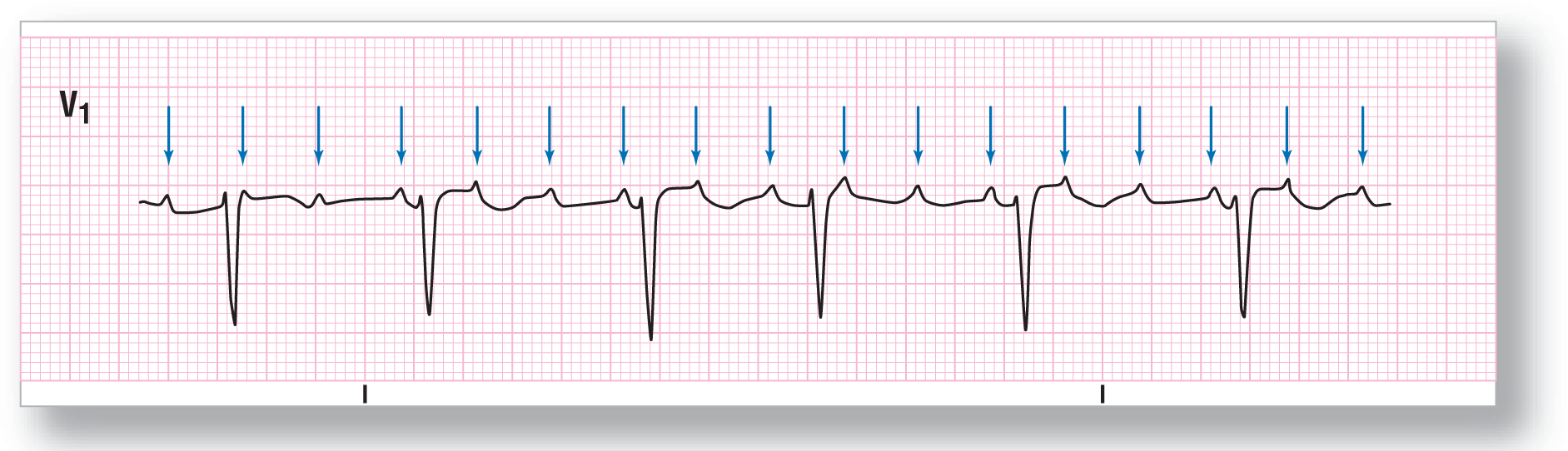

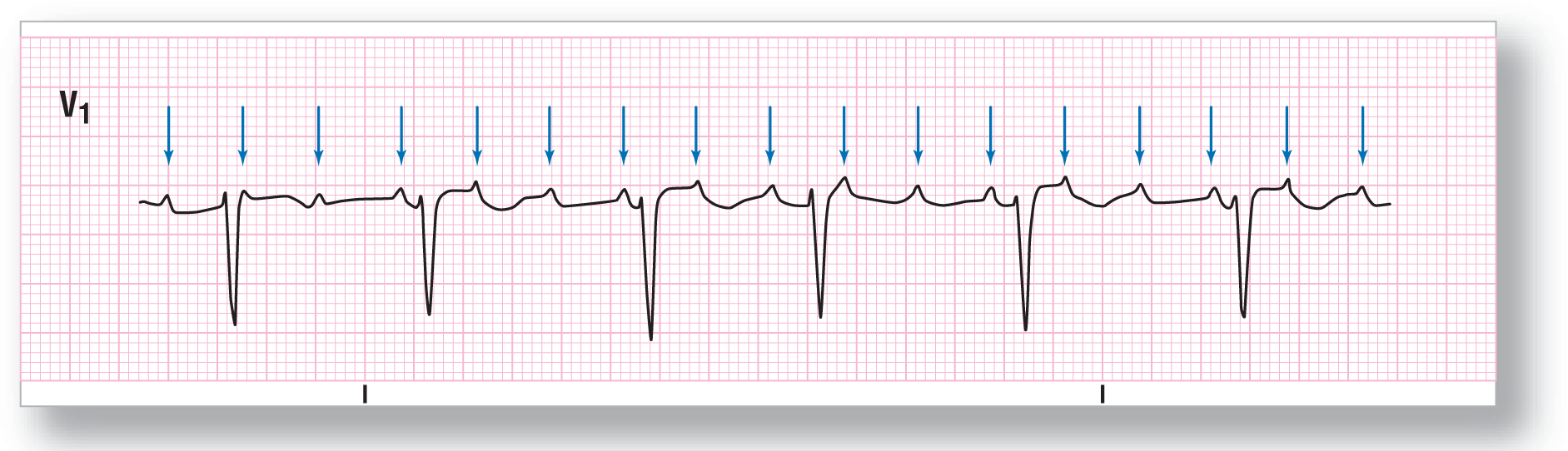

Figure 16-1 Focal atrial tachycardia with variable block. The P waves have been marked with a blue arrow for easy identification.

From Arrhythmia Recognition: The Art of Interpretation, courtesy of Tomas B. Garcia, MD.

The diagnostic criteria for focal AT with block (Figure 16-1) are as follows:

Figure 16-1 Focal atrial tachycardia with variable block. The P waves have been marked with a blue arrow for easy identification.

From Arrhythmia Recognition: The Art of Interpretation, courtesy of Tomas B. Garcia, MD.

We know that focal AT is caused by a rapid atrial impulse going about 100 to 200 BPM (can go as high as 250 BPM or, very rarely, even higher). Focal AT with block is at the faster end of that spectrum, at about 150 to 250 BPM or higher in rare circumstances. So far, however, we have only seen strips where each P wave triggered off a QRS. Now, we will address those times where it takes more than one P wave to trigger an individual QRS.

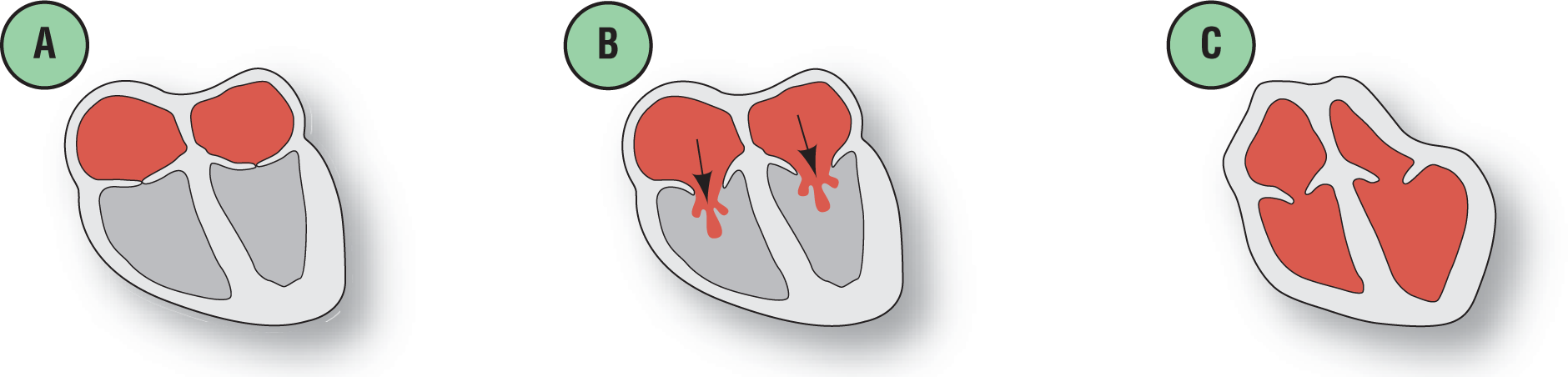

As we discussed in Chapter 6, Electrocardiography and Arrhythmia Recognition, it is a proven fact that the heart does not like very fast rates—ventricular rates to be exact. Why? At very fast ventricular rates, the ventricles do not have time to adequately fill. Remember from physiology that the largest amount of ventricular filling occurs during diastole, when the atrioventricular valves open up and a rush of blood floods the ventricular chamber (Figure 16-2, A and B). This is known as the rapid filling phase of diastole. Near the end of diastole, when the ventricles are almost full, the atria contract and push a little extra blood into the ventricles to overfill them (Figure16-2C). This overfilling stretches the cardiac muscle and helps to improve contractility. The net result is a strong ejection of blood into the aorta that is needed to maintain blood pressure. This mechanical process takes time—time that is missing in a rapid tachycardia.

Figure 16-2 Rapid filling phase and the overfilling caused by atrial contraction.

© Jones & Bartlett Learning.

So, how do the ventricles protect themselves from the rapid onslaught of the atrial impulses coming at them from above? They use their built-in gatekeeper, the AV node, to block some of the impulses from reaching them. The extra time created by the blocked atrial impulses allows the ventricles to fill appropriately, thereby maintaining cardiac output. Do the extra atrial impulses superfill the ventricles? No. The reason is that the atria are not filling to maximal capacity themselves, so the amount of blood they eject into the ventricles is minimal. So, as we can see, the AV block is quite protective in cases of rapid focal AT and is a survival tool for the body.

Focal AT with block is always associated with either second- or third-degree AV blocks. Type I blocks just wouldn’t allow the time needed by the ventricles to adequately fill. Wenckebach, type I second-degree AV block, or type II second-degree AV block can be seen.

Describing a focal AT with block verbally is a bit more complex than, say, describing a sinus tachycardia. The higher level AV blocks create a different atrial rate and ventricular rate. In addition, either the atrial or ventricular cadence can be regular or irregular. The correct way to describe these complex rhythms is to first describe the atrial events and then the ventricular events. We would describe the strip by saying that there is a focal AT at a rate of ____ BPM associated with a (second/third/variable) degree AV block with (2:1/3:1, etc.) conduction causing a (regular/irregular) ventricular response at _____ BPM. (For further discussion on the AV blocks, see Chapter 28, Atrioventricular Blocks.)