Every company should have a security organization. Individual companies will have differing needs; some require a larger organization with multiple levels of management, whereas others need only a small number of individual contributors reporting to a single manager.

Regardless of the size of the security organization, it should have executive-level representation in the company. Information security is ultimately the responsibility of senior management, and company executives are ultimately accountable for the state of their company’s security. The position of chief security officer (CSO) (sometimes referred to as the chief information security officer, or CISO) is a relatively new executive position that is becoming established in major corporations. The CSO position allows the other company officers to focus on different issues that are important to the business, while the CSO focuses on security.

Not all companies require a CSO, but all companies do require some form of clearly defined reporting structure related to security. Since the executives and the CEO are responsible for what goes on in their company, errors and shortfalls in the security infrastructure should be an important concern. Delegating the responsibilities related to security provides these executives with a means to address their security requirements.

Key decision makers for the security organization should not share responsibilities that produce conflicts of interest with other groups. When conflicts occur, different organizations should come together to identify appropriate resolutions, rather than having a single individual make a decision that may not be in the best interests of the company and its executives. Information security practices should be driven by the needs of the business, not by technology.

Smaller companies may employ a security organization that consists of a few individuals who may have other responsibilities (as long as those responsibilities don’t conflict with their security roles). Midsized companies need several security positions ranging from the technical security administrators who configure firewalls, routers, antivirus software, and the like to security engineer(s) who design security controls, and to a security director or vice president. Large companies need a complete security organization. All companies, large or small, need an executive decision maker who has been designated as responsible for security, and who receives reports from staff that work on security.

In addition, the distinctions between large and small companies and what security positions they require vary according to what the company does. Financial companies typically require a larger and more robust security organization due to the capital financial risk involved in a breach of their security. Technology companies may require a middle-sized or smaller security organization, depending on how much they have to lose from an attack and how much they stand to gain from strong security. Every company is different.

Commonly, the following roles are found in security organizations. These roles are described in more detail later in this section.

• Security officer Responsible for communication with executive team, overall management of the security organization, staffing decisions, conflict resolution, and budget.

• Chief security officer Same as a security officer, but a recognized member of the executive team.

• Security manager Responsible for coordinating the efforts of the technical staff and making sure that the security efforts conform to the business requirements, along with making decisions during an attack or security failure.

• Security architect Responsible for defining and planning the security infrastructure, including technical security architecture, security policy, standards, guidelines, and procedure.

• Facility security officer Responsible for what goes on at their particular site. This person keeps an eye on operations, makes sure that policies and procedures are adhered to, and is the first line of response in the event of a security incident.

• Security administrator Manages and monitors devices and systems related to security, such as firewalls, router ACLs, antivirus systems, and spam screening servers.

Other roles exist outside the formal security organization, because everyone in the company has some level of responsibility for security. For example, general employees carry responsibility for protecting their passwords, login sessions, and confidential information they handle. General managers keep an eye on company operations and ensure that violations are reported, and may carry out enforcement policies.

The mission statement for the security organization should be clearly published and supported by senior management. This helps the rest of the company understand what the priorities and goals are of the security organization, and it helps the security organization stay on track with its intentions.

This person has ultimate responsibility for all security efforts for the company. The CSO is a champion and defender of security initiatives for the company, bearing overall responsibility for product security, corporate infrastructure security, and security policies, as well as for security evaluations, assessments, and incident handling. The CSO represents security issues, concerns, initiatives, and successes to the Board of Directors.

The CSO works with the executive team to accomplish business goals. The CSO position requires expert communication, negotiation, and leadership skills, as well as some technical knowledge of information technology and security hardware. The CSO oversees and coordinates security efforts across the company, including information technology, human resources, communications, legal, facilities management and other groups, to identify security initiatives and standards.

The CSO, among other responsibilities:

• Oversees security directors and vendors who safeguard the company’s assets, intellectual property, and computer systems, as well as the physical safety of employees and visitors

• Identifies protection goals and objectives consistent with corporate strategic plans

• Manages the development and implementation of global security policy, standards, guidelines, and procedures to ensure ongoing maintenance of security

• Maintains relationships with local, state, and federal law enforcement and other related government agencies

• Oversees the investigation of security breaches and assists with disciplinary and legal matters associated with such breaches as necessary

• Works with outside consultants as appropriate for independent security audits

The security manager has responsibility for all security-related activities and incidents. External interactions, especially interactions with law enforcement, will not be delegated. This individual will be an employee and will set policy. All other operational security positions report to this position. This person is responsible for maintaining and distributing the security policy, policy adherence and coordination, and security incident coordination.

The security manager also assigns and/or determines ownership of data and information systems. In addition, this person also ensures that audits take place to determine compliance with policy. The security manager also makes sure that all levels of management and administrative and technical staff participate during planning, development, and implementation of policies and procedures.

Many of the security manager’s functions are often delegated, depending on the staffing requirements and individual skill sets of the security organization. However, the security manager bears responsibility for ensuring that these functions take place effectively.

In addition to other roles, the security manager:

• Develops and maintains a comprehensive security program

• Develops and maintains a business resumption plan for information resources

• Approves access and formally assigns custody of the information resources

• Ensures compliance with security controls

• Plans for contingencies and disaster recovery

• Ensures that adequate technical support is provided to define and select cost-effective security controls

This person has ultimate responsibility for the security architecture, including conducting product testing; keeping track of new bugs and security vulnerabilities as they arise; and providing patches for the operating system, databases, and applications. The security architect produces a detailed security architecture for the network based on identified requirements and uses this architecture specification to drive efforts toward implementation.

In addition to other roles, the security architect:

• Identifies threats and vulnerabilities

• Identifies risks to information resources through risk analysis

• Identifies critical and sensitive information resources

• Assesses and classifies information

• Works with technical management to specify cost-effective security controls and convey security control requirements to users and custodians

• Assists the security manager in evaluating the cost-effectiveness of controls

The primary role of this position is to enforce the company’s security policy. Each major company facility location has a security officer responsible for coordinating all security-related activities and incidents at the facility. The person in this role is not the same person who is operationally responsible for the computer equipment at the facility. This person has the authority to take action without the approval of the management at the facility when required to ensure security.

All log files or their summaries as prepared by the security administrator are reviewed by this person. The facility security officer is responsible for coordinating all activities related to a security incident at the facility and has the authority to decide what actions are to be taken as directed by the Incident Response procedures. The facility security officer coordinates all activities with the corporate security officer.

Every company has security administrators, as many as needed to implement security on a day-to-day basis at the facility, who are responsible for evaluating all potential and known security incidents and advising the facility security officer as to the best technical course of action. The security administrator executes all actions directed by the facility security officer or the Incident Response procedures. This person is responsible for ensuring all appropriate security requirements are met and maintained by all computers, networks, and network technologies. Security logs are reviewed by this person and summarized for the facility security officer.

The security administrator is the first person contacted whenever there is a suspected or known security problem. This person has the responsibility for ensuring that the company, its reputation, and its assets are protected and will have the authority to take any and all action necessary to accomplish this goal.

Among other duties, the security administrator:

• Implements the security controls specified by the security architect

• Implements physical and procedural safeguards for information resources within the facility

• Administers access to the information resources and makes provisions for timely detection, reporting, and analysis of actual and attempted unauthorized access to information resources

• Provides assistance to the individuals responsible for information security

• Assists with acquisition of security hardware/software

• Assists with identification of vulnerabilities

• Develops and maintains access control rules

• Maintains user lists, passwords, encryption keys, and other authentication and security-related information and databases

• Develops and follows procedures for reporting on monitored controls

Several individuals in a company have important responsibilities in the maintenance of security. These individuals may or may not focus exclusively on security in their jobs. Some of these positions are security positions; others are held by people who are responsible for keeping the company secure even if their primary job is something else. Some of these positions include:

• HR positions:

• Security awareness trainer

• IT employees:

• System administrator

• Network administrator

• General employees:

• Data owner

• Data custodian

• Security positions:

• Security administrator

• Security auditor

The security awareness trainer implements the security awareness and training programs outlined in this chapter. This is a people-oriented, training position that typically reports to the Human Resources department because of its focus on employee growth and education.

Every IT department has system and network administrators. Sometimes these are the same person; sometimes the duties are divided among different individuals or departments. Regardless of the reporting structure, the system and network administrators bear important security responsibilities. System administrators build new computer systems; install operating systems; install and configure software; and perform troubleshooting, maintenance, and repairs. In the course of all of these functions, security standards and policies apply. Operating systems must be installed in compliance with the security standards for their particular application. This usually includes turning off unneeded services, applying the latest security updates and patches, and applying templates and secure configurations to software applications. Any oversight or failure to consider the security of the system can compromise the entire company, so the system administrator position is crucial to the success of the security program.

Network administrators have responsibilities and levels of access that require them to conform to security standards and policies as well. Often, the network administrator is responsible for firewall and router configurations that apply the company’s security policy in specific situations. Incorrect or inappropriate configuration choices can open up security holes that put the entire company at risk.

Data that is resident on computer systems, shared storage devices, databases, and applications must be handled securely. This means encrypting the data in storage and in transit, performing change control, and implementing access controls and authorization levels to ensure that only the right people can get to the information. The operational responsibility for this data security management falls into the domains of the data owners and the data custodians. Data owners make the decisions that determine who should modify, view, change, and create information files. The owner of each piece of data should identify who is the intended audience, who can make changes, and who can erase the data.

The data custodian implements the decisions of the data owner by making approved changes, presenting the data to the appropriate audience, and properly destroying the data when it is deleted. When sensitive data is strongly overwritten, the data custodian ensures that the data is properly destroyed.

Security response teams are known by several names. Some are called SRT for security response team, some are called CIRT for computer incident response team, and some are called IRT for incident response team. Regardless of the specific terminology, these teams are collections of individuals from various parts of the company that are brought together to handle emergencies. They join the team apart from their daily responsibilities to prepare, practice, drill, and in the event of an emergency, handle the situation.

Examples of the types of incidents a response team might handle include:

• Hostile intrusions into the network by unauthorized people

• Damaging or hostile software loose on a system or on the network

• Personnel investigations for unauthorized access or acceptable use violations

• Virus activity

• Software failures, system crashes, and network outages

• Cooperation with international investigations

• Court-ordered discovery, evidentiary, or investigative legal action

• Illegal activities such as software piracy

Every company performs incident response, whether or not they have an official IRT established. In many organizations where there is no incident response team, individual employees perform incident response by dealing with incidents in their own way. A software virus outbreak is one example. In organizations without an IRT, employees may choose to install antivirus software, run specialized virus cleaning software, or just live with a virus infestation. In these situations, no coordination happens and virus response varies with each individual, usually without enterprise-wide success. One advantage of an organized IRT is that it can deal with incidents like this on a higher level, with more comprehensive success.

Members of an IRT should include technical experts who can evaluate incidents like network intrusions, software failures, and virus outbreaks on a technical level; administrators who can keep logs and maintain the paperwork and electronic information associated with an incident investigation; managers who coordinate the work of the incident response team members; and if available, IRT specialists who have served on prior IRTs. None of these individuals necessarily needs to be assigned to the IRT as a full-time position. Typically, companies that establish IRTs leverage employees from many other parts of the organization and ask them to share their responsibilities between their regular job and the IRT.

An IRT can be assigned individuals with specific technical expertise in a variety of areas. Depending on the company and the types of technologies used in the infrastructure, this expertise may include:

• Virus management

• Hostile software detection and management

• Vulnerability analysis

• Specific hardware platforms

• Specific operating systems

• Commercial off-the-shelf, shareware, or freeware software

• Custom-developed or in-house-developed software

The incident response team should have a clearly defined depth of standard investigations, because investigations become more expensive and time-consuming as they go deeper. The IRT may also need to prioritize its activities, especially in cases where several incidents happen at once, and this prioritization should be directed by management rather than the individual team members, to keep the team aligned with the corporate goals.

Daily IRT operations can include interpretation of reported incidents; prioritization and correlation with existing efforts; evaluation of current trends and industry experiences; verification that incidents are real; categorization of incidents; and summarization and reporting to management, end users, and outside agencies. Once incidents are identified and evaluated, removal of the cause by blocking or fixing the exploited vulnerability and restoration of the original state of the impacted system or network can be performed. During the entire process, a careful log and audit trail should be preserved, and information gathered should be evaluated to determine how to improve IRT operations in the future (and this information may be required for legal purposes if prosecution is pursued).

Many aspects of an IRT’s actions can be identified, categorized, and codified. These actions should be documented as part of an operational procedure manual. This allows individual team contributors to make informed and appropriate decisions during the heat of an incident. Operational procedures can include standard incident response process, vulnerability analysis and remediation, communication with other groups and with the general company, coordination with law enforcement and the court system, and evidence handling and audit trail maintenance.

Many companies want to have their own in-house IRT, so the team can integrate into the corporate culture and become more informed and effective. Others prefer to outsource this function to avoid having to hire incident response specialists. Outsourcing carries the additional advantage of pay-as-you-go, where costs associated with incident response occur only when the IRT is activated during an incident. Incident handling should be done according to a consistent set of well-documented procedures, in case a court proceeding is required. Investigation manuals are available from a variety of sources that can be used to guide the investigator.

One of the basic security principles is separation of powers: One group of people or managers should not be allowed both to set the rules and to manage compliance to the rules. If all of the functions listed in the preceding section were placed with a single person or organization, there would be no separation. Even placing them all within the IT division would be much too close. A few of the roles can easily be seen as fully separated from IT. The internal auditor and the resource owner are the first two to be handed to other managers.

Separation of duties refers to dividing roles and responsibilities so that a single individual cannot weaken a critical process. For example, the person who enters payee information into a system should not be the same person who authorizes payments to be made or has the ability to delete a payee from a system. This separation of entry, approval, and deletion duties helps ensure that a financial system is not used to make improper payments and then cover up the fact that the payments were ever made. This separation should apply to approving, implementing, and auditing computer accounts as well. The same principle that applies to finance applies to information technology, for the same reason—so that one person cannot compromise the system.

If two elements of a transaction are processed by different individuals, each person provides a check over the other and can provide accountability for the other. Separation of duties also acts as a deterrent to fraud or concealment because neither individual can defeat the system without help from the other one and collusion with the other individual is required to complete the fraudulent act.

As an example, separating responsibility for physical security of assets from related record keeping is a critical control. This helps to reduce loss or theft of physical assets because the records are more likely to accurately reflect the actual inventory when the record keeper has no connection with the asset handler.

Another IT example is data entry. When data entry is separated from data validation and verification, a data-entry supervisor can check on the accuracy of data entry but cannot enter a new transaction without having a direct supervisor check the work. If the supervisor were to enter a transaction and then personally authorize it, there would be no control to prevent error or fraud.

As an example of separation of duties applied in the IT environment, the person who designs or codes a program is not the one who tests the design or the code. Test systems are separate from production systems so that test data does not become intermixed with production data and private production data cannot be viewed by programmers. Programmers and other staff who do not have direct responsibility for physical systems do not enter the computer room.

The roles and responsibilities of personnel, including computer support personnel, should be assigned in such a way as to avoid conflicts of interest. Security controls should never be placed completely in the hands of a single individual; instead, security teams and the “buddy system” are used.

An adjunct concept to separation of duties is the principle of least privilege. This means that each person has only the access required to perform their job function, not more (or less).

Applying the principle of separation of duties can present a challenge in modern computing environments. Most commonly used computer systems have a “superuser” or “administrator” account that provides full, unrestricted access to all parts of the operating system and all data on the system. In addition, some networks have a “domain administrator” account that has administrative privileges on all systems on the network. This means that anybody with the password to these accounts has unrestricted access. When access is unrestricted, the principle of least privilege is also violated.

One of the biggest problems with default administrative user accounts is that they are shared (generic) accounts, without uniqueness. That means that anyone with the password can do anything on the system without being uniquely identified. Later, when something has changed on the system, there is no audit trail that points back to a specific individual. When changes become untraceable, computing environments become chaotic. Thus, each administrative account should be unique, and closely tied with a single individual.

With the removal of generic administrative accounts, individually assigned unique accounts can be granted levels of privilege appropriate to each person’s job function. Backup operators can be put into groups that allow access to backup functions but not account creation, help desk personnel can be put into groups that allow password resets or account creation, but not e-mail administration, etc. In order to assign these functions, the IT organization must plan for the roles of the individual contributors beforehand.

Security operations vary from company to company and environment to environment. Commonly, the management of individual components of the security architecture includes devices such as firewalls, network access control devices such as routers, VLAN segmentation, VPNs, antivirus devices, and desktop firewall software. Management of these components can be assigned to the company security organization as opposed to the network or server operations teams. This provides separation of duties between the daily operations and the security management.

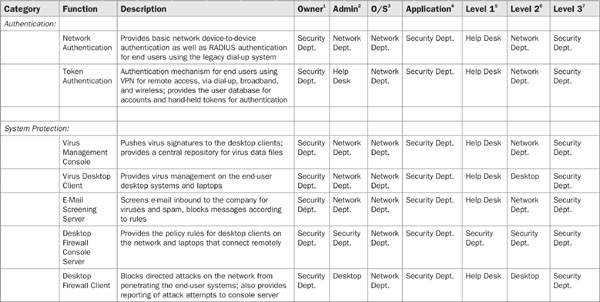

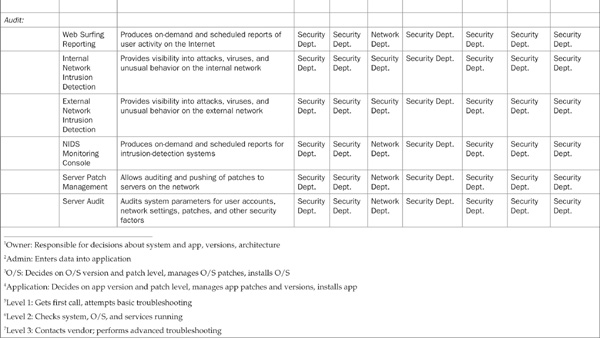

Regardless of the specific duties assigned to security operations personnel, the definition of who does what should be clarified. One way to do this is with a matrix (or spreadsheet). On one axis, specific duties can be listed, and on the other axis, systems or software components can be specified. In each cell, the owner is identified. The owner is the primary point of contact for each task. Table 4-1 shows an example of one such responsibility matrix.

TABLE 4-1 An example of a responsibility matrix

All network architecture changes, additions, enhancements, and deletions should first be approved by the security architecture management, because they may influence security on the network. This is true for system changes as well. In cases where new software is being added to systems, or software versions are changed, security management should first be consulted to determine whether any new vulnerabilities or risks will be introduced by the use of new software, different functionality, or bugs in various versions of software.

When security management is consulted for network or system changes, the consultation should happen when the concept is first discussed. The sooner the security organization is included, the more time they will have for research and consultation, and the more time the network or system administrators will have to take into account any changes that must be made. Bringing in security management just before or during implementation only hurts both organizations and the best interests of the business, because any required modifications then become rushed and timeline requirements may not permit implementation of all necessary requirements.

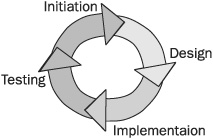

For the same reasons security operations management should be included in the concept stage of any network or system infrastructure modifications, they should also be included in the initiation phase of any project. A standard project methodology includes the following phases:

• Initiation

• Design

• Implementation

• Testing

Figure 4-1 shows the four primary phases of a standard project lifecycle. During this lifecycle, security requirements should be considered at each phase. Initiation, the first and most important phase, defines initial business requirements that include security requirements. In the design phase, security controls are identified and designed into the architecture. During implementation, security devices and technologies are deployed. In the testing phase, security functions are tested to ensure that they adequately protect the business and don’t interfere with intended operations.

FIGURE 4-1 Project management cycle

Security requirements are always addressed in the first (initiation) phase of any implementation project, to ensure that they are not overlooked. Security controls are included in the design process, and they are implemented during the implementation phase and tested during the testing phase as part of every rollout.

In a good project plan, the testing phase will lead back to a second initiation phase during which improvements and refinements in the project can be made. This represents a new cycle for the project, beginning once again with an initiation phase, and a project may have many such cycles. Typically, one phase is not enough to accommodate changes and user feedback.

After testing has been completed, areas that did not meet expectations or have opportunities for refinement and optimization are addressed as a second-phase project, which begins with initiation and continues throughout another lifecycle. This process is repeated as business requirements, the environment, and technologies change and evolve and as new standards arise.

The security organization should be included in all efforts that involve corporate data and resources. Many different departments handle data, not just information technology. For example, the Human Resources department handles confidential employee information. The legal department handles confidential company and customer information. The facilities department handles badging and physical access. Generally speaking, every major organization in the company has some level of interaction with company resources and data. All of these organizations should coordinate with the security organization. In most companies, the security team meets almost every manager of the company, and sometimes with most of the employees.

A corporate security council, whose members include representatives from each major company department, provides a forum for information exchange that facilitates the job of the security practitioner and identifies business requirements to which the security organization should be privy. Each security council representative provides status updates of initiatives within that representative’s organization, and each receives information from the security organization about initiatives and practices that impact each of them.

The security council can be used in a variety of ways. Information gathering is one opportunity that should not be overlooked. Members of the security council have unique visibility into the operation of their part of the business. This visibility is important to the comprehensiveness of the security practitioner’s focus. For example, a department that is considering a new technology initiative may not have considered the security impact on the rest of the network, but the security practitioner, upon hearing about the initiative, may make conceptual connections overlooked by the individual department.

A security council can also be an effective risk management tool. The purpose of a risk analysis is to identify as many business risks as possible, and then either accept, mitigate, or transfer those risks. Any risks that are overlooked by a risk analysis put the company in jeopardy if any of those risks become realized. Members of the security council can be polled to identify specific business risks in each of their specialties, and this provides a risk analysis with a greater scope and better coverage.

Another advantage of a security council is that it gives a sense of participation and teamwork to organizational departments that may otherwise act independently without consulting each other, or even compete for resources or produce conflicting infrastructures.

Some of the efforts of the security organization are meant to be visible to the rest of the company. The security council presents an excellent forum for distributing this information. However, some security information is meant to remain confidential. One example is the result of a risk assessment. The input to a risk assessment originates from many sources, often taking the form of a brainstorming session. The output of a risk assessment, with its details on ways in which the company can be compromised, is highly confidential and not meant to be shared with others. In this case, the security council is a source of information but not a recipient of the analysis of that information.

Human Resources reports required information about new hires to security administrators before the employee’s start date. This is an important interaction between HR and IT, even if the security organization is not part of the hiring procedure. Security administrators need to know at any point in time whose employment with the company is valid, so they can properly maintain and monitor accounts on systems and on the network. Perhaps even more important, HR also reports required information about terminations to system administrators before the final termination occurs. The security organization is always involved in terminations to some extent, because employee terminations result in the revocation of trust. When trust is revoked, assurance must be provided that all access has been revoked, and activity must be monitored to ensure the maintenance of that revocation.

HR manages contractor information and provides this information to security administrators. Contractors, as temporary employees, present special problems to security administrators. They often work for only a short time and sometimes come and go, resulting in a constant process of granting and revoking physical access and system and network accounts. It’s hard to tell when seeing a contractor in the hallways whether they should be there or not. The security of the network relies heavily on the timely transfer of information from HR to the security organization. HR, in turn, requires timely information from individual managers regarding the status of their contractors hired directly and managed individually.

HR performs background checks, credit checks, and reference checks on new employee applicants. Exit interviews are conducted with terminating employees to recover portable computers, telephones, smart cards, company equipment, keys, and identification badges and to identify morale problems if they exist. Employees discharged for cause must be escorted from the premises immediately and prohibited from returning in order to reduce the threat of retaliation, and also to forestall any questions if unexpected activity occurs on the network or on the premises.

Monitoring the activities of employees is a matter of corporate culture—those companies that want to do it differ in the extent and type of response they choose. Likewise, the treatment of confidential and private information differs from company to company, but these are issues that should be dealt with by every organization. If a company hasn’t gotten around to a formal policy on these issues, the best time to start is now, before a policy violation occurs when there is no clear, documented policy that has been communicated to all employees. Communication is truly the key to successful security management. Physical security should not be overlooked, and periodic fire drills can be used to test security measures, help close any gaps, and avoid the danger of having a false sense of security.

Security is a lifecycle. That means as the environment changes the security practices changes with it. Security must be an ongoing effort, because once the network is “locked down” on any given day, it will be vulnerable the next day as new software is added, new vulnerabilities are discovered, configurations change, and business requirements evolve.

The security lifecycle is governed by a process. This process starts with the first initiation of security policy and efforts in the company, continues through design and final implementation, and starts over again at the end. The four primary phases of the security lifecycle are:

• Assessment

• Policies

• Hardening

• Audit

Figure 4-2 shows these phases in relation to a complete cycle. Beginning with assessment, the security practitioner performs an evaluation of the current environment and what is needed to conform to changing business requirements. Definition of policy is next, to produce a clear statement of intent as to what the security controls should accomplish. Hardening is the process of implementing security controls on the network. After the network is hardened, an audit is performed to compare the actual implementation against the intentions provided by the policy.

After the audit, the process starts over with a new assessment as the environment changes, feedback is received and incorporated, and new products and technologies become available.

Security is most effective when it is implemented as a process rather than a set of technologies or product features. When thinking about security software, the security practitioner should really be thinking about software that supports security processes. In addition, it’s important to keep in mind that security processes exist to enable business processes.

Security processes differ from organization to organization. Thus, security technology that facilitates security processes often contains features sets that are appropriate to many different environments, some of which are conflicting. The security processes that are relevant in one particular company should be mated with the security features of technological products, rather than relying on the product features to provide security. Incorrect or incomplete implementations of other types of technology can result in reduced productivity or effectiveness, but faulty or inappropriate implementations of security technology can have disastrous results.

All security efforts should begin with an initial assessment that includes current security posture, identification of objectives, review of the business requirements, and a determination of current vulnerabilities, to be used as a baseline for testing after the project implementation. If the organization has a security policy in place, and the existing infrastructure is to be compared against that policy, then this step is referred to as an audit. If there is no security policy, and the infrastructure is to be evaluated for the purpose of determining business requirements to be used in developing a written policy, then this step is called an assessment. Typically, an assessment is performed the first time through a security effort in environments that have not had prior, clearly defined security processes in place. An audit is performed as part of a refinement of a pre-established set of processes.

The assessment (or audit) is followed by the development of appropriate policies to drive the design and operations of the architecture. The security policies that result from this step are critical to the success of the security program. The policies determine the success criteria and the business requirements that are addressed by the security design. Security policy is necessary to clearly document the objectives of senior management with respect to the security environment, and to produce a set of business requirements to which the security infrastructure will conform. Without this step, a security infrastructure may overlook important threat vectors, and technologies and practices may be implemented that don’t adequately protect the company. The security policy produced by this effort should be signed off by a senior corporate executive who will be accountable for the results of the security program.

During the hardening phase, the security implementation takes place and the security controls are “hardened” to properly carry out the intent of the security policy. This is the implementation phase. During this phase of the security lifecycle, the security controls that were created to satisfy the business requirements identified by the security policy are put in place and tested. This phase is normally driven by a complete project plan. Project plan methodologies vary from company to company, but a typical hardening effort may consist of the following steps:

• Analysis Determination of what technologies are available to implement the security policy

• Design Architecture and documentation of how the selected technologies will be implemented in the current environment

• Test Verification that the design works; this step usually breaks out into lab testing, beta testing, and pilot testing

• Optimize Refinement of the design to incorporate observations made during testing

• Implementation Roll-out (often phased) of the security design. In larger environments, implementation may be broken into groups to make the deployment more manageable

• Review Gathering of the project team to identify successful factors, and further steps for correcting shortfalls that may be addressed in the next phase of the hardening

The final step is the completion of an audit, which compares the operation of the security implementation against the expected outcome and the results of the initial assessment. This audit leads to an evaluation of the success of the project goals and is used as input to refining and optimizing the infrastructure. Opportunities for improvement that are discovered become part of the next iteration of the lifecycle, which begins with an initial audit and continues throughout the lifecycle again.

Input into the assessment process can be obtained from a variety of sources, including engineering, operations, and the incident response team. When the IRT analyzes security incidents, they are often analyzing failures of the defensive system that allowed an intruder or unauthorized software program to get past the hardening. When this happens, the infrastructure should be reviewed in light of that defensive failure in order to perform a more specialized and effective hardening the next time around.

The security lifecycle process is repeated constantly throughout the life of the company, as business requirements, the environment, and technologies change and evolve and as new standards arise.

Input into the security lifecycle comes from a variety of sources. Daily security audits and operational security activities yield information that is useful in adjusting the security infrastructure to be more effective. Intrusion-detection reports and response provide insight into some of the threats against the infrastructure that are realized or attempted. The types of machines attacked and the functions they perform may lead to different ideas about how to segment the network and isolate these components. Vulnerability analysis and patching procedures may also lead to architectural changes, especially when systems are grouped together in ways that can be used to prioritize these activities. Daily security operations can lend valuable insight into strategic, architectural decisions.

The first line of attack against any company’s assets is often the trusted internal personnel, the employees that have been granted access to the internal resources. As with most things, the human element is the least predictable and easiest to exploit. Trusted employees are either corrupted or tricked into unintentionally providing valuable information that aids intruders. Because of the high level of trust placed in employees, they are the weakest link in any security chain. Attackers will often “mine” information from employees either by phone, computer, or in person by gaining information that seems innocuous by itself but provides a more complete picture when pieced together with other fragments of information. Companies that have a strong network security infrastructure may find their security weakened if the employees are convinced to reduce security levels or reveal sensitive information.

One of the most effective strategies to combat this exposure of information by employees is education. When employees understand that they shouldn’t give out private information, and know the reasons why, they are less likely to inadvertently aid an attacker in harvesting information. A good security awareness program should include communications and periodic reminders to employees about what they should and should not divulge to outside parties. Training and education help mitigate the threats of social engineering and information leakage.

An ongoing security awareness program should be implemented for all employees. Security awareness programs vary in scope and content. See the reference section of this chapter for pointers to good resources for starting and maintaining a security awareness program. In this section, we will explore some of the basics of how to raise security awareness among employees in organizations.

Employees often intentionally or accidentally undermine even the most carefully engineered security infrastructure. That is because they are allowed trusted access to information resources through firewalls, access control devices, buildings, phone systems, and other private resources in order to do their jobs. End users have the system accounts and passwords needed to copy, alter, delete, and print confidential information. Propping doors open, giving out their account and password information, and throwing away sensitive papers are common practices in most companies, and it’s these practices that put the information security program at risk. It’s also these practices that a security awareness program seeks to modify and prevent.

In addition to practicing habits that weaken security, employees are also usually the first to notice security incidents. Employees that are well educated in security principles and procedures can quickly control the damage caused by a security breach. A staff that is aware of security concerns can prevent incidents and mitigate damage when incidents do occur. Employees are a useful component of a comprehensive security strategy.

The practice of raising the awareness of each individual in the company is similar to commercial advertising of products. The message must be understood and accepted by each and every person, because every employee is crucial to the success of the security program. One weak link can bring down the entire system. In a security awareness campaign, the security message is a sales pitch, the product to be sold is the idea of security, and the market is every employee in the company. Communicating the message is the primary goal, and the information absorbed by the employees is the catalyst for behavioral change. Employees usually know much of what an awareness program conveys. The awareness program reminds them so that secure behaviors are automatic.

A plan for an effective security awareness program should include:

• A statement of measurable goals for the awareness program

• Identification and categorization of the audience

• Specification of the information to be included in the program

• Description of how the employees will benefit from the program

Some of this information can be provided by security management (e.g., goals, types of information) and some can be provided by the audience themselves (e.g., demographics, benefits). Surveys and in-person interviews can be utilized to collect some of this information. Identification of specific problems in the company can provide additional insight. This information is needed to determine how the awareness program will be developed and what form its communication may take.

The objectives of a security awareness program really need to be clarified in advance, because presentation is the key to success. A well-organized, clearly defined presentation to the employees will generate more support and less resistance than a poorly developed, random, ineffective attempt at communication. Of paramount importance is the need to avoid losing the audience’s interest or attention or alienating the audience by making them feel like culprits or otherwise inadequate to the task of protecting security. The awareness program should be positive, reassuring, and interesting.

Just as with any educational program, if the audience is given too much information to absorb all at once, they may become overwhelmed and may lose interest in the awareness program. This would result in a failure of the awareness program, since its goal is to motivate all employees to participate. An awareness program should be a long-term, gradual process. An effective awareness program reinforces desired behaviors and gradually changes undesired behaviors.

The objectives that the awareness program manager should attempt to fulfill include:

• Participation should be consistent and comprehensive, attended and applied by all employees, including contractors and business partners who have access to information systems. New employees should also be folded into the current program. Refresher courses should be given periodically throughout the business year, so attention to the program does not wander, the information stays fresh in the employees’ memories, and changes can be communicated.

• Management should allow sufficient time for employees to arrange their work schedules so that they can participate in awareness activities. Typically, the security policy requires that employees sign a document stating that they understand the material presented and will comply with security policies.

• Responsibility for conducting awareness program activities is clearly defined, and those responsible perform to expectations. The company’s training department and security staff may collaborate on the program, or an outside organization or consultant may be hired to perform program activities.

Security awareness programs are meant to change behaviors, habits, and attitudes. To be successful in this, an awareness program must appeal to positive preferences. For example, a person who believes that it is acceptable to share confidential information with a colleague or give their password out to a new employee must be shown that people are respected and recognized in the organization for protecting confidential data rather than for sharing it.

The overall message of the program should emphasize factors that appeal to the audience. For example, the damage to a person done when their identity or personal information is stolen may result in a lowering of their credit score or increase in their insurance rates. An awareness program can focus on the victims and the harmful results of incautious activities. People need to be made aware that bad security practices hurt people, whether they intend to or not. The negative effects can be spotlighted to provide motivation, but the primary value of scare tactics is to get the user community to start thinking about security (and their decisions and behaviors) in a way that helps them see how they can protect themselves from danger.

Actions that cause inconvenience or require a sacrifice from the audience may not be adopted if the focus is on the difficulty of the actions themselves, rather than the positive effects of the actions. The right message will have a positive spin, encouraging the employees to perform actions that make them heroes, such as the courage and independence it takes to resist appeals from friends and coworkers to share copyrighted software. Withstanding peer pressure to make unethical or risky choices can be shown in a positive light.

Specific topics that are contained in most awareness programs include:

• Privacy of personal, customer, and company information (including payroll, medical, and personnel records)

• The scope of inherent software and hardware vulnerabilities and how the organization manages this risk

• Hostile software (for example, viruses, worms, Trojans, back doors, and spyware) and how it can damage the network and compromise the privacy of individuals, customers, and the company

• The impact of distributed attacks and distributed denial of service attacks

• The principle of shared risk in networked systems (the risk assumed by one employee is imposed on the entire network)

Once employees understand how to recognize a security problem, they can begin thinking about how they can perform their job functions in compliance with the security policy, and how they should react to security incidents. Typical topics for complying with security policy and incident response include:

• How to report potential security events, including who should be notified and what to do during and after an incident, and what to do about unauthorized or suspicious activity. Some situations may require use of verbal communication instead of e-mail, such as when another employee (especially a system administrator) is acting suspicious or when a computer system is under attack, and when e-mail may be intercepted by the intruder.

• How to use information technology systems in a secure manner

• Personal practices such as password creation and management, file transfers and downloads, and how to handle e-mail attachments

The awareness program should emphasize that security is a top priority of management. Security practices should be shown to be the responsibility of everyone in the company, from executive management down to each employee. Employees will take security practices more seriously when they see that it is important to the company rather than just another initiative like any other, and when executives lead by example. Codes of ethics or behavior principles can be used to let all employees know exactly what to do and what is expected of them.

Employees should also be clear about who to contact and what to report regarding security incidents. Information should be provided to the employees so that they know whom to contact during an incident. Contact information, such as telephone and pager numbers, e-mail addresses, and web addresses for security staff, the incident response team, and the help desk should be included.

Information requested from end users in a security report may include many different topics, such as:

• Date and time of the security incident

• Affected systems or functions, such as e-mail or web sites

• Symptoms

• Concurrent connections with other systems

• Actions taken

• Assistance requested

Employees should be made aware that time is critical in security compromise situations. They should be informed that immediate reporting of incidents could contain damage, control the extent of the problem, and prevent further damage.

Enforcement is arguably the most important component of network security. Policies, procedures, and security technologies don’t work if they are ignored or misused. Enforcing the security policy ensures compliance with the principles and practices intended by the architects of the security infrastructure.

Enforcement takes many forms. For general employees, enforcement provides the assurance that daily work activities comply with the security policy. For system administrators and other privileged staff, enforcement guarantees proper maintenance actions and prevents abuse of the higher level of trust given to this category of personnel. For managers, enforcement prevents overriding of the security practices intended by the framers of the security policy, and it reduces the incidence of conflicts of interest produced when managers give their employees orders that violate policy. For everyone, enforcement dissuades people from casually, intentionally, or accidentally breaking the rules.

Negative enforcement usually takes the form of threats to the employee—threats of negative comments on an employee’s review, of a manager’s displeasure, or of termination, for example. For some violations, a progression of corrective actions may be required, eventually culmination in loss of the employee’s job after many repeated violations. For other, more serious breaches of trust, termination may be the first step. Regardless of the severity of the correction, employees should clearly understand what is required of them, and what the process is for punishment when they don’t comply with the rules. In all cases, employees should sign a document indicating their understanding of this process.

Positive enforcement is just as important as negative enforcement, if not more so. This may take the form of rewards to employees that follow the rules. These employees are important—they are the ones who keep the business running smoothly within the parameters of the corporate policy. They should be retained and kept motivated to do the right thing. Rewards can range from verbal congratulations to financial incentives.

Security enforcement for business partners and other non-corporate entities is the responsibility of the company’s Board of Directors. The Board manages relationships with other corporations, makes deals, and signs contracts and statements of intent. These documents should all include security expectations and include signatures of responsible executives. When security policy is violated by partner companies, the Board of Directors should hold those companies responsible and take appropriate business measures to correct the problem.

Enforcement of the corporate security policy for employees and temporary workers is usually the direct responsibility of Human Resources. HR implements punitive actions up to and including termination for serious violations of security policy, and it also attempts to correct behavior with warnings and evaluations. Positive reinforcement can also be enacted by HR, in the form of financial bonuses and other incentives.

All employees, without exception, should be held to the same standards of policy enforcement. It is very important not to discriminate or differentiate between employees when enforcing policy. This is especially true of management. Managers, especially senior managers and corporate executives, should be just as accountable as regular employees—perhaps even more so. Senior management should set an example of right behavior for the rest of the company, and perhaps should be held even to a higher standard than those employees who work for them. When management violates trust or policy, how can employees be expected to adhere to their expectations? By paving the way with high standards of conduct, management helps encourage compliance with the standards of behavior they have set for the employees.

Software can sometimes be used to enforce policy compliance, preventing actions that are not allowed by the policy. One example of this is web browsing controls such as web site blockers. These programs maintain a list of prohibited web sites that is consulted each time an end user attempts to visit a web site. If the attempt is made to go to one of the prohibited sites, the attempt is blocked.

Software-based enforcement has the advantage that employees are physically unable to break the rules. This means that nobody will be able to violate the policy, regardless of how hard they try. Thus, the organization is assured 100 percent policy compliance. Software enforcement is the easiest and most reliable method of ensuring compliance with security policy.

There are some disadvantages to software enforcement as well. One disadvantage is that employees who are grossly negligent or willful policy violators (bad seeds) will not be discovered. Some companies want to weed out these people from their staff, so their employees will consist of mostly honest, hard-working people. With software-based enforcement, it is harder to discover the time wasters, who may find other, less apparent ways of being inefficient. Another disadvantage of automated enforcement is that it may cause disgruntlement and unhappiness among employees who feel that the company is constraining them, making them conform to a code of behavior with which they do not agree. These employees may feel that “big brother is watching them” and may feel uncomfortable with confining controls. Depending on the corporate culture, this may be a more or less serious problem.

Automated enforcement of policy by software can also be circumvented by trusted administrative personnel who have special access to disable, bypass, or modify the security configuration to give themselves special permissions not granted to regular employees. This breach of trust may be difficult to prevent or detect. This is a more general problem that applies to administrative personnel who are responsible for security devices and controls. The best solution is to implement separation of duties, so that violation of trust requires more than one person—two or more trusted employees would have to collude to get around the system.

Regardless of the corporate culture, and how software-based enforcement is used in the organization to control behavior and encourage compliance with the corporate security policy and acceptable use policy, those policies should be well documented and clearly communicated to employees with signatures by the employees indicating that they understand and agree to the terms. Additionally, software-based enforcement, when used, should be only one step in the chain of enforcement techniques that includes other levels, up to and including termination. Companies should not rely solely on software for this purpose; they should have clearly defined levels of deterrence that employees understand. In most companies, employment is an at-will contract between the employer and the employee, and employees should understand that they can lose their job if they try to behave in ways that violate the ethics or principles of the employer. Don’t use software as an excuse or a means of avoiding the difficulties and hardships of enforcement; instead, use it as a tool to accomplish the organization’s enforcement goals.

All information in the company should be classified according to its intended audience, and handled accordingly. This includes paper documents, computer data, faxes and letters, audio recordings, and any other type of information. Classifying this information and labeling it clearly helps employees understand how management expects them to handle the information, and to whom they should expose the information.

Every piece of information is classified into categories like the following:

• Personal Information not company-owned belonging to private individuals

• Public Intended for distribution to and viewing by the general public

• Confidential For use by employees, contractors, and business partners only

• Proprietary Intellectual property of the company to be handled only by authorized parties

• Secret For use only by designated individuals with a need to know

Different categories are appropriate in different circumstances; each company should determine the classifications that are relevant to their unique situation.

The roles and responsibilities for the information classification scheme and its execution are carried out by individuals who have been designated for the handling of each piece of information. These include:

• Data owner

• Data custodian

• Data audience

The data owner is the producer or maintainer of the information contained in the data entity. The data owner assigns the sensitivity level and labels the data accordingly. The data owner has complete authority, responsibility, and accountability for the disposition of their data.

The data custodian is the person who handles the data and carries out the proper distribution and protection of the data in terms of its sensitivity level and handling requirement. The data custodian is responsible for the integrity, confidentiality, and privacy of the data and ensures that it is not damaged, modified, or disclosed inappropriately.

The data audience is the set of people who are designated as valid recipients of the data. These people must ensure that they do not defeat the security requirements of the data by unauthorized handling or disclosure. The data audience is also responsible for the transportation and destruction of the data.

A very important aspect of network security, and one that is often overlooked, is documentation. Documentation is part of each step in the security lifecycle. Documents provide concrete clarification of the security architecture and make the security process well defined.

Documentation records the intent of management and the basis for the decisions that are made in the security infrastructure, and effectively communicates details to those who have a need to know. Undocumented decisions can become lost when employees leave or when new staff arrive. Documentation is essential to the smooth working of any security organization.

Documentation of security projects should conform to the information classification scheme for company proprietary information, and not be disclosed to outside parties. Security documents should include the following components:

• Scope

• Audience

• Business requirements

• Objectives

• Assumptions

• Security details

Documentation can be saved, presented, and change-controlled in a variety of ways. Some companies keep documents on file servers with appropriate permissions to allow security or engineering staff to view documents to which they are entitled. Others use access-controlled intranet web sites that have user accounts to control who can view the documents. Others send documents to appropriate staff via e-mail. Regardless of the specific choice of document distribution and management mechanisms, access controls that implement appropriate authorization levels for creating, viewing, modifying, and deleting documents are essential.

Every company has three security policies: one that is written on paper, one that is in the employees’ heads, and one that is actually implemented on the network. The goal of a security audit is to bring all three of these policies as close together as possible, and try to keep them that way.

A security assessment is a high-level analysis of a company’s current posture with respect to information security. An assessment is not an audit, which is used to test compliance with existing policies and represents a very detailed focus on a particular system or network. An audit is meant to compare where you think you are with where you actually are.

Security audits are periodically performed to compare existing practices against company policy, to validate that expected results match actual results, and to verify the effectiveness of security measures. Security audits can be planned in advance with notification, or they can take the form of undeclared fire drills to simulate actual events.

When examining a network and its associated support infrastructure to assess the relative quality of security, there are several things to consider. Most important is the identification of what is trusted, and what is not. The systems and services that are considered trusted are the most likely routes of compromise, because the untrusted entities will be categorically blocked. Looking at the big picture, and how the various services interrelate, helps to envision the possible avenues of attack. The auditor ends up being in the difficult position of thinking like a hacker, while at the same time thinking about defense strategy. This is as challenging and difficult to perceive as playing chess against yourself.

The security audit represents a high-level review of the security posture of a company’s network, compared to its intended goals enumerated in the security policy. The purpose is to provide the company with a verification of best practices already in place, as well as to identify business practices and specific technical vulnerabilities that expose the network to down time, revelation or loss of confidential information, or corruption of data.

A comprehensive security audit looks for the following factors:

• Redundancy The entire network is subject to failure if any one of its central components fails. Networks should be made robust by the installation of redundant communications lines and equipment.

• Layered defense The network should be protected from external attack by one layer of defense, a firewall, which is kept current with the latest software releases. A second layer of defense against misuse or attack of the network can be accomplished by installing intrusion-detection software on both the firewall and e-commerce systems.

• Physical security The physical security of the network should be assured. Network devices and critical servers should be placed behind locked doors, and access should be carefully controlled.

• Remote access Virtual private network (VPN) connections are considerably more cost-effective and secure than dial-up access, and sometimes than connections to the remote offices. In addition, they allow telecommuters and field personnel security secure access to the network via a secure channel that protects their passwords and access permissions.

• Corporate security policy A corporate security policy should be established that supports the company’s business objectives, and a senior-level executive should be identified to be responsible for implementing and communicating it to all employees. This policy should be kept updated as the business environment evolves, to maintain its value. A manager should also be designated to be responsible for business relations with partners, vendors, suppliers, and service providers, with the authority, accountability, and approval responsibility to manage the activities of these entities with respect to the company’s information resources.

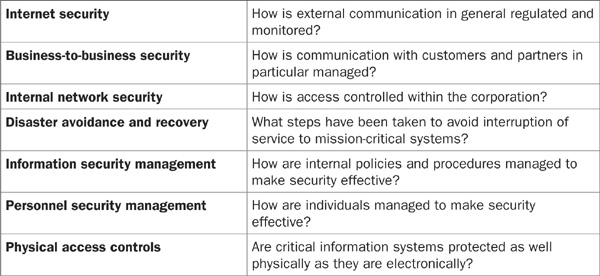

Security can be evaluated in seven overlapping areas:

Security audits help you to better understand the threats your organization is exposed to, and the effectiveness of your current protection. The results should be delivered in a weighted fashion, so management decisions can be made to best manage your risk while not wasting money.

A successful security audit accomplishes the following:

• It determines the exposure of your organization from an outside attack (such as hacking from the Internet or unauthorized access into your modems, fax machines, and voice mail).

• It determines your exposure to threats from the inside, including both accidental and intentional misuse.

• It compares your security policy with the actual practices in place. If a security policy is not in place, a security audit will help identify areas that need attention. In this case, the audit is called an “assessment.”

In most cases, a thorough audit will find several areas where the expectation and the practice do not line up. For those instances where they do, and are consistent with industry best practices, the audit provides a validation of the company’s security infrastructure and practices.

A security audit first identifies where you think you are in terms of current practices, then discovers where you actually are, and finally compares that to industry best practices. The audit effort consists of three phases:

• Review of existing information security policies and procedures in comparison to industry best practices

• Investigation into actual operating procedures, including personnel interviews, site inspection, and internal and external network scans

• Identification of vulnerabilities and recommendations for remediation

The deliverables of a well-performed security audit should include:

• An executive summary that gives an overall score to the organizational security posture and highlights areas that require remediation

• A technical report containing a network diagram, detailed vulnerability analysis, grouped by severity, including an explanation of each vulnerability and specific instructions on remediation, and a comparison of industry best practices to the organization’s policies and procedures, to be reviewed in light of business objectives

• A comparison of actual practices to official policies and best practices, with recommendations for improvement, categorized according to severity and potential impact on the organization

A security audit can detect and recommend solutions for many types of security concerns and management processes. Some examples include:

• Firewalls running different software versions or patch levels

• Firewall resource capacity concerns

• Employees running personal web sites

• Internal hosts exposed to the Internet

• Extranet connections without authentication or access control

• Virus problems

• Backup risks, and change control issues

• Security administration and management

• Telecommunications fraud

• Pirated or illegal software

• Instant messaging software

• Peer-to-peer (P2P) clients and copyright violations

Audit practices typically include interviewing members of the staff, examining log files, and running software vulnerability analysis (VA) programs that don’t use any hacking or denial of service (DoS) tools.

Who should perform the audit? A company can, and should, perform its own internal audits, but without the outside perspective of a third party there is a risk of having a blind spot in some areas, intentional overlooking of weaknesses, or unspoken assumptions that management may not realize. By allowing an external auditor to perform the audit, a company may gain more value from the experience.

Preparation for an audit can consist of as little effort as arranging some time with the key personnel so that interviews can be conducted with the auditor either in person or by phone, and asking the network administration staff for network diagrams and device configuration information. A security audit can take as little as five days (two days on-site investigation, one day performing scans and vulnerability analysis, and two days expert analysis and report writing) for smaller companies. Larger organizations may need more time.

Audits should be done as often as deemed appropriate, because the minute anyone signs off on one configuration, the infrastructure will begin to change. After a period of weeks or months, the audit may no longer be valid due to changes in the environment. For small companies, once a year may be sufficient, while for larger companies, once a month may be necessary. It is also important that the audit results be dealt with in between audits.

Is an audit a penetration test? No. A penetration test uses hacker tools to attempt to actually gain access into systems via their known vulnerabilities. The audit is more focused on the business environment of the enterprise surrounding the systems; it includes a network-based scan that does not attempt to gain access to systems. There should be no disruption of service or risk of data exposure. A penetration test can be performed separately if desired, but not until the results of the audit have been obtained and all identified issues fixed.

A security audit should attempt to present the results in an easy-to-understand format, along with a series of recommendations formulated as an action plan to facilitate the inception of new projects to address the issues that were found.

Most companies, whether large or small, have difficulty achieving a high enough level of information security to comply with industry best practices. Very few companies invest in an internal security organization with enough resources to do everything the company would like to do. Most companies realize this but continue to do business with the hope that nothing bad will happen.

However, more companies are beginning to recognize the value of outsourcing services that are not central to their core business. It’s rare for modern businesses to hire their own cafeteria staff, or housekeeping staff, or in many cases even their payroll. It would be unthinkable for most companies to maintain a force of air transportation. Now, other types of services are beginning to come under the same scrutiny for efficiency, quality, and cost-effectiveness.

Managed security services, outside firms contracted by companies to perform specific security tasks, are becoming increasingly popular and viable for modern companies. These firms are companies that hire specialized staff with expertise in focused areas such as firewall management, intrusion-detection analysis, and vulnerability analysis and remediation. Often, these companies are able to hire specialists that are more advanced than what other companies can afford, because of their specialization. Their customers are then able to gain access to this expertise without having to pay the salaries and infrastructure costs, which are absorbed by the managed service providers (MSPs).

There are three good reasons to look to an information security provider for outsourced services:

• Security is required 24×7×365.

• Vast amounts of data must be examined.

• Specialized skill sets are hard to find.

A security infrastructure requires constant vigilance. It’s not enough to rely on automated software that can be tricked, or might crash, or may overlook important scenarios. A human intelligence is needed to analyze activity and make decisions on the spot. It’s not enough to have one person with a pager—three shifts are required. Moreover, intruders don’t take vacations.

Identifying security threats and making decisions about how to respond involves sifting through log files, network activity, and configurations. False alarms are common—one system communicating legitimately with another may appear to be an attack, or a system administrator performing a routine upgrade may look like an intruder. Somebody needs to be able to make decisions.