Chef Ade

OBE KITCHEN

22

NIGERIA

Though she grew up in Lagos, Nigeria, in a family of internationally educated professionals, Ade had always been one of her family’s most creative, hands-on members—and the one sibling who never went to boarding school: “During my younger age, I thought, I’m not smart. I just made up my mind that I’m going to use my hands to be successful, thinking, It doesn’t matter if I don’t go to school.”

Ade came from a big family that celebrated everything, so often upwards of two hundred people would come over for parties at their compound. For Christmas, for example, a whole cow would be slaughtered and cooked, then they would set up tents and chairs in the courtyard, and jollof rice would always be part of the feast. Starting at age eleven, Ade was already passionate about food and did what she could to help the hired cooks at every family party. “I would tell my mom, No, we don’t need to employ people to cook. I will do it!”

Long after her siblings had all moved to the US, starting careers and families there, Ade stayed rooted in her family home in Lagos, where she was raising her own kids. Life was good: “I was used to living big. Before I wake up—I always had somebody living with me: my aunt, my friends—before I wake up, somebody tells me, Your food is on the table. At that time I had a shop. There is a driver waiting to take me to my shop.”

Ade finally, semi-reluctantly, came to join the rest of her family in the US when her siblings managed to convince her that it would be good for her kids. Once she got here, she was shocked at how isolated people were from each other, how hard people had to work to get by. “So when I came here I said, What is all this? They tell me, You can’t live big at all. You can’t do this, you can’t do that. . . . At first I was thinking, Why did I come in the first place?”

Determined as she was to be able to afford a good American college education for her kids, however, Ade rolled up her sleeves and started monetizing the one skill she knew would never fail to impress: her cooking. She had no trouble preparing feasts for three to five hundred people completely on her own, sometimes staying up all night for days in a row to do so. When clients asked for a recipe she didn’t know, she’d do extensive research, compare and contrast different techniques, and would only use the freshest ingredients.

“For me, before I present food to someone, I eat it myself. I don’t use any preservatives; I don’t used canned anything—I make food from scratch. I don’t mind if it takes a long time.”

Her first catering clients and their graduation-party guests were so wowed by the flavors Ade put together that recommendations and more catering gigs soon started streaming in. Now Ade works as a nurse by day and caters by night, and enjoys sharing her culinary wisdom with her US-raised, fashion-professional niece, Mary Adeogun, who, with her creative director brother, David, started Obe Kitchen in 2017—a vending, pop-up, and educational project committed to preserving and celebrating Nigerian and West African cuisine.

Mary says, “My brother and I couldn’t find the taste of our Auntie’s food in New York City, and we thought, I can’t imagine how many other people are looking for those flavors and that familiarity of home—and so that’s what got us involved with the Night Market. And after that we realized that, yes, there’s getting the food out there, but there are also ways to share stories and recipes about food so people can explore it on their own and do it in their homes and things like that. So we started cataloging recipes, and one of the first ones we did was jollof rice—Auntie’s specialty.

I called up my Auntie, wrote down her recipe, and then started doing it in my apartment. I can’t tell you how many times I tried and failed: I made funky jollof rice, tasteless jollof rice—even to this day I can’t achieve the smoky jollof rice that Auntie makes. Even though I use a big heavy pot, it doesn’t smoke the same way as an outdoor burner.”

“IN NIGERIA WE HAVE A SPECIAL POT FOR COOKING JOLLOF RICE. WE DON’T HAVE IT HERE, SO I HAVE TO IMPROVISE . . . I HAVE TO DO IT ON A GAS STOVE OUTSIDE. IF SOME PEOPLE TELL YOU, I COOK JOLLOF RICE IN THE OVEN, THAT IS NOT JOLLOF RICE . . . THAT IS A CONCOCTION!”

Ade added, “In Nigeria we have a special pot for cooking jollof rice. They call it ikoko irin. We don’t have it here, so I have to improvise one similar to that. If I have to cook jollof rice, I have to do it on a gas stove outside. If some people tell you, I cook jollof rice in the oven, that is not jollof rice. . . . That is a concoction!”

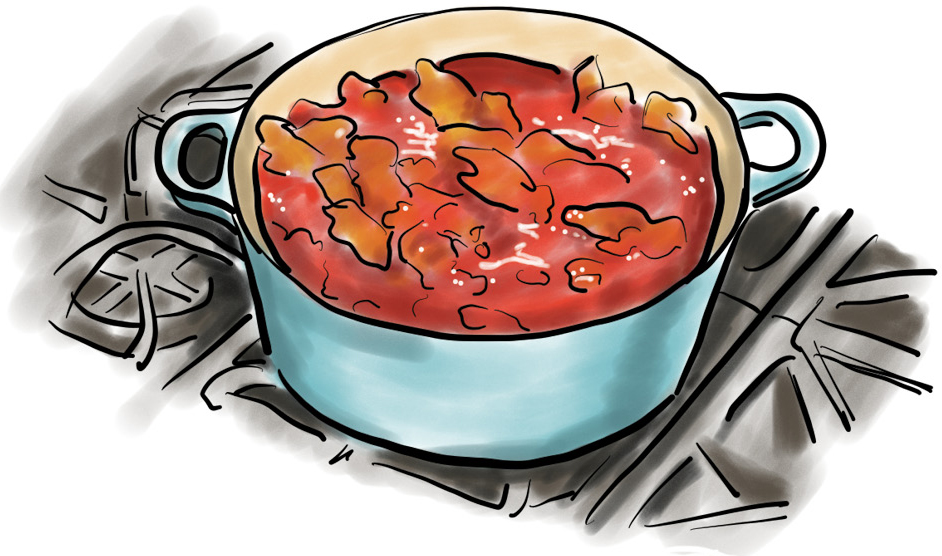

OBE ATA DIN DIN

Fried Stew

Walk into any Nigerian home and odds are you’ll find a large pot of stew in the fridge or on the stove. Ata lilo, a sauce of puréed tomatoes and peppers, serves as the base for this and a whole family of related stews. Enjoy obe ata with a starch, such as white rice, iyan (cooked and pounded yam flour), or eba (cooked and pounded fermented cassava flour). It can also be served alongside other stews, such as ila (okra stew) or efo riro (vegetable stew).

Makes 8 servings

2 pounds (1 kg) assorted meats (such as goat, beef, beef offal, fish, chicken), cut into 2 to 3-inch (5 to 8 cm) cubes

1 medium sweet Spanish onion, roughly chopped

½-inch (13 mm) piece peeled fresh ginger, chopped

1 garlic clove, chopped

1 chicken or beef bouillon cube or 1 teaspoon Maggi seasoning, plus more as needed

Salt

ATA LILO

7 medium plum tomatoes

2 red bell peppers, seeded and roughly chopped

1 medium sweet Spanish onion, roughly chopped

2 Scotch bonnet chiles (ata rodo) or 4 habanero chiles

3 cups (720 ml) high-heat frying oil*

6 to 8-inch (15 to 20 cm) piece of panla (smoked stockfish), soaked overnight and torn into small pieces, optional**

1. Place the meats, onion, ginger, garlic, bouillon, and a pinch of salt in a large pot. Add enough water to just cover the meat. Bring to a boil and cook over medium heat until just barely cooked, 10 to 15 minutes, depending on the tenderness of the meat. Remove the meat and reserve the stock for later.

2. To make the ata lilo, purée the tomatoes, bell peppers, onion, and chiles in a blender or food processor on high until completely smooth. You may need to blend in batches and add 1 or 2 cups of water to help the mixture blend. Set aside.

3. To make the stew, heat the oil in a Dutch oven or large pot over medium-low heat and then fry the meat until the outer layer is browned and crispy, 10 to 15 minutes. A long low-heat fry is necessary to maintain the characteristic crunchy texture even upon reheating. Remove the meat and set aside.

4. Increase the heat to medium-high and add the ata lilo to the oil. You should hear the immediate sizzle of the ata lilo beginning to fry.

5. Add 1 or 2 ladles of the reserved stock to the pot and season with salt and bouillon as desired. Add the panla, if using. Cook, partially covered, until the stew has reduced by at least one-third and deepened to a dark red. Reduce further, if you prefer thicker stew. Return the meat to the stew and let simmer over low heat until heated through, 5 to 10 minutes.

6. Let the stew settle for 5 to 10 minutes. Skim any extra oil off the top of the stew and serve.

* It is traditional to use palm oil in this recipe and in much of Nigerian cooking. It has a high smoke point and imparts an undeniable and unique flavor to West African dishes. However, given the controversy surrounding it, we leave the choice of oil up to the reader. In addition, palm oil may need to be partially bleached, which is itself a tricky and dangerous process in a home kitchen.

** Panla is available in West African or pan-African grocery stores.

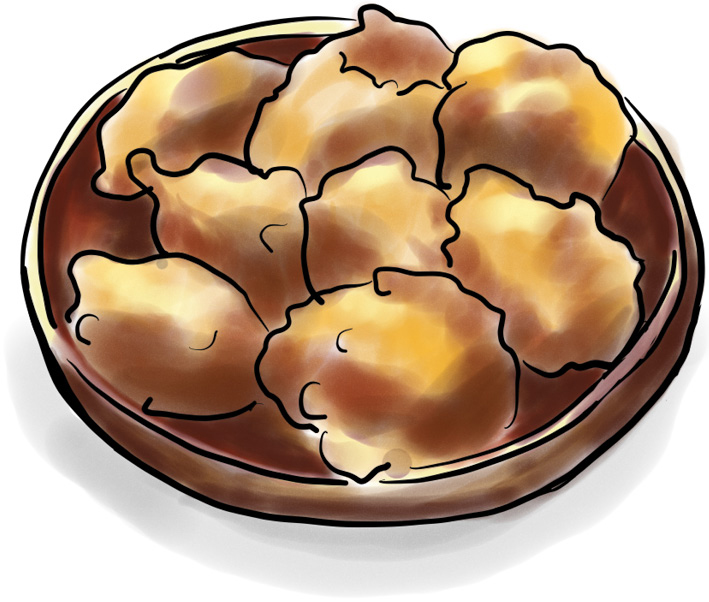

AKARA

Brown Bean Fritters

Akara are fritters made from oloyin, Nigerian brown beans or honey beans. Akara is typically eaten for breakfast, paired with ogi, a fermented corn porridge. It is also sold freshly fried by street vendors. For Mary, biting into akara, a crunchy exterior giving way to a hot, soft, savory interior, gives the same satisfaction as eating a perfect french fry. A Gambian friend of hers recently introduced her to eating akara inside a French baguette, topped with caramelized onions. If oloyin is not available, black-eyed peas can be substituted.

Makes 6 servings

2½ cups (480 g) dried oloyin (brown beans or honey beans)

1 small yellow onion, roughly chopped

1 Scotch bonnet chile (ata rodo)

½ teaspoon salt, plus more to taste

½ teaspoon adobo seasoning, Maggi, and/or chicken bouillon

Vegetable oil, for frying

1. Soak the beans in a large bowl of water, to loosen the outer layer, for at least 3 hours but ideally overnight.*

2. Peel the beans in the water by rubbing them against your hands and against one another. The loosened outer layers will float to the top. Discard these and continue agitating the beans until they are fully peeled. They should look uniformly beige or off-white.

3. Drain and transfer to a high-powered blender. Add the onion and chile. You may need to do this in small batches to avoid overworking the blender. Blend while adding a few splashes of water at a time as needed, up to 2 cups (480 ml), until just uniform but still a bit grainy; when you dip a spoon in the batter, it should still hold on the spoon, not flatten out completely and drip off.

4. Season the batter to taste with salt and adobo. Start with a ½ teaspoon of each and go from there.

5. Pour about 2 inches (5 cm) oil into a deep, heavy pan and heat over medium heat to about 350°F (180°C).

6. Carefully drop the batter in a tablespoonful at a time. Each spoonful should hold shape, drop quickly to the bottom, and then bob back to the top. If your batter sinks, the oil isn’t hot enough. If your batter starts browning immediately, the oil is too hot. If your batter spreads out wildly, the oil is too hot or your batter is too thin. The pan should be full but not overly crowded.

7. Fry in batches until the undersides are golden brown, 4 to 6 minutes, then flip and cook until golden brown all around, 4 to 6 more minutes. The cook time will vary based on the thickness of your akara. If it still tastes of raw bean, lower the oil temperature and fry for longer.

8. Remove from the oil and place on a cooling rack to drain. Serve hot.

* If you forget to soak them overnight, add the beans and 1 1/4 cups (300 ml) water to a high-powered blender, then pulse for a few seconds. This starts to break down the beans so the outer layer releases just as easily as if they’d been soaked overnight.