Meade’s ceremony was reportedly attended by every living Meade descendant, including his son and former aide, then Col. George Meade. The statue was covered by two large flags and was unveiled by the general’s grandson. Former cavalry division commander Gen. David M. Gregg, who led Union forces at East Cavalry Field on July 3, gave the oration. General Nelson Miles, then current Commanding General of the United States Army, was also in attendance and declared, “Too much cannot be said for the patriotism and military ability of” General Meade for taking command of a “poor, defeated army” and leading it to victory. 5

The bronze statue was sculpted by Henry Kirke Bush-Brown at a cost of $37,500. Meade sits approximately eight-tenths of a mile from General Lee’s statue atop the Virginia State Memorial and is astride his beloved horse, “Old Baldy,” who had been wounded in the battle. Meade feared that the old brute “will not get over it,” but Baldy outlived his master until 1882. 6

We have now concluded our tour of the Army of the Potomac’s defense of Cemetery Ridge on July 3. From the far left on Wright Avenue to the extreme right of Ziegler’s Grove, we have covered nearly 2.5 miles. You have experienced firsthand the fact that General Meade’s army had to manage a much broader front during this attack than simply the area surrounding the Angle.

Many of the Confederate commanders feared that Meade might launch a devastating counterattack following the repulse of Longstreet’s Assault. Colonel Edward Porter Alexander, with the years of hindsight that are often characteristic of his analysis, wrote in 1877, “I have always believed that the enemy here lost the greatest opportunity they ever had of routing General Lee’s army by prompt offensive.” 1 Alexander elaborated in his Military Memoirs:

It must be ever held a colossal mistake that Meade did not organize a counter-stroke as soon as he discovered that the Confederate attack had been repulsed. He lost here an opportunity as great as McClellan lost at Sharpsburg. Our ammunition was so low, and our diminished forces were, at the moment, so widely dispersed along our unwisely extended line, that an advance by a single fresh corps, the 6th, for instance, could have cut us in two. Meade might at least have felt that he had nothing to lose and everything to gain by making the effort. 2

General Lee’s report (dated January 1864) tersely stated only that his “troops were rallied and reformed, but the enemy did not pursue.” 3 Longstreet added:

General Wright, of Anderson’s division, with all of the officers, was ordered to rally and collect the scattered troops behind Anderson’s division, and many of my staff officers were sent to assist in the same service. Expecting an attack from the enemy, I rode to the front of our batteries, to reconnoiter and superintend their operations.

The enemy threw forward forces at different times and from different points, but they were only feelers, and retired as soon as our batteries opened upon them. These little advances and checks were kept up till night, when the enemy retired to his stronghold, and my line was withdrawn to the Gettysburg road on the right, the left uniting with Lieut. General A. P. Hill’s right. After night, I received orders to make all the needful arrangements for our retreat. 4

While touring the field during the battle’s 25th anniversary, former Army of the Potomac Chief of Staff Dan Butterfield (who was no ally of General Meade) successfully goaded Longstreet into acknowledging that Meade’s inability to successfully counterattack was “a fatal error. After the failure of Pickett’s Charge – and there were some of us who expected it to fail- there were men who stood on Seminary Ridge who expected to see a general advance by the Union forces. We were for a time in great trepidation. Our lines were very thin; they were in no condition to withstand an attack if it were made with any vigor. I am convinced that had we been then vigorously attacked there would have been an end to the war.” 5

Not that every Army of Northern Virginia veteran agreed with Longstreet. North Carolinian William Bond, angry over the attention given to Pickett’s Virginians, wrote that Longstreet was “evidently judging the army by his troops, some of whom are said to have been so nervous and shaky after this battle that the crack of a teamster’s whip would startle them.” 6

Whether or not General Meade acted aggressively enough to “finish” Lee’s battered army is one of the many contentious points of debate among battle scholars. Some historians have credited Meade with intending a full counterattack following the Confederate repulse. However, most accounts support Meade actually ordering something closer to a reconnaissance in force. In a dispatch to General Halleck, dated July 3, 8:35 p.m., Meade wrote:

After the repelling of the assault, indications leading to the belief that the enemy might be withdrawing, an armed reconnaissance was pushed forward from the left, and the enemy found to be in force. At the present hour all is quiet. My cavalry have been engaged all day on both flanks of the enemy, harassing and vigorously attacking him with great success, notwithstanding they encountered superior numbers, both of cavalry and infantry. The army is in fine spirits. 7

George Meade’s official report, dated October 1863, made no mention of an intended counterattack by either his infantry or cavalry. 8 When Meade testified before the Joint Committee on the Conduct of the War the following spring, he knew that he was open to criticism for his army’s inability to prevent Lee’s army from returning to Virginia after Gettysburg. Meade told the committee:

As soon as the assault was repulsed, I went immediately to the extreme left of my line, with the determination of advancing the left and making an assault upon the enemy’s lines. So soon as I arrived at the left I gave the necessary orders for the pickets and skirmishers in front to be thrown forward to feel the enemy, and for all preparations to be made for the assault. The great length of the line, and the time required to carry these orders out to the front, and the movement subsequently made, before the report given to me of the condition of the forces in the front and left, caused it to be so late in the evening as to induce me to abandon the assault which I had contemplated. 9

General Hancock, who had urged the V and VI Corps to be “pressed up” while himself wounded on the field, later testified: 10

I think it was probably an unfortunate thing that I was wounded at the time I was, and equally unfortunate that General Gibbon was also wounded, because the absence of a prominent commander, who knew the circumstances thoroughly, at such a moment as that, was a great disadvantage. I think that our lines should have advanced immediately, and I believe we should have won a great victory. I was very confident that the advance would be made. General Meade told me before the fight that if the enemy attacked me he intended to put the 5th and 6th corps on the enemy’s flank; I therefore, when I was wounded, and lying down in my ambulance and about leaving the field, dictated a note to General Meade, and told him if he would put in the 5th and 6th corps I believed he would win a great victory. I asked him afterwards, when I returned to the army, what he had done in the premises. He said he had ordered the movement, but the troops were slow in collecting, and moved so slowly that nothing was done before night, except that some of the Pennsylvania reserves went out and met Hood’s Division. 11

Meade’s alternatives for converting to the offense were surprisingly limited on the afternoon of July 3. His best infantry options were Sykes’s V and Sedgwick’s VI Corps on the Federal left. However, both corps would need time to mobilize and since neither command was ordered to prepare to counterattack during Pickett’s assault itself, time was of an even greater essence this late in the day. An assault by the V Corps would have been expected to form around the rocky Round Tops and march through the Plum Run valley to a still-occupied Houck’s Ridge. Although the VI Corps was relatively combat-fresh and had nearly 24 hours to recover from its forced march of July 2, it was generally dispersed (several brigades having received orders to move toward the focal point of Longstreet’s attack) and was not in position to attack as a full corps.

Fifth Corps commander George Sykes reported no receipt of any attack orders. 12 But Brig. General Samuel Crawford, commanding the Third Division, reported: “At 5 o’clock on the 3d, I received orders from General Sykes…to advance that portion of my command which was holding the ground retaken on the left…to enter the woods, and, if possible, drive out the enemy. It was supposed that the enemy had evacuated the position.” Crawford’s First Brigade under Col. William McCandless advanced with skirmishers and support from Brig. General Joseph Bartlett’s VI Corps brigade. They took some artillery fire but chased the Confederates through the Wheatfield, “completely routing” the 15th Georgia, and captured numerous prisoners. 13

Both Crawford and McCandless’s reports were generally non-specific on what stopped this pursuit, but Crawford wrote that the enemy “very greatly outnumbered us” and that the Southerners “intrenched themselves” on a second ridge. 14 However, in his testimony before the Joint Committee on the Conduct of the War, Crawford added that Meade had specifically instructed him to “clear the woods in my front; that if I found too strong a force I was not to engage them.” Upon questioning from the committee as to whether there was anything to prevent “the unemployed men of the 5th and 6th corps being thrown right on the retreating enemy,” Crawford answered, “Nothing at all, that I know of.” 15

General Meade did have cavalry of Brig. General Judson Kilpatrick’s division working opposite the Confederate right flank and they should have been expected to support any infantry assault. In fact, some argue that this was the catalyst of the ill-fated charge led by Brig. General Elon Farnsworth’s brigade.

Major General Alfred Pleasonton, commander of Meade’s Cavalry Corps, has been generally remembered by history as a manipulative schemer and no friend of Meade. Pleasonton alleged in his Congressional testimony, “Immediately after that repulse, I rode out with General Meade on the field, and up to the top of the mountain, and I urged him to order a general advance of his whole army in pursuit of the enemy.” After elaborating on numerous reasons why the Yankees should “have easily defeated and routed the enemy,” the cavalier explained that Meade instead “ordered me to send my cavalry to the rear of the rebels, to find out whether they were really falling back.” In Annals of the War, Pleasonton added that he even goaded his commanding officer, “General, I will give you half an hour to show yourself a great general,” but to no avail. 16

General Kilpatrick characterized his actions against the Confederate right as an “attack” based on orders that had been standing all day. He wrote, “At 8 a.m., received orders from headquarters Cavalry Corps to move to the left of our line and attack the enemy’s right and rear with my whole command and the Regular Brigade.” Although Brig. General George Custer’s Michigan brigade was detached without Kilpatrick’s approval, Farnsworth and Wesley Merritt’s two brigades were still available and “at 5.30 p.m. I [Kilpatrick] ordered an attack with both brigades.” 17 Kilpatrick added:

Previous to this attack, the enemy had made a most fierce and determined attack on the left of our main line of battle, with the view to turn it. We hope we assisted in preventing this. I am of the opinion that, had our infantry on my right advanced at once when relieved from the enemy’s attack in their front, the enemy could not have recovered from the confusion into which Generals Farnsworth and Merritt had thrown them, but would have been rushed back, one division on another, until, instead of a defeat, a total rout would have ensued. 18

Kilpatrick’s recollections are viewed with skepticism by some historians, given the controversies that ensued regarding General Farnsworth’s death, but he did correctly highlight the lack of coordination between the Federal infantry and cavalry on the Union left. While McCandless led a moderately successful but brief reconnaissance and Kilpatrick’s cavalry failed to break the Confederate right, a coordinated strike that included both cavalry and a larger portion of Sykes and Sedgwick’s infantry might have turned Longstreet’s right flank. But as events transpired, Law’s Brigade of Hood’s Division showed that they still had some fight remaining and no larger Union counterattack resulted. 19

Meade’s other choices were equally or even more problematic. Although Gen. Gouverneur K. Warren curiously characterized the battle as being “days of rest for most of” Meade’s enlisted men, nearly every corps was in a varying state of disorganization. 20 Given the hard feelings that were running against the XI Corps, it is difficult to envision a scenario where Union leadership would use Howard’s men to spearhead an attack. Slocum’s XII Corps would have required a transfer from Culp’s Hill and would have left Meade’s right flank vulnerable. Part of the challenge in converting from defense to offense in diminishing daylight was the fact that no arrangements were made to give a “return thrust” while Lee’s great assault was in progress. 21

Artillery chief Henry Hunt characterized the chances of Union success as a “delusion…rash in the extreme…stark madness” as “our troops on the left were locked up. As to the center, Pickett’s and Pettigrew’s assaulting divisions had formed no part of A.P. Hill’s line, which was virtually intact.” However, Hunt based his conclusion on the questionable assumption that Lee still had 140 artillery pieces armed and ready to repulse an assault—an asset that Lee was clearly lacking only an hour earlier when he was unable to adequately support his own attack. But with all of the factors that existed late on July 3, Hunt concluded, ”an immediate advance from any point, in force, was simply impracticable, and before due preparations could have been made for a change to the offensive, the favorable moment-had any resulted from the repulse- would have passed away.” 22

Finally, it is important to remember that Meade’s decision-making was also influenced by his erroneous belief that Lee’s army was “10,000 or 15,000” numerically superior to his own. 23 Meade was not the first army commander to suffer under this misapprehension, but he probably assumed that Lee had more available fresh troops in reserve than actually existed. Lee did have forces available (those who have been criticized for not being more actively involved in Pickett’s Charge for example) to slow an enemy counterattack, but whether or not they would have repulsed a “Pickett’s Charge in reverse” is simply unknowable. It did not occur because the Union generals exhibited more caution than aggression and the day ended. To quote General Warren:

[T]here was a tone amongst most of the prominent officers that we had quite saved the country for the time, and that we had done enough; that we might jeopardy all that we had won by trying to do too much. 24

Although viewed as a contemporary disappointment by some for seemingly failing to destroy Lee’s army, Meade had in fact won a great victory. “It was a grand battle,” Meade wrote his wife on July 5, “and is in my judgment a most decided victory, though I did not annihilate or bag the Confederate Army.” 25

The western slope of Cemetery Ridge was strewn with the refuse of Lee’s failed assault.

“Many of the retreating column lay down behind stones and hillocks,” recorded the historian of the 14th Connecticut, “and even the dead bodies of their comrades, to be protected from the Union shots. Presently, as by one common impulse, bits of white cloth and handkerchiefs were waved as signals of surrender.” Yankees then leapt over the wall to which “rebel wounded and unwounded in large numbers rose up and surrendered themselves.” 1

General Webb claimed that his brigade alone “captured nearly 1,000 prisoners.” 2 “Of the prisoners which fell into our hands,” reported General Hays, “I regret that no accurate account could be kept but by estimate, which cannot be less than 1,500.”3 Confusion reigned over who deserved credit for Confederate flag captures. “Several colors were stolen or taken with violence by officers of high rank from brave soldiers who had rushed forward and honestly captured them from the enemy,” complained Col. Norman Hall, “and were probably turned in as taken by commands which were not within 100 yards of the point of attack. Death is too light a punishment for such a dastardly offense.”4 Frank Haskell wrote:

Just as the fight was over, and the first outburst of victory had a little subsided, when all in front of the crest was noise and confusion,- prisoners being collected, small parties in pursuit of them far down into the fields, flags waving, officers giving quick, sharp commands to their men. 5

So many Southern prisoners were being herded over the crest that several victorious Union officers mistakenly thought that the enemy had carried Cemetery Ridge. General Hancock’s Chief of Staff, Lt. Colonel Morgan, actually began to order a nearby battery to limber up in retreat before he realized his mistake. Haskell observed that similar errors were made by others. 6

Getting accurate news and casualty reports was difficult in the immediate aftermath. It was widely circulated in Northern newspapers that General Longstreet was killed or wounded and in captivity, having been mistakenly confused in some instances with the mortally wounded Armistead. “Rebel prisoners report Longstreet a prisoner. General Gibbon announced to his troops that they had captured Longstreet and a member of Kilpatrick’s staff says he saw Longstreet a prisoner mortally wounded, lying in a barn…The citizens of Gettysburg affirm that Lee is certainly wounded.” 7

Dead and wounded were everywhere, a situation of horrific sights and offensive smells. Referring to the area inside the Angle, General Webb wrote to his wife, “I killed 42 Rebels inside of the fence.” 8 Colonel Hall observed, “Piles of dead and thousands of wounded upon both sides attested the desperation of assailants and defenders.” 9 Eventually 522 dead Confederates would be buried in a mass grave in the field between the Angle and the Emmitsburg Road. 10

An observer attached to General Hays noted: “The field was strewn with Rebel wounded.” Hospitals were overflowing on July 3. The following day, musicians were detailed with litters to bring in the wounded but “were fired upon so briskly by the Rebel sharpshooters that it was impossible to help them.” The man had previously heard and disbelieved such stories “but this came under my own observation. So all day Saturday the poor fellows lay there, praying for death.” General Hays himself wrote that on the following morning, “I could scarcely find passage for my horse” amongst the numerous dead and wounded. Displaying an unexpected softer side, General Hays said the “shrieks” were “heart rending.” 11

“After the fight I went over the battlefield,” wrote William Burns of the 71st Pennsylvania. “It was very thick with dead and wounded rebs. Bought in the wounded and lay at the fence all night. Rained during the night.” Burns recorded the following diary entry for July 4:

July 4- at stone wall all day. Rained in the morning. All quiet with us. Burying the dead. Shocking sights. This night each man slept with 3 loaded muskets at his side. A wet miserable day and night for us but a blessed day for our country. Rained all night. 12

Several farms along the Taneytown Road were converted into field hospitals to treat the wounded of Hancock’s II Corps, including the large Sarah Patterson farm. 13 The hospitals were subsequently moved farther behind the lines to farms that had open space and easier access to water. The II Corps hospital marker (completed in 1914) is located on what is now known as “Hospital Road” between the Taneytown Road and Baltimore Pike. (Not far from General Armistead’s death site at the George Spangler farm.) 14 The II Corps tablet states:

The Division Field Hospitals of the Second Corps were located at the Granite Schoolhouse but were soon removed to near Rock Creek West of the creek and six hundred yards southeast of the Bushman House. They remained there until closed August 7, 1863. These Hospitals cared for 2,200 Union and 952 Confederate wounded.

Total battle losses in Hays and Gibbon’s Army of the Potomac divisions have been estimated at a combined 2,938 from all causes. 15 In Webb’s brigade, Capt. William Davis (69th Pennsylvania) and Col. Richard Penn Smith (71st Pennsylvania) both estimated between 80-85% of their casualties as occurring on July 3, while Col. Norman Hall estimated 60% of his brigade’s dead and injured from the third day’s actions. It seems likely that at least 1,160 of Gibbon’s 1,647 losses happened on July 3. 16

Assuming that at least 60% of Hays’s 1,291 losses occurred on July 3, then Hays and Gibbon combined to suffer about 1,930 of their casualties defending Cemetery Ridge from Pickett, Pettigrew and Trimble. 17

“Our [Confederate] dead and wounded lay between the lines,” wrote Pickett’s staff officer Walter Harrison, “and the enemy’s sharpshooters fired upon our litter-bearers whenever an attempt was made to bring off the wounded. Many were brought in after dark, but we were still in ignorance of the actual fate and condition of the great majority of our officers and men until many days after.” On the morning of July 4, “we could not report an aggregate of 1,000 muskets; and this after returning to the ranks and arming all of the cooks and ambulance men…The exact number of killed, wounded, and missing, as subsequently ascertained, however, amounted to 3,393, just about three-fourths of the force carried into action.” Lieutenant Hilary Harris told his father on July 7, “Our division was annihilated” and only mustered about 1,000 men as they guarded Northern prisoners on the retreat. Harris wrote that his 11th Virginia “carried in about 300 men and lost upwards of 250.” 18

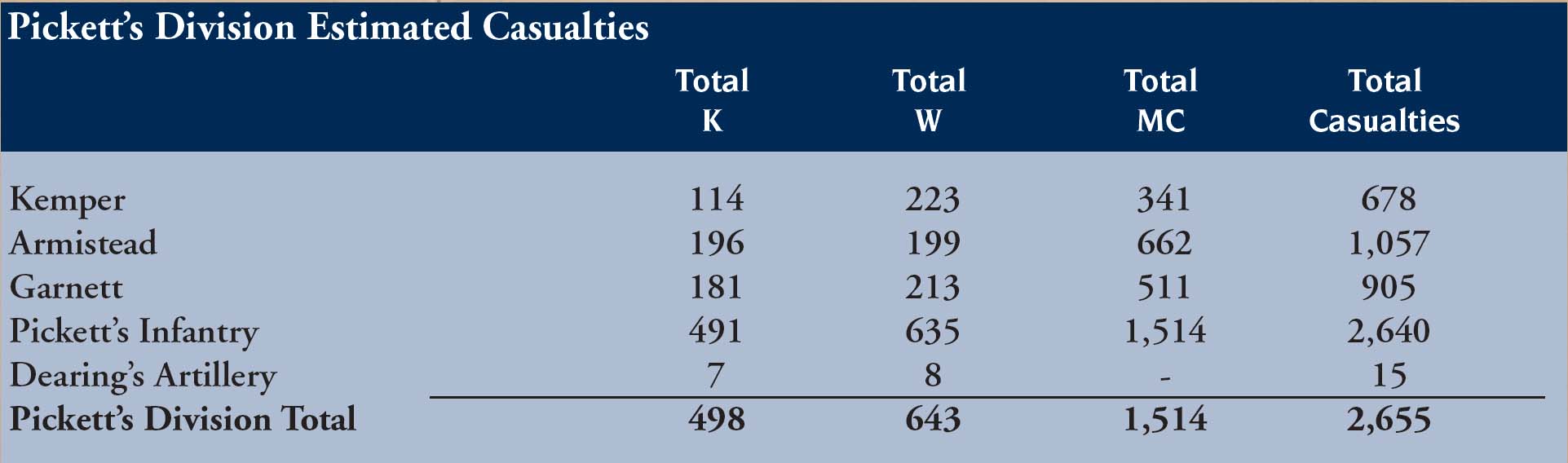

Initial returns for the Army of Northern Virginia estimated that Pickett’s Division alone suffered approximately 2,863 casualties with 224 killed, 1,140 wounded, and 1,499 captured/missing.19 In his most detailed study of Pickett’s casualties, researcher John Busey proposed 2,655 total losses, including 498 killed. 20

Busey’s revised upward strength estimates of 6,250 (including artillerymen) caused him to arrive at a 42.5% casualty rate. (45.4% for Pickett’s infantry only.) Of those categorized as wounded, 233 were mortal and subsequently died, resulting in 731 combat deaths. Finally, another 197 died in captivity, bringing the total estimated deaths in Pickett’s Division to 928. 21

There were also unreported casualties to contend with. Major Joseph Cabell, 38th Virginia, noted in his report that the “regiment lost in killed, wounded, and missing 230, besides about fifty slightly wounded, who are not reported, some of whom have returned to duty and others will do so in a few days.” 22 If each regiment failed to acknowledge an additional 20% of its casualties then Pickett’s total losses would easily have exceeded 50%.

Casualty rates are harder to ascertain in the other commands due to their earlier battle combat. Estimates of Heth’s Division (Pettigrew) casualties were approximately 53% for the entire battle. If we assume that Pettigrew took about 5,000 men into action on July 3 and suffered at least 40% casualties (comparable to Pickett), then Pettigrew lost 2,000 men or more to death, injuries, and capture. (The previously unengaged 11th Mississippi’s casualty rate has been estimated at 52.7%.) 23

Under General Trimble, Lane’s Brigade had seen minimal prior action and estimated 45.7% battle casualties. If we assume Lane and Lowrance combined to bring 2,300 men into action and suffered 45% casualties, then they lost 1,035 men. Wilcox and Lang’s 1,600 men would have created 720 more casualties at the same rate. In total, it seems probable that Confederate losses attributed to this assault were at least 6,400 men. Whatever the actual numbers on both sides, they were clearly lopsided against the attackers.

Many of Pickett’s wounded were treated at the division’s field hospitals at Francis Bream’s Mill and the John Currens farm. Sergeant D. E. Johnston of the 7th Virginia was treated at Bream’s Mill and remembered “the shed in which I was placed was filled with the wounded and dying…all night long I heard nothing but the cries of the wounded and the groans of the dying.” 24

The field hospitals for Heth (Pettigrew) and Pender’s (Trimble’s) Divisions were scattered along the Chambersburg Pike west of Gettysburg and near the fields where they had fought on July 1. The Samuel Lohr farm was a large hospital for Heth’s wounded while General Trimble and other of his casualties may have been treated at the nearby David Whisler farm. 25 Many of the injured from R. H. Anderson’s Division, including Wilcox’s Brigade and probably Lang’s, were sent to hospitals such as the Adam Butt farm along the Fairfield Road. 26

Generals Kemper and Trimble were among those deemed too injured to travel and did not return to Virginia with Lee’s army. After spending the majority of their treatment time in the Lutheran Seminary hospital, they were removed by train in August. The local Adams Sentinel reported on their departure: “We understand that General Kemper was very indignant at his removal from the comfortable quarters he had at the Seminary, where he had been so well attended to by female sympathizers, and growled at everything and everybody on his way to Baltimore.” 27

Amongst those in Pickett’s Division who eventually succumbed to their wounds, 126 died in Federal field hospitals, and 50 more in Southern hospitals (including 31 who passed away near Bream’s Mill.) Camp Letterman General Hospital, which was established east of town, became the final resting place of 31 men. Prisoner camps at Fort Delaware, Delaware (96), and Point Lookout, Maryland (95) claimed 191 more. Seventy of those at Fort Delaware are interred today in the National Cemetery at Finn’s Point, New Jersey. Finn’s Point was designated a National Cemetery in 1875 at the request of then-Virginia Governor James Kemper, who criticized the condition of the Confederate graves at Fort Delaware. The most ironic burial of all of Pickett’s men may be Pvt. Howson Hall of the 3rd Virginia. He survived captivity but died in November 1864 aboard a ship en route to Georgia for exchange. Private Hall was buried at sea. 28

In the early 1870s, the Confederate graves in and around the Gettysburg battlefield underwent a mass exhumation. The majority of the bodies were sent to Richmond. About 2,000 of Gettysburg’s Confederate dead, many assumed to be from Pickett’s Division, were buried amidst great ceremony as martyrs of the lost South at Richmond’s Hollywood Cemetery in an area that has become known as “Gettysburg Hill.” 29

Among those treated in the Union’s II Corps field hospitals was Capt. John Blinn, the assistant adjutant general to brigade commander Gen. William Harrow. The young Captain Blinn, born in 1841, was an Indiana native who had once served in a cadet group unit led by future Ben Hur author Lew Wallace. Blinn had been wounded at Antietam and was mortally wounded on July 3 at Gettysburg while leading reinforcements into action near the Copse of Trees. He was taken to the Jacob Schwartz farm for medical treatment. 1