CHAPTER 1

The Story of Beef

It happens occasionally—to most of us. You’re walking down the street, having a conversation, minding your own business, whatever. Suddenly you stop and lift your head. Nose to the air, you take a couple of quick inhalations. You can’t help but twitch in the direction of an aroma so unmistakable and irresistible: a whiff of smoke, of gently burning oak, then that mixture of scents—savory, salty, smoky, and a bit sweet. It triggers something deep in your bones, flowing in your blood. Powerless to control your reaction, you stop in your tracks and spin your head, like a wolf on the prairie, to try and determine from which house that inimitable scent is coming. Someone is grilling steaks.

The fact that we completely freeze because of a primal, involuntary attraction to the smell of beef cooking over fire is understandable. People have been stopped dead in their tracks by the smell of beef for tens of thousands of years. Indeed, they’ve also likely been singing songs and telling stories about it. We know they painted pictures of beef. At least that’s what the cave paintings at Lascaux in southwestern France (ca. 17,000 BCE), tell us. As do the cave paintings at Chauvet-Pont-d’Arc in France (ca. 30,000 BCE) and El Castillo in Spain (ca. 39,000 BCE) and the engraving at Abri Blanchard (ca. 38,000 BCE), not far from Lascaux. These are not line drawings of New York strips or ribeyes, of course, but images of wild cattle.

Cattle—wild and domestic—have been an essential part of human culture for thousands, probably hundreds of thousands and even a million, years. These animals have provided milk, meat, leather, labor, strength, transport. They’ve exponentially expanded—for better and worse—the capacity of what humans have been able to accomplish. We must marvel at them but also recognize that our love of and instinctive response to the smell of cooking beef is not some sort of quirk. It’s hardly even a choice for most people. It’s hardwired—something we’re not powerless to refuse but certainly programmed to savor.

The enjoyment of steak, therefore, goes back a long way, intertwined inseparably into the early moments of human evolution. In a way, you could say steak (and beef in general) is part of what makes people people.

Early Steak

It’s not necessary to know about the history of cattle when driving to the grocery store to pick up a couple of steaks to grill out back on a Saturday night. Yet it is interesting and somewhat profound to consider the earliest origins of beef. To know that, while on this errand, you are walking stride for stride with Grog and Thak as they stalked a wandering bull is a powerful notion (or at least an amusing one). Along with salt and pepper, sprinkle your steaks with meaning in a vast natural and historical context; it’s good seasoning. Consider, friends, the aurochs.

Our ancient ancestors did more than merely consider the primogenitors of all modern cattle. They revered them. We know this because in those ancient cave paintings we see beautiful, skilled, sometimes full-size line drawings of these animals, which were about a third larger than modern cattle. One painting depicts a beast seventeen feet long, standing six feet tall at the shoulders, with fearsome curved horns. Aurochs were creatures to be reckoned with.

Tens of thousands of years later than the cave art, Julius Caesar, writing in his Commentaries on the Gallic War (when he headed into the wild lands north of Rome to make his fortune expanding the empire up into modern France, Germany, and Britain by conquering and pillaging the native tribes), would describe much of the exotic fauna he encountered. This included the wild aurochs—cattle had long been domesticated—which he described as “a little below the elephant in size, and of the appearance, color, and shape of a bull. Their strength and speed are extraordinary; they spare neither man nor wild beast that they have espied.” He noted that the local tribes “take with much pains in pits and kill them.…But not even when taken very young can they be rendered familiar to men and tamed. The size, shape, and appearance of their horns differ much from the horns of our oxen. These they anxiously seek after, and bind at the tips with silver, and use as cups at their most sumptuous entertainments.”

Julius Caesar’s description is considered pretty accurate, especially if you consider he was likely comparing the aurochs’s size to the relatively diminutive North African elephant (now extinct). The horns of an aurochs could reach three feet in length. You can imagine the difficulty Paleolithic humans would have had in bringing down one of these massive, dangerous animals, which likely weighed around two thousand pounds (compared to the one thousand pounds of beef cattle today). But you can also imagine how much those early people on their actual paleo diets must have savored the flavor of the steak dinners that came after.

Known as Bos primigenius, the aurochs evolved earlier than Homo sapiens did, with a history going back about 2 million years in India. Leading up to this in the Pliocene epoch (5.3 to 2.6 million years ago), global cooling (how refreshing) and drying from the warmer, wetter Miocene caused a retreat of forests and jungles and a vast expansion of grasslands and savannas. The shift in vegetation sparked the evolution of grazing animals, which came to the fore in this period. Following the Pliocene, the Pleistocene (at the tail end of which modern humans evolved) saw aurochs spread throughout much of the world, reaching Asia, the Middle East, and Africa. Popularly known as the Ice Age, the Pleistocene arrived in what is now Europe sometime around 270,000 years ago, not (relatively) long before the appearance of modern Homo sapiens, which occurred about 200,000 years ago. Homo erectus, however, dates to at least 1.8 million years ago, and scientists have theorized that hunting and meat eating go back at least that far. That means human ancestors may have been eating steak for well over a million years, probably closer to two. Indeed, scientists now estimate that the earliest evidence of human ancestors cooking occurred around 1.9 million years ago, so perhaps steaks were some of the first things ever cooked. Perhaps cooking was invented for steaks!

Hunting giant, angry aurochs would have been unpleasant. It is much easier to select from a bunch of smaller, dumber, and tamer versions of the animals. Enter the domestication of cattle, which dates to as recently as 8500 BCE. Study of DNA suggests that all cattle today are descended from only about eighty animals, perhaps one small herd. No one knows exactly how an animal as fierce and enormous as the aurochs was domesticated, but the easiest scenario to imagine is that some babies were captured and raised away from the parents.

Domestication brings many changes. Both physical size and brain size diminish. With their movement, feeding, and reproduction now controlled by humans, animals become more docile and, well, not smart. They also generally change in physical appearance, developing colorations and marks that distinguish them from their wild relatives (think of the black and white blotches of Holstein cows—that did not occur in nature). Domesticated species lose some of their original strength, health, hardiness, and ability to cope with adversity.

All of this sounds sort of insidious when described so clinically. But it is true that the domestication of cattle has changed us even as it has changed them. For instance, at one time, humans became lactose intolerant at the onset of adulthood. But over the millennia, this changed, as being able to digest milk protein and fat conferred some sort of evolutionary advantage on the people who could do that. Of course, domesticated cattle sped change in human culture in obvious ways, as well. The availability of strong oxen to help with work in the fields allowed the expansion of farming. Leather from cowhides became a hugely important substance with all sorts of applications, from shoes and clothes to shelter. Having a convenient source of nutrient-dense food available in the form of beef furthered almost all human endeavors. Cattle were the powerful engines of progress.

AUROCHS REVIVAL

History’s first recorded extinction was sadly the aurochs, in 1627, when the last one, a female, was killed in a forest in Poland by a nobleman. (They had survived that long because only the nobility were allowed to hunt in Poland at the time.) But on several occasions in the last hundred years, a surprising project has arisen: to revive the aurochs. We’re not talking DNA suspended in a prehistoric drop of amber here (the DNA of the aurochs has already been sequenced), but resurrecting the animals themselves using the process of back breeding. This requires finding surviving cattle that retain some of the characteristics of the aurochs—size, shape and breadth of horns, color and markings, and the like—and breeding them together in a way to cause these genes to recombine and remain expressive. Scientists have even used cave paintings as one of their anatomical guides in this endeavor. The first attempt was made by two German zookeeper brothers in the 1920s. For them, success in restoring the aurochs would have been a potent example of a past of racial purity—of the power of Aryan eugenics. Fortunately, the cattle they produced bore some aurochs-like characteristics but were never taken too seriously.

In the last twenty years, however, new efforts have begun again with the far more noble purposes of “Rewilding Europe,” as one of the several nongovernmental organizations working toward the goal is called. The reasons for restoring the aurochs are ecological. By some estimates, European farmers are abandoning their small farms at the rate of thousands of acres of agricultural land lost every year. Without the activity of large herbivores, unused land either reverts to forest or becomes barren because the soils have been ravaged by modern agriculture. The action of ruminants restores and protects grasslands, which become diverse natural habitats for numerous native animal and insect populations. Wolves have destroyed other herds of herbivores, but the aurochs-like cattle have been strong enough to suffer few losses.

As the project of domestication itself evolved through controlled reproduction—a sort of fast-tracked evolution—people began shaping cattle to suit their specific needs. These take many familiar forms, such as physical strength, dairy, meat, or even an ornery temperament (which is bred into Spanish bullfighting bulls). Cattle have also been bred to exist in environments with different terrains, climates, and food sources. Over the centuries, this constant and selective breeding has given rise to a tremendous expanse of genetic diversity. These are the distinct breeds of cattle, which number somewhere around eight hundred.

However, in recent decades, globalization and technology have compelled people to focus on only certain breeds deemed more desirable than others, resulting in a winnowing that many expert observers consider dangerous. Hundreds of recognized cattle breeds, representing a valuable genetic resource of various types bred for specific environments, are threatened with extinction. As Valerie Porter points out in her book, Cattle: A Handbook to the Breeds of the World, “It is much easier to destroy such resources than to create them.” The ability to produce great steaks is certainly considered a valuable genetic resource. After all, these cattle breeds have proliferated more than any other—all thanks to their superior ability to deliver that irresistible taste of beef.

The Taste of Beef

The flavor of beef is sui generis, prompting even the modestly curious to ask, what makes beef taste so beefy? When Jordan posed that question to Jerrad Legako, an assistant professor specializing in beef in the Department of Animal and Food Sciences at Texas Tech, the answer was surprising. “We don’t have the full picture yet,” says Legako.

We do know that even though raw meat is bland, it contains a vast pool of precursor compounds such as amino acids, reducing sugars, and fats. Cooking converts these into the aroma and flavor of beef, thanks to processes such as the Maillard reaction and lipid oxidation and the cascading series of interactions between them.

Legako notes that what we perceive on the tongue when eating cooked beef is related to umami—amino acids and small peptides. “And then in the aroma fraction, you find more of the sulfur-containing compounds,” he says. “Lipids [fats] also play a big role, but they’re tricky because a little lipid oxidation is attractive, but too much lipid breakdown becomes rancid tasting.”

Most of beef’s flavor emerges during cooking, when heat allows the amino acids to break down over time, layering their flavors. Sulfurous compounds come from the lean muscle. At low levels, they’re meaty, he notes, but at higher levels they can be revolting, like rotten eggs. Fat, too, plays a huge role. While the fat in marbling doesn’t have a lot of flavor itself (for more on this, see this page), Legako says, “it acts as a reservoir for the flavor compounds during cooking and delivers them across the mouth. We refer to some of these flavor compounds as lipophilic, meaning they have an affinity to fats and will more or less absorb into the fat and become available for taste.”

If beef flavor can’t be reduced to a single or even discrete set of compounds, where does it come from? What are the important influences on beef flavor? Basically the question is this: how do we find the tastiest steaks?

One beef expert we talked to said that the conventional wisdom in the beef industry is that three all-important elements contribute to the taste and culinary experience of beef: genetics, environment (feeding and lifestyle), and age. With a reasonable understanding of these, you can obtain an inkling of how a particular steak will taste.

Genetics

It didn’t take long for the domesticated aurochs, accompanying migrating peoples, to start making its way from the site of its domestication in the Fertile Crescent to parts throughout the Old World. As the aurochs found its way into climates ranging from subtropical to subarctic, from desert to forest, from plains to mountains, it changed. In each place, people developed their own types of cattle, bred for environmental suitability. As those traits stabilized, breeding became even more specific.

The first types of cattle were bred for strength, to pull plows or timber or rocks. Later, cattle evolved traits beneficial for meat or milk production, but modern meat and dairy cattle are fairly recent developments, coming after horses and then tractors took over the heavy lifting of labor. Improvements in farming allowed the production of silage (wet hay or other feed compacted and stored anaerobically, whether in a silo or just a massive pile) for fattening cattle over winter. In time, cattle became a bankable food source, and the density of the calories and nutrition in meat drove the expansion of cities and other centers not based around farming.

When you visit meat producers today, you still hear a lot about genetics, as they are constantly looking to refine the gene pools of their herds, favoring some traits while discouraging others. Most of the traits they track meticulously are much more important to them than to the end consumer. These can be measurable, like yearling weight (how much the animal can be made to weigh after one year), calmness, or how easily and safely they give birth. Some traits, however, such as ribeye area, may very well matter to the end consumer.

These qualities beg the question, do different breeds produce different flavors? Are they like wine grapes, where Cabernet Sauvignon offers a completely different taste than Pinot Noir? Some steak houses and butcheries in Europe suggest the answer is yes, offering for sale, similar to a wine list, a variety of steaks with breed and place of origin listed on the menu.

In general, however, beef experts say no: beef flavor is largely beef flavor regardless of breed. What the animal ate and where it was raised are of much greater importance in determining flavor. Furthermore, almost all of the cattle we see—and eat—today are mixed breed. Just as mixed breed (mutt) dogs tend to be healthier and more resilient than purebred ones, so with cattle. DNA samples of most cattle will reveal a heritage of a number of different kinds of animals (even if some brands advertise a piece of steak as 100 percent one breed).

Nevertheless, breeds do remain important, as the breed itself may be inseparably intertwined with where the cattle are raised. For instance, in the southern United States, you find many cattle with strains of Brahman in them, which is a breed based on Bos indicus, the subspecies of cattle from India. Notable for the signature hump on its back, the Brahman was developed for its ability to tolerate heat and resistance to insects (and are not considered great eating).

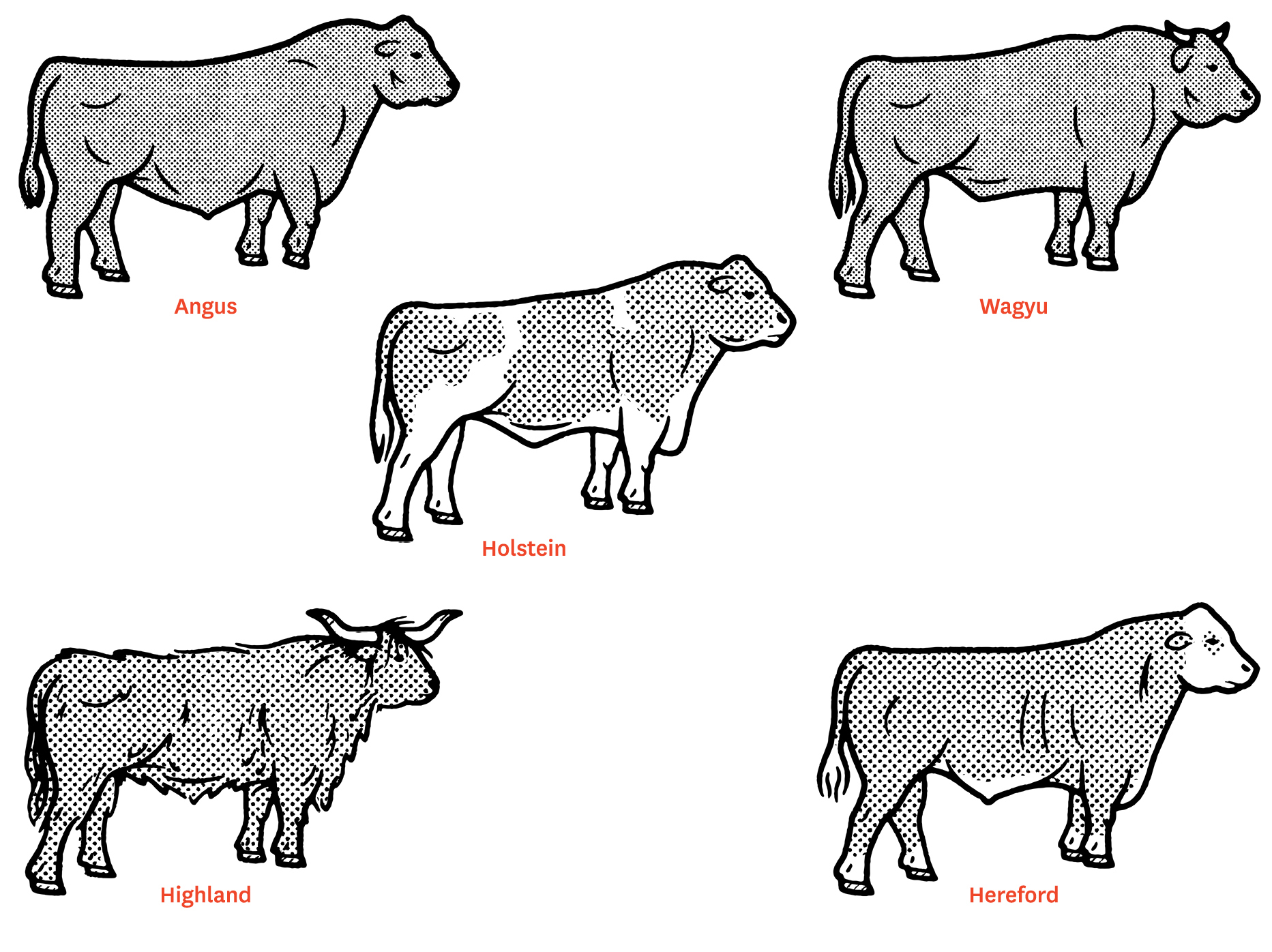

Even if the specific breed of cattle is generally not crucial to the meat quality, there are exceptions, and we’re going to be hearing more about breed in regard to steak in the United States in coming years. So here’s a brief rundown of the major cattle breeds you’ll find here and in other countries as they pertain to producing steaks.

ANGUS

The most prolific beef producer in the United States, Angus is described in Cattle: A Handbook to the Breeds of the World as “the mild-eyed breed which produces possibly the best beef in the world—lightly marbled, succulent, and tender…it remains a most economical breed to rear, able to thrive on rough grazing and to fatten on low cost rations.” You can understand the popularity: it’s a win-win for consumers and ranchers. A Scottish breed with roots going back to the mid-eighteenth century, the Aberdeen Angus was officially described in 1862. The first bulls came to the United States in 1873.

Despite the popularity and use of the name, what we eat today is not purebred Angus, as from the beginning and over the following generations, the breed has been intermixed countless times. To be certified Angus, either one parent or both grandparents have to have been Angus (but that doesn’t mean purebred Aberdeen Angus). For instance, for a cow to be eligible for the Certified Angus Beef brand, the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) definition states only that the live animal has to be “predominantly solid black.” A litany of further carcass specifications define the quality necessary to make the grade—“modest or higher marbling, 10- to 16-inch ribeye area, no neck hump exceeding 2 inches (reduces Bos indicus influence).”

So really what’s talked about with regard to Angus beef is Angus-type cattle. These are mostly black, stocky animals, though some white areas may be present. Red Angus can also be included, and the consensus is that the red color doesn’t make a difference. Indeed, most high-quality brands, such as Creekstone Farms or 44 Farms, trumpet not just the fact that they sell Angus beef but also the quality of their own proprietary genetics.

WAGYU

The famous Wagyu from Japan seems destined to be the newest It breed, the Next Big Thing. Why? Because of its ability to marble. Wagyu can be a source of outstanding, high-end steaks. Travel around the United States and you’ll find new Wagyu-focused cattle herds popping up all over.

In Japan, these are the cattle that produce those incredible, bizarre-looking steaks—steaks so marbled that they appear more white than pink. This kind of meat is a delicacy, is very expensive, and comes from purebred animals that are confined for their entire lives and fed only grain. Contrary to popular myth, they are not fed beer or massaged. We see very little of this high-level Japanese Wagyu beef in the States, as only tiny amounts are imported. American Wagyu cattle are neither bred nor raised to produce such extreme meat.

Wagyu, which simply means Japanese (Wa) beef (gyu), has a long and somewhat convoluted history. Some DNA evidence suggests genetic separation of the strain as far back as thirty-five thousand years ago. The animals were originally bred as pack animals, which is an important detail. Marbling—the ability to grow that intramuscular fat—is a trait that provides slow-twitch energy to the animal. Over the centuries, the Japanese emphasis on strength and endurance has led to beef of hedonistic juiciness. Wagyu cattle got an infusion of European genetics (Brown Swiss, Devon, Shorthorn, Simmental, Ayrshire) in the 1800s due to some imported cattle, but that was shut down again in 1910. Four distinct types of Wagyu exist in Japan: black, red (also known as brown), polled (hornless), and shorthorn. The latter two are found only in Japan. The first two, black and red, have been exported to other countries in extremely limited amounts.

The Japanese subtypes of Wagyu are distinct, as the rugged, mountainous nature of a country composed of islands has kept herds isolated from one another in separate pockets. While beef from Kobe is the most famous, the northern island of Hokkaido is also known for superior quality. And recent national competitions have been won by the Miyazaki region in the south, which today is regarded by many as home to Japan’s best beef. Breeding is strictly regulated and registered, with every animal having papers and a lineage that can be traced over many generations.

Only a handful of Wagyu cattle have ever been imported to the United States, first in 1976 (two black and two red bulls) and not again until 1993 (two male and three female black) and 1994 (thirty-five animals, mixed black and red). Since then, Japan, zealously guarding the preciousness of its genetic resource, has not allowed any more out of the country. Significant numbers of Wagyu also exist in Australia, New Zealand, and Canada.

In the United States, Wagyu beef looks different for a number of reasons. One, the meat here predominantly comes from crossed animals—Wagyu that has been mixed with any number of other breeds, but mostly Angus type. These cattle simply don’t have the genes to marble like the full-bred Japanese Wagyu, even if they are raised as the Japanese do. All consumers should be aware that when they buy a Wagyu steak in the United States, it has very little to do with Japan—just some traces in the cow’s genetics.

Furthermore, the Japanese eat their beef only in tiny amounts, rarely if ever indulging in the comparatively enormous steaks we Americans like to eat. An American-style ribeye steak of A-5 marbling (the top-level grade in Japan) would be simply too rich to consume entirely.

Nevertheless, even mixed American Wagyu is usually good meat. The most prominent brands are Snake River Farms from Idaho, which produces from black Wagyu crosses, and HeartBrand Beef from Texas, which specializes in Akaushi crosses, a red Wagyu. Japanese beef experts agree that black Wagyu types marble better than red, but the Akaushi still produces great steaks. Other outfits are also producing serious stuff. For instance, Fresh From OK, a local brand in Oklahoma, provides incredible pasture-raised Wagyu. First Light, based in New Zealand, is a farm cooperative with likewise superior meat, entirely grass fed on New Zealand’s famously lush pasture. At the moment, First Light is imported only to the western United States.

The other notable trait of Wagyu is the high percentage of oleic acid in its fat, the kind of “healthy” fatty acid found in olive oil. Wagyu is also touted for having higher percentages of omega-3 fatty acids than standard breeds do. This is true, says Steve Smith, a professor at Texas A&M who specializes in beef fat. But while the concentration of omega-3 acids in Wagyu is higher than in conventional beef, it is still far lower than in fatty fish from cold waters. And despite the hype, omega-3 fatty acids have yet to be scientifically proven to be more important than other nutrients.

HOLSTEIN

Another “new” trend is meat from Holstein cattle, a breed primarily known as a dairy cow. It’s not common knowledge, says Legako of Texas Tech, “but about 20 percent of our beef supply is Holstein. We’ve reduced our beef herd in the US significantly in the last few years due to drought and other factors, and that’s allowed the dairy industry to sell Holstein steers at a profit.” Typically, Holstein steers wouldn’t have had much value, as the females are the dairy engines. But Holsteins are predisposed to marble, he says, and have “a different muscle structure and fiber than traditional beef breeds, making them a positive in palatability.” (This is how meat scientists talk about steak.)

There are some important fans of Holstein out there, notably Bryan and Katie Flannery of Flannery Beef (see this page), who are aging and selling Prime-graded Holstein.

HIGHLAND

A great Scottish breed, Highland cattle are the shaggy, horned cattle you might occasionally see, especially in northern climates. Famous for being aloof and hardy, these cattle are from the rugged highlands of Scotland, where they could be left to wander and graze and largely take care of themselves. One of the oldest, purest breeds in Britain, Highlands can survive on sparse grazing and be productive in places other cattle could never endure.

“Temperament’s a key thing for Highlands,” says John McLaughlin, who raises excellent grass-fed Highland cattle at his family’s eponymous farm in Michigan. “When they originated, the cattle were raised in close proximity to the children of their owners. You couldn’t have an animal with these big horns killing your kids! So they were selected for temperament.”

The other thing McLaughlin notes about Highlands is that they’re slower-maturing animals. “It’s more costly to raise them than other breeds, especially on grass,” he says. “The typical Highland on a more grain-based diet will take at least twenty-four months, whereas the beef you’re getting in the grocery store is probably thirteen or fourteen months old.” But because of the age, the Highlands can have a lot of flavor, particularly those aged on grass, like McLaughlin’s herd.

HEREFORD

The origin of this British breed can be traced back to draught animals used in Roman times. Over the millennia, the breed—notable for its red or orange coat and white head and belly—was converted into efficient beef cattle. Popular meat animals for centuries, Herefords today are prized for being muscular and quite enormous—males can get up to eighteen hundred pounds—and for their propensity to fill out admirably in the more valuable cut areas. Furthermore, they’re considered vigorous and with good foraging ability, and they gain weight quickly.

Environment

As already noted, what a cow eats and how it was raised are considered far more important to its flavor than breed. “Temperament is tenderness,” John McLaughlin is fond of saying. He’s looking for and breeds well-tempered cattle, but their temperament also depends on how they’re treated. Indeed, gentle and compassionate treatment of animals is vitally important across the board, but in the case of beef, it also has a crucial role to play in the meat’s flavor and tenderness. An animal that is stressed or fearful releases hormones into its system that affect the flavor of its meat. Good farmers and ranchers know this and strive to see their animals treated well, as it’s a moral issue that also directly affects their pocketbooks.

AG

Kronobergsgatan 37

Stockholm, Sweden

tel: (+46) 8-410-61-00 • restaurangag.se

One of the inspirations for this book, the remarkable Swedish steak house AG has taken steak to a new level of fetishization. It is housed on the second floor of an old industrial building—it used to be a silver factory, hence the name AG, the chemical symbol of silver—and the entrance brings you immediately face-to-face with the glass-walled dry-aging room in which numerous sides of beef are hanging.

AG was one of the first places to look at steak not just as beef, but as a vehicle for expressing characteristics of breed, place, and farmer. It typically carries dry-aged steaks from Sweden, Highland steaks from Scotland, and selected beef from Poland, which owners Johan Jureskog and Klas Ljungquist say is tragically overlooked as a beef-producing country. Its industry has yet to industrialize, they say, and thus the cattle live long, calm, pastoral lives on grass. The deep, beefy steaks those Polish cattle provide are worth traveling to Sweden for.

How cattle are fed is another huge discussion in the beef world these days. Grass fed and grain fed have become loaded terms that generate discussion and sometimes heated reactions. And while the focus of this book is on the flavor of beef, the issues surrounding how cattle are fed have implications far beyond the kitchen, into the realms of animal welfare, public safety, the environment, climate change, and more. It would be improper to pretend they don’t exist and ignore them here. Yet hundreds of articles and books and a number of films have been made that look into the beef cattle industry in this country, so this section will simply summarize the main points of discussion in the hope that you will be inspired to look more deeply into these heady questions.

But before that, let’s answer the big, simple question about flavor: which steak should you seek out, grass fed or grain fed?

Of course, everyone’s taste is different. But in terms of flavor potential, the answer is grass fed. If you like beef with lots of complex, beefy savor, and flavor matters to you over tenderness, then there’s no question that you should seek out the best grass-fed beef available. And it makes sense: A diet of forage—including grass, herbs, legumes, and forbs—simply incorporates a far greater diversity of nutrients than a diet of corn. The nutrients from forage make their way into the meat and fat of the animal and eventually express themselves as flavor.

Occasionally this flavor is even visible. You can see it in the yellow tint of the fat of a grass-fed cow that has lived long enough to bank the nutrients. The color comes from beta-carotene, a natural form of vitamin A and an antioxidant. Beta-carotene gives produce such as squashes, pumpkins, and carrots their signature yellow-orange colors but also occurs in the grasses and legumes that comprise a lot of pastureland. Fat soluble, it gets stored in the fat of grass-fed beef and is transferred to people who eat the meat.

Grain-fed beef, on the other hand, will have less flavor. This is preferable to those who shy away from strong flavors in their food. And for those who demand more flavor, dry aging of the meat can augment that to a degree. But grain-fed beef is also likely to be more tender, especially on the high end of Prime and in high-graded Japanese Wagyu. After all, cattle fattened on grain will move less than cattle that graze openly in a field. Reduced movement equates to less developed muscles and more tenderness. Furthermore, the kind of fat that creates marbling, which is deposited during the months the animals are on high rations of corn, is the kind of fat that melts at low temperatures, providing in the mouth the sensation of juiciness and silkiness.

But these days it’s difficult to make beef choices in a vacuum, ignoring the social, ethical, economic, and environmental questions at the heart of this divide.

THE CASE FOR GRASS FED

“What I can tell you is this,” says Dr. Allen Williams, “well-produced grass-fed beef far surpasses grain in flavor and quality. If you can seek out and find the right grass fed, it’s far more memorable.” That Williams says this is not surprising, considering he’s one of the leading consultants on grass-fed beef on the continent, traveling all over North America to help ranchers get their soils and grasses to optimum condition for grazing their animals. Grass is his life. But he also worked for a long time with grain-fed beef on his family’s own ranch and once considered himself a proponent of it.

One of the challenges facing grass-fed beef as a category, however, is that not all of it is good. Indeed, it’s depressingly easy to get a disappointing grass-fed steak these days, and grass-fed beef has gotten a bad rap because of that. And the stakes are high for the grass-fed movement (no cheap pun intended): one unsatisfactory experience of grass-fed beef apparently has the ability to turn people off it for life.

That drives Williams crazy. “Not all grain-fed beef is good,” he says. “A lot of it is really bad, and people seem to forget that. No one ever says, ‘I’m swearing off beef because that one steak I had was tough [or flavorless or off].’ They keep buying it. So why do people put that onus on grass fed? They should be fair and judge their grain-fed beef just as honestly.”

People aren’t as tough on grain fed as they are on grass fed probably because the former fails less spectacularly. A bad piece of grain fed is likely to be…disappointing, forgettable. It may be flavorless or tough, and it may piss you off because you got ripped off, but it doesn’t turn you off beef in general. A bad piece of grass-fed beef, however, may be pungently gamy or taste like liver and be as tough as nails. Being viscerally off-putting is what makes people say, “Ick, I never want to experience this again.” That one individual steak shouldn’t be an indictment of grass-fed beef, but, alas, it often is, for a number of reasons.

One, we’ve been trained to prefer bland grain-fed beef, which has set the palate for steak in America—tender and sweet. It tastes that way because the cow probably ate more than three thousand pounds of corn in five months. It takes just over two pounds of corn to make one pound of beef. And that’s the same, familiar corn that sweetens most American processed foods.

Also, not all grass fed is the same. Good grass-fed beef requires a real program and real intention. Ranchers need to know how to graze their cattle, to pay attention to what they are eating. They need to harvest them at the right time. A lot of what passes as grass-fed beef in farmers’ markets or roadside stands may simply be from scrawny old dairy cows that were never intended to be great beef. Or perhaps it is cheater grass-fed beef, in which the cattle are confined on a feedlot and just fed concentrated grass pellets, which are legal under the term.

Along the way from birth to slaughter are lots of places for grass-fed beef to go south. Jordan got clued in to this by observing the evolution of Long Meadow Ranch, a farm-to-table operation and wine producer in Napa Valley.

Jordan was excited when he learned the owners had the ambitious program of raising their own herd of Highland cattle for beef to serve at their restaurant in St. Helena and to sell at the farmers’ market. But the first time he tried it, the flavor wasn’t great and the steak was tough. Apparently they recognized this too and were already working to change the program. They started by interbreeding Angus with their pure Highland cattle to try for better-marbled beef. And they put the cattle on richer pastures and also upgraded their selection process for slaughter. Before that, their guy had sort of indiscriminately been choosing animals when the restaurant was running out of beef, paying little attention to the state of the cattle. Now, they’ve learned that they need to be harvesting seasonally in late spring or late fall, when the grass is green and the cattle are on richer forage. They needed a better eye for selecting individual animals who were at their peak. When the grass dries out in the summer, the cattle actually lose fat because they need as much or more energy to digest the dried grass as they get from eating it. The Long Meadow beef sold at the market and at its restaurant Farmstead is now delicious and getting even better. (They’re even opening a butcher shop adjacent to the restaurant.)

Mainstream grass-fed beef has to improve across the board. And another reason to support grass-fed beef and help drive its improvement is that it’s beef in accordance with nature. Pastures are where cattle are supposed to be—and this lifestyle is better for them and better for the world. Indeed, there’s a great pleasure in marveling at the coevolutionary miracle of nature that is the relationship between cows and grass. It’s one of those beautiful examples of symbiosis from which all beings profit.

Ruminants—be they cattle, buffalo, sheep, or elk—both support and feed off the grasses. They protect grasslands by keeping trees and brambles from encroaching, and they fertilize the ground with their manure and urine, spread grass seed, and plant the seed in the soil with their hooves. Grasses grow back stronger than before after being munched on; they evolved to resist the grazing of ruminants. In turn, the cattle get an endless lunch, for they evolved to do something most mammals can’t: digest cellulose. The most abundant organic molecule on the planet, cellulose—an organic structural component of wood, grass, leaves, and the like—is created by plants using the sun’s energy.

Other organisms win in this relationship, too. Grasslands regenerate themselves after grazing (if they are not overgrazed). As they grow, grasses shed their roots, depositing carbon into the soil, and then regrow even more and deeper roots. In turn, this subterranean environment provides home to the thriving community of bacteria and fungi that support countless other organisms by breaking down the organic matter of plants into humus while simultaneously feeding essential minerals from the ground to the roots of the plants. As this soil becomes deeper and more alive, it pulls more carbon out of the air and sequesters it, creating new pathways to store water in the process.

A growing movement of farmers and scientists see cattle and other ruminants as crucial to rebuilding soils worldwide that are being lost to erosion and desertification thanks to deforestation and industrial agriculture. Although some critics say that ruminants are a major cause of climate change, others posit the problem as being that too few of them feed on grass anymore, promoting carbon sequestration.

Humans thrive from the cow-grass relationship, too. We need the sun’s energy to live but can’t get it directly from light. Eating meat is one way to harvest that energy. Basically, when we dine on beef, we are consuming grass and other plants, some of the most plentiful substances on Earth. Raising meat on grass can be sensible ecologically as well. Yes, vegetable and grain crops can also provide energy, but they don’t grow well everywhere. Much of the land on which cattle graze is too stony, arid, and hilly to grow crops profitably without major inputs such as irrigation and fertilizer. But grasses grow in much thinner soils than crops, and the action of ruminants helps soils store water (requiring no irrigation) and fix nitrogen (obviating fertilizer). When it all works as it’s supposed to, it’s a virtuous circle. Indeed, the great deep soils that turned the American Midwest into an agricultural powerhouse were achieved thanks to passage of the bison over grasslands for thousands of years.

Betsy Ross on her ranch outside of Austin, Texas

To get a sense of how right this feels, go out and visit an enlightened grass-fed operation like Betsy Ross’s, just outside of Austin, Texas. There, her herd of Devon cattle graze on a brilliant spread of pastureland—flowering plants, wild herbs, grasses, weeds, and thistles. Ross practices what’s called holistic management. Like most people who observe this, she’d consider herself more a grass farmer than a cattle rancher. Scratch that, they consider themselves soil farmers, as grass and cattle are really just parts of an ecosystem that builds soil. And that soil is what keeps the ecology in balance, supplies water when it’s scarce, and keeps the climate stable. The cattle, busy munching away and not at all afraid of the humans standing amid them, seem happy. The meadow is robust and full of life. It just seems good.

“When we started this in 1992, the prevailing wisdom was that we couldn’t do this,” says Ross, a spry woman of seventy-eight. “The prevailing wisdom said you couldn’t raise them for their lifetime on grass without supplementing. At that time, the cost of carrying a cow through the winter was $513, so you had to sell for more than that to break even. Now it’s up to about $750. We don’t spend nearly that because we’re powered by the sun, not chemicals. We spend that money on people here.”

Ross looks at herself as a steward of a system that can manage itself. “We don’t feed minerals, we let the weeds bring the minerals up. It’s a harmony. It’s a symphony. Sometimes the animal itself is the dominating figure, other times the grass is, other times the insects, other times the water. Grass-fed beef is an experience not just about raising beef. Hopefully you feel good; there’s a different energy here.”

She’s right. And when you eat her beef, you get a different feeling. It tastes different from conventional beef. She gave some to Jordan, and he served it to a bunch of friends along with some steaks from other producers. It was one of the favorites of the group and elicited an unusual comment. One diner said, “It’s so mineral—like eating an oyster. It doesn’t taste like an oyster,” she added, but noted that you get a rush from a sensation of minerals surging into your body.

That wasn’t an overstatement. Grass-fed beef is significantly higher than grain fed in beta-carotene, selenium, potassium, magnesium, zinc, and more. And there’s that fatty acid profile: grass fed is higher in healthy conjugated linoleic acid.

So, grass-fed beef is better for humans, cattle, microbes, and the health of the entire planet. What’s not to like? Ah, yes, the flavor of that beef. That’s where it becomes incumbent on the ranchers themselves to make this work. They must be aware of the necessity of having truly delicious grass-fed beef to offer. It means making sure the cattle’s diet of grass and silage is rich and diverse. This requires only harvesting it when the beef is full and marbled, which generally means an older animal. But we diners should also open our minds to a product with a slightly different flavor than what we’re used to. Also, we must remember that grass-fed beef is an agricultural, not an industrial, product, and is therefore as prone to variation as the produce we find in the store. But the more we support the good grass-fed producers with our dollars, the greater the incentive for others to join the cause and up their game.

THE TRUTH ABOUT GRAIN FED

Arguments supporting grain feeding of cattle are far slimmer than the very brief summary of the benefits of grass feeding just offered. Grain feeding might produce some qualities of beef that we like, but quite simply its existence represents the opposite of a harmonious natural system. After all, feeding cattle massive amounts of corn perverts what Mother Nature intended for ruminants. Instead, it represents a solution to the man-made political, economic, and industrial problems of overproduction of corn. As Michael Pollan lays out in The Omnivore’s Dilemma, the roots of this problem, which are deep and convoluted, involve the shift to producing industrially made, petroleum-based chemical fertilizers in order to use up the vast surplus of ammonium nitrate, a key ingredient in explosives, left over after World War II. New hybrid strains of corn (which grow faster and with higher yields than heritage breeds) required the huge amounts of soil nitrogen only these fertilizers could supply. Suddenly, corn farmers could produce exponentially more corn per acre than had ever been possible in history.

Starting in the 1950s and surging in the 1970s, issues relating to politics, economics, and food security pushed farmers to overproduce corn. Despite the resolution of these issues, production has remained ridiculously high, which theoretically should drive down the price and cause farmers to cut production. But because, for political reasons, politicians have continually supported farmers with direct payments, there has been no incentive to slow cultivation. In short, the corn market is artificially supported by tax dollars.

Something had to be done with all that corn, and the idea was hit upon to use its calories systematically to fatten the country’s cattle, fundamentally changing the traditional life cycle of the cow. It’s not new to supplement a cow’s diet with grain, but it is new to only or primarily feed cattle grain for a good chunk of their lives.

Whereas in the past a beef cow’s life would have been largely spent on pasture, now they spend only the first five or six months on pasture before heading to feedlots. Here’s where the race to fatten them as quickly and as cheaply as possible begins until they make a decent weight and head off to slaughter. This whole system has been much documented, so it won’t be belabored here. But you should probably know that much of the cattle raised to produce industrial beef have been given antibiotics to stave off infections caused by confinement in overcrowded living quarters and by problems associated with a corn diet. Cows can tolerate eating corn as long as it is accompanied with the right percentage of roughage. Too much corn causes fatal bloating and painful acidosis. Hormones and other chemicals are also given to speed growth. Today, cattle are being specifically bred to better tolerate a corn diet (salmon are too). A balance of grass in the diet can alleviate these issues, but it will also slow down the fattening.

Corn feeding does fatten the animals quickly and causes them to marble well. That greater marbling (see this page) is the driving force of the government’s beef-grading system is simply a reinforcement of this perverse economy. Cementing the system, in just seventy years, the American taste for beef has become the sweet, tender meat produced by feeding cattle corn.

The typical American beef cow will spend its first five or six months on grass with its mother in what are known as cow-calf operations. These are mostly small, family-run farms, and there are hundreds of thousands of such operations across the country. They are the idyllic places where young cattle do what they’re supposed to do. Indeed, cattle are routinely trucked all over the country to places grasses grow best to complete this stage of life and then shipped back for the next. When they reach five or six hundred pounds, they’re transitioned for life in the feedlot.

Not all feedlots are the wretched, filth-strewn cow megacities that have been (rightfully) demonized. Some are much more humane, clean, well-kept places. Pollution from decomposing manure and runoff are serious environmental problems, however. Nevertheless, the feedlot is where the cattle put on their next five hundred to seven hundred pounds as quickly as possible. When they reach the correct weight and form, they are sold back to the beef processors. Most beef cattle are slaughtered between thirteen and eighteen months. It could take a grass-fed animal another year to make it to the twelve-hundred-pound weight preferred at slaughter. That’s another year or more of not profiting on the animal. And 85 percent of all beef comes from the big four processors: Cargill, National, JBS, and Tyson.

The arguments in favor of this system basically amount to this: If we didn’t have the ability to grow these massive amounts of corn (and soybeans) we wouldn’t be able to feed all of the people on the planet. Technically, concentrating beef cattle on feedlots could preserve the land needed to graze them for better uses. Raising cattle does require considerable land and time. As a food source, the current system may be faster and cheaper. What those costs would be without subsidized corn, however, are up for debate. Some estimates suggest a 33 percent increase in price, but it would probably be a lot more.

The best argument for grain-fed beef is that people really like it. And, no question, there is some exceptional grain-fed beef out there, brands such as Creekstone and HeartBrand. But at what cost do we maintain this system?

GRAIN FINISHING

Not all grain finishing is the same. It’s not hard to find beef marketed as grass fed but grain finished. In basic terms, that means very little. It could describe cattle that spent six months on a corn diet in a concentrated feedlot. Or it could be used for pastured animals that spent their last month on a diet supplemented with a mixture of non-corn grains—millet, rye, oats—grown organically on the very farm where they were raised. Many ranchers believe such a way of finishing the cattle gives them a little extra marbling and perhaps tones down any edgy flavors the beef might have gained from time on grass. Grain finishing of this type may sweeten and soften the meat, making it more palatable, but the longer the time off grass, the greater the reduction of healthy compounds and fatty acids.

Age

The one piece of the beef flavor puzzle that goes missing in this country is the factor of age. Meat from older animals has more flavor. If you want proof, go to Spain. Here in the United States, producers pride themselves on the quickness they can get a cow to slaughter, the younger the better. If they can be harvesting cattle at twelve months, they are really making money. In Spain, people celebrate how old the cow is.

Jordan experienced this firsthand on a trip to Spain. He was in the town of Ávila, just randomly at a meat restaurant on the outskirts of town. This place specialized in beef, so he ordered a ribeye. It was lunch. When the beef came out and was set in front of him, his saliva glands instantly started firing. No steak he’d ever had smelled so beefy. First bite, he couldn’t believe what he was tasting. It was a deep, rich, savory sensation of beef he’d never experienced before. He found himself thinking, “Maybe Spain has the best-tasting beef in the world.” That steak became one of the inspirations for this book. It came from a steer about six years old. Was it tender? He can’t remember. That didn’t even matter because it tasted so damn good.

Older animals always have more intense flavor than younger ones. It’s true in chickens and it’s true in cattle. Sadly, for reasons of economics, in the United States our industries are incentivized to harvest animals as young as possible, meaning that flavor is greatly diminished. We eat a lot of incredibly bland meat, hardly ever experiencing what true chicken flavor or real beef flavor is all about.

True flavor comes from animals that have lived life. A steer’s work, its movement, and its diet are what create flavor. The longer it’s had to live, to move, and to eat a variety of foods, the more savory and beefy it’s going to become. Wagyu cattle, for instance, are slower maturing. This means that it takes them longer to get to slaughter weight. It makes the meat more expensive but also explains some of its enhanced flavor. Age also accounts for some of the flavor advantages of good grass-fed beef. Because grass-fed cattle take longer to reach a decent slaughtering weight, they not only move more in their lives, building more flavorful muscles, but also spend more time putting on weight. Consequently, grass-fed beef usually has more flavor.

The gastronomic argument against older cattle usually has to do with tenderness. In some studies, many Americans have stated a preference for tenderness over flavor. So long as the steak is juicy and melts in your mouth, people don’t seem to care that it’s bland. When a cow lives only fourteen months and is fed corn for almost half that time, it’s had little chance to develop flavor but it will likely be tender. But for those who love flavor and don’t mind a little chewiness, there are few choices.

The limiting factor for raising older animals, of course, is cost. No rancher wants to pay to feed a cow an extra six months or a year or four. It’s expensive and risky (more opportunities for the cow to get sick or injured), and at this point, there’s not a market where the cost of the steak can be high enough to recoup that investment.

But in other countries that market exists. In Spain, farmers will take dairy cows who have retired from producing milk after four or five years and put them back on the pasture for another few years. Now, you’re getting a cow that is eight years old. Or there’s the madness of chef José Gordón of El Capricho (see this page), who buys oxen at three years old and pastures them on his ranch (at great expense) in León Province until they’re ready, usually between eight and twelve years of age. This might be the most flavorful steak in the world.

Of course, we have older cattle in the United States, and they do get slaughtered—just not for steaks. Indeed, one of the little-known facts about hamburgers is that one reason they’re so beefy and delicious is because much of their meat comes from older cows whose steaks would be too old to get a grade of Prime or even Choice. This instantly downgrades them into the category of cheap meat, so—no matter how flavorful—they usually go into hamburger. This is great for the nation’s hamburgers, but, if handled with more care and intention, older beef could be used more profitably and perhaps satisfy people in other ways.

While Spain is the king of old cows, things may be changing in favor of older beef in other countries. High-end food scenes in Europe are catching on to the deliciousness of steaks from older cattle, and Spain can provide only so many (older cattle are a diminishing resource). However, the new taste for highly flavored meat from old cows may spark other countries to convert part of their industries to conserving and reconditioning older cattle.

Will Americans ever develop such a taste? Glenn Elzinga, of Alderspring Ranch in Idaho, is doubtful. “In Spain or France, those people can tolerate an incredible amount of flavor, but Americans are on Nebraska corn-fed beef since 1950,” he says. “Even people who are food people are not ready for the intensity of flavor development after thirty-six months. I can eat that intense steak off our grass. That is an intense steak. But I serve up this incredible steak to people, and they can’t handle it. They’ll say it’s too beefy. We have an American clientele who are steak lovers but have never really experienced flavor of that intensity, and as a result, it’s a no sale.”

But perhaps a high-end market could be developed for a small number of people who love the taste of beef and are willing to pay extra to support older cattle. In California, a top-end meat supplier called Cream Co. is experimenting with just this—putting retired dairy cattle onto pasture for a time to recover and develop more fat. At a tasting in Austin with Cliff Pollard, Cream Co.’s founder, we tried some of this steak, and it was outstandingly flavorful and not at all tough. Not quite at the level of Spanish beef, but highly encouraging. It doesn’t seem ridiculous to think that such a market could develop in the United States.

The Upshot

In the interest of flavor and eating experience, what is the hypothetical best steak you could buy? It would be from a grass-fed, grass-finished animal at least five years of age. Right now, that steak doesn’t exist in the United States. So beyond that, in the realm of choice, what should you look for?

Some good-tasting corn-fed beef is out there, but it’s few and far between. Most of it—and the vast majority of beef in this country—comes out of a system that does not produce much good meat and is also negative in terms of animal welfare, public health, and the global environment.

Grass fed is the right way to go for reasons of health, social responsibility, and—at its best—taste. But finding great grass-fed beef isn’t always easy. The best thing to do is locate a great source and support that producer. It will likely be more expensive and harder to source. If that’s worth it to you, then consider the idea of eating less but higher-quality steak.

THE HOLY GRAIL OF AMERICAN BEEF?

They call it “grass-fed gold.” Just as we were finishing the book, we made a steak discovery that could be a game changer in the United States—at least for those of us who want fuller-flavored, well-marbled grass-fed beef. Most people think that’s impossible, but it’s not. It simply requires older cattle—cattle that no one was committed to keeping around and feeding until now. Enter Carter Country Meats, a family-owned ranch and beef business in Wyoming. For the first time, they are marketing dry-aged beef from five- to ten-year-old cattle that have grazed on nothing but mountain pasture their entire lives (save the winters, when they are fed home-grown and fermented silage). The beef is exquisite, with a deep, beefy savor, long-lingering flavor, and a remarkable degree of tenderness. And it came about mostly by accident.

RC Carter and family manage a cow-calf operation on forty-five thousand acres of mountain pasture in the Bighorn Range and an additional four hundred square miles of rangeland in southern Wyoming. They maintain a large herd of cattle throughout the year, including cows from five to ten years of age that have gone dry and stopped becoming pregnant. The typical fate of these animals is to be sold on the commodity market, where they fetch sixty cents a pound (or about nine hundred dollars an animal). “That’s not a lucrative profession,” says RC. “The commodity guys have convinced everybody that these cows aren’t worth anything. They usually try to discount you because they’re so old.” RC wouldn’t have known any better himself, but he happened to see Steak Revolution, a 2014 French documentary that included José Gordón of Spain’s El Capricho (see this page) talking about turning his older oxen into some of the best steaks in the world.

RC got an idea. He gathered his dad and brother and they drove down to southern Wyoming to check out their cattle. “There are wild horses roaming and antelope and our cows, just purely on open grassy range. We spent a week gathering up all of these cows [as they now do annually], and some of them were superfat. Having eaten grass all summer long, they looked like finished beef.” The Carters took nine of them. Shockingly (to them), 30 percent graded Prime. “They were considered throwaway cows,” says RC, “but it turns out they’re better than the younger animals anyway—hands-down. If I sold them commodity, I might get nine hundred dollars a cow, but that same animal I can sell to Nate for four thousand dollars.”

Nate is Nate Singer, a talented butcher who runs Black Belly, a great shop in Boulder, Colorado. Having grown up in Wyoming, Nate knew the Carters and he also knew good beef (his dad is a butcher with a restaurant in Cody). Now, in addition to holding down his job at Black Belly, he serves as an ambassador and agent for Carter Country’s beef program. “I’ll never forget those first animals we harvested,” says Nate. “Their meat was gorgeous, their fat a deep yellow color. They were the most beautiful animals. ‘Grass-fed gold’ is what we called it.”

Nate says that the biggest problem with selling older cows is dry aging. Older grass-fed animals (and there aren’t older grain-fed ones because no one will pay to feed them corn for more than a few months) will have more developed muscles, so they need some dry aging for tenderness. But dry aging has been next to impossible to come by for older cattle because of the thirty-month rule.

What’s the thirty-month rule? That’s the rule the USDA imposed that says cattle slaughtered over the (rather arbitrary) age of thirty months need to have their spinal column (and certain other parts) separated from the carcass before the meat leaves the slaughterhouse, to prevent mad cow disease. Whether that’s reasonable or even necessary is a whole other argument, but it’s the law. Because of this rule, slaughterhouses are loathe to process older animals because they require a special run, with thorough cleaning of equipment before going back to conventional younger cattle, which make up almost all their business. Furthermore, beef wholesalers don’t want to age the meat, because in losing the spine bones a valuable form of protection from dehydration is gone. And finally, there’s a bias against older animals in the USDA grading protocol, meaning they can’t grade high on the commercial scale no matter how marbled the meat. Basically, the entire system is rigged against older cattle.

“When you think about raising grass-fed beef,” Nate says, “well at thirty months of age, the animal is like a fifteen-year-old kid—they’re skinny, hyper, and nuts. But when they get older, they start to marble and hold fat on their carcasses. By the time they’re five to six years old, they’re starting to pack it on, this beautiful golden-tinged fat.” As for the expense most ranchers face when keeping animals past the typical twenty-four to thirty months, well that’s where the Carter family’s access to forty thousand acres and twenty-seven natural springs comes in. “It’s why we’ve got to conserve these old ranches and land,” continues RC. “This is beautiful cattle country that grows its own resources in grass and water. It’s the opposite of a feedlot that’s a drain on resources.”

Nate and RC were able to work a deal with a local slaughterhouse to harvest their older cows once every two weeks and then hang the whole carcasses anywhere from fourteen to forty days, depending on space. The spines are removed just before the meat is shipped. Nate may age some other cuts longer in his shop, but there are no porterhouses or T-bones (because the spine has been removed). They hope to create some greater slaughterhouse flexibility in the future to expand their offerings.

Eating older cattle is an answer to many of the beef industry’s annoying problems. The meat tastes exponentially better. It’s from untreated, 100 percent grass-fed cattle that live a bountiful life as they were meant to live, while regenerating open rangeland and consuming only naturally occurring resources. Ranchers make more money and carnivores can have a better experience. Much like California’s Cream Co. (see this page), which is revitalizing older dairy cows on grass before sale, it’s a win-win-win for all involved. Now if only the entire industry would get involved, we would have a real steak revolution.