We’ve covered you; we’ve covered your boss. Now it’s time to meet the rest of your management role. This section looks at what happens when you join the team as a Lead Artist, new to the role of managing personalities, artwork and projects.

I expect you’ll inherit an art team composed of mixed abilities and personalities. Part of your new role will be identifying artists on your team, those that are motivated and working well and the few who need help. So lets explore further whats involved in shaping your dream team:

• Personality wheel

• What makes a key employee?

• Creating inspiration

• Losing team members

• Conflict resolution

• Conducting Personal Development Reviews

• See a problem? Deal with it!

So, before you hide under a pile of schedules, meetings, pipelines and asset reviews, you’ll want to get to know your team and understand how they operate. My biggest recommendation would be this: let your artists know more about you, then spend some time doing a little digging, finding nuggets of information about your team that will aid your leadership transition.

TIP: Arrange a meeting with the team and the Art Director, during which you can do a simple Q&A to let them know who you are, where you have come from, what you are looking forward to and how you operate. No messing, no guessing. It sounds stupid and overbearing, but done right, it helps set expectations for the team. Often frustrations can arise when artists think you should do or know something and can’t understand why it’s not happening to their liking (of course most won’t voice this). By setting out your stall, there can be no misunderstandings. The added benefit is that this chat is the start of you defining your authority within the group.

TIP: At desk, spend five or ten minutes with each artist getting to know their backgrounds, what they like doing and anything that they would like you to try to solve. Don’t make the mistake of promising you’ll fix everyone’s problems, but if you see easy wins, get them in early to make a good impression.

TIP: Send everyone an online questionnaire, and it’s best if they are targeted. For example, pick which three things from a list they would like solved first (you might have been hired mid-way through a project).

I’m sure you can think of more or better. Not all companies will grant you the time (especially for Tip Two), and will want you to just ‘get on with it’. But spending time at the start can reap rewards, when done well.

These are my recommendations for letting your team get to know you, setting expectations and making a good impression. Before doing your big sell, though, I suggest you read the whole of Level 4 for an overview of the challenges, starting with your art team.

Understanding the make-up of your team is paramount. Skills are important too. But your team’s personalities and how you combine and manage them are the key to a well-oiled art machine. Like a master baker, how you use and combine these top-tier ingredients can go well, or bring the whole team down.

In 4.1 we looked at Tilt 365 and 16 Personalities for evaluating your own personality and behaviours. These systems can be used for your team too, but in a more managed way. Being aware of the factors below can help you best decide how to solve your challenges. While no silver bullet, it’s another part of your kit.

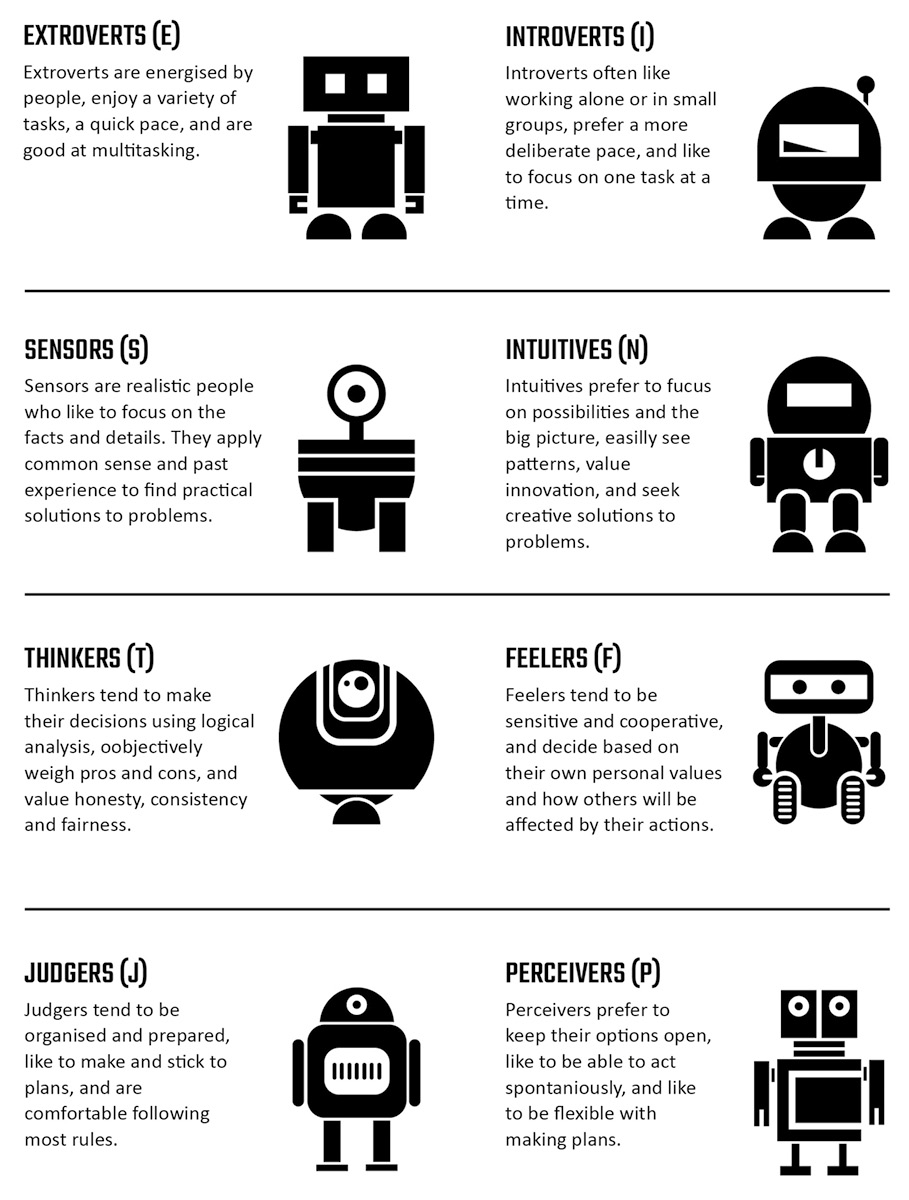

The industry standard for identifying personality types is the ‘Myers Briggs Type Indicator’, although opinion is divided on its usefulness. I see it as a possible part of your toolkit for understanding your team. The two American psychologists Myers and Briggs based their work on the findings of Carl Jung who believed that humans experience the world using four basic psychological functions: sensing, intuiting, feeling and thinking. Myers Briggs can be further researched here: https://www.myersbriggs.org/my-mbti-personality-type/mbti-basics/the-16-mbti-types.htm

It describes the four pairs used for the test definitions shown in Figure 16:

• Introversion/extraversion - (I/E)

• Sensation/intuition - (S/N)

• Thinking/feeling - (T/F)

• Judgement/perception - (J/P)

Figure 16. Personality types

This theory builds and expands upon our earlier venture into introverts and extraverts and their leadership styles. Using this builds more layers, nuance and understanding for you and your team. There is no good, bad, weak, or strong result. The Lead Artist role is all about making the best use of your team, fitting the right people together, reducing risk of conflict, improving team cohesion and bonding. At the end of the day, managing a team is no simple task and better armed is better prepared.

Clearly, I’m just brushing the surface of this subject and am no trained psychologist, but I see the value in observing the dynamics of the team and who works well with whom. It makes complete sense to choose my team with some additional knowledge of how they operate and if you can improve how you manage your team, why wouldn’t you?

Now that you understand a little more about behaviours, let’s look at how your team might operate and identify the heavy hitters, sliders, and workers you’ve inherited.

Imagine the team you work with is a hive, in which everyone has a role to play. As the Lead Artist you’ll notice how your team works, their ability, their commitment, and how they react to changes of direction, stress and organisational skills.

You’ll quickly flag a who’s who in your mind. This is important as you want to play your team to their strengths, knowing which artists can deliver based on minimal guidance, who can deal with complex tasks, who is more technical, and who is more artistic. You also need to know who does the bare minimum, who might struggle, and who are the heavy hitters and supporters. These notes will help you define the organisation of your team.

I couldn’t resist using these definitions as often a hard-working artist can be known as a 'good worker bee'. Also, I’m in Manchester, where the city emblem is the bee! However, standard practice or not, it’s a simple method of classifying your artists (in your head).

Worker Bee – These are the artists who day-in and day-out deliver the goods; you can give them any task and it gets done. It might not be award-winning art, but it’s good enough for the game and sits well with other assets. They play nice with others and know how to work with a pipeline and other team members.

Killer Bee – Also known as a heavy hitter. These are the artists who you know, given any task, can make amazing artwork both visually and technically. You give them minimal information and boom, something magical appears. Any task, no matter what, short deadline, impossible task, they just kill it, time after time.

Queen Bee – The Art Director (AD).

Right-Hand Bee – That would be you, the Lead Artist, working with the AD and pushing the team to achieve what’s needed for the project.

Sickly Bee – The artist who isn’t pulling their weight. They ultimately let the others carry the load by working slowly, delivering subpar artwork, missing deadlines, or infecting the group with a negative attitude. Team morale is an important part of how well your team operates and how much work they deliver. If you don’t deal with it, it won’t go unnoticed and can affect your standing within the group.

TIP: If your team isn’t working, identify the reason and switch it up. With the AD, you’re part of the long-term vision, don’t be afraid of being flexible. The definition of insanity is doing the same thing over and over and expecting different results, so make changes where you need, mixing it up to get new results!

On the topic of morale, a motivated team can achieve far more than a downbeat one for obvious reasons. You are part of that mix. With help from the AD, you can work to create strong team cohesion and turn them into an art-making machine!

Go team? High fives? Chuggin’ beer? Standing in the park capturing Pokémon? What does it take to achieve the active ingredients that make some teams go far and fast? Well, it’s not as simple as that, as what I’ve described is more team morale than cohesion. While morale plays a good part in this, there are some stages to consider when teams are formed with the common goal of making a game.

Let’s start with the fundamental question: what does team cohesion mean? It’s best described as when a team works together to solve a common goal, each feeling they’ve been able to contribute, which builds high levels of satisfaction, self-esteem and confidence. Ask Bruce, he knows all about it!

While 1965 seems like another world away, Bruce Tuckman must have hit upon something fundamental; a good part of the world appears still to be working to his theory that group dynamics have five stages of development, all of which play a part in the success of your team. Like other aspects I’ve mentioned in this book, I see this as guiding theory, something to be aware of as the project progresses. It is a process and not necessarily something you can achieve immediately. Instead, organically and naturally try to foster it so the team does the growing themselves.

Figure 17. Team development

In my experience, Figure 17 doesn’t always happen as clearly and linearly. Teams can ebb and flow, sometimes regressing, and sometimes it's hard to identify the specific issue. Normally there’s something fundamental going on (overwork, sickly bee, poor management) if you look closely.

1. Forming

This one isn’t rocket science. When you bring a new team together, it might be an all-new team for a start-up or a mix and match of old and new artists. All these talents and personalities take time to settle in. It’s a stage of discovery during which both you, the Lead Artist, and Art Director will be under assessment in the team’s collective mind. They’ll be looking to you for leadership, as the project is in its infancy and full of uncertainties.

2. Storming

In the storming stage, the team has moved past the awkward forming stage, they’re familiar with each other and who are the strongest and weakest members of the team. Like a family, the team becomes emboldened, comfortable showing more of their true nature, opposing views, pushing boundaries. Clear leadership needs to provide direction, listening to all views, but not bowing to the loudest or most troublesome.

This sounds like a classic pre-production stage to me. I’ve experienced both sides of this coin, and when not managed properly, the team tears itself apart and collapses. When managed with clear and direct leadership/decision making, the team comes out stronger and more united.

3. Norming

Moving from competing against each other, the team works as one unit. Leadership roles are accepted, artists understand where they can pull and push and what’s acceptable. Processes are becoming stabler and more established, including pipelines and lines of communication. Artists bond and mutual respect builds, enabling a safer environment for asking for help, for passing on knowledge to lift the entire team rather than the individual.

4. Performing

Full steam ahead, all systems are go. Your art team is absolutely nailing it, pushing boundaries of art, building assets, hitting deadlines; they can see, touch and feel the game’s vision. Artists are happy taking on further responsibility and are more agile, able to jump between tasks. Your role is clear, the team understands what you do day to day, and what is needed in terms of quality and pace.

This is a great stage to be in. The team sustains its own momentum from their successes, because seeing all the artwork being built and implemented is fuel for the mind. When Epic formed Scion Studios for Unreal Championship 2, I remember this stage clearly. We were on fire, which is probably how we got a ground-up game built in two years with a team of 20 staff.

5. Adjourning

The game ships, and there’s no artwork to be built until the next project starts up. It’s a time of reflection. If there was a hard push at the end (bad crunch), there will undoubtedly be some losses because of burn-out. Ideally the team will transition onto another project together, maintaining the momentum and collective knowledge from the past game.

This is like the life cycle of an artist, isn’t it? The benefit of this approach is it helps to understand and evaluate team development. The team is constantly evolving, both the people and the project alike.

For me, the one thing that stands out is clear and consistent leadership. Assuming you and your Art Director share similar values, you can provide the foundation for the team to grow in the right direction. The artwork is normally the easy side of the project, it’s the team dynamics that have to be cultivated. By dealing with issues early on, having constructive debate, where opposing ideas lead to new ideas and coloration, you’ll be well on your way to a healthy team.

But your team doesn’t need to be continuously monitored. Once they’re working well, they’re self-running to a large degree. That’s not to say you should be hands off and let it go wild, even the best-oiled machine needs some tweaking. For artists, inspiration and motivation are their fuel, so what can you do to keep them topped up?

Inspiring teams can be hard, especially if they are a grizzled bunch of veterans, but regardless of your team’s experience, you can still inspire them! But what can you do to get the team going and power them on?

A motivated team will move mountains. They might groan a little, but once moving, the impossible becomes the possible. I’ve seen it time and time again, where the project makes a big shift and the teams have to accommodate it and you know what, it all works out, everyone is motivated to keep the project rolling and to make a better product.

Before we look at motivation, let’s clarify something fundamental.

What is inspiration? Inspiration is being mentally stimulated to do or feel something, often something creative. It’s the spark that goes off in your head, you know, that moment where you think, ‘Oh, I’m going to have a go at that!’

Motivation is not inspiration. Inspiration is the ‘aha’ moment, while motivation is the will to complete a task. You can be motivated to solve a tricky issue, but you’ll need a moment of inspiration to provide the creative solution everyone is looking for.

Team motivation

• Concept artwork – For any artist, seeing some amazing concept art for the project really gets the blood pumping. Concept art sells a vision of the game that everyone can buy into, assets that they can imagine building, getting kudos and satisfaction from translating the ideas into a fully realised version. Often, artists will fight (not literally) to build the latest and coolest design.

• New software – There’s nothing like a new tool, plugin, or programme to get artists inspired to try new techniques. Once one person has success, it’s like wildfire and everyone wants a go.

• New hardware – There’s a new ultra-wide screen, sure let’s try it; new digital tablet, yeah, I’ll give that a go; better noise-cancelling headphones, count me in! Who doesn’t want the latest goodies and, for artists, a rig that improves speed and workflow is always appreciated.

• Tutorials – The only problem is choice, but that’s not really a problem, is it? If your company has the budget, see what you can get assigned to you and your team, because more knowledge can only benefit the project in the long run.

• TV/cinema/streaming/on-line shows – A lot of studios allow streaming of shows while working (though normally in a small window). It helps pass the time on the long and boring parts of the pipeline and can aid focus for others. Movies and ‘making of’ segments are always a favourite too.

• Other artists –Examining other artists’ work, whether digital or traditional media, all feeds into the mental bonus pot, the one you draw upon when creating your own creations and designs. For a team, it’s good to have knowledge-sharing sessions, where artists share techniques on design theory, artwork, and software.

• Interests – Can your company provide life drawing classes or painting? It’s always good to move away from the digital space, to make the brain work in other ways to aid flexibility of thought.

• Trips out – Reference gathering, go-karting, architecture, the beach, the bar, or whatever works for your type of team and project, you might even want to visit a museum or art gallery!

Fail freely

Your team needs to know it’s ok to fail, which can be hard in a pressured environment, but if you can, give them some time to experiment and innovate. You never know what they’ll come up with. Some of it could be junk, or so crazy that it inspires further discussion, thought, and more experimentation.

TIP: As a leader, you can lean on your team to provide solutions. It’s not all down to you, so give them the tools and the training, and let them come up with ideas to solve project challenges. People are more motivated if they can contribute more, and feeling valued is important. It’s known as delegation.

If you aren’t delegating, you’re doing your job wrong.

One of the biggest myths of being a Lead Artist is that you must be the best artist. Absolutely, you need to be good at your job and, at the time of moving into the role, you might have the best skills in one area over the rest of the team. There’s no question that this helps with team cohesion and respect. But because most people don’t know what’s involved in being a Lead, they have misconceptions about the role.

I mentioned previously that your focus must change from you to them, because you are there to manage the team, to maximise their strengths and remedy their weaknesses. Your role is master juggler, working out how to keep the project flowing while switching from one thing to another.

Not delegating is an easy trap to fall into, and often relates to control. You think you’d have less influence, or no ownership. At a fundamental ego level, you can’t say ‘This bit is mine’, so you hang onto things, or your perfectionism gets in the way and, in the worst case, you become the pinch point. Imagine a wide river full of game assets floating down to a lock (that’s you) but the gate only opens when each piece has been checked. However, the river at the gate is narrow and shallow, and checking is slow. You can imagine the chaos that reigns. Assets would back up, projects slow, bosses get unhappy, and the next thing you know, you’re called into the office for ‘the chat’.

For those to yet experience team leadership, let’s look at few things to help you along the way, break down a few myths and give you something to hang your thoughts on.

Isn’t delegation the same as dumping?

Dumping is the definition of poor management. It really should be avoided. As an employee, being dumped on feels like it sounds and only creates negative feelings and bad will.

• Unreasonable deadlines

• Little to no detail of requirements

• Minimal to no support

• No reviews until the end

So, what is delegation?

You are passing on work to others, but it’s how it’s done that’s different. It’s using the right person for the job and providing support.

• Manageable deadline

• Clear expectations of delivery and scope of work

• Supportive throughout the task

• Regular review gates

Is there a delegation process?

Yes, I think Figure 18 describes it well. Find the right artist with the right ability, brief them so they know what to do, ask if anything might block them and off they go! Then follow up with a review and provide feedback. In the workplace this is normal, and often work is reviewed as a group (art team meeting) or at the desk for one-on-one feedback.

Figure 18: The delegation process (adapted from source: https://www.pocketbook.co.uk/blog/tag/delegate/)

I can feel you nodding off here. If you’re wondering what the point of all this is, it’s this: If you take nothing else away with you in this section, consider these points:

Delegation:

• Frees up time for you to concentrate on other important things

• Maximises artist engagement and pro-activity

• Boosts creativity and efficiency

• Shares accountability for the project where everyone handles something

• Shows cooperation and team building

There’s an old saying ‘If you want anything done, ask a busy person to do it’. Delegate your work to team members who are already in the flow of pumping out artwork, already getting things done. They are capable and approach challenges with a positive attitude. There’s one caveat though, don’t overload your busy artists, otherwise, they’ll burn out. It’s a delicate balance!

This brings me neatly to the feedback process, how to offer critique and keep your team on track.

One size does not fit all, and feedback is best when you tailor it for your artists. It’s all too easy, especially if you have a large team, to approach them all in the same fashion. But have you noticed, some you get on famously with, while some hate you with a passion? Why is your management style working for some and not others?

Every member of your team is different, they all have different backgrounds, home lives, personal issues, health problems, confidence levels, experience and values. At any point any of these can change which will affect their work/behaviour.

Going back to the Tilt 365 system or Myers Briggs, can you recognise where your team members might fit? Understanding what motivates your team will help you get favourable responses from them. Depending on your artists’ own journeys, they’ll be at different points, so different levels of response and style are needed.

What stage is your artist at?

• Approval – Early-career artists are often looking for approval and support. Feedback can feel personal and they can react defensively. Some may have trouble sharing work and ideas for fear of making mistakes or receiving critique.

• Apprentice – Having overcome defensiveness and vulnerability, they are open to feedback, and are keen to improve their industry skills wherever they can. Eager to share and continue to build confidence.

• Autonomy – The artist has hit their stride; they are confident in their choices, regardless of whether others think they are right or wrong. Changes are accepted as part of the approval process, and they no longer take feedback personally.

Depending on your artists’ own personal and creative journeys, you’ll find that each one has a different story to tell. To get the best from your team, understanding them and how they operate certainly will help. But it’s not a one-way street, and most of the time it’s fairly obvious what stage an artist is at after your first few interactions. You’ll see right away how they respond to your feedback.

Some of your team will be Juniors and respond well to gentle coaching, while others will be more attracted to direct talk about technical tasks. In which case, they’ll prefer more specific instructions without vagueness.

I had a habit of saying ‘Maybe you could do this, or maybe try this’. While I felt I was clear about what I was asking for, some artists saw it as an option and it’d create confusion for them. It would create disappointment for me as I thought I’d given simple, clear direction when in fact I hadn’t. I didn’t want to give a direct command; what if it was wrong, what if it turned out bad, what if I’d wasted their time, how foolish would I feel? I’m sure you are familiar with these kinds of thoughts. Over time, my confidence has grown, and this is no longer an issue.

Common pitfalls of the beginner manager

I know quite a few of these because I’ve made them and fell into these pits. I can only apologise profusely to any of my past teams for having to endure this. But, like I say, you don’t know what you don’t know, sometimes you can’t help making mistakes.

Next we’ll look at some common sticky situations. These can increase your workload and restrict your ability to give clear feedback, reducing the effectiveness of what you’re trying to convey to your artists.

• Shit sandwich – A classic early manager mistake. This is an overly used and abused technique. You start and end your conversation with something positive, but in the middle you sandwich the negative points. There’s a hope your artist won’t feel bad but that’s all they’ll remember after you walk away. The technique is used often because there’s a vacuum of good alternative information or training.

• Starting with the good makes sense, to appreciate and vocalise what you like and what’s been done well. Then move onto areas for improvement and why, focusing on what they can do to achieve the ‘correct’ asset. Provide support, not derision. You don’t need to end with a false feelgood quip, as that undoes any previous good work.

• Getting your own way – A new manager can fall into the trap of wanting to get their own way at any cost, because by not doing so, they think they’re a weak leader. The downside is that other team members’ feelings and ideas are pushed to the side, causing a lack of engagement as individuals realise they’re not being listened to.

• The strength of a leader is to recognise the best method, solution or idea, even when it’s not their own, and take that one forward. It’s much better to make use of multiple brains than just one. Even though artist X has the better idea, it’s still your choice to make use of it. Once you start feeling powered up by your wins in decision making, you’ll gain confidence in your leadership skills and you won’t feel you’re lacking control.

• Perfectionism – Our jobs as artists encourage perfectionism. We can undo any single action we make, make revisions, tweaks, improvements and alterations, but artwork remains subjective so there is no perfect. Chasing your vision of perfect is really costly, in time, energy and company money.

• I’m all for making great-looking art but you have to realise that the end user, the player, won’t notice the final 10% (some may disagree here). It’s a balance but deadlines have a way of reducing perfectionism.

• Holding on too tight – You want to keep control of everything as much as possible, afraid that if you reduce control, quality will slip. This causes you to become a bottleneck and assign yourself too much work, causing overload and team resentment.

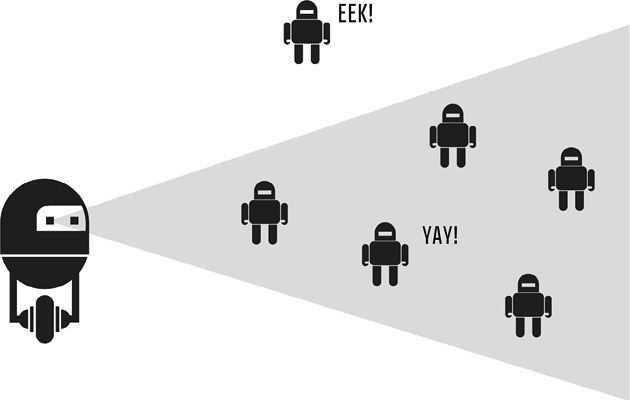

• Keep artists in your ‘cone of vision’. I’ve used this method and passed it onto others. Your cone of vision defines the boundaries of what you are prepared to accept in terms of quality, style, technical set-up or whatever’s important to you (it’s important that you are clear before you can operate this technique).

• This worked well for me as a way of loosening control over a team, reducing the urge to check everything, to constantly feel you should be on top of everything. With a big team, that’s not possible.

• It’s about putting the responsibility on the artist. If they move too far away from the target artwork then they’ll have to rework it to bring it closer. It doesn’t have to be spot on, not everyone can hit the bull’s eye, but as long as it’s close and doesn’t move the artwork too far away from the general direction the game is going, then great, move on!

• I realise this makes no sense without a diagram…

Figure 19. The cone of vision

• Avoiding problems – Even experienced managers can feel intimidated by the more difficult problems, things that involve unfamiliar soft skills, tackling under-performing artists, or team morale issues, and so they avoid doing anything hoping that somehow it will go away or resolve itself.

• If it helps at all, these problems never resolve themselves. Left alone, they just get worse. They are only solved by you helping them along. Work with your Art Director (AD) and HR if need be, tackle them head on (but don’t butt heads) to redirect and resolve the best you can. Sometimes you’ll have employees who like to test boundaries so it’s down to you and the AD to gently reinforce them.

• Taking on other people’s problems – Another classic trap is where someone is all too happy to highlight an issue and then pass it on to someone else. As a manager, it’s easy to try to be the hero and take on the issue so you can deliver thoughtful feedback, but what happens when there are too many to handle?

• To answer this classic problem, there is a classic book in The one-minute manager meets the monkey by Ken Blanchard. Basically, the monkey represents a problem, and when you take on someone else’s problem, you carry the monkey on your back. Too many monkeys, too much stress, and too much doing other people’s work.

• Once you recognise the people who pass on monkeys (can be anyone within the company hierarchy), then you can redirect or not even take the monkey on. This is one skill to learn if you’re overly a ‘yes’ person. Be discerning about where you spend your time because it’s precious.

Giving feedback is an art in itself; if it comes naturally to you and people accept it, then great job, you’re a step ahead already. For some, though, it’ll take more effort to craft this skill. Over time, you’ll need to decide what works not just for your team but also for you to feel confident and secure. You’ll make thousands of decisions over the course of the project and some will go better than others, but with every step of the way, you’ll be improving. That’s all part of the game dev process.

Having a mixed team of skills, abilities, and experience levels, you’ll find the tempo will fluctuate over the course of the project. There’ll be periods where everything is super smooth, and assets and levels all come together to make the magic. And there’ll be times where some things start to wobble, wheels (artists) squeak, fall off or come to a halt, and as a leader, it’s up to you to figure out how to free them up and help them run smoothly again.

You’ll make judgement calls on the relative severity of a problem, considering how often it recurs, how it affects the team, and whether you even need to solve it yourself. Maybe a Senior should educate the others in the team, or even flag it and raise it with HR? You’ll be making these observations and adjusting all the time. I’ve found team members fall into three categories, which’ll help you in figuring out the right course of action and severity.

A traffic-light system works well, whereby you make calls based on the seriousness of the situation. While the problem severity will vary, one thing is certain, whatever the level, you need to deal with it!

• Green – Small tweaks, easy alteration, keep going (normal feedback)

• I call these course corrections. It’s the everyday stuff of being a Lead, evaluating work and making subtle corrections to hit the required quality bar for the company. You make hundreds in a week and keep the project progressing. The artists pick up on their mistakes and 99% of them avoid making them again.

• Amber – Needs observation, mistakes recur, or performance is declining (may need an intervention)

• This level is normally saved for the repeat offender, and it may stem from a behaviour problem, but is more likely a procedure and art issue that the artist just isn’t getting.

• To solve this, I work with the person myself or assign someone to do daily or thrice weekly check-ins at a consistent time. This takes place for about two to four weeks and enables the artist to realign, figure out what’s going wrong and understand what’s expected to deliver acceptable work. They can be five-minute chats at the desk, reviewing work, answering any issues, pointing out anything that could be a problem down the line.

• You’re helping them, not just leaving them be and hoping they’ll fix it, that’s the difference here.

• Red – Inappropriate or unprofessional behaviour, stop and implement solution (private one-on-one, HR, or both)

• If your artist in special measures can’t make the change, then it’s onto a performance plan as a last resort (see below). Of course, if your artist has showed highly unprofessional behaviour, then it’s time to speak to your artist in a private space like a side office to find out the facts and decide how to move forward. They must know that this won’t be tolerated and continuing almost certainly will affect their current job.

When you’ve noted who needs help and the level of severity, there are a few things to think about to keep yourself on steady ground. Sure, you’re their Lead, but you want to be well prepared, and for it not just to become a power struggle.

• Identify – Where does the person need help? This could include productivity, attitude, politics, time keeping, file management, or communication.

• Check yourself – Before you call the meeting, are you mentally in the right place? Are you bubbling over with frustration? If so, today is not the day to talk to your misplaced team member.

• Keep to the facts – Steer clear of generalities because it weakens your position when discussing the issue at hand. Avoid saying things like ‘You always do this’, which are vague and hard for the person to understand. Be specific, such as ‘When you did this, that happened, and the consequence of that was this’. I’m sure you get the drift. You can’t argue with the facts.

• Keep it informal – Until you don’t, that is. Depending where on the traffic-light system an issue falls, it’ll dictate how you handle the situation. If it’s a first-time problem, then go in gentle and easy, perhaps in an off-the-cuff meeting, like a quick five-minute chat in a meeting room to consider the issue you’d like fixed. Should the task be more serious, or the person is a repeat offender, schedule thirty minutes and arrange it in advance to give your team member time to prepare (mentally).

• Paper trail – Always follow up with an email after a chat about something serious. You’ll both have a record then. Also, they can suggest corrections should something not be reported correctly. I would also inform your HR Department.

• Performance plan – I saved this for last because it’s the last chance saloon. When one of your art team consistently isn’t hitting expectations (you may inherit them from a previous manager, so don’t beat yourself up) then it’s time to make a formal plan of action. It’s painful and slow. All their work is measured and logged, everything is tracked and reviewed. From a Lead Artist’s point of view, it’s a proper time sink. From your artist’s point of view, performance plans can go one of two ways; they improve and succeed, or they continue to stay down, and it’s only a quick step to being released from their job.

The PDR meeting – manager edition

In earlier chapters, we covered the Personal Development Review (PDR), which is commonly used as a yearly review of an artist’s progress and development. This time we are looking at it from your perspective, as Lead Artist and manager. I’ve yet to see any training on how to hold a review meeting of a member of your team, it’s all been learned on the job which seems weird, right?

Pre-preparation – This isn’t for the actual review; this is your ongoing note-taking as you go along. With so much information flowing about, it’s easy to forget the good and the not so good of your team. I recommend making a cheat sheet as you work through the year, divided into two columns, one noting areas of improvement and, just as importantly, areas where an artist really did well. Believe me, it’ll save you a lot of time with filling in review sheets.

Review systems – I have mixed feelings about review systems. Companies use different systems, different rating schemes, numbers, words, you name it; it seems to be out there. Some review schemes are top down, in which your boss reviews you, you review your team. There is also the 360-degree review whereby your boss reviews you, you review the team, the team reviews you, you review your boss.

Get feedback – Either way, you’ll want to get feedback on your team from others, whether they be other artists, designers, or producers, to obtain a rounded picture of how your team operates. With this information, you can complete your review of your team.

Follow up – If the review goes well for your artist, everyone walks away happy. Your artist may come out under a dark cloud, however. Follow up with the help they need; solutions will have been part of your discussion, be that mentoring, tutorials, or adjustments to attitude, but hold them accountable and keep checking in or assign a Senior Artist to help and provide feedback to you.

Quick tips

• Unsure of how to review? Ask for help, training, or have your Art Director there with you.

• Don’t leave reviews until the last minute, it’s not fair on either of you.

• Go in looking for positives, but don’t shy away from areas of improvement and development.

• Ask questions, let your artist do the talking, helping them along with open-ended questions if they are the quiet type.

• Be supportive, as all issues can be solved, but their monkey isn’t yours to hold, let them keep hold of it.

• Give them the opportunity to give feedback on you, ask them are they getting what they need, anything you can do more of or better? It’s a tough one initially to ask, but like your art, you’ll go from strength to strength as time passes.

Whether you have helped shape a team or inherited one, it hurts to lose artists from your group. It’s natural for people to come and go, and change is inevitable, because artists are hungry for more, for different projects, a higher salary, or an improved lifestyle. I did the same. But it’s still difficult when someone asks you, ‘Have you got five minutes?’ You know something is coming!

In an ideal world, you’d keep your team, it’d be one big happy family (sometimes it is) but in this competitive world, things aren’t that simple. Artists more than ever can join and leave for a variety of reasons, and they do, especially when unhappy. Let’s look over some of the common reasons for churn.

• Variety – Artists are always looking to grow, wanting new skills and exciting opportunities. Over time, projects can lose their shine and artists want to challenge themselves in new ways, they might want to change from say, prop artist to concept artist. Sometimes, it makes more sense to change company to create the chance.

• Boredom – Artists like to get titles under their belts, to work on engaging projects, and to show their work. If the project is floundering or career progression is limited, artists can get itchy feet and start to look elsewhere. If there’s another more successful project being made down the road or in the same town, you can bet your bottom dollar they’ll look to shift to the other side.

• Poor management – Your team may leave because of poor leadership; nothing loses staff at a greater rate than mismanagement of the team and project. As a middle manager, your reach within the company might be limited, but that doesn’t mean you can’t help in your own way. By identifying any areas that you can directly influence, it’s possible to help improve the overall system.

• Competition – Are your staff leaving to go to other companies? See if you can find out why. What’s making them decide to leave, is it the benefits? Salary? Company culture? The lure of prestige projects?

• Lower pay – This is easy to understand, more so in the UK. If one of your team is leaving and you really want them to stay, speak to your Art Director (AD), as companies can counter-offer and raise a salary to compete, hoping to make your artist change their mind. It’s not guaranteed though.

• Look closer to home – Is it you? Can you do anything more, or better? Find out from HR or your AD if there are areas you could tweak in case you are causing friction.

Your team demands your attention just as much as any artwork, so keeping them motivated is important to the project’s success. You can only do what is in your sphere of influence though, some issues are bigger and could be company culture–relate. The aim isn’t to burn yourself out trying to be ‘super Lead’, but to have a growing awareness of your team and how they best operate.

You might have at least once thought, ‘Where will I find the time?’ It’s challenging, especially if you’re committed to a healthy work-life balance. So, my last chapter for Lead Artists includes ways to help you regain that precious resource, time.