| 5 | SAFED |

Thursday, August 29, 1929

In which we will head northward to this Galilean town and see how Jews and Arabs lived there side by side for many years, and what the Arabs and the Jews say about those days. We will, once again, try to understand how friends turned into enemies, what got etched onto the hearts of the children of 1929, and how memory of that year influenced the fighters of 1948.

In Safed, like Hebron and like Motza, Arabs attacked their Jewish neighbors, Jews whom they had often welcomed into their own homes. It happened five days after the massacre in Hebron, when the country had calmed almost completely. On Thursday afternoon, in full view of several Arab policemen and sparse British security forces, Arab bands stormed into Safed’s Jewish quarter, descending from neighborhoods higher up on the slope on which the city stood and ascending from the Amud River channel below. For nearly an hour they went from house to house with knives and axes, killing and maiming, dousing the houses with combustibles and setting them afire. Thirteen Jews were killed in Safed during the 1929 disturbances, most of them in this brief violent episode. Another three Jews were burned to death in nearby Ein Zeitim, and two others were shot dead on the roads into the town. The flames from the homes of the Jews were spread by the wind toward the Arab neighborhoods, one of the reasons the attack stopped so soon.

Mazal Cohen was one of the dead. A eulogy for her by her brother (Menachem Raphael) appeared in Davar. More than a painful tribute to a sister brutally murdered, it is a valedictory for Jewish-Arab coexistence in the Galilean mountains, in the city of the Jewish mystics and pious Muslims, merchants and peddlers, and idlers and laborers of both faiths:

For a quarter of a century I have spoken their language, perused their books, learned their way of life, observed their ways and manners, yet I did not know them. . . . Who injected into your inner beings this twisted spirit, to stride with drawn swords at the head of a bloodthirsty throng and to lend a hand to murdering innocent people who lived with you securely for generations, who just yesterday were your companions and friends. . . .

You always said that you considered native-born Jews to be your brothers, that you would love them, that you would respect them, because you share a single language and way of talking with them, and that you bore a grudge only against those who came anew to grasp the shovel and plow, who with the sweat of their brows turned the wastelands into blooming gardens, against those who lit up the darkness and who did not discriminate between their brothers and yours, giving succor and healing your maladies as well in their medical institutions, against those who brought to this country the culturally and humanly good and beautiful, the light and magnificence to which your eyes too opened, wakening you from your long slumber. . . .

And how is it that you, the murderers of Safed, beset like beasts of prey solely those inhabitants of the city who have been integrated there for generations, turning their homes to heaps of ruins, mercilessly killing women and the old and the weak, who never did you any harm, taking the lives of people whose mother tongue is your language, and whose way of life is yours, different from you only in religion. . . .

I have lived among you for a quarter of a century, I have been your guest, I have attended to your confidences and thoughts, and I did not know you. (M. R. Cohen, “I Didn’t Know Them,” Davar, October 13, 1929)

The Motif Returns

The speaker’s hurt over losing his sister was enormous, and to it was added his pain at how his neighbors and friends had turned on him. How could they have abetted such vicious murders? M. R. Cohen reaches a precise and understandable conclusion: he had not truly known his neighbors, nor had he understood that the gap between them was so great. But what gap did he mean? In his view, it was a moral disparity. The Arabs had revealed their true faces—they were despicable and treacherous murderers. But the eulogy suggests another source of the difference between Jews and Arabs, a political one. Each side experienced differently the change that Palestine underwent during the first decade of British rule. According to Cohen, Zionism brought culture and progress to the inhabitants of the land. The Arabs saw this same process as one of conquest and exploitation. For them, the transformation of the wastelands into blooming gardens meant Jewish confiscation of their land. The idea of equality that the Jewish pioneers brought with them was a bad joke for the Arabs—did not the Jews plan to establish a Jewish state and deny the Arabs their national rights?

Without intending it, Cohen highlighted the core of the separation of the Arab Jews from the other Arabs, the beginning of which we considered in chapter 1 from the point of view of Mordechai Elkayam of Jaffa. At that time, during the Second Aliyah, members of the established Jewish population found themselves divided between loyalty to their fellow Jews and to their own tradition and culture, which had much in common with the local Muslims and Christians. But thanks to the influx of pioneering Zionists during the early years of the British Mandate, the Yishuv grew in number and strength. The old-timers were proud of this. More accurately, they felt uncomfortable with the alien values that the pioneers brought with them and disliked the condescension and alienation with which the European immigrants treated the native Jews. They were frustrated by the fact that the foreigners were appropriating the resources of the country’s Jewish community. Yet, despite all this, they saw much that was positive in the newcomers. They were brethren who had come to redeem the soil of the homeland, striving toward the promised redemption, coreligionists bearing the banners of progress and modernity. Most importantly, they were fellow Jews whose arrival would help turn the Jews into a majority in their ancestral land. The feelings of the established Jews about the pioneers were thus completely different from the feelings of Muslim and Christian Arabs, who viewed the pioneers as arrogant foreign invaders whose goal was to eject Palestinian Arabs from their own country. In the context of the times, at the climax of the consolidation of national identities, any indication of identification with Zionism by the longtime Jewish inhabitants of Palestine was understood by their Muslim and Christian neighbors as a declaration of war against Arab nationalism, as well as against the rights of the Palestinian Arabs to their land. Hence it made no difference that these Jews had long been part of the Arab cultural sphere. For the Palestinian Arabs, then, the Jews of North Africa and the East became one and the same as the Jews from Eastern Europe, for better and for worse. That was the situation throughout the country, Safed included.

1921: The Jews of Safed Sign Off on Zionism

The Jews of Safed, or at least the community’s leaders, had made their political choice in the summer of 1921. The leaders of the Palestinian national movement had traveled to London for a series of meetings with the British regime, their goal being to bring about the revocation of the Balfour Declaration. While the Arab delegation was in London, it declared that it represented all the longtime inhabitants of Palestine: Muslims, Christians, and Jews. The Zionist leadership was alarmed and sent emissaries to collect pledges of support from the leaders of the old Sephardi communities in Hebron, Jerusalem, Safed, Tiberias, Jaffa, and Haifa. The petitions stated that these Jews viewed the Balfour Declaration as “the beginning of the fulfillment of a generations-old prophecy,” in the words chosen by the Jews of Jaffa (CZA Z4/41245). A similar statement came from Safed: “The Sephardi community of Safed firmly protests the reports disseminated by the Arab delegation, according to which the Sephardi Jews in the Land of Israel are on its side, and hereby declares openly that it is in total agreement with the rest of the Jews of the Land of Israel in their demand to carry out the promises made to create a Jewish national home in the Land of Israel. There is no difference between its opinions on this subject and those of the rest of the Jews in the Land of Israel and the Exile” (CZA Z4/41245).

One of the signatories was Safed’s Chief Rabbi Yishma‘el Hakohen, whom we will encounter below. In the meantime, the point is to see, once again, that intra-Jewish differences were dwarfed by the historic opportunity all Jews saw to provide a firm political foundation for themselves in the Holy Land, under British protection.

In the Background: More Distant History

Even if, with good reason, we do not accept the common Muslim claim that Jewish life under Islamic rule was one uninterrupted golden age, Safed was a classic example of how a creative and vibrant Jewish community could develop under Muslim rule. At the encouragement of Sultan Bayezed II, Jewish exiles from Spain settled throughout the Ottoman Empire. In the sixteenth century many Jews settled in Safed, both because the wool industry there offered them a livelihood and because of the city’s proximity to the tombs of many Tana’im, the rabbis of the Mishnaic period, among them Rabbi Shimon Bar Yohai. Some of the period’s greatest Jewish legal scholars (such as Rabbi Yosef Karo, author of the Shulkhan Arukh), liturgical poets (among them Rabbi Shlomo Alkabetz, author of Lekha Dodi), and mystics (most notably Rabbi Yitzhak Luria, known as the Ari; Rabbi Moshe Cordovero; and Rabbi Hayyim Vital) lived and worked there. No better proof of the city’s Jewish cultural and religious blossoming during the early Ottoman period is needed.

This celebrated period demonstrates that the Muslim rulers of the time did not see Jewish settlement in Palestine in a negative light, and that contemporary Islamic law and practice did not deny Jews the right to purchase land and settle there. In fact, opposition to Jewish settlement in Palestine is largely a modern Muslim phenomenon, the product of the age of colonialism and nationalism. Amnon Raz-Krakotzkin suggested in a seminar at the Van Leer Institute in Jerusalem in 2011 that when the Spanish exiles settled in the Galilee and connected with the tombs of the Sages of the Mishnah, they fashioned a model of Jewish life in Palestine with roots in the period of the Mishnah and Talmud—that is, an era in which the Jewish people lacked political sovereignty. This differed from the Zionist approach of three hundred years later, which saw itself as a direct heir of the Jewish sovereignty of the biblical era. As such, the Jewish settlement in Safed was seen as unthreatening and even desirable, while Zionist settlement was perceived as a menace. Raz-Krakotzkin’s claim is debatable—after all, Jewish religious and redemptive activity of the type practiced by Safed’s rabbis and mystics also challenges Islam. Belief in Jewish messianic redemption implies that Islam is not the true faith. But religious belief need not focus on rivalry with other creeds. For many years a different conception was prominent, one that focused on what Judaism and Islam shared. In and around Safed this was expressed in a variety of ways. Here is a passage written by a native of Safed, Rabbi Shlomo Meinstral, taken from a letter he wrote at the beginning of the seventeenth century: “They [the non-Jews in Palestine] treat with great sanctity the tombs of the holy Tana’im and the synagogues and they light candles on the tombs of the saints and vow [gifts of] oil to synagogues. In the village of Ein Zeitim and Meron there are, as a result of our abundant sins, ruined and empty synagogues, and within them innumerable Torah scrolls in their arks, the gentiles treat them with great respect, and hold the keys and honor them and light candles before the arks, and no one may approach and touch the Torah scrolls.” Natan Shor, who includes this quote in Toldot Tzfat (A history of Safed; 1983, 94), warns that Meinstral tended to exaggerate. Shor also attributes the good treatment of the Jews to the firm hand of the authorities, which induced “the Muslim population to act with such a measure of tolerance, despite its natural inclinations” (ibid., 95).

The phrase “natural inclinations” used by Shor is not a product of in-depth analysis or precise historical reportage, if for no other reason than the fact that enmity between Muslims and Jews is not anything like a natural law. Interconfessional violence, or antagonism between any different populations, is generally a result of religious or political power struggles. Its manifestation and intensity are affected by changes in the balance of power between different groups. Islamic moderates like to quote a verse from the Qur‘an: “People, We created you all from a single man and a single woman, and made you into races and tribes so that you should recognize one another” (al-Hujurat, The Private Rooms 49:13). In other words, the existence of different nations, as well as different genders, is a foundation of human life.

The violence of 1929 does not negate the coexistence that prevailed in Safed during the sixteenth century, but perhaps the later period casts new light on the earlier one. Another book on Safed, by Yasar al-‘Askari, a volume in the series al-Mudun al-Falistiniyya (The cities of Palestine) published by the Cultural Department of the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO), addresses the changes that took place under the Mandate.

Al-‘Askari’s Qussat Madina: Safad (Story of a City: Safed, 1989) adopts the common Islamic view of Muslim rule as benevolent. The author, himself a refugee from Safed, writes at length about relations between Jews and Arabs in the town. He describes the Sephardi and Ashkenazi communities, explains that the Jews were part of the social fabric, notes that they spoke Arabic, and says that those who frequented Arab villages in the area donned the Palestinian headdress, the kufiyyeh. He tells how Jews and Arabs frequented the same cafés and waxes nostalgic about the common Muslim custom (which many Jews from Islamic lands also fondly recall) of bringing cakes, pita bread, and sweets to the Jews on the night when the Pesach holiday ends, and receiving in exchange surplus matzot from the Jews. But the canvas was more intricate than such idyllic scenes suggest: “This tranquil life did not conceal ambiguous attitudes, especially in light of political developments, and in particular the growing Arab rebellion movement and the escalation of the conflict between it and the British, as well as the growth of the Zionist movement and the clarification of its intentions regarding Palestine” (al-‘Askari 1989, 67).

So What Happened in 1929?

The skirmishes over the Western Wall and al-Aqsa caused tension and discord in Safed as well. Rumors about events in Jerusalem reached Safed much elaborated, describing a Jewish attack on al-Aqsa and the city’s Muslim community. Tempers in Safed flared; the local mufti, Sheikh As‘ad Qadura, and others tried to calm them (‘Abasi 1999). On Thursday, August 28, a large protest assembly against Jewish attacks in Jerusalem was held in the al-Suq Mosque, located in Safed’s marketplace. The commander of the local police, John Faraday, rose to offer reassurances but was unable to pacify the crowd. According to al-‘Askari, Faraday confirmed that the Jews had attacked al-Aqsa and that they had forcefully taken control of al-Buraq. He declared, however, that the government was in control of the situation and would punish the offenders. Faraday’s speech only exacerbated the fury of the masses.

Faraday spoke in Arabic but was apparently misconstrued by his audience, members of which began calling out “Revenge!” and “If we don’t defeat the Jews, they will defeat us!” (‘Abadi 1977, 136). Yet what incensed the crowd even more, according to al-‘Askari, was a report that reached the protestors while the rally was still in progress. It said that the body of Ahmad Tafish had been found near Safed’s Jewish quarter. Tafish was also known as Sheikh al-Shabab, the leader of the youth.

What set off this rumor? It might have been an incident that took place that afternoon, during the rally at the mosque. After addressing the audience, Faraday had set out on horseback for the Jewish quarter. He saw Jews running and calling out “Arabs, Arabs!” He advanced to see what was going on and to calm things down. A Jewish officer, Kalman Cohen, and an Arab officer, Shawkat Mubashir, also arrived. They found a badly wounded man. The victim’s dress and looks convinced the police officers that he was an Arab. To prevent a further escalation of tension, they took him into a building off the main road (Commission 1930; 2:1028).

It was only the next day that it was determined that the victim, who had since died, was a Jew. His name was Yitzhak Maman, and like many Sephardi Jews he normally dressed like a franji (a Westernized Arab). Yosef Benderly, born in Safed in 1900 and a local member of the Haganah, witnessed the murder, but had no means of saving Maman. The two men had been walking down the street when they were attacked by four Arabs. Benderly was able to get away, but the four assailants began to beat Maman with sticks. The survivor testified in court that he had heard the victim calling out to one of the attackers: “Ahmad, have mercy!” But Benderly was unable to say what happened subsequently. Benzion Borodinsky, a physician at the town’s Hadassah clinic, testified that Maman was brought to the clinic with his ribs broken and his lungs punctured. The doctor tried to save him, but the broken body could not hold out and Maman died in surgery. One of the suspects in the murder was Ahmad Tafish. In other words, it was not the leader of the youth who had been murdered during the gathering in the mosque. Instead, Tafish had murdered Maman (Criminal Assize 20/30 Haifa—Ahmad Khalil Tafish, in TNA CO 733/181/4).

Maman’s widow, Malka, testified in court that on the operating table, before his death, her husband told her who had attacked him: “He said: ‘Ahmad Tafish, Ahmad Ghana’im, and Awad Ghana’im.’ He was breathing with difficulty. I stayed with him until the morning. He’d utter a single word and then lose consciousness” (ibid.). The defense attorneys claimed she was lying. She responded: “I swear that he himself and no one else told me the names. May God send me to him if I am lying.” The court, however, rejected her testimony (it had good reason to be suspicious of the witnesses—recall that future Supreme Court Justice Zvi Berenzon confessed that he lied at the trial of the Safed murderers). But Tafish did not go free. He was sentenced to fifteen years in prison for the murder of the elderly Khanum Cohen in full view of her son Shmuel, who testified to the crime in court.

Only Fifteen Years for Murder?

The prosecution sought the death penalty for a charge of premeditated murder, but Tafish’s lawyer, Hasan Asfur, cited the precedent of Simha Hinkis of Jaffa, whose story appears in chapter 1. The Muslim assailants had not plotted in advance to murder Jews, Asfur argued. Rather, having heard that Arabs had been killed by inhabitants of the Jewish quarter, angry Muslims set out to take revenge against the Jews and killed some in the heat of the moment. Taking a life under such circumstances, he averred, is not premeditated. In other words, the legal parsing in Hinkis’s trial (apparently greased by a bribe) ended up influencing the decisions made in subsequent trials growing out of the riots.

Another Way Jaffa Influenced Safed

We have jumped ahead to the end of the trial, but we are still at the start of the story. Crowds of Arabs exit the mosque. They are angry. They have been told that al-Aqsa was burned and that Tafish had been murdered by Jews. They might have heard something else as well. Binyamin Geiger, who was about five years old at the time, offers this account of the events of that week:

The riots reached Safed on Thursday, August 29. On the previous Saturday a large demonstration was organized. Crowds of inflamed Arabs entered the alleys of the Jewish quarter. The man leading the procession waved a flag, a drummer striding beside him, and they stirred up the crowd with loud roars: “Seif al-din Hajj Amin” [Hajj Amin (al-Hussayni) is the sword of the faith]. The mob smashed windows and ripped off doors. While no one was killed that day, it was a premonition of what was to come. . . . A tense peace prevailed that entire week, until Thursday. That day rioters came out of the large mosque in the heart of the shuk [market]. The riots started after provocative speeches, in which the worshipers were told that Jews had killed five Arabs in Jaffa. (Geiger 2011, 163)

It is interesting that Geiger, a respected citizen of Jewish Safed, who commanded its defense in 1948 and then settled there, cites the murder of the ‘Awn family in the context of the attack on his city’s Jewish quarter. It is hard to see where he got this from. As a Jewish child he obviously was not present in the mosque at the time of the speeches. None of the Arab sources make this connection. And how could the news have reached Safed so quickly when—as part of the British efforts to prevent the spread of unauthorized information—all telephone lines except official ones had been cut and newspapers had been shut down? How is it that Geiger is almost the only source who accurately reports the number of people killed in the attack on the ‘Awn home? Nevertheless, it could well be that some shred of a rumor about what had happened in Jaffa had reached the Galilee, and that this, along with the news from Jerusalem, made the blood of Safed’s Arabs boil.

Geiger continues: “The inflamed rioters broke into the Jewish quarter, bearing knives (cutlasses), axes, and clubs. At their head strode no other than ‘Abd al-Rahman, an Arab laborer who worked at Eisenberg’s bakery. He led the crowd, bearing a huge drum on his shoulder, beating it in ecstasy” (ibid.).

Back to Faraday and His Men

This was just after Faraday and his men had spotted the badly wounded man in the street, thought he was an Arab, and hid him in a nearby building until he could be evacuated to the hospital. At the same time the commander ordered his policemen to deploy rapidly in the Jewish quarter and on the boundary between it and the town’s Arab neighborhoods. But as he, in the Ashkenazi neighborhood in the upper reaches of the quarter, conveyed orders via mounted policemen and tried to organize his forces, the massacre continued. In a report he authored, Faraday acknowledged his failure: “The police do not appear to have got into close contact with the bands of Moslems in the various parts of the Jewish Quarter; while the police were in the upper part of the Quarter murders were committed in the lower part, and when they proceeded to the lower part attacks were intensified in the upper part” (Commission 1930, 2:1028). At one of the Shaw Commission’s sessions, the counsel for the Arab Executive Committee, William Stoker, tried to advance the claim that the riots in Safed began when Jews killed two Arabs there:

Were not two Arabs killed when these were sitting in houses just opposite to each other?—No. They were not killed by Jews.

Who were they killed by?—By me.

By yourself personally?—By me personally.

With your own hand?—Yes.

What were they doing?—They were rushing up the street trying to burn the stores belonging to Mr. Klinger. (ibid., 2:175–76)

It was at about this time that a different band of rioters killed Safed’s elderly Sephardi chief rabbi, Yishma‘el Hakohen.

Rabbi Yishma‘el Hakohen

Hakohen was born in the Persian city of Yazd, in or around 1845. At the age of thirteen he set out with his father on the long trip to the Land of Israel. His father never made it. He died in Iraq, where the boy Yishma‘el remained in the home of an uncle and studied at a local Jewish academy. In 1868 he completed his journey, arriving in Safed at the age of twenty-three. Eight years later he was appointed a rabbinic judge, and in 1904 he was invited to serve as rabbi of the Turkish city of Tire. He spent fourteen years there, until, after World War I, his longing for Safed overcame him and he returned to serve as presiding judge on the Sephardi religious court (Grayevski 1929, 4).

The French journalist and writer Albert Londres and the illustrator Georges Rouquayrol met Hakohen a short time before he was murdered. The rabbi was already weak and homebound. Londres recounted his visits to Jewish communities in Europe and Palestine in a book in 1930, Le juif errant est arrivé (The Wandering Jew has come home; published in Hebrew in 2008). As he wrote there, when he heard about the riots, he rushed back to Palestine. Returning to the house where he had met Hakohen, he recalled that earlier encounter:

I went again to his house. I climbed the stairs. The door was no longer closed. Bloody rags were strewn over the divan he had sat on when he received me. A pool of coagulated blood stained the tiles, like a broken mirror face down on the floor. His fingerprints are smeared on the wall in blood.

“Mr. chief rabbi,” I had said to him then, on this very spot. “Will you permit my friend Rouquayrol to sketch your portrait?”

“My dear guests,” he replied, “the faith of Moses forbids it, but Yishma‘el Cohen no longer sees well. He will certainly know nothing about it.”

He extended me his white hand.

The imprint of his palm, all red, now stands on the wall. (Londres 2008, 175)

Most of the city’s dead were Jews from the Islamic world. Thus, in the context of Safed, no claim was made, as it was in Hebron, that the Arabs attacked only recently arrived Jews. In certain cases the murderers and their victims knew each other fairly well. The person who opened the door for the band that murdered Hakohen was a Muslim who served as a Shabbat goy in his house, performing for the rabbi actions forbidden to Jews on the Sabbath. There were cases of even more intimate familiarity, such as the case of Rashid Khartabil.

Khartabil and the Afriyat Family

Rashid Khartabil was a dairyman, tending goats and cows at his homestead and selling their milk to Jews and Arabs. He was one of ten defendants tried for breaking into the Afriyat family home and murdering the father and mother. Like the others, he denied involvement in the murder, but he admitted to knowing the family. At his trial he related that one of the Afriyat girls had been his lover and had lived in his home for two years alongside his wife and sisters. He related that he knew that this fact was a source of some discomfort for her Jewish family, but that the affair had in any case ended long ago. His Jewish girlfriend had left him and his home, married, and given birth to children (TNA CO 733/181: 56–57).

Intermarriages were not common during the Mandate period, but neither were they unheard of (Ovadiah 2009). In any case, Khartabil told the court that he had not even gotten close to the area of the disturbances. But many witnesses testified otherwise. The court accepted the prosecution’s position and sentenced Khartabil to death, along with Fuad Hijazi and the eight other defendants. Eventually, most of the sentences were commuted, as I will relate below. But we are still in Safed on Thursday afternoon, at the time of the attack on the Sephardi neighborhood. We understand that a shared culture and even close association may well not serve as protection at such a turbulent time. The rioters proceeded from the Sephardi neighborhood up to the Ashkenazi area, where Geiger was playing with his friends.

How Geiger Escaped Death

Geiger relates in his memoirs that he and his playmates suddenly saw their neighbor, Reb Levi Yitzhak, running in panic past the Ha’Ari Synagogue. Pursuing him was an Arab holding an ax in one hand and a club in the other. The children scattered. The Arab began running after Geiger. The boy ran into the yard of the Avrutch Synagogue and, hearing the Arab still running behind him, leapt into the excrement-filled pit in the synagogue’s latrine. He spent several minutes in stinking fear, but the Arab did not think of looking into the pit, and so Geiger was saved (Geiger 2011, 164–65).

Rachel Kahana, sixteen years old at the time, sent an account of what happened to members of her family immediately after the riots ended. She related that when the Arabs arrived at her house, only children were there. Her younger brother ran to call their father, who returned home and hid with the rest of the family in the cellar while the house was under attack: “Father was already despairing of our lives, and we were all trembling in fear and alarm. The children fainted and we did not know what to do” (Kahana’s letters, BHMA, file “1929 riots”). But a while later a police patrol chased away the assailants. The family emerged from the cellar and tried to figure out what was going on around them:

We went up to the roof and there it was, woow, the city was in flames and Hebrew boys were running and shouting: Go up, Jews, come up! To Lunz! To the bank! We were barefoot because it was a hot day, so we had been barefoot at home, so each of us put a child on our shoulders and we are running, running in the crowd with our knees buckling, our hearts pounding, pounding like a hammer. The Arab policemen, amusement showing in their faces, urged us on. Oh, those Arab policemen, they are to blame for it all. For all the horrible destruction. . . . Our family held on, one to the other. I was bearing Budik on my back, Levi had Yocheved, Tzvi had Budis, Haya had Simaleh, Father had Mother, Haya had Rivkeleh, Mr. Zilber had Tzipora. . . . With much effort we all got into the yard [of the Saraya, a government building]. The night was dark and overcast and we couldn’t see a thing. . . . A deathly horror overcame me when I saw the tragic sight in the yard—imagine for yourself a throng of 3,000 people lying flat in a yard filthy with the offal of horses and straw and garbage.

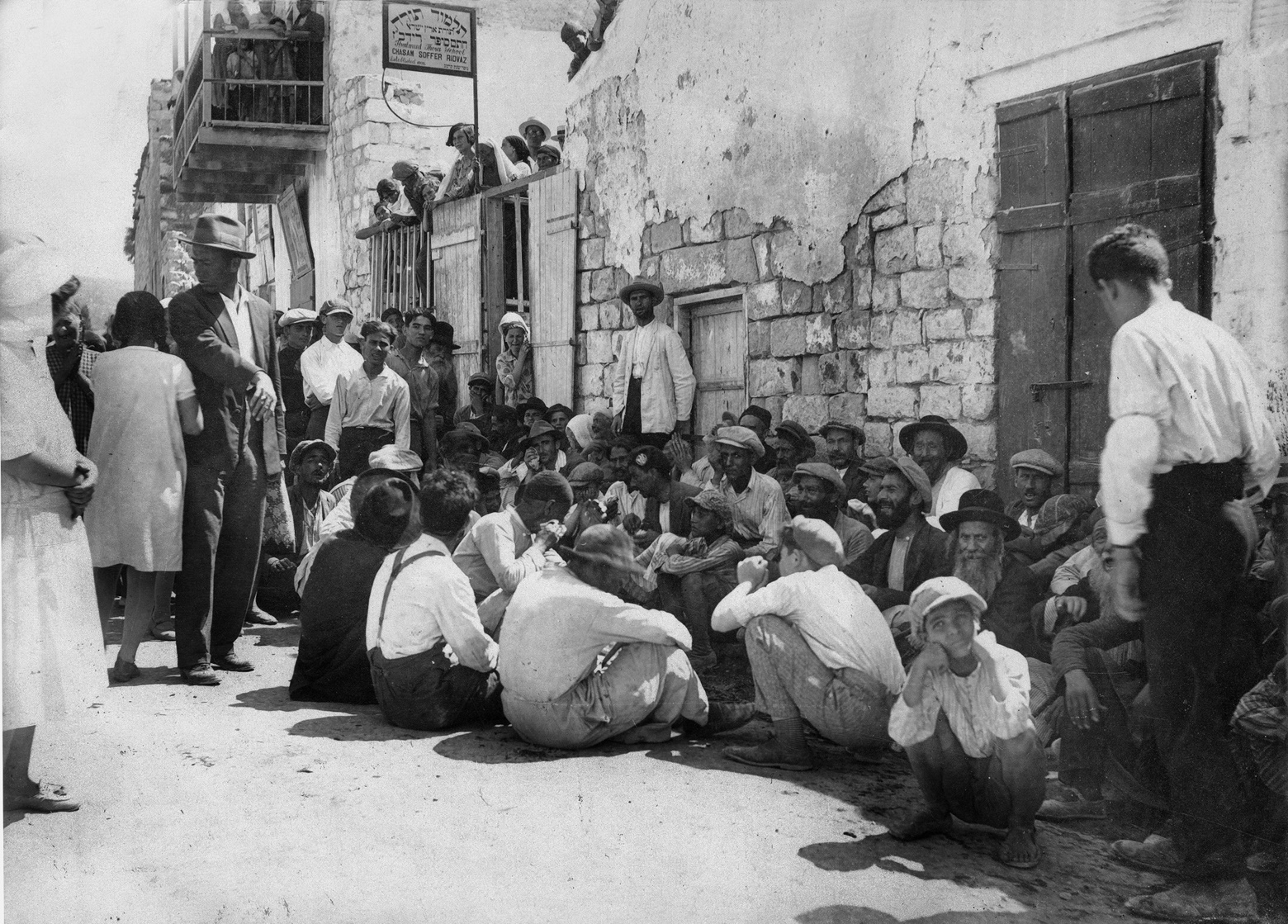

Jews of Safed before the funerals, August 1929 (Central Zionist Archives).

As Kahana recounts here, the police gathered up Safed’s Jews and herded them into the Saraya. Another survivor, five years old at the time of the riots, described these hours in a testimony he wrote eighty years after the events:

One day I heard shouts, cries, and screams, and loud beating on sheet metal. I was frightened. I asked my mother who was shouting and why they were shouting. She told me: It’s the Arabs, who want to kill us. I asked: Why? She said that they wanted to kill all the Jews. I saw a mob of hundreds of Arabs in the street, screaming and shouting. I was frightened. In the evening Mother took me and my sister Naomi to the house of friends of ours. The Arabs threw hundreds of stones at the house, at the windows and shutters. They beat on the doors and shutters with huge clubs and cast blazing torches through the windows. The house began to burn. The shutters, curtains, and even my mother’s and sister’s nightgowns began to go up in flames. (Tal’s testimony, BHMA, file “1929 riots”)

The members of this family also survived, thanks to a group of young Jews who extricated them from their house. They, like the rest of the city’s Jews, were evacuated to the Saraya. The witness goes on to provide the rest of his biography. From Safed his family moved to Be’er Tuvia, which had also been attacked during the riots, and in 1942 he enlisted in the Jewish Brigade and fought the Germans on the Italian front:

We returned from the Brigade and joined the Haganah forces, and took an active part in the War of Independence. During the War of Independence I changed my targets in battle. Before, in the Brigade, I shot at Germans and they shot at me. Now I began to shoot at the Arabs with my personal machine gun and I hit them. Each time I fired a volley I added: Take this and take another. It was revenge for spilling the blood of Safed’s Jews. I thought that it was my right and duty to ensure that the Arabs paid back the blood of the Jews murdered in the riots. To this day I believe that revenge is a duty and is moral. (ibid.)

The person who tells this is General Yisrael Tal, famous in Israel for being the father of the Merkava tank. He served in the Jewish Brigade under Mordechai Maklef, a survivor of the Motza massacre, whose story I have told above. After World War II, Tal took part in revenge operations against the Germans. In his own words, “with the Germans we went crazy. We shot at Germans. We carried out pogroms against the Germans” (quoted in Ginosar and Bar-On 2010, 22).

Tal was one of the officers in the Israeli Defense Forces for whom 1929 was a seminal experience. Another one, as noted above, was Rehavam Ze’evi, and yet another was Yohai Bin-Nun, who served as commander of Israel’s navy. In a detailed testimony for the Haganah History Archives, Bin-Nun relates that his earliest childhood memory was the Arab attack on Jerusalem’s Beit HaKerem neighborhood, and that the first dead body he saw in his life was one of the victims in Bayit VeGan in 1929. These experiences led him to resolve to devote his life to military and security affairs (HHA 141/36).

Tal’s account in the Hameiri Museum Archive offers an understanding of how such a frame of mind was shaped. At the age of eighty-five, he reported a brief exchange he had had with his mother eighty years previously: “I asked my mother who was shouting and why they were shouting. She told me: It’s the Arabs, who want to kill us. I asked: Why? She said that they wanted to kill all the Jews. I saw a mob of hundreds of Arabs in the street, screaming and shouting. I was frightened.”

That is the kind of moment that shapes a person’s life. A young boy finds himself in mortal danger, along with his mother and sister. They are assailed in their home by hundreds of people (Tal’s father was at his job at the electric power station at Naharayim, on the Jordan River). Their neighbors and friends are being slaughtered all around. His mother interprets the world for him: the Arabs want to kill all the Jews. Or at least that is what he remembers her telling him. His mother’s explanation became part of the lens through which he viewed the world, irrespective of its accuracy (in fact, not all the Arabs wanted to kill Jews, and those who wanted to kill Jews did not necessarily want to kill all Jews). As a result of this worldview, he sets out in 1948, so he declares, “to ensure that the Arabs paid back the blood of the Jews murdered in the riots.” Note that he says “the Arabs” and not “the murderers.” That does not mean that these men, looking through the sights of their rifles, made no distinction between a German soldier and an Arab, between an SS officer and a Palestinian fellah. But if we take Tal at his word, the memory of the riots blinded him, making him forget the fact that not every Arab was a murderer, and that in Safed, too, there were Arabs who in 1929 opposed the attacks on the Jews. Mahmoud Abbas is one example.

Mahmoud Abbas

Mahmoud Abbas belonged to the extended family of his more famous namesake, the president of the Palestinian Authority who also goes by the nom de guerre Abu Mazen. Esther Keizerman, later a member of the Etzel underground, provided the Hameiri archive with an account of her acquaintance with him (BHMA file “1929 riots”). Citing the good relations between the town’s Jews and Arabs, she recalls that both Jews and Arabs spoke Arabic, Hebrew, and Yiddish, and that they visited each other’s homes. An Arab maid worked in her family’s home. She also recalls, however, cases in which Jews were attacked by Arabs, frequent cries of “idbah al-Yahud” following Friday prayers in the mosques, and the murder of many Jews by Arabs in such circumstances.

The final claim, like other details she offers, is not accurate. There are no documented instances of Jews being murdered by Arabs in Safed before 1929, certainly not “many.” It is hardly surprising that, in bringing up memories of her early childhood, Keizerman mixes up her chronology and provides inaccurate information. The same happens later in her testimony, when she offers an account of gunfire aimed at the Jews taking shelter in the Saraya, at the end of the attack on Thursday evening. It was an incident that further pained and terrorized an already beaten community. According to Keizerman, “about seventy dead, men, women, and children, were gathered up from the yard after that evil attack” (ibid.). But according to the other sources we have, only two Jews were killed in this shooting—Ayala and Rafael Mizrahi. Keizerman’s young age and panic most likely multiplied the number of dead in her memory many times over. What requires our attention here, then, is not the ostensible facts she provides but rather her impressions. Here is another of her recollections:

One Thursday evening I was getting ready for bed and there were knocks on the door. Father picked up his loaded pistol and went to open the door after checking to see who was on the other side. Two Arab men came in, whom I knew from visits in our house, and we children played with their children. The older one’s name was Mahmoud Abbas and the second was Hajj Ahmad al-Hussayni. They closed and locked the door, sat down, and told Father in a whisper that they had learned that a group of young men had decided to attack him and us, the children. The next day, Friday at dawn, they stationed themselves outside the two doors to the house. Father took out his pistol, loaded it with bullets, hid us under the bed, closed the windows and doors, and the two men with their pistols stood outside at the two entrances to the house. I drowsed off and suddenly I heard horrifying shouts, curses in Arabic, and gunshots. I shook with fear and Elhanan began to cry. I quieted him down and hugged him hard and then I heard a strong voice in Arabic: “You will not enter this house and you will not touch my friend and his family unless you kill me first, and then my family, who are at the ready, will arrive and nothing will remain of you. Leave the house immediately. I am shooting.” They fled. (ibid.)

By the way, not only was Abu Mazen’s family living in Safed in the mid-1920s. So was Binyamin Netanyahu’s grandfather, Natan Milikowsky. He was the principal of the town’s Hebrew-language school, but some four years before the riots he moved to the United States and engaged in public relations for the Zionist movement, as did his son Benzion and his grandson Binyamin. The grandfather belonged to the Revisionist movement, Zionism’s maximalist faction.

Revisionists in Safed

Milikowsky wasn’t the only Revisionist in Safed. The movement was growing rapidly there on the eve of the 1929 riots. Eitan Wijler, who worked in the Hameiri Museum archive, later wrote about this in a master’s thesis he authored. Its title speaks for itself: “Kitzonim Tzionim veFalastinim: HaMikreh shel Me’oraot TaRPa’’T beTzefat” (Extremist Zionists and Palestinians: the case of the 1929 Riots in Safed). According to Wijler:

Both Hajj Amin, through his men, and the Revisionists, through their people, made great efforts to export the conflict beyond Jerusalem and bring it to the Land of Israel’s northernmost city. Those elements were not satisfied with offering Safed’s population general news about the conflict, but rather made efforts to persuade them to accept their positions in the dispute. Both Hajj Amin and his people, on the Arab side, and the Revisionists, on the Jewish side, brought to Safed the same policies that they pursued in Jerusalem, on the matter of the Western Wall. Their policies led to growing extremism and the deterioration of the situation. (Wijler 2005, 137)

The claim that the Revisionists bore some responsibility for fanning the flames just prior to the riots—on the national level, not only in Safed—was made also by Ha’aretz (although following the disturbances it blamed the Arabs solely) and by Sefer Toldot HaHaganah—more on that in the next chapter. But we should not deduce from that that the absence of extremist Jews in Safed would have prevented the attack on its Jews. On the one side was the example of Hebron, where the city’s Arabs attacked its Jews because they viewed them as part of the Zionist collective, even in the absence of Jewish nationalist activity in the city. On the other side was the example of Tiberias, where Jewish and Arab community leaders were able to keep tempers in control and to prevent casualties. The case of Tiberias shows that local leaders can avoid violence, even in times of crisis. That is, they can set their community outside national disputes, or at least avert violent manifestations of such disputes.

And after an Outbreak of Violence

After the massacre, Safed’s Jews and Muslims continued to live side by side. The British wanted to evacuate the Jews from Safed, in part because of the sanitation crisis that followed the riots—bodies lay in the streets for several days, and there was fear that an epidemic would break out. But the Zionist leadership sent Yitzhak Sadeh from Haifa and Shlomo Ze’evi from Jerusalem to reorganize the community and clean up the Jewish quarter, thus avoiding the evacuation. The crisis of confidence between the two communities, however, proved difficult to assuage. Many Jews felt betrayed, even though there had been a few cases of Arabs rescuing Jews and despite the fact that a delegation representing Arab families came to the Saraya, bringing food to the Jews as a gesture of reconciliation and goodwill and to symbolize that they had not been involved in the crime (Wijler 2005, 95). Both sides knew that the dead could not be brought back to life.

The police officer Dov Ben Efrayim related, in testimony to the Haganah History Archives that when he was sent to collect testimonies about the massacre, “Many of them, the Jews, were afraid to talk because they had been in Safed for generations, and the Arabs had been their friends at first. They had never imagined that the Arabs were capable of doing such things, because they had lived with them like brothers, and suddenly something like this had happened. They knew that they would have to continue to live there, so they were scared of testifying” (HHA 135/20). The town’s Arabs, for their part, had other concerns. More than 250 Arab inhabitants of Safed had been arrested by the British police. Many of them were heads of families, and their absence left their families without their main means of support. On top of this, the local residents had trouble finding the funds to pay their relatives’ legal expenses (‘Abasi 1999). The Arabs brought their grievances before the Supreme Muslim Council, and on September 4, Mufti Hajj Amin al-Hussayni sent a letter of complaint to the British high commissioner.

The Complaint of Safed’s Arabs

In his letter, the mufti laid out the claims of the Arabs: The disturbances had begun because of Jewish aggression: Jews had opened fire on unarmed Arabs on the town’s streets. On the sole basis of Jewish accusations, the police had arrested many Arabs, including merchants and other respected citizens known for their integrity and uprightness. After the riots, the Jews looted and set fire to Arab commercial establishments. Arabs, too, had been killed in the riots, and therefore Jews should also be arrested. The man the government sent to Safed to represent it was a Jew who favored the Jews and harassed the Arabs. The mufti’s letter is preserved in the Supreme Muslim Council’s archive in Abu Dis, and was published, along with other documents relating to the 1929 disturbances, in the journal Hawliyat al-Quds (Hammuda 2011).

The mufti dissimulates in his letter. Only two Arabs were killed in Safed, both of them—as noted above—by Police Commander Faraday. Jews caught looting were brought to trial, but other Jews were falsely accused of this crime by supposed witnesses. The charge that Jews had opened fire on Arabs and set off the riots was shown to be untrue.

In the end, eighteen of the Arab detainees were sentenced to prison terms of between three and fifteen years. Fourteen were sentenced to life imprisonment, and another fourteen to death. Of the latter, thirteen had their sentences commuted by the high commissioner. Only one, Fuad Hijazi, went to the gallows, convicted of incitement and involvement in the murders of the Afriyat family and Mazal Cohen.

The End

In the weeks and months following the massacre in Safed, while the murderers were still on trial, a few Jews and Arabs began discussing ways of returning to normal. The idea of a sulha, a reconciliation ceremony, was broached. Yosef Nahmani, a Keren Kayemet functionary and veteran of an early Jewish self-defense organization, HaShomer, met with advocates of reconciliation on both sides. The Zionist leadership supported the idea but preferred that the Arabs, rather than the Sephardi community, take the initiative so that the Jews would not give an appearance of weakness (Nahmani letter to Kisch, May 1930, CZA S25/4429). Another such proposal came from two public figures—Meir ‘Abu, scion of a long-standing and well-off Safed Jewish family, and Na’if Subh, Safed’s Arab mayor. They tried to set up a local organization called Brit Shalom (unconnected to the movement of the same name centered in Jerusalem). ‘Abu received a certain measure of support for this from the United Bureau, a body established by the Zionist Organization and Jewish National Council to handle Jewish-Arab relations in Palestine.

According to Mutstafa ‘Abasi (1999), ‘Abu and Subh’s effort failed. Many Jews and Arabs, it seems, had no interest in a common framework. The town’s Jews and Arabs continued to live side by side for lack of an alternative, but the scars left by the riots did not fade. Beyond the unbearable pain felt by individuals, and beyond the different points of view within each community, each group reached a collective consensus. For the Jews, the Arabs were murderers. The Arabs, for their part, felt more strongly than ever that they were facing a large and organized force that wanted to take over their country. Here is Keizerman’s account, in her testimony for the Hameiri Museum archive, of how she interrupted a conversation between her father and Abbas, who visited their home a short time after the riots. She told Abbas:

“Every Friday you go out into the streets shouting idbah al-Yahud, idbah al-Muskub, din Mohammad bil-seif, and every passing Jew dies, whether from knives or axes. . . . How can your hatred be explained? Why are you doing this and what do you really want from us?” He [Abbas] was shocked, he patted me and tried to calm me. He said that only bands of undisciplined young people had done such things. You, too, have young people who kill Arabs for revenge. I didn’t know about that and his words mollified my anger. I said: “I hope that’s true. It’s about time that you also feel suffering, pain, and death as we do.” After he left I began shouting at my father: “After what they’ve done to us you sit down with them?” He then seated me and my brother next to him and said: “If you have any complaints, make them to the Patriarch Abraham. The Arabs are the descendants of Ishmael and Esau and we are the descendants of Isaac and Jacob. This land belongs both to them and to us.”(Keizerman testimony, BHMA, file “1929 riots”)

The father’s ideal of Jewish-Arab friendship did not get carried over to the next generation. The idea that the country belonged to both nations remained the preserve of just a few. The younger Keizermans and their Arab contemporaries did not feel that they belonged to the same urban fabric or that they all belonged in some way to some larger community. They faced off against each other to fight for control of the land, each community convinced that justice was on its side.

Jews and Arabs continued to live together in Safed for another twenty years following the riots, with fluctuating levels of accommodation and animosity. The murderers and their abettors were gradually released from prison and returned to the city streets. Wijler, relying on testimonies in the Hameiri Museum archive, relates that one of the murderers returned to man a stall in the Jewish quarter. When he was asked about his deeds in 1929 he replied: “What can I say, a demon got in me”(Wijler 2005, 93). During the Arab Revolt of 1936–39 tensions increased and did not subside until 1948. In May of that year the Palmach conquered the town in Operation Yiftah. The background to the operation was, writes the historian Anita Shapira, “the traumatic memory of the massacre that the Arabs committed there against the Jews during the 1929 riots, leaving a profound premonition that such a thing could happen again.” In her account of the Palmach operation, she writes that “in the process of taking key points in the city, central buildings in the Arab Quarter were shelled, and the bombardment of the Jewish Quarter by the Arabs continued. The bombardments, the falling of commanding points in the city, and the conquest of the village of ‘Akbara led to a huge panic in the Arab Quarter. Mass flight ensued. The way through the ‘Amud channel in the direction of Meron and Sa‘sa‘ remained open and the refugees took this path. Yigal [Allon] always made sure that a way was left open for the Arabs to flee. When the Palmach forces entered the Arab Quarter the next day, they found a ghost town” (2007, 197).

But that happened nineteen years later. In the meantime, Jews and Arabs throughout the country had to cope with the bloodshed of August 1929 and what it had produced.