p. 213).

p. 213).Prescribing—general considerations

How to prescribe—best practice

Reporting adverse drug reactions

Enzyme inducers and inhibitors

Exposure to safe prescribing is increasing in medical schools, yet it is only really when you are faced daily with drug charts and decisions that you get the hang of it. Even the most experienced of doctors will only know by heart the dose and frequency of a maximum of 30–40 drugs, so do not worry if you cannot remember everything. Start basic: paracetamol for adults is 1g/4–6h PO, max 4g/24h in divided doses ( p. 213).

p. 213).

Many medical errors in hospital involve drugs, so it is important to consider a few things every time you want to prescribe a drug, rather than just writing a prescription as a knee-jerk reaction.

Indication Is there a valid indication for the drug? Is there an alternative method to solve the problem in question (such as move the patient to a quiet area of the ward rather than prescribe night-time sedation)?

Contraindications What contraindications are there to the drug? Does the patient have asthma or Raynaud’s syndrome, in which case β-blockers may create more problems than they solve.

Route of administration If a patient is nil by mouth (NBM), then it is pointless prescribing oral medications; use the BNF or ask the pharmacist to help you use alternative routes of administration. Remember IM and SC injections can be painful, so avoid these if possible.

Drug interactions Some drugs are incompatible when physically mixed together (eg IV furosemide and IV metoclopramide), and other combinations cause physiological problems (eg ACEi with K+-sparing diuretics). Look through the patient’s drug chart to spot potential drug interactions ( p. 173).

p. 173).

Adverse effects All drugs have side effects. Ensure the benefits of treatment outweigh the risk of side effects and remember some patients are more prone to some side effects than others (eg Reye’s syndrome in children with aspirin, or oculogyric crises in young females with metoclopramide). Some side effects should prompt urgent action (such as stopping statin drugs in patients who complain of muscle pains, or patients who get wheezy with β-blockers), but others can be advantageous if they do not expose the patient to unnecessary risks (such as slight sedation with some antihistamines).

Administering drugs Always double check the drug prescription and the drug with another member of staff (qualified nurse or doctor). This is not a sign of uncertainty, this is a sign that you are meticulous and will greatly limit the chance of a drug error occurring, which would make you look careless. Equally, if you are asked to check a drug calculation then take it seriously and pay attention (often this means performing the drug calculation again yourself).

► If in doubt Never prescribe or administer a drug you are unsure about, even if it is a dire emergency—seek senior help or consult the BNF or a pharmacist.

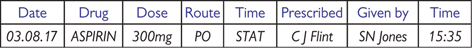

The drug card There are usually at least four drug sections (Figs 4.1–4.3); once-only/stat doses, regular medications, PRN (‘as required’) medications, and infusions/fluids ( pp. 394–397). Other sections include O2, anticoagulants, insulin, blood products (often a separate card), medications prior to admission, and nurse prescriptions.

pp. 394–397). Other sections include O2, anticoagulants, insulin, blood products (often a separate card), medications prior to admission, and nurse prescriptions.

Labelling the drug card As with the patient’s notes, the drug card should have at least three identifying features: name, DoB, and NHS number (the NPSA advice is that the NHS number should be used whenever possible). There are usually spaces to document the ward, consultant, date of admission, and number of drug cards in use (1 of 2, 2 of 2, etc.).

The allergy box Ask the patient about allergies; check old drug cards if available. Document any allergies in this box and the reaction precipitated; eg penicillin → rash. If there are no known drug allergies then record this too. Nurses are unable to give any drugs unless the allergy box is complete.

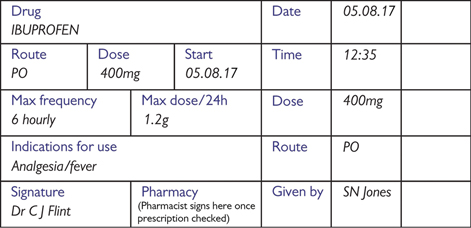

Writing a prescription Use black pen and write clearly, ideally in capitals. Use the generic drug name (eg diclofenac, not Voltarol®) and clearly indicate the dose, route, frequency of administration, date started, and circle the times the drug should be given (Figs 4.2 and 4.3). Note that some drugs do require generic names in addition to brand names—often the case with medications used in Parkinson’s disease. Record any specific instructions (such as ‘with food’) and sign the entry, writing your name and bleep number clearly on the first prescription. See Box 4.1 for verbal prescriptions and Box 4.2 for self-prescribing.

Electronic prescribing Many hospitals now employ electronic services to help with prescribing. There is no universal system so try to become familiar with your system as quickly as possible—check with your ward pharmacist or colleagues if you need a refresher.

|

|

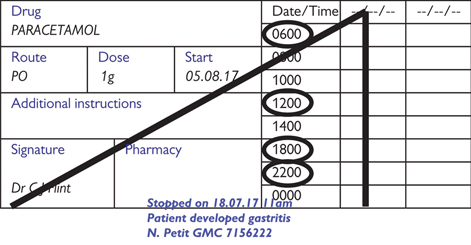

Changes to prescriptions If a prescription is to change, do not amend the original; cross it out clearly and write a new prescription (Fig. 4.1). Initial and date any cancelled prescriptions. It is essential that you record the reason (eg β-blocker stopped in wheezy asthmatic patient), otherwise someone else might not realize why it was stopped and re-prescribe it.

Rewriting drug cards When rewriting drug cards, ensure the correct drugs, doses, and original start dates are carried over and that the old drug card(s) are crossed through and filed in the notes.

Fig. 4.1 Example of cancelled drug prescription for a regular medication.

Fig. 4.2 Example of drug prescription for a PRN medication.

Fig. 4.3 Example of a once-only (STAT) medication.

Box 4.1 Verbal prescriptions

Verbal prescriptions are only generally acceptable for emergency situations, and the drug(s) should be written up at the first opportunity. If a verbal prescription is to be used, say the prescription to two nurses to minimize the risk of the wrong drug or dose being given. Check your local prescribing policy first.

Box 4.2 Self-prescribing

F1s can only prescribe on in-patient drug cards and ttos. The GMC’s ‘Good Medical Practice’ guidance (2013  www.gmc-uk.org/guidance/good_medical_practice.asp) states you should ‘avoid providing medical care to yourself or anyone with whom you have a close personal relationship’. Do not get tempted or pressured to ignore this.

www.gmc-uk.org/guidance/good_medical_practice.asp) states you should ‘avoid providing medical care to yourself or anyone with whom you have a close personal relationship’. Do not get tempted or pressured to ignore this.

A list of specific drug interactions are shown in Appendix 1 of the BNF.

Pharmacokinetic interactions Occur when one drug alters the absorption, distribution, metabolism, or excretion of another drug which alters the fraction of active drug, causing an aberrant response to a standardized dose. See the following examples:

Absorption Metal ions (Ca2+, Fe3+) form complexes with tetracyclines which decreases their absorption and bioavailability.

Distribution Warfarin is highly bound to albumin, so drugs such as sulfonamides which compete for binding sites on albumin cause displacement of warfarin, increasing its free fraction and anticoagulant effect. There are many drugs which influence the binding of warfarin like this.

Metabolism Rifampicin is a potent enzyme inducer ( p. 176) and increases metabolism of the OCP, reducing its clinical effectiveness; other forms of contraception should be used in such circumstances.

p. 176) and increases metabolism of the OCP, reducing its clinical effectiveness; other forms of contraception should be used in such circumstances.

Excretion Quinidine reduces the renal clearance of digoxin, resulting in higher than anticipated levels of serum digoxin and increasing the risk of digoxin side effects and/or toxicity.

Pharmacodynamic interactions Describe the effect that drugs have on the body and their mechanism of action. Interactions occur when 2 or more agents have affinity for the same site of drug action, eg:

• Salbutamol and propranolol (a non-specific β-blocker) have opposing effects at the β-adrenergic receptor; clinical effect is determined by the relative concentrations of the two agents and their receptor affinity.

► Drugs which commonly have interactions are worth keeping an eye out for. These include digoxin, warfarin, antiepileptics, antibiotics, antidepressants, antipsychotics, theophylline, and amiodarone.

This has been running since 1964 and is coordinated by the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA). During drug development, side effects with a frequency of 1:1000 or greater (more common) are likely to be identified, so the Yellow Card Scheme is important in detecting rarer side effects once a drug is in general use. All doctors have a duty to contribute to this. Yellow tear-out slips in the back of the BNF can be sent off or go online to  https://yellowcard.mhra.gov.uk/. The forms can be completed by any healthcare worker and even by patients.

https://yellowcard.mhra.gov.uk/. The forms can be completed by any healthcare worker and even by patients.

New drugs These are marked with an inverted triangle (▼) in the BNF. Any suspected reaction caused by a new drug must be reported.

► Sinister drug effects Such as anaphylaxis, haemorrhage, severe skin reactions etc., must be reported via the Yellow Card Scheme, irrespective of how well documented they already are.

Common drug reactions Such as constipation from opioids, indigestion from NSAIDs, and dry mouth with anticholinergics, are well recognized and considered minor effects which do not need reporting.

Every prescription should be carefully considered with specific reflection of the patient in question. If in doubt, consult the BNF or speak to the pharmacist or a senior. There are some groups of patients for whom prescriptions must be even more carefully considered.

Patients with liver disease The liver has tremendous capacity and reserve so liver disease is often severe by the time the handling of most drugs is altered. The liver clears some drugs directly into bile (such as rifampicin) so these should be used cautiously if at all. The liver also manufactures plasma proteins and hypoproteinaemia can result in increased free fractions of some agents (phenytoin, warfarin, prednisolone) and result in exaggerated pharmacodynamic responses. Hepatic encephalopathy can be made worse by sedative drugs (night sedation, opioids, etc), and fluid overload by NSAIDs and corticosteroids is well documented in liver failure. Hepatotoxic drugs (such as methotrexate and isotretinoin) should only be used by experts as they may precipitate fulminant hepatic failure and death. Patients with established liver failure have an increased bleeding tendency so avoid IM injections and employ caution if using any anticoagulant drugs. Paracetamol can be used in liver disease, but consider a reduced dose; consult the BNF/pharmacist. Special considerations for patients with liver disease are listed under each drug monograph in the BNF.

Patients with renal disease Patients with impaired renal function should only be given nephrotoxic drugs with extreme caution as these may precipitate fulminant renal failure; these include NSAIDs, gentamicin, lithium, ACEi, and IV contrast. Any patient with renal disease (impairment or end-stage renal failure) will have altered drug handling (metabolism, clearance, volume of distribution, etc) and more careful thought must be given when prescribing for the patients with GFR <60mL/min, and senior input sought when GFR <30mL/min (BNF, pharmacist or senior); the amount, dosing frequency, and choice of drug needs careful thought. Remember that a creatinine in the ‘normal’ range does not mean normal renal function,  p. 387. Special considerations for patients with renal disease are listed under each drug monograph in the BNF.

p. 387. Special considerations for patients with renal disease are listed under each drug monograph in the BNF.

Pregnant patients Many drugs can cross the placenta and have effects upon the foetus. In the first trimester (weeks 1–12), this usually results in congenital malformations, and in the second (weeks 13–26) and third trimesters (weeks 27–42) usually results in growth retardation or has direct toxic effects upon foetal tissues. There are no totally ‘safe’ drugs to use in pregnancy, but there are drugs known to be particularly troublesome. The minimum dose and the shortest duration possible should be used when prescribing in pregnancy and all drugs avoided if possible in the first trimester.

Drugs considered acceptable Penicillins, cephalosporins, heparin, ranitidine, paracetamol, codeine.

► Drugs to avoid Tetracyclines, streptomycin, quinolones, warfarin, thiazides, ACEi, lithium, NSAIDs, alcohol, retinoids, barbiturates, opioids, cytotoxic drugs, and phenytoin.

Special considerations for pregnant patients are listed under each drug monograph in the BNF.

Breastfeeding patient As with pregnant patients, drugs given to the mother can get into breast milk and be passed on to the feeding baby. Some drugs become more concentrated in breast milk than maternal plasma (such as iodides) and can be toxic to the child. Other drugs can stunt the child’s suckling reflex (eg barbiturates), or act to stop breast milk production altogether (eg bromocriptine). Speak to a pharmacist before prescribing any drug to a mother who is feeding a child breast milk. Special considerations for patients who are breastfeeding are listed under each drug monograph in the BNF.

Children See the British National Formulary for Children. Neonates are more unpredictable in terms of pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics than older children; prescriptions for this age group should be undertaken by experienced neonatal staff and drugs double-checked prior to administration. After the first month or two, the gut, renal system, and metabolic pathways become more predictable. Almost all drug doses still need to be calculated by weight (eg mg/kg) or by body surface area (BSA). There are a few drugs which should never be prescribed in children by a non-specialist, including tetracycline (causes irreversible staining of bones and teeth) and aspirin (predisposes to Reye’s syndrome); others should be used with caution such as prochlorperazine and isotretinoin. ► Always consult the BNF for Children when prescribing for paediatric patients.

Controlled drugs (CDs) CDs are those drugs which are addictive and most often abused or stolen, and are subject to the prescription and storage requirements of the Misuse of Drugs Regulations 2001; they include the strong opioids (morphine, diamorphine, pethidine, fentanyl, alfentanil, remifentanil, methadone), amphetamine-like agents (methylphenidate (Ritalin®)), and cocaine (a local anaesthetic). These agents are stored in a locked cabinet and a record of their use on a named patient basis is required to be kept by law. Some other drugs may be kept in the CD cupboard such as concentrated KCl, ketamine, benzodiazepines, and anabolic steroids, but this is not a legal requirement and will depend upon local policy. The weaker opioids (codeine) are not treated as controlled drugs though they are still often misused.

Prescribing controlled drugs Prescribing for in-patients is just like prescribing any other drug and the benefits should be balanced against potential side effects for each individual patient. Morphine, diamorphine, and tramadol are the most commonly prescribed CDs on the ward. As with all prescriptions, write the details clearly and make sure a maximum dose and a minimal interval between doses is documented ( pp. 88–91 for management of pain).

pp. 88–91 for management of pain).

Controlled drugs for TTOs  pp. 80–81.

pp. 80–81.

The term enzyme inducers is used to describe agents (usually drugs, but not always) which alter the activity of the cytochrome P450 enzymes (mostly found in the liver) which are involved in phase 1 metabolism (typically oxidation, reduction, and hydrolysis reactions). Agents which induce cytochrome P450 activity result in increased metabolism of the affected drugs and subsequently reduce the systemic drug response; inhibitors of cytochrome P450 have the reverse effect and result in exaggerated drug responses as more of the affected drug remains available to exert its effect. Common inducers and inhibitors are listed here. You’ll see warfarin is a frequent culprit (Table 4.1).

Table 4.1 Drugs interacting with warfarin—consult Appendix 1 of BNF

| Drugs which ↑INR | Alcohol, amiodarone, cimetidine, simvastatin, NSAIDs |

| Drugs which ↓INR | Carbamazepine, phenytoin, rifampicin, oestrogens |

Table 4.2 shows drugs that induce metabolic enzymes. Each of the drugs on the left can induce the enzymes so that all of the drugs on the right (and any of the other drugs on the left) will have reduced plasma levels:

Table 4.2 Enzyme inducers

| Enzyme inducers | Plasma levels reduced |

| Phenobarbital/barbiturates | Warfarin |

| Rifampicin | Oral contraceptives |

| Phenytoin | Corticosteroids |

| Ethanol (chronic use) | Ciclosporin |

| Carbamazepine | (All drugs on left) |

Table 4.3 shows some drugs which inhibit enzymes. Each of the drugs on the left can influence the metabolic enzymes responsible for breaking down the specific drug on the right; this has the effect of increasing the plasma level of this latter drug, exaggerating its biological effect.

Table 4.3 Enzyme inhibitors

| Enzyme inhibitors | Plasma levels increased |

| Disulfiram | Warfarin |

| Chloramphenicol | Phenytoin |

| Corticosteroids | Tricyclic antidepressants |

| Cimetidine | Amiodarone, phenytoin, pethidine |

| MAO inhibitors | Pethidine |

| Erythromycin | Theophylline |

| Ciprofloxacin | Theophylline |

Regard people with the following cardiac conditions as being at risk of developing infective endocarditis1:

• Acquired valvular heart disease with stenosis or regurgitation

• Structural congenital heart disease, including surgically corrected or palliated structural conditions, but excluding isolated atrial septal defect, fully repaired ventricular septal defect or fully repaired patent ductus arteriosus, and closure devices that are judged to be endothelialized

Offer people at risk of infective endocarditis clear and consistent information about prevention, including:

• The benefits and risks of antibiotic prophylaxis, and an explanation of why antibiotic prophylaxis is no longer routinely recommended

• The importance of maintaining good oral health

• Symptoms that may indicate infective endocarditis and when to seek expert advice

• The risks of undergoing invasive procedures, including non-medical procedures such as body piercing or tattooing.

Do not offer antibiotic prophylaxis against infective endocarditis:

• To people undergoing dental procedures

• To people undergoing non-dental procedures at the following sites:

Do not offer chlorhexidine mouthwash as prophylaxis against infective endocarditis to people at risk undergoing dental procedures.

• Investigate and treat promptly any episodes of infection in people at risk of infective endocarditis to reduce the risk of endocarditis developing

• Offer an antibiotic that covers organisms that cause infective endocarditis if a person at risk of infective endocarditis is receiving antimicrobial therapy because they are undergoing a gastrointestinal or genitourinary procedure at a site where there is a suspected infection.

Patients develop tolerance to and dependence on hypnotics (sedating drugs) if they are taken long term. They are only licensed for short-term use and should be avoided if possible.

Causes of insomnia Anxiety, stress, depression, mania, alcohol, pain, coughing, nocturia (diuretics, urge incontinence), restless leg syndrome, steroids, aminophylline, SSRIs, benzodiazepine/opioid withdrawal, sleep apnoea, poor sleep hygiene, levothyroxine.

Try to dose regular medications so that stimulants (steroids, SSRIs, aminophylline) are given early in the day, while sedatives (tricyclics, antihistamines) are given at night. Encourage sleep hygiene, ear plugs, eye shades, and treat any causes of insomnia.

Sleep hygiene Avoid caffeine in evening (tea, coffee, chocolate), alcohol, nicotine, daytime naps, phone use or cerebral activity before sleep; encourage exercise, light snack 1–2h before bed, comfortable and quiet location (ear plugs and eye shades), routine.

If the patient is still unable to sleep and there is a temporary cause (eg post-op pain, noisy ward) then it is appropriate to prescribe a one-off or short course (≤5d) of hypnotics (Table 4.4). Some patients may be on long-term hypnotics; these are usually continued in hospital. If long-term hypnotics are stopped, the dose should be weaned to minimize withdrawal.

Table 4.4 Common oral hypnotics

| Diazepam | 5–15mg/24h | Significant hangover effect, useful for anxious patients |

| Temazepam | 10–20mg/24h | Shorter action than diazepam, less hangover |

| Zopiclone | 3.75–7.5mg/24h | Less dependence and risk of withdrawal than diazepam and less hangover effect |

Contraindications Respiratory/hepatic failure and sleep apnoea.

Side effects These include hangover (morning drowsiness), confusion, ataxia, falls, aggression, and a withdrawal syndrome similar to alcohol withdrawal if long-term hypnotics are stopped suddenly.

Discharge If a patient is not on hypnotics when they enter hospital, they should not be on hypnotics when they leave. It is bad practice to discharge patients with supplies of addictive and unnecessary medications.

Violent/aggressive patients  p. 107 for emergency sedation.

p. 107 for emergency sedation.

Pre-op sedation should only be prescribed after discussion with the anaesthetist and is rarely offered these days. Diazepam and temazepam are options. Midazolam is a rapidly acting IV sedative; it should only be used by experienced doctors under monitored conditions (sats, RR, and BP) with a crash trolley available. Give 1–2mg boluses then wait 10min for the full response before repeating; >5mg is rarely needed.

Steroids given for >3wk should never be abruptly discontinued as this can precipitate an Addisonian crisis ( p. 338). Patients can need >60mg prednisolone per day for severe inflammatory disease and this must be converted to an appropriate IV corticosteroid dose if they are unable to take regular PO doses (Table 4.5, Box 4.3). Long-term steroid use should prompt consideration of osteoporosis prophylaxis (

p. 338). Patients can need >60mg prednisolone per day for severe inflammatory disease and this must be converted to an appropriate IV corticosteroid dose if they are unable to take regular PO doses (Table 4.5, Box 4.3). Long-term steroid use should prompt consideration of osteoporosis prophylaxis ( p. 451).

p. 451).

Table 4.5 Conversion of oral prednisolone to IV hydrocortisone

| Normal prednisolone dose | Suggested hydrocortisone dose* |

| ≥60mg/24h PO | 100mg/6h IV |

| 20–50mg/24h PO | 50mg/6h IV |

| ≤20mg/24h PO | 25mg/6h IV |

*If patients with known adrenal insufficiency, or those who have been on any dose of oral corticosteroids for >3wk present unwell, consider an initial dose of 100–200mg hydrocortisone IV STAT, then d/w senior as to regular steroid dose. If unable to tolerate PO administration, ensure equivalent IV steroids given, as per Box 4.3.

Box 4.3 Steroid conversion

These are equivalent corticosteroid doses compared to 5mg prednisolone, but do not take into account dosing frequencies or mineralocorticoid effects:

Withdrawing steroid therapy This is an art and must be performed gradually if steroids have been used for >3wks. Large doses (>20mg prednisolone or equivalent) can be reduced by 5–10mg/wk until dose is 10mg prednisolone/d. Thereafter the doses must be reduced more slowly, eg by 5mg/wk. If the patient has been on long-term steroids and there is significant concern about adrenal insufficiency then omit a single morning dose and arrange a short Synacthen® test. Resume dosing immediately after while awaiting results. If these show an adequate adrenal response, it is safe to stop steroid therapy; if not, discuss with endocrinology.

See Table 4.6 for side effects of steroids and treatment and monitoring options.

Table 4.6 Steroid side effects and treatment and monitoring options

| GI ulceration | Consider PPI or H2-receptor antagonist |

| Infections and reactivation of TB | Low threshold for culturing samples or CXR |

| Skin thinning/poor wound healing | Pressure care and wound care |

| Na+and fluid retention | Regular BP, fluid balance charts, and daily weighing of patients |

| Hyperglycaemia | Twice-daily blood glucose if taking high-dose steroids |

Osteoporosis ( p. 451) p. 451) |

Bone protection (Ca2+ + bisphosphonate) |

| Hypertension | Twice-daily BPs |

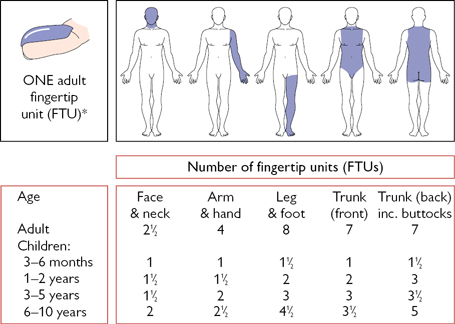

These are used in the treatment of many inflammatory skin diseases. As with corticosteroids given orally or intravenously, the mechanism of action is complex. Corticosteroids offer symptomatic relief but are seldom curative. The least potent preparation (see Table 5.20  p. 221) possible should be used to control symptoms. Withdrawal of topical steroids often causes a rebound worsening of symptoms and the patient should be warned about this. The amount of steroid needed to cover various body parts is shown in Fig. 4.4. Always wash hands after applying topical steroids.

p. 221) possible should be used to control symptoms. Withdrawal of topical steroids often causes a rebound worsening of symptoms and the patient should be warned about this. The amount of steroid needed to cover various body parts is shown in Fig. 4.4. Always wash hands after applying topical steroids.

Side effects Local thinning of the skin, worsening local infection, striae and telangiectasia, acne, depigmentation, hypertrichosis, systemic rarely adrenal suppression, Cushing’s syndrome (subsequent withdrawal of topical steroids can precipitate an Addisonian crisis).

Potency  p. 221 for a list of the common topical steroids used arranged by potency.2

p. 221 for a list of the common topical steroids used arranged by potency.2

Fig. 4.4 Amount of topical steroid required to treat various body parts. *One adult fingertip unit (FTU) is the amount of ointment or cream expressed from a tube with a standard 5mm diameter nozzle, applied from the distal crease on the tip of the index finger.

Reproduced with permission from Long, C.C. and Finlay, A.Y. (1991) Clinical and Experimental Dermatology, 16: 444–7. Blackwell Publishing.

These will be your key resource for antibiotic treatment. They are written to ensure the most appropriate antibiotics are used prior to knowing the pathogen and its antimicrobial sensitivities. Always seek advice from the microbiologists if deviating from the guidelines; their choice of suitable antibiotic will depend upon likely pathogen and its usual antimicrobial sensitivity, patient factors (age and coexisting disease), and drug availability. Some common infections and suggested antibiotic regimens are listed in Tables 4.7–4.9 (suitable for an otherwise healthy 70kg adult); more detailed options, including choices for patients with penicillin allergies, are listed  p649.

p649.

Taking cultures prior to commencing antibiotic therapy is important as they allow subsequent therapy to be more specifically tailored. However, cultures should not delay treatment in the septic patient.

Table 4.7 Common examples

| Lower UTI | Nitrofurantoin or trimethoprim |

| Pyelonephritis | Co-amoxiclav or ciprofloxacin |

| Cellulitis | Flucloxacillin 1g/6h PO/IV |

| Wound infection | As for cellulitis if after ‘clean’ surgery; for ‘dirty’ surgery or trauma, use co-amoxiclav 1.2g/8h IV |

| Meningitis | Ceftriaxone 2g/12h IV. Consider adding amoxicillin 2g/4h IV if patient >50yr, pregnant or immunocompromised and/or vancomycin 1g/12h IV if penicillin-resistant pneumococcal meningitis is suspected |

| Encephalitis | As for meningitis + aciclovir 10mg/kg/8h IV (to cover herpes simplex virus encephalitis) |

| Septic arthritis | Flucloxacillin. Base therapy on Gram stain of joint aspirate |

Table 4.8 Pneumonia

| Community-acquired (CAP), CURB65=0–1 | Amoxicillin 500mg–1g/8h PO |

| CAP, CURB65=2 | Amoxicillin 1g/8h PO/IV + clarithromycin 500mg/12h PO/IV |

| CAP, CURB65≥3 | Co-amoxiclav 1.2g/8h IV + clarithromycin 500mg/12h IV |

| Hospital-acquired aspiration pneumonia | There is considerable variation between hospitals so always consult local guidelines. Gram-negative cover is important |

Table 4.9 Septicaemia

| Urinary tract sepsis | Co-amoxiclav 1.2g/8h iv + gentamicin 5mg/kg IV STAT |

| Intra-abdominal sepsis | Tazocin® 4.5g/8h IV |

| Neutropenic sepsis | Tazocin® 4.5g/8h IV + gentamicin 5mg/kg/24h IV |

| Skin/bone source | Flucloxacillin 2g/6h iv |

| Severe sepsis/septic shock, no clear focus | Tazocin® 4.5g/8h IV + gentamicin 5mg/kg STAT |

A Gram-positive spore-forming anaerobic bacillus, which can asymptomatically colonize the gut. Exposure to antibiotics alters the balance of gut flora, promoting C. diff overgrowth, production of toxins that damage colonic mucosa, and subsequent symptomatic C. diff infection (CDI).

Transmission Via the faeco–oral route, after direct or indirect contact between patients, or ingestion of spores lying dormant in the environment. C. diff is now regarded as a major cause of hospital-acquired infections (HAI),  pp. 502–503.

pp. 502–503.

Clinical features of CDI Watery diarrhoea and abdominal pain are common; fever and leucocytosis are also seen; severe disease causes pseudomembranous colitis and toxic megacolon. Consider CDI in the differential of unexplained fever and raised inflammatory markers in hospitalized older adults. Elderly and frail patients are at especially high risk of dehydration, recurrent disease, and mortality from CDI.

Detection Through stool samples as soon as suspicion of CDI arises.3 Currently this involves a 2-stage process, with a rapid, screening test for a C. diff protein (or PCR for the C. diff toxin gene), followed by a more specific immunoassay for the C. diff toxin. Speak to the laboratory if there is any doubt. Consider an urgent AXR to rule out toxic megacolon.

Treatment See Box 4.4. Starts with metronidazole 400mg/8h PO or vancomycin 125mg/6h PO. Pay attention to fluid and electrolyte balance. Other regimens including higher doses of PO or PR vancomycin, IV metronidazole, or PO fidaxomicin may be required in patients who fail to respond or who relapse after initial treatment—always consult local guidelines and the microbiologist. Faecal microbiota transplantation (FMT) is an effective treatment for refractory cases, offered in a few UK centres.4

Infection prevention and surveillance Barrier nursing, good hand hygiene, and cleaning of equipment is key to preventing transmission to other patients (the spores are resistant to alcohol hand gels so hand washing with soap is essential). Local infection prevention teams should be made aware of suspected and confirmed cases, for advice on how to prevent transmission.

Box 4.4 Ecology, Clostridium difficile, and antibiotics

Box 4.4 Ecology, Clostridium difficile, and antibiotics

Intestinal carriage of C. diff does not equate with disease—what matters is when it outgrows other colonic commensal bacteria. Hence just controlling transmission is not entirely sufficient. Instead, we need to avoid disturbing the healthy colonic flora through indiscriminate use of broad-spectrum antibiotics. As part of this approach, most hospitals limit the use of cephalosporins, quinolones, and clindamycin. The national toolkit on antibiotic stewardship5 aids clinicians in reducing CDI rates as well as antimicrobial resistance. Always prescribe using local antibiotic guidelines, and regularly review whether prescriptions are needed.

1 NICE clinical guidelines available at  guidance.nice.org.uk/CG64

guidance.nice.org.uk/CG64

2 See these NICE Clinical Knowledge Summaries for an excellent resource in prescribing topical corticosteroids for different ages and body areas:  https://cks.nice.org.uk/corticosteroids-topical-skin-nose-and-eyes#!scenariobasis:5/-468112

https://cks.nice.org.uk/corticosteroids-topical-skin-nose-and-eyes#!scenariobasis:5/-468112

3 Bristol Stool Chart types 5–7 not attributable to an underlying condition (or therapy) from: hospital patients aged >2 years and community patients aged if >65 years or wherever clinically indicated.  https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/updated-guidance-on-the-diagnosis-and-reporting-of-clostridium-difficile

https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/updated-guidance-on-the-diagnosis-and-reporting-of-clostridium-difficile

4 NICE clinical guidelines available at:  guidance.nice.org.uk/ipg485

guidance.nice.org.uk/ipg485

5 Start smart then focus:  https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/antimicrobial-stewardship-start-smart-then-focus

https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/antimicrobial-stewardship-start-smart-then-focus