CHAPTER FOUR

INTERPRETING TRACES

Artefacts mean nothing. It is only when they are interpreted through practice that they become invested with meanings

—John Barrett (1994: 168)

Discovering material evidence in the present, which is then used to reconstruct events of the past, links detective novels, criminology, and Freud’s psychoanalysis with archaeology. Traces are taken as clues for the events that caused them. This chapter discusses this particular interpretation of material culture and how subtly contemporary artists and others have challenged it. These critics suggest that all material culture can be interpreted in many different ways. Its characterization as “clues” for understanding past human action is not at all self-evident but the outcome of very particular interpretations of the context and origin of (certain) things. In the end, the process of reading clues as such may be more important than what is actually understood.

The Archaeologist as Detective—The Detective as Archaeologist

It has often been argued that the archaeologist works like a detective. Massimo Pallottino (1968: 12), for example, describes this similarity in the following way:

If we were to compare the reconstruction of the past with a large-scale police inquiry or a trial, tradition would be the equivalent to the depositions of the witnesses, and archaeological data would represent the material evidence: the former eloquent and circumstantial, but not always reliable; the latter fragmentary, not always clear in meaning, but in themselves incontrovertible. In the hunt for clues, in the ingenuity required to fit them into place, in the effort to interpret them logically, archaeologists do in fact very closely resemble criminal investigators. They operate on the front line of historical research like true detectives of the past.

Both archaeology and criminology draw on seemingly incontrovertible material evidence, which is taken to provide significant clues as to what has really gone on. These clues are often provided by telltale traces left on the site. As anything might be significant, comprehensive documentation is of the utmost importance (see Pearson and Shanks 2001: 59-64). Archaeologists are trained and experienced in recording, studying, and interpreting such traces and routinely integrate the results of expert analysis. A wonderful recent example is the continuing analysis of the Ice Man and his equipment, found in 1991 in the Italian Alps and initially handled as a criminal investigation. New evidence regarding this unique, over-five-thousand-year-old find is still coming to light and is always widely reported in the media. The recent discovery of an arrowhead in his body suggests that we are indeed looking at a murder case. On the Discovery Channel’s Ice Man Web pages (dsc.discovery.com/convergence/iceman/ iceman.html, accessed October 4, 2004) you are even invited to search for clues yourself, come up with your own conclusions, and vote for your favorite death theory.

The archaeologist is thus the detective of the past. Like the detective the archaeologist solves mysteries and is often portrayed as creating light where there was darkness by finding clues and revealing truths (e.g., Ceram 1980; Traxler 1983; Knight 1999; cf. Schörken 1995: 74-75, 82). Both archaeology and criminology did indeed develop parallelly to each other during the second half of the nineteenth century. The genre of the detective novel, too, emerged at that time, and works in this genre have ever since frequently alluded to archaeology (see Neuhaus 2001). One of the most prominent examples for an archaeological detective story is Agatha Christie’s Murder in Mesopotamia (1994 [1936]), which is set on an excavation based on Leonard Woolley’s project in Ur in modern Iraq. Christie saw archaeology as a puzzle about the past and occasionally mentioned in conversations that there were obvious parallels between the work of archaeologists and that of detectives (Joan Oates, personal communication). Hercule Poirot is obviously inspired by archaeological methodology. For instance, at the end of his adventures in Mesopotamia, the archaeologist Dr. Leidner, after having been found out as the murderer, commends the famous detective with the words, “You would have made a good archaeologist, M. Poirot. You have the gift of re-creating the past (Christie 1937: 215). The detective Poirot thus becomes the archaeologist of a crime. Some archaeologists like Stanley Casson, Glyn Daniel, and Gordon Willey have also written detective novels themselves (Thomas 1976).

Thesis 5:

The archaeologist is a detective of the past.

Because of such correspondences between detective work and archaeology, it is hardly surprising that the services of archaeologists have occasionally been invaluable to police forces. Archaeological expertise relates to many areas of police work and criminology, including surveying large areas, digging up buried evidence, particularly human remains, and reconstructing facial appearances from the skull (see Hunter et al. 1996). The emerging field of forensic archaeology makes archaeologists not only competent experts but also gives them an immediate social relevance by contributing to the fight against injustice (cf. Cox 2001). The connections between archaeology and criminology do, however, go even further. As cited earlier, Pallottino compared archaeology with a court trial. Michael Shanks describes a similar archaeological court scenario as follows:

Archaeology is judiciary. The archaeologist is judge and clerk of the court. The past is accused. The finds are witnesses. As in Kafka, we do not really know the charge. There is plenty of mystery. Archaeology follows the process of the law: inquiry (the accused and witnesses are observed and questioned, tortured with spades and trowels); abjudication (the archaeologist reflects on the mystery and gives a verdict); inscription (the archaeologist records trial and sentence, publishes for record of precedence). (1992: 54)

This metaphor was made literal in a staged public inquiry about the meaning of the Cerne Giant in Dorset (Darvill et al. 1999). The giant hill figure was put on trial, as it were, in order to find out what we know about him, how we know what we know, and what it all means. In front of a packed audience, the inquiry took place on March 23,1996, in the Village Hall at Cerne Abbas. All was filmed by the BBC, who were keen to present the debate as a courtroom drama. Three cases were presented: that the Giant is prehistoric/Romano-British in origin; that he is of medieval or postmedieval origin; and lastly, that he is significant irrespective of age. Tim Darvill, Ronald Hutton, and Barbara Bender acted as advocates for the three arguments. In addition to making their own pleas, they each invited several expert witnesses to strengthen their cases. A panel of assessors steered the inquiry and coordinated cross-examination and third-party questioning of the witnesses. The audience functioned as the jury and finally voted, with a large majority favoring the case for a prehistoric/ Romano-British origin.

The Paradigm of Clues

In an often-cited essay, Carlo Ginzburg (1983) argues for the existence of an epistemological paradigm of clues that has developed since the second half of the nineteenth century across several of the humanities. Its origins, however, go back much farther and lie both in hunters’ readings of animal tracks and in early divination, which can be seen as reading clues about the future (Huxley 1880). Ginzburg thus established a connection between various fields that share an occupation with reading tiny clues in order to infer their causes. I have already referred to the way modern criminologists and literary detectives such as Hercule Poirot (or indeed Sherlock Holmes) use clues to bring criminals to justice. Another relevant field is art history. Giovanni Morelli developed a method by which unsigned paintings can be attributed to particular artists on the basis of seemingly insignificant details. He argued that the depiction of details such as earlobes, noses, fingernails, and toes follows learned techniques, which become unconscious and unquestioned routines and are thus far more indicative of a particular artist’s hand than more conspicuous characteristics that could have been deliberately copied. John Beazley later applied the same idea to the identification of the painters of red- and black-figured Greek pottery. His approach has been very influential in classical archaeology and still has followers today (see Shanks 1996: 37-41; Whitley 1997).

Physicians infer in a similar way from certain symptoms to the cause of a particular disease or pain, and Ginzburg has argued that the paradigm of clues in fact reflects a medical way of thinking. Indeed, both Morelli and Arthur Conan Doyle had been educated as physicians. The same is true for Sigmund Freud, who, in addition, was not only a fan of Sherlock Holmes but also knew some of Morelli’s writings (Zintzen 1998: 239). Freud writes on one occasion that in psychoanalysis, as “if you were a detective engaged in tracing a murder,” one should never “under-estimate small indications; by their help we may succeed in getting on the track of something bigger” (1961: 27). Freud, too, saw a direct analogy between the methods of Holmes, Morelli, and psychoanalysis, but unlike Ginzburg he also saw the relevance of archaeology in this context. Freud followed with great interest the excavations of his time in Pompeii and Rome in Italy, in Knossos on Crete, and in Troy in Turkey; he visited archaeological museums and was himself a collector of antiquities (see Bernfeld 1951; Ucko 2001). It is therefore not surprising that in his psychoanalytic work Freud compared early childhood with human prehistory, the remains and ruins of which are slowly suppressed and buried as time goes by. Just like an archaeologist recovers fragments of ancient civilizations through excavation, Freud considered the psychoanalyst to be able to locate and reveal, beneath layers of amnesia, the fragmentary memories and remains of the earliest childhood of a patient. Dreams and neurotic personality disorders were his favorite excavation sites (Kuspit 1989; Gere 2002; Thomas 2004: 161—70). Based on the fragments found, however tiny, the psychoanalyst can reconstruct entire emotional constellations. Famously, Freud writes in Constructions in Analysis that the occupation of the psychoanalyst resembles, to a great extent, that of the archaeologist:

The two processes are in fact identical, except that the analyst works under better conditions and has more material at his command to assist him, since what he is dealing with is not something destroyed but something that is still alive.... But just as the archaeologist builds up the walls of the building from the foundations that have remained standing, determines the number and position of the columns from depressions in the floor and reconstructs the mural decorations and paintings from the remains found in the debris, so does the analyst proceed when he draws his inferences from the fragments of memories, from the associations and from the behavior of the subject of the analysis. (p. 259)

Although Ginzburg did not refer to archaeology, it is clear that the discipline of archaeology has not only been influenced by the idea of inferring causes from clues but has shaped this paradigm too (cf. Zintzen 1998; Gere 2002). The example of Sigmund Freud shows that the paradigm of clues, which Ginzburg derives from medicine, can also be firmly linked to archaeology. It is worth noting in this context that even the archcriminological method of using fingerprints as decisive clues for identifying culprits unambiguously has as one of its origins the study of finger marks on prehistoric pots (Beavan 2002: 69).

Spurensicherung Art

In 1974 an exhibition in the German cities of Hamburg and Munich, titled “Spurensicherung,” brought a group of previously unconnected artists together. Spurensicherung is the process of “securing circumstantial evidence” and (as a noun) also is the German term used for the forensics department of the Police, which locates and records material clues found at crime scenes. In this case the term referred to a number of artists who shared an interest in material leftovers and recording techniques. Among them were Christian Boltanski, Paul-Armand Gette, Nikolaus Lang, Patrick and Anne Poirier, and Charles Simonds. Recently, others such as Mark Dion, Susan Hiller, and Nigel Poor (figure 4.1) have followed a similar direction in their work, and they too can be associated with the Spurensicherung theme (see Metken 1977; 1996; Schneider 1985; A. Schneider 1993; Putnam 2001).

For an archaeologist there are different possible reactions to artworks such as these. On the one hand, one might say that art is art and archaeology is archaeology. Neither Anne or Patrick Poirier nor Mark Dion nor, in fact, any of the other artists associated with the Spurensicherung art claims to be an archaeologist in the sense of wanting to advance our knowledge of what actually happened in the past. Despite the care and exactness displayed, this is not scientific practice, and no hypotheses or interpretations about any events in the past are actually being offered. The way they copy, or parody, scientific and especially archaeological methods would then have no bearing on the academic discipline of archaeology at all. There are, however, other ways of interpreting these works.

The works of the Spurensicherung can be taken as a criticism of archaeology as a scientific discipline: by seemingly adopting its forms but denouncing its content, Spurensicherung art is a plea against the “scien- tification” of our world (Borbein 1981: 50). Works of the Spurensicherung often express very personal associations, desires, or memories that have been buried and would be irretrievable by the application of the scientific meticulousness and diligence that is caricatured. But there are treasures to be discovered beyond “objective” knowledge, calling for alternative methods of recovery. To a certain extent, their value lies precisely in the fact that archaeology or any other science cannot lift them. In this sense, Spurensicherung art is something like antiarchaeology. It questions the authority of the archaeologists by pointing to the nonscientific, i.e., all those aspects of life that scientists may miss but that are even more elementary and significant. In this sense, these artworks constitute a powerful critique of archaeology and related disciplines voiced not through discursive writing but through material practice (Schneider 1993: 3).

Figure 4.1 Nigel Poor’s Month of December from her art project Found (1998). She writes (abbreviated from web.archive.org/web/20020302060905/http://www.hainesgallery.com/NP.statement.html): “On January I, 1998, I began a project called FOUND. It is a journal of time, the environment, and of myself. Everyday I took a walk to collect something outside—in streets and alleys, playgrounds and fields, gutters and lawns. The objects were clues to hidden worlds. It is as if each object had fallen from a story, and, in its finding, was plucked out of the obscurity of some invisible narrative. In this sense, the object became ‘evidence’ which deserved closer inspection. These lost objects—these dumb things—present a concrete if oblique account of a year’s day-by-day appearance, and disappearance, and in doing so catalyze a remembrance of one’s own passing of time.” Every print of her photographs has been branded by a letter-press stating the date and exact location of where the depicted object was found. Reproduced by permission.

Mark Dion

Mark Dion is an American artist who has been inspired by scientific practices in the natural sciences and, more recently, by archaeology. In some of his earlier works, Dion makes references to naturalists of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, who investigated natural history by exploring, collecting, and classifying exotic specimens in remote parts of the world. In particular, he parodied their working practices, both in the field and in the laboratory, as well as their resulting publications and the associated cabinets of curiosities they exhibited. One such work is entitled “The Taxonomy of Non-Endangered Species” (1990) and shows Mickey Mouse on a ladder in front of a shelf with labeled jars containing toy animals in alcohol. In another project, “A Meter of Jungle” (1992), Dion removed a cubic meter of soil from the Brazilian rainforest, moved it into the exhibition room, where he sorted and classified its content, and finally displayed his collection.

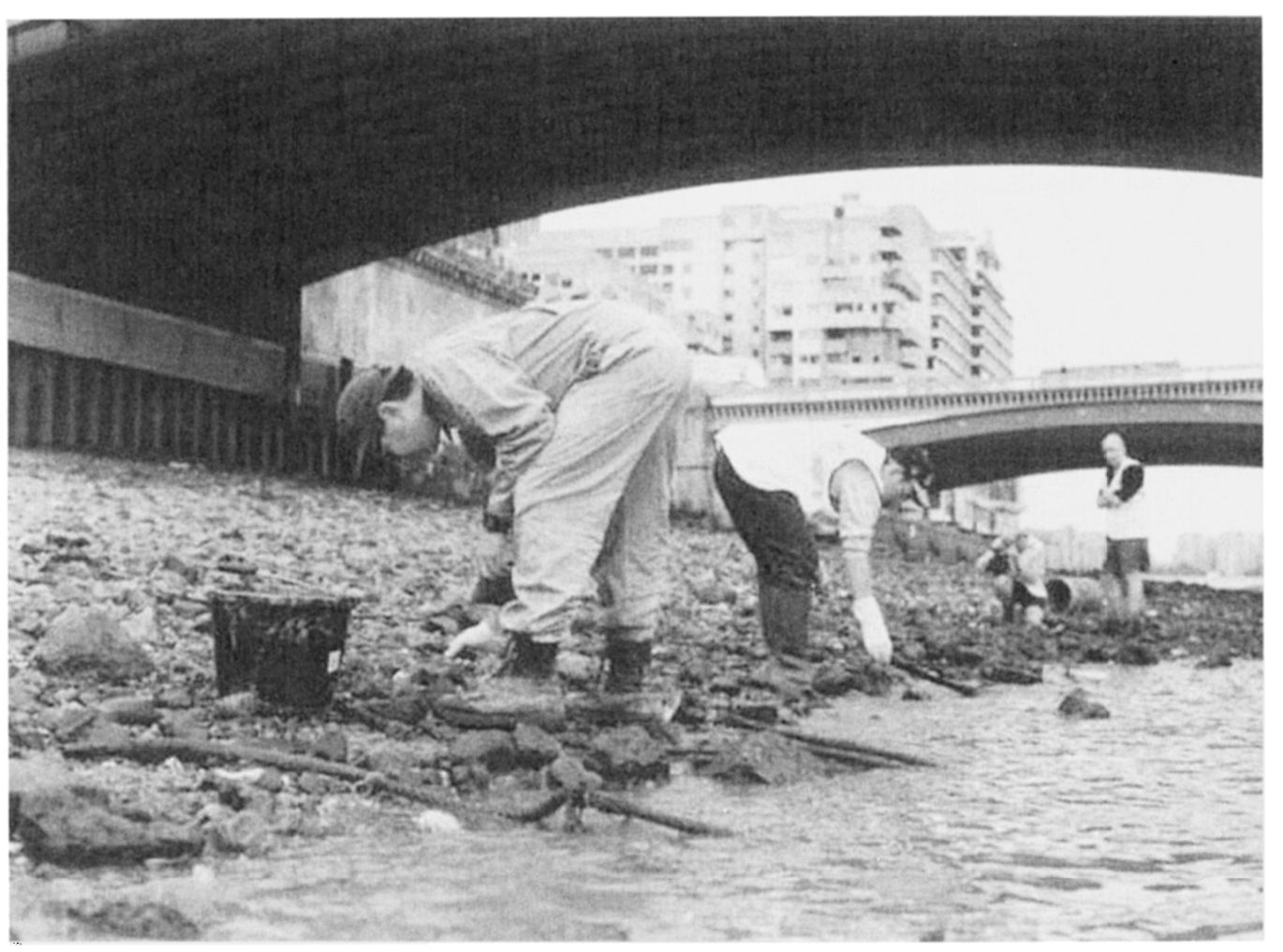

A quasiarchaeological site of the future was created in the form of a complete contemporary children’s room with a multitude of objects showing dinosaur images, entitled “When Dinosaurs Ruled the Earth (Toys R U.S.)” (1994). But Dion’s most archaeological works were his various “digs” for artifacts. One project, the “Tate Thames Dig” of 1999/2000, involved Dion and his team of volunteer field workers extensively beachcombing along the foreshore of the Thames River in London in the United Kingdom (figure 4.2). The objects found were then cleaned, identified, and classified, all taking place as a public performance outside London’s Tate Gallery. Finally, all finds (including bones, toys, broken glass, and credit cards) were systematically ordered and displayed in a large curiosity cabinet and five treasure chests inside the Tate Gallery. Dion once stated programmatically, “During my digs into trash dumps of previous centuries I’m not interested in one moment or type of object, but each artifact—be it yesterday’s Juicy Fruit wrapper or a sixteenth-century porcelain fragment—is treated the same” (cited in Corrin et al. 1997: 30).

Sources: Dion 1997; Corrin et al. 1997; Coles and Dion 1999

Figure 4.2 Mark Dion and collaborators at the Tate Thames Dig, 1999. Photograph © 1999 by Andrew Cross, reproduced by permission.

Although the artists concerned may not always have intended it, the works of the Spurensicherung also demonstrate why the paradigm of clues is an illusion that depends on questionable premises and is ultimately of less use to archaeology or any of the other sciences mentioned than commonly assumed. Spurensicherung art portrays archaeology as discovery, documentation, recovery, classification, and description of material remains that are ultimately taken to reveal in themselves certain truths about the past. The act of securing and reading of material evidence as clues appeals to people precisely because of the immediacy of the physical artifacts involved (figure 4.3). Material clues seem to connect a contemporary audience directly with the particular individual who once left them behind. As Mark Dion explains in a January 6, 2002, newspaper article in The New York Times regarding a new “digging” project of his, “A fragment of blue-and-white willow export porcelain thrown away in 1894 lies inert for 107 years until someone from the dig team finds it, creating a momentary bridge to the person who lost or threw the object away.” This not only creates a sense of aura and authenticity (as discussed in chapter 7) but also an admiration for the archaeologist who can make such things “speak” and bring the past back to life. It is, however, a mistake to believe that an archaeologist, or for that matter a criminologist, can immediately reconstruct the past from simply collecting, recording, and classifying some material remains and traces that function as clues. What are really only the first few steps of the interpretive process, the Spurensicherung art seemingly takes as its ultimate aim, thus failing to appreciate what archaeologists actually do (as argued by Schneider 1985, 1999; Flaig 1999). This is plain for all to see in that the final outcome of Spurensicherung works are generally collections of artifacts rather than any specific claims about the past, and that becomes very clear, for example, in the archaeological models and documentations produced by the artists Anne and Patrick Poirier (see sidebar below). Insofar as archaeological assemblages of artifacts remain mere collections of material evidence, they, too, fail in becoming meaningful in relation to what happened in the past.

The Spurensicherung ignores the fact that after an archaeological find or feature has been perceived and classified as such, both already acts of interpretation (see Holtorf 2002), it needs to be assessed further as to its meaning and significance in the given archaeological context. All of these are interpretive processes that depend on the approaches, methodologies, and research interests of the archaeologists in the present. This is a central insight of a recently developed approach known as “interpretive archaeology” (e.g., Tilley 1993; Thomas 1996: 62-63). The British archaeologist John Barrett (1994: 71) put its core idea very succinctly: “Our knowledge is not grounded upon the material evidence itself, but arises from the interpretive strategies which we are prepared to bring to bear upon that evidence.”

Figure 4.3 Nostalgia for the present in David Macaulay’s drawing gas Station (1978). Plate from great Moments in Architecture, © 1978 by David Macaulay, Reprinted by permission of Houghton Mifflin Company. All rights reserved.

Anne and Patrick Poirier

Anne and Patrick Poirier were both born in 1942, and their later art was strongly influenced by their having grown up in France after the devastations of World War II. The experience visiting in 1970 the ruins of Buddhist temples in Angkor in Cambodia led them to become interested in the concept and idea of archaeology. Since then Anne and Patrick Poirier have been calling themselves archaeologists, and their work has circled around two related issues: the fragility and destruction of cultures and civilizations, and the importance of collective memory. As Anne Poirier put it once in a discussion in 1998: “Our work is about the possibility of the past and the impossibility of the future.”

A good example of their work is Ostia Antica (1971-1972), based on an extended visit of the archaeological site that was the harbor of ancient Rome. This work consisted of several parts: first, a large (three-meter-long) plan of ancient Ostia, based on their own explorations, that resembles (but is not identical to) an archaeological site plan; second, a large miniature model of the ruined town (eleven by six meters) based on the plan and their own memories; third, a series of impressions of house parts and walls; and finally, several notebooks containing descriptions of their experiences, as well as a few pressed flowers and some soil. It is immediately obvious that the piece does not attempt to reconstruct the ancient site but rather serves as a kind of rebirth of the ruined town in the present. The aim is not to record objectively an archaeological site or to teach us anything about ancient Ostia, but to document meticulously a very personal experience of the remains of this site and thereby to provide a commentary about issues such as aging, decay, and remembrance.

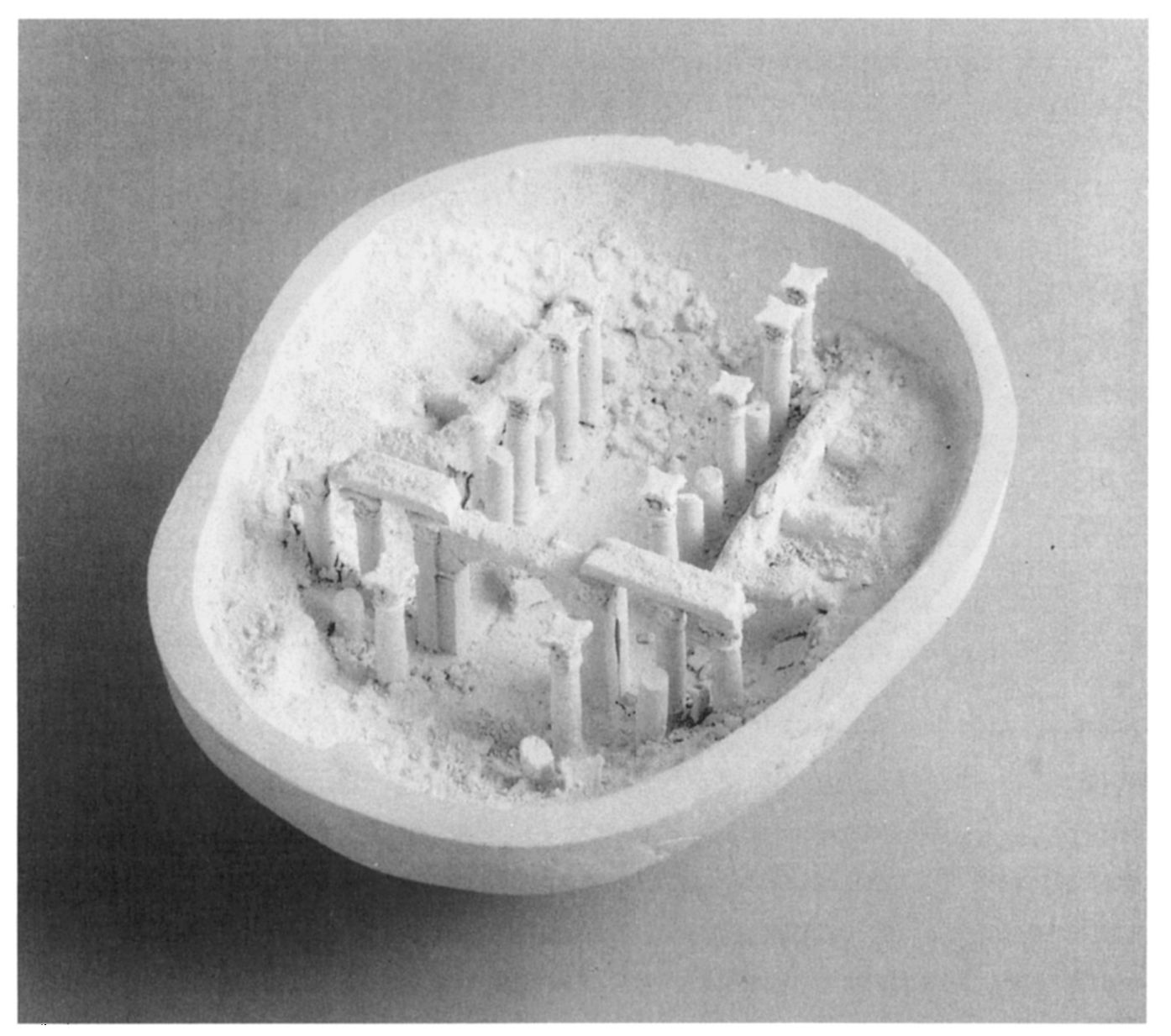

Similar ideas were evoked in several, more recently completed, large works by the Poiriers, which were devoted to Mnemosyne, the ancient goddess of memory and mother of the nine muses. Influenced by Mnemosyne’s significance to Aby Warburg, these works make reference to the idea of a library and express an architectural understanding of memory in the brain. On the occasion of the opening of one of the Mnemosyne exhibitions, a card invited guests to “the presentation of the latest archeological finds made during the excavation 1990-1991 on the site of ‘Mnemosyne.’” This presentation was said to draw on the enormous collection by an anonymous architect/archaeologist of documents, photographs, fragments and remains, plans, notes, and models from the site of Mnemosyne. One set of exhibits was called ‘The Archive of the Archaeologist’ and consisted of chests of drawers containing things like an image, a fragment, an illustrated journal, and a little model of a brain cut in half to show the remains of an ancient temple inside (see figure 4.4).

Sources: Metken 1977: 57-76; Poirier and Poirier 1994; Jussen 1999

The same could be said not only for hunters following tracks and detectives following clues but also for physicians acting on the basis of symptoms, psychoanalysts making much of remembered details, and art historians inferring from tiny divergences. In each case interpretation first creates the clues and then makes them significant in a particular way. In this sense the difference between traces and messages is much smaller than sometimes assumed. It is, for example, not always clear what is a trace, what is a message, and what is both. They each require equal amounts of interpretation to become meaningful. In the end all the hunter, the detective, the physician, the psychoanalyst, the art historian, and the archaeologist can offer are plausible interpretations that may or may not persuade others (cf. Veit et al. 2003).

In as much as the works of the Spurensicherung and the paradigm of clues generally imply a clear and undisputable relation between causes in the past and visible (recordable, collectable) effects in the present, they are misleading. Every clue can always be read in different ways, pointing to different causes. Thus, nothing may be more difficult to predict than the past, and the paradigm of clues is ultimately far less significant for under-standing the past than often assumed. What are significant, however, are particular contexts and discourses of interpretation (as discussed in the following chapters).

Archaeology as Process and Desire

Arguably, artists of the Spurensicherung tradition in any case do not wish to represent how archaeologists understand the past from its material remains. What appears to matter far more to them than arriving at a particular reconstruction are the first parts of that journey, which are characterized by a particular kind of thinking and experience. In this sense, the main reference point of the Spurensicherung is not the past but the symbolic act of remembering (Himmelmann 1976: 174). The works presented are modern constructions that cite archaeological method but ultimately make statements about their own present. As the art critic Günter Metken (1977: 14) puts it, the Spurensicherung is not the search for an original condition, but the ruins, remains, and traces provide an opportunity to define the artist’s own position in the present. As in the archaeological adventure of hunting for treasure (see chapter 3), it is not the final result that counts but the process the artist goes through to get there (Renfrew 2003: 103-6).

At the beginning of this chapter I cited Pallottino’s words about the similarities between archaeological research and criminal investigation. Significantly, he continues by speculating about whether it is the process of hunting for and interpreting clues that makes archaeology “so exciting to the general public, who derive such enjoyment from reading detective stories or following the twists and turns of court cases.” Could it therefore be that archaeology too makes a particular journey rather than seeks to arrive at a particular destination, that archaeology too is a symbolic act of remembering, which provides an opportunity for us all to define our own position in the present? Is archaeology only in a technical sense concerned with the past but otherwise concerned with present and future as the classical archaeologist Adolf Borbein (1981: 57—58) contemplated already more than twenty years ago? More recently, Barrett has expressed a related idea:

Figure 4.4 Anne and Patrick Poirier, Petit paysage dans un crâne. From the work Mnémosyne, Les archives de l’archéo/ogue, 1991. Source: Poirier and Poirier 1994, 160. Reproduced by permission.

There is no actual past state of history “out there” which is represented by our data and which is waiting for us to discover it.... All we have are the contexts of our desires to know a past, positions from which we may then examine the material conditions which others, at other times and from other perspectives, also sought to understand. We should treat this material as a medium from which it is always possible to create meaning, rather than a record which is involved in the transmission of meaning. (1994: 169-70)

Besides the creation of meaning on an excavation, archaeology as a present process has many other facets too. It springs from a will to know the past but can also involve the desire to collect antiquities or to save ancient sites from destruction, among other things (see Shanks 1992 for more!). As Gavin Lucas (1997: 9) states, to complete these processes would frustrate the very desires that lie behind it. The British archaeologist and author Paul Bahn confirmed this when he argued in an interview that it would be “a great pity” if we ever managed to understand all the secrets of the past (www.oxbowbooks.com/feature.cfm/FeatureID/76/Location/Oxbow, accessed October 4, 2004). Archaeology is not a question of needs being eventually fulfilled but of deeply felt desires being sustained. These desires can have erotic overtones (see chapter 2). The search for the past is at the same time the search for ourselves. As a consequence, we never quite know enough about the past, a collection of antiquities is never really complete, there are never nearly sufficient numbers of sites being saved, and often there does not even seem to be sufficient time for syntheses of what has been achieved already or at times for any publication at all. The archaeological process must therefore go on continuously.

Thesis 6:

The process of doing archaeology is more important than its results.

Incidentally, the same might be said for the processes of historical, criminological, and medical research, as well as for psychoanalytic treatment. Their benefit lies, at least partly, in seeing them continue, and not necessarily in any specific outcome. From a similar perspective, the American psychiatrist Donald Spence (1987) has proposed an alternative to Freud’s “archaeological” way of defining psychoanalysis by suggesting that it is actually more like a constant rereading of the same situation. This alternative might even have some relevance for archaeology itself:

In arguing for an accumulation of commentaries rather than the excavation of a session (or a person’s mind), we are saying goodbye to the archaeological metaphor and substituting something much closer to an open conversation. We are suggesting that wisdom does not emerge by searching for historical truth, continually frustrated ... by a lack of clear specimens and [biased] data; rather, wisdom emerges from the gradual accumulation of different readings of the same situation and the accumulating overlay of new contexts. Notice how the metaphor has changed. No meaning attaches to any one piece that is buried in the past, in the unconscious, or in the clinician’s incomplete records; no excavation is necessary. Instead, the meanings are constantly in flux, seen each time against a different context which provides a change of emphasis. (Spence 1987: 179-80)

Archaeology, too, can be taken to provide a collection of ever changing creative commentaries about the past and its remains. Each of these does not offer a contribution to an eventually complete reconstruction of the past, but they reflect the constantly changing approaches of those commentating. Arguably, this is precisely what the paradigm of clues has in practice always been used for. It may not have to offer any special opportunities to reconstruct the past, but it provides frameworks for following animals, convicting criminals, exciting readers, healing patients, and comparing paintings. In none of these cases does it ultimately matter whether (from the perspective of an omniscient observer) a certain trace has been understood correctly or not, as the reference to the trace as a clue for something else is already meaningful and suggestive in itself (figure 4.5).

It is precisely this engagement with material clues and associated commentaries about the past that accounts for much of the popular fasci- nation with archaeology. This may be one reason why the British TV documentary series Time Team, which has recently broadcast its tenth series, has been extremely successful for so long. Its normal format is a one-hour program documenting a three-day archaeological excavation at a chosen site. The highlights of each program are the moments when the presenter, Tony Robinson, gets called over to look at a newly discovered material clue and the subsequent discussion, which is often followed up by expert analysis about its significance in relation to what happened at the site in the past. The latest Time Team book (Robinson and Aston 2002) takes a similar approach, and its press release proclaims that “archaeology has never been so much fun. This book will inspire everyone to get out into their back gardens and start digging.” Archaeological programs on the Discovery Channel often follow this format, too. Another great example is the Amelia Earhart Project, a team of volunteers, both amateurs and professionals, including archaeologists, that devotes much of its time to the hunt for the remains of Earhart’s plane lost in 1937 in the Pacific, seemingly without a trace. The extensive account of their research so far is compelling, not because the mystery may (or may not) be solved but to a large extent because of the engagement with the materiality of the disappeared plane and its crew and with the kinds of clues that could be left of it and where (King et al. 2001; see also www.tighar.org/Projects/Earhart/AEoverview.html). In the end, therefore, archaeology and Spurensicherung art can find a common denominator after all. They do not share all the same practices nor, indeed, their main aims, but both offer commentaries about material remains of the past in the present. It could therefore be said that Spurensicherung is as much a kind of archaeology as archaeology is a kind of Spurensicherung.

Figure 4.5 Archaeology Kit on sale at UK heritage sites. This “Gift for Pleasure” from the company Flights of Fancy (www.flightsoffancy.co.uk) provides children with a fairly wide-ranging booklet about archaeology but mostly with the paraphernalia of archaeological practice: a trowel, a brush, some replica artifacts and a broken little vase that can be reassembled using the glue supplied. This pack is not about adventurous fieldwork or making great discoveries, but about exercising archaeological practices such as trowelling on the surface, brushing a find, reassembling a vase, and studying artifacts as material clues. Photograph by Cornelius Holtorf, 2002.

All of this should not be taken to imply that there have been (or indeed are) no other ways of interpreting ancient sites or artifacts than either as clues as to past human actions or as media to express various concerns of the present. The next two chapters therefore take a look at how dramatically the meanings of ancient sites and artifacts have changed over time and at the wide range of interpretations and meanings that can be found regarding them in various contexts of the present.