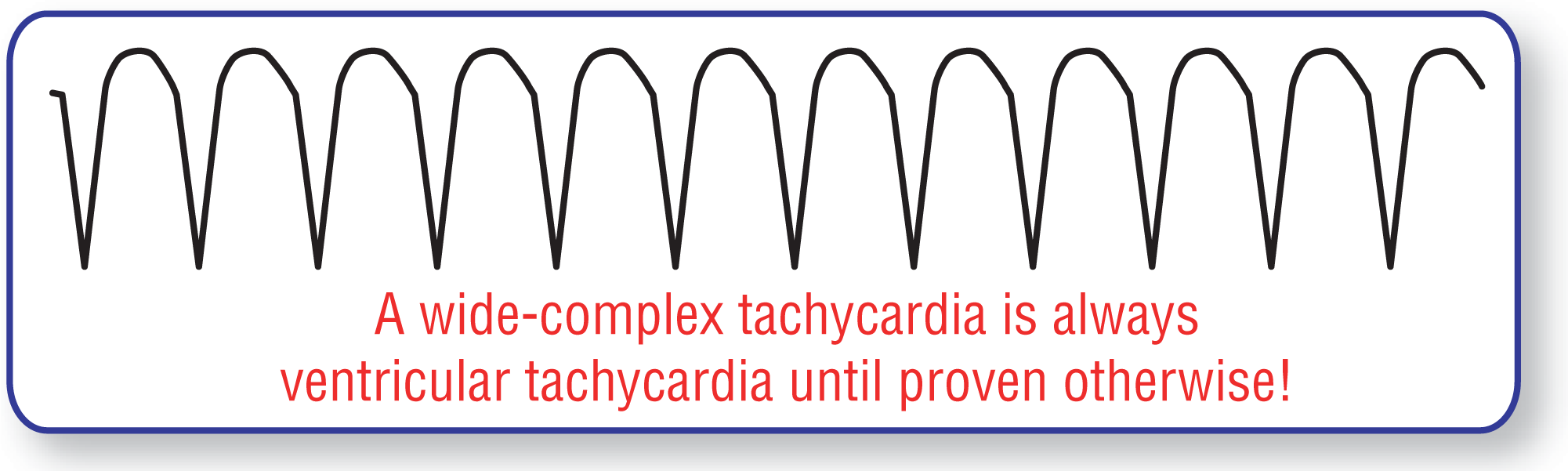

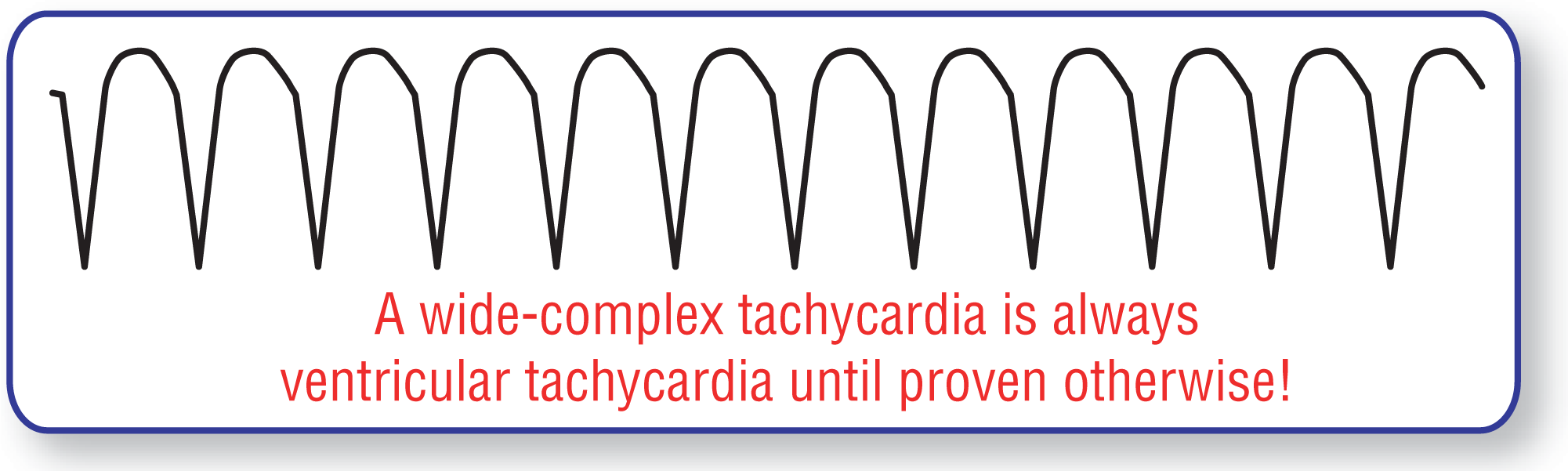

Figure 32-1 Monomorphic ventricular tachycardia. Note the uniform appearance of the complexes in this strip, and the rapid rates above 100 BPM.

© Jones & Bartlett Learning.

In this chapter, we will be reviewing one of the deadliest arrhythmias we will cover in this text: ventricular tachycardia (VTach). In reality, VTach can produce a spectrum of disease, ranging from a completely asymptomatic presentation to sudden cardiac death. It is the latter part of this spectrum that gives VTach its fearsome reputation. Together, VTach and ventricular fibrillation account for over 300,000 sudden cardiac deaths in the United States each year. The numbers of hemodynamically stable or mildly unstable VTach are not known but have to be much, much greater. Because of these numbers and the life-ending potential of this arrhythmia, VTach deserves our full attention and clinical respect.

The definition of ventricular tachycardia is simply the presence of three or more ectopic ventricular complexes in a row with a rate above 100 beats per minute (BPM). The rates for VTach fall between 100 and 200 BPM, but it is most commonly found running between 140 and 200 BPM. Rates above 200 BPM can occur, and when they do, the morphology of the complexes slowly begins to blur with less discernible QRS, ST, or T waves. In fact, the complexes actually become sinusoidal in morphology. When this sinusoidal pattern occurs and the rate is above 150 BPM, we call it ventricular flutter.

Morphologically, we can break down the definition of VTach a bit further. If all of the complexes have identical and uniform morphologies, the rhythm is called a monomorphic ventricular tachycardia (Figure 32-1). If the morphologies of the complexes change from beat-to-beat, the rhythm is called a polymorphic VTach. Monomorphic VTachs are more commonly seen in clinical practice than the polymorphic variants. We will be looking at monomorphic VTach closely in this chapter and polymorphic VTach in the next chapter.

Figure 32-1 Monomorphic ventricular tachycardia. Note the uniform appearance of the complexes in this strip, and the rapid rates above 100 BPM.

© Jones & Bartlett Learning.

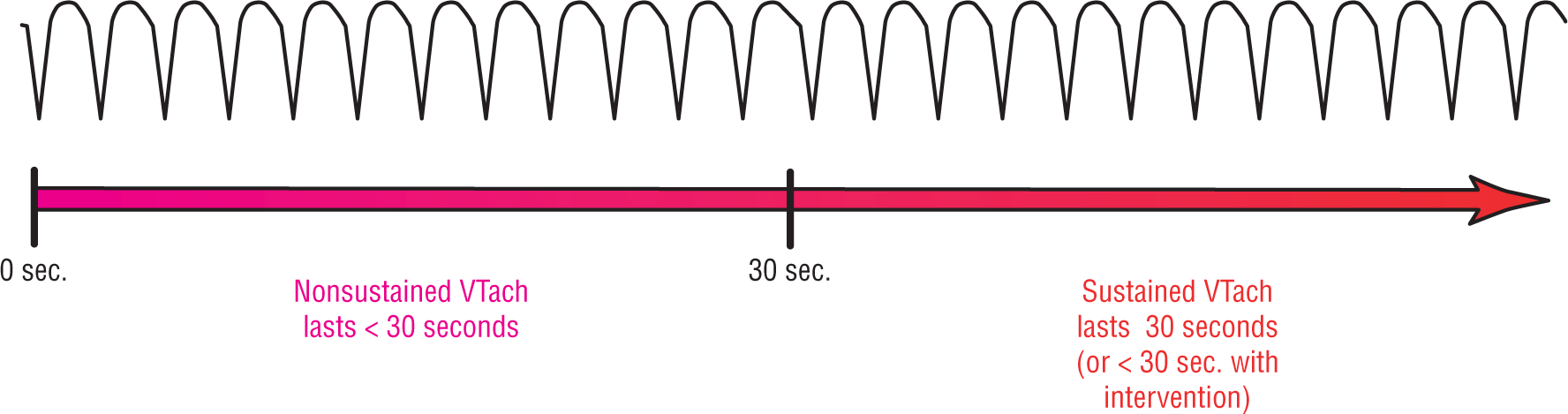

The terminology gets even more specific when we talk about the duration of the arrhythmia over time. If the arrhythmia lasts less than 30 seconds, it is labeled a nonsustained VTach (Figure 32-2). If the arrhythmia lasts 30 seconds or longer, or if clinical intervention is needed to prevent cardiovascular compromise (hypotension, chest pain, ischemia, severe dyspnea, etc.), the arrhythmia is labeled a sustained VTach. Finally, if the arrhythmia is present most of the time, it is known as incessant VTach.

Figure 32-2 Nonsustained and sustained VTach.

© Jones & Bartlett Learning.

We will begin our detailed look of monomorphic VTach, both nonsustained and sustained, by looking at the possible mechanisms that can give rise to it. We feel that in order to understand this deadly arrhythmia and its treatment, we need to thoroughly understand how it is created. After we have looked at how it is formed, we will take a closer look at the morphology and how to diagnose it. Finally, we will look at the nonsustained and sustained forms of this rhythm disturbance separately, focusing on their differences.