Hor il dottor Nundinio dopo essersi posto in punto de la persona, rimẽato un poco la schena, poste le due mani su la tavola, riguardatosi un poco circũ circa, accomodatosi alquanto la lingua in bocca, rasserenati gl’occhi al cielo, spiccato da i’ denti un delicato risetto, et sputato una volta; comincia in questo modo.

PRUDENTIO. In hæc verba, in hosce prorupit sensus.

THEOPHILO. Intelligis domine que diximus? Et gli dimanda s’intendea la lingua Inglesa. Il Nolano rispose che non, et disse il vero.

FRULLA. Meglo per lui perche intẽderebbe piu cose dispiacevoli, et indegne: che contrarie á queste. Molto giova esser sordo per necessitá, dove la persona non sarebbe sordo per elettione. Ma facilmente mi persuaderei che lui la intenda; ma per non toglere tutte l’occasioni che se gli porgeno per la moltitudine de gli incivili rancontri, et per posser meglo philosophare circa i’ costumi di quei, che gli se fanno innanzi; finga di non intendere.

PRUDENTIO. Surdorum, alii natura, alii physico accidente, alii rationali voluntate.

THEOPHILO. Questo non v’imaginate de lui, perche benche sii appresso un anno che há pratticato in questo paese; non intende piu che due, ó tre ordinarissime paroli; le quali sá che sono salutationi, ma non gia particolarmẽte quel che voglan dire. Et di quelle se lui ne volesse proferire una; non potrebbe.

SMITHO. Che vol dire ch’há si poco pensiero d’intendere nostra lingua?

THEOPHILO. Non e’ cosa che lo costringa, ò che l’inclini á questo. perche coloro che son honorati, et gentil’huomini co li quali lui suol conversare, tutti san parlare ó Latino, ó Francese, ó Spagnolo, ó Italiano: i’ quali sapendo che la lingua Inglesa non viene in uso se non dentro quest isola, se stimarebbono salvatici, nõ sapendo altra lingua che la propria naturale.

SMITHO. Questo é vero per tutto, ch’é cosa indegna non solo ad un ben nato Inglese, ma anchora di qualsivogl’altra generatione, non saper parlare piu che d’una lingua: pure in Inghilterra (come son certo che ancho in Italia et Francia) son molti gentil’homini di questa conditione, co i’ quali, chi non há la lingua del paese, non può conversare, senza quella angoscia che sente un che si fà, et á cui é fatto interpretare.

THEOPHILO. E’ vero che anchora son molti che non son gentil’homini d’altro che di razza, i’ quali per piu loro, et nostro espediente, é bene, che non siano intesi, ne visti anchora.

SMITHO. Che soggionse il dott. Nundinio?

THEOPHILO. Io dumque (disse in latino) voglo interpretarvi quello che noi dicevamo, che é da credere il Copernico non esser stato d’opinione che la terra si movesse, per che questa é una cosa inconveniente et impossibile: ma che lui habbia attribuito il moto á quella piú tosto che al cielo ottavo, per la comoditá de le supputationi. Il Nolano disse che se Copernico per questa causa sola disse la terra moversi, et non anchora per quell’altra: lui ne intese poco, et non assai. Ma é certo che il Copernico la intese come la disse, et con tutto suo sforzo la provò.

SMITHO. Che vuol dir che costoro sí vanamente buttorno quella sentenza sú l’opinione di Copernico: se nõ la possono raccoglere da qualche sua propositione?

THEOPHILO. Sappi che questo dire nacque dal dottor Torquato, il quale di tutto il Copernico (benche posso credere che l’havesse tutto voltato) ne havea retenuto il nome de l’authore, del libro, del stampatore, del loco ove fu impresso, de l’anno, il numero de quinterni, et de le carte, et per non essere ignorante in gramatica, havea intesa certa Epistola superliminare attaccata non só da chi asino ignorante, et presuntuoso, il quale (come volesse iscusando favrir l’autore, o’ pur a fine che ancho in questo libro gli altri asini trovando anchora le sue lattuche, et fruticelli: havessero occasione di non partirsene á fatto deggiuni) in questo modo le avvertisce avanti che cominciano ad leggere il libro, et considerar le sue sentenze.

Non dubito che alcuni eruditi (ben disse, alchuni, de quali lui puó esser uno) essendo giá divolgata la fama de le nove suppositioni di questa opera, che vuole la terra esser mobile; et il sole starsi saldo, et fisso in mezzo del universo: non si sentano fortemente offesi; stimando che questo sia un principio per ponere in confusione l’arte liberali giá tanto bene, et in tanto tempo poste in ordine. Ma se costoro voglono meglo considerar la cosa: trovaranno che questo authore non e’ degno di riprensione, perche é proprio á gl’Astronomi raccorre diligente, et artificiosamente l’historià di moti celesti: non possendo poi per raggione alchune trovar le vere cause di quelli, gl’é lecito di fengersene, et formarsene à sua posta per principii di Geometria, mediãte i’ quali tanto per il passato, quanto per avenire si possano calculare onde non solamente non é necessario che le suppositioni siino vere, ma ne ancho verisimili. Tali denno esser stimate l’ypotesi di questo huomo, eccetto se fusse qualch’uno tanto ignorante del’Optica et Geometra, che creda che la distanza di quarãta gradi et piu, la quale acquista Venere discostandosi dal sole hor da l’una, hor da l’altra parte: sii caggionata dal movimento suo ne l’epiciclo, il che se fusse vero chi é sí cieco che non veda quel che ne seguirebbe contra ogni esperiẽza: che il diametro de la stella apparirebbe quattro volte, et il corpo de la stella piu di sedeci volte piu grande quando e’ vicinissima nel opposito de l’auge: che quando e’ lontanissima, dove se dice essere in auge. Vi sono anchora de altre suppositioni non meno inconvenienti che questa, quali non e’ necessario riferire.

(Et conclude al fine)

Lasciamoci dumque prendere il thesoro di queste suppositioni, solamente per la facilità mirabile et artificiosa del computo: per che se alchuno queste cose fente prenderá per vere; uscirá piu stolto da questa disciplina, che non v’e’ entrato.

Hor vedete che bel portinaio. considerate quanto bene v’apra la porta per farvi entrar dentro alla participation di quella honoratissima cognitione; senza la quale il saper computare et misurare et geometrare et perspettivare, non e’ altro che un passatempo da pazzi ingeniosi. Considerate come fidelmente serve al padron di casa.

Al Copernico non há bastato dire solamente che la terra si move; ma anchora protesta et cõferma quello, scrivendo al Papa, et dicendo, che le opinioni di philosofi son molto lõtane da quelle del volgo indegne d’essere seguitate, degnissime d’esser fugite, come contrarie al vero, et dirattura. et altri molti espressi inditii porge de la sua sentenza: non ostante ch’al fine par ch in certo modo vuole á comun giuditio tanto di quelli che intendeno questa philosofia, quanto de gl’altri che son puri mathematici, che se per gl’apparenti inconvenienti non piacesse tal suppositione: conviene ch’ancho á lui sii concessa liberta d’ ponere il moto de la terra per far demostrazioni piu ferme di quelle ch’han fatte gl’antichi, i quali furno liberi nel fengere tante sorte et modelli di circoli, per dimostrar gli phenomeni de gl’astri. da le quale paroli non si puó raccorre che lui dubiti di quello che sí constantemente há confessato, et provará nel primo libro sufficientemente respondendo ad alchuni argomenti di quei che stimano il contrario: dove non solo fá ufficio di mathematico che suppone: ma ancho de physico che dimostra il moto de la terra.

Ma certamẽte al Nolano poco se aggionge che il Copernico, Niceta Siracusano Pythagorico, Philolao, Hercalide di Ponto, Echfanto Pythagorico, Platone nel Timeo (benche timida, et inconstantemente per che l’havea piu per fede che per scienza) et il divino Cusano nel secondo suo libro de la dotta ignoranza, et altri in ogni modo rari soggetti, l’habbino detto insegnato et cofirmato prima: perche lui lo tiene per altri proprii et piu s’aldi principii, per i’ quali non per authoritate, ma per vivo senso et raggione, há cossi certo questo, come ogn’altra cosa che possa haver per certa.

SMITHO. Questo e’ bene; ma di gratia che argumento e’ quello che apporta questo superliminario del Copernico: perche gli pare ch’habbia piu che qualche verisimilitudine (se pur nõ e’ vero) che la stella di Venere debba haver tanta varieta di grandezza, quanta n’hà di distanza.

THEOPHILO. Questo pazzo il quale teme et ha’ zelo che alchuni impazzano con la dottrina del Copernico, non só se ad un bisogno havrebe possuto portar piu inconvenienti di quello; che per haver apportato cõ tanto sollẽnitá stima sufficiente ad dimostrar che pensar quello sií cosa da un troppo ignorante d’Optica, et Geometria. Vorrei sapere de quale Optica et Geometria, intende questa bestia, che mostra pur troppo quanto sii ignorante de la vera Optica et Geometra lui et quelli da quali have imparato.

Vorrei sapere come da la grandezza de corpi luminosi, si può inferir la raggione de la propinquitá, et lontananza di quelli? et per il contrario; come da la distanza, et propinquitá di corpi simili, si può inferire qualche proportionale varietá di grandezza? Vorrei sapere con qual principio di prospettiva ó di optica, noi da ogni varietá di diametro possiamo definitamente conchiudere la giusta distanza, ò la magior et minor differenza? Desiderarei intendere, si noi facciamo errore, che poniamo questa conclusione. Da l’apparenza de la quantitá del corpo luminoso, non possiamo inferire la veritá de la sua grandezza, ne di sua distanza; per che sicome non é medesma raggione del corpo opaco, et corpo luminoso: cossi non e’ medesma raggione d’un corpo men luminoso, et altro piu luminoso, et altro luminosissimo, accio possiamo giudicare la grandezza o’ver la distanza loro. La mole d’una testa d’huomo á due migla non si vede, quella molto piu piccola de una lucerna, ó altra cosa simile di fiamma, si vedrà senza molta differenza (se pur con differenza) discosta sessanta migla: come da Otranto di Pugla si veggono al spesso le candele d’Avellona, trà quai paesi tramezza gran tratto del mare Ionio. Ogn’uno che há senso, et raggione, sa che se le lucerne fussero di lume piu perspicuo á doppia proportione: come hora son viste ne la distanza di settanta migla, senza variar grandezza; si vedrebbono ne la distanza di cento quaranta migla, ad tripla; di ducento et diece. ad quatrupla; di ducento ottanta. medesmamente sempre giudicando ne l’altre additioni di proportioni, et gradi. perche piu presto da la qualitá et intensa virtú de la luce che da la quãtitá del corpo acceso, suole mantenersi la raggione del medesmo diametro, et mole di corpo. Volete dumque o’ saggi optici, et accorti perspettivi; che se io veggo un lume distante cento stadii haver quattro dita di diametro: sará raggione che distante cinquanta stadii debbia haverne otto: á la distanza di vinticinque, sedici: di dodici et mezzo, trenta due, et cossí va discorrendo, sin tanto che vicinissimo venghi ad essere di quella grandezza che pensate?

SMITHO. Tanto che secondo il vostro dire, benche sii falsa non però potrá essere improbata per le raggioni geometrice la opinione di Heraclito Ephesio che disse il sole essere di quella grandezza, che s’offre a’ gl’occhi: al quale sottoscrisse Epicuro come appare ne la sua epistola á Sophocle, et ne l’undecimo libro de natura (come referisce Diogene Laertio, dice che (per quanto lui puó giudicare) la grandezza del sole, de la luna, et d’altre stelle, e’ tanta, quanta á nostri sensi appare: perche (dice) se per la distanza perdessero lá grandezza, ad piu raggione perderebbono il colore: et certo (dice) non altrimente doviamo giudicar di qué lumi, che di questi che sono appresso noi.

PRUDENTIO. Illud quoque Epicureus Lucretius testatur quinto de natura libro.

Nec nimio solis maior rota, nec minor ardor

Esse potest, nostris quam sensibus esse videtur.

Nã quibus e’ spaciis cũque ignes lumina possunt

Ad iicere, et calidum membris adflare vaporem.

Illa ipsa intervalla nihil de corpore limant

Flammarũ, nihilo ad speciẽ est cõtractior ignis.

Luna quoque sive Notho fertur, sive lumine lustrans,

Sive suam proprio iactat de corpore lucẽ.

Quicquid id est nihilo fertur maiore figura.

Postræmo quoscunque vides hinc ætheris ignes,

Dum tremor est clarus, dum cernitur ardor eorũ,

Scire licet perquam pauxillo posse minores

Esse, vel exigua maiores parte parte brevique,

Quãdo quidẽ quoscunq; in terris cernimus ignes

Per parvũ quiddam interdum mutare videntur,

Alterutram in partem filum, cum longius absint.

THEOPHILO. Certo voi dite bene, che con l’ordinarie et proprie raggioni in vano verranno i’ perspettivi, et Geometri á disputar con Epicurei, non dico, gli pazzi quale e’ questo liminare del libro di Copernico: ma di quelli piú saggi anchora: et veggiamo come potrá concludere che á tanta distanza quanta e’ il diametro de l’epiciclo di Venere, si possa in ferir raggione di tanto diametro del corpo del pianeta, et altre cose simili.

Anzi voglo avertirvi d’un’altra cosa. Vedete quanto e’ grande il corpo de la terra? sapete che di quello non possiamo veder se non quanto e’ l’orizonte artificiale?

THEOPHILO. Hor credete voi che se vi fusse possibile di retirarvi fuor de l’universo globo de la terra in qualche punto de l’etherea regione (sii dove si vuole) che mai avverrebbe che la terra vi paia piu grande?

SMITHO. Penso di non, per che non e’ raggione alchuna per la quale de la mia vista la linea visuale debba esser forte piu, et allungar il semidiametro suo, che misura il diametro de l’orizonte.

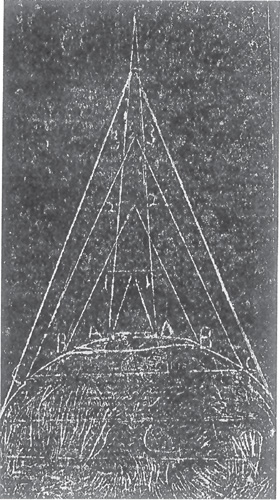

THEOPHILO. Bene giudicate. Però e’ da credere che discostandosi piu l’orizonte sempre si disminuisca. Ma con questa diminutione de l’orizonte notate che ne si viene ad aggiongere la confusa vista di quello che è oltre il già compreso orizonte, come si puó mostrare nella presente figura dove l’orizõte artificiale e’ I i. al quale risponde l’arco del globo. A. A. L’orizonte de la prima diminutione e’ 2. 2. al quale risponde l’arco del globo B.B. l’orizonte de la terza diminutione e’ 3.3. al quale risponde l’arco C.C. l’orizõte de la quarta diminutione e’ 4.4. al quale rispõde l’arco D.D. et cossi oltre attenuandosi l’orizõte, sempre crescera la cõprehensione de l’arco insino alla linea emispherica, et oltre, alla quale distanza ò circa quale posti, vedreimo la terra con quelli medesmi accidenti co i’ quali veggiamo la luna haver le parti lucide, et oscure secõdo che la sua superficie e’ aquea, et terrestre. [Figure 1]

Tanto che quanto piu se strenge l’angolo visuale, tanto la base maggiore si comprende de l’arco emispherico, et tanto anchora in minor quantitá appare l’orizonte, il qual voglamo che tutta via perseveri á chiamarsi orizonte, benche seconda la cõsuetudine habbia una sola propria significatione. Allontanandoci dumque, cresce sempre la comprehensione del’hemisphero, et il lume, il quale quanto piu il diametro si diminuisce, tanto d’avantaggio si viene ad riunire: di sorte che se noi fussemo piu discosti da la luna; le sue macchie sarrebono sempre minori, sin alla vista d’un corpo piccolo et lucido solamente.

SMITHO. Mi par haver intesa cosa non volgare, et non di poca importanza: Ma di gratia vengamo al proposito del’opinion di Heraclito, et Epicuro; la qual dite che puó star costante contra le raggioni perspettive, per il difetto de principii giá posti in questa scienza. Hor per scuoprir questi difetti, et veder qualche frutto de la vostra inventione: vorrei intendere, la risolutione di quella raggione, co la quale molto demostrativamente si prova, ch’sole, non solo é grande, ma ancho piu grande che la terra. Il principio della qual raggione, é che il corpo luminoso maggiore spargendo il suo lume in un corpo opaco minore: de l’ombra conoidale produce la base in esso corpo opaco, et il cono oltre quello ne la parte opposita, come ne la seguente figura M. corpo lucido dalla base di C. la quale é terminatá per HI, manda il cono del’ombra ad N. punto. Il corpo luminoso minore havendo formato il cono nel corpo opaco maggiore; non conoscerá determinato loco, ove raggionevolmente possa designarsi la linea de la sua base, et par che vada à formar una conoidale infinita, come quella medesma figura A. corpo lucido dal cono del ombra ch’e’ in C. corpo opaco; manda quelle due linee. C.D. C.E. le quali sempre piu et piu dilatando la ombrosa conoidale: piu tosto correno in infinito, che possino trovar la base che le termini. [Figure 2]

[Fig. 1 Diagram representing the “eye” of an observer moving into space beyond the globe of the earth. As the angle of vision decreases, larger and larger portions of the earth’s horizon become visible. © The British Library Board, C.37.c.14.(2.) p. 56.]

La conclusione di questa raggione, e’ che il sole e’ corpo piu grande che la terra, per che manda il cono de l’ombra di quella, sin appresso alla sphera di Mercurio, et non passa oltre. che se il sole fusse corpo lucido minore; bisognarebbe giudicare altrimente: onde seguitarebbe che trovandosi questo luminoso corpo ne l’hemisphero inferiore; verrebbe oscurato il nostro cielo in piu gran parte che illustrato: essendo dato o’ concesso, che tutte le stelle prendeno lume da quello.

[THEOPHILO]. Hor vedete come un corpo luminoso minore può illuminare piu dellá mitta d’un corpo opaco piu grãde. Dovete avvertire quel che veggiamo per esperienza. Posti due corpi de quali l’uno e’ opaco, et grande come A; l’altro piccolo lucido come N. se sará messo il corpo lucido nella massima [minima], et prima distanza, come e’ notato nella seguente figura, verrá ad illuminare secondo la raggione de l’arco piccolo C.D. stendendo la linea Bi. Se sará messo nella seconda distanza maggiore, verrá ad illuminare secondo la raggione del’arco maggiore EF. stendendo la linea B2. se sarà nella terza, et maggior distanza, terminará secondo la raggione del’arco piu grande GH. terminato da la linea B3. Dal che si conchiude che può avvenire che il corpo lucido B. servando il vigore di tanta lucidezza che possa penetrare tanto spacio, quanto á simile effetto si richiede, potrá, col molto discostarsi comprendere al fine arcó maggior che il semicircolo: atteso che non e’ raggione che quella lontananza ch’há ridutto a’ tale il corpo lucido che comprenda il semicircolo, non possa oltre promuoverlo à comprendere di vantaggio. Anzi vi dico de piu, che essendo ch’il corpo lucido nõ perde il suo diametro se non tardissima et difficilissimamente: et il corpo opaco (per grande che sia) facilissimamente, et improportionalmẽte il perde: [Figure 3] peró si come per progresso de distanza dalla corda minore CD. é andato á terminare la corda maggiore EF. et poi la massima GH. la quale é diametro: cossi crescendo piu et piu la distanza, terminará l’altre corde minori oltre il diametro, fin tanto ch’il corpo opaco tramezzante non impedisca la reciproca vista de gli corpi diametralmente opposti. Et la causa di questo e’ che l’impedimento che dal diametro procede: sempre con esso diametro si vá disminuendo piu et piu, quanto l’angolo B. si rende piu acuto. Et é necessario al fine che l’angolo sii fatto tanto acuto (per che nella physica divisione d’un corpo finito e’ pazzo chi crede farsi progresso in infinito, o’ l’intenda in atto o’ in potenza) che non sii piu angolo, ma una linea, per la quale dui corpi visibili opposti possono essere alla vista l’un de l’altro; senza che in punto alchuno, quel ch’e’ in mezzo, vagla impedire: essendo che questo há persa ogni proportionalitá et differenza diametrale, la quale ne i’ corpi lucidi persevera. Peró si richiede che il corpo opaco che tramezza, ritegna tanta distanza da l’un et l’altro, per quanta possa haver persa la detta proportione, et differenza del suo diametro: come si vede et e’ osservato nella terra; il cui diametro non impedisce che due stelle diametralmente opposte si veggano l’una l’altra, cossi come l’occhio senza differenza alchuna puó veder l’una et l’altra dal centro emispherico N. et dalli punti de la circonferenza A.N.O. (havendoti imaginato in tal bisogno, che la terra per il centro sii divisa in due parte uguali á fin ch’ogni linea perspettivale habbia il suo loco.) Questo si fà manifesto facilmente ne la presente figura. [Figure 4]

[Fig. 2 Diagram showing that the luminous sphere of the sun must be larger than the opaque sphere of earth because the earth produces a finite cone of shadow. © The British Library Board, C.37.c.14.(2.) p. 58.]

Dove per quella raggione che la linea A.N. essendo diametro fa l’angolo retto, ne la circonferenza; dove e’ il secondo loco, lo fá acuto: nel terzo piu acuto, bisogna ch’al fine dovenghi a’ l’acutissimo, et al fine a’ quel termine che non appaia piu angolo, ma linea; et per conseguenza e’ destrutta la relatione, et differenza del semidiamtero, et per medesma raggione, la differenza del diametro intiera AO, si destruggerá. La onde al fine e’ necessario che dui corpi piu luminosi, i’ quali non si tosto perdeno il diametro, non saranno impediti per non vedersi reciprocamente; non essendo il lor diametro svanito, come quello di non lucido ò men luminoso corpo tramezzante.

[Fig. 3 Diagram claiming to show (erroneously) how a small luminous body moving away from a large opaque sphere will illuminate it at a great distance even beyond its diameter until a point is reached where the opaque body will no longer impede the vision of another luminous body placed on the opposite side. © The British Library Board, C.37.c.14.(2.) p. 60.]

[Fig. 4 Diagram related to the previous figures showing how the eye of an observer moving away from the centre of the earth will see its diameter at an ever more acute angle until the angle becomes a straight line and the earth becomes a mere point and finally disappears. © The British Library Board, C.37.c.14.(2.) p. 62.]

Concludesi dumque che un corpo maggiore il quale e’ piu atto a’ perdere il suo diametro: benche stia per linea rettissima al mezzo, non impedirà la prospettiva di dui corpi quantosivogla minori, pur che serbino il diametro della sua visibilitá, il quale nel piu gran corpo é perso. Quá per disrozzir uno ingegno non troppo sullevato á fin che possa facilmente introdurse à comprendere la apportata raggione, et per ammollar al possibile la dura apprensione: fategli esperimentare ch’havendosi posto un stecco vicino a’ l’occhio: la sua vista sará di tutto impedita a’ veder il lume de la candela posta in certa distanza: al quale lume quanto piu si viene accostando il stecco, allontanandosi da l’occhio; tanto meno impedirà detta veduta, sin tanto che essendo si vicino, et gionto al lume, come prima giá era vicino, et gionto a’ l’occhio: non impedirá forse tanto, quanto il stecco e’ largo.

Hor giongi a’ questo che ivi rimagna il stecco, et il lume altre tanto si discoste; verra il stecco ad impedir molto meno. Cossi piu et piu aumentando l’equidistanza de l’occhio et del lume dal stecco: al fine senza sensibilitá alchuna del stecco, vedrai il lume solo. Considerato questo facilmente quantosivogla grosso intelletto potrá essere introdutto ad intendere quel che poco avanti e’ detto.

SMITHO. Mi par quanto al proposito, mi debba molto essere satisfatto: ma mi rimane anchora una confusione nella mente quanto á quel che prima dicesti; come noi alzandoci da la terra et perdendo la vista de l’orizonte di cui il diametro sempre piu et piu si vá attenuando: vedreimo questo corpo essere una stella. vorrei che à quel tanto ch’havete detto aggiongessivo qualche cosa circa questo; essendo che stimate molte essere terre simili á questa, anzi innumerabili, et mi ricordo de haver visto il Cusano di cui il gioditio só che non riprovate, il quale vuole che ancho il sole habbia parti dissimilari come la luna e la terra: per il che dice, che se attentamente fissaremo l’occhio al corpo di quello vedremo in mezzo di quel splendore piu circonferentiale che altrimente, haver notabilissima opacità.

THEOPHILO. Da lui divinamente detto, et inteso, et da voi assai lodabilmẽte applicato. Se mi recordo, io anchor poco fá dissi che (per tanto che il corpo opaco perde facilmente il diametro, il lucido difficilmente) avviene che per la lontananza s’annulla et svanisce l’apperenza del’ oscuro; et quella del illuminato diaphano ò d’altra maniera lucido, si vá come ad unire; et di quelle parti lucide disperse si forma una visibile continua luce, peró se la luna fusse piú lontana, non eclissarebbe il sole et facilmente potrà ogni huomo che sa considerare in queste cose, che quella piú lontana sarebbe ancho piú luminosa: nella quale se noi fussemo, non sarrebe piú luminosa a gl’occhi nostri: come essendo in questa terra, non veggiamo quel suo lume che porge à quei che sono ne la luna, il quale forse è maggior di quello che lei ne rende per i’ raggi del sole nel suo liquido cristallo diffusi. Della luce particolare del sole non sò per il presente se si debba giudicar secondo il medesmo modo, o’ altro. Hor vedete fin quanto siamo trascorsi da quella occasione. mi par tempo di rivenire all’altre parti del nostro proposito.

SMITHO. Sará bene de intendere l’altre pretensioni, le quali lui há possute apportare.

THEOPHILO. Disse appresso Nundinio che non puó essere verisimile che la terra si muove, essendo quella il mezzo et centro de l’universo, al quale tocca essere fisso et costante fundamento d’ogni moto. Rispose il Nolano: che questo medesmo puó dir colui che tiene il sole essere nel mezzo del’universo, et per tãto inmobile et fisso, come intese il Copernico et altri molti che hanno donato termine circonferentiale á l’universo. di sorte che questa sua raggione (se pur e’ raggione) e’ nulla contra quelli, et suppone i’ proprii principii. E’ nulla ancho contra il Nolano il quale vuole il mondo essere infinito, et peró non esser corpo alchuno in quello al quale simplicimẽte convegna essere nel mezzo, ó nell’estremo, o’ tra qué dua termini, ma per certe relationi ad altri corpi et termini intentionalmente appresi.

SMITHO. Che vi par di questo?

THEOPHILO. Altissimamente detto. per che come di corpi naturali nessuno si e’ verificato semplicemente rotõdo, et per conseguenza haver semplicemente centro, cossi ancho de moti che noi veggiamo sensibile et physicamente ne corpi naturali, non e’ alchuno che di gran lunga non differisca dal semplicemente circulare, et regolare circa qualche centro: forzensi quantosivogla color che fingono queste borre et empiture de orbi disuguali, di diversità de diametri, et altri empiastri, et recettarii, per medicar la natura fin tanto che vengha al servitio di Maestro Aristotele, o’ d’altro, a’ conchiudere che ogni moto e’ continuo et regolare circa il centro. Ma noi che guardamo non a le ombre phantastiche: ma a’ le cose medesme. Noi che veggiamo un corpo aereo, ethereo, spirituale, liquido, capace loco di moto et di quiete, sino immenso et infinito, (il che dovamo affermare al meno perche non veggiamo fine alchuno sensibilmente, ne rationalmẽte) et sappiamo certo che essendo effetto et principiato, da una causa infinita, et principio infinito, deve secondo la capacitá sua corporale; et modo suo essere infinitamente infinito. Et son certo che non solamẽte á Nundinio, ma anchora á tutti i’ quali sono professori de l’intendere, non e’ possibile giamai di trovar raggione semiprobabile per la quale sia margine di questo universo corporale; et per conseguenza anchora li astri che nel suo spacio si contengono, siino di numero finito; et oltre essere naturalmente determinato centro et mezzo di quello.

SMITHO. Hor Nundinio aggiunse qualche cosa á questo? apporto qualche argomento, o’ verisimilitudine, per inferire che l’universo prima sii finito, Secondo che habbia la terra per suo mezzo, Terzo che questo mezzo sii in tutto et per tutto inmobile di moto locale?

THEOPHILO. Nũdinio come colui che quello che dice, lo dice per una fede et per una consuetudine; et quello che niega, lo niega per una dissuetudine et novitá, come é ordinario di qué che poco cõsiderano et non sono superiori alle proprie attioni, tanto rationali, quanto naturali, rimase stupido et attonito; come quello á cui di repente appare nuovo phantasma. Come quello poi che era alquanto piú discreto, et men borioso, et maligno ch’il suo compagno; tacque, et non aggiunse paroli ove non posseva aggiongere raggioni.

FRULLA. Non e’ cossi il dottor Torquato il quale o’ á torto o’ á raggione, o’ per Dio, o’ per il diavolo la vuol sempre combattere, quando há perso il scudo da defendersi, et la spada da offendere; dico quando non há piu risposta, ne argumento; salta ne calci de la rabbia, acuisce l’unghie de la detratione, ghigna i’ denti delle ingiurie, spalancha la gorgia de i’ clamori; á fin che non lascie dire le raggioni cõtrarie, et quelle non pervengano á l’orecchie de circostanti come hò udito dire.

SMITHO. Dumque non disse altro.

THEOPHILO. Non disse altro á questo proposito: ma entró in un’altra proposta.

Per che il Nolano per modo di passaggio disse essere terre innumerabili simile à questa: Hor il dottor Nundinio come bon disputante non havendo che cosa aggiongere al proposito, comincia á dimandar fuor di proposito, et da quel che diceamo della mobilitá o’ immobilitá di questo globo: interroga della qualitá de gl’altri globi, et vuol sapere di che materia fusser quelli corpi che son stimati di quinta essentia: d’una materia inalterabile, et incorrottibile, di cui le parti piu dense son le stelle.

FRULLA. Questa interrogatione mi par fuor di propositio, benche io non m’intendo di logica.

THEOPHILO. Il Nolano per cortesia non gli volse improperar questo: ma dopo havergli detto che gl’harebbe piaciuto che Nundinio seguitasse la materia principale, o’ che interrogasse circa quella: gli rispose che li altri globi che son terre, non sono in punto alchuno differenti da questo in specie solo in esser piu grandi et piccioli come ne le altre specie d’animali per le differenze individuali accade inequalità, ma quelle sphere che sõ foco come e’ il sole (per hora) crede che differiscono in specie come il caldo et freddo; lucido per se et lucido per altro.

SMITHO. Perche disse creder questo per hora, et non lo affirmò assolutamente?

THEOPHILO. Temendo che Nundinio lasciasse anchora la questione che novamente haveva tolta, et si afferrasse et attaccasse á questa. Lascio che essendo la terra un’animale, et per conseguenza un corpo dissimilare, non deve esser stimata un corpo freddo per alchune parti massimamente esterne e ventilate dal’aria; che per altri membri, che son gli piu di numero et di grandezza, debba esser creduta et calda et caldissima: Lascio anchora che disputando con supponere in parte i’ principii del’adversario il quale vuol essere stimato et fá professione di Peripatetico: et in un’altra parte i’ principii proprii, et gli quali non son concessi, ma provati: la terra verebbe ad esser cossi calda come il sole in qualche comparatione.

SMITHO. Come questo?

THEOPHILO. Perche (per quel che habbiamo detto) dal svanimento delle parti oscure et opache del globo, et dalla unione delle parti cristalline et lucide, si viene sempre alle reggioni piu et piu distante, á diffondersi piu et piu di lume. Hor se il lume e’ causa del calore (come con esso Aristotele, molti altri affermano i’ quali voglono che ancho la luna et altre stelle per maggior et minor participatione di luce son piu et meno calde: onde quando alchuni pianeti son chiamati freddi, voglono che se intenda per certa comparatione et rispetto,) avverrá che la terrra có gli raggi che ella manda alle lontane parti de l’etherea reggione, secondo la virtú della luce, venghi á comunicar altre tanto di virtú di calore. Ma á noi non costa che una cosa per tanto che e’ lucida, sii calda, per che veggiamo appresso di noi molte cose lucide ma non calde. Hor per tornare á Nũdinio Ecco che comincia á mostrar i’ denti, allargar le mascelle, strẽger gl’ochci, rugar le cigla, aprir le narici, et mandar un crocito di cappone per la canna del polmone; acciò che con questo riso gli circostanti stimassero che lui la intẽdeva, bene, lui havea raggione; et quell altro dicea cose ridicole.

FRULLA. Et che sia il vero; vedete come lui se ne rideva?

THEOPHILO. Questo accade á quello che dona confetti á porci. Dimandato perche ridesse? rispose che questo dire et imaginarsi che siino al[tre] terre, che habbino medesme proprietá et accidenti e’ stato tolto dalle vere narrationi di Luciano.

Rispose il Nolano che se quando Luciano disse la luna essere un’altra terra cossi habitata et colta come questa; venne á dirlo per burlarsi di qué philosophi che affermorno essere molte terre (et particolarmente la luna la cui similitudine con questo nostro globo, é tanto piú sensibile, quanto é piu vicina á noi) lui nõ hebbe raggione: ma mostró essere nella comone ignoranza, et cecitá: per che se ben consideriamo trovarremo la terra et tanti altri corpi che son chiamati astri: membri principali de l’universo; come danno la vita et nutrimento alle cose, che da quelli togleno la materia, et á medesmi la restituiscano: cossi et molto maggiormente hãno la vita in se, per la quale cõ una ordinata et natural volontá da intrinseco principio se muoveno alle cose, et per gli spacii convenienti ad essi. Et non sono altri motori estrinseci che col muovere phantastiche sphere vengano á trasportar questi corpi come inchiodati in quelle: il che se fusse vero, il moto sarrebe violẽto fuor de la natura del mobile, il motore piu imperfetto, il moto et il motore solleciti et laboriosi, et altri molti inconvenienti s’aggiongerebbeno. Consideresi dumque che come il maschio se muove alla femina, et la femina al maschio; ogni herba et animale, qual piu et qual meno espressamente si muove al suo principio vitale come al sole et altri astri: la calamita se muove al ferro, la pagla á l’ambra, et finalmente ogni cosa vá a’ trovar il simile, et fugge il contrario: tutto avviene dal sufficiẽte principio interiore per il quale naturalmẽte viene ad esagitarse, et nõ da principio esteriore come veggiamo sempre accadere á quelle cose che son mosse ò contra, ó extra la propria natura. Muovẽsi dũque la terra, et gli altri astri secõdo le proprie differenze locali dal principio intrinseco che é l’anima propria. Credete (disse Nũdinio) che sii sensitiva questa anima? Non solo sensitiva rispose il Nolano ma ancho intellettiva; non solo intellettiva come la nostra, ma forse ancho piu. Quà tacq; Nũdinio et non rise.

PRUDENTIO. Mi par che la terra essendo animata deve nõ haver piacere quãdo se gli fãno queste grotte et caverne nel dorso, come a noi viene dolor, et dispiacere quãdo ne si pianta qualche dẽte là o’ ne si fora la carne.

THEOPHILO. Nundinio non hebbe tanto del Prudẽtio che potesse stimar questo argomẽto degno di produrlo, benche gli fusse occorso, per che nõ é tanto ignorante philosofo, che non sappia che se ella há senso; nõ l’há simile al nostro, se quella há le membra; non le hà simile á le nostre; se há carne, sangue, nervi, ossa, et vene, non son simili á le nostre; se há il core non l’ha simile al nostro, cossi de tutte l’altre parti, le quali hanno proportione a gli membri de altri et altri che noi chiamiamo animali, et comunmente son stimati solo animali. Non é tãto buono Prudentio, et mal medico, che non sappia che alla gran mole de la terra, questi sono insensibilissimi accidenti, li quali à la nostra imbecillitá sono tanto sensibili. Et credo che intenda che non altrimente che ne gli’animali quali noi conoscemo per animali, le loro parti sono in continua alteratione et moto, et hanno un certo flusso, et reflusso, dentro accoglendo sempre qualche cosa dall’estrinseco, et mandando fuori qualche cosa da l’intrinseco: onde s’allungano l’unghie; se nutriscono i’ peli, le lane, et i’ capelli; se risaldano le pelle, s’induriscono i’ cuoii: cossi la terra riceve l’efflusso, et influsso delle parti, per quali molti animali (à noi manifesti per tali) ne fan vedere espressamente la loro vita: come é piu che verisimile (essendo che ogni cosa participa de vita) molti et innumerabili individui vivono nõ solamente in noi, ma in tutte le cose cõposte, et quando veggiamo alchuna cosa che se dice morire, nõ doviamo tãto credere quella morire, quãto che la si muta, et cessa quella accidẽtale cõpositione, et cõcordia, rimanẽdono, le cose che quella incorreno, sempre inmortali: piu quelle che son dette spirituali, che quelle dette corporali, et materiali come altre volte mostraremo. Hor per venire al Nolano quando vedde Nundinio tacere; per risentirse á tempo di quella derisione Nundinica, che comparava le positioni del Nolano a’ le vere narrationi di Luciano, espresse un poco di fiele et li disse: che disputando honestamente non dovea riderse, et burlarse di quello che non puó capire, che se io (disse il Nolano) non rido per le vostre phantasie: ne voi dovete per le mie sentẽze: se io cõ voi disputo con civiltá et rispetto; almẽo altre tãto dovete far voi á me, il quale vi conosco di tanto ingegno, che se io volesse defendere per veritá le dette narrationi di Luciano: non sareste sufficiente á destruggerle, et in questo modo con alquanto di colera rispose al riso: dopo haver risposto con piu raggioni alla dimanda.

Importunato Nundinio sí dal Nolano, come da gl’altri che lasciando le questioni, del perche, et come, et quale; facesse qualche argomento.

PRUDENTIO. Per quomodo, et quare; quilibet asinus novit disputare.

THEOPHILO. Al fine fé questo del quale ne son pieni tutti cartoccini, che se fusse vero la terra muoversi verso il lato che chiamiamo oriente; necessario sarrebbe che le nuvole del aria sempre apparissero discorrere verso l’occidẽte, per raggione del velocissimo et rapidissimo moto di questo, globo che in spacio di vintiquattro hore deve haver compito si gran giro. A’ questo rispose il Nolano che questo aere per il quale discorrono le nuvole et gli venti; é parte de la terra: per che sotto nome di terra vuol lui (et deve essere cossi al proposito) che se intenda tutta la machina, et tutto l’animale intiero che costa di sue parti dissimilari: onde gli fiumi gli sassi, gli mari, tutto l’aria vaporoso et turbulento il quale et rinchiuso ne gli altissimi monti, appartiene á la terra come membro di quella, o’ pur come l’aria ch’e’ nel pulmone, et altre cavitá de gl’animali per cui respirano, se dilatano le arterie, et altri effetti necessarii á la vita s’adempiscono. Le nuvole dumque da gl’accidenti che son nel corpo de la terra, si muoveno et son come nelle viscere de quella, cossi come le acqui. Questo lo intese Aristotele nel primo de la Metheora, dove dice che questo aere che é circa la terra humido et caldo per le exalationi di quella; hà sopra di se un’altro aere, il quale é caldo et secco, et ivi non si trovan nuvole: et questo aere é fuori della circonferenza de la terra, et di quella superfice che la definisce á fin che vengha ad essere perfettamente rotonda: et che la generation de venti non si fà se non nelle viscere, et luochi de la terra: però sopra gl’alti monti ne nuvole, ne venti appaiono; et ivi l’aria si muove regolatamente in circolo, come l’universo corpo: Questo forse intese Platone all’hor che disse noi habitare nelle concavitá, et parte oscure de la terra: et che quella proportione habbiamo á gl’animali che vivono sopra la terra, la quale hanno gli pesci á noi habitanti in un’humido piú grosso. Vuol dire che in certo modo questo aria vaporoso é acqua; et il puro aria che contiene piu felici animali e’ sopra la terra, dove come questo Amphitrite e’ acqua à noi, cossi questo nostro aere e’ acqua á quelli. Ecco dumque onde si puó rispondere á l’argomento referito dal Nundinio; per che cossí il mare non e’ nella superficie, ma nelle viscere de la terra, come l’epate fonte de gl’humori é [in] noi, questo aria turbolẽto nõ é fuori ma é come nel polmone de gl’animali.

SMITHO. Hor onde avviene che noi veggiamo l’emisphero intierò: essendo che habitiamo ne le viscere de la terra?

THEOPHILO. Da la mole de la terra globosa non solo nella ultima superficie, ma ancho in quelle che sono interiori, accade che alla vista de l’orizonte cossi una convessitudine doni loco á l’altra; che non può avvenire quello impedimento qual veggiamo quando trá gl’occhi nostri et una parte del cielo se interpone un monte, che per esserne vicino ne puó toglere la perfetta vista del circolo de l’orizonte. la distanza dumque di cotai monti i’ quali siegueno la convessitudine de la terra; la quale non e’ piana ma orbicolare, fá che non ne sii sensibile l’essere entro le viscere de la terra; come si può alquanto considerare nella presente figura dove la vera superficie de la terra e’ A.B.C. entro la quale superficie vi sono molte particolari del mare, et altri continenti come per essempio M. dal cui punto nõ meno veggiamo l’intiero emisphero, che dal punto A. et altri del ultima superficie. Del che la raggione e’ da dui capi, et dalla grandezza de la terra, et dalla convessitudine circunferentiale di quella per il che M punto non e’ intanto impedito che non possa vedere l’emisphero; perche gl’altissimi monti non si vengono ad interporre al punto M come la linea MB. (il che credo accaderebbe quando la superficie della terra fusse piana.) [Figure 5] ma come la linea M.C. M.D. la quale non viene á caggionar tale impedimento, come si vede in virtu de l’arco circonferentiale, et nota d’avantaggio che si come si referisce M. ad C. et M. ad D. cossi ancho K. si referisce ad M. onde non deve esser stimato favola quel che disse Platone delle grandissime concavitá et seni de la terra.

[Fig. 5 Diagram of the earth’s globe designed to show how even the highest mountains fail to impede vision of the horizon as a hemisphere. © The British Library Board, C.37.c.14.(2.) p. 75.]

SMITHO. Vorrei sapere se quelli che sono vicini á gl’altissimi monti patiscono questo impedimento?

THEOPHILO. Non, ma quei che sono vicini a mõti minori: per che non sono altissimi gli monti, se non sono medesmamẽte grandissimi in tãto, che la loro grandezza e’ insensibile alla nostra vista: di modo che vengono con quello ad cõprendere piu, et molti orizonti artificiali, ne i’ quali gl’accidenti de gl’uni non possono donar alteratione à gl’altri; però per gl’altissimi non intendiamo come l’Alpe et gli Pyrenei et simili: ma come la francia tutta ch’e’ tra dui mari settettrionale Oceano, et Australe Mediterraneo; da quai mari verso l’Alvernia sempre si vá montando, come ancho da le Alpe et gli Pireni, che son stati altre volte la testa d’un monte altissimo: la quale venendo tutta via fracassata dal tempo (che ne produce in altra parte per la vicissitudine de la rinovatione de le parti de la terra) forma tante mõtagne particolari le quale noi chiamiamo monti. Peró quanto á certa instantia che produsse Nũdinio de gli monti di Scotia, dove forse lui è stato: mostra che lui non puó capire, quello che se intende per gl’altissimi monti. per che secondo la veritá, tutta questa isola Britannia, e’ un monte che alza il capo sopra l’onde del mare Oceano, del quale monte la cima si deve comprendre nel loco piú eminente de l’Isola, la qual cima se gionge alla parte tranquilla de l’aria, viene á provare che questo sii uno di qué monti altissimi, dove é la reggione de forse piu felici animali. Alessandro Aphrodiseo raggiona del monte Olimpo, dove per esperienza delle ceneri de sacrificii, mostra la condition del monte altissimo, et de l’aria sopra i confini, et membri de la terra.

SMITHO. M’havete sufficientissamente satisfatto, et altamente aperto molti secreti de la natura, che sotto questa chiave sono ascosi. Da quel che respondete á l’argomento tolto da venti, et nuvole: si prende anchora la risposta del altro, che nel secondo libro del cielo et mondo apportò Aristotele, dove dice che sarebbe impossibile che una pietra gittata á l’alto, potesse per medesma rettitudine perpendicolare tornare al basso: ma sarrebbe necessario, che il velocissimo moto della terra se la lasciasse molto á dietro verso l’occidente. Perche essendo questa proiettione dentro la terra e’ necessario che col moto di quella si vengha á mutar ogni relatione di rettitudine et obliquitá: perche e’ differẽza tra il moto della nave, et moto de quelle cose che sono nella nave: il che se non fusse vero seguitarrebe che quando la nave corre per il mare giamai alchuno potrebbe trarre per dritto qualche cosa da un canto di quella à l’altro, et non sarebbe possibile che un potesse far un salto, et ritornare có pié onde le tolse.

[THEOPHILO] Con la terra dumque si muoveno tutte le cose che si trovano, in terra. se dũque dal loco extra la terra qualche cosa fusse gittata in terra; per il moto di quella perderebbe la rettitudine: Come appare nella nave A.B. la qual passando per il fiume, se alchuno che se ritrova ne la spõda di quello C. vẽgha à gittar per diritto un sasso verrá fallito il suo tratto per quanto cõporta la velocità del corso. Ma posto alchuno sopra l’arbore di detta nave, che corra quanto si vogla veloce; nõ fallirá punto il suo tratto: di sorte che per diritto dal punto E. che é nella cima de l’arbore o’ nella gabbia; al punto D, che é nella radice de l’arbore, o’ altra parte del ventre, et corpo di detta nave, la pietra o’ altra cosa grave gittata non vegna. Cossi se dal punto D al punto E alchuno che é dentro la nave gitta per dritto una pietra: quella per la medesma linea ritornará á basso, muovasi quantosivogla la nave, pur che non faccia de gl’inchini.

SMITHO. Dalla consideratione di questa differenza s’apre la porta á molti et importantissimi secreti di natura, et profonda philosophia: Atteso che é cosa molto frequente, et poco considerata, quanto sii differenza da quel che uno medica se stesso, et quel che vien medicato da un altro: Assai ne e’ manifesto che prendemo maggior piacere, et satisfattione se per propria mano venemo á cibarci, che se per l’altrui braccia. I fanciulli all’hor che possono adoprar gli proprii instrumẽti per prendere il cibo, non volentieri si servono de gli altrui; quasi che la natura in certo modo gli faccia apprendere, che come non v’e’ tanto piacere; non v’e’ ancho tanto profitto. I fanciullini che poppano vedete come s’appiglano con la mano á la poppa? Et io giamai per latrocinio son stato si fattamente atterrito, quanto per quello d’un domestico serivitore, per che non só che cosa di ombra, et di porten[t]o apporta seco piu un familiare che un strangiero, per che referisce come una forma di mal genio, et presagio formidabile.

THEOPHILO. Hor per tornare al proposito. [Figure 6] Se dumque saranno dui, de quali l’uno si trova dentro la nave che corre, et l’altro fuori di quella: de quali tanto l’uno quanto l’altro habbia la mano circa il medesmo punto de l’aria; et da quel medesmo loco nel medesmo tempo anchora, l’uno lascié scorrere una pietra, et l’altro un altra; senza che gli donino spinta alchuna: quella del primo senza perdere pũto, ne deviar da la sua linea, verrá al prefisso loco: et quella del secondo si trovarrá tralasciata á dietro. Il che non procede da altro, eccetto che la pietra che esce dalla mano del uno che e’ sustentato da la nave, et per consequenza si muove secondo il moto di quella, ha tal virtú impressa quale non há l’altra che procede da la mano di quello che n’e’ di fuora, benche le pietre habbino medesma gravità, medesmo aria tramezzãte, si partano (possibil sia) dal medesmo punto, et patiscano la medesma spinta.

[Fig. 6 Diagram of a moving ship in relation to a distant shore designed to illustrate Bruno’s sense of the relativity of motion on a moving earth. © The British Library Board, C.37.c.14.(2.) p. 79.]

Della qual diversitá non possiamo apportar altra raggione, eccetto che le cose che hanno fissione o’ simili appartinenze nella nave, si muoveno con quella: et la una pietra porta seco la virtu del motore, il quale si muove con la nave. l’altra di quello che non há detta participatione. Da questo manifestamente si vede che non dal termine del moto onde si parte; ne dal termine dove vá, ne dal mezzo per cui si move, prende la virtu d’andar rettamente: ma da l’efficacia de la virtu primieramente impressa, dalla quale depende la differenza tutta. Et questo mi par che basti haver considerato quanto alle proposte di Nundinio.

SMITHO. Hor domani ne revedremo per udir gli propositi che soggionse Torquato.

PRUDENTIO. Fiat.

Fine del Terzo Dialogo.

Then Dr Nundinius drew himself up to his full height, shrugged once or twice, placed his two hands on the table, took a brief look circum circa,1 rolled his tongue around in his mouth, raised his eyes serenely up to heaven, gave a delicate little laugh, spat once, and began to speak thus: …

PRUDENTIUS. In haec verba, in hosce prorupit sensus.2

THEOPHILUS. …“Intelligis domine quae diximus?”4 And he asked him if he understood English. The Nolan said no, which was the truth.

FRULLA. Better for him that he shouldn’t; for he would hear unpleasant and silly things rather than the opposite. What a great advantage it is to be deaf by necessity, when you would not be so by choice. Still, I can easily believe that he does know English really. Yet he pretends not to in order to avoid unpleasant situations arising from a multitude of uncivil encounters, or to be able to philosophize more freely concerning the customs of the people he happens to meet.

PRUDENTIUS. Surdorum, alii natura, alii physico accidente, alii rationali voluntate.5

THEOPHILUS. You shouldn’t believe that of him; because although he has been nearly a year in this country, he is unable to understand more than two or three common words. He knows these are words of greeting, but is ignorant of their meaning; so that even if he should want to proffer one of them, he would be unable to do so.

SMITHUS. How are we to interpret his lack of interest in learning our language?

THEOPHILUS. Nothing obliges him to do so, or stimulates his desire in that direction. For the cultivated people and the gentlemen, such as he is used to talking to, all know how to speak Latin, French, Spanish, or Italian. They know that English is a language limited in its use to this island, and they would not be educated if they knew no other language than their own.6

SMITHUS. That is certainly true. Any well-born Englishman – as well as someone born anywhere else – can be considered educated only if he knows how to speak more than one language. In spite of this, there are many gentlemen in England (and, if I am not mistaken, in Italy and France as well) who are in precisely that condition. If someone does not know the language of their country, he is unable to converse with them without the frustration which arises when one’s meaning has to be interpreted.7

THEOPHILUS. It is also true that many of them are gentlemen only by birth, and it is in both our interest and theirs that they should not be understood, or even encountered.

SMITHUS. What did Dr Nundinius say after that?

THEOPHILUS. “Well then,” he said in Latin, “I will interpret what we were saying for you. We were saying that Copernicus should not be considered as having said that the earth moves; for that is neither proper nor possible. Rather, he attributed movement to it, instead of to the eighth sphere of the heavens, for greater convenience in calculation.”8 The Nolan said that if this was the only reason which made Copernicus claim that the earth moves, and no other, then he had clearly failed to understand him. But without any doubt, Copernicus meant what he said, and did all he could to prove it.

SMITHUS. How are we to interpret the fact that these people judged the opinion of Copernicus so mistakenly, instead of deducing it from propositions present in the text?

THEOPHILUS. You should realize that this opinion originated with Dr Torquatus, who may have turned over all the pages of Copernicus, but who remembered only the name of the author, of the book itself, the printer, the town and year in which it was printed, and the number of pages it contained. Given that he was not ignorant of grammar, he had understood a certain preliminary letter attached to it by I know not what ignorant and presumptuous ass.9 This person claims that he is doing a favour to the author (but perhaps his real concern is to supply lettuces and berries for other asses so that they should not go hungry) by issuing a warning to the readers before they start reading the book. He exhorts them to heed what he says.

“I have no doubt that some erudite persons” (and he did well to say “some,” for he is likely to be one of them himself) “who have heard of the fame acquired by this work, will be extremely offended by what it says. For it claims that the earth moves, and that the sun stays still and fixed in the centre of the universe. The liberal arts, which have long been ordered most satisfactorily, are thrown into confusion by such a principle. However, if these people consider the question with greater attention, they will realize that this author is not at fault; because it is the task of astronomers to narrate with diligence and expertise the history of the heavenly motions. Furthermore, it is by no means his intention to find the real causes of such motions. There is thus no reason why he should not imagine them according to the principles of geometry, using such principles – both with respect to the past and with respect to the future – as a means for calculation. Accordingly, it is not necessary to believe that such suppositions are true, or even apparently so. This is the correct way to judge the hypotheses of this man. Let us consider the case of someone so ignorant of optics and geometry as to believe that the distance of forty degrees or more acquired by Venus in her movement from one side to the other of the sun is caused by her own movement within her epicycle. If that were true, who could be so blind as not to realize what would happen, in contradiction to all experience: and that is, that the star’s diameter would appear four times larger, and the body of the star more than sixteen times larger, when it is nearest – in opposition to the apogee – than when it is furthest away, and said to be in the apogee? There are a number of other suppositions, no less unlikely than these, which it is not necessary to mention here.”10

(And he concludes at the end)

“Let us then take advantage of the treasure of these suppositions only in so far as they render the art of calculation marvellously easy. For if anyone takes such fictions for real, he will leave this discipline more ignorant than when he entered it.” See what a splendid door-keeper he is! See with what a flourish he opens the door for you, so you can enter and participate in that highly valued form of knowledge which teaches you how to calculate and make measurements, how to use the rules of geometry and perspective: a form of knowledge which is nothing more than a pastime for cunning madmen. Consider how faithfully he serves the owner of the house.

For Copernicus himself judges it insufficient simply to say that the earth moves. He goes on to protest and confirm the truth of such a statement by writing to the Pope. In this letter he claims that the opinions of philosophers are very far removed from those of the vulgar herd, which is unworthy of being followed and deserves to be disregarded because it is false and unreliable.11 Furthermore, he produces evidence of many other kinds to support his thesis. It is true that in the end he seems to look for agreement both from those who believe in his philosophy and from those who are pure mathematicians. Ultimately, however, he claims that, even if his supposition should be found displeasing because of some apparent contradictions, he should nevertheless be free to assume the movement of the earth as a basis for more solid demonstrations than those put forward by the ancients. For they felt themselves free to invent all sorts and kinds of circles to explain the movements of the stars. From these words it is clear that he has no doubts of what he so consistently affirms, and which he proves well enough in the first book by replying to some objections by those who oppose him. At that point he not only acts as the mathematician who makes suppositions, but also as the physicist who demonstrates the movements of the earth.

In any case, it is of little consequence to the Nolan if Copernicus, Nicetus of Syracuse the Pythagorean, Philolaus, Heraclitus of Pontus, Ecphantus the Pythagorean, Plato in the Timaeus (although somewhat timidly and uncertainly, and more as a matter of faith than of science) as well as the divine Cusanus in the second book of his De docta ignorantia – and other extraordinary men – have already proposed and taught such a doctrine before him,12 because he makes his proposals according to his own different and more reliable criteria, not basing himself on authority, but proceeding according to the testimony of sense and reason. On these bases, he is as certain of this thing as it is possible to be of anything.13

SMITHUS. So far so good. But what about this argument proposed by Copernicus’s torch-bearer? Because it does seem likely (and perhaps even true) that the size of the star Venus should vary in proportion to its distance.14

THEOPHILUS. This madman, who fears that readers will go mad when they learn about the doctrine of Copernicus, could hardly have proposed a more unfortunate objection than that one. He thinks it is enough to express himself with much solemnity in order to prove that the people who hold that idea are fools, with no idea of optics or geometry. I would like to know where he got his crass ideas of optics and geometry from: for he is clearly completely ignorant of a true optics or a true geometry.

I would like to know how he thinks that from the size of luminous bodies it is possible to calculate their proximity or distance. Or, on the other hand, how he thinks that from the proximity or distance of such bodies, it is possible to calculate a proportional change in their size. I would like to know by what principle of perspective or optics we may infer the true distance, or its greater or lesser variation, from the variations in diameter. It would be interesting to know if we are mistaken in reaching the following conclusion – from the apparent mass of a luminous body, we are unable to infer its true size, or its distance.15 For opaque bodies and luminous bodies cannot be reasoned about in the same way when we try to calculate their true distance from us, or their size – any more than fairly luminous ones can, or extremely luminous ones. The size of a man’s head cannot be seen from two miles away; but the size of a lantern, or some such illuminated object, can be seen with very little difference (although with some difference) from a distance of sixty miles. For example, the candles of Valona can often be seen from Otranto in Puglia, although there is a large expanse of the Ionian sea between them.16 Everyone with a little common sense knows that if the light in a lantern were double as strong as another one, it would appear to be the same size 140 miles away as the other one at 70 miles. If it were treble as strong, it would appear the same at 210 miles. If it were four times as strong, at 280 miles. And so on, for increasing proportions and strengths. For it is the quality and intensity of the light rather than the quantity of illuminated body which determines the apparent diameter and size.17 And so – oh, wise opticians and qualified geometricians – why not reckon that if I see a light at a distance of 100 yards which appears to have a diameter of 4 inches, at 50 yards it will seem to be 8 inches in diameter; at 25 yards, 16 inches; at 12 and a half, 32 inches; and so on until, at a very close distance, it will seem to be its proper size?

SMITHUS. In that case, according to you, the opinion held by Heraclitus of Ephesus cannot be refuted by geometrical reasoning, even if his opinion is false: that is, that the sun is the same size as it appears to be to the sight.18 Epicurus was of the same idea, and wrote to that effect in his Letter to Sophocles and, according to Diogenes Laertius, in the eleventh book of his De natura.19 There he says that, as far as he is able to judge, “the size of the sun, of the moon and the other stars, is as it appears to our senses.” “Because,” he says, “if their size were to diminish with distance, then so would their colour.” “And it is certain,” he writes, “that we must make our judgments about those luminous bodies in the same terms as we judge such bodies down here.”

PRUDENTIUS. Illud quoque epicureus Lucretius testatur quinto “De natura” libro:20

Nor can the sun’s blazing wheel be much greater or less, than it is seen to be by our senses. For from whatsoever distances fires can throw us their light and breathe their warm heat upon our limbs, they lose nothing of the body of their flames because of the interspaces, their fire is no whit shrunken to the sight … The moon, too, whether she illumines places with a borrowed light as she moves along, or throws out her own rays from her own body, however that may be, moves on with a shape no whit greater than seems that shape, [with which we perceive her with our own eyes.]… Lastly, all the fires of heaven that you see from earth; inasmuch as all fires that we see on earth, so long as their twinkling light is clear, so long as their blaze is perceived, are seen to change their size only in some very small degree from time to time to greater or less, the further they are away: so we may know that the heavenly fires can only be a very minute degree smaller or larger by a little tiny piece.21

THEOPHILUS. You are certainly right when you say that the experts in optics and geometry will attempt in vain to dispute with the Epicureans by using the kinds of arguments they usually use. I am not referring to such fools as the person who introduces Copernicus’s book, but rather to wiser minds. For we will see how they are able to draw the conclusion that the diameter of the body of the planet, and other similar questions, can be inferred from the length of the diameter of Venus’s epicycle.

In fact, I want to warn you of something else. Do you see how big the body of the earth is? And do you know that we can only see of it that part which makes up the artificial horizon?22

THEOPHILUS. Now, do you think that, if it were possible for you to distance yourselves from this universal globe of the earth and to occupy some point in the region of the ether (any point you wish), what would happen would be that you see the earth as greater in size?

SMITHUS. I think not. Because there is no reason whatever why the line of vision from my eye should increase, and lengthen its radius, which gives the measure of the diameter of the horizon.

THEOPHILUS. A well-reasoned answer. However, it can be presumed that the horizon will diminish as it becomes more distant. You should note, though, that to this contraction of the horizon is added the confused view of what lies beyond the horizon itself, as the accompanying illustration demonstrates. In the figure, the artificial horizon is 1-1, which corresponds to the arc of the globe A-A; the horizon comprised by the first contraction is 2-2, which corresponds to the arc of the globe B-B; the horizon of the third contraction is 3-3, which corresponds to the arc C-C; the horizon of the fourth contraction is 4-4, which corresponds to the arc D-D.23 In this way, as the horizon continues to diminish, the region subtended by the arc will increase until it expands into the hemispherical line and beyond. At which distance, or thereabouts, we would see the earth with those same characteristics as we see in the moon: its parts illuminated or dark according to whether its surface is composed of water or earth.24 [Figure 1]

So much so that, the more the visual angle becomes acute, the more it comprises of the hemispherical arc of its base, while the horizon appears always to get smaller. Nevertheless, it is advisable to continue calling it a horizon, even if in ordinary usage the word has a single correctly defined meaning. So it is, then, that moving away from the earth, that part of the hemisphere comprised in our vision – as well as its illumination – increases, merging together sooner or later as the diameter diminishes. Similarly, if we were further away from the moon, its shadows would appear less clearly, until eventually it would be seen as nothing more than a small, luminous body.25

SMITHUS. What you have been saying seems to me unusual, and of considerable importance. But I would like to go back to the opinion of Heraclitus and Epicurus. You say they disagree with the arguments taken from perspective, given the faulty principles on which that science used to be founded.26 Now, in order to discover what these defects were, and to enjoy some of the conclusions of your inventive reasoning, I would like to understand the meaning of that argument which proves convincingly that the sun is not only as big as the earth, but even bigger. The argument begins with a large luminous body which sheds its light on a smaller opaque body, producing a cone-shaped shadow with its base in the opaque body itself and the cone cast in the opposite direction. As the following illustration shows, the luminous body M [A in fig.], placed opposite C, with limits at H and I [F in fig.], casts a cone of shadow to the point N [I in fig.]. A smaller luminous body, on the other hand, forms its cone with respect to the larger opaque body without any point at which it can reasonably be considered to vanish; so that it appears to form an infinite cone. This can be seen from the figure of the luminous body A [B in fig.], and from the cone of shadow which the opaque body C casts according to the lines C-D C-E, which continue to dilate in a shadowy cone until they become infinite, without finding any base in which they terminate. [Figure 2]

[Fig. 1 © The British Library Board, C.37.c.14.(2.) p. 56.]

This argument reaches the conclusion that the sun is larger than the earth because it casts its cone of shadow almost up to the sphere of Mercury, and not beyond.27 If the sun were a luminous body smaller than earth, the situation would be different. For in that case, it would follow that when the luminous body was in the Southern Hemisphere, our sky would be more dark than light – at least if we assume that the stars all receive their light from the sun.28

[THEOPHILUS]. Now I will show you how a smaller luminous body can illuminate more than half of a larger opaque body. You must pay attention to what we learn from experience. We take two bodies, of which one is opaque and large like A, and the other small and luminous like N. If the luminous body is placed at the first and minimum distance, as in the following illustration, it will illuminate the extent of the small arc C-D, which is an extension of the line B1. If it is placed at a second and greater distance, it will shed its light over the larger arc E-F, which is an extension of the line B2. If it is placed at a third and greater distance, it will illuminate the area delimited by the larger arc G-H, which is an extension of the line B3. From this it is possible to deduce that the luminous body B, by the strength of that amount of illumination which is able to penetrate the quantity of space corresponding to its effect, will be able, by moving a long way away, to cover an arc larger than the semicircle. For there is no reason why the distance which has allowed the luminous body to throw its light over the semicircle should not permit it to cover an even larger area if the distance were to be increased.29 Furthermore, the diameter of a luminous body decreases with distance only very slowly and with difficulty, while that of an opaque body (of whatever size) decreases rapidly and out of all proportion. [Figure 3] Notice that with the increase in the distance, we pass from the smaller arc CD to the larger arc EF, and then to the maximum arc GH, which is the diameter. If the distance should increase even further it will reach the other lesser arcs beyond the diameter, at least for as long as the opaque body in between does not impede the view of the bodies diametrically opposite. The reason for this is that the impediment caused by the diameter continues to diminish as the diameter continues to diminish, while the angle B becomes more and more acute. In the end it necessarily becomes so acute that (given that, in physics, division of a finite body cannot progress to infinity except for those who are mad, whether we think of it in act or in potential) it is no longer an angle but a line.30 For this reason, two visible bodies lying opposite one to another can be seen one by the other without the one in the middle impeding this in any point, given that this middle body has lost all proportion and difference of diameter which a luminous body would preserve. For this to be true, the opaque body which lies in between must be at a sufficient distance from both the other bodies to allow the proportion and difference of its diameter to disappear. This can be seen in the case of earth, whose diameter does not impede two stars lying diametrically opposite one another to be seen one from the other, in the same way as the eye, without any difference whatever, can see one or the other from the centre of the hemisphere N and from the points of the circumference ANO (supposing the earth, for convenience, divided into two equal parts through its centre so that each line is in the correct perspective).31 This is easy to see from the following figure. [Figure 4]

[Fig. 2 © The British Library Board, C.37.c.14.(2.) p. 58.]

Here the line AN, being the diameter, lies at right angles with respect to the circumference. However, in the second position the angle becomes acute, in the third position still more acute, becoming gradually more and more acute until it appears no longer as an angle but as a straight line. In consequence of this, the relation and difference with respect to the radius vanishes, and, for the same reason, its relation to the whole diameter AO reduces to nothing. For this reason, it follows necessarily that two luminous bodies, whose diameters will not disappear from view so easily, will not be impeded from viewing each other reciprocally; for their diameters will not vanish as will happen with a less luminous or opaque body lying in between them.

[Fig. 3 © The British Library Board, C.37.c.14.(2.) p. 60.]

[Fig. 4 © The British Library Board, C.37.c.14.(2.) p. 62.]

In conclusion, then, a larger body whose diameter is more prone to vanishing, provided it lies on the middle of a straight line, will not impede the view of two bodies much smaller than itself, for their diameter will not have vanished as it has in the larger body.32 Let me attempt to render more cultivated your rather simple mind, so that it may at last be capable of understanding my previous reasoning. To facilitate the laborious process of learning, you should, at this point, experiment by holding a matchstick near your eye. The sight will be totally unable to see the light of a candle placed at a certain distance. But if the stick is moved nearer to the light and further from the eye, the view will be impeded less. Finally, when the stick is nearly touching the light, it will impede its view a little less than its size would have led one to suppose.

But if the stick is now kept nearly touching the light, and the light moved the same distance away, the view of the light will be impeded much less. And as the equal distance of the eye and the light from the stick is increased, there will be no sight of the stick and only the light will be visible. By considering this phenomenon, even the most gross intellect will be initiated into an understanding of what I have just said.

SMITHUS. As far as this subject is concerned, I can only express my satisfaction. But there is still some confusion in my mind about what you said before: that is, that on rising above the earth and losing sight of the horizon, whose diameter would become gradually smaller, we would see this earthly body as if it were a star. I would like you to add something to what you said on that subject, especially in view of the fact that you think that there are many earths similar to ours, in fact innumerable other ones. I remember reading in Cusanus – whose judgment I know you are far from despising – that even the sun has dissimilar parts, like the moon and the earth. He says, in fact, that if we fix our eyes with attention on the body of the sun, we will notice that its light shines most brightly around the circumference, while in the centre there is a very marked opacity.33

THEOPHILUS. What he understood, he expressed most divinely, and you have done well to refer to it. If I remember rightly, some little time ago I said that, just as the diameter of an opaque body vanishes easily and that of a luminous one is much more persistent, similarly distance annuls the appearance of darkness. The diaphanous brightness or lucid appearance unites into a whole, and the separated luminous parts form a visible continuous light. So that if the moon were further away, it would not eclipse the sun; and everyone who knows anything of these things understands that, being further away, it would be even brighter.34 If we were in the moon, it would no longer be luminous in our eyes, any more than the earth seems luminous to us here. For we cannot see the luminosity that it irradiates to those who are in the moon. This could be greater than the rays of light it receives from the sun, and which it diffuses throughout its crystal liquid. As far as the particular question of the light of the sun is concerned, I am not sure at present if it should be judged in the same way, or differently. But look how far we have wandered from our subject. I think it is time to return to the propositions we are considering.

SMITHUS. I think we should dedicate our attention to the other arguments which were put forward by that doctor.

THEOPHILUS. Then Nundinius said that it cannot be true that the earth moves, because it is the middle and centre of the universe and has to be considered the fixed and constant foundation of all motion. The Nolan replied that the same thing could be said by those who believe that the sun is in the middle of the universe. They think that the sun is therefore immobile and fixed, as Copernicus and many others have claimed, believing that the universe has a circumference. So that this kind of reasoning (if it can be called reasoning) carries no weight with those who are of a contrary opinion; while at the same time it presupposes its own principles. Above all, it carries no weight with the Nolan, who proposes an infinite universe within which no body can be said to be in the middle, or on the edge, or between one and the other – but only to be in relation to other bodies and boundaries which are specifically defined.35

SMITHUS. What is your opinion of this?

THEOPHILUS. That he is undoubtedly right. For just as no natural body has been shown to be absolutely round, and thus to have an exact centre, so the movements of natural bodies which we see with our senses – physically – are always far from being absolutely circular and regular around some centre. Those who want to imagine fillings and wadding of irregular orbs, full of bulges and cavities, can force matters as much as they like, inventing plasters and other prescriptions in order to heal nature so that it can serve their master, Aristotle or someone else, by claiming that motions are all regular and smooth around the centre.36 But we who look at things as they are, without creating imaginary shadows: we see a single airy, ethereal, spiritual, and liquid body, a capacious place of motion and quiet which reaches out into the immensity of infinity. And we have to affirm this because we can detect no end to it, either with our senses or with our reason. Furthermore it is certain that, in so far as it is the effect of an infinite principle and cause, it has to be infinitely infinite both as a body and in its mode of being.37 I am certain that neither Nundinius, nor all the other professors of understanding, will ever be able to find even a half-probable reason why there should be a boundary to this universal body; or why, as a consequence of this, the stars contained in this space should be finite in number; or why there should be a naturally determined centre and middle of this space.

SMITHUS. So, did Nundinius add anything to this? Did he advance some proofs or probabilities to support his contention that: first of all, the universe is finite; secondly, that the earth is at the centre; thirdly, that this centre is in every possible way immobile and without local motion?

THEOPHILUS. Nundinius, like everyone who says things on the basis of faith or out of habit, or who denies things on the basis of their unusualness or novelty, appeared surprised and stunned. People normally are when they think little and are unable to rise above their own actions, whether rational or natural. He seemed like somebody who has just been surprised by a ghost. Given that he was, nevertheless, far more discreet and less argumentative and evil than his companion, he remained silent and preferred not to speak where he was unable to reason.

FRULLA. Very unlike Dr Torquatus, who, whether rightly or wrongly – in the name of God or the devil – always wants a fight. Above all, when he has lost his shield to defend himself with, and his sword for the attack: that is when he has no more replies or objections to make. Then he kicks out in anger, scratches critically, grinds his teeth insultingly, and starts to shout loudly rather than let others say something to the contrary, which might be heard by those around him. At least, that’s what people say.

SMITHUS. So he said nothing else.

THEOPHILUS. Not on that subject; but he started off on another tack.

The Nolan, to bridge the gap, said that there were innumerable earths similar to this one. Then Dr Nundinius, like a good debater who has nothing to say on the chosen matter for debate, started to ask questions off the subject. Referring back to what we had said about the mobility or immobility of this globe of ours, he asked about the quality of those other globes. He wanted to know what kind of matter makes up those bodies that are considered as made of a quintessence: that is, an unalterable and incorruptible matter which, in its densest parts, makes up the stars.38

FRULLA. That question seems to me irrelevant to the proposition, even if I don’t understand logic.39

THEOPHILUS. Out of politeness, the Nolan was loath to accuse him of impropriety. He simply told him that he would prefer it if he kept to the subject, and asked his questions about that. Then he replied that those other globes are earths, in no way different in species from this one except in so far as they are larger or smaller. As is the case with other species of living things, there are inequalities arising from individual differences. However, he thinks for the moment that those spheres which are fiery, like the sun, are specifically different in the way that heat is from cold, intrinsic light from extrinsic light.40

SMITHUS. Why did he say that he thought this now, rather than in the sense of an absolute affirmation?