1950s—AMERICA, THE GLOBAL SUPERPOWER

Remember the 20th century? Accelerated by technology and fragmented by war, it was an exciting and chaotic time, with art as turbulent as the world that created it. The Tate Modern lets you walk through the explosive last century with a glimpse at its brave new art.

This Is Not a “Tour”: The Tate Modern is (controversially) displayed by concept—“Poetry and Dream,” for example—rather than by artist and chronology. But unlike the museum, this chapter is neatly chronological. It’s not intended as a painting-by-painting guide, but to give context to the various cultural periods that produced the art of the Tate Modern.

Read through this chapter for a general introduction, use it as a reference, then take advantage of the Tate’s excellent multimedia guide to focus on specific works. With this background in 20th-century art, you’ll appreciate the Tate’s even greater strength: art of the 21st century.

Tate Modern Expansion: The Tate Modern opened in 2000, anticipating two million visitors a year. More than twice that number visit. In response, this wildly popular museum opened a new wing in 2016, doubling its exhibition space. The twisted-pyramid, 10-story addition—dubbed the Switch House—seems more like a completely new gallery than an annex. Besides showing off more of the Tate’s impressive collection, the new space hosts changing themed exhibitions, performance art, experimental film, and light, sound, and interactive sculpture. Higher floors offer social and educational activities, with a children’s gallery, several cafés, a top-floor wraparound terrace with stunning views of London, and a view restaurant. The goal of the expansion—to foster interaction between art and community in the 21st century—is as modern as the collection itself.

Cost: Free, £4 suggested donation; fee for special exhibits.

Hours: Daily 10:00-18:00, Fri-Sat until 22:00, last entry to special exhibits 45 minutes before closing.

When to Go: This popular place is especially crowded on weekends. Crowds thin out on Friday and Saturday evenings and midday during the week.

Getting There: Located on the South Bank of the Thames, across from St. Paul’s and near the Globe Theatre. You can get here by Tube, ferry, or foot:

By Tube: Take the Tube to Southwark, London Bridge, St. Paul’s, Mansion House, or Blackfriars, then follow signs to the museum (10- to 15-minute walk).

By Ferry: Catch Thames Clippers’ Tate Boat ferry from the Tate Britain for a 15-minute crossing (£7.50 one-way, £17.35 day ticket, discount with Travelcard or Oyster card, buy ticket at self-serve machines before boarding or use Oyster Card, departs every 40 minutes Mon-Fri from 10:00 to 16:30, Sat-Sun from 9:15 to 18:40, www.tate.org.uk/visit/tate-boat ).

On Foot: Walk across the Millennium Bridge from St. Paul’s Cathedral.

Information: The two lowest floors (levels 0 and 1) have the basic services: info desks, baggage check, bookstores, multimedia guide rentals, and tickets for temporary exhibits. The helpful staff at the info desk (level 1) can tell you the location of specific works. The floor plan (£1 suggested donation) is also useful. In addition, a few touch-screen computers are scattered throughout the museum. Tel. 020/7887-8888, www.tate.org.uk .

Tours: The £4.50 multimedia guide covers the entire permanent collection, and includes a tour geared for kids ages 8-12. Free 45-minute guided tours are offered at 11:00, 12:00, 14:00, and 15:00. Free 10-minute gallery talks take place Friday and Saturday (see info desk for details).

Length of This Tour: Allow at least an hour. Read this chapter ahead of time, then browse according to your tastes.

Cloakroom: Level 0 (free, £2 suggested donation).

Photography: Photos allowed without flash.

Cuisine Art: View coffee shops are on levels 1 and 3. On level 6, there’s a $$$$ table-service restaurant (£15 afternoon tea served 15:00-17:30, until 17:00 Fri-Sun); the $$ casual bar offers better views and lower prices (drinks and snacks). This perch provides stunning panoramas of St. Paul’s and The City. The $$$$ 11th-floor restaurant in the museum’s new building promises another fine dining experience. Some trendy restaurants are several blocks southwest of the Tate, along the street named “the Cut” (near Southwark Tube stop).

Starring: Picasso, Matisse, Dalí, and all the “classic” modern artists, plus the Tate Modern’s specialty—British and American artists of the last half of the 20th century.

Know Your Tates: Don’t confuse the Tate Modern with the Tate Britain (south of Big Ben), which features British art.

Even though the layout of the Tate Modern changes constantly, the collection’s focus is the same: the 20th-century postwar period. Don’t just come to see the Old Masters of Modernism (Matisse, Picasso, Kandinsky, and so on). Push your mental envelope with works by Pollock, Miró, Bacon, Picabia, Beuys, Twombly, and others.

More modern art from British artists is on display at the Tate Britain museum ( see the Tate Britain Tour chapter).

see the Tate Britain Tour chapter).

Reminder: The following is not a painting-by-painting tour but rather a chronological overview of the modern art movement as a whole.

• Start at the main entrance (on the west side of the building). To reach it from the river: With the Thames at your back, walk to the right around the corner of the building, down the slope and into the massive empty space of the former electricity-generating powerhouse.

This huge, grand entrance usually dwarfs the art it houses (a metaphor for the triumph of 20th-century technology, perhaps?). The Turbine Hall displays major art installations by contemporary artists—always one of the highlights of the art world.

You’re on underground level 0 (the riverfront entrance leads to level 1). To see the core of the permanent collection—and the artwork described in this chapter—head upstairs (via the escalator near the ground-floor cloakroom) to levels 2 through 4.

Paintings are arranged according to theme, not artist. Paintings by Picasso, for example, are scattered all over the building. Special exhibits are often on levels 2 and 3.

Anno Domini 1900, a new century dawns. Europe is at peace, Britannia rules the world. Technology is about to usher in a golden age.

Monet (1840-1926) captures the relaxed, civilized spirit of belle époque France and Victorian England with Impressionist snapshots of peaceful landscapes and middle-class family picnics. But the true subject is the shimmering effect of reflected light, rendered with rough brushstrokes and bright paints that look messy up close but blend at a distance. The newfangled camera made camera-eye realism obsolete. Artists began placing more importance on how something was painted rather than on what was painted.

Europe ruled a global empire, tapping its dark-skinned colonies for raw materials, cheap labor, and bold new ways to look at the world. The cozy Victorian world was shattering. Nietzsche murdered God. Darwin stripped off Man’s robe of culture and found a naked ape. Primitivism was modern. Ooga-booga.

Matisse (1869-1954) was one of the Fauves, or “wild beasts,” who tried to inject a bit of the jungle into civilized European society. Inspired by “primitive” African and Oceanic masks and voodoo dolls, the Fauves made modern art that looked primitive: long, masklike faces with almond eyes; bright, clashing colors; simple figures; and “flat,” two-dimensional scenes.

Matisse simplifies. A man is a few black lines and blocks of paint. A snail is a spiral of colored paper. A woman’s back is an outline. Matisse’s colors are unnaturally bright. The “distant” landscape is as crisp and clear as close objects, and the slanted lines meant to suggest depth are crudely done.

Traditionally, the canvas was like a window that you looked “through” to see a slice of the real world stretching off into the horizon. With Matisse, you look “at” the canvas like you do wallpaper—to appreciate the decorative pattern of colors and shapes.

Though his style is modern, Matisse builds on 19th-century art—the bright colors of Van Gogh, the primitive figures of Gauguin, the colorful designs of Japanese wood-block prints, and the Impressionist patches of paint that blend together only at a distance.

Cézanne (1839-1906) brings Impressionism into the 20th century. Whereas Monet uses separate dabs of different-colored paint to “build” a figure, Cézanne “builds” a man with somewhat larger slabs of paint, giving him a kind of 3-D chunkiness. It’s not hard to see the progression from Monet’s dabs to Cézanne’s slabs to Picasso’s cubes—Cubism.

The modern world was moving fast, with automobiles, factories, and mass communication. Motion pictures captured the fast-moving world, while Einstein explored the fourth dimension: time.

Born in Spain, Picasso (1881-1973) moved to Paris as a young man. He worked with painter and sculptor Georges Braque in poverty so dire they often didn’t know where their next bottle of wine was coming from.

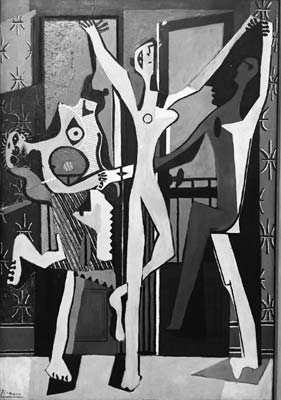

Picasso’s Cubist works show the old European world shattering to bits. He pieces the fragments back together in a whole new way, showing several perspectives at once (for example, looking up the left side of a woman’s body and, at the same time, down at her right).

Whereas newfangled motion pictures capture several perspectives in succession, Picasso achieves it on a canvas with overlapping images. A single “cube” might contain an arm (in the foreground) and the window behind (in the background), both painted the same color. The foreground and background are woven together so that the subject dissolves into a pattern.

Picasso, the most famous and—OK, I’ll say it—the greatest artist of the 20th century, constantly explored and adapted his style to new trends. He made collages, tried his hand at “statues” out of wood, wire, or whatever, and even made art out of everyday household objects. These multimedia works, so revolutionary at the time, have become stock-in-trade today. Scattered throughout the museum are works from the many periods of Picasso’s life.

The Machine Age is approaching, and the whole world gleams with promise in cylindrical shapes (“Tubism”), like an internal-combustion engine. Or is it the gleaming barrel of a cannon?

A soldier—shivering in a trench, ankle-deep in mud, waiting to be ordered “over the top,” to run through barbed wire, over fallen comrades, and into a hail of machine-gun fire, only to capture a few hundred yards of meaningless territory that would be lost the next day. This soldier was not thinking about art.

World War I left nine million dead. (At times, England lost more men per month than America lost during the entire Vietnam War.) The war also killed the optimism and faith in humankind that had guided Europe since the Renaissance.

Cynicism and decadence settled over postwar Europe. Artists such as Grosz, Beckmann, and Kokoschka “expressed” their disgust by showing a distorted reality that emphasized the ugly. Using the lurid colors and simplified figures of the Fauves, they slapped paint on in thick brushstrokes, depicting a hypocritical, hard-edged, dog-eat-dog world—a civilization watching its Victorian moral foundations collapse.

When they could grieve no longer, artists turned to grief’s giddy twin, laughter. The war made all old values a joke, including artistic ones. The Dada movement, choosing a purposely childish name, made art that was intentionally outrageous: a moustache on the Mona Lisa, a shovel hung on the wall, or a modern version of a Renaissance “fountain”—a urinal (by Marcel Duchamp...or was it I. P. Freeley?).

Dada was a dig at all the pompous prewar artistic theories based on the noble intellect of Rational Women and Men. While the experts ranted on, Dadaists sat in the back of the class and made cultural fart noises.

Hey, I love this stuff. My mind says it’s sophomoric, but my heart belongs to Dada.

In the Jazz Age, the world turned upside down. Genteel ladies smoked cigarettes. Gangsters laid down the law. You could make a fortune in the stock market one day and lose it the next. You could dance the Charleston with the opposite sex, and even say the word “sex” while talking about Freud over cocktails. It was almost...surreal.

Artists caught the jumble of images on a canvas. A telephone made from a lobster, an elephant with a heating-duct trunk, Venus sleepwalking among skeletons. Take one mixed bag of reality, jumble it in a blender, and serve on a canvas—Surrealism.

The artist scatters seemingly unrelated—yet easily recognizable—objects on the canvas, leaving us to trace the connections in a kind of connect-the-dots without numbers.

Further complicating the modern world was Freud’s discovery of the “unconscious” mind, which thinks dirty thoughts while we sleep. Surrealists let the id speak. The canvas is an uncensored, stream-of-consciousness “landscape” of these deep urges, revealed in the bizarre images of dreams. Salvador Dalí, the most famous Surrealist, combined an extraordinarily realistic technique with an extraordinarily twisted mind. He painted “unreal” scenes with photographic realism, making us believe they could really happen. Dalí’s images—crucifixes, political and religious figures, and naked bodies—pack an emotional punch.

As capitalism failed around the world, governments propped up their economies with vast building projects. The architecture style was modern, stripped-down (i.e., cheap), and functional. Propagandist campaigns championed noble workers in the heroic Social Realist style.

Like blueprints for modernism, Mondrian’s T-square style boils painting down to its basic building blocks: a white canvas, black lines, and the three primary colors—red, yellow, and blue—arranged in orderly patterns. (When you come right down to it, that’s all painting ever has been. A schematic drawing of, say, the Mona Lisa shows that it’s less about a woman than about the triangles and rectangles she’s composed of.)

Mondrian (1872-1944) started out painting realistic landscapes of the orderly fields in his native homeland of Holland. Increasingly, he simplified his style into horizontal and vertical patterns. For Mondrian, who was heavily into Eastern mysticism, “up versus down” and “left versus right” were the perfect metaphors for life’s dualities: good versus evil, body versus spirit, fascism versus communism, man versus woman. The canvas is a bird’s-eye view of Mondrian’s personal landscape.

World War II was a global war (involving Europe, the Americas, Australia, Africa, and Asia) and a total war (saturation bombing of civilians and ethnic cleansing). It left Europe in ruins.

Alberto Giacometti’s skinny statues have the emaciated, haunted, and faceless look of concentration-camp survivors. In the sweep of world war and overpowering technology, man is frail and fragile. All he can do is stand at attention and take it like a man.

Meanwhile, Francis Bacon’s caged creatures speak for all of war-torn Europe when they scream, “Enough!” (For more on Bacon, see here .)

As converted war factories turned swords into kitchen appliances, America helped rebuild Europe while pumping out consumer goods for its own booming population. Prosperity, a stable government, national television broadcasts, and a common fear of Soviet communism threatened to turn America into a completely homogeneous society.

Some artists, centered in New York, rebelled against conformity and superficial consumerism. (They’d served under Eisenhower in war and now had to in peace, as well.) They created art that was the very opposite of the functional, mass-produced goods of the American marketplace.

Art was a way of asserting your individuality by creating a completely original and personal vision. The trend was toward bigger canvases, abstract designs, and experimentation with new materials and techniques. It was called “Abstract Expressionism”—expressing emotions and ideas using color and form alone.

“Jack the Dripper” attacks convention with a can of paint, dripping and splashing a dense web onto the canvas. Picture Pollock (1912-1956) in his studio, jiving to the hi-fi, bouncing off the walls, throwing paint in a moment of enlightenment. Of course, the artist loses some control this way—over the paint flying in midair and over himself in an ecstatic trance. Painting becomes a whole-body activity, a “dance” between the artist and his materials.

The intuitive act of creating is what’s important, not the final product. The canvas is only a record of that moment of ecstasy.

With all the postwar prosperity, artists could afford bigger canvases. But what reality are they trying to show?

In the modern world, we find ourselves insignificant specks in a vast and indifferent universe. Every morning, each of us must confront that big, blank, existential canvas, and decide how we’re going to make our mark on it.

Another influence was the simplicity of Japanese landscape painting. A Zen master studies and meditates for years to achieve the state of mind in which he can draw one pure line. These canvases, again, are only a record of that state of enlightenment. (What is the sound of one brush painting?)

On more familiar ground, postwar painters were following in the footsteps of artists such as Mondrian. The geometrical forms here reflect the same search for order, but these artists painted to the musical 5/4 asymmetry of the Dave Brubeck Quartet’s jazzy Take Five.

Enjoy the lines and colors, but also a new element: texture. Some works have very thick paint piled on, where you can see the brushstrokes clearly. Some have substances besides paint applied to the canvas, or the canvas is punctured so the fabric itself (and the hole) becomes the subject. Artists show their skill by mastering new materials. The canvas is a tray, serving up a delightful buffet of different substances with interesting colors, patterns, shapes, and textures.

Rothko (1903-1970) made two-toned rectangles, laid on their sides, that seem to float in a big, vertical canvas. The edges are blurred, so if you get close enough to let the canvas fill your field of vision (as Rothko intended), the rectangles appear to rise and sink from the cloudy depths like answers in a Magic 8 Ball.

Serious students appreciate the subtle differences in color between the rectangles. Rothko experimented with different bases for the same color and used a single undercoat (a “wash”) to unify them. His early works are warmer, with brighter reds, yellows, and oranges; his later works are maroon and brown, approaching black.

Still, these are not intended to be formal studies in color and form. Rothko was trying to express the most basic human emotions in a pure language. (A “realistic” painting of a person is inherently fake because it’s only an illusion of the person.) Staring into these windows onto the soul, you can laugh, cry, or ponder, just as Rothko did when he painted them.

Rothko, the previous century’s “last serious artist,” believed in the power of art to express the human spirit. When he found out that his nine large Seagram canvases were to be hung in a corporate restaurant, he refused to sell them, and they ended up in the Tate. (A 2010 Tony Award-winning play called Red dealt with Rothko’s anguished decision.)

In his last years, Rothko’s canvases—always rectangles—got bigger, simpler, and darker. When Rothko finally slashed his wrists in his studio, one nasty critic joked that what killed him was the repetition. Minimalism was painting itself into a blank corner.

The decade began united in idealism—young John F. Kennedy pledged to put a man on the moon, newly launched satellites signaled a united world, the Beatles sang exuberantly, peaceful race demonstrations championed equality, and the Vatican II Council preached liberation. By decade’s end, there were race riots, assassinations, student protests, and America’s floundering war in distant Vietnam. In households around the world, parents screamed, “Turn that down...and get a haircut!”

Culturally, every postwar value was questioned by a rising, wealthy, and populous baby-boom generation. London—producer of rock-and-roll music, film actors, mod fashions, and Austin Powers joie de vivre—once again became a world cultural center.

Though government-sponsored public art was dominated by big, abstract canvases and sculptures, other artists pooh-poohed the highbrow seriousness of abstract art. Instead, they mocked lowbrow popular culture by embracing it in a tongue-in-cheek way (Pop Art), or they attacked authority with absurd performances to make a political statement (conceptual art).

America’s postwar wealth made the consumer king. Pop Art is created from the popular objects of that throwaway society—soup cans, car fenders, tacky plastic statues, movie icons. Take a Sears product, hang it in a museum, and you have to ask: Is this art? Are mass-produced objects beautiful, or crap? Why do we work so hard to acquire them? Pop Art, like Dadaism before it, questions our society’s values.

Andy Warhol (who coined “15 minutes of fame”) concentrated on another mass-produced phenomenon: celebrities. He took publicity photos of famous people and reproduced them. The repetition—like the constant bombardment we get from recurring images on TV—cheapens even the most beautiful things.

Roy Lichtenstein took a comic strip, blew it up, hung it on a wall, and charged a million bucks—whaam, Pop Art. Lichtenstein supposedly was inspired by his young son, who challenged him to do something as good as Mickey Mouse. The huge newsprint dots never let us forget that the painting—like all commercial art—is an illusionistic fake. The work’s humor comes from portraying a lowbrow subject (comics and ads) on the epic scale of a masterpiece.

Optical illusions play tricks with your eyes, the way a spiral starts to spin when you stare at it. These obscure scientific experiments in color, line, and optics suddenly became trendy in the psychedelic ’60s.

All forms of authority—“The Establishment”—seemed bankrupt. America’s president resigned in the Watergate scandal, corporations were polluting the earth, and capitalism nearly ground to a halt when Arabs withheld oil.

Artists attacked authority and institutions, trying to free individuals to discover their full human potential. Even the concept of “modernism”—that art wasn’t good unless it was totally original and progressive—was questioned. No single style could dictate in this postmodern period.

Fearing for the health of the earth’s ecology, artists rediscovered the beauty of rocks, dirt, trees, even the sound of the wind, using them to create natural art. A rock placed in a museum or urban square is certainly a strange sight.

The Tate Modern’s collection of “sculptures” by Joseph Beuys—assemblages of steel, junk, wood, and, especially, felt and animal fat—only hint at his greatest artwork: Beuys himself.

Imagine Beuys walking through the museum, carrying a dead rabbit, while he explains the paintings to it. Or taking off his clothes, shaving his head, and smearing his body with fat.

This charismatic, ex-Luftwaffe art shaman did ridiculous things to inspire others to break with convention and be free. He choreographed “Happenings”—spectacles where people did absurd things while others watched—and pioneered performance art, in which the artist presents himself as the work of art. Beuys inspired a whole generation of artists to walk on stage, cluck like a chicken, and stick a yam up themselves. Beuys will be Beuys.

Minimalist painting and abstract sculpture were old hat, and there was an explosion of new art forms. Performance art was the most controversial, combining music, theater, dance, poetry, and the visual arts. New technologies brought video, assemblages, installations, artists’ books (paintings in book form), and even (gasp!) realistic painting.

Increasingly, artists are not creating an original work (painting a canvas or sculpting a stone) but assembling one from premade objects. The concept of which object to pair with another to produce maximum effect (“Let’s stick a crucifix in a jar of urine,” to cite one notorious example) is the key.

Ronald Reagan in America, Margaret Thatcher in Britain, and corporate executives around the world ruled over a conservative and materialistic society. On the other side were starving Ethiopians, gay men with the new disease AIDS, people of color, and women—all demanding power. Intelligent, peaceful, straight white males assumed a low profile.

The art world became big business, with a Van Gogh painting fetching $54 million. Corporations paid big bucks for large, colorful, semi-abstract canvases. Marketing became an art form. Gender and sexual orientation were popular themes. Many women picked up paintbrushes, creating bright-colored abstract forms hinting at vulva and penis shapes. Visual art fused with popular music, bringing us installations in dance clubs and fast-edit music videos. The crude style of graffiti art demanded to be included in corporate society.

The communist-built Berlin Wall was torn down, ending four decades of a global Cold War between capitalism and communism. The new battleground was the “Culture Wars,” the struggle to include all races, genders, and lifestyles within an increasingly corporate-dominated, global society.

Artists looked to Third World countries for inspiration and championed society’s outsiders against government censorship and economic exclusion. A new medium, the Internet, arose, allowing instantaneous multimedia communication around the world through electronic signals carried by satellites and telephone lines.

A new millennium dawned. Thanks to the Internet, art has taken on a new sense of connectivity. A work of art can mean strangers meeting for intricate “Flashmob” street performances; graffiti artists like Banksy reaching the masses by tagging public spaces; and people everywhere “sharing” moments through social networking sites. “Selfies” have become the modern Gainsborough portrait, presenting an idealized image to the world of how we wish to be seen. Technology has empowered everyone to make art...only instead of a paintbrush, we use selfie-sticks.