OUT OF WATER

Our improved poaching method produces salmon with better flavor and texture by using a lot less liquid.

STANDARD POACH

The classic poaching method calls for submerging salmon completely in liquid in a deep pan, which causes flavor to leach out and leads to dry, flavorless fish.

SHALLOW POACH

In our method, small amounts of liquid allow the salmon to cook at a lower temperature, preserving flavor. Lemon slices under the fillets keep their bottoms from overcooking.

Salmon is a surefire crowd-pleaser, but it’s not always easy to make for a crowd. Many cooks shy away from poaching, and our favorite indoor cooking method—pan-searing individual portions—can get cumbersome with too many pieces of fish. Our preferred outdoor cooking techniques—hot-smoking and straightforward grilling—can accommodate larger pieces of fish, but for denizens of the North, among whom we count ourselves, cooking outside is impractical, if not impossible, for almost half the year.

So we set out to beat the odds: to find the best way of cooking a whole side of salmon, enough to feed eight or more guests, in the oven. We wanted fish that was moist but not soggy, firm but not chalky, and nicely crusted, with golden, flavorful caramelization over its flesh. If we could work some interesting flavors and contrasting textures into the bargain, all the better.

CRUST IS KEY

Creating some flavorful caramelization on the flesh of the fish was a key goal, so we focused right away on high-heat cooking. Baking, though it seemed like a natural choice, was out because it implies cooking in a moderate, 350-degree oven, which would never brown the fish. Heating things up from there, we tested roasting at oven temperatures of 400, 450, and 500 degrees. To our surprise, none of them worked well. Even at 500 degrees on a preheated pan, the fish remained pale, owing to the necessarily short 16-minute cooking time (any more time in the oven and the fish would overcook). Another source of consternation was moisture—not the lack of it, as we might have expected, but an excess. The abundance of fat and collagen in the farmed Atlantic salmon we were using melted during cooking, giving the fish an overly wet, slippery texture and fatty mouthfeel.

Broiling was the next step up in heat, and here we met with some success. The salmon browned nicely under the intense broiler heat and, as a result, developed better flavor. Some of the copious moisture evaporated, leaving the fish with a much-improved texture, drier and firmer yet still juicy. None of the broiling and roasting combinations we went on to try topped broiling from start to finish. We were on the right track to be sure, but plain broiled salmon was not terribly inspiring. If we were going to serve this to a crowd of people at a weekend dinner party, a flavor boost and some textural interest would be absolutely necessary.

TOPPING ANTICS

The addition of an interesting topping for the fish could, we thought, achieve both goals. Dried bread crumbs came immediately to mind—and left almost as quickly once we tasted them. The flavor was lackluster and the texture akin to sawdust. Our favorite panko bread crumbs were judged too light in flavor and feathery in texture. Fresh bread crumbs were a crisp improvement, and toasted fresh bread crumbs laced with garlic, herbs, and butter were better still. But there were more avenues to explore. Dry spice rubs, similar to what we might apply to grilled fish, met with mixed results. Glazes and spice pastes won praise for their flavor, but since they were wet, they added little texture.

Potatoes were another topping possibility. Potato crusts on fish are typically engineered by laying paper-thin slices of potato on the fish and sautéing it on the stovetop. Testing proved that the slices would not form a cohesive crust without the direct heat of a hot pan. In addition, we couldn’t slice them thin enough without the help of a mandoline. But because tasters loved the potato flavor, we tried some other methods. A crust of grated raw potatoes remained too loose and crunchy. Sautéing the grated potato before applying it to the fish helped some, but not enough, while completely precooking the potatoes robbed them of both flavor and texture.

We use crushed potato chips for an ultracrisp crust, and wait until partway through broiling to add them so they don’t burn.

As we clung tenaciously to the notion of potato flavor while groping for another way to build a crisp, crunchy texture, a fellow test cook smirked and suggested, half in jest, that we try crushed potato chips. Everyone in the test kitchen at the time laughed, but after settling down, we looked at one another and said, practically in unison, “Let’s try it.” Imagine our astonishment, then, at the chips’ overwhelming success. Though a bit greasy and heavy on their own, they offered just what we were looking for in a crust: great potato flavor and crunch that wouldn’t quit. After lightening the chips by mixing in some fresh toasted bread crumbs and adding dill for complementary flavor, we found ourselves with an excellent, if unorthodox, topping. We also found that the chips made a rich foil for some of the other flavors we wanted to add.

Because the chips brown under the broiler in just a minute—literally—we broiled the fish until it was almost cooked through before adding the topping. This gave us just the texture we wanted. After adding a flavorful wet element (mustard) to help the crumbs adhere to the fish, we knew we had it: a quick, oven-cooked, well-flavored, texturally interesting—and rather surprising—salmon dinner for eight.

Broiled Salmon with Mustard and Crisp Dilled Crust

SERVES 8 TO 10

Heavy-duty aluminum foil measuring 18 inches wide is essential for creating a sling that aids in transferring the cooked side to a cutting board. Use a large baking sheet so that the salmon will lie flat. If you can’t get the fish to lie flat, even when positioning it diagonally on the baking sheet, trim the tail end. If you prefer to cook a smaller (2-pound) fillet, ask to have it cut from the thick center of the fillet, not the thin tail end, and begin checking doneness a minute earlier. We prefer thick-cut and kettle-cooked potato chips in this recipe; ridged chips will work in a pinch.

3 slices hearty white sandwich bread, crusts removed

4 ounces high-quality potato chips, finely crushed (1 cup)

6 tablespoons minced fresh dill

1 (3½-pound) skin-on side of salmon, pinbones removed

1 teaspoon olive oil

Salt and pepper

3 tablespoons Dijon mustard

Lemon wedges

1. Adjust oven rack to middle position and heat oven to 400 degrees. Pulse bread in food processor to even ¼-inch pieces, about 10 pulses. Spread crumbs evenly on rimmed baking sheet and toast, stirring occasionally, until golden brown and crisp, 4 to 5 minutes. Combine toasted crumbs, crushed potato chips, and dill in bowl.

2. Adjust oven racks 3 inches and 6 inches from broiler element and heat broiler. Cut piece of heavy-duty aluminum foil to be 1 foot longer than side of salmon, then fold lengthwise in thirds. Lay foil diagonally across rimmed baking sheet. Lay salmon, skin side down, on foil, rub with oil, and season with salt and pepper. Broil salmon on upper rack until surface is spotty brown and center is still translucent when checked with tip of paring knife and registers 125 degrees (for medium-rare), 9 to 11 minutes.

3. Remove fish from oven. Working quickly, spread evenly with mustard, then press bread-crumb mixture onto fish. Return salmon to lower rack and broil until crust is deep golden brown, about 1 minute.

4. Using foil sling, transfer salmon to cutting board (or serving platter). Run spatula underneath salmon to loosen it from foil. Using spatula to hold salmon in place on cutting board, gently pull foil out from underneath salmon. Serve with lemon wedges.

variations

Broiled Salmon with Chutney and Crisp Spiced Crust

Use a smooth mango chutney for this recipe. If you can find only chunky mango chutney, puree it in a food processor until smooth before using.

Melt 2 tablespoons unsalted butter in 8-inch skillet over medium heat. Off heat, add 1 minced garlic clove, ½ teaspoon ground cumin, ½ teaspoon paprika, ¼ teaspoon ground cinnamon, ¼ teaspoon cayenne, and ¼ teaspoon salt. Set aside. Substitute 3 tablespoons chopped fresh parsley for dill, toss butter-spice mixture into bread crumbs along with potato chips, and substitute 3 tablespoons smooth mango chutney for Dijon mustard.

Broiled Salmon with Spicy Cilantro-Citrus Paste and Crisp Crust

Process 2 cups cilantro leaves, 3 shallots, 2 stemmed and seeded jalapeño chiles, one 1-inch piece peeled fresh ginger, 3 garlic cloves, 2 tablespoons honey, and 2 teaspoons grated lime zest plus 3 tablespoons juice (2 limes) in food processor until smooth, about 30 seconds, scraping down bowl as necessary. Omit dill and substitute ½ cup cilantro-citrus paste for Dijon mustard.

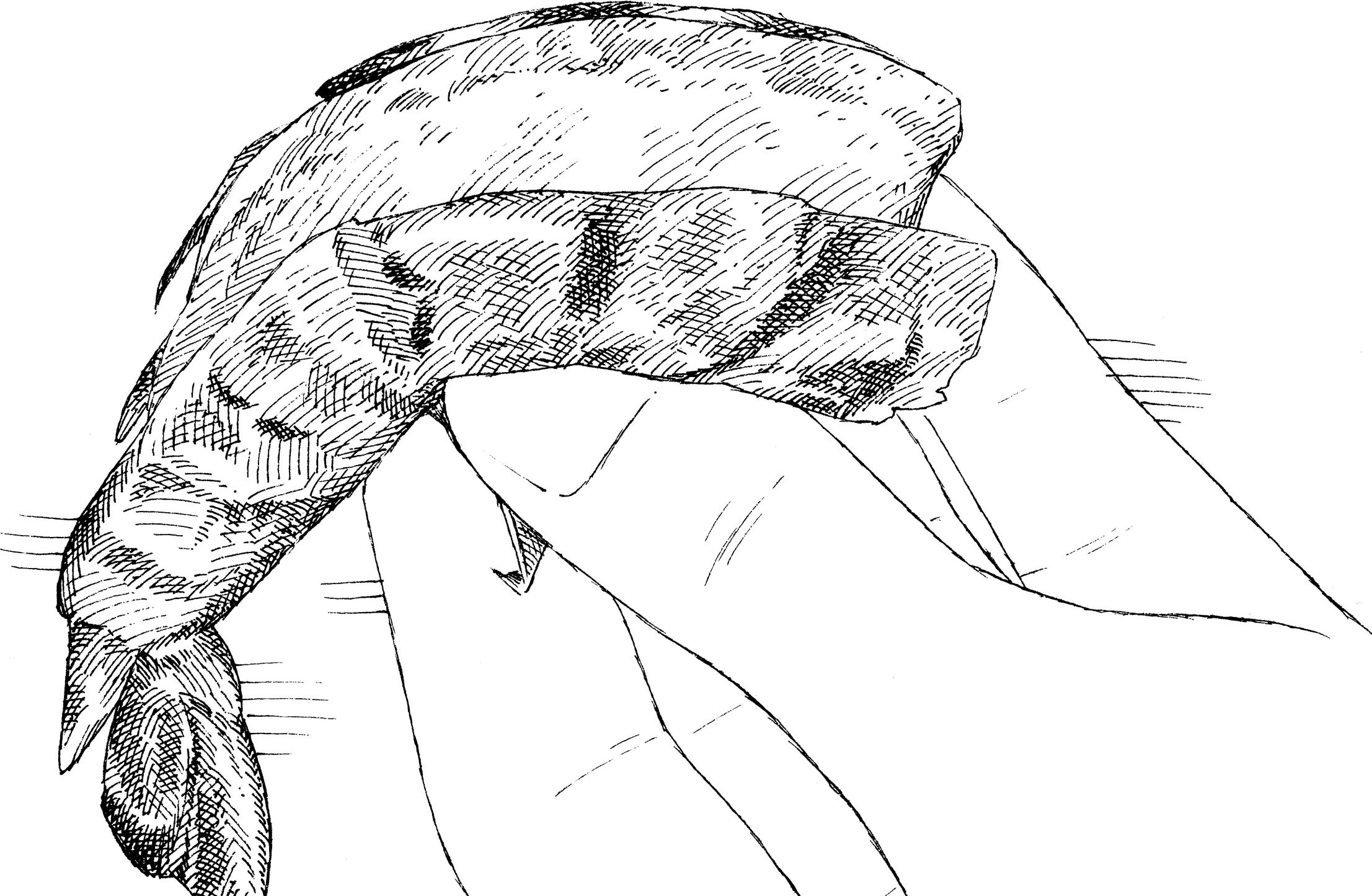

SERVING THE SALMON

To ensure a beautiful presentation, we broil the salmon on a foil sling, which we use to transfer the finished salmon from the baking sheet to the cutting board. Here’s how we get the salmon off the foil neatly and in one piece.

Using foil sling, transfer salmon to cutting board. Run spatula underneath fish to loosen. Use spatula to hold salmon in place and gently pull foil out.

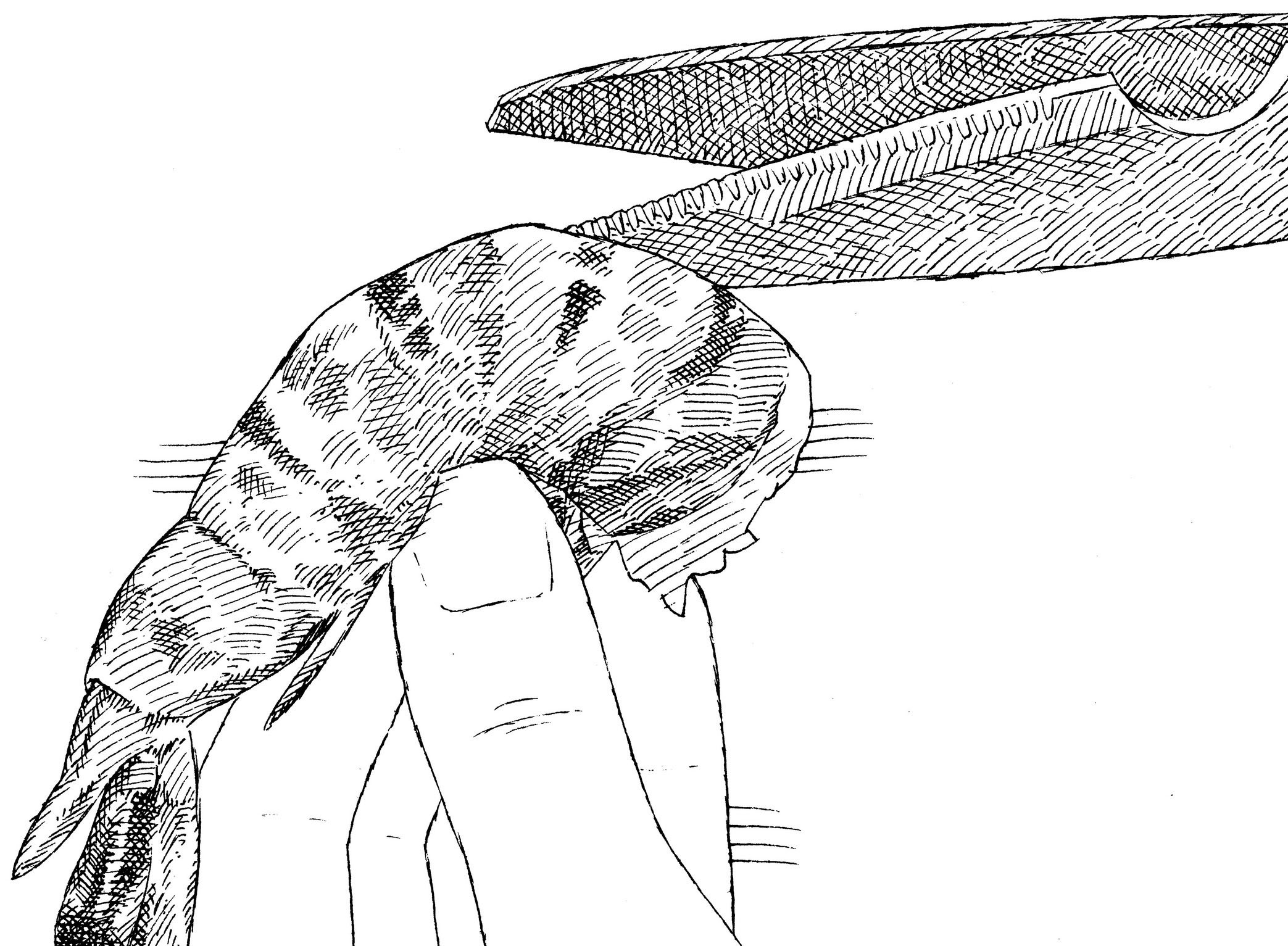

PREPARING THE SALMON

1. Run your fingers over surface to feel for pinbones, then remove them with tweezers or needle-nose pliers.

2. Hold sharp knife at slight downward angle to flesh and cut off whitish, fatty portion of belly.

Pan-searing salmon sounds so straightforward that I’ve never given much thought to the technique. Normally, I’d add a little oil to a nonstick skillet, get it good and hot, sprinkle a few skinless fillets with salt and pepper, slide them into the pan, and cook them on both sides until the fish was cooked through and browned on the exterior but still pink on the inside.

But when I gave this approach a more critical look, I could see that it had two flaws. While the fish had a nice rosy interior at its thickest point, it was a bit overcooked and dry at the thinner end. Secondly, the exteriors of the fillets were more tough than crisp. I wanted to take advantage of the intense heat of the skillet to produce a golden-brown, ultracrisp crust on salmon fillets while keeping their interiors moist.

Brining the fish briefly and cooking the salmon with the skin on guarantees moist, not tough, flesh.

The solution to the dryness problem was relatively easy: salt. Either salting or brining would season the flesh and help keep it moist. This being a quick weeknight dinner, I didn’t want to wait 2 hours for salting to do its job. Brining took about 15 minutes, and as long as I patted the fillets dry with paper towels before cooking, I found that the treatment didn’t significantly inhibit browning.

I decided to focus on getting a really nice sear on only the flesh side since it would be facing up when the fillet was plated. Plus, browning both sides could lead to overcooking. Cooking the fish through with the flesh side down the entire time produced a wonderfully crisp crust, but it also left me with an unworkable dilemma: Either the face-up (skinned) side was nearly sushi-raw, or the rest of the fillet overcooked while I waited for the face-up side to cook through. Covering the pan with a lid toward the end helped cook the fish through more evenly, but this trapped moisture, softening the crust.

There was one piece left to tinker with: the heat level. What if I added the fish to a cold pan and then turned on the heat? This would allow the fish to cook through gently as the pan slowly came up to temperature. I’d then flip the fillets over after the skillet was good and hot so they could form a crust and finish cooking through.

I quickly discovered a problem starting with a not-so-hot skillet: No matter how gently I cooked the first side, it tended to dry out and turn tough on the very exterior. When I was skinning the salmon for my next test, I came up with the solution: Leave the skin on. It could serve to protect that first side as it cooked, and I could simply remove it after flipping the fish.

Sure enough, this worked perfectly. Even better, the skin shed enough fat as it cooked that I was able to cook the fish without needing to add a single drop of oil to the pan.

This salmon was excellent with just a squirt of lemon, but a mango-mint salsa was easy to make, and its bright flavor balanced the salmon’s richness.

Pan-Seared Salmon

SERVES 4

To ensure uniform cooking, buy a 1½- to 2-pound center-cut salmon fillet and cut it into four pieces. Using skin-on salmon is important here, as we rely on the fat underneath the skin as the cooking medium (as opposed to adding extra oil). If using wild salmon, cook it until it registers 120 degrees. If you don’t want to serve the fish with the skin, we recommend peeling it off the fish after cooking rather than before. Serve the salmon with lemon wedges or with our Mango-Mint Salsa (recipe follows), if desired.

Kosher salt and pepper

4 (6- to 8-ounce) skin-on salmon fillets

Lemon wedges

1. Dissolve ½ cup salt in 2 quarts cold water in large container. Submerge salmon in brine and let stand at room temperature for 15 minutes. Remove salmon from brine and pat dry with paper towels.

2. Sprinkle bottom of 12-inch nonstick skillet evenly with ½ teaspoon salt and ½ teaspoon pepper. Place fillets, skin side down, in skillet and sprinkle tops of fillets with ¼ teaspoon salt and ¼ teaspoon pepper. Heat skillet over medium-high heat and cook fillets without moving them until fat begins to render, skin begins to brown, and bottom ¼ inch of fillets turns opaque, 6 to 8 minutes.

3. Using tongs, flip fillets and continue to cook without moving them until centers are still translucent when checked with tip of paring knife and register 125 degrees, 6 to 8 minutes longer. Transfer fillets, skin side down, to serving platter and let rest for 5 minutes before serving with lemon wedges.

accompaniment

MAKES ABOUT 1 CUP

Adjust the salsa’s heat level by reserving and adding the jalapeño seeds, if desired.

1 mango, peeled, pitted, and cut into ¼-inch pieces

1 shallot, minced

3 tablespoons lime juice (2 limes)

2 tablespoons chopped fresh mint

1 jalapeño chile, stemmed, seeded, and minced

1 tablespoon extra-virgin olive oil

1 garlic clove, minced

½ teaspoon salt

Combine all ingredients in bowl.

The process of smoking fish over hardwood has a long tradition, and rich, fatty salmon is well suited to the technique. But smoked salmon’s unique taste and texture don’t come easy: The translucent, mildly smoky slices piled on bagels are produced by ever-so-slowly smoking (but not fully cooking) salt-cured fillets at roughly 60 to 90 degrees, a project that requires specialized equipment and loads of time (at least 24 hours and as long as five days). Then there is hot smoking, a procedure in which cured fillets are fully cooked at higher temperatures (100 to 250 degrees) for one to eight hours. The higher heat results in a drier texture and a more potent smokiness, so the fish is often flaked and mixed into dips and spreads.

Both approaches deliver terrific results—but are impractical (if not impossible) for a home cook to pull off. Sure, you can impart a touch of smokiness by tossing wood chips onto hot charcoal and quickly grilling fish fillets, but I had also heard of a lesser-known, more intriguing option that captures both the intense, smoky flavor of hot-smoked fish and the firm but silky texture of the cold-smoked type. It’s easy because the fish is cooked via indirect heat on a grill—a familiar and uncomplicated technique. And although the resulting fillets have a distinctive taste, they are not overpoweringly salty or smoky, so they’re suitable as an entrée either warm from the grill or at room temperature.

A salt-and-sugar rub before cooking over an indirect grill fire produces silky, smoky fillets.

To try out these smoky, succulent fillets, I scoured cookbooks for recipes. The typical first step in smoking fish is to cure the flesh with salt; some authors recommended brining, others directly salting the fillet. To keep the preparation time in check, I steered away from recommendations for curing the fish for longer than an hour or two.

The other criteria, smoking temperature and length of exposure–both crucial to the final result—were all over the map. One recipe called for smoking the fish at 350 degrees for a modest 20 minutes; another let it go twice as long at only 275 degrees.

IN TREATMENT

With so many factors at play, I decided to try a simple brine first, soaking a center-cut skin-on fillet (retaining the skin would make it easier to remove the fillet from the grill) in the test kitchen’s usual 9 percent solution of salt and water for 2 hours. For the time being, I used a moderate amount of coals, dumping 4 quarts of lit charcoal on one side of the grill, along with a few soaked wood chips to provide the smoke. I placed the fish on the cooking grate opposite the coals, popped the cover on the grill, and smoked the fish until it was still a little translucent at the center, about 25 minutes.

The result was illuminating if not exactly spectacular. The long stay in the brine had the unfortunate effect of making the salmon terribly bloated; plus, it seemed to highlight the fish’s natural oiliness in an unpleasant way—a far cry from the supple but firm texture I was after.

For my next try, I covered the salmon in a generous blanket of kosher salt—its coarse texture makes it cling to food better than table salt—and refrigerated it uncovered on a wire rack on a baking sheet. After an hour, a considerable amount of liquid had been drawn to the surface of the flesh. I knew that if I waited any longer, the fluid would start to migrate back into the salmon through the process of osmosis, leading to a bloated texture, so I promptly removed it from the refrigerator, blotted the moisture with a paper towel, and took it out to the grill for smoking. This sample was considerably better than the brined fish: incredibly moist yet still firm—and not at all soggy. It wasn’t perfect, though, since most tasters found it too salty to be enjoyed as a main dish. I tried dialing down the amount of salt as well as salting for a shorter amount of time, but alas, the fish didn’t achieve the proper texture.

Back at my desk, I looked for a solution in the recipes that I’d collected and came across a few that called for adding sugar to the cure. I knew that, like salt, sugar is hygroscopic, meaning it attracts water. Could sugar pull moisture from the salmon as effectively as salt? Not quite: Because individual molecules of sucrose are much larger than sodium and chloride ions, sugar is, pound for pound, about 12 times less effective than salt at attracting moisture. Still, it was a workable option; I just had to do some tinkering. Eventually, I determined that a ratio of 2 parts sugar to 1 part salt produced well-balanced taste and texture in the finished salmon. Using these proportions, the fish firmed up nicely; plus, it was far less salty and the sugar counterbalanced its richness.

SMOLDERING ISSUES

With a reliable curing method in hand, I could finally fine-tune my smoking technique. My current setup was far from ideal: By the time the fish was sufficiently smoky, it was dry and flaky. Conversely, when it was cooked perfectly—still silky and slightly pink in the interior, or about 125 degrees—the smoke flavor was faint. Adding more wood chips only gave the fillet a sooty flavor. Instead, I tried to cool down the temperature of the grill by reducing the amount of charcoal from 4 quarts to 3 quarts. This helped somewhat, since the fish cooked more slowly (a full 30 to 40 minutes) and had more time to absorb smoke.

But the smoke flavor still wasn’t as bold as I wanted. Rather than manipulating the cooking time any further, I turned to the salmon itself, cutting the large fillet into individual serving-size portions. This seemingly minor tweak resulted in big payoffs: First, it ensured more thorough smoke exposure (in the same amount of time) by creating more surface area. Second, the delicate pieces were far easier to get off the grill in one piece than a single bulky fillet. (To that end, I also started placing the fillets on a piece of foil coated with vegetable oil spray.) Finally, I found that I could now use an even cooler fire (produced with a mere 2 quarts of charcoal): The smaller fillets still reached their ideal serving temperature in the same amount of time that the single, larger fillet had taken. Plus, the gentler fire rendered the fillets incomparably tender.

With a smoky, rich taste and a silky, supple texture, my quick smoked salmon recipe was, to put it plainly, smoking hot.

SERVES 6

Use center-cut salmon fillets of similar thickness so that they cook at the same rate. If using wild salmon, cook until the thickest part of the fillet registers 120 degrees. The best way to ensure uniformity is to buy a 2½- to 3-pound whole center-cut fillet and cut it into six pieces. If you’d like to use wood chunks instead of wood chips when using a charcoal grill, substitute two wood chunks, soaked in water for 1 hour, for the wood chip packet. Avoid mesquite wood chunks for this recipe. Serve the salmon with lemon wedges or our “Smoked Salmon Platter” Sauce (recipe follows).

2 tablespoons sugar

1 tablespoon kosher salt

6 (6- to 8-ounce) center-cut skin-on salmon fillets

2 cups wood chips

1. Combine sugar and salt in bowl. Set wire rack in rimmed baking sheet, set salmon on rack, and sprinkle flesh side evenly with sugar mixture. Refrigerate, uncovered, for 1 hour. With paper towels, brush any excess salt and sugar from salmon and blot dry. Return salmon on wire rack to refrigerator, uncovered, while preparing grill.

2. Just before grilling, soak 1 cup wood chips in water for 15 minutes, then drain. Using large piece of heavy-duty aluminum foil, wrap soaked and unsoaked chips together in 8 by 4½-inch foil packet. (Make sure chips do not poke holes in sides or bottom of packet.) Cut 2 evenly spaced 2-inch slits in top of packet.

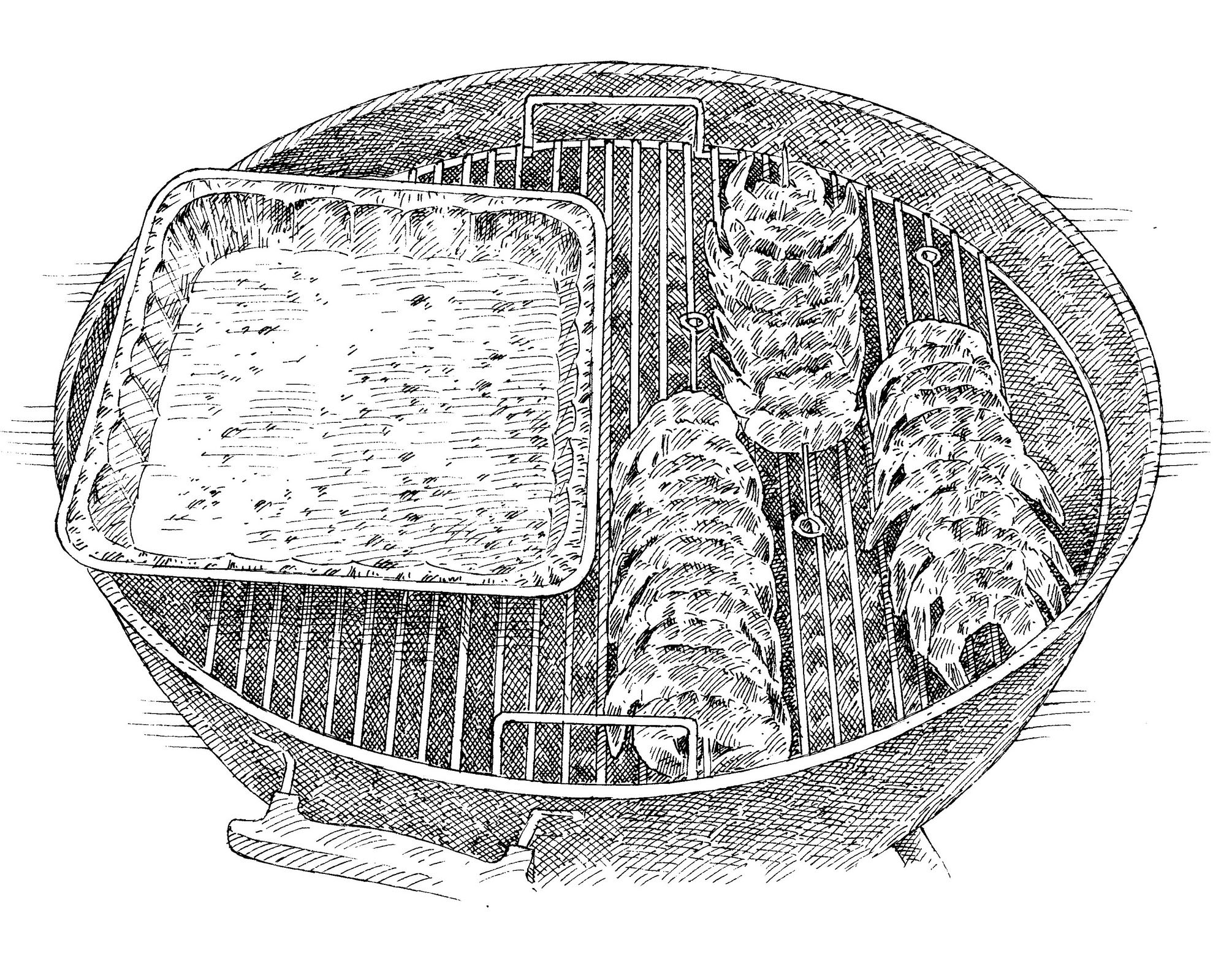

3A. For a charcoal grill: Open bottom vent halfway. Light large chimney starter one-third filled with charcoal briquettes (2 quarts). When top coals are partially covered with ash, pour into steeply banked pile against side of grill. Place wood chip packet on coals. Set cooking grate in place, cover, and open lid vent halfway. Heat grill until hot and wood chips are smoking, about 5 minutes.

3B. For a gas grill: Remove cooking grate and place wood chip packet directly on primary burner. Set grate in place, turn primary burner to high (leave other burners off), cover, and heat grill until hot and wood chips are smoking, 15 to 25 minutes. Turn primary burner to medium. (Adjust primary burner as needed to maintain grill temperature of 275 to 300 degrees.)

4. Fold piece of heavy-duty foil into 18 by 6-inch rectangle. Place foil rectangle on cooler side of grill and place salmon fillets on foil, spaced at least ½ inch apart. Cover (position lid vent over salmon if using charcoal) and cook until center of thickest part of fillet is still translucent when checked with tip of paring knife and registers 125 degrees (for medium-rare), 30 to 40 minutes. Transfer to platter and serve warm or at room temperature.

accompaniment

“Smoked Salmon Platter” Sauce

MAKES 1½ CUPS

1 large egg yolk, plus 1 hard-cooked large egg, chopped fine

2 teaspoons Dijon mustard

2 teaspoons sherry vinegar

½ cup vegetable oil

2 tablespoons capers, rinsed, plus 1 teaspoon brine

2 tablespoons minced shallot

2 tablespoons minced fresh dill

Whisk egg yolk, mustard, and vinegar together in medium bowl. Whisking constantly, slowly drizzle in oil until emulsified, about 1 minute. Gently fold in capers and brine, shallot, dill, and hard-cooked egg.

NOW WE’RE SMOKIN’

Typically, cold- or hot-smoking salmon requires special equipment and a serious time investment. Our recipe captures the best of both methods and cooks in only 30 to 40 minutes on a regular grill.

COLD-SMOKED

Slick and silky; mild smoke

HOT-SMOKED

Dry and firm; potent smoke

HYBRID GRILL-SMOKED

Ultramoist; rich, balanced smoke

Nothing is more basic than shrimp cocktail, and given its simplicity, few dishes are more difficult to improve. Yet I set out to do just that this past winter and believe I succeeded.

Shrimp cocktail, as everyone must know, is “boiled” shrimp served cold with “cocktail” sauce, typically a blend of bottled ketchup or chili sauce spiked with horseradish. It’s easy enough to change the basic pattern in order to produce a more contemporary cold shrimp dish; you could, for example, grill shrimp and serve them with a fresh tomato salsa (and many people have done just that). But there is something refreshing and utterly classic about traditional shrimp cocktail, and sometimes it fits the occasion better than anything else.

I saw three ways to challenge the traditional method of preparing shrimp cocktail in order to produce the best-tasting but recognizable version of this dish. One, work on the flavor of the shrimp; two, work on the cooking method for the shrimp; three, produce a great cocktail sauce.

FLAVORING THE SHRIMP

The shrimp in shrimp cocktail can be ice-cold strings of protein, chewy or mushy, or they can be tender, flavorful morsels that barely need sauce. To achieve the latter, you need to start with the best shrimp you can find and give them as much flavor as they can handle without overwhelming them.

If you start with good shrimp and follow a typical shrimp cocktail recipe—that is, simmer the shrimp in salted water until pink—the shrimp will have decent but rarely intense flavor. The easiest way to intensify the flavor of shrimp is to cook them in their shells. But, as I found out, this has an obvious drawback: It’s far easier to peel shrimp when they are raw than once they are cooked.

It’s better, then, to make shrimp stock, a simple enough process that takes only 5 minutes using just the shrimp shells, and a process that can be vastly improved if you make it gradually. To do so, every time you use shrimp for any purpose, place the peels in a pot with water to cover, then simmer them for 5 minutes. Cool, strain, and freeze the resultant stock. Use this stock as the cooking liquid for your next batch of shrimp peels. Naturally, this stock will become more and more intense each time you add to it. Even after one batch of peels, however, it’s infinitely better than plain water for cooking shrimp.

For the best flavor and texture, we poach shrimp in a simple shrimp stock off the heat.

Next, I thought, it would be best to see what other flavors would complement the shrimp without overpowering it. My first attempt was to use beer and a spicy commercial seasoning, but this was a near disaster; the shrimp for cocktail should not taste like a New Orleans crab boil. Next I tried a court bouillon, the traditional herb-scented stock for poaching fish, but quickly discovered that the game wasn’t worth the candle; I wanted a few quick additions to my shrimp stock that would add complexity without making a simple process complicated.

After trying about 20 different combinations, involving wine, vinegar, lemon juice, and a near-ludicrous number of herbs and spices, I settled on the mixture given in the recipe here. It contains about 25 percent white wine, a dash of lemon juice, and a more-or-less traditional herb combination. Variations are certainly possible, but I would caution you against adding more wine or lemon juice; both were good up to a point, but after that their pungency became overwhelming.

COOKING THE SHRIMP

Although I was pleased at this point with the quality of the shrimp’s flavor, I still thought it could be more intense. I quickly learned, however, that the answer to this problem was not to keep pouring flavorings into the cooking liquid; that was self-defeating because I eventually lost the flavor of the shrimp. I decided to try to keep the shrimp in contact with the flavorings for a longer period of time.

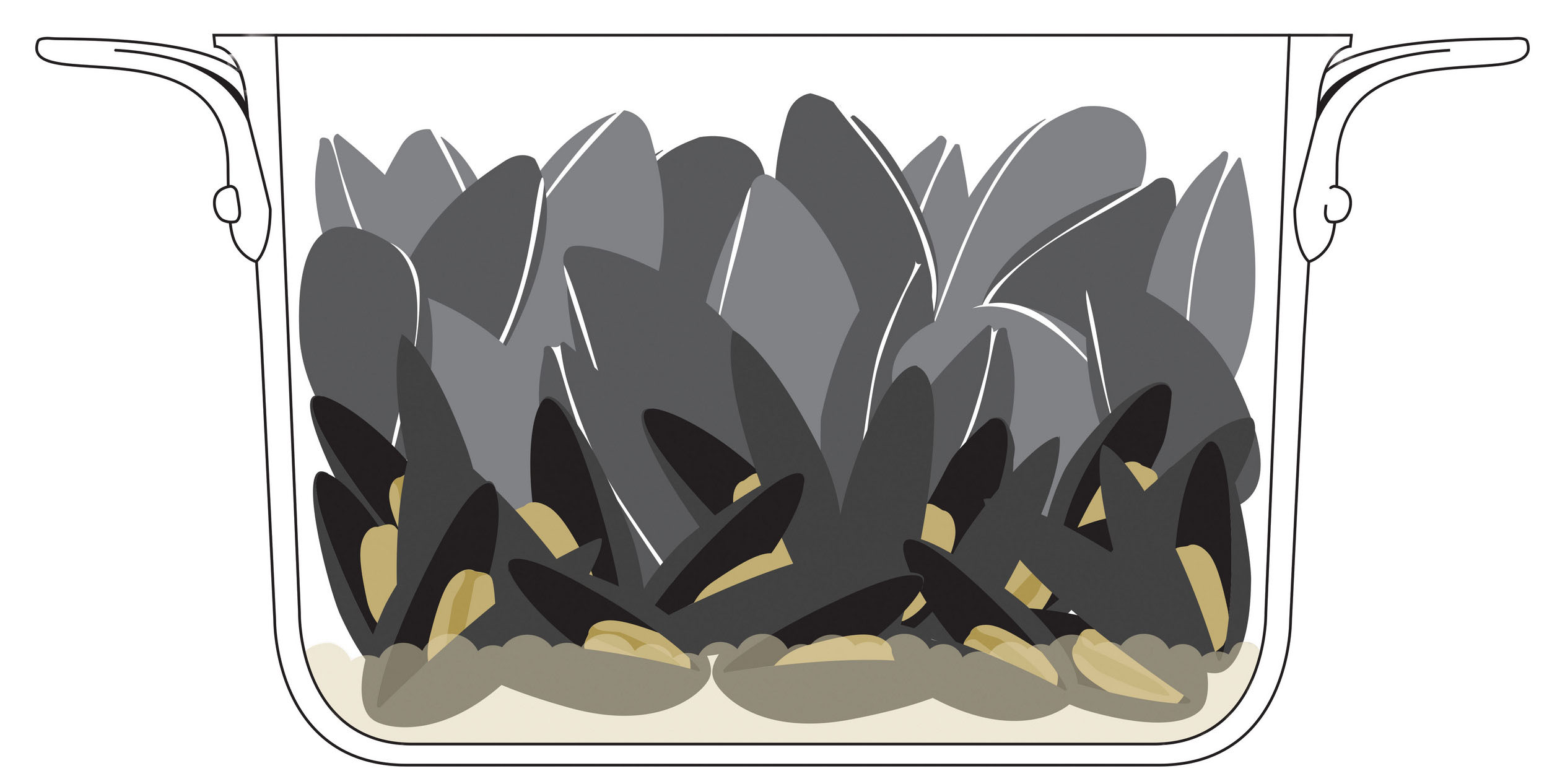

I tried several methods to achieve this, including starting the shrimp in cold water with the seasonings and using a longer cooking time at a lower temperature. But shrimp cooks so quickly—this is part of its appeal, of course—that these methods only served to toughen the meat. What worked best, I found, was to bring the cooking liquid to a boil, turn it off, and add the shrimp. Depending on their size, I could leave them in contact with the liquid for up to 10 minutes (even a little longer for jumbo shrimp), during which time they would cook through without toughening, while taking on near perfect flavor.

THE COCKTAIL SAUCE

Here I felt I was treading a fine line. I wanted to make a better sauce, but I still wanted it to be recognizable as cocktail sauce. Starting with fresh or canned tomatoes, I discovered, just didn’t work: The result was often terrific (some might say preferable), but it was not cocktail sauce. It was as if I had decided to make a better version of liver and onions by substituting foie gras for veal liver—it might be “better,” but it would no longer be liver and onions.

I went so far as to make American-style ketchup from scratch, an interesting project but not especially profitable, in that the effect was to duplicate something sold in near-perfect form in the supermarket. Again, there are more interesting tomato-based sauces than ketchup, but they’re not ketchup.

So I decided the best thing I could do was to find the bottled ketchup or chili sauce I liked best and season it myself. First I had to determine which made the better base, ketchup or chili sauce. The answer to this question was surprising but straightforward: ketchup. Bottled chili sauce is little more than vinegary ketchup with a host of seasonings added. The less expensive chili sauces have the acrid, bitter taste of garlic powder, monosodium glutamate, or other dried seasonings. The more expensive ones have more honest flavors but still did not compare to the cocktail sauce I whipped up in 3 minutes using basic store-bought ketchup. In addition, chili sauce can be four to eight times as expensive as ketchup.

My preference in cocktail sauce has always been to emphasize the horseradish. But ketchup and horseradish, I knew, were not enough. Cocktail sauce benefits from a variety of heat sources, none of which overpower the other, and the sum of which still allows the flavor of the shrimp to come through. I liked the addition of chili powder. I also liked a bit of bite from cayenne, but only a pinch. Black pepper plays a favorable role as well (as does salt, even though ketchup is already salty). Finally, after trying high-quality wine vinegar, balsamic vinegar, rice vinegar, sherry vinegar, and distilled vinegar, I went back to lemon, which is the gentlest and most fragrant acidic seasoning. In sum, the keys to good cocktail sauce include: ordinary ketchup, fresh lemon juice, horseradish (fresh is best—even month-old bottled horseradish is pathetic compared to a just-opened bottle), and fresh chili powder. Proportions can be varied to taste.

Herb-Poached Shrimp with Cocktail Sauce

SERVES 4

When using larger or smaller shrimp, increase or decrease cooking times for shrimp by 1 to 2 minutes, respectively.

Shrimp

1 pound jumbo shrimp (16 to 20 per pound), peeled and deveined, shells reserved

1 teaspoon salt

1 cup dry white wine

5 sprigs fresh parsley

1 sprig fresh tarragon

1 teaspoon lemon juice

5 coriander seeds

4 whole peppercorns

½ bay leaf

Cocktail Sauce

1 cup ketchup

1 tablespoon lemon juice

2½ teaspoons prepared horseradish

1 teaspoon ancho chili powder (or other mild chili powder)

¼ teaspoon salt

¼ teaspoon pepper

Pinch cayenne pepper

1. For the shrimp: Bring reserved shells, 3 cups water, and salt to boil in medium saucepan over medium-high heat; reduce heat to low, cover, and simmer until fragrant, about 5 minutes. Strain stock through sieve, pressing on shells to extract all liquid.

2. Bring stock, wine, parsley, tarragon, lemon juice, coriander seeds, peppercorns, and bay leaf to boil in large saucepan over high heat; boil 2 minutes. Turn off heat and stir in shrimp; cover and let stand until firm and pink, 8 to 10 minutes. Drain shrimp, reserving stock for another use. Plunge shrimp into ice water to stop cooking, then drain again. Transfer to bowl, cover with plastic wrap, and refrigerate until chilled, about 1 hour.

3. For the cocktail sauce: Stir all ingredients together in small bowl. Season with additional salt and pepper to taste. Serve with shrimp.

SHRIMP BASICS

BUYING SHRIMP Virtually all of the shrimp sold in supermarkets today have been previously frozen, either in large blocks of ice or by a method called “individually quick- frozen,” or IQF for short. Supermarkets simply defrost the shrimp before displaying them on ice at the fish counter. We highly recommend purchasing bags of still-frozen shrimp and defrosting them as needed at home, since there is no telling how long “fresh” shrimp may have been kept on ice at the market. IQF shrimp have a better flavor and texture than shrimp frozen in blocks, and they are convenient because it’s easy to defrost just the amount you need. Also, shrimp should be the only ingredient listed on the bag; some packagers add preservatives, but we find treated shrimp to have an unpleasant, rubbery texture.

SORTING OUT SHRIMP SIZES Shrimp are sold both by size (small, medium, etc.) and by the number needed to make 1 pound, usually given in a range. Choosing shrimp by the numerical rating is more accurate, because the size label varies from store to store. Here’s how the two sizing systems generally compare:

|

SMALL |

51 to 60 per pound |

|

MEDIUM |

41 to 50 per pound |

|

MEDIUM-LARGE |

31 to 40 per pound |

|

LARGE |

26 to 30 per pound |

|

EXTRA-LARGE |

21 to 25 per pound |

|

JUMBO |

16 to 20 per pound |

DEFROSTING SHRIMP You can thaw frozen shrimp overnight in the refrigerator in a covered bowl. For a quicker thaw, place them in a colander under cold running water; they will be ready in a few minutes. Thoroughly dry the shrimp before cooking.

Shrimp scampi is rarely awful—it’s unusual for things to go terribly wrong when garlic, wine, and butter are involved—but restaurant versions always make me wish I’d ordered differently. I have never been presented with the ultimate scampi, the one that I can almost taste when I peruse the menu: perfectly cooked, briny beauties in a garlicky, buttery (but not greasy) white wine sauce.

When I last made my way through a mediocre rendition, I decided it was time to realize this ideal scampi vision at home. Since shrimp are susceptible to overcooking, which can make them dry and tough, I gave my shrimp (1½ pounds, enough to serve four) a short dunk in a saltwater solution to season them and help preserve moisture. I then heated extra-virgin olive oil in a skillet, sautéed a few cloves of minced garlic and a dash of red pepper flakes, and added the shrimp. Once the shrimp turned opaque, I splashed in some dry white wine and followed it with a chunk of butter, a big squeeze of lemon juice, and a sprinkle of parsley.

My guests and I didn’t go hungry that night, but the scampi was far from perfect. One problem was that the sauce separated into a butter-and-oil slick floating on top of the wine—not ideal in the looks department or for dunking bread into. (While some serve shrimp scampi over a pile of spaghetti, I think it’s best with a crusty loaf.) Then there were the shrimp: Some were a little overdone, while others were still translucent. Finally, the overall dish was shy on both seafood and garlic flavors. For results that I’d be truly satisfied with, some adjustments were in order.

SHRIMP TALES

Back in the test kitchen, I thought about ways to improve the shrimp. Flavorful crustaceans are often thought of as sweet, so would adding sugar to the brine be beneficial? Sure enough, my colleagues agreed that when used judiciously (2 tablespoons of sugar along with 3 tablespoons of salt in 1 quart of water), the sugar subtly boosted the natural flavor of the shrimp. I also found that using untreated shrimp, with no added salt or preservatives, produced the best results.

Another detail to consider was the cooking method. The inconsistent doneness of my first batch had come from crowding the skillet, so I needed to sauté the shrimp in batches. Or did I? What if, instead of sautéing the shrimp and then adding the wine, I gently poached the shrimp in the wine? As it turned out, this approach cooked all of the shrimp just right and in unison, as long as the skillet was covered with a lid to trap steam.

Now that I had flavorful, properly cooked shrimp, it was time to tackle the sauce. I had three items on my to-do list. First: Seriously bump up the flavor. (I’d found that the 5 minutes or so that it took to cook the shrimp wasn’t long enough to impart much of a seafood taste to the dish.) Second: Add extra garlic for a more robust punch. Third: Fix the separated consistency.

WASTE NOT, WANT NOT

A few ladles of stock made from trimmings, bones, or other ingredient scraps can be a great way to infuse flavor into a sauce. Here I could make a stock from the shrimp shells, so I started buying shell-on shrimp instead of the prepeeled type (to save time, I started using the jumbo size so I’d have fewer to peel). To coax out every bit of savoriness, I first browned the shells in a little olive oil and then simmered them in the wine for 30 minutes with a few sprigs of thyme for a little more complexity. But the stock didn’t taste all that shrimpy. My incorrect assumption was that simmering the shells for a longer period of time would extract more flavor from them. A timing test conducted by a fellow test cook debunked that myth, finding that you get more flavor out of shrimp shells if you simmer them for only 5 minutes. This was an easy change I was happy to make.

Next, I doubled the amount of garlic. It worked to boost the garlic flavor but not without a cost: All of those minced pieces gave the sauce a gritty quality. To prevent this, I switched from mincing the cloves to slicing them into thin rounds. But since sliced garlic is milder in flavor than minced (garlic’s bite is created in the act of damaging its cells; the finer it’s cut, the stronger its flavor will be) the switch required that I double the number of cloves, to eight.

Poaching—rather than sautéing—the shrimp in wine enhanced with browned shrimp shells takes this dish from good to great.

All that remained was to bind the fats and wine together into a cohesive sauce. In other words, I needed a stabilizer. I considered my choices: Flour, gelatin, and even pectin would work, but cornstarch seemed like the best option since it would require virtually no cooking to get the job done. I could hydrate the cornstarch in some of the wine, but I decided that it would be more convenient to use the lemon juice I was adding to the sauce for brightness. A mere teaspoon of cornstarch worked like a charm. I stirred the mixture into the sauce before adding the butter, which easily whisked into the rest of the sauce and stayed there, giving it a creamy, silky texture. In fact, it was so rich and creamy that I was able to scale back the amount of butter to 4 tablespoons without anyone finding it too lean. And there it was: the scampi I’d been looking for all along.

Shrimp Scampi

SERVES 4

Extra-large shrimp (21 to 25 per pound) can be substituted for jumbo shrimp. If you use them, reduce the cooking time in step 3 by 1 to 2 minutes. We prefer untreated shrimp, but if your shrimp are treated with sodium or preservatives like sodium tripolyphosphate, skip the brining in step 1 and add ¼ teaspoon of salt to the sauce in step 4. Serve with crusty bread.

3 tablespoons salt

2 tablespoons sugar

1½ pounds jumbo shrimp (16 to 20 per pound), peeled, deveined, and tails removed, shells reserved

2 tablespoons extra-virgin olive oil

1 cup dry white wine

4 sprigs fresh thyme

3 tablespoons lemon juice, plus lemon wedges for serving

1 teaspoon cornstarch

8 garlic cloves, sliced thin

½ teaspoon red pepper flakes

¼ teaspoon pepper

4 tablespoons unsalted butter, cut into ½-inch pieces

1 tablespoon chopped fresh parsley

1. Dissolve salt and sugar in 1 quart cold water in large container. Submerge shrimp in brine, cover, and refrigerate for 15 minutes. Remove shrimp from brine and pat dry with paper towels.

2. Heat 1 tablespoon oil in 12-inch skillet over high heat until shimmering. Add shrimp shells and cook, stirring frequently, until they begin to turn spotty brown and skillet starts to brown, 2 to 4 minutes. Remove skillet from heat and carefully add wine and thyme sprigs. When bubbling subsides, return skillet to medium heat and simmer gently, stirring occasionally, for 5 minutes. Strain mixture through colander set over large bowl. Discard shells and reserve liquid (you should have about ⅔ cup). Wipe out skillet with paper towels.

3. Combine lemon juice and cornstarch in small bowl. Heat remaining 1 tablespoon oil, garlic, pepper flakes, and pepper in now-empty skillet over medium-low heat, stirring occasionally, until garlic is fragrant and just beginning to brown at edges, 3 to 5 minutes. Add reserved wine mixture, increase heat to high, and bring to simmer. Reduce heat to medium, add shrimp, cover, and cook, stirring occasionally, until shrimp are just opaque, 5 to 7 minutes. Remove skillet from heat and, using slotted spoon, transfer shrimp to bowl.

4. Return skillet to medium heat, add lemon juice–cornstarch mixture, and cook until slightly thickened, 1 minute. Remove from heat and whisk in butter and parsley until combined. Return shrimp and any accumulated juices to skillet and toss to combine. Serve, passing lemon wedges separately.

WHEN LESS TIME MEANS MORE FLAVOR

It’s easy to view shrimp shells simply as an impediment to the sweet, briny flesh within, but the shells actually contain lots of flavorful compounds that can be extracted into a stock. We’ve always assumed that, as with beef bones, the longer shrimp stock simmered, the more intense its flavor would be. But was that really true? To find out, we designed a test to determine the optimal simmering time.

EXPERIMENT We simmered batches of shrimp shells in water, covered, for 5, 10, 15, and 30 minutes and then strained out the shells. We asked tasters to evaluate the flavor of each sample.

RESULTS Tasters almost unanimously chose the 5- and 10-minute simmered samples as “more potent,” “shrimpier,” and “more aromatic” than the 15- and 30-minute simmered samples.

EXPLANATION While some of the savory compounds found in shrimp shells are stable (i.e., they stay in the stock, rather than release into the atmosphere), the compounds that we associate with shrimp flavor are highly volatile. The longer a stock is simmered, the more of these molecules will release into the air, and the blander the stock will be.

TAKEAWAY For the most flavorful shrimp stock, simmer shells for just 5 minutes.

ALL ABOUT GARLIC

Garlic is an essential flavor component of our Shrimp Scampi. Here’s everything you need to know about it.

BUYING GARLIC Pick heads without spots, mold, or sprouting. Squeeze them to make sure they are not rubbery or missing cloves. The garlic shouldn’t have much of a scent. Of the various garlic varieties, your best bet is soft-neck garlic, since it stores well and is heat-tolerant. This variety features a circle of large cloves surrounding a small cluster at the center. Hard-neck garlic has a stiff center staff surrounded by large, uniform cloves and boasts a more intense flavor. But since it’s easily damaged and doesn’t store as well as soft-neck garlic, wait to buy it at the farmers’ market.

STORING GARLIC Whole heads of garlic should last at least a few weeks if stored in a cool, dark place with plenty of air circulation to prevent spoiling and sprouting.

PREPARING GARLIC Keep in mind that garlic’s pungency emerges only after its cell walls are ruptured, triggering the creation of a compound called allicin. The more a clove is broken down, the more allicin that is produced. In our Shrimp Scampi, we love a big hit of garlic flavor, but mincing the cloves gave the sauce a gritty texture. Switching to sliced garlic eliminated grittiness but also gave the sauce less garlic flavor, since the cloves were less broken down. Upping the number of cloves to eight gave us the best of both worlds. Also, it’s best not to cut garlic in advance; the longer cut garlic sits, the harsher its flavor.

When I set out to find the best way to make roasted shrimp, I thought I’d hit the jackpot. Quick-cooking shrimp make an easy weeknight dinner, and the idea of roasting them until they develop deep, flavorful browning seemed so natural that I figured there were plenty of good recipes out there to learn from.

Imagine my surprise, then, when the handful I tried produced pale, insipid shrimp that looked as though they’d been baked, not roasted. Some of the missteps seemed obvious, such as crowding lots of small shrimp (tossed with oil and aromatics) on a sheet pan or in a baking dish, where their exuded moisture caused them to steam and prevented browning. Some of the oven temperatures were also strangely low—around 300 degrees. I was sure I could do better, while keeping the technique simple enough for an easy weeknight meal.

THE HEAT IS ON

My challenge was clear from the start: The goals of roasting—a juicy interior and a thoroughly browned exterior—were impeded by the fact that lean shrimp cook through very quickly. Knowing that, I made two immediate decisions: First, I would crank the oven temperature very high to get good browning on the exterior of the shrimp—500 degrees seemed like a fine place to start. Second, I would use the biggest shrimp I could get. That meant skipping right past even the extra-large size and reaching for the jumbo (16 to 20 per pound) shrimp, which would be the least likely to dry out in the heat. Using larger shrimp would also mean that there would be fewer pieces crowding the pan, and their smaller total amount of surface area would mean that less steam would be created—therefore making browning possible. As a test run, I oiled and seasoned 2 pounds of peeled shrimp with nothing more than a little salt and pepper (I’d explore flavorings once I’d nailed down a cooking method) and slid them into the oven on a sheet pan.

I thought the 500-degree blast would get the shrimp good and brown in a hurry, so I hovered around the oven and checked on their color every couple of minutes. Trouble was, the color never came—and while I waited and waited for the browning to kick in, the shrimp turned from tender and slightly translucent to fully opaque. I knew before I plunged a fork into them that they were overcooked. Clearly, high heat alone wasn’t going to cut it, so I started experimenting. “Searing” them by preheating the baking sheet in the 500-degree oven helped, but only a little, since the pan’s temperature plummeted as soon as the shrimp hit. Blasting the next batch under the broiler finally delivered some decent browning to the topsides of the shrimp, but their undersides were still damp and utterly pale.

Butterflying shell-on shrimp allows the heady flavors of garlic and spices to thoroughly coat the flesh.

Part of the problem was air circulation. When we roast beef or pork, we often elevate them on a rack so that hot air can surround them, drying out and browning even the underside of the meat. With that in mind, I tried broiling my next batch of shrimp on a wire rack set in the baking sheet—and finally started to see some real progress.