This chapter will focus on using routers and switches to increase the security of the network as well as provide appropriate configuration steps for protecting the devices themselves against attacks. Cisco routers are the dominant platform in use today, so where examples are provided, the Cisco platform will be discussed. This does not mean that Cisco is the only platform available—routers and switches from leading companies, such as Juniper Networks (www.juniper.net), Foundry Networks (www.foundrynetworks.com), and Extreme Networks (www.extremenetworks.com), perform similar if not identical functions.

The next chapter will discuss firewalls and their ability to filter TCP/IP traffic—firewalls decide what traffic is permitted to enter and exit a given network. While firewalls can be thought of as the traffic cops of the information superhighway, routers and switches can be thought of as the major interchanges and the on and off ramps of those highways.

The dominant internetworking protocol in use today is the Transmission Control Protocol/Internet Protocol (TCP/IP). TCP/IP provides all the necessary components and mechanisms to transmit data between two computers over a network. TCP/IP is actually a suite of protocols and applications that have discrete functions that map to the Open Systems Interconnection (OSI) model. The OSI model is discussed in greater depth in Chapter 11—for this chapter, we are primarily concerned with TCP/IP functions at the second and third layers of the OSI model, commonly known as the data-link and network layers respectively.

Each computer on a network actually has two addresses. A layer two address known as the Media Access Control (MAC) address, and a layer three address known as an IP address. MAC addresses are 48-bit hexadecimal numbers that are uniquely assigned to each network card by the manufacturer. Each manufacturer has been assigned a range of MAC addresses to use, and each one that has ever been assigned is unique. IP addresses are 32-bit numbers assigned by the network administrator, and they allow for the creation of logical and ordered addressing on a local network. Each IP address must be unique on a given network.

To send traffic, a workstation must have the destination workstation’s IP address as well as a MAC address. Knowing the destination workstation’s hostname, the IP address can be obtained using protocols such as Domain Name Service (DNS) or Windows Internet Naming Service (WINS). To ascertain a MAC address, the computer uses the Address Resolution Protocol (ARP). ARP functions by sending a broadcast message to the network that basically says, “Who has 192.168.2.10, tell 192.168.2.15.” If a host receives that broadcast and knows the answer, it responds with the MAC address: “ARP 192.168.2.10 is at ab:cd:ef:00:01:02.”

For traffic destined to nonlocal segments, the MAC address of the local router is used. MAC addresses are really only relevant for devices that are locally connected, not those that require packets to travel through layer three devices, such as routers. Also note that no authentication or verification is done for any ARP replies that are received. This facilitates an attack known as ARP poisoning, discussed later in this chapter.

NOTE This is a very simplified review of TCP/IP. For a complete discussion, read TCP/IP Illustrated, volumes 1 and 2, by Richard Stevens.

From a network operation perspective, switches are layer two devices and routers are layer three devices (though as technology advances, switches are being built with capabilities at all seven layers of the OSI model).

Switches are the evolving descendents of the network hub. Hubs were dumb devices used to transmit packets between devices connected to them, and they functioned by retransmitting each and every packet received on one port out through all of its other ports. This created scalability problems, because as the number of connected workstations and volume of network communications increased, collisions became more frequent, degrading performance. A collision occurs when two devices transmit a packet onto the network at almost the exact same moment, causing them to overlap and thus mangling them. When this happens, each device must detect the collision and then retransmit their packet in its entirety. As more and more devices are attached to the same hub, and more hubs are interconnected, the chance that two nodes transmit at the same time increases, and collisions became more frequent. In addition, as the size of the network increases, the distance and time a packet is in transit over the network also increases, making collisions more likely again. Thus, it is necessary to keep the size of such networks very small to achieve acceptable levels of performance.

To overcome the performance shortcomings of hubs, switches were developed. Switches are intelligent devices that learn the various MAC addresses of connected devices and will only transmit packets to the devices they are specifically addressed to. Since each packet is not rebroadcast to every connected device, the likelihood that two packets will collide is significantly reduced. In addition, switches provide a security benefit by reducing the ability to monitor or “sniff” another workstation’s traffic. With a hub, every workstation would see all traffic on that hub; with a switch, every workstation will only see its own traffic.

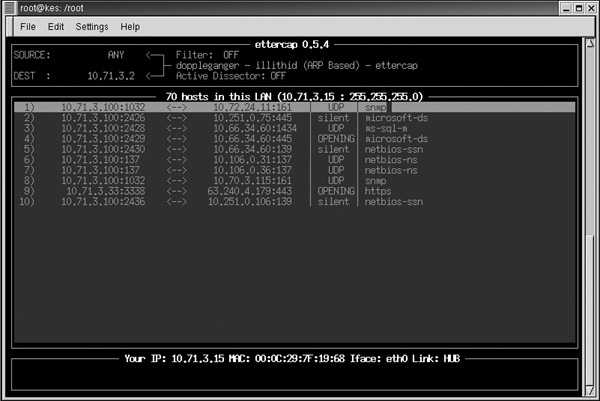

A switched network cannot absolutely eliminate the ability to sniff traffic. A hacker can trick a local network segment into sending it another workstation’s traffic with an attack known as ARP poisoning. ARP poisoning works by forging replies to ARP broadcasts. For example, suppose malicious workstation Attacker wishes to monitor the traffic of workstation Victim, another host on the local switched network segment. To accomplish this, Attacker would broadcast an ARP packet onto the network containing Victim’s IP address but Attacker’s MAC address. Any workstation that receives this broadcast would update its ARP tables and thereafter would send all of Victim’s traffic to Attacker. This ARP packet is commonly called a gratuitous ARP and is used to announce a new workstation attaching to the network. To avoid alerting Victim that something is wrong, Attacker would immediately forward any packets received for Victim to Victim. Otherwise Victim would soon wonder why network communications weren’t working. The most severe form of this attack is where the Victim is the local router interface. In this situation, Attacker would receive and monitor all traffic entering and leaving the local segment. While ARP poisoning attacks appear complicated, there are several tools available that automate the attack process, such as Ettercap shown in Figure 10-1 (http://ettercap.sourceforge.net) and HUNT (http://lin.fsid.cvut.cz/~kra/index.html#HUNT). The figure shows an attacker using Ettercap to ARP poison the local segments default gateway on a switched network.

To reduce a network’s exposure to ARP poisoning attacks, segregate sensitive hosts between layer three devices or use virtual LAN (VLAN) functionality on switches. For highly sensitive hosts, administrators may wish to statically define important MAC entries, such as the default gateway. Statically defined MAC entries will take precedence over MAC entries that are learned via ARP.

FIGURE 10-1 Ettercap spoofing the default gateway

Routers operate at layer three, the network layer of the OSI model, and the dominant layer three protocol in use today is Internet Protocol (IP). Routers are primarily used to move traffic between different networks, as well as between different sections of the same network. Routers learn the locations of various networks in two different ways: dynamically via routing protocols or manually via administratively defined static routes. Networks usually use a combination of the two to achieve reliable connectivity between all necessary networks.

Static routes are required when a network can’t or shouldn’t be directly learned via a routing protocol. For example, firewalls do not normally run routing protocols. This is done to ensure that a firewall is not tricked into routing traffic to an attacker. If a firewall is not informing the network of any networks behind it, those routes must be statically added to a network router and propagated. Additionally, static routes can be added for any interconnected network that cannot or does not communicate with the routing protocols on the network.

Controlling which devices can advertise routes for your network is an important security concern. Rogue or malicious routes in the network can disrupt normal communications or cause confidential information to be rerouted to unauthorized parties. While a number of routing protocols, such as Routing Information Protocol version 2 (RIPv2), Open Shortest Path First (OSPF), and the Border Gateway Protocol (BGP), can perform authentication, a common method is to disable or filter routing protocol updates on necessary router interfaces. For example, to disable routing updates on the first Ethernet interface of a Cisco router, issue the following command:

![]()

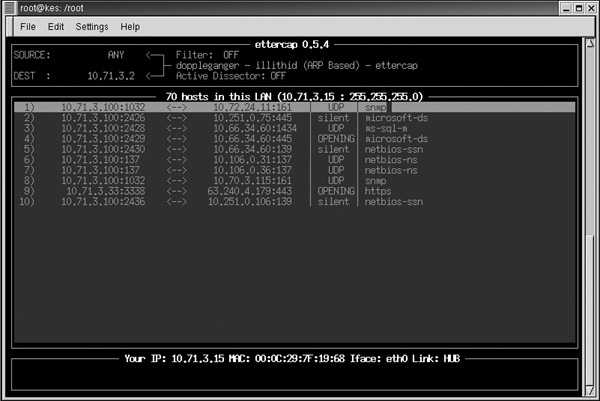

This is useful if no routing information should be received or sent out this interface. However, this is not useful if some routing updates should be permitted and others blocked. When such a situation is encountered, distribution lists can be used. In the following example, routing updates for the router will be permitted inbound from the 10.108.0.0 network and outbound to the 10.109.0.0 network.

NOTE Cisco routing lists all end with an implicit drop, meaning that all traffic that is not specifically allowed will be dropped when an ACL is applied.

There are two main types of routing protocols: distance-vector and link-state protocols. The main difference between the two types is in the way they calculate the most efficient path to the ultimate destination network.

Distance-vector protocols are more simplistic and are better suited for smaller networks (less than 15 routers). Distance-vector protocols maintain tables of distances to other networks. Distance is measured in terms of hops, with each additional router that a packet must pass through being considered a hop. The most popular distance vector protocol is RIP.

Link-state protocols were developed to address the specific needs of larger networks. Link-state protocols use link-speed metrics to determine the best route to another network, and they maintain maps of the entire network that enable them to determine alternative and parallel routing paths to remote networks. OSPF and BGP are examples of link-state protocols.

For networks to function properly, all network devices must maintain the same view or topology of the network, and the process by which routers come to agree upon the network topology is called convergence. Distance-vector and link-state protocols use different mechanisms to converge. The ability of a routing protocol to detect and respond to changes in network topologies is a significant advantage over the use of static routes.

However, when networks are unstable, such as just after a failure, or when network devices have different views of the topology, network routing loops can occur. A routing loop occurs when two routers decide that the best path to a given network is only available via each other, meaning that Router A believes the best route to a network is available via Router B, and at the same time Router B believes that the best route to the same network is only available via Router A. Thus, Router A will forward all packets received for that network to Router B, which will in turn forward them right back to Router A, preventing them from ever reaching their destination.

Each routing protocol has different mechanisms by which they detect and prevent routing loops. For example, a process called split horizon instructs the RIP routing protocol not to advertise a route on the same interface that it learned the route. Another RIP mechanism is a hold-down timer, which instructs a router to not accept additional routing updates for a specified period. This is useful while the network is unstable immediately following a topology change.

Distance-vector protocols do not perform any proactive detection of their neighbors. They are configured to learn their directly connected neighbors and to periodically send and receive their entire routing tables to each other. Topology changes are detected when a router fails to receive a routing table from a neighbor during the required interval. Link-state protocols establish formal connections to their neighbors, and topology changes are automatically detected when a connection is lost.

The choice of routing protocol does not have a large impact on network security. As mentioned, controlling where and with whom routing information is exchanged is usually a sufficient security practice on a given network. When choosing a routing protocol, be sure it meets the needs of your anticipated network size, because once deployed, switching protocols is a prohibitively expensive and time-consuming process. For high-security network devices, such as firewalls, it is more secure to define all routes statically, ensuring that the firewall is not vulnerable to a routing protocol attack. With these devices, the number of routes is likely to be very small, alleviating the need to run a dynamic routing protocol.

There are a number of configuration steps that can be taken to ensure the proper operation of your routers and switches. These steps will include applying patches as well as taking the time to configure the device for increased security. The more steps and time taken to patch and harden, the more secure it will be. The various steps that are available in a Cisco environment are detailed in the following sections.

Patches and updates released by the product vendor should be applied in a timely manner. Quick identification of potential problems and installation of patches to address newly discovered security vulnerabilities can make the difference between a minor inconvenience and a major security incident. To ensure you receive timely notification of such vulnerabilities, subscribe to your vendor’s e-mail notification services, as well as to general security mailing lists. The following are links to some popular lists.

• BugTraq www.securityfocus.com/popups/forums/bugtraq/intro.shtml

• CERT www.cert.org

• Cisco www.cisco.com/warp/public/707/advisory.html

Network nodes are not directly aware that switches handle the traffic they send and receive, making switches the silent workhorse of a network. Other than offering an administrative interface, switches do not maintain layer three IP addresses, so hosts cannot send traffic to them directly. The primary attack against a switch is the ARP poisoning attack described earlier in the “Switches” section of this chapter.

However, the possibility of an ARP attack doesn’t mean switches cannot be used as security control devices. As mentioned earlier, MAC addresses are unique for every network interface card, and switches can be configured to allow only specific MAC addresses to send traffic through a specific port on the switch. This function is known as port security, and it is useful where physical access over the network port cannot be relied upon, such as in public kiosks. With port security, a malicious individual cannot unplug the kiosk, plug in a laptop, and use the switch port, because the laptop MAC will not match the kiosk’s MAC and the switch would deny the traffic. While it is possible to spoof a MAC address, locking a port to a specific MAC creates a hurdle for a would-be intruder.

Switches can also be used to create virtual local area networks (VLANs). VLANs are layer two broadcast domains, and they are used to further segment LANs. As described earlier, ARP broadcasts are sent between all hosts within the same VLAN. To communicate with a host that is not in your VLAN, a switch must pass the hosts packets through a layer three device and routed to the appropriate VLAN.

Routers have the ability to perform IP packet filtering (packet filtering is discussed in detail in Chapter 11). Access control lists (ACLs) can be configured to permit or deny TCP and UDP traffic based on the source or destination address, or both, as well as on the TCP or UDP port numbers contained in a packet. While firewalls are capable of more in-depth inspection, strategically placed router ACLs can increase network security. For example, ACLs can be used on border routers to drop obviously unwanted traffic, removing the burden from the border firewalls. ACLs can also be used on WAN links to drop broadcast and other unnecessary traffic, thus reducing bandwidth usage.

A simple ACL in a Cisco router could be implemented with the following commands:

![]()

This basic ACL tells the router to disallow HTTP sessions with a source address of 10.1.2.3 to all destinations. The second line of the ACL permits all other traffic.

To enforce this ACL, it must be applied to an interface with the access-group command:

![]()

As with general purpose operating systems, routers run services that are extraneous to the process of routing packets. Taking steps to disable and protect such services can increase the overall security of the network.

Proxy ARP allows one host to respond to ARP requests on behalf of the real host. This is commonly used on a firewall that is proxying traffic for protected hosts. Cisco routers have Proxy ARP enabled by default, and this may allow an attacker to mount an ARP poisoning attack against a host that is not on the local subnet or VLAN.

To disable Proxy ARP on the first Ethernet interface of a Cisco router, issue the following commands while in configuration mode:

![]()

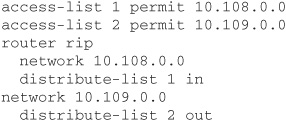

The Cisco Discovery Protocol (CDP) is a layer two protocol that enables Cisco routers and switches to locate and identify neighboring routers and switches. CDP packets contain information such as router IP addresses and software versions. An attacker who views such packets can gain valuable knowledge about network routers.

CDP can be disabled on a global or per-interface basis. To disable it globally enter the following commands:

Cisco routers provide a number of services that can be disabled if they are not needed. The following is a list of such services with instructions on how to disable them. These commands must be issued from configuration mode, accessed via the enable and config t commands.

• Diagnostic servers Cisco routers have a number of diagnostic servers enabled for certain UDP and TCP services, including echo, chargen, and discard. These services can be disabled by issuing the following commands:

![]()

• BOOTP server A Cisco router can be used to provide DHCP addresses to clients through the BOOTP service. This can be disabled by issuing this command:

![]()

• TFTP server The Cisco Trivial File Transfer Protocol (TFTP) server can be used to simply transfer configuration files and software upgrades to and from the router. However, TFTP does not provide authentication or authorization services for its use. Most administrators run a TFTP server external to the router and enable it as needed. To disable the internal router TFTP server issue this command:

![]()

• Finger server The finger service can be queried to see who is logged in to the router and from where. To disable this source of information leakage, disable finger by issuing this command:

![]()

• Web server Cisco also provides a web server for making configuration changes. If the router will not be managed in this manner, the web server can be disabled with this command:

![]()

These services pose security risks to the normal operation of the router while they are running. For example, Cisco has indicated that it is possible to create a denial-of-service situation with a router running the diagnostic servers. The attack is mounted by sending a large number of requests to echo, chargen, and discard ports from phony IP addresses. Each connection to the router will consume a small amount of CPU time, and if the router is overwhelmed by such requests, they will potentially consume 100 percent of the CPU, degrading performance for other services. Other attacks against these services have been discovered, including one against the Cisco TFTP server. Thus, disabling extraneous services offers protection against newly discovered flaws in these services.

NOTE Additional information on the denial-of-service attack can be found at www.cisco.com/warp/public/707/3.pdf. The TFTP bug is documented at www.cisco.com/warp/public/707/ios-tftp-long-filename-pub.shtml.

Cisco routers have a number of methods by which they can be managed. A command-line interface is accessible directly from a console or remotely via either Telnet or the Secure Shell protocol (SSH). Additionally, a web interface can be accessed via a browser, or the router can be monitored and managed via the Simple Network Management Protocol (SNMP). It is important to adequately secure these services to provide adequate protection against attack.

Another important step when hardening network devices is to configure a banner that is displayed whenever a connection is established as part of the login process. In addition to removing important information that may identify the type and operating system on the device, it is good practice to display a warning message regarding unauthorized use of the device. This ensures that an individual cannot argue that they didn’t know that their use was unauthorized. Cisco login banners can be configured with this command:

![]()

NOTE By using information obtained from banners, such as the operating system version, attackers may identify relevant attacks against the device.

An overall weakness of Telnet is that it cannot protect communications while they are in transit over the network. As a more secure alternative, Cisco routers running version 12.1 or later of the Cisco Internetwork Operating System (IOS) support the Secure Shell Protocol version 1. SSH provides the same interface and access as Telnet, but it will encrypt all communications. Failure to encrypt administrative connections to network routers may allow an attacker to capture sensitive information, such as passwords and configuration parameters, while they are in transit over the network.

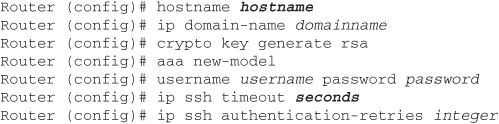

To enable SSH, it is necessary to configure host and domain names on the router, generate an encryption key, configure accounts, and set required SSH parameters. The commands to complete the configuration on a Cisco router are as follows:

The following command output can be used to verify that SSH has been configured and is running on the router:

By default, Cisco devices maintain one password to access the device and a second password to access configuration commands, commonly called enable access. However, to provide accountability, individual user accounts can and should be created. Individual accounts are created with the username command. Even if individual accounts will be used, be sure to change the passwords for any default accounts from their default values.

Locally stored account information will be stored in clear text unless otherwise configured. Cisco routers use two methods of encryption: Level 7 and Secret encryption. Level 7 encryption is really just a simple obfuscation technique, and it can be decrypted with a simple utility available at www.atstake.com/research/tools/password_auditing/cisco.zip. The Secret level of encryption uses a reliable MD5 hash function to obfuscate the password. Secret protection can be enabled through the enable secret command. Unfortunately, not all stored passwords can be protected with enable secret. For example, passwords used for TTY connections (such as Telnet and SSH) can only be protected with Level 7 encryption.

To determine the type of encryption used, examine the router configuration file. For example, passwords obfuscated with Level 7 encryption will contain a line like this:

![]()

Passwords encrypted with the stronger Secret level of encryption will look like this:

![]()

In large-scale environments, it is cumbersome to synchronize and maintain individual user accounts on each network switch and router. To simplify account management, Cisco routers can be configured to authenticate against a central account repository; this also removes usernames and passwords from local configurations. The process of authentication uses either Terminal Access Controller Access Control System (TACACS) or Remote Authentication Dial-In User Service (RADIUS) servers. TACACS has actually evolved over time, and the current version in use is TACACS+. There are a number of operational differences between the two systems, but both provide robust authentication and authorization services. The decision about which is implemented is mostly based on convenience and comfort level.

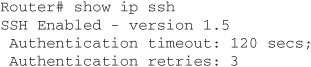

To enable TACACS+ authentication on a Cisco router, follow these steps:

1. Enable Cisco authentication, authorization, and accounting services, which contain the TACACS+ services, by issuing the following command:

![]()

2. Specify the location of the TACACS+ account database and a shared key to use for encrypting communications (be sure to use the same key on the TACACS+ server). This is done with these commands:

![]()

3. Associate the various access methods to be used with TACACS+. This is done with this command:

![]()

For example, to configure TACACS+ as the default authentication method using a server at IP address 10.1.11.50 and a shared secret of S3cur1ty, the following commands would be used:

Authentication to the router should not rely completely on a remote authentication server. Should the server be down or unavailable, no one could log in. Therefore, keeping a local backup account is a good precautionary measure. Additionally, the router can be configured to permit a login with the enable password with this command:

![]()

Beyond simply authenticating access to the router, it is good practice to limit the locations from which such connections can be initiated. For example, why permit Telnet or SSH sessions to the border routers from external networks, or to core routers from the entire internal network? Administrators can configure ACLs to restrict administrative access to authorized hosts and subnets. ACLs are packet filters that will either accept or deny packets based on the packets’ layer three header information. Packet filters are discussed in more detail in Chapter 11.

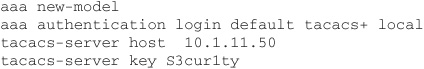

The following example creates an ACL that permits Telnet and SSH traffic from a single administrative host to the router interface at 10.1.10.1. It then denies Telnet and SSH to the router from all other hosts while permitting all other IP traffic.

Once created, the access list must be applied to an appropriate interface:

![]()

Cisco routers can also be monitored and managed via SNMP, which provides a centralized mechanism for monitoring and configuring routers. SNMP can be used to monitor such things as link operation and CPU load. In addition, managed devices can alert personnel to detected problems by sending traps to configured consoles. Traps are unsolicited messages that a device will send when a configured threshold is exceeded or a failure occurs. SNMP consoles can be used to proactively monitor network devices and generate alerts if connectivity is lost.

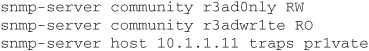

The following commands will configure SNMP community strings, as well as configure SNMP traps with a network management host:

NOTE One very important step when configuring SNMP strings is to change them from their default values of public for Read Only (RO) and private for Read Write (RW).

To further protect SNMP communications, configure an ACL on the interface containing the following commands to permit SNMP traffic from the management hosts:

![]()

Historically, SNMP has also posed a significant security risk. SNMP traffic, including authentication credentials, were not encrypted. Authentication consisted of a community string, and many implementations did not change them from the defaults of public for read access and private for write access. Addressing these weaknesses, SNMPv3 has been developed, and it includes a number of security features, such as encryption, message integrity functions, and authentication of traffic. SNMPv3 should be used wherever possible, and for devices not being managed or monitored via SNMP, it should be disabled.

The Internet Control Message Protocol (ICMP) provides a mechanism for reporting TCP/IP communication problems, as well as utilities for testing IP layer connectivity. It is an invaluable tool when troubleshooting network problems. However, ICMP can also be used to glean important information regarding network topologies and available host services.

ICMP is defined by RFC 792, which details many different types of ICMP communications, commonly known as messages. The following paragraphs will describe relevant ICMP functions and the various risks they pose when used for malicious purposes.

Echo requests and replies, more commonly known as pings, are used to determine if another host is available and reachable across the network. If one host can successfully ping another host, it can be concluded that the hosts have proper network operation up to and including layer three of the OSI model.

An attacker can use ping to scan publicly accessible networks to identify available hosts, though more experienced hackers avoid ping and use more stealthy methods of host identification. Another use of ICMP echo and echo reply has been to create covert channels through firewalls. ICMP echo requests and replies should be dropped at the network perimeter.

Traceroute is also used to troubleshoot network layer connectivity by mapping the network path between the source and destination hosts. Traceroute is useful in pinpointing where along the network path any connectivity troubles are occurring.

Traceroute works by sending out consecutive packets with the time to live (TTL) field incremented by one each time. When a network device routes a packet, it always decreases the TTL by 1. When a packet’s TTL is decreased to zero, it is dropped, and an ICMP TTL Exceeded message is returned to the sender. This prevents packets from bouncing around networks forever. For example, a host can send out ICMP packets with TTLs of one, two, and three to identify the first three routers between itself and a destination.

In the hands of an attacker, TTL packets can be used to identify open ports in perimeter firewalls. Using this technique, attackers have devised a method for scanning networks using UDP, TCP, and ICMP packets that expire one hop beyond the perimeter firewall. The attack relies upon receiving ICMP TTL Exceeded messages from firewalled hosts, so dropping TTL Exceeded packets can defend against such attacks. The popular tool used in this kind of attack is called firewalk (www.packetfactory.net).

Another type of ICMP message is a Type 3 Destination Unreachable message. A router will return an ICMP Type 3 message when it cannot forward a packet because the destination address or service specified is unreachable. There are over 15 different types of codes that can be specified within the ICMP unreachable message, and the more popular ones are outlined in Table 10-1.

TABLE 10-1 ICMP Unreachable Code Types

While these messages may seem necessary for proper network operation, a malicious individual can use these message types to determine available hosts and services on the network. It is a good practice to drop all ICMP unreachable messages at the border of the network by using the following Cisco command from an interface configuration prompt:

![]()

There is an important consequence to dropping all unreachables. Code Type 4 is a very important message for proper network operation, and disruptions can occur if hosts cannot be informed that the packets they are sending into the network exceed the maximum transmission unit (MTU) of your network.

The first and last IP address of any given network are treated as being special. These addresses are known as the network and the broadcast addresses, respectively. Sending a packet to either of these addresses is akin to sending an individual packet to each host on that network. Thus, someone who sends a single ping to the broadcast address on a subnet with 75 hosts will receive 75 replies.

This functionality has become the basis for a genre of attacks known as bandwidth amplification attacks. Examples of tools that use this attack are known as smurf and fraggle. In a smurf attack, the attacker sends ICMP traffic to the broadcast address of a number of large networks, inserting the source address of the victim. This is done so that the ICMP replies are sent to the victim and not the attacker. Directed broadcasts can be disabled with this command:

![]()

ICMP redirects are used in the normal course of network operation to inform hosts of a more efficient route to a destination network. This is common on networks where multiple routers are present on the same subnet. However, a malicious user may be able to manipulate routing paths, and redirects should be disabled on router interfaces to untrusted and external networks.

To disable redirects on a particular interface, enter configuration mode for that interface and issue this command:

![]()

An attack used against networks is to insert fake or spoofed information in TCP/IP packet headers in the hopes of being taken for a more trusted host. Address spoofing is an attempt to slip through external defenses by masquerading as an internal host, and internal packets should obviously not be arriving inbound on border routers. Dropping such packets protects the network against such attacks, and border routers can be used to drop inbound packets containing source IP addresses matching the internal network. Additionally, routers should also drop packets containing source addresses matching RFC 1918 “private” IP addresses and broadcast packets.

In addition to spoofed packets, routers should be configured to drop packets that contain source routing information. Source routing is used to dictate the path that a packet should take through a network. Such information could be used to route traffic around known filters or to cause a denial of service situation by forcing large amounts of traffic through a single router, overloading it. To disable source routing globally on a Cisco router, issue this command from a configuration prompt:

As with any device, it is a good idea to maintain logs. Routers are able to log information related to ACL activity as well as system-related information. Cisco routers do not have large disks for locally logging information about network and system activity, but they do provide facilities for remote logging to a Syslog server. In addition, the syslog facilities allow for the centralization and aggregation of all the dispersed network logs into a single repository.

To enable logging to a server located at 10.1.2.3 from a Cisco Catalyst switch, issue the following commands:

![]()

Routers and switches provide a number of mechanisms that, when properly implemented, increase the overall security and performance of the local network. Merely replacing old network hubs with switches can provide a significant performance increase. Once implemented, switches reduce the risk of sniffing-based attacks against other local workstations, and they can further reduce such risks through the strategic implementation of VLANs. Routers provide the ability to implement ACLs to screen and drop unwanted traffic. In addition, taking the time to harden the router against attacks will also increase the security of the network. This chapter also touched upon the various ICMP message types and the risks they pose. Proactive control of ICMP can prevent an attacker from learning significant information about network topologies.