Security is not just about keeping people out of your network. Security also provides access into your network in the way you want to provide it, allowing people to work together. Strong network security opens up pathways to let people into your business, regardless of where they are located physically or what kind of connection they have. The tighter your security controls are, the greater the level of access that you can safely provide to trusted external parties, and likewise that they can provide to you. The higher the trust, the more access you can safely provide to external parties such as your customers, suppliers, business partners, vendors, consultants, employees, and contractors. That access encourages business while simultaneously streamlining operations to cut costs. Moreover, many customers and business partners demand a high level of trust before they consent to do business.

Security enables business. Good information security practices not only reduce costs but also tap into new opportunities for revenue. Security used to be thought of only in the context of protection. Today that view has evolved to focus on enabling business on a global scale, using new methods of communication. By improving access to the information that drives its business, every company can expand its business influence on a global scale, regardless of the company’s size or location. Modern security practices provide information to those who need it without exposing it to those who should not have it. Information is even more valuable when shared with those authorized to have it. The better the distribution vehicle, the larger the customer base that can be accessed. A secure data network allows a company to distribute information quickly throughout the organization, to business partners, and to customers.

Information differentiates companies. Companies may have confidential information, such as customer lists, credit card numbers, and stockholder names and addresses. Specialized information may include trade secrets, such as formulas, production details, and other intellectual property. Service organizations may have information about their customers that is not intended for public viewing, proprietary methodologies and practices that describe how services are provided, and data on marketing and sales.

Much of this valuable information resides on the corporate network, making the network a key business component. A data network does not simply enhance productivity—it enables the company to procure sales and serve customers.

Focused security efforts solve specific business problems and produce well-defined results. The costs of these efforts should be controlled and apportioned appropriately. A successful implementation of a security strategy proceeds in a controlled fashion, using a top-down approach to guarantee a coherent result that is consistent with the planned expectations. Successful security efforts that have been well planned and executed to solve specific business problems result in tangible benefits to the implementer.

One specific benefit of strong security programs is business agility. Good security practices allow companies to perform their operations in a more integrated manner, especially with their customers. By carefully controlling the level of access provided to each individual customer, a company can expand its customer base and the level of service it can provide to each individual customer, without compromising the safety and integrity of its business interests, its reputation, and its customers’ assets. Another benefit of good security is return on investment to the people who pay for it. Security is not just a cost center, it is an enabling tool that pays for itself in many ways. These benefits are described in more detail in the following sections.

Today, every company wants to open up its business operations to its customers, suppliers, and business partners, in order to reach more people and facilitate the expansion of revenue opportunities. For example, car manufacturers want to reach individual customers and increase sales through their web sites. Web sites require connections to back-end resources like inventory systems, customer databases, and material and resource planning (MRP) applications. Extranets need to allow partners and contractors to connect to development systems, source code, and product development resources. Yesterday’s goal of blocking access to these information resources is no longer valid in the new digital economy, and the rush to open up their networks is causing businesses to reevaluate their security needs.

Knowledge is power—in business, the more you know, the better you can adapt. Strong security provides insight into what is happening on the network and consequently in the enterprise. Weak security leaves many companies blind to the daily flow of information to and from their infrastructure. If a company’s competitors have better control of their information, they have an advantage. Security is a business tool to facilitate business processes. The protection of a company’s information infrastructure facilitates new business opportunities, and existing business processes require fewer resources to manage them efficiently when security is tight. Modern security technologies and practices make life easier, not harder. Security is an enabling tool.

Security allows a network to work more effectively toward the goals of a corporation because that corporation can safely allow more outside groups of people to utilize the network when it is secure. The more access you provide, the more people you can reach—and that means you can do more with less. Automation of business processes, made trustworthy by appropriate security techniques, allows companies to focus on their core business. Interconnecting productivity tools opens up new levels of operational effectiveness, and security enables these connections.

When appropriate security controls are put in place, businesses don’t have to reinvent the wheel each time a new extranet connection is added or a new web site is set up.

Modern security products and practices allow the creation of extensible architectures, which eliminate the need to design a new solution for each project. Instead of poking another hole through the security barrier for each new connection, a modern security architecture can account for interconnectivity requirements up front and avoid constant redesign.

Risk management is a very important benefit of security, because one of the primary goals of any security effort is to manage risk by mitigating it. Because of this, many companies think about security only in terms of risk management. However, risk management is not the only benefit of security. The flexibility allowed by a network of controlled interoperability provides revenue channels that add directly to income, such as a larger customer base and more sales opportunities.

Business partnerships that are made possible by a secure computing infrastructure provide another opportunity for revenue growth. Secure partnerships allow companies to expand their business interests and pursue new markets, which can lead to new revenue and can enhance the value of the company’s stock.

NOTE In justifying a security effort, first focus on the expected results. Second, attempt to quantify the benefits in monetary terms. Third, produce a simple statement of the expected return on investment (ROI), comparing the monetary benefits to the anticipated costs. This process will help streamline the budgeting process and will provide a foundation for measuring the security program’s success.

Information security is the essential foundation for adopting new network technologies and techniques. If you don’t have strong security, you can’t safely use new technologies until you get strong security. If strong security controls are in place, new technologies can be employed as they were intended in the business environment, with less potential for abuse and malfunctions.

When management strongly supports security, has a fundamental knowledge of security principles, and places a high value on security practices, the greatest gain is realized. Looking at security only as an expense is a mistake, because that perspective leads to reduction in security efforts, putting the company at risk and failing to take advantage of the benefits strong security can provide.

It is often important to demonstrate the value of an endeavor to those who pay for it. Justification of expenses is often expressed in terms of return on investment (ROI). A well-managed security program produces many benefits that justify its investment, and the ROI can be expressed in many different ways. Demonstrating the positive value of a security program can prove useful in obtaining funding, as well as quantifying its effectiveness.

CAUTION Historically, security efforts have been justified by the “insurance” analogy. This represents security practices as protection against loss but does not indicate the positive dollar value of security efforts. Rather, the insurance analogy represents security as a necessary evil, an unavoidable cost. In reality, well-managed security programs produce many valuable benefits that can, in fact, improve the bottom line of the balance sheet.

Quantifying information security as a risk management effort can be difficult. There are two ways to look at security: What does it prevent, and what does it enable? The preventative aspects of security relate to risk management, and the enabling aspects relate to business agility and, by extension, revenue growth.

How can we quantify business agility? Consider a web server. For companies that do business on the web, a web server is an essential business component. When a company buys a web server, it pays capital costs for the server and usually considers the server an expense without any revenue component. But without that web server, the business could not operate. So that web server can alternatively be viewed in the context of how much business it channels. For example, if $10,000 worth of business was transacted via that web server, and it cost $5,000, then its ROI can be construed as 100 percent. This reasoning could be applied to all essential network components in the revenue infrastructure.

Consider this reasoning applied to a firewall. One could certainly examine the number of attacks actually blocked in a defined time period, calculate the expected cost of those attacks if they were successful, and claim that the firewall saved the company that much money. But one could also quantify the value of the information that passed through the firewall, and claim that the firewall enabled that business to be transacted.

Every professional organization accepts two types of risks—those that the organization chooses to accept, and those that an individual in the organization has accepted without appropriate authority. Either way, the consequences of the accepted risks may not have been fully considered. Risk management is a process of deciding which risks to accept, which to mitigate, and which to transfer. Organizations that manage their risks position themselves to focus on their business objectives. Controlling risks leads directly to controlling costs, which shows up directly on the bottom line. Cost management is critical to profitability.

CAUTION Risk management is an important facet of security, but risk management consists of more than just Fear, Uncertainty, and Doubt (FUD). Focusing on the positive benefits of security that directly result in dollars on the bottom line is an important counterpart to risk management in justifying a security program.

Modern security practices reduce some costs, such as those due to loss of data or equipment. Risks to a business due to security failures can include more than just hacker attacks. Data lost due to mishandling, misuse, or mistakes can be very costly. A rampant virus, a downed web site, or a denial of service (DoS) attack often results in a service outage during which customers cannot make purchases and the company cannot transact its business. Perhaps even worse, the service outage may attract unwelcome press coverage. Loss of service can take a very large bite out of a company’s stock price.

Strong network security reduces the loss of information and increases service availability and confidentiality. Companies that monitor the activities and usage patterns of their network can better adapt to changing conditions and can better manage productivity. This provides greater flexibility to help management direct and channel resources toward the priorities of the company.

The consequences of a security compromise can be significant. A publicized security incident can severely damage the credibility of a company, and thus its ability to acquire and retain customers. Security systems do fail, and a good security program should acknowledge this. Every organization or individual can expect to pay a certain amount every year for losses due to security failures. Examples of costly security compromises include:

• Back door programs installed on internal systems protected by a firewall, that allow those systems to be accessed from the Internet right through the firewall without the owner’s knowledge or consent

• Workarounds by employees who are trying to find easier ways to do their jobs but that compromise the established security controls and allow unauthorized people to gain trusted access, such as dial-in modems installed by employees on their desktop workstations

• Misuse of company data and equipment by employees or other trusted insiders who are intentionally trying to obtain personal gain at the expense of the company or even to hurt the company, such as in the case of employees who sell the customer phone list to competitors, leak private documents to the press, or run private web servers on company equipment

• Unethical use of computer systems, notably viewing prohibited web sites on company time or in the presence of other employees who may be offended

Losses can range from unrealized gains because of missed business opportunities to writing checks for deductibles, liabilities, and settlements. Reducing the risks that lead to these losses can reduce their dollar cost. The probability of each risk becomes lower with the installation of security controls that minimize risks. Lowering the probability means that each risk event should occur less frequently and the number of security problems will be reduced. Fewer security problems means lower total cost associated with these security problems. Thus, improving security reduces costs.

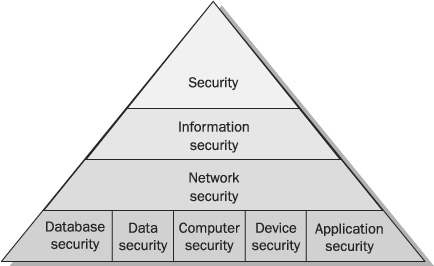

There are many branches of security. If you consider the field of security as a hierarchy, you have “security” at the root and many branches leading outward from that. For example, national security, information security, and economic security may be considered subsets of the entire discipline of security. Beneath those are more subdivisions.

In this book, we are considering network security, which is a subset of information security, which is a subset of security (see Figure 1-1). The field of security is concerned with protecting general assets. Information security is concerned with protecting information and information resources, such as books, faxes, computer data, and voice communications. Network security is concerned with protecting data, hardware, and software on a computer network. These definitions are important because they demonstrate the hierarchical relationship of network security in relation to other branches of security.

FIGURE 1-1 The hierarchy of security specializations

A focus only on the security of computers leads to blind spots that attackers might leverage to bypass the protective mechanisms employed on the network. It is important to consider network security in the context of its relationship to other security divisions, as well as to the rest of the enterprise.

CAUTION Do not skip the following sections. For many, a discussion of the assumptions and foundations of network security may seem less important than the details of specific technologies, but it is vital to the success of any security endeavor to consider the factors necessary for successfully integrating security technologies into the enterprise. For example, a firewall cannot be effective without paying attention to its context: the business processes used to support the technology, the assets it is intended to protect, the expected threat vectors, and the adjacent technologies that bypass the firewall. Keep the big picture in mind when wielding technological tools.

The field of information security evolves constantly, but the foundations of good security practice have not changed throughout history. If you are to succeed in protecting your assets, you must consider the lessons learned from successful security strategies, as well as those learned from poor ones. The basic principles apply equally well to any situation or environment, regardless of whether you apply them to defend computers, networks, people, houses, or any other assets.

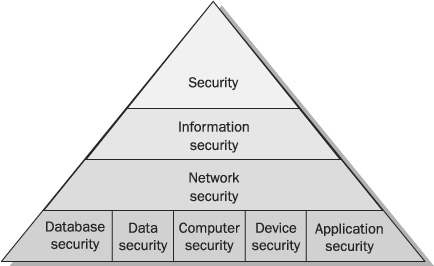

Three modes of security can be applied to any situation, and these are the three Ds of security:

• Defense

• Deterrence

• Detection

NOTE All companies spend money on security to a greater or lesser extent, but those that focus their resources in all three security modes reap the greatest results.

Defense is often the first part of security that comes to mind, and it is the easiest for people to understand. The desire to protect ourselves seems almost instinctive, and defense usually precedes any other protective efforts. Defensive measures reduce the likelihood of a successful compromise of valuable assets, thereby lowering risk and potentially saving the cost of incidents that might otherwise not be avoided. Conversely, the lack of defensive measures leaves valuable assets exposed, inviting higher costs due to damage and loss. However, defense is only one part of a complete security strategy. Many companies (perhaps most companies) rely only on a firewall to defend their information assets, and these companies are vulnerable because they are ignoring weaknesses in the other modes of security—deterrence and detection.

Deterrence is the second mode of security. Deterrence is the idea behind laws against breaking into and entering a house, assaulting another person, and entering a computer network without authorization—are all illegal and are punished with varying sentences and success. Deterrence is often considered to be an effective method of reducing the frequency of security compromises, and thereby the total loss due to security incidents. Without the threat deterrence offers, attackers who otherwise might have thought twice may go ahead and cause damage. Many companies implement deterrent controls for their own employees, using threats of discipline and termination for violations of policy.

The third mode of security, and often the least commonly implemented on computer networks, is detection. Relying on defense or deterrence, the security strategy often neglects the detection of a crime in progress. Many people consider an alarm system sufficient to alert passers-by of an attempted violation of a security perimeter (such as using an alarm for a house or car) and they rarely employ security enforcers, who are trained to respond to an incident, to monitor these alarm systems. Without adequate detection, a security breach may go unnoticed for hours, days, or even forever.

Comparing personal security to network security is a useful exercise. The principles of both are the same. In fact, network security relies on the same principles as any other branch of security.

Consider the three Ds of security in terms of a house. What would you do if you had something valuable in your house (such as a diamond ring) that you wanted to protect while providing controlled access? You would want to use all three modes. For defense, you would lock your doors and use modern key management technology to allow access to those you wish to authorize. For deterrence, you would expect your lawmakers to pass laws, and you might use other methods to discourage the theft of your valuables, such as keeping dogs or other intimidating pets. For detection, you might install cameras, infrared sensors, and other detection technology to alert you the instant a breach occurs.

Each of the three Ds is equally important, and each complements the others, as shown in Figure 1-2. A defensive strategy keeps attackers at bay and reduces internal misuse and accidents. A deterrent strategy discourages attempts to undermine the business goals and processes and keeps the corporate efficiency focused on productive efforts. And a detective strategy alerts decision makers to violations of policy. No security effort can be fully effective without all of these. Conversely, a security effort that employs all three Ds provides strong protection.

FIGURE 1-2 The three Ds of security

Defensive controls can include access-control devices such as firewalls, router access lists, static routes, spam and virus filters, and change control. These controls provide protection from software vulnerabilities, bugs, attack scripts, ethical and policy violations, accidental data damage, and the like. This type of control prevents unwanted activity on the network and forces network activity into channels that comply with the requirements of the business.

Deterrent controls include e-mail messages sent to employees reminding them of corporate acceptable usage and security policies, posted lists of Internet web sites browsed by employees on company-owned systems during business hours, employee communication and awareness programs to acquaint employees with ethics, codes of behavior, and acceptable usage of company computer systems and the consequences of failure to comply, and legal contract signatures on forms signed by employees indicating that they understand the conditions of the various security policies with which they must comply, and that their continued employment depends on certain conditions. These controls encourage compliance with the corporate security policy and help ensure that all network users are clearly aware of the expectations of corporate management and the consequences of inappropriate activity.

Detective controls include audit trails and log files, system and network intrusion-detection systems, summary reports reviewed daily by qualified personnel identifying web sites visited, successful and blocked attack vectors, and any other security-related information that is highlighted. It also includes presentations to senior management showing the effectiveness of the security program and identifying successes and failures.

CAUTION Do not employ only one or two of the three Ds of security. All three modes are necessary for a successful security program.

When only one or two of these modes of security are applied to the network, exposures can result. A network that only uses defense and detection without deterrence is vulnerable to internal attacks, misuse, and accidents caused by employees who are not motivated to follow the correct procedures. A network that fails to employ detection faces exposure to all failures of the defensive and deterrent controls, and management may never become aware of these failures, which means abuses may continue unchecked. Of course, employing no defensive controls on a network exposes that network to any of the well-known threats of internal or external origin.

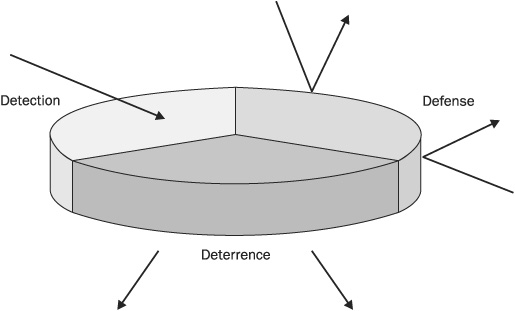

This five-step process, followed carefully in order, helps ensure that security efforts address important, specific problems in a controlled, effective manner and that security costs are well managed and appropriate to the values of the assets they protect.

Before undertaking any security effort, ask the following questions. This inquiry is part of the analysis phase that should be part of any implementation effort. These questions help define the business requirements and lead the implementer to a solution that fits those business requirements.

1. Assets What is to be protected? Identifying the assets that will be protected by security measures is a crucial first step in any security implementation. Failure to ask this question may lead to inadequate security controls, or security controls that protect the wrong thing. For example, when designing an e-commerce web site, asking this question may lead the designer to identify the following things as needing to be protected: customer names and addresses, credit card numbers, and web server availability. Encryption of the network connection, locating data on a separate database and encrypting that data, a firewall with denial-of-service protection capability, and redundant web servers are needed to protect these things. Failing to ask this question may lead the designer to forget about encryption, especially in the database, or redundancy, or denial-of-service filters. The answer to this question is a simple list of assets to be protected.

2. Risks What are the threat vectors, vulnerabilities, and risks? After the assets to be protected have been identified in question 1, the threats to those assets should be enumerated along with their possible sources. The vulnerabilities associated with the assets that might be exploited by the threats should then be discovered. The risks, which are the likelihood and cost of each realized threat, should also be identified. Together, these three factors provide information necessary to determine which security controls to consider, where they might be placed (for example, inside or outside the firewall, on the network, or on servers), and how much to spend on them (based on the expected loss identified in the risk analysis, it may not make sense to spend more money on a security control than the asset is worth, or the cost of a realized threat). The answer to this question is the result of a risk analysis.

3. Protections How will the assets be protected? Once the business requirements have been identified and documented as in question 1, and the risk analysis has been completed based on question 2, the security practitioner can then consider the actual policies, processes, and techniques that will be used to provide the appropriate level of protection to the assets against their associated threat vectors. The security practitioner can then be assured that they are well positioned for success in their security implementation. Some protections will be provided procedurally, that is, by providing users and administrators with instructions about how to conduct their business, along with appropriate enforcement. Some protections will be provided by defensive technology such as firewalls, access control devices, filtering software, authentication mechanisms, encryption, and the like. Other protections will be provided by detective and deterrent controls, such as monitoring software or manual monitoring by administrators, which is then used by Human Resources to correct employee behavior. The answer to this question is the list of general techniques that will be used to protect the assets.

4. Tools What will be done to ensure that protection? Given the broad categories of protections identified by question 3, a specific selection of tools follows. At this stage, a product evaluation takes place, usage policies are identified where needed, and procedures that must be documented are defined. The answer to this question is the list of specific protective steps that will be taken.

5. Priorities In what order will the protective steps be implemented? Once the tools and techniques to protect the assets from the threats have been identified, and assuming the organization does not have enough resources to implement everything simultaneously, priorities should be assigned to each tool and technique, so they can be implemented in a reasonable order. Turning on a web server before installing a firewall may not be a good idea; instead, installing a firewall first, then hardening the web server, then implementing encryption, then implementing a secure database, and finally turning everything on, may make the most sense. The details vary for each environment, but these five questions, asked in this order, help the implementer to consider all the factors that should lead to a successful implementation.

These questions and the order in which they should be addressed are diagrammed in Figure 1-3. This diagram shows how the focus progresses initially from identification of assets to be protected, from there to identification of the risks to those assets, from there to establishment of protections for the assets, from there to selection of tools to provide those protections, and finally to priorities.

FIGURE 1-3 Five-step program for a successful security strategy

The first step in any effective security program consists of identifying what assets need to be protected. This requires, at a minimum, identifying all assets involved in the network security effort. Enumerating the monetary asset values helps in managing the costs of security implementations and prioritizing security efforts. Though not always necessary in every environment, asset valuation provides important information to the security manager. Regardless of whether the asset identification includes values, identifying what needs to be protected is essential in ensuring that security controls are placed appropriately to provide correct and comprehensive protection of the appropriate assets.

The second step consists of identifying threats, vulnerabilities, and risks. Considering all the ways in which assets can be lost, damaged, or abused is a critical prerequisite to any security endeavor. Threat identification requires consideration of every possible way in which assets can be threatened. A vulnerability assessment provides information about weaknesses in the environment that can be intentionally or accidentally exploited to cause loss, damage, or abuse. A risk analysis enumerates the likelihood of each vulnerability being exploited by each possible threat. Security efforts that avoid beginning with a thorough risk analysis should at least identify threats and vulnerabilities. This information is required to ensure that security controls are well matched to the factors that put the assets at risk.

NOTE Threats can be considered in the context of “threat vectors.” A vector includes information about a quantity and a direction. A threat vector includes information not only about a particular source of harm but also about where it originates and what path it takes to reach the protected asset.

The third step consists of determining what should be done to protect the assets from the risks. This is the security policy. The security policy is necessary to clearly delineate management’s objectives for the security program, and how security controls will be utilized to accomplish these objectives. A security policy is the core of any security effort, and a documented policy lessens confusion and brings forward the important underlying assumptions that must be taken into consideration when designing a defense. The security policy describes what will be done and why, without the details of how. The precise implementation details are the procedures, and they are handled as a separate effort so the goals of management will not become mixed up with individual products or vendors. The security policy changes when the business environment changes or when management objectives change, but it does not change as frequently as the details of specific technologies.

The fourth step consists of identifying technologies, processes, and practices that can be used to implement the security policy. The details of specific technological solutions take the form of procedures, standards, guidelines, and specifications. These detailed designs deal with technologies, products, and environment-specific practices that constantly evolve, but they always conform to the objectives defined in the security policy. Because the tools identified in this step constantly change, the designs also change frequently along with the technologies.

CAUTION A firewall is a technological security control. Common wisdom states that every network needs a firewall and that firewalls are sufficient to protect network assets. However, firewalls do not address important threats, such as physical attacks and non-Internet attacks. Moreover, firewalls may not be appropriate in some situations. Security controls such as firewalls and other technologies (along with processes and procedures) should be considered within the context of each individual environment.

The fifth step consists of prioritizing the implementation of security controls by risk, cost, difficulty, and any other factors significant to the individual environment. No organization has enough resources, staff, and budget to do everything at once, so some security controls must be implemented first, and others must follow after. Implementing the most critical solutions first allows the organization to manage its resources effectively. After prioritizing the efforts appropriately, the implementation can proceed in a controlled, effective, and well-managed manner.

A security strategy is the definition of all the architecture and policy components that make up a complete plan for defense, deterrence, and detection. Security tactics are the day-to-day practices of the individuals and technologies assigned to the protection of assets. Put another way, strategies are usually proactive and tactics are often reactive. Both are equally important, and a security strategy cannot succeed with only one of the two. With only a strategy and no tactics, no active or passive defense provides protection. With no strategy and only tactics, security efforts will be confused and conflicting. With a well-defined strategic plan driving tactical operations, the security effort will have the best chance for success.

In an ideal organization, strategic planning and tactical operations are performed by separate people or organizations to avoid conflicts of interest. In that situation, the group responsible for the planning works with the operations group to develop solutions that are workable and practical, and the operations group provides requirements and developmental feedback to the planning group. Many companies choose not to separate these two functions and require engineering efforts to be performed by the same people responsible for keeping the network running on a day-to-day basis. In either situation, strategic planning should never suffer or be delayed due to lack of resources or attention. Likewise, the group should not focus on planning to the exclusion of applying practical solutions. A balance between strategy and tactics is required for a successful, timely implementation.

NOTE Dividing efforts between strategic (proactive) planning and tactical (reactive) operations can be challenging. However, both functions are equally important, and resources should be divided between the two. In extremely active environments, it can be helpful to set aside time each week for planning sessions that focus on the longer term.

Strategic planning can proceed on weekly, monthly, quarterly, and yearly bases, and should be considered an ongoing endeavor. Often there is an immediate need to secure a part of the network infrastructure, and time is not on the side of the strategic planner. In these cases, a tactical solution can be put in place temporarily to allow appropriate time for planning a longer-term solution.

In gauging the effectiveness of a security endeavor, separating strategy from tactics provides a way to focus on how business resources are being deployed. If a company finds itself focusing only on strategy or only on tactics, it should review its priorities and consider adding additional staff to address the shortfall.

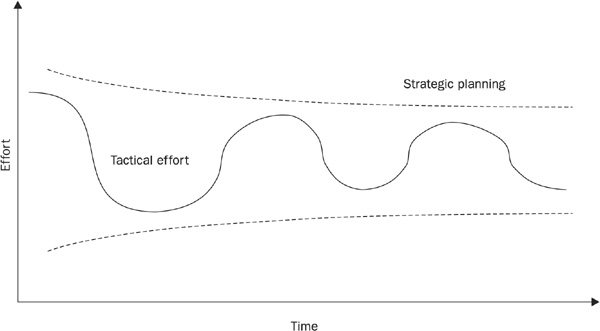

Figure 1-4 demonstrates the interplay of strategy and tactics. Initially, at a given starting point in time, tactical effort may be high where strategy has not previously been employed. As time progresses, and strategic planning is employed, tactical operations should begin to require less effort, because the strategy should simplify the operation and the business processes. This simplification is caused by the organization and planning provided by the strategic efforts, which reduce uncertainty and duplication of work by providing a proactive framework for staff to operate in. Given enough time, strategic planning should encompass tactics, confining them to the point where most daily tactical operations take place in a well-planned strategic context, and only unexpected fluctuations cause reactive efforts.

FIGURE 1-4 Strategy paves the way for tactics

In the ideal company, strategy and tactics are at equilibrium. The strategic focus paves the way for quarter-to-quarter activities, and the tactical operations follow the strategy set forth in the previous quarters. In this balanced system of planning and action, a framework has been set in advance by the strategists for the operational staff to follow, which greatly facilitates the jobs of the operational staff who must react to both expected and unplanned situations. Instead of spending time figuring out how to respond to day-to-day situations, the operational staff follows a largely preplanned set of responses and implementations, leaving them free to cope with unexpected problems. In the network security context, this allows a better focus on incident response, virus control, correction of policy violations, optimization of implementations, and the like. For example, the tactical security practitioner can be more free to respond to an unexpected hacker attack when incident response procedures and technologies have been planned in advance, instead of reacting on the fly and wasting valuable time during a crisis.

The practice of information security has changed dramatically over the last ten years. Since the networking of individual computers began in the academic environment and spread to government before the business world embraced the concept, the technologies that were developed were specific to academic and government environments. In the academic world, the goal was to share information openly, so security controls were limited to accounting functions in order to charge money for the use of computer time. In the government, the practice of information security is referred to as InfoSec, which has historically consisted of blocking most or all access to computers, controlling internal access to confidential data, and using Tempest shielding to prevent electromagnetic radiation from the computer being intercepted. This method of protecting assets provides a hard-to-penetrate perimeter, as shown in Figure 1-5. These practices continue to have their place in a comprehensive security strategy, but they are no longer sufficient to meet the needs of the modern computer network.

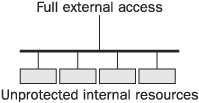

Originally the academic security model was “wide open,” and the government model was “closed and locked.” There wasn’t much in between. This is still true for many academic and government institutions because they have special requirements and because they have a history of resisting change. Figure 1-6 shows the security model for most academic institutions. Compare and contrast this model with the government model shown in Figure 1-5. Note that these two models are diametrically opposite—the government model blocks everything, the academic model allows everything. There is plenty of room in between these two opposites. Modern security technologies and practices can enable new security models for academic and government institutions, but evolution in these institutions takes time.

FIGURE 1-5 Government perimeter blockade model

FIGURE 1-6 Academic open-access model

In the field of computer security, academic and government institutions established practices that are still around today.

However, when e-commerce came along, a new model was required. A closed-door approach doesn’t work when you need thousands or millions of people to have access. Likewise, an open-door approach doesn’t work when you need to protect the privacy of each individual. E-commerce and business require the completely different approach of providing limited access to data in a controlled fashion, which is a much more sophisticated and complex approach than the previous security models. To use the house analogy, consider the complexity of allowing certain authorized parties (like utility companies, cleaning staff, or caterers) to get into your house while still keeping out burglars and vandals—it’s easier to keep all your doors locked or leave them all unlocked. Partial controlled access requires authentication, authorization, and privacy.

Modern security products are now designed to fit with the new role of security in the world of business on the Internet, allowing communication both inbound and outbound. The Internet has very quickly changed the way we do business, and approaches to protection have not yet become well established, so finding a product that meets the requirements of businesses that use complex internetworking can be difficult or impossible. The security practitioner is left to string together existing products that may not work well together, produce customized solutions, or compensate for a weakness in one of the three Ds with another (such as employing intrusion detection to compensate for weaknesses in operating system security controls, for example).

Network security is a cutting-edge field. It is possible that, one day in the future, the field of security will be streamlined to the point that principles and practices are well established and standardized, products work well and consistently, and management has clear expectations that are well met by the technology. However, in the foreseeable future, none of this will happen, and it seems equally likely that technological advances will always continue to outpace the mechanisms used to control the use of the technology.

The discrepancy between the leading edge of technology and the establishment of reliable controls is what makes network security challenging and fun. It is also what prevents security endeavors from being less than 100 percent effective, which is why layering security controls is all the more important.

CAUTION Many theoretical security models exist. Some of these are related to computer architectures and others are based on access to data. However, the security practitioner must live in the real world of evolving business and must try to secure brand-new technology, often just as new products become available. We often cannot pick and choose what technologies and practices are used on the network. We must instead be prepared to deal with any eventuality and must regularly come up with innovative solutions.

Obfuscation, which in the context of network security is defined as the process of hiding secret messages by breaking them up or burying them in an unexpected place can be effective if nobody knows where to look. This sort of obfuscation is one of the earliest methods of protecting confidentiality of data on networks, computer systems, and databases, and continues to be one of the most common practices for protecting data today. Techniques for searching, fingerprinting, and identifying secrets have advanced to the point where contemporary forms of obfuscation provide only an insignificant challenge if it is known that a secret exists. Safes can prevent a casual or inexperienced thief from stealing jewelry or other valuables, but the art of safecracking can undermine almost any safe.

The techniques of asset protection used in the home are similar to those used in computer networks. Firewalls are like barricades, encryption is like hiding things, computer systems are like safes, and obfuscation is commonly seen in encryption techniques used to store secret keys. These technologies have certain strengths against casual offenders, but they can be ineffective against determined attackers. Considering these techniques by analogy can provide insight into their shortcomings.

NOTE An asset is something that has value. It can be tangible (like a notebook computer or a credit card number) or intangible (like customer confidence).

Historical examples of strategic security successes and failures prove instructive. The Maginot Line, built between World War I and World War II to defend France from Germany, is one of the most famous defensive failures in history. We can say that the Maginot Line was a wall built as a strict border defense, designed to deny all access from the other side. It failed for several reasons, and Germany was able to go around and through the wall. This was due in part to lack of attention to alternative threat vectors (namely, the unfinished ends of the wall). In addition, a lack of follow-through in its construction and maintenance allowed the wall to lose its effectiveness. Finally, changes in warfare technology made obsolete a wall designed to block individual human attackers on foot. The Maginot Line serves as a useful analogy to modern firewalls. Ignoring the threat vectors that bypass firewalls (such as modems, VPNs, vendor connections, telecom) and failing to properly maintain the firewall platform and configuration can reduce and weaken the firewall’s defensive effectiveness.

The Greek Trojan horse is another historically famous defensive failure, and it provides an important lesson in trust. In the story, Odysseus built a large wooden horse in an effort to gain entrance to the Trojan stronghold. Soldiers hiding inside the wooden horse killed the Trojans after the horse was brought inside their defenses. Because the Trojans relied on their perimeter defense to protect them, they could not defend against an attack from the inside. Contemporary Trojan computer programs create the same type of breaks in perimeter defense, and they enter via trusted channels.

The basic assumptions of security are as follows:

• We want to protect our assets.

• There are threats to our assets.

• We want to mitigate those threats.

These hold true for any branch of security.

Security is a paradigm, a philosophy, and a way of thinking. Defensive failures occur when blind spots exist. A defender who overlooks a vulnerability risks the exploitation of that vulnerability. The best approach to security is to consider every vulnerability in the context of its associated risk and the value of the asset at risk, and also to consider the relationships among all assets and vulnerabilities. Historical and modern analogies can help expand your awareness of weaknesses in the security infrastructure and can reduce blind spots in the security strategy.

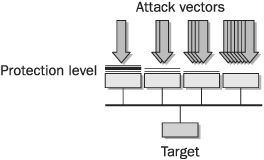

A basic tenet of security, regardless of the application, is that the job of the attacker is always easier than the job of the defender. The attacker needs only to find one weakness, while the defender must try to cover all possible eventualities, as shown in Figure 1-7. The attacker can resort to destructive practices, but the defender must keep their assets intact. To illustrate this point, let’s return to the house analogy. A homeowner who wants to protect their property must try to anticipate every attack that is likely to happen, while an attacker can simply use, bend, break, or mutilate the house’s defenses. In an extreme case, the attacker can knock down the walls with heavy equipment or set the house on fire. The homeowner has the more difficult job.

FIGURE 1-7 Many-to-one threat vs. defense model

In fact, the defender has an impossible job if the goal is to protect against all attacks. That is why the primary goal of security is not to eliminate all threats. Every defender performs a risk assessment by choosing which threats to defend against and which to simply overlook or insure against. Mitigation is the process of defense, transference is the process of insurance, and acceptance is deciding that the risk does not require any action.

A security infrastructure will drive an attacker to the weakest link. If the front door lock is too difficult to pick, the attacker will try the window. If the window is unbreakable, they will try other entrances. If the doors, windows, roof, and basement are all impenetrable, a determined attacker may cut a hole in the wall with a chainsaw. Unless all defenses are equally secure, the successful attacker will pick the easiest method.

All security controls should complement each other. This principle is called equivalent or transitive security, demonstrated in Figure 1-8. Threats come from many sources and tend to focus on the weakest link, so protecting a particular asset (for example, a credit card number) requires securing the asset as well as securing other resources that have access to that asset. These resources may include information and non-information resources, and focusing on the data itself can overlook important threat vectors. Security for a credit card number should also include securing the system on which it resides, the network attached to that system, the other systems on the network, non-computer equipment (such as fax machines and phone switches) attached to that network, and the physical devices for each of these. It should also include securing the processes and procedures that affect that credit card number, such as system administration, backup tape rotation and handling, and background checks and hiring and termination procedures. Securing the data means discovering its path throughout the system, and protecting it at every point.

FIGURE 1-8 Transitive security controls

In a computer network, firewalls are often the strongest point of defense. They see their fair share of attacks, but most attackers know that firewalls are difficult to penetrate, so they will look for easier prey. This can often take the form of modems, Private Branch Exchange (PBX) phone switches, web servers, e-mail servers, and Domain Name Service (DNS) servers that are Internet-addressable and offer less resistance than firewalls. That’s why it’s important for the security of these objects to be equally as strong as the firewall. Figure 1-9 demonstrates this concept. For any device such as a computer system that is to be protected, more attacks will occur via less protected paths and those attacks will typically be more often successful. The attack vectors shown in the diagram may be Internet attacks, modem attacks, virus attacks, and the like. The most successful of those will be the ones that take advantage of the weakest security, denoted in the diagram by the protection level.

FIGURE 1-9 Attack vectors focus on the weakest link

One objective of an effective security strategy is to force the attacker to spend so much time trying to get past the defenses that they will simply give up and go elsewhere. Other strategies attempt to delay the intruder for a long enough time to take a reactive response, such as summoning authorities. Still others try to lure the attacker into spending too much time on a false lead.

In any case, weak points in the security infrastructure should be avoided whenever possible. In situations where weak points are necessary due to business requirements, detective and deterrent security controls should focus on the areas where defensive weak points exist. You can expect these weak points to attract attackers, and you should plan accordingly.

Since the e-commerce approach to security is relatively new, there are still differing philosophies and approaches. The security practitioner often encounters all-in-one products or techniques that are advertised as security-in-a-box, solving all a company’s security problems without additional investment of money, time, or resources. Unfortunately, these vendors often catch the ear of senior management with a compelling story of efficiency and savings. For example, a firewall product might be advertised as an intrusion-detection system, e-commerce enabler, and pancake griddle, all rolled into one. One of the problems with this picture is that all security products have weaknesses, bugs, and limitations that are often only exposed after they are installed.

Some security professionals exacerbate the problem. For example, some espouse the concept of encrypting everything and ignoring firewalls and other access controls. Digital Rights Management (DRM) is another silver bullet that has recently appeared. Unfortunately, most security implementations are flawed. Companies, driven by costs rather than quality, tend to employ internal resources toward developing their own security technologies and approaches instead of looking to outside specialists. People who specialize in fields other than encryption, and thus tend to be naive, typically develop most encryption implementations using obfuscation or using small symmetric-key algorithms, instead of using industry-respected encryption techniques like Blowfish, or the U.S. government’s Advanced Encryption Standard (AES). Consider, for example, the case of Content Scrambling System (CSS) encryption employed on digital video disc (DVD) movie discs. The DVD consortium developed a proprietary encryption standard for copy protection, which was easily broken in a very short amount of time.

The best way to approach any security implementation is to assume that no technology will be 100 percent effective, and plan accordingly. Multiple layers of security can be used to overcome weaknesses in any one layer.

In accordance with the “silver bullet” fallacy, many companies choose to place technical controls on their network without accompanying business processes. In these situations, the company has not recognized that computers are tools for accomplishing some kind of objective, and that tools should be considered within a business process in order to be effective. For example, purchasing a database does not solve the problem of how to manage customer data. Customer data management is a business process that is handled differently by each company, and a database is a tool that can be used to facilitate that business process.

CAUTION There is a clear distinction between processes and tools. Often, the tools only support a limited set of processes, and in these situations, the processes may have to conform to the limitations of the tools. However, the tools only automate the processes, they do not define them.

In the context of network security, business processes determine the choice of tools, and the tools are used to facilitate the business processes. Figure 1-10 illustrates this principle. Any security implementation is a snapshot that includes the current threat model, the protection requirements, the environment being protected, and the state of the defensive technology at the time. As technology and the business environment evolve over time, the technical controls that are part of this snapshot will become less and less appropriate. The importance of considering business processes during the tool selection process is that it helps ensure that the security architecture does not spring leaks due to changing conditions. Proper consideration of how the security tools will be used to facilitate the business requirements improves the likelihood that the security tools will remain effective and adequate. Examples of security tools that should adhere to this principle include change management, security monitoring and management, and management of people and communication. More examples are shown in Figure 1-10.

FIGURE 1-10 Business processes drive tool selection

Before selecting security products, the business processes must be identified so that security products that fit appropriately into the business environment can be chosen. Consider a credit card transaction involving a customer, a supplier, and a bank. A business would be ill advised to go to the local computer store to find credit card–transaction software without first considering the transaction flow. Once the business objectives are clearly defined, the transaction flow can be identified. Because it is unlikely that any one product will be able to secure this transaction from end to end, a series of products will have to be employed to provide security at various points in the transaction cycle. These products are tools that can be used to accomplish specific goals at each point in the process.

We know that threats exist, but relatively few of us have personally experienced an attack. The percentage of successful attacks is quite small, which provides a false sense of security. A natural assumption is that if there has not yet been an attack, there will not be one—that past experience creates future expectation. But if we can’t be 100 percent secure, what’s the point of doing anything at all? In other words, if we can’t prevent a determined attack, why bother trying? The answer is that security is about managing risk, and about using the available tools to make our environment better. We can do much to improve security to the point where our risks are under our control.

Note that the following are the assumptions we should make when considering the topic of security:

1. You can never be 100 percent secure.

2. You can, however, manage the risk to your assets.

3. You have many tools to choose from to manage risk.

4. Used properly, these tools can help you achieve your risk management objectives.

From the perspective of the security practitioner, determining the business processes can present challenges. Often, the security practitioner is presented with a predefined problem and told, “Here, secure this.” In these situations, the security practitioner must attempt to understand the underlying business process and its data flow in order to do a good job. This requires extra time and effort, but it’s necessary for success. The sooner the security practitioner is included in the planning process, the more successful the security component will be.

The overall approach to security, as with any endeavor, is to begin with describing what security is needed and why, and to proceed to define how it will be implemented, when, and using which particular steps.

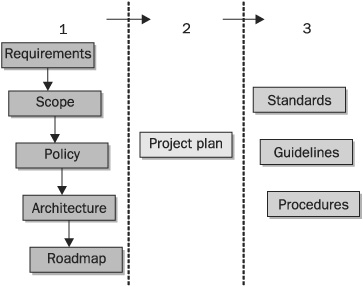

A complete security implementation should include many components. Ideally, these components will be produced by the five-step process described earlier in this chapter. Some essential components of any security implementation include: a requirements definition, a scope definition, a security policy, a security architecture specification, a roadmap, a project plan, and guidelines, standards and procedures.

CAUTION Many people faced with the responsibility of a new implementation wonder if all this planning and documentation is necessary, and they would prefer to get started by purchasing a product and turning it on for everyone. This is a dangerous practice. Planning and documentation are necessary not only for the protection of the person responsible for the implementation, but also for the success of the project and its effectiveness in meeting corporate objectives. Documentation is also important for legal liability reasons.

A requirements definition is the starting point of any successful security endeavor. In order to produce solutions that fit the business requirements, those requirements must first be clearly understood and communicated. They can be as simple as “protect the network from Internet attacks” or “ensure that private company data does not get disclosed to news agencies without prior authorization.” They can be complicated multipage documents. Regardless of the complexity, you should begin every project by documenting the project’s requirements.

A scope definition is necessary to specify the cost, size, and timing of a project. The scope of any new project often begins with a part of the whole, a small subset of the entire infrastructure so that difficulties can be addressed during the implementation. Many projects are broken into several phases in order to make the implementation more manageable. In any case, scope definition is important to avoid missed expectations and to clarify who will be affected by a project. With a clearly defined scope, the person responsible for the project can provide clear answers to the questions of when and where security components are to be installed.

The security policy, as previously discussed, provides a framework for the security effort. The policy describes the intent of executive management with respect to what must be done to comply with the business requirements. The policy drives all aspects of technical implementations, as well as policies and procedures. Ideally, a security policy should be documented and published before any implementations begin, but in practice, this rarely happens. However, a policy always exists, whether documented or unstated, because people have made business decisions (good or bad) about what to do based on certain assumptions. If the assumptions were not documented, they may have been unclear or they may conflict with other activities. Documenting these assumptions in a clear, easy-to-read security policy helps communicate expectations to everyone involved, even if it must happen after the fact.

The security architecture specification documents how security is implemented, at a relatively high level. It is driven by the security policy and identifies what goes where. It does not include product specifications or specific configuration details, but it identifies how everything fits together. A good tool for architecture documents is a block diagram—a diagram that shows the various components of a security architecture at a relatively high level so the reader can see how the components work together. A block diagram does not show individual network devices, machines, and peripherals, but it does show the primary building blocks of the architecture. Block diagrams describe how various components interact, but they don’t necessarily specify who made those components, where to buy them, what commands to type in, and so on.

A roadmap is a plan of action for how to implement the architecture. It describes when, where, and what is planned. The roadmap is useful for managers who need the information to plan their other activities, and to target specific implementation dates and the order of actions. It is also useful for the implementers, who will be responsible for putting everything together. The roadmap is a relatively high-level document that contains information about how the implementation will proceed, but without headcount and time estimates (which appear in the more detailed project plan).

Figure 1-11 shows all of these components of a security effort and how they relate to each other. Group 1 is the result of the initial planning effort, which produces a set of documents that describe how the implementation will proceed. Group 2 includes the project plan that will be used to control and track the implementation effort, during which the security infrastructure is built. Group 3 includes the practices used to maintain the ongoing effectiveness of the security architecture.

FIGURE 1-11 Security implementation process flow

The project plan details the activities of the individual contributors to the implementation. A good project plan opens with an analysis phase, which brings together all of the affected parties to discuss and review the requirements, scope, and policy. This is followed by a design phase, in which the architecture is developed in detail and the implementation is tested in a lab environment. After the design has been made robust, a controlled beta test with a clearly defined test plan is used to expose bugs and problems. The implementation phase is next, with the implementation broken into small collections of tasks whenever possible. Testing follows implementation, after which the design is revised to accommodate changes discovered during testing. Upon completion, the implementation team should meet to discuss the hits and misses of the overall project in order to prepare for the next phase.

NOTE Requirements, scope, policy, architecture, and roadmaps are strategic in nature. Project plans, guidelines, standards, and procedures are tactical.

Guidelines for the use of software, computer systems, and networks should be clearly documented for the sake of the people who use this technology. Guidelines are driven to some extent by the technology, with details of how to apply the tools. They are also driven by the policy, as they describe how to comply with the security policy.

Standards are the appropriate place for product-specific configurations to be detailed. Standards are documented to provide continuity and consistency in the implementation and management of network resources. Standards change with each version of software and hardware, as features are added and functionality changes, and they are different for each manufacturer. This is why this level of detail is not included in the architecture, so that the architecture can remain in place and survive changes in individual vendors. Standards do change, and they require frequent revision to reflect changes in the software and hardware to which they apply. Architecture, policy, scope, and requirements drive standards.

Procedures, like standards, apply to the specific tools with which they are associated. They describe how the tools should be managed and utilized, in order to provide consistency and clarify the intent of management. Procedures give the network users a clear expectation of how to comply with corporate policy. Policy, scope, and requirements drive procedures.

Security implementations that solve specific business problems and produce results that are consistent with clearly identified business requirements produce tangible business benefits by reducing costs and creating new revenue opportunities. Companies that provide access into their network under control allow employees and customers to work together more effectively, enabling the business. Security both prevents unwanted costs and allows greater business flexibility. Thus security creates revenue growth at the same time as controlling losses.

Security can be thought of in the context of the three Ds: Defense, Deterrence, and Detection—each equally important. Defense reduces misuse and accidents, deterrence discourages unwanted behavior, and detection provides visibility into good and bad activities. A security effort that employs all three Ds provides strong protection and therefore better business agility. The three Ds can be implemented in a five-step process leading from identification of assets, to risks analysis, to identification of protections, to tool selection, and finally to prioritization of efforts. Strategies are used to manage proactive security efforts, and tactics are used to manage reactive security efforts. A security strategy is a definition of all the architecture and policy components and tactics are processes and procedures. Together, well-designed security strategy and tactics result in effective, business-driven defense, deterrence, and detection.

Byrnes, Christian F. Securing Business Information: Strategies to Protect the Enterprise and Its Network. Massachusetts: Addison Wesley, 2002.

Fites, Philip E. and Kratz, Martin P.J. Information Systems Security: A Practitioner’s Reference. New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold, 1993.

Herrmann, Debra S. A Practical Guide to Security Engineering and Information Assurance. Florida: CRC Press, 2001.

Katsikas, Sokratis and Gritzalis, Dimitris, eds. Information Systems Security: Facing the Information Society of the 21st Century. Florida: Chapman & Hall, 1996.

Longley, Dennis and Shain, Michael. Data and Computer Security: Dictionary of Standards Concepts and Terms. Florida: CRC Press, 1989.

Schweitzer, James A. Computers, Business and Security: The New Role for Security. Missouri: Butterworth-Heinemann, 1987.

Sherwood, John. Security Architecture: How to Build and Run a Secure Enterprise Network. Massachusetts: Addison Wesley, 2003.

Tipton, Harold F. and Krause, Micki, eds. Information Security Management Handbook. Florida: Auerbach Publishing, 2001.

Tudor, Jan Killmeyer. Information Security Architecture: An Integrated Approach to Security in the Organization. Florida: CRC Press, 2000.

Van Solms, B. Information Security: The Next Decade. Florida: Chapman & Hall, 1995.

Wood, Charles Cresson. Best Practices In Internet Commerce Security. California: Baseline Software, 2001.