In the new culture movement in early twentieth-century China, key intellectual figures such as Lu Xun, Chen Duxiu, and Hu Shi rejected traditional Confucian culture and argued that rejuvenation of the modern Chinese nation must be based on the construction of a new culture. This new culture would promote a new philosophy of life with strong beliefs in individualism, freedom, science, technology, and democracy. This New Culture movement remains one of the most significant defining moments of modern Chinese history.1

Many other cultural movements have since appeared, none as influential as the New Culture movement. It thus came as a surprise when I learned in conversations with a former Red Guard and sent-down youth that during their years of rustication, she and her friends were involved in what they called a second New Culture movement.2 In my research I had often read about the sort of underground cultural activities among sent-down youth, but had not associated these activities with another new culture movement, particularly one that claimed to be the successor of the New Culture movement. But the analogy made sense to me. Despite the differences in the quality and quantity of the output of the two new culture movements, they share one key similarity, namely, the theme of a growing new consciousness. This new consciousness is an important component in the mental journey of the Red Guard generation. This chapter traces the development of this new consciousness through a study of this “second new culture movement.”

An Underground Cultural Movement

Unlike the first New Culture movement, this second one had a surreptitious character. It consisted of an amalgam of semiopen, underground, or surreptitious cultural activities and it was primarily a phenomenon involving the Red Guard generation.3 On the production side, there was the writing of letters, diaries, poems, songs, political essays, short stories, and novels. The output of letters and diaries was presumably large, because diary writing and letter writing were prevalent.4 Letters were not only written for private communication but also for sharing ideas. Some letters went into underground circulation because they contained serious discussions about social and political issues.5 The output of poetry was similarly large. Exchanging a self-composed poem (in classical or modern free verse) was common among sent-down youth. Many such poems were a way of expressing personal connection and friendship. However, fine poetry did emerge, as evidenced by the volumes of “misty poetry” (meng long shi) later published in the post-Mao era.6 The most influential poets and artists who began to publish after the Cultural Revolution were already honing their skills in the early 1970s.7 There were fewer stories, songs, and political essays, though they were equally widely circulated. Dozens of “sent-down youth songs” (zhiqing ge qu), for instance, were in underground circulation, the best-known of which was “A song of sent-down youth from Nanjing.”8

The reception-side story was even more fascinating, because it was more multifaceted and involved many more people. It was about the reading, copying, and circulation of forbidden books and unpublished manuscripts, about singing, storytelling, and listening to foreign radio stations. The most popular hand-copied manuscripts were unpublished works, which Perry Link refers to as hand-copied entertainment fiction.9 Link classifies them into six story types, namely, detective stories, antispy stories, modern historical romance, modern knight errant stories, triangular love stories, and pornographic stories. They are estimated at over a hundred in number, but only fewer than half are extant today. Their authorship is usually unknown, though some of them were likely to be written by Red Guards or sent-down youth.10

Unpublished manuscripts were only a small part of the reading materials. The majority were published works. Because of the scarcity of books, people would read anything they could lay their hands on. Works of Mao, Marx, Engels, Lenin, and Stalin were legitimate readings and available in book stores. Other books they read were published before the Cultural Revolution but were then banned. These included masterpieces of Chinese and Western literature, modernist Western literature, works about Soviet revisionism, and the international communist movement. Some of these were internal publications.11

To help cadres understand the Chinese Communist Party’s critique of Soviet revisionism and the alleged decadence of Western modernist thought, the propaganda department of the CCP inaugurated a publishing project in 1962. Works of Western modernist literature and Soviet revisionism were selected, translated, and published as internal materials for criticism. Their readership was limited to high-ranking party cadres. By 1965, over one thousand titles had been published, but many titles had a print run of only about nine hundred.12 Literary titles were published with a uniform yellow cover, and nonfiction works were published with a gray cover. In the wake of the Red Guard movement, these yellow-cover (huang pi shu) and gray-cover books (hui pi shu) became popular readings among young people. The following is a list of sample titles with the date of the publication of the Chinese edition in brackets.

The Stranger by Albert Camus (December 1961)

Waiting for Godot by Samuel Beckett (July 1965)

On the Road by Jack Kerouac (September 1963)

Look Back in Anger by John Osborne (July 1965)

The Catcher in the Rye by J. D. Salinger (December 1962)

Nausea by Jean-Paul Sartre (April 1965)

One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich and The Gulag Archipelago by Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn (February 1963)

Men, Years, Life by Ilya Ehrenburg (3 vols., 1962–1964)

The Thaw by Ilya Ehrenburg (1963)

Khrushchevism by Theja Gunawardhana (November 1963)

The Revolution Betrayed by Leon Trotsky (December 1963)

The New Class: An Analysis of the Communist System by Milovan Ðilas (February 1963)

The forbidden books circulated among young people thus included political dissent, critique of socialism, and the international communist movement, as well as works of world literature. Circulating and reading these titles entailed varying degrees of personal risks, from public humiliation to imprisonment. Some authors were subject to political persecution. Ren Yi was arrested on February 19, 1970, and sentenced to ten years in prison under the charge that he had written a “counterrevolutionary” song.13 Zhang Yang, the author of the novel The Second Handshake, also suffered from persecution. For these reasons I consider such cultural activities to be manifestations of an amorphous underground cultural movement.

Transgression, Self-Cultivation, and Desacralization

Several scholars have studied the underground cultural movement in the Cultural Revolution. Yang Jian’s history of underground literature is among the earliest and most systematic treatment of the literary products of the period.14 Yin Hongbiao’s book provides a comprehensive history of what he calls “trends of thought” among youth, from the Red Guard movement through the April Fifth movement.15 However, these two important works focus on the contents of the cultural products created by the “elites” of this generation. My interest differs in two ways. First, I explore the meaning of cultural activities for the Red Guard generation in the decade after the Red Guard movement. Here my focus is less on the contents of culture and more on culture as a social activity. I argue that from this perspective the meaning of the underground cultural movement was in transgression and self-cultivation. Second, I examine the relationship of this underground culture to the “high” political culture of the Red Guard period. I argue that the underground culture desacralized the revolutionary culture of the earlier period and produced a new sense of self and society.

A distinct feature of the underground cultural movement was not organized activism, but transgressive communication. Copying, borrowing, and returning a book; writing, reading, singing, storytelling—these were all acts of communication, discursive or nondiscursive. In form or content they deviated from the social norms and political ideology of the time and thus had a transgressive character. They were transgressive not in the sense of the reversal of the high and the low or of the dominant and the subordinate, as argued in the works of Mikhail Bakhtin, Peter Stallybrass, and others.16 Nor was it exactly the same as the notion of the weapons of the weak in James Scott’s work.17 Transgressive communication refers to communicative acts that occur on the margins of power. These acts may or may not be intended as deliberate transgressions upon power. Often they are not intended as such. Transgressive practices may have subversive effects, but usually slowly and accumulatively. They may or may not express dissension, though they often deviate from the orthodox and the mainstream. Their transgressive character is less about engagement or confrontations with power and more about disengagement and distancing from power. There is a hidden pleasure and thrill to transgressive practices. In this sense, transgressive practices were the extraordinary in the ordinary routines of daily labor. As I will show, part of the attraction of underground culture for youth in the Cultural Revolution derived from the pleasures and risks of transgression.

Cultural practices, transgressive or not, were technologies of the self and self-cultivation. Writing diaries, reading books, singing songs may be about self-improvement, self-planning, and self-entertainment. After universities and colleges were reopened in 1972 to admit students from among workers, peasants, and soldiers, sent-down youth began to entertain hopes of going on to college, and many of them spent their leisure time studying math, English, philosophy, literature, and other subjects. Despite all the fierce attacks on culture in the Red Guard movement, culture retained its attraction and prestige among the youth. In fact, the revolution against culture had in all likelihood intensified rather than weakened the appeal of culture, and the underground cultural movement was merely a sign of the resurgence of culture’s undying status and appeal in Chinese society.

Yet the “new” culture that appeared and circulated among sent-down youth was radically different from the revolutionary culture that led to the violent performances of Red Guard factionalism. Hence its unofficial and underground character; yet its widespread circulation underground ultimately eroded the sacred aura of revolutionary culture. New understandings of self and society emerged through this process.

In the rest of this chapter, I will analyze the many ways of producing, accessing, and consuming underground culture among sent-down youth. The chapter ends with an analysis of the contents of the cultural products and the new ideas they expressed.

Letter Writing

The production and reception of culture among sent-down youth can be distinguished only loosely. In many cases, the cultural activities combined production and consumption. Writing a letter to a friend was an act of production, but the letter writer expected a reply and was thus also a would-be reader. The act of note-taking, a common practice among youth at that time, was an act of reading as well as producing something new. The product could be a collection of quotations and sayings, like the commonplace books popular in early modern Europe, which could then be shared with friends.

Letters were a dear part in the lives of sent-down youth. A letter dated April 18, 1971, has these lines: “In the boring and monotonous days of rural life, it is always a delight to get a letter from a friend.”18 A former sent-down youth writes that in the villages “letter-writing became an important matter in our lives. When we were lonely, hopeless, sad, and homesick, we relied on letters for mutual care, mutual comfort, and mutual encouragement.”19 The poet Shu Ting recalls that “writing and reading letters was an important part of the lives of educated youth and my greatest joy.”20

Letters were written to families, lovers, friends, and classmates. They linked up those scattered in isolated rural areas into friendship circles. A collection of 124 letters written between 1966 and 1977 shows that the letters were sent to or from almost all the provinces in mainland China, weaving together a web of connections from places such as Shaanxi, Inner Mongolia, Yunnan, Sichuan to Heilongjiang, Beijing, and Shanghai.21

Letter writing was not only a means of keeping in touch with the outside world but also of sharing ideas. Some letters may run as long as ten or more pages in which their authors would engage in serious debates about practical and political issues. For example, among the most famous letters were two exchanged between Huang Yiding and Liu Ning in 1975. Huang and Liu had been classmates. They had both left Beijing for Heilongjiang as sent-down youth in 1969. In 1975 Huang moved back to Beijing. In a letter to Liu, Huang advised Liu also to return to Beijing. He wrote: “My life at home was OK. Every day, I read, go out in the street, do grocery shopping, clean the house, do the laundry. I’ve changed. I’ve changed from a farmer to a loafer, from a Marxist to a bourgeois liberal. I have no clear goal now. I want to stay away from politics and study technology. However, I know Beijing is a big world. My greatest wish is to study all the ‘secrets’ of this world, to understand its general conditions and the various types of human beings in this society.”22 In his reply Liu chided his friend for having abandoned the revolutionary ideals and dreams they used to share. He criticized his down-to-earth practicality and bourgeois liberalism. And he expressed his own wish to continue to pursue his revolutionary ideals as an educated youth. This debate reflected the dilemmas of many young people at the time. Several months later, the two letters were published in Beijing Daily. The newspaper editors, however, used Huang’s letter as a negative example and added comments in praise of Liu’s attitude toward rustication.

Only rarely did a letter get published in a newspaper, however, and if it did, it would be surely because it served official political purposes. Letters by sent-down youth were normally written to share private feelings, thoughts, and the details of everyday life. I examined 162 letters published in three collections.23 Of these, 98 were written to friends or classmates, 47 to family members, and 17 were love letters. The expressions of personal feelings and thoughts were a remarkable feature of these letters. Generally, letters to family members—parents and siblings—included more details about daily life and activities, whereas letters between friends and classmates featured more discussions of personal thoughts and feelings. Here is an excerpt from a letter addressed by a daughter to her parents, dated September 1, 1968: “I bought 1.5 jin of honey. It is delicious. I plan to have one jin of honey each month. It cost one yuan a jin. There is no fish here, probably because the Russians are making trouble. There are no eggs to eat either.”24

An excerpt of a letter from a son to his mother and brothers, dated July 4, 1969: “We start working in the field at 8 in the morning and stop at 12:30. Then we work from 2 PM to 6 PM. There is a short break in the middle of the day. In fact, we now start working after 9 in the morning, and do not start working in the afternoon until after 3. . . . We have three meals a day. There is not quite enough to eat. The toughest part is that we are going without vegetables. It has been like this since the 28th day of last month.”25

Finally, here is an excerpt of a letter addressed to a friend, dated March 15, 1969:

You raised many questions in your letter. This means you are concerned with these questions and you want to find answers to them. That is very good. Only those who are good for nothing are not concerned about these issues. However, some of the questions you raised should not have been raised. I am being frank because I know you will listen to me. For example, questions concerning the future and methods of the Chinese revolution and the directions and methods of agricultural reform. Also, the question about what the main problems of the Chinese revolution are. In my view, these questions have been resolved. There is no need for further discussion. . . . In my view, discussions are necessary, but they should be more about practical issues. Then we can go deeper from there step by step.26

This letter is a fascinating sample of the mental world of the sent-down generation in a moment of transition. Its addressee had apparently posed “big questions” such as the future of the Chinese revolution, a habit among youth in the Red Guard period. Yet the letter writer did not think they should ponder such “big questions” any more, but rather be concerned “more about practical issues.”

Access to Books

Forbidden books were hard to come by. The main channels of book distribution in the Cultural Revolution were state-owned bookstores, uniformly called the New China Bookstore (xin hua shu dian). The number of New China Bookstore branches grew slowly up to the eve of the Cultural Revolution, from 3,584 in 1957, to 3,791 in 1963, and 4,076 in May 1966.27 After the CR started, some bookstores were closed, and many stores locked away most of their books. The Central Branch of the New China Bookstore was shut down in 1969 (to be reopened in March 1973), and all its cadres sent to cadre schools or villages.28 Nationwide, 576 million copies of books were sealed off in bookstores. Bookstores in Beijing alone locked away 8 million copies of 6,870 titles.29 In Shanghai the biggest bookstore on Nanjing Donglu had 1,792 titles in social science in early 1966. After the CR started, only 200 titles were for sale.30

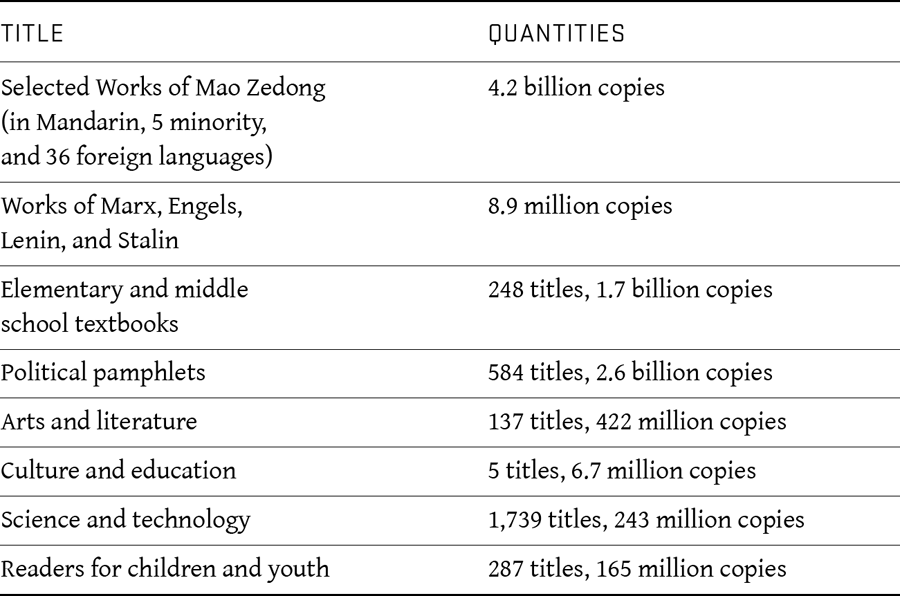

Books available in bookstores mainly consisted of the selected works of Mao Zedong, Marx, Engels, Lenin, and Stalin, political pamphlets of newspaper editorials and articles published for all kinds of political campaigns, technical and agricultural manuals, and children’s picture books, mostly about the eight model Peking operas. Table 5.1 shows the types and numbers of books published in China from 1966 to 1970.

Table 5.1 Types of Books Published in China, 1966–1970

Source: Compiled from Dang Dai Zhongguo De Chu Ban Shi Ye, 1:76-78.

Mao’s works flooded the nation. A village in Anhui had 20 households and 97 people, but these 20 households had 21 sets of Mao’s Selected Works, 100 copies of Mao Quotations, and 1,003 Mao portraits.31 When Nixon visited China in 1972, Zhou Enlai wanted to present him with a set of the complete works of Lu Xun. Yet the set that was published in the late 1950s had been banned and was considered inappropriate as a gift. Zhou ended up giving Nixon a set from the Lu Xun Museum that was published in 1938.32

The Cultural Revolution thus changed the supply-demand conditions of the book market. Books with strong ideological contents, as shown in table 5.1, flooded the market. Works of foreign and classical Chinese literature were scarce, because most of them were banned. And many libraries were closed. It was under these conditions that youth resorted to transgressive acts to obtain books to read. Two main forms were stealing and borrowing.33

Stealing Books

One way of obtaining books among the young people was stealing. A favorite place to steal books from was libraries, many of which were closed down, but there were other unexpected locations as well. According to one memoir,34 three friends in Shaanxi once saw a carriage of books being taken to paper mills for pulping. They wanted to buy a few, but the driver turned them away. They followed the carriage to the paper mill and went back at night to steal the books. In another case, two sent-down youth on a state farm learned that there were some books locked away at the headquarters of their regiment. They traveled many miles there and stole several bags.35

Stealing books had its risks. People might steal a few at a time or at most a few bags. In one case in the early 1970s, four young men systematically stole over three thousand volumes of foreign literature, books for internal circulation (nei bu fa xing), and works of theory and philosophy. When they were arrested, the charge against them was not theft, but involvement in a nationwide counterrevolutionary clique of reading groups. They were imprisoned for four years.36

In another case, a young student out to steal books from his school library almost lost his life: “The books that were not destroyed in our school were kept in a room on the fourth floor. Everyone knew that since most books had been burned, the remainder wouldn’t last either. Some students who loved books were unwilling to give up. They wanted to steal the books. Risking his life, one student . . . climbed out of the window of another room on the fourth floor, and stepping on the thin edge of the wall, inched toward the room where the books were kept. He fell from the fourth floor . . . but luckily didn’t die.”37

Eager readers sometimes got unexpected help from librarians. Once, during his vacation, a young man visited his sister back in the city, who introduced him to a librarian who gave him the key to a sealed library. Thus he spent his vacation reading in the library. There were a few favorite books that he really wanted to take away with him, but he decided not to steal them because it would be a betrayal of his sister’s friend’s trust. On the day when he was leaving town, the librarian came to see him off and offered him a copy of classical Chinese poetry, one of his favorites from the collection. Seeing him hesitate, she said, “Just take it. Many books were burned anyway. It is better to take it away than have it burned.”38

This example shows a social dimension of book stealing that was common in these transgressive practices. The act of transgression was made possible by trust between friends and acquaintances. We will see this pattern repeated again and again in other transgressive acts.

Borrowing Books

Another common way of obtaining books was borrowing from friends and acquaintances. Book-borrowing had a culture of its own. People were willing to make great efforts to borrow books. The following account by a young man sent to a village offers an example: “To borrow books, I had to cover long distances, from the near to the far. I would start with the near, walking for three or five kilometers, and borrow [from people] in the few nearby villages. . . . Then I reached out to the commune . . . walking for twenty or thirty kilometers. After that, with horizontal ties increasing among educated youth, I would borrow books from youth in other communes. In that case I had to walk very long distances.”39

Borrowers were usually bound by honor to return books promptly. Because books often passed through many hands, however, they did get lost often, but this did not mean it would cause friendship to break up. “I never heard of people breaking up with their friends because of not returning borrowed books,” one person recalled, “Those who wanted to monopolize their own books would probably be viewed as sinful.”40

In explaining why he decided not to return a favorite book to a friend, this person conveys vividly the passion for books that was common among these youth:

Many popular books passed through my hand at that time, including those yellow-cover and gray-cover books that were hard to come by. I never thought of keeping one for myself. I kept my innocence until I came across the Soviet writer [Konstantin Georgiyevich] Paustovsky. The first time I read the selected works of Paustovsky, I did it in a hurry as I was being rushed. I didn’t know why I was touched so strongly [by his works]. . . . The deep and melancholy beauty that was unique to Russian culture flowed through my heart slowly. I felt as if my soul was melted and purified by it. For days after I returned the book, I experienced the pain of lost love. I asked all around to find the whereabouts of that book, but never heard of it again. One day about a year later, I accidentally saw the book in a pile of books at a friend’s home. . . . Grabbing it, I said to my friend casually, “Let me take a look at this book.” My friend took a glance and replied just as casually, “Sure.” . . . From the moment when I got hold of the book again, I decided not to give it up anymore. . . . After a long time, the owner of the book casually asked me about the book. I replied just as casually that I had loaned it to somebody and didn’t know where it was. . . . I did loan it to my friends many times . . . but each time I repeatedly warned them to return it in time, and they had kept their promise. Another year passed. Then one day . . . the book’s owner came to visit me. I had already considered that book as my own . . . and did not think of hiding it away from the visitor. As we were chatting, my friend saw the book and ask casually: “Is that mine?” I was completely taken off guard and realized my carelessness with frustration and embarrassment. It could not be helped. I put on an air of casual indifference and said, “It was just returned to me. Take it back.” That moment, I felt like a knife had been struck into my heart.41

Among such passionate book lovers, it is not surprising that books became an important medium of social exchange. On the one hand, sharing forbidden books became a means of social bonding. It relied on trust and it strengthened friendship, as we see from the foregoing story. Forbidden books gathered friends around them, which at least partly explained the rise of underground salons in cities and study groups in villages.42 On the other hand, however, ownership of and knowledge about forbidden books became status symbols in underground cultural circles. Those with access to forbidden books gained an advantage over those without. They were more likely to learn new ideas. The first and most important group of poets to emerge out of the CR began to publish poetry with a strong Western modernist flavor after the Cultural Revolution because they were mostly from elite families in Beijing with access to internal publications.43 Thus they had access to and read works like Catcher in the Rye, On the Road, and The Stranger in the early 1970s, while experimenting with new poetic techniques. In the same period, there was an underground group in Yunnan Province whose members were also writing poems. Yet their works lacked the modernist flavor because they had no access to masterpieces of Western modernism.

Reading

Reading practices varied with location and context. Compared with urban life, overshadowed by a social control system built on neighborhood committees and work units, life in the villages was relatively free of outside interference. In some regions, peasants were not at all interested in Cultural Revolution politics or class struggle.44 The relative freedom of rural life gave sent-down youth the space and time to pursue their own interests, such as reading forbidden books:

“Reading forbidden books on a snowy night behind closed doors”—that was one of the ultimate pleasures of life for the ancients. For us educated youth, such pleasure was easy to come by. In the years of the Cultural Revolution, most books were banned. Fortunately, Northern Shaanxi was a place “far from where the emperor lived,” and nobody interfered with what books you read. We could openly read Fan Wenlan’s An Abridged History of China, Anna Louis Strong’s The Stalin Era, Liu Qing’s A Pioneer Story, Gunawardhana’s Khrushchevism, and whatever other books we could find. We didn’t have to worry about being criticized or having the books confiscated. Thus, although material life was extremely hard, our spiritual life turned out to be richer than in Beijing.45

Life on state farms known as “production and construction corps” was more regimented. With a paramilitary organization, and functioning like “work units,” these state farms had much tighter control over the lives of youth. They also developed systems of organized cultural activities (such as singing contests) to provide organized entertainment as a safety valve to channel unregulated energies and sentiments. As a result, the pursuit of independent intellectual activities was more difficult. Yet resistance is a creative art; it produces its own artists under different circumstances. Some young people made use of the free time after a day’s farmwork to read or write. Others read or wrote after their dorm mates went to bed. Their writings may not express direct political dissent, but may frame discontent and grievances in ironic or ambiguous terms. Thus poems and stories still circulated in intimate circles on state farms. Some of these activities were not without high costs. On a state farm in Yunnan Province, a young man accidentally overturned an oil lamp while reading a forbidden book at night. The lamp caused a big fire and killed ten people.46

Note-Taking

Note-taking and reading groups were especially important aspects of the reading experience. People had a limited amount of time to read a borrowed book, because others might be lining up for it. They would give a quick read and then go over it to find things to copy into their notebooks.

Notebooks were a common gift item for many ordinary occasions during the Cultural Revolution, just as music CDs and books are common gift items today. They were common gifts for friends, classmates, and even lovers. If it was a gift to a friend, then words of friendship would be written on the cover page. These could be a quote from Mao, a favorite aphorism, or a self-composed poem.

Notebooks were used to take notes and write diaries. They contained collections of aphorisms, poems, songs, and book excerpts. Mainly for personal use, they were also shared among friends. Lin Mang, a member of the Baiyangdian Lakes poetry circle, recalls: “We all had a pile of notebooks for copying poems. I had about four or five of them. In them there were works by educated youth or works copied from books. Duo Duo had a notebook, which was passed around quite widely. Song Haiquan had a notebook, and he kept saying that I borrowed it and never returned it. I did borrow it from him, but I thought I returned it. Perhaps he loaned it to someone else again!”47

Writing about the circulation of forbidden books, Lin continues: “These books were circulated rapidly. Usually you had one or two days to finish it. Some people took notes. Others copied entire books. When he had time, Jiang He also copied several books. These books were a great boost to the poetry-writing circles at Baiyangdian. They changed people’s way of thinking.”48

There were extreme cases of note-taking as well. On one of his overseas trips, the novelist Han Shaogong met a former sent-down youth who seemed to have become a note-taking machine. Han wrote, “Probably because he copied too many books when he was a sent-down youth, even today [late 1990s] whenever he got hold of a pen, he wanted to write something. He said that when he was a sent-down youth in Jiangxi Province, he used up close to one hundred notebooks just taking notes from books.”49

These activities of copying and note-taking were primitive forms of media. One had to use one’s hands and feet as means of communication. In these activities we see a form of writing that is truly about self-making. If one has to walk many miles to borrow a book, the meaning of the book clearly goes beyond its contents.

Singing, Storytelling, and Radio Listening

Group activities were not limited to reading. People sang forbidden songs, listened to foreign and “hostile” radio programs, and told stories in group settings. The following story is about listening to foreign radio programs in Yunnan Province:

In the 1970s we listened to foreign radio stations, called enemy radios at that time. I don’t know how common it was among sent-down youth nationwide, but it was very common in Yunnan. Yunnan had a special geography. The radio programs of the Central People’s Radio were hardly audible. Newspapers reached the mountain regions many days late. . . . So we listened to enemy radio programs, not just for political news but mainly for entertainment. I remember there was a Taiwanese radio drama series on an Australian radio station called “Small Town Story.” Because short-wave radio signals drifted around, we would line up several radio sets together . . . so that there was always one radio with clear signals. In their straw huts, young men and women huddled around and cried and cried over the stories.50

Songs were carriers of relationships. Dozens of “songs of sent-down youth” were in circulation. Although banned, these songs spread far and wide. Like folklore, they seemed to have caught on a life of their own once they were born. Ren Yi, the author of the popular “A Song of Sent-down Youth,” wrote the song in May 1969 after spending a night singing melancholy songs with his fellow sent-down youth friends. The village where he was sent down had a large farmers’ market. On market days, sent-down youth from neighboring villages would gather in his village. They were among the first to learn to sing and spread the song. After summer harvest, Ren Yi spent two months at home in Nanjing. On the ship back to the village, he was surprised to hear several young women singing the song. Pretending not to know the song, he asked them what they were singing. “Are you a zhiqing?,” one of the women asked. Upon hearing a “yes” for an answer, the woman laughed, “Then how can you not know the “Song of Sent-down Youth?”51

A woman who was sent to Beidahuang (Great Northern Wilderness), in Heilongjiang Province, recalls her singing experience: “In the barren wilderness, we loved Russian literary songs. They sang of humanity, love, nature, and more important, the fate of the exiles. . . . A helpless old horse, the driver of a horse-carriage at the edge of death on the vast grassland, the banished who persevered for the sake of their beliefs . . . these were the images that filled our hearts and our days and years.”52

Mr. Wang recalls that on one of his home visits to Beijing, he read several hand-copied entertainment stories. Back in Beidahuang, where he had been sent down on a state farm, he told these stories to his friends. The winter nights in Beidahuang were long and drab and there was little to do after dark. Thus storytelling became an entertainment, and he soon acquired something of a reputation for his tall tales. Here is how he describes the story telling atmosphere:

Seeing how sad and distressed my friends always were, I really wanted to cheer them up and give them some fun. . . . I would sit in the middle of the room, ask someone to turn off the light and light a candle to create some atmosphere. At this point, the entire room would be so quiet that you could hear a needle drop on the floor. Everyone would open their eyes wide, hold their breath, and wait for me to start. I was not in a hurry. I would have a sip of tea, slowly take a cigarette, put it under my nose to smell it, lick it from one end to the other, and casually light it. I would spin out a mouthful of smoke ever so lightly and sweetly. By now, I would have cultivated my mood well and I was ready to start. Once I started, I would talk away for two hours on end. No one would feel tired.53

Because of the covert nature of such storytelling, it could be regarded as a form of ironic and ambiguous cultural dissent. Once discovered, it could bring trouble. The aforementioned individual was chastised for telling ghost stories and disrupting production and subject to the punishment of supervised labor for a period.54

Reading Groups and Study Groups

Reading groups and study groups were informal groups or occasions for friends to get together to talk, read, and sing. Evidence from interviews and memoirs suggests these groups existed wherever there were sent-down youth. In personal correspondence, one former sent-down youth compared them to “coral reefs scattered in the tropical ocean. . . . Some were small, some were bigger, with some overlapping connections among them.”55 In one case, three friends who had been sent to a small village in Inner Mongolia formed a group to study what they thought of as “practical and useful” knowledge. One of them took note of their discussions in his diary:

Tonight, the three of us had an informal discussion in Qian’s place. We mainly discussed the nature of our study group and the study methods. We decided to have our first meeting tomorrow. Yang Ke proposed that our main goal is to study the practical problems that we come across in our daily work. . . . Qian Bingqiang suggested that we should study everything: “I don’t have a focus,” he said, “I want to study everything, find the study methods and an analytic approach, and then go on to examine one specific issue. . . .” I agree with the latter mostly, though I have some different opinions of my own. It’s true that we should study everything in the world in order to avoid limitations. However, at every stage there should be a focus. My temporary focus is philosophy. My life aim is literature.56

Another example was a poetry reading group in a village in Shanxi province. It happened that Guo Lusheng (pen named Shi Zhi, or Forefinger), one of the first and most powerful poetic voices of the Red Guard generation, had been sent down to the village in 1969. By then, he had already written his most famous poems, including one titled “This Is Beijing at 4:08,” which captures the painful emotions of young people departing Beijing for the countryside.57 One reminiscence well conveys the atmosphere of the poetry readings in the village:

The readings usually took place after supper. Guo Lusheng would stand beside the kitchen range in his worn shirt and pants. He would stand with his back against the dark night outside the window. The small oil lamp on the top of the kitchen range would cast its dim light on his slim and tall figure. . . . Guo Lusheng often selected some of his old poems to read. Sometimes he also read his new poems. Our favorite was to listen to him read the poem “This Is Beijing at 4:08.” We would ask him to read it to us again and again, because the poem presented a true picture of our life. It expressed our feelings.58

Underground cultural activities existed in both rural and urban areas. Several such underground circles existed in Beijing and Shanghai, which have sometimes been called “salons” by scholars but were not necessarily called such in the Cultural Revolution. “The name ‘salon’ is an embellishment used by people today. There was no such a thing then,” said Chen Suning. Both Chen and her husband Sun Hengzhi were of the Red Guard generation, and Sun was and is still known as the host of the famous Xiao Donglou underground salon in Shanghai. Said Sun Hengzhi, “It is just that a group of friends who shared common interests would get together to talk. Some wild talk.” Chen added: “Mainly because at that time, during off-season, sent-down youth in various places would return to the cities. With nothing to do back in the cities, would they get stuck at home? They would naturally gather together to talk about books they had recently read, to share their personal thoughts, and to exchange news and information they had heard of.”59 Another sent-down youth, Ji Liqun, recalls similar gatherings during their holiday trips back to the cities: “Every year, around the lunar New Year, many of us returned to Beijing for a short period. During this period, we held social gatherings, and one salon after another was formed among sent-down youth. Through letters from distant places, ideas and thoughts were exchanged among sent-down youth. Through visiting and social gatherings, educated youth communicated their ideals and aspirations.”60

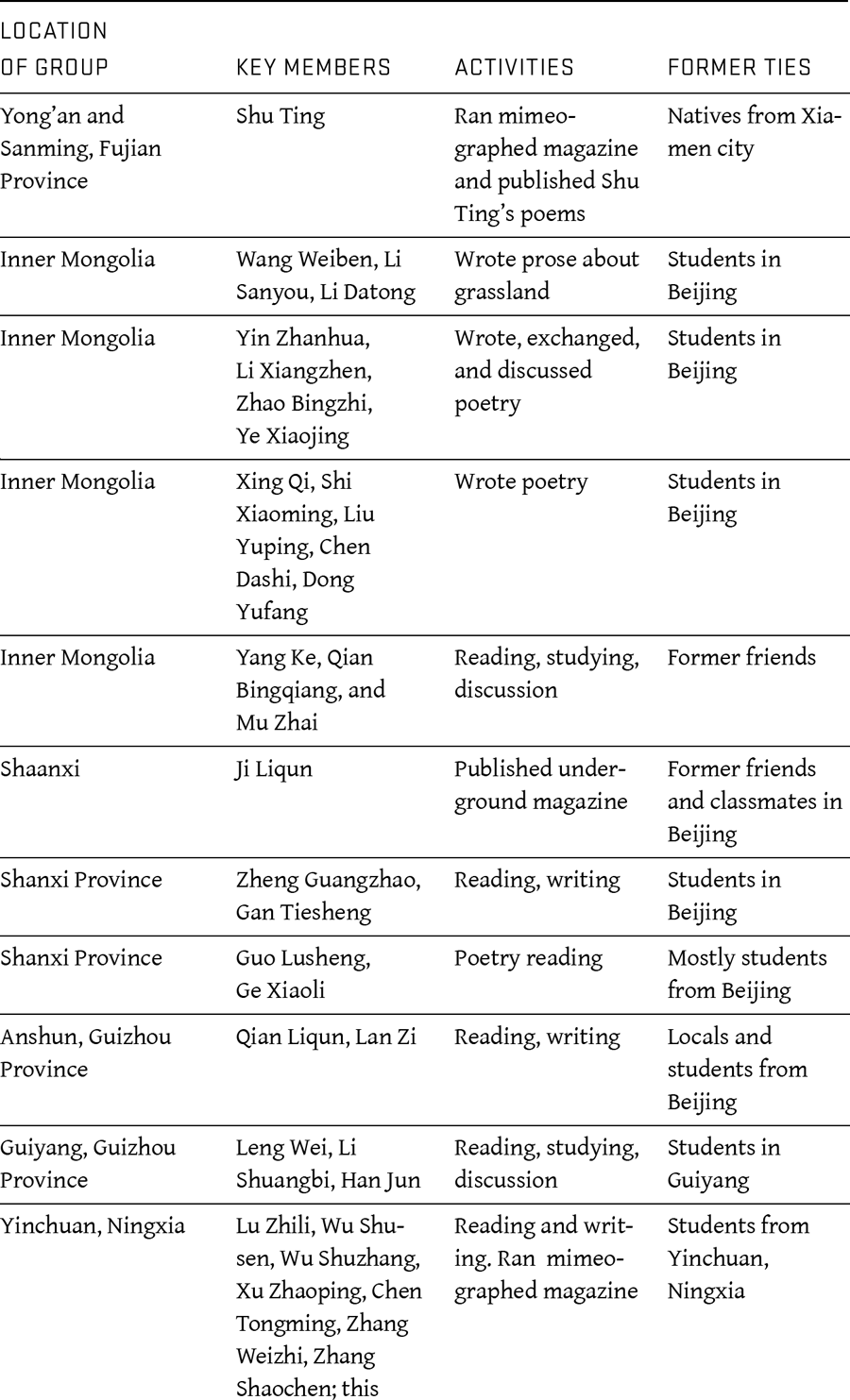

“Salon” activities had already started among Red Guards in the latter stage of the Red Guard movement, when the movement was on the decline, school was open only half-heartedly, and there was time to kill. The better-known ones include the Baiyangdian poetry circles in rural Hebei Province, the poetry circles in Inner Mongolia, groups of sent-down youth sent from Nanjing to rural Jiangsu,61 from Shanghai to Henan, from Xiamen to rural regions of Fujian Province, from Chengdu to the villages of Sichuan, and from Beijing to Jilin. Many others existed on an occasional basis. While most activities took place in the sent-down regions, they were not confined there. A few underground circles were active in Beijing, Shanghai, and Guizhou.62 Table 5.2 shows a list of such groups and their main participants.

Table 5.2 Selected Underground Cultural Groups in the Sent-Down Period

Sources: Yang, Zhongguo Zhi Qing Wen Xue Shi; Ji, “Cha Dui Sheng Ya”; Liao, Chen Lun De Sheng Dian; Mu Zhai, Huang Ruo Ge Shi—Wo De Zhiq Ing Sui Yue; Yin, Shi Zong Zhe De Zu Ji; Leng, “Leng Wei Kou Shu (III).”

As Table 5.2 shows, the participants were most likely from the same city and even the same school. Some had been friends or been involved in salon activities before being sent down. One group had been friends in the Red Guard movement. In the village, they edited and published an underground magazine with skills learned in school as Red Guards. As one of them recalls, “First we talked about it among a few friends. Then we wrote to friends in other places to ask them to contribute. After receiving their contributions, we selected some articles and poems and mimeographed them into a magazine. Then we sent the magazines to other places—educated youth in the neighboring counties, in Beidahuang, in Northern Shaanxi and Inner Mongolia, etc.”63

The best known of all were the previously mentioned poetry circles in the Baiyangdian Lakes region. These circles consisted of former schoolmates or fellow salon participants from Beijing, mostly sent down in early 1969. They included the major contributors to the future literary journal Today (Jin tian) in the Democracy Wall movement: Bei Dao, Mang Ke, Lin Mang, Duo Duo, and Jiang He. Their activities encompassed the whole range of underground activities found among sent-down youth in that period, from borrowing, copying, and circulating banned books and handwritten manuscripts to reading, writing, and discussing them. Lin Mang recalls that he often met with Duo Duo, Song Haiquan, and Gan Tiesheng in their lakeside village to talk about life experiences and poetry writing: “These kinds of conversations were frequent. Whenever we got together, these were the things we talked about. We also exchanged forbidden books.”64 According to Duo Duo’s recollections, he wrote many poems in his six-year stay in the Baiyangdian Lakes region. Each year after 1972, he produced one notebook full of poems for exchange with Mang Ke. These poems went into underground circulation in the literary salons in Beijing.65

Strategically located in rural Hebei Province near Beijing, the young people in the Baiyangdian Lakes circles were both linked to sent-down youth in other parts of the country and to groups in Beijing (such as Zhao Yifan’s salon). They functioned like communication hubs between China’s rural areas and its political and cultural center. On the one hand, these circles of cultural activists—poets, essayists, and novelists—were large enough to provide audience and critics for the authors. On the other, the communication channels helped to circulate their works to a wider audience.

Articulating A New Sense of Self and Society

What did the underground cultural movement accomplish? Certainly, in the aftermath of the Red Guard movement, the reading, copying, writing, and circulation of songs, stories, poems, books, and letters in small groups provided social support, intellectual stimulation, and psychological comfort for a generation in the doldrums. Equally important, these activities were forms of self-exploration following a movement that made the self the target of attack.

It is not hard to see why foreign works and hand-copied entertainment fiction appealed to sent-down youth. The interest in works by authors like Solzhenitsyn and Trotsky revealed a sustained engagement with problems concerning the past and future of the communist movement. The popularity of works by Beckett, Camus, Kerouac, Osborne, Salinger, and Sartre reflected the concerns of the modern individual—the antihero.

To varying degrees, sent-down youth experienced disillusionment and disenchantment. They were themselves antiheroes. That was why characters like Holden Caulfield (who was, incidentally, sixteen—roughly the same age level as sent-down youth in their first year of rustication) struck a chord in their hearts. The same concern with the conditions of the modern individual also explains the popularity of entertainment fiction. On the one hand, a sense of loss, disenchantment, banality, on the other, a passion for adventure, mystery, and romance. In the drabness of rural life, hand-copied entertainment fiction presented a world of adventure.

Poems written at the end of the Red Guard movement and at the beginning of the sent-down campaign expressed the pains of departure and separation, homesickness in the countryside, and the loss of friendship. They expressed a sense of self-doubt and a crisis of belief. Sent-down youth expressed painful disillusionment with their revolutionary ideals and the new realities of life. The moral frameworks that had supported their self-identity were on the verge of collapse. New values were in the throes of birth, but still inchoate. It was a time of death and rebirth, made tragically powerful by profound inner anxieties and contradictions. The poet Huang Xiang compared himself to a beast: “I am a wild beast hunted down / I am a captured wild beast.”66 Guo Lusheng described himself as a mad dog: “I no longer see myself as a human being, / It was as if I had turned into a mad dog.”67 In another famous poem, Guo expressed hope for the future, but in a sad and somber tone:

When spider webs relentlessly sealed my stove,

When wisps of smoke from the ashes sighed pitifully over poverty,

I stubbornly unfolded the ashes of disappointment,

And wrote in the beauty of snowflakes: Believe in the Future!68

In a letter to a friend dated February 18, 1972, Zhao Zhenkai, who would become known as Bei Dao, expressed the loss of belief that the future poet in him would translate into powerful poetic images. He told the friend not to belive in “noble ideals,” but to scrutinize the “base rock” upon which the ideals were built, to study the attributes of the “rock” and test its solidity. Without such scrutiny, he argued, “then you will not have that supporting point that is necessary for every aspiring person—a spirit of doubt.” He wrote that he was not all against having beliefs: “I think that some day perhaps I will have a belief too, but before I stand on it, I will study it thoroughly, just as an archaeologiest would study a rock: knocking it here and there.”69

There were cynical expressions too. An anonymous poem described how a young man who had returned to the city from the countryside rejected his political ideals and adopted what was then considered a “bourgeois” outlook. The young man in the poem said that for him life still had its “heroic style,” except that it was a different kind of grandeur. The earlier heroic style derived from a sense of revolutionary mission and, with it, asceticism and self-sacrifice. Today’s “heroic style” was about self-appreciation:

This hair of mine

Is carefully done by the best barber on Xidan Avenue.70

This cashmere scarf

Gives me a handsome look.71

And he declared that he no longer wanted a revolution, but “a worker’s wage, a peasant’s freedom, / A student’s life, a petty bourgeoisie’s ideas.”72

This was a straightforward rejection of the heroic style of revolution, the moral framework that had defined the self-identity of the generation up to the Red Guard movement. This rejection signaled the weakening of the generation’s identification with the party-state, its charismatic leaders, and its hallowed revolutionary tradition. A historically significant shift, it marked the starting point of a crisis of political confidence that would soon find its open expression in the Democracy Wall movement.73

Finally, with the old moral frameworks losing ground, new understandings of self and society surfaced. One central aspect of this new understanding was the affirmation of personal interests and the values of ordinary life that I discussed in the previous chapter. The growing concern with personal interests by no means implies that the generation had been unconcerned with personal interests before. Nevertheless, within the moral frameworks into which the generation had been socialized, the pursuits of self-interest had been condemned as morally wrong and politically reactionary. The core values had been collective goals and revolutionary causes.74

Affirmation for the values of ordinary life was evident in the diaries, letters, and poems produced by sent-down youth. Some poems contain vivid descriptions of the hardships of rural life as well as expressions of optimism, humor, love, joy, and friendship. A poem titled “Cold” describes the author’s humorous attitude toward winter life in Inner Mongolia:

It was daylight. I huddled up under the sheets.

I counted numbers to force myself to get up,

And clenched my teeth.

“Shit!”—I cursed, the boots were freezing cold.

No hurry to clean the room. Start the fire first

And warm up—cow dung was the treasure of all treasures.

An anonymous poem titled “On the Road with the Ruts of a Tractor” combines the images of labor with love:

A bright red scarf

Flutters on the road with the ruts of a tractor . . .

My girl

Is coming closer and closer.75

Drawing on their newly gained knowledge, some of the sent-down youth analyzed China’s official economic policies and political system. There were debates about how to reform agriculture as well as calls for democracy and the rule of law. In these exchanges, important ideas that were to dominate the reform era had already emerged. The now well-known essay “On Socialist Democracy and the Legal System,” produced by the Li Yizhe group, for example, called for the protection of people’s democratic rights.76 There were even discussions about whether some form of market economy might not be a feasible approach to tackling China’s agricultural problems.77 These discussions foreshadowed the agricultural policy debates in the early years of the reform.78

In time, the underground writers, poets, and other “cultural activists” would emerge aboveground throughout the 1980s to redefine China’s cultural landscape, introducing a new cultural politics that stretched all the way to the pro-democracy movement in 1989.79