It has been a common assumption, in this century if not the last, that New Zealand’s race relations have been better than those of Australia, the United States, or South Africa. Indeed a recent article by a leading New Zealand historian accepted this as an axiom and simply went on to ask why.

1 As has often been pointed out, there has been since the turn of the century, and especially since 1920, a Maori renaissance marked by considerable improvements in the demographic, social, and economic status of the Maoris. Such improvements have provided the opportunity for much self-congratulation. New Zealand’s “success” in handling the “natives” at home was used by Premier Richard J. Seddon at the beginning of the century to justify demands for empire in the South Pacific. More recent foreign policy statements relating to racial conflicts abroad have commonly been prefaced by complacent reference to amicable race relations at home.

There is substance in all these assumptions, but they need to be qualified. Visiting observers, who have taken rather more trouble to discover Maori attitudes than the average Pakeha (European) New Zealander takes in a lifetime, have commonly found considerable friction and unease. In 1937 Dr. S. M. Lambert, representative in the South Pacific of the Rockefeller Foundation, observed that “the general conception that New Zealand is tolerant of coloured races, in my opinion is not true. The average N.Z.er rarely sees a Maori; in the large centers he rarely appears. When one goes out in a Maori district one finds the same racial antagonism as is found in other countries when a coloured race becomes familiar and competitive and has a lower standard of living.”

2 More recent visitors like Robin W. Winks and David P. Ausubel have made similar comments.

3 In a qualitative situation of considerable complexity, it is not possible to make definitive judgments. New Zealand race relations are not necessarily better than

those in other countries, though they do have some different characteristics.

This essay, like most discussions of race relations in New Zealand, is confined to the indigenous Maori and immigrant Pakeha communities, and even in this context it is far from exhaustive. Owing to a rigid—and successfully disguised—white New Zealand immigration policy, non-European immigration has been severely restricted, except for a slight influx of island Polynesians since 1945.

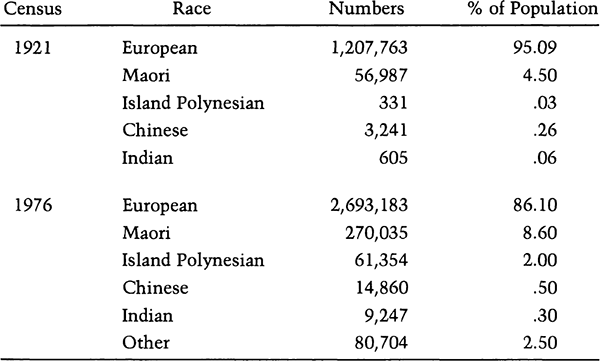

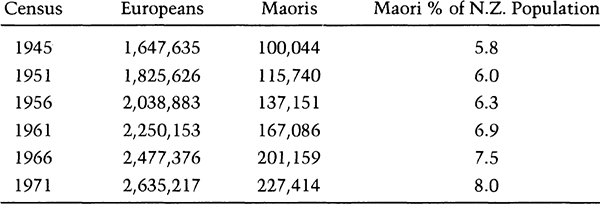

4 The insignificance of non-Polynesian ethnic minorities within the total population is clearly revealed by

table 1.

5 The fact that New Zealand has admitted, though scarcely encouraged, immigration from existing and former colonial territories of the South Pacific has enabled it to escape some of the opprobrium heaped on Australia for continuing to operate a white immigration policy; but New Zealand’s policy can hardly continue unmodified. The European preponderance within the New Zealand population is slowly decreasing and will continue to do so.

Nineteenth-Century Heritage

New Zealand began its history as a British colony on a wave of humanitarian idealism.

6 This was reflected in the Treaty of Waitangi of 1840, with its promise to respect the Maoris’ rights to land and to grant them the rights and privileges of British subjects. It was hoped that the rights of the Maoris could be reconciled with the needs of colonization and that the two races could be amalgamated—in effect, that the Maoris could be assimilated into European civilization. The ideal was in many ways naive and overoptimistic. Rapid European colonization soon provoked bitter disputes over land, with sporadic fighting in the 1840s and more widespread war in the 1860s. British troops were needed to break the back of Maori resistance, though after 1865 it was possible to rely on colonial militia supported by Maori auxiliaries. The colonists were granted a representative constitution in 1852, a large measure of internal self-government in 1856, and control over native affairs in 1861. They lost no time in turning this power, and the fruits of military victory, to their advantage. Under the New Zealand Settlements Act of 1863, they confiscated some three million acres of land belonging to “rebel” tribes (subsequently about half of this was paid for or returned). Under the Native Lands Acts of 1862 and 1865, they abolished the Crown’s right of

preemption, laid down in the Treaty of Waitangi, and allowed settlers to purchase land directly from Maori owners, after a Native Land Court had adjudicated and individualized the Maori titles. The land acts initiated an era of “free trade” in Maori land in which the greater part of the North Island passed into European hands.

7 By 1900 the Maori estate in the North Island had been reduced from some twenty-eight to seven million acres, and this area was to be halved in the twentieth century. The confiscation and “free trade” in Maori lands were carried out in an often unscrupulous manner that has left a legacy of bitterness.

TABLE 1. RACIAL PERCENTAGES IN NEW ZEALAND POPULATION

SOURCE: New Zealand census returns.

Though the land legislation of the 1860s was designed primarily to facilitate the needs of European colonization, it was also regarded as an essential part of a larger policy, the amalgamation of the races—the colonial legislators remained heirs to the imperial civilizing mission. Anxious to bring Maoris and their land within the authority of colonial law, they were willing to concede in return that Maoris should have the rights and privileges of British subjects, including the right to appeal to the courts (clarified in the Native Rights Act, 1865) and the right to elect four members of Parliament (the Native Representation Act, 1867). Provision was made for village schools in 1867, and there were spasmodic attempts to provide medical assistance. But this was

about as far as nineteenth-century politicians, wedded to laissez faire principles, would go in providing aid. They assumed that European civilization would catch on like a benevolent infection.

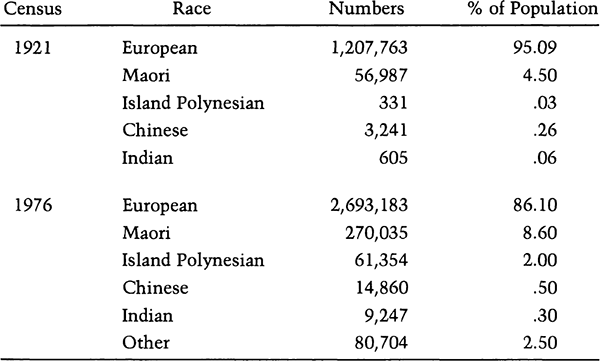

In fact, contact with Europeans was proving to be a mixed blessing, indeed was very nearly fatal for Maoris. The alienation of their land was often accompanied by prolonged social dislocation and dissipation. There was little opportunity and no assistance to farm the land that they retained. And European diseases continued to reduce the Maori population. It was not until the turn of the century that the trend was reversed (see

table 2).

The twentieth-century revival was facilitated by improved living conditions, the development of resistance to disease, increased government assistance especially in the field of health, a slowing down of land acquisition, and vigorous new Maori leadership.

8 Notable here was the work of James Carroll, the half-Maori minister of native affairs from 1899 to 1912, and several young Maori graduates he brought into public life, including the medical graduates Maui Pomare and Peter Buck, who led the Maori hygiene division of the newly created Department of Health, and Apirana Ngata, a graduate in arts and law, whose main work lay in land development and tenure reform. On their entry into Parliament, these men formed what has been called the Young Maori party. Their work in promoting a Maori renaissance is well known, but it is worth adding that they could hardly have succeeded without the sympathetic support from Maori communities in which the old leadership, still smarting under nineteenth-century grievances, was giving way to younger, better educated men and without at least some support from a European legislature rather more sympathetic to Maori welfare than it had been in the past.

Yet the Maori revival had hardly got under way when New Zealand became involved in the First World War. Pomare and Ngata organized a contingent of Maori volunteers, and Buck resigned his seat in Parliament to accompany it as medical officer. Nevertheless, there was strong resistance to volunteering in Maori districts that had been involved in the wars of the 1860s, and just before the war ended conscription was introduced to catch Maori draft dodgers. Here was a reminder that racial animosities of the nineteenth century were still alive. But the fact that many Maoris had answered the call and fought with distinction at Gallipoli and in France meant that they could not be ignored in the postwar years.

TABLE 2. M

AORI P

ERCENTAGES OF N

EW Z

EALAND P

OPULATION

SOURCE: New Zealand census returns.

Between the World Wars

The interwar years were marked in New Zealand, as elsewhere, by economic uncertainty, giving way in 1929 to acute depression and in the late 1930s to a slow recovery. In the circumstances race relations were bound to come under strain, though the Maori people were not sufficiently integrated into the economy to offer serious competition with unemployed Europeans for jobs and benefits. During the worst of the depression, Europeans suffered a fall in their standard of living, but some Maoris achieved an advance as a result of land development. Indeed, there was such an improvement in the Maori condition that one historian has felt inclined to describe the interwar period, not the years before the First World War, as the time of the Maori renaissance.

9At the beginning of the period, however, the Maori revival suffered a severe check. The influenza epidemic of 1918–1919 caused far more Maori than Pakeha casualties: among the Maoris a death rate of 22.6 percent compared with 4.9 percent for Europeans.

10 To add to their disillusion Maori exservicemen found that they were not provided with the generous rehabilitation assistance that was granted European exservicemen.

11 Disgruntled and bewildered, many Maoris began to turn away from the Young Maori party to the faith healer and prophet, T. W. Ratana.

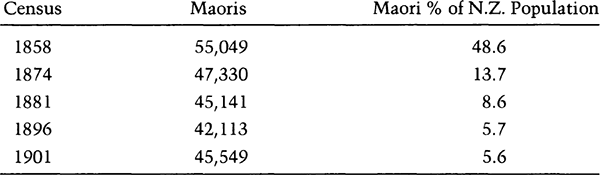

Despite the setback of the influenza epidemic, Maori population recovery was rapid: from about 1926 Maoris were increasing more rapidly than Europeans and becoming a slightly larger segment of the total population (see

table 3).

Prewar census figures had been greeted with some skepticism. Some held that the Maori populations was not really increasing, merely that the enumeration was becoming more effective. But

by 1926 there was no doubt that the numbers of Maoris were on the rise. As one senior official patronizingly remarked, “It is satisfactory to know that such a noble race is not dying out as we feared.”

12 In the circumstances it was no longer possible to justify continued acquisition of Maori land. By 1920 the land in Maori ownership had been reduced to about nineteen acres per head—much of this was remote, rugged, and bush-clad—and there was a danger of Maori paupers becoming a burden on the state. It was indeed a good time to call on the state to assist Maori land development. And this time there was likely to be a more sympathetic European response, since J. G. Coates, who had taken over the portfolio of Native Affairs in 1921 and retained it when he became prime minister in 1925, was more ready to heed Maori demands than his predecessor had been.

TABLE 3. MAORI PERCENTAGES OF NEW ZEALAND POPULATION

SOURCE: New Zealand census returns. The 1931 census was abandoned as an economy measure.

Equally important, Coates was prepared to investigate Maori grievances resulting from nineteenth-century acquisition of Maori land. In the 1920s several commissions of inquiry were appointed; the most important was the royal commission appointed in 1926 to examine the confiscations of the 1860s. This commission’s powers were limited because it could recommend only monetary compensation, not the return of unjustly confiscated land. The commission reported in 1928

13 that all the confiscations except one (at Tauranga where most of the land had been returned) had been unjust or excessive. It recommended that the government pay in perpetuity the sum of $NZ 10,000 per annum to the Taranaki tribes, $NZ 6,000 per annum to the Waikato tribes, and $NZ 600 per annum (plus a lump sum of $NZ 40,000) to the Whakatohea of Whakatane. The recommendations were accepted by the Coates government and by all the tribes except the Waikato, who, after prolonged negotiations, eventually accepted an offer by the Labour government in the 1940s to raise the compensation to that

paid to the Taranaki. At the time the compensation seemed reasonable enough, though inflation has long since eroded its value. Yet it was not so much the money that counted but the final admission by Pakehas that the confiscations had been unjust; this considerably improved the climate of race relations and facilitated cooperation over land development.

There had already been considerable progress in land development, much of it inspired by Ngata.

14 Working first among his Ngatiporou tribe of the East Coast, he had started two major land reforms before the war. First, there was the system known as incorporation, whereby large blocks of land still in multiple ownership were taken over and farmed as single units by committees of owners who in turn employed an experienced manager (often, for a start, a European) and used Maori labor, selected from those who had an interest in the block. The incorporations had many of the characteristics of a limited liability company and could provide more security for credit than the individual holders would have been able to offer. The system proved particularly effective on the East Coast, where most of the land was suitable for extensive pastoralism and needed to be farmed in large units, but it also could be applied to other activities like forestry. Ultimately, some three hundred incorporations were formed.

Ngata’s other land reform was known as consolidation; it was a gathering together in contiguous holdings of an individual’s fragments of land which hitherto had been dispersed throughout tribal lands. Consolidation of land into individual family holdings was desirable where the land was suitable for dairying. At first Ngata used a laborious process of mutually exchanging fragments. That could be effective with his own tribe but was unlikely to work with others. After the war the procedure was simplified by merely listing on paper the value of each individual’s land rights and apportioning these as consolidated holdings. To be effective this new system had to be operated on a large scale; if possible, all tribal lands needed to be consolidated in one operation. The new system was first applied to the Urewera tribe in 1922 and then, as Ngata was able to assemble teams of consolidators, to other tribes later in the 1920s.

Incorporation and consolidation needed to be accompanied by the development of land and effective farming. State resources had long been used to assist European farmers, notably in the use of cheap credit; therefore, Ngata was determined that Maoris should have a similar benefit. In the mid-1920s he promoted dairy farming

on the Consolidated holdings in the fertile Waiapu valley of the Ngatiporou country. He established a cooperative dairy factory, owned by the farmers, to process and market their produce. In 1926 he invited Coates to inspect the farms; the prime minister was so impressed that he agreed to advance Maori Land Board funds for land development before titles had been consolidated.

In 1928 Coates’s Reform party lost office. In the new United government, Ngata became minister of native affairs. He used state funds for a rapidly expanding Maori land-development program and continued to increase expenditures, despite cutbacks in spending in other departments in response to the deepening depression. By the end of 1931, when the economy was in dire straits, Ngata had commenced thirty-nine land-development schemes, covering over half a million acres. In 1929–1930 $NZ 13,022 was spent on Maori land development; by 1935–1936 the sum had increased to $NZ 558,020.

15 In his haste to press ahead, Ngata took personal control of most of the schemes, cut through departmental red tape (even if it meant ignoring set procedures of accounting), and did not hesitate to fire European farm supervisors who could not get on with local Maori leaders. There was much press criticism of Ngata’s “high-handed” methods and, when this was joined by the Departments of the Treasury and the Auditor-General, Prime Minister George Forbes gave way and set up a commission of inquiry. The commission reported in 1934 to the effect that Ngata had ignored proper civil service procedures, had used state funds in the interests of his tribe, and had allowed departmental supplies and vehicles to be used for private purposes. The report also stated that some of his subordinates had been involved in fraud.

16 Ngata accepted responsibility for the disclosures and resigned office. His colleagues were forced to follow suit a year later, having suffered resounding defeat at the polls, and the Labour party, which had relentlessly criticized Ngata, took over.

Labour, however, was content to accept, indeed to expand, Ngata’s land-development schemes. By 1939 some 840,000 acres had been put under development at a budgeted cost of $NZ 1,350,000 for Maori land development. Some 1,900 farmers had been established on holdings, and another 3,000 were employed as farm workers.

17 But it had now become evident that Maori land development could no longer provide a livelihood for the bulk of the rapidly increasing Maori population. Already there was a significant urban movement—by 1936 11.2 percent of the Maori population was described in the census as living in urban areas—and this process was to

be accelerated during the Second World War. Labour had also begun to deal with the urgent problem of Maori housing—according to the 1936 census 71 percent of Maori houses were either inadequate shacks or grossly overcrowded

18—by making loans available on easy repayment terms or building rental houses. The comprehensive free medical and social security benefits which Labour introduced in 1938 were, with the exception of some pensions and widows’ benefits, made available to Maoris on the same basis as to Europeans. These, with the fuller employment which followed from the returning prosperity in the late 1930s, meant a considerable improvement in the Maori standard of living.

Such improvements in the conditions of the Maoris seemed to indicate that they were being steadily integrated into the European economy and that the two races were gradually being amalgamated. The trend seemed to be confirmed by several studies of acculturation which were carried out in this period. F. M. Keesking’s

The Changing Maori (1928) and the penultimate chapter of Raymond Firth’s

Primitive Economics of the New Zealand Maori (1929) are typical examples. Firth’s applied anthropology tended to regard acculturation as a unilinear process of Europeanization. The discussion of recent Maori history—Firth called this latest period “The Acceptance of European Standards”

19—was confined mainly to Maori material progress and the work of the Young Maori party. But that was somewhat misleading, since the renaissance was as much a revival of Maori culture as it was an adaptation of European standards and economic techniques. Ngata certainly wanted Maoris to adopt European methods of farming; but they were to do so within a Maori context and, wherever possible, under Maori leadership. And, far from allowing modernization to promote detribalization, Ngata wanted to transform the old tribal animosities into peaceful competition in land development, cultural activities, and sport. Beyond the tribe there was a rather vague concept of a Maori nation, variously expressed as the Maori people, the race, the

iwi,

20 and the oft-repeated exhortation, first voiced by Carroll in 1920, “to hold fast to Maoritanga.” Carroll said that it would be for others to define this term—“to give it hands and give it feet”

21—and it has generally been equated with “Maoriness.” Maoritanga has been promoted in various ways: by the preservation of Maori language; by the performance, recording, translation, and publication of Maori myths, legends, songs, poetry, and dances; by the perpetuation of arts and crafts; by the

construction of meetinghouses and the preservation of

marne, as focal points for ceremonial; by the continuation of

tangihanga (funeral wakes),

hui (feasts), and

korero (speechmaking). Leaders of the Young Maori party, particularly Ngata, were active in promoting all these kinds of Maoritanga.

Yet it would be misleading to concentrate solely on the work of the giants of the Young Maori party, as tended to be the case with books and articles published in the interwar period. It was common to ignore other groups, notably the Ratana movement.

22 Founded by the faith healer, T. W. Ratana, in 1918, the movement soon began to attract adherents from the established, European-controlled churches, though these, with the exception of the Methodists, were soon to break with Ratana on doctrinal grounds. Unperturbed, Ratana went on to found his own church, which was duly registered in 1925. The Anglicans quickly conceded Maori demands for a Maori bishop by appointing F. A. Bennett, a member of a prominent Anglo-Maori family, as bishop of Aotearoa in 1927, and other churches began to devote more attention to Maori mission activities. The Ratana spiritual tide was stemmed; though formal membership in the Ratana church continued to increase until about the mid-1930s, it did not exceed 20 percent of the Maori population.

23Ratana’s political influence was to be far more profound. From the beginning, he had represented himself as the savior of the

morehu, the dispossessed ones. In 1924 he took a petition to King George V urging the settlement of Maori land grievances and the ratification of the Treaty of Waitangi. Like previous Maori petitioners, Ratana was politely referred back to the New Zealand Parliament, a reminder that he had to enter the New Zealand political arena if he were to have any influence. Though he did not stand for Parliament, he announced in 1928 that his candidates would capture the Four Quarters—the four Maori electorates. That prophecy was steadily fulfilled: in 1932 Eruera Tirikatene captured Southern Maori for Ratana; Western Maori followed in 1935; Northern Maori in 1938; and Eastern Maori, the seat which the great Ngata had held for thirty-eight years, in 1943. Since then the Ratana hold on the four seats has been broken only once, when a Maori Mormon briefly held a seat. Ratana’s political success was due largely to two factors: first, the thorough identification of his movement with the expanding Maori proletariat; second, his political alliance with the political representatives of the Pakeha

proletariat, the Labour party, effected by Ratana and the Labour leader, M. J. Savage, on the morrow of Labour’s victory in 1935. The alliance has remained unbroken.

The War and Postwar Developments

The Second World War did not produce the strains in race relations that had been evident during and immediately after the first war. Once more a volunteer Maori battalion was created, and the veteran Ngata, now joined by the Ratana M.P.s, played an active role in recruiting it and in organizing the Maori war effort. This time volunteers came forward freely from all tribal areas. Though the first commander of the battalion was a Pakeha, he was soon replaced by a Maori and thereafter the battalion had Maori officers. The battalion fought with some distinction in Crete, North Africa, and Italy; one of its number, Te Moana Nui a Kiwa Ngarimu, was posthumously awarded the Victoria Cross. At home the Maori communities gave generously to the war effort, and Maori labor was used extensively for producing and packing food, mainly for American troops in the Pacific, or for urban industries hastily devised to meet wartime shortages.

The opening of the war had not prevented New Zealand from celebrating its centenary in 1940. The centennial exhibition in Wellington, the numerous publications that marked the event, including The Maori People Today, edited by I. L. G. Sutherland, and the hui for the opening of the great carved meetinghouse at Waitangi were used by Maori and Pakeha leaders alike to applaud the New Zealand achievement in race relations. So too was the large hui of 1943, at which the V.C. was ceremoniously presented to Ngarimu’s parents. Prime Minister Fraser was as eager as Ngata to make the most of these opportunities.

When the war ended there was no question of the Maori exservicemen’s not receiving the same treatment as their fellow Pakeha veterans. Some got financial aid to start them off on farms or businesses; others were given trade training or educational assistance. In recognition of problems arising from increased Maori urbanization, some of the trade-training schemes started for exservicemen were continued for young Maori civilians, and the government appointed Maori welfare officers to the staff of the Maori Affairs Department.

24 In 1945 the Maori Social and Economic Advancement Act was passed. It formally recognized and provided subsidies for a network of tribal committees charged with promoting

Maori welfare and the preservation of Maori culture. Significantly, Labour was moving away from the age-old policy of assimilation. Fraser, who became minister for Maori affairs in 1947, had a deep sympathy for the Maoris’ attempt to preserve their cultural identity and frequently compared Maori tribalism to the Scottish clan system. In his final report as minister of Maori affairs in 1949, he proclaimed: “An independent, self-reliant, and satisfied Maori race working side by side with the Pakeha and with equal incentives, advantages, and rewards for the effort in all walks of life is the goal of the Government.”

25 It is not surprising that Labour was able to retain its Maori mandate since Fraser’s goal was very like that which Maoris had sought for years; Labour’s only trouble was that it lost the Pakeha mandate in the 1949 election.

To some extent, however, Labour had merely been tampering with problems that were inherent in a situation caused by rapid increases in Maori population and an equally rapid Maori urbanization.

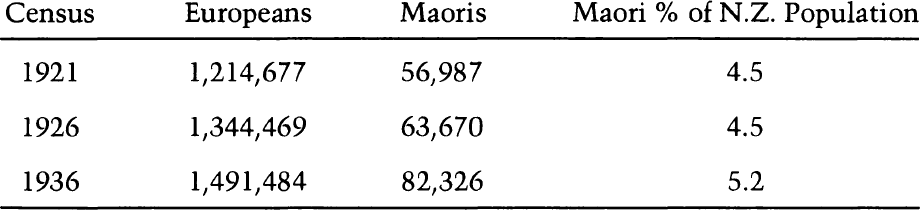

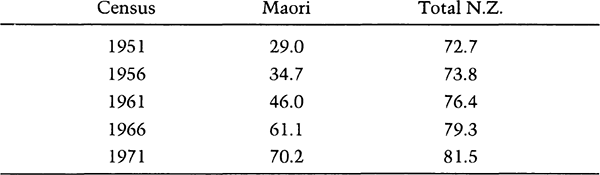

26 These demographic developments are reflected in

tables 4 and

5. Since the Maori population is not spread evenly over the whole country but is concentrated largely in the northern half of the North Island, its density in some northern areas is in fact much higher than the national average.

As the pace of Maori urban migration

27 increased, overcrowding became common in the poorer tenement areas of the cities; there was a danger that these would become racial ghettos. Since the war there had been an acute housing shortage. Maoris found great difficulty in obtaining better housing since most of them had unskilled, low-paid jobs, large families, and little capital or access to credit; and sometimes they were discriminated against by landlords or land agents. There was also some discrimination against them in pubs, schools, and cinemas. By the mid-1950s there was acute tension in some inner-city districts and in one or two rural towns like Pukekohe, a market gardening area where Maoris provided most of the labor force. The exclusion of Dr. Henry Bennett, a well-known Maori psychiatrist and a son of the first bishop of Aotearoa, from a small-town pub provoked a storm of criticism which reached the overseas press. There was a danger that New Zealand’s cherished reputation for amicable race relations would be tarnished.

To its credit, the National government acted speedily to avert a crisis. Acts of discrimination were publicly disavowed. The welfare and land-development policies of the Labour government were carried on. More important now there was a crash program in

providing trade training and urban housing. The Maori Affairs Department took the lead in building houses for rent or sale to Maori families. The housing program had a dual objective: first, to clear congested inner districts; second, by scattering (“pepper-potting”) Maori families throughout new working-class suburbs, to hasten the process of assimilation.

28 It was hoped that Maori families, surrounded by Europeans, would soon adopt the mores of suburbia. In some respects they did so only too well. Anxious to fill their new homes with all the modern conveniences that were thought to be essential, Maori householders often became overencumbered with hire-purchase debts. The new suburbs lacked essential community facilities, and the Maori families, torn away from their rural lives and often without the steadying influence of tribal elders, were in a rootless situation. The young often became involved in petty crime and disturbances; some formed themselves into gangs. A situation all too familiar in societies undergoing rapid urbanization overseas was appearing for the first time in New Zealand.

TABLE 4. MAORI PERCENTAGES OF NEW ZEALAND POPULATION

SOURCE: New Zealand census returns.

The National government was content to press ahead with a program of assimilation, trying anxiously to eliminate remaining vestiges of legal inequality. In 1960 the Maori Affairs Department published a major statement of policy, known as the Hunn Report. It listed the remaining inequalities (most of these in fact discriminated in favor of Maoris) and recommended their gradual elimination. The report contained an important discussion and definition of policy. It rejected any form of segregation of the races. It also rejected assimilation, at least as an immediate objective of government policy, while admitting that “signs are not wanting that that may be the destiny of the two races in New Zealand.”

29 Finally, the report came down in favor of a middle policy called “integration,” defined as an attempt “to combine (not fuse) the Maori and Pakeha elements to form one nation wherein Maori culture remains distinct.”

30 The report was greeted with much Maori criticism. Even those who were prepared to accept integration as a goal were disturbed by the government’s implementation of it, which they saw as nothing but the old policy of assimilation.

31 “Pepper-potting” of Maori housing was but one instance. There was also the bitterly resented attempt by the government to halt uneconomic fragmentation of Maori land by the compulsory purchase of interests of value less than $NZ 50, the abolition of the so-called Maori schools,

32 the streamlining of the judicial system, and the failure positively to promote Maori culture. There is little doubt that National governments were responding to majority European opinion, which assumed that it was sufficient to provide Maoris with equal opportunities (but no favors) in the law courts, education, housing, and employment. It was widely assumed that the government intended to abolish the four Maori parliamentary seats and include Maori voters on the ordinary rolls, but no National government proved willing to grasp this nettle. Though the National party has held office for all but six years of the period since 1949, it did not once capture a Maori seat. This was sure evidence of the electoral unpopularity of the National government’s administration of Maori affairs.

TABLE 5. P

ERCENTAGE OF N.Z. P

OPULATION L

IVING IN U

RBAN A

REAS

SOURCE: New Zealand Official Year Book, 1972, p. 63.

Yet it was also a consequence of the continuing low socioeconomic status of the Maori people within the New Zealand community. Despite undoubted improvements in Maori health and housing and despite their fuller integration into the national economy, Maoris remained dangerously overrepresented in lower paid, unskilled forms of employment and badly underrepresented in

highly skilled, professional, commercial, managerial, and administrative positions.

33 They have failed to reach the higher rungs of the establishment because not enough of them have passed a series of competitive examinations at secondary and tertiary levels of education. Dropouts from the educational system have helped populate the prisons; Maoris, according to the official statistics, have a higher rate of crime than Pakehas. But in education, as in crime, it is not so much that Maoris are failing as it is that they are being failed by an alien system ill adapted to their needs and aspirations. With its education, as with its judicial system, New Zealand is forcing a monocultural system onto a multicultural society. In consequence race relations have again come under strain.

This failure to accommodate an ethnic minority, to recognize and preserve its identity, is not unique to New Zealand. Indeed, New Zealanders have still to learn the lesson that their race relations are neither very different nor necessarily better than race relations in other countries with a similar ethnic composition. Moreover, New Zealand’s race relations are being complicated by the influx of Polynesians, most of them from the former New Zealand territories in the South Pacific—Western Samoa, the Cook Islands, Niue, and the Tokelaus. The 1971 census recorded 45,413 Polynesians other than Maoris living in New Zealand, 1.6 percent of the total population. Since the islanders compete with local New Zealanders and especially with Maoris for employment, housing, and social services, there are and will continue to be stresses in race relations. But there are also advantages, so far only barely appreciated, of this recent Polynesian migration to New Zealand. The islanders bring further cultural diversity to a country that has long been characterized by a dull conformity to Anglo-Saxon cultural norms. It is from the diverse Polynesian cultures—and from indigenous developments in Pakeha society—that New Zealand will find its national identity. The real significance of race relations over the last fifty years is that Maoris, and lately other Polynesians, have begun to recover the place in New Zealand that was very nearly obliterated by a century of European colonization and all that that meant. But there is a very long way to go, for Maoris have little more than their turangawaewae (a standing place for the feet) and some of them not even this, in a land that was once theirs.

It was Frank Corner, later to become secretary for foreign affairs, who said in 1962 that “the renaissance of the Maori people is

making New Zealand the chief country of Polynesia and restoring our moral right to take a leading part in its affairs.”

34 Here was a new version of an old myth: New Zealand, by virtue of its treatment of Polynesians at home, had the right to handle them abroad. Certainly there has been an improvement in relations with island Polynesians since the hysterical imperialism of the nineteenth century with “Vogel and Seddon howling empire from an empty coast”; or even at the outbreak of the First World War when “in an atavistic flurry of imperialism, New Zealand had acquired Western Samoa”;

35 or, yet again, in the later 1920s when New Zealand’s heavy-handed paternalism provoked the Mau resistance in Samoa. But it was only in the latter stages of New Zealand’s rule in Samoa and elsewhere that the paternal civilizing mission—so characteristic of nineteenth-century treatment of the Maoris—gave way to an enlightened appreciation of Polynesian values and aspirations, including their desire for a full or qualified form of independence. The change came in the late 1930s. It was reinforced by the high ideals of the Atlantic Charter and given direction by the Trusteeship Committee of the San Francisco Conference, which was chaired by Peter Fraser. In the islands New Zealand was well served by administrators like Guy (later Sir Guy) Powles and J. M. McEwen and by constitutional advisers like J. W. Davidson and Colin Aickman. In the two decades after the Second World War, New Zealand was to guide its main island territories to independence in a manner which won it international acclaim. But whether it will retain a moral right to exercise a leading part in Polynesian affairs will depend on its treatment of Polynesians at home and abroad. That right is by no means assured.

Notes

I have not attempted to take the discussion past 1976, the date of the last census. Maori words not in common usage are italicized with translations in parentheses. Currency figures are in New Zealand, not United States, dollars.

| 1 |

Keith Sinclair, “Why Are Race Relations in New Zealand Better Than in South Africa, South Australia or South Dakota,” New Zealand Journal of History, V, 2 (October 1971), 121–127. |

| 2 |

J. Forster, “The Social Position of the Maori,” in Erik Schwimmer (ed.), The Maori People in the Nineteen-Sixties (London: C. Hurst, 1968), 104. |

| 3 |

Robin W. Winks, These New Zealanders (Christchurch: Whitcombe and Tombs, 1954); David P. Ausebel, The Fern and the Tiki (Sydney: Angus and Robertson, 1960). |

| 4 |

P. S. O’Connor, “Keeping New Zealand White, 1908–1921,” New Zealand Journal of History, II, 1 (April 1968), 41–65. |

| 5 |

Unless otherwise indicated, all figures are taken from New Zealand census returns. |

| 6 |

The best of numerous discussions of early colonization and racial conflicts are Keith Sinclair, The Origins of the Maori Wars (Wellington: New Zealand University Press, 1957), and Alan D. Ward, A Show of Justice (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1973). |

| 7 |

M. P. K. Sorrenson, “The Purchase of Maori Lands, 1865–1892” (M.A. thesis, University of Auckland, 1955). |

| 8 |

John Adrian Williams, Politics of the New Zealand Maori (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1969); R. T. Lange, “The Revival of a Dying Race: A Study of Maori Health Reform, 1900–1918” (M.A. thesis, University of Auckland, 1972). |

| 9 |

G. V. Butterworth, “A Rural Maori Renaissance? Maori Society and Politics, 1920–1951,” Journal of the Polynesian Society, 81, 2 (June 1972), 160. |

| 10 |

J. M. Henderson, Ratana: The Man, the Church, the Political Movement (2d ed., Wellington: Polynesian Society, 1972), 17. |

| 11 |

Butterworth, op. cit., 165. |

| 12 |

Ibid., 168. |

| 13 |

Appendices to the Journal of the House of Representatives (A.J.H.R.) 1928, G-8. |

| 14 |

M. P. K. Sorrenson, “Maori Land Development,” New Zealand’s Heritage, 6, pt. 83 (1973), 2309–2315; Butterworth, op. cit., 174–178; J. B. Condliffe, New Zealand in the Making (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1930), chap. 2; F. M. Keesing, “Maori Progress on the East Coast,” Te Wananga, I (1929), 10–55, 92–93. |

| 15 |

Butterworth, op. cit., 176. |

| 16 |

A.J.H.R. 1934, G-11. |

| 17 |

Butterworth, op. cit., 180–181. |

| 18 |

Ibid., 181. |

| 19 |

Ibid., 457. |

| 20 |

Iwi is usually translated as “tribe” but Buck and Ngata often equated it with “the people” or “the race.” Buck-Ngata correspondence, 1927–1937, passim, Ramsden Papers, Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington. |

| 21 |

Alice Joan Metge, The Maoris of New Zealand (London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1967), 59. |

| 22 |

The main study is Henderson’s Ratana. |

| 23 |

Ibid., 121. |

| 24 |

Butterworth, op. cit., 187–190. |

| 25 |

Ibid., 188. |

| 26 |

New Zealand Official Year Book, 1972, p. 63. Here “urban” is described as a concentration of 1,000 people. |

| 27 |

The main source is Alice Joan Metge, A New Maori Migration: Rural and Urban Relations in Northern New Zealand (London: University of London, Athlone Press, 1964). |

| 28 |

Metge, Maoris of New Zealand, 80. |

| 29 |

J. K. Hunn, Report on Department of Maori Affairs (Wellington: Government Printer, 1960), 15. |

| 30 |

Loc. cit. |

| 31 |

Metge, Maoris of New Zealand, 216. |

| 32 |

These were primary schools established by the Labour government in the late 1930s in districts where there was a preponderance of Maoris. They had a special curriculum with some emphasis on Maori culture. Pakeha children could and sometimes did attend them, but there was a danger that they would become a vehicle for educational segregation—hence their abolition by the National government despite Maori opposition. |

| 33 |

Department of Industries and Commerce, The Maori in the New Zealand Economy (1967). The report was compiled mainly by G. V. Butterworth. |

| 34 |

“New Zealand and the South Pacific,” in T. C. Larkin (ed.), New Zealand’s External Relations (Wellington: New Zealand Institute of Public Administration, 1962), 150. |

| 35 |

Ibid., 137. |