10 Puella Bondinis

Agent Provocateur

B oth within and beyond the borders of carnivorous Asia, the visage of the tiger is a splendor reserved for the gods of death. In the warrior cult of India, the nuptials of Kali and the tiger form a chapter in the story of the gods’ appetite for the twin attributes of power and animality. The hybrid history of warrior transformation has perpetrated both psychological and graphical outrages, such as the stele raised by Ashurbanipal the Assyrian, which tells of the time following a great flood when lions and tigers roamed the Earth, filling it with their deadly attributes (the tiger is tiger to both man and tiger). Samson dealt death to a lion, and Heracles did the same to that of Nemea; both took home the bones. Jehovah sent tigers and lions against the Assyrians who’d occupied Samaria—but after the slaughter, Jehovah claimed invisibility for the cult that worshipped him and would unify his clan. Kali, in contrast, accepts as offerings the heads of his fellow tigers, and of the thousand soldiers torn apart in battle.

The Deer Woman, escaping from her fellow humans each night to copulate with antelope; in the Mahabharata, Rama calls on the gods to mate with monkeys and bears to produce superhuman warriors with the speed of the wind and the strength of the elephant: these are scenes from a secret threaded through all eras and all men. Thus, congress with savages is part of the core story of the Theory of Egoic Transmissions.

–Who is she that advanceth through the night?

1.

The area in question is an elegant neighborhood in the capital, known most recently by the oxymoronic moniker Palermo Manhattan. A summer night. The slight separation between me and the world consists of a black knee-length skirt, a green satin blouse, and short, badly scuffed leather boots. I never wear nylons, they discredit my skin. My underwear is of violet lace, and I’m wearing it only for the company—granting access of that type isn’t part of the plan.

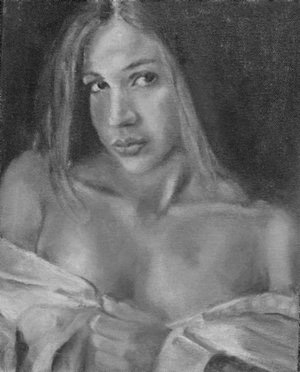

Timide à mes heures, all descriptions of my physical charms have thus far been superficial when not inextant. The reader must not allow the radiance described below to blind him or her as regards the matter at hand; instead it must shine a clear light on the importance of the drama to come. That is, I am now obliged to speak of my beauty.

My skeletal structure is flawless and persuasive, often inescapably so, at least according to the occasional desperate snouts of big boys, old men, and the sapphic. I am most elegantly distributed, my flesh unfolds in a soft, glowing imprecise skin tone between olive-gold and the lyrical ivory of Byzantium. My other parts yield commentaries of varied tenor and quantities of saliva pursuant to issues of innate distinction and Buenos Airean loveliness: my black hair begins its plunge into the void, then restrains itself with unction an instant before reaching my hip; my eyes are black and deep, slightly crossed; my mouth is orthodox, red. Seen from the front, the eminent twin towers rise spiritedly below a fine Doric neck, and the jawline of a lady carnivore. From behind, of course, matched anatomical glories, an intersection of feminine aesthetic and military deployment known, per secula seculorum, in the Biblical sense (mark well the customary insolence of the source). Thus the Singer pontificates upon the fascinating farewell of a lady: Return, return, O Shulamite; return, return, that we may look upon thee. What will ye see in the Shulamite? As it were the company of two armies.

The priceless resources at my disposal only acquired strength as they came to know the enemy by taking Communion with him, in an act of atrocious intimacy. Regarding which, Rodolfo Walsh once wrote:

The main characteristic of enemy intelligence is structural analysis. The determinant factor is a knowledge of our own structure’s political and ideological aspects and its spacial, temporal and relational organization, beginning always from the assumption that in knowing the objectives pursued by one’s adversary, the strengths and weaknesses of their forces, their chains of command, the distribution of their barracks, their logistics and their communications, one knows enough to destroy them if one also possesses superior firepower and mobility.5

By this point the reader will have realized that the experiment herein described required making of my body a laboratory, and also a watchtower from which to direct an assault by land.

The building is early 20th century, with walls of stone. Inside, a large wood-paneled vestibule extends along a set of picture windows that give onto an interior garden of smoky greens. The light dims as I advance toward his dwelling at the end of the corridor. The buzzer sounds—the burp of a mockingbird. Across the hallway, the doorman shrinks back behind the counter when his fish-like gaze meets my sidelong glance, his deftly lipid behavior confirming that he knows he has been warned. He changes the channel on his security monitor; the screen now displays an empty swimming pool.

I hear hurried footsteps, comings and goings inside the apartment. I pull back, and find the perfect angle from which to see the face of my prey as he anxiously opens the door.

The physical reality of Collazo takes me by surprise. He is enormous. Much taller and brawnier than I’d imagined. Too, he is fundamentally uglier, is in fact so startlingly hideous that it burns your eyes, leaves you blinking. Did Collazo have a precursor? Naturally he did: this is why I prepared so carefully for this encounter. In order to find Collazo, I had to scrutinize Augustus’s weaknesses; to analyze the encrypted messages, the hidden details, the reverse side of his sentences; to find, in the course of his classes, a few clues that would lead me to decide it was him, Collazo—him and no one else—that I had to seduce, to lasso with a noose made of women’s hair, to bring in chains before the Old Man for him to gloat over—to take hostage.

Collazo says hello with a feigned indifference. He asks if I had any trouble finding the building; I invent a showdown between taxi drivers and picketers to explain my late arrival. I follow him up the hallway without a word. Dark shirt, knotty shoulders; pants tight over the crotch and at the waist, concealing little. He turns, slowly, to face me, and repeats a question I hadn’t answered; up close, lit by the halogen lights, his face opens out, wider and monstrous. He stands before me, enrobed in the strange glamour common to all veterans of the Dirty War. A huge mustache stretches across his face. The nose, deeply etched; bristly eyebrows that seem to poke at whatever he observes, clawing at clothes, scratching at the skin of things. I interrupt my horror briefly in order to answer him.

He examines me lasciviously from top to bottom, focusing mainly on my middle third. My first clear sensation, separate from all else: the odor that lies in wait beneath his cologne, a layered, tuberous scent of semen enclosed in its mandrake coffer, rancid, sharp, writhing beneath his clothes. The left side of his eel-like mustache lifts to show sharpened fangs.

–Whiskey?

–With ice, thanks.

Collazo paws through a variety of liquors without taking his eyes off of me. He pours two glasses; his body is stout as a head stock boy’s, but his arms can’t be too strong at this point—I don’t think you could say they’ve done much over the past fifty-odd years. He holds out my glass of whiskey; stepping closer to receive it, I sense his gently monstrous radiation. Yellow teeth, violent mouth. I hold my breath, take a drink.

–So you’re in Roxler’s class . . . What did you say it was called?

I go to speak but just then a piece of ice gets caught in my throat. I cough briefly. He seems amused. He asks how old I am. I blurt out a lie—twenty-eight, doing my PhD. Collazo hands me a napkin and a glass of water. The thought occurs that he’s given me the napkin so I’ll have somewhere to spit out the ice cube, and I stop coughing. He looks at my hands around the whiskey glass, and I realize it can’t be hidden: I’m trembling.

–It’s a little cold, isn’t it. I’ll turn up the heat.

Collazo disappears down the hallway and I slip into the bathroom. I lock the door. This bathroom in the center of the house is the lair par excellence, the den of dens. Like a mist swirling up from a lake in which monsters sleep, Collazo’s odor is born herein, his aura, a red stain as seen through a thermal scope. Here he dwells, leaving behind flakes of skin each time he bathes, scabs stuck to the shower walls, spatterings of semen that a woman, someone’s grandma, will be paid to come clean up. There are no thong panties hung like flags, and their absence speaks to a state of desperation, a certain degree of vulnerability that is essential to the success of my mission. I look through the medicine cabinet. A shaving brush, rusty nail clippers, bits of fur here and there (the beast chews at its own hair and spits), and a few colognes from twenty years ago, the bottles almost empty—an ascetic, leftist intimacy. The cracked wall tiles bear traces of recent damp, of rising steam, saliva in larval form. I close the cabinet door.

And there they are, my eyes, guileless, looking back at me from the filthy mirror. The long, long eyelashes, the arched eyebrows shining with determination, and lower, out of view, the labyrinthine organ for which he is willing to lose himself irretrievably. I don’t mean to overemphasize the beauty of these features, but the mirror doesn’t lie, does nothing but show what it sees: in these features, in the moral contrast they offer to the vile and contemptible brutality of Collazo, resides the key to what will bring him to a boil. There is no escape.

I walk quickly out of the bathroom. He’s not in the kitchen; I cross the hallway, look for him in the living room, there’s a small zebra-striped rug, I step onto it but it’s a trap, I slip and fall to the floor. Collazo watches me fall. He comes slowly across the room, as if hoping to get a peek at my panties or something. I hold out one arm, let him lift me to my feet. His fingers leave marks; I show him the red prints of his huge hands pulsing at the surface of my skin. He says: “Very delicate, yes.”

He takes my glass and sets it on a shelf. He smooths his mustache, as if enjoying a brief interlude before consuming me. He takes me by the waist. I try to maintain the distance between us, but it’s futile: everything is saturated with his hideous radiation. I close my eyes, but even so his monstrous features hang before me haloed in blue. His rancid breath, the cologne mixed with sweat, the unconditional mustache, the echo of his eyes, malicious, wallowing about beneath my clothes, that nose pricked by Triassic insects, nostrils like holes in stone. Enough. I must not allow anything to stop me. I disentangle myself from his arms, let myself fall onto the sofa.

Seated now, my legs uncrossed, the heat begins to worm its way up past my knees, reshapes me, tightens, pulls at my mouth—leaves it hanging open as I stare at him. I must be bright red. I cover my face with my hair, peek out to spy on him, and a sensation rises from my stomach. Then I realize that I’ve landed on a cushion whose triangular corner is poking deeply, vilely, in between my buttocks.

Standing there like a shadow stretched over a victim, Collazo examines me in silence. The halogen lights zero in on his bald head like well-trained snipers; the mustache widens to both sides as he smiles. He’s certain that the battle has tilted in his favor, and he ponders, all but obscenely, his theoretical control of the disputed terrain.

–Let’s take a little walk through the woods, he says. The park’s just right over there.

He comes forward, the dark fabric of his shirt filling the lens, a classic cinematographic fade to black.

1.1

Oh, Augustus! The first time you spoke to me under the words, I failed to understand. But you immediately noted my unease, and moved your head impossibly slowly, as if nodding in agreement. You think me excessively prideful, but I assure you that all this time I have suffered a great deal—and I have missed you even more. That is why, before launching my attack, I need to know your state of mind. Don’t let obsessive thoughts bewitch you. Because what I want to say to you (what I howl so that you might hear) has more to do with protecting the courtly synthesis of your legacy than with my negligible, insubstantial, egoic role in the events themselves.

It is a strange world, yes. You must learn that you are alone, even when followed by multitudes. Perhaps, by the grace of Leibniz, there exists some other possible world where you wouldn’t need me. Who knows? Not even Leibniz. Maybe in that other world, your theory and your words and the single arrow that is time would together have been sufficient; you could have pushed forward without my help, conquering spaces and times and it wouldn’t have mattered to me in the slightest because given the rules in such a world, you wouldn’t need me. But that possible world could never really exist; it would be self-contradictory. My new activities have nothing in common with the things I was doing before, which were themselves docile copies of the things I thought I would be doing back when I first entered our house of higher learning, and thus entered your theory, Augustus—your doctrine. Your doctrine, which has changed everything. If you only knew the wild paths my investigations have taken! The seditious spin of the steering wheel of my research! I was focused on baneful things, my dear. Perhaps baneful is not exactly the term I’m looking for, but it’s an adjective that brings to mind the image of an eagle bearing down on its prey. I would love to bombard you with details. If you knew them—and it’s unclear whether or not you’re ever going to find out, still unclear—I know you would be proud of me. Don’t ask me how, but I know. Would you like to know what this is all about? Of course you would. But I’m not going to tell you. Ha-ha, not yet. Don’t get upset. Soon I will see to it that you know entirely too much—soon I will illuminate the dark side of your philosophy.

What were we talking about? Ah yes, that the world-without-me could never exist in any form whatsoever, because my presence is a necessary condition for your theory. It is true, of course, that I can’t have been its efficient cause: you were able to formulate the initial phase of your doctrine all on your own, with no need for me to act directly upon you or it—or perhaps I did, but only in the world of dreams, my dear, where Cinderella theories dance alongside their fairy godmothers! In the world of things, however, things have changed a great deal. You must face this fact, Augustus. Because in the world where your theory exists, where it truly exists, in its purest, most revolutionary form, there too exists The Act—the act that converts your theory into action. The act is thus intrinsic to the doctrine; it is part of it. And if you were to ask how I know this, well, I would answer that I owe it all to you, because I read it in your theory, and in reading it I consummated a rite of initiation at once wondrous and absolute. You have given me a lever with which to move the world, and the only thing that matters to me is learning how to move that lever. I know perfectly well that you love us all equally—but I also know that some of us are more dear to you than others. Some of us understand what is drawing near, ravenous and blood-stained, the vertiginous tiger, and we fear nothing.

The greatest leaders perished precisely when they no longer knew how to revolutionize the revolution they had begun. And you don’t want that to happen, now, do you, my dear? You want your name raised up above the supralunar clouds, where reign the perfect forms of thought, isn’t that so? The change must come from within—from within you. You don’t need much. You only need me. My eyes are closed, and the bubbles are up to my chin. His big gray hand rests on my tawny belly, while his other hand pushes my hair back, his fingers unable to let go. In your mouth I am the plaything of a monster. I let my thoughts swim in the darkness until I can’t hear them any more.

In the afternoon I took position outside a bar called Platón, named for your favorite Greek, and waited for you there. My plan was to allow time to slide past in its usual fashion: faculty members would soon start to arrive individually, each in his or her own form, and sooner or later you too would appear. Every so often, someone who wasn’t watching their step would slip on the sidewalk, their foot now smeared with dog shit. Two hours passed this way.

Over and over I envisioned your arrival, a succession of silent films projected on the filthy white façade of the department building. My transcription:

Augusto García Roxler makes his way up the wet sidewalk, locked deep in conversation with his own thoughts. His gaze suddenly lifts, drawn to the presence of a very pretty gorgeous young woman sitting near the entrance to Casa del Saber. The Professor stops short. He recognizes her immediately: the enigmatic silhouette, modestly half-hidden, is that of none other than his destiny his nemesis his Significant Other his most deeply beloved student. Augustus clears his throat, thinks: Should I speak to her directly? He imagines that this exquisite young woman is probably furious because he hasn’t given her the time of day seems to have ears only for the sycophants that surround him even though he knows that she is the only one for him he owes the most lucid elements of his doctrine entirely to Her. Augustus wants to go to Her, but he’s nothing but an old chickenshit he fears being rejected because he’s such a chickenshit and deep down inside he’s secretly afraid of her and also because he’s nothing but an old chickenshit who’s lost his strength and lets himself be manipulated by the sinister sycophants around him. An unrecognizable voice resounds from off-stage—from within his brain—it shouts something that will determine the outcome of this nightmarish story. Augustus watches her eyes. She turns her swanlike neck, looks back at him. He roots around in one of his shadowy pockets, extracts a wrinkled copy of his notes on my comments in his class, whispers something that we can’t quite catch but its meaning is clear—there are admiring comments penciled in the margins. He looks at her overcome with passion he caresses her with his eyes lowers his glance and cries begging for forgiveness my love, I can’t take it any more, I belong to you as well with destiny in his eyes; he invites her back to his house, and she responds with a mischievous grin to join him at his regular table at Platón for croissants and a cup of tea.

I waited, and waited, and waited, and you never arrived. Was it possible you were wearing a cape that rendered you invisible? Were you already inside when I arrived? None of the beings who prowl the halls of Philosophy and Letters truly exists before nine in the morning. I myself once tried to break this natural law for a few hours, but was abducted by Berni Bleizik from the priory of Metaphysics, famed for his somniferous gifts. After waking from his spell, I saw that my fist had clenched around my crispy butter croissant, crushing it to bits.

I gathered my papers, my books in progress, and crossed the street with my mind made up: I was going to intercept you inside. I almost slipped as I penetrated the department building. Thank goodness I was wearing these army surplus boots, ideal for bad weather:

I threw myself up the stairs, and sniffed around the offices, the research units, the specialized libraries of the fourth floor. I circled through the main library, its reference area, the Periodicals section. I couldn’t rule anything out, even searched for you up on the fifth floor, which was still under construction, thinking that perhaps you were fed up with the pale imitations of Duchamp that populate the faculty bathrooms. I sought you sought you sought you, and found nothing. Which is when I decided to change strategies. I would go to the pay phone on the corner, call the Faculty Lounge, and explain that a bomb was about to go off.

As this wasn’t during midterms or finals, the threat would be taken seriously; it would create a true sense of danger, would foment panic, the building would empty, and you would come out of hiding. I would stay there at the window of your favorite bar, savoring a snack, trying out different Dostoyevskian facial expressions as I watched you escape out through the door to the right with your dear E.G., who’s now a B.M. (Blubbery Minion), the two of you holding hands as you ran, scared shitless. I so enjoyed imagining you vulnerable, frightened, overwhelmed by what had happened, caught in the sniper sights of moi, that I walked slowly to the corner and actually did it. Ha! Pay phones and philosophy have always been strong allies.

They exited the building a few at a time, much as they’d entered it: students, professors, and craft vendors abandoning the abode of the humanities, walking happily along, chatting with whomever happened to be alongside, smiling and laughing. Only the most nubile among them seemed at all excited or scared. Then suddenly I couldn’t believe my eyes, and wanted to claw them out.

You were walking calmly, talking to that woman. B.M. was tucking a bunch of nerdy folders into their binders, and as he went to say goodbye, he likewise exchanged pleasantries with her. She smiled, and TOOK YOU BY THE ARM. The two of you had undoubtedly entered the building together through the parking lot, but had you come in the same car? She pressed a thin book (How to Knit? The dialogues of Foucault and Deleuze?) flat against her brown, knee-length skirt. She said a few words, and YOU APPEARED TO BE LISTENING. Instead of heading for Platón, your habitual watering hole, or Sócrates, your favorite redoubt for more elegant encounters, the two of you wandered over to the cafe on Directorio Avenue—one that isn’t even named after a philosopher. And I followed.

As enraged as Achilles in full Greek rhapsody, I pulled myself up to where I could see in through the window. That woman wiped the tip of her napkin along her rat-like jaw, pretending to listen attentively; her erect nipples aimed at you like bolts on a pair of crossbows; she stared at you, her gaze insane, her eyes made for pretense and lies. She nodded tritely at everything you said, and raised her pinkie as she sipped her tea. And Augustus’s lips moved—no, I’m not talking to you in Second Person any more, not now that you’ve distanced yourself from me—but I wasn’t quite able to make out what he said. My fury was swallowed by my astonishment, but promptly clawed its way back out.

Every battle plan includes a vague but finite number of expected casualties. Wars begin on the day least expected, and thus a Roman with a Greek nose makes his way along some creek on January 10, 49 B.C.; he crosses the Rubicon, and unleashes a civil war. So it goes. One day you make a bomb threat, and in less than an hour you see how you’ve been betrayed. One day you plant, for example, a very special type of bomb (a symbolic bomb), and soon your most substantial contributions (adjectival, metapolitical) sink to their deaths at the hands of an unacceptable triad. Because that woman is unacceptable. From her immoral appearance, you’d think she just stepped off the stage at a cabaret; from her wouldn’t-hurt-a-fly demeanor, you’d think she was some poorly educated housewife leeching off her husband for survival. She may well study Letters. I first noticed her existence one afternoon when I was wandering through the halls before my Special Problems in Ethics class. She had her hair up in a little bun, was wearing a little brown crochet jacket. She was sitting at a table in the bar on the first floor, surrounded by a scruffy little group of students and—I can hear her murmuring now—she was laying out a Tarot spread. At first glance that made perfect sense: with the consolidation of the internal market for handicrafts and bootleg videos, Tarot cards and Occultism wouldn’t be far behind. I walked up, looking as dismissive as possible, and that woman—incapable of resisting the aura of domination that my personality secretes—invited me to cut the deck. The card that appeared was the Tower.

She looked at me, her little rat-like eyes filled with alarm. In her schoolmarm-from-the-capital accent, she said, “The Tower reprezentsh the paradigmsh conshtructed by the Ego, which iz the shum of the shtructursh built by the mind to undershtand the universh.” Someone elbowed her, saying something about Kant, but she rambled on: the Tower represents those who are prone to visions and epiphanies, but when Reality doesn’t conform to their expectations, the Tower is destroyed by the lightning, and they go crazy, become aggressive, tend toward evil. If the Tower is pointing downward, it is digging its own grave; if it points up, perhaps it’s time for the Tower to change its attitude and ideology. (The table she was using was round, and it wasn’t really clear which way the card was pointing.) The Tower symbolizes the passage from the alpha state to the theta state; in the latter, the information produced by the Ego overwhelms all external stimuli, creating what is known as a hallucination. “Which alwaysh impliesh defeat, deshtruction, and catashtrophe,” she added, adjusting her bun.

I felt the same disdain for that woman that I’d felt for one of my first psychoanalysts, whom I’d held hostage in his office until he admitted that not a single one of the idiotic comments he’d made during our session was a properly formed sentence or meaningful proposition. What matters is welcoming each of the tests our fate has in store, facing them with strength and bravery. Here lies my own Rubicon, I said to myself; here between Puan Street and Pedro Goyena. The twenty-four kilometers between the spot where the Rubicon was crossed and the point where it empties into the Adriatic Sea are contained many times over in the immense asphalt skeleton that undergirds the city of Buenos Aires, home of my days, while the bit of world that stretches from Massachusetts to North Carolina corresponds to the Madrilenian lands that saw the first of the heroic deeds of Cervantes’s man of La Mancha: such was the distance, such the trifling creek that separates destiny from Valor. In political philosophy, such occurrences unleash the violence contained in man’s true nature. I looked down; there was water flowing along the gutter.

Do you like music? I bet there’s a ventricle of your Old Man’s heart that adores boleros. Perhaps a few Cuban classics will bring nearer some new variation on our theme:

Qué vale más, yo niña o tú orgulloso,

o vale más, tu débil hermosura.

Piensa bien, que en el fondo de la fosa

llevaremos la misma vestidura.v

And indeed, you will ask yourself, who is worth more? Darling: the answer is found in the extraordinarily delicate syntax that allows one to choose either an alliance between youth and power, or the solitude of the throne. Alone on the throne you will find yourself surrounded by inept fatsos; allied with the power of the novi, you can hold fast to me. The verse is repeated, emptying out into a subtle yet noteworthy conclusion: vestidura becomes sepultura. A very suggestive choice. (Note: there is cruelty in the sovereign nature of Veneration as well.) Who is worth more, a simple girl like me, or you so proud: you must accept the fact (¡piensa bien!) that your beauty is weak, that the grave is near. You must listen to me before it’s too late.

I understand that at your advanced age you might think it best to play your cards close to the chest, to safeguard your power within the department, to act like the Roman testudo as they defended against, and eventually laid waste to, the vast human hordes.

But this is a trap, my dear one, a trap! You cannot and must not trust anyone in those environs. And that woman . . . frankly, I don’t want to discuss her. Advanced age tends to give poor counsel—don’t listen to it. If you do, it will make you feel weak, when in truth you should know that you are strong because you can rely on me. You must have trust in my youth. You think that the presence of that woman and B.M. will protect you, as their brains are nothing more than boils growing on your own. But you are swimming in barracuda-filled waters. I, who have used my own flesh to incarnate each part of your theory, am willing to take the next step, and as many subsequent steps as might be necessary. Do you understand? I know what your theory requires.

We live in such a strange world, my dear, a world so immeasurably yours and mine. Terrible things are going to happen! I will have to do terrible things. Your words have set in motion a secret, inexorable process. I have exchanged the loftiest heights of intellectual speculation for the testing grounds of the abyss. And I must proceed in thusly, Augustus, must seek out the brutality that exists within me, in order to put myself at the service of the Theory-World to which we both pertain. It would surprise you to know that I have one of you in hand. (It would also surprise you to see yourself reflected in his gauche caviar ways.) How I treat the hostage will depend on every word you speak, do you see, my dear? When I’m with him, I’m speaking to you.

I’ll leave you for now with this syllogistic verse that I found myself composing out loud in English as I was putting on my boots to head out to meet my victim6:

All war is based in deception (Cf. Sun Tzu, The Art of War).

Definition of deception: the practice of deliberately making somebody believe things that are not true. An act, a trick or device intended to deceive somebody.

Thus, all war is based in metaphor.

All war necessarily perfects itself in poetry.

Poetry (since indefinable) is the sense of seduction.

Therefore, all war is the storytelling of seduction

and seduction is the nature of war.

2.

“Friday, 10 o’clock, at Guido’s.” Perfect—and I had the good sense to arrive at 10:30 so as not to arouse suspicion. Collazo still wasn’t there.

I decided to wait for him posed daintily at the bar. I kept myself entertained by rereading certain passages—not particularly well-argumented ones—from Fetish, Fascism, and the Collective Imagination: the Masculine Myth of Nationalist Argentina. The lighting was terrible and the background noise was very distracting. The maître d’ kept looking at me with that cheekily depraved expression men reserve for single damsels. I grumblingly gathered myself up and turned my back on him. Then I realized: all of the men were looking at me, their verbs left half-conjugated in their mouths. Suddenly I feared that I was on the verge of bouncing out of my blouse in full view of everyone. Paying close heed to the little libertarian glimpses my outfit allowed, I slowly caressed my torso until my modesty was once again intact.

I later learned that Collazo was already in the restaurant; the good-for-nothing had seen me arrive, and had made a bet with himself as to how long it would take me to go look for him at the tables on the terrace. I’m glad that even at his age he sees well enough to take pleasure in that kind of mischief. I mumbled an awkward hello (automatic courtesies are trivial) and joined him at his grimy little table next to a row of parked cars. He seemed amused to see me. Without wasting a second, he spoke to the waiter with a certain cold attentiveness that I have observed before in similar individuals.

After asking the waiter for a dizzying number of details and clarifications, Collazo leaned back in his chair and gestured as if proctoring an exam. I shrugged, and gave the kind of evil little laugh that the male libido will go far out of its way to hear as angelic. He asked me something about my thesis. I answered at length, looking over at him from time to time through the fog of my aversion. He fingered his thick mustache, at times softly, at times twisting it down to the corners of his mouth and nibbling at it, as if what he had arched above his mouth was a delicious miniature version of me.

The waiter poured the wine for him to try, a Poligny Montrésor, and Collazo nodded his approval. When he noticed that I was singing quietly along with the music, he asked for it to be turned up. It was a marvelous ballad by The Platters, and a careful look through the menu combined deliciously with our smiles.

The waiter divided each dish into two equal portions, but gave Collazo most of the parsley. The tender orange-and-ruby colored slices of meat slid meekly across the white porcelain, accompanied by glazed baby potatoes, almonds and capers. Collazo grinned at me, and I grinned back. I was afraid, of course, but I knew that I had to provoke him if I wanted to see the monster that the theory had in store for me. The Chardonnay was a murmur of pale gold in our glasses, and now . . . en garde! I gave a twist he could not have foreseen, plunging the dagger into the left side of his vanity.

Collazo calmly leaned toward me, his eyebrows stiff with cruelty. I lifted my chin, my narrowed eyes now oblique to his pitifulness. Then I said something so evil that I prefer not to transcribe it here.

He looks at me coldly, as if intending to impale me. He knows that he can’t let his gaze drop to where my cleavage awaits: if I’m able to capture his eyes there, leave him stuttering at the edge of that precipice, my ampleness will render painless what he clearly intends to be an excruciating silence. His face, naked, caught like a bug in glue. My fiery torrent has come calmly to an end at “and what then?” I can see the gray hairs poking out through his shirt front, and above, his wrinkled Adam’s apple now erect. His self-consciousness betrays him. He laughs—it’s just that I’m so funny.

This sort of back-and-forth is essential to my plan. I must provoke him until fury and fascination leave him completely blind, unable to think. That’s when my thoughts will spill in through the syntactical holes in what is, theoretically, his free will, and there will be no saving him then, no escape. For now he sees only the water’s surface, the reflection of his self-portrait as on-stage seducer rocking gently on the waves. He doesn’t know (can’t know) that this ocean is full of heads, thousands of them, heads from my collection (and a few from Augustus’s), all laughing at him. As Sun Tzu once wrote, “if your opponent is of choleric temperament, seek to irritate him.” If he is arrogant, encourage his narcissism. And if he’s in the process of making a mistake (says Napoleon) don’t stop him. In the end Collazo must be the one to throw himself on top of me, and I must cuddle up to him and bear it. I have to, even if it disgusts me so much I can’t breathe.

For the moment, much to my chagrin, this supposed challenge isn’t, strictly speaking, the problem closest at hand. For Collazo, the real problem is the interval (the density, the syntax) between my calm and his silence, one that requires a demonstration of proportional violence. He’ll have to distill a shot of pure acid to wipe this expression off my face, and frankly it is in my interest for him to do so: otherwise that rhetorical burbling of a few moments ago could lead him to believe that I’m after some insignificant little triumph. To attack the argument that my momentary peace is mere solipsistic vanity, Collazo could employ any combination of bodily disdain + a line of reasoning other than the absurd path being laid by what we will call, for now, Impudence, that great maw-softener—if only in the interest of rescuing the delicate project of his own good mood from a nervous date’s awkward outpourings.

Fingering his mustache, Collazo stayed calm. His fork flipped a caper back and forth. Then he punctured it, and looked at my mouth:

–I must say, I’m very impressed that you caught that hidden reference to Marx’s The German Ideology. I didn’t know that people your age (here he ran his tongue across his lips) were still reading things like that.

Of course I made light of the brilliance of my memory, politely minimizing the whole affair. But my hand, deep in my backpack, twitched against the cover of Fetish, with its frenzied photographic collage of haute droite characters. Oh, Collazo could never even imagine my piercing theories on 20th century nationalism! I gently explained that from the moment we entered university, all students were bombarded with the insights of a whole execution wall’s worth of Commies, and that the complete works of both Kautsky and the ex-People’s Commissar for Naval and Military Affairs, Trotsky, were listed among the texts that we had to memorize as we stood in formation during the school’s patriotic ceremonies.

Collazo gestured for me to stop. He squinted beneath his bristly eyebrows, his face gone to stone like the solemn bust of some gauche caviar prince. He let his gaze drift into the distance and said, very slowly, the words of another, phrase by phrase as they flowered in his mind:

–“These innocent . . . and puerile fantasies . . . of the philosophy of the young . . . whose philosophical bleatings only mimic the opinions . . . of the German bourgeoisie, these sheep . . .”

–“These sheep who take themselves, and are taken, to be wolves.”

–It’s been so long since I’ve recited that, he said, taking a bite of glazed potatoes, nodding his thanks. What a great quote. One of my favorite books of the period.

I took advantage of the fact that he was chewing, and added that ever since the Knowledge Industry decided to proclaim itself critical (i.e. since the dernier cri of its blusterings is to fancy itself a critic), humanism has been reduced to the republican version of intellectual purity; in the end, product differentiation is as important for (and within) the academy as it is for the capitalist corporations that academics love to hate. My disquisition, though perhaps a bit nerdy, appeared to have gained me a new, mustachioed adept. I blinked several times and added a few anacoluthons, feigning self-doubt so that he wouldn’t feel diminished (and thereby emasculated) in the face of such a powerful demonstration of argumentative mastery. He acknowledged my commentaries with a laugh.

We were about to start our conversation back up (I’d made a silent bet with myself that this daring warrior would be on the watch for any opportunity to destroy me; only then would I show my fangs) when a profoundly secondary character caught our attention. At the table next to ours, a bottle-blonde with a swarthy past couldn’t quite decide between the suckling pig and the octopus a la gallega. Her pronunciation revealed an accent that would tear itself to shreds on razor wire if the authorities ever found the time to build a fence around Buenos Aires. Given that Menemism had been banned on aesthetic grounds, any excessive yellow in one’s pileous hue was now seen as shameless, and the woman’s blatherings, which included scattered capitalistic semiwords like “AmEx,” dissolved in the air like smoke signals emitted from some dismal raft of bad taste adrift on the current of time.

Collazo muffled an improvised chuckle with his napkin. The moral distance between our table and theirs led naturally to the forging of a sort of allied front between Collazo and me. It was then that he took advantage of my distraction, intrepidly captured my hand, and kissed it.

My first steps into adulthood have left me ill-equipped to differentiate between fury and other sources of heat. His mouth was still pressed tight against my hand. Then something fluttered beneath his preputial eyelid: it was passion, rumpled and lethal, capable of blowing the human heart to pieces (cf. Rucci’s Murder by Montoneros, 9-25-73). Collazo was (is) a horrible man, but that doesn’t make him any less attractive to my eyes. The little beast of hatred I carry inside quivers every time it hears his name.

–Mr. Collazo, can I bother you for a second? Would you mind signing this? It’s for my great-aunt, she’s been wanting to read your books since forever, a man said, leaning next to our table.

As he kindly leaned over to accede to my request, stretching out the moment with a question full of feigned attentiveness and a long pull on his cigarette, I got a clean look at his bald head. The sight took me back to Episode Zero. My blonde friend Ilona and I were looking down from our balcony seats at the award ceremony for the most important prize in Spanish literature. On the brightly lit dais far below glowed the bald heads of a bunch of fat emeriti. A fiery applause swept the great hall, advancing like napalm up to the ankles of the writerly tribunes holding court. And the prize goes to . . . A name, and a new wave of napalm flowing from the tireless palms of three thousand overly wined and overly dined attendees; spoons are left suspended in midair as waiters turn to look, and even the restroom attendants peek out of their holes. The Man of the Evening strides athletically up to the podium and smiles—not even the smoke from all this clapping can throw him off his game. He taps the mike with two fingers, brings his most powerful orifice up close to the metal protuberance.

–Good evening. I would like to thank—

–Who is this guy? Ilona asks me in English.

Her pale hand flails in frustration—if only she had binoculars. Her teeth are stained purple, and apart from her violet silk dress, she’s wearing nothing but a ring of Russian amber; a champagne glass trembles in her fingers. She is gorgeous, her gray-green eyes gazing out into the distance as if catching sight of foxes in some scene from Tolstoy (lupa homini lupus). Down below, several men in suits stare up at us, their posture that of hunters. Ilona glides up tight against the balcony’s golden rail, and one knee slides sinuously into view. The air is impregnated with pheromones. I grab her around the waist; it is my duty to inform her that the men below are waiting for us to fall so that they might gather us up. She ceases the mermaid act, sticks out her tongue and laughs. We are utter tourists at a party that has nothing to do with us.

–So who is this guy again?

–Some left-handed writer, (and then almost cooing as we sway softly there at the rail), the kind of guy whose life I wouldn’t mind ruining.

She kept laughing, clicking her teeth against the edge of her champagne glass, not caring a bit. It isn’t that she’d become accustomed to this type of high-flown celebration. (You can always count on one witness and one victim to bring forth a realist prose.) As for Collazo, it wasn’t hard to get him excited about the possibility of adding his books to the departmental syllabi. The prospect of hearing his own name pronounced in professorial tones, and of a row of full-figured students murmuring it, taking their pencils out of their mouths to jot it down, was enough to guarantee his cordial devotion. I wish he’d hold his mouth still; he often grimaces in a way that inadvertently shows his teeth, rabbit-like.

We said our goodbyes at the door of the restaurant. The street was empty. Just as I turned the corner, I realized that he was following me, half-hidden as he snuck along toward me. A beam of dim green light made and unmade the street-side shadows. I walked quietly, tight against the wall—a public zone reserved for women and those marked for death. The faint gleam filtering down through the treetops was now at my back, as if pushing me toward the cone of darkness ahead. And now Collazo sprung his ambush, came tight along my flank to intimidate me, a rapid maneuver that took advantage of the scarcity of light. I kept my eyes on him as I retreated, and my knees cracked against the side of a flower box. He lunged forward. He had me precisely where he wanted me, akimbo there on the sidewalk. His broad silhouette blocked out the light. I couldn’t see anything but the chest hair poking out through his shirt, and above, that mouth, that threat.

–You know, I had a really good time with you tonight.

His eyes traced me up and down as he spoke, his thoughts as clear as any slogan: I’ll calm the little kitten, let her know that I’d like a little something more. I didn’t say a word; my back hunched as if skinned like an animal. My triangle of love had swollen in all three dimensions. Collazo brought his hand softly to my coccyx, pressed down the way one does to get a dog to sit. A whimper escaped me. He looked me in the eyes, kissed me on the forehead, and let me go.

2.1

Individual consciousness boils down to vanity, whose applications form an interface around the body. Because love is a subtitle for something much more specific, more sidereal. Individual consciousness can only relate to others through itself, using the language of vanity. The Theory is unequivocal: it affirms a plot of divine manners lurking under the form of human interest. It unfolds the excess, the intimacy of being in the First Person, while knowing full well that there are Second Persons and Third Persons whose existence with mine, and only through me. The hierarchy of thought imposes a hierarchy on the order of things. The seductive powers of syntax (for those who observe its rules with both pomp and modesty) grow ever stronger by subjugating those gathered around the one who organizes the verbs.

I have plans for this man.

2.1.1

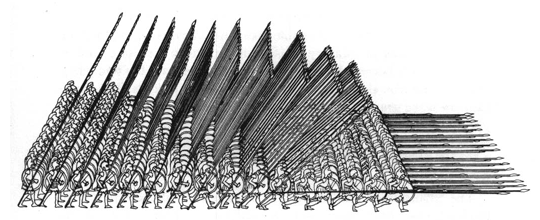

Thinking of Collazo’s old, monkey-like eyes, I stroke Montaigne’s white fur in the hope she will meow in understanding. The little one purrs beneath my hands. With her eyes half-closed, she watches a cockroach walk calmly toward the kitchen, much as one watches the world pass by from aboard a train—impassive, both of us watching. Holding that thought, I glide over to the flamboyant centerpiece of my library (the secret altar I have raised in honor of Hobbes) and catch sight of the question that now rises up through the cat hair: How does one ambush human beings? Back in the pavilions of past time and forward into the encolumned future, syntagma is the term used for a military formation that was invented in the 4th century B.C. and involves two hundred fifty-six warriors:

Other formations included the tetrarchia, made up of sixty-four men, and the taxiarchia, of one hundred twenty-eight; two taxiarchias formed a syntagma, and four syntagmas made up a chiliarchia, which had a total of one thousand twenty-four men. The syntagma prevailed as the most maneuverable of these groups, much like the Roman centurias born of the Marian reforms. When combined with the new weapons and tactics developed by Philip II of Macedon (most notably the sarissa, a long shaft with an iron spearhead at one end and a bronze butt-spike at the other to provide balance), in 338 B.C. they decimated the most prestigious military corps of the ancient world: the Sacred Band of Thebes. This decisive battle, which took place at Chaeronea, led to a crucial change in the very conception of war.

The Thebans utilized the first and only military formation ever inspired by a Platonic dialogue (Plutarch specifically cites the speech of Phaedrus in the Symposium), and had triumphed in what Pausanias considered the most significant conflict pitting Greeks against Greeks, the Battle of Leuctra in 371 B.C. Their elite corps was composed of one hundred and fifty pairs of homosexual warriors. In the flirtatious conversations at the banquet described by Plato, the one at which Phaedrus spoke, it was posited that homosexual warriors were preferable to heterosexual ones, because fighting alongside one’s beloved was an incentive to unfurl one’s courage and other virtues of war.

When the syntagmas of Philip II crushed the brave gay duos of Thebes, the Macedonian style of fighting came to predominate, and the theory of war popularized by the author of The Republic was reduced to ashes, along with the final pyres whereon laid the bodies of the valiant sodomites. Philip had trained his men to form themselves into a uniquely lethal beast; as distinct from earlier combat (and combat theory), where the possibility of winning honor stoked the individual strength and courage of each warrior, the Macedonian model entailed soldiers uniting to form a single body composed of infantry, archery, cavalry and siege weapons. Strictly speaking, they were a single hand of implacable fingers closing on the enemy’s throat. Greek military homophilia had been definitively displaced by a theory of war that sought to revive a lost herd instinct, invoking the figure of the supreme predator with a beast built of thousands of men. The fact that the number of warriors involved in each of Philip’s formations was a power of two no doubt stoked the formal appetite of Johan van Vliet, who saw in the Macedonian syntagmas a milestone in the technical transformation of men into beasts, later perfected by the pact between masses and State known as the republic (where the pact of conquest is the sovereign’s secret).

One of Philip’s tactics was to provoke the enemy all the way to the bitter end.

2.1.2

The purity of the horror involved should not, must not, be assuaged. I must act upon him so as to inspire armies of organized brutality sent vectoring toward me. I muse upon my options: 1. To cause him to throw himself upon me like a wolf, voracious, brutal; 2. To watch him sniff and salivate at my nymphean estuary.

The blow cannot fall in vain. I must swap out his venereal appetite for the blood-stained excess that is at stake. It isn’t enough simply to arouse his desperation, his unconditional surrender to my delicious parts. I have to make him gather every ounce of strength and brutishness, make him reveal to me the purest form of the monster of dominance and destruction, because only then . . . The night does not flee from the wolf of the night: deep in the silvery foliage of the world, it lets the wolf lick its throat, hides the wolf beneath its mantle, and waits. It doesn’t matter if disgust causes my skin to crawl; he will throw himself on top of me, and I will quietly resist. The worse it is—the more strongly, the more violently he takes me—the better. Yes, the worse it is, the better. To distance myself from the horror, I try to focus on the fact that though I must yield in the name of his pleasure, he—we, Augustus—we serve in the name of justice. It isn’t enough to dangle a delicious fruit vert before his eyes, and watch him prepare to gorge. I must produce, indirectly, through him, into me, the bloodbath whose repercussions will be felt in the System of Persons. I must work through him, and yet not: it’s like hypnotizing a lion.

Collazo (like Augustus) has long, stabbing, beautiful hands. They scratch and stretch everything they touch. The thought of them reaching for me makes my hair stand on end. In the words of Pasteur, that genius of evil germs, le hasard ne favorise que les esprits preparés, isn’t that right, Montaigne, ma petite chat?

2.1.3

I’d imagine a train. The blood-curdling nature of a straightaway. The dark spill of a tunnel, the weight of the eyelids, this darkness. The streams of lava, their halting flow; the black earth shuddering beneath the thunder’s throat, stained by this glowing red saliva. My mind would return to me, if only to hide beneath my fist for a few brief moments; a sigh would be heard, and a princess, weak, sallow and feverish, would be seen falling from a fog-laden tower toward the erect lances eager to impale her. The hand of the fog would tighten lasciviously around the curves of her body, licking wildly at her secret rage. I would paint a picture of a train destroying a village, the devastation reaching both forward and backward in time—first out on the plains (floating pollen, tranquility, distant hills) but the noise grows, becomes deafening, implacable, time and space inverted, so loud one must clench one’s eyes shut. Avenues of fire; at the outside doors, asphyxiation. I would paint the lava streaming down across the black earth, lava from the sky that hides wolves and maidens beneath that same stain of fear, an explosion of blood set free—warning bells and clouds would destroy the remains, the echo of insane gunpowder and silent visions, and the rhythm that has set the world atremble would swallow me whole.

2.2

At times I think about the hidden life of certain harmful thoughts. It seems to me an enigma: the second name their presence acquires. I know of a relevant interpretation of the myth of the Cretan labyrinth. Minos is having nightmares in which Asterion becomes disgusted with having to eat those who have come to usurp the throne. The youths who owe their lives to that disgust hide behind walls of fury; they conspire together there in the bowels of torment to create a new race. Power consists in terrorizing fear itself, thinks Minos. These walls exist to multiply my strength; terror is the stone that gives form to and divides our thoughts. Minos can’t stop thinking, his thoughts reflecting the silent struggle that in time turns men into marauders. His wife, Pasiphaë, watches him silently from where she leans against an onyx column. She forsook her taurian loves the moment she saw how others fled at the sight of her little one; her blood has emptied out in the ensuing wait. The myth’s one empirically significant detail is that Pasiphaë likes “brute access,” a phrase derived from the Greek meaning “sex in the rear.”

Minos doesn’t yet know that the conspiracy for which this magnificent labyrinth was created is itself a form of thanks offered by the partisans. Nor that in order to get them to leave their holes and abandon their weasel disguises, he must make use of the ferocity from which his strength derives. He intuits, thanks to this apocryphal sect of thought, that his analysis of that ferocity, that dark figure of suspicion, has at last obliged him to rise up in a pure form of physical domination and destruction. It isn’t enough to have sacrificed a bastard child for the cause. (Asterion, fruit of the queen’s desire, of her lust for both animals and men, has no cause of his own.) The strategies of Minos’s army must be determined by its physical structure. Meanwhile, throughout the labyrinth, from its center out along its tunnels and days, in each nook and corner the walls pray: When the State feels itself obligated to rise up in a pure form of physical domination and destruction, the conditions are ripe for the triumph of the revolution.vi The walls pray, but no one else does, as everyone else is dead.

2.2.1

But:

Can Collazo be considered a Person in the strict sense of the term? I watched him nestle an ashtray in the graying hair on his bare chest, the way men do when they’re accustomed to surroundings organized around them.

I made his gaze climb onto mine.

2.3

He walks alongside me, a heavy shield, or a giant ogre. An ominous moon hangs overhead. We cross Libertador Avenue, head toward the dark woods of Palermo. The wind hisses softly through the foliage, and there are glints of blue in all directions. We can just make out the burbling tumult of a distant underground stream. A bird grazes me as it flits by, but no, night has fallen, these are bats. The trees are prototypes for demons. Our feet sink deeper in with each step; the trees and the signs are links in a single chain. I turn back to look at the avenue where beastly quadrupeds roar in a river of lights; here inside, in the forest, I catch the scent of the snares of bushmen. The drooling apostles who spread revealed truths with dick and dagger much as one tears something out by the roots—the vine that bears the fruit of a curse, or of a slaughterhouse, or of a brothel—I can see them coming. Don Juan Manuel Rosas and his mazorqueros are here, are roaming my body.vii I cannot cover the page with my body, must keep walking, but I can feel the greedy mouths twisting livid deep in the porous black soil, down near the chorus of serpents, their infinite girth, infamous executioners, their fangs, the rites of a horrifying colossus, devourer of hymens and men. We’d felt the roar of this darkness as far back as the edge of Libertador: the gray ghosts from the time of Rosas still stalked the paths along the canals.

I think Collazo sensed my fundamental terror, and spoke as if to calm me. He talked of the corridas of doña Laurencia, of her many appetites, her crepuscular lover. He said that she was kidnapped, taken to the domains of Don Juan Manuel to be abused, forced to submit. Whispering directly into my ear, Collazo repeated the part about “the custom, here in the delta of the Río de la Plata, of the right to rape,” his massive hands leaving marks on my arms.

I looked up at the sky, terrified, and thought of Augustus, of the quote from Prototype for Approaching the Victim where a motive for the existence of armies is proposed: “Only within a plausible psychological theory can human wretchedness, organized to function as antidote, persist.” If you can’t beat them, I thought, you can at least confuse them. I recycled a series of poisonous opinions about a historical novel based on the life and times of Rosas, a book I’d never read, but I knew the plot fairly well. I spoke quickly and vehemently; carrying on that way for quite a while, I basically destroyed the author. Collazo said nothing, perhaps impressed. Later he asked me if that author, too, was listed on syllabi in my department. I laughed, and so did he. Striding along, dodging my solemn pronouncements, Collazo returned to the task, declaring himself fully prepared to defend the theory that one summertide afternoon, Manuelita Rosas must have snuck away with that contrite poet (what was his name?) to listen to a few strains of the national anthem that Vicente López y Planes would one day inherit. Collazo pointed to a plot of sunken ground in the middle of which a rusty iron spike stood erect.

–Right here. He had her by the arm, wasn’t letting go. She was crying uncontrollably, whimpering and wailing like a snot-nosed little girl.

He squatted down to inspect the ground. The dying light fell across the back of his sweatless neck. Up ahead there was a small abandoned fairgrounds thick with weeds, inhabited at present by a sect of spooky-looking merry-go-rounds.

With a quick right hand, I pulled open the two buttons of my blouse; I stood motionless, my legs spread, my boots sunk into the earth. All it would take now is for him to turn to say something, and I, swathed in this tenebrous ardent light, would look into his eyes, ready to unveil the artistry of my pitiless verdict, to perform my duty in the name of all, terribilis ut castrorum acies ordinata.7

A shadow slipped past, was now behind us, and whatever the man said ended emphatically: The money, give me all the money, now.

Collazo was still hunched down. Maybe they hadn’t seen him. Maybe he was planning the perfect strategy for taking the assailants down with two or three blows. He would rip the rusty spike out of the earth, throw himself at them like a master samurai, spit that cyanide-laden Montonero tooth with the precision of a ninja’s dart. He gathered himself up, his face deadly serious, and took a step forward. The violet branches of the trees stretched out overhead. He shot me a wink, looked one-eyed in the dark.

–Leave this to me, he whispered, rooting around in his front pocket. Boys, here you go, ten pesos. He pawed again through the contents snug up against his balls. Hey, look, that’s twenty altogether. All yours.

–Son of a bitch, give me everything you’ve got, this isn’t some scene from Tumberos.

One of them brandished a knife. With a brief sigh, I opened my little backpack and brought out the French edition (1934) of Trotsky’s History of the Russian Revolution, Naufragios by Álvar Núñez Cabeza de Vaca, De Civitate Dei by St. Augustine (the Migne edition, bilingual, with the disastrous Spanish translation), Storie italiane di violenza e terrorismo (a fascinating analysis of Potere Operaio, cradle of the Red Brigades), and a small anthology of Catholic poems (very funny) by Péguy. Collazo and the two socio-political outcasts watched as the books piled up. It was then that I realized, thanks to the roving eyes of the muggers, that the buttons of my blouse were still open. Oh my god, I thought. I didn’t want to make any false moves, so I left them open.

One of the two correlatives of capitalist perversity took a deep huff from the plastic bag in his hand, and stared at me. Loki was thin, light on his feet, with coarse skin stretched tight around his proletarian bones. He now showed us the angriest facets of his earthly I.

–Give me your cell phone, your wallet, your credit cards—both of you, right now.

Cacha, the other inheritor of social injustice, began poking at the pants pockets of the ex-guerrilla, who raised his arms. Leaning sideways against a tree trunk, Collazo furled his tiger’s brow and murmured:

–Nice and calm, I’m unarmed.

–Hey douchebag, who said anything about you being armed. Let’s see if you’ve at least got some cash.

He opened Collazo’s wallet, started flipping through the credit cards.

–Visa, Mastercard, American Express, cool. Nothing gets canceled until tomorrow night, you feel me?

I lit a cigarette, and took a step forward.

–Loki, Cacha, wait a second. Let me say something to you guys. This person here in front of you, whom you’ve disrespected, he basically dedicated his youth and his life to a cause that included saving indigent slum-dwellers like yourselves, and everyone else who wasn’t born where they might have liked, who’s been treated like shit by Fate. Your families, your loved ones. The socialist fatherland wasn’t merely a dream. There were years and years of underground struggle, of getting insulted in the streets, of books that no one wanted to publish, of taking your head in your hands at the Bar La Paz and shouting, “No! Enough! This is not how things should be!”

The three men stood stiffly for a long moment. I kept talking; I don’t even want to remember what I said. Loki walked over to where Cacha was standing beside the ex-militant.

–So you’re a politician? he said to Collazo. Are you? Are you?

Collazo tried to duck but Loki’s hand caught him full in the face.

–Answer me! No? Nothing to say? You motherfucking thief!

Now he started punching Collazo, and in my stubbornness I shouted, No, no! He’s not a politician at all! He’s just a leftist intellectual!

Cacha and Loki looked at me, looked at Collazo, and started hitting him even harder. There were no more arguments worth making; history had ruined all hope of discussion. My tone had been appropriate, and even my sentimental choice of certain terms, but what perverse idiosyncrasy—so harmful! so fruitless!—had strained my common sense to the point that I tried to make Collazo seem heroic? Are good intentions enough to make someone a hero? And what must his good intentions have been, exactly, if they were never to become anything more, or if in the process of transforming them into actions he’d done some horrible things, and if the very ineffectiveness of the transformation demonstrated the incoherence and criminality of this hardly ideal situation? What’s more: what absurd aspiration had led me to intrude upon the natural right of a poor man to mug me in the forest? Dignity? What dignity could there be in this old bag of ideologemes lying in the grass, bleeding from the nose? Analyzing the situation now from a metatheoretical standpoint, how could I have hoped to convince them with the pathetic irony implicit in a situation where one monkey holding the knife of possibility faces off against other monkeys holding knives of . . . actual knives? I sighed. The expected recipients of revolutionary benevolence kept kicking Collazo there where he lay. I had committed the sin of atavistic condescension. I was on the verge of losing my earnestness and starting to cry.

–Enough, enough! Please leave him alone!

Loki shot a sign to Cacha, his twin in structural poverty.

–Tie the fat girl up and make her quit yelling.

Cacha advanced on the fat?!?!?! girl with a roll of sisal twine. I still had my lit cigarette, and buried the burning end indignantly in his arm. He smacked me in the face; then, with amazing precision, he tripped over the iron spike, his foot striking it so hard it made the earth shake. He hunched over, mute with pain. Then he limped to his partner, who was punching the prone Collazo below the poverty line.

–Loki, come on, we’re done here, let’s go.

–You got everything?

–Yes, come on, time to bail.

These two, long pillaged by the system, bundled up their booty and took off toward the dark circular drive too small to be called an avenue. I ran to the wounded-in-action.

–Did they hurt you?

With a certain agility, Collazo rolled onto his side in the grass.

–A little, yeah. But I played a lot of rugby when I was young—my stomach is still hard as steel.

–Really? Can I see?

–Sure.

He opened his shirt. There were a couple of red marks, a few bruises; the stingy light made it hard to see much more. My hand drew close to the grainy skin. Scars, offered like a harem of thirsty mouths, the toothy topography of ancestral sharks, the palpitating cartography at the mouth of the slough. The red, the black—the fur. I closed my eyes, being not quite ghoulish enough to carry on.

–I’m really sorry about your American Express card, I said as I helped him up.

–Don’t worry, he answered, brushing the dirt from his clothes.

–But they took the books!

–Maybe they’ll help raise awareness . . .

We laugh a little. Then we walk for a while without saying a word.

–Should we follow them?

I could hear the disappointment in my voice.

–No, let it go. They took some money, they beat me up a bit, but nothing serious. Look!

And there was my poor old useless history of the Russian revolution, abandoned in a pile of dead leaves. I brushed away the dirt with my hands, scraped off the edges, paged through quickly as I hefted the book to make sure its spine wasn’t broken. I held it up high and inspected the cover, searching for signs of human meddling. Then I tucked the volume deep into my backpack.

–Of course they kept the Péguy, I murmured bitterly.

–At least the police didn’t come. They’d have confiscated the book, and nobody’d ever have seen those poor thieves again.

–Did you know that police officers and thieves tend to come from the same social class, and have exactly the same disdain for anyone who got the education they never received?

I would have kept talking, but I was exhausted.

–Are you okay?

–I don’t know.

I kicked at a loose leaf.

–They called me fat.

–I thought they said slut.

–Um . . . Are you sure?

–You like that better?

–Well . . .

For a second I pretended I had something caught in my throat.

–At least it’s good to know that their nutritional shortcomings haven’t damaged their vision too badly.

The son of a bitch said nothing. Nothing! He just let my sentence hang there in the air until it finally floated away.

In the ice cream parlor on the far side of Libertador, the middle-aged guys and the young girls were like separate voting blocs in Congress, not obviously at odds but definitely from different camps. We explained to the guy behind the counter what had happened, and he consoled us with some free almonds. I ordered Nero chocolate with the works; Collazo had a mango and strawberry.

I looked at his forehead. His bald pate reflected the street on all sides. I sighed. From then on, every time he saw me, the word “fat” would be hanging from my neck like a cowbell, right there in medias res.

But just now Collazo didn’t even see me. I wasn’t there at all, or it was time to go.

–Should I call you a taxi?

–No, that’s all right, I’d rather walk.

I headed out along República de la India, impregnating myself with the nauseating odor of the zoo, the dogs’ excretions, and my thoughts.

2.3.1

I simply can’t understand how it’s possible that they didn’t even try to throw me down in the mud with their muddy hands and decivilize me from behind. And me, on my knees in the mud, comme un chien.

Now that dusk has fallen, (now that Yorick of Minerva emerges to splash about in the swamps of the world,) I withdraw into my chambers. It’s been a long afternoon of not wanting to think about things. I opened a soft drink and looked at Yorick, swimming calmly around in his bowl. Lucky fish, who doesn’t have to struggle against scale-lined reality or its doppelgänger minions, these thoughts. “We will triumph!” I muttered. “They’ll see!” The kitten Montaigne tensed up and ran from my sight; predictably, she had omitted defecating in the litter box.

Poor Augustus, he doesn’t fully realize how serious the problem is. He’s very busy walking up and down the labyrinthine hallways of the Department of Philosophy and Letters, distanced from the world of concrete facts, as if nothing was going on with that woman. Little by little, his power fades. Up on the fourth floor where the research institute is located, there is a hive of tiny and deviously well-hidden offices and classrooms. Attacks by ineffable assailants are far more common than necessary (although perhaps the number of such attacks is coincidental, and “attack” and “necessity” harbor some mysterious semantic bond). There went the two of them, followed by B.M., a.k.a. Fat E.G.

I watched them, my earphones on, manifesting, through my vestal stillness, the deadly implications of the spatial syntax that had been perpetrated; I stood like the I that rises up at the beginning of a sentence, on the verge of throwing itself upon a verb and an object, of ruling over them, possessing them, or remaining tacit, not quite revealing itself—and yet in control of events. As a sort of reply to the tenor and quake of that scene, here is the song I was listening to at the moment—here we go with the guitars and the lyrics:

Se te olvida

que me quieres a pesar de lo que dices,

pues llevamos en el alma cicatrices

imposibles de borrar.

Se te olvida: que yo puedo hacerte mal

– si me decido –,

pues tu amor lo tengo muy “comprometido”,

pero a fuerza no será.8

Y hoy resulta que no soy de la estatura de tu vida,

y al dejarme casi casi se te olvida

que hay un pacto

entre los dos. viii

3.

The sunlight turns the brownish waters green, blazes out from behind the silhouette of Collazo, who stands upright in the boat. He’s wearing a wide-brimmed hat, a white shirt open at the chest, black trousers. Willow branches caress the surface of the water; the vines open before him like an endless succession of curtains. He leans against the rubber-lined edge, tests the hand-forged blade of his knife on the swollen lobes of water hyacinth that float alongside. At times the light goes dark, and his face, his eyes are hidden in shadow; his dark mustache glows sweatily above his mouth. We have a dog, a Winchester, and the knife that Collazo now tucks into his belt.

The boat glides slowly across the water. The roots of the trees are submerged; the weighted air molds itself to the gold and black forms that enclose it. The bromeliads twist in on themselves, swaying softly. The riverbank shows the rough lay of the land, the broken line of treetops. Branches lean out over the river, observe the water’s flow, see it quiver beneath them. Black birds circle in the sky. The branches trace endless paths on the mirror between us and the mud and rot that lie beneath.

I have the feeling that Collazo’s enormous hand is about to grab hold of my thigh. I say nothing. I lower my gaze. Vertigo criss-crossed by chasms, the air ceases to move, the ferocious sun covers everything in white. I fear only that my obsession has been revealed, that the monsters have made me translucent, can be seen through the cracks.

From time to time the water goes totally black. The sun disappears, and we hear a quiet hiss, as if something were catching fire somewhere out of sight.

Collazo stands at the edge; my eyes rest at the height of his belt, or a bit lower. He looks down, and there I am. He looks at me and grabs at himself, his hand tracking across the zone. Beneath the cloth waits the red spear, the mute inhabitant. She (I) pushes her hair back from her face, turns her head to look toward the trees. Collazo slides his hand slowly along his critical apparatus, and shifts it to one side of his fly.

–You see? This is what they mean by “packing.” Everything off to the side.

She (I) looks closely. The mountainous chain hangs well down his thigh. She waits for a few seconds, takes a deep breath, looks him in the eyes.

–The left side, she says.

Collazo smiles. Of course, from her perspective it’s actually off to the right.

–And that tells you quite a bit about a man, doesn’t it.

Collazo is behaving magnificently.

–Do you always pack to the same side?

–Me, always.

Collazo rubs his hands briskly up and down his body, shooing away the stubborn mosquitoes that have come to appropriate his blood. We pass below some branches and his face falls into shadow.

The heat grows. Our clothes stick to our bodies, and the air is dense, filled with bright flecks. Collazo’s white shirt is open down to his solar plexus, the valley through which knives enter; the grayish fleece on his chest shines with sweat. Collazo slaps his arm for the Nth time, and looks at me.

Any moment now. Any moment and he throws himself on top of me. His huge horrific hand takes me by the back of the neck—I feel an inverse wind, a momentary tornado of heat and teeth—I release my breath, squeeze my eyes shut, and whisper to throw him off track:

–Have you ever hunted for white-eared opossum?

The light shines on Collazo as he lets go of my neck and grabs a handful of cartridges.

–They’re an appalling animal, he says. Whenever they feel trapped by a predator, they spray a defensive secretion out of their genitals, this revolting yellow liquid. And if the threat is inescapable, they lapse into a coma and go completely still.

As he speaks, he puts the cartridges in the shotgun. The river gathers speed—I can feel the current humming in the tips of my toes. My body, a vessel full of blood on the verge of spilling over. I run my tongue across my lips.

Collazo looks at me.

–They love to play dead, he says. To play dumb.

He bites down on his cigarette, and comes down off the edge. Then he hefts the shotgun, presses it against his temple. I treasure the moment intensely. A few sparrows twist and turn against the sky, and Collazo aims, tracks them in his sights, breathes, the seedpods around him yellowed by the heat. At the other end of the boat, the dog chews on Collazo’s overshirt. The dog came with the boat, I don’t know its name. Collazo lowers the shotgun and looks at me, his brow suddenly furled. Everything goes dark.

(Silence. Collazo, fear and trembling.)

As we come out of the tunnel, the light returns like an exclamation. There are countless golden flecks suspended before our eyes. His long calloused fingers spread suddenly against the foreshortened mirror of black water, move lightly across the surface of the swamp amidst the chirring of crickets and the creak of wood as it begins to break.

Then he brings his hand to my ear. I jump, startled.

–Relax, he says, smiling, wetting my ear with water. It’s just a little shit.

I let loose a bored sigh, and take my comic book back up—a Nippur de Lagash. The Man of Lagash has fallen in love again, this time with Karien the Red, queen of the Amazons, with whom, several issues later, he will engender his three-eyed daughter Oona. In the issue I have here, the Wanderer meets Hattusil, the Hittite hunchback considered to be the greatest warrior on the planet, who will become his best friend.

I watch Collazo out of the corner of my eye. He doesn’t notice. My mind wanders silently through the swamp, shimmying along as it awaits the sudden appearance of a supernatural anaconda.

Then Collazo coughed. He gestured at an opening filled with scrub. The grayish bank was covered with hills of garbage rising to the sky. He said that at 6:30 one evening, just as summer was beginning, his organization had launched an assault on the Itatí, a yacht that belonged to the Commander-in-Chief of the Navy. An underwater mine of ammonium nitrate had been laid by a team of divers formed in Cuba in the late 1960s—the same team that had blown up Villar’s yacht in some other inlet here on the Tigre Delta. They knew that the admiral would not be aboard—armed Peronist left-wing loyalists by profession, what they actually sought was an unwitting ally in the Armed Forces. They’d shot up a police helicopter to facilitate their getaway; a few days later, they went up against the last of their targets on the Peronist right wing, Alberto Campos, political and military enemy. Just beyond is the Reconquista shipyard; they’d occupied the entire facility, and posted a sign to serve as warning and prelude, Danger: Dynamite. Nearly a thousand vessels were blown to bits, and the oil from their motors covered the water with black, and the fire floated on the water. It burned until morning, and the attackers flowed south across Buenos Aires; the combat platoons blocked Libertador Avenue and took over the public transportation system. The din was deafening as the magnificent youths advanced along the city’s main arteries, slamming their vehicles into banks, smashing windows and storefronts. More than fifty cars were set on fire, as well as businesses, concession stands and police vehicles. This was followed by a wave of hand-thrown bombs, and banners filling the air, and bursts of gunfire to which any number of meanings would later be attributed. All of this was in 1975—two years before I was born—and timed to coincide with the anniversary of Evita’s death.