During the latter part of 1991, we conceived a series of counterinfiltration operations called ‘Mousetrap’. In these operations we adopted a dynamic matrix of positions in tiers that we changed frequently. As a result, we achieved quite spectacular results. Our success story was covered prominently in Frontline magazine of 31 January 1992.

In Operation Mousetrap we had one of our finest counterinfiltration actions. It began very unexpectedly. On the morning of 27 November ‘91, when I was having breakfast, I heard the sounds of a shooting engagement from across the Jhelum river. I asked my brigade major, R.P.S. (Rajpal) Mann, to find out what was happening. He enquired from the battalion on the LoC if there was an encounter going on with terrorists somewhere. They said no. The exchange of fire continued nonetheless and from the sound of gunshots, it did not appear to be happening too far away. I therefore decided to move with my protection party and quick reaction team (QRT) towards the action site. ‘Let’s go,’ I ordered Captain V.K. Singh, the brigade education officer, as our convoy sped off. VK was officiating as the general staff officer (intelligence) of the brigade. We crossed the bridge over the Jhelum and had barely gone a kilometre or so when we saw twenty-five to thirty soldiers running down the road towards us. When we asked them about the firing, they displayed total ignorance. I almost lost my shirt at their lack of interest, but it was amusing to learn that in the middle of this battle, these soldiers were going through a point-to-point map-reading test! I asked if they were carrying any ammunition along with their rifles. On getting a positive nod, I asked them to hop on to the protection vehicles and we proceeded ahead. We reached near the site of the encounter within an hour, dismounted from the vehicles and proceeded cautiously till we closed in. Up to this moment we had no idea whatsoever as to who was fighting and with whom. Soon Captain S.S. Anjaria of 2/11 GR crept up to me and started to brief me about the situation. Before he could begin, I told him that I had with me about fifty soldiers who could be employed to beef up his force. So it was decided that the motley group of men doing the map-reading test could be used in squads of eight men to form an outer ring to isolate the area and prevent the terrorists from escaping, whereas the QRT and my protection party would engage the terrorists hiding in the folds of the sloping ground. This timely arrival of additional troops gave the hard-pressed men of 2/11 GR a shot in the arm.

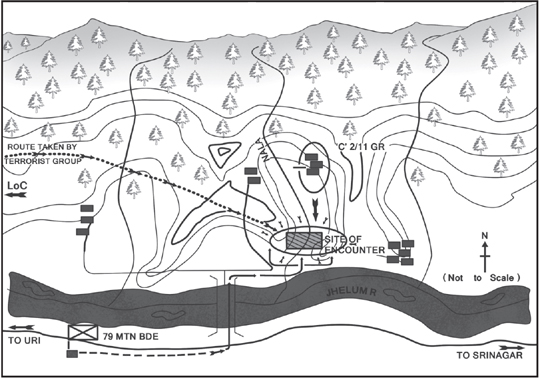

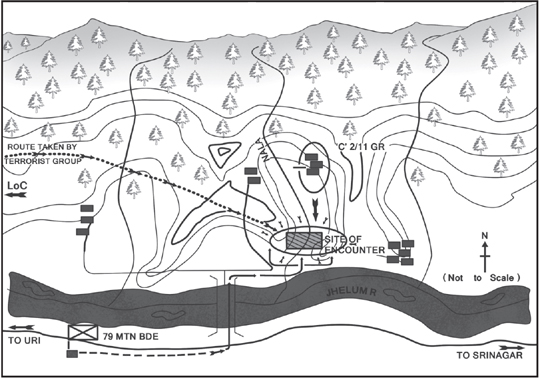

Thereafter Anjaria proceeded to brief me, and I was truly impressed with the actions of this brave officer and his outnumbered gallant Gurkhas. Despite the odds, they had hemmed in about twenty-odd heavily armed terrorists coming down the hill from the direction of the LoC. By this engagement, they had prevented the infiltrators from entering a nearby village. Once there, the terrorists could have easily escaped by merging with the locals and concealing their weapons and equipment (see Sketch 12.1).

In this skirmish, the young captain and his men had knocked down eight to ten terrorists, and sporadic yet intense exchange of fire was continuing. We had no casualty from our side thus far, and we could count at least ten dead terrorists lying around in the broken ground ahead of us. It was around 11 a.m. and I was confident that in a couple of hours we would be able to take care of all of them. At that moment, I felt a sudden piercing pain. The realization that I had been shot struck me when I felt some warm fluid flowing down my left leg. It was blood oozing out from both wounds.

I slumped to the ground, and was assisted by VK and taken to a somewhat secure place nearby, away from direct fire of the terrorists. Someone got hold of a field dressing and tied a bandage over the wound as the pain kept increasing. I told Anjaria and V.K. Singh that I did not want to be evacuated till someone responsible could take control of the operation. It was about 11.30 a.m. by then.

The brigade second-in-command, Colonel U.R. Chaudhri, arrived with the medical officer in about an hour. The tactical situation was explained to him and he took charge. Meanwhile, the doctor dressed my wound afresh and gave a shot of morphine, a very effective painkiller and the saviour of wounded soldiers ever since the First World War. As taught in medical schools, he put down details such as the dose administered along with the time at which the tranquillizer was injected, on the huge white sterilized bandage itself, and wrote out a brief medical report. As happens with a ‘high velocity and spinning hardnosed’ bullet of a 7.62-calibre ‘Dragunov’ sniper rifle, which I suspect was the type of weapon used to target me, it went through my groin making a hole the size of a small coin, but the exit wound in the buttock was about two square inches of shattered blood vessels, nerves and flesh, with blood all over! Intermittent firing continued to take place as I was evacuated on a stretcher to the road where a jonga (MUV) ambulance was waiting. From there, it took us about two hours to reach the nearest helipad, and I was flown to Srinagar in the waiting chopper.

Sketch 12.1: Encounter with terrorists during Operation Mousetrap, 1991.

We landed at Badami Bagh, the cantonment of Srinagar, at around 4 p.m. Once again I was put into the ambulance, and taken straight to the military hospital. I was feeling very weak and exhausted and in shock, because of substantial loss of blood and the pain. The effect of the morphine was still there, though my leg felt dead as a log of wood! Soon we arrived at 92 Base Hospital and I was wheeled on the stretcher directly to the operation theatre. The surgical specialist, Lieutenant Colonel Brij Mohan Nagpal, opened the field dressing and asked the paramedic to get an X-Ray done. Fortunately, there was no bone injury, thereby making the surgery less complicated. General anaesthesia was then administered to me. Once tranquillized, I lost consciousness. Later, the nursing officer told me that the doctors took two-and-a-half hours to complete the surgery. They did it with great precision and professionalism, as is their wont, and I can swear on that now. After the operation, I was taken to the intensive care unit.

I got back to my senses at about 7 p.m., when the effect of the anaesthesia wore off. I enquired about the encounter and was told that it was still continuing, that there had been no further casualties on our side, while about twenty terrorists had been shot dead. My younger brother, Lieutenant Colonel B.J. Singh, who was a medical specialist in the army, on learning of the incident, told me, ‘Brother, it was a very close call for you. A few millimetres on either side and it could have been fatal – the femoral artery and vein pass through that region. It is divine intervention that has saved you!’ 27 November 1991 was a long day and I can never forget Lieutenant Colonel Nagpal, the surgeon who saved my life.

A lot of visitors, including Corps Commander Lieutenant General Surinder Nath and Lieutenant General M.A. Zaki (Retd), the security adviser to the government of J&K, came to the hospital to wish me a speedy recovery. Captain S.S. Anjaria was decorated with a Sena Medal, and a few of his soldiers were also honoured for their gallant actions in this operation.

At some level, questions were raised as to why I had gone so far ahead. It was as if I had done something wrong! It was my considered view that I must always try and be upfront, share the same risks that my soldiers were facing, and damn well get to know what’s going on. Irregular warfighting is often so messy and complicated that decisions of far-reaching consequences have to be taken there and then, in real time. For example, if women congregate and attempt to storm and effect the release of a detained terrorist leader, and further, if terrorists wearing burqas and masquerading as women are amongst them, and they open fire at our troops, what would you do? One faux pas is enough to ignite a storm. Those of us who have handled such situations and survived are the unsung heroes of this dirty war in J&K and the northeast and elsewhere in the world, be it Afghanistan, Iraq or Bosnia. As a leader I would like to be in the picture and importantly, in the front, rather than in my office. I am convinced that all commanders up to the rank of brigadier should consider themselves as field commanders and act accordingly. Beyond that rank, the general officers should decide for themselves as to when and where their presence would be necessary in the combat zone, so that they can motivate the troops, guide the formation and unit commanders, and get a feel of the ground.

The nurse told me that my wife, Rohini, was on the way and would be joining me soon. It was the best possible news I could have received and it made me feel brighter. On arrival, she gave me a lovely bouquet of roses, and her presence cheered me up no end. For a few hours it was just the two of us. Rohini was full of questions, and we kept talking.

Many years later I asked Anjaria, who had become a colonel by then, to give me an account of how he saw the events on that memorable day. This is an extract of what he had to say: ‘Since the column of 2/11 GR was grossly under strength due to the numerous stops and ambushes already out, the QRT which arrived was most welcome. During the process of engaging the ANEs [anti-national elements] the Cdr, Brig JJ Singh, VSM was identified and spotted by the ANEs. A short burst of AK fire hit the Cdr in the groin. Despite being injured and bleeding profusely Brig JJ Singh, VSM continued to coordinate the operations and even spoke to the GOC 19 Mtn Div on the Radio Set.’

It is not in my nature to talk about this gunshot wound. But over the years, many people have wanted to know about my injury. Besides, it is rare for an officer of flag rank to get wounded in action against terrorists, and not every soldier is fortunate to be bloodied in battle. Therefore, this experience finds a place in this narrative.

The Lashkar-e-Toiba and other terrorist groups against whom we were pitted celebrated my ‘killing’. It appears that they had already claimed the prize money for my scalp from their ‘tanzeem’.

I rejoined my brigade instead of taking sick leave after being discharged from the hospital. The terrorists found it unbelievable, and thought it was not me but my ghost. Their masters across the border were livid. They ordered the divisional commander of the terrorists to return the claim money and warned him against giving false reports in future. At the same time, they were told to make another plan to finish me off as soon as possible. This information was passed on to us by one of our sources.

During the next three to four months, we notched up many more successes in our operations against the terrorists. More than seventy young men who had gone across the border for training and come back with an AK-47, deserted the ranks of their ‘tanzeems’. They had realized the futility of their mission, and surrendered to my battalions. To avoid the penalty of Rs 20,000 that would have to be paid to the ‘tanzeem’ towards the cost of the gun, they asked our troops to enact a kind of drama and capture them from pre-arranged spots. As an incentive, we helped to secure jobs for them in the Uri civil power project being executed by a Swedish company in 1991–92. Some of them were appointed as security guards! Today, we have a surrender policy under which these misguided young men are rehabilitated so that they can join the national mainstream.

In November 1991, we were delighted to receive this telegram from the chief of the army staff:

REFERENCE OPERATIONS OF 79 MTN BDE IN OP MOUSETRAP II ON 22 AND 23 NOV 91 (.) REQUEST CONVEY APPRECIATION AND CONGRATULATIONS OF CHIEF OF THE ARMY STAFF TO CONCERNED TROOPS IN OP MOUSETRAP II.