American Memorial Chapel (Jesus Chapel)

American Memorial Chapel (Jesus Chapel)

Horatio Nelson Monument and Charles Cornwallis Monument

Horatio Nelson Monument and Charles Cornwallis Monument

No sooner was Sir Christopher Wren selected to refurbish Old St. Paul’s Cathedral than the Great Fire of 1666 incinerated it. Within a week, Wren had a plan for a whole new building...and for the city around it, complete with some 50 new churches. For the next four decades he worked to achieve his vision—a spacious church, topped by a dome, surrounded by a flock of Wrens.

St. Paul’s is England’s national church. There’s been a church on this spot since 604. It was the symbol of London’s rise from the Great Fire of 1666 and of the city’s survival of the Blitz of 1940. It’s been the site of important weddings (Prince Charles and Lady Diana) and state funerals (Prime Ministers Churchill and Thatcher). Architecturally, it’s the masterpiece of England’s greatest Neoclassical architect. Today, it’s the center of the Anglican faith. Military buffs will find memorials to many great wars and their war heroes. Dome climbers will be rewarded with expansive views over London’s skyline.

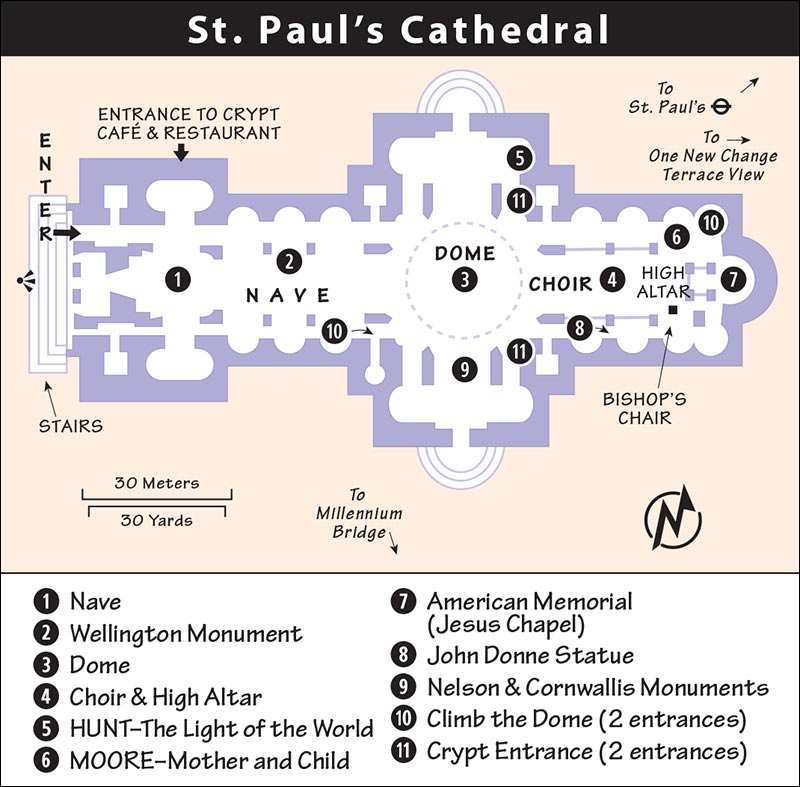

(See "St. Paul's Cathedral" map, here .)

Cost: £18, £16 in advance online (includes church entry, dome climb, crypt, tour, and audioguide). Free on Sun but officially open only to worshippers. You can use the entrance on the north side of the cathedral to go directly to the café and restaurant in the crypt (which grants a free, decent glimpse of Nelson’s tomb).

Hours: Mon-Sat 8:30-16:30 (dome opens at 9:30), closed Sun except for worship. Sometimes closed for special events—check online. The church is also open Mon-Sat 16:15-18:00 for evening worship (must enter before 17:00). It’s always free to enter the church to worship, but your visit is restricted to the back of the nave.

Avoiding Lines: Purchasing online tickets in advance saves time (and a little money), allowing you to skip the line; otherwise the wait can be 15-30 minutes in summer and on weekends. To avoid the crowds in general, arrive first thing in the morning or late in the afternoon.

Getting There: Located in The City; Tube: St. Paul’s (other nearby Tube stops include Mansion House, Cannon Street, and Blackfriars). You can take handy buses #15 and #11 (see here ), as well as #4, #23, or #26. Careful: Don’t head for tiny St. Paul’s Church near Covent Garden; your destination is St. Paul’s Cathedral, in The City.

Information: Recorded info tel. 020/7246-8348, reception tel. 020/7246-8350, www.stpauls.co.uk .

Music and Church Services: If interested, check the website for worship times the day of your visit. Communion is generally Mon-Sat at 8:00 and 12:30. On Sunday, services are held at 8:00, 10:15 (Matins), 11:30 (sung Eucharist), 15:15 (evensong), and 18:00. The rest of the week, evensong is at 17:00 Tue-Sat (not Mon). If you come 20 minutes early for evensong worship (under the dome), you may be able to grab a big wooden stall in the choir, next to the singers. On some Sundays, there’s a free organ recital at 16:45.

Tours: Guided 1.5-hour tours are offered Mon-Sat at 10:00, 11:00, 13:00, and 14:00 (call to confirm or ask at church). Free 20-minute introductory talks are offered throughout the day. The multimedia guide (included with admission) contains video clips that show the church in action.

Download my free St. Paul’s Cathedral audio tour.

Download my free St. Paul’s Cathedral audio tour.

Climbing the Dome: It’s 528 steps to the top and a mere 257 to the first viewing level. (While there’s an elevator for people with disabilities, it does not go up into the dome’s galleries—only down to the crypt.) Allow an hour to go up and down. The tower has three levels, called galleries. The climb gets steeper, narrower, and more claustrophobic as you go higher. It’s a one-way system, so you can’t come back down until you reach the next level.

Length of This Tour: Allow one hour, two if you climb the dome. If you’re in a rush, skip the crypt and the dome.

Photography: No photography allowed.

Eating: There’s a good $ café (soups, sandwiches, and main dishes) and a pricier $$$$ restaurant (also serves afternoon tea) in the crypt; free access from north side of church. Several places to get a quick bite are on Paternoster Square; for another choice, see here .

Nearby: A helpful TI is located to the right of the church. Just behind the church, to the east, is the One New Change modern shopping mall topped by a terrace with great views of the church—not a bad substitute for the dome climb for those disinclined to pay the entry fee and/or climb so many steps (free elevator to top floor). Millennium Bridge is a five-minute walk south, leading to the South Bank (Tate Modern and Shakespeare’s Globe).

Starring: Sir Christopher Wren, his dome, and World War II.

(See "St. Paul's Cathedral" map, here .)

Even now, as skyscrapers encroach, the 365-foot-high dome of St. Paul’s rises majestically above the rooftops of the neighborhood. The tall dome is set on classical columns, capped with a lantern, topped by a six-foot ball, and iced with a cross. As the first Anglican cathedral built in London after the Reformation, it is Baroque: St. Peter’s in Rome filtered through clear-eyed English reason.

Viewing St. Paul’s facade from in front of the church, you can see the story of Paul’s conversion told in the stone pediment. A blinding flash of light leaves Saul sightless on the road to Damascus (see cityscape, lower left). When his sight is restored he becomes Paul, the Christian. This was the pivotal moment in the life of the man who established Christianity as a world religion through his travels, writing, and evangelizing.

While Paul stands on the top, Peter (with the annoying cock that crowed three times, symbolizing his betrayal of Jesus) is to the left, and James is on the right. The four evangelists at the towers’ bases each carry the gospel they wrote. As Queen Anne was on the throne when the church was finished in 1710, the statue in front portrays her.

• Enter, buy your ticket, and stand at the far back of the nave, behind the font.

Nave

Nave

Look down the nave through the choir stalls to the stained glass at the far end. This big church feels big. At 515 feet long and 250 feet wide, it’s Europe’s fourth largest, after those in Rome (St. Peter’s), Sevilla, and Milan. The spaciousness is accentuated by the relative lack of decoration. The simple, cream-colored ceiling and the clear glass in the windows light everything evenly. Wren wanted this: a simple, open church with nothing to hide. Unfortunately, only this entrance area keeps his original vision—the rest was encrusted with 19th-century Victorian ornamentation.

A diamond-shaped plaque on the floor honors the guards (“St. Paul’s Watch”) who worked so valiantly from 1939 until 1945 to save the church from WWII destruction. On the wall next to the door, a dirty panel of stone remains, reminding visitors how dark the entire church was before undergoing a huge cleaning in preparation for the 300th anniversary of the first service held here. Remarkably, this is the first great church completed in the lifetime of its architect (built 1675-1710).

• Glance up and behind. The organ trumpets say, “Come to the evensong and hear us play.” Ahead and on the left is the towering, black-and-white...

Wellington Monument

Wellington Monument

It’s so tall that even Wellington’s horse has to duck to avoid bumping its head. Wren would have been appalled, but his church has become so central to England’s soul that many national heroes are buried here (in the basement crypt). General Wellington, Napoleon’s conqueror at Waterloo (1815) and the embodiment of British stiff-upper-lippedness, was honored here in a funeral packed with 13,000 fans. The church is littered with memorials. While all the monuments are upstairs, all the tombs are downstairs.

• Stroll up the same nave Prince Charles and Lady Diana walked on their 1981 wedding day. Imagine how they felt making the hike to the altar with the world watching. Grab a chair underneath the impressive...

Dome

Dome

The dome you see from here, painted with scenes from the life of St. Paul, is only the innermost of three. From the painted interior of the first dome, look up through the opening to see the light-filled lantern of the second dome. Finally, the whole thing is covered on the outside by the third and final dome, the shell of lead-covered wood that you see from the street. Wren’s ingenious three-in-one design was psychological as well as functional—he wanted a low, shallow inner dome so worshippers wouldn’t feel diminished.

You’ll see tourists walking around the base of the dome in the Whispering Gallery. The dome is constructed with such acoustic precision that secrets whispered from one side of it are heard on the opposite side, 170 feet away.

Christopher Wren (1632-1723) was the right man at the right time. Though the 31-year-old astronomy professor had never built a major building in his life when he got the commission for St. Paul’s, his reputation for brilliance and his unique ability to work with others carried him through. The church has the clean lines and geometric simplicity of the age of Newton, when reason was holy and God set the planets spinning in perfect geometrical motion.

For more than 40 years, Wren worked on this site, overseeing every detail of St. Paul’s and the 65,000-ton dome. It’s estimated that the dome cost $850 million (in today’s dollars). At age 75, Wren got to look up and see his son place the cross on top of the dome, completing the masterpiece.

On the floor directly beneath the dome is a brass grate—part of a 19th-century attempt to heat the church. Encircling it is Christopher Wren’s name and epitaph, written in Latin: Lector, si monumentum requiris circumspice (Reader, if you seek his monument, look around you) .

Now review the ceiling: Behind is Wren simplicity and ahead is Victorian ornateness.

• The choir area blocks your way, but you can see the altar at the far end under a golden canopy.

Choir and High Altar

Choir and High Altar

English churches, unlike most in Europe, often have a central choir area (a.k.a. a “quire” or “chancel”), where church officials and the singers sit. (You can see St. Paul’s well-known choir of 30 boys and 12 men in action, singing psalms, at the evensong service, held daily except Monday.) St. Paul’s—a cathedral since 604—is home to the local Anglican bishop, who presides in the chair nearest the altar on the south, or right, side (the carved bishop’s hat hangs over the chair).

The ceiling above the choir is a riot of glass mosaics, representing God (above the altar) and his creation. The mosaics are very Victorian. In fact, Queen Victoria complained that the earlier ceiling was “dreary and undevotional.” The Dean and chapter wisely took note and had it spiffed up with this brilliant mosaic work...textbook late Victorian. In separate spheres, eight “Angels of the Morning” hold up creatures of the earth, sea, and sky.

The high altar (the marble slab with crucifix and candlesticks—you’ll get a close look later) sits under a huge canopy with corkscrew columns. The canopy looks ancient, but it only dates from 1958, when it was rebuilt after being heavily damaged in October 1940 by the bombs of Hitler’s Luftwaffe. For regular services, the priest stands beneath the dome on the low wooden platform.

• In the north transept (to your left as you face the altar), find the big painting of Christ, in a golden wood altarpiece. Glare? Try walking side to side to find the best viewing angle.

The Light of the World,

1904

The Light of the World,

1904

In the dark of night, Jesus—with a lantern, halo, jeweled cape, and crown of thorns—approaches an out-of-the-way home in the woods, knocks on the door, and listens for an invitation to come in. A Bible passage on the picture frame says: “Behold, I stand at the door and knock...” (Revelation 3:20).

In his early twenties, William Holman Hunt (1827-1910) was in the dark night of a spiritual crisis when he heard this verse knocking in his head. He opened his soul to Christ, his life changed forever, and he tried to capture the experience in paint. As one of the Pre-Raphaelites who adored medieval art (see here ), he used symbolism, but only images the average Brit-on-the-street could understand. The door is the closed mind, the weeds the neglected soul, the darkness is malaise, while Christ carries the lantern of spiritual enlightenment.

In 1854, Hunt debuted The Light of the World (not this version, but a smaller one now at Oxford). The critics savaged it—“syrupy,” “too Catholic,” “simple”—but the masses lapped it up. It became the most famous painting in Victorian England—in fact, in the whole world. It was taken on tour through the vast British Empire, and was reproduced in countless engravings. It became a pop icon that inspired sermons, poems, hymns, and countless Christ-at-the-door paintings in churches and homes. Hunt’s humble-hippie image of Christ was stamped forever on the minds of generations of schoolkids. It was so popular that late in life Hunt was asked to do this larger version specifically for St. Paul’s. Nearly blind, he needed an assistant. (The Guardian newspaper once published a list of “Britain’s Ten Worst Paintings.” They honored The Light of the World as number seven, comparing it to a plastic crucifix.)

• Return to the area underneath the dome and walk toward the altar, along the left side of the choir, pausing at a modern statue.

Mother and Child,

1983

Mother and Child,

1983

Britain’s (and perhaps the world’s?) greatest modern sculptor, Henry Moore, rendered a traditional subject in marble in an abstract, minimalist way. This Mary-and-Baby-Jesus was inspired by the sight of British moms nursing babies in WWII bomb shelters. Moore intended the viewer to touch and interact with the art. It’s OK.

• Continue to the altar at the far end of the church. The area behind it has three bright and modern stained-glass windows.

American Memorial Chapel (Jesus Chapel)

American Memorial Chapel (Jesus Chapel)

This special spot in St. Paul’s honors the Americans who sacrificed their lives to save Britain in World War II. An inscription on the floor reads: “To the American Dead of the Second World War, From the People of Britain.”

Each of the three windows has a central core of religious scenes, but the brightly colored panes that arch around them have some unusual iconography: American. Spot the American eagle (center window, to the left of Christ), George Washington (right window, upper-right corner), and symbols of all 50 states (find your state seal). In the carved wood beneath the windows, you’ll see birds and foliage native to the US. And at the very far right of the paneling, check out the tiny tree “trunk” (amid foliage, below the bird)—it’s a US rocket ship circa 1958, shooting up to the stars.

Britain is very grateful to its WWII saviors, the Yanks, and remembers them religiously with the Roll of Honor (immediately behind the altar). This 500-page book under glass lists the names of 28,000 US servicemen and women based in Britain who gave their lives during the war.

• Take a close look at the high altar and the view back to the entrance from here. Look up and enjoy the Victorian mosaic ceiling above the choir. Then continue around the altar and head back toward the entrance. On the left wall of the aisle, standing white in a black niche, is a statue of...

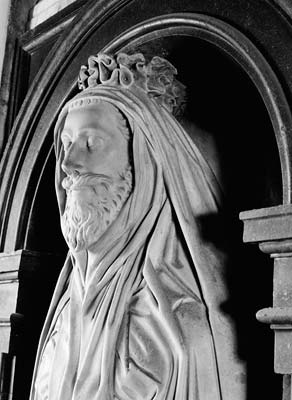

John Donne

John Donne

John Donne (1573-1631), shown here wrapped in a burial shroud, was not only a great poet, but also a passionate preacher. He spent the last decade of his life working in old St. Paul’s. Donne personally chose to be portrayed here in a shroud to capture the melancholy he felt after his wife’s death. The statue is one of the few treasures to survive the Great Fire of 1666. You can still see the dark scorch marks on the urn beneath Donne’s feet.

Imagine hearing Donne deliver a funeral sermon here, with the huge church bell tolling in the background: “No man is an island...Any man’s death diminishes me, because I am involved in Mankind. Therefore, never wonder for whom the bell tolls—it tolls for thee.”

• And also for dozens of people who lie buried beneath your feet, in the crypt where you’ll end your tour. But first, in the south transept, find the...

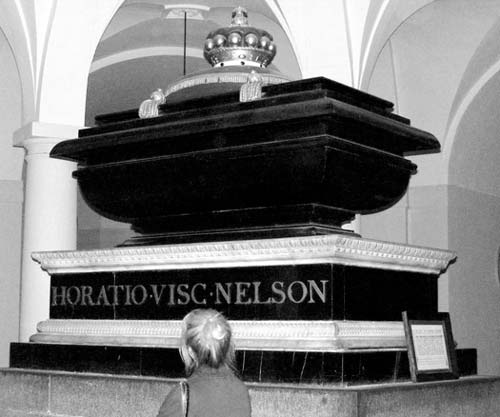

Horatio Nelson Monument and Charles Cornwallis Monument

Horatio Nelson Monument and Charles Cornwallis Monument

Admiral Horatio Nelson (1758-1805) leans on an anchor, his coat draped discreetly over the arm he lost in battle.

In October 1805, England trembled in fear as Napoleon—bent on world conquest—prepared to invade from across the Channel. Meanwhile, hundreds of miles away, off the coast of Spain, the daring Lord Nelson sailed the HMS Victory into battle against the French and Spanish navies. His motto: England expects that every man shall do his duty.

Nelson’s fleet smashed the enemy at Trafalgar, and Napoleon’s hopes for a naval invasion of Britain sank. Unfortunately, Nelson took a sniper’s bullet in the spine and died. The lion at Nelson’s feet groans sadly, and two little boys gaze up—one at Nelson, one at Wren’s dome. You’ll find Nelson’s tomb directly beneath the dome, downstairs in the crypt.

Opposite Nelson is a monument to another great military man, Charles Cornwallis (1738-1805), honored here for his service as Governor General of Bengal (India). Yanks know him better as the general who lost the American Revolutionary War (or “American War,” as it’s known here) when George Washington—aided by French ships—forced his surrender at Yorktown in 1780.

• There are several entrances to the dome and its galleries, but only one is open to the public at any given time—look for signboards or ask one of the church volunteers.

Climb the Dome

Climb the Dome

The 528-step climb is worthwhile, and each level (or gallery) offers something different.

First you get to the Whispering Gallery (257 steps, with views of the church interior). Whisper sweet nothings into the wall, and your partner (and anyone else) standing far away can hear you. Exactly how it works is debated (some even question if it works). Most likely, the sound does not travel up and over the dome to the diametrically opposite side (as it would in a perfect sphere). Rather, it goes around the curved wall horizontally, so you don’t have to stand in any particular spot. For best effects, try whispering (not talking) with your mouth close to the wall, while your partner stands a few dozen yards away with his or her ear to the wall.

After another set of stairs, you’re at the Stone Gallery, with views of London. If you’re exhausted, claustrophobic, or wary of heights, this middle level might be high enough. (The top level has very little standing room for tourists.)

Finally, a long, tight metal staircase takes you to the very top of the cupola, the Golden Gallery. (Just before the final dozen stairs to the top, there’s a tiny window at your feet that allows you to peek directly down—350 feet—to the church floor.) Once at the top, you emerge to stunning, unobstructed views of the city. Looking west, you’ll see the London Eye and Big Ben. To the south, across the Thames, is the rectangular smokestack of the Tate Modern, with Shakespeare’s Globe nestled nearby. To the east sprouts a glassy garden of skyscrapers, including the 600-foot-tall, black-topped Tower 42, the bullet-shaped 30 St. Mary Axe building (nicknamed “The Gherkin”), and two more buildings easily ID’d by their nicknames—“The Cheese Grater” and “The Walkie-Talkie.” Farther in the distance, the cluster of skyscrapers marks Canary Wharf. Just north of that was the site of the 2012 Olympic Games, now a pleasant park. Demographers speculate that the rapidly growing East End and Docklands may eventually replace the West End and The City as the center of London. So as you look to the east, you’re gazing into London’s future.

• Descend the dome to church level, then follow signs directing you downstairs to the...

Crypt

Crypt

Many famous people are buried here. Start by locating the central tomb of Horatio Nelson, who wore down Napoleon. It’s a big coffin-on-a-pedestal in a round alcove at the center of the crypt, directly beneath the dome. Nearby (toward the altar) is the granite tomb of the Duke of Wellington (who finished Napoleon off). The flags near the tomb were carried at his funeral procession.

Continuing up the central axis of the crypt, you enter a chapel. At the chapel’s altar, turn right to reach Christopher Wren ’s tomb—a simple black slab with no statue. Next to it is a hunk of rough Portland stone quarried but unused by Wren while building St. Paul’s; see his triangle brand on the left end. These few stones are not much of an honor for the man who built this great church. “If you seek his monument...” you’ll be disappointed.

Use your visitor’s map to find other tombs and memorials: of painters Turner and Reynolds (located near Wren); of Florence Nightingale (near Wellington); and a memorial to George Washington, who lies buried back in old Virginny.

Back near Nelson’s tomb you’ll find temporary exhibits (they change frequently) that chronicle important events in the church’s long history, and models of previous churches that stood on this spot.

The crypt contains a fine gift shop, a WC, a restaurant, and the grim-sounding $ Crypt Café, which nevertheless serves tasty food.