DESSERTS

Foolproof All-Butter Pie Dough

Building a Better Deep-Dish Apple Pie

Old-Fashioned Chocolate Layer Cake

The Best Homemade Frozen Yogurt

I have always been a huge fan of baked fruit desserts, especially cobblers. What could be better than a hot and bubbly fruit filling matched with tender biscuits? As simple (and appealing) as this sounds, why do so many of us end up with a filling that is sickeningly sweet and overspiced? Why is the filling so often runny, or, on the flip side, so thick and gloppy? Why are the biscuits, the most common choice of topping for cobblers, too dense, dry, and heavy? My goal was to create a filling in which the blueberries (my choice for fruit) were allowed to cook until lightly thickened. I wanted their natural sweetness to sing a cappella without being overshadowed by a symphony of sugar and spice. The biscuits would stand tall with structure, be crisp on the outside and light and buttery on the inside, and complement the filling. Most important, it had to be easy.

THE FILLING GOES FIRST

The basic ingredients found in most cobbler fillings are fruit, sugar, thickener (flour, arrowroot, cornstarch, potato starch, or tapioca), and flavorings (lemon zest, spices, etc.). The fruit and sugar are easy: Take fresh blueberries and add enough sugar such that the fruit neither remains puckery nor turns saccharine. For 6 cups of berries, I found ½ cup sugar to be ideal—and far less than the conventional amount of sugar, which in some recipes exceeds 2 cups.

A cornstarch-thickened filling topped with cornmeal and buttermilk–enhanced biscuits makes for a speedy and intensely flavored cobbler.

Some recipes swear by one thickener and warn that other choices will ruin the filling. I found this to be partly true. Tasters were all in agreement that flour—the most common choice in recipes—gave the fruit filling an unappealing starchy texture. Most tasters agreed that tapioca thickened the berry juices nicely, but the soft beads of starch left in the fruit’s juices knocked out this contender. (Also, when exposed to direct heat, as in a cobbler, the tapioca that remains near the surface of the fruit quickly turns as hard as Tic-Tacs.) Arrowroot worked beautifully, but this starch is far too expensive and can be difficult to find. Cornstarch, the winner, thickened the juices without altering the blueberry flavor or leaving any visible traces of starch behind.

Lemon juice as well as grated lemon zest brightened the fruit flavor, and, as for spices, everyone preferred cinnamon. Other flavors simply got in the way.

NOT YOUR AVERAGE TOPPING

For the topping, my guiding principle was ease of preparation. A biscuit topping was the way to go, and I had my choice of two types: dropped and rolled. Most rolled biscuit recipes call for cold butter cut into dry ingredients with a pastry blender, two knives, or sometimes a food processor, after which the dough is rolled and cut. The dropped biscuits looked more promising (translation: easier)—mix the dry ingredients, mix the wet ingredients, mix the two together, and drop (over fruit). Sounded good to me!

To be sure that my tasters agreed, I made two cobblers, one with rolled and one with dropped biscuits. The dropped biscuits, light and rustic in appearance, received the positive comments I was looking for but needed some work. To start, I had to fine-tune the ingredients, which included flour, sugar, leavener, milk, eggs, butter/shortening, and flavorings. I immediately eliminated eggs from the list because they made the biscuits a tad heavy. As for dairy, heavy cream was too rich, whereas milk and half-and-half lacked depth of flavor. I finally tested buttermilk, which delivered a much-needed flavor boost as well as a lighter, fluffier texture. As for the choice of fat, butter was in and Crisco was out—butter tasted much better. Next I wanted to test melted butter versus cold butter. Although I had been using melted butter in the dropped biscuits, I wondered if cold butter would yield better results, as some sources suggested. I melted butter for one batch and cut cold butter into the dry ingredients (with a food processor) for another. The difference was nil, so melting, the easier method, was the winner.

I soon discovered that the big problem with drop biscuits is getting them to cook through. (The batter is wetter than rolled biscuit dough and therefore has a propensity for remaining doughy.) No matter how long I left the biscuits on the berry topping in a 400-degree oven, they never baked through, turning browner and browner on top while remaining doughy on the bottom. I realized that what the biscuits needed might be a blast of heat from below—that is, from the berries. I tried baking the berries alone in a moderate 375-degree oven for 25 minutes and then dropped and baked the biscuit dough on top. Bingo! The heat from the bubbling berries helped to cook the biscuits from underneath, while the dry heat of the oven cooked the biscuits from above.

There was one final detail to perfect. I wanted the biscuits to be more crisp on the outside and to have a deeper hue. This was easily achieved by bumping the oven to 425 degrees when I added the biscuits. A sprinkling of cinnamon sugar on the dropped biscuit dough added just a bit more crunch.

SERVES 6 TO 8

While the blueberries are baking, prepare the ingredients for the topping, but do not stir the wet ingredients into the dry ingredients until just before the berries come out of the oven. A standard or deep-dish 9-inch pie plate works well for this recipe; however, an 8-inch square baking dish can also be used. Serve with vanilla ice cream or whipped cream. To reheat leftovers, put the cobbler in a 350-degree oven for 10 to 15 minutes, until heated through.

Filling

½ cup (3½ ounces) sugar

1 tablespoon cornstarch

Pinch ground cinnamon

Pinch salt

30 ounces (6 cups) blueberries

1½ teaspoons grated lemon zest plus 1 tablespoon juice

Biscuit Topping

1 cup (5 ounces) all-purpose flour

¼ cup (1¾ ounces) sugar, plus 2 teaspoons for sprinkling

2 tablespoons stone-ground cornmeal

2 teaspoons baking powder

¼ teaspoon baking soda

¼ teaspoon salt

⅓ cup buttermilk

4 tablespoons unsalted butter, melted

½ teaspoon vanilla extract

⅛ teaspoon ground cinnamon

1. For the filling: Adjust oven rack to lower-middle position and heat oven to 375 degrees. Line rimmed baking sheet with aluminum foil. Whisk sugar, cornstarch, cinnamon, and salt together in large bowl. Add blueberries and mix gently until evenly coated; add lemon zest and juice and mix until combined. Transfer mixture to 9-inch pie plate, place plate on prepared sheet, and bake until filling is bubbling around edges, about 25 minutes.

2. For the biscuit topping: Meanwhile, whisk flour, ¼ cup sugar, cornmeal, baking powder, baking soda, and salt together in large bowl. Whisk buttermilk, melted butter, and vanilla together in small bowl. Combine cinnamon and remaining 2 teaspoons sugar in small bowl and set aside. One minute before blueberries come out of oven, add buttermilk mixture to flour mixture; stir until just combined and no dry pockets remain.

3. After removing blueberries from oven, increase oven temperature to 425 degrees. Divide dough into 8 equal pieces and place them on hot filling, spacing them at least ½ inch apart (they should not touch). Sprinkle dough mounds evenly with cinnamon sugar. Bake until filling is bubbling and biscuits are golden brown on top and cooked through, 15 to 18 minutes, rotating pie plate halfway through baking. Let cool on wire rack for 20 minutes; serve warm.

variations

Blueberry Cobbler with Gingered Biscuits

Add 3 tablespoons minced crystallized ginger to flour mixture and substitute ⅛ teaspoon ground ginger for cinnamon in sugar for sprinkling on biscuits.

Thaw 30 ounces frozen blueberries in colander set over bowl to catch juice. Transfer juice (you should have about 1 cup) to small saucepan; simmer over medium heat until syrupy and thick enough to coat back of spoon, about 10 minutes. Mix syrup with blueberries and other filling ingredients; increase baking time for filling to 30 minutes and increase baking time in step 3 to 20 to 22 minutes.

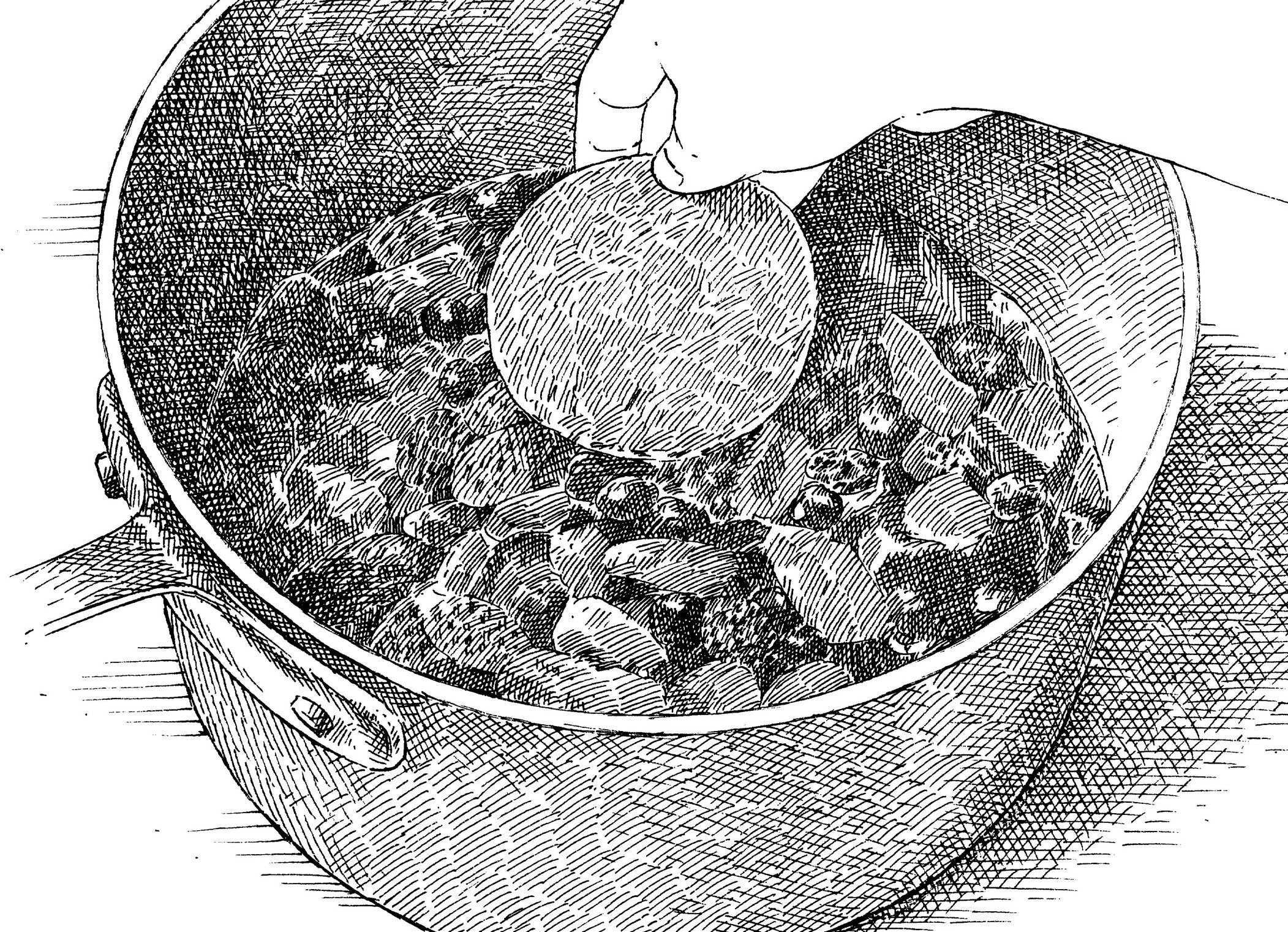

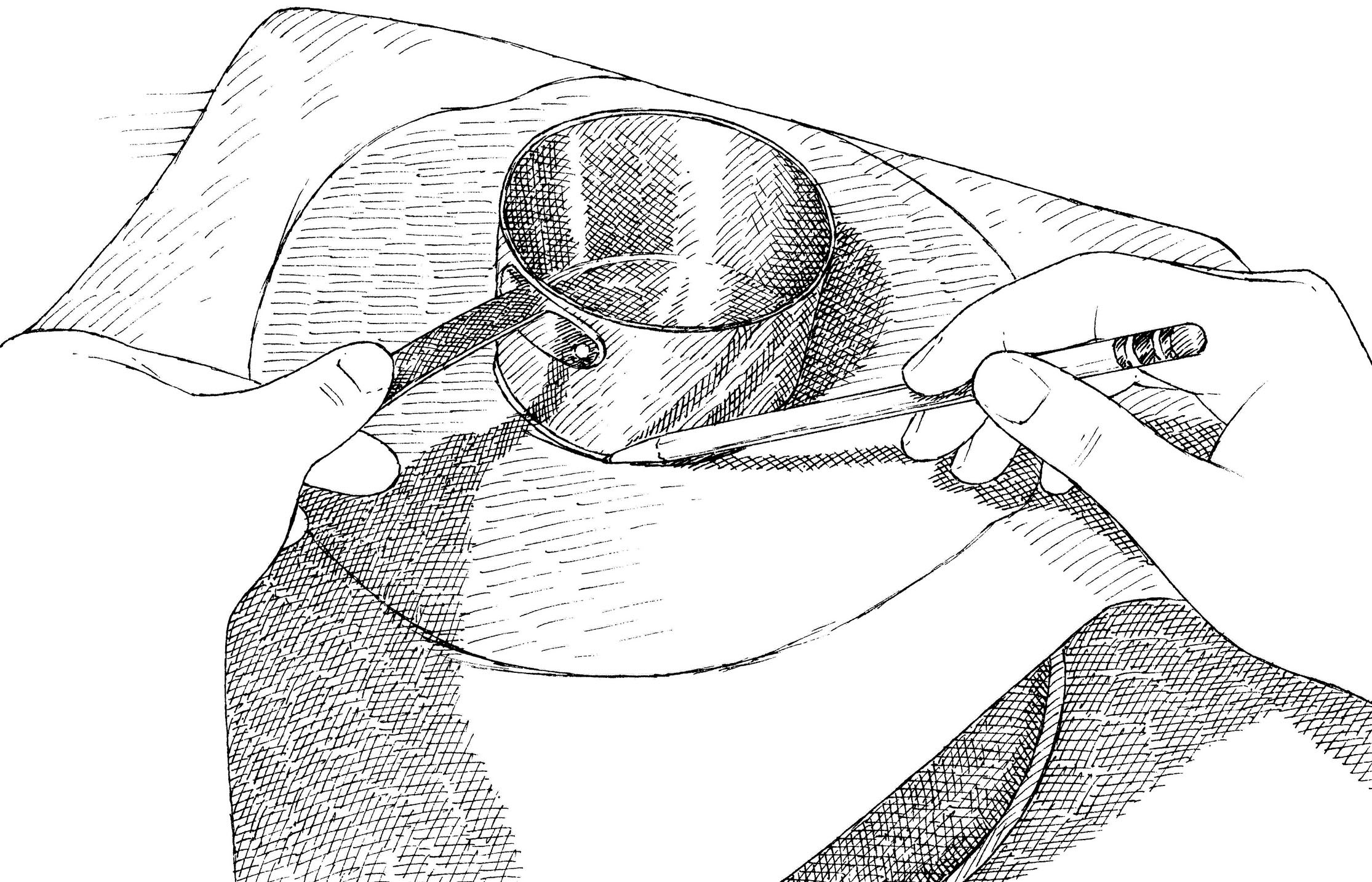

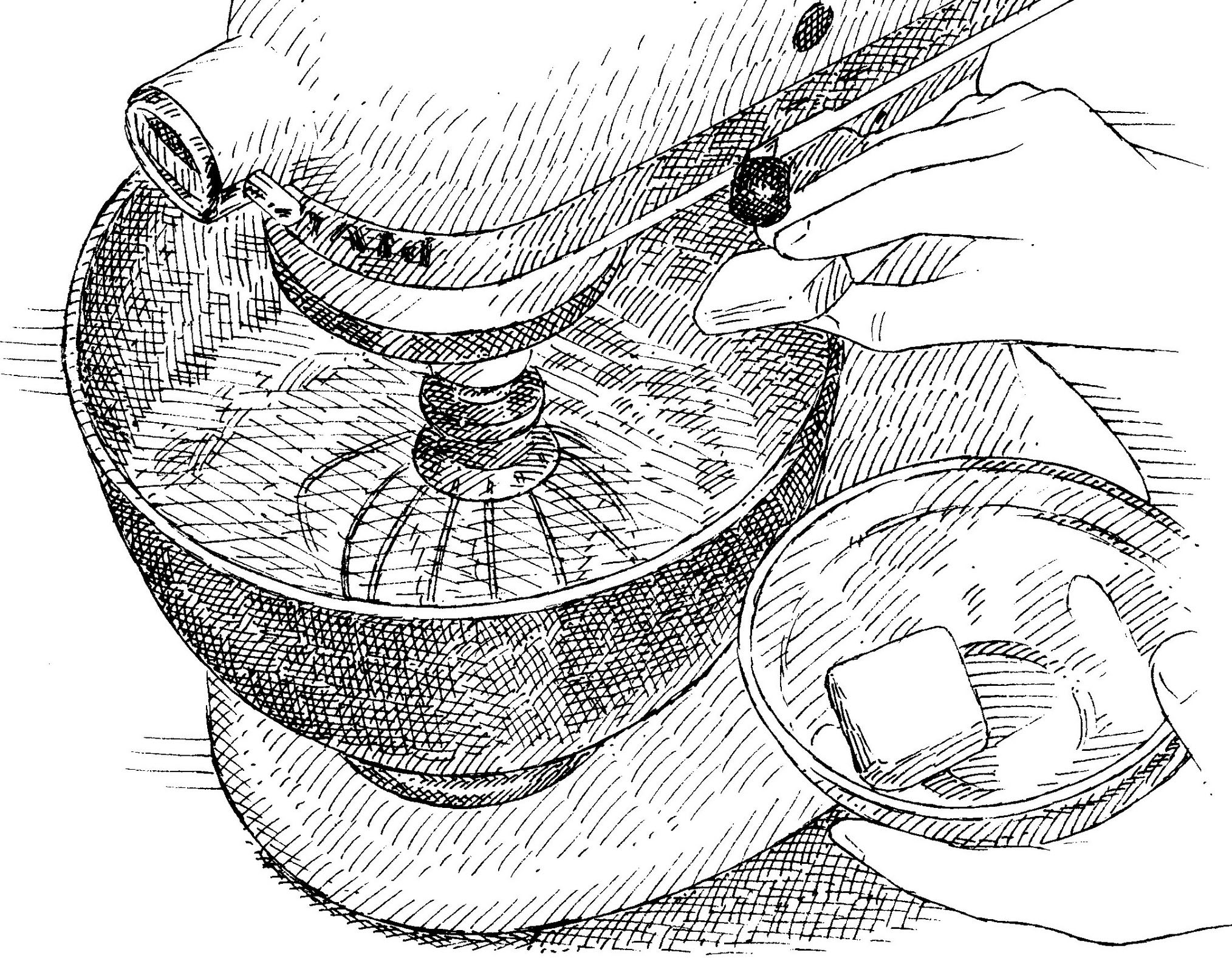

GETTING EVENLY BAKED BISCUITS

Dropping the biscuits onto a hot filling heats them from the bottom, ensuring they cook through.

1. While berries bake, whisk dry ingredients in large bowl. Whisk together wet ingredients in separate small bowl. One minute before berries come out of oven, add buttermilk mixture to flour mixture and stir until just combined.

2. Take berries out of oven and increase temperature to 425 degrees. Divide dough into 8 pieces and drop onto hot filling, spacing biscuits at least ½ inch apart (they should not touch). Sprinkle with cinnamon sugar.

3. Bake until filling is bubbling and biscuits are golden brown and cooked through, 15 to 18 minutes.

If any food speaks of the summer, summer pudding does. Ripe, fragrant, lightly sweetened berries are gently cooked to coax out their juices, which then soak and soften slices of bread to make them meld with the fruit. Served chilled, summer pudding is incredibly fresh and refreshing. Last summer, I came home from a farmer’s market with half a flat of strawberries that I’d purchased for a dollar. Not enough to preserve, I thought, but a great chance to make a summer pudding. With some raspberries, blueberries, and old bread from the freezer, I easily threw one together. I was pleased with this first attempt, but the pudding was a bit too sweet for me, and the bread seemed to stand apart from the fruit, as if it were just a casing. Improving upon it, I knew, would be an easy task. I wanted sweet-tart berries and bread that melded right into them.

In a typical summer pudding, berries fill a bowl or mold of some sort that has been neatly lined with crustless bread. Well, trimming the crusts is easy, but trimming the bread to fit the mold and lining the bowl with it is fussy. After having made a couple of puddings, I quickly grew tired of this technique—it seemed to undermine the simplicity of the dessert. I came across a couple of recipes that called for layering the bread right in with the berries instead of using it to line the bowl. Not only is this bread-on-the-inside method easier, but a summer pudding made in this fashion looks spectacular—the berries on the outside are like brilliant jewels. Meanwhile, the layers of bread on the inside almost melt into the fruit.

My next adjustment to this recipe was losing the bowl as a mold. I switched instead to making individual summer puddings in ramekins. I found them to be hardly more labor-intensive in assembly than a single large pudding. Sure, you have to cut out rounds of bread to fit the ramekins, but a cookie cutter makes easy work of it, and individual servings transform this humble dessert into an elegant one. The individual puddings are also easily served—simply unmold one onto a plate, no slicing or scooping involved. I also found I could use a loaf pan to make a single large pudding; its rectangular shape requires less trimming of bread slices.

With the form set, I moved on to the ingredients. For the 4 pints of berries I was using, ¾ cup of sugar was a good amount. Lemon juice, I found, perked up the berry flavors and rounded them out. I then sought alternatives to cooking the fruit in an attempt to preserve its freshness. I mashed first some and then all of the berries with sugar. I tried cooking only a portion of the fruit with sugar. I macerated the berries with sugar. None of these methods worked. These puddings, even after being weighted and chilled overnight, had an unwelcome crunchy, raw quality. The berries need a gentle cooking to make their texture more yielding, more pudding-like, if you will. But don’t worry—5 minutes is all it takes, not even long enough to heat up the kitchen.

Next I investigated the bread. I tried six different kinds as well as pound cake (for which I was secretly rooting). Hearty, coarse-textured sandwich bread and a rustic French loaf were too tough and tasted fermented and yeasty. Very soft, pillowy sandwich bread became soggy and lifeless when soaked with juice. The pound cake, imbued with berry juice, turned into wet sand and had the textural appeal of sawdust. A good-quality white sandwich bread with a bit of heft was good, but there were two very clear winners: challah and potato bread. Their even, tight-crumbed, tender texture and light sweetness were a perfect match for the berries.

Most summer pudding recipes call for stale bread. And for good reason. Fresh bread, I found, when soaked with those berry juices, turns to mush. You might not think this would be so noticeable with the bread layered between all those berries, but every single taster remarked that the pudding made with fresh bread was soggy and gummy. On the other hand, stale bread absorbs some of the juices and melds with the berries yet still maintains some structural integrity. Rather than waiting for bread to stale, however, I simply baked the slices in the oven at a very low temperature until they were dry to the touch but still somewhat pliable.

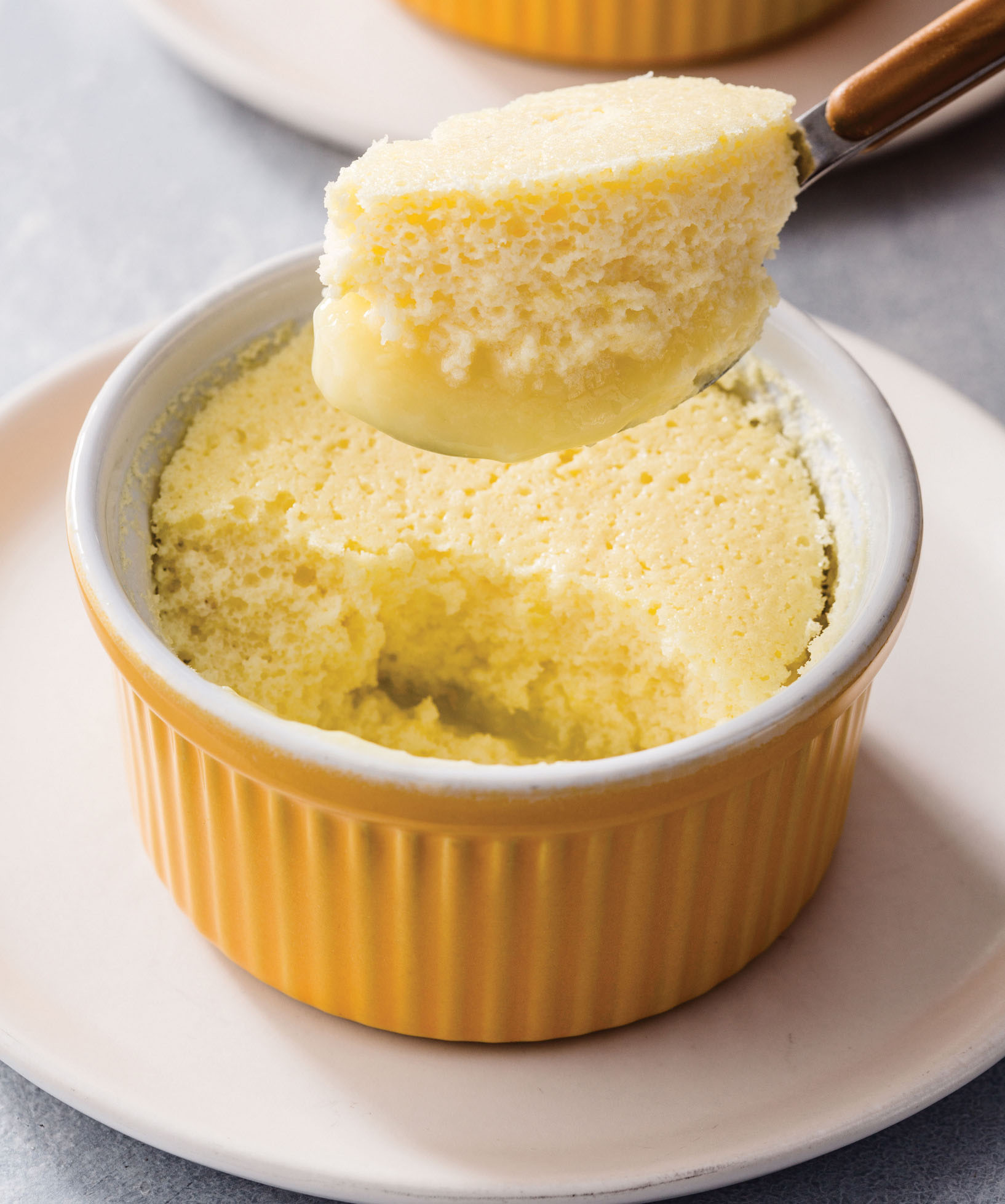

Cooking the berries for just 5 minutes and then layering them with dried slices of potato bread makes for an elegant and bright dessert.

Probably the oddest thing about summer pudding is the fact that it is weighted as it chills. What, I wondered, does this do for the texture? And how long does the pudding need to chill? I made several batches and chilled them with and without weights for 4, 8, 24, and 30 hours. The puddings chilled for 4 hours tasted of underripe fruit. The bread was barely soaked through, and the berries barely clung together. At 8 hours the puddings were at their peak: the berries tasted fresh and held together, while the bread melted right into them. Twenty-four hours and the puddings were still good, though a hairsbreadth duller in color and flavor. After 30 hours the puddings were well past their prime and began to smell and taste fermented.

No matter how long they chilled, the summer puddings without weights were loose—they didn’t hold together after unmolding. The fruit was less cohesive and the puddings less pleasurable to eat.

No pound cake, no butter. Just bright, fresh summer berries made into the perfect summer dessert. Topped with a healthy dollop of whipped cream, what could be better?

Individual Summer Berry Puddings

SERVES 6

For this recipe, you will need six 6-ounce ramekins and a round cookie cutter of slightly smaller diameter than the ramekins. If you don’t have the right-size cutter, use a paring knife and the bottom of a ramekin (most ramekins taper toward the bottom) as a guide for trimming the rounds. Top with whipped cream, if desired.

12 slices potato bread, challah, or hearty white sandwich bread

1¼ pounds strawberries, hulled and sliced (4 cups)

10 ounces (2 cups) raspberries

5 ounces (1 cup) blackberries

5 ounces (1 cup) blueberries

¾ cup (5¼ ounces) sugar

2 tablespoons lemon juice

1. Adjust oven rack to middle position and heat oven to 200 degrees. Place bread in single layer on rimmed baking sheet and bake until dry but not brittle, about 1 hour, flipping slices once and rotating sheet halfway through baking. Set aside to cool.

2. Combine strawberries, raspberries, blackberries, blueberries, and sugar in large saucepan and cook over medium heat, stirring occasionally, until berries begin to release their juices and sugar has dissolved, about 5 minutes. Off heat, stir in lemon juice; let cool to room temperature.

3. Spray six 6-ounce ramekins with vegetable oil spray and place on rimmed baking sheet. Use cookie cutter to cut out 12 bread rounds that are slightly smaller in diameter than ramekins.

4. Using slotted spoon, place ¼ cup fruit mixture in each ramekin. Lightly soak 1 bread round in fruit juice in saucepan and place on top of fruit in ramekin; repeat with 5 more bread rounds and remaining ramekins. Divide remaining fruit among ramekins, about ½ cup per ramekin. Lightly soak 1 bread round in fruit juice and place on top of fruit in ramekin (it should sit above lip of ramekin); repeat with remaining 5 bread rounds and remaining ramekins. Pour remaining fruit juice over bread and cover ramekins loosely with plastic wrap. Place second baking sheet on top of ramekins and weight with heavy cans. Refrigerate puddings for at least 8 hours or up to 24 hours.

5. Remove cans and baking sheet and uncover puddings. Loosen puddings by running paring knife around edge of each ramekin, unmold into individual bowls, and serve immediately.

variation

SERVES 6 TO 8

Because there is no need to cut out rounds for this version, you will need only about eight slices of bread, depending on their size.

Trim crusts from toasted bread and trim slices to fit in single layer in loaf pan (you will need about 2½ slices per layer; there will be three layers). Spray 9 by 5-inch loaf pan with vegetable oil spray, line with plastic wrap, and place on rimmed baking sheet. Using slotted spoon, spread about 2 cups fruit mixture evenly over bottom of prepared pan. Lightly soak enough bread slices for 1 layer in fruit juice in saucepan and place on top of fruit. Repeat with 2 more layers of fruit and bread. Pour remaining fruit juice over bread and cover loosely with plastic wrap. Place second baking sheet on top of loaf pan and weight it with heavy cans. Refrigerate pudding as directed. When ready to serve, invert pudding onto serving platter, remove loaf pan and plastic, slice, and serve.

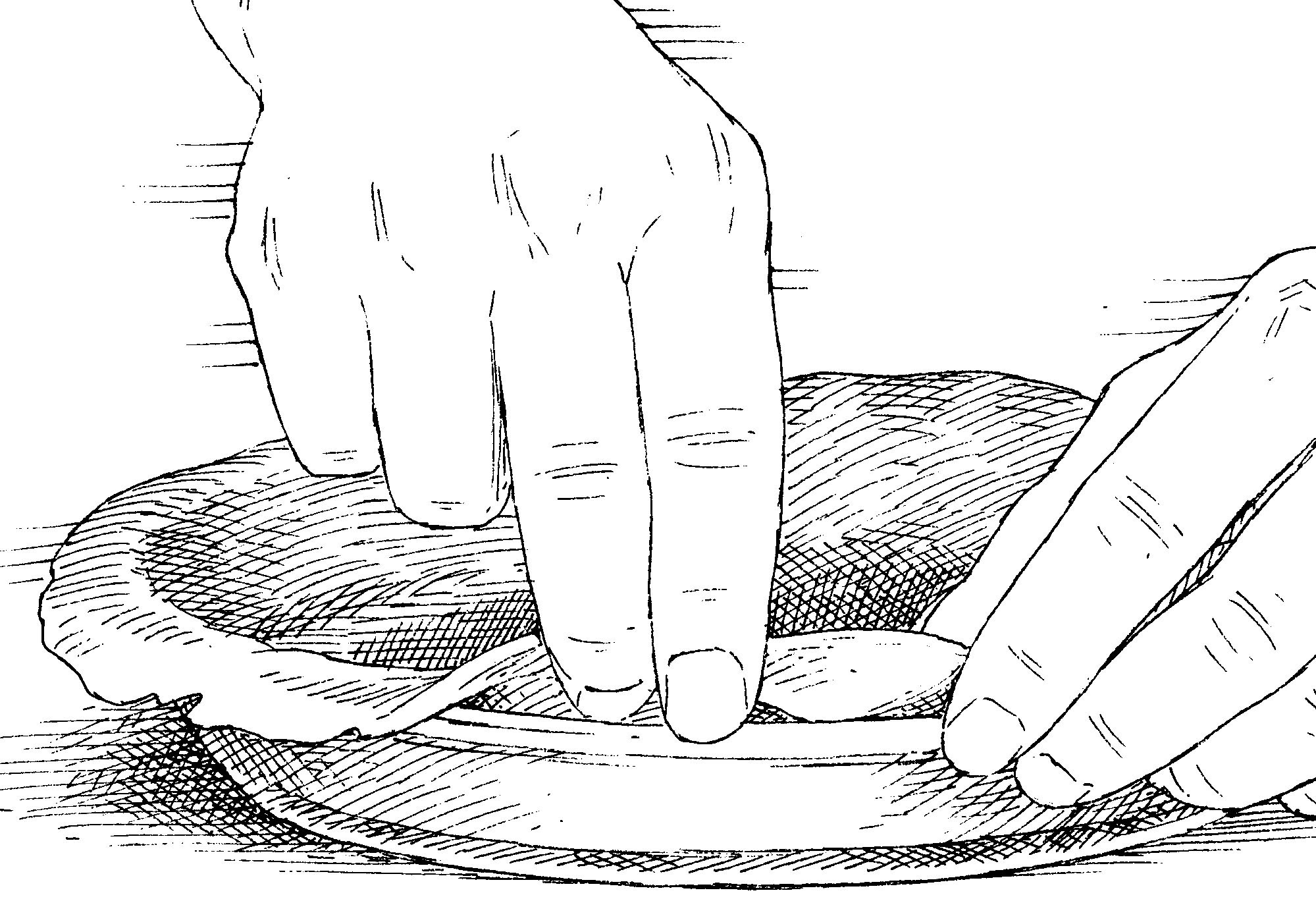

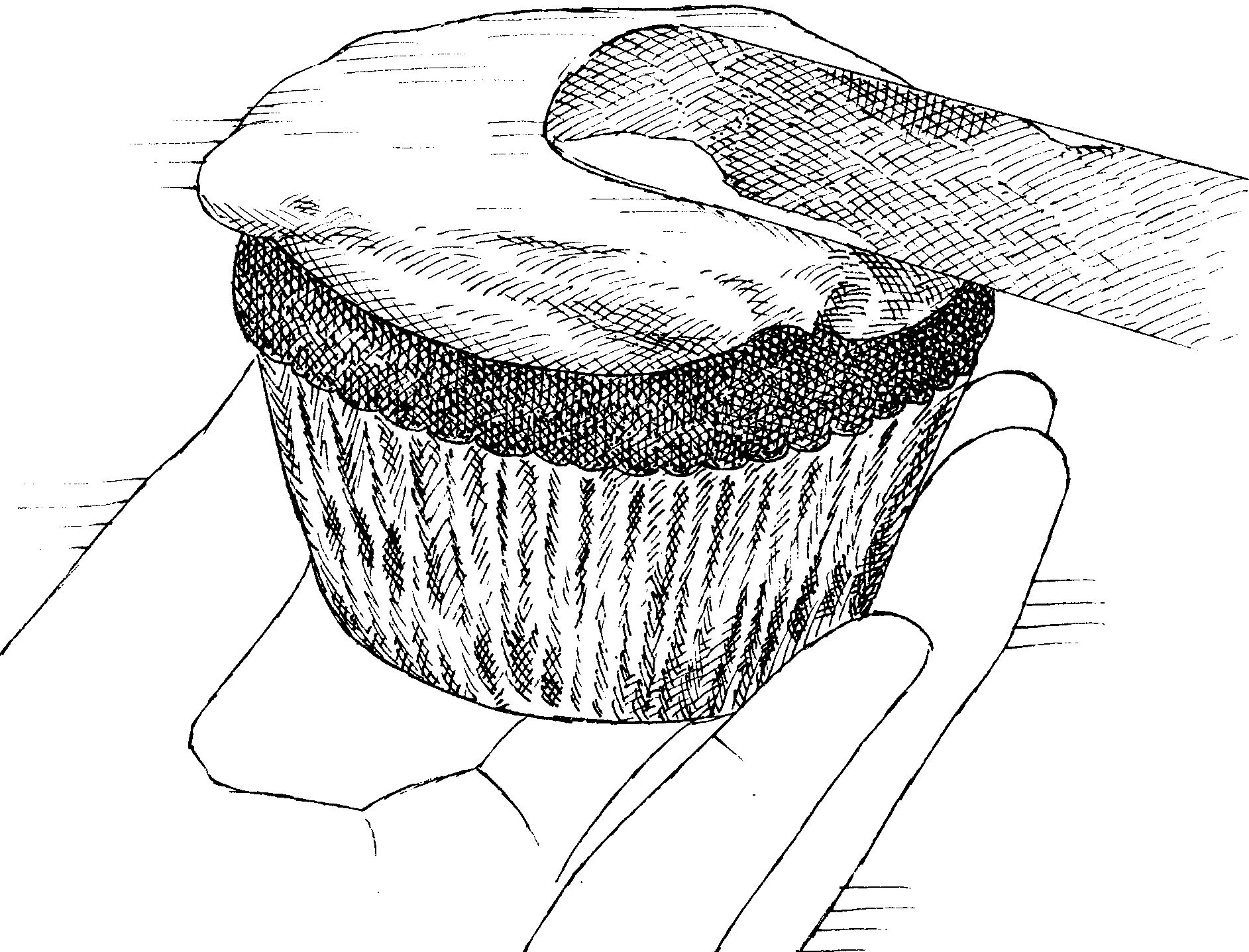

ASSEMBLING INDIVIDUAL SUMMER BERRY PUDDINGS

1. Cut out rounds of bread with cookie cutter.

2. Use slotted spoon to place about ¼-cup portions of fruit into greased 6-ounce ramekins.

3. Lightly soak rounds of bread in berry juice and layer with fruit in each ramekin. Repeat layering with remaining fruit and bread rounds.

4. Cover filled ramekins with plastic wrap. Place cookie sheet on top, then weight with several heavy cans.

A fresh fruit tart is the showpiece of a bakery pastry case. With its clean crust edge and ornate arrangement of fruit glistening with glaze, this dessert is beautiful and conveys a sense of occasion. But anyone who has served one knows that the pretty presentation falls apart when the knife meets the tart. Instead of neat wedges, you get shards of pastry oozing messy fruit and juice-stained filling. That’s a disappointing end for a dessert that started out so impressive and required several hours to make.

I set out to reconceptualize the classic fresh fruit tart from crust to crown. I wanted the crust and filling to be sturdy and stable enough to retain their form when cut, and I wanted to streamline their preparation. That might mean departing from tradition, but as long as the tart looked pretty and featured a buttery crust complementing a satiny filling and bright, sweet, juicy fruit, I was ready for new ideas.

CRUST EASE

Plenty of published recipes touted innovative approaches to the fresh fruit tart, starting with the crust. The most promising one traded the traditional pâte sucrée—in which cold butter is worked into flour and sugar, chilled, and rolled out—for a simpler pat-in-the-pan crust. This style of crust calls for simply melting the butter and stirring it into the flour mixture to create a pliable dough that is easily pressed into the pan and baked. I tried one such recipe: While the result was crisp and cookie-like rather than flaky, it still made a nice contrast to the creamy filling.

I had one tweak in mind: Since I would be melting the butter anyway, I’d try browning it to give the pastry a richer, nuttier character. But because browning the butter cooked off its water, this produced a sandy, cracked crust. There wasn’t enough moisture for the proteins in the flour to form the gluten necessary to hold the crust together. Adding a couple of tablespoons of water to the browned butter before mixing it with the dry ingredients fixed the problem: The dough was more cohesive and, after 30 minutes in a 350-degree oven, formed a crust that held together.

On to the filling. I wasn’t keen on the traditional pastry cream: It’s fussy to make and tends to ooze from the crust when sliced. What I needed was something that was thick and creamy from the get-go. Mascarpone, the creamy, tangy-sweet fresh cheese that’s the star of tiramisù and many other Italian desserts, seemed like a good option. Sweetened with a little sugar and spread over the tart shell, it was a workable starting point, but it still wasn’t dense enough to hold its shape when sliced. Thickeners such as gelatin, pectin, and cornstarch required either cooking or hydrating in liquid to be effective, as well as several hours to set up. A colleague had a better idea: white chocolate. I could melt it in the microwave and stir it into the mascarpone. Since white chocolate is solid at room temperature, it would firm up the filling as it cooled.

I melted white baking chips (they resulted in a firmer texture than white chocolate, which contains cocoa butter) in the microwave, adding ¼ cup of heavy cream so the mixture would blend smoothly into the cheese. When the filling was homogeneous, I smoothed it into the cooled crust, gently pressed in the fruit while the filling was still slightly warm (once cooled completely it would be too firm to hold the fruit neatly), brushed on a jam glaze, and refrigerated the tart for 30 minutes so the filling would set. I then allowed the tart to sit at room temperature for 15 minutes before slicing it.

The filling was satiny and, thanks to the baking chips, nicely firm. To give it a little more oomph, I added bright, fruity lime juice, which—despite being a liquid—wouldn’t loosen the filling. Instead, the acid would act on the cream’s proteins, causing them to thicken; meanwhile, the cream’s fat would prevent any graininess.

Since heating the lime juice would drive off its bright flavor, I stirred it in with the mascarpone; it paired beautifully with the rich cheese and white chocolate. For even more lime flavor, I added a teaspoon of zest, heating it with the chocolate and cream to draw out its flavor-packed oils.

For neat slicing and serving, we use mascarpone and white baking chips in the filling and arrange the fruit in wedges.

EDIBLE ARRANGEMENTS

I decided to top the tart with an appealing, summery combo of berries and ripe peaches, peeled and cut into thin slices. But before I placed the fruit on the filling, I thought carefully about how to arrange it. Many tarts feature fruit organized in concentric circles. These look great when whole, but since you have to cut through the fruit when slicing, it winds up mangled. Why not arrange the fruit so that the knife could slip between pieces?

First, I spaced eight berries around the outer edge of the tart, which I then used as guides to help me evenly arrange eight sets of three slightly overlapping peach slices so that they radiated from the center of the tart to its outer edge. The peach slices would serve as cutting guides for eight wedges. Next, I artfully arranged a mix of berries on each wedge. The final touch: I made a quick glaze using apricot preserves that I thinned with lime juice for easy dabbing.

The crisp, sturdy, rich crust; satiny yet stable filling; and bright-tasting fruit added up to a classic showpiece with modern flavor. Best of all, it was quick to make, and each slice looked just as polished and professional as the whole tart.

Fresh Fruit Tart

SERVES 8

This recipe calls for extra berries to account for any bruising. Ripe, unpeeled nectarines can be substituted for the peaches, if desired. Use white baking chips here and not white chocolate bars, which contain cocoa butter and will result in a loose filling. Use a light hand when dabbing on the glaze; too much force will dislodge the fruit. If the glaze begins to solidify while dabbing, microwave it for 5 to 10 seconds.

Crust

1⅓ cups (6⅔ ounces) all-purpose flour

¼ cup (1¾ ounces) sugar

⅛ teaspoon salt

10 tablespoons unsalted butter

2 tablespoons water

Tart

⅓ cup (2 ounces) white baking chips

¼ cup heavy cream

1 teaspoon grated lime zest plus 7 teaspoons juice (2 limes)

Pinch salt

6 ounces (¾ cup) mascarpone cheese, room temperature

2 ripe peaches, peeled

20 ounces (4 cups) raspberries, blackberries, and blueberries

⅓ cup apricot preserves

1. For the crust: Adjust oven rack to middle position and heat oven to 350 degrees. Whisk flour, sugar, and salt together in bowl. Melt butter in small saucepan over medium-high heat, swirling saucepan occasionally, until foaming subsides. Cook, stirring and scraping bottom of saucepan with heatproof spatula, until milk solids are dark golden brown and butter has nutty aroma, 1 to 3 minutes. Remove saucepan from heat and add water. When bubbling subsides, transfer butter to bowl with flour mixture and stir until well combined. Transfer dough to 9-inch tart pan with removable bottom and let dough rest until just warm, about 10 minutes.

2. Use your hands to evenly press and smooth dough over bottom and up side of pan (using two-thirds of dough for bottom crust and remaining third for side). Place pan on wire rack set in rimmed baking sheet and bake until crust is golden brown, 25 to 30 minutes, rotating pan halfway through baking. Let crust cool completely, about 1 hour. (Cooled crust can be wrapped loosely in plastic wrap and stored at room temperature for up to 24 hours.)

3. For the tart: Microwave baking chips, cream, lime zest, and salt in medium bowl, stirring every 10 seconds, until baking chips are melted, 30 to 60 seconds. Whisk in one-third of mascarpone, then whisk in 6 teaspoons lime juice and remaining mascarpone until smooth. Transfer filling to tart shell and spread into even layer.

4. Place peach, stem side down, on cutting board. Placing knife just to side of pit, cut down to remove 1 side of peach. Turn peach 180 degrees and cut off opposite side. Cut off remaining 2 sides. Place pieces cut side down and slice ¼ inch thick. Repeat with second peach. Select best 24 slices.

5. Evenly space 8 berries around outer edge of tart. Using berries as guide, arrange 8 sets of 3 peach slices in filling, slightly overlapping slices with rounded sides up, starting at center and ending on right side of each berry. Arrange remaining berries in attractive pattern between peach slices, covering as much of filling as possible and keeping fruit in even layer.

6. Microwave preserves and remaining 1 teaspoon lime juice in small bowl until fluid, 20 to 30 seconds. Strain mixture through fine-mesh strainer. Using pastry brush, gently dab mixture over fruit, avoiding crust. Refrigerate tart for 30 minutes.

7. Remove outer metal ring of tart pan. Slide thin metal spatula between tart and pan bottom to loosen tart, then carefully slide tart onto serving platter. Let tart sit at room temperature for 15 minutes. Using peaches as guide, cut tart into wedges and serve. (Tart can be refrigerated for up to 24 hours. If refrigerated for more than 1 hour, let tart sit at room temperature for 1 hour before serving.)

MAKE AN EDIBLE SLICING GUIDE

Strategically arranging the fruit isn’t all about looks. It can make it easier to cut clean slices, too.

1. Evenly arrange 8 berries around outer edge of tart.

2. Arrange 8 sets of 3 overlapping peach slices from center to edge of tart on right side of each berry.

3. Arrange remaining berries in attractive pattern between peach slices in even layer to cover filling.

Classic and elegant, a traditional French tarte aux pommes is a visually stunning dessert that has intense fruit flavor and varied textures, yet is made with just a few basic ingredients. In its simplest form, this tart consists of crisp pastry shell that’s filled with a concentrated apple puree and then topped with a spiraling fan of paper-thin apple slices. It’s usually finished with a delicate glaze that caramelizes during baking, providing an extra layer of flavor.

But poor structure is the fatal flaw of many a handsome apple tart; overly tough apple slices and mushy crusts abound. Plus, the dessert’s overall flavor can be a bit one-dimensional. Still, I was drawn to this showstopper dessert that could be made with a short list of pantry staples. My challenge would be perfecting each component to produce a gorgeous tart with lively, intense apple flavor and a crust that stayed crisp.

For an apple tart with both integrity and beauty, we use melted rather than chilled butter in the crust and parcook the apples for the topping.

A STRONG FOUNDATION

For a dough that would hold its shape and maintain a crisp texture even after being filled with the puree, I started by preparing the three classic French pastry options and filling them with a placeholder puree: five peeled and cored Golden Delicious apples (widely available, and good quality year round) cooked with a splash of water until soft, mashed with a potato masher, and reduced until thick.

My first attempt was with frozen puff pastry, which I rolled thin and parbaked to dry it out and firm it up. But the dough shrank, and its texture softened beneath the wet puree. On to the next.

Following a classic recipe for pâte brisée (essentially the French equivalent of flaky American pie dough), I used the food processor to pulse cold butter into flour until the mixture formed a coarse meal. I drizzled in a little water, then chilled the dough, rolled it out, fit it into the tart pan, chilled it again, lined the dough with parchment, weighed it down with pie weights, parbaked it, removed the parchment and weights, and baked it until it was crisp. All that work is supposed to keep the dough from shrinking—and this shell did hold its shape nicely. But the puree still turned the pastry soggy.

Lastly, I tried a pâte sucrée. This pastry typically contains more sugar than the previous doughs, but the most significant difference is that the butter is thoroughly worked into the flour, which limits the development of gluten—the strong elastic network that forms when flour proteins are moistened with water. Less gluten translates to pastry that is less prone to shrinking and that bakes up with a finer, shorter crumb.

I worked the butter into the dry ingredients until the mixture looked like sand, then bound it with an egg (typical in pâte sucrée recipes). I chilled, rolled, chilled, and baked as before—but I skipped the pie weights, since the dough wasn’t likely to shrink.

Indeed, this crust baked up plenty sturdy, and it didn’t sog out when I filled it with the puree. But it puffed slightly during baking, and frankly, all that chilling and rolling was tiresome. There had to be an easier way.

CRUNCH TIME

Eliminating the egg would mitigate the cookie-like lift, but without the egg’s moisture, I would need another liquid component to bind the dry ingredients with the cold butter. I didn’t want to add water, since that would encourage gluten development. But what if I turned the butter (which contains very little water) into a liquid by melting it?

Stirring melted butter into the dry ingredients produced a promisingly cohesive dough that was so malleable, I didn’t need to roll it—I could simply press it into the pan. Then I chilled it and baked it.

This was by far the easiest pastry I’d ever made. The crust baked up perfectly sturdy and was no longer puffed, but crisp and delicate like shortbread—and stayed that way even when filled with the puree. Subsequent streamlining tests showed that I didn’t even have to chill this modified pâte sucrée before baking; the sides of the tart pan were shallow enough that the pastry didn’t slump. Now to improve that placeholder puree.

AMPING UP APPLESAUCE

My apple filling had to have concentrated fruit flavor and enough body to hold its shape on a fork. The latter goal I’d almost met by cooking down the puree until it had a texture and flavor somewhere between applesauce and apple butter. Moving this operation from a saucepan to a wider covered skillet helped water from the fruit evaporate faster.

For more distinctive flavor, I took a cue from Julia Child’s recipe for tarte aux pommes, in which she adds butter and apricot preserves to her puree. Tasters applauded this richer, brighter-tasting filling. The preserves also contributed pectin, which helped the filling firm up even more.

TOPPING IT OFF

Finally, I needed to find a way to simplify the shingling of the apples on top—a painstaking task, especially when trying to brush the delicately placed apples with a shiny glaze. (Luckily, the glaze itself was simple: I just brushed the top with the brightly flavored apricot preserves I was already using in the filling.) To add to my frustrations, the apple slices never became tender enough for me to cut the tart without their resisting and becoming dislodged. I tried baking the tart longer, brushing the slices with water or melted butter, and covering the tart with foil for part of the baking time so the slices might soften in the trapped steam—none of which worked.

In the end, I swapped the wafer-thin apple slices for more generous slices and sautéed them for 10 minutes to jump-start the softening before placing them on the tart. As for the spiral shingling, I decided to forgo this fussy tradition and came up with a more easygoing, but still sophisticated, rosette pattern made by placing the apple slices in concentric circles. The parcooking had made the slices conveniently pliable, so there was no awkwardness toward the center of the arrangement; I simply bent the pieces and slipped them into place.

Once the tart was baked, I applied the glaze. Encouragingly, these sturdier pieces stayed put when I brushed them with the strained jam. Then I briefly ran the tart under the broiler to get the burnished finish that characterizes this French showpiece.

The rosette design made this tart look a bit different from classic French versions, but it was every bit as elegant. And thanks to the now-tender glazed apple slices, the rich puree, and the crisp—not to mention utterly simple and foolproof—crust, every slice of the tart that I cut was picture-perfect.

French Apple Tart

SERVES 8

You may have extra apple slices after arranging the apples in step 6. If you don’t have a potato masher, you can puree the apples in a food processor. For the best flavor and texture, be sure to bake the crust thoroughly until it is deep golden brown. To ensure that the outer ring of the pan releases easily from the tart, avoid getting apple puree and apricot glaze on the crust. The tart is best served the day it is assembled, but the baked crust, apple slices, and apple puree can be made up to 24 hours in advance. Apple slices and apple puree should be refrigerated separately in airtight containers. Assemble tart with refrigerated apple slices and puree and bake as directed, adding 5 minutes to baking time.

Crust

1⅓ cups (6⅔ ounces) all-purpose flour

5 tablespoons (2¼ ounces) sugar

½ teaspoon salt

10 tablespoons unsalted butter, melted

Filling

10 Golden Delicious apples (8 ounces each), peeled and cored

3 tablespoons unsalted butter

1 tablespoon water

½ cup apricot preserves

¼ teaspoon salt

1. For the crust: Adjust 1 oven rack to lowest position and second rack 5 to 6 inches from broiler element. Heat oven to 350 degrees. Whisk flour, sugar, and salt together in bowl. Add melted butter and stir with wooden spoon until dough forms. Using your hands, press two-thirds of dough into bottom of 9-inch tart pan with removable bottom. Press remaining dough into fluted sides of pan. Press and smooth dough with your hands to even thickness. Place pan on wire rack set in rimmed baking sheet and bake on lowest rack, until crust is deep golden brown and firm to touch, 30 to 35 minutes, rotating pan halfway through baking. Set aside until ready to fill.

2. For the filling: Cut 5 apples lengthwise into quarters and cut each quarter lengthwise into 4 slices. Melt 1 tablespoon butter in 12-inch skillet over medium heat. Add apple slices and water and toss to combine. Cover and cook, stirring occasionally, until apples begin to turn translucent and are slightly pliable, 3 to 5 minutes. Transfer apples to large plate, spread into single layer, and set aside to cool. Do not clean skillet.

3. While apples cook, microwave apricot preserves until fluid, about 30 seconds. Strain preserves through fine-mesh strainer into small bowl, reserving solids. Set aside 3 tablespoons strained preserves for brushing tart.

4. Cut remaining 5 apples into ½-inch-thick wedges. Melt remaining 2 tablespoons butter in now-empty skillet over medium heat. Add remaining apricot preserves, reserved apricot solids, apple wedges, and salt. Cover and cook, stirring occasionally, until apples are very soft, about 10 minutes.

5. Mash apples to puree with potato masher. Continue to cook, stirring occasionally, until puree is reduced to 2 cups, about 5 minutes.

6. Transfer apple puree to baked tart shell and smooth surface. Select 5 thinnest slices of sautéed apple and set aside. Starting at outer edge of tart, arrange remaining slices, tightly overlapping, in concentric circles. Bend reserved slices to fit in center. Bake tart, still on wire rack in sheet, on lowest rack, for 30 minutes. Remove tart from oven and heat broiler.

7. While broiler heats, warm reserved preserves in microwave until fluid, about 20 seconds. Brush evenly over surface of apples, avoiding tart crust. Broil tart, checking every 30 seconds and turning as necessary, until apples are attractively caramelized, 1 to 3 minutes. Let tart cool for at least 1½ hours. Remove outer metal ring of tart pan, slide thin metal spatula between tart and pan bottom, and carefully slide tart onto serving platter. Cut into wedges and serve.

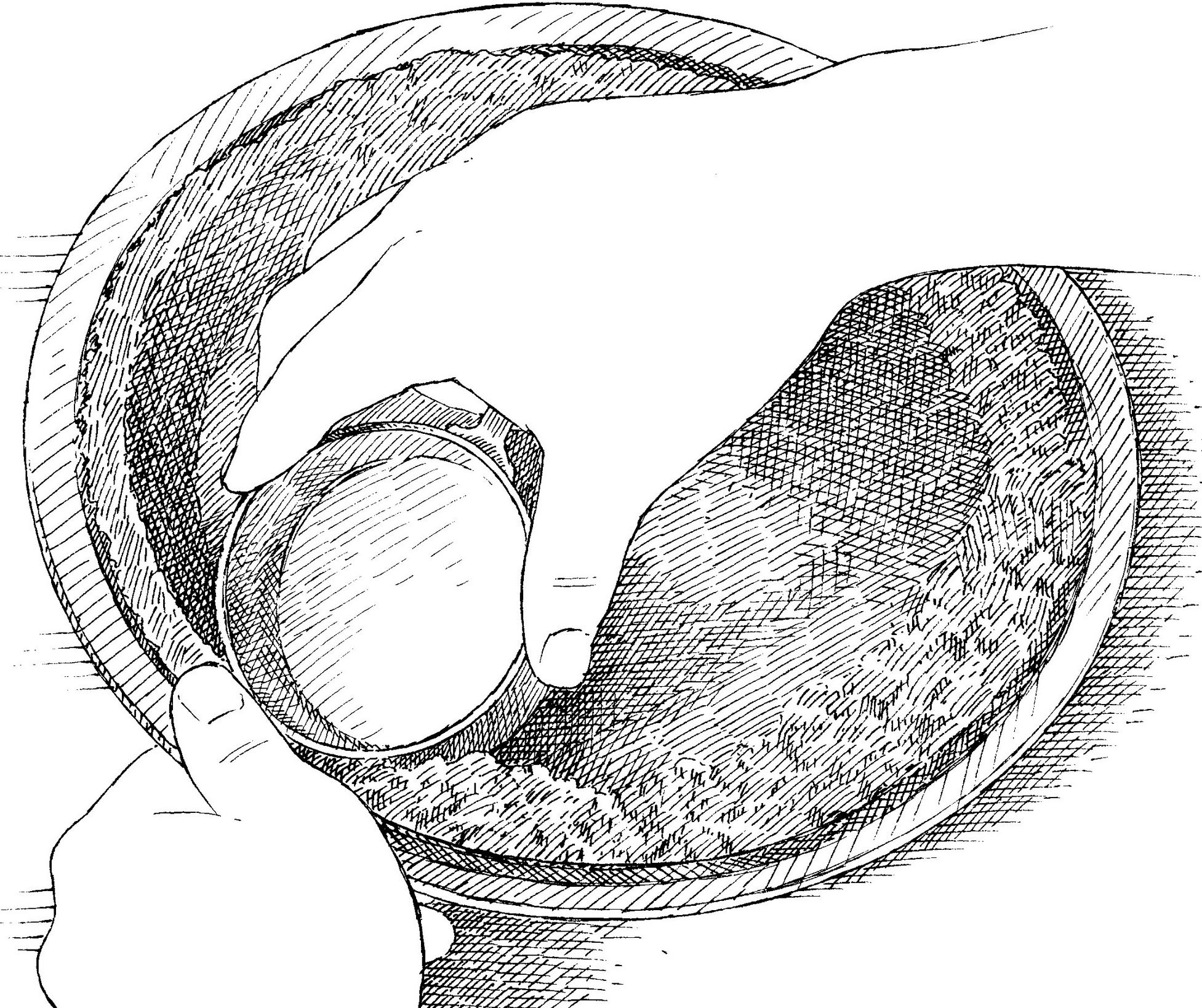

MAKING A ROSETTE

1. Arrange most of parcooked apple slices in tightly overlapping concentric circles.

2. Bend remaining slices to fit in center.

Outside the kitchen I’m sometimes a bit of a klutz, but give me a rolling pin and a lump of traditional all-butter pie dough—the kind that’s dry and brittle and exhibits an alarming tendency to crack—and I’ll dazzle you with my proficiency and grace as I roll it into a flawless circle. It’s a skill that’s taken me decades to acquire, and practicing it makes me feel like a high priestess of pastry. Happily, that feeling of accomplishment became accessible to even the most inexperienced bakers in 2010 when we developed our Foolproof Pie Dough, which is soft and moist and a dream to roll out and bakes up flaky and tender. But as great as that recipe is, I’ve never been 100 percent converted from my traditional ways.

UPENDING PIE TRADITION

The 2010 recipe controls the ability of the flour in the dough to absorb water. That’s important because water bonds with protein in flour to form gluten, the elastic network that gives baked goods their structure. If there’s too little water, the dough will be crumbly and impossible to roll and the baked crust will fall apart; too much water and the dough will roll out easily, but it may shrink when it bakes and will certainly be tough.

To appreciate just how revolutionary the 2010 recipe is, it’s helpful to recall the way that pie dough has been made for centuries: You start by combining flour, salt, and sugar, then cut in cold butter until it’s broken into pea-size nuggets. Then you add water and mix until the dough comes together in a crumbly mass with visible bits of butter strewn throughout.

But our 2010 dough spurns tradition: Using a food processor, you mix 1½ cups of flour with some sugar and salt before adding 1½ sticks of cold butter and ½ cup of shortening (often added to pie doughs to increase flakiness); you continue processing until the fat and the dry ingredients form a smooth paste. Next you pulse in the remaining cup of flour until you have a bunch of flour-covered chunks of dough and a small amount of free flour.

Finally, you transfer the dough to a bowl and stir in ¼ cup of water and ¼ cup of vodka to bring it all together. Why vodka? Because it’s 60 percent water and 40 percent alcohol, and alcohol doesn’t activate gluten. So replacing some of the water with vodka gives you the freedom to add enough liquid to make a moist, supple dough without the risk of forming excess gluten.

We process some of the butter with the flour and grate the rest into the dough to create a crust that bakes up tender, crisp, and shatteringly flaky.

TAKING THE ALL-BUTTER ROUTE

I’ve made plenty of pies with the 2010 dough, but honestly, I’m not crazy about using vodka and shortening. I don’t always have spirits on hand, and I prefer the richer flavor and cleaner mouthfeel of an all-butter pie crust. So I was intrigued when food writer J. Kenji Lopez-Alt, who developed the original recipe while working at Cook’s Illustrated, went on to create a shortening- and vodka-free version of the dough for the website Serious Eats. How could it work?

Quite well, actually. The new recipe called for just 6 tablespoons of water—the ¼ cup (4 tablespoons) called for in the original recipe plus 2 additional tablespoons to replicate the water content in ¼ cup of vodka. Even with less water, I found the dough only a little harder to roll out than the original, and it baked up just as tender and flaky.

Turns out that the quirky mixing method was much more important than I’d initially realized. Thoroughly processing a lot of the flour with all the fat effectively waterproofed that portion of the flour, making it difficult for its proteins to hydrate enough to form gluten. Only the remaining cup of flour that was pulsed into the paste was left unprotected and therefore available to be hydrated. The result was a limited gluten network, which produced a very tender crust even without the vodka.

And how did Lopez-Alt’s recipe work so well even without shortening? Well, shortening can be valuable in pie dough because it’s pliable even when cold, so it flattens into thin sheets under the force of the rolling pin more readily than cold, brittle butter does. But the flour-and-butter paste in this dough also rolls out more easily than butter alone would, so with the paste mixing method there’s no shortening required.

A GRATE SOLUTION

There’s no denying that the mixing method is a real game changer, but the crust it produces has a couple of faults. When I make pie dough the old-fashioned way I always get a nice sharp edge and a shatteringly flaky crust, but the edges of crusts made using the paste method usually slump a bit in the oven, even when I’m hypervigilant about chilling the formed crust. And that flakiness, which looks so impressive when you break the crust apart, doesn’t hold up when you eat it. The crust is a bit too tender, so the flakes disintegrate too readily on the palate.

Luckily, I thought I might know a way to fix both problems with one solution: I made a dough with a full ½ cup of water. My hope was that it would actually produce a little more gluten, thus giving the baked crust more structure and true crispness.

With all that water, the dough was as easy to roll as the vodka crust had been, and the slightly increased gluten gave the baked crust a more defined edge. But the crust was still a bit too tender for my taste. Maybe the best way to decrease the tenderizing effect of the butter was simply to decrease the butter.

I had been using two-and-a-half sticks of butter to equal the amount of fat in the vodka pie crust. I tried cutting back to an even two sticks, but that crust baked up hard and tough and felt stale right out of the oven. It was just too lean; I’d have to bring the butter back up to two-and-a-half sticks.

But something was bugging me: I’d made plenty of traditionally mixed all-butter pie crusts with an equally high proportion of fat. These doughs were challenging to roll out but the finished crusts always boasted just the right balance of crispness and tenderness. Why was this one so delicate?

And then I realized: In the traditional method much of the butter is left in discrete pieces that enrich the dough without compromising gluten development, but in my new crust, every bit of the butter was worked in. Perhaps the answer was to use the same amount of butter overall but to use less butter in the paste and to make sure that some of the butter remained in pieces.

Cutting the butter into very small pieces wasn’t feasible, but what if I grated it? I gave it a try, shredding 4 tablespoons of butter on a box grater. To ensure that those pieces stayed firm enough not to mix with the flour, I froze them. Meanwhile, I processed the remaining two sticks into the dry ingredients. After breaking up the paste, I pulsed in the remaining flour, transferred the mixture to a bowl, and tossed in the grated butter. Finally, I folded in ½ cup of ice water, which was absorbed by the dry flour that coated the dough chunks and the grated butter.

After a 2-hour chill, the dough rolled out beautifully. The fat-rich paste and the shredded butter–flour mixture swirled together, and, once baked, the crust held a perfect, crisp edge and was rich-tasting while being both tender and truly flaky.

Now that I have an all-butter pie dough that’s a cinch to roll out, I’m ready to adopt a new tradition.

Foolproof All-Butter Dough for Double-Crust Pie

MAKES ONE 9-INCH DOUBLE CRUST

Be sure to weigh the flour for this recipe. In the mixing stage, this dough will be more moist than most pie doughs, but as it chills it will absorb a lot of excess moisture. Roll the dough on a well-floured counter.

20 tablespoons (2½ sticks) unsalted butter, chilled

2½ cups (12½ ounces) all-purpose flour

2 tablespoons sugar

1 teaspoon salt

½ cup ice water

1. Grate 4 tablespoons butter on large holes of box grater and place in freezer. Cut remaining 16 tablespoons butter into ½-inch cubes.

2. Pulse 1½ cups flour, sugar, and salt in food processor until combined, 2 pulses. Add cubed butter and process until homogeneous paste forms, 40 to 50 seconds. Using your hands, carefully break paste into 2-inch chunks and redistribute evenly around processor blade. Add remaining 1 cup flour and pulse until mixture is broken into pieces no larger than 1 inch (most pieces will be much smaller), 4 to 5 pulses. Transfer mixture to medium bowl. Add grated butter and toss until butter pieces are separated and coated with flour.

3. Sprinkle ¼ cup ice water over mixture. Toss with rubber spatula until mixture is evenly moistened. Sprinkle remaining ¼ cup ice water over mixture and toss to combine. Press dough with spatula until dough sticks together. Use spatula to divide dough into 2 portions. Transfer each portion to sheet of plastic wrap. Working with 1 portion at a time, draw edges of plastic over dough and press firmly on sides and top to form compact, fissure-free mass. Wrap in plastic and form into 5-inch disk. Repeat with remaining portion; refrigerate dough for at least 2 hours or up to 2 days. Let chilled dough sit on counter to soften slightly, about 10 minutes, before rolling. (Wrapped dough can be frozen for up to 1 month. If frozen, let dough thaw completely on counter before rolling.)

variation

Foolproof All-Butter Dough for Single-Crust Pie

MAKES ONE 9-INCH SINGLE CRUST

Be sure to weigh the flour for this recipe. This dough will be more moist than most pie doughs, but as it chills it will absorb a lot of excess moisture. Roll the dough on a well-floured counter.

10 tablespoons unsalted butter, chilled

1¼ cups (6¼ ounces) all-purpose flour

1 tablespoon sugar

½ teaspoon salt

¼ cup ice water

1. Grate 2 tablespoons butter on large holes of box grater and place in freezer. Cut remaining 8 tablespoons butter into ½-inch cubes.

2. Pulse ¾ cup flour, sugar, and salt in food processor until combined, 2 pulses. Add cubed butter and process until homogeneous paste forms, about 30 seconds. Using your hands, carefully break paste into 2-inch chunks and redistribute evenly around processor blade. Add remaining ½ cup flour and pulse until mixture is broken into pieces no larger than 1 inch (most pieces will be much smaller), 4 to 5 pulses. Transfer mixture to medium bowl. Add grated butter and toss until butter pieces are separated and coated with flour.

3. Sprinkle 2 tablespoons ice water over mixture. Toss with rubber spatula until mixture is evenly moistened. Sprinkle remaining 2 tablespoons ice water over mixture and toss to combine. Press dough with spatula until dough sticks together. Transfer dough to sheet of plastic wrap. Draw edges of plastic over dough and press firmly on sides and top to form compact, fissure-free mass. Wrap in plastic and form into 5-inch disk. Refrigerate dough for at least 2 hours or up to 2 days. Let chilled dough sit on counter to soften slightly, about 10 minutes, before rolling. (Wrapped dough can be frozen for up to 1 month. If frozen, let dough thaw completely on counter before rolling.)

Deep-dish apple pies were traditionally baked without a bottom crust in casserole dishes, the generous filling blanketed with a layer of thick, flaky pastry. Nowadays, it is more common to find double-crust deep-dish apple pies, with the apples nestled between two layers of pastry. Unfortunately, these pies often bear little resemblance to their name, instead looking suspiciously like your standard apple pie. But I didn’t want a thin slice of plain old apple pie; I wanted a towering wedge of tender, juicy apples, fully framed by a buttery, flaky crust.

After foraging for recipes that met my specifications for deep-dish—a minimum of 4 pounds of apples as opposed to the meager 2 pounds in a standard pie—I realized that, while a standard apple pie may be juicy, most deep-dish pies are downright flooded with liquid. As a result, the bottom crust becomes a pale, soggy mess. In addition, the crowd of apples tends to cook unevenly, with mushy edges surrounding a crunchy center. Less serious—but no less annoying—is the gaping hole left between the apples (which shrink considerably) and the arching top crust, which makes it impossible to slice and serve a neat piece of pie.

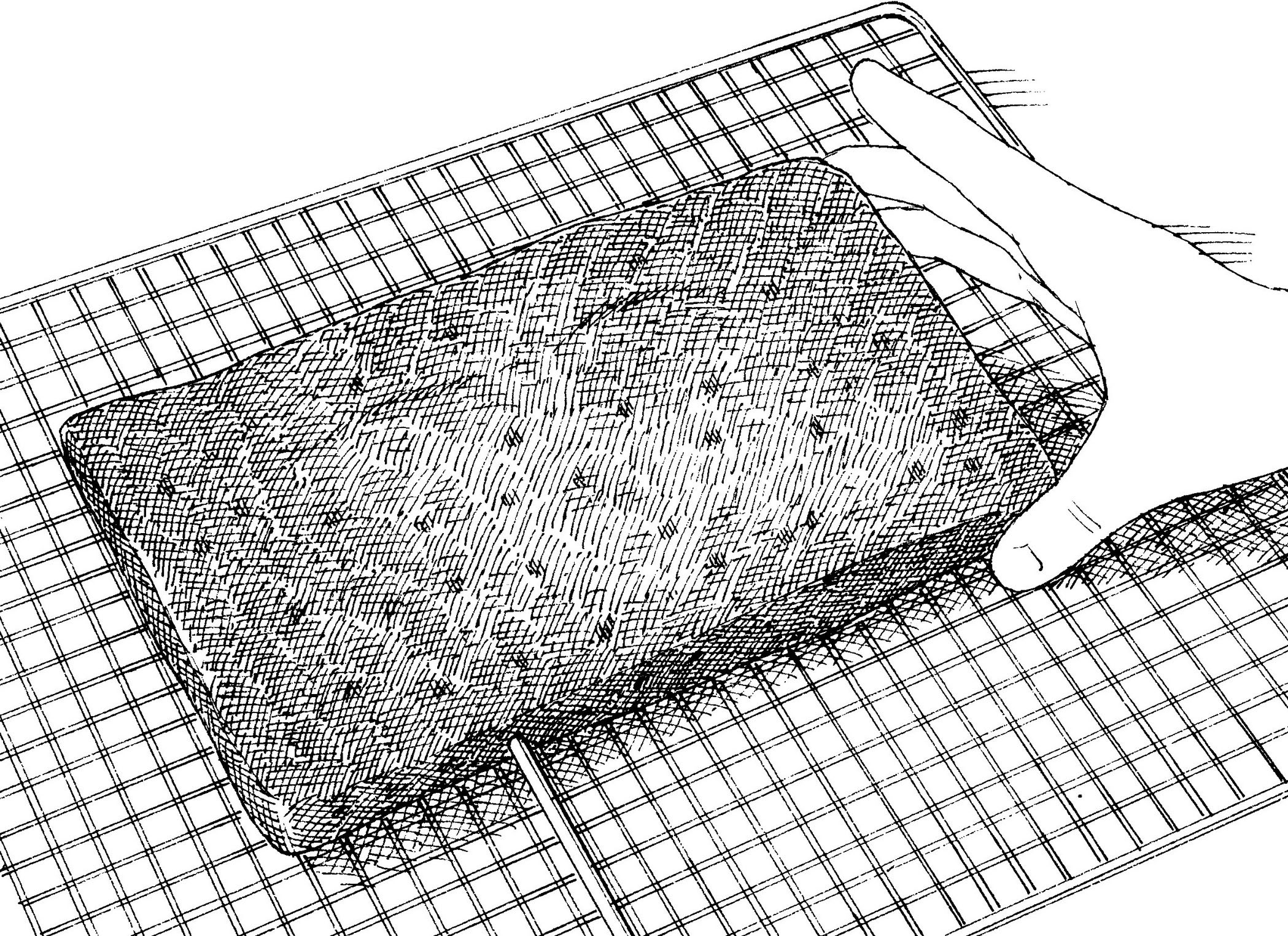

Sautéing the apples on the stovetop before loading them into the crust eliminates excess moisture and prevents gaps in the finished pie.

After a week of rescue efforts, I had made little progress. My failed attempts included slicing the apples into thick chunks and thin slices, cutting large vents in the pie dough before baking to promote steam release, and baking the pies at different temperatures. I tried moving the pie to the very bottom rack of the oven. No matter what I tried, I was confronted with a soupy filling and soggy crust. To sop up the copious amount of liquid, I added a thickening agent. But so much thickener (flour or cornstarch) was required to dam the flood that it muddied the bright flavor of the apples.

THE PECTIN PROBLEM

During my research, I had come across recipes that called for sautéing the apples before assembling them in the pie, the idea being to both extract juice and cook the apples more evenly. Although this logic seemed counterintuitive (how could cooking the apples twice cause them to become anything but insipid and mushy?), I forged ahead. After browning the apples in a hot skillet (in two batches to accommodate the large volume), I made yet another pie and then crossed my fingers. As expected, the apples were disappointingly mealy and soft, especially the exteriors, which had been seared in the hot pan. But this pie did deliver on a couple of counts: In addition to the absence of juice flooding the bottom of the pie plate, it offered a nicely browned bottom crust.

Could I keep the apples from disintegrating if I tried this method with a gentler hand? I dumped the whole mound into a large Dutch oven along with some granulated sugar (to flavor the apples and extract moisture) and then covered the pot to promote more even cooking. With frequent stirring over a medium flame for 15 to 20 minutes, the apples were tender yet still held their shape. After cooling the apples (so the butter in the crust would not melt immediately) and draining them, I baked the pie, which was again free of excess juice and sported the same browned bottom as before. This time, however, the apples weren’t mealy—they were miraculously tender.

After some digging, I discovered that apples undergo a significant structural change when held at moderately warm temperatures for 20 to 30 minutes. Between 120 and 140 degrees, the pectin is converted into a more heat-stable form. (While pectin provides structure in the raw fruit, it breaks down under the high heat of sautéing.) Once an adequate amount of pectin has been stabilized at low heat (as it apparently was on the stovetop), the apples can tolerate the heat from additional cooking (in the pie and in the oven) without becoming excessively soft.

To top it off, because the apples were shrinking before going into the pie rather than after, I had inadvertently solved the problem of the maddening gap, too. The top crust now remained united with the rest of the pie, and slicing was a breeze.

GETTING IN DEEP

Finally, with a cooking technique that produced picture-perfect results, it was time to adjust flavors. I snuck in another pound of apples (bringing the total to 5 pounds) to compensate for the bulk lost during stovetop cooking. Tart apples, such as Granny Smiths and Empires, were well liked for their brash flavor, but it was a one-dimensional profile. To achieve a fuller, more balanced flavor, I found it necessary to add a sweeter variety, such as Golden Delicious or Braeburn. Another important factor in choosing the right apple was texture. Even over the gentle heat of the stovetop, softer varieties such as McIntosh broke down and turned to mush.

With the right combination of apples, heavy flavorings were gratuitous. Some light brown sugar and granulated sugar, as well as a pinch of salt and a squeeze of lemon juice, heightened the flavor of the apples. After sampling the gamut of spices, tasters were content with just an unimposing hint of cinnamon. The perfect slice was no longer a deep-dish apple pie in the sky but a reality, sitting up nice and tall on my plate.

SERVES 8

If desired, you can substitute tart Empire or Cortland apples for the Granny Smith apples and sweet Jonagold, Fuji, or Braeburn apples for the Golden Delicious apples here.

1 recipe Foolproof All-Butter Dough for Double-Crust Pie

2½ pounds Granny Smith apples, peeled, cored, halved, and sliced ¼ inch thick

2½ pounds Golden Delicious apples, peeled, cored, halved, and sliced ¼ inch thick

½ cup (3½ ounces) plus 1 tablespoon granulated sugar

¼ cup packed (1¾ ounces) light brown sugar

½ teaspoon grated lemon zest plus 1 tablespoon juice

¼ teaspoon salt

⅛ teaspoon ground cinnamon

1 large egg white, lightly beaten

1. Roll 1 disk of dough into 12-inch circle on floured counter. Loosely roll dough around rolling pin and gently unroll it onto 9-inch pie plate, letting excess dough hang over edge. Ease dough into plate by gently lifting edge of dough with your hand while pressing into plate bottom with your other hand. Wrap dough-lined plate loosely in plastic wrap and refrigerate until dough is firm, about 30 minutes.

2. Roll other disk of dough into 12-inch circle on floured counter, then transfer to parchment paper–lined baking sheet; cover with plastic and refrigerate for 30 minutes.

3. Toss apples, ½ cup granulated sugar, brown sugar, lemon zest, salt, and cinnamon together in Dutch oven. Cover and cook over medium heat, stirring often, until apples are tender when poked with fork but still hold their shape, 15 to 20 minutes. Transfer apples and their juice to rimmed baking sheet and let cool completely, about 30 minutes.

4. Adjust oven rack to lowest position and heat oven to 425 degrees. Drain cooled apples thoroughly in colander set over bowl; reserve ¼ cup juice. Stir lemon juice into reserved juice.

5. Transfer apples to dough-lined plate, mounding them slightly in middle, and drizzle with apple juice mixture. Loosely roll remaining dough round around rolling pin and gently unroll it onto filling. Trim overhang to ½ inch beyond lip of plate. Pinch edges of top and bottom crusts firmly together. Tuck overhang under itself; folded edge should be flush with edge of plate. Crimp dough evenly around edge of plate using your fingers. Cut four 2-inch slits in top of dough. Brush surface with beaten egg white and sprinkle evenly with remaining 1 tablespoon granulated sugar.

6. Place pie on rimmed baking sheet and bake until crust is light golden brown, about 25 minutes. Reduce oven temperature to 375 degrees, rotate sheet, and continue to bake until juices are bubbling and crust is deep golden brown, 30 to 40 minutes longer. Let pie cool on wire rack until filling has set, about 2 hours; serve slightly warm or at room temperature.

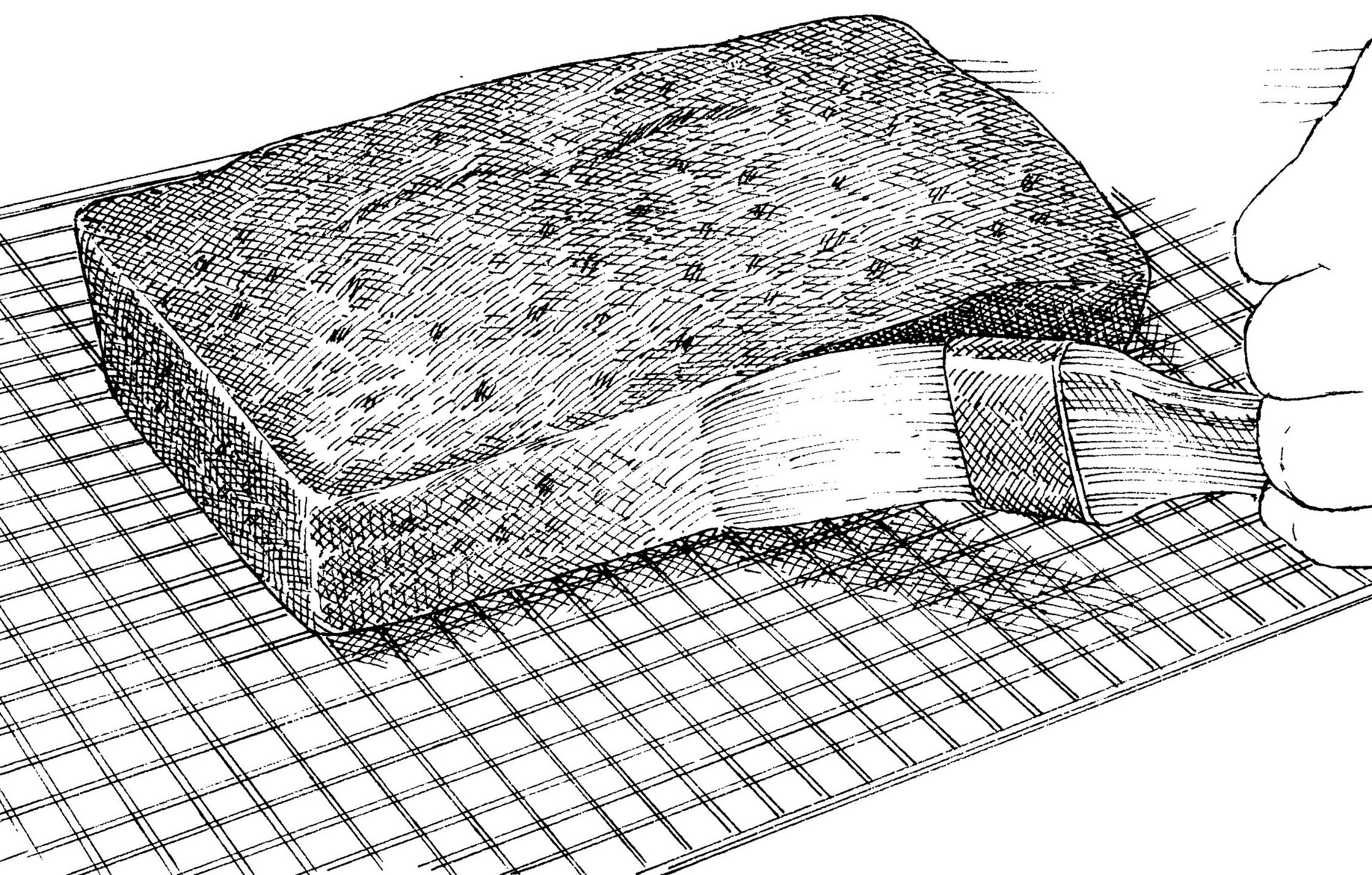

THE INCREDIBLE SHRINKING APPLE

When raw apples are used in a deep-dish pie, they shrink to almost nothing, leaving a huge gap between the top crust and the filling. Precooking the apples eliminates the shrinking problem and actually helps the apples hold their shape once baked in the pie. This seems counterintuitive, but here’s what happens: When the apples are gently heated, their pectin is converted into a heat-stable form that prevents the apples from becoming mushy when cooked further in the oven. The key is to keep the temperature of the apples below 140 degrees during this precooking stage. Rather than cooking the apples in a skillet (where they are likely to become too hot), it’s best to gently heat the apples and seasonings in a large covered Dutch oven.

COOK BEFORE BAKING Precooking the apples converts their pectin into a heat-stable form that prevents them from becoming mushy—even after being cooked twice.

VARIETY MAKES A BETTER PIE

A combination of sweet and tart apples works best in pie. These six varieties, all of which retain their shape when cooked, were our favorites in kitchen tests.

SWEET

GOLDEN DELICIOUS

Sweet with buttery undertones

BRAEBURN

Takes on a pear-like flavor when baked

JONAGOLD

Intensely sweet and buttery

TART

GRANNY SMITH

Vibrantly tart, holds shape best

EMPIRE

Strong, complex, cider-like flavor

CORTLAND

Similar to Empire, but more tart than complex

While the almost-impossible juiciness of a ripe peach is the source of the fruit’s magnificence, it’s also the reason that fresh peaches can be tricky to use in pies. The hallmark of any fresh fruit pie is fresh fruit flavor, but ripe peaches exude so much juice that they require an excess of flavor-dampening binders to create a filling that isn’t soup. Fresh peaches can also differ dramatically in water content, so figuring out how much thickener to add can be a guessing game from one pie to the next. Finally, ripe peaches are delicate, easily disintegrating into mush when baked.

I wanted to make a peach pie with tender yet intact fruit, and I wanted it to slice cleanly without being the least bit muddled, gluey, grainy, or cloudy.

For a cohesive filling with bright, clean flavor, we add a combination of pectin and cornstarch and mash a small portion of the peaches.

CREATING A CRUST

Before I could nail down the filling, I’d need a reliable crust. Experimenting with a few recipes taught me one thing: The fillings in pies with lattice-top crusts had far better consistencies than those in pies with solid tops, since the crosshatch allows moisture to evaporate during cooking.

The pliability of a typical double-crust pie dough makes it challenging to weave into a lattice; when making a lattice, it’s helpful to have a dough with a little more structure. Luckily, we have such a dough in our archives. A little extra water and a little less fat help create a sturdy dough that can withstand some extra handling. Just as important, this dough still manages to bake up tender and taste rich and buttery.

I also wanted to simplify the mechanics of building the lattice itself, which usually requires practice to create neat, professional-looking results, but I wanted a lattice that a novice baker could do perfectly. The best approach I found came from our Linzertorte, which skips the weaving in favor of simply laying one strip over the previous one in a pattern that allows some of the strips to appear woven. Freezing the strips for 30 minutes before creating the lattice made them easier to handle.

BOUND AND UNBOUND

Now it was time to get down to the fruit. Most recipes I’d tested called for tossing thinly sliced peaches with sugar and spices before throwing them into the pie crust and then putting the pie into the oven. But I’d noted that the peaches handled this way shed a lot of moisture before they even reached the oven, thanks to the sugar’s osmotic action on the slices. Sugar is hygroscopic—meaning it easily attracts water to itself—making it superbly capable of pulling juice out of the peaches’ cells. If I was going to gain control over the consistency of the filling, that’s where I’d need to start. Since osmosis occurs on the surface, one obvious tweak would be to make the peach slices relatively large to minimize total surface area. So instead of slicing the peaches thin, I cut them into quarters and then cut each of these into thick—but still bite-size—1-inch chunks.

I also let the sugared peaches macerate for a bit and then drained off the juice before tossing the fruit into the pie, adding back only enough juice to moisten—not flood—the filling. This would allow me to control how much liquid the peaches contributed from batch to batch. I tossed 3 pounds of peaches with ½ cup of sugar, 1 tablespoon of lemon juice, and a pinch of salt. When I drained the peaches 30 minutes later, they yielded more than ½ cup of juice. I settled on using just ½ cup to moisten the filling. To this I added just enough cinnamon and nutmeg to accent the flavor of the peaches without overshadowing it.

Now it was time to experiment with thickeners that would tighten up the fruit and juice while maintaining the illusion that nothing was in the pie but fresh peaches. Flour left the filling grainy and cloudy, while tapioca pearls never completely dispersed, leaving visible beads of gel behind. (Grinding the rock-hard tapioca pearls into finer grains helped but was a pain.) Potato starch and cornstarch each worked admirably up to a point, but after that they did not eliminate further runniness so much as turn the filling murky and gluey. More important, all these starches dulled the flavor of the peaches.

Maybe adding starch was not the best approach. I thought about apple pie, which barely needs any thickener to create a filling that slices cleanly. Apples are less juicy than peaches, but they also contain lots of pectin, which helps them hold on to their moisture and remain intact during baking. For my next test I stirred some pectin into my reserved peach juice, heated the mixture briefly on the stove, and then folded it into the peach chunks. This filling turned out smooth and clear and tasted brightly of peaches. But it was still runnier than I wanted. Adding more pectin would only make the filling bouncy. Then I thought back to our recipe for Fresh Strawberry Pie, which uses a combination of pectin and cornstarch. Could I find the sweet spot using both thickeners? Yes: Two tablespoons of pectin and 1 tablespoon of cornstarch left me with a filling that was smooth, clear, and moist without being soupy.

One problem remained: a tendency for the peach chunks to fall out of the pie slices. To fix this, I mashed a small amount of the macerated peaches to a coarse pulp with a fork and used it as a form of mortar to eliminate gaps and stabilize the filling.

At last, I had a fresh peach pie that looked perfect, tasted of fresh peaches, and sliced neatly.

Fresh Peach Pie

SERVES 8

If your peaches are too soft to withstand the pressure of a peeler, cut a shallow X in the bottom of the fruit, blanch them in a pot of simmering water for 15 seconds, and then shock them in a bowl of ice water before peeling.

3 pounds peaches, peeled, quartered, and pitted, each quarter cut into thirds

½ cup (3½ ounces) plus 3 tablespoons sugar

1 teaspoon grated lemon zest plus 1 tablespoon juice

⅛ teaspoon salt

2 tablespoons low- or no-sugar-needed fruit pectin

¼ teaspoon ground cinnamon

Pinch ground nutmeg

1 recipe Pie Dough for Lattice-Top Pie (recipe follows)

1 tablespoon cornstarch

1. Toss peaches, ½ cup sugar, lemon zest and juice, and salt in medium bowl. Let stand at room temperature for at least 30 minutes or up to 1 hour. Combine pectin, cinnamon, nutmeg, and 2 tablespoons sugar in small bowl and set aside.

2. Remove dough from refrigerator. Before rolling out dough, let it sit on counter to soften slightly, about 10 minutes. Roll 1 disk of dough into 12-inch circle on lightly floured counter. Transfer to parchment paper–lined baking sheet. With pizza wheel, fluted pastry wheel, or paring knife, cut round into ten 1¼-inch-wide strips. Freeze strips on sheet until firm, about 30 minutes.

3. Adjust oven rack to lowest position, place rimmed baking sheet on rack, and heat oven to 425 degrees. Roll other disk of dough into 12-inch circle on lightly floured counter. Loosely roll dough around rolling pin and gently unroll it onto 9-inch pie plate, letting excess dough hang over edge. Ease dough into plate by gently lifting edge of dough with your hand while pressing into plate bottom with your other hand. Leave any dough that overhangs plate in place. Wrap dough-lined pie plate loosely in plastic wrap and refrigerate until dough is firm, about 30 minutes.

4. Meanwhile, transfer 1 cup peach mixture to small bowl and mash with fork until coarse paste forms. Drain remaining peach mixture in colander set in large bowl. Transfer peach juice to liquid measuring cup (you should have about ½ cup liquid; if liquid measures more than ½ cup, discard remainder). Return peach pieces to bowl and toss with cornstarch. Transfer peach juice to 12-inch skillet, add pectin mixture, and whisk until combined. Cook over medium heat, stirring occasionally, until slightly thickened and pectin is dissolved (liquid should become less cloudy), 3 to 5 minutes. Remove skillet from heat, add peach pieces and peach paste, and toss to combine.

5. Transfer peach mixture to dough-lined pie plate. Remove dough strips from freezer; if too stiff to be workable, let stand at room temperature until malleable and softened slightly but still very cold. Lay 2 longest strips across center of pie perpendicular to each other. Using 4 shortest strips, lay 2 strips across pie parallel to 1 center strip and 2 strips parallel to other center strip, near edges of pie; you should have 6 strips in place. Using remaining 4 strips, lay each one across pie parallel and equidistant from center and edge strips. If dough becomes too soft to work with, refrigerate pie and dough strips until dough firms up.

6. Trim overhang to ½ inch beyond lip of pie plate. Press edges of bottom crust and lattice strips together and fold under. Folded edge should be flush with edge of pie plate. Crimp dough evenly around edge of pie using your fingers. Using spray bottle, evenly mist lattice with water and sprinkle with remaining 1 tablespoon sugar.

7. Place pie on preheated sheet and bake until crust is set and begins to brown, about 25 minutes. Rotate pie and reduce oven temperature to 375 degrees; continue to bake until crust is deep golden brown and filling is bubbly at center, 25 to 30 minutes longer. Let cool on wire rack for 3 hours before serving.

dough

Pie Dough for Lattice-Top Pie

FOR ONE 9-INCH LATTICE-TOP PIE

3 cups (15 ounces) all-purpose flour

2 tablespoons sugar

1 teaspoon salt

7 tablespoons vegetable shortening, cut into ½-inch pieces and chilled

10 tablespoons unsalted butter, cut into ¼-inch pieces and frozen for 30 minutes

10–12 tablespoons ice water

1. Process flour, sugar, and salt in food processor until combined, about 5 seconds. Scatter shortening over top and process until mixture resembles coarse cornmeal, about 10 seconds. Scatter butter over top and pulse until mixture resembles coarse crumbs, about 10 pulses. Transfer to bowl.

2. Sprinkle 5 tablespoons ice water over flour mixture. With rubber spatula, use folding motion to evenly combine water and flour mixture. Sprinkle 5 tablespoons ice water over mixture and continue using folding motion to combine until small portion of dough holds together when squeezed in palm of your hand, adding up to 2 tablespoons remaining ice water if necessary. (Dough should feel quite moist.) Turn out dough onto clean, dry counter and gently press together into cohesive ball. Divide dough into 2 even pieces and flatten each into 4-inch disk. Wrap disks tightly in plastic wrap and refrigerate for 1 hour or up to 2 days.

PEELING PEACHES

A sharp serrated peeler can make quick work of peeling soft, ripe fruit. If you don’t have one, you can blanch the fruit in boiling water. Score the bottom of the peach with an X before dropping it into the water. After 30 to 60 seconds, watch the skin around the X for signs of splitting and tearing. Remove the peach from the boiling water with a slotted spoon and plunge it into an ice bath to stop the cooking. Once the peach has cooled, pull it from the ice water and use a paring knife to help peel back the slippery skin, starting at the X. It should come off in large strips.

I’ve often wondered why apple pie beat out cherry as our national dessert. At their best, cherry pies are juicier, more colorful, and, in my opinion, just plain tastier than apple. It all boils down to a matter of availability. You can find decent apples year-round in even the most meagerly stocked supermarket, but cherry season is cruelly short—just a brief blossoming period during the early summer. And even when cherries are available, chances are they’re a sweet variety (usually crimson-colored Bing or red-yellow-blushed Rainier), not the rare, ruby-hued sour species prized for jams and pie-making.

What makes sour cherries such prime candidates for baking (most people find them too tart for snacking purposes) is their soft, juicy flesh and bright, punchy flavor that neither oven heat nor sugar can dull. Plumper sweet cherries, on the other hand, have mellower flavors and meaty, firm flesh—traits that make them ideal for eating straight off the stem but don’t translate well to baking. My challenge was obvious: Develop a recipe for sweet cherry pie with all the intense, jammy flavor and softened but still intact fruit texture of the best sour cherry pie.

SWEET AND SOUR

Before I abandoned sour cherries altogether, I needed to get my hands on one batch to help me understand how they function in pie compared with their sweeter cousins. With help from the U.S. Postal Service, I obtained a few pounds of the tart variety from an online retailer, baked them into a pie, and tasted it side by side with one made of supermarket sweet cherries. The difference was night-and-day. Compared with the sour cherry pie’s bracing acidity, the sweet cherry pie’s taste was beyond sweet; it was downright cloying. Even more problematic, the sweet cherries’ drier, relatively dense flesh failed to break down completely (even after an hour or more of baking) and resulted in a filling that called to mind slightly softened jumbo marbles, not fruit.

So I had two issues to resolve: taming the cherries’ sweetness, and getting them to break down to the proper juicy texture. To get my bearings, I made another pie. I combined 2 pounds of pitted fresh Bing cherries and 1 cup of sugar, stirred in 3 tablespoons of ground tapioca (tasters’ preferred thickener in earlier tests), poured the filling into a shell, and wove a traditional lattice-top crust to show off the fruit’s jewel-like shine. After it had baked and cooled, I offered my colleagues a bite. As I expected, nobody could taste past the sweetness. Figuring all that sugar wasn’t helping, I tried cutting back a few tablespoons at a time, but that only created a new problem: Since sugar draws moisture out of the cherries through osmosis, less of it made for a less juicy filling. A half-cup was as low as I could go without completely ruining the texture, but the filling still verged on candy sweetness.

By pureeing some of the cherries with plums and skipping the lattice crust, we create a flavorful and juicy pie with sweet cherries.

My only other option was to add another ingredient to offset the sweetness. A couple of splashes of bourbon—a classic pairing with cherries—helped, as did the acidity of fresh lemon juice, but these were minor tweaks, and adding more of either just made the pies taste boozy or citrusy. I even tried vinegar, hoping to more closely mimic the tartness of sour cherries, but tasters objected to the sharpness of even the smallest drop. As a last-ditch effort, I tried introducing alternative fruits: super-t art fresh cranberries (too bitter), tangy red grapes (too musty), and dried sour cherries (too chewy).

None of these ideas panned out, but the concept did get me thinking about other types of fruit. Cherries fall into the stone-fruit category, along with peaches, nectarines, and plums. Sweet-fleshed peaches and nectarines wouldn’t help me, but the tartness of plums might be worth a shot. For my next pie, I sliced a couple of plums into the filling, but their flesh was just as dense and resilient as the cherries’. No problem, I thought; this was nothing my trusty food processor couldn’t fix. I made another pie, this time pureeing the plums and mixing the resulting pulp with the cherries. Perfect! The flavor, now tangy and complex, was spot on, and nobody suspected my secret.

SEALING IN THE JUICES

Now that I’d crossed one challenge off my list, I was ready to tackle the sweet cherries’ overly firm texture. The problem was twofold: Not only were the cherries refusing to break down, as a result they also weren’t releasing enough juice to amply moisten the filling. As it turned out, the culprit was cellulose, the main structural component of fruit cells: Compared with sour cherries, the sweet variety contains a full 30 percent more cellulose, making the flesh more rigid.

Without a way to rid the cherries of that extra structure, I’d have to rely on more conventional techniques to soften the flesh. I was already macerating them in sugar before baking to help draw out some of their juices, but with their relatively thick skin, this technique wasn’t effective. Halving them helped considerably, since their juice was very easily drawn out of the exposed fleshy centers. Even better, the cut cherries collapsed more readily and turned out markedly softer in the finished pie, save for a few too many solid chunks. By tossing a portion of them (1 cup) into the food processor along with the plums (and straining the chewy skins out of the resulting pulp), I got a filling that was ideally soft, if a bit dry, and studded with a few still-intact cherry pieces. As a bonus, the pies I tested using a good brand of frozen sweet cherries—an easier alternative to pitting dozens of the fresh variety—baked up equally well, making this an any-season dessert.

I’d hoped that mashing and precooking the cherries with sugar would help release some fruit juices, but this technique actually caused moisture to evaporate through the crust’s ventilated top as it baked, leading to a drier pie. Then I realized: My problem wasn’t the fruit itself, but the lattice crust. Juice-gushing sour cherry and berry pies may benefit from the extra evaporation of a woven crust, but with these cherries I needed to keep a tighter lid on the available moisture. Rolling out a traditional disk of dough, I fitted it to the bottom pastry, neatly sealed the edges, and slid the whole assembly onto a baking sheet before putting it in the oven to ensure that the bottom crust crisped up before the fruit filling could seep through. An hour or so later, out came a gorgeously golden-brown, perfectly juicy (but not runny) pie. When my tasters began to line up for second helpings, I knew I’d finally gotten cherry pie in apple-pie order.

Sweet Cherry Pie

SERVES 8

Grind the tapioca to a powder in a spice grinder or mini food processor. You can substitute 2 pounds of frozen sweet cherries for the fresh cherries. If you are using frozen fruit, measure it frozen, but let it thaw before filling the pie. If not, you run the risk of partially cooked fruit and undissolved tapioca.

1 recipe Foolproof All-Butter Dough for Double-Crust Pie

2 red plums, quartered and pitted

2½ pounds fresh sweet cherries, pitted and halved

½ cup (3½ ounces) sugar

2 tablespoons instant tapioca, ground

1 tablespoon lemon juice

2 teaspoons bourbon (optional)

⅛ teaspoon salt

⅛ teaspoon ground cinnamon (optional)

2 tablespoons unsalted butter, cut into ¼-inch pieces

1 large egg, lightly beaten with 1 teaspoon water

1. Roll 1 disk of dough into 12-inch circle on floured counter. Loosely roll dough around rolling pin and gently unroll it onto 9-inch pie plate, letting excess dough hang over edge. Ease dough into plate by gently lifting edge of dough with your hand while pressing into plate bottom with your other hand. Wrap dough-lined plate loosely in plastic wrap and refrigerate until dough is firm, about 30 minutes. Roll other disk of dough into 12-inch circle on lightly floured counter, then transfer to parchment paper–lined baking sheet; cover with plastic and refrigerate for 30 minutes.

2. Adjust oven rack to lowest position and heat oven to 400 degrees. Process plums and 1 cup cherries in food processor until smooth, about 1 minute, scraping down sides of bowl as necessary. Strain puree through fine-mesh strainer into large bowl, pressing on solids to extract as much liquid as possible; discard solids. Stir remaining cherries; sugar; tapioca; lemon juice; bourbon, if using; salt; and cinnamon, if using, into puree. Let stand for 15 minutes.