BOBA 101

There’s never been a book about boba from a mainstream Western publisher. You’re reading the first one. When we started selling boba at a pop-up in 2011, we pulled what we could from blogs and YouTube videos to make our first drinks, like the classic milk tea. But as we grew and experimented with our own increasingly ambitious boba creations, we knew that there had to be a book one day—and we knew we could write it.

It’s for boba lovers and boba newbies alike. While this book is littered with boba culture references, we want it to feel at home in any café (not just boba shop) in America.

This chapter gives you the brass tacks, the 4-1-1, the essential lowdown on what you need to know—and what we wish we could have found in a book when we first started out.

What Is Boba?

Hi! I’m a cup of boba, also known as “bubble tea.” I’m a sweet and creamy mix of milk and tea. You drink me with a big straw that you also use to suck up tapioca balls, a.k.a. “boba,” that are dark and chewy. So I’m a drink that you can chew. I was born in Taiwan in the mid-1980s. (So I’m technically a millennial!) But now I live all over the world. And these days, there are thousands of variations on me: different teas and flavors, milk alternatives, fruit, and different toppings in place of and in addition to boba. The possibilities are kind of endless. The guys who wrote this book are going tell you a lot more. But I wanted to jump in and say hi first. Hi! This is me in my most-classic state. Hope you enjoy getting to know me and my story.

History of Boba

Who made the first cup of boba?

We don’t know that anyone truly knows.

This is what we can all agree on: Boba represents thousands of years of history and culture-bridging stirred together into a single drink. You take a classical tea preparation from ancient China and India, add milk and sugar in the 18th-century European tradition, and drop in tapioca balls, made from a root native to Brazil but popularized in snow ice desserts in 1980s Taiwan. So we can also pretty much agree that it was in Taiwan that someone put all that history into a single cup.

The rub lies in this next part, the competing origin stories of where the OG boba milk tea was first served in the 1980s. Was it Chun Shui Tang, the venerable Taichung-based restaurant chain? Or was it Hanlin Tea Room, in Tainan? We’ve been in the boba business for almost a decade, so we thought we could be Sir Walter Raleigh on the expedition to find El Dorado…the DJ Kool Herc of boba milk tea.

We started by visiting the original Chun Shui Tang on a hot, humid July afternoon.

CST, founded in 1983, feels more like a Western-style restaurant than most of Asia’s current drinks hot spots, which are mostly busy street stalls or in malls. At 2 p.m., it’s packed with families seated in wooden booths beneath decorative lanterns, the tables crowded with teas. It smells like a spa (in a good way). The CST menu claims it to be “the creator of pearl milk tea,” which is OK, but also “the origin of handmade drinks,” which seems…dubious?

As we sat there, nursing our teas in large milkshake glasses, we tried to email Hanlin Tea Room’s representatives. We couldn’t wait to crack the case, like two Encyclopedia Browns Yellows.

Eventually a CST representative, Yu Ching Wu, sat with us. Clean bob, neatly tucked blouse—she was ready for business.

After a half hour of pleasantries and guanxi (the Chinese word for building relationships), we finally took a breath and went for it: “Do you really think you invented boba milk tea?”

Yu Ching Wu dodged the question of whether CST actually invented boba milk tea…again and again. She talked about how they were inspired by seeing people in Japan putting ice in coffee back in 1983, then decided to try it with their milk tea. OK, so we have the story of the cold part of the drink…was this going to take forever? “But what about the balls??” we asked, desperate for the truth. We almost slammed the table like Tom Cruise in A Few Good Men.

And this is when the world parted. It’s like that moment when Snoop Dogg’s voice pops into “California Gurls” with Katy Perry. We had to rewind this part of the conversation over and over.

“I don’t know,” she said. “And we don’t really care.”

As the kids say, we were shook.

She explained: Maybe they did it first, maybe Hanlin Tea Room did it first. But what mattered to them was that CST made it popular. They took it global. In the sweetest Asian gangster tone, she said, “This is how we see food. It’s about consistency and doing it best, not about who did it first.”

We’d come all this way for an interview with the supposed inventor of boba milk tea, only to find out that they didn’t care if they were the inventor of boba milk tea! Sure, they had their story about that very first cup of boba milk tea, and they knew that Hanlin Tea Room did, too. But fundamentally, they didn’t care about proving they were right about being first, because they knew they were the ones that did it best.

In that moment, we realized something crucial: Maybe being Run-DMC is better than being DJ Kool Herc. The perfector, the next-leveler, may be more important than the originator.

Chi Ku

When we relistened to the audio of our interview with Yu Ching Wu, we found ourselves embarrassed. Stephanie Tanner should have been there, saying, “How rude!”

Asian culture typically values delayed gratification a bit more than American culture. The concept of guanxi relies on a long-term approach to building relationships, not just transactions. And so listening to our very direct questions, we realized we sounded a bit aggressive in context, even if in America we would be described as just “cutting to the chase.”

In the Chinese language, it is often said one must “chi ku,” which translates to “eat bitter.” It basically means to do what’s hard now (like eating bitter melon or food), so you can benefit later (because bitter food is good for you). In Taiwan, if you watch people park their cars, you’ll see people usually reverse into their parking spots, and then when they leave, they drive out easily, facing forward—they get the hard stuff out of the way first.

We recommend the book The Culture Map by Erin Meyer if you find any of this remotely interesting.

What’s Up With the Name “Boba”?

“Boba” refers to those little chewy, dark tapioca balls you’ll see in our drinks. It can be singular or plural, like many of our favorite words.

But when we say “boba” in this book, we’re often talking about the whole drink, not just the balls. As in, “Let’s go grab boba after work.” That’s how we grew up using the word. And boba doesn’t necessarily have to have tapioca pearls in it—it could be a different topping, or even no topping. (Yes, the word “topping” is also confusing because they tend to sink to the bottom, but what are you going to call them, “fillings?”) The Mandarin phrase yin liao, which translates as “beverages,” is kind of analogous to how we use “boba” in this way.

And speaking of being stuck with our name…there’s a whole other layer to this.

ANDREW: My mom’s Taiwanese, right? So when I told my mom I was starting a company called Boba Guys, I thought she’d be proud that I was promoting something from her native country. But “Andrew, Boba Guys?!” she screamed at me over the phone. “Boba Guys??”

I had no idea what she was upset about. But it turns out that back in the 1980s and ’90s, “boba” was Taiwanese slang for “big boobs.” There was even a whole fan culture around large-chested female actresses called “boba girls.”

But we’d already designed our logo and brand ID. We were beyond the point of no return for the name. We were the Boobs Guys. I had no idea. And it was only while we were writing this book that I finally got to ask Bin, “Hey, when did you know what it meant in slang?”

BIN: Oh, I knew the whole time. Since I was a kid.

ANDREW: Dude, way to leave me hanging with my mom! Thankfully it’s a little outdated as slang at this point and in Taiwan, boba is now commonly known as zhenzhu—“pearls.”

The Drinks You’ll Find in a Boba Shop

Milk Teas (奶茶)

Milk and tea and tapioca balls are the staple flavor combo in almost every boba shop in the world. It was popularized by the Taiwanese chains Hanlin Tea Room and Chun Shui Tang, and it proliferated across Taiwan in the 1980s and ’90s. The basic milk teas are traditional staple teas such as black tea, green tea, or even oolongs.

Lattes (拿铁)

A subset of milk teas, with the most notable difference being the ratio of milk to tea. Lattes, as the name would suggest, are mostly milk. They often take the form of matcha lattes in boba shops, although more shops in the U.S. are bringing other traditional Asian ingredients over to flavor these drinks. Sometimes in this book we use “latte” to refer to trending café drinks that are more akin to what you might know as a smoothie. (See Global Café Speak, this page.) You’ll see Ube Lattes, Sweet Potato Lattes, and Red Bean Lattes in this category.

Traditional Teas (茶)

Most boba shops do see themselves as tea shops, so you’ll often see several varieties of tea, like High Mountain Oolong, Red Jade a.k.a. Ruby 18, or Ceylon tea, freshly brewed, on the menu. These differ from normal iced teas in American cafés in that these teas are usually more specialized. You don’t see a lot of boba shops selling straight English breakfast hot tea.

Fruit Teas (水果茶)

A bit of a fruit tea renaissance has been emerging across all boba shops. Historically, fruit teas were flavored with syrups, but recently more boba shops are raising the quality of an average drink, so we now see natural fruit paired with a tea base, such as a jasmine or light oolong tea.

Crème Brûlée Teas / Cake Teas / Cheese Teas

This is an emerging style of milk tea featuring a rich topping that is a cross between whipped cream and buttercream spread. It’s often made with cream cheese, so some of the drinks are called “cheese teas.” Derivatives now include Crème Brûlée Teas and “Cake” Teas, which use an even thicker milk topping. You enjoy these drinks by sipping on the tea through the bottom of the straw while poking around for creamy pockets that slowly mix into the tea.

CLASSIC MILK TEA

This is what started everything. Take what is basically a simple British milk tea and put a Taiwanese dessert into it. Nothing fancy. But it’s unmistakable. The classic combination of sweetened black tea, milk, and tapioca balls is the very definition of bridging cultures with a drink.

However much you tweak it with different syrups, milks, or teas, you just hear that same beat underneath and you know what it is.

It’s like Queen and David Bowie’s “Under Pressure.” It’s in “Ice Ice Baby” and a million other songs, but no matter who’s spitting rhymes, you’d never mistake it for something else.

Like that sample, you’ll hear this basic beat throughout the recipes in this book.

MAKES 1 GLASS

RECOMMENDED TOPPINGS: BOBA, COCONUT ALMOND JELLY, GRASS JELLY

2 to 4 tablespoons toppings of your choice (optional)

5 ounces (by weight) ice cubes

2 ounces House Syrup (this page), or to taste

1 cup Brewed Boba Guys’ Black Tea (this page)

2½ ounces (¼ cup + 1 tablespoon) half-and-half (or oat milk, almond milk, soy milk, etc.) (See note.)

Fill a glass with the toppings, if using, and the ice, and then add the syrup. Pour the tea over the ice. Add the half-and-half. Stir until everything is mixed.

note:

We use half-and-half in our default recipe because it gives the drink a creamy body. It’s the closest creaminess to non-dairy creamer, which is what many boba shops actually use, and the flavor we grew up with. The half-and-half also counters the strong tea base. You can substitute with whole milk or non-dairy alternative milks, but you’ll likely need a less potent tea base to get the same balance. We prefer oat milk as the dairy alternative as it’s creamier than almond, coconut, and soy milks and it offers the same balance as half-and-half in our recipe.

Boba Guys’ Tea Blend

These days, we have an in-house product team. But back when we started out as a pop-up, we were just a couple of tea nerds in corporate America. We came at boba from a world of iterative improvement and the scientific method. We pulled on our lab coats, set up our laptops, fired up Microsoft Excel, and started testing all the possible combinations of black teas that would make the perfect base for a classic boba. It was a jittery few weeks, but we finally landed on the perfect combination: mellow and round, slightly astringent, and fiercely strong. It’s delicious and zippy, and powerful enough to stand up to the milk and sweetness. It has never changed since that first pop-up.

Assam is the maltiest of the famous black teas. It has a very smooth tea taste to it, but it’s a little mellow on its own. The reason we use Ceylon, which is from Sri Lanka, is that it has more of the tannic quality that you associate with tea and adds a punch the Assam doesn’t bring. Ceylon is also the most popular variety for traditional milk teas. Yunnan teas tend to be a little smokier. This gives our black tea blend a complexity that we just love.

MAKES 1 CUP, ENOUGH FOR 8 SERVINGS

½ cup Assam black tea leaves

¼ cup Ceylon black tea leaves

¼ cup Yunnan black tea leaves

Combine the tea leaves in a mixing bowl; stir well to fully mix. Store in an airtight container.

NOTE:

You’ll notice, most of the drinks recipes in this book are broken into different components. That’s because we encourage you to mix and match to create your own drinks!

Brewed Boba Guys’ Black Tea

Makes 1 glass

4 ounces (by weight) ice cubes

2 tablespoons Boba Guys’ Tea Blend (this page)

5 ounces filtered water, heated to 190°F

Fill a tall glass with the ice cubes. Steep the tea leaves in the water for 4 minutes. Strain the tea over the ice, and set the glass aside to allow the ice to fully melt.

House Syrup

In bartending, there are many concentrates and flavorings. We get a little nerdy with infusions in syrups, like infusing rose leaves (see Rose Syrup, this page) and spirits (see Boozy Boba Syrup, this page), but this is our go-to sweetener, rich with a nice background of depth from the brown sugar. Still, it’s got a pretty clean flavor for our classic teas. If you’re feeling ambitious, we recommend making syrups out of Asian black sugar, rock sugar, or even Japanese Kuromitsu. That’d make your milk tea next-level next-level.

You can keep this on hand in the fridge for a month.

MAKES ABOUT 2 CUPS

1 cup dark brown sugar, packed

1 cup white sugar

1 cup boiling-hot filtered water

Combine the brown and white sugars in a heatproof bowl. Whisk in the hot water until dissolved.

How Every Boba Tea Contains Thousands of Years of History

8000 BCE: The Roots (Literally) of Boba

You can’t have boba without tapioca, which is made from cassava root, which has been a staple food in South America for 10,000 years.

2437 BCE: All the Tea (Is) in China

About 5,000 years ago in China, according to legend, the mythic emperor Shennong was boiling water in a large vat in his backyard—as you do, when you are the father of Chinese medicine, agriculture, acupuncture, etc. Some leaves from a nearby wild tea tree fell into Shennong’s cauldron, and the emperor found them not only delicious but also of clear medicinal value. “Clear” being the operative word here, because Shennong had a transparent body—as you do, in mythic China. (Seriously, Google him.)

7th Century: Tang Dynasty Tea Tax

The Tang Dynasty (618–907) saw a marked rise in the popular consumption of tea, as evidenced by China’s first tea tax. In this era, tea started showing up in Buddhist, Taoist, and Confucian rituals from India to Japan, where, around this time, tea was first ground into a powder and called matcha.

13th Century: The West “Discovers” (Eye Roll) Tea

Between 700 and 800 years ago, Portuguese traders first made their way to China and Marco Polo traveled throughout the East, and the West “discovered” tea. It didn’t really become a thing until later.

1542: Portuguese Sailors and “Ilha Formosa”

Taiwan, the birthplace of boba, is an island. The Portuguese picked up cassava root, an ancient staple of native peoples in what is now Brazil, and as the Spanish and Portuguese made their presence felt on the Ilha Formosa (“beautiful island”), cassava root worked its way into the diet there.

18th Century: The U.K. Takes to Tea in a Big Way

At the beginning of the 18th century, British men drank coffee, not tea. Some British women drank tea, as it was perceived to be a daintier beverage. But the power of the British East India Company rose during the 1700s, and everything changed. As the company established trading monopolies with China, tea showed up in coffeehouses back home in the U.K., sometimes called “China drink” or “tee.” Then the empire spread to India, where the British East India Company annexed land and deployed troops, and that’s when Indian black teas, such as Assam and Ceylon, began to appear in coffeehouses.

Since coffee was more in demand throughout Europe than tea was, and since growing the market for tea was a way for the U.K. to expand its empire, the British chose tea as the drink of choice, which it remains to this day.

18th Century: Miffing, Tiffing, and a Spoonful of Sugar

OK, so our eye rolling aside, the truth is: Without British imperialism in Asia, there’d be no boba, because the U.K. is where tea was first mixed with milk and sugar.

Lactose intolerance is rare in Northern Europe, but in parts of Asia, we’re genetically wired for it. We’d never have thought to put milk in tea. So…thanks? For your conquest? U.K.? We’ll also keep the digs about all of this leading to the Opium Wars to a minimum.

1773: Meanwhile, in the British Colonies of America

It’s important to mention that without tea, there probably would be no United States of America (remember how the Boston Tea Party caused the Intolerable Acts, which caused Washington and Jefferson and those dudes to form the First Continental Congress and then, boom, Revolutionary War? Thanks, Westborough Middle School!).

Anyway, because of the British fixation with tea, Americans turned away from it from the start. This part of history is actually important to us, because it sets up the way boba is perceived as a novelty in America. You couldn’t bridge cultures with boba if we’d always drunk tea here!

1940s: A Hong Kong Remix

In the British colony of Hong Kong, people were putting their own spin on the British custom, mixing rich evaporated milk with black tea made from a strong blend, and the popularity of milk tea spread throughout China and Taiwan.

1980s: A Boba Remix

Finally, somebody (see this page) in Taiwan dropped tapioca balls, a popular topping in snow ice desserts, into a cup of sweetened milk tea, and boba was born. Shelf-stable nondairy powders were key, because they suited the outdoors/nonrefrigerated stall culture of Taiwan’s night markets, and they also skirted the whole lactose intolerance issue.

Today: Wait, Yeah, Another Remix—Boba Guys–Style

Oh, yeah, we almost forgot. Now boba’s taken root in the U.S., and we’re adding stuff like horchata to it, using local milk, and reinventing the form as American boba. So new cultures are mixing in this drink once again.

The Tea Plant

This is The BOBA Book, after all, not The TEA Book, so just the basics here!

All of what we call “tea” in America comes from a single plant. Its scientific name is Camellia sinensis, and it is native to Asia. From this plant, thousands of varieties result. Most distinctions between the different types of tea come from the different ways this plant is processed after it’s been picked.

We do know from our sourcing trips to Asia that factors of terroir come into play with tea, but generally speaking, that’s not something you need to know about to use this book. We hear tea compared to wine a lot. Which is useful to a point. But the comparison is deceptive, because there are so many kinds of grapes used to make wine, but they’re all processed in just a handful of ways. The diversity of teas all results from a single plant. It’s as if all the wine in the world was made from cabernet grapes.

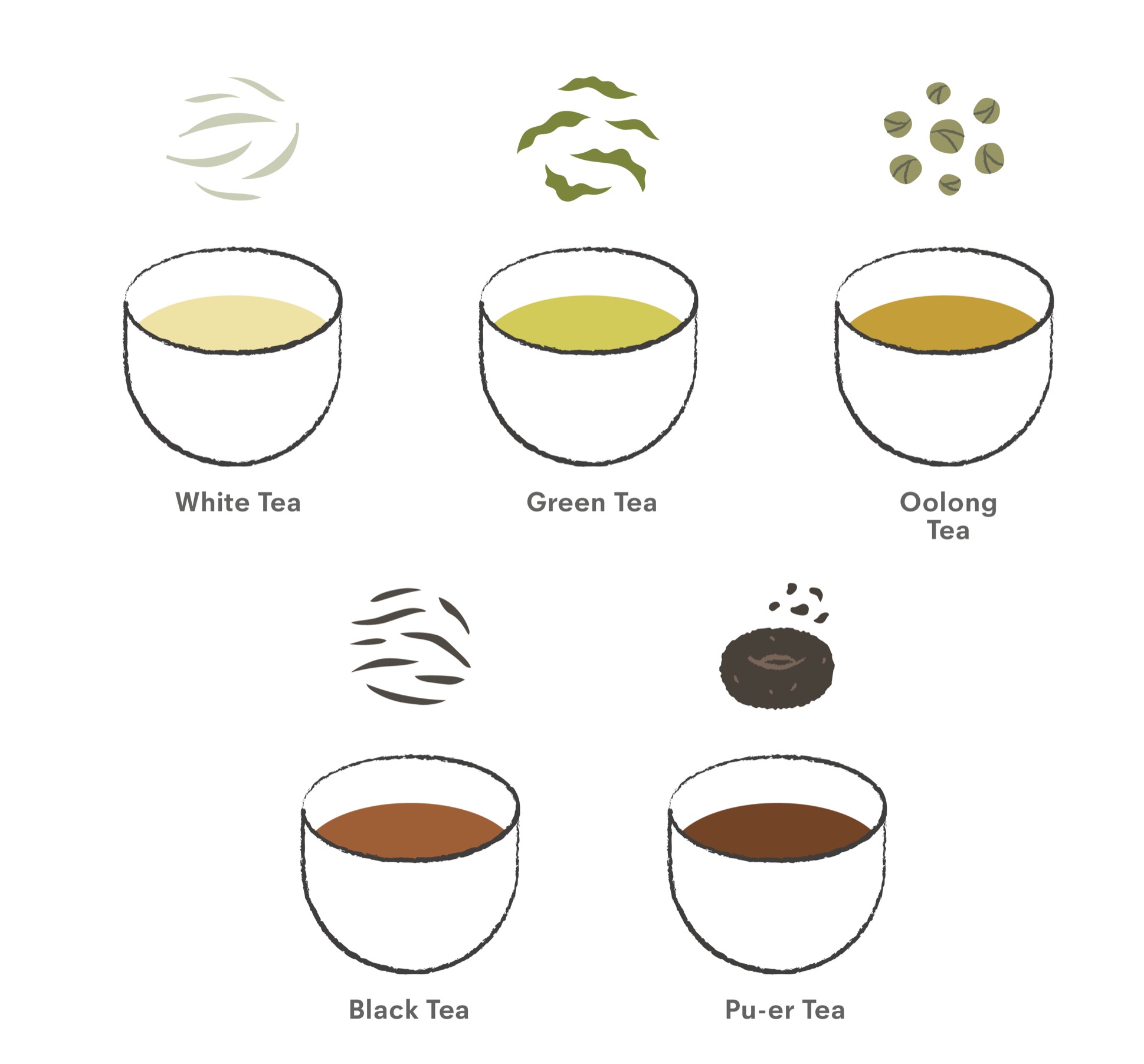

Generally, all tea is divided into six main categories.

CATEGORIES OF TEA

Types of tea can be categorized in ascending order of how oxidized or manipulated they are. Oxidation is a chemical reaction that happens when tea leaves are exposed to oxygen, which cause changes in appearance (browning) and flavor (deepening).

WHITE TEA is the rawest, most minimally handled. It is not oxidized whatsoever, so the flavor profiles are light, delicate, and sweet.

Examples: Silver Needle, White Peony

How to mix: We don’t add anything to white teas and just drink them as teas. They’re pretty subtle and elegant.

GREEN TEA has all the grassy, tannic, bright-green goodness of a recently picked plant. It’s generally not as caffeinated as black tea—although that can change dramatically depending on where it is from and how it is processed—and is known for its medicinal applications and health benefits. Green tea is loaded with antioxidants, for example.

Examples: Matcha, Dragonwell, Gyokuro, Sencha, Jasmine, Hojicha, Biluochun

How to mix: Green teas are great mixers—they have enough flavor to stand out but not to overpower. In a lot of the drinks in this book, we combine green tea with fruit. If you want to mix a green tea with alcohol, we recommend a light beer like Heineken or Michelob, soju, or shochu.

OOLONG TEA is a semi-oxidized tea. It’s almost like a cross between a black and a green tea. Its taste can vary widely on a spectrum between those two categories.

Examples: Iron Goddess, Frozen Summit, Wuyi Mountain Teas, Big Red Robe, Milk Oolong

How to mix: Oolong is very versatile, like green tea. You can use stronger alcohol like Baileys, Kahlúa, or rum, and the tea still stands up.

BLACK TEA is the most oxidized of all teas. Oxidation makes the leaves withered and pungent. The flavors in brewed black tea are very pronounced. It tends to be the most tannic of all teas. Black teas are also the most omnipresent teas in the West. (Think Lipton’s English Breakfast.)

Examples: Assam, Darjeeling, English Breakfast, Ceylon, Yunnan Black Tea

How to mix: Black tea is tough to work with as a mixer because it has such a strong, tannic flavor. It tends to overpower delicately flavored liquors. You can use very little of it, and mix it with something that will dilute and add texture, like a sturdy, fatty organic milk or milk substitute.

PU-ERH TEA is a fermented tea that tends to have a smoother, sweeter taste than black tea, although when it is brewed, it can have a similar dark liquor. Like wine, pu-erh has the reputation of “the older, the better,” although we haven’t found this always to be the case. (We find flavor tends to drop after about 75 years.) There are also “raw” and “ripe” pu-erhs. While they are both fermented, raw pu-erhs tend to be cleaner in flavor; ripe ones are fermented wet and can have a mustier flavor.

How to mix: Pu-erh can work with hard alcohol, especially smokier spirits like scotch and mezcal, or anything spicy. A pu-erh old-fashioned by the fire on a misty San Francisco night is just lovely.

HERBAL “TEA” does not come from the Camellia sinensis, aka tea plant. Rather—surprise!—it is made from herbs, other plants, or even dried fruits. It is often caffeine-free, and while it can be delicious, it tastes nothing like true tea. Sometimes they’re called “tisanes” or “infusions” because “herbal teas” has gotten such a lame reputation, but we like lots of them and use them pretty heavily in this book. (Plus, we’re from San Francisco, so we tend to like our herbals a lot.)

The Little Boba Shop that Could

This book is more about drinks and less about us. But we do want to say that there’s a shift in the industry and thanks to all of the support from our community, who have been with us since we were just a pop-up, we’re a big part of that. If you’re a boba fan, you might have noticed that we do things a little differently than most shops. We source our own teas from Asia, we let you choose your own sweetness level in our stores, and we don’t make boba from powders and milk substitutes the way many boba shops do. We’re all about #nextlevelquality. We’re not hating on boba made from powders—we grew up on it!—but we’re looking at the future, doing things a little more healthy, getting into plastic straw alternatives, working transparently, and one day we really hope the world can look at our version of boba as a model for the café of the future.

Boba-fy the World!

We want to tell you a quick story about this book.

So we were almost done with this book and we had a minor panic attack. It’s not a good time: it’s been nearly two years, we’re in the home stretch, and the printer is waiting. We were reading the proofs, looking at the amazing pictures, and we still felt something was missing.

The reason is that we don’t want to throw away our shot. This page was originally meant to be about straws (TL;DR: get some wide metal boba straws online for these drinks and skip the single-use plastics!), but we decided to use it for something else.

This is about our mandate. In our pitch for this book, we told our publisher that the boba world doesn’t get any respect. We want to quote Rodney Dangerfield here, but y’all are probably too young. So as the great poet Drake once said, “We started at the bottom, now we’re here.”

As more people get to know our style of drinks, we believe boba shops around the country will finally get their due in Western culinary history. This is the first boba book. There will be the first boba show. Then a boba conference. It is only a matter of time. We serve nearly three million unique guests every year—that’s more than many of the hottest restaurant groups and cafe concepts in America. And we do that serving drinks that most of the country hasn’t heard of before. And our story isn’t unique. This is happening in the United Kingdom, Germany, Australia, South Africa. Boba is here to stay.

Our friends and team said our first drafts of this book didn’t sound enough like us, the Boba Guys. We said there’s no origin story about us in this book because it’s not about us. It’s about the industry.

Few people know a little boba shop popularized oat milk for the masses. The pousse layering techniques now prevalent in many cafés are a direct result of boba shops. Sweetness adjustments. Yep, boba shops. Milk foam. Boba shops. Toppings like chia seeds or pudding in drinks. Boba shops. Accessible mocktails. Boba shops. Tea cocktails. Boba shops.

When boba shops around the country heard we’d be writing this book, they all had one request: make our industry proud. Well, we woke up just in time. We haven’t forgotten who we are.

Now that the engine is revved up…let’s go!

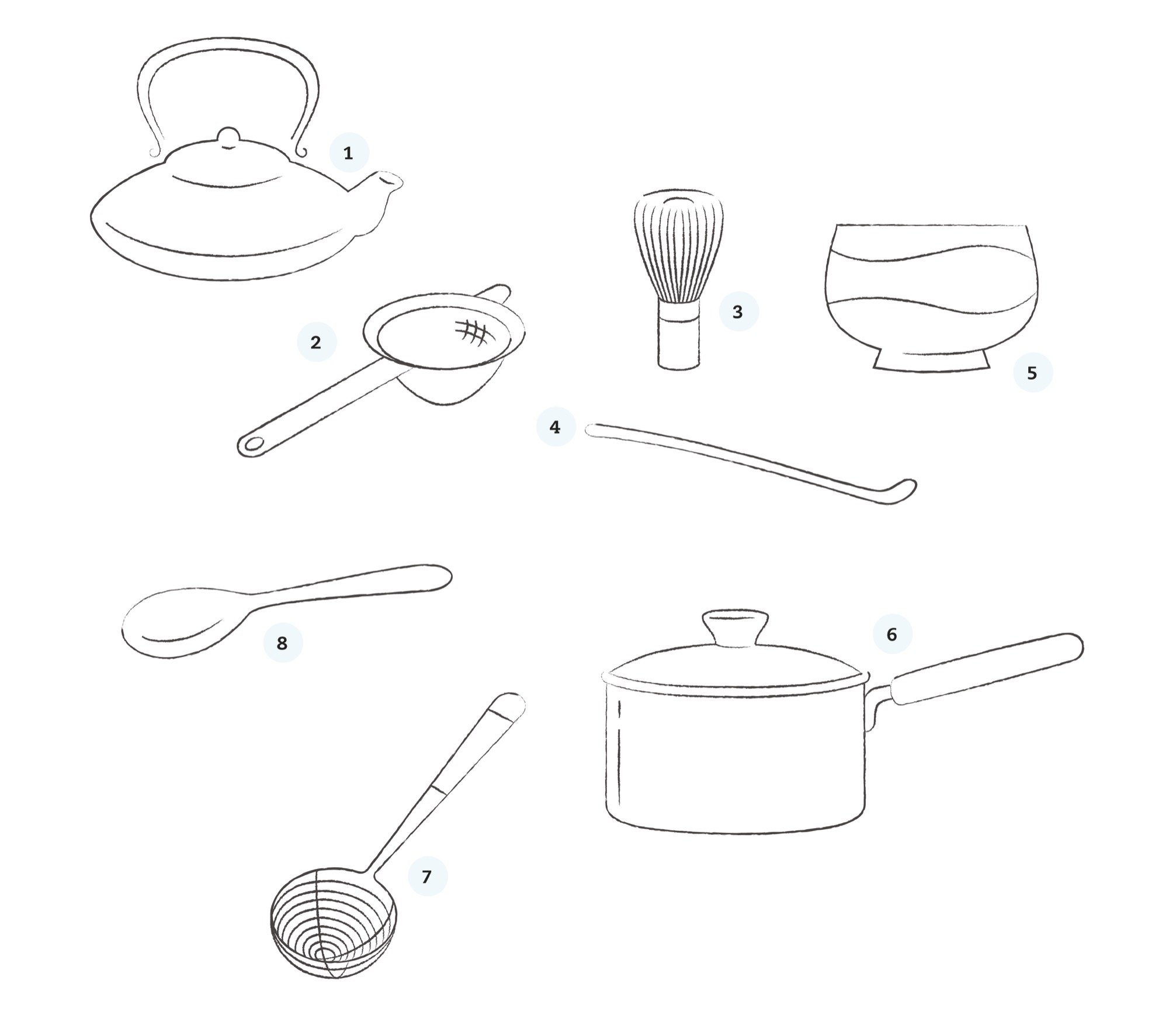

Tools of the Trade

You don’t need anything fancy to make our recipes at home to get the same results we get in our stores. But now that you’re a home-style bobarista, here are a few key tools we recommend you have on hand.

Teas

-

Kettle

-

Fine-mesh strainer, or teapot

Matcha

-

Small whisk

-

Chashaku (small matcha scoop)

-

Bowl

Boba Making

-

Saucepan

-

Small pea ladle (basically a tiny strainer)

-

Wooden spoon

Cocktails

-

Ice cube tray

-

Funnel

-

Citrus juicer

-

Measuring jigger

-

Cocktail shaker

-

Cocktail strainer

-

Bar spoon

-

Muddler