CHAPTER ONE

ARCHAEOLOGY AND POPULAR CULTURE

Archaeology is as much a set of experiences ... as it is a body of methodological principles or techniques.

—Michael Shanks (1995: 25)

Archaeology is a field that fascinates many in the contemporary Western world. People love to study it, read about it, watch programs about it on TV, observe it, either in action or in exhibitions, and engage with its results. Moreover, we are all surrounded in our lives by colorful archaeological sceneries appearing in tourist brochures and on billboards, in cartoons and movies, in folk tales and literary fiction, in theme parks and at reconstructed ancient sites. Seen in this context, archaeology is less a way of accessing foreign and distant worlds, removed from us in time and often also in space, as it is a valued part of our very own world. Arguably, the “archaeological” has become so significant to our culture that archaeology can even be considered as a Leitwissenschaft of our time, an academic discipline that guides our age (Schneider 1985: 8; see also Borbein 1981; Ebeling 2004).

Although it may be a fairly small set of distinctive images of archaeology that nonarchaeologists enjoy and make their own, one of the reasons for the ubiquity of archaeology is that archaeologists not only dig in the ground but also in a number of significant popular themes (see also Shanks 2001; Wallace 2004). Often, archaeology acquires a metaphorical significance. It is some of these themes and metaphors that I shall explore in this book, for a study of archaeology as it is manifested in popular culture can also tell us a lot about ourselves: it reveals metaphors we think with, dreams and aspirations we harbor inside ourselves, and attitudes that inform how we engage not only with ancient sites and objects but with our surroundings generally. One of the aims of this book, then, is to make a contribution to the cultural anthropology of ourselves. I am asking how it is that archaeology and archaeological objects offer meaningful experiences and rich metaphors to the present Western world.

Collective Memories, History, and the Study of the Past

Archaeology draws some of its appeal and significance from its references to the distant past. The distant past is that beyond living memory, i.e., from the emergence of human beings until circa sixty to eighty years ago—a period during which many processes and events took place that we find today significant or interesting. Although nobody we could meet today was around at the time, our knowledge of the distant past can be said to be the result of a process of collective remembering (see Holtorf 2000—2004: 2.3).

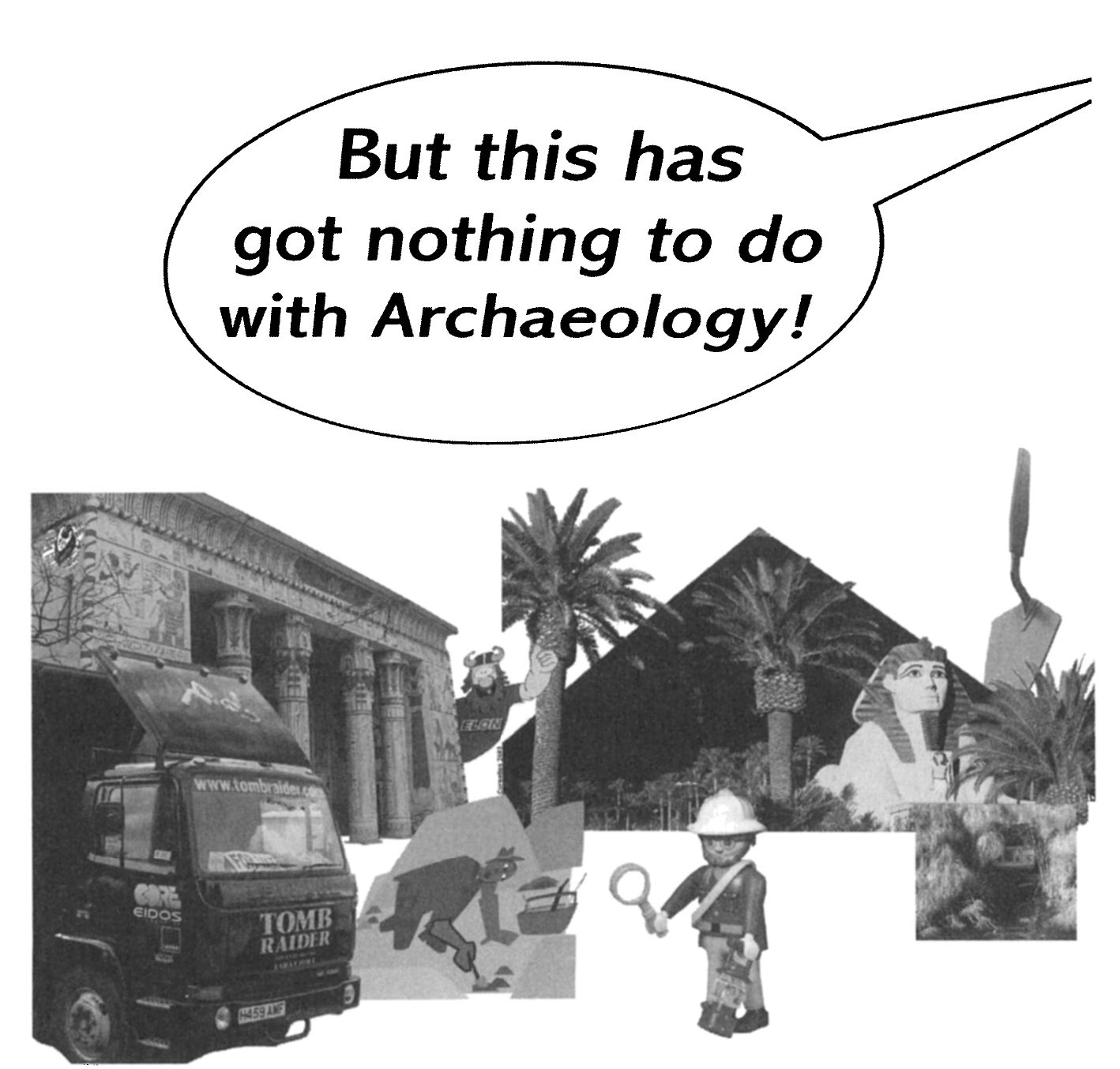

Figure 1.1 This book was written with a particular attitude towards archaeology. Naturally, not everybody will agree with me. Collage by Cornelius Holtorf.

Through memory we re-present the past, and this applies equally to our respective personal past and to that of our culture, region, or species. Recent sociological studies have tended to take the view that all forms of remembering, whether individual or collective, share a similar dependence on the specific social conditions of those remembering and are thus constructions of their respective presents (see, e.g., Thelen 1989; Fentress and Wickham 1992). Both kinds of memory rely on what we are reminded of or told, as well as on whom or what we trust, in certain situations, and both can acquire acute political and ethical dimensions. The distinction between personal and collective memory thus loses its sharpness and ultimately its relevance. More important are the precise conditions under which memories are constructed and the personal and social implications of the remembered pasts. As the historian David Thelen (1989: 1125) puts it in an influential paper titled “Memory and American History,” “In a study of memory the important question is not how accurately a recollection fitted some piece of a past reality, but why historical actors constructed their memories in a particular way at a particular time.”

This insight has become the basis for interesting work with and about people recalling events and processes of their own lifetime through the practice of oral history and studies in social remembering (Middleton and Edwards 1990). Similar attention is now being given to the social construction of collective memories of the more distant past. How, for example, dinosaurs (Mitchell 1998), human origins (Moser 1998), megaliths (Holtorf 2000-2004), the Celts (Pomian 1996), ancient Egypt (Frayling 1992; Malamud 2001), ancient Greece and Rome (Himmelmann 1976; James 2001; Dyson 2001), the Etruscans (Thoden van Velzen 1999), the Vikings (Service 1998a, 1998b), or the Middle Ages (Eco 1986: 61-72; Gustafsson 2002) are collectively remembered is increasingly attracting interest among scholars from numerous disciplines (see also the comprehensive collection of papers in Jensen and Wieczorek 2002). Such studies are not only illuminating as contributions to a better understanding of our own (popular) culture. The insights gained from them also have direct political and ethical bearings on how to engage with communities that remember their own past in terms different from those of the academics, both within and beyond the contexts of the Western world (see, e.g., Layton 1994). Even official policies regarding the preservation of ancient sites are relativized and increasingly being questioned (e.g., Byrne 1991; Wienberg 1999). It appears that the perspectives of academic archaeologists and heritage managers are simply manifestations of particular ways of remembering the past. There are alternatives.

Contemporary Realms of Memory

Between 1984 and 1992 the French publisher Pierre Nora edited a monumental work of seven volumes about the collective memory of France entitled Les Lieux de Memoire (realms of memory): “A lieu de memoire is any significant entity, whether material or non-material in nature, which by dint of human will or the work of time has become a symbolic element of the memorial heritage of any community (in this case, the French community)” (Nora 1996: xvii). Crucially, these realms of memory do not only include places (e.g., museums, cathedrals, cemeteries, and memorials) but also concepts and practices (e.g., generations, mottos, and commemorative ceremonies), as well as objects (e.g., inherited property, monuments, classic texts, and symbols). In effect, his books have become lieux de memoire, too (Nora 1996: xix).

According to Nora (1989: 19), all realms of memory are artificial and deliberately fabricated. Their purpose is “to stop time, to block the work of forgetting,” and they all share “a will to remember.” They are not common in all cultures but a phenomenon of our time: realms of memory replace a “real” and “true” living memory, which was with us for millennia but has now ceased to exist. Nora thus argues that a constructed history is now replacing true memory. He distinguishes true memory, borne by living societies maintaining their traditions, from artificial history, which is always problematic and incomplete and represents something that is no longer present. For Nora, this kind of history holds nothing desirable.

It is clear that archaeological sites, too, are places where memory crystallizes in the present, transporting the past into people’s everyday lives (see chapter 6). Although a specific study of archaeological realms of memory remains to be written, various contributions to Nora’s venture are discussing Palaeolithic cave paintings, megaliths, rock carvings, and the Gauls (Pomian 1996) as important archaeological lieux de memoire.

Moreover, Lawrence Kritzman suggests in the foreword to the English edition (Nora and Kritzman 1996: xii) that Nora’s quest in itself can be described as archaeological in as much as he and his contributors seek to uncover sites of French national memory.

The German historian Jörn Rüsen has over the past decade advanced an interesting argument with regard to history’s cultural significance. For him, history is “interpreted time” and encompasses all forms in which the human past is present in a given society (Rüsen 1994a: 6-7). This has two important implications that are both equally applicable to archaeology. First, history is not dependent solely on what really happened in the past but also on how it is remembered and actually present in people’s minds. The sense of the past is thus quite as much a matter of history as what happened in it—in fact the two are indivisible (Samuel 1994: 15). Later in this book, I will discuss how differently archaeological monuments, and by implication the past, are being understood in our own culture (chapters 5 and 6) and what may follow from an analysis of this variety for the management of ancient sites (chapter 8). Second, history is present in a whole range of human activities and experiences in daily life and not restricted to the content of books or lectures and the presence of ancient sites and monuments.

Thesis 1:

The important question about memory is why people remember the past in a particular way at a particular time.

Rüsen refers to this notion of history as Geschichtskultur, which might be translated as “history culture” or “culture of history” (1994b, 1994c). Rüsen’s notion of Geschichtskultur replaces the notion of an objective historical scholarship that could be independent from its cultural conditions and contexts. Instead, all manifestations of history in a given society, including those in academic forms, are equally considered to be elements of a certain “culture of history.” They function within different “theatres of memory” (Samuel 1994), and they deserve equal attention by historians. As a consequence, Rüsen’s students have investigated phenomena as diverse as historic memorials, history in advertising, and the significance of political commemoration days. This approach to history is similar to my own in relation to archaeology.

There is one important question that arises not only from Rüsen’s argument but also from the recent studies about remembering I mentioned. If so much emphasis lies on the past in the present, what are the implications for future academic research about the past?

As far as I am concerned, the practices of archaeology in the present are far more important and also more interesting than what currently accepted scientific methods can teach us about a time long past. Much of what actually happened hundreds or thousands of years ago is either scientifically inaccessible in its most significant dimensions, inconclusive in its relevance, or simply irrelevant to the world in which we are living now. Archaeology, however, remains significant, not because it manages to import actual past realities into the present but because it allows us to recruit past people and what they left behind for a range of contemporary human interests, needs, and desires. That significance of archaeology is what this book is about.

Professional archaeology consists of various present-day practices, including advancing academic discourse, teaching students, managing tourist sites, archives, or museum collections, and administering or investigating archaeological sites in the landscape. These practices are governed entirely by the rules, conventions, and ambitions of our present society and relate to its established values, norms, procedures, and genres. For example, research is valued in the form of completed publications and persuasive arguments, investigations in the form of comprehensive and informative reports, teaching in the form of cognitive- and social-learning outcomes, and management in the form of apparent care, efficiency, and accountability. Although all of these activities depict the past in some form, a time traveler’s observations about the degree to which these depictions relate to what it was actually like in the past remains largely irrelevant. Importantly, I am not denying the relevance of the past to the present categorically; I merely question the significance of accurately knowing the past in the present (see also chapter 8).

The only significant exceptions where the past matters more immediately today are archaeological studies whose results can be literally applied to present needs. A classic example is Clark Erickson’s applied archaeology research investigating the ancient “raised fields” in the Lake Titicaca region of Peru and Bolivia, which can help contemporary farmers develop techniques for growing crops on fields that now lie fallow (as discussed with Kris Hirst 1998). These agricultural projects will stand or fall, in part, with the quality of the archaeological science on which they are based. Other examples could be drawn from long-term predictions of environmental or evolutionary changes, which likewise rely in part on accurate knowledge available about past conditions and developments. In the overwhelming majority of cases, however, it is not what happened in the past that needs investigating but why so many of us are so interested in the past in the first place and what role archaeology plays in relation to that interest.

Why should anybody want to know how people actually lived their lives during past millennia? How can a profession excavating old “rubbish” gain scientific credibility, social respect, and a fair amount of popular admiration? Why do fairly arcane archaeological details and hypotheses interest anyone other than specialists? Why are so many ancient artifacts kept in museums and sites preserved in the landscape? How can it possibly be so important to try to “rescue” ancient sites from how we collectively choose to develop our land? In short, why do people love archaeology and the past it is investigating? To answer questions such as these, what matters are the meanings of the past in the present, how archaeological sites and artifacts relate to them, and the specific roles archaeology is playing in contemporary society and its popular culture. This book begins to explore some of these issues.

Archaeology in Popular Culture.

I need to say a few words here about what I mean by popular culture and how I will be studying it since this is a controversial field (for overviews see Maltby 1989; Storey 2001). For me, the most important aspect of popular culture is neither its popularity (some refer to “mass culture”) nor its homogeneity as a culture (“folk culture” as opposed to “high culture”). I like the way some German folklorists employ the term Alltagskultur (“everyday culture”), referring to whatever characterizes the way people live their daily lives and problematizing what is usually taken for granted (Bausinger et al. 1978). I also like a similar definition of popular culture offered by Raymond Williams (1976: 199), one of the fathers of cultural studies in Britain. He describes it as “the culture actually made by people for themselves,” thus excluding, for example, what they do for their employers. In this sense, popular culture refers to how people choose to live their own lives, how they perceive and shape their local environments through their actions, and what they find appealing or interesting. For example, Indiana Jones may not first come to mind when professional archaeologists consider what they do, but it is certainly high on the list of other people’s associations with archaeology (see chapter 3). Likewise, for professionals or others who spotted it, the “Khuza” culture may have been a cunning hoax around a collection of faked archaeological evidence, but for the unsuspecting public the exhibition represented nothing but yet another ancient culture with associated authentic artifacts (see chapter 7). Ultimately, however, the perceptions of the many matter as much, or more, than the factual knowledge of the few, especially since that factual knowledge, too, is not really privileged but simply based on one particular perception of archaeology, archaeological objects, and perhaps the world (see chapters 5 and 6).

Richard Maltby (1989: 14), a professor of screen studies at Flinders University, states that “popular culture is a form of dialogue society has with itself.” It expresses—and reproduces—our inner thoughts and emotions, our (supposedly) secret fears and desires, and our favorite habits and behaviors. Popular culture is helping us to recognize ourselves in the lives we lead. In this sense it is about actively producing culture as much as about passively consuming commodities (cf. Fiske 1989; Schulze 1993). Partly this culture is the same among very many people, but it can also be very diverse. In some respects, the culture people produce is diverse and dependent on whether they are rich or poor, well or poorly educated, but in other respects all may share the same culture. Sometimes it appears that people’s actions and preferences are highly predictable and manipulated, but at other times they are surprising and challenging. In this book I am not interested in developing such analytic distinctions (see, e.g., Schulze 1993) but in exploring one aspect of the richness of Western popular culture in its own right.

Adapting Williams’s phrase, one could say that I am looking at how people are actually making archaeology for themselves. This does not mean, of course, that anybody could actually make his or her own archaeology in complete isolation from what is already available, for example due to the productivity of archaeologists, writers, and producers. It rather means that in creating culture, all of us are constantly making significant choices, by preferring some ideas, sites, artifacts, texts, or images to others. These choices are not arbitrary but the results of values and attitudes that are largely acquired during socialization and reaffirmed by the choices of others (see Fluck 1987). Archaeologists, too, are people and make such choices, but since their own views of archaeology are abundantly documented in the academic and educational literature, I am focusing here mostly on nonarchaeologists. They are the people who surround me in my daily life, who read some of the same novels, watch some of the same TV programs, and visit some of the same tourist sites as I do, as well as some others. Most of them I will probably never get to know, but some I meet. In addition, I include the work and perspectives of a few individuals who, although not archaeologists themselves, have impressed me through their work on archaeology: they are academics from other fields, filmmakers, authors, or visual artists. I have been observing all these people and consuming their work with an anthropological approach, trying to understand meanings by attentively watching, listening, and reading.

My temporal frame of reference in this book is related to my own age and covers more or less the last two decades, with some excursions into the more distant past. My geographical scope is the Western world (see figure 1.2). It is very clear that the situation in other parts of the world would require an altogether different argument and other aspirations (see Byrne 1991; Shepherd 2002; Stille 2002). My own life has featured substantial episodes in Germany, England, Wales, and Sweden; I have traveled widely in Europe and been a few times to North America and other continents. Personal experiences in all these places have informed this work. Quite possibly, some of my argument will make sense in an area larger than where it originally derives from. Such is the impact of globalization that not only certain general themes but also some specific cultural items have spread widely.

There can be no doubt that some very powerful forces of cultural assimilation are at work across the globe. Their impact appears to be especially large where the commercial potential is large too, e.g., in TV programming and in the urban entertainment industries. But other, far less commercial phenomena, such as the spread of esoteric thinking, underline this trend too. It is therefore becoming more and more difficult to know precisely what may be American or Swedish or Welsh or German popular culture, and at the same time it becomes less and less useful to try and split apart what is growing together. Regarding the various examples given in this book, I see therefore no great benefit from getting into the subtleties of precisely who owns or can relate to which element of popular culture. This is not to deny the continuing significance of certain cultural distinctions, for example those related to specific regional traditions and specific languages, or the widespread interest in maintaining such particularities, sometimes precisely by employing archaeological sites or objects. Here, though, I do not wish to explore the popular concepts of archaeology in specific Western cultures but the specific concepts of archaeology in Western popular culture.

Figure 1.2 The world of archaeology: places mentioned in this book. Drawing by Cornelius Holtorf.

How people have known ancient objects in their own terms is not a new topic but has been studied previously by scholars interested in the folklore of archaeological artifacts and monuments. Now contemporary understandings of the same sites are given equal attention. The anthropologist Jerome Voss (1987) and the folklorist Wolfgang Seidenspinner (1993), for example, both argued that popular archaeological interpretations featuring alignments of ancient sites in the landscape (so-called ley-lines), visitors from outer space, prehistoric calendars, computers, and astronomical observatories can be seen as the folklore of our age. Such interpretations are a part of what has been called “folk archaeology” (Michlovic 1990), and usually they rely on approaches and methods very different from those of academic archaeology (see Cole 1980). A number of archaeologists and anthropologists consider popular folk archaeology as a threat to the values and prospects of scientific archaeology in society. Kenneth Feder (1999), for example, spent considerable time and effort discussing the flaws of what he calls “pseudoscience.” He argued in detail that theories such as those about the exploration and settlement of the Americas after the indigenous populations and before Columbus, the sunken Atlantis, visits to Earth by ancient astronauts, dowsing as an archaeological method, and the literal truth of the biblical creation story are deeply flawed and ultimately even dangerous since they mislead people about the past and discredit modern science.

Archaeologists sometimes assume that people’s occasional indifference and apathy towards the true ambitions of academic archaeology are due to a void in peoples’ minds where knowledge and understanding should reside. In reality, what archaeology intends is often not education but reeducation for its own (dubious) purposes (Byrne 1995: 278). Michael Michlovic (1990) pointed out that patronizing reactions towards folk archaeology are merely the result of a perceived challenge to archaeology’s monopoly on interpretation of the past and the associated state support. It would be more appropriate, he argued, to understand the cultural context from which such alternative theories emerge and the genuine needs to which they respond. In other words, archaeologists should appreciate alternative approaches for what they are rather than for what they are not.

In a recent book about archaeology and science fiction, Miles Russell (2002: 38) observed it is astonishing that given archaeologists’ obsession with context in the past, they do not tend to be very knowledgeable about their very own context today: how their methodology and subject matter is perceived and what their role within society is widely thought to be. Yet, arguably academic archaeology owes its own existence and establishment to a widely shared popular fascination with archaeology, rather than vice versa. Folk archaeology can lead professional archaeologists to the actual social realities within which any kind of archaeology is practiced today. This book makes a contribution to understanding better these realities by investigating some of the themes and motifs that make archaeology thrive in the contemporary Western world.

The widespread popularity of archaeology and archaeological sites or artifacts has meant that they have entered many different realms and discourses, only some of which can be called academic. They range from folklore (Liebers 1986) to tomb robbing (Thoden van Velzen 1996, 1999) and from contemporary art (Putnam 2001) to alternative “sciences” and religions (Chippindale et al. 1990). (Pre-)historical novels are a further example. It has been suggested that they do not simply fill in the gaps left in academic archaeological reconstructions but constitute their own meaningful universe (Wetzel 1988). Novels can thus usurp the very procedures and status of archaeology itself, effectively assuming its place in certain contexts. In this view academic archaeology is one of many systems of meaning, none of which has a monopoly on “reality.”

Archaeology as Popular Culture

A second main aim of this book is to suggest a new understanding of professional archaeology itself, shifting the emphasis from archaeology as a way of learning about the past to archaeology as a set of relations (to the surface, gender roles, material clues, artifacts, monuments, originals, the past, among many others) in the present.

Currently, academics and many others tend to assume that archaeology is essentially about bridging the gulf between the past and present (see figure 1.3). Archaeologists use a wide range of (more or less) sophisticated techniques and methodologies in their research designs in order to make ancient finds and features “speak” and “give up” their “secrets” so that we can all learn more about the past. In this view, every generation of archaeologists builds on the existing body of knowledge and adds to it so that our knowledge of the past improves continuously. Archaeology thus appears as a specialized craft mastered by experts who enjoy considerable authority concerning past human cultures. Their supposed expertise lies in knowing the past and its remains, being able to explain long-term changes, and comprehending at least some of past people’s “otherness.” Traditionally, the archaeologists’ self-adopted brief is therefore that of the scholar who can supply answers to questions about the past but sometimes also that of the cultural critic, challenging familiar notions and apparent certainties in the present with insights gained about the past.

Figure 1.3 Two views of archaeology: (top) the gulf between past and present realities, with archaeologists seeking a bridge; (bottom) past and present as part of a single reality, with archaeologists and others celebrating it. Drawing by Cornelius Holtorf.

I wish to challenge the dominant view by undermining its very foundation. In discussing the popular elements of modern archaeology and a number of powerful archaeological themes, I suggest an alternative categorization of archaeology: from archaeology as science and scholarship to archaeology as popular culture. This change of allegiance, like others suggested previously (see table 1.1), is much more than a semantic exercise. As will become clear throughout this book, I am proposing a novel, general theory of archaeology rather than simply more theory for archaeology. I am arguing that archaeology can and should be seen in the context and, indeed, in the terms in which it is appreciated in contemporary popular culture. The widespread fascination with both the past and the practice of archaeology (what I call “archaeo-appeal” in chapter 9) is the ultimate reason and justification for why it exists in the way it does. The gulf my discussion bridges, if any, is thus not that between the present and a lost past but between professional and academic realms, on the one hand, and other, especially popular, ways of appreciating and engaging with the past in the present, on the other hand.

My argument is based on the supposition that archaeology, in all its various manifestations, does not offer a perspective from which our own present can be understood in the light of its past. Instead, archaeology offers a perspective from which the past and its remains can be experienced and understood in the light of our present. Similar positions have been advocated or implied by various other archaeologists (e.g., Wilk 1985; Shanks 1992; Tilley 1993; Barrett 1994; Schnapp 1996; Renfrew 2003), and it enjoys a certain currency also among historians and others (e.g., Lowenthal 1985). I found it nevertheless astonishing that according to a recent survey of more than six hundred historians (www.h-debate.com/encuesta/menu.htm, accessed October 1, 2004), as many as 56 percent agreed “quite” or “very much” with the statement, “All history is contemporary,” and 53 percent agreed only a little or not at all with the statement, “History is to know the past as it was.”

Table 1.1 Allegiances of archaeology.

| Archaeology as ... | Key references |

|---|---|

| science / scholarship | Feder 1999; common archaeological textbooks |

| academic discourse | Shanks 1990, 199b; Tilley 1990 |

| theatre / performance | Pearson and Shanks 2001 |

| politics | Tilley 1989a |

| management | Cooper et al. 1995 |

| craft | Edgeworth 2003; Shanks and McGuire 1996 |

| visual art | Metken 1977; Renfrew 2003 |

| popular culture | This book! |

Thesis 2:

Archaeology is mainly about our own culture in the present.

I suggest in this introductory chapter that archaeology is a much broader cultural field than the narrowly defined specializations the academic world suggest. Archaeology today plays a significant part in Western popular culture at large. It is largely about things that are familiar rather than foreign to us. In the following chapters I explore in some detail how “the archaeological” (Shanks 1995, 2001) manifests itself in our own daily surroundings and discuss what this might imply for the practice of archaeology as a subject and as a profession.

With a nod to Pierre Nora (see sidebar above), I might describe the subject matter of the present book as the realms of archaeology, les lieux d’archeologie. I will visit a range of particularly important realms of archaeology, assessing their significance within popular culture and reassessing professional archaeology in light of that significance. These realms include, among others, the sphere of the underground, the perils of fieldwork, the discovery of treasure, the study of traces as clues, the meanings of artifacts and monuments, the notion of authenticity, the belief in the past and past remains as a nonrenewable resource, and the general appeal of “the archaeological.” The first realm to be discussed is perhaps the most basic aspect of archaeological practice: its concern with what lies below the surface.