3

I built the temple of Mars Ultor on private grounds and the forum of Augustus from war-spoils. Three times I gave shows of gladiators under my name and five times under the name of my sons and grandsons; in these shows about 10,000 men fought. I celebrated the Games under my name four times, and twenty-three times in place of other magistrates. Twenty-six times, under my name or that of my sons and grandsons, I gave the people hunts of African beasts in the circus, under the open sky, or in the amphitheater; in them about 3,500 beasts were killed.

The Deeds of the Divine Augustus abounds in passages where the words bestia and venationes are continuously intermixed to refer to Roman Games involving predators. In Suetonius we find damnare aliquem ad bestias, condemned to be torn apart by wild beasts. Bestia (in its first Latin declension, typically feminine) means of obscure origin, but its lexical importance to the Games led to the addition of human suffixes. Bestius and bestiarius, in Seneca and Tertullian, are those condemned to be devoured by beasts; Cicero’s usage refers to the gladiator who fights against them. Augustine of Hippo uses the adverb bestialiter—as would a beast, in a beastly manner—and keeps bestiarius separate to refer to the attributes of the beasts themselves; bestius is that which is ferocious, beast-like.

On the side of the beasts, one finds the lion of Biledulgerid, the leopard of Hindustan, the desert antelope, the British stag, and the Arctic reindeer; the albino bull of Northumberland, the unicorn of Tibet, the hippopotamus of the African coast and the elephant of Siam; ibex from Angora, the wild ass, dwarf giraffes, ostriches and zebras. “Their savage voices ascended in tumultuous uproar to the chambers of the capitol,” (writes De Quincey) before the majesty of Jupiter Tonans—Caesar Augustus. On the side of the beasts, men crouched and ready for combat.

From a grammatical point of view, there is nothing keeping a man from converting himself into a beast; bestius, the ferocious beast-like creature who flaunts his beauty and deformity on the vast blood-fields of Rome, relies on his syntactic position to tell him which side he is killing for, which beast to strike. The name of the victim coincides with that of the aggressor—in the arena every beast is alike. It is thus only the beast’s place within the sentence that determines its ontological nature, indicating what it is that one is. Beast can refer either to the one representing the State’s power of Reason (in which case the spectacle consists of ripping apart some enemy of Rome—a Christian, a barbarian, et cetera), or to the one who is to be chased down by the sovereign human (in which case the human victor is celebrated by the multitudes, and what he annihilates is merely prey supplied to him by the Games).

The beauty of the beast—she of obscure origins—is displayed diachronically. In Latin, bello, -avi, -atum is the verbal form meaning to wage and carry on war, to make war. The dictionary follows these bellicose forms of bello with the adverbial forms of belle, used to indicate that something has been prepared deliciously well (Attica belle se habet); exquisitely, with good taste and elegance, praediola belle edificata—small possessions built with taste (Cicero). We proceed past “Sweetly, softly, deliciously, delicately; in a kind, funny, friendly manner” to Bellerophon, grandson of Sisyphus, and from there to bellicum: in Cicero and Justinian, the word refers to a signal—a call to arms, to battle stations—which, in the field of rhetorical operations, is the moderately disdainful slap in the face that Cicero delivers with bellicum: “to strike a haughty tone.” But bellua (of obscure origins) is the ferocious beast, the savage animal; fera et immanis bellua—cruel and ferocious beast. A monster, a monstrous thing; in Livy (a contemporary of Caesar Augustus), we find Volo ego illi bellua ostendere, meaning “I want to show this savage, this great beast, what goodness is” (note bellua at the center of the threat). Bellipotens (the God of War in Virgil) rests on bellitudo: loveliness, grace, beauty.

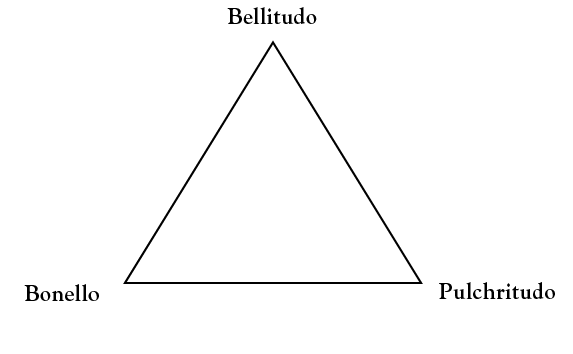

These are the roots that beauty and war have in common. This is the philological triangle of charm and brutality on the verge of blowing apart:

Each of the three vertices, the three synonyms for beauty, is a vector projected through time. Bonello mutates toward the idea of bueno, the good, conserving its roots in Spanish; it is the aspect of beauty that is carved out by the moral sense. Pulchritudo is the beauty that adorns the harmonic ratio of the precise, the ordered, the hygienic; the pulchrum posits the beautiful in opposition to the repugnant. Pulchrum and bonello are the facets of a Platonic diamond wherein what shines is Being itself. Bellitudo alone of the three synonyms has not been domesticated by Platonic ideals, by the imposition of pure being, the astral house of the just, the good. Bellitudo is beauty inhabited by war, much as beauty inhabits war. Bellitudo encloses a tumultuous seed: the beauty of the bellum, wherein roars the deadly, predatory nature of the bestia, the bellua, synthesis of sovereign Eros and Mars the Seducer.

The Deeds of the Divine Augustus contains several important illustrations, among them a reproduction of the central frieze of the temple of Mars the Avenger. As is all too well known—and there is nothing the least bit personal in this comment—in that frieze, Vulcan stands outside the temple calling desperately for Venus, unable to do anything about the fact that she has already left with Mars, her lover, at whom she smiles sweetly, enjoying her act of betrayal.

All of which reminds me of a certain accursed afternoon in the labyrinth that is the top floor of the Philosophy and Letters building. Augustus was walking hurriedly, poking around in one of his shirt pockets, the one where he always keeps his cigarettes and that pelican-blue Mont Blanc they gave him when he won the Ezequiel Martínez Estrada National Essay Prize. He was carrying folders, books, loose papers . . . and perhaps a manila envelope, one enclosing a dazzling message signed by Rosa Ostreech?10

Reacting quickly, I hid. It wasn’t that I was afraid to see him or speak to him, but that I am wholly and terrifiedly conscious of the fact that words spoken aloud (the mysterious syntax nested within them) determine and actualize transcendentally the events in which they are embedded. My derailed heart beat wildly; when I saw that he was turning in my direction, I lost all control of my muscles and waved hello, the fat tome in my hand thrashing back and forth overhead. For an instant, it seemed that he’d noticed the eagle of my gaze alighting beside him, and was turning away. But I calmly watched as the scene played out—and in the end, the dove of peace devoured the raptor.

In his attempt to avoid a frontal encounter with an Ethics adjunct who was dragging her existence through the vicinity, he failed to notice that the dark heavy object in my hand was nothing less than a volume of Byron. (In the previous class, Augustus had devoted a rather inopportune interlude to a number of “encrypted” sonnets that some dangerous madwoman had offered up to the poet, who wanted nothing to do with her, hated her and did everything possible to avoid her letters, propositions, and company. At one point it got so bad that he’d had to chase her away in public, in the middle of the town square.) I’d been looking for the passage Augustus had quoted, but still hadn’t found it—in the annals of English philology, the title Complete Works is invariably either fraudulent or blasphemous. Of course, the Ethics adjunct couldn’t infer anything from any of this; she deftly intercepted my dear theoretician, and poor ashen Augustus prolonged the lively encounter as if it were some Ciceronian sententia.

That would have been my final assessment of the episode, but then I detected the equine shadow of the odious one at the end of the hallway; her hair was tied up in a little bun, and her eyes were fixed on me. When he managed to free himself from the Ethics adjunct, Augustus headed directly for that woman, and she whispered something to him, whispered it almost directly into his ear. Both of them turned to look at me. Their lips continued to move.

I walked back to my house, kicking at piles of leaves and stepping in dog shit. Barely in through the door of my pied-à-terre, I realized that I’d forgotten to feed little Montaigne, who mewed resentfully as I crossed through the rarified darkness. As for Yorick, he’d managed to survive Montaigne’s kittenish hunger, and was swimming peacefully in his bowl. I found the whole scene very moving. So many days without them. As if in slow motion, Yorick floated up to eat the food that drifted down through the rising bubbles. To please him, I brought a mirror up to the side of the bowl. He immediately went on high alert; he intended to fight this intruder, this other fish, this stranger swimming in front of him. I let him play like this for a time. When he began to tire, I covered the mirror, and instantly his feathery blood-red dorsal fin began to swell: the other had withdrawn, and Yorick had triumphed. The individual consciousness is a function of one’s vanity, whose rank determines the body’s spectra of possibilities. The truth of this axiom is verifiable even in populations most often ignored in psycho-political studies, including cold-blooded animals, whose miniature brains hearken back to pre-mammalian evolutionary phases. Oh the things I’ve never told you, Augustus, the things I’ve kept to myself.

Watching my pets at play, I get a sense of how the Voice who organizes the tale returns to float above her prey like some logical, succinct she-wolf. In short, Augustus, I just don’t know. It’s hard for me to keep going, following your signals. I let my thoughts travel through the dark until I can no longer hear them. When a state of amorous emergency is declared, the sovereign takes control of others’ lives. He looks out over the long line of heads bowed in his honor, the long white strip that is the napes of the necks of those who revere him, and he rises, looks again at those necks: inside runs that which is surrendered in silence. He contemplates, he deciphers, he rises. But if he were up in the heavens, what would he see?

A canopy of black branches hanging over the pastures. Open spaces like stains; the black branches interlocked, a coven of spiders. Oily, dark green undergrowth. Black birds spiraling. Glittering fog, dragging itself along the grass. Totora reeds. A small boat at anchor, a barking dog.

Your hostage is down there. Motionless, somewhere.

10 This is the name behind which your faithful narrator hides.