The terrorist organizations started carefully monitoring my movements. They noticed that I used to visit the Division HQ frequently, to brief the GOC, Major General Inder Varma. Accordingly, they worked out a meticulous plan to get rid of me in an urban ambush in the heart of Baramulla town at Tashkent Chowk. It was something like the ambush of the Sri Lankan cricket team in Lahore some years ago. I often wonder how we escaped death that day.

As I recall the events on that clear summer day in 1992, based on my memory of the interrogation of captured terrorists, information from local sources, and a vivid description given by an officer who happened to be on leave and present in Baramulla that day, I have reconstructed the deadly ambush.

Terrorists’ Hideout – Baramulla, July 1992

‘This b—–d of a brigadier, “Shaitan Singh,” is becoming a pain. We have to get rid of him’, said the leader in a deep voice.

‘Tomorrow, I understand he is likely to drive through Baramulla. Though the son of a bitch never follows a predictable routine, my “source” is very sure of his information this time. We shall give this infidel such a reception that he and his protection team wouldn’t know what hit them. None of these motherf—–s of the “Shaitan” Brigade should get away alive.’ He then unfolded his plan to his handpicked comrades in a cool and deliberate manner, leaving no room for error.

‘Have you understood? Koi shak (any doubts)’, he asked. The others just nodded.

‘Okay then get on with it, and Insha Allah, we shall be crowned with success. I must caution you – never underestimate these kafirs and their commander. I know this “harami” well. He is a cat with nine lives. But, we will not let him get away this time. See to it that he is despatched to his God,’ said the leader with a chuckle.

‘Hello Zulu 1, “Phantom” leaving for “Taj Mahal” now…. ETA [expected time of arrival] 0950 hours … over,’ was the cryptic transmission by Captain Suresh Kumar, the general staff officer (intelligence) of the brigade, informing the Division HQ about my move.

‘Yankee for Zulu 1 – roger out.’

Soon our convoy of four vehicles was snaking its way along the mountainous road. ‘Move it,’ I commanded the driver. The Nissan Patrol’s two-litre engine revved up as the driver pressed on the accelerator.

‘Don’t you know that someone who moves slowly would be a f …..g dead duck, in this combat zone.’

‘Yes sir,’ was the prompt reply.

In normal practice, the convoy was led by a 1-tonner that carried the leading protection detachment of six soldiers. A machine gun was fitted on a bracket in the front with a swivel mounting, so that it could be fired in any direction. The commander of this detachment sat in the front cab, hawk-eyed and ever alert. A similar detachment was mounted in the other 1-tonner at the tail of the convoy. Sandwiched between them was my Nissan jonga and the Rover jeep (communication vehicle). I am convinced that in war, to do the expected or being predictable means disaster. Therefore, I did my best to achieve an element of surprise. ‘The terrorist could appear from anywhere, and what is worse – at any time,’ I would often remind my officers. ‘Remember, that’s the reason I am ready for action day or night and I and this loaded AK-47 are inseparable,’ pointing towards my gun.

The convoy halted after taking a sharp turn five kilometres short of Baramulla. ‘All seems quiet today, Sir,’ said Captain Suresh, with a twinkle in his eye. Belonging to the artillery, he, apart from Captain V.K. Singh of the Education Corps, had seen more bullets being fired at him than many infantry officers. These youngsters were always brimming with enthusiasm and itching to prove their worth. While having tea, we watched the Jhelum river as it hit the rapids.

‘Fly the pennant and uncover the star plate,’ I ordered. This was something I never did normally. Why I took this decision on this day, I cannot explain.

‘Today, I will lead the convoy through the town upto the Division HQ’, I said to myself as I drove off with a zip, with the other three vehicles following behind.

‘Sir, did you notice the looks of the young man at the tea stall where we had stopped for tea,’ remarked Suresh, looking earnestly at me.

‘Yes, indeed. I felt he appeared nervous and fidgety, I wonder why!’

‘I think he was a terrorist,’ said Suresh.

Soon our convoy entered the town. The highway passed right through the middle – as in a typical Kashmiri town. There were rows of houses and shops on both sides. It seemed a normal summer morning. Children were on the way to school, and the shopkeepers and wayside fruit and vegetable vendors were laying out their wares. Horse-driven carts, the primary mode of conveyance in a town like this, were moving to and fro. Just like any other day.

We had barely gone beyond Tashkent Chowk, the main crossroads in the centre of Baramulla, when all hell broke loose! Hot and lethal metal spewed by machine guns and rifles rained down on my convoy from houses and rooftops, and loud explosions of grenades and rockets enveloped the area in a cloud of dust. There was bedlam and one could notice people running helter-skelter for cover. Some just dived to the ground to get out of the line of fire, and shielded their heads. Fortunately, there were no fatalities, but some were wounded or had a close shave and were under shock.

A surge of adrenaline pumped into my bloodstream automatically, as bullets and shrapnel whizzed past. It felt that the next burst would hit us. The shock effect lasted a few seconds.

Regaining my composure, I yelled into my radio, ‘Hullo all stations Zulu, keep moving, I repeat, keep moving – and don’t stop till we are out of this hellhole! Shoot your way through, and keep the b—–ds’ heads down’.

Stopping there would have been a grave mistake. The elaborately laid ambush was spread over 150 metres. As ordered, the troops carried on firing and fighting through the flak, mounted on their vehicles, as rehearsed by them many times. Once we were out of the killing area, I stopped and asked the men to quickly dismount from the vehicles and return fire from whatever cover they could find.

‘Phew, that was indeed a close shave for all of us,’ I remarked.

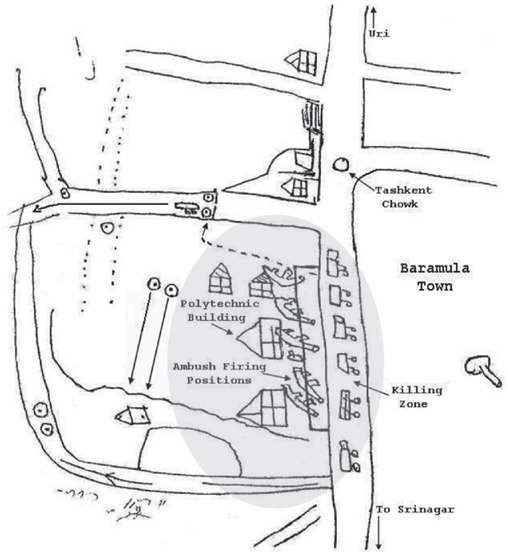

The ambush plan was immaculate; thought out in minute detail. The terrorist in the tea shop on the highway gave the early warning. The stops were deployed on both ends of the ambush point, and the firing party covered the killing zone effectively. The getaway routes were well reconnoitred and mock rehearsals carried out in advance. The ambush was to be sprung on the command of the leader. This was what was going to decide the success or failure of the mission. The timing had to be perfect.

Scene of Ambush – Tashkent Chowk, Baramulla, July 1992

‘Get them! Don’t let them escape’, shouted the leader of the terrorists. He realized that he had delayed the signal to open fire by a few seconds. It was only because he wanted to be sure of getting his kill, and not act prematurely. However, he never anticipated the commander to be up ahead and leading the cavalcade.

‘The commander is in the leading vehicle. He is in the jonga! Take him on with the machinegun, fire the RPG, bring down fire of all weapons, kill him, kill the b——d,’ shouted the leader. The machine-gunner tried his best to execute the orders of his leader, but he couldn’t aim at the jonga as by then, it was obscured by the 1-tonner. Frustrated, he emptied the whole magazine in a long burst through the truck, not sure if he had got his target. His colleague got excited and pressed the trigger of the rocket launcher but missed the jonga. He saw the rocket explode with a loud bang in the school playground which lay in the flight path beyond the intended target!

Realizing the futility of continuing with the action and the fact that his prey had gotten away this time too, the terrorist leader ordered his companions to abandon their positions and make good their escape as quickly as possible.

‘Break contact. Cover each other while you do so and get away. I will meet you at the Maulvi’s house in Shera village as soon as you all reach there. Ensure no one is left behind,’ yelled the leader before slinking away with his bodyguards to the ‘getaway car’ parked in a lane nearby.

‘Yeh saala Shaitan Singh is waqt bhi haath se nikal gaya hai. Allah hi usko bacha raha hai’ (this b——d has gotten away this time too. Allah seems to be saving him), said the leader to his mentors on the walkie talkie. The firing continued in spurts for a while, as the terrorists thinned out and disappeared into the alleys of the old town.

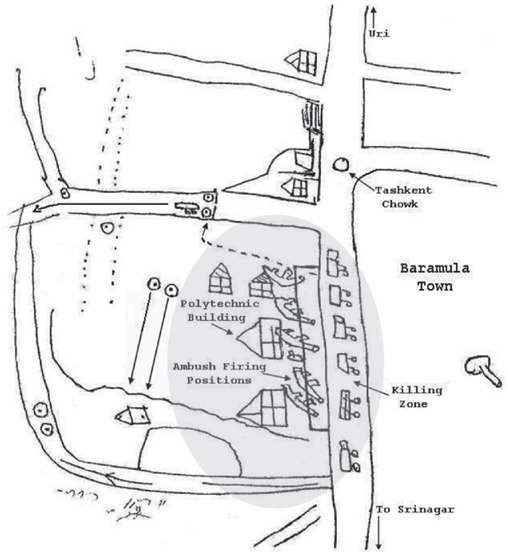

The diagrammatic plan of the elaborately conceived urban ambush to eliminate me was recovered by chance from the person of an apprehended terrorist named Nissar some days later (see Sketches 13.1 and 13.2).

The detailed planning that the terrorist group had carried out is evident from the sketch. The reverse side of the hand-drawn plan had the names of the terrorists, their locations and tasks. In all there were about twenty terrorists who took part in this ambush.

Quickly, Suresh regained control of the group, and it was then that he realized that the last vehicle of the convoy was nowhere to be seen. It had got detached from the rest in a deliberate blocking action by a truck that appeared from the opposite direction. However, the leader of the rear protection party, a thorough professional, did not play into the terrorists’ hands. He wisely deployed the men at the far end of the ambush site, and did not blunder into the killing zone. Had they tried to join up with the rest of us, none of them would have survived the murderous onslaught.

It was a deliberate strategy of the terrorists to execute this action in the marketplace so that the blame for the civilian casualties and other collateral damage could be attributed to the army. They could always count on the support of their overground workers and the local media. In the race for sensational ‘breaking news’, some reporters were ready to look the other way.

Sketch 13.1: The terrorists’ ambush plan at Tashkent Chowk, Baramulla.

We were old hands at this game and did not oblige the terrorists. Our response to this provocation was measured and cool. We fired accurately and purposefully and for effect. During the fierce encounter in the bustling market, it was amazing that only a few civilians had got injured in the crossfire.

Having deployed the available troops, we took stock of the situation. I was happy to see that there were no fatal casualties amongst my men. The Rover, which stood out because of its antenna, bore the brunt of the deadly ambush, and its driver got hit by a burst of a machine gun. Yet this brave soldier kept on moving.

Sketch 13.2: Names of terrorists who were part of the ambush.

Suresh ordered the men to fan out from both sides, and in a pincer movement they carefully advanced towards the site of the ambush. The terrorists had hastily abandoned their positions and vanished.

The ambushers had deployed themselves behind a wall so that they could take us on at point-blank range, from both sides of the road. There were impressions of their boots on the tables placed behind the wall of the polyclinic, from where the murderous fire was unleashed. A large number of fired cartridges of the AK-47 and the universal machine gun were scattered all over. There were blood stains on one of the tables. The trail of the blood stains ended in the alley from where, possibly, the injured terrorist was picked up by a vehicle. Finding nothing more, the search was called off. I led the convoy to the Division HQ at the other extreme of the town.

‘Thank God, you are safe. What is your plan of action now?’ asked the brigadier who was the officiating GOC. ‘Sir, I would recommend a cordon-and-search of Shera village at the earliest. I am sure these b—–ds have gone there, and would soon disperse,’ I said, based on confidence that comes only from experience.

‘Go right ahead, you have my okay,’ said the officiating GOC. The cordon-and-search operations were carried out and over the next few days, we caught a few of these terrorists. I addressed the people as usual, and mockingly asked them to convey to the terrorists that they must go back and do some more training. They wasted so much of ammunition in the ambush!

Twelve years later, I was amazed when the story of this ambush was recounted by an officer whom I had never met before. During my farewell visit to 2 Corps at Ambala in December 2004 as the chief designate, a retired lieutenant colonel came up to me and said he was present in Baramulla on a holiday in 1992. He was staying with a relative whose house happened to be on the main highway, very close to the place where the terrorists ambushed me. He had heard rumours floating around about the plan the previous evening, but was scared stiff to move out or to do anything about it, like sending word to the 19 Infantry Division HQ, about half a kilometre from there. I asked him why he had kept silent for so long. ‘It was due to remorse and a feeling of guilt, but I prayed for you,’ he replied. He wrote a letter describing the incident which is given in Appendix 1.

While conducting another operation, one of my sub-unit commanders had an interesting experience. As Ravi (name changed) and his boys were passing by a small hamlet they noticed that someone peeped out and then closed the window. There appeared something suspicious and unusual about it. Quickly, that area was encircled and Ravi knocked on the door. After a few minutes, a terrified old woman opened it and asked, ‘Who are you? What do you want?’

Ravi identified himself and demanded to know if there was anyone else in the house.

‘Only my daughter-in-law,’ she stuttered unconvincingly, pointing to a corner of the dimly lit room, where a young woman sat huddled up. Even in the poor light, Ravi could see her petrified look; she had fresh henna patterns on her hands.

‘You have my word that no harm will come to you, but I have to search this place,’ said Ravi with authority.

Quickly his men positioned themselves around the house, and the nominated search party commenced their job. Within five minutes they located a small hideout under the floor, accessible through a trap door, which was covered by a worn-out rug. When challenged, out came a nervous young man with his hands raised above his head.

‘Why were you hiding there?’ demanded the major.

‘Sahib, mujhe maut ka khauf hai (I was scared for my life)’, he cowered in fear.

‘What is your name?’ asked Ravi.

‘Abdul Majid, sir’, he replied, shaking.

Ravi took out his notebook to check his list, which confirmed his suspicions. When confronted with information about his terrorist background, Abdul Majid broke down and fell at the major’s feet, seeking forgiveness.

The old woman, in a state of shock, began sobbing. Regaining her composure after a few moments, she came up to the major and touched his chin as a gesture of respect and deference. ‘Sahib, don’t take him away. He is my only son and his “nikah” was done only a few days ago. Take pity on this young bride,’ she implored. The girl looked stunned and slowly slid to the ground.

‘Mother, tell him to be honest and to cooperate. I assure you of his life and safety’, said Ravi to the woman.

‘He will, he will; and may God bless you,’ she responded.

Abdul Majid went up to the first floor of the house escorted by a soldier and took out his AK-47 alongwith four fully loaded magazines. These had been cleverly concealed in the attic. Giving them to the major, he said, ‘Sahib, this is all I have. Though I had gone across the border for being trained for jehad, khuda kasam, I have never taken part in any action against the security forces. I have never used this gun! I am innocent – I swear by Allah.’

‘Do you know the way to Shera village through the forest,’ asked Ravi.

‘Yes, sir’, replied Abdul Majid.

‘Okay, then come with us, and quickly guide us to that place.’

He couldn’t be late and delay the mission of the entire battalion. He had to make up for the lost time. Grabbing Abdul Majid by the arm, he led him out of the house.

‘Don’t take him away, he is innocent. Have you forgotten your promise, Major Sahib?’ begged the old woman.

‘Ammi, I am a man of my word, and take pride in this uniform that I am wearing. Your son will not be harmed. We in the army are responsible and humane. I am sure he shall be forgiven for taking up arms against the state, provided he promises to mend his ways. Also, for the sake of this bride of a few days, he is not going to be sent behind bars! He will be back by the evening’, assured Ravi. Before leaving the house, Ravi asked the accompanying policeman to take an all-clear certificate from the two women so that there would be no scope for false allegations later on. When I was informed of this incident, I ordered that the gun should be confiscated and the young man be let off with a stern warning. This action brought us a lot of praise and the goodwill of the people.

In another action during the month of February, I was accompanied by the GOC, Major General Inder Varma. We walked in the snow the whole night and cordoned off two villages with one battalion each. One of these was Khaitangan. The next morning nothing happened till about 9 a.m. So the GOC decided to go back to his HQ. He must have barely reached when one of my battalions hit a gold mine. They discovered two terrorists holed up in a hideout in one of the villages and on being interrogated they told us that there were about ten of them hiding in different places. So the search was intensified. I was addressing the menfolk who had been asked to congregate in the school compound, when a police inspector whispered to me that a serious development had occurred in an adjacent area, and that it needed my attention urgently.

On reaching the spot indicated by the inspector, I saw a bizarre scene. In an open ground there was the second-in-command of 8 Bihar flanked by two terrorists with AK-47s slung on their shoulders and a grenade each in their hands. While we had cordoned off the entire area, Lieutenant Colonel Harjit Singh was taken hostage right in the middle of the village by two fanatics who were ready to commit mayhem and were prepared to die. They conveyed that they would like to negotiate with none other than the brigade commander. They were tall, smart and a bit cocky in their attitude. But I must admit that I was impressed by the cool approach of Harjit Singh. If anyone had panicked, the outcome could have been catastrophic. Standing out of grenade-throwing range, about 50 metres away behind a hedge, I conveyed to them through Captain Shakeel Ahmad, a brave officer of the battalion, that their entire gang had been caught but in case they let go of the officer, they would not be harmed. They asked for some water and a bottle of water was placed near them. Both of them surveyed the deployment of troops all around them and must have realized that there was no way they could escape.

In the meanwhile Lieutenant Colonel Harjit Singh somehow broke away from their clutches and joined us.

The terrorists spoke to each other and all of a sudden lobbed the grenades in my direction and opened fire with their Kalashnikovs. We dived and hit the ground. The grenade splinters flew all around us and bullets whizzed past overhead. Fortunately, the brunt of the attack was taken by the embankment in front of us. Our faces and bodies were splattered with the melting snow and mud which flew in all directions when the grenades burst. I had a feeling that I had been hit by splinters but luckily it was only muck formed by the melting snow and mud. Both the terrorists were killed in the shootout that followed their suicidal attack. Once again I appeared to be the target, and was lucky to survive. There were no other casualties. Captain Shakeel Ahmad and a few others from 8 Bihar were decorated with gallantry awards for this operation. Till this day I have not been able to fathom the reason for the terrorists’ refusal of my offer of a safe passage.

I cannot help writing about a notorious terrorist guide, Fatta Sheikh, from Maiyan village, close to the LoC in the Lachhipura sector. In an operation conducted in Baramulla area, we apprehended a suspect hiding in a cattleshed. Inside that dark shed there were scores of sheep huddled together. It would have been impossible to spot someone lying on the floor, but for the ingenious method devised by a JCO of 2/11 GR. He got hold of a long bamboo pole and started combing the shed by sliding it along the floor. At one place it hit some obstruction and he realized that there was someone hiding there. He warned in a loud voice that he would shoot if the person didn’t come out. Lo and behold! a man stood up with his hands raised. He was taken to the CO, who asked him a few questions. Fatta Sheikh’s alibi was that he was a gujjar (a nomadic tribe of herdsmen) and that it was his occupation to take the cattle of various owners for grazing in the higher reaches of the mountains every summer. He told his captors that he had come to return the cattle and take his wages from the villagers. He was innocent and he hid himself in the cattleshed out of fear, because of the army crackdown.

The CO was not aware of his background and was about to let him go. I was informed about it, but the circumstances under which he was caught rang a bell. When I was told that his name was Fatta Sheikh, I enquired if he was from Maiyan village. ‘Positive,’ said the CO. Then I told the colonel that we had been looking for this man for almost a year. He was a notorious crook and a mercenary who had guided more than thirty terrorist groups across the LoC. He was a storehouse of information regarding infiltrators and their Pakistani mentors. Only when he was threatened with dire consequences did he admit his involvement. He also dug out a few weapons wrapped in a polythene sheet that he had buried in a forested area near his village. He was handed over to the police and convicted for his criminal activities. His neutralization was a big blow to the activities of the terrorists in the Lachhipura sector. Fourteen years later, during a visit to Uri as the army chief, I met Fatta Sheikh. ‘Abhi bhi badmaashi karte ho?’ (Are you continuing your misdeeds), I asked. ‘Nahin Jenab’ (No sir), was his reply. I gave him a shabash, a pat on the back, alongwith a gift.

In my tenure of two years as the brigade commander of 79 Mountain Brigade, we conducted between 150–200 operations, both big and small, and got good results. We helped the locals make a jeepable road upto Lachhipura from the Uri highway. During this period we lost only five soldiers, whereas we killed over 130 terrorists and apprehended 870. Around seventy-five terrorists surrendered with their AK-47s. Overall, we had recovered 565 weapons and a large number of rockets, grenades and many thousand rounds of ammunition. We did our best to ensure that no innocent was harmed. It was an act of faith for us. Our iron fist was only for the foreign mercenary terrorists and hardcore militants who spread ‘dahshat’, or terror, amongst the populace. My brigade received seventy-one decorations during this tenure, including one Kirti Chakra, one Shaurya Chakra, eight Sena Medals and over sixty commendations of the chief of army staff and the army commander. Our brigade and the 68 Mountain Brigade were undoubtedly the top achievers of Northern Command during 1991–92, when insurgency in J&K was at its peak. Four battalions that served under me in the brigade, namely, 17 J&K Rifles, 2/11 GR (SHINGO), 15 Punjab (Patiala) and 7 Rajputana Rifles, were awarded unit citations by the chief of army staff for their outstanding contribution to peace in the valley during this period. In addition, 15 Punjab had the unique distinction of also being awarded the unit appreciation of the GOC-in-C Northern Command – the only unit to get both.

Based on my performance as a brigade commander, and my overall track record, I was selected to attend the highly regarded National Defence College course at the end of this assignment, and awarded the commendation of the chief of army staff.