Along the South Bank of the Thames

Old Operating Theatre Museum and Herb Garret

Old Operating Theatre Museum and Herb Garret

The George Inn and (Faint Echoes of) Other Historic Taverns

The George Inn and (Faint Echoes of) Other Historic Taverns

Millennium Bridge and View of the Thames

Millennium Bridge and View of the Thames

Bankside—the neighborhood between London Bridge and Blackfriars Bridge—is the historic heart of the revamped southern bank of the Thames. In ancient times “greater London” consisted of two Roman settlements straddling the easiest place to ford the river: One settlement was here, and the other was across the river—in the financial district known today as “The City.”

From the Roman era until recently, the south side of the river was the wrong side of the tracks. For centuries, it was London’s red light district. In the 20th century, it became an industrial wasteland of empty warehouses and street crime. Today, the prostitutes and pickpockets are gone, replaced by a riverside promenade dotted with trendy pubs, cutesy shops, and historic tourist sights.

This half-mile Bankside Walk gives you plenty of history and sights to choose from—you can see it all, design your own plan, or just enjoy the view of London’s skyline across the river.

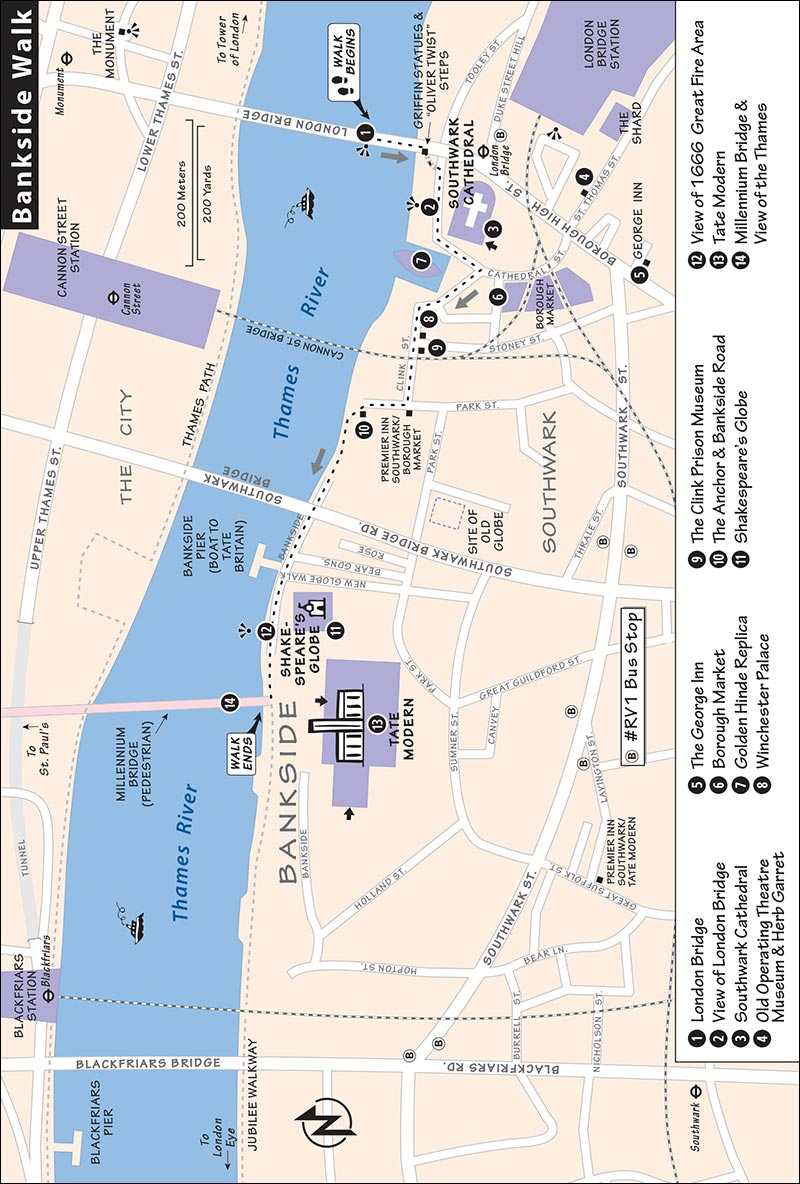

(See "Bankside Walk" map, here .)

Length of This Walk: One hour (or up to a half-day if you tour Shakespeare’s Globe and the Tate Modern).

Getting There: Take the Tube to the London Bridge stop to begin the walk. (The Monument stop, on the Circle Line, is also nearby.)

Old Operating Theatre Museum and Herb Garret: £6.50, daily 10:30-17:00, closed Dec 15-Jan 5.

Southwark Cathedral: Free, but £4 suggested donation (be prepared with at least £1 or a simple “No”); Mon-Fri 8:00-18:00, Sat-Sun 8:30-18:00 (but partially closed during frequent services—schedule posted out front).

Borough Market: London’s oldest fruit-and-vegetable market is open Wed-Thu 10:00-17:00, Fri 10:00-18:00, Sat 8:00-17:00, closed Sun-Tue; surrounding eatery stalls open daily 10:00-17:00.

Golden Hinde Replica: £6, daily 10:00-17:00, sometimes closed for private events.

The Clink Prison Museum: Overpriced at £7.50; July-Sept daily 10:00-21:00; Oct-June Mon-Fri 10:00-18:00, Sat-Sun until 19:30.

Shakespeare’s Globe: £15, includes museum, audioguide, and 40-minute guided tour; open daily 9:00-17:30, late April-mid-Oct last tour Mon at 17:00, Tue-Sat at 12:30, Sun at 11:30 (see here or the Entertainment in London chapter for how to buy tickets to a performance).

Tate Modern: Free, but £4 donation appreciated (fee for special exhibits), daily 10:00-18:00, Fri-Sat until 22:00, last entry to temporary exhibits 45 minutes before closing, view restaurant on top floor.

Starring: Shakespeare’s world, London Bridge, historic pubs, and views of the London skyline.

(See "Bankside Walk" map, here .)

• Start at the south end of London Bridge (across from where my Historic London: The City Walk ends; see here ). From the London Bridge Tube stop, take the “Borough High Street east” exit and turn right (north), pass the One London Bridge complex, and walk out on the bridge about 100 yards .

London Bridge

London Bridge

The City (across the river) is to the north, Tower Bridge is east, and the Thames flows from west to east (left to right). Looking to the east (downstream) and turning counterclockwise, you’ll see the following:

• Tower Bridge, the Neo-Gothic towered drawbridge that many Americans mistakenly call London Bridge.

• The HMS Belfast (in the foreground, docked on the southern bank), a WWII cruiser that’s open to tourists.

• Canary Wharf Tower (the distant 800-foot skyscraper with pyramid top and blinking light), built in 1990 on the Isle of Dogs. It recently lost its standing as the UK’s tallest building to The Shard. This marks the Docklands, London’s “new Manhattan” and a thriving business district. This was once the biggest port in the world, serving the empire upon which “the sun never set,” but today the wharves have moved farther out to accommodate bigger ships.

• The “Pool of London.” This is the stretch of river between Tower Bridge (a drawbridge) and London Bridge, which marks the farthest point seagoing vessels can sail inland. In the 18th century this was the busiest port in the world.

• The Tower of London (four domed spires and a flag rising above the trees).

• The 20 Fenchurch Street skyscraper (a.k.a. “The Walkie-Talkie”) and, behind it, the Leadenhall Building (a.k.a. “The Cheese Grater”).

• St. Paul’s Cathedral (to the northwest, with a dome like a state capitol and twin spires).

• St. Bride’s Church, the pointed, stacked steeple (nestled among office buildings) that supposedly inspired the wedding cake.

• BT Tower, a communications tower.

• The Tate Modern art museum (square brick smokestack tower, barely visible).

• Southwark Cathedral (100 yards away, may not be visible from where you’re standing).

• Borough High Street, the busy street that London Bridge spills onto.

• The small griffin statues (winged lions holding shields) at the south end of London Bridge guard the entrance to The City. They marked the jurisdiction of The City to include both sides of the all-important river. For centuries, they said, “Neener neener” to late-night partiers who got locked out of town when the gates shut tight at curfew.

• The Shard, one of London’s most famous skyscrapers. At 1,020 feet, it’s the tallest building in Western Europe. It looks unfinished, but that’s art. (For details on the building—including the observation deck at its tip, see here .)

• The best view of London Bridge is not from the bridge itself, but from the riverbank. Retrace your steps back to the south end of the bridge and cross the street. Find the small staircase next to the southwest griffin, by the building marked Two London Bridge. These stairs will impress fans of Charles Dickens’ Oliver Twist—they’re the setting of the infamous “Meeting on the Bridge.” Turn right at the bottom of the stairs and follow the river to a...

View of London Bridge

View of London Bridge

The bridge of today—three spans of boring, traffic-clogged concrete, built in 1972—is (at least) the fourth incarnation of this 2,000-year-old river crossing. The Romans (A.D. 50) built the first wooden footbridge to Londinium (rebuilt many times), which was pulled down by boatmen in 1014 to retake London from Danish invaders. (They celebrated with a song passed down to us as “London Bridge is falling down, my fair lady.”)

The most famous version—crossed by everyone from Richard the Lionheart, to Henry VIII, to Shakespeare, to Newton, to Darwin—was built around 1200 and stood for more than six centuries, the only crossing point into this major city. Built of stone on many thick pilings, stacked with houses and shops that arched over the roadway and bulged out over the river, with its own chapel and a fortified gate at each end, it was a neighborhood unto itself (pop. 300). Picture Mel Gibson’s head boiled in tar and stuck on a spike along the bridge (like the Scots rebel William Wallace in 1305, depicted in Gibson’s movie Braveheart ), and you’ll capture the local color of that time.

In 1823, the famous bridge was replaced with a more modern (but less impressive) brick one. In 1967, that brick bridge was sold to an American, dismantled, shipped to Arizona, and reassembled (all 10,000 bricks) in Lake Havasu City. (Humor today’s Brits, who’d like to believe the Yank thought he was buying Tower Bridge.) It was only then that today’s bridge was built.

• Circle around the cathedral and find the entrance on the opposite side.

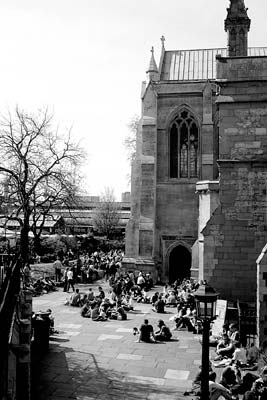

Southwark Cathedral

Southwark Cathedral

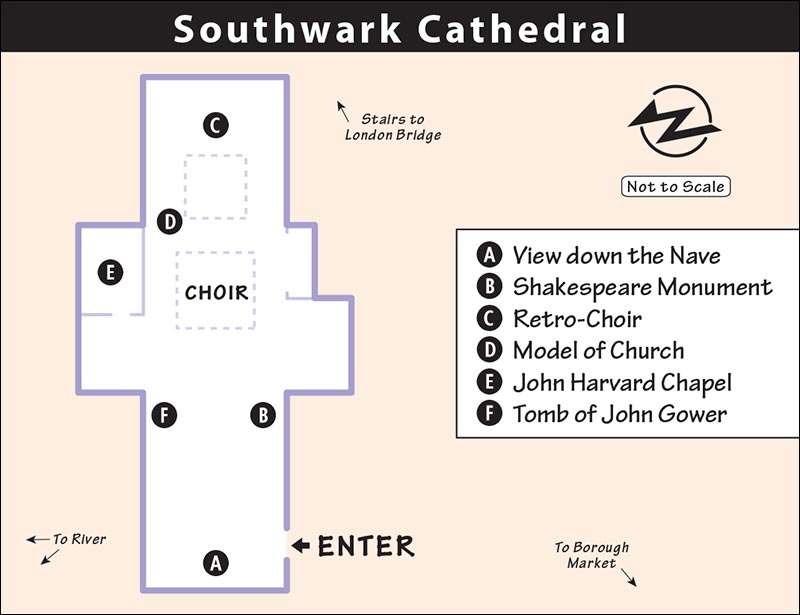

(See "Southwark Cathedral" map, here .)

This neighborhood parish church is where Shakespeare prayed while his brother Edmund rang the bells. The Southwark (SUTH-uck) church dates back to 1207, though the site has had a church for at least a thousand years, and inhabitants for 2,000. The church is simply filled with history (pick up the info flier).

View down the Nave:

Clean and sparse, with warm golden stone, the church is a symbol of the urban renewal of the whole Bankside/Southwark area. Its WWII damage has been repaired, with replacement windows of unstained glass on the right side. The nave bends slightly to the left (the chandelier, ceiling arches, and altar don’t line up until you take two baby steps left) as a medieval tribute to Christ’s bent body on the cross.

View down the Nave:

Clean and sparse, with warm golden stone, the church is a symbol of the urban renewal of the whole Bankside/Southwark area. Its WWII damage has been repaired, with replacement windows of unstained glass on the right side. The nave bends slightly to the left (the chandelier, ceiling arches, and altar don’t line up until you take two baby steps left) as a medieval tribute to Christ’s bent body on the cross.

• Work your way counterclockwise around the church.

Shakespeare Monument:

William reclines in front of a backdrop of the 16th-century Bankside skyline (view looking north). Find (left to right) the original Globe Theatre, Winchester Palace, Southwark Cathedral, and the old London Bridge with its arched gate—complete with heads on pikes, ISIS-style. Shakespeare seems to be dreaming about the many characters of his plays, depicted in the stained-glass window above (see Hamlet addressing a skull, right window). To the right is a plaque to the American actor Sam Wanamaker, who spearheaded the building of a replica of Shakespeare’s Globe Theatre (explained later in this chapter). Shakespeare’s brother Edmund is buried in the church, possibly under a marked slab on the floor of the choir area, near the very center of the church. (The Bard lies buried in his hometown of Stratford-upon-Avon.)

Shakespeare Monument:

William reclines in front of a backdrop of the 16th-century Bankside skyline (view looking north). Find (left to right) the original Globe Theatre, Winchester Palace, Southwark Cathedral, and the old London Bridge with its arched gate—complete with heads on pikes, ISIS-style. Shakespeare seems to be dreaming about the many characters of his plays, depicted in the stained-glass window above (see Hamlet addressing a skull, right window). To the right is a plaque to the American actor Sam Wanamaker, who spearheaded the building of a replica of Shakespeare’s Globe Theatre (explained later in this chapter). Shakespeare’s brother Edmund is buried in the church, possibly under a marked slab on the floor of the choir area, near the very center of the church. (The Bard lies buried in his hometown of Stratford-upon-Avon.)

Retro-Choir:

The 800-year-old crisscross arches and stone tracery in the windows are some of the oldest parts of this historic church. Located in the heart of the industrial district, the church was heavily bombed during World War II and then rebuilt.

Retro-Choir:

The 800-year-old crisscross arches and stone tracery in the windows are some of the oldest parts of this historic church. Located in the heart of the industrial district, the church was heavily bombed during World War II and then rebuilt.

Model of Church:

Tucked in behind the choir, find a model (marked Church and Priory of St. Mary Overy

) of the church and old Winchester Palace complex—a helpful reconstruction before we visit the paltry Winchester Palace ruins.

Model of Church:

Tucked in behind the choir, find a model (marked Church and Priory of St. Mary Overy

) of the church and old Winchester Palace complex—a helpful reconstruction before we visit the paltry Winchester Palace ruins.

John Harvard Chapel:

The Southwark-born son of an innkeeper (see the record of baptism at the bottom of the window) inherited money from the sale of The Queen’s Head tavern, got married, and sailed to Boston (1637), where he soon died. The money and his 400-book library funded the start of Harvard University.

John Harvard Chapel:

The Southwark-born son of an innkeeper (see the record of baptism at the bottom of the window) inherited money from the sale of The Queen’s Head tavern, got married, and sailed to Boston (1637), where he soon died. The money and his 400-book library funded the start of Harvard University.

Tomb of John Gower:

The poet and friend of Chaucer (c. 1400) rests his head on his three books, one written in Middle English, one in French, and one in Latin—the three languages from which modern English soon emerged.

Tomb of John Gower:

The poet and friend of Chaucer (c. 1400) rests his head on his three books, one written in Middle English, one in French, and one in Latin—the three languages from which modern English soon emerged.

• This walk is a pick-and-choose collection of sights. If you’re interested in visiting the Old Operating Theatre Museum and Borough High Street inns, described next, see them first before heading west (use the map to locate these nearby sights).

Old Operating Theatre Museum and Herb Garret

Old Operating Theatre Museum and Herb Garret

Back when the common cold was treated with a refreshing bloodletting, the Old Operating Theatre—a surgical operating room from the 1800s—was a shining example of “modern” medicine. Today a museum, this is a quirky, sometimes gross look at that painful transition from folk remedy to clinical health care. Originally part of a larger hospital complex, the Old Operating Theatre was boarded up when the hospital relocated, lying untouched for 100 years until its chance discovery in 1956. The location alone—in a long-forgotten attic above a church, reached by a steep spiral staircase—makes this odd place worth a visit.

After buying your ticket, climb a few more stairs into a big room under heavy timbers—the Herb Garret, which was used to dry herbs for the former hospital. Today, it displays healing plants used for millennia—different ones for each of the traditional four ailments (melancholic, choleric, sanguine, phlegmatic), supposedly caused by an imbalance in the body’s traditional four substances, or “humours” (black bile, yellow bile, blood, and phlegm), corresponding to the earth’s traditional four elements (earth, wind, fire, and Ringo). Florence Nightingale, the nurse famed for saving so many Crimean War soldiers wounded in Russia, worked here to improve sanitation and to turn nurses from low-paid domestics into trained doctors’ assistants.

The small hallway leading to the theater displays crude anesthetics (ether, chloroform, three pints of ale), surgical instruments by Black & Decker (knives, saws, drills), and a glaring lack of antiseptics—that is, until young Dr. Joseph Lister discovered carbolic acid, which reduced the high rates of mortality (and halitosis).

Up the stairs, the Old Operating Theatre is the highlight—a semicircular room surrounded by railings for 150 spectators (truly a “theater”), where doctors operated on patients while med students observed.

The patients were often poor women, blindfolded for their own modesty. The doctors donated their time to help, practice, and teach (see the motto Miseratione non Mercede: “Out of compassion, not for profit”). The surgeries, usually amputations, were performed under very crude working conditions—under the skylight or by gaslight, with no sink, and only sawdust to sop up blood. (A false floor held another layer of sawdust to stop the blood before it dripped through to the ceiling of the church below.) The wood still bears bloodstains. Nearly one in three patients died. There was a fine line between Victorian-era surgeons and Jack the Ripper.

• Farther down Borough High Street (on the left-hand side), you’ll find...

The George Inn and (Faint Echoes of) Other Historic Taverns

The George Inn and (Faint Echoes of) Other Historic Taverns

The George is the last of many “coaching inns” that lined the main highway from London to all points south. Like Greyhound bus stations, each inn was a terminal for far-flung journeys, since coaches were forbidden inside The City. They offered food, drink, beds, and entertainment for travelers—Shakespeare, as a young actor, likely performed in The George’s courtyard. On a sunny day, the courtyard is a fine place for a break from the Borough High Street bustle (food served all day long, five ales on tap—including their own brew).

• Walk back to Southwark Cathedral. On your way, you’ll find the...

Borough Market

Borough Market

Historically, the first trading started at 2:00 in the morning at this open-air wholesale produce market. Workers could knock off by sunrise for a pint at the specially licensed Market Porter tavern (on Park Street—and still popular). From Wednesday through Saturday, the colorful market opens for retail sales to Londoners seeking trendy specialty and organic foods, and the surrounding lunch market sizzles all week long. It’s great for gathering a picnic on a sunny day. Of the many market stalls, the Ginger Pig is the place for serious English sausage and bacon (west end of market, across from Park Street), while Maria’s Market Café is a colorful eatery popular with market workers (the red stall in the middle of the market).

First started a thousand years ago on London Bridge, where country farmers brought fresh goods to the city gates, the market now sits here under a Victorian arcade. The railroad rumbling overhead, knifing right through dingy apartment houses (and the Globe Tavern), only adds to the color of London’s oldest vegetable market and public gathering spot.

A detour westward through the market leads to Park Street, with an old 19th-century ambience that makes it popular as a filming location. Check out the colorful pub and the fragrant cheese shop at Neal’s Yard Dairy.

If you’re hungry, food stalls are plentiful here (and open daily), but seating is scarce. A new glassed-in section by High Street has lots of benches for munching.

• Walk to the river along Cathedral Street, veering left at the Y. (Alternatively, from the far end of the market, turn right down Stoney Street, then right again on Clink Street.)

Golden Hinde

Replica

Golden Hinde

Replica

As we all learned in school, “Sir Francis Drake circumcised the globe with a hundred-foot clipper.” Or something like that...

Imagine a hundred men on a boat this size (yes, this replica is full-size) circling the globe on a three-year voyage, sleeping on the wave-swept decks, suffering bad food, floggings, doldrums, B.O., and attacks from foreigners. They explored unknown waters and were paid only from whatever riches they could find or steal along the way. (I took a bus tour like that once.)

The Golden Hinde (see the female deer, or hind, on the prow and stern) was Sir Francis Drake’s flagship as he circumnavigated the globe (1577-1580). Drake, a farmer’s son who followed the lure of the sea, hated Spaniards. So did Queen Elizabeth I, who hired him to plunder rich Spanish vessels and New World colonies in England’s name.

With 164 men on five small ships (the Hinde was the largest, at 100 tons and 18 cannons), he sailed southwest, dipping around South America, raiding Spanish ships and towns in Chile, and inching up the coast perhaps as far as Canada. By the time it continued across the Pacific to Asia and beyond, the Hinde was so full of booty that its crew replaced the rock ballast with gold ingots and silver coins. Three years later, Drake—with only one remaining ship and 56 men—sailed the Hinde up the Thames, unloading a fabulously valuable hoard of gold, silver, emeralds, diamonds, pearls, silks, cloves, and spices before the queen. A grateful Elizabeth knighted Drake on the main deck and kissed him on his Golden Hinde.

The Hinde was retired gloriously, but rotted away from neglect. Drake received a large share of the wealth, became enormously famous, and later gained more glory defeating the Spanish Armada (aided by “the winds of God”) in the decisive battle in the English Channel, off Plymouth (1588), making England ruler of the waves.

The galleon replica, a working ship that has itself circled the globe, is berthed at St. Mary Overie Dock (“St. Mary’s over the river”), a public dock available for free to all Southwark residents. A victim of WWII bombing and container ships that require big berths and deep water, the Thames river trade that used to thrive even this far upstream is now concentrated east of Tower Bridge. Only a few brick warehouses remain (just west of here), waiting to be leveled or yuppified. Although you can pay to enter the ship, it’s not worth the cost of admission.

• There’s a fine view (with a handy chart to identify things) from the riverside. The beach below is fun for beachcombing—old red roof tiles and little chunks of disposable clay tobacco pipes litter the rocks at low tide. From here, the Monument is visible across London Bridge, poking its bristly bronze head above the ugly postwar buildings. Londoners have fun nicknaming their new skyscrapers. See if you can pick out The Gherkin, The Cheese Grater, and The Walkie-Talkie. Now go up the street across from the Golden Hinde’s gangplank (Pickfords Wharf) and head west. About 25 yards ahead on the left are the excavated ruins of...

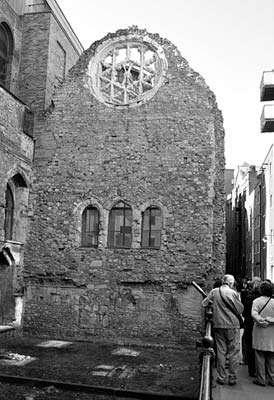

Winchester Palace

Winchester Palace

All that remains today is a wall with a medieval rose window, but this was once a lavish 80-acre estate stretching along 200 feet of waterfront. It had a palace, gardens, fountains, stables, tennis courts, a working farm, and a fish-stocked lake. The wall marks the west end of the Great Hall (134 feet by 29 feet), the banquet room for receptions held by the palace’s owner, the Bishop of Winchester.

Bishops from 1106 to 1626 lived here as wealthy, worldly rulers of the Bankside area, outside the jurisdiction of The City. They profited from activities that were illegal across the river, such as prostitution and gambling. They were a law unto themselves, with their own courts and prisons. One famous prison—the Clink—built by the bishops remained, even after its creators were ousted by a Puritan Parliament.

• Fifty yards farther west (along what is now called Clink Street) is...

The Clink Prison Museum

The Clink Prison Museum

Now an overpriced and disappointing museum that feels like a Disney ride with a few historic artifacts tossed in, this prison gave us our expression “thrown in the Clink,” from the sound of prisoners’ chains. It burned down in 1780, but the underground cells remain, featuring historical information on wall plaques, many torture devices, and a generally creepy, claustrophobic atmosphere.

Originally part of Winchester Palace, it housed troublemakers who upset the smooth running of the bishop’s 22 licensed brothels (called “the stews”), gambling dens, and taverns. Bouncers delivered drunks who were out of control, johns who couldn’t pay, and prostitutes (“women living by their bodies”) who tried to go freelance or cheated loyal customers. Offending prostitutes had their heads shaved and breasts bared, and were carted through the streets and whipped while people jeered. They might share cells side by side with “heretics”—namely, priests who’d crossed their bishops.

In 1352, debtors (who’d maxed out their MasterCards) became criminals, housed here among harder criminals in harsh conditions. Prisoners were not fed. They had to bribe guards to get food, to avoid torture, or even to gain their release. (The idea was that you’d brought this on yourself.) Prisoners relied on their families for money, prostituted themselves to guards and other inmates, or reached through the bars at street level, begging from passersby. Murderers, debtors, Protestants, priests, and many innocent people experienced this strange brand of justice...all part of the rough crowd that gave Bankside such a seedy reputation.

• Continuing west and crossing under the Cannon Street Bridge, just ahead and across the street is...

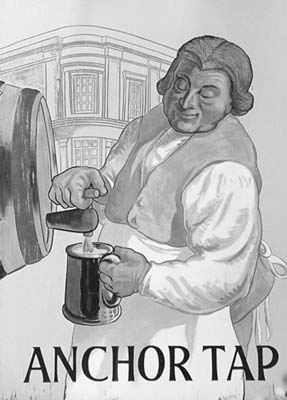

The Anchor and Bankside Road

The Anchor and Bankside Road

The Anchor is the last of the original 22 licensed “inns” (tavern/brothel/restaurant/nightclub/casino) of Bankside’s red light district heyday in the 1600s. A tavern has stood here for 800 years. The big brick buildings behind the inn were once part of the mass-producing Anchor brewery, with the inn as its brewpub. (Even back in the 1300s, Chaucer wrote, “If the words get muddled in my tale / Just put it down to too much Southwark ale.”)

In the cozy, mazelike interior are memories of greats who’ve drunk here (I have) or indulged in a new drug that hit London in the 1560s—tobacco. Shakespeare, who may have lived along Clink Street, may have tippled here, especially because the original Globe Theatre was right behind The Anchor (see map on here ). Dr. Samuel Johnson also worked here while writing the famous dictionary that helped codify the English language and spelling (for more on Dr. Johnson, see here ).

The Anchor marks the start of the once-notorious Bankside Road that runs along a river retaining wall. In Elizabethan times (16th century), the street was lined with “inns” offering one-stop shopping for addictive personalities. The streets were jammed with sword-carrying punks in tights looking for a fight, prostitutes, gaping tourists from the Borough High Street coaching inns, pickpockets, river pirates, highwaymen, navy recruiters kidnapping drunks, and many proper ladies and gentlemen who ferried across from The City for an evening’s entertainment. And then there were the really seedy people—yes, actors.

• Crossing under the green-and-yellow Southwark Bridge, notice the metal reliefs depicting London’s “Frost Fair” of 1564. Because the old London Bridge was such a wall of stone, the swift-flowing Thames would back up and even freeze over during cold winters. Emerging from under the bridge, head farther west on Bankside to...

Shakespeare’s Globe

Shakespeare’s Globe

All the world’s a stage,

And all the men and women merely players.

They have their exits and their entrances,

And one man, in his time, plays many parts.

—As You Like It

By 1599, 35-year-old William Shakespeare was a well-known actor, playwright, and businessman in the booming theater trade (see sidebar on here ). His acting company, the Lord Chamberlain’s Men, built the 3,000-seat Globe Theatre, by far the largest of its day (200 yards from today’s replica, where only a plaque stands now). The Globe premiered Shakespeare’s greatest works—Hamlet, Othello, King Lear, Macbeth —in open-air summer afternoon performances, though occasionally at night by the light of torches and buckets of tar-soaked ropes.

In 1612, it featured Shakespeare’s All Is True (Henry VIII). During Scene 4, a stage cannon boomed, announcing the arrival of King Henry, who started flirting with Anne Boleyn. As the two actors generated sparks onstage, play-watchers smelled fire. Some stray cannon wadding had sparked a real fire offstage. Within an hour, the wood-and-thatch building had burned completely to the ground, but with only one injury: A man’s pants caught fire and were quickly doused with a tankard of ale.

Built in 1997, the new Globe—round, half-timbered, thatched, with wooden pegs for nails—is a quite realistic replica, though slightly smaller (seating 1,500 spectators), located near the original site, and constructed with fire-repellent materials. Performances are staged almost nightly in summer—check at the box office (at the east end of the complex). For more on touring the Globe, see here .

Bankside’s theater scene vanished in the 1640s, closed by a Parliament dominated by hard-line Puritans. Drama seemed to portray and promote immoral behavior, and actors—men who also played women’s roles—parodied and besmirched fair womanhood. Bearbaiting was also outlawed by the outraged moralists (to paraphrase the historian Thomas Macaulay)—not because it caused bears pain, but because it gave people pleasure.

• From the Globe, belly up to the railing overlooking the Thames and imagine the view on September 2, 1666.

View of 1666 Great Fire Area

View of 1666 Great Fire Area

On Sunday, September 2, 1666, stunned Londoners quietly sipped beers in Bankside pubs and watched The City across the river go up in flames. (“When we could endure no more upon the water,” wrote Samuel Pepys in his diary, “we went to a little alehouse on the Bankside.”) Started in a bakery shop near the Monument (north end of London Bridge) and fanned by strong winds, the fire swept westward, engulfing the mostly wooden city, devouring Old St. Paul’s, and moving past what is now Blackfriars Bridge and St. Bride’s to Temple Church (near the pointy, black, gold-tipped steeple of the Royal Courts of Justice).

In four days, 80 percent of The City was incinerated, including 13,000 houses and 89 churches. The good news? Incredibly, only nine people died, the fire cleansed a plague-infested city, and Christopher Wren was around to rebuild London’s skyline.

The fire also marked the end of Bankside’s era as London’s naughty playground. Having recently been cleaned up by the Puritans, it now served as a temporary refugee camp for those displaced by the fire. And, with the coming Industrial Age, businessmen demolished the inns and replaced them with brick warehouses, docks, and factories to fuel the economy of a world power.

• At the pedestrian bridge is a towering former power plant, now turned into a huge modern art museum.

Tate Modern

Tate Modern

London’s large, impressive modern art collection is housed mostly in a former power station—typical of the move to renovate empty, ugly Industrial Age hulks on the South Bank. Even if you don’t tour the collection, pop inside the north entrance (free) to view the spacious interior, decorated each year with a new industrial-sized installation by one of the world’s top contemporary artists. As the Tate expands into a new annex (behind the building), it will be interesting to see what new spaces they open up to the public.

See the Tate Modern Tour chapter.

See the Tate Modern Tour chapter.

• End this walk on the Millennium Bridge, enjoying a view of the Thames.

Millennium Bridge and View of the Thames

Millennium Bridge and View of the Thames

This pedestrian bridge was built in 2000 to connect the Tate Modern with St. Paul’s Cathedral and The City. For its first two glorious days, Londoners made the pleasant seven-minute walk across...before the $25 million “bridge to the next millennium” started wobbling dangerously (insert your own ironic joke here) and was closed for rethinking. After much work, 20 months, and $8 million in retrofits, the bridge reopened. Nicknamed the “blade of light,” it was designed (partly by Lord Norman Foster, who also did The Gherkin and City Hall downstream) to allow a wide-open view of St. Paul’s. Now stabilized, it links two revitalized sections of London.

From the Cotswolds to the North Sea, the Thames winds eastward a total of 210 miles. London is close enough to the estuary to be affected by the North Sea’s tides, so the river level does indeed rise and fall twice a day. In fact, one of the reasons Romans found this a practical location—even though it was about 40 miles inland—was that their boats could hitch a free ride with the tides between the sea and the town twice a day. But tides also mean floods. After centuries of periodic flooding (spring rains plus high tides), barriers to regulate the tides were built in 1982, east of Tower Bridge. The barriers also slow down the once fast-moving river.

The Thames is still a major commercial artery (east of Tower Bridge). In the previous two centuries, it ran brown with Industrial Revolution pollution. Today it’s brown because of estuary silt—the Thames is now one of the cleanest rivers in the industrialized world.

• Your tour is over. From here you can enjoy the Tate Modern or continue strolling the South Bank (follow the Jubilee Walkway 20 minutes or so to the London Eye and Big Ben—particularly enjoyable in the evening). Or cross the Thames on the Millennium Bridge to a pedestrian mall that leads past the glassy Salvation Army headquarters (good café and small, free Salvation Army history display in daylight basement) to St. Paul’s Cathedral and Tube station.