The Marine Luchtvaart Dienst (MLD), or Naval Air Service, is the Dutch Naval Air Service. Initially formed in 1916 using interned German aircraft that had crossed the Dutch border in World War One, and volunteer officer crews from the surface fleet, the MLD was officially signed into existence by the Dutch Government on August 18, 1917. Since then, it has functioned as a separate force within the Royal Netherlands Navy (Koninklijke Marine or KM) throughout its long history. Although the MLD’s origins were primitive, like all contemporary air arms, it quickly evolved into an advanced, highly trained force during the inter-war years.

Between the First and Second World Wars, its duties were rather mundane, although they gradually intensified throughout the 1930s as the threat of war with Japan in the Pacific loomed. Extensive day and night patrols were carried out across Dutch colonial territory in the Netherlands East Indies, mostly to investigate Japanese fishing vessels and foreign merchant ships. By the start of the Pacific War, no ship could enter the archipelago without being quickly sighted by an MLD plane. Once sighted, a nearby naval, or Gouvernementsmarine,1 vessel would be directed to the scene so that the ship could be boarded and searched.

By the start of the Second World War, the MLD’s primary duties included anti-submarine (A/S) patrols, convoy and fleet escort, air reconnaissance and minelaying. In the Far East, these were expanded to include helping the Hydrographic Service chart harbors and waterways, delivery of supplies to isolated outposts and the support of civilian police forces.2 Operational doctrine called for the MLD to work closely with the fleet by relaying the position, course and speed of enemy ships. However, after the fall of Holland and the East Indies, there were few Dutch ships to support, so its role evolved into pure reconnaissance and A/S duties.

The MLD was a relatively small force within the KM when Germany invaded Holland in May 1940. Although funds had been authorized for increased personnel and new planes, the German invasion completely demolished a build-up of the naval air squadron in the Netherlands East Indies, where the bulk of the KM and MLD had traditionally been based. As a result, newly revived Dutch efforts to reinforce their military strength in the NEI and guard against a feared Japanese attack3 were completely disrupted.

As a result, the East Indies Naval Squadron had to turn to other countries for assistance in order to continue the build-up. However, all branches of the East Indies military experienced continuing problems in these efforts. Germany had occupied most of Europe while Britain was fighting for its very survival and had no manufacturing capacity to spare for the Dutch. This left only the United States as a reliable source for heavy weapons, ammunition, large ships, aircraft and other military supplies, such as radio equipment, sights and related specialized equipment.

The Netherlands East Indies, December 1941

Unfortunately, the government initially proved hesitant to provide the Dutch with any kind of military support, modern weapons in particular. It feared the Dutch would follow the “French Model” in Indochina. Following the fall of France in June 1940, the Japanese placed intense pressure on the colony’s government, which eventually allowed Japan’s military to take de facto control of the territory. With Japan putting similar pressure on the colonial government of Governor-General Tjarda van Starkenborgh Stachouwer, the United States feared the Dutch would also bow to the pressure, wasting valuable resources that were needed for its own military build-up.

But while the Vichy French government actively collaborated with Nazi Germany, the Netherlands’ Queen Wilhelmina escaped to London and formed a government-in-exile that would oversee Dutch efforts to continue fighting. With final say over all colonial decisions, this body played a key role in thwarting Japanese demands for greater economic and political control in the East Indies.4 And as Governor-General Starkenborgh’s government demonstrated its resolve to remain independent of Japanese control, the United States Government proved more willing to support the Dutch East Indies militarily.

As these restrictions loosened, the MLD proved particularly successful in obtaining aircraft and equipment from the United States. Although its own military was in the midst of a major build-up prior to the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, the United States Navy did not consider reconnaissance aircraft to be a top priority. This left the Consolidated and Sikorski plants free to fill Dutch orders without reducing American military demands. However, many of the aircraft the Dutch purchased still failed to arrive before the fall of the East Indies.

Before the new equipment arrived, the MLD operated an obsolescent fleet of indigenous Fokker seaplanes and German Dornier flying boats.5 In addition, there were a small number of modern German and Dutch flying boats sprinkled throughout. After the German invasion of Holland, acquisition of spare parts and replacement engines for the older aircraft was impossible. As a result, it became extremely difficult for the MLD to maintain its fleet of aging seaplanes.

To strengthen and modernize the MLD, the Dutch government between 1937 and 1940 authorized funding for 78 large seaplanes and 22 torpedo-carrying seaplanes. At the core of this appropriation were additional Do. 24Ks and the new Fokker T.VIII torpedo bomber, which was still under development. After May 1940, the Dutch were forced to turn to the United States for aircraft and equipment, which yielded fairly positive results for the MLD by the start of the Pacific War. All transactions in the United States were conducted by the Netherlands Purchasing Commission (NPC), which was formed by the Netherlands government-in-exile in June 1940 to continue the build-up of Dutch forces in the Far East.

The most numerous among the large MLD seaplanes were 10 twin-engine T.IVa floatplanes. Featuring all-metal construction and two large floats under the fuselage, the T.IV had been designed as a torpedo/horizontal bomber and reconnaissance plane in the mid-1920s. The T.IV was also the first long-range seaplane acquired by the MLD, allowing it to effectively patrol the broad expanses of the East Indies archipelago on a regular basis for the first time.

Ten Fokker T.IVa seaplanes were still in service with the MLD in December 1941 (photograph courtesy of San Diego Aerospace Museum).

Twelve Fokkers originally reached Morokrembangan in 1927, where they were designated as “T” class flying boats to distinguish them from other MLD seaplanes. The original aircraft were the T.IV version, featuring open cockpits and exposed gun positions. Numbered T-1 through T-12, all of these aircraft were written off and taken out of service in 1939 and 1940. The only exception was T-1, which was lost in an accident on October 16, 1937.

Based on the success of these first 12 aircraft, the MLD ordered a second batch of improved T.IVa models, which featured enclosed cockpits, gun positions and more powerful engines. Six (T-13 through T-18) were ordered in January 1935; these were followed by another half dozen aircraft (T-19 through T-24) beginning in January 1937. Of this group, T-13 was lost in a landing accident on October 12, 1937, while T-14 was lost on May 26, 1941. Shortly after the arrival of this group, the remaining T.IVs were upgraded to T.IVa status by MLD workshops on Java.

In December 1941, the remaining T.IVs were operating with GVT.11 and GVT.12 under the command of 1st Lieutenant J. Craamer and 1st Lieutenant B.J.W.M. van Voorthuijsen6 of the Royal Netherlands Naval Reserve. Throughout the East Indies campaign, several of these planes were used for bombardier training; most were modified shortly after the outbreak of war to carry three depth charges and assigned to fly A/S and reconnaissance patrols along the north coast of Java and over the Java Sea. The surviving planes were destroyed on Java on March 2, 1942, to prevent their capture.7

This was a highly successful twin-engine, twin-float design that was intended to replace the T.IV. First ordered by the MLD in 1938, the first T.VIII was built to a Dutch government requirement that called for a long-range, high-speed seaplane that could function in both the horizontal and torpedo bomber role. It featured mixed wood and fabric construction, although later all-metal models were specifically built for service in the Far East. However, it was the aircraft’s long-range, heavy payload and superior handling characteristics in the torpedo-bomber role that made it attractive to MLD forces in the East Indies.

Despite teething problems through the seaplane’s test period, the MLD placed an order for 36 Fokker T.VIIIs. The first five aircraft were of the early mixed construction model; assigned the serial numbers R-1 through R-5, they were ordered in September 1938. A second batch, given the serial numbers R-6 through R-24, was ordered in January 1939. R-25 through R-36 were ordered in February 1940. Although most were intended for units in the East Indies, the outbreak of war in Europe in September 1939 delayed their delivery, and none was delivered as the Dutch government acted to build up its military forces in Europe.

Only the first 11 aircraft were delivered prior to the German invasion of Holland. Eight of these aircraft escaped to England in May 1940, where they operated with the RAF as 320 Squadron (Dutch) until replaced by newer aircraft. R-12 through R-36 were captured by the Germans while still under construction and flown by Kreigsmarine units in the Mediterranean. One of these aircraft was later stolen and flown to England by a Dutch pilot on May 6, 1941.

There were a limited number of Fokker C.VII-W reconnaissance and training aircraft (“V” planes). Twelve of these seaplanes were originally shipped to the Netherlands East Indies in 1928 and 1929. Although their numbers were depleted by age and attrition, those few that remained were primarily used for torpedo launch and bad-weather flight training. Although it appears that most or all of the remaining aircraft were retired from service by 1941, it is possible that some still flew in ancillary or training roles during the Japanese invasion. They would have been destroyed in the fighting or just prior to Java’s surrender in March 1942.

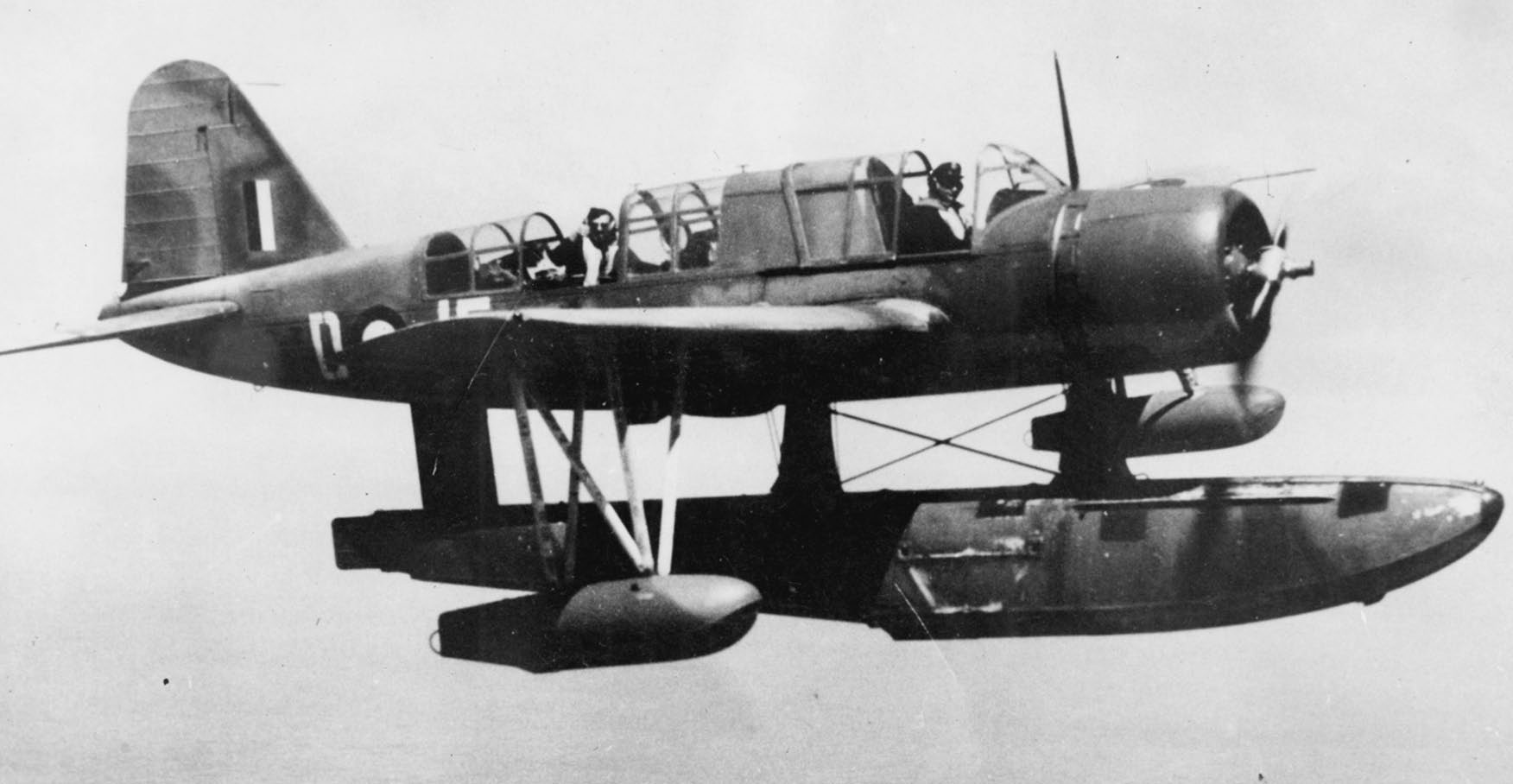

The remaining Fokkers in the NEI were eight two-man C.XI-W floatplanes (“W” planes), of which 15 had originally been acquired in the mid-1930s. By December 1941 their numbers had been reduced to the aircraft W-1, W-4, W-8, W-10, W-11, W-12, W-14 and W-15 through a series of landing accidents and combat losses inflicted by the Germans during their invasion of Holland.

Designed for shipboard service, the C.XI-W entered service in 1938 in the reconnaissance role. It had stressed wings for catapult launches and a range of 453 miles. Although primarily designed as a cruiser plane, the KM carried out a series of tests in the late 1930s to evaluate the ability of the C.XI-W and other single-engine seaplanes to operate aboard Dutch destroyers and Flores-class gunboats based in the NEI. However, these tests were not particularly successful, as the destroyers were unable to use their “X” mounts while carrying the aircraft.

Operationally, they flew only off the Dutch light cruisers De Ruyter and Java8 throughout the East Indies campaign, except during the battle of the Java Sea, when all were put ashore. The light cruiser Sumatra carried two aircraft when she reached Java in late 1941, but they were transferred ashore when that ship entered extended overhaul. A fourth light cruiser, the Tromp, was also equipped to carry two C.XI-Ws, although she apparently shipped only a single floatplane prior to the war. This plane was badly damaged in November 1941, and it is unknown if it was ever replaced. Many of these aircraft were lost during Japanese air raids on Java; MLD ground crews destroyed the remainder when Java fell in March 1942, as they did not have the necessary range to reach Australia or Ceylon.

There were also 10 Fokker C.XIV-W floatplanes (“F” planes) on Java that had been developed as advanced training and light reconnaissance planes to replace the Dutch military’s aging Fokker C.VII-W seaplanes. At the time of Pearl Harbor, the remaining Fokkers were the remnants of 24 aircraft (F-1 through F-24) delivered to the KM in Holland and the East Indies between May and December 1939.

Eleven aircraft survived the German invasion of the Netherlands and eventually reached England. The MLD shipped 10 of these aircraft (see Appendix 4) to the Netherlands East Indies later that year for operations with its flight training school. Aircraft F-3 remained in England for operations with 320 Squadron (Dutch). It is unclear how many of those sent to the East Indies were lost during Japanese air strikes on Java, but all surviving machines were destroyed on Java to prevent their capture when the island fell to the Japanese in March 1942.

The MLD and Germany’s Dornier aircraft factory had a long history. Their relationship started in the 1920s when the Dutch placed orders for 41 Dornier Do. 15 “Whales” for use in the East Indies in a long-range reconnaissance role. They were intended to supplement and eventually replace the T.IVs. The first five arrived on Java in 1926 and operated as “D” class seaplanes. The arrival of the Do. 15s in the Far East was significant, as their endurance and sturdy construction allowed the MLD to effectively patrol the broad expanses of the NEI by air for the first time.

Only six of the ten Do. 15 “Whales” remained operational with the MLD flight training school in December 1941 (photograph courtesy of San Diego Aerospace Museum).

Although highly valued by the MLD for their long range and ability to land on and take off from short waterways, production of the Do. 15 ceased in 1931 due to the worldwide depression. With Germany’s occupation of Holland, the MLD found it extremely difficult to maintain the aging seaplanes due to a lack of spares. It appears that at least one (D-42) was cannibalized for spare parts in 1940 to keep the others flying. Most of the remainder were retired from service in the late 1930s with their engines being used in the construction of motor torpedo boats for the KM’s East Indies Naval Squadron.

Six of the last ten remaining “Whales” were still operational in December 1941, although newer Dornier Do. 24K-1s had long since phased them out of front-line service. They were used primarily as advanced trainers by the MLD flight training school. Numbered D-41 through D-46, these were the newer Do. 15F model. It featured more powerful engines, a longer wingspan, more streamlined fuselage and keeled hull (as opposed to flat), which provided for enhanced flight characteristics, stability and sea-handling qualities.

Commonly referred to as “X-boats” (because of their serial numbers, which were numbered X-1 through X-36), the Do. 24K-1 was a large, rugged seaplane specifically designed for long-range reconnaissance and air-sea rescue in the broad expanses of the East Indies. The Dutch initially approached Dornier with the request for a new flying boat to replace their aging Do. 15 “Whales,” from which the Do. 24 grew. It was a tri-motor flying boat with a heavy hull, good defensive armament (in later models) and a maximum range just under 3,000 miles. The prototype was delivered in 1937, followed by 11 German-built production models in 1937 and 38.

A prewar photograph of the Do. 24K-1 flying boat X-15; note the absence of a dorsal turret and armament (photograph courtesy of Nol Baarschers).

After delivery of the first six aircraft, the Netherlands Ministry of Defense placed orders totaling 72 flying boats to help offset the increased Japanese threat to the NEI. The first 36 would be the Do. 24K-1 with the 875 horsepower Wright-Cyclone engine. Although 15 percent lighter than the Jumo Junkers 600 horsepower 205C diesel engine, which would later equip Luftwaffe Dorniers, the Wright-Cyclone provided 50 percent more power. It was also in widespread service on the KM’s Fokker T.IV seaplane and the twin-engine Martin 166, an export version of the USAAF Martin B-10 medium bomber then in service with the ML, or Militaire Luchtvaart (Royal Netherlands Army Air Force).

Beginning with the 37th Dornier, production shifted to the Do. 24K-2. The main improvements on these planes included the addition of the Wright-Cyclone 1,100 horsepower engine and larger fuel tanks for increased endurance. With the added power, the K-2 was extremely maneuverable and could effectively operate from the short waterways that the MLD often encountered around its undeveloped secondary bases.

Although all the flying boats of both versions featured armament in three Alkan dorsal turrets, the first 12 Do. 24K-1s were armed entirely with Colt-Browning 7.7mm machine guns license-built by FN-Browning in Belgium. Beginning with X-13, a rapid-fire Hispano-Suiza Model 404 20mm cannon replaced the machine gun in the dorsal turret. It is unknown whether the first 12 planes were ever retrofitted with the heavier armament after their arrival in the Far East.

In 1939 the number of KM seaplanes on order was reduced to 48 in order to free up funding for the ML, which at the time was acquiring the first of its Martin bombers. However, on June 16, 1939, the MLD placed orders for another 13 flying boats. Nine months later it followed up with an order for 12 additional seaplanes on March 12, 1940.

On the step! At full power, time to liftoff for the Do. 24K-1 was only 17 seconds, although it took 27∂ minutes to reach 16,500 feet (photograph courtesy of André de Zwart).

Beginning with X-13, a Hispano-Suiza 20mm cannon replaced the 7.7mm Colt-Browning machine gun in the Do. 24K’s dorsal turret (photograph courtesy of André de Zwart).

Only 36 Do. 24K-1s reached the East Indies before the German occupation of Holland. Two years after her arrival on Java, X-4 was lost in a night landing accident with her entire crew on April 13, 1940. The loss of X-2 followed on November 13, 1941, while taking off at Morokrembangan, further reducing the number of operational planes to 34 by December 1941. Both were operating as training aircraft with the MLD’s flight training school at the time of their loss.

A 37th flying boat, the X-37, arrived on Java in 1940, but its engines proved defective. The first of the new K-2 series, X-37 had completely different engines than the Do. 24K-1s already in service. And because the MLD in the East Indies had yet to receive any spare engines for this model, it remained inactive throughout the Japanese invasion as replacements could not be obtained from Germany or occupied Holland. In the meantime, ground crews rebuilt the Dornier into a command plane for the commander of the MLD.

When German forces overran Holland, they seized 13 Do. 24K-2s in various stages of construction at the Aviolanda Factory. They also captured enough materials to complete 16 more. At the same time, they seized a number of Wright-Cyclone engines and spares that were destined for use in the East Indies. The plant’s production line quickly reopened under German control, allowing them to complete X-38 and X-39 almost immediately, which the Kriegsmarine subsequently put into service along with the others as they rolled off the line.9

These losses aside, all front-line MLD squadrons in the NEI were able to convert to the Do. 24K-1 between the outbreak of war in September 1939 and the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor in December 1941. In turn, the older Do. 24K-1s (those with the lowest numbers) were replaced with newer aircraft (those with higher numbers) as the outbreak of war drew nearer.

By December 1941, the operational front-line planes were spread throughout the East Indies to cover strategic ports and waterways leading into and out of the Netherlands East Indies. The basic MLD formation was the three-plane GVT (Groep Vliegtuig or Aircraft Group). Eight groups totaling 24 planes, with a small number of newly arrived PBY-5 Catalinas, formed the backbone of the MLD’s first-line reconnaissance strength. The remaining 11 Dorniers formed a small reserve pool at Morokrembangan, the MLD seaplane base at Soerabaja.10

Dornier losses were heavy, with no fewer than 28 of the original 34 lost in action or through accidents (two of the X-boats, X-2 and X-4, are not considered war losses, as both were lost in training accidents before the outbreak of war). Only six survived the East Indies campaign and subsequent evacuation of Java in March 1942 to fight another day. As their losses mounted and new American-made PBY Catalinas became available, the Do. 24K was gradually phased out.

American-built planes eventually made up a substantial portion of the MLD. As part of an emergency plan to build up the MLD, 48 Consolidated Model 28–5MNE Catalinas (“Y” boats) were ordered by the Dutch in 1940 to replace their Do. 24Ks. With a fuel capacity exceeding 14,000 gallons, the Model 28–5 could stay in the air for up to 22 hours. So in addition to easing maintenance issues, it was an ideal patrol aircraft to survey the vast expanses of the Netherlands East Indies.

Essentially the export version of the USN’s PBY Catalina patrol bomber,11 this order consisted of 36 PBY-5 seaplane variants, which were to be followed by 12 more aircraft. The German seaplanes, although tough and reliable, were becoming extremely difficult to maintain in the absence of spare parts following the occupation of Holland. The first two aircraft were scheduled to reach Java in August 1941, with the remainder of the order following in lots of four, four, six, six, six and six respectively, with the final two PBYs arriving in March 1942.12

Y-87 failed to reach Java before the Dutch surrender in March 1942 (photograph courtesy of San Diego Aerospace Museum).

Although the first two PBYs arrived at Morokrembangan on September 5,13 and a total of 36 arrived before the fall of Java, they did not replace the Dorniers on a large scale until war losses mounted. This was mostly due to the severe shortage of trained aircrews. The remaining 12 PBY-5A Catalinas still on order failed to arrive before the Japanese landed on Java.14 They were later delivered to the MLD forces operating from the Indian Ocean island of Ceylon. From here, they flew search-and-rescue missions for the remainder of the Pacific War as 321 Squadron (Dutch), attached to the Royal Air Force at China Bay (near Trincomalee) on the Indian Ocean island of Ceylon.

The first 15 aircraft reached Morokrembangan by mid-October 1941 and were being readied to phase out the older Dorniers. But although the MLD still faced a critical shortage of aircraft, it very nearly lost a substantial portion of the remaining PBYs before they ever arrived in the East Indies.

Due to a dramatic miscalculation in American production priorities, the British were under the impression that they would receive at least 155 PBYs between July 1941 and April 1942.15 However, in early July they learned that no Catalinas were allocated for British delivery until May 1942, putting Britain in a severe bind. This was because by late 1941 the Battle of the Atlantic had reached a fever pitch as German submarines routinely mauled British supply convoys sailing to and from North America. As a result of these growing losses, the RAF and Coastal Command squadrons desperately needed long-range aircraft to help stem the losses.

Locked out of the existing production timetables, the British attempted to obtain the MLD PBYs that were in the process of being delivered to the NEI. They first raised the issue in September 1941 with the Dutch government-in-exile. The British need was so great that they initially considered offering the Dutch 100 P-40E Kittyhawk fighters—which the Dutch had unsuccessfully tried to obtain from the British earlier—in exchange for 18 of the 36 Catalinas that the Dutch had on order. However, it appears that the fighters were either not available, or the RAF would not agree to the transfer, as the offer was apparently never presented to the Dutch.

Y-38 or Y-39 being prepared for duty shortly after their arrival at Morokrembangan on September 3, 1941. In the background is a Do. 24 (photograph courtesy of Institute for Maritime History).

On September 24 a delegation from the British Air Ministry met with Vice Admiral J.T. Furstner, the Dutch Minister for Naval Affairs in London, to officially raise the issue of obtaining 18 of the 21 MLD PBYs that had not yet reached Morokrembangan. Although the British sought to convince him that their presence in the Atlantic desperately outweighed Dutch needs in the NEI, Furstner refused their request due to the limited number of front-line flying boats then operating in the East Indies. As detailed earlier, the PBYs were needed to replace the MLD’s aging Dorniers, which were becoming difficult to maintain.

In response, the British tried an end run by appealing directly to Admiral Helfrich in a face-to-face meeting at Batavia on October 10. If they could change his mind, they clearly hoped to influence Admiral Furstner’s stance. This time, it appears that Helfrich raised the issue of trading the PBYs for a number of Bristol Beaufort torpedo bombers in return. These would come from Australian-produced stocks, of which some 270 aircraft would be available sometime between June and August 1942. After a series of internal exchanges, this proposal was rejected when the British deemed that none of the Beauforts could be spared.16

Thus arriving in Batavia empty handed, the British argument once again hinged on convincing the Dutch of the critical nature of the Atlantic Theater. They also voiced their belief that the MLD did not have enough pilots and flight crews in the East Indies to man the aircraft. Helfrich replied that the MLD did have ample manpower and that he would need all of the aircraft in the event of war with Japan. Nonetheless, he agreed to the transfer if the London government concurred that the Atlantic Theater had higher priority than the build-up of his forces in the NEI.

Throughout the process, the British Air Ministry sought to obtain a quick transfer of the MLD aircraft, which were scheduled for delivery to Java at a rate of 10 per month. As 15 PBYs had already reached Morokrembangan, it was deemed imperative that their request be approved before any of the remaining 21 aircraft departed. The Air Ministry correctly foresaw that it would be all but impossible to secure Dutch agreement for their request once the Catalinas had departed the Consolidated Aircraft factory in San Diego, California, for delivery to the Far East.

One major sticking point to the transfer was that both the Australian and Dutch governments believed that approximately 200 PBYs would be delivered to the RAF by mid-1942. As a result, the Dutch felt that the MLD seaplanes were not as critical as implied. The British countered with production figures that showed 282 PBYs were scheduled for delivery between December 1, 1941, and June 30, 1942. With the exception of the 36 Dutch aircraft, and another 50 allocated to Canada (most of which were later obtained by the British Air Ministry as well), all of the remainder were slated for USN and USAF units.

In the meantime, the Dutch government continued to debate the request. Its decision was made easier in mid-October when the Japanese government’s civilian Cabinet resigned, leaving Japan in control of its military, which advocated the removal of western colonies from Asia through military action. As a result of this sudden change in the Far East’s political landscape, the British recognized the sensitivity of the situation and decided to back off their request for a week or so to see how things wrinkled out. For their part, the Dutch promptly delayed any decision on the matter until December 16. In the meantime, deliveries to Java continued, and the attack on Pearl Harbor abruptly ended the discussion.

In the end 35 of the 36 Catalinas eventually reached Java, where no fewer than 27 of the aircraft were lost.17 These losses include a Dutch PBY destroyed in the attack on Pearl Harbor, three Catalinas loaned to the Royal Navy at Singapore shortly after the outbreak of war and five more loaned to the United States Navy in January 1942. Still, because of the Catalina’s lighter armament and twin-engine arrangement, Dutch crews greatly preferred the heavier, albeit older, Dorniers with their 20mm cannon, third engine and eight self-sealing fuel tanks.

During the military build-up in the East Indies between May 1940 and December 1941, the Dutch government purchased a number of training aircraft. Forty-eight Tiger Moth primary trainers were purchased from Australia, including 33 for the ML and 15 for the MLD. Eleven of these planes were allocated to the East Indies Volunteer Flying Club, a group of nine government-subsidized volunteer clubs formed in May 1941 to help train young men aged 17–20 as reserve pilots.

Table 1—East Indies Volunteer Flying Clubs

• NEI Flying Club, Andir (Java)

• Batavia Flying Club, Kemajoran (Java)

• Soerabaja Flying Club, Morokrembangan (Java)

• Semerang Flying Club, Benteng River (Java)

• Djojakarta Flying Club, Djojakarta (Java)

• Malang Flying Club, Singosari (Java)

• Balikpapan Flying Club, Balikpapan (Borneo)

• Medan Flying Club, Medan (Northern Sumatra)

• South Sumatra Flying Club, Palembang (Southern Sumatra)

An MLD Ryan STM-S2 primary trainer over Soerabaja (photograph courtesy of San Diego Aerospace Museum).

In addition to the Tiger Moths, the volunteer flying clubs had five Bückner Jungmann primary trainers that had been acquired from Germany before the war. They were joined by two Piper Cub light aircraft. Many of the reserve pilots called up by the MLD immediately prior to the start of the Pacific War received their primary flight training through these volunteer flying clubs.

Following the occupation of Holland, the MLD also ordered 48 Ryan primary trainers, or “sport aircraft,” for MLD flight training in the East Indies. Assigned serial numbers S-11 to S-58, half of these planes were the STM-2 land configuration model, and the remainder were STM-S2 floatplanes.18 The first three Ryans reached Java in November 1940 and were followed by 12 more in January 1942. A total of 108 aircraft eventually reached ML and MLD forces throughout 1941.

The MLD aircraft were immediately sent to Perak Airfield outside Soerabaja and Morokrembangan, the primary seaplane base on Java. Although considered trainers, a number of Ryan floatplanes were sent to Borneo following the outbreak of war to fly reconnaissance missions and patrol the island’s various harbors. A number of Ryans were lost during the East Indies campaign, but 34 survived to be evacuated to Australia in March 1942, where they were bought by the Australian government and transferred to the RAAF.

The MLD still had a large number of planes on order when the Japanese attacked. They were all American models, most of which never arrived before the fall of the NEI. These were later dispersed among the various US allies. The largest order consisted of 80 Douglas DB-7B and DB-7C light bombers, which the MLD intended to use as torpedo bombers in an anti-shipping role. The KM reserved for them the serial numbers D-47 through D-126. Of these, 48 were eventually bought by the Netherlands Purchasing Commission and constructed by Douglas; however, the MLD received only six planes just a week before the fall of Java.19

Only one DB-7 ever got into the air, with the remainder being destroyed by the Dutch or captured by the Japanese. Japanese photos show that at least one of these planes was captured or assembled from the parts of destroyed planes and taken to Japan for testing. The USAAF took over the remainder of the order and distributed it to the RAAF and Soviet Union under the Lend-Lease Program. The wreck of one Australian bomber was found in the New Guinea jungle in the 1980s, complete with MLD serial number and RAAF insignia painted over Dutch markings and camouflage.

Four KNILM Sikorsky S-43 seaplanes operated under MLD control during the NEI campaign (photograph courtesy of San Diego Aerospace Museum).

The MLD ordered 24 VS.310 Kingfishers, but Java fell before their arrival, and 18 of the planes were instead delivered to the RAAF (photograph courtesy of Craig Busby).

The MLD also placed an order for 48 twin-engine Sikorski S-43 seaplanes,20 a military version of the same type of aircraft then in service with KNILM and numerous other civilian airlines around the world. This aircraft was intended to serve in a transport role, most likely to help maintain its extensive chain of isolated seaplane bases throughout the NEI. It is unclear whether these aircraft were actually ordered by the Netherlands Purchasing Commission or the MLD simply placed an option for them between the fall of Holland and the attack on Pearl Harbor. In any event, none was delivered prior to the fall of Java, and the order lapsed.

Two MLD VS.310s being prepared for transport to the NEI by Dade Brothers shipping company of Long Island (photograph courtesy of Cradle of Aviation Museum).

Also on order were 24 Vought-Sikorsky VS-310 Kingfishers.21 The Kingfisher was a modern, single-engine floatplane designed to operate either from land or as a catapult-launched shipboard aircraft. It first flew in 1938, and the Dutch order followed in 1940. The Kingfishers were intended to replace the KM’s older single-engine Fokker floatplanes, which were also becoming difficult to maintain in the absence of spares. The Kingfishers were to be delivered with six spare engines, six constant-speed propellers and 20 percent spare parts and tool kits. Ordnance equipment, including weapons, would be delivered with the aircraft.

Dutch officials urgently requested these aircraft during a fact-finding mission to Java by several American military officers in early August 1941.22 On August 25, the White House approved the diversion of these aircraft from existing USN orders, although the Dutch government still had to pay for them up front. Dutch purchasing officials accepted the aircraft, numbered V-1 through V-24, on December 31, 1941. They were immediately put aboard three merchant vessels23 at New York and routed to the East Indies.

However, Java fell before they arrived, and all three ships were diverted to Australia, still carrying their cargo. Upon their arrival Down Under, 18 were eventually transferred to the RAAF by way of the USAAF’s 5th Air Force, which had assumed ownership of the Kingfishers from the Dutch upon their arrival. However, the fate of the remaining aircraft is unclear, although at least two reportedly found their way onto the battleships USS Arkansas and USS New Jersey, which were operating with the Atlantic Fleet in early 1943.24

The Dutch military had also appealed to the American military mission for 24 twin-engine Beechcraft C-45 Expediter aircraft. They were ordered for the MLD for use in training seaplane pilots,25 but the Japanese invasion also prevented their delivery. After the fall of Java, they were delivered (serial numbers A-1 through A-24) to a combined MLD and ML flight school that had been set up at Jackson, Mississippi, where training of Dutch pilots and flight crews continued until 1944.

KNILM (Koninklijke Nederlands Indische Luchtvaart Maatschappij or Royal Netherlands Indies Air Company) was the government-subsidized East Indies airline. Starting service in 1928, the civilian airline operated a diverse mixture of land, sea and amphibious aircraft along an expansive network of air routes connecting the East Indies to Europe, Australia, New Guinea, Asia and Japan. Shortly after the start of the Pacific War, many of the airline’s pilots, aircrews and ground personnel were drafted by the MLD and hastily retrained on military aircraft.

The land pilots were forced to quickly learn the intricacies of seaplane operations. In addition to seaplane flight instruction, their training included the basic regulations and rules of seamanship regarding harbor navigation, water currents, jetties, buoys and anchorages. They also had to learn advanced theories governing how and where to land depending on wind direction and force, wave motion, swell and water depth. In addition, flight crews and ground personnel accustomed to land operations learned how to service seaplanes on the water, fuel them from barges and carry out maintenance without the benefit of a dock.

In addition to its fleet of Douglas, Fokker and Lockheed land aircraft, KNILM also operated a fleet of seaplanes that was vital for the airline to effectively serve all parts of the East Indies.26 These included four-engine Sikorski S-42B flying boats and twin-engine Sikorski S-43 and Grumman G.21a seaplanes.27 During the campaign, these aircraft maintained a steady—albeit gradually diminishing—series of passenger, mail and resupply flights among Java, the East Indies, Malaya and Australia.28 The seaplanes also flew a number of very dangerous long-range missions to maintain contact with isolated colonial outposts in Dutch New Guinea.29

The primary KNILM terminal was located at Semplak on Java. Although free from air attack until mid-February, the airline would lose many planes there as Japanese fighter sweeps over the island increased. Minor hubs were scattered throughout Sumatra, Borneo, Celebes and the Flores Islands. There were also a number of primitive terminals located in Dutch New Guinea; many of these areas had no airstrips and were serviced by the airline’s seaplanes.

Flying alone along these hazardous air routes, the unarmed civilian airliners’ best defense was to avoid combat. But as the Japanese ploughed through the East Indies, they could not help but encounter KNILM aircraft. So that by the time KNILM received permission to evacuate its remaining planes to Australia on February 19, 1942, heavy losses had already been suffered. Of the 30 land and seaplanes operated by the airline on December 7, 1941, no fewer than 18 were lost. Among the civilian flying boats lost were one S-42 (flagship of the KNILM seaplane fleet), two S-43s and three of four Grumman G.21 “Goose” flying boats.

For its part, the MLD was a well-trained organization, with its primary function being to provide the fleet with air reconnaissance, photography, gunnery spotting and general support as needed. As would be expected, the level of cooperation between the air and surface arms was extremely high. After more than two decades of close cooperation, the KM and MLD had developed a very efficient system with extensive radio contact exchanged directly and efficiently between aircraft and ships. All prewar exercises carried out by the Dutch revolved around this organization. The system was sound and worked to a very high degree of precision.

But when the Allies formed a multinational command (called ABDA for the American-British-Dutch-Australian nations, which it represented) in January 1942, the British assumed strategic command of Dutch forces in the area. They insisted that all Dutch and Allied aircraft operate under a single command. The reasoning was that the Allies would have a central “clearing house” through which all air reconnaissance information would efficiently pass for distribution to Allied commands.

However, the ABDA system backfired due to inherent weaknesses in language, an inefficient command structure and overall lack of coordination and preparation on the Allies’ part. It created huge logjams of information, which often failed to reach other departments of the Allied command structure on timely basis. By that time though, they were often too old to be of much value. In his postwar memoirs, Dutch Admiral Conrad Emil Lambert Helfrich wrote,

“An urgent report previously received in 10 minutes now sometimes took up to six hours. I no longer knew what the aircraft were doing, neither did the ships [of the surface fleet] nor the base commanders. And vice versa. We were groping in the dark.”30

With the strategic air network used to guide the Dutch fleet ripped away, its ships were forced to operate blind. The damage was only slightly minimized by reconnaissance being carried out according to the strategic directives of ABDA. However, the problems previously described still existed. So in the end, the only reliable reconnaissance came from the floatplanes carried aboard the Allied cruisers. Unfortunately, these light aircraft were far too short-ranged to effectively do the job. After a fierce debate in Washington, the Dutch were put in command of REC-GROUP, an ABDA sub-command that included control of all the alliance’s valuable reconnaissance aircraft. This decision was partially based on the fact that the MLD commander, Captain G.G. Bozuwa, had superior knowledge of Dutch territory. Politics also played a role, as the Dutch government put intense pressure on President Roosevelt after being all but shut out of ABDA’s top leadership positions. This arrangement was extremely frustrating to Admiral Helfrich, as virtually all fighting south of the Philippines was taking place on Dutch territory.31

Bozuwa assumed command of REC-GROUP on January 16 and held this position until ABDA was dissolved on February 25. Captain P.J. Hendrikse assumed command of the MLD until his death on March 3, 1942. Bozuwa also technically had control of all reconnaissance units in Malaya, but no British aircraft came under ABDA control until February 7. This was because Air Chief Marshal Sir Richard E. Peirse (the senior RAF commander in Malaya) and General Sir Archibald Wavell (supreme commander of ABDA) allowed RAF and RAAF units that were nominally under Bozuwa’s command to disobey ABDA orders in order to satisfy national interests.32

The MLD’s build-up of aircraft did not go unnoticed by the Japanese, who had a large, well-entrenched espionage network throughout most of the East Indies. In turn, Dutch counterintelligence was quite sophisticated after years of successfully combating internal threats posed by Indonesian nationalist and communist groups. Building on this expertise and their many local informants, Dutch intelligence agencies were able to easily identify and control most of the Japanese operatives. Nonetheless, Japanese agents were still able to easily track the MLD build-up through readily available sources, such as newspapers, radio stations and public announcements.

Most of these spies operated through the Japanese embassy at Batavia, although Dutch, American and British codebreakers—at Bandoeng, Manila and Singapore, respectively—were able to intercept and decode their consular radio transmissions as early as the mid-1930s.33 However, Japanese embassy personnel maintained the benefit of being able to communicate with Tokyo via weekly diplomatic pouches, which could not legally be opened or searched by the Dutch.34

As a result, the Japanese were well informed of Dutch military strength through these reports, which often went into great detail. In one lengthy radio transmission from Batavia to Tokyo dated October 25, 1941,35 embassy personnel reported extensively on Dutch military and civilian air strength, including the number of Dorniers and PBYs at Morokrembangan, Menado and Ambon. This included information on the arrival at Morokrembangan from the United States of two PBYs in early September 1941 (probably Y-38 and Y-39), which were followed by three more in late October (probably Y-52, Y-53 and Y-54).

The same report also detailed that the Netherlands Purchasing Commission had recently signed $24,000,000 worth of contracts in the United States for the delivery of a large number of “two-motored medium weight bombers of the B type.” These would have been B-25 Mitchell bombers for the KNIL that did not reach Java before the Dutch surrendered. The report further revealed that the Dutch East Indies government had recently passed a supplementary appropriation bill releasing 14,340,000 guilders for the purchase of a fleet of torpedo bombers. These were the 80 Douglas DB-7 aircraft described earlier. However, the report failed to mention that another 51,000,000 guilders had also been appropriated for the purchase of 48 large seaplanes. These would have been the Sikorsky seaplanes already detailed.

From this report, the Japanese High Command also learned that the bulk of new aircraft were received and assembled at either Soerabaja or Bandoeng, where large supply depots existed. Their operatives also reported the existence of the government-subsidized civilian flying clubs, and that there were approximately 40 student pilots in each class at both Batavia and Soerabaja. There had also been an increase in the number of aircraft accidents (particularly with the army air force bombers), leading an operative to speculate that military training operations had picked up in order to man the new aircraft and those on still on order.

While some of the more sensitive information was undoubtedly gleaned from actual espionage, the bulk of it came from radio broadcasts and daily newspapers on Java. In many cases the Dutch public relations machine, which shifted into top gear following the invasion of Holland in 1940, readily released information on the strength of their military forces. Their reasoning for doing so was twofold.

First was the desire to reinforce civilian morale (both European and Indonesian) regarding the strength of Dutch military forces. Although all branches of the armed forces in the NEI were critically weak, this highly effective propaganda campaign misled many civilians into believing that their military was much stronger than it was. As a result, they were shocked when the Japanese easily overran the NEI. On a purely cosmetic level, the Dutch government needed to cast an impression of European power to the Indonesian people. To let nationalist groups see weakness on the part of the Dutch would have further amplified their cries for independence.36

Second, it was critical for the Dutch military to create an impression of strength in order to hold the Japanese at arm’s length for as long as possible. After the invasion of Holland, the Dutch government liberally promoted its military build-up in an effort to delay a Japanese invasion of the NEI. Each day gained was another in which Dutch forces in the NEI could be reorganized and strengthened. Nonetheless, it was a dangerous game that involved a delicate balancing act between revealing too much information and, perhaps, not enough. In the end it did not matter, as the Japanese were strong enough to overwhelm the Dutch at every turn.