RICE, GRAINS, AND BEANS

Perfecting Rice and Pasta Pilaf

A few years ago when eating in a Persian restaurant, I became instantly enamored of its rice pilaf. Fragrant and fluffy, perfectly steamed, tender but still retaining an al dente quality, this was the type of rice I loved. Still better, this rice had gained flavor and texture from the other, more intensely flavored ingredients that had been added to it. Excited, I decided to find the best way to make rice pilaf that was this good in my own kitchen.

My first step was to define rice pilaf. According to most culinary sources, it is simply long-grain rice that has been cooked in hot oil or butter before being simmered in hot liquid, typically either water or stock. In Middle Eastern cuisines, however, the term pilaf also refers to a more substantial dish in which the rice is cooked in this manner and then flavored with other ingredients—spices, nuts, dried fruits, and/or chicken or other meat. To avoid confusion, I decided to call the simple master recipe for my dish “pilaf-style” rice, designating the flavored versions as rice pilaf.

I also discovered in my research that there are many different ways to cook rice pilaf. Most of these methods were traditions from the Middle East, from which this dish hails. Most recipes stipulated that the rice had to be soaked or at least rinsed prior to cooking in order to produce a finished rice with very separate, very fluffy grains, the characteristic that virtually defines the dish. With my recipes in hand, I started testing.

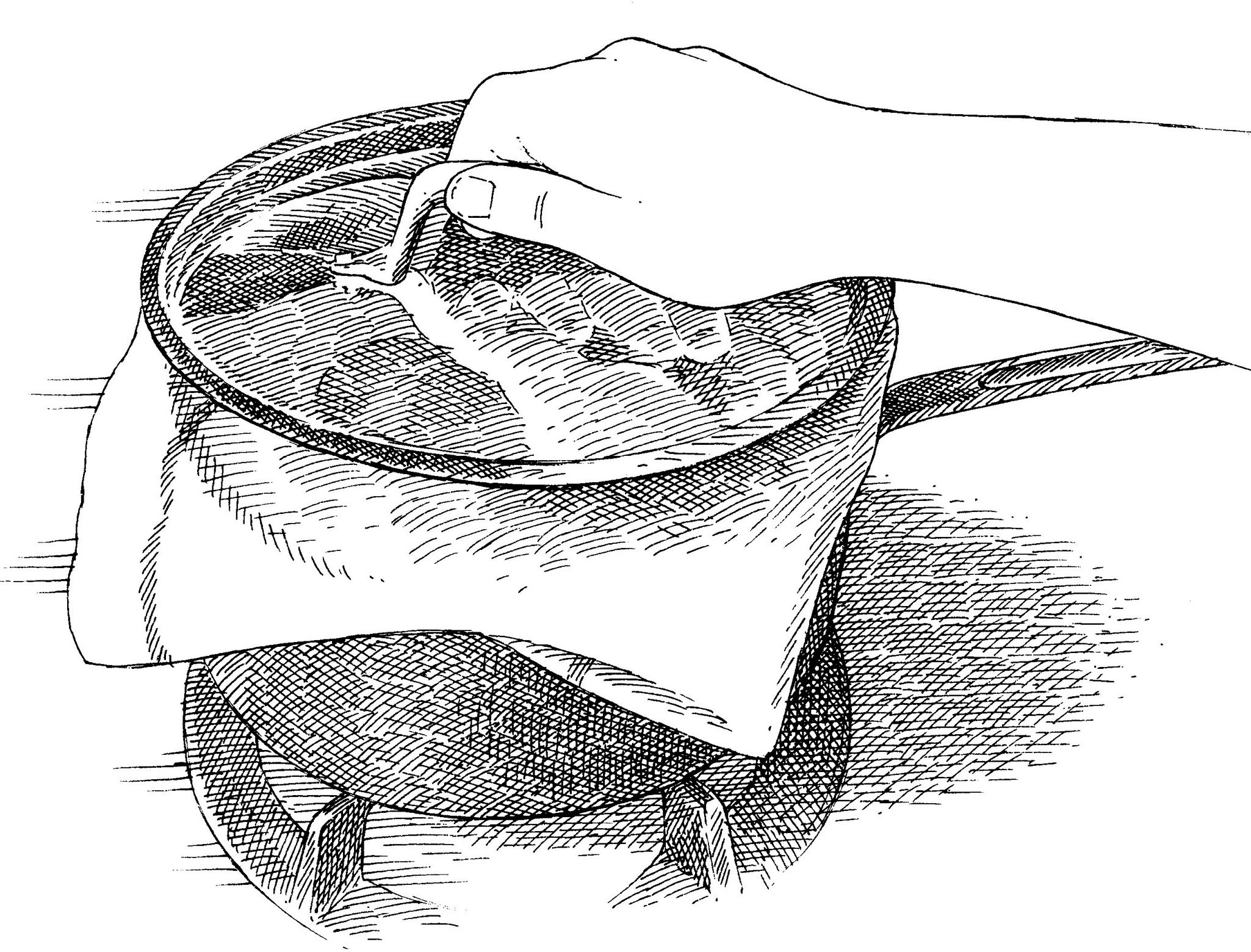

Rinsing the rice before cooking and then letting it steam covered with a towel after simmering produces fluffy, separate grains.

Right Rice, Right Ratio

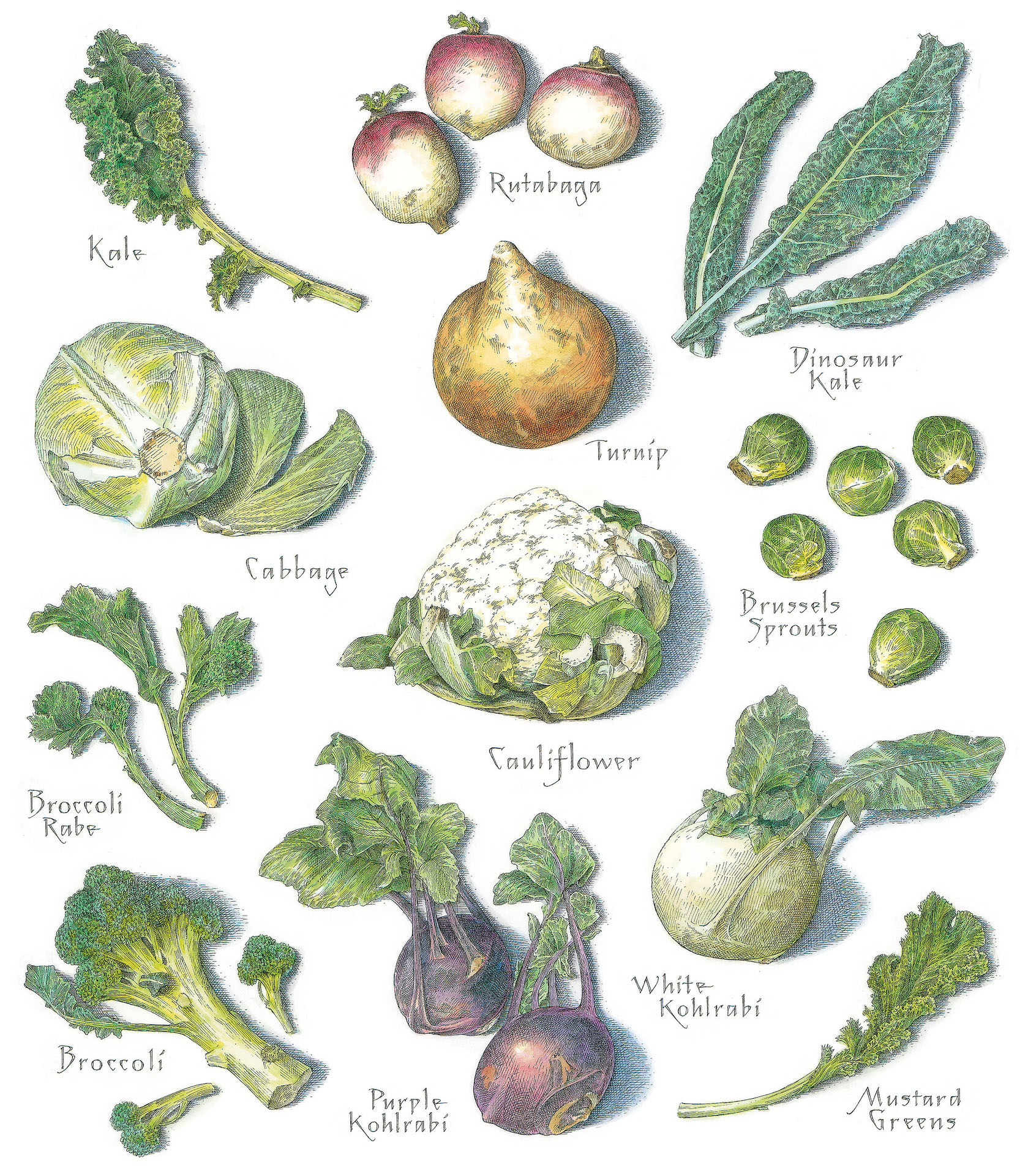

The logical first step in this process was to isolate the best type of rice for pilaf. I limited my testing to long-grain rice, since medium and short-grain rice inherently produce a rather sticky, starchy product and I was looking for fluffy, separate grains. I came upon a number of different choices: plain long-grain white rice, converted rice, instant rice, jasmine, basmati, and Texmati (basmati rice grown domestically in Texas). I cooked them each according to a standard, stripped-down recipe for rice pilaf, altering the ratio of liquid to rice according to each variety when necessary.

Each type of rice was slightly different in flavor, texture, and appearance. Worst of the lot was the instant rice, which was textureless and mushy and had very little rice flavor. The converted rice had a very strong, off-putting flavor, while the jasmine rice, though delicious, was a little too sticky for pilaf. Plain long-grain white rice worked well, but basmati rice was even better: each grain was separate and long and fluffy, and the rice had a fresh, delicate fragrance. Though the Texmati produced similar results, it cost three times as much as the basmati per pound, making the basmati rice the logical choice. That said, I would add that you can use plain long-grain rice if basmati is not available.

In culinary school I was taught that the proper rice to liquid ratio for long-grain white rice is 1 to 2, but many cooks use less water, so I decided to figure it out for myself. After testing every possibility, from 1:1 to 1:2, I found that I got the best rice using 1⅔ cups of water for every cup of rice. To make this easier to remember, as well as easier to measure, I increased the rice by half to 1½ cups and the liquid to 2½ cups.

GIVE IT A RINSE

With my rice to water ratio set, I was ready to test the traditional methods for making pilaf, which called for rinsing, soaking, or parboiling the rice before cooking it in fat and simmering it to tenderness. Each recipe declared one of these preparatory steps to be essential in producing rice with distinct, separate grains that were light and fluffy.

I began by parboiling the rice for 3 minutes in a large quantity of water, as you would pasta, then draining it and proceeding to sauté and cook it. This resulted in bloated, waterlogged grains of rice.

Rinsing the rice, on the other hand, made a substantial difference, particularly with basmati rice. I simply covered 1½ cups of rice with water, gently moved the grains around using my fingers, and drained the water from the rice. I repeated this process about four or five times until the rinsing water was clear enough for me to see the grains distinctly. I then drained the rice and cooked it in oil and liquid (decreased to 2¼ cups to compensate for the water that had been absorbed by or adhered to the grains during rinsing). The resulting rice was less hard and more tender, and it had a slightly shinier, smoother appearance.

I also tested soaking the rice before cooking it. I rinsed three batches of basmati rice and soaked them for 5 minutes, 1 hour, and overnight, respectively. The batch that soaked for 5 minutes was no better than the one that had only been rinsed. Soaking the rice for an hour proved to be a still greater waste of time, since it wasn’t perceptibly different from the rinsed-only version. While the rice that was soaked overnight was better than the rinsed-only rice, the difference was subtle, and the extra step required so much forethought that I opted for the simpler step of merely rinsing.

Thus far, I had allowed the rice to steam an additional 10 minutes after being removed from the heat to ensure that the moisture was distributed throughout. I wondered if a longer or shorter steaming time would make a big difference in the resulting pilaf. I made a few batches of pilaf, allowing the rice to steam for 5 minutes, 10 minutes, and 15 minutes. The rice that steamed for 5 minutes was heavy and wet. The batch that steamed for 15 minutes was the lightest and least watery. I also decided to try placing a clean dish towel between the pan and the lid right after I took the rice off the stove. What I found was that this produced the best results of all, while reducing the steaming time to only 10 minutes. The towel prevents condensation and absorbs the excess water in the pan during steaming, producing drier, fluffier rice.

FAT AND FLAVORINGS

In culinary school, we were taught to use just enough fat to cover the grains of rice with oil, about 1 tablespoon per cup of rice. I was therefore surprised to see that many Middle Eastern recipes called for as much as ¼ cup of butter per cup of rice. I decided to do a test of my own to determine the optimal amount of fat. Using butter (since I like the extra flavor and richness that it lends to the rice), I tried from 1 to 4 tablespoons per 1½ cups of rice. Three tablespoons was best: The rice was buttery and rich without being overwhelmingly so, and each grain was more distinct than when cooked with less fat.

I also wondered if sautéing the rice for different amounts of time would make a difference, so I sautéed the rice over medium heat for 1 minute, 3 minutes, and 5 minutes. The pan of rice that was sautéed for 5 minutes was much less tender than the other two. It also had picked up a strong nutty flavor. When sautéed for 1 minute, the rice simply tasted steamed. The batch sautéed for 3 minutes was the best, with a light nutty flavor and tender texture.

At the end comes the fun part—adding the flavorings, seasonings, and other ingredients that give the pilaf its distinctive character. You need to pay attention when you add these ingredients, though, since different types work best when added at different stages. Dried spices, minced ginger, and garlic, for example, are best sautéed briefly in the fat before the raw rice is added to the pan, while fresh herbs and toasted nuts should be added to the pilaf just before serving to maximize freshness, texture (in the case of nuts), and flavor. Dried fruits such as currants can be added just before steaming the rice, which gives them enough time to heat and become plump.

SERVES 4

You will need a saucepan with a tight-fitting lid for this recipe. Olive oil can be substituted for the butter. If using a nonstick pan, feel free to use less butter—a tablespoon or two will be plenty. If you prefer, the onion can be omitted. Or use a minced shallot or two instead.

1½ cups basmati or other long-grain white rice

1½ teaspoons salt

Pinch pepper

3 tablespoons unsalted butter

1 small onion, chopped fine

1. Place rice in bowl and cover with water by 2 inches; using your hands, gently swish grains to release excess starch. Carefully pour off water, leaving rice in bowl. Repeat 4 to 5 times, until water runs almost clear. Drain rice in fine-mesh strainer.

2. Bring 2¼ cups water to boil, covered, in small saucepan over medium-high heat. Add salt and pepper and cover to keep hot. Meanwhile, melt butter in large saucepan over medium heat. Add onion and cook until softened but not browned, about 4 minutes. Add rice and stir to coat grains with butter; cook until edges of grains begin to turn translucent, about 3 minutes. Stir hot seasoned water into rice. Return to boil, then reduce heat to low, cover, and cook until all liquid is absorbed, 16 to 18 minutes. Off heat, remove lid, fold dish towel in half, and place over saucepan; replace lid. Let stand for 10 minutes. Fluff rice with fork and serve.

variations

Rice Pilaf with Currants and Pine Nuts

Add 2 minced garlic cloves, ½ teaspoon ground turmeric, and ¼ teaspoon ground cinnamon to softened onion and cook until fragrant, about 30 seconds. When rice is off heat, before covering saucepan with towel, sprinkle ¼ cup currants over top of rice (do not mix in). When fluffing rice with fork, toss in ¼ cup toasted pine nuts.

Indian-Spiced Rice Pilaf with Dates and Parsley

Add 2 minced garlic cloves, 1 tablespoon grated fresh ginger, ¼ teaspoon ground cinnamon, and ¼ teaspoon ground cardamom to softened onion and cook until fragrant, about 30 seconds. When fluffing rice with fork, toss in ½ cup chopped dates and 3 tablespoons minced fresh parsley.

Saffron Rice Pilaf with Apricots and Almonds

Add ½ teaspoon saffron with onion in step 2. When rice is off heat, before covering saucepan with towel, sprinkle ½ cup finely chopped dried apricots over top of rice (do not mix in). When fluffing rice with fork, toss in ½ cup toasted slivered almonds.

DOUBLING RICE PILAF? DON’T DOUBLE THE WATER

If you try to simply double the recipe for our Simple Pilaf-Style Rice, you will end up with a layer of mushy rice on the bottom of the pot. The reason: Rice-to-water ratios can’t be scaled up proportionally. Rice absorbs water in a 1:1 ratio, no matter the volume. So in the master recipe, which calls for 1½ cups of rice and 2¼ cups of water, the rice absorbs 1½ cups of water. The remaining ¾ cup of water evaporates. But here’s the catch: The amount of water that evaporates doesn’t double when the amount of rice is doubled. When you cook a double batch of rice using the same conditions—the same large pot and lid and on the same stove burner over low heat—as you’d use for a single batch, the same quantity of water will evaporate: ¾ cup. So simply doubling the recipe leads to mushy rice because there is an excess of water in the pot. The bottom line: To double our rice pilaf recipe, use 3 cups of rice and only 3¾ cups of water.

For some, rice and pasta pilaf conjures up images of streetcars ascending steep hills to the tune of that familiar TV jingle. But for me, it’s not the “San Francisco Treat” that comes to mind but Sunday dinners at my Armenian grandmother’s. As it turns out, the two memories are not so disparate: Rice-A-Roni owes its existence to a fateful meeting in 1940s San Francisco. Lois DeDomenico, daughter of Italian immigrants, learned to make rice and pasta pilaf from her Armenian landlady, Pailadzo Captanian. The dish became a staple of the DeDomenico household and would eventually inspire Lois’s husband, Tom, whose family owned a pasta factory, to develop a commercial version. They named the product after its two main ingredients—rice and macaroni (pasta)—and the rest is history.

The original dish is a simple affair: A fistful of pasta (usually vermicelli) is broken into short pieces and toasted in butter. Finely chopped onion and/or minced garlic is added next, followed by basmati rice. Once the grains are coated in fat, chicken broth is poured in. After simmering, the pilaf is often allowed to sit covered with a dish towel under the lid to absorb steam—a trick that yields superfluffy results. In a well-executed version, the rice and pasta are tender and separate, boasting rich depth from the butter and nuttiness from the toasted noodles.

Soaking the rice ensures that the grains finish cooking at the same time as the pasta.

Sadly, I never learned my grandmother’s recipe, and the cookbook versions I tried fell short, with either mushy, overcooked vermicelli or sticky, overly firm rice. Using both garlic and onion (shredded on a box grater so that it would add flavor but not a distracting texture), I patched together a recipe and mostly resolved the under- or overcooked rice problem simply by nailing the appropriate amount of liquid: 2½ cups to 1½ cups rice and ½ cup pasta.

But even with this ratio, my pilaf was plagued by a thin layer of somewhat raw, crunchy rice just beneath the pasta, which always floated to the top of the pot during simmering. What’s more, the pasta was too soft and mushy. The quicker-cooking vermicelli seemed to absorb broth more rapidly than the rice, thereby denying the rice that surrounded it sufficient liquid to cook through. My theory was confirmed when I reduced the water by ¼ cup and deliberately left the pasta out of a batch: The rice cooked up tender as could be.

Adding more broth would make the dish soggy. Stirring during cooking helped, but plenty of grains still emerged underdone.

I needed every last grain of rice to absorb the broth at the same rate as the pasta did. I considered removing the toasted vermicelli from the pot, starting the rice, and then adding back the pasta when the rice was nearly tender, but that seemed unwieldy. Then I came up with a more viable solution: soaking. Starches absorb water at relatively low temperatures, so I guessed that I could hydrate, or sort of parcook, the rice in hot tap water ahead of time. Sure enough, when I saturated the grains in hot water for 15 minutes before continuing with the recipe, the finished rice and pasta both had an ideal tender texture.

With my foolproof approach at hand, I developed a few flavorful variations. This side dish brought me right back to my grandmother’s kitchen.

Rice and Pasta Pilaf

SERVES 4 TO 6

Use long, straight vermicelli or vermicelli nests. Grate the onion on the large holes of a box grater.

1½ cups basmati or other long-grain white rice

3 tablespoons unsalted butter

2 ounces vermicelli, broken into 1-inch pieces

1 onion, grated

1 garlic clove, minced

2½ cups chicken broth

1¼ teaspoons salt

3 tablespoons minced fresh parsley

1. Place rice in medium bowl and cover with hot tap water by 2 inches; let stand for 15 minutes.

2. Using your hands, gently swish grains to release excess starch. Carefully pour off water, leaving rice in bowl. Add cold tap water to rice and pour off water. Repeat adding and pouring off cold water 4 to 5 times, until water runs almost clear. Drain rice in fine-mesh strainer.

3. Melt butter in saucepan over medium heat. Add pasta and cook, stirring occasionally, until browned, about 3 minutes. Add onion and garlic and cook, stirring occasionally, until onion is softened but not browned, about 4 minutes. Add rice and cook, stirring occasionally, until edges of rice begin to turn translucent, about 3 minutes. Add broth and salt and bring to boil. Reduce heat to low, cover, and cook until all liquid is absorbed, about 10 minutes. Off heat, remove lid, fold dish towel in half, and place over saucepan; replace lid. Let stand for 10 minutes. Fluff rice with fork, stir in parsley, and serve.

variations

Stir ¼ cup plain whole-milk yogurt, ¼ cup minced fresh dill, and ¼ cup minced fresh chives into pilaf with parsley.

Rice and Pasta Pilaf with Crispy Shallots and Pistachios

Omit garlic and onion. Place 3 thinly sliced shallots and ½ cup olive oil in large saucepan. Cook over medium heat, stirring constantly, until shallots are golden and crispy, 6 to 10 minutes. Using slotted spoon, transfer shallots to paper towel–lined plate. Leave oil in pan; omit butter and toast pasta in shallot oil. Add 2 teaspoons ground coriander and half of shallots to pan with broth. Omit parsley and stir ½ cup chopped fresh mint; ½ cup shelled pistachios, toasted and chopped coarse; and 1 tablespoon lemon juice into fluffed rice. Sprinkle remaining shallots over rice before serving.

Rice and Pasta Pilaf with Golden Raisins and Almonds

Place ½ cup golden raisins in bowl and cover with boiling water by 1 inch. Let stand until plump, about 5 minutes. Drain and set aside. Add 2 bay leaves and 1 teaspoon ground cardamom to pot with chicken broth. Discard bay leaves and stir in raisins and ½ cup slivered almonds, toasted and chopped coarse, with parsley.

Rice and Pasta Pilaf with Pomegranate and Walnuts

Omit onion and garlic. Add 2 tablespoons grated fresh ginger to pan with rice. Add ½ teaspoon ground cumin with chicken broth. Omit parsley and stir ½ cup walnuts, toasted and chopped coarse; ½ cup pomegranate seeds; ½ cup chopped fresh cilantro; and 1 tablespoon lemon juice into fluffed rice.

NEATLY BREAKING LONG STRANDS OF PASTA

Our Rice and Pasta Pilaf calls for vermicelli that has been broken into 1-inch pieces. Here’s a way to break the strand pasta without causing short pieces to fly every which way in the kitchen.

1. Place pasta in dish towel and fold sides of towel over pasta with 3- to 4-inch overlap at both ends.

2. Holding ends of towel firmly, center rolled bundle on edge of counter and push down to break pasta. Repeat until pasta is broken into 1-inch pieces.

Basmati rice is the traditional choice for rice and pasta pilaf, but supermarket shelves teem with a multitude of boxes, bags, and burlap sacks labeled “basmati.” True basmati can only come from India or Pakistan, and must meet standards for grain dimension, amylose content, and grain elongation during cooking, as well as for aroma. Unlike American basmati, authentic basmati is aged for a minimum of a year (and often much longer) before packaging. Aging dehydrates the rice, so the cooked grains expand greatly in length—more so than any other long-grain rice.

MAKING RICE AND PASTA PILAF

To make sure that both the rice and the pasta in our pilaf are done at the same time, we first soak the rice briefly in hot water and then rinse it of excess starch. To cook the pilaf, we start by toasting the pasta and rice, then add liquid. Covering with a dish towel at the end absorbs moisture.

1. Toast pasta in melted butter until browned, then add onion and garlic. Add rice and cook, stirring occasionally, until edges of rice begin to turn translucent.

2. Add broth, bring to boil, then reduce heat to low, cover, and cook until liquid is absorbed, about 10 minutes.

3. Off heat, place folded dish towel under lid and let stand for 10 minutes. Fluff with fork and stir in parsley.

Most cooks I know shun brown rice, classifying it as wholesome yet unappealing sustenance for penniless vegetarians, practitioners of macrobiotics, and the like. But I’m not sure why. I find it ultimately satisfying, with a nutty, gutsy flavor and more textural personality—slightly sticky and just a bit chewy—than white rice. An ideal version should be easy to come by: Just throw rice and water in a pot and set the timer, right? Yet cooks who have attempted to prepare brown rice know it isn’t so simple. My habit, born of impatience, is to crank up the flame in an effort to hurry along the slow-cooking grains (brown rice takes roughly twice as long to cook as white), which inevitably leads to a burnt pot and crunchy rice. Adding plenty of water isn’t the remedy; excess liquid swells the rice into a gelatinous mass.

I pulled out an expensive, heavy-bottomed pot with a tight-fitting lid (many recipes caution against using inadequate cookware), fiddled with the traditional absorption method (cooking the rice with just enough water), and eventually landed on a workable recipe. Yet when I tested the recipe with less than ideal equipment—namely, a flimsy pan with an ill-fitting lid—I was back to burnt, undercooked rice. With the very best pot and a top-notch stove, it is possible to cook brown rice properly, but I wanted a surefire method that would work no matter the cook, no matter the equipment.

The even, encircling heat of the oven guarantees perfectly cooked brown rice every time.

I wondered if the microwave might work well in this instance, given that it cooks food indirectly, without a burner. Sadly, it delivered inconsistent results, with one batch turning brittle and another, prepared in a different microwave, too sticky. A rice cooker yielded faultless brown rice on the first try, but many Americans don’t own one.

I set out to construct a homemade cooker that would approximate the controlled, indirect heat of a rice cooker—and so began to consider the merits of cooking the rice in the oven. I’d have more precise temperature control, and I hoped that the oven’s encircling heat would eliminate the risk of scorching. My first try yielded extremely promising results: With the pan tightly covered with aluminum foil, the rice steamed to near perfection. Fine-tuning the amount of water, I settled on a ratio similar to that used for our white rice recipe: 2⅓ cups of water to 1½ cups of rice, falling well short of the 2:1 water-to-rice ratio advised by most rice producers and nearly every recipe I consulted. Perhaps that is why so much brown rice turns out sodden and overcooked.

My next task was to spruce up the recipe by bringing out the nutty flavor of the otherwise plain grains. Toasting the rice dry in the oven imparted a slight off-flavor. When I sautéed the rice in fat before baking, the grains frayed slightly; tasters preferred rice made by adding fat to the cooking water. A small amount (2 teaspoons) of either butter or oil adds mild flavor while keeping the rice fluffy.

To reduce what was a long baking time of 90 minutes at 350 degrees, I tried starting with boiling water instead of cold tap water and raising the oven to 375 degrees. These steps reduced the baking time to a reasonable 1 hour. (A hotter oven caused some of the fragile grains to explode.)

No more scorched or mushy brown rice for me, and no more worrying about finding just the right pan or adjusting the stovetop to produce just the right level of heat. Now I can serve good brown rice anytime, even to a meat lover.

Foolproof Oven-Baked Brown Rice

SERVES 4 TO 6

For an accurate measurement of boiling water, bring a full kettle of water to a boil and then measure out the desired amount. Medium or short-grain brown rice can be substituted for the long-grain rice.

2⅓ cups boiling water

1½ cups long-grain brown rice, rinsed

2 teaspoons unsalted butter or vegetable oil

Salt and pepper

1. Adjust oven rack to middle position and heat oven to 375 degrees. Combine boiling water, rice, butter, and ½ teaspoon salt in 8-inch square baking dish. Cover dish tightly with double layer of aluminum foil. Bake until liquid is absorbed and rice is tender, about 1 hour.

2. Remove dish from oven, uncover, and fluff rice with fork, scraping up any rice that has stuck to bottom. Cover dish with clean dish towel and let rice sit for 5 minutes. Season with salt and pepper to taste, and serve.

variation

Brown Rice with Parmesan, Lemon, and Herbs

Increase butter to 2 tablespoons and melt in 10-inch nonstick skillet over medium heat. Add 1 finely chopped small onion and cook until translucent, about 3 minutes; set aside. Substitute chicken broth for water and reduce salt to ⅛ teaspoon. Stir onion mixture into rice after adding broth. Cover and bake rice as directed. Remove foil; stir in ½ cup grated Parmesan cheese, ¼ cup minced fresh parsley, ¼ cup chopped fresh basil, 1 teaspoon grated lemon zest, ½ teaspoon lemon juice, and ⅛ teaspoon pepper before covering with dish towel.

Cooking a pot of long-grain rice is simple: Bring your ingredients to a simmer, cover the pot, and wait. Risotto is the exact opposite. Accepted wisdom dictates near-constant stirring to achieve the perfect texture: tender grains with a slight bite in the center, bound together in a light, creamy sauce. Here’s why stirring is critical: As the rice cooks, it releases starch granules, which absorb liquid and expand, thickening the broth to a rich consistency. Constantly stirring the pot jostles the rice grains against one another, agitating them and promoting the release of more starch granules from their exterior.

But frankly, most of us have neither the time nor the patience for all that stirring. That’s why, several years ago, we came up with an easier method. It starts out just like a traditional risotto recipe: Sweat the aromatics in a saucepan until softened, add 2 cups of Arborio rice, toast the grains in the hot fat for a few minutes, and pour in dry white wine, stirring until the liquid is just absorbed. Then, rather than adding the broth in traditional half-cup intervals, we add roughly half the liquid—3 cups of broth and water—all at once and simmer for a full 12 minutes, with only a few stirs during the process. Finally, for the last 9 minutes, we resume the traditional method, slowly adding the remaining broth while stirring constantly. The resulting risotto turns out every bit as creamy and al dente as those stirred nonstop for 30 minutes.

How does it work? Once it starts bubbling, all that liquid added at the beginning jostles the rice grains in much the same way as constant stirring, accelerating the release of starch. But now, I wanted to see if I could eliminate the final 9-minute stir and still deliver a perfect pot of risotto.

THE RIGHT RICE

A short-grained rice like Arborio is ideal for risotto because of its high starch content; other varieties simply aren’t starchy enough to properly thicken the sauce. What’s more, the starches at the very center don’t break down as readily as in other varieties, allowing the rice to maintain a firm, al dente center, even as the exterior becomes tender.

With all that going for it, the right rice paired with the right ratio of liquid should all but cook itself into a velvety dish without the aid of stirring. But one batch prepared according to our existing method, minus the final stirring step, left me with a pot of rice that was overcooked and mushy on the bottom, chalky and wet on top.

I had only so many variables to consider here, so I started with the liquid. What if I added 5 cups from the start? That way, I reasoned, the contents of the pot would be very fluid for the first 15 to 20 minutes of cooking, allowing the rice to bob around and cook more evenly with minimal stirring on my part. Only when the rice released enough starch and the sauce started to thicken up, impeding fluidity, would I need to resume stirring to ensure even cooking. I was pleasantly surprised by the outcome, though quite a few crunchy bits of uncooked rice from the cooler top of the pan had lingered. But I was getting somewhere.

DUTCH AND COVER

As I thought more about it, I realized that simply adding more liquid at the start wasn’t enough; I needed to keep that moist heat evenly distributed from top to bottom through the duration of cooking. I needed my cooking vessel to do more of the legwork—and my saucepan wasn’t cutting it.

A Dutch oven, on the other hand, has a thick, heavy bottom, deep sides, and a tight-fitting lid—all of which are meant to trap and distribute heat as evenly as possible, which seemed ideal. I cooked up a new batch, covering it as soon as I added my liquid. Traditionally, the lid is left off because risotto requires constant stirring, but here, I was free to use the lid to my advantage, ensuring, I hoped, that the top of the rice would stay as hot as the bottom. The first 19 minutes of cooking were easy—I had to lift the lid only twice for a quick stir—but after that, the liquid once again turned too viscous for the rice (still undercooked at this stage) to move around the pot without some manual assistance. Even over low heat, the rice still needed at least 5 minutes of constant stirring to turn uniformly al dente.

Adding most of the liquid at the beginning of cooking agitates the rice and decreases the need to stir.

Conceptually, this uneven heat problem was not unlike a challenge we faced when developing our recipe for Slow-Roasted Beef. Aiming to cook the roast as gently and evenly as possible, we turn the heat way down—and then shut the oven off completely, leaving the beef to rest in the still-warm environment until it crawls up to temperature. Here, the pot functions in much the same way, retaining heat long after it comes off the burner. If the risotto required its final stirring because the bottom was still cooking faster than the top, what if I removed the Dutch oven from the burner during the final few minutes? Without sitting over a direct flame, the rice should turn perfectly al dente just from the retained heat.

I made one last batch. This time, after the initial 19-minute covered cooking period, I gave the risotto a quick 3-minute stir to get the sauce to the right consistency, followed by a 5-minute, covered, off-heat rest. When I removed the lid, a big plume of steam escaped, indicating that my rice was indeed still hot throughout. I stirred in extra butter, a few herbs, and a squeeze of lemon juice, and had a perfectly creamy, velvety, and just barely chewy risotto—without going stir-crazy.

Almost Hands-Free Risotto with Parmesan and Herbs

SERVES 6

This recipe is more hands-off than traditional risotto recipes, but it does require precise timing. For that reason, we strongly recommend using a timer. The consistency of risotto is largely a matter of personal taste; if you prefer a looser texture, add more of the hot broth mixture in step 4.

5 cups chicken broth

1½ cups water

4 tablespoons unsalted butter

1 large onion, chopped fine

Salt and pepper

1 garlic clove, minced

2 cups Arborio rice

1 cup dry white wine

2 ounces Parmesan cheese, grated (1 cup)

2 tablespoons chopped fresh parsley

2 tablespoons chopped fresh chives

1 teaspoon lemon juice

1. Bring broth and water to boil in large saucepan over high heat. Reduce heat to medium-low to maintain gentle simmer.

2. Melt 2 tablespoons butter in Dutch oven over medium heat. Add onion and ¾ teaspoon salt and cook, stirring frequently, until onion is softened, 5 to 7 minutes. Add garlic and stir until fragrant, about 30 seconds. Add rice and cook, stirring frequently, until grains are translucent around edges, about 3 minutes.

3. Add wine and cook, stirring constantly, until fully absorbed, 2 to 3 minutes. Stir 5 cups hot broth mixture into rice; reduce heat to medium-low, cover, and simmer until almost all liquid has been absorbed and rice is just al dente, 16 to 19 minutes, stirring twice during cooking.

4. Add ¾ cup hot broth mixture and stir gently and constantly until risotto becomes creamy, about 3 minutes. Stir in Parmesan. Off heat, cover and let stand for 5 minutes. Stir in parsley, chives, lemon juice, and remaining 2 tablespoons butter. Adjust consistency with remaining hot broth mixture as needed. Season with salt and pepper to taste, and serve immediately.

variation

Almost Hands-Free Risotto with Chicken and Herbs

SERVES 6

Adding chicken breasts to the risotto turns a side dish into a main course. The thinner ends of the chicken breasts may be fully cooked by the time the broth mixture is added, with the thicker ends finishing about 5 minutes later.

5 cups chicken broth

2 cups water

1 tablespoon olive oil

2 (12-ounce) bone-in split chicken breasts, trimmed and halved crosswise

4 tablespoons unsalted butter

1 large onion, chopped fine

Salt and pepper

1 garlic clove, minced

2 cups Arborio rice

1 cup dry white wine

2 ounces Parmesan cheese, grated (1 cup)

2 tablespoons chopped fresh parsley

2 tablespoons chopped fresh chives

1 teaspoon lemon juice

1. Bring broth and water to boil in large saucepan over high heat. Reduce heat to medium-low to maintain gentle simmer.

2. Heat oil in Dutch oven over medium heat until just smoking. Add chicken, skin side down, and cook, without moving chicken, until golden brown, 4 to 6 minutes. Flip chicken and cook until second side is lightly browned, about 2 minutes. Transfer chicken to saucepan of simmering broth mixture and cook until chicken registers 160 degrees, 10 to 15 minutes. Transfer chicken to large plate.

3. Melt 2 tablespoons butter in now-empty Dutch oven over medium heat. Add onion and ¾ teaspoon salt and cook, stirring frequently, until onion is softened, 5 to 7 minutes. Add garlic and stir until fragrant, about 30 seconds. Add rice and cook, stirring frequently, until grains are translucent around edges, about 3 minutes.

4. Add wine and cook, stirring constantly, until fully absorbed, 2 to 3 minutes. Stir 5 cups hot broth mixture into rice; reduce heat to medium-low, cover, and simmer until almost all liquid has been absorbed and rice is just al dente, 16 to 19 minutes, stirring twice during cooking.

5. Add ¾ cup hot broth mixture and stir gently and constantly until risotto becomes creamy, about 3 minutes. Stir in Parmesan. Off heat, cover and let stand for 5 minutes.

6. Meanwhile, discard skin and bones from chicken and shred chicken into bite-size pieces. Gently stir parsley, chives, lemon juice, chicken, and remaining 2 tablespoons butter into risotto. Adjust consistency with remaining hot broth mixture as needed. Season with salt and pepper to taste, and serve immediately.

SECRETS TO ALMOST HANDS-FREE RISOTTO

1. ADD LOTS OF LIQUID AND PUT A LID ON IT A full 5 cups of liquid added at the start of cooking agitates the rice grains much like stirring, accelerating the release of creamy starch. Covering the pot helps distribute the heat evenly.

2. STIR, THEN REST A brief stir followed by a 5-minute rest provides additional insurance that the rice will be perfectly al dente, from the top of the pot to the bottom.

NO-FUSS CREAMY POLENTA

YVONNE RUPERTI, March/April 2010

When it comes to peasant roots, it doesn’t get much humbler than polenta. This simple, hearty dish of long-cooked cornmeal dates back to 16th-century Rome, where polenta sulla tavola was poured directly onto the table to soak up flavors from previous meals. These days, polenta passes for haute restaurant cuisine. Its nutty corn flavor is equally satisfying, whether embellished with simple butter and cheese or served as a base for everything from braised veal shanks to an exotic mushroom ragout. Most modern-day preparations take one of two forms: warm, porridge-like spoon food or cooked grains that are cooled until firm, then cut into squares to grill or fry. Both have their merits, but when the cold weather sets in, a bowl of the soothing, silky-textured stuff can’t be beat.

The recipe sounds easy enough: Boil water, whisk in cornmeal, and stir until the gruel-like concoction has softened. But the devil is in the details: Depending on the grind, polenta can take up to an hour to cook, and if you don’t stir it almost constantly during this time, it forms intractable clumps. Surely, after five centuries, it was time to find a better way.

CORNMEAL 101

Here’s what’s going on in a pot of polenta: When the starchy part of the corn kernels (the endosperm) comes in contact with hot water, it eventually absorbs liquid, swells, and bursts, releasing starch in a process known as gelatinization. At the same time, the grains soften, losing their gritty texture. But the tough pieces of endosperm require plenty of time and heat for the water to break through. And the pot must be stirred constantly; if polenta heats unevenly (such as in the hotter spots at the bottom of the pan), some of its starch gelatinizes much faster than the rest, forming little pockets of fully cooked polenta. This starch is so sticky that once these pockets form, it’s nearly impossible to fully break them up again. Stirring ensures that the entire pot cooks evenly, preventing lumps from forming in the first place.

You can shortcut the cooking and stirring with parboiled “instant” brands that are ready in just a few minutes, but tasters bemoaned these samples, complaining that they cooked up gluey, with lackluster flavor. It was time for a tour of cornmeal options. The typical supermarket offers a bewildering assortment of products, and their labels only confuse matters further. First, the same exact dried ground corn can be called anything from yellow grits to polenta to corn semolina. Labels also advertise “fine,” “medium,” and “coarse” grinds, but I quickly discovered that no standards for these definitions exist, and one manufacturer’s medium grind might be another’s heartiest coarse option. Then there’s the choice between whole-grain and degerminated corn (which is treated before grinding to remove both the hull and the germ but leaves the endosperm intact). With all this confusing nomenclature, I decided my best bet was to try everything and come up with my own system for identifying what worked best.

After testing a half-dozen styles, I eventually settled on the couscous-size grains of coarse-ground degerminated cornmeal (often labeled “yellow grits”); they delivered the hearty yet soft texture I was looking for, plus plenty of nutty corn flavor.

THINKING INSIDE THE GRAIN

The only downside: The large, coarse grains took a full hour to cook through, during which time the mixture grew overly thick and my arm started to ache from stirring. I had been sticking to the typical 4:1 ratio of water to cornmeal. After experimenting, I found a 5:1 ratio (or a full 7½ cups of water for 1½ cups of cornmeal) worked far better, producing just the right loose consistency.

Now for the hard part: whittling down the 1-hour cooking time and decreasing the stirring. The rate at which water penetrates the corn is proportional to temperature, but raising the heat, even in a heavy-bottomed pot, burned the polenta.

Maybe the key wasn’t in the cooking method, but in the cornmeal itself. There had to be a way to give that water a head start on penetrating the grains. Would soaking the cornmeal overnight help, the way it does with dried beans? I combined the cornmeal and water the night before, then cooked them together the next day. The results were uninspiring. While the grains did seem to absorb some of the liquid, this small improvement didn’t alter the cooking time enough to make this extra step worth it.

A pinch of baking soda makes for beautifully creamy polenta without the need for constant stirring.

Casting about for ideas, I came back to beans. The goal in cooking dried beans and dried corn is essentially identical. In a bean, water has to penetrate the hard outer skin to gelatinize the starch within. In a corn kernel, the water has to penetrate the endosperm. To soften bean skins and speed up cooking, some cooks advocate adding baking soda to the cooking liquid. Would this same ingredient work for cornmeal?

In my next batch of polenta, I added ¼ teaspoon baking soda to the water as soon as it came to a boil. To my delight, the polenta cooked up in 20 minutes flat. But the baking soda acted so effectively that the cooked porridge turned gluey, and had a strange, toasted, chemical flavor. Obviously, ¼ teaspoon of soda was too much; even half that was excessive. Just a pinch turned out to be plenty—it produced polenta that still cooked in 30 minutes without any gluey texture or objectionable flavors.

The solution for cutting back on the stirring time came to me by accident. I’d just whisked the cornmeal into the boiling water when I got called away from the kitchen. Without thinking, I threw a lid on the pot (the traditional method is to leave the polenta uncovered), turned the heat down to its lowest level, and left the polenta to sputter untouched for nearly the entire 30 minutes. Rushing back to the stove, I expected to find a clumpy, burnt-on-the-bottom mess. To my surprise, I found perfectly creamy polenta when I lifted the lid. The baking soda must have helped the granules break down and release their starch in a uniform way so that the bottom layer didn’t cook any faster than the top. And the combination of covering the pot and adjusting the heat to low, wispy flames cooked the polenta so gently and evenly that the result was lump-free, even without vigorous stirring.

I repeated this new approach, finding that after one relatively brief whisk as soon as the ingredients went in and another, shorter one 5 minutes later, I didn’t even have to lift the lid until it was time to add the cheese. A full 2 cups of grated Parmesan plus a pair of butter pats stirred in at the last minute gave this humble mush enough nutty tang and richness to make it a satisfying dish, with or without a topping—and with the barest amount of effort.

SERVES 4 TO 6

Coarse-ground degerminated cornmeal, such as yellow grits, works best in this recipe. Avoid instant and quick-cooking products as well as whole-grain, stone-ground, and regular cornmeal. Do not omit the baking soda—it reduces the cooking time and makes for a creamier polenta. The polenta should do little more than emit wisps of steam. If it bubbles or sputters even slightly after the first 10 minutes, the heat is too high and you may need a flame tamer. A flame tamer can be found at most kitchen supply stores; alternatively, you can fashion your own from a ring of foil. For a main course, serve the polenta with a topping (recipes follow) or with a wedge of rich cheese or a meat sauce. Served plain, the polenta makes a great accompaniment to stews and braises.

7½ cups water

Salt and pepper

Pinch baking soda

1½ cups coarse-ground cornmeal

4 ounces Parmesan cheese, grated (2 cups), plus extra for serving

2 tablespoons unsalted butter

1. Bring water to boil in heavy-bottomed large saucepan over medium-high heat. Stir in 1½ teaspoons salt and baking soda. Slowly pour cornmeal into water in steady stream while stirring back and forth with wooden spoon or rubber spatula. Bring mixture to boil, stirring constantly, about 1 minute. Reduce heat to lowest possible setting and cover saucepan.

2. After 5 minutes, whisk polenta to smooth out any lumps that may have formed, about 15 seconds. (Make sure to scrape down sides and bottom of saucepan.) Cover and continue to cook, without stirring, until grains of polenta are tender but slightly al dente, about 25 minutes longer. (Polenta should be loose and barely hold its shape but will continue to thicken as it cools.)

3. Off heat, stir in Parmesan and butter and season with pepper to taste. Let polenta stand, covered, for 5 minutes. Serve, passing extra Parmesan separately.

accompaniments

Broccoli Rabe, Sun-Dried Tomato, and Pine Nut Topping

SERVES 4 TO 6

1½ cup oil-packed sun-dried tomatoes, chopped coarse

3 tablespoons extra-virgin olive oil

6 garlic cloves, minced

½ teaspoon red pepper flakes

Salt and pepper

1 pound broccoli rabe, trimmed and cut into 1½-inch pieces

¼ cup chicken or vegetable broth

2 tablespoons pine nuts, toasted

¼ cup grated Parmesan cheese

Cook sun-dried tomatoes, oil, garlic, pepper flakes, and ½ teaspoon salt in 12-inch nonstick skillet over medium-high heat, stirring frequently, until garlic is slightly toasted, about 2 minutes. Add broccoli rabe and broth, cover, and cook until broccoli rabe turns bright green, about 2 minutes. Uncover and cook, stirring frequently, until most of broth has evaporated, about 3 minutes. Season with salt and pepper to taste. Spoon mixture over individual portions of polenta and top with pine nuts and Parmesan. Serve.

Sautéed Cherry Tomato and Fresh Mozzarella Topping

SERVES 4 TO 6

3 tablespoons extra-virgin olive oil

2 garlic cloves, sliced thin

Pinch red pepper flakes

Pinch sugar

1½ pounds cherry tomatoes, halved

Salt and pepper

3 ounces fresh mozzarella cheese, shredded (¾ cup)

2 tablespoons shredded fresh basil

Cook oil, garlic, pepper flakes, and sugar in 12-inch nonstick skillet over medium-high heat until fragrant and sizzling, about 1 minute. Stir in tomatoes and cook until just beginning to soften, about 1 minute. Season with salt and pepper to taste. Spoon mixture over individual portions of polenta and top with mozzarella and basil. Serve.

Our recipe for Creamy Parmesan Polenta relies on heat so low it barely disturbs the pot’s contents. A flame tamer can help to ensure that the heat is as gentle as possible.

Squeeze a 3-foot length of aluminum foil into a ½-inch rope. Twist the rope into a ring the size of the burner.

Risotto has been a staple in American restaurants and home kitchens for years, but farrotto has only recently gained a footing stateside. As the name suggests, it’s a twist on the classic Italian rice-based dish, made with farro, an ancient form of wheat that’s been grown in Italy for centuries and that boasts a nutty flavor and a tender chew. Using this whole grain instead of rice yields a more robust dish that still cooks relatively quickly and functions well as a blank slate for any type of flavor addition—from cheese and herbs to meats and vegetables. There’s just one pitfall to farrotto: bran. Arborio or carnaroli rices have been stripped of their bran layer and thus readily give up their amylopectin, the starch molecule that makes risotto creamy. Farro retains most of its bran (how much depends on whether it’s been “pearled,” or had its bran at least partially rubbed away), which gives it bite and earthy flavor but also traps the starch inside the grain. Hence, most farrottos lack risotto’s velvety body and cohesion. I wanted both: the distinct flavor and chew of farro with the creamy consistency of risotto.

My instinct was to first try pearled farro; since it has less bran, it might cook up creamier. I had a leg up on a basic cooking method, which I’d borrow from our Almost Hands-Free Risotto with Parmesan and Herbs. The trick in that recipe is to add most of the liquid up front, rather than in several stages, which helps the grains cook evenly so that you need to stir only a couple of times rather than constantly. We also use a lidded Dutch oven, which helps trap and distribute the heat evenly so every grain is tender.

Pulsing the farro in a blender before cooking allows it to release some of its trapped starch, producing a creamy-textured dish.

To start, I softened onion and garlic in butter, added the farro to toast in the fat, and finally added the liquid. But the pearled farro not only lacked the robust flavor of whole farro but also resulted in farrotto that was too thin. I would have to stick with whole farro.

My breakthrough came from an outlier farrotto recipe, which called for “cracking” the farro before cooking by soaking the grains overnight to soften them and then blitzing them in a food processor. This gave the starch an escape route and yielded a silkier dish. The only drawback was that lengthy soak.

I tried skipping the soak, and I also tried a hot soak to see if I could soften the grains quickly. In both cases the hard grains just danced around the processor bowl without breaking. Switching to a blender created a vortex that drew the unsoaked grains into the blade. Six pulses cracked about half of them so that there was plenty of starch but still enough chew.

Seasoned with Parmesan, herbs, and lemon juice, my farrotto was hearty and flavorful—and more satisfying than any risotto I’ve eaten.

Parmesan Farrotto

SERVES 6

We prefer the flavor and texture of whole farro. Do not use quick-cooking or pearled farro. The consistency of farrotto is a matter of personal taste; if you prefer a looser texture, add more of the hot broth mixture in step 6.

1½ cups whole farro

3 cups chicken broth

3 cups water

4 tablespoons unsalted butter

½ onion, chopped fine

1 garlic clove, minced

2 teaspoons minced fresh thyme

Salt and pepper

2 ounces Parmesan, grated (1 cup)

2 tablespoons minced fresh parsley

2 teaspoons lemon juice

1. Pulse farro in blender until about half of grains are broken into smaller pieces, about 6 pulses.

2. Bring broth and water to boil in medium saucepan over high heat. Reduce heat to medium-low to maintain gentle simmer.

3. Melt 2 tablespoons butter in large Dutch oven over medium-low heat. Add onion and cook, stirring frequently, until softened, 3 to 4 minutes. Add garlic and stir until fragrant, about 30 seconds. Add farro and cook, stirring frequently, until grains are lightly toasted, about 3 minutes.

4. Stir 5 cups hot broth mixture into farro mixture, reduce heat to low, cover, and cook until almost all liquid has been absorbed and farro is just al dente, about 25 minutes, stirring twice during cooking.

5. Add thyme, 1 teaspoon salt, and ¾ teaspoon pepper and continue to cook, stirring constantly, until farro becomes creamy, about 5 minutes.

6. Remove pot from heat. Stir in Parmesan, parsley, lemon juice, and remaining 2 tablespoons butter. Season with salt and pepper to taste. Adjust consistency with remaining hot broth mixture as needed. Serve immediately.

Pilaf made with orzo, the rice-shaped pasta, is culinary sleight of hand at its finest. What look to be giant grains of rice reveal their true nature after just one bite, presenting a firm-yet-tender texture that is far removed from rice’s dull chew. Unfortunately, most of the versions I’ve tasted have been bland at best—little more than a generic starch used to bulk up a meal. I wanted to design a better pilaf, finessed in technique and strong in flavor; all in all, an orzo pilaf worth the effort.

A survey of orzo pilaf recipes yielded mixed results and little insight. Technique, for the most part, cleaved close to standard pilaf procedure: Sauté the orzo briefly with aromatics, then simmer in a covered pot until tender. Flavors ran the gamut from bland to overwrought. I quickly made a decision to focus on technique and keep the flavors of my pilaf simple. Returning to the “orzo as rice” conceit, I borrowed the clean, classic flavors of Parmesan risotto: butter, alliums, white wine, broth, and cheese.

Toasting the orzo before adding the cooking liquid ups the flavor in this simple yet elegant side dish.

I tested two preparation methods head to head: cooking the orzo as I would rice, covered over a low flame, and cooking as I would pasta, in an abundance of water at a raging boil. Cooked as rice, the orzo failed to fully hydrate and was chalky, though attractively creamy. Cooked as pasta, the orzo was al dente in a fraction of the time but it tasted bland. Because neither method seemed ideal, I turned to a hybrid cooking method.

Starting with an uncovered pan, I sautéed the orzo with butter and onions and then added the liquid. High heat yielded unevenly cooked orzo and a sticky mess on the pan bottom. Low heat produced creamy but too-soft orzo. Moderate heat yielded just what I wanted: firm, slick orzo lightly napped with a creamy coating.

While the texture was ideal, the flavor was still bland. As I was already sautéing the orzo, I wondered if I could simply extend the time it spent browning in the butter. The results were stunning. Toasted light brown, the pasta was now nutty, sweet, and notably “wheatier” in flavor. I toasted several batches of orzo to varying degrees of doneness—pale yellow to a deep mahogany—and realized that, as with caramel, the darker the color, the richer the flavor (shy of burning, of course). Tasters most enjoyed orzo taken to golden brown. Attentive stirring while toasting was crucial to prevent scorching.

With the technique down, it was quick work to finesse the risotto-inspired flavors I had chosen. Olive oil and vegetable oil couldn’t touch butter’s nutty, sweet charm. For alliums, I tried onion, shallot, and garlic, but none provided enough depth solo. Onion and shallot proved redundant, but onion and garlic gave the dish both low-end sweetness and full-range depth. Dry white wine is a classic flavor in risotto, but I tossed dry vermouth into the tasting as well. Tasters unanimously preferred the latter’s fuller, herbaceous flavor. For cooking liquid, I limited the choices to canned broth. Beef tasted tinny; my tasters much preferred chicken broth.

Finely grated Parmesan melted quickly and made the pilaf creamier. A pinch of nutmeg—an Italian secret in cream sauces—pointed up the cheese’s nuttiness. For a bit of green to perk things up, I tried a handful of different herbs. Each added a distinct note, but in the end I chose an easier route and simply tossed in frozen peas. The pilaf’s ambient heat warmed them through and magnified the peas’ glossy green hue.

Toasted Orzo with Peas and Parmesan

SERVES 6 TO 8

We prefer dry vermouth here, but you can substitute dry white wine, if desired.

2 tablespoons unsalted butter

1 onion, chopped fine

Salt and pepper

2 garlic cloves, minced

1 pound orzo

3½ cups chicken broth

¾ cup dry vermouth or dry white wine

1¾ cups frozen peas

2 ounces Parmesan cheese, grated (1 cup)

Pinch ground nutmeg

1. Melt butter in 12-inch nonstick skillet over medium-high heat. Add onion and ¾ teaspoon salt and cook, stirring frequently, until onion has softened and is beginning to brown, 5 to 7 minutes. Add garlic and cook until fragrant, about 30 seconds. Add orzo and cook, stirring frequently, until most of orzo is lightly browned and golden, 5 to 6 minutes. Off heat, add broth and vermouth. Bring to boil over medium-high heat; reduce heat to medium-low and simmer, stirring occasionally, until all liquid has been absorbed and orzo is tender, 10 to 15 minutes.

2. Stir in peas, Parmesan, and nutmeg. Off heat, let stand until peas are heated through, about 2 minutes. Season with salt and pepper to taste, and serve.

variation

Toasted Orzo with Fennel, Orange, and Olives

Add 1 small fennel bulb, stalks discarded, halved, cored, and cut into ¼-inch dice, ¾ teaspoon fennel seeds, and pinch red pepper flakes along with onion. Add 1 teaspoon grated orange zest along with garlic and substitute ½ cup coarsely chopped olives for peas.

Although couscous traditionally functions as a sauce absorber beneath North African stews and braises, it works equally well as a lighter, quicker alternative to everyday side dishes like rice pilaf and mashed potatoes. The tiny grains of pasta, made by rubbing together moistened semolina granules, readily adapt to any number of flavorful add-ins—from grassy fresh herbs like cilantro and parsley to heady spices like cumin and coriander and sweeter elements like raisins and dates. Best of all, the whole operation, from box to bowl, takes about 5 minutes.

At least that’s what the back-of-the-box instructions say. I quickly realized that such convenience comes at a cost. No matter how precisely I followed the directions—measure and boil water, stir in couscous, cover and let stand off heat for 5 minutes, fluff with fork—the results were discouragingly similar to wet sand: bland, blown-out pebbles that stuck together in clumps. And it wasn’t just one brand’s poor instruction. Every box I bought spelled out the same steps.

We briefly sauté the couscous in butter to boost its flavor and ensure that the grains cook up fluffy.

I’m no expert on North African cuisine, but I’d read enough about couscous to know that it has far more potential than my efforts were suggesting. Then, as I was researching how the grains are made, I realized my problem: the box—both its contents and its cooking instructions. According to traditional couscous-making practices, the uncooked grains are steamed twice in a double boiler–shaped vessel called a couscoussière, from which the grains emerge fluffy and separate. The commercial staple we find on grocery store shelves, however, is far more processed: The grains are flash-steamed and dried before packaging. When exposed to the rigors of further cooking, this parcooked couscous—more or less a convenience product—turns to mush. That’s why the box instructions are so simple: A quick reconstitution in boiling water is all the grains can stand.

To bring some much-needed flavor to the dish, I tried dry-toasting the grains in the pan and then stirring in boiling water—to no avail: The pasta grains burned before they had a chance to develop any real flavor. Then I recalled a popular trick used on another grain that, without some finesse, can also cook up woefully bland: rice. The “pilaf method” calls for briefly sautéing the grains in hot fat before liquid is introduced. So for my next batch of couscous, I melted a small amount of butter, which, as I’d hoped, coated the grains nicely, allowing them to brown gently and uniformly and helping them cook up fluffy and separate. To bump up the flavor even further, I replaced half of the water with chicken broth. Now I was getting somewhere: After absorbing the hot stock-based liquid, the couscous grains were flavorful enough to stand on the plate without a sauce.

I figured my work was just about done—until I spied the two dirty pans in the sink. Given that the dish took all of 5 minutes to cook, I was determined to do better when it came to cleanup. Then it dawned on me: Since my saucepan was already hot from toasting the grains, why not simply add room-temperature liquid to it instead of going to the trouble to heat the liquid in a separate pan? Sure enough, that did it. The residual heat from the pan boiled the liquid almost instantly—it was like deglazing a skillet after searing. On went the lid, and after a brief rest and a quick fluff with a fork, my couscous was perfect.

Basic Couscous

SERVES 4 TO 6

Do not substitute large-grain couscous (also known as Israeli couscous) in this recipe; it requires a much different cooking method. Use a large fork to fluff the couscous grains; a spoon or spatula can mash its light texture.

2 tablespoons unsalted butter

2 cups couscous

1 cup water

1 cup chicken broth

Salt and pepper

1. Melt butter in medium saucepan over medium-high heat. Add couscous and cook, stirring frequently, until grains are just beginning to brown, about 5 minutes.

2. Add water, broth, and 1 teaspoon salt; stir briefly to combine, cover, and remove saucepan from heat. Let stand until grains are tender, about 7 minutes. Uncover and fluff grains with fork. Season with pepper to taste, and serve.

variations

Couscous with Dates and Pistachios

Increase butter to 3 tablespoons and add ½ cup chopped dates, 1 tablespoon finely grated fresh ginger, and ½ teaspoon ground cardamom to saucepan with couscous in step 1. Increase water to 1¼ cups. Stir ¾ cup toasted chopped pistachios, 3 tablespoons minced fresh cilantro, and 2 teaspoons lemon juice into couscous before serving.

Couscous with Dried Cherries and Pecans

Increase butter to 3 tablespoons and add ½ cup chopped dried cherries, 2 minced garlic cloves, ¾ teaspoon garam masala, and ⅛ teaspoon cayenne pepper to saucepan with couscous in step 1. Increase water to 1¼ cups. Stir ¾ cup toasted chopped pecans, 2 thinly sliced scallions, and 2 teaspoons lemon juice into couscous before serving.

In the span of a decade, quinoa, a seed with humble South American roots, has gone from obscurity to mass consumption in America. I’ve always assumed its rapid ascent is mainly due to awareness of its health benefits (it’s a nearly complete protein that’s rich in fiber). While in theory the cooked grain (almost no one calls quinoa a seed) has an appealingly nutty flavor and crunchy texture, in practice it more often turns into a mushy mess with washed-out flavor and an underlying bitterness.

Pilaf recipes that call for cooking the grain with onion and other flavorings don’t help matters. If it’s blown out and mushy, quinoa pilaf is no better than the plain boiled grain on its own. I was determined to develop a foolproof approach to quinoa pilaf that I’d want to make not because it was healthy but because it tasted great.

My first clue as to what might go wrong with the usual quinoa pilaf surfaced as soon as I gathered up recipes to try. All called for softening onion in butter or oil, adding quinoa to the pan and toasting it in the same fat, then pouring in liquid, and simmering covered until the grains were cooked through and the liquid was absorbed. Almost without exception, these recipes used a 2:1 ratio of liquid to quinoa. Could that be the problem?

To find out, I put together a basic working recipe: Soften finely chopped onion in butter in a saucepan, stir in quinoa and water, cover, and cook until tender. I then tested a range of water-to-quinoa ratios and found that, while 2 to 1 might be the common rule, 1 to 1 was nearly perfect. To allow for evaporation, I tweaked this ratio just slightly, using a bit more water than quinoa (1¾ cups water to 1½ cups quinoa). After about 20 minutes of covered simmering, the quinoa was tender, with a satisfying bite.

Or at least most of it was. There was a ½-inch ring of overcooked seeds around the pot’s circumference. The heat of the pot was cooking the outer grains faster than the interior ones. To even things out, my first thought was to stir the quinoa halfway through cooking, but I feared that I would turn my pilaf into a starchy mess, as so easily happens with rice. But I needn’t have worried. A few gentle stirs at the midway point gave me perfectly cooked quinoa, with no ill effects. Why? While quinoa is quite starchy—more so than long-grain white rice—it also contains twice the protein of white rice. That protein is key, as it essentially traps the starch in place so you can stir it without creating a gummy mess.

Dry-toasting the quinoa and using a nearly 1:1 ratio of grains to water produces flavorful and tender quinoa pilaf.

The texture of the quinoa improved further when I let it rest, covered, for 10 minutes before fluffing. This allowed the grains to finish cooking gently and firm up, making them less prone to clumping.

It was time to think about the toasting step. While the majority of quinoa on the market has been debittered, some bitter-tasting compounds (called saponins) remain on the exterior. We have found that toasting quinoa in fat can exacerbate this bitterness, so I opted to dry-toast the grains in the pan before sautéing the onion. After about 5 minutes in the pan, the quinoa smelled like popcorn. This batch was nutty and rich-tasting, without any bitterness.

I finished the quinoa simply, with herbs and lemon juice, ensuring that my quinoa stayed in the spotlight—right where it belonged.

Quinoa Pilaf

SERVES 4 TO 6

If you buy unwashed quinoa, rinse it and then spread it out over a clean dish towel to dry for 15 minutes before cooking.

1½ cups prewashed white quinoa

2 tablespoons unsalted butter or extra-virgin olive oil

1 small onion, chopped fine

¾ teaspoon salt

1¾ cups water

3 tablespoons chopped fresh cilantro, parsley, chives, mint, or tarragon

1 tablespoon lemon juice

1. Toast quinoa in medium saucepan over medium-high heat, stirring frequently, until quinoa is very fragrant and makes continuous popping sound, 5 to 7 minutes; transfer to bowl.

2. Add butter to now-empty saucepan and melt over medium-low heat. Add onion and salt and cook, stirring frequently, until onion is softened and light golden, 5 to 7 minutes.

3. Stir in water and toasted quinoa, increase heat to medium-high, and bring to simmer. Cover, reduce heat to low, and simmer until grains are just tender and liquid is absorbed, 18 to 20 minutes, stirring once halfway through cooking. Remove pan from heat and let sit, covered, for 10 minutes.

4. Fluff quinoa with fork, stir in herbs and lemon juice, and serve.

variation

Quinoa Pilaf with Chipotle, Queso Fresco, and Peanuts

Add 1 teaspoon chipotle chile powder and ¼ teaspoon ground cumin with onion and salt. Substitute ½ cup crumbled queso fresco; ½ cup roasted unsalted peanuts, chopped coarse; and 2 thinly sliced scallions for herbs. Substitute 4 teaspoons lime juice for lemon juice.

Tabbouleh has long been a meze staple in the Middle East, but these days it can be found in the refrigerator case of virtually every American supermarket. Its brief (and healthful) ingredient list explains its popularity: Chopped fresh parsley and mint, tomatoes, onion, and bits of nutty bulgur are tossed with lemon and olive oil for a refreshing appetizer or side dish. It all sounds easy enough, but most versions are hopelessly soggy, with flavor that is either too bold or too bland.

Another problem is that there’s no agreement on the correct proportions for tabbouleh. Middle Eastern cooks favor loads of parsley (75 to 90 percent of the salad), employing a sprinkle of bulgur as a texturally interesting garnish. Most American recipes invert the proportions, creating an insipid pilaf smattered with herbs. I decided to take a middle-of-the-road approach for a dish that would feature a hefty amount of parsley as well as a decent amount of bulgur.

Soaking the bulgur in some of the liquid from the tomatoes, plus a bit of lemon juice, enhances its flavor.

Bulgur needs only to be reconstituted in cool water, but specific advice on how to prepare the grains is all over the map. Rehydration times range from 5 minutes all the way up to several hours, and while some recipes call for just enough liquid to plump the grains, others soak the bulgur in lots of water and then squeeze out the excess.

Working with ½ cup of medium-grind bulgur, I experimented with innumerable permutations of time and amount of water. I found that the grains required at least 90 minutes to tenderize fully. And the less liquid I used, the better the texture. Excess water only made the grains heavy, damp, and bland. A mere ¼ cup of liquid was enough for ½ cup of dried bulgur. With my method settled, I switched to soaking the bulgur in lemon juice instead of water, as some cookbooks recommend.

Next up: parsley. One and a half cups of chopped parsley and ½ cup of chopped mint still put the emphasis on the bright, peppery parsley but didn’t discount the lemony bulgur and refreshing mint.

As for the rest of the salad, 6 tablespoons of extra-virgin olive oil tempered the tart lemon juice, and three chopped ripe tomatoes and two sliced scallions (preferred over onion) rounded out the mix. A smidge of cayenne pepper added zing. Tasters soundly rejected garlic and cucumbers, complaining that they detracted from the salad’s clean flavor and overall texture.

Tasters were now happy with the texture, but the flavors weren’t cohesive—my method wasn’t giving them time to blend. To solve this, I reworked my method to give the bulgur a chance to absorb any liquid—namely, olive oil and juices from the tomatoes—in the salad. Soaking the bulgur for 30 to 40 minutes, until it began to soften, and then combining it with the remaining ingredients and letting it sit for an hour until fully tender gave everything time to mingle.

I had just one final issue to deal with. Depending on variety, the tomatoes’ liquid sometimes diluted the salad’s flavor and made it soupy. The solution? Tossing the tomatoes in salt and letting them drain in a colander drew out their moisture, precluding sogginess. Plus, I could use the savory liquid to soak the bulgur, thereby upping its flavor. I used 2 tablespoons of the tomato liquid (along with an equal amount of lemon juice) to soak the bulgur, whisking the remaining 2 tablespoons of lemon juice with oil for the dressing. At last, here was tabbouleh with fresh, penetrating flavor and a light texture.

Tabbouleh

SERVES 4

Don’t confuse bulgur with cracked wheat, which has a much longer cooking time and will not work in this recipe. Serve the salad with the crisp inner leaves of romaine lettuce and wedges of pita bread.

3 tomatoes, cored and cut into ½-inch pieces

Salt and pepper

½ cup medium-grind bulgur, rinsed

¼ cup lemon juice (2 lemons)

6 tablespoons extra-virgin olive oil

⅛ teaspoon cayenne pepper

1½ cups minced fresh parsley

½ cup minced fresh mint

2 scallions, sliced thin

1. Toss tomatoes with ¼ teaspoon salt in fine-mesh strainer set over bowl and let drain, tossing occasionally, for 30 minutes; reserve 2 tablespoons drained tomato juice. Toss bulgur with 2 tablespoons lemon juice and reserved tomato juice in bowl and let sit until grains begin to soften, 30 to 40 minutes.

2. Whisk remaining 2 tablespoons lemon juice, oil, cayenne, and ¼ teaspoon salt together in large bowl. Add tomatoes, bulgur, parsley, mint, and scallions and toss gently to combine. Cover and let sit at room temperature until flavors have blended and bulgur is tender, about 1 hour. Before serving, toss salad to recombine and season with salt and pepper to taste.

variation

Spiced Tabbouleh

Add ¼ teaspoon ground cinnamon and ¼ teaspoon ground allspice to dressing with cayenne.

Lentils may not get points for glamour, but when properly cooked and dressed up in a salad with bright vinaigrette and herbs, nuts, and cheeses, the legumes’ earthy, almost meaty depth and firm-tender bite make a satisfying side dish for almost any meal.

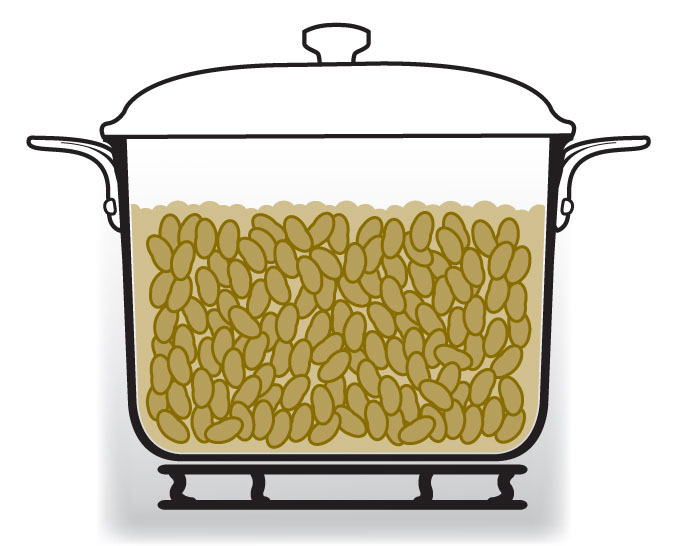

The trouble is, perfectly cooked lentils are never a given. Too often, either their skins burst and their flesh disintegrates into starchy mush or they don’t cook through completely and retain chewy skin and a hard, crunchy core. Before I started adding accoutrements, I had to nail down a reliable way to produce tender, buttery lentils with soft, unbroken skins. And because the tiny, shape-retaining French green lentils we favor can be hard to come by, I was also determined to develop an approach that would yield perfect results with whatever lentil variety my supermarket had to offer.

An hour-long soak in a warm brine and salt in the cooking water produces lentils with creamy centers and soft, tender skins.

Fortunately, the test kitchen’s previous work with bean cookery gave me a good idea of how to improve the skins. We’ve discovered that, odd as it may sound, brining beans overnight softens their outer shells and makes them less likely to burst. The explanation is twofold: As the beans soak, the sodium ions from the salt replace some of the calcium and magnesium ions in the skins. By replacing some of the mineral ions, the sodium ions weaken the pectin in the skins, allowing more water to penetrate and leading to a more pliable, forgiving texture. But with beans, brining requires an overnight rest to be most effective. Fortunately, due to the lentils’ smaller, flatter shape, I found that just a few hours of brining dramatically cuts down on blowouts. I also had another idea for hastening the process: Since heat speeds up all chemical reactions, I managed to reduce that time to just an hour by using warm water in the salt solution.

Another way to further reduce blowouts would be to cook the lentils as gently as possible. But I could see that even my stovetop’s low setting still agitated the lentils too vigorously. I decided to try the oven, hoping that its indirect heat would get the job done more gently—and it did. And while the oven did increase the cooking time from less than 30 minutes to nearly an hour, the results were worth the wait: Virtually all of the lentil skins were tender yet intact.

Despite the lentils’ soft, perfect skins, their insides tended to be mushy, not creamy. It occurred to me that I could try another very simple trick with salt: adding it to the cooking water. Many bean recipes (including ours) shy away from adding salt during cooking because it produces firmer interiors that can be gritty. Here’s why: While a brine’s impact is mainly confined to the skin, heat (from cooking) affects the inside of the bean, causing sodium ions to move to the interior, where they slow the starches’ ability to absorb water. But a firmed-up texture was exactly what my mushy lentils needed. Could a problem for beans prove to be the solution for lentils? Sure enough, when I added ½ teaspoon of salt to the cooking water, the lentils went from mushy to firm yet creamy.

I had just one remaining task to tackle: enriching the flavor of the lentils. Swapping some of the cooking water for chicken broth solved the problem. Finally, I had tender, flavorful lentils that were ready for the spotlight.

Lentil Salad with Olives, Mint, and Feta

SERVES 4 TO 6

French green lentils, or lentilles du Puy, are our preferred choice for this recipe, but it works with any type of lentil except red or yellow. Brining helps keep the lentils intact, but if you don’t have time, they’ll still taste good without it. The salad can be served warm or at room temperature.

Salt and pepper

1 cup lentils, picked over and rinsed

5 garlic cloves, lightly crushed and peeled

1 bay leaf

5 tablespoons extra-virgin olive oil

3 tablespoons white wine vinegar

½ cup pitted kalamata olives, chopped coarse

1 large shallot, minced

½ cup chopped fresh mint

1 ounce feta cheese, crumbled (¼ cup)

1. Dissolve 1 teaspoon salt in 1 quart warm water (about 110 degrees) in bowl. Add lentils and soak at room temperature for 1 hour. Drain well.

2. Adjust oven rack to middle position and heat oven to 325 degrees. Combine lentils, 1 quart water, garlic, bay leaf, and ½ teaspoon salt in medium ovensafe saucepan. Cover, transfer saucepan to oven, and cook until lentils are tender but remain intact, 40 minutes to 1 hour.

3. Drain lentils well, discarding garlic and bay leaf. In large bowl, whisk oil and vinegar together. Add lentils, olives, and shallot and toss to combine. Season with salt and pepper to taste.

4. Transfer to serving dish, gently stir in mint, and sprinkle with feta. Serve warm or at room temperature.

Soupy beans, or frijoles de la olla, are a staple at most Mexican tables and for good reason. The humble preparation, which supposedly derives from the bean suppers that caballeros cooked over fires on the range, typically consists of beans, a bit of pork or lard, and just a few herbs and aromatics like onion, chiles, and maybe tomato. Once the flavors meld and the cooking liquid thickens slightly from the beans’ starches, the dish is as satisfying as a rich stew. Add a side of rice and you’ve got a meal.

There are numerous iterations, but my favorite might be frijoles borrachos, or drunken beans, in which pinto beans are cooked with beer or tequila. The alcohol should be subtle, lending the pot brighter, more complex flavor than beans cooked in water alone. And yet, when I’ve made the dish at home, the alcohol tastes either overwhelmingly bitter, raw, and boozy or is so faint that I can’t tell it’s there. I’ve also never gotten the consistency of the liquid quite right—that is, thickened just enough that it’s brothy, not watery.

I set my sights on a pot that featured creamy, intact beans and a cooking-liquid-turned-broth that wasn’t awash in alcohol but that offered more depth than a batch of plain old pintos.

Adding tequila at the beginning of cooking and beer partway through offers complex, not boozy, flavor.

HUMBLE BEGINNINGS

My first step was to nail down the basics of Mexican pot beans. I knew that canned beans were out here, since this recipe requires a full-flavored bean cooking liquid that only dried beans can impart. Step one was to soak the dried beans overnight in salty water—an adjustment we make to the usual plain-water soak because we’ve learned that sodium weakens the pectin in the beans’ skins and, thus, helps them soften more quickly. For the pork element, I chose bacon; plenty of recipes called for it, and its smoky depth would ratchet up the flavor of the dish. I browned a few sliced strips in a Dutch oven. Setting aside the meat, I left the rendered fat to sauté the aromatics: a chopped onion and a couple of poblano chiles, plus minced garlic. Once they had softened, I added the drained beans, a few cups of water, bay leaves, and salt and slid the vessel into a low (275-degree) oven, where the beans would simmer gently for the better part of an hour—no need to stir them or take the risk that they’d burst.

HOP TO IT

I gave the beans an hour head start before adding the beer. Though some recipes call for incorporating it from the start of cooking, we’ve learned that cooking dried beans with acidic ingredients (and beer is definitely acidic) strengthens the pectin in the beans’ skins and prevents them from fully softening. As for what type of beer to use, recipes were divided between dark and light Mexican lagers, but I reached for the former, figuring that a full-flavored pot of beans would surely require a full-flavored brew. I used 1 cup, splitting the difference between recipes that called for a full 12-ounce bottle and those that went with just a few ounces. I slid the pot back into the oven to meld the flavors and thicken the liquid. But the results I returned to half an hour later weren’t what I was hoping for. Most noticeable was the beer’s bitter flavor. The extra liquid had also thinned out the broth so that it lacked body.

I figured that reducing the amount of beer would thereby reduce the bitterness and the volume of liquid, too. But when I used just ½ cup, the “drunken” flavor was lost. Next, I tried cooking a full cup by itself before adding it to the pot when the beans were done cooking, hoping to increase its flavor and drive off some bitterness. Wrong again. The reduced beer tasted more bitter than ever, and some research explained why: The compounds responsible for the complex aroma and flavor of beer are highly volatile and dissipate quickly when boiled, while those that contribute bitterness are more stable and, in the absence of other flavors, become more pronounced. Given that, I tried adding the beer to the pot just before serving. This did help the beer retain a more complex flavor, but it also retained more of its raw-tasting alcohol.

A COCKTAIL OF FLAVOR