With an epic history, the Houses of Parliament (home to the House of Commons and the House of Lords) remains the site of fierce verbal tussles among members of the UK’s Conservative, Labour, and smaller parties. “Westminster” (as Brits call the place) appears almost nightly on TV, as the impressive backdrop to the latest political news. A visit here gives both UK residents and foreign tourists alike a chance to tour a piece of living history and see the British government in action.

This self-guided tour assumes you’ll visit while Parliament is in session (indicated by a light above Big Ben’s clock). When Parliament is recessed, and on Saturdays year-round, visits are possible only with a reserved tour.

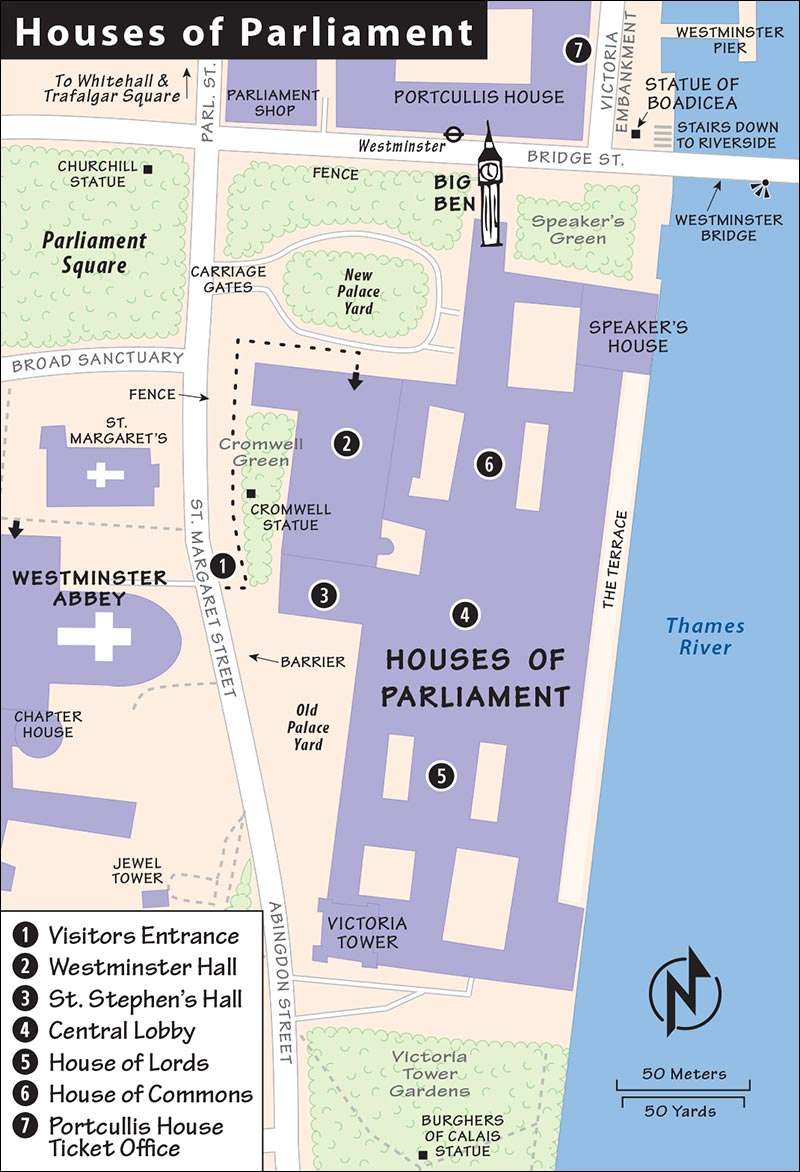

(See "Houses of Parliament" map, here .)

Cost: Free when Parliament is in session; otherwise must visit with a paid tour (see next page).

Hours: Open for nonticketed entry when Parliament is in session, generally from October to late July, Monday through Thursday (House of Commons—Mon 14:30-22:30, Tue-Wed 11:30-19:30, Thu 9:30-17:30; House of Lords—Mon-Tue 14:30-22:00, Wed 15:00-22:00, Thu 11:00-19:30; last entry depends on debates; exact schedule at www.parliament.uk ).

When to Go: Expect lines—it may take 20-30 minutes to get through security, then another 20-60 minutes to be admitted to the House chambers. You’ll have the best chance of viewing both chambers if you arrive at around 14:00. Lines are longest at the start of each day’s session, but that’s when the most fiery debates often occur (and it’s almost impossible to enter on Wed, when the prime minister normally attends). The later in the day you enter, the less crowded (and less exciting) it is. Avoid going at 16:00, when parliamentary functions make things extra busy. Visiting after 18:00 is risky, as sessions can end well before their official closing time, and visitors aren’t allowed in after the politicians call it a day.

Getting There: You can’t miss this gigantic riverside Neo-Gothic temple of government—it’s London’s most recognized symbol. The visitors entrance is around the back side (away from the river) on Cromwell Green, facing the buttresses of Westminster Abbey. Tube: Westminster.

Information: Tel. 020/7219-4272 or 020/7219-3107. See www.parliament.uk for schedule, or visit www.parliamentlive.tv for a preview. To preview a debate from home, tune into “Prime Minister’s Questions”; in the US, the 30-minute broadcast airs live Wed mornings at 7:00 (ET) on C-SPAN2, re-airing Sun at 21:00 (ET) on regular C-SPAN (www.c-span.org ).

Choosing a House: If you visit only one of the bicameral legislative bodies, choose the House of Lords. Though less important politically, the Lords meet in a more ornate room, and the wait time is shorter (likely less than 30 minutes). The House of Commons is where major policy is made, but the room is sparse, and wait times are longer (30-60 minutes or more).

Tours: On Saturdays and whenever Parliament is in recess (including much of Aug and Sept), the only way to enter is by taking a behind-the-scenes tour with either an audioguide or a live guide. The advantage is that you can linger and see a few more rooms while learning about the history of Britain’s political system (audioguide tour-£18.50, guided tour-£25.50, 1.5 hours, tours depart every 15-20 minutes on a timed-entry system, Sat 9:00-16:30 and most weekdays during recess—days and times vary, confirm schedule at www.parliament.uk ). Book ahead online or by calling 020/7219-4114 to secure a time slot (ticket office open Mon-Fri 10:00-16:00, Sat 9:00-16:30, closed Sun, Portcullis House, entrance on Victoria Embankment). Arrive at the visitors entrance on Cromwell Green 30 minutes before your tour time to clear security.

Length of This Tour: Once you clear the security rigmarole, it takes less than an hour to tour the interior and drop in—briefly—on a parliamentary session.

Photography: Allowed only in Westminster Hall and St. Stephen’s Hall.

Starring: A grand building and a gaggle of chattering parliamentarians.

The Palace of Westminster has been the center of political power in England for nearly a thousand years. Around 1050, King Edward the Confessor moved here to be next to his newly constructed “minster” (church) in the “west”—Westminster Abbey. The Palace became the monarch’s official residence, the meeting place of his noble advisors, and the supreme court of the land. In the 1500s, Henry VIII moved down the block to Whitehall Palace (now destroyed, see here ), and later monarchs chose to live at Kensington and Buckingham Palaces. But Westminster Palace remained home to the increasingly powerful advisors, or Parliament.

In 1834, a horrendous fire gutted the Palace. It was rebuilt in a retro Neo-Gothic style that recalled England’s medieval Christian roots—pointed arches, stained-glass windows, spires, and saint-like statues. At the same time, Britain was also retooling its government. Democracy was on the rise, the queen became a constitutional monarch, and Parliament emerged as the nation’s ruling body. The Palace of Westminster became a symbol—a kind of cathedral—of democracy.

(See "Houses of Parliament" map, here .)

• Enter midway along the west side of the building (across the street from Westminster Abbey), where a tourist ramp leads to the ...

Visitors Entrance

Visitors Entrance

As you enter, you’ll be asked if you want to visit the House of Commons or the House of Lords. I choose “Lords” (because the line is shorter), but it really doesn’t matter. Once inside the building, you’ll be able to see all the public spaces described in this tour as you transit to the chamber you intend to visit. If you have questions, the attendants are extremely helpful.

• At the airport-style security, collect your visitor badge. Continue past the Jubilee Café (which has live video feeds of Parliament in session), pick up helpful brochures at the information desk, and take in the cavernous...

Westminster Hall

Westminster Hall

This vast hall—covering 16,000 square feet—survived the 1834 fire, and is one of the oldest and most important buildings in England. Begun in 1097, the hall was extensively remodeled around 1390 by Richard II, who made it the grandest space in Europe. His self-supporting oak-timber roof (1397) wowed everyone. Unlike earlier roofs that spanned the hall with long beams, this “hammer-beam” roof uses short beams that jut horizontally out from the walls. They’re part of a complex system of curved braces and arches that distribute the weight of the roof outward to the walls, not downward to the floor, so there’s no need for supporting pillars. The 26 carved angels also do their part to hold up the 650-ton roof.

Stroll the room to read various plaques about the hall’s history. The King’s Table (c. 1250) originally sat on a raised platform at the south end of the hall. Here the king presided—dispensing justice, welcoming ambassadors, hosting his coronation banquet, toasting revelers.

England’s vaunted legal system was invented in this hall, as this was the major court of the land for 700 years. King Charles I was tried and sentenced to death here. Guy Fawkes was condemned for plotting to blow up the Halls of Parliament in 1605. (He’s best remembered today for the sly-smiling “Guy Fawkes mask” that has become the symbol of 21st-century anarchists.)

In more recent times, the hall has hosted the lying-in-state of Winston Churchill, G-G-G-George VI, and the Queen Mother. And in 2011, Britain’s bigwigs gathered here for a speech by Barack Obama.

• Walking through the hall and up the stairs, you’ll enter the busy world of today’s government. You soon reach St. Stephen’s Hall, where visitors wait to enter the House of Commons Chamber.

St. Stephen’s Hall

St. Stephen’s Hall

This long, beautifully lit room was the original House of Commons for three centuries (from 1550 until the fire of 1834). MPs sat in church pews on either side of the hall—the ruling party on one side, the opposition on the other—a format they’d keep when they moved into the new chambers.

It was here that British history turned forever. On January 4, 1642, King Charles I marched into this room with 400 soldiers and demanded that Parliament turn over five rebels. The Speaker bluntly refused. The standoff between King and Parliament eventually snowballed into the English Civil War, the king was decapitated, and Parliament emerged triumphant.

After the fire of 1834, the hall was rebuilt. The stained glass windows—forming a tall, rectangular grid—are a textbook example of the Perpendicular Gothic style used by architect Charles Barry.

• Next, you reach the...

Central Lobby

Central Lobby

This ornate, octagonal, high-vaulted room is often called the “heart of British government,” because it sits in the geographical center of the Palace, midway between the House of Commons (to the left) and the House of Lords (right). Clerks bustle about. Constituents come to this lobby to petition, or “lobby,” their MPs (from which the term may derive). Video monitors list the schedule of meetings and events going on in this 1,100-room governmental hive.

This is the best place to admire the Palace’s interior decoration—carved wood, chandeliers, statues, and floor tiles—designed by Barry’s partner, Augustus Pugin.

• This lobby marks the end of the public space where you can wander freely. To see the House of Lords or House of Commons you must wait in line. You must also check your belongings—bag, camera, phone, even this guidebook—so read the following section before entering. While you wait, ask the attendant for any brochures.

House of Lords

House of Lords

When you’re called, you’ll walk to the Lords Chamber by way of the long Peers’ Corridor. Paintings on the corridor walls depict the antiauthoritarian spirit brewing under the reign of Charles I: You’ll see Parliament rebuffing Charles’ demands for the five MPs, and the freedom-seeking Pilgrims leaving England for America on the Mayflower. When you reach the House of Lords Chamber, you’ll watch the proceedings from the upper-level visitors gallery. Each day opens with a 30-minute session where four questions are posed to the government, usually followed by legislation and then debate.

The House of Lords consists of around 800 members, called “Peers.” They are not elected by popular vote. Some are nobles who’ve inherited the position; others are appointed by the Queen. These days, their role is largely advisory. They can propose, revise, and filibuster laws, but they have no real power to pass laws on their own. On any typical day, only a handful of the lords actually shows up to debate.

The Lords Chamber is church-like and impressive, with stained glass and intricately carved walls. The benches where the Lords sit are always upholstered red (the ones in the House of Commons are green). At the far end is the Queen’s gilded throne. She’s the only one who may sit there, and only once a year, when she gives a speech to open Parliament.

In front of the throne sits the woolsack—a cushion stuffed with wool. Here the Lord Speaker presides, with a ceremonial mace behind the backrest. To the Lord Speaker’s right (our left) are the members of the ruling party (a.k.a. “government”). The first two rows in the seats closest to the woolsack are filled with bishops. To the Lord Speaker’s left (our right) are the members of the opposition (the Labour Party, currently the largest opposition party in both houses). Unaffiliated Crossbenchers sit in between.

House of Commons

House of Commons

The Commons Chamber may be much less grandiose than the Lords’, but this is where the sausage gets made. The House of Commons is as powerful as the Lords, prime minister, and Queen combined.

This seat of power is surprisingly small—barely 3,000 square feet. The chamber was destroyed in the Blitz, and Churchill rebuilt it with the same cube-shaped floor plan. Of today’s 650-plus MPs, only 450 can sit—the rest have to stand at the ends. On any given day, most MPs are in their offices, located elsewhere in the complex or in nearby modern buildings.

As in the House of Lords, the ruling party sits on the right of the Speaker (our left), opposition on the left (our right). Television screens on the wall show the topic and who is speaking; the press box is to the left, above the government MPs. Members stand when they want to speak, waiting patiently to be called on by the Speaker.

Keep an eye out for two red lines on the floor, which cannot be crossed when debating the other side. (They’re supposedly two sword-lengths apart, to prevent a literal clashing of swords.) Between the benches is the canopied Speaker’s Chair, for the chairman who keeps order and chooses who can speak next. The clerks sit at a central table that holds the ceremonial mace, a symbol of the power given Parliament by the monarch. Also on the table are the two “dispatch boxes”—old wooden chests that serve as lecterns, one for each side.

The Queen is not allowed in the Commons Chamber. The last monarch to enter a Commons Chamber was Charles I, and you know what happened to him. When the prime minister visits, she speaks from one of the boxes. Her ministers (or cabinet) join her on the front bench, while lesser MPs (the “backbenchers”) sit behind. It’s often a fiery spectacle, as the prime minister defends her policies, while the opposition grumbles and harrumphs in displeasure. It’s not unheard-of for MPs to get out of line and be escorted out by the Serjeant at Arms (who calls in to his doorkeepers—think of them as Parliamentary bouncers—for the heavy lifting). One furious MP even grabbed the Serjeant’s hallowed mace and threw it to the ground. His career was over.

• And so is our tour. Heading back out of the sprawling complex, be sure to get a good look at—if you haven’t already—the Houses of Parliament’s best-known symbol, its giant clock tower. For a full description of what tourists call “Big Ben,” see the start of the

Westminster Walk. Big Ben is also covered on my

Westminster Walk. Big Ben is also covered on my

free Westminster Walk audio tour.

free Westminster Walk audio tour.