PASTA AND NOODLES

Reinventing Macaroni and Cheese

Spaghetti and (Great) Meatballs

One challenge I’ve always wanted to set for myself is figuring out how to make pasta with nothing more than the dough, a rolling pin, and some elbow grease. While mechanical pasta rollers aren’t all that expensive, many home cooks don’t own them. But as anyone who has ever attempted to roll out a block of hard pasta dough by hand knows, it’s no easy task. The dough has a tendency to spring back—and if it isn’t rolled out gossamer thin, the pasta will never achieve the right al dente texture when cooked. So how do Italian cooks manage to pull off this feat? One answer: years of perseverance.

In her Essentials of Classic Italian Cooking (1992), Marcella Hazan devotes no fewer than six pages to the classic hand-rolling technique perfected in the Emilia-Romagna region of Italy. Employing extra-thin, super-long rolling pins measuring 1½ inches in diameter and 32 inches in length, Italians in this part of the country have developed a series of stretching movements that can transform a lump of firm dough into a thin, delicate sheet. Besides the obvious drawback of needing a generous work surface to accommodate the pin, Hazan is the first to admit that this traditional technique must be exhaustively practiced “until the motions are performed through intuition rather than deliberation.”

While I’m typically game for a hard-won lesson in authenticity, even I have limits. I wanted a dough that any cook could roll out with ease on the first try and that would cook up to that incomparably tender, silky yet slightly firm texture that makes fresh pasta so worth making.

ZERO LUCK

In addition to centuries of experience, Italians have another hand-rolling advantage—the best kind of flour for the job: doppio zero, or 00. The name denotes the fine talcum-like grind that gives pasta and baked goods made with the flour an almost creamy mouthfeel. To see what I was missing, I mail-ordered some and mixed up a batch of dough following a typical approach: I put the usual ratio of 2 cups of flour to three whole eggs in a food processor and processed until they formed a cohesive ball. I then turned the dough out on the counter, kneaded it for several minutes, and set it aside to relax for about 20 minutes. Sure enough, the 00 (which has a protein content of 9 percent) produced a malleable dough that was far easier to work with than dough made from all-purpose flour.

Adding extra egg yolks and a little bit of olive oil to our pasta dough makes it silky, supple, and easy to roll out by hand.

To achieve similarly soft dough, my first inclination was to dilute the protein content of all-purpose flour (which boasts 10 to 12 percent protein) by cutting it with cake flour (which has 6 to 8 percent protein). I substituted increasing amounts of cake flour for all-purpose and noted that swapping even a quarter of the all-purpose flour for cake flour had a dramatic impact on both the raw dough and the cooked noodles. With 25 percent cake flour in the mix, my dough was much softer, less elastic, and easier to roll out. Unfortunately, what I had gained in convenience I lost in the texture of the cooked strands, which released a lot of starch into the cooking water and emerged with a pitted, pebbly surface. Our science editor explained why: For noodles to remain intact and leach only a little starch into the cooking water, the starch granules in the flour need to be fully surrounded by a strong network of proteins. But the bleach in cake flour not only weakens the proteins but also makes the starch more absorbent and prone to bursting—a good thing when you want a tender cake but not when you’re making pasta. Clearly, I needed a different strategy for producing softer, more malleable dough, so I turned my attention to the amount of liquid in the recipe.

IS WETTER BETTER?

Traditional pasta dough is about 30 percent water (compared with around 55 percent hydration for a basic sandwich loaf), all of which comes from the eggs. I figured that simply upping the hydration level would create a softer dough that would be easier to roll out, so I experimented with adding plain water to a batch of dough and an extra egg white (the white accounts for 80 percent of an egg’s moisture) to another. Just as I’d hoped, these more hydrated doughs were more extensible—at least initially. But they had their downsides: First, the wetter surface of the dough caused considerable sticking, which required the heavy use of bench flour during rolling and led to cooked pasta with a starchy, gummy surface. Second, by adding more water, I’d allowed for too much gluten development, creating dough that, although easier to roll out at first, developed a greater tendency to snap back to its original shape once stretched out; this also meant pasta that cooked up tough and chewy. Still, I felt I was on to something by increasing the liquid in my recipe. Olive oil is a common addition to many fresh pasta recipes. What if I introduced it instead of water?

I mixed up a few more batches of dough, adding increasing amounts of olive oil. As the oil amount increased, the dough became more supple and easier to roll out. But because fat coats the proteins, inhibiting gluten formation, too much oil once again weakened the dough’s structure, leading to excess starch loss in the water and a compromised texture. I found my upper limit at 2 tablespoons of oil.

I was finally getting somewhere, but this dough was still far from user-friendly.

THAT’S ALL, YOLKS

Up to this point I had tried adding water, protein (from egg whites), and fat to my dough, but I hadn’t experimented with the one ingredient that contains all three: yolks. Many pasta doughs substitute yolks for some of the whole eggs, because while they still contain about 50 percent water, they are also loaded with fat and emulsifiers, both of which limit gluten development. Unlike doughs made with cake flour or excessive amounts of oil, dough made with extra yolks still has plenty of structure thanks to the coagulation of the egg proteins. To 2 cups of flour, two whole eggs (I ditched one whole egg from the traditional formula), and 2 tablespoons of olive oil, I kept adding yolks until I had a truly soft, easy-to-work dough that boiled up nice and tender. The magic number proved to be six extra yolks.

This dough took on a beautiful yellow hue, yielded to gentle pressure with a rolling pin, and cooked up into delicate ribbons with a springy bite. While tasters had been concerned that the pasta would taste too eggy, they needn’t have feared. The sulfurous compounds responsible for the flavor we associate with eggs reside primarily in the whites, not the yolks.

Finally, I turned my attention to finding the best way to rest, roll, and cut the pasta.

A LITTLE R&R

After being mixed, pasta dough is often rested for 20 to 30 minutes to allow the flour to hydrate and the gluten to cross-link into a network and then relax. Would a longer rest be even better? To find out, I let the next batch sit at room temperature for an extended period of time, cutting and rolling out pieces every 30 minutes. After an hour, my dough was significantly more malleable—and it continued to soften over the next three hours (four hours of resting time was ideal, though not critical for success).

This dough was worlds away from the dense blocks I’d struggled with in the past, but it still required a bit of technique to roll out. I knew I needed to avoid using too much bench flour: A little cling is a good thing, as it prevents the dough from springing back too easily. Plus, as I’d already learned, excess flour doesn’t get incorporated into the dough and turns the surface of the pasta coarse and gummy. With all that in mind, I first cut the dough into six manageable pieces. Working with one at a time, I used my hands in combination with a rolling pin to make the dough into a 6 by 20-inch rectangle.

From here, the possibilities were limitless. For ribbon-style pasta, I allowed the sheets to dry on kitchen towels until firm around the edges (a step that enabled me to avoid dusting with more flour) before folding them up in 2-inch intervals and slicing crosswise to the desired thickness.

With dough that’s this easy to roll out and that cooks up into wonderfully springy, delicate noodles, I’d wager that even cooks with pasta machines might be tempted to leave them in the cabinet.

Fresh Pasta without a Machine

MAKES 1 POUND; SERVES 4 TO 6

If using a high-protein all-purpose flour such as King Arthur, increase the number of egg yolks to seven. The longer the dough rests in step 2, the easier it will be to roll out. When rolling out the dough, avoid adding too much flour, which may result in excessive snapback. To make the pasta ahead, follow the recipe through step 5, transfer the baking sheet of pasta to the freezer, and freeze until the pasta is firm. Transfer to a zipper-lock bag and store for up to two weeks. Cook frozen pasta straight from the freezer as directed in step 6.

2 cups (10 ounces) all-purpose flour, plus extra as needed

2 large eggs plus 6 large yolks

2 tablespoons olive oil

1 tablespoon salt

1 recipe sauce (recipes follow)

1. Process flour, eggs and yolks, and oil in food processor until mixture forms cohesive dough that feels soft and is barely tacky to touch, about 45 seconds. (If dough sticks to fingers, add up to ¼ cup flour, 1 tablespoon at a time, until barely tacky. If dough doesn’t become cohesive, add up to 1 tablespoon water, 1 teaspoon at a time, until it just comes together; process 30 seconds longer.)

2. Turn dough ball onto dry counter and knead until smooth, 1 to 2 minutes. Shape dough into 6-inch-long cylinder. Wrap in plastic wrap and let rest at room temperature for at least 1 hour or up to 4 hours.

3. Cut cylinder crosswise into 6 equal pieces. Working with 1 piece of dough at a time (rewrap remaining dough), dust both sides with flour, place cut side down on clean counter, and press into 3-inch square. Using heavy rolling pin, roll into 6-inch square. Dust both sides of dough lightly with flour. Starting at center of square, roll dough away from you in 1 motion. Return rolling pin to center of dough and roll toward you in 1 motion. Repeat rolling steps until dough sticks to counter and measures roughly 12 inches long. Lightly dust both sides of dough with flour and continue to roll until dough measures roughly 20 inches long and 6 inches wide, frequently lifting dough to release it from counter. (You should be able to easily see outline of your fingers through dough.) If dough firmly sticks to counter and wrinkles when rolled out, dust dough lightly with flour.

4. Transfer pasta sheet to clean dish towel and let stand, uncovered, until firm around edges, about 15 minutes; meanwhile, roll out remaining dough.

5. Starting with 1 short end, gently fold pasta sheet at 2-inch intervals until sheet has been folded into flat, rectangular roll. Using sharp chef’s knife, slice crosswise into 3⁄16-inch-thick noodles. Use your fingers to unfurl pasta and transfer to baking sheet. Repeat folding and cutting remaining sheets of dough. Cook noodles within 1 hour or freeze.

6. Bring 4 quarts water to boil in large pot. Add pasta and salt and cook until tender but still al dente, about 3 minutes. Reserve 1 cup cooking water, then drain pasta and return it to pot. Toss with sauce and serve immediately.

sauces

Olive Oil Sauce with Anchovies and Parsley

MAKES 1 CUP; ENOUGH FOR 1 POUND PASTA

⅓ cup extra-virgin olive oil

2 garlic cloves, minced

2 anchovy fillets, rinsed, patted dry, and minced

Salt and pepper

2 tablespoons chopped fresh parsley

4 teaspoons lemon juice

1. Heat oil in 12-inch skillet over medium-low heat until shimmering. Add garlic, anchovies, ½ teaspoon pepper, and ⅛ teaspoon salt; cook until fragrant, about 30 seconds. Remove pan from heat and cover to keep warm while cooking pasta.

2. To serve, return pan to medium heat. Add cooked pasta, ½ cup reserved cooking water, parsley, and lemon juice; toss to combine, adjusting consistency with remaining reserved cooking water as needed. Season with salt and pepper to taste, and serve immediately.

MAKES 3 CUPS; ENOUGH FOR 1 POUND PASTA

Watch the butter closely so that the solids don’t burn.

1 (28-ounce) can whole peeled tomatoes

4 tablespoons unsalted butter, cut into 4 pieces

2 garlic cloves, minced

½ teaspoon sugar

Salt and pepper

2 teaspoons sherry vinegar

3 tablespoons chopped fresh basil

Grated Parmesan cheese

1. Process tomatoes and their juice in food processor until smooth, about 30 seconds. Melt 3 tablespoons butter in 12-inch skillet over medium-high heat, swirling occasionally, until butter is dark brown and releases nutty aroma, about 1½ minutes. Stir in garlic and cook for 10 seconds. Stir in processed tomatoes, sugar, and ½ teaspoon salt and simmer until sauce is slightly reduced, about 8 minutes. Remove pan from heat; whisk in vinegar and remaining 1 tablespoon butter. Season with salt and pepper to taste; cover to keep warm while cooking pasta.

2. To serve, return pan to medium heat. Add cooked pasta, ¼ cup reserved cooking water, and basil; toss to combine, adjusting consistency with remaining reserved cooking water as needed. Season with salt and pepper to taste, and serve immediately with Parmesan.

MAKES 2 CUPS; ENOUGH FOR 1 POUND PASTA

1½ cups walnuts

¾ cup dry white wine

½ cup heavy cream

1 ounce Parmesan cheese, grated (½ cup)

Salt and pepper

¼ cup minced fresh chives

1. Toast walnuts in 12-inch skillet over medium heat until golden and fragrant, 2 to 4 minutes. Process 1 cup walnuts in food processor until finely ground, about 10 seconds. Transfer to small bowl. Pulse remaining ½ cup walnuts in food processor until coarsely chopped, 3 to 5 pulses. Bring wine to simmer in now-empty skillet over medium-high heat; cook until reduced to ¼ cup, about 3 minutes. Whisk in cream, walnuts, Parmesan, ¼ teaspoon salt, and ½ teaspoon pepper. Remove pan from heat and cover to keep warm.

2. To serve, return pan to medium heat. Add pasta, ½ cup reserved cooking water, and chives; toss to combine, adding remaining cooking water as needed to adjust consistency. Season with salt and pepper to taste; serve immediately.

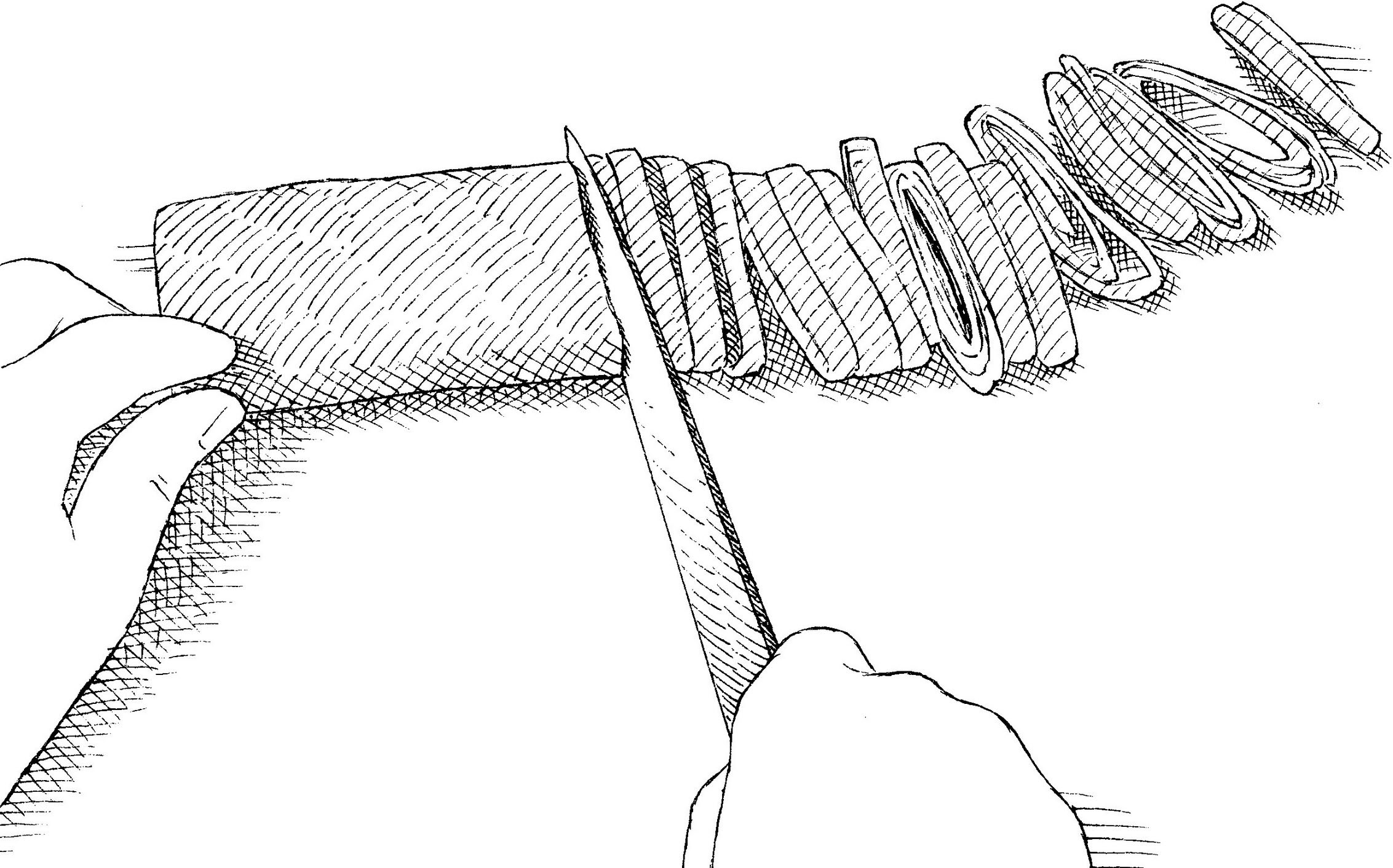

ROLLING AND CUTTING PASTA DOUGH BY HAND

To roll pasta by hand, we start with a soft, malleable dough and work with one small, manageable piece at a time.

1. WORK WITH SMALL PIECES Divide rested dough into 6 equal pieces. Working with 1 piece at a time (keeping other dough pieces covered), dust with flour, then press cut side down into 3-inch square. With rolling pin, roll into 6-inch square and dust with flour.

2. ROLL FROM CENTER Roll dough to 6 by 12 inches, rolling from center of dough one way at a time; dust with flour. Continue rolling to 6 by 20 inches, lifting frequently to release from counter. Transfer dough to kitchen towel and air-dry for 15 minutes.

3. FOLD AND CUT INTRO STRIPS Starting with short end, gently fold dried sheet at 2-inch intervals to create flat roll. Slice into 3/16-inch-thick noodles. Use your fingers to unfurl pasta; transfer to baking sheet.

REINVENTING MACARONI AND CHEESE

PAM ANDERSON WITH KAREN TACK, January/February 1997

Macaroni and cheese has always been on my “must-explore” list. It’s just eaten too often in this country for us to ignore it. Kids in particular say yes to macaroni and cheese when they turn up their noses at everything else. Unfortunately, it’s the boxed version, complete with orange cheese powder, that’s made most often.

There are two distinct styles of macaroni and cheese: béchamel-based, in which macaroni is blanketed with a cheesy white sauce, usually topped with crumbs, and baked. The other variety, the kind my mother always made, is custard-based. In this style, a mixture of egg and milk is poured over layers of grated cheese and noodles. As the dish bakes, the eggs, milk, and cheese set into a custard. It can also be topped with bread crumbs, although my mom always sprinkled crushed saltine crackers over hers.

Evaporated milk creates a perfect creamy base for a macaroni and cheese that is almost as quick to make as boxed versions.

This should be a wonderful, satisfying dish, but many of the recipes I looked at seemed tired, leaden, and uninspired. After compiling a bunch of test recipes, I began to wonder if I really did still love this simple dish. Then I read the chapter on macaroni and cheese in John Thorne’s Simple Cooking (1989). “As it happens,” he begins, “I’m very fond of macaroni and cheese, and keep a special spot in my heart for cooks who genuinely love it: they are not that many.” After reading his four-page essay, I suspected that his recipe for macaroni and cheese was the real one, the others mere shadows.

NO COMPARISON

Making the dish confirmed that John Thorne’s macaroni and cheese was the best. I could do our usual in-depth testing, but I knew up front I wouldn’t come up with anything better.

Thorne’s recipe starts with macaroni cooked just shy of al dente and then tossed with butter. Evaporated milk, hot sauce, dry mustard, eggs, and lots of cheese are stirred into the noodles. The combination is baked for 20 minutes, with cheese and milk additions and a thorough stir every 5 minutes. Frequent stirring allows the eggs to thicken without setting, which results in an incredibly silky sauce. During cooking, the sauce settles into the tubular openings, offering a burst of cheese with each new bite. I was delighted. Never had I gotten a dish right on the first try. For once, someone else had done the homework.

Just to confirm my belief, I baked the two styles of macaroni and cheese defined earlier: one with a cheese-flavored béchamel sauce, the other thickened with eggs, milk, and cheese. Neither compared to Thorne’s dish. The béchamel-based version was grainy and tasted exactly as Thorne predicted: not like macaroni and cheese, but “macaroni with cheese sauce.”

Of the two macaroni and cheeses, I preferred the cheesier-flavored custard version. Because this custard-based macaroni and cheese was simply a variant of Thorne’s recipe, I thought I might offer it as an alternative to stirring. A side-by-side tasting proved the two macaroni and cheese dishes to be very different, however, and the stirred version remained superior in my mind. Compared to the luxuriously silky cheese sauce of the stirred macaroni, the baked egg, milk, and cheese formed a dry custard that set around the noodles. Thorne’s recipe was clearly still the best.

PUTTING IT TO THE TEST

The competition ruled out, I moved forward to study Thorne’s recipe a little more closely. Did the dish really require evaporated milk or was this an idiosyncrasy of the late ’30s when the recipe was first published in The Home Comfort Cook Book (1937). Wouldn’t regular milk or half-and-half work equally well? What other cheeses, besides sharp cheddar, would taste good?

I had also thought of a few possible refinements. First, I found that at the end of the 20 minutes of baking, the dish was hot, but hardly piping. By the time a person had consumed his or her portion, the cheese sauce had cooled and set a bit. I also missed the contrasting textures of crunchy bread crumbs and soft noodles and sauce. Thorne’s advice to sprinkle the macaroni and cheese with crumbled common crackers was one possibility, but I was looking for something a little more finished. Although I liked the rich, full cheese flavor Thorne achieved with a whole pound of cheese, I found myself full after only a few bites. I wanted to find out if the dish was just as good with less cheese.

After testing the recipe with whole and low-fat milks and half-and-half, I realized that evaporated milk was not an ingredient thoughtlessly left in. All the macaroni and cheese dishes made with fresh milk curdled a bit, resulting in a chalky, grainy texture. The one made with evaporated milk remained silky-smooth. The evaporation and sterilization process stabilizes the milk, which in turn, stabilizes the macaroni and cheese.

After making the dish with Vermont, New York, and Wisconsin cheddars, I preferred the less sharp Wisconsin variety. Because the recipe calls for such a large quantity, a slightly milder cheese is preferable. Further testing confirmed this point. Macaroni and cheese made with Gruyère was so strong I couldn’t even eat it. To my surprise, highly processed cheeses such as American performed quite well in this dish. Much like evaporated milk, the more processing, the more stable the cheese and the more creamy the dish. For flavor, use cheddar; for texture, buy American. I also found the dish did not suffer with only 12 ounces of cheese compared to the 1 pound called for in the original recipe.

I found that I could not remedy the dish’s lukewarm temperature problem by leaving it in the oven much longer than the suggested 20 minutes. Doing so ran the risk of curdling the eggs, and the dish started to develop a subtle grainy texture. So I tried two solutions, both of which worked. To avoid pouring hot macaroni into a cold dish, I stuck the pan in the preheating oven. By the time the macaroni was ready to drain, the pan emerged from the oven pot-holder hot. Warming the milk a bit before mixing it with the pasta also gave the dish a warm head start.

As suggested by Thorne, crisp common crackers sprinkled over the macaroni and cheese offer a much-needed foil to the rich, unctuous sauce. For a further refinement, I toasted some fresh buttered bread crumbs.

After I shared this recipe with friend and cooking colleague Stephen Schmidt, he reported back his finding that if one used a heavy-bottomed pot and cooked it over low heat, it was possible to forgo the baking step altogether and make the macaroni and cheese on top of the stove in less than 15 minutes. I tried his suggestion and found the stovetop macaroni and cheese to be as good as the baked one. By following his method, it was possible to complete this dish in virtually the same amount of time it would take to make the boxed stuff. And considering the same preparation time and a few dollars more buy you the difference between an institutional experience and the real McCoy, I would call this recipe a no-brainer.

SERVES 4

You can skip the bread crumbs and sprinkle the dish with crumbled common crackers or saltines, if desired.

Bread Crumbs

3 slices hearty white sandwich bread, torn into quarters

2 tablespoons unsalted butter, melted

Salt

Macaroni and Cheese

2 large eggs

1 (12-ounce) can evaporated milk

1 teaspoon dry mustard, dissolved in 1 teaspoon water

Salt

¼ teaspoon pepper

¼ teaspoon hot sauce

8 ounces elbow macaroni (2 cups)

4 tablespoons unsalted butter

12 ounces sharp cheddar, American, or Monterey Jack cheese, shredded (3 cups)

1. For the bread crumbs: Pulse bread in food processor to coarse crumbs, about 10 pulses. Melt butter in 12-inch skillet over medium heat. Add bread crumbs and cook, stirring often, until beginning to brown, 4 to 6 minutes. Season with salt to taste; set aside.

2. For the macaroni and cheese: Mix eggs, 1 cup evaporated milk, mustard mixture, ½ teaspoon salt, pepper, and hot sauce in bowl.

3. Meanwhile, bring 2 quarts water to boil in Dutch oven. Add pasta and 1½ teaspoons salt and cook, stirring often, until al dente. Drain pasta and return to pot over low heat. Add butter and toss to melt.

4. Add egg mixture and three-quarters of cheese to pasta and toss until thoroughly combined and cheese starts to melt. Gradually add remaining evaporated milk and remaining cheese, stirring constantly, until mixture is hot and creamy, about 5 minutes. Serve immediately, sprinkling individual portions with toasted bread crumbs.

variation

Add ¼ cup grated Parmesan cheese to toasted bread crumbs. Adjust oven rack 6 inches from broiler element and heat broiler. Transfer macaroni and cheese mixture to 13 by 9-inch broiler-safe baking dish and sprinkle with bread-crumb mixture. Broil until topping turns deep golden brown, 1 to 2 minutes. Let casserole cool for 5 minutes before serving.

WHAT IS EVAPORATED MILK?

Evaporated milk is merely milk that is gently heated in a vacuum (a process called forewarming) so that 60 percent or more of the water evaporates. The resulting thick liquid is then sterilized and canned. Evaporated milk has about twice the concentration of fat and protein as regular whole milk.

Since evaporated milk is impervious to curdling, it guarantees a silky, smooth texture in our Stovetop Macaroni and Cheese recipe. The reason for this is the process by which this product is made. In regular milk, the main proteins, namely large casein molecules, tend to clump together when exposed to heat. The forewarming process makes the proteins more resistant to curdling. During forewarming, the big casein molecules are surrounded by smaller molecules of whey protein, and the whey proteins get in the way of the clumping of the casein molecules. Salts and other additives also interfere with the clumping of the casein molecules. Salts (disodium phosphate and/or sodium citrate) improve the ability of the proteins in the mix to retain water (the release of water is another symptom of curdling). Carrageenan gum may also be added to the finished product to prevent fat separation during storage.

There’s something great about a quick tomato sauce: fast, furious, and fresh. But what a quick sauce offers in convenience it lacks in the complexity of a slowly simmered tomato sauce, the best known of which may be marinara.

Unfortunately, complexity of flavor means lots of time in the kitchen, which is in short supply on a Tuesday night. My goal was to produce a multidimensional sauce in less than an hour, starting the clock the moment I entered the kitchen and stopping it when dinner was on the table. Weeding through hundreds of marinara recipes, I settled on testing not only a variety of “quick” versions but also some that were cooked for longer than an hour. The differences were readily apparent. The quick sauces were generally thin and lacked depth of flavor. The long-cooked sauces got the complexity right, but most relied on an ambitious laundry list of ingredients to achieve it—not to mention a lot of time. The sauce I was after had to capture some of these robust flavors within the confines of fairly quick cooking.

A TRICK WITH TOMATOES

Because prime fresh tomatoes are available for such a limited time during the year, I opted for canned. But which variety should I choose?

Crushed, pureed, and diced tomatoes offered the ultimate ease in sauce making: Open can, dump contents into pan. But all three options have downsides. Pureed tomatoes go into the can already cooked, which imparts a stale, flat flavor to the final sauce. Crushed tomatoes are generally packed in tomato puree: same problem. With these, my sauces came out tasting like unremarkable homemade versions of the jarred spaghetti sauces sold at the supermarket. With canned diced tomatoes, the problem was texture, not flavor. In the past, we’ve learned that manufacturers treat diced tomatoes with calcium chloride to keep them from turning to mush and losing their shape. That’s fine for many dishes, but for recipes in which a smooth consistency is desired, calcium chloride does its job too well, making the tomatoes harder to break down—and the resulting sauces oddly granular.

The only choice left, then, was canned whole tomatoes. (While whole tomatoes are also treated with calcium chloride, the chemical has direct contact with a much smaller percentage of the tomato.) The big drawback of using whole tomatoes in a sauce is that they have to be cut up. Chopping them on a cutting board was a mess. The solution was to dump the tomatoes into a strainer over a bowl and then hand-crush them, removing the hard core and any stray bits of skin.

That’s when I made the first of several decisions that would enable me to get long-simmered complexity in a short time. Most marinara recipes call for simply adding a can (or two) of tomatoes to the pot, juice and all—and some even call for throwing in a can of water. Now that I was separating the solids from the juice anyway, why not experiment with adding less of the reserved liquid? The trick worked: By adding only 2½ cups of the drained juice from two cans of whole tomatoes (rather than the full 3½ cups I had collected) and omitting the extra water, I managed to cut the simmering time by almost 20 minutes.

Up until now I had been following the standard marinara procedure of sautéing aromatics (onions and garlic) in olive oil in a saucepan before adding the tomatoes, liquid, and flavorings, then simmering. That’s fine if you have all day, but I had only an hour. So I switched from a saucepan to a skillet, hoping the greater surface area would encourage faster evaporation and, thus, faster concentration of flavors.

It was faster, all right—down to just under an hour—but I felt that the sauce could use gutsier tomato flavor. Not only was the solution simple, but it was the key step in giving my quick sauce the complexity of a long-simmered one. Before adding the liquids and simmering, I sautéed the tomato meats until they glazed the bottom of the pan. Only then did I add the liquids, a normally routine step that, by essentially deglazing the pan, added crucial flavor to my sauce.

BALANCING ACTS

It was time to develop more depth of flavor. Onions added a pleasant sweetness, but carrots added an earthy flavor that diminished that of the tomatoes. Sugar, added at the end of cooking, proved to be the working solution to balance the flavors: too much and my sauce began to taste like it came out of a jar; too little and the acidity overwhelmed the other flavors. Tasters loved the robust, complex flavor of red wine, and a mere ⅓ cup was just the right amount. But not just any bottle: Wines with a heavy oak flavor rated lower than those with little to no oak presence.

We use canned whole tomatoes in our quick marinara, reserving a few to add at the end for brightness.

I now had a good marinara ready to serve in less than an hour—about half the time of many recipes. Could I further bolster the complexity without adding minutes? On a hunch, I tried reserving a few of the uncooked canned tomatoes and adding them near the end of cooking. When I served this sauce alongside the earlier version, tasters were unanimous in their preference for the new sauce; just six tomatoes pureed into the sauce at the end added enough brightness to complement the deeper profile of the cooked sauce.

So far the sauce had little flavor from herbs beyond oregano. Fresh basil, also added at the end, contributed a floral aroma that complemented the sauce’s careful balance of sweet and acid.

Marinara Sauce

MAKES 4 CUPS; ENOUGH FOR 1 POUND PASTA

Because canned tomatoes vary in acidity and saltiness, it’s best to add sugar, salt, and pepper to taste just before serving. Chianti or Merlot works well for the dry red wine. We like a smoother marinara, but if you prefer a chunkier sauce, give it just three or four pulses in the food processor in step 4.

2 (28-ounce) cans whole peeled tomatoes

3 tablespoons extra-virgin olive oil

1 onion, chopped fine

2 garlic cloves, minced

2 teaspoons minced fresh oregano or ½ teaspoon dried

⅓ cup dry red wine

3 tablespoons chopped fresh basil

Sugar

Salt and pepper

1. Pour tomatoes and their juice into strainer set over large bowl. Open tomatoes with your hands and remove seeds and fibrous cores; let tomatoes drain excess liquid, about 5 minutes. Remove ¾ cup tomatoes from strainer and set aside. Set aside 2½ cups tomato juice and discard remainder.

2. Heat 2 tablespoons oil in 12-inch skillet over medium heat until shimmering. Add onion and cook until softened and lightly browned, 5 to 7 minutes. Stir in garlic and oregano and cook until fragrant, about 30 seconds.

3. Stir in strained tomatoes and increase heat to medium-high. Cook, stirring often, until liquid has evaporated, tomatoes begin to stick to bottom of skillet, and brown fond forms around pan edges, 10 to 12 minutes. Stir in wine and cook until thick and syrupy, about 1 minute. Stir in reserved tomato juice, scraping up any browned bits. Bring to simmer and cook, stirring occasionally, until sauce is thick, 8 to 10 minutes.

4. Pulse sauce and reserved tomatoes in food processor until slightly chunky, about 8 pulses. Return sauce to now-empty skillet and stir in basil and remaining 1 tablespoon oil. Season with sugar, salt, and pepper to taste before serving.

GETTING SLOW-SIMMERED FLAVOR FAST

The best marinaras have lots of complexity—and demand lots of cooking time. Here’s how we speed up the process.

DRAIN JUICE A can of tomatoes has more juice than solids. We jump-start flavor concentration by draining off almost a cup of juice beforehand.

CARAMELIZE SOLIDS Caramelizing the tomato solids briskly in a large skillet before deglazing with liquid ingredients further deepens the flavor profile.

ADD RAW TOMATOES Reserving a few uncooked tomatoes to add at the end contributes an extra note of freshness to the cooked sauce.

ADD SUGAR Seasoning the finished sauce with sugar in addition to the usual salt and pepper brings out the complexity of the wine and balances the acidity of the tomatoes.

MATCHING PASTA SHAPES WITH SAUCE

In Italy there is a fine art to matching pasta shapes and sauces, but in the test kitchen, we are a bit freer with the pairing and endorse just one general rule: you should be able to eat the pasta and sauce easily in each mouthful. This means that the texture and consistency of the sauce should work with the pasta shape.

Long strands are best with smooth sauces or pestos or light sauces, such as oil and garlic. In general, wider long noodles, such as fettuccine, can more easily support slightly chunkier sauces than can very thin noodles like spaghetti. Wide pastas like fettuccine or tagliatelle are also well suited to creamy sauces like Alfredo. Short tubular or molded pasta shapes do an excellent job of trapping chunkier sauces. Sauces with very large chunks are best with shells, rigatoni, or other large tubes. Sauces with small to medium chunks pair well with fusilli or penne. Since our Marinara Sauce can be as smooth or chunky as you choose (depending on how many times you pulse it in the food processor), be sure to pair your final sauce with an appropriate pasta shape. If pulsing the sauce eight times as called for in the recipe, we like to use a long-strand pasta like spaghetti.

More light and refreshing than a cream-based sauce or a chunky ragù, pesto makes a top-notch accompaniment to pasta during the sultry summer months. There’s nothing complicated about this uncooked Ligurian sauce, which consists of processed fresh basil, garlic, pine nuts, Parmigiano-Reggiano cheese, and olive oil. And tossing it with hot, just-cooked pasta couldn’t be easier. But numerous issues arise once pesto is added to a pasta salad. The refrigerator dulls the color and flavor of the pesto, which turns greasy and clumpy as the pasta cools.

PERFECTING THE PESTO

I began by trying varying ratios of the five integral ingredients: basil, garlic (blanched briefly to tame its harsh bite), Parmesan cheese, olive oil (extra-virgin), and pine nuts (toasted to enhance their nutty flavor). I had to use a lot of basil (between 3 and 4 packed cups) to achieve decent herbal flavor and enough bulk. But when made even a few hours ahead of time, the basil turned dark and muddy. Adding another green element seemed the obvious solution. Parsley is a common trick, but I needed to use so much that it began to compete with the basil flavor. I’d seen frozen chopped spinach used, but while it turned the pesto a nice, bright green, it also made the texture stringy. The easy solution was to add a small amount of fresh baby spinach, which provided a lovely bright green color and smooth texture without interfering with the basil flavor.

Fresh baby spinach keeps our pesto bright green, and a small amount of mayonnaise provides a luscious texture.

While the relatively thin consistency of traditional pesto might be fine for hot noodles, a thicker, creamier pesto was in order for room-temperature pasta. But no matter how much I fiddled with ingredient amounts, the pesto was always less than optimally creamy. Upping the quantity of cheese and pine nuts thickened the pesto, but also made it salty, gritty, and pasty. Adding more oil to smooth out the mixture only made the pesto greasy.

Since this dish wasn’t exactly an Italian classic, I decided to borrow a standard ingredient used in many American pasta salads: mayonnaise. The creamy condiment served as the perfect binder—so long as it was used in moderation. Six tablespoons was enough to provide a luscious texture.

PREPARING THE PASTA

The best pasta shapes for this dish have a textured surface with a concave nook or two that can trap the pesto and keep it from sliding off. With its indented center and jagged edges, farfalle made an excellent partner. Unlike hot pasta, which should generally be cooked until al dente, the pasta used in salads should cook slightly longer, until tender.

When the pesto was added straight to just-cooked pasta, it took an hour to reach room temperature. The hot pasta also “cooked” the basil, deadening its impact. Rinsing the pasta in cold water cooled it down quickly but made the surface of the pasta too slick to hold on to the pesto. The solution was to let the pasta cool in a single layer on a rimmed baking sheet, tossing it in a splash of oil to prevent sticking.

Finally, I added lemon juice to cut through the richness. An extra ½ cup of toasted pine nuts folded into the pesto-coated pasta added a sweet, nutty note and textural contrast. Small cherry or grape tomatoes contributed color and bursts of freshness. Finally, I had translated a Ligurian mainstay into an American picnic classic.

SERVES 8 TO 10

Other pasta shapes can be substituted for the farfalle.

2 garlic cloves, unpeeled

1 pound farfalle

Salt and pepper

5 tablespoons extra-virgin olive oil

3 cups fresh basil leaves, lightly bruised

1 cup baby spinach

¾ cup pine nuts, toasted

2 tablespoons lemon juice

1½ ounces Parmesan cheese, grated (¾ cup), plus extra for serving

6 tablespoons mayonnaise

12 ounces cherry tomatoes, quartered

1. Bring 4 quarts water to boil in large pot. Add garlic and cook for 1 minute. Remove garlic with slotted spoon and rinse under cold water to stop cooking. Let garlic cool slightly, then peel and chop fine; set aside.

2. Add pasta and 1 tablespoon salt to boiling water and cook, stirring often, until tender. Reserve ¼ cup cooking water. Drain pasta, toss with 1 tablespoon oil, and spread in single layer on rimmed baking sheet. Let pasta and cooking water cool to room temperature, about 30 minutes.

3. Process basil, spinach, ¼ cup pine nuts, lemon juice, garlic, and 1 teaspoon salt in food processor until smooth, about 30 seconds, scraping down sides of bowl as needed. Add Parmesan, mayonnaise, and remaining ¼ cup oil and process until thoroughly combined; transfer to large bowl.

4. Toss cooled pasta with pesto, adding reserved cooking water, 1 tablespoon at a time, until pesto evenly coats pasta.

5. Fold in remaining ½ cup pine nuts and tomatoes. Season with salt and pepper to taste. Serve.

A plate of pasta and a glass of wine are a natural pairing. But I’d long heard references to a dish called spaghetti al vino rosso that exploits their affinity: You cook the pasta in wine instead of water and then top it off with olive oil, a bit of butter, and a sprinkling of cheese. The concept is not without precedent: Cooking rice in a wine-spiked broth transforms it from a blank slate into a complex and wonderful risotto. I figured the same could be true of pasta if I could just pin down a reliable recipe.

Easier said than done. Recipes were hard to track down, and the ones I found were all over the map. One called for boiling the spaghetti in a 50/50 mix of water and red wine that was then (wastefully) poured down the drain. In another, a whole bottle of wine was reduced to a glaze (eliminating all of its pleasant booziness) and used to coat spaghetti cooked separately in water. A third approach resembled risotto-making and seemed the most promising: the pasta was parcooked in water and then transferred to a skillet where about 2 cups of wine were added in increments so that the pasta could absorb the wine as it finished cooking.

Reducing some white wine into a glaze and adding the rest slowly to the pasta as it finishes cooking makes for a balanced dish.

But the dish wasn’t perfect. While tasters liked the pasta’s lively wine kick, they also found the dish tannic. The real deal breaker, though? Its unappetizing purple-gray color.

My research indicated that this was a dish almost always made with red wine. Nevertheless, I wondered what would happen if I swapped the red wine for white, which would get rid of the hideous mauve color. I tried it and found that the switch also solved the tannin problem, since such flavors come from the grape skins, which are removed early in the process of making white wine. But now I had a new issue: The spaghetti wasn’t as robustly flavored.

I thought back to the method that reduced a full bottle of wine in a skillet. I experimented with reducing about a third of a bottle of white wine to a glaze while the spaghetti parcooked in water. Then I introduced the partially cooked spaghetti to the glaze and added the remainder of the bottle gradually, stirring as the spaghetti finished cooking. The glaze provided subtle complexity, but we agreed that this spaghetti was going to need more than just olive oil, butter, and Pecorino Romano to hold its own.

Garlic and red pepper flakes were easily incorporated into the glaze. Crisp, salty pancetta sprinkled over the pasta before serving was also a shoo-in. Arugula’s peppery notes complemented the other flavors perfectly. Pine nuts added textural contrast.

My spaghetti was almost complete, but it seemed a tad dry. I had been stirring in some cold butter along with reserved pasta water at the end, but the resulting sauce was too insubstantial. A little bit of cream was just the thing to bulk it up.

Spaghetti al Vino Bianco

SERVES 4

Use a good-quality dry white wine but avoid a heavily oaked white such as Chardonnay. If the wine reduction is too sharp in step 2, season it to taste with up to 1 tablespoon of sugar, adding it in 1-teaspoon increments.

1 tablespoon extra-virgin olive oil

4 ounces pancetta, cut into ¼-inch pieces

2 garlic cloves, minced

Pinch red pepper flakes

1 (750-ml) bottle dry white wine

Salt and pepper

Sugar

1 pound spaghetti

5 ounces (5 cups) baby arugula

1 ounce Pecorino Romano cheese, grated (½ cup), plus extra for serving

⅓ cup heavy cream

¼ cup pine nuts, toasted and chopped coarse

1. Heat oil and pancetta in 12-inch skillet over medium-high heat; cook until pancetta is browned and crispy, 4 to 5 minutes. Using slotted spoon, transfer pancetta to paper towel–lined plate. Pour off all but 2 tablespoons fat from skillet.

2. Reduce heat to medium-low and add garlic and pepper flakes to skillet. Cook, stirring frequently, until garlic begins to turn golden, 1 to 2 minutes. Carefully add 1½ cups wine and increase heat to medium-high. Cook until wine is reduced to ½ cup, 8 to 10 minutes. Add ½ teaspoon salt. Season with up to 1 tablespoon sugar to taste if needed.

3. Bring 4 quarts water to boil in large pot. Add pasta and 1 tablespoon salt and cook, stirring often, until pasta is flexible but not fully cooked, about 4 minutes. Reserve 2 cups cooking water, then drain pasta.

4. Transfer pasta to skillet with reduced wine. Place skillet over medium heat; add ½ cup unreduced wine and cook, tossing constantly, until wine is fully absorbed. Continue to add remaining wine, ½ cup at a time, tossing constantly, until pasta is al dente, about 8 minutes. (If wine is absorbed before spaghetti is fully cooked, add ½ cup reserved cooking water at a time to skillet and continue to cook.)

5. Remove skillet from heat. Place arugula on top of pasta; pour ¼ cup reserved cooking water over arugula, cover, and let stand for 1 minute. Add ¼ cup Pecorino and cream; toss until sauce lightly coats pasta and arugula is evenly distributed. Season with salt and pepper to taste. Transfer to platter and sprinkle with pine nuts, pancetta, and remaining ¼ cup Pecorino. Serve immediately, passing extra Pecorino separately.

At the end of summer, I inevitably find myself with a glut of beautiful garden tomatoes, both small and large. As a result, I’m always searching for ways to use them beyond salads. Puttanesca, that most boisterous of classic Italian sauces (legend has it that it was invented by Neapolitan prostitutes on break between customers), is one of my favorite tomato-based sauces.

I love the clash of flavors that this sauce presents: Spicy pepper flakes, pungent garlic, and salty anchovies, olives, and capers meet up with clean-tasting fresh herbs and tangy-sweet tomatoes. Putting my harvest to use in this quick sauce would address the generic “cooked” quality that stems from using canned tomatoes, the usual choice for this dish. I wasn’t aiming for a no-cook sauce, but I did want a fresher puttanesca—one that retained the fruits’ clean-tasting sweetness alongside the richer, more assertive flavors that are the essence of this dish.

A FRESH START

My first step was trying several varieties of tomato in a basic puttanesca: minced garlic and anchovies (anchovy paste, for convenience), red pepper flakes, chopped black olives, and capers, all sautéed in olive oil. Juicy larger tomatoes required me to reduce the sauce to avoid a watery consistency, but when I did, its fresh flavor all but disappeared. But low-moisture grape (or cherry) tomatoes, once halved, need very little simmering time to reduce to a sauce-like consistency. Availability was on my side, too: Not only is my garden full of these tomatoes by summer’s end but they’re also consistently decent in supermarkets year-round.

There was a downside: The larger ratio of skin to flesh meant that my sauce was full of chewy skins. Since I wasn’t about to skin dozens of tiny tomatoes, I gave them a quick blitz in a blender, which pulverized the skins completely.

Unfortunately, doing so also caused them to shed more moisture—not as much as big tomatoes but enough that it seemed I would have to revert to a longer simmering time. What if I drained the pureed tomatoes in a strainer before adding them to the sauce? That way, I could discard the exuded liquid.

But I quickly realized my faulty thinking. The majority of tomato flavor resides in the juice, jelly, and seeds, so I’d essentially be throwing away the best part. The better approach was to briefly simmer the juice to concentrate its flavor. Once it had reduced to ⅓ cup, I added the uncooked pulp along with the olives and capers. When the sauce was heated through, the bulk of the tomatoes had softened but still tasted fresh.

To give our sauce lots of fresh tomato flavor without a watery texture, we reduce the tomatoes’ juice and then add the pulp.

SALTY AND SOUR

Now to tame the rowdier ingredients: the olives and the capers. I tested common varieties of high-quality black olives. Salt-cured were too salty, but brine-cured kalamata and Gaeta, both of which were fruity and pleasantly crisp-tender, were equally excellent choices. I chopped them coarsely—any finer and the sauce turned a muddy brown. I did finely chop the capers, however, so that their briny punch hit every bite. A smidgen of dried oregano introduced complexity; ½ cup of minced fresh parsley offered freshness.

One final adjustment: Finding myself out of the standard spaghetti or linguine, I reached for campanelle. Tasters preferred the compact size and convoluted twists of this pasta, since it did a better job of trapping the coarse sauce. Plus, aesthetically it hinted at a summertime pasta salad, giving the dish an overall fresher appeal.

SERVES 4

We prefer to make this dish with campanelle, but fusilli and orecchiette also work. Very finely mashed anchovy fillets (rinsed and dried before mashing) can be used instead of anchovy paste.

3 tablespoons extra-virgin olive oil

4 garlic cloves, minced

1 tablespoon anchovy paste

¼ teaspoon red pepper flakes

¼ teaspoon dried oregano

1½ pounds grape or cherry tomatoes

1 pound campanelle

Salt

½ cup pitted kalamata olives, chopped coarse

3 tablespoons capers, rinsed and minced

½ cup minced fresh parsley

1. Combine oil, garlic, anchovy paste, pepper flakes, and oregano in small bowl. Process tomatoes in blender until finely chopped but not pureed, 15 to 45 seconds. Transfer to fine-mesh strainer set in large bowl and let drain for 5 minutes, occasionally pressing gently on solids with rubber spatula to extract liquid (this should yield about ¾ cup). Reserve tomato liquid and pulp.

2. Bring 4 quarts water to boil in large pot. Add pasta and 1 tablespoon salt and cook, stirring often, until al dente. Reserve 1 cup cooking water, then drain pasta and return it to pot.

3. While pasta is cooking, cook garlic-anchovy mixture in 12-inch skillet over medium heat, stirring frequently, until garlic is fragrant but not browned, 2 to 3 minutes. Add tomato liquid and simmer until reduced to ⅓ cup, 2 to 3 minutes. Add olives, capers, and tomato pulp and cook until just heated through, 2 to 3 minutes. Stir in parsley.

4. Add sauce to pasta and toss to combine, adjusting consistency with reserved cooking water as needed. Season with salt to taste, and serve immediately.

You’d never know that pasta primavera, a pseudo-Italian dish that appears on virtually every chain restaurant menu, actually has roots in French haute cuisine. The usual reproduction—a random jumble of produce tossed with noodles in a heavy, flavor-deadening cream sauce—tastes nothing like spring. Surprisingly, when I dug up the original recipe from New York’s famed Le Cirque restaurant, my colleagues found it wasn’t all that inspiring either, despite taking about 2 hours to prepare and dirtying five pans. First, the vegetables (which had been painstakingly blanched one by one) were bland. Second, the cream-, butter-, and cheese-enriched sauce dulled flavor and didn’t really unify the dish. If I wanted a true spring-vegetable pasta—with a few thoughtfully chosen vegetables and a light, but full-bodied sauce that clung well to the noodles and brought the dish together—I’d have to start from the beginning.

GROWING VEGETABLE FLAVOR

Before I began cooking, I had some produce shopping to do. Freely testing my way through various spring staples, I landed on a pair of classics—asparagus and green peas—plus garlic and leeks for their aromatic depth and sweetness, chives for their fresh bite and onion-y overtones, and mint, a natural match for peas.

Simmering broth with the vegetable scraps and then using the enhanced broth to cook the pasta infuses this dish with flavor.

I also decided at the outset to do away with the tedious blanching step. I found that by sautéing the vegetables in stages in a large Dutch oven, I was able to ensure that each one maintained its crisp-tender texture while taking on a touch of flavorful browning. First went the leeks, followed by the chopped asparagus, the minced garlic, and finally the frozen baby peas, which needed only a minute over the heat to lend sweetness to the mix.

But as I’d learned from the original recipe, simply tossing sautéed vegetables with the pasta didn’t add up to a dish any greater than the sum of its parts. What I needed was a way to tie the dish together and give it depth of flavor—a job that’s usually reserved for the sauce. The chicken broth used in the original recipe didn’t seem like the best way to enhance the vegetable flavor, so I swapped it for vegetable broth. To give it depth, I simmered the broth with the pile of scraps I’d peeled and trimmed away from the vegetables (the green parts of the leeks and the woody ends of the asparagus), along with some extra garlic and peas. But once I’d strained the broth and added the cream and butter—necessary to give the sauce body—any flavor advantage I had gained was lost. I tried cutting back on the dairy, but the result was so thin that it just slid off the pasta. The bottom line: The vegetables alone weren’t enough to give the dish flavor.

THE POT THICKENS

I was thinking of calling it quits when a colleague reminded me that Italian cookery has a tradition of parboiling pasta in water and then letting it finish cooking for a minute or two in whatever sauce is being served. The technique has a twofold benefit: As the pasta cooks, it absorbs some of the sauce and takes on its flavors. In exchange, the noodles release some of their starches into the sauce, which helps build body. It wouldn’t hurt to try this approach. I prepared another batch, this time boiling the pasta (spaghetti, for now) for a couple of minutes in the water, draining it, and then allowing it to finish cooking in my enhanced vegetable broth. Everyone agreed that while this was a step in the right direction, the results were still too subtle.

Then a thought occurred to me: If I was going to add the pasta to the broth eventually, why not get the full benefit of the broth’s flavor and use it to cook the pasta from the start? The concept was nothing new, of course: It’s a classic risotto technique, in which the rice and broth work together to produce a glossy, full-bodied “sauce” that thoroughly flavors and coats each grain. When I tried the approach with pasta, the results weren’t quite perfect, but they were promising: The noodles, which I had boiled in a modest 5 cups of liquid (4 cups of broth, 1 cup of water) until they were al dente and the Dutch oven was almost dry, emerged more flavorful and lightly coated with the silky, starchy pot liquor. In fact, the sauce was thick enough that I didn’t even need to add any cream or butter to give it body.

Now that I was on a roll, I wondered if I couldn’t stretch the risotto technique even farther. Traditionally, the raw rice grains “toast” for a few minutes in some hot fat before the liquid is added, taking on a nutty richness. Adapting this technique for my pasta recipe seemed like a natural move, except for the problem of the long spaghetti strands, which I’d need to break up first. It seemed easier to just change the shape of the noodle. After testing half a dozen shorter shapes, I opted for bell-shaped campanelle: They held on to the sauce nicely, without clinging to one another or compressing into a mass. (Bow tie–shaped farfalle and penne quills made fine substitutes.)

Now that I had the right pasta shape, I went back to the cooking technique. After sautéing the vegetables, I wiped out the pot, added a splash of extra-virgin olive oil, and toasted the pasta until it started to color. Continuing with the classic risotto method, I poured in some dry white wine (its crisp acidity would brighten the sauce), stirring the mixture until most of the liquid had cooked off, and added the hot broth and cranked up the heat to a boil. When I stuck in my fork about 10 minutes later, the results were remarkably improved: tender pasta pieces coated with a light but lustrous and creamy sauce that more than hinted at the sweet, grassy flavors of the vegetables.

Once the sautéed vegetables were incorporated, all the dish needed was a little flavor tweaking here and there. Along with the minced garlic, I added a dash of hot pepper flakes and, just before serving, a handful of grated Parmesan. Finally, I brightened the whole lot with a splash of lemon juice plus a handful of combined fresh chopped mint, chives, and lemon zest.

Nothing against the folks at Le Cirque, mind you, but unlike their original primavera, my recipe—a match-up of grassy, bright-tasting vegetables and nutty pasta in a complex, richly flavored sauce—truly tasted like spring, and came together in a fraction of the time.

Spring Vegetable Pasta

SERVES 4 TO 6

Campanelle is our pasta of choice in this dish, but farfalle and penne are acceptable substitutes.

1½ pounds leeks, white and light green parts halved lengthwise, sliced ½ inch thick, and washed thoroughly, plus 3 cups coarsely chopped dark green parts, washed thoroughly

1 pound asparagus, tough ends trimmed, chopped coarse, and reserved; spears cut on bias into ½-inch lengths

2 cups frozen peas, thawed

4 cups vegetable broth

1 cup water

4 garlic cloves, minced

2 tablespoons minced fresh mint

2 tablespoons minced fresh chives

½ teaspoon grated lemon zest plus 2 tablespoons juice

6 tablespoons extra-virgin olive oil

Salt and pepper

¼ teaspoon red pepper flakes

1 pound campanelle

1 cup dry white wine

1 ounce Parmesan cheese, grated (½ cup), plus extra for serving

1. Bring leek greens, asparagus trimmings, 1 cup peas, broth, water, and half of garlic to boil in large saucepan. Reduce heat to medium-low and simmer gently for 10 minutes. While broth simmers, combine mint, chives, and lemon zest in bowl; set aside.

2. Strain broth through fine-mesh strainer into 8-cup liquid measuring cup, pressing on solids to extract as much liquid as possible (you should have 5 cups broth; add water as needed to equal 5 cups). Discard solids and return broth to saucepan. Cover and keep warm.

3. Heat 2 tablespoons oil in Dutch oven over medium heat until shimmering. Add leeks and pinch salt and cook, covered, stirring occasionally, until leeks begin to brown, about 5 minutes. Add asparagus spears and cook until asparagus is crisp-tender, 4 to 6 minutes. Add pepper flakes and remaining garlic and cook until fragrant, about 30 seconds. Add remaining 1 cup peas and continue to cook for 1 minute longer. Transfer vegetables to bowl and set aside. Wipe out pot with paper towels.

4. Heat remaining ¼ cup oil in now-empty pot over medium heat until shimmering. Add pasta and cook, stirring often, until just beginning to brown, about 5 minutes. Add wine and cook, stirring constantly, until absorbed, about 2 minutes.

5. When wine is fully absorbed, add warm broth and bring to boil. Cook, stirring frequently, until most of liquid is absorbed and pasta is al dente, 8 to 10 minutes. Off heat, stir in Parmesan, lemon juice, vegetables, and half of herb mixture. Season with salt and pepper to taste, and serve immediately, passing extra Parmesan and remaining herb mixture separately.

FOR BETTER FLAVOR, COOK PASTA LIKE RISOTTO

To deepen the overall flavor of our Spring Vegetable Pasta and add body to the sauce, we cook the pasta like rice.

1. TOAST PASTA Sautéing the raw pasta in oil gives it a nutty, rich flavor.

2. ADD WINE AND BROTH A cup of white wine gets absorbed by the pasta, contributing brightness; boiling the pasta in enhanced vegetable broth boosts flavor.

3. COOK UNTIL CREAMY As the pasta cooks, it gets coated in the creamy, starch-thickened broth—no cream needed.

Sicilian pasta alla Norma is a lively combination of tender eggplant and robust tomato sauce, seasoned with herbs, mixed with al dente pasta, and finished with shreds of salty, milky ricotta salata (salted and pressed ricotta cheese made from sheep’s milk). The textures and flavors have much more nuance than the typical pasta with tomato sauce, and the eggplant lends pasta alla Norma a heartiness—a virtual meatiness—that makes it superbly satisfying.

Although not widely known outside Italy, this pasta is a classic in Sicily, where it was named for a 19th-century opera in which a druid priestess, Norma, perishes alongside her Roman lover. As the story goes, the opera was such a sensation, it inspired a Sicilian chef to create this dish in tribute to the opera and its composer, Vincenzo Bellini, a native son.

Microwaving the eggplant streamlines prep and allows it to caramelize, boosting flavor.

But even a classic faces pitfalls. After cooking a slew of different pasta alla Norma versions, I began to know them all too well. The eggplant is a big production to prepare, usually requiring salting before frying, and often ends up soggy and slick with oil. The tomatoes tend to coagulate into a heavy, overwhelming sauce, or they’re so few they don’t form an adequate foundation. The flavors in the dish can easily drown out the subtle essence of the eggplant.

Determined to do better, I set out to develop a bold, complex pasta. I wanted a weeknight meal with rich tomato and eggplant flavors and smooth, silky texture—without an excessive amount of work.

A STEAMY SETUP

Most pasta alla Norma recipes advise salting cubed eggplant to draw out its excess moisture, usually for about an hour. Since I was keen to streamline at every opportunity, this was the place to start. To determine if I could skip or at least shorten salting, I prepared batches with eggplant I had salted for an hour, a half hour, 15 minutes, and not at all. After tasting these different versions side by side, I had to conclude that salting for an hour was best: It drew out the most moisture, which helped the eggplant brown better and cook faster.

Next, I considered how to cook the eggplant. One of the first recipes I tried called for frying two eggplants, cut into strips, in 3 inches of oil. The eggplant soaked up about half its weight in oil, turning silky and very rich. But it made for a heavy, greasy sauce—not to mention the fact that frying splattered my stovetop with oil and required almost 40 minutes of watchful cooking in batches. Frying, I decided, was out. I briefly considered roasting the eggplant, but this method also seemed slow for a weeknight meal. The remaining option was sautéing in a lesser amount of oil. Unfortunately, when I tried this approach, the eggplant was almost always underdone and still required cooking in batches. Hoping to cook the eggplant more deeply, I peeled the skin before cubing and sautéing—but the difference was barely discernible, so the peel stayed on.

Looking for new ideas, I recalled an ingenious method for removing moisture from eggplant developed by a test kitchen colleague working on a recipe for caponata, another Sicilian eggplant dish. Instead of salting the eggplant and then leaving it to drain on paper towels on the countertop, he zapped the salted cubes in the microwave for 10 minutes. The salt draws out moisture that microwaving turns into steam, all the while causing the eggplant to collapse and compress its air pockets. The collapsed air pockets, in turn, soak up less oil in the pan. Put into practice for pasta alla Norma, this method was a resounding success. It was much faster than traditional salting and achieved even better results; the eggplant pieces came out of the microwave quite dry (a good start for browning). Furthermore, microwaving shrank the cubes to a size that could handily be cooked in just one batch in a 12-inch skillet.

Now I could try sautéing again, and this time it worked perfectly, browning the egg- plant and adding rich flavor. I cooked a few batches, browning them to various degrees. Not surprisingly, the deeply caramelized eggplant tasted the roundest and fullest, with toasty notes accenting the vegetable’s elusive sweetness. It was so flavorful that there really was nothing to be missed about frying.

Finally, I tried different types of eggplant: portly globe eggplants; smaller, more svelte Italian eggplants; and slender, lavender-colored Chinese eggplants. All worked, but in the end, I preferred globe eggplants, which have a tender yet resilient texture and far fewer seeds than other varieties, including Italian eggplants. Cut into cubes, they retained their shape even after sautéing.

A SAVORY SURPRISE

The base for pasta alla Norma is a simple tomato sauce to which the eggplant is added. I was sure that in-season tomatoes would give the dish fresh flavor, but after a couple rounds of testing, I concluded that the trouble of peeling and then salting them (to avoid a stringy, watery sauce) was more effort than I wanted for a midweek meal. It would be far better to develop a simple year-round option.

Diced canned tomatoes yielded a bright-tasting sauce with a coarse texture, but since the eggplant was already cut into cubes, the sauce was too chunky. My tasters preferred a sauce made with canned crushed tomatoes—a full 28-ounce can—for its thick consistency, which added cohesion.

To season the sauce, I started with a modest amount of garlic—two cloves, minced—but ended up using twice that amount to add some pungency. A small measure of red pepper flakes added a suggestion of heat, a generous dose of chopped basil brought fresh flavor, and a tablespoon of extra-virgin olive oil stirred in at the end with the basil gave the sauce rich, round, fruity notes.

The sauce tasted fine tossed with the pasta, especially when sprinkled with a generous dose of ricotta salata cheese, yet something was missing. It seemed to lack backbone. I was considering a break with tradition by adding pancetta or prosciutto when a test kitchen colleague offered a novel suggestion: anchovies. Of course! Cooked in oil with garlic and red pepper flakes, one minced fillet was good, but two were even better, giving the sauce a deep, savory flavor without any trace of fishiness.

A SIMMERING FINALE

So far, I had well-browned eggplant and a flavorful tomato sauce. To determine how best to bring these elements together, I made a couple more batches. For the first, I browned the eggplant, set it aside, made the sauce in the same skillet, and then added the eggplant to the sauce and simmered them together only long enough to heat through, no more than five minutes. For the second, I built the tomato sauce right on top of the browned eggplant so that they simmered together for about 10 minutes. The latter wound up a bit mushy and somewhat muddled, with some of the eggplant soggy and tattered. But the former had crisp, clear qualities—the eggplant’s caramelization could still be tasted, and its tender texture had integrity. Even with only a few minutes of simmering, the eggplant had a tendency to soak up tomato juices, causing the sauce to become rather thick, so the final adjustment was adding a little reserved pasta cooking water when tossing the sauce with the pasta. Now all the components—the pasta, the tomato sauce, and the eggplant—were perfectly in tune. No longer a tragedy, my pasta alla Norma was on the table in well under an hour, without theatrics but with bold and balanced flavors.

SERVES 4

Ricotta salata is traditional, but French feta, Pecorino Romano, and Cotija (a firm, crumbly Mexican cheese) are acceptable substitutes. We prefer kosher salt because it clings best to the eggplant. If using table salt, reduce salt amounts by half. For a spicier sauce, use the larger amount of red pepper flakes.

1½ pounds eggplant, cut into ½-inch pieces

Kosher salt

¼ cup extra-virgin olive oil

4 garlic cloves, minced

2 anchovy fillets, rinsed, patted dry, and minced

¼–½ teaspoon red pepper flakes

1 (28-ounce) can crushed tomatoes

6 tablespoons chopped fresh basil

1 pound ziti, rigatoni, or penne

3 ounces ricotta salata, shredded (1½ cups)

1. Toss eggplant with 1 teaspoon salt in large bowl. Line large plate with double layer of coffee filters and lightly spray with vegetable oil spray. Spread eggplant in even layer over coffee filters; wipe out bowl with paper towels and set aside. Microwave eggplant until dry to touch and slightly shriveled, about 10 minutes, tossing halfway through cooking. Let cool slightly.

2. Transfer eggplant to now-empty bowl, drizzle with 1 tablespoon oil, and toss gently to coat; discard coffee filters and reserve plate. Heat 1 tablespoon oil in 12-inch nonstick skillet over medium-high heat until shimmering. Add eggplant and cook, stirring every 1½ to 2 minutes (more frequent stirring may cause eggplant pieces to break apart), until well browned and fully tender, about 10 minutes. Transfer eggplant to now-empty plate and set aside. Let skillet cool slightly, about 3 minutes.

3. Heat 1 tablespoon oil, garlic, anchovies, and pepper flakes in now-empty skillet over medium heat. Cook, stirring often, until garlic turns golden but not brown, about 3 minutes. Stir in tomatoes, bring to simmer, and cook, stirring occasionally, until slightly thickened, 8 to 10 minutes. Add eggplant and continue to cook, stirring occasionally, until eggplant is heated through and flavors meld, 3 to 5 minutes longer. Stir in basil and remaining 1 tablespoon oil and season with salt to taste.

4. Meanwhile, bring 4 quarts water to boil in large pot. Add pasta and 2 tablespoons salt and cook, stirring often, until al dente. Reserve ½ cup cooking water, then drain pasta and return it to pot. Add sauce to pasta and toss to combine. Adjust consistency with reserved cooking water as needed. Serve immediately with ricotta salata.

RICOTTA SALATA’S UNDERSTUDIES

Ricotta salata, a firm, tangy Italian sheep’s-milk cheese that bears little resemblance to the moist ricotta sold in tubs, is an essential component of traditional pasta alla Norma. If you can’t find it, consider these options instead.

FRENCH FETA Milder but tangy, this is a close cousin to ricotta salata in flavor and texture.

PECORINO ROMANO Hard and dry, with a slightly more assertive aroma and flavor than ricotta salata.

COTIJA Made with cow’s milk, this Mexican cheese has a firm yet crumbly texture, but is less complex than ricotta salata.

Italians have a knack for transforming humble ingredients into remarkable meals, and the rustic trio of pasta, hearty greens, and beans is no exception: When carefully prepared, the combination is sublime. But making something out of almost nothing takes time. In this case, dried cannellini beans are gently simmered until tender and greens are cleaned, cooked, and seasoned. Tossed with al dente pasta and a sprinkling of Parmesan, the result is rich and satisfying. If I could find a few shortcuts yet retain the complex flavors of the original, this dinner could become a regular in my midweek repertoire.

A BITTER BEGINNING

The hearty greens that Italians usually mix with pasta and beans include turnip, dandelion, chicory, mustard, broccoli rabe, collards, and kale. To reduce bitterness, many recipes call for blanching, shocking (dunking in ice water), squeezing dry, chopping, and sautéing them. The resulting greens are robust but not overpowering, but the whole process demands time and multiple pieces of kitchen equipment.

We streamline this classic Italian dish by using a hybrid sauté/braise technique to wilt the greens.

Two of the choices, kale and collard greens, were standouts: Tasters noted their appealing qualities but made not one mention of bitterness, giving me hope for a straightforward cooking method. Sure enough, a simple sauté tasted great, but the quantity of raw greens necessary meant that I would have to cook them in three or four batches. The solution was a sauté/braise combination. I quickly wilted half of the greens in a hot pan with olive oil, aromatic onions and garlic, and spicy red pepper flakes and then squeezed in the remainder of the raw greens. I poured in broth to serve as the braising liquid, and, 15 minutes later, tender, flavorful greens were mine.

FINISHING TOUCHES

As for the pasta, I’d run across a few references to whole-wheat spaghetti and decided to try it—despite some skepticism among a few health-food-fearing colleagues. I prepared a batch, served it up, and braced myself for the reactions. Surprise: Tasters unanimously preferred the nutty flavor of whole-wheat pasta to traditional semolina pasta for this dish. In fact, the more potent dimension of flavor provided by the whole-wheat pasta was the missing link, adding complexity that brought the beans and greens into a pleasing harmony.

To finish, I worked in some heavy-hitting ingredients to compensate for the flavor deficiency of the canned beans (the shortcut alternative to cooking them myself): tomatoes, olives, and Parmesan cheese. Still more garlic, in the form of chips, contributed welcome crunch.

One last note: I knew from experience that draining the pasta and finishing it in the sauce helps to integrate the components of a dish, and this one was no exception. Just a few minutes of simmering went a long way toward joining the gutsy flavors. Now I can have classic Italian comfort food, even when time isn’t on my side.

Whole-Wheat Pasta with Greens and Beans

SERVES 4 TO 6

3 tablespoons olive oil, plus extra for drizzling

8 garlic cloves (5 sliced thin lengthwise, 3 minced)

Salt and pepper

1 onion, chopped fine

½ teaspoon red pepper flakes

1½ pounds kale or collard greens, stemmed and cut into 1-inch pieces

1 (14.5-ounce) can diced tomatoes, drained

¾ cup chicken or vegetable broth

1 (15-ounce) can cannellini beans, rinsed

¾ cup pitted kalamata olives, chopped coarse

1 pound whole-wheat spaghetti

2 ounces Parmesan cheese, grated fine (1 cup), plus extra for serving

1. Heat oil and sliced garlic in 12-inch straight-sided sauté pan over medium heat. Cook, stirring often, until garlic turns golden but not brown, about 3 minutes. Using slotted spoon, transfer garlic to paper towel–lined plate and sprinkle garlic lightly with salt.

2. Add onion to oil left in pan and cook over medium heat until softened and lightly browned, 5 to 7 minutes. Stir in minced garlic and pepper flakes and cook until fragrant, about 30 seconds. Add half of kale and cook, tossing occasionally, until starting to wilt, about 2 minutes. Add tomatoes, broth, ¾ teaspoon salt, and remaining kale and bring to simmer. Reduce heat to medium, cover (pan will be very full), and cook, tossing occasionally, until kale is tender, about 15 minutes (mixture will be somewhat soupy). Stir in beans and olives.

3. Meanwhile, bring 4 quarts water to boil in large pot. Add pasta and 1 tablespoon salt and cook, stirring often, until just shy of al dente. Reserve ½ cup cooking water, then drain pasta and return it to pot. Add kale mixture to pasta and cook over medium heat, tossing to combine, until pasta absorbs most of liquid, about 2 minutes.

4. Off heat, stir in Parmesan. Adjust consistency with reserved cooking water as needed. Season with salt and pepper to taste, and serve immediately, drizzling individual portions with extra oil and passing garlic chips and extra Parmesan separately.

In theory, garlic shrimp pasta has all the makings of an ideal weeknight meal. Toss a few quick-cooking ingredients—shrimp, garlic, oil, wine—with boiled dried pasta, and only the salad’s left holding up dinner.

But there are challenges. Delicate shrimp overcooks in a matter of seconds. Volatile garlic can easily become overbearing or bitter (or simply disappear). Add to that the feat of getting a brothy sauce to coat the pasta, and this simple recipe turns into a precarious balancing act. But I still wanted it all: al dente pasta and moist shrimp bound by a supple sauce infused with a deep garlic flavor.

Before facing the garlic problem, I tackled the shrimp. I ruled out fast-cooking medium shrimp, as well as expensive extra-large and jumbo, landing on midpriced-but-meaty large shrimp (26 to 30 per pound). Searing them quickly over high heat yielded an overcooked texture. Poaching kept the shrimp moist but didn’t contribute much flavor. I tentatively settled on sautéing them gently in garlic and oil while building the sauce.

To build layers of garlic flavor, we use it in the marinade for the shrimp, to infuse the cooking oil, and as an element of the dish.

Starting with a basic working recipe, I sautéed the shrimp with three cloves of minced garlic in a modest amount of olive oil. Removing the shrimp, I added a pinch of red pepper flakes and a cup of white wine, reduced the sauce, then tossed it with the shrimp and linguine. The results were just OK: weak garlic, moist but lackluster shrimp, and a thinnish sauce.

Upping the garlic to six cloves gave me indisputably garlicky pasta. But now I had a new problem: All that garlic cooked unevenly. Sautéed too little, and the garlic tastes raw and harsh; too long, and random burnt granules impart a bitter taste. Turning the heat to the lowest setting and simmering the garlic longer yielded a sweet, nutty taste, but my tasters missed the brasher notes.

Borrowing tricks from our Spanish-Style Garlic Shrimp recipe, I split the difference. First, I slowly simmered the oil with smashed garlic cloves (more effective in this task than minced) over low heat, discarded the toasted cloves, and built the sauce using the infused oil. Just before adding the wine, I quickly sautéed a smaller amount of minced garlic (just long enough to bloom the flavor). Marinating the shrimp for 20 minutes with additional minced garlic gave the dish just the balanced, deeply layered garlic flavor I wanted.

Next, I tinkered with the sauce. Bottled clam broth added after the vermouth contributed complexity, bolstering the shrimp flavor. To get the sauce to cling to the pasta, I stirred a little flour into the oil as a thickener and added some cold butter to finish.

I was close, but tasters remarked that the shrimp stayed hidden in the tangle of linguine, and there simply weren’t enough bites. Swapping out the linguine for a chunky tubular pasta made it easy to find the shrimp, and cutting each shrimp into thirds before cooking ensured that nearly every bite boasted a tasty morsel.

SERVES 4 TO 6

Marinate the shrimp while you prepare the remaining ingredients. Use the smaller amount of red pepper flakes for a milder sauce.

1 pound large shrimp (26 to 30 per pound), peeled, deveined, and each shrimp cut into 3 pieces

3 tablespoons olive oil

9 garlic cloves, peeled (5 cloves minced and 4 cloves smashed)

Salt and pepper

1 pound penne, ziti, or other short, tubular pasta

¼–½ teaspoon red pepper flakes