The San Juan Islands of Washington State and the Gulf Islands of British Columbia form a cozy archipelago split by the international border. The rocks here are a smashed mishmash of largely Cretaceous sedimentary rocks known as the Nanaimo Group that was later overrun, gouged, and polished by the ice sheet from the north. These islands are the mellow cruising grounds of the fleets of pleasure boats that stock the marinas of the Salish Sea. Sheltered from rain by the Olympic Mountain rain shadow, they are dry and mild. Pods of orcas favor the west side of San Juan Island. All in all, these idyllic islands are the kind of place you imagine you might retire.

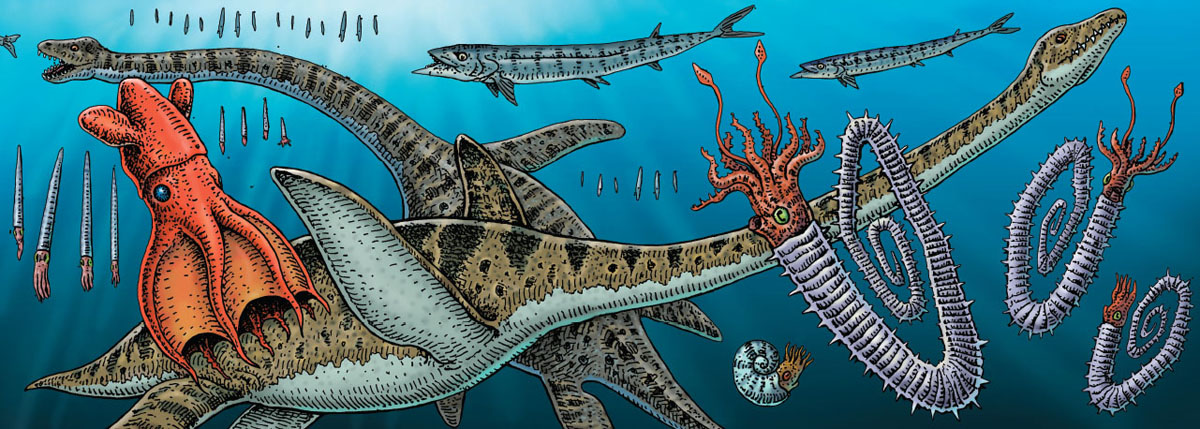

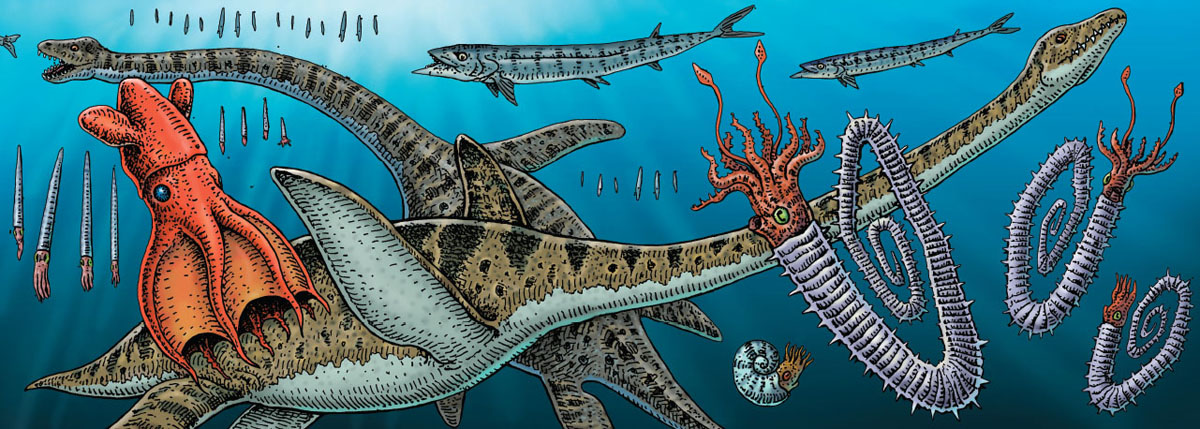

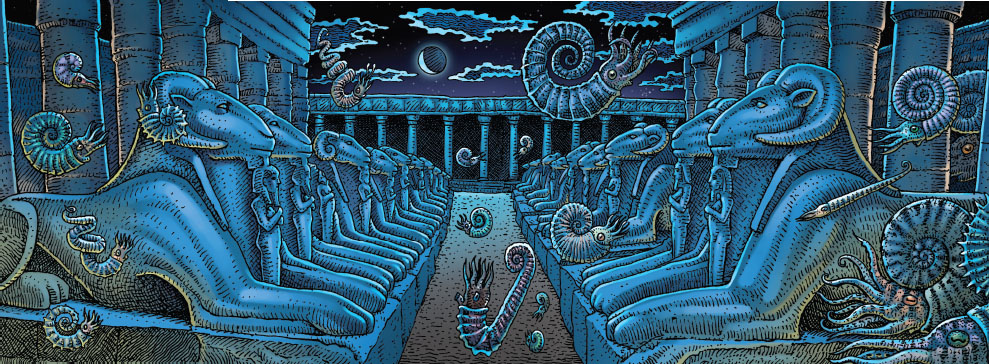

Long-necked elasmosaurs, Saurodon fishes, ammonites, baculites, and a vampire squid cruise the waters of the Cretaceous Salish Sea.

As a teenager, I crewed on sailboats around the islands and worked at a salmon cannery in Friday Harbor. I have very sleepy but strong memories of spending long nights up to my waist in concrete holding tanks full of pink salmon. This species of salmon are also known as “humpies” because the males develop exaggerated humpbacks (and hooked jaws) during spawning. One of Ray’s most popular T-shirt designs was one entitled “Humpies from Hell” and was based on the general hatred of all cannery workers for the pink salmon because of its soft flesh and propensity to spoil. Having lived my own Humpy Hell, this shirt was the first image that made me aware of Ray Troll. The pink salmon commercial fishery is now extinct in the San Juan Islands, and the cannery is just another abandoned building. Given their geological history, the San Juan Islands also hold the evidence of other extinctions.

One island had a special place in my memory because of a specimen case at the Burke Museum that was full of pearly shelled ammonites and baculites. The labels said Sucia Island, and I soon learned that the Burke Museum had launched a series of trips to this oddly shaped little island to extract marine fossils from the Nanaimo Group. Eventually I visited the island myself, only to learn that it was a state park and no fossils could be collected without a permit. I walked the wave-cut terraces and saw a variety of fossils poking out of the crumbly slopes.

In January 2014, I came to Seattle to present a lecture about the dangerous geology of the Pacific Northwest. It was a Rip Van Winkle talk because so much had changed in the thirty-six years since I had moved away in 1978. What had changed was a raft of new discoveries about faults, earthquakes, tsunamis, landslides, and lahars.

One thing that had not changed was that there were still no dinosaur fossils from Washington.

The Vancouver Island Cretaceous Sea

I had recently surveyed the fifty states and learned that only thirty-six had yielded dinosaurs. The unlucky fourteen were places like Maine, Vermont, Hawaii, and Rhode Island, where there was little to no rock from the Triassic, Jurassic, or Cretaceous periods, the time when dinosaurs walked the land. There were a few states with Cretaceous rocks but no dinosaurs. Washington was one of those states.

In my talk, I made fun of the geologists in the room and challenged them to work harder to resolve the Washington State dinosaur deficit. After the talk, and much to my surprise, a University of Washington professor came up to me and quietly said, “I can’t tell you anything definitive yet, but we have just found the state’s first dinosaur.” I had to wait fourteen months until Brandon Peecook and Christian Sidor published a paper describing a partial femur of a tyrannosaurid dinosaur that had been discovered on Sucia Island by none other than Jim Goedert.

Strolling Sucia Island’s rocky shores on a calm January 1.

Jim had been visiting Sucia with David Starr, a Seattle-based stockbroker and fossil enthusiast who had obtained a permit from the park to collect fossils. On one trip, Jim found a loose piece of broken bone but left it on the beach because it had no diagnostic features and was thus worthless to science. He thought that it might be the remains of a marine reptile such as a mosasaur, which is what you would expect to find in a geologic formation full of ammonites. On a subsequent trip, Jim found a larger bone sticking out of the bedrock and realized that the earlier fragment must have broken away from the larger piece still embedded in the rock. He searched the beach and relocated the previously discarded chunk and found that it was part of the larger bone. Now that he had something identifiable, he called the Burke who excavated the bone and realized it was from a dinosaur.

Dinosaur paleontologists have a phrase for the phenomenon of land fossils in marine deposits. They call them “bloat-and-float” fossils. Imagine that an animal dies along the banks of a coastal river and has a chance to bloat with the postmortem gases of decay. If this fetid carcass then gets carried downstream, it is possible that it will drift out to sea. Eventually it will lose its buoyancy and sink to the seafloor, where it is buried in the mud alongside the remains of marine animals from the water column and the seafloor. For this reason, there are several dinosaurs known from marine deposits around the world. Jim had found Washington’s first dinosaur, and it was one bone from a bloat-and-float corpse.

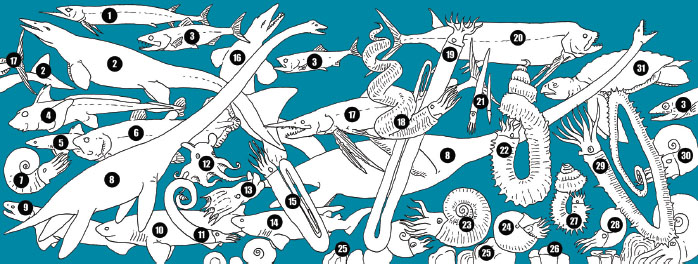

Ray had been in contact with Brandon and had prepared an image of an upside-down tyrannosaurid corpse floating in a sea full of ammonites. True to the concept of the eternal coastline, the sea has always been the sea, but it has been inhabited by some very different beasts over time.

The carcass of a tyrannosaur dinosaur bobs lifelessly in the Cretaceous Salish Sea.

My friend Tom Grauman invited Ray and me to join him in Friday Harbor on San Juan Island to celebrate the New Year of 2015 by boating to Sucia Island. For Tom it was an annual expedition. For Ray and me, it was a chance to see the site of Washington’s only dinosaur. It was a surprisingly calm and clear January 1 as we slipped out of Friday Harbor and motored north around the west coast of Orcas Island. Sucia is the northernmost of the American San Juan Islands, and from the air it looks like the letter “E” with a couple of extra crossbars. Geologists immediately recognize it as a giant fold in the rock known as a syncline. The Nanaimo Group is a geologic formation that has mudstone, sandstone, and conglomerate, and it is the latter two that make the prominent folded ridges that form the many bays of Sucia. The sandstone cliffs of Sucia had been the source for much of the building stone of Seattle’s Pioneer Square and most of Seattle’s cobblestones. The patio of my dad’s house in Beaux Arts is made of these cobblestones, a fact that I did not realize until this trip. The westernmost bay is called Fossil Bay, and that, obviously, was our destination.

A beach pebble full of fossil clams.

The heteromorph ammonite Eubostrychoceras.

A few hours later, we motored into Fossil Bay and tied up at the dock. Bull kelp floated in the bay and the sun warmly glanced off the red trunks of the madrone trees. The state park had recently installed a small interpretive panel about the fossils of the island, and we set off to see them for ourselves. Ray was really interested in finding more of the dinosaur, which seemed like a long shot to me – but you never know. I was more interested in seeing how many different kinds of ammonites we could see in the cliffs. The tide was high, but we were able to work our way to the western shore of the island and get onto the beach where the receding tide gave us more and more room to stroll.

The sun was out, the wind had dropped, and the surface of the sea was a glassy calm. It was one of those perfect winter days when the weather stands back and lets you enjoy life. We strolled along the rocky beach, looking both at the crumbling cliffs and at the beach cobbles. The cobbles were a mixture of granite pieces that had been delivered to the island by the recently departed ice sheet and chunks derived from the nearby cliffs.

Within minutes, we were finding a variety of clams including Inoceramus, the classic ribbed oyster of the Cretaceous, but also the fan-shaped Pinna and the elaborately flared Trigonia. Normally clams are far more common than ammonites, as they are bottom dwellers and ammonites are swimmers. Clams live where they are fossilized, whereas ammonites swim through the water column and sink to the seafloor when they die.

It was a perfect day, and we did not need too much patience before we found our first ammonite, a smooth-shelled Gaudryceras. Eventually we also found other ammonites, including a ribbed Canadoceras and the bizarrely coiled heteromorph ammonite known as Nostoceras. Our finds were adding up to the inescapable fact that the Salish Sea of 82 million years ago was very different indeed from the Salish Sea of today. We capped off the afternoon by finding a few coiled nautilus shells, which were further evidence of a different world. As expected, we found no evidence of dinosaurs, but it was comforting to know that we had been where Goedert had found Washington’s first. We left the fossils as we found them, embedded in the cliffs, and headed back to Friday Harbor with the sublime feeling of a year well launched.

The Temple of Ammon

The trip to Sucia was the last part of our investigation of the northern Salish Sea. It was a few years earlier, on a sunny summer afternoon in 2012, that Ray and I landed in the Vancouver airport and rented a car. We had only given ourselves a few days to explore Vancouver Island, a task I knew should take months. Our main goal was to see the rocks of the Nanaimo Group and visit a group of amateur collectors who had been finding amazing fossils along the east coast of the 280-mile-long island. There is no bridge to Vancouver Island, so the only way to get there in a car is to take one of the many ferryboats that depart from Tsawwassen or Horseshoe Bay. As we sat in the ferry line, I started telling Ray what little I knew about the ammonites of Vancouver Island, and of all the places I had heard of but had never visited. As I spoke, I realized that we really didn’t have a plan and maybe we needed one. When in doubt, call a paleontologist.

I called Peter Ward, a University of Washington professor and author, who had written his PhD thesis on the ammonites of the Nanaimo Group. Peter is a wildly creative paleontologist who has written more than a dozen well-received books about paleontology. Lately he has been studying the ammonites of Antarctica and the living Nautilus of the South Pacific. Back in the 1980s, he and I had been on the same side of the asteroid extinction argument. He found evidence that ammonites had suffered extinction precisely at the time of the asteroid impact, and I was seeing the same pattern with land plants. Like me, Peter had grown up in Seattle and had been strongly influenced by the Burke Museum. One time, he showed me a car-sized glacial erratic boulder in a park near downtown Seattle that was completely full of Cretaceous clam fossils. Peter answered my call on the first ring, and I told him that Ray and I wanted to be British Columbia ammonite tourists. To my amazement, he said that it would be easier for him to show us than to tell us and that he would catch a floatplane from Seattle the next morning and join us in Nanaimo. Problem solved.

We drove onto the ferry and crossed the Salish Sea, winding through the Gulf Islands that lay alongside the southeastern side of the island. The British Columbia Ferry system employs marine ecologists to give lectures to the passengers, and we enjoyed tales of squid, cormorants, and salmon, and we enjoyed the afternoon. As we approached Vancouver Island, I reminded Ray that the coast west of Victoria had outcrops that had yielded two different kinds of desmostylians: Cornwallius and Behemotops, and that we would soon be landing on the Saanich Peninsula that had once been home to the massive Ice Age Bison latifrons. We landed at Swartz Bay and drove into Victoria in time to visit the Royal British Columbia Museum.

This venerable museum opened in 1886 in response to the growing realization that people were coming from around the world to collect art and artifacts from the Native peoples of British Columbia, and that the province had better start saving some of it themselves. Today, the museum has three galleries: Natural History, First Nations, and the curiously named Modern History.

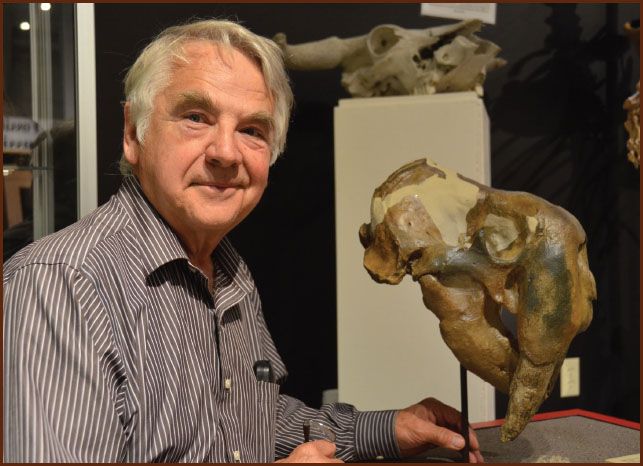

Peter Ward and a portion of Diplomoceras, the giant paper clip ammonite.

The heteromorph ammonite Polyptychoceras vancouverense.

The Native peoples or First Nations of British Columbia represent twenty-seven major groups that speak a total of eight languages. The coastal groups include the Haida, Tsimshian, Gitxsan, Nisga’a, Haisla, Heiltsuk, Oweekeno, Kwakwaka’wakw, Nuu-chah-nulth, Nuxalk, and Coast Salish. These were the people who were living along the coast when the first Europeans arrived, and these were the people who made the monumental cedar houses, ceremonial poles, and enormous boats that impressed the explorers and launched dozens of collecting expeditions. Their items can be seen in museums around the world, and the Royal BC museum contains amazing collections, including many poles that were salvaged from villages that had been abandoned due to smallpox epidemics at the end of the 1800s.

All of these people had made their living along the coast, and their beautiful hand-carved objects are full of images and references to whales, fish, eagles, ravens, beavers, seals, frogs, sharks, octopuses, bears, wolves, and other animals that shared the coastline. Both Ray and I have long been fascinated by these images and carvings and have revered the people that made them. The exhibit was packed with amazing artifacts, but I was really pulled to the stone carvings from Haida Gwaii (the archipelago formerly known as the Queen Charlotte Islands). Made from a silky black rock known as argillite, the carvings were like human-made fossils. The Natural History gallery contained real fossil ammonites from the ancient coastline, and the transition for me was seamless.

The museum also had a number of habitat dioramas that had been painted by Jan Vriesen, an artist who had worked with me in Denver. By chance, Jan was in town, and we met up with him for dinner at the home of Trish Guiguet, the daughter of the former, and longtime, curator of the Royal BC Museum, Charles Guiguet. Trish is a self-described “salmon person,” and we dined in her backyard in the shade of a lovely Metasequoia tree. She told us tales from the 1940s of how the museum collected the animals and plants for the dioramas. Over dinner Jan decided to join us on our drive north. Now it was two artists to one scientist.

The heteromorph ammonite Nostoceras hornbyense.

The next morning, we met the floatplane as it landed in Nanaimo. Peter Ward walked off the dock and leveled the score at two artists and two scientists. This was starting to get interesting. We drove past a pub called the Cranberry Arms, and I recalled that it was known to paleobotanists because a Cretaceous fossil leaf site had been discovered there in the 1990s when roadwork opened a road cut. The Nanaimo Group has rock layers that both formed as seafloor sediment and on land. This is a great combination, since the same sequence of rocks shows what life was like both onshore and at sea. The fossil plants included palms, cycads, broadleaf trees, and conifers. One particularly odd fossil plant from this site was called Protophyllocladus. Its closest living relative is a conifer called Phyllocladus that grows today only on the island of Tasmania off the coast of Australia. That was not an expected discovery.

It was the first time Ray and I had traveled with a personal ammonite specialist, and the conversation rapidly spiraled down the tunnel of cephalopod obsession. Peter connected the dots of the West Coast ammonite story for us. There are four regions along the West Coast that have yielded abundant Cretaceous ammonites: San Diego–Baja California, northern California, southern Vancouver Island (and Sucia Island), and the Matanuska Valley north of Anchorage. He had been working to figure out what the areas had in common and how they were different, and in so doing, reconstruct the world of the Pacific Coast of 80 million years ago. Many of the ammonite species could be found all the way from Baja to Anchorage, suggesting that the difference in climate from Mexico to Alaska was less in the past than it is today. One big difference was that the fossil sites in Baja preserved a type of fossil clam known as a rudist. These were big clams the size and shape of wastebaskets that formed tropical reefs in a world where the waters of the equatorial regions were too warm for coral reefs.

Peter also told us how he had been capturing, tagging, and releasing living nautiluses in the South Pacific to understand how they functioned and fed. He was really worried that the living nautilus was endangered because people loved their shells so much that they were driving them toward extinction. It was a bit ironic that ammonites had met their demise at the hands of the dinosaur-killing asteroid, and we were off to find ammonites with a nautilus expert who was opining about their pending extinction at the hands of humankind. It did make me feel better about collecting the already-extinct ammonites as opposed to the soon-to-be extinct nautilus.

We headed to Denman and Hornby, a pair of islands off the east coast of Vancouver about 100 miles north of Victoria. Hornby is famous for producing some of Vancouver’s finest ammonites, and the competition to find them has been intense. During the past fifty years, private collectors have scoured the island, and there are many fine collections in garages on Vancouver Island. The ammonites are found in concretions, and people have even taken to scuba diving to recover the precious nodules. I had long heard about the famous spot and really wanted to visit. Peter warned us that it required a double ferry ride to get there: one ferry to Denman and a second from Denman to Hornby.

We made the boat to Denman, and Peter took us to a site near the ferry dock. The rocks looked promising, so we spread across the rocky shoreline and began searching for fossils. After a few hours, we had found nothing. Even worse, we realized that we had missed the second boat to Hornby and our visit to this fossil Shangri-La would have to wait for a future trip. It became clear that our best chance of seeing Hornby fossils would be in a local garage.

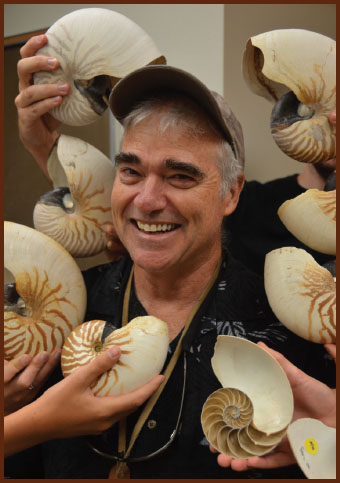

Peter Ward and a school of Nautilus.

We took the ferry back and headed to Qualicum Bay, a sleepy little town about 10 miles down the coast. We had come here to meet a local fossil enthusiast named Graham Beard. It was a sunny late afternoon when the two artists and two paleontologists pulled up in front of a modest bungalow. We were greeted by Graham and his wife, Tina. Graham was a short, silver-haired fellow in a striped shirt and khakis, and right away, I could see that he had the fossil disease. His yard was full of rocks and bones, and he got on topic immediately.

Graham was born in Wales and came with his family to Vancouver Island in 1947 when he was six years old. By the time he was sixteen, he had discovered the ammonites of Hornby, and his life was forever altered. He got the fossil bug bad, became a high school biology teacher, and devoted his life to the fossils of Vancouver Island and British Columbia.

He had a stand-alone workshop that was completely packed with books and fossils, evidence of a long life of living in one place and collecting on a weekly basis. Ray and I have seen many paleonerds on our travels and Graham was a near perfect example of the genre. Many of them have turned their basements, garages, or outbuildings into private museums. Graham had certainly done that, but he had also taken it a step further.

He invited us to take a stroll to the nearby Qualicum Beach Museum. Somehow he had pulled together the local support to enhance a small regional history museum with a very large fossil collection. The museum’s tagline is “You’ll find more than just a little history.” It should be, “You’ll find a ton of paleontology.”

Graham welcomed us into the building like the proud founding father that he was. The small main room was filled with cabinets, cases, and incredible fossils. Graham had been collecting from Hornby for forty-five years, and the results were remarkable. Between his work and that of other amateurs and academic paleontologists, the Cretaceous marine outcrops of eastern Vancouver Island have yielded an amazing list of Cretaceous marine species. The list is a Cretaceous seaway “Who’s Who” that includes ammonites, clams, snails, lobsters, crabs, pufferfish, ratfish, giant squid, frilled sharks, six-gilled sharks, seven-gilled sharks, bramble sharks, dogfish, saw sharks, nurse sharks, sand tiger sharks, horn sharks, sea turtles, the Cretaceous swordfish Protosphyraena, and even parts of the orca-sized marine reptile known as a mosasaur.

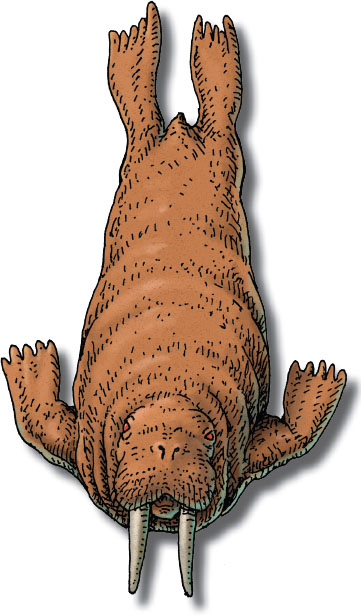

As we worked our way, fossil by fossil, around the crowded treasure room, we finally arrived at the reason I had wanted to come to Qualicum Beach. In 1979, one of Graham’s high school students named Rosie had brought him a portion of a tusked marine mammal skull that her father had found while collecting oysters on a boulder-covered beach 6 miles north of Qualicum Beach. Graham contacted Rosie’s dad, Bill Waterhouse, who, fortunately, had marked the spot. They relocated it and cleared the boulders away, exposing a slick, bluish clay surface. More bones were visible, and they started to dig. The fossil turned out to be a walrus that had been buried on its back with its head facing upward. In fact, it had been the vertically projecting tusks that had caught Waterhouse’s eye in the first place.

Graham Beard and a cast of the skull of Rosie the Walrus

The clay was dense and sticky and dated back to about 70,000 years ago, the middle of the most recent Ice Age. The digging was difficult, and muddy water kept pouring into the pit and making it really tough to see what was going on. Graham recruited his ham radio friend Don McAlister to help with the dig. Don was blind, so he didn’t care that he couldn’t see what he was digging, and soon nearly 80 percent of the skeleton emerged from the Ice Age clay. Graham laid out the bones in his garage, and the fossil walrus found by an oysterman and excavated by a blind ham radio operator turned out to be one of the most complete fossil walrus skeletons ever found on the West Coast. In 1992, Canada’s premier Ice Age mammal specialist, Dick Harington, described the skeleton and counted the growth rings on the tusks. He learned that it was a twelve-year-old female walrus. I was really excited to see the skeleton and was quite disappointed to learn that Graham only had a replica of the skull. The original skeleton had been recalled by Harington to the Canada Museum of Nature in Ottawa. We photographed Graham with the cast and cursed our timing.

It took me three years before I found myself in the offsite storage facility of the Ottawa museum and located the warehouse shelf that housed the incredible skeleton of what Graham had come to call “Rosie the Walrus.”

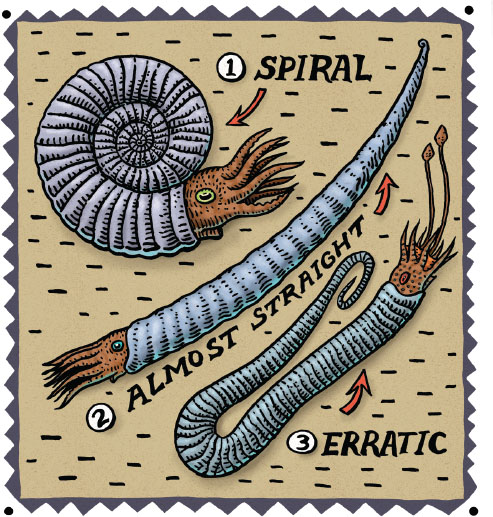

If you pay attention to ammonites, you eventually realize that they come in three different shape categories. Most are some form of a spiral with variations based on how tight the coils are and whether or not the outer coils envelop the inner coils. Then there are straight ammonites known as the baculites, which look like oval rods that can be up to 5 or 6 feet long. The third type includes shells whose shapes appear to be erratic. These are the heteromorph ammonites, and they come in a host of configurations. The Nanaimo Group is known for its heteromorphs, and Graham showed us several. Peter was a heteromorph specialist, so he took over the conversation and told us about the mother of all heteromorphs, an ammonite called Diplomoceras. This was a big animal that had a shell that looked like an enormous 6-foot paper clip. Peter had found his first one in an outcrop farther up the coast. Over the years, he paid attention and eventually found examples on Seymour Island in Antarctica. Others turned up in Alaska, and Peter realized that this species had pulled off a very rare trick in biology. It is really unusual for one species to inhabit a range that includes both polar regions. Today, it happens with Arctic terns, orcas, and humpback whales. Apparently, the giant paper clip ammonite was the Arctic tern of the Mesozoic.

By this time, we had been looking at fossils with Graham for several hours, and hunger was beginning to set in. We said our good-byes and went downtown to check into the hotel and get some food. Ray struck up a conversation with the hotel clerk and asked her if she was aware of Qualicum’s walrus and its legacy of ammonites. She replied that she didn’t pay too much attention to “fancy rocks.”

The next morning, we headed north to Courtney to see another little museum that had been taken over by fossils. We were greeted by director Deborah Griffiths, curator Pat Trask, and several staff who were alerted that a team of paleontologists and artists were incoming. Pat told us the story of how this local history museum, which used to be all about “wagon wheels and arrowheads,” had its transformational moment.

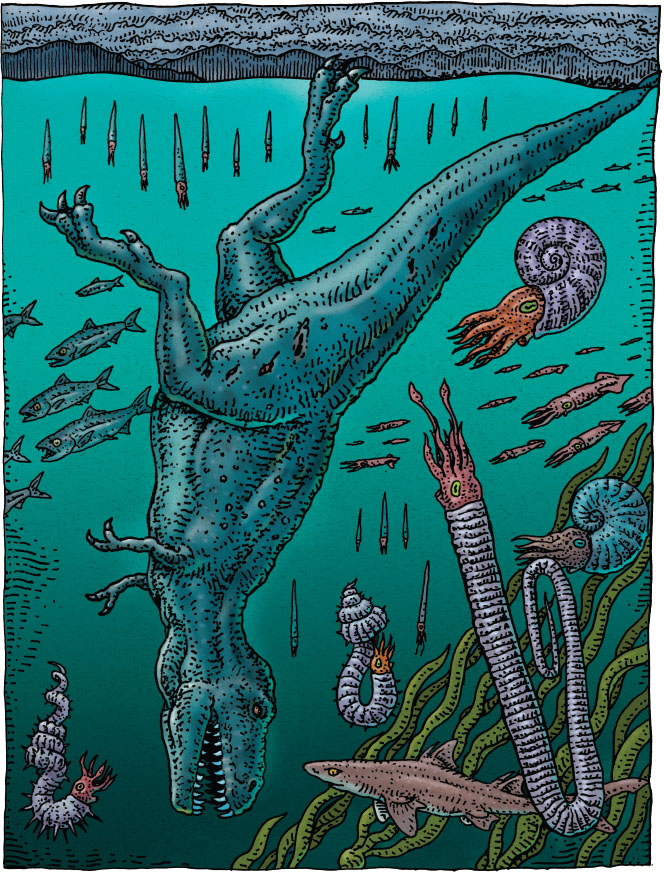

On November 12, 1988, Mike Trask, Pat’s twin brother, and Mike’s twelve-year-old daughter Heather, were hunting for ammonites on the banks of the Puntledge River. Heather found a string of vertebrae exposed in the outcrop, and it was immediately clear that she had found one of the larger denizens of the Cretaceous Salish Sea. Mike and Heather collected a few bones and sought the advice of Betsy Nicholls, the marine reptile curator at the Royal Tyrrell Museum in Drumheller, Alberta. Betsy confirmed that the bones belonged to a long-necked plesiosaur. This discovery created a lot of local excitement; no one had ever found such a thing on Vancouver Island. The museums in Vancouver and Victoria didn’t have the paleontologists to take on a full excavation, so the local amateur paleontologists organized themselves and started to extract the skeleton.

Just a few months after we visited Graham, he got call from a woman who was hiking with her son near Benson Creek Falls just west of Nanaimo. The woman had stepped over a tire-sized depression in the bedrock of a dry creek bed without noticing anything, but her son noticed that the depression had a distinctive spiral shape. Graham visited the site and confirmed that the depression was the mold of a giant ammonite. Unfortunately, the actual fossil had already washed down the creek, but he was able to make a fiberglass cast that preserved the shape of the massive shell.

The excavation proceeded, and much to everyone’s amazement the skeleton was pretty complete and nearly 40 feet long. Courtney now had its own Loch Ness Monster, but this one was real. Betsy Nicholls stepped in and wrote letters to the provincial government arguing that Courtney should be allowed to collect and display the find.

The Puntledge elasmosaur proved to be a magnet for kids. It wasn’t a dinosaur, but it was darn close, and it proved to be the catalyst for the revitalization of the Courtney Museum and for the rapid growth of an amateur group known as the Vancouver Island Paleontological Society. It turned out that there were lots of local collectors who had been finding fossils and stashing them in their basements. Now they had a place to bring their finds, and their finds attracted professional paleontologists who wrote books and papers and validated the importance of their discoveries.

We lingered in the museum for a couple of hours, chatting with the staff and looking at the fossils that had accumulated in the collections room in the basement. Not only were they housing fossils from Vancouver Island, but they were also receiving donations from around the province. With only a few professional paleontologists working in British Columbia and at the museums in Vancouver and Victoria, Courtney had become the beating fossil heart of the province.

Rosie the Walrus (Odobenus) from Qualicum in the vaults of the Canada Museum of Nature in Ottawa.

Nothing demonstrated this more than a massive ammonite in the back room of the Courtney Museum. A mining company had found the fossil near Fernie in southeast British Columbia and had searched for a museum to house it. They found Courtney. Ray and I had been hearing about a massive ammonite in the hills near Fernie, and we had hoped our travels would take us there, so we were stunned to realize that the giant ammonite had found us. We crawled over the 5-ton boulder and inspected the 6-foot Jurassic ammonite, realizing once again that the huge size and remote nature of British Columbia means that its fossil treasures largely wait to be discovered.

Betsy Nicholls herself had worked on remote British Columbian fossils. In 1992, she was alerted to a large bone exposed in a river in isolated northern British Columbia. It took her and Makoto Manabe, my graduate school buddy from Tokyo and Japan’s National Science Museum, several years to excavate what turned out to be a massive Triassic ichthyosaur that they named Shonisaurus sikanniensis. At nearly 70 feet long, it was the size of a big whale and the world’s largest ichthyosaur.

Most of the Pacific Coast north of Vancouver is not accessible by road. This becomes immediately clear if you have a window seat on the flight from Seattle to Ketchikan. The entirety of the flight is a panorama of jagged snow-capped peaks and deep green fjords. From the point where Highway 99 departs Vancouver headed toward the northeast to the spot where Highway 37 arrives in Prince Rupert, there are literally no roads that access the British Columbia coastline for 450 miles. This huge and inaccessible coast is known as the Great Bear Rainforest, and it is home to a very unusual subspecies of black bear that is totally white. Known as Kermode bear or the spirit bear, it is one of the least-known animals on the West Coast.

The people that travel this coast do so by fishing boats, tugboats, ferries, coastal freighters, private yachts, and cruise ships. In the winter of 1984, three of my friends and I found out that for only $75 Canadian, it was possible to buy a round-trip ticket with a four-person berth on a British Columbia ferry from Vancouver to Prince Rupert and then across to Queen Charlotte City on Haida Gwaii. Haida Gwaii is a remote archipelago located 50 miles off the coast of British Columbia. Home to the Haida people, it is known for its remarkable and monumental cedar sculpture, houses, and poles. I had seen historic photographs of dozens of totem poles in the village of Skidegate and more recent photographs of moss-covered totem poles at the abandoned village of Ninstints. The remarkable new building at the Museum of Anthropology at the University of British Columbia had opened in 1976 and had startled the museum world by opening all of its collections for public display. These collections contained impossibly beautiful argillite carvings from Haida Gwaii. I had also read literature from the 1800s that showed images of a diversity of Jurassic ammonites from the island. It really seemed like these remote islands were a simple way to travel back in time. I had to see this place. The price seemed too good to be true, and we couldn’t help ourselves — we booked four tickets. We left Vancouver in late December in pouring rain, and it rained steadily for the entire run to Prince Rupert. My photographs from this trip show dark, wet forests and choppy green water. In Prince Rupert, we boarded another ferry and were rolled and battered by heavy ocean swells in the overnight crossing.

The Puntledge plesiosaur in the Courtney Museum.

We had made no plans but were fortunate to rent a pickup truck and a hotel room, and we spent the next few days exploring the north island from Skidegate to Massett. We saw literally hundreds of bald eagles and deer. The resurgence of Haida art that was led by Native artists Bill Reid and Robert Davidson in the 1970s was under way, but we were disappointed to see that only one pole was standing in Skidegate. Then we learned it was impossible to get to Ninstints in the winter. It poured rain in a way that I had never experienced in Seattle, and sunrise was late and sunset was early so our days were sodden five-hour experiences. On the last day, the skies cleared and we rented a salmon trawler from a fisherman who knew of a small island full of fossils. The wind ceased and the sound was glassy calm. Huge Sitka spruce cast their reflections on the coils of bull kelp floating in the water. The island’s beaches were full of concretions and ammonites. The place was remarkable.

I didn’t know it at the time, but marine biologist Ed Ricketts, who we met in Chapter 4, collected intertidal animals on Vancouver Island in 1945 and 1946 and in Haida Gwaii in 1946. After his trip to the Sea of Cortez with Steinbeck in 1940, he had conceived a series of West Coast collecting trips that would take him as far north as the Bering Sea and allow him to describe the intertidal ecology of the entire West Coast. On Vancouver Island, he spent his efforts on the west coast near Tofino, and in Haida Gwaii he collected along the north coast near Masset. These travels, and Rickett’s relationship with John Steinbeck and also mythologist Joseph Campbell, are beautifully described in Eric Tamm’s book, Beyond the Outer Shores. Ricketts considered Haida Gwaii, then known as the Queen Charlotte Islands, to be the Galapagos of the north, and we can only wonder what would have happened to our view of this remote place if he had lived to finish his book about them. Ricketts was only weeks away from departing for Haida Gwaii with John Steinbeck in 1948 when he was hit and killed by the train on Cannery Row.

Jurassic ammonite from Haida Gwaii.

The book that did get written about Haida Gwaii is John Vaillant’s The Golden Spruce. This book tells the story of Haida people, of the endless forests of the Great Bear Rainforest, of European contact, and of the logging that has decimated the forests of Canada’s coast.

Both Vancouver Island and Haida Gwaii are part of a landmass known as Wrangellia that assembled somewhere out in the Pacific before sliding into place and docking up against North America about 200 million years ago. These exotic islands are exotic for a reason. They are not of this continent. But after they arrived, they became part of the West Coast and part of its story. Over time, the plants, animals, and people of North America (many of them originally from Asia) populated the islands and created ecosystems and cultures. The Haida creation story, so eloquently rendered in Bill Reid’s giant yellow cedar sculpture, tells of the raven discovering the first humans living in clamshells along the beaches of Haida Gwaii.

Back on the mainland, in the southeastern corner of British Columbia, is a fossil site known as the Burgess Shale. It is the most famous example of the Cambrian Explosion, a time more than 500 million years ago when many of the world’s first marine organisms (including the ancestors of clams) appeared on earth. That is a place that tells the paleontologist’s creation story.