Shawn M. McClintock and Guy Potter

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) recently approved the use of transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) for the treatment of major depressive disorder (MDD) in those patients who have failed one (O’Reardon et al., 2007) antidepressant treatments. The studies documented clinical efficacy through the use of detailed measurements across time with specified depression symptom severity scales. Thus, the provision of TMS was guided by weekly clinical assessments. For example, if a patient showed improved or worsening clinical status based on the objective clinical depression rating scale, treatment was altered to either provide fewer or more sessions, respectively. Such practice is referred to as measurement-based care, which involves the use of psychometrically sound instruments, in conjunction with clinical knowledge, to provide systematic evaluation of an identified outcome to generate evidence and guide therapeutic intervention (Garland, Kruse, & Aarons, 2003).

The use of measurement-based care has received substantive empirical support (Trivedi & Daly, 2007; Trivedi et al., 2006; Harding, Rush, Arbuckle, Trivedi, & Pincus, 2011). Indeed, it can be used to integrate research findings into clinical practice, rationally guide treatment decision-making, optimize clinical outcome, and help maximize the risk/benefit ratio of the therapeutic regimen. Although measurement-based care tends to be routine in the management of chronic medical illnesses, it is not standard in psychiatric practice (Harding et al., 2011). Thus, this chapter underscores the need to include measurement-based care when guiding the delivery of TMS in clinical practice.

A major component of measurement-based care consists of integrating rating scales with the clinical decision-making process. As each clinical therapeutic setting is unique, the treatment team will need to determine practice guidelines for the implementation of measurement-based care. Particular to the rating scales, following the recommendations of Harding et al. (2011), they should be psychometrically sound, specific to the clinical patient population and disease, and practical for the clinical setting.

Given the many depression severity measurement scales in clinical and research practice, it is prudent to choose an instrument with excellent psychometric properties. A focus should be placed on reliability, validity, and sensitivity to change. For reliability, the measure should have high internal consistency and test–retest reliability. Internal consistency reliability provides an index of whether the scale items together reflect a single unidimensional aspect of the disease (e.g., depression) or whether the items reflect multiple dimensions (e.g., anxiety, anhedonia, somatic complaints). Test–retest reliability provides an index of repeated assessment consistency. Regarding validity, the measure should have convergent, concurrent, and divergent validity. High convergent validity demonstrates that the measure is associated with other measures of the same construct, and concurrent validity provides an index that the measure documents the same construct at the same time as another related measure. Last, high divergent validity demonstrates that the measure does not assess other constructs.

Patient considerations in psychometric testing include tolerability, comprehension, and cultural/demographic validity. Most depression measures reviewed here can be completed in roughly the same amount of time, though those with more items may require additional time relative to those with fewer items. Nonetheless, to our knowledge, none have been reported to increase burden of time. In general, the measures described below should be comprehensible to patients with basic reading proficiency. However, if low literacy is present, the clinician-rated scales may be more valid and preferred for the assessment.

With respect to participant age, different scales were created to maximize detection of depression symptomatology along a developmental continuum including children, adolescents, adults, and elderly adults. For instance, children and elderly adults present with different depressive symptoms, thus the depression scale needs to match the specific age group. For instance, due to age-related medical illnesses, certain rating scales may misattribute medically attributable somatic symptoms to depression in elderly adults (Linden, Borchelt, Barnow, & Geiselmann, 1995). Although most outcome studies with depressed older adults have used rating scales that can be generally applied to the adult population, age-specific measures may provide more sensitive outcome data if the items content more accurately reflects age-related symptomatology of depression.

An under researched area is the variability in clinical ratings related to ethnic and cultural differences on depression scales. For instance, some research has suggested that there is considerable variation in the endorsement of suicidal ideation and somatic complaints across cultures (Cusin, Yang, Yeung, & Fava, 2010). Many of the scales reviewed in this chapter have been translated into multiple languages; consequently, there is limited cross-cultural research regarding the psychometric properties. Although there is no compelling evidence that these scales have performed poorly in clinical trials across different countries (Cusin et al., 2010), further research is needed to provide conclusive information.

In measurement-based care, there is interest in detecting the presence or absence of a mood disorder in response to treatment. However, a more realistic goal is to track depression severity changes in response to treatment. Thus, an ideal instrument is sensitive to change across a range of depression severity and is stable across different samples. If administered by a clinician, it should have high interrater reliability to ensure that change is due to symptom change and not variability in rater judgment. As most measures fall in the broad range of 10–20 minutes, time and tolerability are roughly comparable for measures reviewed here. We suggest that it may be useful to have both clinician and self-reported measures in which case instruments with dual forms have advantages. Where cost is an issue, instruments that are in the public domain may be preferred.

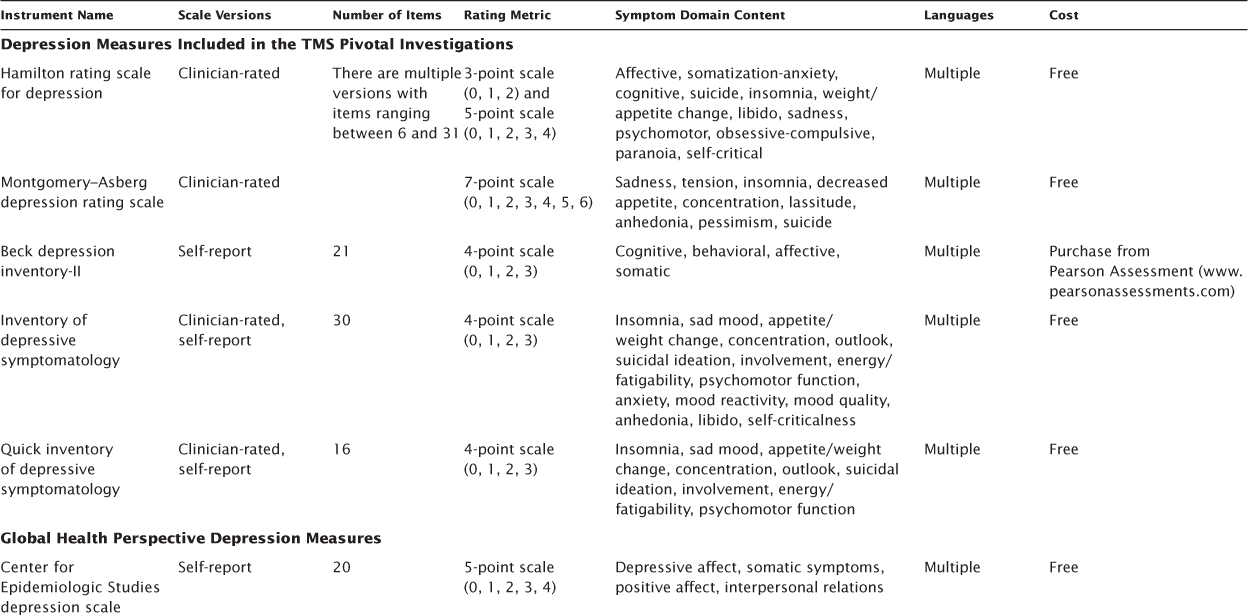

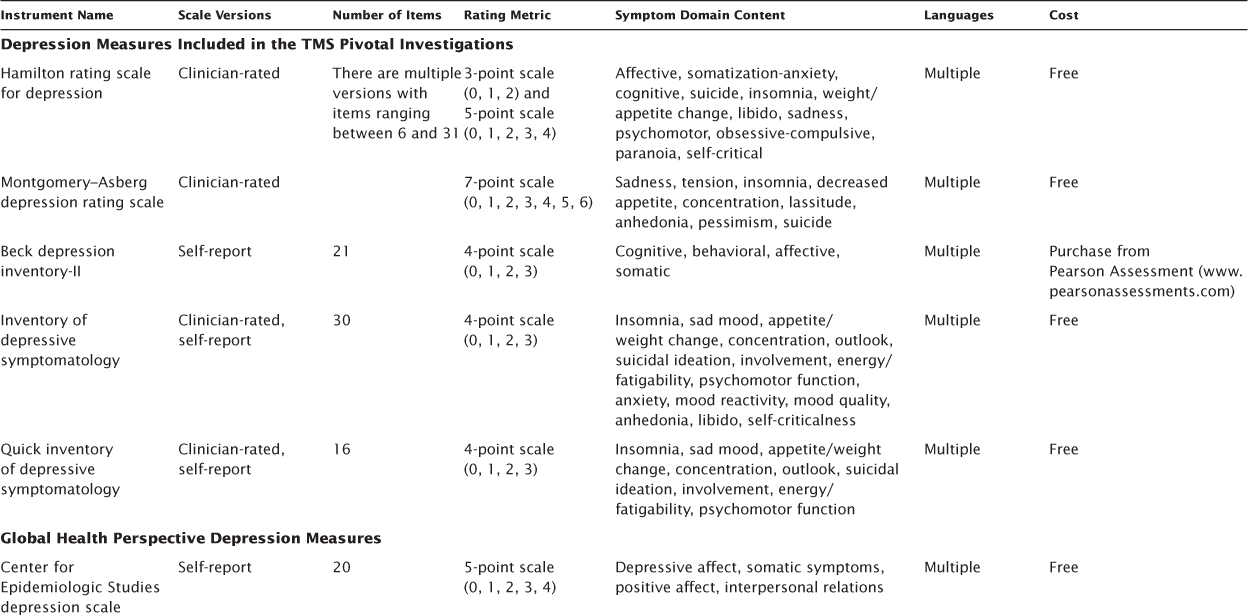

There are many available depression symptom severity measures, in many formats, and with different dimensional structures to assess only the construct of depression (uni-dimensional) or multiple neuropsychiatric constructs such as depression, anxiety, and physical ailments (multidimensional; McClintock, Haley, & Bernstein, 2011). Of importance to measurement-based care implementation, these rating scales vary in terms of item content, length of administration, and whether the assessment is administered by a trained certified clinician or is completed by the patient. In TMS research, the primary depression rating instruments included in the pivotal trials (O’Reardon et al., 2007; Janicak et al., 2008) included the Hamilton rating scale for depression (HRSD), Montgomery–Asberg depression rating scale (MADRS), Beck depression inventory-II (BDI-II), and the 30-item inventory of depressive symptomatology-self report (IDS-SR30). Other important depression symptom severity rating instruments to focus on include those that were developed from a global health perspective, which include the original and revised versions of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies depression scale (CESD, CESD-R) and the patient health questionnaire (PHQ-9) and those tailored to specific populations such as the children’s depression rating scale-revised (CDRS-R) for children and adolescents and the geriatric depression scale (GDS) for elderly adults (Table 7.1).

TABLE 7.1 Depression Symptom Severity Rating Measures

The HRSD (Hamilton, 1960) was introduced in 1960 and is the most commonly used observer rating of depression symptoms. In addition, it has been the primary outcome measure in a number of TMS investigations (Kearns et al., 1982). The most common versions used with respect to psychometric evaluation include the 17 (HRSD-17) and 24 (HRSD-24) item versions. The HRSD-24 version is often used in clinical research, but most of the psychometric data are based on the HRSD-17. The HRSD was designed for use in MDD to quantify the results of the clinical psychiatric interview (Hamilton, 1960). In practice, it is used as an index and to assess change in depression symptom severity. The HRSD is designed to be administered by a clinician and is formatted as a checklist of items on a scale of 0–4 or 0–2. The HRSD-17 total score ranges from 0 to 52, and the total score ranges from 0 to 75 for the HRSD-24. Widely accepted cutoff ranges for the HRSD-17 are as follows: >23, very severe; 19–22, severe; 14–18, moderate; 8–13, mild; and <7, normal (Kearns et al., 1982). An HRSD-17 total score <7 has been suggested as reflecting remission (Frank, 1991). The evaluation takes about 15–20 minutes to administer and is publicly available in multiple languages.

Reported reliabilities show variability, perhaps owing to the importance and challenges of maintaining standardized administration. It is noted, for instance, that internal consistency reliability increases when the HRSD-17 is used in a structured interview format (Potts, Daniels, Burnam, & Wells, 1990; Williams, 1988). Similar improvement of interrater and test–retest reliability have been reported with structured interview training (Kobak, Lipsitz, & Feiger, 2003). Although interrater reliability for the total score is adequate, it has been found to be poor for several individual items (e.g., agitation, genital symptoms, insight; Maier et al., 1988b). The HRSD-17 has good convergent validity with other measures such as the MADRS, BDI-II, and IDS (Yonkers & Sampson, 2008; Beck, Steer, & Brown, 1996; Bech et al., 1975). Most studies suggest it is sensitive to change (Yonkers & Sampson, 2008); however, one study found that change on the HRSD was more sensitive to changes in anxiety than to depression (Maier et al., 1988a).

There have been critical psychometric critiques of the HRSD. One major psychometric critique of the HRSD is poor construct validity, reflecting the absence of core diagnostic items reflected in the 4th edition, text revision of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV-TR) (2000) diagnosis of MDD, such as anhedonia, low mood reactivity, and reduced concentration (Yonkers & Sampson, 2008; Bagby, Ryder, Schuller, & Marshall, 2004). Another critique is that anxiety-related questions on the scale may reduce specificity to depression. A third major critique comes from the application of modern psychometric methods (i.e., Rasch analysis) to the HRSD-17 items, which showed that hierarchical ranking of the individual items varied across study samples (Maier, 1990). This result suggested that HRSD items might not be suitable for comparison of across-study samples. One response to this problem was the introduction of a six-item HRSD version that fits Rasch models (Bech et al., 1981; Licht, Qvitzau, Allerup, & Bech, 2005) and assesses the core symptoms of depression.

The HRSD is one of the oldest and most widely used scales for depression, but it presents a number of limitations, including lack of some core depression symptoms, poor item comparability across samples, and questionable divergent validity from general anxiety symptoms. It is also important to note that there have been many variations and modifications generated for the HRSD; thus adherence to a specific form and administration protocol is important in clinical and research settings.

The MADRS has been used as the primary outcome measure in several TMS treatment studies (Avery et al., 2008; O’Reardon et al., 2007; Lisanby et al., 2009). The intent of the MADRS is to measure depression severity, with an explicit goal of being highly sensitive to change in depression severity between placebo and psychotropic medication in treatment studies (Montgomery & Asberg, 1979). Another goal of the MADRS was to make it usable by professionals who have limited specific psychiatric training. This clinician-rated scale is composed of 10 items rated on a scale of 0–6, with anchor items at two-point intervals, with a total score range of 0–60. A MADRS score >31 differentiates individuals with severe depression from more moderate levels of severity (Muller, Himmerich, Kienzle, & Szegedi, 2003), while the following broad set of cutoffs was suggested by Snaith and colleagues (1986): >34, severe; 20–34, moderate; 7–19, mild; and 0–6, normal. Poznanski, et al. (2002) recommended an optimal cut off of <10 for remission. Completion time is 10–15 minutes. Although the clinician-rated version is the standard, there is a nine-item self-rated version (minus item 1, “Apparent Sadness”) that is highly correlated with the original (Svanborg & Asberg, 2001). The MADRS is copyrighted by the British Journal of Psychiatry, but is publicly available in multiple languages.

Internal consistency reliability estimates for the total MADRS score range from 0.76 to 0.95 (32, 33), which were improved with the introduction of a structured interview guide (Williams & Kobak, 2008). Interrater reliability was reported to range from. 89 to .97 in the original study; however, evidence of decreased reliability among a heterogeneous group of raters (psychiatrics, psychologists, psychiatric nurses, and students) suggested possible weakness in this regard (Cusin et al., 2010). Content validity is considered strong, with coverage of all core symptoms of depression with the exception of psychomotor retardation (Maier et al., 1988a).

A correlation between the MADRS and clinical version of the IDS was reported as 0.81 (Montgomery, 2000). The MADRS has shown good concurrent validity with the HRSD (.80 to .90; Muller et al., 2003; Hamilton, 2000), and both measures appear broadly comparable in their detection of symptom change (Maier et al., 1988a).

The advantages of the MADRS are a relatively brief, widely used scale with adequate psychometric properties that assesses most core features of depression. In addition to the standard version, there is a self-report version with nine of the original items. A disadvantage is that is does not include items related to melancholic and atypical depressive features, which may be important in assessment of some patients.

The goal of the original BDI and BDI-II was to measure behavioral features of depression, assess depression severity, and assess change over time. It is a widely used self-report screen for depression in normal populations and for assessing severity in depressed patients (Furakawa, 2010) Item content of the BDI was originally drawn from observations made by patients during psychotherapy, though there was a substantial revision to scale items with the introduction of the BDI-II (Beck, Steer, & Brown, 1996). The BDI-II is composed of 21 items, each item reflecting four statements on a scale of 0–3; however, the items of sleep and appetite each have a seven-item scale. The BDI-II is traditionally used as a self-report inventory, where individuals respond based on the preceding 2 weeks. The total score range is 0–63. Conventions for estimating include the following: 29–63, severe; 20–28, moderate; 14–19, mild; and 0–13 normal (Beck et al., 1996). Completion time is 5–15 minutes. It is described as written at a 5th-grade reading level and is available in English and Spanish. Copyright compliance requires that it be purchased from the test publisher (Pearson Assessments; http://www.pearsonassessments.com).

There is a large body of psychometric data on the original BDI compared to the BDI-II, but BDI data should not be extrapolated to the BDI-II due to its substantial revision. The BDI-II manual reports internal consistency reliabilities >.90 across outpatient, primary care, and medical populations (Beck et al., 1996). Test–retest data are appraised as sparse (Furakawa, 2010), but the BDI-II manual reports 1-week test–retest reliability of .93 in a sample of 26 outpatients referred for depression. The BDI-II has shown convergent validity (r = 0.71) with the HRSD (Beck et al., 1996).

The BDI-II is a well-regarded and widely used self-report questionnaire of depression symptom severity with adequate psychometric properties. Item content includes more cognitive appraisal items than other questionnaires, which may be an advantage or disadvantage depending on the application and patient population.

The design of the IDS and Quick IDS (QIDS) was to assess the severity of depressive symptoms (Rush, Gullion, Basco, Jarrett, & Trivedi, 1996; Trivedi et al., 2004). Both the IDS and QIDS are available in clinician-rated (IDS-C) and self-rated (IDS-SR) versions, though this review focuses primarily on the IDS-SR that was used in the pivotal TMS trial. The IDS-SR assesses each of the criterion symptoms of DSM-IV codified MDD, and there is also item content to capture melancholic and atypical features. It can be used to screen for depression as well as to assess symptom severity. The IDS is composed of 30 items on a scale of 0–3 with a total score range of 0–84. Conventions for rating depression severity are as follows: <12, normal; 12–23, mildly ill; moderately ill, 24–36; 37–46, moderately to severely ill, and ≥47, severely ill. Conversions are available to equate the total scores among the IDS, HRSD, and MADRS (Rush et al., 2003). The IDS takes 15–20 minutes to complete and is available for free download (www.ids-qids.org) in multiple languages.

Psychometric studies of the IDS-SR report a Cronbach’s α = .94 for a sample of both depressed and controls and α = 0.75 for depressed only (Rush et al., 1996). The IDS-SR total score was found to be highly correlated with the HRSD-17 (Rush et al., 1996). A study by Corruble et al. (1999) suggested possible higher sensitivity to change compared to the MADRS, which was attributed to the broader range of scores and item scaling.

The IDS-SR is a psychometrically sound depression scale that measures core features of depression as well as melancholic and atypical features. The number of items and wide score may make it more sensitive to mild depression severity. It also has the advantage of a matched clinician-rated version.

The CESD was developed in the late 1970s (Radloff, 1977), revised in 2004 (CESD-R; Eaton, Muntaner, Smith, Tien, & Ybarra, 2004), and is one of most well known measures given its use in large-scale epidemiologic studies. The CESD consists of 20 items that assess depressive domains of sad mood, anhedonia, insomnia, decreased appetite, low self-esteem, poor concentration, hopelessness, and helplessness. The scale is rated on a four-point item scale (0, absence of symptom; 1, mild; 2, moderate; 3, severe) and has a total range of 0 to 60. Higher scores are indicative of greater depression severity, with a cutoff of 15 meaning mild to moderate severity and 21 severe depression. The psychometric properties of the CESD have been found to be optimal with high internal consistency in community (Cronbach’s α = 0.85) and psychiatric (Cronbach’s α = 0.90) samples (Radloff, 1977; Santor, Zuroff, Ramsay, Cervantes, & Palacios, 1995). The CESD-R was created to assess the depressive domains of the DSM-IV, but maintained a length of 20 items on a 4-point scale. Thus, there is equivalence in scores between the CESD and CESD-R. The revised version also has optimal psychometric properties including high internal consistency (Cronbach’s α = 0.92), convergent validity with other psychiatric measurement scales, and was found to be unidimensional (Van Dam & Earleywine, 2011). The CESD and CESD-R are available for free download (http://cesd-r.com/about-cesdr/) in multiple languages and in clinician-rated and patient self-report versions.

The PHQ-9 was originally part of the primary care evaluation of mental disorders (PRIME-MD) and developed to provide a brief depression screening instrument that assesses the nine depressive symptom domains of the DSM-IV (Kroenke, Spitzer, & Williams, 2001). The PHQ-9 consists of nine items that are rated on a four-point scale, where 0 indicates absence of symptom, 1 mild, 2 moderate, and 3 severe. The total score ranges from 0 to 27, with a score of 5 suggesting mild depression, 10 moderate, 15 moderate to severe, and 20 severe. Last, there is an item that asks the patient to indicate if there are any employment, social, or functional difficulties. The PHQ-9 has been found to have optimal psychometric properties with high internal consistency (Cronbach’s α = 0.83), high test–retest reliability, convergent validity, and it has a unidimensional construct (Cameron et al., 2008a, 2008b). A score of 10 or greater was found to have 88% sensitivity and 88% specificity for MDD. The self-report PHQ-9 is available for free download (http://www.phqscreeners.com/) in multiple languages.

The CDRS was first introduced in the late 1970s (Poznanski, Cook, & Carroll, 1979) and was later revised (CDRS-R) in 1996 (Poznanski & Mokros, 1996). The scale was developed to capture depressive symptoms that are prominent in children and adolescents aged of 6–12 years. The CDRS-R is a 17-item scale that is typically administered by a clinician with the patient and parent(s) present in order to document the depressive symptoms such as sad mood, irritable mood, sleep problems, low self-esteem, and suicidality. The items are rated on two scales, with some rated on a six-point scale with a range of 0–5 points and others on an eight-point scale with a range of 0–7 points. The total score ranges from 0 to 113 and can be converted to a standard T-score, where a score of >40 is indicative of the presence of MDD. The CDRS-R has optimal psychometric properties with high internal consistency (Cronbach’s α = 0.85), interrater reliability (r = 0.92–0.95), test–retest reliability (r = 0.78), and convergent validity (Poznanski & Mokros, 1996). While it has been used in many large-scale studies (e.g., the Treatment for Adolescents with Depression Study, 2004; Treatment of SSRI-Resistant Depression in Adolescents Study [Brent et al., 2008], it could prove to be a lengthy interview process and may produce false-positive rates of MDD in patients with chronic medical illnesses. The instrument is available for purchase from Western Psychological Services (wpspublish.com) in only the English language.

The GDS was created to assess those depressive symptoms that are predominantly observed in elderly adults in order to maximize specificity and minimize artificial inflation due to other comorbid medical or psychiatric conditions (Yesavage et al., 1982). Further, the GDS was tailored to be user friendly by phrasing items in a yes/no format to answer a question, thereby increasing interpretability and rate of test completion. The GDS assesses multiple depressive symptoms including sadness, changes in sleep and appetite, psychomotor disturbances, decreased concentration, indecisiveness, hopelessness, worthlessness, and suicidality. There are two versions of the GDS, a long version with 30 items and a short version with 15 items (Sheikh & Yesavage, 1986). On both versions, each item is rated on a two-point scale with 0 and 1 indicating symptom absence or presence, respectively. For the long version, a score of 10–19 indicates the presence of mild depressive symptoms and a score of >20 suggests severe depressive symptoms. On the short version, a minimum score of 5 indicates the presence of depressive symptoms. While this scoring system provides a simplistic method to detect depressive symptoms, it does not allow for comprehensive interpretation of depressive symptom severity. For example, the GDS will note the presence of sad mood, but the severity level remains unclear regarding if it is mild, moderate, or severe. This information is important, particularly if multiple depressive symptoms are present, in order to document the qualitative severity level of each symptom and determine changes across time with treatment. Further, while the GDS has sound psychometric properties including high sensitivity and specificity, it may not be valid in elderly adults with cognitive difficulties (Burke, Roccaforte, & Wengel, 1991). The GDS is available for free download (http://www.stanford.edu/~yesavage/GDS.html) in multiple languages and for various electronic platforms (e.g., computer, smartphone).

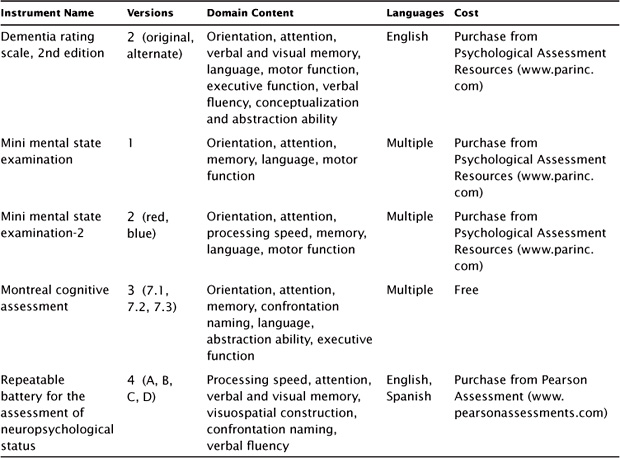

In addition to the domain of antidepressant outcome, clinical investigations of TMS have also assessed the domain of neuropsychological function (see Table 7.2). For the TMS study, the primary instrument used to screen for global cognitive function was the mini mental state examination (MMSE). Other commonly used neuropsychology screening instruments include the second edition of the MMSE (MMSE-2) and the Montreal cognitive assessment (MoCA).

The intent of the MMSE (Folstein, Folstein, & McHugh, 1975; Folstein, Folstein, & Fanjiang, 2001) was to provide a brief standardized assessment of cognitive status to assist a broader clinical assessment of cognitive function, particularly cognitive change. It is widely used to detect and track cognitive change, especially in the context of dementia, but is not recommended as a tool for diagnosing dementia. The MMSE is composed of 30 items rationally grouped into domains including orientation, (memory) registration, attention and concentration, (memory) recall, language, and visual construction. The total score ranges from 0 to 30. A cutoff of 24 is often presented as an indication of dementia, but the sensitivity and specificity of this cutoff varies across samples and particularly by age, ethnicity, and education level (MacDowell, 2006). The MMSE takes approximately 10 minutes to administer, can be administered by trained staff, and is relatively easy to score. The MMSE is copyrighted, requires purchase (Psychological Assessment Resources, Inc.; http://www4.parinc.com), and is available in multiple languages.

TABLE 7.2 Neurocognitive Screening Instruments

Internal consistency of the MMSE is moderate but variable, with Cronbach’s α ranging from 0.55 to 0.96; however, reliability of the total score is higher and reaches correlations >0.80 (Foreman, 1987; Salmon, 2008). Interrater reliability is high. Test–retest reliability is adequate and higher over brief retest intervals (i.e., 1 day) than longer intervals (MacDowell, 2006). With respect to convergent validity, the MMSE is correlated with performance on multiple neuropsychological and functional measures.

An advantage of the MMSE is that it is used in many studies because of its brevity and is regarded as a “lingua franca” for cognitive status. While it is generally regarded as able to detect moderate and severe cognitive decline, it has limitations in the detection of mild or subtle cognitive dysfunction due to a low ceiling of difficulty; narrow range of cognitive abilities assessed; and differential sensitivity to age, education, and ethnicity (Tombaugh & McIntyre, 1992). The MMSE has limitations in MDD and other neuropsychiatric conditions (Faustman et al., 1990), in part, because of limited assessment of the types of executive function and information processing speed deficits that characterize cognitive dysfunction in MDD.

MMSE-2 (Folstein, Folstein, White, & Messer, 2010) was recently introduced, and incorporated advances to overcome limitations of the original version. The MMSE-2 consists of three different lengths including a brief, standard, and expanded form. Each version has two versions referred to as the blue and red forms in order to minimize practice effects with repeat assessments. The brief version only measures orientation, and registration and recall of simple words for a total of 16 points. The standard version is similar to the original MMSE and measures global cognitive functions including orientation, attention, confrontation naming, memory, language, comprehension, and motor function, for a total of 30 points. The expanded version is suggested to be more sensitive to subcortical dementia by also measuring story memory and processing speed, for a total of 90 points. The user manual provides useful clinical information for the scores: sensitivity, specificity, percent correctly classified, positive predictive power, negative predictive power, and reliable change for each of the 3 versions of the scale. The authors of the MMSE-2 have undertaken a comprehensive effort to address the limitations of the original MMSE. While this is promising, the newness of the instrument precludes a critical review of the new scales in independent research, particularly with respect to MDD. The MMSE-2 is copyrighted, requires purchase (Psychological Assessment Resources; http://www4.parinc.com/), and is available in multiple languages.

The MoCA (Nasreddine et al., 2005) is a measure of global cognitive function that was designed to assess similar domains of cognitive function as with the MMSE and MMSE-2 in <10 minutes. Importantly, it also measures executive function through items of cognitive flexibility, abstraction, and phonemic fluency. The item content is organized into neuro-cognitive domains, and total scores are produced for each domain and a total global score that ranges from 0 to 30. A cutoff score of 26 was found to be highly sensitive in discerning between normal cognitive function and mild cognitive impairment, with scores <26 indicative of neurocognitive difficulties. The psychometric properties are optimal with high internal consistency (Cronbach’s α = 0.83), test–retest reliability (r = 0.92), and sensitivity and specificity to neurocognitive impairment. A recent population-based study found that the total score should be interpreted based on age and education levels (Rossetti, Lacrit, Cullum, & Weiner, 2011). When designing the MoCA, the test developers also created two alternate forms for repeat test administration in order to minimize practice effects at follow-up evaluations. The MoCA is available for free download (http://www.mocatest.org/) in multiple languages and with available alternate forms for select languages.

In addition to the above three screening instruments, other neuropsychological screening tools can be implemented in a host of clinical settings. These instruments include the dementia rating scale-2nd edition (DRS-2; Jurica, Leitten, & Mattis, 2001) and the repeatable battery for the assessment of neuropsychological status (RBANS; Randolph, 2012). The DRS-2 takes approximately 15–30 minutes to administer, with several pass/fail screening items that direct the total number of administered items. It has often been used to provide a more comprehensive dementia screen than the MMSE and has empirical scores on several subscales of cognitive function. At least one study has suggested that it is superior to the MMSE in screening for cognitive impairment in late-life depression, as it is more sensitive to cognitive impairment that would be classified as normal on the MMSE.

The RBANS is more comprehensive in scope than the DRS-2 and takes approximately 30 minutes to administer, though it may take longer in older adults with MDD. It was designed to be sensitive to dementia and has been used as an intermediate assessment across multiple clinical populations, often bridging the gap between a brief cognitive status screen and a comprehensive neuropsychological test battery. It also provides empirical scores for subscales of cognitive function. These instruments have been well researched, have stable psychometric properties, and may have unique advantages (e.g., better sensitivity to neurologic impairment) depending on the clinical population.

As TMS continues to be implemented as an antidepressant treatment strategy, its rational use will be guided by both clinical wisdom and measurement-based care. Such a strategy will prove beneficial as it capitalizes upon the clinical knowledge of the treatment team, the therapeutic relationship between the treatment team and the patient, and the use of rating instruments to provide substantive evidence. Although measurement-based care is not standard clinical practice in most of psychiatry, it is slowly becoming part of that practice and will continue to grow given the many benefits. When implementing measurement-based care, the treatment team should select those rating instruments that are psychometrically sound, specific to the clinical patient population and disease, and practical for the clinical setting. The goal is for the instruments to enhance, rather than hinder or burden, the therapeutic regimen.

Integrating measurement-based care with the provision of TMS confers many advantages, including the systematic monitoring and assessment of change in depressive symptoms during the course of treatment, provision of education to the patient regarding depressive symptomatology, and evidence-guided treatment strategies for neuropsychiatric disease. Continued research is needed regarding the antidepressant effects of TMS in order to address many unanswered questions, such as optimal dosing strategies and length of treatment courses. Integration of measurement-based care into clinical practices will help to provide useful information to further guide the psychiatric field in refining TMS clinical practice.

Avery, D. H., Isenberg, K. E., Sampson, S. M., Janicak, P. G., Lisanby, S. H., Maixner, D. F., … George, M.S. (2008). Transcranial magnetic stimulation in the acute treatment of major depressive disorder: clinical response in an open-label extension trial. Journal Clinical Psychiatry, 69(3), 441–451.

Bagby, R.M., Ryder, A. G., Schuller, D. R., & Marshall, M. B. (2004). The Hamilton Depression Rating Scale: has the gold standard become a lead weight? American Journal Psychiatry, 161(12), 2163–2177.

Bech, P., Allerup, P., Gram, L. F., Reisby, N., Rosenberg, R., Jacobsen, O., & Nagy, A. (1981). The Hamilton Depression Scale—Evaluation of Objectivity Using Logistic-Models. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 63(3), 290–299.

Bech, P.I., Gra, L. F., Dein, E., Jacobsen, O., Vitger, J., & Bolwig, T. G. (1975). Quantative rating of depressive states: correlation between clinical assessment, Beck’s self-rating scale, and Hamilton’s objective rating scale. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 51(3), 161–170.

Beck, A. T., Steer, R. A., & Brown, G. A. (1996) Manual for the Beck Depression Inventory-II. San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation.

Brent, D., Emslie, G., Clarke, G., Wagner, K. D., Asarnow, J. R., Keller, M., … Zelazny, J. (2008). Switching to another ssri or to venlafaxine with or without cognitive behavioral therapy for adolescents with ssri-resistant depression: The tordia randomized controlled trial. Journal American Medical Association, 299(8), 901–913.

Burke, W. J., Roccaforte, W. H., & Wengel, S.P. (1991). The Short Form of the Geriatric Depression Scale: A Comparison With the 30-Item Form. Journal Geriatric Psychiatry Neurology, 4(3), 173–178.

Cameron IM, Crawford JR, Lawton K, et al. (2008a). Assessing the validity of the PHQ-9, HADS, BDI-II and OIDS-SR-sub-1-sub-6 in measuring severity of depression in a UK sample of primary care patients with a diagnosis of depression: Study protocol. Primary Care Community Psychiatry, 13(2), 67–71.

Cameron, I. M., Crawford, J. R., Lawton, K., & Reid, I. C. (2008b). Psychometric comparison of PHQ-9 and HADS for measuring depression severity in primary care. British Journal General Practice, 58(546), 32–36.

Corruble, E., Legrand, J. M., Duret, C., Charles, G., & Guelfi, J. D. (1999). IDS-C and IDS-sr: psychometric properties in depressed in-patients. Journal Affective Disorders, 56(2–3), 95–101.

Cusin, C., Yang, H., Yeung, A., & Fava, M. (2010). Rating scales for depession. In L. Baer, & M. A. Blais (Eds). Clinical rating scales and assessment in psychiatry and mental health (pp. 7–36). New York: Humana Press.

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV-TR) (2000). American Psychiatry Association: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition, Text Revision. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Association.

Eaton, W. W., Muntaner, C., Smith, C., Tien, A., & Ybarra, M. (2004). Center for Epidemiologic Studies depression scale: review and revision (CESD and CESD-R). In M. E. Maruish ME (Ed.). The use of psychological testing for treatment planning and outcomes assessment (3rd ed.) (pp. 363–77). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Folstein, M. F., Folstein, S. E., & Fanjiang, G. (2001). Mini-mental state examination: clinical guide and user’s guide. Lutz, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources.

Folstein, M. F., Folstein, S. E., & McHugh, P. R. (1975). Mini-mental state. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. Journal Psychiatric Research, 12, 189–198.

Folstein, M. F., Folstein, S. E., White, T., & Messer, M. A. (2010). Mini-mental state examination (2nd ed.). Lutz, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources, Inc.

Foreman, M. D. (1987). Reliability and validity of mental status questionnaires in elderly hospitalized-patients. Nursing Research, 36(4), 216–220.

Furukawa T. A. (2010). Assessment of mood: Guide for clinicians. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 68(6), 581–589.

Garland, A. F., Kruse, M., & Aarons, G. A. (2003). Clinicians and outcome measurement: What is the use? Journal Behavioral Health Services Research, 30, 393–405.

Hamilton, M. (1960). A rating scale for depression. Journal Neurology, Neurosurgery, Psychiatry, 23, 55–61.

Hamilton, M. (2000). Hamilton rating scale for depression (HAM-D). In J. A. Rush (Ed.), Handbook of psychiatric measures (pp. 526–528). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association.

Harding, K. J. K., Rush, A. J., Arbuckle, M., Trivedi, M. H., & Pincus, H. A. (2011). Measurement-based care in psychiatric practice: A policy framework for implementation. Journal Clinical Psychiatry, 72, 1136–1143.

Hawley, C. J., Gale, T. M., & Sivakumaran, T. (2002). Defining remission by cut off score on the MADRS: selecting the optimal value. Journal Affective Disorders, 72(2), 177–184.

Janicak, P., O’Reardon, J., Sampson, S., Husain, M., Lisanby, S., Rado, J., … Demitrack, M. (2008). Transcranial magnetic stimulation in the treatment of major depressive disorder: a comprehensive summary of safety experience from acute exposure, extended exposure, and during reintroduction treatment. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 69(2), 222–232.

Jurica, P. J., Leitten, C. L., & Mattis, S. (2001). DRS-2: Dementia rating scale-2 professional manual. Lutz, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources, Inc.

Kearns, N. P., Cruickshank, C. A., McGuigan, K. J., Riley, S. A., Shaw, S. P., & Snaith, R. P. (1982). A comparison of depression rating scales. British Journal Psychiatry, 141, 45–49.

Kobak, K. A., Lipsitz, J. D., & Feiger, A. (2003). Development of a standardized training program for the Hamilton Depression Scale using internet-based technologies: results from a pilot study. Journal Psychiatric Research, 37(6), 509–515.

Kroenke, K., Spitzer, R. L., & Williams, J. B. W. (2001). The PHQ-9. Journal General Internal Medicine, 16(9), 606–613.

Licht, R. W., Qvitzau, S., Allerup, P., & Bech, P. (2005). Validation of the Bech-Rafaelsen melancholia scale and the Hamilton depression scale in patients with major depression; is the total score a valid measure of illness severity? Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 111(2), 144–149.

Linden, M., Borchelt, M., Barnow, S., & Geiselmann, B. (1995). The impact of somatic morbidity on the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale in the very old. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 92(2), 150–154.

Lisanby, S. H., Husain, M. M., Rosenquist, P. B., Maixner, D., Gutierrez, R., Krystal, A., … George, M. S. (2009). Daily left prefrontal repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation in the acute treatment of major depression: clinical predictors of outcome in a multisite, randomized controlled clinical trial. Neuropsychopharmacology, 34, 522–534.

MacDowell, I. (2006). Measuring health (3rd ed). New York: Oxford University Press.

Maier W. (1990). The Hamilton Depression Scale and its alternatives. A comparison of their reliability and validity. Psychopharmacology Services, 9, 64–71.

Maier, W., Heuser, I., Philipp, M., Frommberger, U., & Demuth, W. (1988a). Improving depression severity assessment—II. Content, concurrent and external validity of three observer depression scales. Journal Psychiatric Research, 22(1), 13–19.

Maier, W., Philipp, M., Heuser, I., Schlegel, S., Buller, R., & Wetzel, H. (1988b). Improving depression severity assessment—I. Reliability, internal validity and sensitivity to change of three observer depression scales. Journal Psychiatric Research, 22(1), 3–12.

McClintock, S. M., Haley, C., & Bernstein, I. H. (2011). Psychometric considerations of depression symptom rating scales. Neuropsychiatry, 1(6), 611–623.

Montgomery, S. A., & Asberg, M. (1979). A new depression scale designed to be sensitive to change. British Journal Psychiatry, 134, 382–389.

Muller, M. J., Himmerich, H., Kienzle, B., & Szegedi, A. (2003). Differentiating moderate and severe depression using the Montgomery-Asberg depression rating scale (MADRS). Journal Affective Disorders, 77(3), 255–260.

Nasreddine, Z. S., Phillips, N. A., Bédirian, V., Charbonneau, S., Whitehead, V., Collin, I., … Chertkow, H. (2005). The Montreal cognitive assessment, MoCA: a brief screening tool for mild cognitive impairment. Journal American Geriatrics Society, 53(4), 695–699.

O’Reardon, J. P., Solvason, H. B., Janicak, P. G., Sampson, S., Isenberg, K. E., Nahas, Z., … Sackeim, H. A. (2007). Efficacy and safety of transcranial magnetic stimulation in the acute treatment of major depression: a multisite randomized controlled trial. Biological Psychiatry, 62, 1208–1216.

Potts, M. K., Daniels, M., Burnam, M. A., & Wells, K. B. (1990). A structured interview version of the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale: evidence of reliability and versatility of administration. Journal Psychiatric Research, 24(4), 335–350.

Poznanski, E. O., Cook, S. C., & Carroll, B. J. (1979). A depression rating scale for children. Pediatrics, 64, 442–450.

Poznanski, E., & Mokros, H. (1996). Children’s depression rating scale-revised (CDRS-R) manual. Los Angeles, CA: Western Psychological Services.

Radloff, L. S. (1977). The CES-D scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement, 1(3), 385–401.

Randolph, C. (2012). Repeatable battery for the assessment of neuropsychogical status update manual. San Antonio, TX: Pearson.

Rossetti, H. C., Lacrit, L. H., Cullum, C. M., & Weiner, M. F. (2011). Normative data for the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) in a population-based sample. Neurology, 27(77), 1272–1275.

Rush, A. J., Gullion, C. M., Basco, M. R., Jarrett, R. B., & Trivedi, M. H. (1996). The inventory of depressive symptomatology (IDS): psychometric properties. Psychological Medicine, 26(3), 477–486.

Rush, A. J., Trivedi, M. H., Ibrahim, H. M., Carmody, T. J., Arnow, B., Klein, D. N.… Keller, M. B. (2003). The 16-item quick inventory of depressive symptomatology (QIDS), clinician rating (QIDS-C), and self-report (QIDS-SR): a psychometric evaluation in patients with chronic major depression. Biological Psychiatry, 54(5), 573–583.

Salmon, D. (2008). Neuropsychiatric measures for cognitive disorders. In A. J. Rush, M. B. First, & D. Blacker (Eds.), Handbook of psychiatric measures (pp. 397–346). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Publishing.

Santor, D. A., Zuroff, D. C., Ramsay, J. O., Cervantes, P., & Palacios, J. (1995). Examining scale discriminability in the BDI and CES-D as a function of depressive severity. Psychological Assessment, 7(2), 131–139.

Sheikh, J. I., & Yesavage, J. A. (1986). Geriatric depression scale (GDS): recent evidence and development of a shorter version. Clinical Gerontologist: Journal Aging Mental Health, 5(1–2), 165–173.

Snaith, R. P., Harrop, F. M., Newby, D. A., & Teale, C. (1986). Grade scores of the Montgomery-Asberg depression and the clinical anxiety scales. British Journal Psychiatry, 148, 599–601.

Svanborg, P., & Asberg, M. (2001). A comparison between the Beck depression inventory (BDI) and the self-rating version of the Montgomery Asberg depression rating scale (MADRS). Journal Affective Disorders, 64(2–3), 203–216.

Tombaugh, T. N., & McIntyre, N. J. (1992). The mini-mental state examination: a comprehensive review. Journal American Geriatrics Society, 40, 922–935.

Treatment for Adolescents With Depression Study (TADS) Team. (2004). Fluoxetine, cognitive-behavioral therapy, and their combination for adolescents with depression: Treatment for adolescents with depression study (tads) randomized controlled trial. Journal American Medical Association, 292(7), 807–820.

Trivedi, M. H., & Daly, E. J. (2007). Measurement-based care for refractory depression: A clinical decision support model for clinical research and practice. Drug Alcohol Dependence, 88(Suppl 2), S61–S71.

Trivedi, M. H., Rush, A. J., Ibrahim, H. M., Carmody, T. J., Biggs, M. M., Suppes, T., … Kashner, T. M. (2004). The inventory of depressive symptomatology, clinician rating (IDS-C) and self-report (IDS-SR), and the quick inventory of depressive symptomatology, clinician rating (QIDS-C) and self-report (QIDS-SR) in public sector patients with mood disorders: a psychometric evaluation. Psychological Medicine, 34(1), 73–82.

Trivedi, M. H., Rush, A. J., Wisniewski, S. R., Nierenberg, A. A., Warden, D., Ritz, L., … STAR*D Study Team. (2006). Evaluation of outcomes with citalopram for depression using measurement-cased care in STAR*D: implications for clinical practice. American Journal Psychiatry, 163(1), 28–40.

Van Dam, N. T., & Earleywine, M. (2011). Validation of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies depression scale—revised (CESD-R): pragmatic depression assessment in the general population. Psychiatry Research, 186(1), 128–132.

Williams, J. B. (1988). A structured interview guide for the Hamilton depression rating scale. Archives General Psychiatry, 45(8), 742–747.

Williams, J. B., & Kobak, K. A. (2008). Development and reliability of a structured interview guide for the Montgomery Asberg depression rating scale (SIGMA). British Journal Psychiatry, 192(1), 52–58.

Yesavage, J. A., Brink, T. L., Rose, T. L., Lum, O., Huang, V., Adey, M., & Leirer, V. O. (1982). Development and validation of a geriatric depression screening scale: a preliminary report. Journal Psychiatric Research, 17(1), 37–49.

Yonkers, K. A., & Sampson, J. A. (2008). Mood disorders measures. In A. J. Rush, M. B. First, & D. Blacker (Eds.). Handbook of psychiatric measures (pp. 499–528). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Publishing.